Summary

We present a method for efficiently identifying clusters of identical-by-descent haplotypes in biobank-scale sequence data. Our multi-individual approach enables much more computationally efficient inference of identity by descent (IBD) than approaches that infer pairwise IBD segments and provides locus-specific IBD clusters rather than IBD segments. Our method’s computation time, memory requirements, and output size scale linearly with the number of individuals in the dataset. We also present a method for using multi-individual IBD to detect alleles changed by gene conversion. Application of our methods to the autosomal sequence data for 125,361 White British individuals in the UK Biobank detects more than 9 million converted alleles. This is 2,900 times more alleles changed by gene conversion than were detected in a previous analysis of familial data. We estimate that more than 250,000 sequenced probands and a much larger number of additional genomes from multi-generational family members would be required to find a similar number of alleles changed by gene conversion using a family-based approach. Our IBD clustering method is implemented in the open-source ibd-cluster software package.

We present a method for efficiently identifying clusters of identical-by-descent haplotypes in biobank-scale sequence data, and we demonstrate how these clusters can be used to identify alleles that have been changed by gene conversion. We apply our methods to UK Biobank sequence data.

Introduction

Segments of identity by descent (IBD) are shared tracts of DNA that have been inherited from a recent common ancestor who has lived within the past few hundred generations. These segments can be inferred in genotype data from population samples by looking for long tracts of identical-by-state alleles that are present in two or more haplotypes.1

Inferred IBD is useful in many applications,2,3 including IBD mapping,4,5,6,7 detecting signatures of natural selection,8,9 identifying close relatives,10,11,12 inferring demographic history,13 and estimating kinship coefficients,14 effective population size,15,16 migration rates,17 mutation rates,18,19 and recombination rates.20,21

IBD inference is often applied to pairs of haplotypes or pairs of individuals.1,2,5,9,12,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 A limitation of the pairwise approach is that it can be difficult to make use of additional information that comes from considering multi-individual IBD in downstream analyses. Multi-individual IBD has been used to distinguish genotype error from recent mutation and gene conversion,19,29 distinguish between certain familial relationships,30 and identify individuals who may share an ungenotyped causal allele.6

Instead of pairs of haplotypes, we work with clusters of haplotypes, and instead of inferring segments, we infer IBD clusters at each position of interest. A set of haplotypes form an IBD cluster at a locus if they have a recent common ancestor. Moving along the chromosome, haplotypes may leave or join the IBD cluster at points of crossovers. A pairwise IBD segment is defined by two haplotypes along with the beginning and end positions of the IBD segment, whereas multi-individual IBD needs a different approach. For small datasets, one can record the set of haplotypes in each IBD cluster and the genomic positions at which the cluster membership changes.6 However, this approach is unwieldy for large datasets. Instead, we record the cluster containing each haplotype at each position of interest. Thus, the IBD cluster data are like phased genotype data, but with IBD clusters replacing alleles. Indeed, our software outputs the IBD cluster information in a format that is intentionally similar to Variant Call Format (VCF)31 for genotype data (Figure S1), with haplotype cluster indices replacing allele indices. It is not necessary to output IBD clusters at each genotyped variant because IBD status changes slowly along the chromosome. Hence, the output file storing the IBD clusters can have many fewer lines than the VCF file storing the genotype data. The number of columns in the output file of IBD clusters increases linearly with sample size, and the number of lines is independent of sample size. In contrast, the number of output IBD segments from a pairwise approach will tend to increase quadratically with sample size.

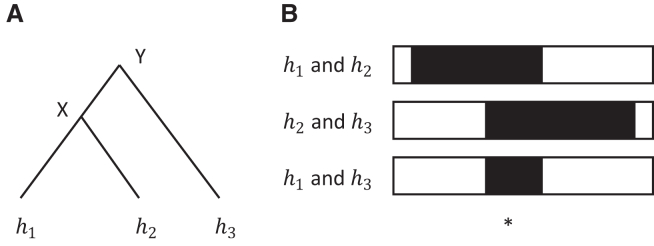

An important property of multi-individual IBD that is typically ignored when analyzing pairwise IBD is transitivity: if haplotypes and share a recent common ancestor X, and haplotypes and share a recent common ancestor Y, then haplotypes and must share a recent common ancestor who will be X or Y (Figure 1A). However, defining pairwise IBD in terms of a minimum shared segment length results in non-transitivity because the additional pairwise IBD segments implied by transitivity may be smaller than the length threshold (Figure 1B). In order to obtain transitivity of IBD, we must accept that pairwise IBD segments implied by transitivity may be relatively short in some cases.

Figure 1.

Transitivity of IBD

(A) The coalescent tree relationship at a given point in the genome is shown for haplotypes and , which are mutually IBD at this location. Haplotypes and have common ancestor X, while haplotypes and , and haplotypes and have common ancestor Y.

(B) Pairwise IBD status (black for IBD, white for non-IBD) is shown for the three pairs of haplotypes along a region of the chromosome around the focal position (denoted ∗). The IBD extends to either side of the focal point until reaching a point of recombination on one of the ancestral lineages. Although the IBD sharing between haplotypes and , and between haplotypes and , is long and may exceed a pre-defined length threshold, the IBD between haplotypes and is relatively short and may not meet the length threshold for pairwise IBD sharing.

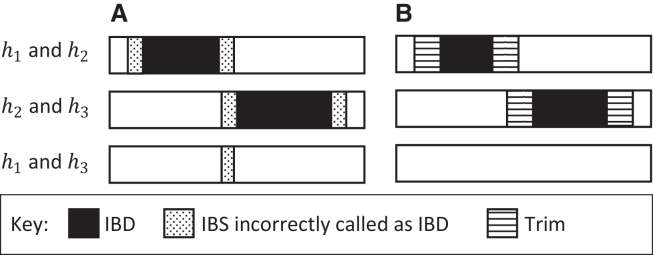

A problem that arises when inferring IBD is that it is difficult to determine the precise endpoints of IBD sharing.9 Estimating segment endpoints that extend beyond the actual IBD segment and then imputing additional IBD to obtain IBD transitivity can lead to incorrect clustering (Figure 2A). Previous approaches to determining multi-individual IBD have generally looked for highly connected clusters of pairwise IBD and then added or removed some pairwise IBD to obtain IBD transitivity.6,32,33 These approaches scale quadratically with cluster size. In this work, we solve the problem by trimming a fixed genetic distance (e.g., 1 cM), from each end of the pairwise identity-by-state (IBS) segments before imputing additional IBD to obtain IBD transitivity (Figure 2B). Although our approach is equivalent to trimming pairwise IBD segments, our use of IBD transitivity results in computation time scaling linearly, rather than quadratically, with sample size.

Figure 2.

IBD transitivity with and without trimming IBS segments

IBD and IBS in a genomic region is shown for the three pairings of three haplotypes (haplotypes and ).

(A) The IBD between haplotypes and is derived from a different recent common ancestor than that of the IBD between haplotypes and . IBS that is not due to the recent common ancestors is incorrectly called as IBD at the ends of the IBD segments. As a result, transitivity leads to a region of IBS being incorrectly called as IBD between haplotypes and .

(B) A trim is applied to the ends of the pairwise IBS regions, and no IBD is called between haplotypes and .

In previous work, we showed that multi-individual IBD is useful for distinguishing genotype error from recent mutation or gene conversion.19,29 Homologous gene conversion occurs during meiosis on the transmitted haplotype when the haplotype that is copied from the parent is interrupted by a short tract copied from the parent’s other haplotype. When this occurs, the transmitted haplotype’s allele is changed at any position at which the parent is heterozygous in the copied region. These allele changes can create discordant alleles within an IBD cluster if the gene conversion arose since the most recent common ancestor.

Because gene conversion tracts are small, with length generally less than 1,400 base pairs,34 gene conversion is difficult to study. One approach to studying gene conversion uses sperm typing.35 Another approach uses multi-generational family data. The use of multi-generational families (as compared to the use of nuclear families) helps to resolve phase and to distinguish alleles changed by gene-conversion from genotype errors.34,36 Two additional approaches do not directly detect gene conversion allele changes but estimate rates of gene conversion using IBD or linkage disequilibrium.18,37 Previous studies using these approaches have shown that gene conversion tracts in humans are on the order of hundreds of kilobases in length,34,35 the genome-wide average rate at which sites are included in gene conversion tracts is approximately per bp per meiosis,18,34,36 and gene conversions hotspots tend to coincide with crossover hotspots.34,35,36

In this work, we show how multi-individual IBD can be used to infer instances of alleles that have been changed by recent gene conversion. We refer to these as “allele conversions.” In contrast to existing methods, our method can be applied to population samples rather than family data or data from sperm typing, and it can infer changed alleles rather than rates. Application of our method to UK Biobank sequence data detects more than 9 million allele conversions.

Subjects and methods

Multi-individual IBD

We say that two haplotypes, and , are confidently identical by descent at marker if the two haplotypes share an identical allele sequence that is at least cM in length and if the shared allele sequence contains marker after trimming cM (where ) from each end of the shared sequence. The default values for and in our ibd-cluster software program are cM and cM, which we found to give accurate results in our analyses of simulated sequence data and UK Biobank sequence data (see Results).

We say that two haplotypes, and , are identical by descent at marker if there is a sequence of haplotypes, such that , and for which each pair of consecutive haplotypes in the sequence is confidently identical by descent at marker . This is an equivalence relation that defines a partition of the haplotypes at a marker. We call this partition the IBD partition at the marker. The sets in the IBD partition are clusters of haplotypes. Each set contains one or more haplotypes. Two haplotypes are in the same set of the partition at a marker if and only if the two haplotypes are identical by descent at the marker.

Algorithm

We first exclude markers with low minor allele frequency (MAF). Except as otherwise noted, IBD clustering analyses in this study exclude markers with MAF <0.1. This retains the most informative markers and reduces the number of discordant alleles caused by genotype error and recent mutation in IBD segments. If a variant has multiple alleles, we define the MAF to be the second largest allele frequency.

We then aggregate sets of consecutive, closely spaced markers to form multi-allelic markers.38,39 The alleles of each aggregate marker are the allele sequences at the constituent markers. We construct aggregate markers by processing individual markers in chromosome order. We aggregate the first marker of an aggregate marker with any following markers that are within a user-specified distance (0.005 cM by default, which is the aggregation distance that we have used for genotype imputation38,39). Each marker is part of exactly one aggregate marker. The base coordinate of an aggregate marker is the median of the base coordinates of the constituent markers. The genetic position of the aggregate marker base position is obtained by linear interpolation from the input genetic map. We exclude markers that are outside the boundaries of the genetic map because extrapolation of genetic distances is inaccurate outside the genetic map. We perform IBD clustering at the aggregate marker positions using the aggregate marker alleles. For convenience, we use the term “marker” to refer to an aggregate marker when describing the IBD clustering algorithm.

We assume that input phased genotypes contain haplotypes with indices , and (aggregate) markers in chromosome order with indices . We use a sliding marker window with length cM. The first window begins with the first marker and ends with the first marker that is at least cM away. The last marker advances by one marker per window. The first marker in a window is the closest marker that precedes the last marker by at least cM.

Let be the sequence of windows. For each window, , let denote the trimmed window that is obtained by trimming cM from each end of . We can restate our previous definition of confidently identical by descent in terms of marker windows: two haplotypes are confidently identical by descent at marker if there is a window in which the haplotypes have the same alleles and is contained in the trimmed window . Our IBD clustering algorithm assigns all haplotypes that are confidently identical by descent at marker to the same IBD cluster. At each marker, the clustering algorithm initially places each haplotype in a separate IBD cluster (one haplotype per cluster). The clustering algorithm merges two IBD clusters at a marker whenever there is a pair of haplotypes, one from each cluster, that are confidently identical by descent at the marker.

We use the positional Burrows-Wheeler transform (PBWT)40 to identify lists of haplotypes that share the same allele sequence in each window. The PBWT’s computation time scales linearly with the number of markers and with the number of haplotypes.40 If a list of haplotypes with the same allele sequences is identified in window , we merge the IBD clusters containing these haplotypes at each marker in the trimmed window since the haplotypes are confidently identical by descent at the markers in the trimmed window. Due to IBD transitivity, it is only necessary to merge IBD clusters for adjacent pairs of haplotypes in the list. It is not necessary to merge IBD clusters for all pairs of haplotypes.

We use a disjoint-set data structure to perform computationally efficient merging of IBD clusters at a marker.41 The disjoint-set data structure stores each distinct set as a tree. Two IBD clusters can be efficiently merged by setting the root node of one tree to be a child of the root node of the other tree. Additional efficiency is gained through the use of path compression and union by rank to reduce the depths of the trees.41

Our algorithm’s memory requirements scale linearly with the number of haplotypes, . The use of a sliding marker window limits the number of disjoint set data structures that must be stored in memory. Technical details and pseudocode for the clustering algorithm are included in the supplemental methods.

Detection of allele conversions

Allele conversions are instances in which an allele on a haplotype carried by one or more individuals in the data has been changed due to a gene conversion occurring in an ancestral meiosis. An allele conversion that occurs after the most recent common ancestor of a cluster of identical-by-descent haplotypes creates discordant alleles in the IBD cluster. Consequently, we can use IBD clusters to detect instances of recent allele conversions. However, if we include the markers with discordant alleles in IBD segments resulting from allele conversion in the multi-individual IBD inference, our algorithm won’t infer IBD between haplotypes that carry discordant alleles and hence won’t find the allele conversions. Consequently, we run multiple IBD clustering and gene conversion analyses that use different sets of markers and then combine the results. In each IBD clustering analysis, we include data across 9 kb then leave a gap of 9 kb so that there is a repeating pattern of length 18 kb. To ensure coverage of the whole genome and to avoid edge effects at the ends of the gaps, we perform three analyses on each chromosome with the 18-kb regions offset by 0, 6, and 12 kb (Figure S2). In each analysis, we first perform IBD clustering at the aggregate markers. After IBD clustering, we detect allele conversions at individual markers in the 9-kb gaps. When detecting allele conversions at a marker in one of the gaps, we use the IBD clustering for the aggregate marker that is closest in terms of genetic distance. The length of a gene conversion tract is less than 1.5 kb with high probability.35 Consequently, within each 9-kb gene gap, we ignore 1.5 kb at each end when detecting allele conversions to ensure that a gene conversion tract containing a detected allele does not overlap with one of the surrounding 9 kb IBD detection regions. After removing these 1.5-kb end regions, 6 kb remains for each offset, and each point in the genome is included in one of the three analyzed 6-kb gene conversion detection regions.

If two identical-by-descent haplotypes carry different alleles at a position, the difference could be due to an allele conversion, but it could also be due to genotype error or mutation. We use multi-individual IBD to distinguish between genotype error and allele conversions. We infer an allele conversion in an IBD cluster if at least two haplotypes in the cluster share one allele and at least two haplotypes share a different allele. If the allele differences in this cluster were due to genotype error, it would require two genotype errors at the same position in the same IBD cluster, which is a low probability event if genotype errors occur independently. Since we require that an IBD cluster must have at least two copies of each of two alleles in order to infer an allele conversion, an IBD cluster must contain at least four haplotypes in order for an allele conversion to be detected.

In order to reduce the problem of mutation creating apparent allele conversions, we consider only markers with MAF greater than 5% when detecting allele conversions. This MAF filter is applied to the input markers and is independent of the MAF filter used in the IBD clustering. It is not necessary to use the same markers for IBD inference and allele conversion detection because IBD clusters change slowly along the chromosome and can be extrapolated to nearby positions. We use the IBD clustering at the aggregate marker that is closest to the position at which we are detecting allele conversions. Non-recurrent recent mutations will have frequency much lower than 5% in a large sample that has relatively few closely related individuals and thus will be excluded when detecting allele conversions. Allele conversions at markers with MAF below 5% will not be detected, and this needs to be considered in downstream analyses. However, most allele conversions occur at markers with higher frequency because allele conversions can only occur if the ancestral individual in whom the gene conversion occurred was heterozygous.

IBD clusters carrying an uncalled deletion can lead to false-positive allele conversion inferences. Genotypes with an uncalled deletion allele are typically miscalled as homozygote genotypes for the non-deleted allele. These miscalled deleted alleles may cause an IBD cluster to appear to contain more than one allele and hence look like an allele conversion. For example, an IBD cluster may contain four haplotypes, each carrying a deletion allele (D) that was inherited from the shared ancestor of these IBD haplotypes. The individuals to which these deletion alleles belong each have another allele (since individuals are diploid). Suppose that two of these individuals carry an A allele and the other two carry a B allele. If the deletion is uncalled, it is likely that the AD individuals will be called as AA, and the BD individuals as BB, leading to the alleles in the cluster being called as two As and two Bs. To account for miscalled deletions when calling allele conversions, we ignore IBD clusters for which all individuals carrying haplotypes in the cluster are homozygous. This step will remove some real allele conversions because all individuals in an IBD cluster may be homozygous by chance.

Simulated data

We simulated 20 regions of size 10 Mb, each with 10,000 simulated individuals, and we simulated an additional 20 regions of size 10 Mb, each with 125,000 simulated individuals. The smaller simulated datasets are used to measure the accuracy of IBD clustering and allele conversion detection because it is possible to extract the true IBD and allele conversions in these data (see below). The larger datasets have a similar number of individuals to the UK Biobank sequence data that we analyzed. We used msprime v1.2 to perform the simulation.42 We used a constant recombination rate of 1 cM/Mb, a mutation rate of per basepair per meiosis, and gene conversion with an initiation rate of 0.02 per Mb and mean tract length of 300 bp. We simulated an exponentially growing population with an initial size of 10,000 and growth of rate 3% per generation for the past 200 generations, for a final size of 3.7 million.

We added uncalled deletions to the simulated data. It is assumed that uncalled deletions will tend to have low frequency in real data. We thus converted 1% of the simulated variants with MAF less than 1% into uncalled deletions. Each deletion extends from the converted variant in the direction of increasing position for an exponentially distributed distance with mean 300 bp. Within this range, alleles on the deletion haplotype are set to be equal to the alleles on the individuals’ other haplotype, thus making the individuals homozygous within the deletion. Although each deletion has frequency less than 1%, the genotypes changed to homozygous genotypes may be from SNPs having any MAF.

We added genotype error to the simulated data. For the main results, each genotype had a probability of having a randomly chosen allele changed. This error rate is based on the discordance rate seen in TOPMed sequence data.9,43 We provided additional results with genotype error rates of and . The total genotype error rate was higher than the added genotype error rate due to the miscalling of uncalled deletions described above. We excluded variants with MAF ≤ 0.01, removed the phase information, and used Beagle 5.4 to statistically phase the genotypes.44

Pairwise IBD rate

We calculate the pairwise IBD rate to measure the amount of IBD that is being inferred. For the IBD cluster data, the pairwise IBD rate is the proportion of pairs of haplotypes that are in the same IBD cluster at a location, averaged over the aggregate marker positions. For the hap-ibd data, the pairwise IBD rate is the sum of the lengths of the inferred IBD segments divided by the number of pairs of haplotypes and divided by the length of the region.

In calculating the pairwise IBD rate for the IBD cluster data, we consider only positions that are more than cM from the ends of the chromosomes and simulated regions. Since we trim cM from the end of each IBS segment, no IBD will be inferred in the first and last cM on a chromosome. There will be reduced IBD inference between and cM from an end of a chromosome because any trimmed IBS segment that is contained within the first or last cM of a chromosome will correspond to an untrimmed IBS segment that is too short to meet the IBS length threshold. Similarly, when calculating the pairwise IBD rate for the hap-ibd data, we consider only positions that are more than cM for the ends of the chromosomes and simulated regions, where is the IBD length threshold.

Determination of false discovery rates in simulated data

We recorded the simulated ancestry trees for the smaller simulations (10,000 individuals) and used the ancestry trees to determine the true IBD and allele conversions as described in supplemental methods.

IBD false discovery rates for the IBD cluster data were determined as follows: at each position in the output IBD cluster data (i.e., at each aggregate marker position), we determined the identical-by-descent haplotype pairs that are implied by the clustering (i.e., all pairs of haplotypes within the same IBD cluster at that position). We then checked the true IBD status for each of the inferred identical-by-descent haplotype pairs at that position. We summed the numbers of false positive identical-by-descent haplotype pairs across all positions and divided by the number of interrogated haplotype pairs, summed across all positions. Similarly, for the hap-ibd data, we determined the portion of each inferred IBD segment that does not overlap with a true IBD segment. We summed the lengths of the falsely inferred IBD and divided by the sum of the lengths of all the inferred IBD segments.

Inferred allele conversions involve an allele that has been inferred to have been changed in two or more haplotypes in an IBD cluster at the locus due to gene conversion. For each inferred allele conversion, we determined whether the corresponding IBD cluster contains a pair of haplotypes with different alleles that are included in the list of true allele conversions. To obtain the allele conversion false discovery rate, we summed the number of false positives across all inferred allele conversions and divided by the number of inferred allele conversions.

UK Biobank data

We analyzed whole autosome sequence data from 125,361 individuals from the UK Biobank.45 These are the White British individuals from the initial release of 150,119 sequenced genomes.46 All subjects gave informed consent and the UK Biobank study was reviewed and approved by the North West Research Ethics Committee of the UK.46 The data were obtained under UK Biobank application number 19934. The 150,119 genomes were phased using Beagle 5.4.44,47 The deCODE genetic map was used for IBD clustering.48

Results

Simulated data

In the smaller simulated data (10,000 individuals), we assessed accuracy when varying the minimum pairwise IBS length, , from 1.5 to 3 cM and varying the IBS segment trim, , from 0.1 to 1.0 cM (Table S1). We did not consider larger values of and because there are not enough data to find much IBD or many allele conversions for larger values for these parameters. We find that IBD and allele conversion false discovery rates are low for most of the settings considered. As expected, false discovery rates and inference rates decrease when or is increased.

In addition to the reporting the pairwise IBD rate, we estimate power (Table S2). We consider that a true IBD segment has been detected by the IBD clustering if there is an aggregate marker within the segment at which the pair of haplotypes are inferred to be in the same IBD cluster. We define power to be the proportion of true IBD segments of a given length that are detected. At stringent settings ( and ), power ranges from 0.35 for 2–2.5 cM segments to 0.8 for 3.5–4 cM segments. At less stringent settings ( and ) power ranges from 0.51 for 1.5–2 cM segments to 0.96 for 3.5–4 cM segments.

We analyzed simulated data with higher rates of genotype error, as well as data with no added genotype error, no uncalled deletions, and perfect haplotype phase (Table S3). The IBD false discovery rate is insensitive to genotype error, while the pairwise IBD rate decreases significantly with increasing genotype error rate.

To investigate the effect of the MAF filter in the IBD clustering, we performed analyses with MAF of 0.05 or 0.2 in addition to the default 0.1 (Table S4). The pairwise IBD rate and false discovery rate are not very sensitive to the choice of MAF filter, but as the minimum MAF is increased, the pairwise IBD rate and false discovery rate increase somewhat.

We also estimated power, pairwise IBD rate, and false discovery rate for the pairwise IBD method hap-ibd,49 with three different parameter settings that have been previously used for hap-ibd analysis of sequence data.29,49,50 We consider that a true IBD segment has been detected by hap-ibd if there is an inferred IBD segment for the pair of haplotypes that overlaps with the true segment. We find that the pairwise IBD rate and false discovery rate with these three parameter settings are similar (Table S5), although the settings make slightly different trade-offs of pairwise IBD rate vs. false discovery rates. We focus here on the results obtained using the parameters suggested for sequence data in the hap-ibd paper.49

Overall, we find that when using the same length threshold for both methods and a trim of 0.5 with the clustering method, the pairwise IBD rate and false discovery rate are similar between hap-ibd and our IBD clustering method, and power is also similar, especially for longer IBD segments (Table S6). For example, with a 2 cM minimum IBD length threshold, the hap-ibd pairwise IBD rate, false discovery rate, and power for 2.5–3 cM segments are 2.4e-5, 6.7e-3, and 0.59, respectively, while the corresponding values for our clustering method with and are 1.8e-5, 2.2e-3, and 0.59.

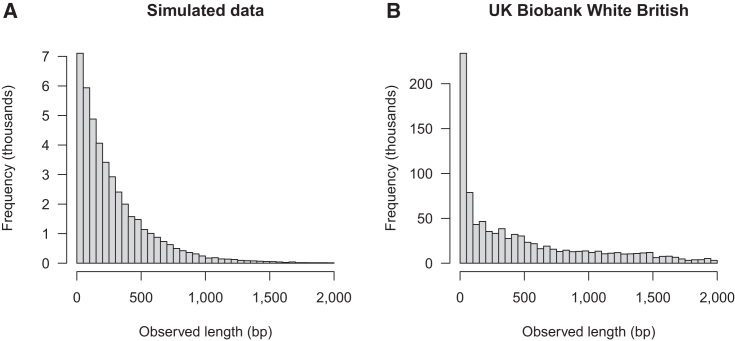

We analyzed the larger simulated data that contains 125,000 individuals with and , because these parameters have a low allele conversion false discovery rate in the smaller simulated data (; Table S1). The average pairwise IBD rate in the larger data was per haplotype pair per locus, which is similar to that in the smaller data (; Table S1). A total of 284,838 allele conversions were detected across the 200 Mb of simulated larger data. These allele conversions were inferred to belong to 226,007 gene conversion tracts. The observable length of a tract is the distance between the first changed allele and the final changed allele, which will generally be significantly shorter than the actual length of the underlying gene conversion tract. In these data, 80.6% of inferred tracts had an observed length of 1 bp, while 0.8% had observed length >1 kb. The distribution of observed lengths that are longer than 1 bp is shown in Figure 3A.

Figure 3.

Observed length of inferred gene conversion tracts

Observed length of inferred gene conversion tracts in (A) simulated data (125,000 individuals with 20 regions of length 10 Mb) and (B) UK Biobank White British. The observed length of an inferred tract is the distance between the first changed allele and the final changed allele (inclusive), which will generally be significantly shorter than the actual length of the underlying gene conversion tract. Only lengths >1 bp are shown: 80.6% of observed lengths were 1 bp in the large simulate data, and 82.9% of observed lengths were 1 bp in the UK Biobank White British data.

Analysis of subsets of the 125,000 individuals demonstrates that the ibd-cluster software scales linearly in computation time and memory requirements with sample size (Figure S3). Analysis of 120,000 sequenced individuals required only 6 GB of memory.

We compared computation time and output file size between hap-ibd49 and ibd-cluster on a single 10 Mb replicate of the 125,000-individual simulated data. We did not apply a gap/offset scheme to either analysis. The hap-ibd analysis used the suggested parameters for sequence data from the hap-ibd paper49 (min-seed = 1, min-extend = 0.2) with the default minimum segment length threshold of 2 cM. The ibd-cluster analysis used and (the default values for the program). The hap-ibd analysis took 12.1 wall clock minutes, while the ibd-cluster analysis took 2.3 wall clock minutes on a 24-core computer. The gzip-compressed hap-ibd IBD output file has size 24 Mb, while the gzip-compressed ibd-cluster IBD output file has size 1.0 Gb. For comparison, the gzipped unphased genotype VCF file which includes all variants has size 1.8 Gb.

UK Biobank data

We analyzed the autosomal UK Biobank White British data with minimum IBD length threshold cM and trim cM. Inferring the IBD clusters for chromosome 1 on a compute node with 96 cores (DNAnexus instance type: mem2_ssd1_v2_x96) took 205 min for a single gap offset. Most of this computation time is spent reading, parsing, and filtering the input VCF records. The chromosome 1 data have more than 31 million variants, of which only 79–80 thousand per offset remain after filtering to remove markers with MAF <0.1 and markers in the gap regions. If we analyze an input file containing only the variants with MAF >0.05, the computation time decreases from 205 min to 11 min.

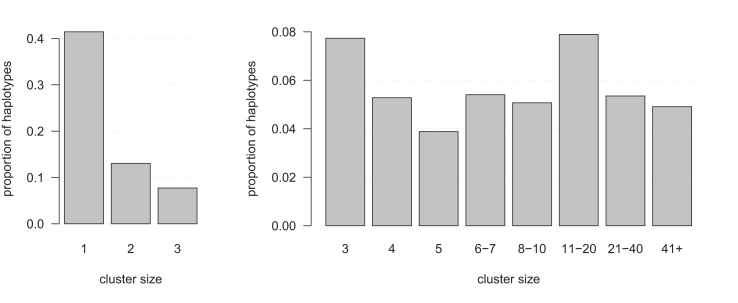

The average pairwise IBD rate was per haplotype pair per locus. On average, 41.4% of haplotypes were members of a cluster of size 1 at a marker, and 37.8% of haplotypes were members of a cluster of size 4 or larger (Figure 4). On average there are 10,878 clusters per marker that had at least 4 haplotypes.

Figure 4.

IBD cluster sizes in the UK Biobank White British autosomal sequence data

Cluster size is shown on the x axis for cluster sizes of in the left panel and in the right panel. The y axis shows the proportion of haplotypes that are in IBD clusters having that size.

We detected 9,313,066 allele conversions across the autosomes. These allele conversions were inferred to belong to 5,961,128 gene conversion tracts. In these data, 82.9% of the tracts had an observed length (distance from first to last observed allele conversion) of 1 bp, which is similar to the corresponding percentage for the simulated data (80.6%), while 4.3% of the tracts had length >1 kb, which is higher than the corresponding percentage for the simulated data (0.8%). The distribution of observed lengths that are longer than 1 bp is shown in Figure 3B. Differences between the distributions of observed lengths for simulated and UK Biobank data (Figure 3) will be partly due to differences in marker characteristics between these two datasets and partly due to different underlying distributions of the actual gene conversion tract lengths.

The number of inferred allele conversions at a given MAF is proportional to the heterozygosity as expected for a relatively homogeneous population (Figure S4), which gives confidence that a high proportion of the inferred allele conversions result from actual gene conversions rather than recurrent mutations or other artifacts.

We also investigated the use of smaller values of . When analyzing chromosome 20 with values of of 0.5 or lower, we found many more spikes in the IBD rate across the chromosome compared to using values of of 0.75 or higher (Figure S5). A spike in the IBD rate may indicate that the trim is insufficient at that location, which may be due to a gap in the sequence data or a lower density of markers in the region. We thus recommend using a trim value of 0.75 cM or higher for most applications involving human sequence data.

Discussion

In this work, we have presented a method for inferring multi-individual IBD in biobank-scale data. The method is computationally efficient and produces simple, compact output that is easily parsed. Analyses of simulated data show that the IBD inferred with this method is highly accurate. The method scales linearly in memory use and in computation time with sample size. Based on our analysis of UK Biobank and simulated data, we estimate that the method can analyze millions of genomes using ordinary computer servers. On a large dataset with 125,000 individuals, the method is more than five times faster than the hap-ibd pairwise IBD method, which in turn is much faster than competing pairwise methods.49

Our approach takes a locus-centric viewpoint to IBD, rather than a segment-centric viewpoint. The combination of IBD clustering and a locus-centric viewpoint enables us to output the IBD in a format that scales linearly with sample size instead of quadratically. Output of IBD clusters can be limited to positions that are separated by one or more kilobases, since IBD cluster membership does not change rapidly over these scales. Although the output of the IBD clusters scales linearly with sample size while pairwise methods scale quadratically, we find that for the sample sizes analyzed in this study, the IBD cluster output file is larger than the corresponding pairwise output file. However, the IBD cluster output file is considerably smaller than the size of the genotype data file.

A significant application of the inferred IBD clusters is IBD mapping. Approaches for using IBD clusters in IBD mapping include testing for association between the trait and each cluster at each position,6 and testing for association between the trait and all clusters at a position by modeling cluster membership as a random effect.32

Our IBD clustering method trims the ends of pairwise IBS segments. This avoids the problem of spurious pairwise IBD perniciously interacting with IBD transitivity to create large spurious clusters of multi-individual IBD. Due to IBD segment endpoint uncertainty, the ends of inferred pairwise IBD segments tend to have lower accuracy.9 IBS segment trimming greatly reduces false positive inference of multi-individual IBD. Our algorithm ensures that inferred IBD satisfies transitivity, which is a property that is implied by the shared-ancestry definition of IBD but is not guaranteed by pairwise IBD methods.6 The default length and trim thresholds in our ibd-cluster software are conservative and ensure that the IBD false discovery rate is very low and that spikes in IBD rate in real data are low. For the application to gene conversion presented in this paper, the low error rate is very important, but for some applications, a different trade-off may be appropriate, which can be achieved through the use of different length and trim thresholds.

Our multi-individual IBD inference method does not currently allow for genotype errors or other causes of mismatch between IBD haplotypes. Our method applies an MAF filter of 0.1 by default because excluding low-frequency variants from sequence data generally reduces the amount of IBD lost to genotype error.47,49

We also presented a method for identifying alleles that have been changed by gene conversion. Analysis of simulated data shows that the detected allele conversions have a very low false discovery rate, particularly when the trim setting for the multi-individual IBD inference is relatively high.

We applied our methods to sequence data on 125,361 individuals from the UK Biobank. We found that on average, more than one-third (37.8%) of haplotypes were members of inferred IBD clusters having 4 or more haplotypes. We used these clusters to detect more than 9 million allele conversions. In contrast, the family-based deCODE study found 3,237 allele conversions using a mix of SNP array data and whole-genome sequence data on 7,229 proband-family sets, with each proband-family set including genetic data on at least seven individuals.36 While more allele conversions could be found using sequence data rather than array data on all families, family-based analyses are limited in the number of meioses that can be interrogated. The average proportion of base pairs in a single meiosis that are included in gene conversion tracts is and heterozygosity is less than per bp in human populations.18,51 Thus, the rate of allele conversions is less than per bp per meiosis, or fewer than 18 allele conversions expected per meiosis across the genome, or 36 per proband. Thus, at least 250,000 sequenced probands plus additional family members would be needed to detect the number of allele conversions detected with our method. Our IBD-based method draws from historical meioses going back tens or hundreds of generations, which enables many more allele conversions to be detected.

Our method for detecting allele conversions does not require close relatives, whereas family-based analyses require multi-generational families in order to distinguish actual allele conversions from genotype error. Similarly, sperm-typing approaches have difficulty with genotype errors and are best for investigating rates of events rather than identifying individual allele conversions.35 Our method removes most genotype errors by requiring that the putative converted allele be carried by at least two identical-by-descent haplotypes.

The distribution of minor allele frequencies of our inferred allele conversions has the expected proportional relationship with heterozygosity. Recurrent mutations and other artifacts would not be expected to follow this relationship, indicating that most of the inferred allele conversions are real and that the numbers of recurrent mutations and other artifacts included in the results is relatively small.

The allele conversions inferred with our method could be used to estimate the distribution of gene conversion tract lengths and the rate of gene conversion across the genome. Our method does not identify which of the two alleles in a discordant IBD cluster is the one that has been introduced through gene conversion. Since our method is based on recent meioses represented by IBD, the inferred allele conversions will have occurred within the past 100 generations or so, and thus the haplotype carrying the converted allele will have low frequency. Thus, it should be possible to determine the identity of the converted allele by considering the frequencies of the two candidate haplotypes.

In this paper, we applied our methods to non-structured simulated data and to relatively homogeneous real data (UK Biobank White British). The IBD clustering and allele conversion detection methods do not make assumptions related to homogeneity (such as Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium), so they are applicable to structured populations. However, the analysis of allele conversion rates as a function of allele frequency that we presented in Figure S4 assumes Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and hence could not be applied in a structured population.

In summary, we provide an approach to IBD detection that is highly scalable, satisfies transitivity, and can be used for locus-based applications such as IBD mapping and detecting alleles changed by gene conversion.

Data and code availability

The IBD cluster software is available from https://github.com/browning-lab/ibd-cluster.

Acknowledgments

This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under application number 19934. The methodological and analytical work performed in this study was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) under award numbers R01 HG005701 and R01 HG008359. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the UK Biobank.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: March 20, 2024

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2024.02.015.

Contributor Information

Sharon R. Browning, Email: sguy@uw.edu.

Brian L. Browning, Email: browning@uw.edu.

Web resources

Beagle, https://faculty.washington.edu/browning/beagle/beagle.html

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Gusev A., Lowe J.K., Stoffel M., Daly M.J., Altshuler D., Breslow J.L., Friedman J.M., Pe'er I. Whole population, genome-wide mapping of hidden relatedness. Genome Res. 2009;19:318–326. doi: 10.1101/gr.081398.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Browning S.R., Browning B.L. Identity by descent between distant relatives: detection and applications. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2012;46:617–633. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sticca E.L., Belbin G.M., Gignoux C.R. Current developments in detection of identity-by-descent methods and applications. Front. Genet. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.722602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Te Meerman G.J., Van Der Meulen M.A., Sandkuijl L.A. Perspectives of identity by descent (IBD) mapping in founder populations. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 1995;25:97–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1995.tb00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Purcell S., Neale B., Todd-Brown K., Thomas L., Ferreira M.A.R., Bender D., Maller J., Sklar P., de Bakker P.I.W., Daly M.J., Sham P.C. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gusev A., Kenny E.E., Lowe J.K., Salit J., Saxena R., Kathiresan S., Altshuler D.M., Friedman J.M., Breslow J.L., Pe'er I. DASH: a method for identical-by-descent haplotype mapping uncovers association with recent variation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;88:706–717. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Browning S.R., Thompson E.A. Detecting rare variant associations by identity-by-descent mapping in case-control studies. Genetics. 2012;190:1521–1531. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.136937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albrechtsen A., Moltke I., Nielsen R. Natural selection and the distribution of identity-by-descent in the human genome. Genetics. 2010;186:295–308. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.113977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Browning S.R., Browning B.L. Probabilistic Estimation of Identity by Descent Segment Endpoints and Detection of Recent Selection. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020;107:895–910. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huff C.D., Witherspoon D.J., Simonson T.S., Xing J., Watkins W.S., Zhang Y., Tuohy T.M., Neklason D.W., Burt R.W., Guthery S.L., et al. Maximum-likelihood estimation of recent shared ancestry (ERSA) Genome Res. 2011;21:768–774. doi: 10.1101/gr.115972.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henn B.M., Hon L., Macpherson J.M., Eriksson N., Saxonov S., Pe'er I., Mountain J.L. Cryptic distant relatives are common in both isolated and cosmopolitan genetic samples. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seidman D.N., Shenoy S.A., Kim M., Babu R., Woods I.G., Dyer T.D., Lehman D.M., Curran J.E., Duggirala R., Blangero J., Williams A.L. Rapid, Phase-free Detection of Long Identity-by-Descent Segments Enables Effective Relationship Classification. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020;106:453–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ralph P., Coop G. The geography of recent genetic ancestry across Europe. PLoS Biol. 2013;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Y., Browning S.R., Browning B.L. IBDkin: fast estimation of kinship coefficients from identity by descent segments. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:4519–4520. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palamara P.F., Lencz T., Darvasi A., Pe'er I. Length distributions of identity by descent reveal fine-scale demographic history. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;91:809–822. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Browning S.R., Browning B.L. Accurate non-parametric estimation of recent effective population size from segments of identity by descent. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;97:404–418. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palamara P.F., Pe'er I. Inference of historical migration rates via haplotype sharing. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:i180–i188. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palamara P.F., Francioli L.C., Wilton P.R., Genovese G., Gusev A., Finucane H.K., Sankararaman S., Genome of the Netherlands Consortium. Sunyaev S.R., de Bakker P.I.W., et al. Leveraging Distant Relatedness to Quantify Human Mutation and Gene-Conversion Rates. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;97:775–789. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tian X., Browning B.L., Browning S.R. Estimating the Genome-wide Mutation Rate with Three-Way Identity by Descent. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019;105:883–893. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou Y., Browning B.L., Browning S.R. Population-Specific Recombination Maps from Segments of Identity by Descent. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020;107:137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naseri A., Yue W., Zhang S., Zhi D. Genome Research; 2023. Fast Inference of Genetic Recombination Rates in Biobank Scale Data. gr. 277676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Browning S.R. Estimation of pairwise identity by descent from dense genetic marker data in a population sample of haplotypes. Genetics. 2008;178:2123–2132. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.084624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kong A., Masson G., Frigge M.L., Gylfason A., Zusmanovich P., Thorleifsson G., Olason P.I., Ingason A., Steinberg S., Rafnar T., et al. Detection of sharing by descent, long-range phasing and haplotype imputation. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:1068–1075. doi: 10.1038/ng.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Browning S.R., Browning B.L. High-resolution detection of identity by descent in unrelated individuals. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;86:526–539. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han L., Abney M. Identity by Descent Estimation With Dense Genome-Wide Genotype Data. Genet. Epidemiol. 2011;35:557–567. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dimitromanolakis A., Paterson A.D., Sun L. Fast and accurate shared segment detection and relatedness estimation in un-phased genetic data via TRUFFLE. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019;105:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naseri A., Liu X., Tang K., Zhang S., Zhi D. RaPID: ultra-fast, powerful, and accurate detection of segments identical by descent (IBD) in biobank-scale cohorts. Genome Biol. 2019;20:143. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1754-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shemirani R., Belbin G.M., Avery C.L., Kenny E.E., Gignoux C.R., Ambite J.L. Rapid detection of identity-by-descent tracts for mega-scale datasets. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:3546. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22910-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tian X., Cai R., Browning S.R. Estimating the genome-wide mutation rate from thousands of unrelated individuals. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2022;109:2178–2184. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2022.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiao Y., Sannerud J.G., Basu-Roy S., Hayward C., Williams A.L. Distinguishing pedigree relationships via multi-way identity by descent sharing and sex-specific genetic maps. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021;108:68–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Danecek P., Auton A., Abecasis G., Albers C.A., Banks E., DePristo M.A., Handsaker R.E., Lunter G., Marth G.T., Sherry S.T., et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2156–2158. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qian Y., Browning B.L., Browning S.R. Efficient clustering of identity-by-descent between multiple individuals. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:915–922. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shemirani R., Belbin G.M., Burghardt K., Lerman K., Avery C.L., Kenny E.E., Gignoux C.R., Ambite J.L. Selecting Clustering Algorithms for Identity-By-Descent Mapping. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2023;28:121–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams A.L., Genovese G., Dyer T., Altemose N., Truax K., Jun G., Patterson N., Myers S.R., Curran J.E., Duggirala R., et al. Non-crossover gene conversions show strong GC bias and unexpected clustering in humans. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.04637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeffreys A.J., May C.A. Intense and highly localized gene conversion activity in human meiotic crossover hot spots. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:151–156. doi: 10.1038/ng1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halldorsson B.V., Hardarson M.T., Kehr B., Styrkarsdottir U., Gylfason A., Thorleifsson G., Zink F., Jonasdottir A., Jonasdottir A., Sulem P., et al. The rate of meiotic gene conversion varies by sex and age. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1377–1384. doi: 10.1038/ng.3669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gay J., Myers S., McVean G. Estimating meiotic gene conversion rates from population genetic data. Genetics. 2007;177:881–894. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.078907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Browning B.L., Browning S.R. Genotype imputation with millions of reference samples. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;98:116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Browning B.L., Zhou Y., Browning S.R. A One-Penny Imputed Genome from Next-Generation Reference Panels. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018;103:338–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Durbin R. Efficient haplotype matching and storage using the positional Burrows-Wheeler transform (PBWT) Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1266–1272. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cormen T.H., Leiserson C.E., Rivest R.L., Stein C. MIT press; 2009. Introduction to Algorithms. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baumdicker F., Bisschop G., Goldstein D., Gower G., Ragsdale A.P., Tsambos G., Zhu S., Eldon B., Ellerman E.C., Galloway J.G., et al. Efficient Ancestry and Mutation Simulation with Msprime 1.0. Genetics. 2022;220 doi: 10.1093/genetics/iyab229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taliun D., Harris D.N., Kessler M.D., Carlson J., Szpiech Z.A., Torres R., Taliun S.A.G., Corvelo A., Gogarten S.M., Kang H.M., et al. Sequencing of 53,831 diverse genomes from the NHLBI TOPMed Program. Nature. 2021;590:290–299. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03205-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Browning B.L., Tian X., Zhou Y., Browning S.R. Fast two-stage phasing of large-scale sequence data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021;108:1880–1890. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bycroft C., Freeman C., Petkova D., Band G., Elliott L.T., Sharp K., Motyer A., Vukcevic D., Delaneau O., O’Connell J., et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018;562:203–209. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Halldorsson B.V., Eggertsson H.P., Moore K.H.S., Hauswedell H., Eiriksson O., Ulfarsson M.O., Palsson G., Hardarson M.T., Oddsson A., Jensson B.O., et al. The sequences of 150,119 genomes in the UK Biobank. Nature. 2022;607:732–740. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04965-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Browning B.L., Browning S.R. Statistical phasing of 150,119 sequenced genomes in the UK Biobank. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2023;110:161–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2022.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Halldorsson B.V., Palsson G., Stefansson O.A., Jonsson H., Hardarson M.T., Eggertsson H.P., Gunnarsson B., Oddsson A., Halldorsson G.H., Zink F., et al. Characterizing mutagenic effects of recombination through a sequence-level genetic map. Science. 2019;363 doi: 10.1126/science.aau1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou Y., Browning S.R., Browning B.L. A Fast and Simple Method for Detecting Identity-by-Descent Segments in Large-Scale Data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020;106:426–437. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cai R., Browning B.L., Browning S.R. G3; 2023. Identity-by-descent-based Estimation of the X Chromosome Effective Population Size with Application to Sex-specific Demographic History. (Bethesda) 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mallick S., Li H., Lipson M., Mathieson I., Gymrek M., Racimo F., Zhao M., Chennagiri N., Nordenfelt S., Tandon A., et al. The Simons Genome Diversity Project: 300 genomes from 142 diverse populations. Nature. 2016;538:201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature18964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The IBD cluster software is available from https://github.com/browning-lab/ibd-cluster.