Abstract

Visual clinical diagnosis of dermatoses in people of color (PoC) is a considerable challenge in daily clinical practice and a potential cause of misdiagnosis in this patient cohort. The study aimed to determine the difference in visual diagnostic skills of dermatologists practicing in Germany in patients with light skin (Ls) and patients with skin of color (SoC) to identify a potential need for further education. From April to June 2023, German dermatologists were invited to complete an online survey with 24 patient photographs depicting 12 skin diseases on both Ls and SoC. The study’s primary outcomes were the number of correctly rated photographs and the participants’ self-assessed certainty about the suspected visual diagnosis in Ls compared to SoC. The final analysis included surveys from a total of 129 dermatologists (47.8% female, mean age: 39.5 years). Participants were significantly more likely to correctly identify skin diseases by visual diagnostics in patients with Ls than in patients with SoC (72.1% vs. 52.8%, p ≤ 0.001, OR 2.28). Additionally, they expressed higher confidence in their diagnoses for Ls than for SoC (73.9 vs. 61.7, p ≤ 0.001). Therefore, further specialized training seems necessary to improve clinical care of dermatologic patients with SoC.

Subject terms: Diagnosis, Physical examination, Skin diseases

Introduction

Visual clinical diagnosis plays a key role in clinical dermatology1,2. It is usually the first step in clinical routine and often paves the way for subsequent examinations such as bacteriological swab, the collection of scales, hair or nail material for mycological detection or the performance of skin biopsies for histopathological evaluation3–7. Therefore, initial visual misinterpretation of clinical findings can have major implications and delay the adequate treatment.

Visual diagnosis of skin diseases in people of color (PoC) is a major challenge in clinical practice8–13 and a potential cause of misdiagnosis in this patient cohort. For instance, Gupta et al. surveyed 125 residents in the United States (U.S.) regarding their self-assessed confidence in describing, diagnosing, and treating skin conditions in patients with light skin (Ls) and patients with skin of color (SoC)11. Across all items, respondents reported increased uncertainty when examining patients with SoC11. Further evidence is presented from another survey of dermatology residents in the U.S., according to which 91% of respondents supported additional training on skin conditions in patients with SoC12. In line with this observation, medical students in the U.S. misjudged skin diseases more frequently in PoC than in patients with Ls in a study of Fenton et al.8.

One reason for this difference might be the underrepresentation of skin diseases on SoC in classical dermatology textbooks. An analysis of commonly used textbooks in the U.S. in 2021 showed that only 4–19% of the illustrations were cases of PoC13. This lack of diversity in dermatology textbooks has also been described in Germany14. In the dermatology textbook “Braun-Falco’s Dermatology, Venereology, and Allergology,” which is a commonly known textbook in German-speaking countries, only approximately 4% of the illustrations showed PoC with skin conditions14,15. In the textbook “Dermatologie Venerologie: Grundlagen, Klinik, Atlas” published by Fritsch and Schwarz in 2018, as little as 0.54% of all images present patients with SoC14,16. A representative number of skin diseases on SoC can only be found in textbooks that focus on this topic17,18.

To the best of our knowledge, studies or surveys on the medical care of skin diseased PoC, as already conducted in the U.S. and described above, have rarely been published in Europe8,11,12. In particular, there is a lack of studies focusing on the visual diagnostic accuracy and certainty of dermatologists in Germany for patients with Ls and patients with SoC. In order to fill this gap, we conducted a nation-wide online survey among dermatologists practicing in Germany, who assessed the visual diagnostic skills of physicians in skin-diseased patients with Ls and patients with SoC to evaluate the need for training.

Results

A total of N = 129 completely (65.8%, 85/129) or partially (34.2%, 44/129) filled surveys were included in the analysis. Almost half of the participants were female (47.8%, 61/129), and the median age of the cohort was 39.5 years. Most respondents with complete known demographic information had a board certification in dermatology (63.5%, 54/85), practiced in a clinic (74.1%, 63/85), and identified as Caucasians (98.8%, 84/85). Respondents estimated to see a median of 5.2% of patients with SoC in their clinical practice. Participation in special courses for the treatment of patients with SoC was reported only in some rare cases (8.2%, 7/85).

Participants were significantly more likely to correctly identify skin diseases by visual diagnostics on patients with Ls than on patients with SoC (72.1% vs. 52.8%, p ≤ 0.001, OR 2.28).

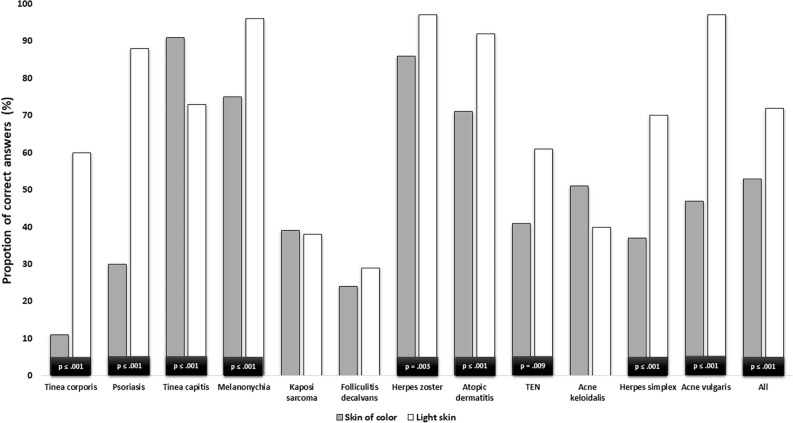

The comparison of the individual diseases showed that participants were significantly more likely to correctly identify the diseases tinea corporis, psoriasis, melanonychia, herpes zoster, atopic dermatitis, toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), herpes simplex, and acne vulgaris in patients with Ls than in patients with SoC.

In contrast, participants were significantly better at detecting tinea capitits in PoC than in patients with Ls. Acne keloidalis nuchae was also more frequently correctly diagnosed in patients with SoC than in patients with Ls, however, this difference was not statistically significant. Photographs of folliculitis decalvans and Kaposi’s sarcoma were correctly identified with a similar probability in both groups.

The results of the described comparison of visual diagnostic accuracy including the respective statistical information are shown in Fig. 1 and summarized in Table 1 (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of correct diagnoses between the skin types. Abbreviations: TEN = Toxic epidermal necrolysis, Acne keloidalis = Acne keloidalis nuchae. p-values are shown for statistically significant chi-square-tests at α = 0.05.

Table 1.

Comparative results of diagnostic accuracy.

| Investigated dermatoses | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Tinea corporis | Psoriasis | Tinea capitis | Melano-nychia | Kaposi sarcoma | Folliculitis decalvans | Herpes zoster | Atopic dermatitis | TEN | Acne keloidalis | Herpes simplex | Acne vulgaris | All | |||||||||||||

| Analysis | Relation of correct answers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Skin type | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC |

| Numbers of all analyzed answers | 90 | 96 | 89 | 89 | 90 | 97 | 90 | 98 | 93 | 89 | 94 | 101 | 94 | 95 | 91 | 91 | 86 | 86 | 91 | 94 | 86 | 87 | 95 | 93 | 1189 | 1116 |

| Relation of correct answers (%) | 60.0 | 11.5 | 88.8 | 30.3 | 73.3 | 91.8 | 96.7 | 75.5 | 38.7 | 39.3 | 29,7 | 24,5 | 97.9 | 86.3 | 92,3 | 71,4 | 61.6 | 41.9 | 40.7 | 51.1 | 70.9 | 37.9 | 96.8 | 46.7 | 72.1 | 52.8 |

|

p-value, chi-square-test |

< 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.932 | 0.412 | 0.003 | < 0.001 | 0.009 | 0.156 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||||||||||

| Odds ratio [95% CI] |

11.59 [5.44–2.49] |

18.14 [8.16–40.29] |

0.24 [.10-.58] |

9.40 [2.72–32.48] |

0.97 [.53–1.76] |

1.30 [.69–2.46] |

7.29 [1.59–33.28] |

4.80 [1.96–11.74] |

2.23 [1.21–4.10] |

0.65 [.36–1.17] |

3.99 [2.11–7.54] |

34.94 [10.31–118.44]c |

2.28 [1.92–2.71] |

|||||||||||||

SoC skin of color, Ls light skin, 95% CI 95% confidence interval.

Further subgroup analyses showed that board certified dermatologists were significantly more likely to find the correct diagnoses than residents in patients with Ls (76.4% vs. 64.0%, p = 0.018) as well as in patients with SoC (55.0% vs. 47.2%, p ≤ 0.001). In addition, respondents who had already attended a specialized course on treating patients with SoC were more likely to give the correct diagnosis in PoC. Table 2 summarizes the results of the subgroup analyses (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparative results of subgroup analyses.

| Investigated dermatoses | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Participants without board certification in dermatology | Participants with board-certification in dermatology | Participants who participated in specific courses for treatment of PoC | Participants who did not participate in specific courses for treatment of PoC | ||||

| Skin type | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC |

| Numbers of all analyzed answers | 372 | 362 | 627 | 627 | 23 | 35 | 259 | 438 |

| Relation of correct answers (%) | 64.0 | 47.2 | 76.4 | 55.0 | 70.9 | 55.7 | 71.8 | 51.9 |

|

p-value, chi-square-test, SoC |

0.018 | 0.514 | ||||||

|

p-value, chi-square-test, Ls |

< 0.001 | 0.855 | ||||||

SoC skin of color, Ls light skin.

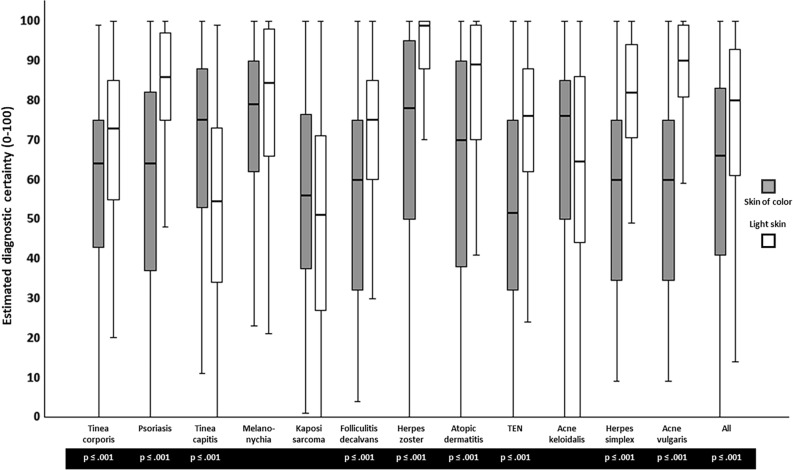

The analysis of participants’ self-assessed certainty about the suspected diagnoses showed higher mean scores, i.e., higher certainty, for the diseases on Ls than on SoC (73.9 vs. 61.7, p ≤ 0.001).

Consistently, respondents indicated higher diagnostic certainty in patients with Ls for the diseases tinea corporis, psoriasis, Kaposi sarcoma, melanonychia, folliculitis decalvans, herpes zoster, atopic dermatitis, TEN, herpes simplex and acne vulgaris than in those with SoC.

In contrast, evaluation of the photographs of tinea capitis and acne keloidalis nuchae led to higher mean certainty scale scores for the images of PoC than for the patients with Ls.

The results of participants’ self-assessed certainty about the suspected diagnoses including the respective statistical information are shown in Fig. 2 and summarized in Table 3 (Fig. 2, Table 3).

Figure 2.

Comparison of self-assessed diagnostic certainty between the skin types using box plot analysis. Rating was given on a visual analogue scale form 0 (completely unsure) to 100 (completely sure). Box plots display median values as centre line, the upper and lower quartiles as bounds of boxes, and the minimum and maximum values as whiskers. Abbreviations: TEN = Toxic epidermal necrolysis, Acne keloidalis = Acne keloidalis nuchae. p-values are shown for statistically significant t-test with α = 0.05.

Table 3.

Comparative results of diagnostic certainty.

| Investigated dermatoses | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Tinea corporis | Psoriasis | Tinea capitis | Melano-nychia | Kaposi sarcoma | Folliculitis decalvans | Herpes zoster | Atopic dermatitis | TEN | Acne keloidalis | Herpes simplex | Acne vulgaris | All diseases | |||||||||||||

| Skin type | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC | Ls | SoC |

|

Analyzed answers (n) |

90 | 90 | 89 | 89 | 91 | 91 | 90 | 90 | 89 | 89 | 91 | 91 | 88 | 88 | 87 | 87 | 90 | 90 | 89 | 89 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 1074 | 1074 |

| Mean value, diagnostic certainty (0–100) | 70.7 | 58.1 | 80.2 | 60.0 | 52.2 | 70.1 | 76.6 | 74.7 | 54.2 | 50.0 | 72.8 | 54.2 | 91.4 | 67.8 | 83.2 | 61.7 | 72.9 | 52.3 | 62.3 | 67.2 | 78.1 | 57.2 | 85.6 | 55.7 | 73.9 | 61.7 |

| Median value, diagnostic certainty (0–100) | 73 | 64 | 85 | 64 | 54 | 75 | 84 | 79 | 51 | 56 | 75 | 60 | 98 | 78 | 89 | 70 | 75 | 71 | 64 | 76 | 81 | 760 | 89 | 57 | 79 | 66 |

| p-value, t-test, mean value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.431 | 0.255 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.146 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||||||||||

SoC skin of color, Ls light skin.

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to identify possible differences in the skills and confidence of dermatologists practicing in Germany in the visual clinical diagnosis of patients with Ls and patients with SoC in order to identify a particular need for further training. We detected a significant difference in the quality of participants’ visual diagnostic skills between skin types: both the rate of correct suspected diagnoses as well as the subjective self-assessed certainty about the diagnoses were significantly lower for cases of patients with SoC.

In particular, the participants’ correct diagnoses of dermatoses with inflammatory reactions in patients with Ls significantly outweighed the correct diagnoses in patients with SoC. A likely explanation could be the fact that inflammatory dermatoses such as tinea corporis, psoriasis, herpes zoster, atopic dermatitis, TEN, herpes simplex, and acne vulgaris are usually associated with erythema on Ls19–28 which provides an important sign for dermatologists to the correct visual diagnosis. On SoC, erythema can be completely missing or appear in violaceous, ashen gray or darker brown color29–44. In line with this observation, respondents' self-assessed certainty for these diseases showed lower values for PoC, indicating that respondents were aware of their own uncertainty in treating PoC suffering from these diseases.

The largest difference in diagnostic accuracy between the skin types was observed for tinea corporis. Visual diagnosis of tinea corporis in PoC is a major challenge due to the above-described problem of a lack of characteristic erythema as well as a lack of or poorer demarcation of peripheral scales on SoC than on Ls, so that differential diagnoses such as atopic eczema, impetigo contagiosa, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or granuloma annulare can be poorly differentiated by visual diagnostics19,20,32. Nevertheless, the participants’ rate of only 11% of correct diagnoses of tinea corporis in PoC is worrisome. Of equal concern was the fact that 68.1% of the cohort did not recognize the life-threatening disease of TEN in PoC28,36,37. However, not all cases were better and more confidently diagnosed in patients with Ls than in patients with SoC. Tinea capitis and acne keloidalis nuchae were more likely to be detected on SoC than on Ls, and participants also reported a greater certainty on SoC than on Ls. A possible reason explaining these results could be data showing a higher prevalence for these diseases in PoC, possibly leading to increased expectations among participants for these dermatoses in PoC. It is important to note that these conditions can of course affect anyone, regardless of the individual skin type45–47. In contrast to these interpretations and findings, participants correctly detected melanonychia significantly more often in Ls than in PoC, although melanonychia is more common in PoC48–50. This outcome and also all other findings with higher rates of correct diagnoses and certainty for diseases on Ls could be associated with the fact that participating physicians reported to treat much more patients with Ls than with SoC (5.2%) in their daily routine and were therefore much better trained on Ls.

To generate further information about the assessed cohort, subgroup analyses were carried out. These showed that participants with acquired board certification in dermatology were more likely to correctly classify the photographs on Ls as well as on SoC than the participating residents. In view of the fact that skills of visual diagnostics can be improved by training and experience, this finding is not unexpected51.

Another subgroup analysis focused on specific courses for dermatological diagnostic and treatment of PoC. The results indicated that just a few participants had attended special classes so far, but those who had done so performed above average in determining the correct diagnoses in PoC. This finding shows that specific courses are useful to improve the skills of dermatologists and, in turn, the medical care of PoC.

The presented work has some limitations. In view of the response rate of around 3%, a selection bias of participants who are especially interested in the topic cannot be ruled out. However, as such a bias would only suggest an even worse performance of dermatologists in the real world, we still regard our findings as valid. Furthermore, finding a correct diagnosis without any other information about the shown cases is a challenging and somewhat artificial task, potentially leading to the partially low rates of correct answers and explaining the poor results regarding folliculitis decalvans and Kaposi sarcoma for both skin types. In addition, even though great care was taken in choosing the pictures with regard to comparability between skin types, they may have had different individual levels of difficulty for clinical assessment, which may have influenced the results.

The presented study is the first of its kind and offers a so far unique insight into the diagnostic accuracy and confidence of German dermatologists in PoC compared to patients with Ls. The results of our study, involving more than 100 participants, highlight the urgent need for further training of dermatologists working in Germany to improve their diagnostic visual skills in PoC.

Given Germany’s highly diverse society, which includes for example more than one million people of African descent52,53, the results of our study, which reflect the current situation in Germany, underscore the urgent need for further education on this important topic.

Materials and methods

The online survey was conducted between April and June 2023. The Ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of the University Duisburg-Essen gave its approval prior to the start of the study (reference number 23-11100-BO) and all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The patients in this manuscript have given written informed consent to publication of their case details. Physicians working in a dermatologic clinic or in private practice in Germany were invited to participate via personal contacts and via the newsletter of the German Dermatologic Society (Deutsche Dermatologische Gesellschaft, DDG, N = approximately 3800 members). All participants gave their written informed consent at the beginning of the questionnaire. Participation was voluntary and could be discontinued at any time without the need to give any reason.

The questionnaire consisted of 24 photographs of patients, which had been collected in the context of the clinical routine, showing 12 different skin diseases, once on Ls and once on SoC to allow for comparisons. However, participants were not informed about this design in advance. The order of cases was randomized between participants. Without being given any additional information about the depicted patient, participants were asked to give a suspected diagnosis based on the images. In addition, they were asked to indicate how certain they were about this diagnosis on a scale from 0 (completely uncertain) to 100 (completely certain). To record the participant characteristics, additional demographic questions were asked about age, gender, ethnicity, work experience, worksite and prior experience or training in the treatment of patients with Soc.

can be found in the Supplemental Material (Supp. Fig. 1). The diagnoses of the following cases had been validated by means of comprehensive diagnostics such as skin biopsies, pathogen-specific-PCR or mycological cultures prior to this study: tinea corporis, tinea capitis, Kaposi sarcoma, folliculitis decalvans, herpes simplex and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). The correct answers to the cases psoriasis, melanonychia, herpes zoster, atopic dermatitis, acne keloidalis nuchae, and acne vulgaris were determined by a team of 4 dermatologists by clinical examination.

To measure differences in the number of correctly rated photographs depending on the skin type, chi-square tests with a significance level of α = 0.05 were used and odds ratios (OR) were calculated. To detect statistically significant differences between the diagnostic certainty per skin type, t-tests with α = 0.05 were performed.

The questionnaire was created using the online tool LimeSurvey (LimeSurvey GmbH, Hamburg, Germany). Figures were created with Microsoft PowerPoint (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, U.S., version 2306) and IBM SPSS Statistics (Statistical Package for Social Science, SPSS Inc., Chicago, version 27). Statistical analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank all participating dermatologists and the German Dermatologic Society for supporting our work. No funding was granted for the study.

Author contributions

Study conception and design: F.K., M.M., S.H., J.D., W.S. Data collection: F.K., S.H., W.S. Data analysis and interpretation: F.K., S.H., J.M.P., R.T.E., L.J.A., A.T., D.S., S.U., J.D., W.S. Manuscript drafting: F.K., S.H., W.S., J.D., S.U. Review and approval of manuscript: all authors.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

Frederik Krefting received travel support for participation in congresses and / or (speaker) honoraria from Novartis, Lilly, Almirall, and Boehringer Ingelheim outside of the present publication. Stefanie Hölsken declares no conflict of interest. Jan-Malte Placke served as consultant and/or has received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Sanofi, and received travel support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, and Therakos. Maurice Moelleken received travel support for participation in congresses and/or (speaker) honoraria from Adtec-health Care and Urgo. Robin Tamara Eisenburger declares no conflict of interest. Lea Jessica Albrecht received honoraria from Novartis, Sun-pharma and Bristol-Myers Squibb and travel support from Sunpharma, Takeda, and Sanofi, outside the submitted work. Alpaslan Tasdogan declares no conflict of interest. Dirk Schadendorf is a consultant/scientific advisor to Array, Pfizer, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, MSD, Sanofi-Aventis, Neracare, Immunocore, Replimune, Daiichi-Sanyo, Labcorp, InFlarX, AstraZeneca, OncoSec, Merck-EMD, Nektar, Philogen, Pierre-Fabre, and Sun Pharma. In addition, Dirk Schadendorf has received institutional funding for research grants from Merck, Amgen, Novartis, MSD, Array, and Roche. Selma Ugurel declares research support from Bristol Myers Squibb and Merck Serono; speakers and advisory board honoraria from Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Merck Serono, and Novartis, and travel support from Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Pierre Fabre. Joachim Dissemond declares no conflict of interest. Wiebke Sondermann received travel support for participation in congresses and / or (speaker) honoraria as well as research grants from medi GmbH Bayreuth, Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, GSK, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, and UCB outside of the present publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-59426-4.

References

- 1.Ko CJ, Braverman I, Sidlow R, Lowenstein EJ. Visual perception, cognition, and error in dermatologic diagnosis: Key cognitive principles. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019;81:1227–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.10.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowenstein EJ. Dermatology and its unique diagnostic heuristics. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018;78:1239–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al Ghazal P, et al. Evaluation of the Essen rotary as a new technique for bacterial swabs: results of a prospective controlled clinical investigation in 50 patients with chronic leg ulcers. Int. Wound J. 2014;11:44–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2012.01036.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prast-Nielsen S, et al. Investigation of the skin microbiome: Swabs versus biopsies. Br. J. Dermatol. 2019;181:572–579. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salmanton-Garcia J, et al. The current state of laboratory mycology and access to antifungal treatment in Europe: A European confederation of medical mycology survey. Lancet Microbe. 2023;4:e47–e56. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00261-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wickes BL, Wiederhold NP. Molecular diagnostics in medical mycology. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:5135. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07556-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elston DM, Stratman EJ, Miller SJ. Skin biopsy: Biopsy issues in specific diseases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016;74:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fenton A, et al. Medical students’ ability to diagnose common dermatologic conditions in skin of color. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020;83:957–958. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tripathi R, Knusel KD, Ezaldein HH, Scott JF, Bordeaux JS. Association of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics with differences in use of outpatient dermatology services in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1286–1291. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol. Clin. 2012;30:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta R, Ibraheim MK, Dao H, Jr, Patel AB, Koshelev M. Assessing dermatology resident confidence in caring for patients with skin of color. Clin. Dermatol. 2021;39:873–878. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cline A, et al. Multiethnic training in residency: A survey of dermatology residents. Cutis. 2020;105:310–313. doi: 10.12788/cutis.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adelekun A, Onyekaba G, Lipoff JB. Skin color in dermatology textbooks: An updated evaluation and analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021;84:194–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gregersen DM, Elsner P. Ethnic diversity in German dermatology textbooks: Does it exist and is it important? A mini review. J. Dtsch Dermatol. Ges. 2021;19:1582–1589. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plewig G, Ruzicka T, Kaufmann R, Hertl M. Braun-Falco’s Dermatologie, Venerologie und Allergologie. Springer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peter Fritsch TS. Dermatologie Venerologie. Springer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson-Richards D, Pandya AG. Dermatology Atlas for Skin of Color. Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmeller W, Bendick C, Stingl P. Dermatosen aus drei Kontinenten: Bildatlas der vergleichenden Dermatologie. Schattauer Verlag; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta AK, Chaudhry M, Elewski B. Tinea corporis, tinea cruris, tinea nigra, and piedra. Dermatol. Clin. 2003;21:395–400. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(03)00031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leung AK, Lam JM, Leong KF, Hon KL. Tinea corporis: An updated review. Drugs Context. 2020 doi: 10.7573/dic.2020-5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, Barker J. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397:1301–1315. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32549-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hölsken S, Krefting F, Schedlowski M, Sondermann W. Common fundamentals of psoriasis and depression. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2021;101:adv00609. doi: 10.2340/actadv.v101.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krefting F, Holsken S, Moelleken M, Dissemond J, Sondermann W. Randomized clinical trial of compression therapy of the lower legs in patients with psoriasis. Dermatologie (Heidelb) 2023 doi: 10.1007/s00105-023-05155-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilms L, Wessollek K, Peeters TB, Yazdi AS. Infections with Herpes simplex and Varicella zoster virus. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2022;20:1327–1351. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berke R, Singh A, Guralnick M. Atopic dermatitis: An overview. Am. Fam. Phys. 2012;86:35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, Kabashima K, Irvine AD. Atopic dermatitis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2018;4:1. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0001-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanghetti EA. The role of inflammation in the pathology of acne. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2013;6:27–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grunwald P, Mockenhaupt M, Panzer R, Emmert S. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: Diagnosis and treatment. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2020;18:547–553. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sangha AM. Dermatological conditions in SKIN OF COLOR-: Managing atopic dermatitis. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2021;14:S20–S22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finlay AY, Griffiths TW, Belmo S, Chowdhury MMU. Why we should abandon the misused descriptor ‘erythema’. Br. J. Dermatol. 2021;185:1240–1241. doi: 10.1111/bjd.20660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olson RL, Gaylor J, Everett MA. Skin color, melanin, and erythema. Arch. Dermatol. 1973;108:541–544. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1973.01620250029008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.GomezMoyano E, MartinezPilar L, MartinezGarcia S, Simonsen S. Multiple hyperpigmented patches on a dark-skinned patient. Aust. Fam. Phys. 2017;46:48–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaufman BP, Alexis AF. Psoriasis in skin of color: Insights into the epidemiology, clinical presentation, genetics, quality-of-life impact, and treatment of psoriasis in non-white racial/ethnic groups. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2018;19:405–423. doi: 10.1007/s40257-017-0332-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khanna R, Khanna R, Desai SR. Diagnosing Psoriasis in skin of color patients. Dermatol. Clin. 2023;41:431–434. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2023.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmader K, George LK, Burchett BM, Pieper CF, Hamilton JD. Racial differences in the occurrence of herpes zoster. J. Infect. Dis. 1995;171:701–704. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diep D, et al. Stevens–Johnson syndrome in a patient of color: A case report and an assessment of diversity in medical education resources. Cureus. 2022;14:e22245. doi: 10.7759/cureus.22245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu N, et al. Racial disparities in the risk of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis as urate-lowering drug adverse events in the United States. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buslau M. Case report: TEN in a patient with black skin–blister fluid for rapid diagnosis. Dermatol. Online J. 2008;14:14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adawi W, Cornman H, Kambala A, Henry S, Kwatra SG. Diagnosing atopic dermatitis in skin of color. Dermatol. Clin. 2023;41:417–429. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2023.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poladian K, De Souza B, McMichael AJ. Atopic dermatitis in adolescents with skin of color. Cutis. 2019;104:164–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pouget ER, Kershaw TS, Blankenship KM, Ickovics JR, Niccolai LM. Racial/ethnic disparities in undiagnosed infection with herpes simplex virus type 2. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2010;37:538–543. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181d9042e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alexis AF. Acne vulgaris in skin of color: Understanding nuances and optimizing treatment outcomes. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:s61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pathmarajah P, et al. Acne vulgaris in skin of color: A systematic review of the effectiveness and tolerability of current treatments. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2022;15:43–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor SC, Cook-Bolden F, Rahman Z, Strachan D. Acne vulgaris in skin of color. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2002;46:S98–106. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abdel-Rahman SM, et al. The prevalence of infections with Trichophyton tonsurans in schoolchildren: The CAPITIS study. Pediatrics. 2010;125:966–973. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodriguez-Cerdeira C, et al. A systematic review of worldwide data on tinea capitis: analysis of the last 20 years. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021;35:844–883. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frazier WT, Proddutur S, Swope K. Common dermatologic conditions in skin of color. Am. Fam. Phys. 2023;107:26–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duhard E, Calvet C, Mariotte N, Tichet J, Vaillant L. Prevalence of longitudinal melanonychia in the white population. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 1995;122:586–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kopf AW, Waldo E. Melanonychia striata. Australas J. Dermatol. 1980;21:59–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1980.tb00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leyden JJ, Spott DA, Goldschmidt H. Diffuse and banded melanin pigmentation in nails. Arch. Dermatol. 1972;105:548–550. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1972.01620070020007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kumar GR, Madhavi S, Karthikeyan K, Thirunavakarasu MR. Role of clinical images based teaching as a supplement to conventional clinical teaching in dermatology. Indian J. Dermatol. 2015;60:556–561. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.169125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Statistisches Bundesamt. Mikrozensus: Bevölkerung nach Einwanderungsgeschichte—Endergebnisse 2021. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Migration-Integration/Publikationen/Downloads-Migration/statistischer-bericht-einwanderungsgeschichte-end-5122126217005.html

- 53.EOTO: Each one Teach one e. V. 2023. https://explorer.afrozensus.de/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.