Abstract

Purpose:

The purpose of this study was to identify training gaps and continuing education (CE) needs for speech-language pathologists (SLPs) in evaluating and treating children with cleft palate across and among areas of varying population density.

Method:

An anonymous 35-question survey lasting approximately 10–15 min was created in Qualtrics based on a previously published study. The survey information and link were electronically distributed to American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA)–certified SLPs through ASHA listservs, social media, individual-state SLP organizations, and an e-mail list of publicly listed SLPs. A total of 359 survey responses were collected.

Results:

Respondents varied in terms of age, type of certification, practice location, and clinical experience with cleft palate, with the largest percentage (46.7%) of respondents in a school-based setting. Only 28.5% reported currently feeling comfortable treating children with cleft palate. Respondents reported conventions/conferences (25.4%) and webinars (23.2%) were the most helpful resources, but DVDs were frequently not used for CE. Information from the child's cleft team (84.4%) and mentors/colleagues (70%) were considered high-quality resources. Respondents indicated information on treatment of articulation (79.2%) and resonance (78.4%) disorders as well as specific therapy techniques (76.9%) would be very helpful for clinical practice. Population density significantly influenced how respondents ranked the perceived helpfulness and quality of different resources as well as desired topics for future resources.

Conclusions:

There is a continued need for adequate training and CE opportunities for SLPs, particularly related to assessing and treating children with cleft palate. Increased access to high-quality CE resources will be key to filling educational gaps present for SLPs, especially in areas of low-population density.

Supplemental Material:

Cleft palate with or without cleft lip (CP ± L) is one of the most prevalent congenital birth defects in the United States (Parker et al., 2010). With varying types and severity, this craniofacial difference can be complex and impact multiple subsystems of speech production. Some children develop a communication disorder, whereas others do not. Cleft-related speech characteristics include both obligatory and learned behaviors, the latter of which can be targeted in speech therapy and includes (but is not limited to) glottal stop, pharyngeal fricative, or nasal fricative substitutions, as well as velar backing or middorsum articulation. It is not uncommon, however, for issues such as hearing loss, dental anomalies, and velopharyngeal dysfunction to complicate treatment planning for these children (Kotlarek & Krueger, 2023; Mason, 2020; Peterson-Falzone et al., 2017). While many errors can be treated in speech therapy, obligatory speech errors due to velopharyngeal dysfunction (e.g., hypernasality, nasal emission, and weak pressure consonants) or dental/occlusal status are not appropriate treatment targets for speech therapy. Furthermore, clefting can have a severely negative effect on an individual's function in society, psychosocial health, and overall quality of life (Berger & Dalton, 2009; Wehby et al., 2012). As a result, this population can experience an array of difficulties that may persist into adulthood if not successfully remediated in childhood.

Due to this disorder's complex nature, there are clear benefits of centralized care and resource management for individuals with CP ± L who often require coordination of several types of intervention, including surgery, orthodontic work, and speech therapy. Therefore, these children are often followed by professionals with expertise in craniofacial care and on a cleft palate/craniofacial team that have access to appropriate tools and resources to develop comprehensive treatment plans (Karnell et al., 2005). Collaboration is also key to providing appropriate treatment for this population, and community-based speech-language pathologists (SLPs) often work closely with other professionals on the craniofacial team to properly diagnose, manage, and treat the individual's CP ± L and corresponding issues (Kuehn & Henne, 2003). Due to the large service areas covered by craniofacial teams, complete and clear communication to the child's local, community-based SLP is essential to assure that proper and adequate treatment is taking place (Grames, 2004). A child may have two SLPs: one who is based locally (usually in the child's school) and provides therapy for many communication disorders on a regular basis and another who is part of a craniofacial team, specializes in assessing individuals with CP ± L, and monitors the child's progress on an annual or biannual basis.

There is a clear desire for and benefit from collaboration with an SLP on a craniofacial team. Bedwinek et al. (2010) concluded that 76% of preschool- and school-based SLPs identified communication with a cleft team SLP as beneficial and important for obtaining vital information. It has been proposed that the key to providing the best speech therapy is through experts educating community-based SLPs to ensure the highest quality treatment is being provided in settings such as schools (Grames, 2008). Educating community SLPs is reported to alleviate some of the demand placed on SLPs of cleft teams while increasing the quality of care provided to children with CP ± L by those community-based SLPs. Collaboration among these specialists ensures clients receive the highest quality care tailored to their specific needs.

Extensive training and knowledge are required for SLPs to deliver adequate and appropriate assessment and treatment for individuals with a wide range of disorders that fall within their scope of practice. In 1993, training in specific speech and language disorders was no longer required in graduate programs, and many courses on CP ± L were dropped from graduate curriculum (Vallino et al., 2008). Furthermore, the scope of practice for SLPs has dramatically broadened and caused graduate programs to consolidate multiple topics into one course (Grames, 2008). Mills and Hardin-Jones (2019) found the number of programs embedding CP ± L information in other courses has grown from 35% to 51%. Only about a quarter of current graduate programs in speech-language pathology have a course solely focused on CP ± L and craniofacial anomalies (Mason et al., 2020; Mills & Hardin-Jones, 2019). Vallino et al. (2008) noted that two thirds of responding speech-language pathology graduate programs offered a course specific to CP ± L, but only half of those programs required it for graduation. Focus on this patient population and content area has been decreasing in programs over the past decade, as only 27% of 201 accredited graduate programs in speech-language pathology included a required course focused on CP ± L in a 2020 survey (Mason et al., 2020). It was also noted that only a small portion of these dedicated courses are taught by experts in the care of individual with cleft palate and/or craniofacial differences. Mason et al. (2020) found that experts taught just 20% of the CP ± L courses. As a result, recent speech-language pathology graduates are often underprepared to work with the CP ± L population. Given these trends, continuing education (CE) resources may be sought out by clinicians engaging in the care of children with cleft/craniofacial conditions to “enhance and refine their professional competence and expertise” in this area (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association [ASHA] Code of Ethics, II-C, 2023).

Clinical experience is another vital aspect in preparation for assessing and treating individuals with CP ± L. Vallino et al. (2008) examined clinical experiences that accredited graduate programs offered their students. They found that 88% of students did not receive clinical practice experience with CP ± L (Vallino et al., 2008). This is concerning because, without clinical experience, students lack real-word opportunities for learning and working with this population. Another study looking at the educational background of school-based SLPs found that only 15% stated having had hands-on training working with clients with CP ± L, whereas 72% noted having provided therapy to a client with CP ± L at some point (Bedwinek et al., 2010). Vallino et al. further support this concern as 46% of their 133 responding graduate programs did not offer experience in the clinic related to CP ± L, reiterating that students are lacking supervised clinical practice during their graduate education. It is evident that SLPs receive little didactic and clinical training in working with CP ± L during graduate school, and therefore, a strong need for CE in this specialized area of practice has developed.

As hypothesized by Bedwinek et al. (2010), the lack of educational requirements has resulted in a negative outlook for delivery of proper speech services to individuals with CP ± L. A national survey was recently conducted by Mason and Kotlarek (2023) to identify the impact of rurality on SLP caseloads and practice patterns for children with CP ± L. Eighty-three percent of SLPs reported providing care for a child with CP ± L, and 41.4% have treated five or more children with CP ± L throughout their career (Mason & Kotlarek, 2023). While available resources differed significantly among areas of varying population density, SLPs in urban settings were no more likely to treat a child with CP ± L than their colleagues in a rural locale. However, SLPs in rural settings reported feeling uncomfortable making appropriate referrals and adequately assessing this population of patients (Mason & Kotlarek, 2023). It is clear that there is a need for accessible CE resources to support clinicians working with this population. However, it is unknown the type of CE resource that would be most beneficial to clinicians, particularly those who live in rural areas that may lack access to resources.

The purpose of this study was to identify current training gaps and CE needs for SLPs for evaluating and treating children with CP ± L across and among areas of varying population density. It was hypothesized that need-based differences may exist among areas of varying population density related to SLP preferences for CE resource types and training gaps.

Method

Sampling Procedure and Data Collection

The University of Virginia Institutional Review Board for Social and Behavioral Sciences approved the study, and an institutional affiliation agreement was in place with the University of Wyoming. Qualtrics was used to develop the 35-question anonymous survey. Questions were developed based on a comprehensive review of prior research conducted by Bedwinek et al. (2010) to not only replicate survey questions but also update to improve upon clarity, wording, and relevance to current practice (e.g., technological advances). Questions were reviewed by the statistics and consulting group at the University of Virginia to ensure formatting and response options of all survey questions matched the areas of inquiry and reduced potential for bias. Several features within the Qualtrics platform were used to promote validity, including randomization and rotation (to mitigate order effects and response biases), skip logic and branching (to minimize likelihood of irrelevant questions and improve quality of responses), response validation and required questions (to ensure accurate and consistent responses), and testing and previewing (to identify and rectify issues prior to dissemination). Informed consent was obtained within the Qualtrics platform prior to survey data collection. Survey design included yes/no, multiple-choice, Likert scale, and fill-in-the-blank questions. Information about respondents' use of CE resources, perceived quality of those resources, and desire for future CE resources pertaining to the assessment and treatment of patients with CP ± L was collected. Data also included demographic information such as practice location, population density, age range, salary range, and number of years working in the profession. Information was also collected on SLP's educational preparation in graduate school related to CP ± L, clinical experiences in graduate school with this population, and CE benefits provided by their employer. Survey questions related to this study can be found within Supplemental Material S1.

The survey was electronically distributed through ASHA listservs, social media, and individual-state SLP organizations, as well as through direct e-mail of publicly listed SLPs. The survey could be accessed on any electronic device using the provided URL or QR code. The investigators (K.J.K. and K.N.M.) shared the survey once on their personal, laboratory, and department Twitter and Instagram accounts. It is unknown how many times the survey was shared, given that it was posted across multiple social media platforms and provided to state organizations to disseminate throughout their membership. The survey took approximately 10–15 min to complete and was open for 4.5 months.

Respondent Characteristics

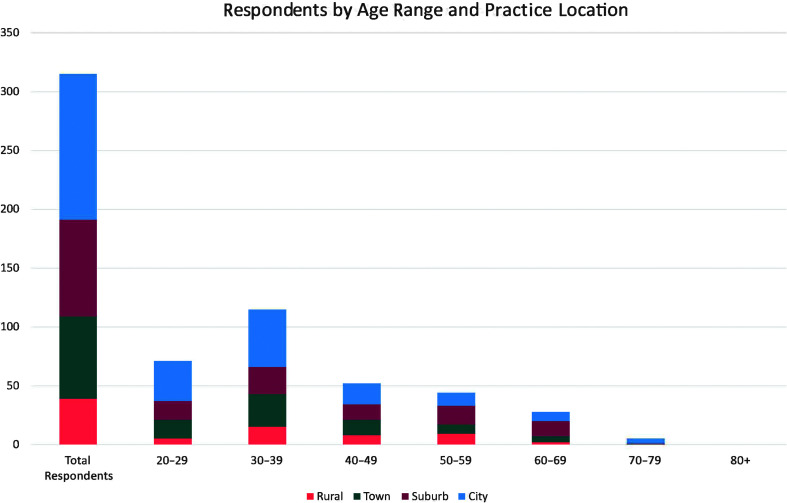

Of the 359 SLPs who responded to the survey, all were currently practicing, ASHA-certified SLPs either holding the ASHA Certificate of Clinical Competence (n = 279, 88.6%) or currently completing their clinical fellowship (n = 57, 15.88%). Most respondents were 30–39 years old (n = 115, 36.5%), followed by 20–29 years old (n = 71, 22.5%). Figure 1 shows the distribution of respondents across age groups stratified by practice location, demonstrating that city-based respondents were the most represented practice location across most age groups (except those aged 50–69 years, which received a greater number of respondents from suburban locations). Respondents also identified the number of years working in the profession. These categories ranged from less than 1 year to more than 30 years, with 27.2% (n = 85) of respondents reporting that they have been working in the profession for 1–5 years followed by 21.4% (n = 67), indicating 6–10 years in the profession. Primary practice setting was also reported by respondents. The school-based practice setting was indicated as the primary practice setting by 46.7% (n = 147) of respondents followed by 23.2% (n = 73) of respondents, indicating an early intervention setting. Median respondent salary fell within the range of $60,000–$75,000. All respondent characteristics are reported in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of respondents across age groups (in years) based on population density. Limited to only those who provided data regarding both age and practice location population density.

Table 1.

Respondent characteristics.

| Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Certification (n = 359 respondents) | ||

| ASHA-certified SLPs | 302 | 84.12 |

| Clinical fellows | 57 | 15.88 |

| Clinical practice setting(s) (n = 315 respondents) | ||

| Early intervention | 73 | 20.3 |

| School-based | 147 | 40.9 |

| Private practice/outpatient clinic | 67 | 18.7 |

| Inpatient hospital-based | 43 | 12.0 |

| Outpatient hospital-based | 64 | 17.8 |

| Long-term acute care | 6 | 1.7 |

| Home health | 18 | 5.0 |

| Skilled nursing facility | 13 | 3.6 |

| College/university | 27 | 7.5 |

| Corporate speech-language pathology | 7 | 1.9 |

| Retired | 9 | 2.5 |

| Other | 8 | 2.2 |

| Primary practice location (n = 315 respondents) | ||

| Rural (including frontier and remote) | 39 | 12.4 |

| Town | 70 | 22.2 |

| Suburb | 82 | 26.0 |

| City/metropolitan | 124 | 39.4 |

| Years in clinical practice (n = 313 respondents) | ||

| < 1 | 25 | 8.0 |

| 1–5 | 85 | 27.2 |

| 6–10 | 67 | 21.4 |

| 11–15 | 31 | 9.9 |

| 16–20 | 17 | 5.4 |

| 21–25 | 22 | 7.0 |

| 26–30 | 25 | 8.0 |

| 30+ | 41 | 13.1 |

| Have you ever provided care for a child with CLP? (n = 306 respondents) | ||

| Yes | 253 | 82.7 |

| No | 53 | 17.3 |

| Number of children with CLP seen over the course of your career (n = 243 respondents) | ||

| At least 1 | 26 | 10.7 |

| 2–4 | 87 | 35.8 |

| 5–9 | 45 | 18.5 |

| 10–14 | 17 | 7.0 |

| 15–19 | 9 | 3.7 |

| 20–49 | 17 | 7.0 |

| 50–99 | 9 | 3.7 |

| 100–499 | 15 | 6.2 |

| 500+ | 18 | 7.4 |

Note. Total number of survey respondents = 359. ASHA = American Speech-Language-Hearing Association; CLP = cleft lip and palate; SLP = speech-language pathologist.

Statistical Treatment

Survey data were compiled in aggregate and downloaded from Qualtrics. Twenty-eight of the 35 total questions were analyzed for this study; the other questions have previously been reported in Mason and Kotlarek (2023). All data were anonymous and summarized as a whole. Data were coded and analyzed using SPSS Software (Version 28.0; IBM Corp, 2021) and R Statistical Software (Version 4.1.2; R Core Team, 2022). Descriptive statistics were completed to identify differences in past training, confidence levels, and CE needs for respondents. Chi-square (χ2) tests of independence were completed to examine the relationship between practice location and perceived helpfulness of various CE resources, as well as to examine the relationship between practice location and what information SLPs desired to see in future CE resources. Consistent with procedures outlined by Mason and Kotlarek, the classification of practice location was based on the Institute of Education Sciences National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Locale and Classification Criteria, which utilizes four classification types (city, suburban, town, and rural) and the standard rural and urban definitions from the U.S. Census Bureau (Geverdt, 2015; NCES, 2021). Using these data, respondents were classified as rural, town, suburb, or city/metropolitan. For any expected cell frequencies that were observed to be less than five, the Fisher's exact statistic was utilized.

Results

Respondents included 359 currently practicing ASHA-certified SLPs or current clinical fellows of varying demographics (see Table 1) during the 4.5-month period that the survey was open between May and September 2021. While respondents were granted autonomy to choose the questions to which they responded (outside of certain required questions related to survey eligibility), results demonstrated a robust response rate of greater than 70% for all survey questions.

Comfort Level and Prior Training Related to Patients With CP ± L

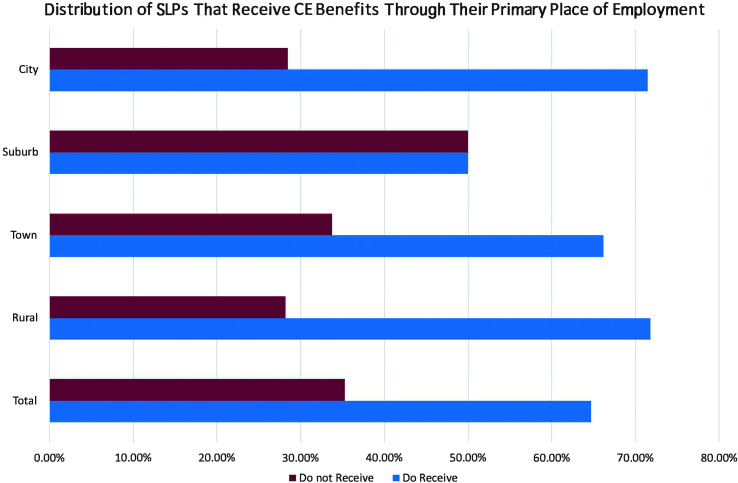

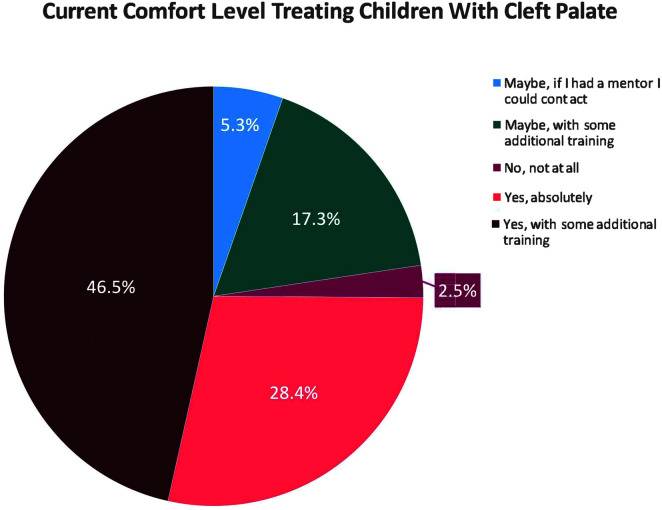

Figure 2 outlines the distribution of respondents receiving CE benefits through their employer across practice locations. Of 312 respondents, 64.7% (n = 202) indicated receiving CE benefits through their primary place of employment, whereas 35.3% (n = 110) indicated not receiving CE benefits. Clinicians in suburban practice settings (n = 41, 50%) received CE benefits less frequently than those working in rural (n = 28, 71.8%), town (n = 45, 66.2%), or city (n = 88, 71.5%) settings. Current comfort levels treating children with CP ± L were also identified by respondents. More than half of SLPs who responded to this question reported that they may feel comfortable treating this population with additional training and/or mentorship (n = 168, 69.1%). Sixty-nine respondents (28.4%) reported that they currently felt comfortable treating this population, whereas six (2.5%) did not feel comfortable at all working with this population (see Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Percentage of respondents who received continuing education benefits from their employer based on population density. SLP = speech-language pathologist; CE = continuing education.

Figure 3.

Percentage of respondents who are comfortable with treating children with cleft palate, who are not comfortable treating children with cleft palate, or with what support they would need to feel comfortable.

Of 315 respondents, 38.4% (n = 121) received education on assessing and treating CP ± L during graduate school from a designated course in this area, whereas 43.5% (n = 137) received this content as part of another course. However, the majority of respondents reported receiving this training after their graduate program, specifically 33.7% (n = 106) through CE opportunities and 30.5% (n = 96) through on-the-job training. Still, 4.8% (n = 15) indicated having no experience or training in assessing and treating children with CP ± L. Regarding clinical experience, the largest recorded percentage (n = 150, 49.3%) of the 304 total respondents for this question indicated they did not have any clinical experiences related to CP ± L during their graduate program. Of the 304 respondents, only 29 (9.5%) received a full clinical rotation on CP ± L or experience as part of a craniofacial team. Of those respondents who acquired clinical experience in their graduate program, 82 respondents (27%) were exposed to at least one client with CP ± L, whereas 14.1% (n = 43) indicated gaining experience with multiple clients with CP ± L.

Helpfulness and Prior Use of Existing CE Resources

When asked how helpful various CE opportunities were, SLPs who had previously utilized CE resources for this population found almost all existing resources only “somewhat helpful.” Responses to this question are shown in Table 2. In order of frequency, conventions/conferences (n = 67, 25.4%) and webinars (n = 61, 23.2%) were the most helpful resources noted by respondents, whereas textbooks (n = 26, 9.8%) and peer-reviewed journals (n = 21, 8.0%) were the most frequently ranked “not helpful at all.” Numerous additional and specific resources were also identified by respondents in the “Other” category, which encompassed the highest percentage of very helpful resources (n = 21, 17.9%). These fell into the following resource types/groupings, listed in order of frequency: (a) cleft team collaboration/observation, (b) expert mentorship/peer mentorship, (c) The Informed SLP subscription, (d) the LEADERSproject website and webinars (Crowley, n.d.), (e) referencing notes from graduate school, (f) past professors, (g) YouTube, (h) ASHA Practice Portal, (i) ASHA Learning Pass, (j) ASHA Special Interest Group 5: Craniofacial and Velopharyngeal Disorders (SIG 5) papers, (k) onsite competency training at practice location, or (l) learning with the client and family.

Table 2.

Perceived helpfulness and use of continuing education resources.

| Question: When working with children with repaired cleft lip/palate, how helpful have the following continuing education opportunities been? If you have not used a particular type of continuing education resource, please select “Have not used.” | Total |

Rural |

Town |

Suburb |

City |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 268 (100%) | 33 (12.3%) | 58 (21.6%) | 73 (27.2%) | 104 (38.8%) | ||

| Conventions/conferences | Have not used | 98 (37.1%) | 13 (40.6%) | 15 (26.3%) | 32 (43.8%) | 38 (37.3%) |

| Not helpful at all | 13 (4.9%) | 1 (3.1%) | 6 (10.5%) | 4 (5.5%) | 2 (2.0%) | |

| Somewhat helpful | 86 (32.6%) | 13 (40.6%) | 23 (40.4%) | 18 (24.7%) | 32 (31.4%) | |

| Very helpful | 67 (25.4%) | 5 (15.6%) | 13 (22.8%) | 19 (26.0%) | 30 (29.4%) | |

| Textbooks | Have not used | 58 (21.9%) | 10 (31.3%) | 6 (10.3%) | 20 (28.2%) | 22 (21.2%) |

| Not helpful at all | 26 (9.8%) | 2 (6.3%) | 10 (17.2%) | 9 (12.7%) | 5 (4.8%) | |

| Somewhat helpful | 128 (48.3%) | 15 (46.9%) | 32 (55.2%) | 30 (42.3%) | 51 (49.0%) | |

| Very helpful | 53 (20.0%) | 5 (15.6%) | 10 (17.2%) | 12 (16.9%) | 26 (25.0%) | |

| Peer-reviewed journalsa | Have not used | 76 (28.9%) | 15 (46.9%) | 17 (29.3%) | 20 (29.0%) | 24 (23.1%) |

| Not helpful at all | 21 (8.0%) | 2 (6.3%) | 6 (10.3%) | 7 (10.1%) | 6 (5.8%) | |

| Somewhat helpful | 114 (43.3%) | 14 (43.8%) | 25 (43.1%) | 32 (46.4%) | 43 (41.3%) | |

| Very helpful | 52 (19.8%) | 1 (3.1%) | 10 (17.2%) | 10 (14.5%) | 31 (29.8%) | |

| DVDsa | Have not used | 183 (70.7%) | 27 (84.4%) | 36 (63.2%) | 45 (66.2%) | 75 (73.5%) |

| Not helpful at all | 18 (6.9%) | 2 (6.3%) | 7 (12.3%) | 7 (10.3%) | 2 (2.0%) | |

| Somewhat helpful | 38 (14.7%) | 2 (6.3%) | 13 (22.8%) | 8 (11.8%) | 15 (14.7%) | |

| Very helpful | 20 (7.7%) | 1 (3.1%) | 1 (1.8%) | 8 (11.8%) | 10 (9.8%) | |

| Webinarsa | Have not used | 115 (43.7%) | 13 (40.6%) | 20 (34.5%) | 35 (50.0%) | 47 (45.6%) |

| Not helpful at all | 16 (6.1%) | 2 (6.3%) | 9 (15.5%) | 1 (1.4%) | 4 (3.9%) | |

| Somewhat helpful | 71 (27.0%) | 15 (46.9%) | 20 (34.5%) | 16 (22.9%) | 20 (19.4%) | |

| Very helpful | 61 (23.2%) | 2 (6.3%) | 9 (15.5%) | 18 (25.7%) | 32 (31.1%) | |

| Materials from the American Cleft Palate Craniofacial Associationa | Have not used | 127 (48.5%) | 23 (74.2%) | 19 (33.9%) | 40 (56.3%) | 45 (43.3%) |

| Not helpful at all | 11 (4.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (7.1%) | 4 (5.6%) | 3 (2.9%) | |

| Somewhat helpful | 67 (25.6%) | 7 (22.6%) | 24 (42.9%) | 12 (16.9%) | 24 (23.1%) | |

| Very helpful | 57 (21.8%) | 1 (3.2%) | 9 (16.1%) | 15 (21.1%) | 32 (30.8%) | |

| Other: ______________ | Have not used | 80 (68.4%) | 8 (57.1%) | 19 (70.4%) | 22 (78.6%) | 31 (64.6%) |

| Not helpful at all | 2 (1.7%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.1%) | |

| Somewhat helpful | 14 (12.0%) | 4 (28.6%) | 5 (18.5%) | 2 (7.1%) | 3 (6.3%) | |

| Very helpful | 21 (17.9%) | 1 (7.1%) | 3 (11.1%) | 4 (14.3%) | 13 (27.1%) | |

Note. “Other” responses included cleft team collaboration/observation, expert mentorship/peer mentorship, The Informed SLP subscription, teachers college website and webinars, referencing notes from grad school, past professors, YouTube, American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) Practice Portal, ASHA Learning Pass, ASHA Special Interest Group 5 papers, onsite competency training at practice location, or learning with client and family.

Significant result among areas of differing population density based on chi-square test of independence.

There was a statistically significant association among practice location and the perceived helpfulness of a variety of CE resources following a χ2 test of independence. A statistically significant association between population density and helpfulness was observed for peer-reviewed journals, χ2(3) = 17.55, p = .041; DVDs, χ2(3) = 18.75, p = .027; webinars, χ2(3) = 30.62, p < .001; and American Cleft-Palate and Craniofacial Association (ACPA) materials, χ2(3) = 30.01, p < .001. SLPs in the rural and town settings appeared to rate all resources more moderately (e.g., “somewhat helpful”) compared to suburb and city-based SLPs. While suburban- and city-based SLPs also rated numerous resources as “somewhat helpful,” they were more likely to rate webinars (25.7% [n = 18] and 31.1% [n = 32], suburban and city-based SLPs, respectively), ACPA materials (21.1% [n = 15] and 30.8% [n = 32], respectively), and other resources (14.3% and 27.1%, respectively) as “very helpful.” In contrast, only 6.3% (n = 2) of rural SLPs and 15.5% (n = 9) of town SLPs reported rating webinars as “very helpful,” and only 3.2% (n = 1) of rural SLPs rated ACPA materials as “very helpful.” No significant differences were observed for conventions, textbooks, and other fill-in-the-blank options. All ratings (overall and stratified by population density) can be examined in Table 2.

A proportion of SLP respondents across all density locations indicated that they had not utilized specific CE resources for this population, and a larger percentage of rural SLPs reported not having used a particular CE resource compared to other practice locations (see Table 2). The majority of respondents indicated that they had not utilized DVDs (n = 183, 70.7%), and a large proportion indicated that they had not used materials from the ACPA (n = 127, 48.5%), webinars (n = 115, 43.7%), conventions/conferences (n = 98, 37.1%), or other resources (n = 80, 68.4%; see Table 3). Despite this observation, a proportion of SLPs noted that these specific resources were helpful or very helpful. For example, the majority of respondents indicated they have not used DVDs as a CE resource (n = 183, 70.7%). However, nearly half ranked DVDs/webinars as a very helpful resource (n = 129, 49.2%). Similarly, 37.1% (n = 98) reported having not used conferences as a CE resource, but 56.4% (n = 146) ranked conferences as very helpful. While 48.5% (n = 127) reported not using materials from the ACPA, the largest percentage of respondents practicing in towns (n = 24, 42.9%) indicated this information to be somewhat helpful. Similarly, 43.7% (n = 115) of all respondents and 40.6% (n = 13) of rural respondents reported that they have not used webinars, but 27% (n = 71) of all respondents and 49.6% (n = 15) of rural respondents indicated they were a somewhat helpful resource.

Table 3.

Perceived quality of continuing education resources.

| Question: Please rate the quality of information received from each of the below resources for continuing education according to the below scales: 1 = poor-quality resource; 2 = somewhat quality resource; 3 = high-quality resource | Total |

Rural |

Town |

Suburb |

City |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 264 (100%) | 33 (12.5%) | 58 (22.0%) | 71 (26.9%) | 102 (38.6%) | ||

| Conventions/ conferences |

Poor-quality resource | 13 (5.0%) | 2 (6.3%) | 3 (5.3%) | 4 (5.6%) | 4 (4.0%) |

| Somewhat quality resource | 100 (38.6%) | 15 (46.9%) | 27 (47.4%) | 31 (43.7%) | 27 (27.3%) | |

| High-quality resource | 146 (56.4%) | 15 (46.9%) | 27 (47.4%) | 36 (50.7%) | 68 (68.7%) | |

| Textbooksa | Poor-quality resource | 53 (20.2%) | 9 (27.3%) | 15 (25.9%) | 16 (22.9%) | 13 (12.9%) |

| Somewhat quality resource | 142 (54.2%) | 20 (60.6%) | 32 (55.2%) | 39 (55.7%) | 51 (50.5%) | |

| High-quality resource | 67 (25.6%) | 4 (12.1%) | 11 (19.0%) | 15 (21.4%) | 37 (36.6%) | |

| Peer-reviewed journalsa | Poor-quality resource | 25 (9.5%) | 1 (3.0%) | 9 (15.5%) | 7 (9.9%) | 8 (7.8%) |

| Somewhat quality resource | 152 (57.6%) | 28 (84.8%) | 35 (60.3%) | 45 (63.4%) | 44 (43.1%) | |

| High-quality resource | 87 (33.0%) | 4 (12.1%) | 14 (24.1%) | 19 (26.8%) | 50 (49.0%) | |

| Other written materials | Poor-quality resource | 22 (8.5%) | 2 (6.1%) | 6 (10.7%) | 6 (8.6%) | 8 (7.9%) |

| Somewhat quality resource | 168 (64.6%) | 26 (78.8%) | 36 (64.3%) | 49 (70.0%) | 57 (56.4%) | |

| High-quality resource | 70 (26.9%) | 5 (15.2%) | 14 (25.0%) | 15 (21.4%) | 36 (35.6%) | |

| DVDs/webinars | Poor-quality resource | 22 (8.4%) | 1 (3.0%) | 8 (13.8%) | 6 (8.6%) | 7 (6.9%) |

| Somewhat quality resource | 111 (42.4%) | 18 (54.5%) | 28 (48.3%) | 26 (37.1%) | 39 (38.6%) | |

| High-quality resource | 129 (49.2%) | 14 (42.4%) | 22 (37.9%) | 38 (54.3%) | 55 (54.5%) | |

| YouTube videos | Poor-quality resource | 47 (17.9%) | 6 (18.2%) | 11 (19.0%) | 13 (18.3%) | 17 (16.8%) |

| Somewhat quality resource | 128 (48.7%) | 14 (42.4%) | 31 (53.4%) | 34 (47.9%) | 49 (48.5%) | |

| High-quality resource | 88 (33.5%) | 13 (39.4%) | 16 (27.6%) | 24 (33.8%) | 35 (34.7%) | |

| Social mediaa | Poor-quality resource | 78 (29.7%) | 9 (27.3%) | 21 (36.2%) | 23 (32.4%) | 25 (24.8%) |

| Somewhat quality resource | 137 (52.1%) | 23 (69.7%) | 34 (58.6%) | 31 (43.7%) | 49 (48.5%) | |

| High-quality resource | 48 (18.3%) | 1 (3.0%) | 3 (5.2%) | 17 (23.9%) | 27 (26.7%) | |

| Blogsa | Poor-quality resource | 83 (31.6%) | 7 (21.2%) | 21 (36.2%) | 20 (28.2%) | 35 (34.7%) |

| Somewhat quality resource | 143 (54.4%) | 24 (72.7%) | 33 (56.9%) | 41 (57.7%) | 45 (44.6%) | |

| High-quality resource | 37 (14.1%) | 2 (6.1%) | 4 (6.9%) | 10 (14.1%) | 21 (20.8%) | |

| Websites/Internet searcha | Poor-quality resource | 32 (12.2%) | 3 (9.1%) | 14 (24.1%) | 4 (5.6%) | 11 (10.9%) |

| Somewhat quality resource | 147 (55.9%) | 22 (66.7%) | 29 (50.0%) | 43 (60.6%) | 53 (52.5%) | |

| High-quality resource | 84 (31.9%) | 8 (24.2%) | 15 (25.9%) | 24 (33.8%) | 37 (36.6%) | |

| Information from child's cleft team | Poor-quality resource | 9 (3.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (6.9%) | 3 (4.2%) | 2 (2.0%) |

| Somewhat quality resource | 32 (12.2%) | 3 (9.1%) | 11 (19.0%) | 6 (8.5%) | 12 (11.9%) | |

| High-quality resource | 222 (84.4%) | 30 (90.9%) | 43 (74.1%) | 62 (87.3%) | 87 (86.1%) | |

| Information posted on hospital websites | Poor-quality resource | 44 (16.9%) | 6 (18.2%) | 11 (19.0%) | 13 (18.6%) | 14 (14.0%) |

| Somewhat quality resource | 143 (54.8%) | 20 (60.6%) | 32 (55.2%) | 39 (55.7%) | 52 (52.0%) | |

| High-quality resource | 74 (28.4%) | 7 (21.2%) | 15 (25.9%) | 18 (25.7%) | 34 (34.0%) | |

| Mentors/colleaguesa | Poor-quality resource | 14 (5.3%) | 1 (3.0%) | 8 (14.0%) | 5 (7.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Somewhat quality resource | 65 (24.7%) | 10 (30.3%) | 11 (19.3%) | 20 (28.2%) | 24 (23.5%) | |

| High-quality resource | 184 (70.0%) | 22 (66.7%) | 38 (66.7%) | 46 (64.8%) | 78 (76.5%) | |

Significant result among areas of differing population density based on chi-square test of independence.

Perceived Quality of CE Resources

Respondents ranked the quality of various resource types as a poor-quality resource, a somewhat quality resource, and a high-quality resource. Of the 264 responding SLPs, 84.4% (n = 222) indicated information from a child's cleft team to be a high-quality resource, and 70% (n = 184) reported mentors and colleagues to be a high-quality resource. Conventions were also considered to be high quality by 56.4% (n = 146) of respondents. On the contrary, social media (n = 78, 29.7%) and blogs (n = 83, 31.6%) were considered poor-quality resources by the largest percentage of respondents. Table 3 provides the full details and breakdown (overall and stratified by population density) for perceived quality of all resources.

Based on a χ2 test of independence, a statistically significant association was also observed among practice location and perceived quality of CE resources for textbooks, χ2(3) = 13.83, p = .032; peer-reviewed journals, χ2(3) = 26.96, p < .001; social media, χ2(3) = 20.42, p = .002; blogs, χ2(3) = 13.00, p = .043; websites/Internet searches, χ2(3) = 13.30, p = .038; and mentors/colleagues, χ2(3) = 16.80, p = .010. Textbooks were ranked somewhat quality by the majority of respondents (n = 142, 54.2%), which was a trend across areas of varying population density; however, a greater percentage of rural respondents (n = 9, 27.3%) ranked textbooks as poor quality, whereas a greater percentage of city respondents (n = 37, 36.6%) ranked them as high quality. A very similar trend was observed for websites and Internet searches. While the overall majority of respondents ranked the quality of information received from peer-reviewed journals as only somewhat quality (n = 152, 57.6%), nearly half of city respondents (n = 50, 49.0%) ranked this as high quality. The quality of information from social media and blogs was ranked as somewhat quality by 52.1% (n = 137) and 54.4% (n = 143) of total respondents, respectively, and this ranking trend remained steady across areas of varying population density with the greatest percentage of high-quality rankings observed by city dwellers (26.7% and 20.8%, respectively). Mentors and colleagues were ranked as a high-quality resource by the majority of respondents (n = 184, 70.0%) and across all areas of varying population density, with the highest percentage observed by city respondents (n = 78, 76%). No significant differences were observed for conventions, other written materials, DVDs/webinars, YouTube, information from the cleft team, or information from hospital websites.

Topics of Interest for Future CE Resources

Respondents were asked how helpful it would be to have CE on selected topics related to care for individuals with CP ± L, which is reported in Table 4. The majority of respondents indicated it would be very helpful to have more information regarding treatment of articulation disorders associated with velopharyngeal dysfunction (n = 209, 79.2%), treatment of resonance disorders (n = 210, 78.4%), and specific speech treatment techniques (n = 206, 76.9%). This trend was consistent for practitioners across all practice locations related to these topics. A large percentage of respondents also indicated information related to assessing the resonance (n = 186, 70.7%) and articulation (n = 198, 74.4%) of children with cleft palate would be very helpful. More than half of respondents indicated that information on language difficulties for children with CP ± L (n = 161, 60.8%), hearing acuity/loss in children with CP ± L (n = 162, 60.9%), and syndromes associated with CP ± L (n = 159, 60%) would be very helpful. The remaining topics surveyed were ranked as “somewhat helpful” by between 40% and 50% of respondents, and the topics with the largest percentage indicating “not helpful at all” included imaging techniques of videofluoroscopy (n = 46, 17.5%) and nasendoscopy (n = 41, 15.5%). A complete list of topics with numbers and corresponding percentages (overall and stratified by population density) can be seen in the first column of Table 4.

Table 4.

Helpfulness of specific continuing education topics for children with cleft palate with or without cleft lip.

| Question: How helpful would it be to have information about each of the following? Please rate the following according to the below scales: 1 = not helpful at all; 2 = somewhat helpful; 3 = very helpful | Total |

Rural |

Town |

Suburb |

City |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 269 (100%) |

33 (12.3%) |

59 (21.9%) |

73 (27.1%) |

104 (38.7%) |

||

| Assessment of resonance disorders | Not helpful at all | 4 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (1.4%) | 2 (2.0%) |

| Somewhat helpful | 73 (27.8%) | 13 (40.6%) | 20 (35.1%) | 21 (29.2%) | 19 (18.6%) | |

| Very helpful | 186 (70.7%) | 19 (59.4%) | 36 (63.2%) | 50 (69.4%) | 81 (79.4%) | |

| Assessment of articulation disorders related to velopharyngeal dysfunction | Not helpful at all | 13 (4.9%) | 1 (3.0%) | 4 (6.9%) | 6 (8.2%) | 2 (2.0%) |

| Somewhat helpful | 55 (20.7%) | 6 (18.2%) | 19 (32.8%) | 12 (16.4%) | 18 (17.6%) | |

| Very helpful | 198 (74.4%) | 26 (78.8%) | 35 (60.3%) | 55 (75.3%) | 82 (80.4%) | |

| Treatment of resonance disordersa | Not helpful at all | 12 (4.5%) | 1 (3.0%) | 8 (13.8%) | 2 (2.7%) | 1 (1.0%) |

| Somewhat helpful | 46 (17.2%) | 7 (21.2%) | 12 (20.7%) | 13 (17.8%) | 14 (13.5%) | |

| Very helpful | 210 (78.4%) | 25 (75.8%) | 38 (65.5%) | 58 (79.5%) | 89 (85.6%) | |

| Treatment of articulation disorders related to velopharyngeal dysfunctiona | Not helpful at all | 5 (1.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (5.4%) | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (1.0%) |

| Somewhat helpful | 50 (18.9%) | 5 (15.2%) | 18 (32.1%) | 14 (19.2%) | 13 (12.7%) | |

| Very helpful | 209 (79.2%) | 28 (84.8%) | 35 (62.5%) | 58 (79.5%) | 88 (86.3%) | |

| Specific speech treatment techniques | Not helpful at all | 10 (3.7%) | 1 (3.0%) | 4 (6.9%) | 2 (2.7%) | 3 (2.9%) |

| Somewhat helpful | 52 (19.4%) | 9 (27.3%) | 15 (25.9%) | 13 (17.8%) | 15 (14.4%) | |

| Very helpful | 206 (76.9%) | 23 (69.7%) | 39 (67.2%) | 58 (79.5%) | 86 (82.7%) | |

| How to do an oral exam for a child with cleft lip/palate | Not helpful at all | 14 (5.3%) | 1 (3.0%) | 5 (8.8%) | 3 (4.2%) | 5 (4.9%) |

| Somewhat helpful | 76 (28.7%) | 10 (30.3%) | 20 (35.1%) | 21 (29.2%) | 25 (24.3%) | |

| Very helpful | 175 (66.0%) | 22 (66.7%) | 32 (56.1%) | 48 (66.7%) | 73 (70.9%) | |

| Communicating with craniofacial team speech pathologists | Not helpful at all | 23 (8.7%) | 1 (3.1%) | 6 (10.5%) | 7 (9.7%) | 9 (8.7%) |

| Somewhat helpful | 87 (32.8%) | 15 (46.9%) | 19 (33.3%) | 19 (26.4%) | 34 (32.7%) | |

| Very helpful | 155 (58.5%) | 16 (50.0%) | 32 (56.1%) | 46 (63.9%) | 61 (58.7%) | |

| Cleft Team decisions (surgical planning, orthodontics, timelines for management, etc.) | Not helpful at all | 22 (8.3%) | 3 (9.1%) | 6 (10.7%) | 7 (9.6%) | 6 (5.8%) |

| Somewhat helpful | 94 (35.3%) | 16 (48.5%) | 23 (41.1%) | 25 (34.2%) | 30 (28.8%) | |

| Very helpful | 150 (56.4%) | 14 (42.4%) | 27 (48.2%) | 41 (56.2%) | 68 (65.4%) | |

| Aerodynamics or pressure flow for speech production | Not helpful at all | 25 (9.4%) | 1 (3.0%) | 6 (10.7%) | 9 (12.3%) | 9 (8.7%) |

| Somewhat helpful | 106 (39.8%) | 18 (54.5%) | 26 (46.4%) | 31 (42.5%) | 31 (29.8%) | |

| Very helpful | 135 (50.8%) | 14 (42.4%) | 24 (42.9%) | 33 (45.2%) | 64 (61.5%) | |

| Nasometry | Not helpful at all | 25 (9.4%) | 3 (9.1%) | 4 (7.0%) | 10 (13.9%) | 8 (7.8%) |

| Somewhat helpful | 103 (38.9%) | 14 (42.4%) | 28 (49.1%) | 27 (37.5%) | 34 (33.0%) | |

| Very helpful | 137 (51.7%) | 16 (48.5%) | 25 (43.9%) | 35 (48.6%) | 61 (59.2%) | |

| Video nasendoscopy or nasopharyngoscopy rationales | Not helpful at all | 37 (14.1%) | 7 (21.2%) | 8 (14.3%) | 9 (12.7%) | 13 (12.6%) |

| Somewhat helpful | 105 (39.9%) | 14 (42.4%) | 29 (51.8%) | 32 (45.1%) | 30 (29.1%) | |

| Very helpful | 121 (46.0%) | 12 (36.4%) | 19 (33.9%) | 30 (42.3%) | 60 (58.3%) | |

| Video nasendoscopy or nasopharyngoscopy techniques for velopharyngeal assessmenta | Not helpful at all | 41 (15.5%) | 5 (15.2%) | 9 (15.8%) | 12 (16.7%) | 15 (14.6%) |

| Somewhat helpful | 100 (37.7%) | 15 (45.5%) | 28 (49.1%) | 30 (41.7%) | 27 (26.2%) | |

| Very helpful | 124 (46.8%) | 13 (39.4%) | 20 (35.1%) | 30 (41.7%) | 61 (59.2%) | |

| Video fluoroscopya | Not helpful at all | 46 (17.5%) | 9 (28.1%) | 12 (21.1%) | 12 (16.7%) | 13 (12.7%) |

| Somewhat helpful | 110 (41.8%) | 12 (37.5%) | 29 (50.9%) | 35 (48.6%) | 34 (33.3%) | |

| Very helpful | 107 (40.7%) | 11 (34.4%) | 16 (28.1%) | 25 (34.7%) | 55 (53.9%) | |

| Language difficulties for children with repaired cleft lip/palate | Not helpful at all | 12 (4.5%) | 1 (3.0%) | 5 (8.9%) | 2 (2.8%) | 4 (3.8%) |

| Somewhat helpful | 92 (34.7%) | 9 (27.3%) | 18 (32.1%) | 28 (38.9%) | 37 (35.6%) | |

| Very helpful | 161 (60.8%) | 23 (69.7%) | 33 (58.9%) | 42 (58.3%) | 63 (60.6%) | |

| Hearing acuity/loss in children with cleft palatea | Not helpful at all | 15 (5.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (17.9%) | 3 (4.1%) | 2 (1.9%) |

| Somewhat helpful | 89 (33.5%) | 10 (30.3%) | 14 (25.0%) | 25 (34.2%) | 40 (38.5%) | |

| Very helpful | 162 (60.9%) | 23 (69.7%) | 32 (57.1%) | 45 (61.6%) | 62 (59.6%) | |

| Feeding | Not helpful at all | 23 (8.7%) | 4 (12.1%) | 6 (10.7%) | 7 (9.7%) | 6 (5.8%) |

| Somewhat helpful | 92 (34.7%) | 15 (45.5%) | 20 (35.7%) | 21 (29.2%) | 36 (34.6%) | |

| Very helpful | 150 (56.6%) | 14 (42.4%) | 30 (53.6%) | 44 (61.1%) | 62 (59.6%) | |

| Syndromes associated with cleft lip/palate | Not helpful at all | 6 (2.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.8%) | 3 (4.1%) | 2 (1.9%) |

| Somewhat helpful | 100 (37.7%) | 14 (42.4%) | 20 (35.7%) | 27 (37.0%) | 39 (37.9%) | |

| Very helpful | 159 (60.0%) | 19 (57.6%) | 35 (62.5%) | 43 (58.9%) | 62 (60.2%) | |

Significant result among areas of differing population density based on chi-square test of independence.

A χ2 test of independence revealed significant differences among population density for identified CE topics of interest. These included treatment of resonance disorders, χ2(3) = 18.29, p = .006; treatment of articulation disorders, Fisher's exact test, p = .021; videonasendoscopy or nasopharyngoscopy techniques for velopharyngeal assessment, χ2(3) = 12.97, p = .043; videofluoroscopy, χ2(3) = 15.20, p = .019; and hearing acuity/loss in children with cleft palate, χ2(3) = 22.21, p = .001. With the exception of hearing acuity/loss in children with cleft palate, which was rated as very helpful by a greater percentage of rural SLPs (n = 23, 69.7%), all of these topics were ranked “very helpful” by a greater percentage of city-based SLPs (n = 55–89, 53.9%–86.3%) than areas of lesser population density. No significant differences were identified for the remaining topics of interest. Some variability existed for rural and town-based SLPs compared to suburb and city-based SLPs in relation to helpfulness of cleft team decisions, aerodynamics and pressure flow, techniques and rationales for nasendoscopy, videofluoroscopy, and feeding. These SLPs were more likely to rate interest in CE information on those topics as “somewhat helpful.”

Discussion

This study intended to identify current training gaps and CE needs of SLPs related to assessment and treatment of children with CP ± L, while considering variations in population density among practice areas of the respondents. Our findings supported our hypothesis that need-based differences exist across areas of varying population density specifically related to SLP preferences for CE resource types and training gaps. Significant differences were observed among practice locations for perceived helpfulness of peer-reviewed journals, DVDs, webinars, and ACPA materials, while perceived quality of textbooks, peer-reviewed journals, social, blogs, websites/Internet searches, and mentors/colleagues demonstrated significant differences among practice location. Topics of interest also varied with practice location, as treatment of resonance and articulation disorders, video nasendoscopy/nasopharyngoscopy, videofluoroscopy, and hearing acuity/loss demonstrated location-based differences.

Courses dedicated to CP ± L are frequently reported to be lacking in SLPs' graduate programs, and there is a continued need for SLPs to gain this knowledge to provide competent assessment and treatment recommendations for this complex population of patients. Postgraduate CE serves as one means of acquiring this information, particularly for SLPs who have children with CP ± L on caseload. This has become more important as dedicated coursework related to assessment and intervention complexities for children with cleft palate has diminished over time. Several studies have noted more programs are embedding information on CP ± L in other courses rather than offering a dedicated course (Mason et al., 2020; Mills & Hardin-Jones, 2019; Vallino et al., 2008). The current study found 43.5% of respondents received education on CP ± L from an embedded course. This finding is supported by Mason et al. (2020), who found 46.2% of graduate programs offered courses with CP ± L content embedded (Mason et al., 2020). Only 38.4% of respondents from the current study reported that they received a dedicated course on cleft/craniofacial conditions, which is notably less than that reported by Mason et al. This difference could be due to the current study sample surveying individuals versus institutions. Additionally, individual SLPs without prior experience or education related to this population may have been more likely to respond or more interested in responding to the survey. Future studies should aim to compare the number of institutions that offer dedicated course with the number of students who opt to take that dedicated course, particularly if the course is listed as an elective course. Additionally, the current study also found that 49.3% of respondents reported graduating without any clinical experience with children with CP ± L, further highlighting the importance for accessible, relevant, postgraduate CE resources for SLPs working with this population. This appears to have increased in the past 5 years when compared to study findings by Mills and Hardin-Jones (2019) in which only 34% of respondents reported not receiving clinical experience with clients from the population with CP ± L.

The findings from this study identified that CE resources varied in terms of perceived helpfulness, quality, and interest areas. When asked about the helpfulness of CE resources that SLPs have used, the majority of respondents tended to identify each CE resource as “somewhat helpful” or “very helpful,” although variability did exist between groups based on rurality. Regarding the findings specifically related to conferences/conventions, respondents consistently identified conferences as high quality, regardless of practice location, and no significant differences were identified in the perceived helpfulness or quality of conferences across practice locations. This finding has remained consistent over the past approximately 10 years and was similarly reported by Bedwinek et al. (2010). Conferences may be consistently viewed as somewhat to very helpful because they provide a setting in which professionals from various locations come together to discuss new research, learn, and network. However, this modality for CE is often more resource heavy in terms of financial costs and time costs associated with obtaining CE information in this manner. Of note, nearly 40% of respondents reported not having used conferences/conventions as a CE modality. For those who did not engage in conferences/conventions, this may be due to the increased time and money required compared to other CE resources.

Some notable discrepancies were noted between perceived quality and helpfulness of resources. Interestingly, more SLPs in general were likely to rate textbooks lower for the quality of information received (nearly two thirds ranked this resource as poor to moderate quality) but were more likely to identify textbooks as a somewhat to very helpful resource. This may also highlight barriers to accessibility, where textbooks, despite lower quality rankings, are regarded as more helpful since this resource is likely to be highly accessible compared to other higher quality resources. In contrast, peer-reviewed journals were observed to be viewed as high quality but less helpful. Nearly 80% of respondents rated peer-reviewed journals as a moderate- to high-quality CE resource. However, nearly 30% of all respondents and nearly 50% of rural respondents reported not using this resource. These findings may highlight publisher accessibility barriers specifically related to the accessing and reading peer-reviewed journal articles. The “other helpful resources” category identified a number of resources deemed “very helpful” by SLPs. Of these, services such as web-based subscription resources (e.g., The Informed SLP subscription, ASHA Learning Pass) that focused on specific CE topics have been highlighted as ideal resources to facilitate understanding recent research and applying the research directly to clinical findings. These kinds of services help to reduce the research to practice barriers that are often reported and facilitate connecting clinicians with findings from peer-reviewed data. Cleft team collaboration/observation and expert/peer mentorship were also noted to be the top two “other resources” identified in this study, and these data are supported by findings from Grames (2008).

The percentage of respondents ranking DVDs as very helpful was similar between the current study (7.7%) and the study by Bedwinek et al. (2010; 6%). Given technology advancements and an increase in Internet access over the past decade, use of DVDs as a modality for CE was expected to decrease. However, in areas where Internet access may be limited, DVDs may continue to facilitate CE acquisition for SLPs living in those areas. Additionally, DVDs may prove helpful for visual learning and illustrating aspects of CP ± L that are more easily understood when viewed rather than read, similarly to webinars. Only one third of SLPs in the present study rated websites as very helpful compared to over half of the respondents in the prior survey (Bedwinek et al., 2010). Website content has dramatically expanded over the past 2 decades, and the difference in survey findings may be related to the sheer volume of web resources available today or increases in digital literacy.

ACPA materials were identified as somewhat to very helpful by approximately 40% of respondents; however, nearly half of the respondents reported not having used this resource, and notably, two thirds of rural respondents reported not having used this resource. New website updates, search engine optimization, and an increase in social media presence and outreach of the ACPA may result in greater awareness and use of these resources in the future. ASHA SIG 5 was also frequently identified as a “very helpful” resource in the open-ended survey response. These findings from respondents also indicated resources from the ASHA Learning Pass and other similar outlets as very helpful.

Impact of Practice Location on CE

The current study sought to examine how practice location may impact CE use and desire. It was hypothesized that SLPs practicing in rural locations would have access to fewer resources compared to urban populations due to the low prevalence of this disorder in combination with the low-population density among these areas. Previous research has noted that issues related to the impact of reduced resources in rural areas on clinical practice can be due to longer distances for providers to travel, fewer professionals providing services, and a very small number of professionals specialized to provide specific services (Valet et al., 2009). Information from conferences and cleft teams, although preferred, is less accessible to many SLPs in rural locations, and this is likely further exacerbated for individuals who do not receive CE benefits from their employer. These findings further emphasize the need to increase accessibility to high-quality CE resources for SLPs working with individuals with CP ± L, particularly in rural areas. This would facilitate increasing the number of professionals who have the necessary experience and training to work with this complex population.

The present study consistently found a greater percentage of rural and suburban SLPs having not used CE resources to gain more information on CP ± L. This difference could be due a number of factors, including but not limited to poor access related to physical accessibility of common CE resources in rural areas. While more rural SLPs reported receiving CE benefits through their employer compared to those working in more populated areas, travel to location-bound opportunities (such as in-person conferences/conventions) may be more difficult, costly, and time consuming. Salaries were reported to be lower in rural areas compared to more populated areas. Rural SLPs were more likely, in general, to report not using CE resources related to CP ± L compared to other areas. It may be the case that rural SLPs instead select CE that reflects the majority of their caseload and choose to not use available CE resources for the occasional child with CP ± L. Additionally, rural SLPs were more likely to identify “other resources” (such as “learning with the client/family” and “graduate school notes,” or “past professors” and “YouTube”) and rate these sources as “very helpful.” Of rural respondents, 74.2% indicated that they did not use ACPA resources compared to just 43.3% of those in the urban setting. This difference may be due to SLPs' varying knowledge of the ACPA and role of the ACPA-certified cleft/craniofacial teams. Most cleft teams are located in urban or suburban areas, so it is probable that clinicians in rural areas are less likely to engage with an ACPA-accredited team. This is consistent with findings reported by Mason and Kotlarek (2023). These percentages highlight that access and knowledge dissemination barriers continue to exist. Increased distances, less access to high-quality Internet, and overall fewer available opportunities may additionally hinder rural SLPs in obtaining high-quality CE resources, especially relating to content for children with CP ± L. This is an area of significant need and consideration when developing future CE resources.

Topics of Interest for Future CE Development Related to CP ± L

High-quality CE resources are essential to ensuring SLPs' training gaps are adequately filled and incorporating topics of interest into future CE development will be important for meeting the needs of SLPs for this population. Both the study by Bedwinek et al. (2010) and the current study identified resources that would be beneficial to have going forward. Trends remain consistent with a focus on treatment techniques for speech sound disorders associated with CP ± L and assessment resources for velopharyngeal dysfunction. Approximately 5%–9% of respondents identified certain topics of interest as “not helpful at all,” specifically topics related to imaging and instrumentation modalities and techniques (approximately 10%–15%). However, these findings demonstrate that all CE topics identified are likely to draw some interest and fill gaps for the majority of SLPs. CE content and coursework that builds on both the desired modalities for delivery and enhances knowledge in the necessary topic areas will be needed to support this area of practice.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has a few limitations. An overall response rate could not be calculated due to the electronic distribution methods utilized in this study. This survey was adapted from a previous survey (Bedwinek et al., 2010) with the permission of the authors for comparative purposes as well as to reduce bias; however, potential bias in survey development may still exist. The generalizability of these results may be limited by potential sampling bias, as those individuals who have worked with a child with CP ± L or desired CE may have been more likely to complete the survey. These limitations were reduced by the large overall response rate and distribution across the United States. Overall, the authors feel that the survey is representative of the greater population of SLPs practicing in the United States.

The decision not to employ weighting or imputation techniques is another limitation of this study. While the data collection approach resulted in response rates of greater than 70% for each question, the absence of these techniques may have implications for the broader applicability of study findings. Specifically, the lack of weighting could result in a less representative sample, potentially affecting the external validity of the results. Similarly, the absence of imputation may introduce limitations in the analysis of specific variables, as the patterns of missing data may influence the precision of estimates and statistical power. Findings should be interpreted within the context of these limitations. While the high response rates suggest that missing data and nonresponse bias may be minimal, the potential impact on certain analyses and subgroups should be acknowledged.

Due to academic requirement, we see programs continuing to embed cleft-related content into other courses, leaving SLPs potentially unprepared to assess and treat clients from this population. Therefore, high-quality CE opportunities will be key to filling in these educational gaps. In addition, it will be important for future resources to focus on assessment and treatment, as this is clearly desired by many currently practicing SLPs. Future studies should aim to extend this work by focusing on set types and number of resources to be made available, while considering population density and practice location. Furthermore, it would be beneficial for future studies to dive deeper into the situational factors potentially influencing these results using a more sensitive approach, such as qualitative interviews or focus groups. For example, future studies should examine why some population groups rely more on certain resources, what information is commonly taught in graduate coursework, and how community-based and cleft team SLPs are currently collaborating out in the field.

Implications for Practice

The educational pathway and clinical experiences obtained by SLPs to effectively assess and treat individuals with CP ± L may lead to many SLPs feeling a lack of confidence in their ability to provide services. The current study found that only 28.4% of SLPs felt comfortable treating a child with CP ± L. This raises concern for the quality of services that is being provided; the absence of prepared SLPs can have negative consequences beyond patient outcomes, given that children with cleft conditions are often seen on SLP caseloads (Mason & Kotlarek, 2023). In addition, 82.1% of SLPs surveyed over 10 years ago said they “did not feel prepared to treat a child with a cleft-related communication disorder” (Bedwinek et al., 2010). These findings suggest that SLPs have been entering and continue to enter the workforce without explicit training to work with patients with CP ± L, potentially affecting their confidence in diagnosing and treating associated communication and swallowing disorders.

This may lead to the development of an underserved patient population, a health care disparity, and fewer SLPs with proper training and education to adequately provide for this population. The current educational system for developing SLPs is likely lacking and causing inconsistencies in the quality of therapy being provided; it can “range from poor to excellent” (Pannbacker, 2004). There are various factors that play into whether a client receives poor or excellent quality therapy. Often, lack of education leads to weakly supported clinical decisions that result in poor or incorrect services being provided (Pannbacker, 2004). This poses a risk for negative treatment outcomes in patients with CP ± L. Additional training or mentorship may allow clinicians to feel more confident in treating and assessing patients with CP ± L. This is aligned with the finding from the current study, in which it was found that nearly two thirds of SLPs (69.1%) would feel comfortable if they had additional training and/or mentorship in this area of practice. The present study also highlights that there are tremendous outreach opportunities for SLPs with specialization in the area of cleft palate. With proper training and access to CE resources, SLPs may become confident in providing services to this underserved population and result in the provision of higher quality treatment.

Conclusions

This study highlights that there are existing gaps in the education and training of SLPs to assess and treat individuals with CP ± L and a desire to increase knowledge in this content area. There is a clear need for CE resources, especially those related to assessment and treatment for children with cleft/craniofacial conditions. The study highlights the impact of population density on the perception and use of existing CE resources. By improving the quality and increasing access to CE resources, SLPs may become more confident and able to provide high-quality services to this underserved population.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences under Grant P20GM103432 and the University of Wyoming Honors College, awarded to Katelan Rogers. This work was also supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Grant KL2TR003016, awarded to Kazlin N. Mason. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the University of Wyoming, or the University of Virginia.

Funding Statement

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences under Grant P20GM103432 and the University of Wyoming Honors College, awarded to Katelan Rogers. This work was also supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Grant KL2TR003016, awarded to Kazlin N. Mason. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the University of Wyoming, or the University of Virginia.

References

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2023). Code of ethics. https://www.asha.org/siteassets/publications/code-of-ethics-2023.pdf [PDF]

- Bedwinek, A. P., Kummer, A. W., Rice, G. B., & Grames, L. M. (2010). Current training and continuing education needs of preschool and school-based speech-language pathologists regarding children with cleft lip/palate. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 41(4), 405–415. 10.1044/0161-1461(2009/09-0021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Z. E., & Dalton, L. J. (2009). Coping with a cleft: Psychosocial adjustment of adolescents with a cleft lip and palate and their parents. The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal, 46(4), 435–443. 10.1597/08-093.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, C. (n.d.). English cleft palate speech therapy: Evaluation and treatment. LEADERSproject. Retrieved August 6, 2023, from https://www.leadersproject.org/ceu-courses-2/english-cleft-palate-speech-therapy-evaluation-and-treatment-asha-0-5-ceu-self-study-course/ [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. (2021). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 28.0).

- Geverdt, D. E. (2015). Education Demographic and Geographic Estimates Program (EDGE): Locale boundaries user's manual. NCES 2016-012. National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved January 29, 2023, from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED577162 [Google Scholar]

- Grames, L. M. (2004). Implementing treatment recommendations: Role of the craniofacial team speech-language pathologist in working with the client's speech-language pathologist. Perspectives on Speech Science and Orofacial Disorders, 14(2), 6–9. 10.1044/ssod14.2.6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grames, L. M. (2008). Advancing into the 21st century: Care for individuals with cleft palate or craniofacial differences. The ASHA Leader, 13(6), 10–13. 10.1044/leader.FTR1.13062008.10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karnell, M. P., Bailey, P., Johnson, L., Dragan, A., & Canady, J. W. (2005). Facilitating communication among speech pathologists treating children with cleft palate. The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal, 42(6), 585–588. 10.1597/04-130r1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotlarek, K. J., & Krueger, B. I. (2023). Treatment of speech sound errors in cleft palate: A tutorial for speech-language pathology assistants. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 54(1), 171–188. 10.1044/2022_LSHSS-22-00071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn, D. P., & Henne, L. J. (2003). Speech evaluation and treatment for patients with cleft palate. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 12(1), 103–109. 10.1044/1058-0360(2003/056) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason, K. N. (2020). The effect of dental and occlusal anomalies on articulation in individuals with cleft lip and/or cleft palate. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 5(6), 1492–1504. 10.1044/2020_PERSP-20-00056 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mason, K. N., & Kotlarek, K. J. (2023). Where is the care? Identifying the impact of rurality on SLP caseloads and treatment decisions for children with cleft palate. The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal. Advance online publication. 10.1177/10556656231189940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason, K. N., Sypniewski, H., & Perry, J. L. (2020). Academic education of the speech-language pathologist: A comparative analysis on graduate education in two low-incidence disorder areas. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 5(1), 164–172. 10.1044/2019_PERSP-19-00014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mills, B., & Hardin-Jones, M. (2019). Update on academic and clinical training in cleft palate/craniofacial anomalies for speech-language pathology students. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 4(5), 870–877. 10.1044/2019_PERS-SIG5-2019-0023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2021). Locale and classification criteria. Education Demographic and Geographic Estimates. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/edge/Geographic/LocaleBoundaries

- Pannbacker, M. D. (2004). Velopharyngeal incompetence: The need for speech standards. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13(3), 195–201. 10.1044/1058-0360(2004/020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, S. E., Mai, C. T., Canfield, M. A., Rickard, R., Wang, Y., Meyer, R. E., Anderson, P., Mason, C. A., Collins, J., Kirby, R. S., Correa, A., & National Birth Defects Prevention Network. (2010). Updated national birth prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the United States, 2004–2006. Birth Defects Research, Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 88(12), 1008–1016. 10.1002/bdra.20735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson-Falzone, S. J., Trost-Cardamone, J. E., Karnell, M. P., & Hardin-Jones, M. A. (2017). The clinician's guide to treating cleft palate speech (2nd ed.). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Valet, R. S., Perry, T. T., & Hartert, T. V. (2009). Rural health disparities in asthma care and outcomes. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 123(6), 1220–1225. 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.12.1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallino, L. D., Lass, N. J., Bunnell, H. T., & Pannbacker, M. (2008). Academic and clinical training in cleft palate for speech-language pathologists. The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal, 45(4), 371–380. 10.1597/07-119.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehby, G., Tyler, M., Lindgren, S., Romitti, P., Robbins, J., & Damiano, P. (2012). Oral clefts and behavioral health of young children. Oral Diseases, 18(1), 74–84. 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01847.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.