Abstract

The provision of family planning services has important health benefits for the U.S. population. Approximately 25 million women in the U.S. receive contraceptive services annually and 44 million make at least one family planning–related clinical visit each year. These services are provided by private clinicians, as well as publicly funded clinics, including specialty family planning clinics, health departments, Planned Parenthoods, community health centers, and primary care clinics. Recommendations for providing quality family planning services have been published by CDC and the Office of Population Affairs of the DHHS. This paper describes the process used to develop the women’s clinical services portion of the new recommendations and the rationale underpinning them. The recommendations define family planning services as contraceptive care, pregnancy testing and counseling, achieving pregnancy, basic infertility care, sexually transmitted disease services, and preconception health. Because many women who seek family planning services have no other source of care, the recommendations also include additional screening services related to women’s health, such as cervical cancer screening. These clinical guidelines are aimed at providing the highest-quality care and are designed to establish a national standard for family planning in the U.S.

Introduction

According to IOM, the provision of family planning services has important benefits for the health of individuals, families, communities, and the nation.1 Family planning services are intended to help individuals and couples achieve their desired family size, as well as the timing and spacing of their children. Such services include contraceptive care to help prevent unintended pregnancy, as well as pregnancy testing; basic infertility counseling; and infertility prevention through sexually transmitted disease (STD) screening and treatment. Approximately 25 million women in the U.S. receive contraceptive services annually and 44 million make at least one family planning–related clinical visit each year.2 The majority of women receive family planning–related services from private clinicians, but publicly funded clinics play an important role for poor and underserved women.2 Clinics that provide publicly funded family planning services include public health departments, Planned Parenthoods, hospital clinics, and community clinics, including Federally Qualified Health Centers.3 Primary care clinics accepting Medicaid clients also provide a large source of publicly funded family planning services. Public funds for family planning services include federal, state, and local sources.

Title X, a federally funded program of the U.S. Public Health Service Act, which is administered under the DHHS Office of Population Affairs (OPA), has set the standard of care for family planning services in the U.S. for several decades. Original Title X family planning guidelines were established in 1970, updated in 1980, and most recently updated in 2001. In 2006, in an effort to reassess Title X’s scope of services, objectives, and operational requirements, OPA requested an independent evaluation of the Title X program by the IOM.1 The findings from this report emphasized the important role of Title X in setting a national standard of care for family planning services, but also highlighted the importance of making clinical guidelines as evidence based as possible and inclusive of guidelines for reproductive health–related services from professional organizations such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG); Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine; and American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). The report also stressed the importance of making the process of developing clinical guidelines transparent, ensuring that input was obtained from experts representing clinicians, behaviorists, and other public health specialists, and upholding the original Title X program goals of helping women and couples meet their reproductive life goals.

In 2010, CDC and OPA collaborated on the development of updated, evidence-based clinical recommendations for quality family planning (QFP) services, which are intended to serve as the standard of care for all providers of family planning services: “Providing Quality Family Planning Services: Recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs.”4 The conceptual framework used in generating the QFP guidelines was the IOM’s definition of quality of care, that is, care that is safe, effective, client centered, timely, accessible, efficient, equitable, and offering value.5 Additionally, the process was aimed at producing a single document that included the multidimensional aspects of family planning care, including contraceptive care, pregnancy testing and counseling, basic infertility services, preconception health services, STD services, and other related preventive health services. This paper describes the steps taken to define family planning clinical services for women and the specific screening components related to the medical history, physical examination, and laboratory tests for each family planning clinical service. The term “service” used in this paper refers to the reason why the client has come to the clinic (e.g., contraceptive care, pregnancy testing, infertility services); a “screening component” describes what should be performed by the clinician to fulfill the service (e.g., medical history, blood pressure, urine pregnancy test). Processes to develop other recommendations included in the QFP (clinical recommendations for men, contraceptive counseling and education, serving adolescents, and quality improvement) are described elsewhere in this supplement.

Methods

During approximately 12 months in 2011, CDC and OPA conducted several activities to determine what clinical services should be included in provision of family planning for women and what specific screening components within the medical history, physical examination, and laboratory tests should be offered to fulfill those services.

Compiling Existing Guidelines Associated With Clinical Services for Women

Through a multistage process, experts at CDC and OPA compiled existing professional medical organizations’ and federal agencies’ guidelines on clinical screening components that might be included in a family planning visit for women. The compilation of a list of individual clinical screening components for women was based on the 2001 Title X clinical guidelines and existing guidance for routine clinical services by several major national medical organizations, including various history or screening questions, physical assessment, laboratory tests, and counseling topics. The focus of this compilation was solely on screening components because guidelines for clinical management of other conditions can be found elsewhere and may be handled by referral to a specialist. Two practicing clinicians, an obstetrician/gynecologist and family physician at CDC, conducted a comprehensive review of existing guidelines from major national professional organizations and federal agencies, identified relevant guidelines for routine clinical screening, and summarized this information for each component. The criteria used to select the organizations from which the guidelines were sought were as follows:

The entity was a federal agency or major professional medical organization representing an established medical discipline.

The entity’s guidelines were based on independent review of evidence or on expert review, the entity was considered a reliable resource within that medical discipline, and the entity did not simply cite another organization’s recommendations.

The entity’s guidelines were developed in and for the U.S.

Appendix A lists the 31 professional organizations and federal agencies from which information was collected.

Organizations outside the U.S. were generally not considered, except in cases in which U.S.-based clinical guidelines were lacking or when comparisons of certain guidelines were desired. Several Canadian organizations, such as the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada and the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health, provided useful comparisons to U.S. guidelines. Within CDC, topic experts also contributed to summarizing guidelines for certain clinical screening components. For example, experts in the Division of Sexually Transmitted Disease Prevention helped summarize guidelines from major organizations regarding STD/HIV screening, experts from the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control helped review cancer screening guidelines, and experts from the Division of Violence Prevention provided a summary of guidelines regarding screening for intimate partner and other forms of violence.

CDC then compiled a compendium summarizing the guidelines of these professional organizations and federal agencies. For each clinical screening component, the compendium outlined the guidelines as originally stated by each organization or agency, followed by a table synthesizing the body of guidelines, their rationales, and whether conflicting guidelines between the organizations or agencies existed. Additionally, a summary describing the methods used by each professional organization or federal agency in generating their particular guideline was also contained in the compendium.

Choosing Clinical Screening Services Through a Technical Panel Review

In July 2011, CDC and OPA convened a technical panel of experts in family planning services and women’s health, which consisted of 15 clinical experts in women’s health, including practicing obstetricians/gynecologists, family or adolescent physicians, women’s health advanced practice clinicians, and representatives from various government and non-government organizations (Appendix B). The compendium of screening guidelines was provided to the panelists prior to the meeting. During the meeting, panelists were asked to consider the following questions:

How should “clinical family planning services” be defined?

How should each clinical service be delivered?

Should any related clinical services be recommended?

What clinical services should not be provided?

Drafting the Clinical Recommendations for Women

Upon completion of the technical panel meeting, CDC and OPA integrated the panel’s feedback regarding each clinical screening service into a draft of the clinical recommendations that are recommended in the QFP guidelines. The draft included an overall scheme of different family planning clinical services, and the recommended clinical screening components within each family planning service. These draft recommendations were then presented to an expert work group of panelists in September 2011 (Appendix C). The expert work group was made up of 17 experts, consisting of practicing obstetricians/gynecologists, family or adolescent physicians, women’s health advanced practice clinicians, and representatives from government and non-government organizations. Some of the members who had participated in the expert work group also participated on the technical panel for clinical services for women.

During the meeting, work group members were asked to consider whether the overall scheme proposed for the QFP guidelines was feasible and relevant to family planning clinical services; they were also asked to consider whether this scheme increased or decreased barriers to care. Other areas for feedback by the work group included whether the screening components were appropriate for each type of family planning service, as well as the level of detail needed on each screening component for family planning clinicians. Feedback from the first expert work group meeting was further integrated into the draft recommendations. Several work group experts remained available for clarifications for the guideline draft revisions. The expert work group met again in February 2012 to further discuss and provide feedback about the definition of family planning services and the recommended screening components to be included in the QFP guidelines. At the second meeting, they used the following criteria to consider the recommendations:

the quality of the evidence;

the positive and negative consequences of implementing the recommendations on health outcomes, costs or cost savings, and implementation challenges; and

the relative importance of these consequences (e.g., the recommendation’s ability to have a large impact on health outcomes may be weighed more than logistical challenges of implementing it).6

Decision Process

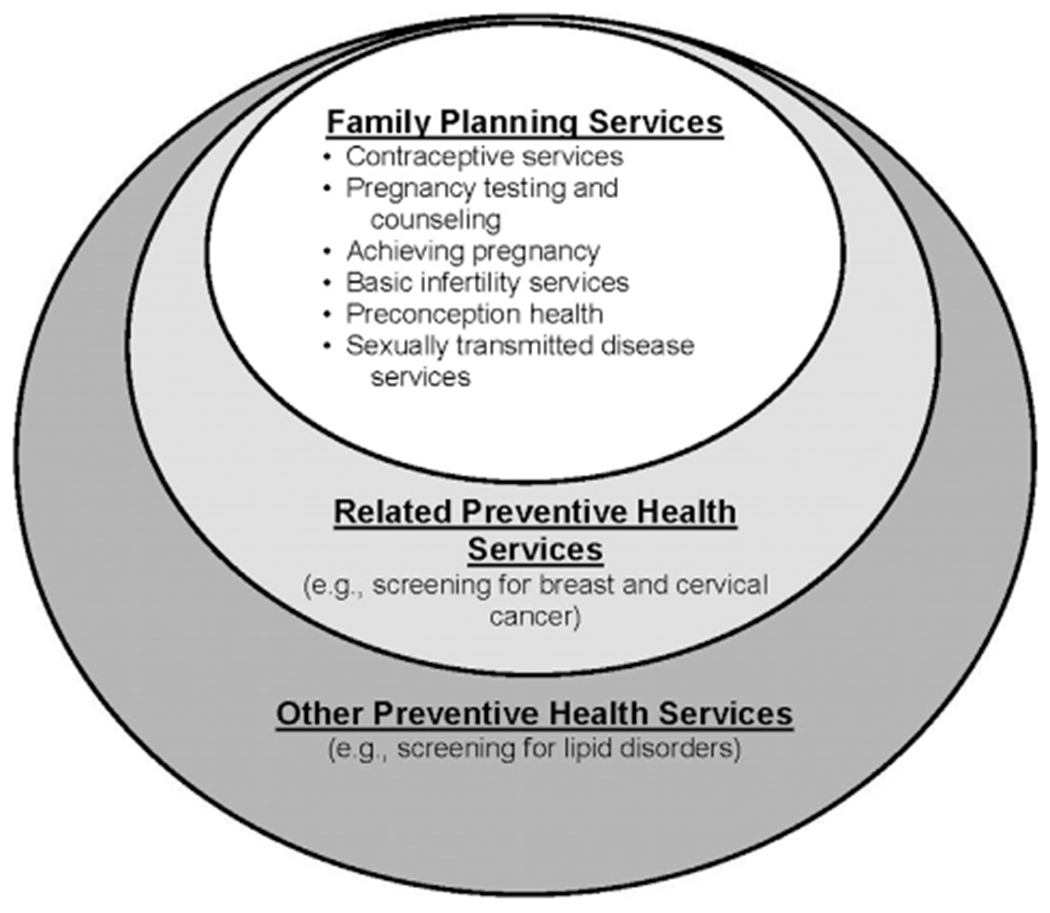

Input on several key topics was obtained, which CDC and OPA used to make key decisions about recommendations in QFP. A first key decision was to determine which specific clinical services should be recommended when caring for a client in need of family planning services. All of the expert working group members were in agreement regarding which clinical services to include under the umbrella of family planning services. Family planning services were considered a compilation of services embedded within a broader framework of preventive health services, which were divided into three main categories: family planning services, related preventive health services, and other preventive health services (Figure 1). Family planning services, noted within the inner circle of Figure 1, were defined as the provision of contraception, pregnancy testing and counseling, assistance to clients who want to become pregnant, basic infertility services, preconception health services, and STD services. Services related to preventing and achieving pregnancy are essential aspects of helping a woman realize her childbearing goals. The decision to include preconception health and STD services within the family planning service framework was made because of the recognition of their importance in prevention of pregnancy complications and maintenance of women’s health throughout the reproductive lifespan, even among women who choose to not bear children. All of the expert working group members agreed on the importance of including preconception health as a core family planning service. Related preventive health services were defined as services that were considered to be beneficial to reproductive health, closely linked to family planning services, and appropriate to deliver in the context of a family planning visit, but did not directly contribute to achieving or preventing pregnancy. Other preventive health services were defined as essential preventive health services for women that have been recommended by the IOM but were not included within family planning or related preventive health services, as well as preventive services for men that may be considered in the context of a family planning visit.

Figure 1.

Family planning–related and other preventive health services.

A second major set of decisions was how to provide each of the family planning services listed above, by determining which screening components should be included. A challenge was that there were often several, sometimes inconsistent, clinical guidelines for each type of screening component. For some of the screening components, no decisions were needed because guidelines from different organizations were in agreement (e.g., gonorrhea screening)7 or guidelines were identified from only one organization (e.g., immunization provision).8 For other addressed screening components, guidelines from federal and professional organizations differed with respect to necessity or periodicity. As a result, the following hierarchy was developed for selecting among them: the technical panel adopted guidelines from CDC, if they existed (e.g., HIV screening),9 or an A or B recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) if no CDC guidelines existed. A USPSTF grade A is defined as a recommended service because there is high certainty that the net benefit is substantial. A USPSTF grade B is defined as a recommended service because there is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial.10 This hierarchy was chosen because CDC recommendations generally focus on individuals at higher risk for disease, whereas USPSTF recommendations target primary care clinicians and health systems. If no federal recommendations existed, guidelines from professional organizations were included as resources, and the AAP’s Bright Futures guidelines were used as the primary source of recommendations for adolescents (e.g., screening for tobacco use among adolescents).11 For some of the addressed screening components, no guidelines from federal or professional organizations were identified or the component had a grade I recommendation from the USPSTF; however, CDC and OPA determined that the component was integral to the family planning service and was necessary to include in the guidelines (e.g., conducting a sexual health assessment as part of contraceptive provision or screening for drug use as part of preconception care). A USPSTF grade I is defined as current evidence that is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harm of the service.10

Below is a summary of key decisions that CDC and OPA made based on expert input when developing recommendations for service provision for each family planning service outlined in QFP:

Contraceptive services. CDC recommendations on contraceptive safety and management were considered central sources underpinning the recommendations for how to provide contraceptive services.12,13 In addition, other important aspects of how to provide contraceptive services (e.g., counseling and education, serving adolescent clients) were developed after conducting several systematic reviews of the evidence and consulting with experts in the topic (these processes are described elsewhere in this supplement).

Pregnancy testing and counseling. No CDC or USPSTF recommendations exist for pregnancy testing and counseling clients about their options. The recommendations were therefore based on the guidelines of professional medical associations such as ACOG and AAP, relevant Title X statute and regulation, and the advice of subject matter experts.

Achieving pregnancy. No CDC or USPSTF recommendations exist for helping clients achieve pregnancy. The recommendations were therefore based on the guidelines of professional medical associations such as the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) and the advice of subject matter experts.

Basic infertility services. No CDC or USPSTF recommendations exist for providing basic infertility services. The recommendations were therefore based on the guidelines of professional medical associations such as ASRM and the advice of subject matter experts.

Preconception health services. CDC recommendations on preconception health served as a central source underpinning the recommendations for how to provide these services.14 Priority preconception health screening components were identified by including a component only if the Select Panel on Preconception Care had assigned an A or B recommendation to that component (i.e., it had good or fair evidence to support it).14 Components that the Select Panel on Preconception Care deemed to have insufficient evidence or evidence against were not included. Because CDC recommendations do not describe how to provide each screening component (e.g., with what periodicity or for what risk groups), the USPSTF recommendations were cited for each selected preconception health component. If no USPSTF recommendation existed, the guidelines of major professional organizations were cited.

Sexually transmitted disease services. CDC recommendations on STD treatment and HIV testing were used as the basis for the recommendations on how to provide STD services.7

The specific screening components included in each service type are shown in Table 1. Although the recommendations recognize the need to be comprehensive, they acknowledge the importance of not creating barriers to family planning services, such as requesting screening tests that may be important to a woman’s health, but not necessarily related to the contraceptive method she is seeking to use. The recommendations also recognize that all screening components may not be able to be provided in one visit; this may be particularly true for preconception health services.

Table 1.

Checklist of Family Planning and Related Preventive Health Services for Women

| Screening components | Family planning services (provide services in accordance with the appropriate clinical recommendation) | Related preventive health services | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contraceptive servicesa | Pregnancy testing and counseling | Basic infertility services | Preconception health services | STD servicesb | ||

| History | ||||||

| Reproductive life planc | Screen | Screen | Screen | Screen | Screen | |

| Medical historyc,d | Screen | Screen | Screen | Screen | Screen | Screen |

| Current pregnancy statusc | Screen | |||||

| Sexual health assessmentc,d | Screen | Screen | Screen | Screen | ||

| Intimate partner violencec,d,e | Screen | |||||

| Alcohol and other drug usec,d,e | Screen | |||||

| Tobacco usec,e | Screen (combined hormonal methods for clients aged ≥35 years) | Screen | ||||

| Immunizationsc | Screen | Screen for HPV and HBVf | ||||

| Depressionc,e | Screen | |||||

| Folic acidc,e | Screen | |||||

| Physical examination | ||||||

| Height, weight, and BMIc,e | Screen (hormonal methods)g | Screen | Screen | |||

| Blood pressurec,e | Screen (combined hormonal methods) | Screenf | ||||

| Clinical breast examd | Screen | Screenf | ||||

| Pelvic examc,d | Screen (initiating diaphragm or IUD) | Screen (if clinically indicated) | Screen | |||

| Signs of androgen excessd | Screen | |||||

| Thyroid examd | Screen | |||||

| Laboratory testing | ||||||

| Pregnancy testd | Screen (if clinically indicated) | Screen | ||||

| Chlamydiac,e | Screenh | Screenf | ||||

| Gonorrheac,e | Screenh | Screenf | ||||

| Syphilisc,e | Screenf | |||||

| HIV/AIDSc,e | Screenf | |||||

| Hepatitis Cc,e | Screenf | |||||

| Diabetesc,e | Screenf | |||||

| Cervical cytologye | Screenf | |||||

| Mammographye | Screen f | |||||

This table presents highlights from CDC’s recommendations on contraceptive use. However, providers should consult the following guidelines when treating individual patients to obtain more detailed information about specific medical conditions and characteristics (Source: CDC. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use 2010. MMWR. 2010;59 [No.RR-4]).

STD services also promote preconception health, but are listed separately here to highlight their importance in the context of all types of family planning visits. The services listed in this column are for women without symptoms suggestive of an STD.

CDC recommendation.

Professional medical organization recommendation.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation.

Indicates that screening is suggested only for those persons at highest risk or for a specific subpopulation with high prevalence of an infection or condition.

Weight (BMI) measurement is not needed to determine medical eligibility for any methods of contraception because all methods can be used (U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria 1) or generally can be used (U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria 2) among obese women (Source: CDC. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use 2010. MMWR. 2010;59 [No. 4]). However, measuring weight and calculating BMI at baseline might be helpful for monitoring any changes and counseling women who might be concerned about weight change perceived to be associated with their contraceptive method.

Most women do not require additional STD screening at the time of IUD insertion if they have already been screened according to CDC’s STD treatment guidelines (Source: CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR. 2010;59 [RR-12]. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/). If a woman has not been screened according to guidelines, screening can be performed at the time of IUD insertion, and insertion should not be delayed. Women with purulent cervicitis or current chlamydial infection or gonorrhea should not undergo IUD insertion (U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria 4), and women who have a very high individual likelihood of STI exposure (e.g., those with a currently infected partner) generally should not undergo IUD insertion (U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria 3) (Source: CDC. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59[RR-4]). For these women, IUD insertion should be delayed until appropriate testing and treatment occurs.

HBV, hepatitis B virus; HPV, human papillomavirus; IUD, intrauterine device; STD, sexually transmitted disease; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

A third major decision was related to additional preventive services noted within the outer circles of the framework in Figure 1. There was recognition that, for many women, the family planning clinic may be their only contact with the healthcare system.15 Although some screening components may not be directly related to family planning, the technical panel determined that some associated preventive services were of critical importance to a woman’s health, and provision in a family planning setting would be of great benefit. Such screening components for women included clinical breast examination, cervical cytology, and mammography (Table 1). For such components, the expert work group again determined that the guidelines should follow federal recommendations, if they existed (e.g., mammography screening),16 or professional guidelines, if no federal recommendations existed or the USPSTF had determined the evidence was insufficient to recommend (e.g., clinical breast examination).17,18 The technical panel did not provide feedback on many other components that are important in preventive care for women but may be out of the scope of a family planning clinic (e.g., colorectal cancer screening). The guidelines suggest that for women who do not have another source of primary care, these services may be available on site or by referral.

Finally, decisions were made about which screening components should not be included in the context of family planning provision. Such components included those that the USPSTF recommends against (e.g., breast self-examination or routine serologic screening for herpes simplex virus in asymptomatic women).16 There were also several physical examination and laboratory components for which no guidelines were identified to support their performance in the context of family planning services (e.g., pulse; heart, lung, abdominal, rectal, and skin exams; cholesterol; urinalysis; hemoglobin; and vaginal wet mount); therefore, these components were not included. Though these components may be important in other circumstances, the decision to exclude these components was based only on the relationship between the screening component and family planning services.

Comment

Quality family planning care is critical to providing optimal health care for women. To date, there has been no national standard for evidence-based provision of comprehensive family planning services in the U.S. This paper describes the process of developing recommendations for delivering comprehensive family planning clinical services to women as outlined in the CDC and OPA QFP document.4 The QFP recommendations are designed to establish a national standard of care for, and improve the quality of, family planning services in the U.S. The strength of these recommendations is their grounding in the best available guidelines from federal and relevant professional organizations, although evidence reviews were not performed by CDC and OPA for each clinical service included in the guidelines. Many of the organizations generated their guidelines based on systematic or comprehensive literature reviews and rigorous, well-defined processes. The vast majority of the recommendations are taken from CDC or USPSTF guidelines.

The QFP recommendations define family planning holistically and include a range of preventive services with an emphasis on a subset of services that promote preconception health and other closely related health services (i.e., breast and cervical cancer screening). In an ideal world, there would be adequate time to provide all these services in a timely and on a routine basis; however, the reality of many client encounters means that it may often be challenging to deliver all recommended services. In addition, recent changes in recommendations for cervical cancer screening may decrease the frequency of certain preventive visits. As a result, providers will need to make efforts to integrate preconception and related health services into all types of family planning visits in order to meet current standards of care. Operational research is needed to help providers find optimal ways to do this.

Limitations

One of the main limitations of the recommendations in the QFP guidance is that, as with all evidence-based guidelines, gaps exist in available evidence on which to base recommendations. In the absence of direct evidence, organizations must rely on indirect evidence, group consensus, or expert opinion to formulate guidance. Further research should continue to establish the evidence base for family planning services and explore how to operationalize these services in an effective and efficient manner in the healthcare setting.

Conclusions

Family planning services are critical to the health of women, as they allow them to achieve the desired number and spacing of pregnancies and give birth to healthy infants if and when they choose to do so. The QFP recommendations represent a comprehensive approach to family planning care for U.S. women based on the best available guidelines from federal and relevant professional organizations. The QFP recommendations should assist providers in delivering high-quality family planning care and improving the health of U.S. women.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Publication of this article was supported by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Office of Population Affairs (OPA).

The authors acknowledge Arik Marcell from Johns Hopkins University for his helpful comments on earlier drafts. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC or the Office of Population Affairs.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Footnotes

Appendix

Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.023.

References

- 1.IOM. A. Review of the HHS Family Planning Program: Missions, Management, and Measurement of Results. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frost JJ. U.S. Women’s Use of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services: Trends, Sources of Care and Factors Associated with Use, 1995–2010. New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2013. www.guttmacher.org/pubs/sources-of-care-2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frost JJ, Gold RB, Bucek A. Specialized family planning clinics in the United States: why women choose them and their role in meeting women’s health care needs. Women’s Health Iss. 2012;22:e519–e525. 10.1016/j.whi.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gavin L, Moskosky S, Carter M, et al. Providing quality family planning services: recommendations of CDC and the U.S. office of population affairs. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(RR-04):1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, IOM. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies of Science, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. Going from evidence to recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:1049–1051. 10.1136/bmj.39493.646875.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CDC. Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices Recommendations. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 9.CDC. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Grade Definitions After July 2012. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/grade-definitions#grade-definitions-after-july-2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagan JR, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, eds. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. 3rd ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.CDC. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR–4):1–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CDC. U.S. selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2013. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62:1–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jack BW, Atrash H, Coonrod DV, Moos MK, O’Donnell J, Johnson K. The clinical content of preconception care: an overview and preparation of this supplement. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:S266–S279. 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frost J. U.S. Women’s Reliance on Publicly Funded Family Planning Clinics as Their Usual Source of Medical Care. 2008 Research Conference on the National Survey of Family Growth; 2008 October 16-17, 2008; Hyattsville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstopics.htm.

- 17.American Cancer Society guidelines. www.cancer.org/index.

- 18.Committee opinion no. 483: primary and preventive care: periodic assessments. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1008–1015. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318219226e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.