Abstract

Background

Cough is often distressing for patients with pneumonia. Accordingly they often use over‐the‐counter (OTC) cough medications (mucolytics or cough suppressants). These might provide relief in reducing cough severity, but suppression of the cough mechanism might impede airway clearance and cause harm.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy of OTC cough medications as an adjunct to antibiotics in children and adults with pneumonia.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL 2013, Issue 12, MEDLINE (January 1966 to January week 2, 2014), OLDMEDLINE (1950 to 1965), EMBASE (1980 to January 2014), CINAHL (2009 to January 2014), LILACS (2009 to January 2014) and Web of Science (2009 to January 2014).

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in children and adults comparing any type of OTC cough medication with placebo, or control medication, with cough as an outcome and where the cough is secondary to acute pneumonia.

Data collection and analysis

We independently selected trials for inclusion. We extracted data from these studies, assessed them for methodological quality without disagreement and analyzed them using standard methods.

Main results

There are no new trials to include in this review update. Previously, four studies with a total of 224 participants were included; one was performed exclusively in children and three in adolescents or adults. One using an antitussive had no extractable pneumonia‐specific data. Three different mucolytics (bromhexine, ambroxol, neltenexine) were used in the remaining studies, of which only two had extractable data. They demonstrated no significant difference for the primary outcome of 'not cured or not improved' for mucolytics. A secondary outcome of 'not cured' was reduced (odds ratio (OR) for children 0.36, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.16 to 0.77; number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) at day 10 = 5 (95% CI 3 to 16) and OR 0.32 for adults (95% CI 0.13 to 0.75); NNTB at day 10 = 5 (95% CI 3 to 19)). In a post hoc analysis combining data for children and adults, again there was no difference in the primary outcome of 'not cured or not improved' (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.80) although mucolytics reduced the secondary outcome 'not cured' (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.60; NNTB 4, 95% CI 3 to 8). The risk of bias was low or unclear.

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence to decide whether OTC medications for cough associated with acute pneumonia are beneficial. Mucolytics may be beneficial but there is insufficient evidence to recommend them as an adjunctive treatment for acute pneumonia. This leaves only theoretical recommendations that OTC medications containing codeine and antihistamines should not be used in young children.

Keywords: Adolescent; Adult; Child; Humans; Acute Disease; Anti‐Bacterial Agents; Anti‐Bacterial Agents/therapeutic use; Antitussive Agents; Antitussive Agents/therapeutic use; Chemotherapy, Adjuvant; Chemotherapy, Adjuvant/methods; Cough; Cough/drug therapy; Cough/etiology; Drug Therapy, Combination; Drug Therapy, Combination/methods; Expectorants; Expectorants/therapeutic use; Nonprescription Drugs; Nonprescription Drugs/therapeutic use; Pneumonia; Pneumonia/complications; Pneumonia/drug therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Treatment Outcome

Plain language summary

Over‐the‐counter medications to help reduce cough for children and adults on antibiotics for acute pneumonia

There are many causes of acute cough, one of which is pneumonia. Cough is burdensome and impairs quality of life. Over‐the‐counter (OTC) medications are commonly purchased and used by patients, and are recommended by healthcare staff as additional medications in the treatment of pneumonia. There are many classes of OTC medications for cough, such as mucolytics (medications that can reduce the thickness of mucus) and antitussives (medications that suppress cough). This review aims to balance the possible benefits of these agents with their potential risks.

In this review we found four studies with a total of 224 participants that were suitable for inclusion; one was performed exclusively in children and three in adolescents or adults. However, data could only be obtained from two studies; both studies used mucolytics (ambroxol and bromhexine) in conjunction with antibiotics. Combining these two studies, the rate of cure or improvement in cough of people who received mucolytics was similar to those who did not. However, in the secondary analysis, children who received a mucolytic were more likely to be cured of cough (the number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) at day 10 was 5 for children and 4 for adults). There were no reported increased adverse events in the treatment group.

The range of possible adverse events associated with OTC medications for cough is wide and includes minimal adverse events (such as with the use of honey) to serious adverse events, such as altered heart rate patterns, drowsiness and death in young children. The studies included in this review did not report any detectable increase in adverse events. There were no obvious biases in the studies.

This review has substantial limitations due to the unavailability of data from studies. Also there are no studies of other common OTC medications used for cough, such as antihistamines and antitussives.

Thus, there is insufficient evidence to draw any definitive conclusions on the role of OTC medications taken as an additional treatment for cough associated with acute pneumonia. Mucolytics may be beneficial but the lack of consistent evidence precludes recommending the routine use of mucolytics as an addition in the treatment of troublesome cough associated with pneumonia in children or adults. The evidence is current to January 2014.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Mucolytics as an adjunct to antibiotics to reduce cough in acute pneumonia in children and adults | ||||||

|

Patient or population: children and adults with acute pneumonia Settings: any Intervention: mucolytics (and antibiotics)1 Comparison: antibiotics | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Mucolytics | |||||

| Number of people who had not improved or had not been cured (follow‐up: 7 to 10 days) | 16 per 100 | 14 per 100 (7 to 26) | OR 0.85 (0.4 to 1.8) | 221 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,5 | Fewer people represents a benefit |

| Cough score Scale from: 0 (absent) to 3 (very severe) (follow‐up: 3 days) | The mean cough score in the control groups was 1.45 | The mean cough score in the intervention groups was 0.25 lower (0.33 to 0.17 lower) | 120 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3,4 | Data for children only | |

| Adverse events (follow‐up: 10 days) | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 120 (1) | See comment | 1 study in children provided data specific to participants with pneumonia ‐ there were no adverse events |

| Complications (e.g. medication change) | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | Complications were not measured in the trials |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1In addition to antibiotics, people with pneumonia often use over‐the‐counter (OTC) cough medications when at home or request OTC cough medications when in hospital to suppress an annoying cough. There is a question as to whether suppressing cough may prolong pneumonia. Over‐the‐counter cough medications can include antitussives, expectorants, antihistamine‐decongestants, antihistamines and mucolytics (such as bromhexine, ambroxol and neltenexine).

2Allocation concealment unclear.

3Scale not validated.

4Sparse data.

5Sparse data; confidence interval does not rule out the potential for 'more people' not improved or cured with mucolytics.

Background

Description of the condition

Cough is the most common symptom presenting to general practitioners (Britt 2002; Cherry 2003). Acute cough (duration less than two weeks) (Chang 2006) has multiple causes, including pneumonia. Whatever the cause, attempting to reduce the impact of the symptom of cough is reflected in the billions spent on over‐the‐counter (OTC) cough medications. Cough impairs quality of life (French 2002) and causes significant anxiety to the parents of children (Cornford 1993). Accordingly, patients with pneumonia sometimes self medicate with over‐the‐counter (OTC) cough medications in ambulatory settings, or ask for them in hospital.

Description of the intervention

A Cochrane review showed that antihistamine‐analgesic‐decongestion combinations have some general benefit in adults and older children with the common cold but not in young children (de Sutter 2012). In the management of acute cough, in the ambulatory setting, a Cochrane review found no good evidence for or against the use of OTC medications (Smith 2012). There is no clear benefit of antihistamines (either singly or in combination) in young children for relieving acute cough (de Sutter 2012; Smith 2012). Moreover, they are associated with potentially significant adverse events including altered consciousness, arrhythmia and death (Gunn 2001; Kelly 2004). None of these reviews included patients with pneumonia (Smith 2012). There are also Cochrane reviews on chronic non‐specific cough but this is unrelated to this review, which focuses on acute cough associated with pneumonia.

How the intervention might work

Cough is usually divided into acute or chronic according to its duration and age group. It is defined as chronic if over eight weeks duration in adults, and over three to four weeks in children (Chang 2005). This reflects the different conditions causing chronic cough in different age groups. In contrast, in this review we examined the efficacy of OTC medication for acute cough in acute pneumonia, where the pathophysiological processes (albeit poorly understood) are likely to be the same in children and adults. Methods for determining cough outcomes are similar in adults and children, although these methods remain poorly standardised. Objective measurements of cough include cough frequency and cough sensitivity outcomes, whilst subjective measurements of cough may broadly encompass quality‐of‐life and outcomes based on diaries etc. (Birring 2006; Chang 2003).

Why it is important to do this review

Although OTC cough medications might provide some relief by reducing the severity of the cough, they might also be harmful in prolonging pneumonia (by suppressing the cough reflex, which might cause retention of airway debris). Thus, a systematic review of their benefits or harms is useful to help guide clinical practice.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy of OTC medications for cough as an adjunct to antibiotics in children and adults with pneumonia.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing any type of OTC cough medication with a placebo (or control group) with cough as an outcome and where cough is secondary to acute pneumonia. We excluded quasi‐randomised trials.

Types of participants

We considered studies of both children and adults with cough of less than four weeks in duration that was related to pneumonia. We specifically excluded studies of cough of more than four weeks in duration and cough related to another underlying cardio‐respiratory condition (for example, suppurative lung disease, chronic obstructive airway disease, asthma). However, we considered studies which included cough of mixed aetiologies if data were available for the subgroup of patients with pneumonia.

Types of interventions

RCT comparisons of any type of OTC cough medication as an adjunct therapy to antibiotics. We did not include trials comparing only two or more medications without a placebo comparison group. We included trials that included the use of other medications or interventions if all participants had equal access to such medications (including antibiotics) or interventions.

Types of outcome measures

We attempted to obtain data on at least one of the following outcome measures.

Primary outcomes

Proportion of participants who were not cured or not substantially improved at follow‐up (failure to improve was measured according to the hierarchy listed below in Secondary outcomes).

Secondary outcomes

Proportion of participants who were not cured at follow‐up.

Change in quantitative differences in cough (cough frequency, cough scores, other quantitative outcomes based on cough diary).

Proportion experiencing adverse effects of the intervention (for example, sleepiness, nausea, etc.).

Proportion experiencing complications (for example, requirement for medication change, etc.).

We adopted and recorded individual trial definitions.

As it was likely that studies may have differed in their definitions of cure and improvement, we adopted a hierarchical approach that employed the reported outcome measures. For example, if both an objective measure and a subjective measure of cough frequency were reported, we were to adopt the objective measure in assessing the efficacy of treatment. Our hierarchy of outcome measures was as follows.

Objective measurements of cough indices (cough frequency, cough receptor sensitivity).

Symptomatic (quality of life, Likert scale, visual analogue scale, level of interference of cough, outcomes‐based cough diary): assessed by the patient (adult or child).

Symptomatic (quality of life, Likert scale, visual analogue scale, level of interference of cough, outcomes‐based cough diary): assessed by the parents or carers.

Symptomatic (Likert scale, visual analogue scale, level of interference of cough, outcomes‐based cough diary): assessed by clinicians.

Fever, respiratory rate, oxygen requirement.

Non‐clinical outcomes (chest radiology, white cell count, C‐reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, lung function test (spirometry)).

Eradication of micro‐organism(s) causing the pneumonia.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For this update we searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2013, Issue 12, part of The Cochrane Library,www.thecochranelibrary.com (accessed 22 January 2014), which contains the Acute Respiratory Infections Group's Specialised Register, MEDLINE (January 1966 to January week 2, 2014), OLDMEDLINE (1950 to 1965), EMBASE (1980 to January 2014), CINAHL (2009 to January 2014), LILACS (2009 to January 2014) and Web of Science (2009 to January 2014).

We used the following search strategy to search MEDLINE and CENTRAL. We adapted the search strategy for EMBASE (see Appendix 2), CINAHL (see Appendix 3), LILACS (see Appendix 4) and Web of Science (see Appendix 5).

MEDLINE (OVID) 1 Cough/ 2 cough*.tw. 3 1 or 2 4 exp Pneumonia/ 5 (pneumon* or bronchopneumon*).tw. 6 4 or 5 7 3 and 6 8 exp Antitussive Agents/ 9 antitussiv*.tw,nm. 10 exp Expectorants/ 11 expectorant*.tw,nm. 12 exp Cholinergic Antagonists/ 13 (cholinergic adj2 (blocking or antagonist*)).tw,nm. 14 (anticholinergic* or anti‐cholinergic*).tw,nm. 15 exp Histamine H1 Antagonists/ 16 histamine h1 antagonist*.tw,nm. 17 (antihistamin* or anti‐histamin*).tw,nm. 18 mucolytic*.tw,nm. 19 exp Drug Combinations/ 20 drug combination*.tw. 21 exp Nonprescription Drugs/ 22 ((non prescribed or non‐prescribed or nonprescribed or non prescription* or non‐prescription* or nonprescription*) adj3 (drug* or medicin* or pharmaceut* or medicat*)).tw. 23 (over‐the‐counter* or over the counter or otc).tw. 24 (cough* adj3 (mixture* or suppress* or medicin* or remed* or relief* or formula* or syrup*)).tw. 25 or/8‐24 26 7 and 25

There were no language or publication restrictions.

Searching other resources

We searched the trials registries ClinicalTrials.gov and WHO ICTRP (searched 20 January 2014). We also searched lists of references in relevant publications.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (CCC, ABC) independently reviewed the literature searches to identify potentially relevant trials for full review from the title, abstract or descriptors. We conducted searches of bibliographies and texts to identify additional studies. The same two review authors independently selected trials for inclusion from the full text, using specific criteria. There was no disagreement. A third review author (ACC) was the nominated adjudicator in case of any disagreements.

Data extraction and management

We reviewed trials that satisfied the inclusion criteria and extracted the following information: study setting; year of study; source of funding; patient recruitment details (including number of eligible patients); inclusion and exclusion criteria; other symptoms; randomisation and allocation concealment method; numbers of participants randomised; blinding (masking) of participants, care providers and outcome assessors; dose and type of intervention; duration of therapy; co‐interventions; numbers of patients not followed up; reasons for withdrawals from study protocol (clinical, side effects, refusal and other); details on side effects of therapy and whether intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analyses were possible. We extracted data on the outcomes described previously. It was planned that further information would be requested from the trial authors, where required.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (CCC, ABC) independently performed a potential bias assessment on studies included in the previous review. We described seven components of potential biases under Assessment of reporting biases in our updated review

Measures of treatment effect

We undertook an initial qualitative comparison of all the individually analyzed studies to determine if pooling of results (meta‐analysis) was reasonable. This took into account differences in study populations, inclusion and exclusion criteria, interventions, outcome assessment and estimated effect size. We included the results from studies that met the inclusion criteria and reported any of the outcomes of interest in the subsequent meta‐analyses.

We calculated individual and pooled statistics for continuous outcomes measured on the same metrics as mean differences (MD) and standard mean differences, as indicated, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We combined data for continuous outcomes measured on different metrics, with a standardised mean difference (SMD). We calculated individual and pooled statistics as odds ratio (OR) with 95% CIs for dichotomous variables.

Unit of analysis issues

Had there been any cross‐over studies, we would have calculated mean treatment differences from raw data, extracted or imputed and entered as fixed‐effect generic inverse variance (GIV) outcomes, to provide summary weighted differences and 95% CIs. Only data from the first arm would have been included in a meta‐analysis where data were combined with parallel studies (Elbourne 2002).

Dealing with missing data

We planned to contact trial authors for missing data when the studies were less than 15 years old.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We described any heterogeneity between the study results and tested to see if it reached statistical significance using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). Heterogeneity is considered significant when the P value of the Chi2 test is < 0.10 (Higgins 2011). We would have included the 95% CI estimate using a random‐effects model had there been concerns about statistical heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

In this updated review, in line with the new Cochrane process, we assessed the risk of bias of each study including sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding and reporting of outcome data.

While there are other possible biases (such as publication bias detected by funnel plot) as outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), these were not included.

Data synthesis

We calculated odds ratios (ORs) using a modified ITT analysis for dichotomous outcome variables of each individual study. This analysis assumed that participants not available for outcome assessment had not improved (and probably represented a conservative estimate of effect). We calculated the summary weighted ORs and 95% CI (fixed‐effect model) using the computer program RevMan 2012. We calculated the number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) from the pooled OR and its 95% CI, applied to a specified baseline risk using an online calculator (Cates 2003).

We assumed the cough indices to be normally distributed continuous variables so that the mean difference in outcomes could be estimated (mean difference). We would have estimated the standardised mean difference if studies had reported outcomes using different measurement scales.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned an a priori subgroup analysis for:

children (14 years and younger) versus adolescents and adults (older than 14 years);

hospitalised versus ambulatory settings;

-

classes of OTC cough medications:

antitussives (codeine and derivatives);

expectorants;

mucolytics;

antihistamine‐decongestant combinations;

antihistamines alone;

other drug combinations;

males versus females in adults.

Sensitivity analysis

It was planned that sensitivity analyses be carried out to assess the impact of potentially important factors on the overall outcomes:

study quality;

study size;

variation in the inclusion criteria;

differences in the medications used in the intervention and comparison groups;

differences in outcome measures;

analysis using a random‐effects model;

analysis by 'treatment received';

analysis by 'ITT';

analysis by study design, parallel and cross‐over studies.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

In the first version of this review (Chang 2007), the search identified 238 potentially relevant titles. After reviewing the abstracts, we obtained 21 full‐text papers, included four studies and excluded 17 papers (details are in the Characteristics of excluded studies table). Most were non‐randomised studies or performed without a placebo. A review article was identified in this search (Ida 1997) which described three studies of dimemorfan (a dextromethorphan analogue) not identified using the original search strategy. One of these three studies was described as a placebo‐controlled trial. Unfortunately we were not able to obtain this and there was insufficient details provided in the review article (Ida 1997). Another review paper (Mancini 1996) described three studies, of which one appeared to include patients with acute lower respiratory tract infection (specified as acute bronchitis or bronchoalveolitis but which may have included patients with pneumonia). We attempted to contact the trial authors but were not able to extract data on the subgroup of patients with pneumonia, and thus we excluded the study from further analysis.

In the 2009 update (Chang 2010), we identified two studies (Balli 2007; Titti 2000) on erdosteine (a mucolytic agent) but these were excluded as this is not readily accessible over the counter (details added to the Characteristics of excluded studies table). In the 2011 and 2013 updates, we identified 32 and 49 potential studies respectively but none fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Of note, a study which examined the role of zinc supplementation (Basnet 2012) was excluded as this is not an OTC drug for cough suppression and cough was not an outcome measure (details added to the Characteristics of excluded studies table, thus totalling to 20 excluded studies in this current update).

Included studies

Four studies were included, as described in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table; all were available in English. However, data specific for pneumonia were only available in two papers (Principi 1986; Roa 1995). Authors of three papers did not respond to our correspondence requesting for further pneumonia‐specific data.

Of the included studies, one study was exclusively in children (Principi 1986), two were exclusively in adults (Aquilina 2001; Azzopardi 1964) and one included adolescents and adults (Roa 1995).

One study utilised an antitussive (Dimyril) (Azzopardi 1964) and three of the studies examined the efficacy of different formulations of mucolytics (bromhexine (Roa 1995), neltenexine (Aquilina 2001) and ambroxol (Principi 1986)). In two of these studies, the concomitant antibiotics used were reported (Principi 1986; Roa 1995).

Two studies were multicentre studies (Principi 1986; Roa 1995), for which the funding was unspecified. Two studies were single‐centre studies (Aquilina 2001; Azzopardi 1964). One study was a controlled non‐placebo study (Roa 1995) and the rest utilised a randomised placebo‐controlled design (Aquilina 2001; Azzopardi 1964; Principi 1986). All but one study (Azzopardi 1964) used a parallel design.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria (that is, including the definition of pneumonia) varied between the studies; only one study was exclusively in patients with pneumonia (Principi 1986). In Roa 1995, bacterial pneumonia was defined as the presence of recent productive phlegm, fever or leucocytosis (> 10,000 mm3) and pulmonary infiltrates on radiographic examination. In Principi 1986, inclusion required either a positive blood culture for a well‐defined bacterium or a chest X‐ray showing lobar or sub lobar involvement together with raised inflammatory markers, erythrocyte sedimentation rate ≥ 30 mm/h and C‐reactive protein ≥ 25 μg/mL. The two smaller papers (Aquilina 2001; Azzopardi 1964) which contributed rather fewer numbers to the analysis did not clearly define pneumonia.

The outcomes of the studies also varied and none utilised a validated scale for cough. The larger trials were performed and published 12 and 21 years ago, respectively, and so were not methodologically as robust as one would expect of current‐day trials (Principi 1986; Roa 1995). The Roa 1995 trial evaluated clinical response, bacteriological response and each clinical symptom using a visual analogue scale. Both clinical and bacteriological responses had clearly defined definitions; they defined cure as complete disappearance of pretreatment signs and symptoms, and improvement as an improvement on the visual analogue scale but less than cure. Principi 1986 evaluated clinical and radiological signs and used absolute numbers and severity scores to evaluate clinical symptoms and signs, including cough. The Aquilina 2001 trial used severity scores on prespecified examination days and at the end of therapy; the investigator expressed an overall assessment of the therapeutic efficacy. The Azzopardi 1964 trial was more obviously subjective in its evaluation.

Excluded studies

As described above, we excluded 20 trials (details are provided in the Characteristics of excluded studies table), most on the basis of being non‐randomised, with no placebo.

Risk of bias in included studies

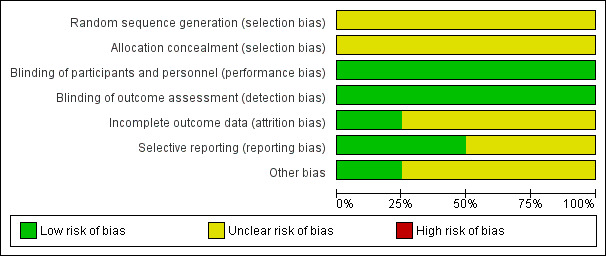

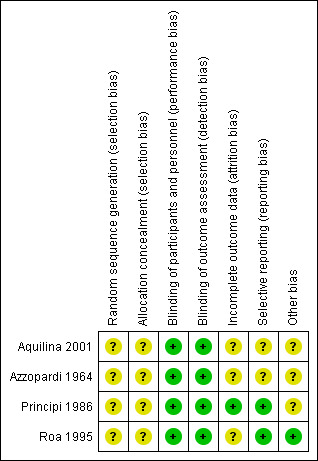

In previous reviews, the agreement between the review authors for the scores was good: the weighted Kappa score for the quality assessment scale was 0.63. In the updated 2011 version we completed a 'Risk of bias' table (Figure 1; Figure 2). Generally, there were no glaring biases in the included studies ‐ the majority of parameters were assessed as low‐risk or unclear risk. There were no high‐risk biases identified. Specifically the method used for sequence generation and whether allocation was concealed were not clear in all the studies. However the blinding of participants and outcomes seemed reasonable.

1.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

See 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Blinding

See 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Incomplete outcome data

See 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Selective reporting

There was limited reporting in the studies. See 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Other potential sources of bias

Unclear or low‐risk.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

In one study (Azzopardi 1964) the number of participants with pneumonia was not specified. In the other three included studies (Aquilina 2001; Principi 1986; Roa 1995) the total number of randomised participants was 555, of which 224 had pneumonia. The total number who completed the trials was 518, of which 219 had pneumonia. Given the lack of data, meta‐analysis could not be performed on any outcome when children and adults were considered separately and, thus, sensitivity analysis was irrelevant. Single study results and the data and analysis section are described below.

Paediatrics ‐ Primary outcomes

Mucolytics

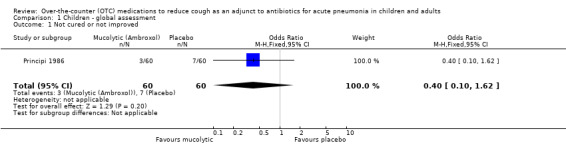

Principi reported that cough disappeared more rapidly in children treated with ambroxol than in the placebo group (Principi 1986). However, in the data and analysis section for the primary outcome of 'not cured or not improved' (defined on chest X‐ray), there was no significant difference between groups (odds ratio (OR) 0.40, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.10 to 1.62) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Children ‐ global assessment, Outcome 1 Not cured or not improved.

Paediatrics ‐ Secondary outcomes

1. Proportion of participants who were not cured at follow‐up

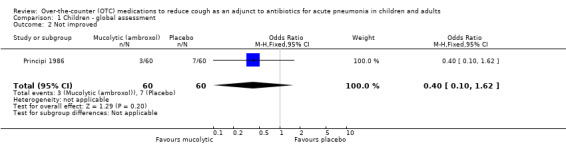

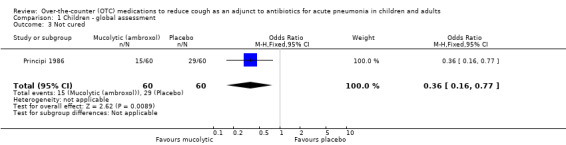

There was also no difference between groups for the secondary outcome of 'no improvement' (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.10 to 1.62) (Analysis 1.2). However, for the secondary outcome of clinically 'not cured' there was a significant difference between groups (defined on chest X‐ray), as presented in the data and analysis section, favouring the ambroxol group. The OR was 0.36 (95% CI 0.16 to 0.77) (Analysis 1.3) and the number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) was 5 (95% CI 3 to 16).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Children ‐ global assessment, Outcome 2 Not improved.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Children ‐ global assessment, Outcome 3 Not cured.

2. Change in quantitative differences in cough

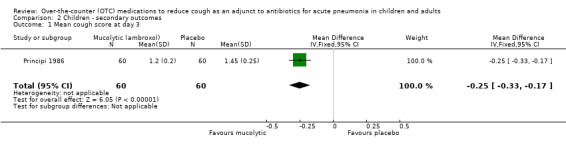

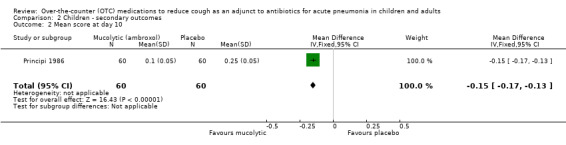

Principi reported a significant difference between groups, favouring the ambroxol group from day three onwards (Principi 1986). The data and analysis section for mean cough scores on days 3 and 10 is shown in Analysis 2.1 and Analysis 2.2. For day 3, the mean difference was ‐0.25 (95% CI ‐0.33 to ‐0.17). For day 10, the mean difference was ‐0.15 (95% CI ‐0.17 to ‐0.13).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Children ‐ secondary outcomes, Outcome 1 Mean cough score at day 3.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Children ‐ secondary outcomes, Outcome 2 Mean score at day 10.

3. Adverse effects

The trial authors reported no significant adverse events in either group (Principi 1986).

4. Other complications and reported data

Data for other secondary outcomes were not available. There were no studies on any other type of over‐the‐counter (OTC) medication for cough associated with pneumonia in children.

Adults ‐ Primary outcomes

Mucolytics

Two studies (Aquilina 2001; Roa 1995) used a mucolytic but only data from one study (Roa 1995) could be included in this review. In the study using neltenexine (a mucolytic), we could not obtain data specific for those with pneumonia (n = 3) (Aquilina 2001). The trial authors reported no significant adverse events in any of the groups (Aquilina 2001).

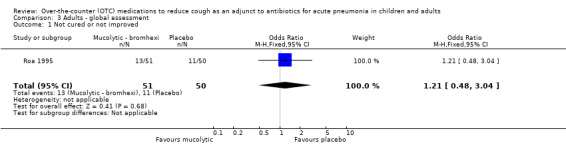

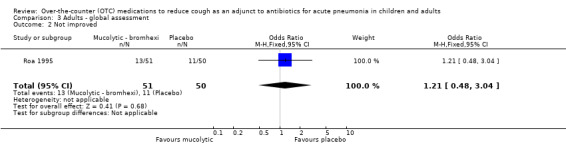

Data specifically described for pneumonia were available only for global 'clinical response' and this is presented in the data and analysis section (Analysis 3). For the primary outcome of clinically 'not cured or not improved' there was no significant difference between groups (OR 1.21, 95% CI 0.48 to 3.04) (Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adults ‐ global assessment, Outcome 1 Not cured or not improved.

Adults ‐ Secondary outcomes

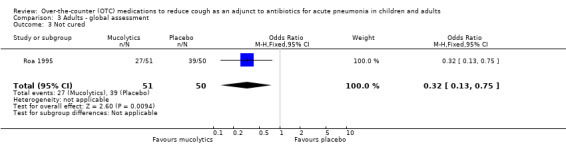

1. Proportion of participants who were not cured at follow‐up

There was also no significant difference between groups for the secondary outcome 'not improved' (OR 1.21, 95% CI 0.48 to 3.04) (Analysis 3.2). However, like the results for children treated with a mucolytic, there was a significant difference between groups for the secondary outcome 'not cured' (OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.75), NNTB 5 (95% CI 3 to 19), favouring those on bromhexine (Analysis 3.3).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adults ‐ global assessment, Outcome 2 Not improved.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adults ‐ global assessment, Outcome 3 Not cured.

2. Change in quantitative differences in cough

The Roa study reported that for the total group (that is, adults with pneumonia and bronchitis) the differences between cough frequency on days three, five and seven and baseline were significantly larger in the bromhexine group compared to the control group (Roa 1995). Data could not be extracted.

3. Adverse effects

The authors reported a total of 11 adverse events, six in the active treatment group and five in the control group (Roa 1995).

4. Other complications and reported data

There was also a difference between groups (favouring bromhexine) for cough discomfort and ease of expectoration on days three and five, but not on day seven, as well as sputum volume on day three, but not on days five or seven. There was no difference between the groups for difficulty in breathing or chest pain on any day. At final evaluation significantly more participants were 'cured' (46%) in the bromhexine group compared to the control group (34%) (Roa 1995). There were no studies on any other type of OTC medication for cough.

Antitussives

The Azzopardi study on 34 adults (total number assumed based on study design (see the Characteristics of included studies table) included adults with pneumonia (number unknown) in addition to other lower respiratory tract infection aetiologies (Azzopardi 1964). Data on those with pneumonia alone were not available and are not described here.

Combined data for children and adults ‐ Primary outcomes

Mucolytics

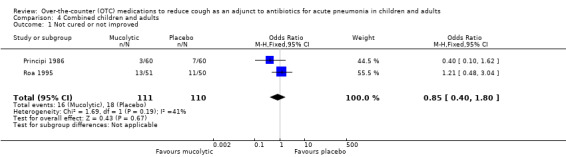

In a post hoc analysis, we combined data on children and adults. There was no significant statistical heterogeneity in any of the outcomes (Analysis 4.1 to Analysis 4.3).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Combined children and adults, Outcome 1 Not cured or not improved.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Combined children and adults, Outcome 3 Not cured.

In the combined data, meta‐analysis showed no significant difference between groups for the primary outcome of 'not cured or not improved' (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.80) (Analysis 4.1).

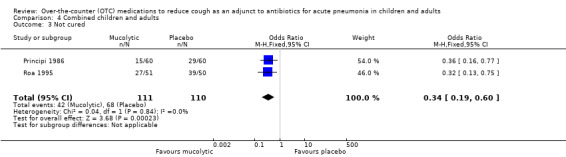

Combined data for children and adults ‐ Secondary outcomes

1. Proportion of participants who were not cured at follow‐up

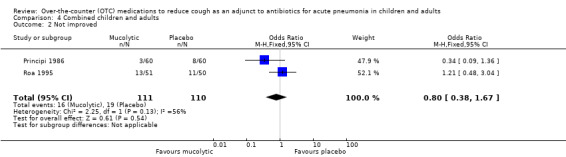

There was also no significant difference between groups for the secondary outcome 'not improved' (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.67) (Analysis 4.2). However, Analysis 4.3 showed a significant difference between groups for the outcome 'not cured' (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.60), NNTB 4 (95% CI 3 to 8), favouring those on a mucolytic.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Combined children and adults, Outcome 2 Not improved.

2. Change in quantitative differences in cough

No data could be combined for this outcome.

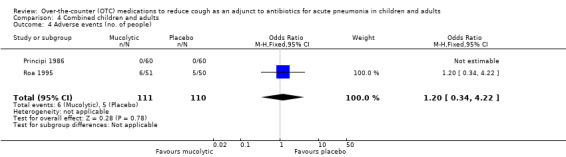

3. Adverse effects

There was no significant difference between the groups in the number of people who had an adverse event (OR 1.20, 95% CI 0.34 to 4.22) (Analysis 4.4).

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Combined children and adults, Outcome 4 Adverse events (no. of people).

4. Other complications and reported data

Data for other secondary outcomes could not be combined.

Sensitivity analyses

The only appropriate sensitivity analysis that could be performed was that for Analysis 4 (combined children and adults). Statistical heterogeneity was absent but given the clinical heterogeneity we used a random‐effects model to re‐examine the results. This revealed that there was still no significant difference between groups for Analysis 4.1 ('not cured or not improved') but the OR was altered, with a wider confidence interval (OR 0.79, 95% CI to 0.27 to 2.29). For Analysis 4.2 ('not improved'), the non‐significant difference was also unaltered but the OR changed to 0.72 (95% CI 0.21 to 2.29). For Analysis 4.3 ('not cured'), the significant difference between groups was also preserved and there was no difference in the OR or 95% CI (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.60), NNTB 4 (95% CI 3 to 8), favouring those on a mucolytic.

Discussion

Only a few studies have examined over‐the‐counter (OTC) medications for cough related to pneumonia.

Summary of main results

Although four studies were included in this review, only data from two studies could be used (Principi 1986; Roa 1995). Both of these studies examined the efficacy of a mucolytic as an adjunct in the management of pneumonia and used cough as the principal outcome. For the primary outcome of 'not cured or not improved', there was no difference between groups when we considered children and adults separately, or when we combined data in a post hoc analysis. However, for one of the secondary outcomes ('not cured') the use of a mucolytic increased the cure rate similarly in both children and adults (number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) = 5). Therefore, we cannot be confident of its efficacy. Nevertheless, based on Analysis 2.1, if a mucolytic is tried then the time to response (that is, the "expected timeframe to which a significant improvement is seen" (Chang 2006)), is three days. However, these data come from only a single study.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

OTC medications for cough consist of a variety of drugs used as sole agents or in combination. These drugs include antitussives (such as codeine derivatives), antihistamines and non‐pharmaceutical medications (for example, menthol) (Eccles 2002). However, it is also possible that non‐pharmaceutical additives used (such as sugar, alcohol) may have a therapeutic effect, such that the placebo effect of medications for cough has been reported to be as high as 85% (Eccles 2002). Thus, it is not surprising that although the total sample size for the combined studies was not small (N = 224), there was no effect seen for the primary outcome. Given that there was a significant difference between groups, further evaluation of mucolytics using more robust outcomes (as outlined in the 'Implications for research') is certainly warranted.

Although adverse events were uncommon in the clinical trials identified in this study, there are case reports of severe adverse events, including severe morbidity and even death (Kelly 2004).

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence is low, as shown in the 'Table 1'.

Potential biases in the review process

This systematic review is limited to four studies (with only two with extractable data) and in these studies only a single type of OTC medication for cough was examined. Thus, there is a clear lack of studies in this area. Also, the inclusion criteria and outcomes varied among trials.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A systematic review on adjunctive therapies for community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) reported "We found no clinical trials assessing the effectiveness of over‐the‐counter preparations for cough as an adjunct to antimicrobial treatment in patients with CAP" (Siempos 2008).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

With the lack of evidence, the routine use of over‐the‐counter (OTC) cough medications in treating children or adults with troublesome cough associated with pneumonia cannot be recommended. Of those tested, mucolytics are the only type of OTC medication that have been shown to be possibly efficacious. The 'time to response' (subjective cough severity) is three days when used as an adjunct to an appropriate antibiotic. In current practice it is recommended that young children are not given OTC cough medications containing codeine derivatives and antihistamines because of the known adverse events of these medications.

Implications for research.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of OTC medications to determine their effectiveness in treating cough associated with pneumonia are clearly needed. Current guidelines advocate that studies of antitussives should take place in patients with a clearly defined clinical entity, such as pneumonia. Trials should be parallel studies and double‐blinded, given the known problems in studying cough, specifically the large placebo and time period effects. Clinical, radiological and bacteriological responses should be objectively evaluated. Based on the above data, a short trial of seven days would suffice. Outcome measures for the clinical studies on cough should be clearly defined using validated subjective data and supported by objective data, if possible.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 22 January 2014 | New search has been performed | Searches updated. No new trials were identified for inclusion. We excluded one new trial (Basnet 2012) in this update. |

| 22 January 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Our conclusions remain unchanged. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2006 Review first published: Issue 4, 2007

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 8 August 2011 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Our conclusions remain unchanged. |

| 10 July 2009 | New search has been performed | Searches conducted. No new included studies found. Two new studies excluded. |

| 21 February 2008 | Amended | 'Summary of findings' table added. |

| 30 January 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

We thank Liz Dooley, Managing Editor, and the Cochrane Acute Respiratory Infections (ARI) Group for their advice and support in preparing the protocol and review. We thank Sarah Thorning for the 2011 searches. We also thank Concetto Tartaglia, Thomas Kraemer, Helen Petsky and Margaret McElrea for translation of non‐English articles. Finally, we wish to thank the following people for commenting on the draft review: Chanpen Choprapawon, John Widdicombe, Brandon Carr, Nelcy Rodriguez and Abigail Fraser.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Previous search strategy

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2009, Issue 2) which contains the Acute Respiratory Infections Group's Specialised Register; MEDLINE (January 1966 to July Week 1, 2009); OLDMEDLINE (1950 to 1965); EMBASE (1980 to July 2009).

The following search strategy was run in MEDLINE and CENTRAL and adapted for EMBASE.

MEDLINE (OVID) 1 exp Cough/ 2 cough.mp. 3 or/1‐2 4 exp Pneumonia/ 5 pneumonia.mp. 6 or/4‐5 7 exp Antitussive Agents/ 8 antitussive agent$.mp. 9 exp Expectorants/ 10 expectorant$.mp. 11 exp Cholinergic Antagonists/ 12 cholinergic antagonist$.mp. 13 exp Histamine H1 Antagonists/ 14 histamine H1 antagonist$.mp. 15 mucolytic$.mp. 16 exp Drug Combinations/ 17 drug combination$.mp. 18 exp Drugs, Non‐Prescription/ 19 non prescription drug$.mp. 20 (over‐the‐counter or over the counter or OTC).mp. 21 or/7‐20 22 3 and 6 and 21

EMBASE.com search strategy

1. 'coughing'/exp 2. cough*:ti,ab 3. #1 OR #2 4. 'pneumonia'/exp 5. pneumon*:ti,ab 6. #4 OR #5 7. 'antitussive agent'/exp 8. antitussiv*:ti,ab 9. 'expectorant agent'/exp 10. expectorant*:ti,ab 11. 'cholinergic receptor blocking agent'/exp 12. 'cholinergic antagonist':ti,ab OR 'cholinergic antagonists':ti,ab 13. 'histamine h1 receptor antagonist'/exp 14. 'histamine h1 antagonist':ti,ab OR 'histamine h1 antagonists':ti,ab 15. 'mucolytic agent'/exp 16. mucolytic*:ti,ab 17. 'drug combination'/exp 18. 'drug combination':ti,ab OR 'drug combinations':ti,ab 19. 'non prescription drug'/exp 20. 'non prescription drug':ti,ab OR 'non prescription drugs':ti,ab OR 'non‐prescription drug':ti,ab OR 'non‐prescription drugs':ti,ab 21. 'over the counter':ti,ab OR 'over‐the‐counter':ti,ab OR otc:ti,ab 22. #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 23. #3 AND #6 AND #22

There were no language or publication restrictions.

Appendix 2. Embase.com search strategy

#31. #27 AND #30 #30. #28 OR #29 #29. random*:ab,ti OR placebo*:ab,ti OR factorial*:ab,ti OR crossover*:ab,ti OR 'cross‐over':ab,ti OR 'cross over':ab,ti OR volunteer*:ab,ti OR assign*:ab,ti OR allocat*:ab,ti OR ((singl* OR doubl*) NEAR/1 blind*):ab,ti #28. 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'crossover procedure'/exp #27. #7 AND #26 #26. #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 #25. (cough* NEAR/3 (suppress* OR mixture* OR syrup* OR medicine* OR remed* OR relief* OR formula*)):ab,ti #24. 'over‐the‐counter':ab,ti OR 'over the counter':ab,ti OR otc:ab,ti #23. (('non presciption' OR 'non prescribed') NEAR/3 (drugs* OR medicine* OR medicat* OR pharmaceut*)):ab,ti #22. ((nonprescribed OR nonprescription) NEAR/3 (drug* OR medicine* OR pharmaceut* OR medicat*)):ab,ti #21. 'non prescription drug'/de #20. (drug* NEAR/2 combination*):ab,ti #19. 'drug combination'/exp #18. mucolytic*:ab,ti #17. 'mucolytic agent'/exp #16. antihistamin*:ab,ti OR 'anti‐histamine':ab,ti OR 'anti‐histamines':ab,ti OR 'histamine h1antagonist':ab,ti OR 'histamine h1antagonists':ab,ti #15. 'histamine h1 receptor antagonist'/exp #14. anticholinergic*:ab,ti OR 'anti‐cholinergic':ab,ti OR 'anti‐cholinergics':ab,ti #13. (cholinergic NEAR/2 (blocking OR antagonist*)):ab,ti #12. 'cholinergic receptor blocking agent'/exp #11. expectorant*:ab,ti #10. 'expectorant agent'/exp #9. antitussiv*:ab,ti #8. 'antitussive agent'/de #7. #3 AND #6 #6. #4 OR #5 #5. pneumon*:ab,ti OR bronchopneumon*:ab,ti #4. 'pneumonia'/exp #3. #1 OR #2 #2. cough*:ab,ti #1. 'coughing'/de OR 'irritative coughing'/de

Appendix 3. CINAHL (Ebsco) search strategy

S27 S7 AND S26 S26 S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 OR S20 OR S21 OR S22 OR S23 OR S24 OR S25 S25 TI (cough* W1 (mixtur* or medicin* or suppress* or relief* or remed* or formul* or syrup*)) OR AB (cough* W1 (mixtur* or medicin* or suppress* or relief* or remed* or formul* or syrup*)) S24 TI (over the counter or over‐the‐counter or otc) OR AB (over the counter or over‐the‐counter or otc) S23 TI (nonprescribed drug* or non‐prescribed drug* or nonprescribed medicin* or non‐prescribed medicin* or nonprescribed pharmaceut* or non‐prescribed pharmaceut* or nonprescribed medicat* or non‐prescribed medicat*) OR AB (nonprescribed drug* or non‐prescribed drug* or nonprescribed medicin* or non‐prescribed medicin* or nonprescribed pharmaceut* or non‐prescribed pharmaceut* or nonprescribed medicat* or non‐prescribed medicat*) S22 TI (nonprescription drug* or non‐prescription drug* or nonprescription medicin* or non‐prescription medicin* or nonprescription pharmaceut* or non‐prescription pharmaceut* or nonprescription medicat* or non‐prescription medicat*) OR AB (nonprescription drug* or non‐prescription drug* or nonprescription medicin* or non‐prescription medicin* or nonprescription pharmaceut* or non‐prescription pharmaceut* or nonprescription medicat* or non‐prescription medicat*) S21 (MH "Drugs, Non‐Prescription") S20 TI drug* N2 combination* OR AB drug* N2 combination* S19 (MH "Drug Combinations+") S18 TI mucolytic* OR AB mucolytic* S17 TI histamin* h1 antagonist* OR AB histamin* h1 antagonist* 37 S16 TI (antihistamin* or anti‐histamin*) OR AB (antihistamin* or anti‐histamin*) S15 (MH "Histamine H1 Antagonists+") S14 TI (anticholinergic* or anti‐cholinergic*) OR AB (anticholinergic* or anti‐cholinergic*) S13 TI (cholinergic N2 (antagonist* or blocking)) OR AB (cholinergic N2 (antagonist* or blocking)) S12 (MH "Cholinergic Antagonists+") S11 TI expectorant* OR AB expectorant* S10 (MH "Expectorants+") S9 TI antitussiv* OR AB antitussiv* S8 (MH "Antitussive Agents+") S7 S3 AND S6 S6 S4 OR S5 S5 TI (pneumon* or bronchopneumon*) OR AB (pneumon* or bronchopneumon*) S4 (MH "Pneumonia+") S3 S1 OR S2 S2 TI cough* OR AB cough* S1 (MH "Cough")

Appendix 4. LILACS (BRIEME) search strategy

((mh:"Antitussive Agents" OR antitusígenos OR antitussígenos OR antitusivos OR "Agentes Béquicos" OR "Substâncias Béquicas" OR "Medicamentos Béquicos" OR antituss* OR mh:expectorants OR expectorantes OR mucolytic* OR mucolíticos OR expectorante OR expectorant* OR mh:"Cholinergic Antagonists" OR "Acetylcholine Antagonists" OR "Anticholinergic Agents" OR "Cholinergic‐Blocking Agents" OR cholinolytics OR "Antagonistas Colinérgicos" OR "Antagonistas de la Acetilcolina" OR "Agentes Anticolinérgicos" OR "Agentes Bloqueadores Colinérgicos" OR colinolíticos OR mh:d27.505.519.625.120.200* OR mh:d27.505.696.577.120.200* OR anticholinergic* OR "anti‐cholinergic" OR "anti‐cholinergics" OR mh:"Histamine H1 Antagonists" OR "Histamine H1 Receptor Antagonists" OR "Histamine H1 Receptor Blockaders" OR mh:d27.505.519.625.375.425.400* OR mh:d27.505.696.577.375.425.400* OR "Antagonistas de los Receptores Histamínicos H1" OR "Antihistamínicos Clásicos" OR "Antihistamínicos H1" OR "Antagonistas del Receptor H1 de Histamina" OR "Bloqueadores de los Receptores Histamínicos H1" OR "Bloqueadores de los Receptores H1 de Histamina" OR "Antagonistas dos Receptores Histamínicos H1" OR "Anti‐Histamínicos H1" OR "Antagonistas dos Receptores H1 de Histamina" OR "Bloqueadores dos Receptores Histamínicos H1" OR "Bloqueadores dos Receptores H1 de Histamina" OR mh:d26.530* OR mh:"Nonprescription Drugs" OR "Over‐the‐Counter" OR otc OR "over the counter" OR "Medicamentos sin Prescripción" OR "Medicamentos de Venta Libre" OR "Medicamentos de Libre Circulación" OR "Medicamentos sem Prescrição" OR "Medicamentos não Prescritos" OR "Medicamentos de Venda Livre" OR "Medicamentos de Livre Circulação" OR "Medicamentos Isentos de Prescrição" OR mips OR "Drug Combinations" OR mh:d26.310.500* OR "Multi‐Ingredient Cold Medications" OR "Medicamentos Compuestos" OR "Medicamentos Compostos") AND (mh:cough OR cough* OR tos*) AND (mh:pneumonia OR mh:c08.381.677* OR mh:c08.730.610* OR pneumon* OR bronchopneumon* OR neumonía OR "Inflamación Experimental del Pulmón" OR "Inflamación del Pulmón" OR "Neumonía Lobar" OR neumonitis OR "Inflamación Pulmonar" OR pulmonía OR "Inflamação Experimental dos Pulmões" OR "Inflamação do Pulmão" OR "Pneumonia Lobar" OR pneumonite OR "Inflamação Pulmonar")) AND db:("LILACS")

Appendix 5. Web of Science (Thomson ISI) search strategy

| # 6 | 44 | #5 AND #1 Databases=SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI‐S, CPCI‐SSH, CCR‐EXPANDED, IC Timespan=All years |

| # 5 | 28,361 | #4 OR #3 OR #2 Databases=SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI‐S, CPCI‐SSH, CCR‐EXPANDED, IC Timespan=All years |

| # 4 | 890 | Topic=(cough* NEAR/3 (mixtur* or medicin* or suppress* or relief* or remed* or formul* or syrup*)) Databases=SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI‐S, CPCI‐SSH, CCR‐EXPANDED, IC Timespan=All years |

| # 3 | 924 | Topic=((nonprescription* or nonprescribed* or "non prescribed" or "non prescription" or non‐prescribed or non‐prescription) NEAR/3 (drug* or medicin* or pharmaceut* or medicat*)) Databases=SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI‐S, CPCI‐SSH, CCR‐EXPANDED, IC Timespan=All years |

| # 2 | 27,059 | Topic=(antitussiv* or expectorant* or (cholinergic NEAR/2 (blocking or antagonist*)) or anticholinergic* or anti‐cholinergic* or "histamin* h1 antagonist*" or antihistamin* or anti‐histamin* or mucolytic* or over‐the‐counter or otc or "over the counter") Databases=SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI‐S, CPCI‐SSH, CCR‐EXPANDED, IC Timespan=All years |

| # 1 | 2,727 | Topic=(cough*) AND Topic=(pneumon* OR bronchopneumon*) Databases=SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI‐S, CPCI‐SSH, CCR‐EXPANDED, IC Timespan=All years |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Children ‐ global assessment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Not cured or not improved | 1 | 120 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.10, 1.62] |

| 2 Not improved | 1 | 120 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.10, 1.62] |

| 3 Not cured | 1 | 120 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.16, 0.77] |

Comparison 2. Children ‐ secondary outcomes.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mean cough score at day 3 | 1 | 120 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.25 [‐0.33, ‐0.17] |

| 2 Mean score at day 10 | 1 | 120 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.15 [‐0.17, ‐0.13] |

| 3 Adverse events (no. of people) | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only |

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Children ‐ secondary outcomes, Outcome 3 Adverse events (no. of people).

Comparison 3. Adults ‐ global assessment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Not cured or not improved | 1 | 101 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.21 [0.48, 3.04] |

| 2 Not improved | 1 | 101 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.21 [0.48, 3.04] |

| 3 Not cured | 1 | 101 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.13, 0.75] |

Comparison 4. Combined children and adults.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Not cured or not improved | 2 | 221 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.40, 1.80] |

| 2 Not improved | 2 | 221 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.38, 1.67] |

| 3 Not cured | 2 | 221 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.19, 0.60] |

| 4 Adverse events (no. of people) | 2 | 221 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.2 [0.34, 4.22] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Aquilina 2001.

| Methods | Single‐centre, double‐blind, parallel, placebo‐controlled RCT. Method of recruitment was not specified

Concomitant antitussives, mucolytics and beta‐2 agonist disallowed. Clinical evaluation performed on baseline, days 3, 7 and final. Participants assessed for signs and symptoms relevant to diagnosis of acute or chronic lung disease including sputum volume and characteristics, dyspnoea, cough, pulmonary auscultation, difficulty in expectorating Compliance not mentioned. Inclusion and exclusion criteria described in next column Description of withdrawals or drop‐outs not mentioned |

|

| Participants | 14 participants allocated to neltenexine, 14 to placebo. 3 within group had pneumonia but data specific to pneumonia were unavailable Mean age of total group was 57.5 years (SD 3.04) Inclusion criteria: adults (aged > 18 years) with acute and chronic lung disease Exclusion criteria: pulmonary tuberculosis, lung cancer, allergy to neltenexine, severe bronchospasm (requiring beta‐2 agonist, corticosteroids or aminophylline), or pregnant or lactating women | |

| Interventions | Neltenexine (a mucolytic), 37.4 mg tds or placebo (1 tablet tds) for 10 to 12 days | |

| Outcomes | Overall physicians' assessment of efficacy scored: excellent, good, moderate, not satisfactory. Exact quantification unspecified Sputum volume, sputum characteristics (1 = serous to 5 = very purulent), and 5‐point scores for dyspnoea, cough, pulmonary auscultation, difficulty in expectorating, from 0 (absent) to 4 very severe | |

| Notes | Wrote to authors with no response Data for pneumonia alone not available | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Placebo used |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Placebo used |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Drop‐outs unclear |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Data for pneumonia alone could not be extracted |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Data for pneumonia alone could not be extracted. Single‐centre study; further information sought from trial authors with no response |

Azzopardi 1964.

| Methods | Single‐centre, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled RCT. Participants recruited from inpatients in the geriatric unit of Barnet General Hospital, England. The method of randomisation and allocation was not described. When the medication (active or placebo) was considered ineffective, the pharmacist was asked to change to alternate treatment. Data card and observation record prepared for each participant, other medications recorded and authors indicated that these factors were taken into account when assessing response to trial drugs (but did not specify how). Inclusion and exclusion criteria not described. Description of withdrawals or drop‐outs not mentioned | |

| Participants | Total randomised unknown. Total described in group unclear as some participants could have been counted twice given potential cross‐over methodology. If assumed cross‐over was undertaken for all, total randomised would be 34

Age of participants not given

Participants had variety of aetiological factors for cough (pneumonia, acute and chronic bronchitis, bronchiectasis, carcinoma, cardiac failure, cor pulmonale, nervous cough, coryza, influenza) Inclusion and exclusion criteria not described |

|

| Interventions | Dimyril (active ingredient = isoaminile citrate, a codeine derivative) or placebo in identical bottles. Dose used varied. Initially 3 to 4 times/day followed by 'as necessary' dosing of up to 5 times a day (1 to 2 G) | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes not clearly specified Paper stated: "The evidence of the patient, the several observers (day and night nurses, physician, and medico‐social worker), the number of doses per 24 hours, and (when recorded) the actual cough frequencies were considered in deciding whether or not the nuisance and frequency of cough had been reduced" |

|

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not specified |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not specified |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Placebo used and pharmacists not connected to trial involved |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Placebo used and pharmacists not connected to trial involved |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Outcome of drop‐outs and withdrawals unclear |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Outcomes not clearly specified |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Insufficient data to be certain |

Principi 1986.

| Methods | Multi‐centre, double‐blind, parallel, placebo‐controlled RCT. Children recruited from 3 hospitals in Italy Potential participants admitted into hospital for symptoms of pneumonia screened for inclusion criteria (next row) Double‐blinded study and all participants were treated as inpatients and re‐evaluated daily for heart rate, respiratory rate and maximal rectal body temperature. Cough, dyspnoea and chest pathological scores also recorded daily. Chest X‐ray on admission and end of treatment. Compliance not mentioned but presumed excellent given inpatient study All children given antibiotics (see column on intervention). Other co‐treatment (e.g. anti‐pyretic agents) not mentioned Inclusion and exclusion criteria described in next column Description of withdrawals or drop‐outs not mentioned. As children were inpatients, assumed most followed up. Chest X‐ray follow‐up rate 115/120 = 95.8% |

|

| Participants | Total of 120 children randomised ‐ 60 in each arm. Outcome measure available for 115 children (57 active arm, 58 controls), 95.8% Antibiotic with ambroxol group: mean age not given, 11 aged < 1 year, 9 aged 1 to 2 years, 19 aged 2 to 5 years, 21 aged 5 to 12 years Gender: M 28; F 32 Mean body weight: 17.1 kg (SD 1.08) Antibiotic with placebo: mean age not given, 12 children aged < 1 year, 11 aged 1 to 2 years, 20 aged 2 to 5 years, 17 aged 5 to 12 years Gender: M 38; F 22 Mean body weight 16.2 kg (SD 1.06) Inclusion criteria: children admitted into hospital for pneumonia. Have had blood culture performed before commencement of antibiotics and positive for well‐defined bacterium or a chest X‐ray showing lobar and sub lobar involvement, with erythrocyte sedimentation rate ≥ 30 mm/h and C‐reactive protein ≥ 25 μg/mL Exclusion criteria: taken antibiotics, mucolytics or mucoregulatory drugs in the preceding week |

|

| Interventions | Trial medications consisted of ambroxol (1.5 to 2 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses) or placebo for 10 days. All children also given antibiotics, chosen on basis of microbiological data or in accordance with literature on most probable aetiology for each age, for 7 to 10 days. Children aged < 5 years given oral amoxicillin or intramuscular ampicillin (50 mg/kg in 3 to 4 divided doses). Older children had oral erythromycin ethylsuccinate (50 mg/kg/day in 4 doses) | |

| Outcomes | Cough, dyspnoea and chest pathological signs scored, ranging from 0 (absent) to 3 (very severe). Chest X‐ray findings at the end of treatment were compared to pre‐treatment chest X‐ray and expressed as normalised, improved or unchanged | |

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not specified |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not mentioned |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Placebo used |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Placebo used |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Drop‐outs and withdrawals described |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Follow‐up of > 90% of participants |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Insufficient data to be certain |

Roa 1995.

| Methods | Multi‐centre, double‐blind, parallel RCT comparing amoxicillin plus bromhexine versus amoxycillin alone. Participants recruited from 22 centres involving internalists or pulmonologists in the Philippines Potential participants evaluated for inclusion criteria by history, examination, CXR, laboratory tests (blood counts, sputum). The method of randomisation and allocation was not described. Double‐blinded study and all participants were treated as outpatients and re‐evaluated on days 3, 5, 7 and 10. Compliance monitored by pill counting Participants allowed to receive medications for fever and constitutional symptoms but not any other cough expectorants or antimicrobials. Inclusion and exclusion criteria described in next column Description of withdrawals or drop‐outs mentioned for entire group. Maximum follow‐up rate 375/407 = 92% but less for other aspects |

|

| Participants | Total of 407 participants randomised ‐ 201 in active treatment and 206 in control group. 392 completed study (192 active, 200 controls). Compliance of 80% in active group and 85% in control group Amoxicillin with bromhexine group: mean age 32 (SD 13) years, gender ‐ 117 M: 75 F; 51 with pneumonia, 141 with bronchitis Amoxicillin alone: mean age 32 (SD 12), gender ‐ 130 M: 70 F; 50 with pneumonia, 150 with bronchitis Inclusion criteria: adolescents and adults aged 15 to 60 years with uncomplicated community‐acquired lower respiratory tract infection (pneumonia or bronchitis), clinically assessed to be bacterial in aetiology. Pneumonia defined as presence of cough < 2 weeks, purulent phlegm, fever and/or leucocytosis (> 10,000 mm3) and pulmonary infiltrates on CXR. Acute bronchitis defined as presence of cough < 2 weeks, purulent phlegm, fever and/or leucocytosis (> 10,000 mm3). Sputum culture had to be sensitive to amoxicillin or if organism resistant, participant included if clinical response at Day 3 occurred on amoxicillin. Exclusion criteria: frank respiratory failure, coexistent chronic disease (diabetes, renal failure, liver or renal impairment, terminal illness such as cancer, active tuberculosis, healed tuberculosis with bronchiectasis, chronic bronchitis or emphysema, heavy smokers (undefined)), pregnant or lactating, hypersensitivity to study drugs, or recent (< 2 weeks) treatment with antibiotics |

|

| Interventions | Active Rx = amoxicillin 240 mg and bromhexine 8 mg, both 4 times/day for 7 days Control group: amoxicillin alone, 250 mg 4 times/day for 7 days |

|

| Outcomes | Days 3, 5, 7 and 10. Participants evaluated for clinical response, bacteriological response, subjective symptom scores, adverse events, compliance, complete blood count Clinical response: Cured = complete disappearance of pre‐treatment symptoms and signs Improvement = pre‐treatment symptoms and signs improved but not cured Failure = pre‐treatment symptoms and signs did not improve or worsened Indeterminate = clinical response could not be determined Clinical symptoms: 10 mm visual analogue scale of symptoms of cough frequency, cough discomfort, difficulty breathing not related to cough, chest pain not related to cough, ease of expectoration Bacteriologic response: Eradication = absence of pre‐treatment pathogen or no more culturable material could be expectorated Persistence = presence of pre‐treatment pathogen Super‐infection = appearance of resistant pathogen after starting treatment Indeterminate = bacteriologic response could not be reliably assessed |

|

| Notes | Wrote to authors with no response Data for pneumonia alone available only for global clinical response outcome | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Data not provided |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not mentioned |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Placebo used |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Placebo used |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Follow‐up in > 90% for some outcomes but less in others |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Outcomes of withdrawals and drop‐outs mentioned |

| Other bias | Low risk | Insufficient data to be certain but multi‐centre study from 22 centres, thus likely low |

CXR: chest X‐ray F: female M: male RCT: randomised controlled trial SD: standard deviation tds: three times a day

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Aliprandi 2004 | Non‐placebo trial. Study involves comparing levodropropizine, codeine and cloperastine to levocloperastine |

| Balli 2007 | Erdosteine is not legally available as an over‐the‐counter medication in countries such as Australia, the UK and USA. Study compared amoxicillin plus erdosteine to amoxicillin‐placebo in children with acute lower respiratory tract infections |

| Barberi 1993 | Non‐placebo study comparing nimesulide to lysine‐aspirin in children |

| Bartolucci 1981 | Non‐controlled study in 40 adults using anti‐phlogistic‐balsamic compound (in Italian) |

| Basnet 2012 | RCT on zinc as adjunct treatment. No data specific to cough as an outcome measure |

| Caporalini 2001 | Non‐placebo study comparing neltenexine against N‐acetylcysteine |

| Dotti 1970 | Randomised controlled study but participants did not have pneumonia (in Italian) |

| Finiguerra 1981 | A double‐blind study in adults with acute and chronic bronchitis (not pneumonia) |

| Forssell 1966 | Non‐placebo study comparing drops to syrup formulation of an antitussive in infants and young children (in German) |

| Hargrave 1975 | Study examined role of bromhexine in prevention of postoperative pneumonia |

| Ida 1997 | A review article describing 3 studies on dimemorfan, a dextromethorphan analogue. Of the 3 cited studies, one was a placebo‐controlled trial. Insufficient details were included in the text and further data were not available from the author, who could not be contacted |

| Jayaram 2000 | Non‐placebo study comparing 2 cough formulations |

| Mancini 1996 | The paper summarises 3 studies which were not referenced. The first of the 3 studies described a RCT in children with "acute lower respiratory affections (e.g. acute bronchitis, bronchoalveolitis)". Unknown if children with pneumonia included and results stated reduction in cough scores with no specific data given. We wrote to authors and no response was received The other 2 studies described were in adults with '"superinfected chronic bronchitis" and "hypersecretory chronic obstructive bronchopneumopathies" |

| Pelucco 1981 | Non‐randomised, non‐placebo study in 26 adults (in Italian) |

| Titti 2000 | Erdosteine is not legally available as an over‐the‐counter medication in countries such as Australia, the UK and USA. Multi‐centre RCT compared ampicillin plus erdosteine to ampicillin‐placebo in children with acute lower respiratory tract infections |

| Turrisi 1984 | Non‐randomised, non‐placebo study using fenspiride in 20 adults (in Italian) |

| Wang 2005 | Study used Fuxiong plaster (i.e. not an OTC medication). Randomised controlled study in children with pneumonia |

| Wieser 1973 | Placebo but non‐randomised study comparing placebo to prenodiazine in 84 adults (in German) |

| Zhang 2005 | Study used Toubiao Qingfei (an externally applied therapy, i.e. not an OTC medication). Randomised controlled study in children with fever from pneumonia |

| Zurcher 1966 | Non‐placebo, double‐blind study comparing Sinecod‐Hommel to a codeine‐based antitussive in 95 adults (in German) |

OTC: over‐the‐counter RCT: randomised controlled trial

Contributions of authors

The protocol was written by Christina C Chang (CCC), Anne B Chang (ABC) and Allen C Cheng (ACC) based on previous protocols on cough in children. For the review: CCC and ABC selected articles from the search, performed the data extraction and data analysis, and wrote the review. ACC was the adjudicator if disagreement occurred and contributed to writing the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

-

NHMRC, Australia.

Practitioner fellowship (ABC) grant numbers 545216 and 1058213.

Centre for Research Excellence in Lung Health (grant 1040830).

-

Queensland Health Smart State Funds, Australia.

Salary support for ABC

-

Queensland Children's Medical Research Institute, Australia.

Program Grant

Declarations of interest

ABC: none known. CCC: none known. ACC: none known.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Aquilina 2001 {published data only}

- Aquilina R, Bergero F, Noceti P, Michelis C. Double blind study with neltenexine vs placebo in patients affected by acute and chronic lung diseases. Minerva Pneumologica 2001;40(2):77‐82. [EMBASE 2001363447] [Google Scholar]

Azzopardi 1964 {published data only}

- Azzopardi JF, Vanscolina AB. Clinical trial of a new anti‐tussive ('Dimryl'). British Journal of Clinical Practice 1964;18:213‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Principi 1986 {published data only}

- Principi N, Zavattini G, Daniotti S. Possibility of interaction among antibiotics and mucolytics in children. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology Research 1986;6:369‐72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Roa 1995 {published data only}

- Roa CC Jr, Dantes RB. Clinical effectiveness of a combination of bromhexine and amoxicillin in lower respiratory tract infection. A randomized controlled trial. Progress in Drug Research. Fortschritte der Arzneimittelforschung 1995;45(3):267‐72. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Aliprandi 2004 {published data only}

- Aliprandi P, Castelli C, Bernorio S, Dell'Abate E, Carrara M. Levocloperastine in the treatment of chronic nonproductive cough: comparative efficacy versus standard antitussive agents. Drugs under Experimental and Clinical Research 2004;30:133‐41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Balli 2007 {published data only}

- Balli F, Bergamini B, Calistru P, Ciofu EP, Domenici R, Doros G, et al. Clinical effects of erdosteine in the treatment of acute respiratory tract diseases in children. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2007;45:16‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Barberi 1993 {published data only}

- Barberi I, Macchia A, Spata N, Scaricabarozzi I, Nava ML. Double‐blind evaluation of nimesulide vs lysine‐aspirin in the treatment of paediatric acute respiratory tract infections. Drugs 1993;46(Suppl 1):219‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bartolucci 1981 {published data only}

- Bartolucci L, Canini F, Fioroni E, Pinchi G, Carosi M. Clinical evaluation of the therapeutic effectiveness of a new drug with anti‐inflammatory‐balsamic action, guacetisal, in respiratory tract diseases. Minerva Medica 1981;72(7):325‐32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Basnet 2012 {published data only}

- Basnet S, Shrestha PS, Sharma A, Mathisen M, Prasai R, Bhandari N, et al. Zinc Severe Pneumonia Study Group. A randomized controlled trial of zinc as adjuvant therapy for severe pneumonia in young children. Pediatrics 2012;129:701‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Caporalini 2001 {published data only}

- Caporalini R, Giosue GL. Neltenexine in lung diseases: an open, randomised, controlled study versus N‐acetylcysteine comparison. Minerva Pneumologica 2001;40:57‐62. [Google Scholar]

Dotti 1970 {published data only}

- Dotti A. Clinical trial of the antitussive action of an association of codeine plus phenyltoloxamine. Giornale Italiano Delle Malattie del Torace 1970;24(3):147‐57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Finiguerra 1981 {published data only}

- Finiguerra M, Martini S, Negri L, Simonelli A. Clinical and functional effects of domiodol and sobrerol in hypersecretory bronchopneumonias. Minerva Medica 1981;72(21):1353‐60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Forssell 1966 {published data only}

- Forssell P, Salmi I. On objective registration of the effects of cough medication [Zur objektiven Registrierung des Effektes von Hustenmitteln]. Archiv für Kinderheilkunde 1966;175:33‐41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hargrave 1975 {published data only}

- Hargrave SA, Palmer KN, Makin EJ. Effect of bromhexine on the incidence of postoperative bronchopneumonia after upper abdominal surgery. British Journal of Diseases of the Chest 1975;69:195‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ida 1997 {published data only}

- Ida H. The nonnarcotic antitussive drug dimemorfan: a review. Clinical Therapeutics 1997;19(2):215‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jayaram 2000 {published data only}

- Jayaram S, Desai A. Efficacy and safety of ascoril expectorant and other cough formula in the treatment of cough management in paediatric and adult patients ‐ a randomised double‐blind comparative trial. Journal of the Indian Medical Association 2000;98(2):68‐70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mancini 1996 {published data only}

- Mancini C. Erdosteine, the second generation mucolytic: international up‐dating of clinical studies (adults and paediatrics). Archivio di Medicina Interna 1996;48:53‐7. [Google Scholar]

Pelucco 1981 {published data only}

- Pelucco D, Bernabo Di Negro G, Ravazzoni C. The use of B.I. 1070/P (guacetisal) in inflammatory bronchopneumopathies in the acute phase. Minerva Medica 1981;72(7):423‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Titti 2000 {published data only}

- Titti G, Lizzio A, Termini C, Negri P, Fazzio S, Mancini C. A controlled multicenter pediatric study in the treatment of acute respiratory tract diseases with the aid of a new specific compound, erdosteine (IPSE, Italian Pediatric Study Erdosteine). International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2000;38:402‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Turrisi 1984 {published data only}

- Turrisi E, Mea A, Bruno G, Vitagliano A. Controlled study of delayed‐action fenspiride in a pneumologic milieu [Studio controllato del fenspiride ritardo in ambito pnrumologico]. Clinica Terapeutica 1984;111(4):339‐46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wang 2005 {published data only}