Summary

Ion channels mediate voltage fluxes or action potentials that are central to the functioning of excitable cells such as neurons. The KCNB family of voltage-gated potassium channels (Kv) consists of two members (KCNB1 and KCNB2) encoded by KCNB1 and KCNB2, respectively. These channels are major contributors to delayed rectifier potassium currents arising from the neuronal soma which modulate overall excitability of neurons. In this study, we identified several mono-allelic pathogenic missense variants in KCNB2, in individuals with a neurodevelopmental syndrome with epilepsy and autism in some individuals. Recurrent dysmorphisms included a broad forehead, synophrys, and digital anomalies. Additionally, we selected three variants where genetic transmission has not been assessed, from two epilepsy studies, for inclusion in our experiments. We characterized channel properties of these variants by expressing them in oocytes of Xenopus laevis and conducting cut-open oocyte voltage clamp electrophysiology. Our datasets indicate no significant change in absolute conductance and conductance-voltage relationships of most disease variants as compared to wild type (WT), when expressed either alone or co-expressed with WT-KCNB2. However, variants c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala) and c.641C>T (p.Thr214Met) show complete abrogation of currents when expressed alone with the former exhibiting a left shift in activation midpoint when expressed alone or with WT-KCNB2. The variants we studied, nevertheless, show collective features of increased inactivation shifted to hyperpolarized potentials. We suggest that the effects of the variants on channel inactivation result in hyper-excitability of neurons, which contributes to disease manifestations.

Keywords: dysmorphism; global developmental delay; epilepsy; KCNB2; channel inactivation, neurodevelopmental disorders, voltage-gated potassium channels

Graphical abstract

Channelopathies arise due to perturbations in ion channel function. In this study, we identify 10 variants in KCNB2 in individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders. Our data suggest that most KCNB2 variants show reduced potassium conductance due to either reduced functional expression or increased channel inactivation.

Introduction

The shab-related KCNB sub-family of voltage-gated potassium (Kv) channels consists of two genes, KCNB1 (MIM: 600397) and KCNB2 (MIM: 608164) that encode KCNB1 (Kv2.1) and KCNB2 (Kv2.2) channels, respectively.1 KCNB1 is well documented as being ubiquitously expressed in several brain regions.2 Characterization of KCNB2 expression in the brain, in comparison, is less defined due to discrepancies in KCNB2 cloning and concurrent antibodies used in different studies.3 Early studies professed mutual exclusivity of subcellular distribution of KCNB1 and KCNB2 in both principal and inhibitory neurons co-expressing them and by extension their roles in controlling neuronal excitability; KCNB1 is restricted to large clusters in the proximal dendrites and soma of neurons,4,5 while KCNB2 is diffusely localized in neuronal dendrites.6,7,8 However, recent reports have detailed KCNB2 expression to localize similarly to KCNB1 in cortical neurons although other neurons may express high levels of either KCNB1 or KCNB2 but not both.3,9,10 In addition to the cortical expression in the central nervous system, KCNB2 has also been identified in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body,11 the basal forebrain,12,13 and the spinal cord.14 Single-cell RNA-seq data show a high expression in excitatory neurons as well as various types of interneurons (Allen Brain Map, Human MTG 10x SEA-AD dataset, https://portal.brain-map.org/atlases-and-data/rnaseq/human-mtg-10x_sea-ad).

KCNB1 and KCNB2, like other Kvs, are outward rectifiers, i.e., they conduct K+ from the cytosol to the extracellular space and provide repolarizing currents that return a depolarized neuron back to the resting state. These channels activate and inactivate slowly compared to the depolarizing sodium currents. Activation is achieved at suprathreshold voltage during an action potential (AP). Such slow activation and inactivation kinetics prolong the duration of KCNB-mediated K+ conductance; these properties are instrumental to their regulation of repolarization and hyperpolarization phases of an action potential.15,16 Consequently, KCNBs help determine interspike interval, AP amplitude, and AP firing fidelity during high-frequency firing.11,17,18,19,20 Assigning these effects to neuronal excitability on homotetrameric complexes of either KCNB1 or KCNB2 is a simplified view. KCNB1 and KCNB2 have been shown to form heterotetrameric complexes both in vitro and in vivo.3,9 In addition, KCNB channels co-assemble with the electrically silent KvS channels and auxiliary β-subunits to form heterotetrameric protein complexes that display drastically different biophysical and pharmacological properties as compared to their homotetrameric counterparts.21,22 In addition to their role in mediating K+ conductance, KCNB1 and KCNB2 also exist as non-conducting clusters caused by the formation of ER/plasma membrane junctions that have numerous functions such as inter-organelle communication and calcium signaling, to name a few.2

Over 29 distinct pathogenic variants in KCNB1 that either truncate or alter the protein sequence of the KCNB1 channels have been identified in individuals suffering from early-onset developmental and epileptic encephalopathies (MIM: 616056).23,24 The KCNB1 variants that were functionally characterized were shown in non-native systems to exhibit a multitude of effects on channel activity such as abolished channel function, reduced current density, deficits in voltage sensing, loss in ion selectivity, and gain of inward cation conductance.24,25,26,27 Expression of some of these variants in cortical neurons led to reduced repetitive firing properties.26 Of note, KCNB1 KO (Kcnb1−/−) mice have preserved brain anatomy and do not exhibit spontaneous epileptic seizures or visual or motor impairment.28 Hippocampal slices of these mice, however, exhibit drug-induced hyperexcitability and stimulation-induced epileptiform activity. Interestingly, homozygous mice expressing a KCNB1 variant (encoding p.Gly379Arg) developed spontaneous seizures as well as proconvulsant- and handling-induced seizures along with being hyperactive and impulsive and having reduced anxiety.29

In this study, we identified several variants in KCNB2 in individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders. Variants in this gene have not been associated with a Mendelian genetic disorder in humans in OMIM previously. Most affected individuals exhibited developmental delays while some also had epilepsy, ADHD, and autism. In addition, we screened the Epi25K dataset and another epilepsy cohort and identified three additional candidate variants. We performed electrophysiological characterization of these variants in oocytes from Xenopus laevis. Our data suggest that most KCNB2 variants show common features of increased channel inactivation with the voltage dependence shifted to hyperpolarized potentials. Based on these observations, we hypothesize that the effects of the variants on channel inactivation may contribute to reduced KCNB2 availability, leading to hyper-excitability of neurons and to disease onset.

Material and methods

Clinical and genetic investigations

Variants were identified by trio sequencing of probands. Exome-sequencing methods have been described elsewhere (for individual 1, see Campeau et al.,30 for 2 see Hunter et al.,31 for 3 see Cohen et al.,32 for 4 see Chevarin et al.,33 for 5 see Schwantje et al.,34 for 6 see Stolerman et al.,35 and for 7 see Hamilton et al.36). The cohort was assembled with the help of Matchmaker Exchange platform tools.37 All clinical information is shared in accordance with local institutional ethical review boards and is in accordance with the ethical standards of the overseeing committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and proper informed consent. A consent for the publication of the photographs included here was obtained from parents or legal guardians.

Molecular biology and channel expression

Frog manipulations were performed in accordance with the Canadian guidelines and have been approved by the ethics committee of University of Montréal. Oocytes from Xenopus laevis were surgically obtained as described elsewhere.38 The human KCNB2 (GenBank: NM_004770.3) cDNA in pcDNA3.1(+) N terminus HA tag was purchase at Genescript (Clone ID: OHu25595C). All variants were introduced in KCNB2 construct using the QuikChange Lightning site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies) and were subcloned in pcDNA3.1 containing no tag using EcoR1/XhoI restriction sites. The variants and primers (rev/fwd) are listed in Table S1. To generate high-quality and high-copy-number plasmids, the plasmids were amplified using the CopyCutter EPI400 competent bacteria (Lucigen) to decrease insert toxicity and avoid non-desired additional mutations. Complementary RNA (cRNA) was generated by linearizing the plasmids with a restriction enzyme (DraIII) and using the plasmid template for in vitro transcription using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 ULTRA Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For functional expression of the KCNB2 channels, either 1 ng of WT or individual mutant cRNA or 0.5 ng each of WT and one of the mutant cRNA was injected into oocytes and incubated for 12–24 h at 18°C to allow for channel expression.

Electrophysiology

Voltage clamping experiments were performed with a CA-1B amplifier (Dagan Corporation). Currents were recorded in the cut-open oocyte voltage-clamp configuration.39 The external solution used for ionic current recordings contained (in mM): 5 KOH, 110 N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMDG), 10 HEPES, and 2 Ca(OH)2, pH adjusted to 7.1 with methanesulfonic acid (MES). The internal solution contained (in mM): 115 KOH, 10 HEPES, and 2 EDTA, pH adjusted to 7.1 with MES. The oocytes were placed in a three-part chamber (upper, middle, and bottom) containing the external solution. Oocyte membrane exposed in the bottom chamber was permeabilized with 0.2% saponin in internal solution for 30 s to 1 min for direct current injection into the oocyte. Saponin was washed out and bottom chamber filled with internal solution. Conductance and inactivation of KCNB2 variants were recorded using the protocols illustrated in Figures 3 and 5. Both conductance-voltage relation (GV) and inactivation-voltage relation (Inac-V) was fit to a sum of two Boltzmann relation of the form G/Gmax = Minimum + (Amplitude1-Minimum)/(1 + exp((V50(1)-X)/k1)) + (Amplitude2-Amplitude1)/(1 + exp((V50(2)-X)/k2)) and I/Imax = Maximum + (Amplitude1-Maximum)/(1 + exp((V50(1)-X)/k1)) + (Amplitude2-Amplitude1)/(1 + exp((V50(2)-X)/k2)), respectively. The decision to use this fit was based on its fidelity and does not necessarily model the underlying processes. Reversal potential for KCNB2 variants were determined using the deactivation protocol illustrated in Figure 4. The external and internal solutions used for these recordings are described in Figure 4. The concomitant current-voltage (IV) relation was fit to a straight line (linear regression) between −90 and −50 mV; the x-intercept was tabulated as the reversal potential. All data were acquired using the MontreX software (Département de physique, Université de Montréal, Canada) and analyzed and compiled using MatlabR2022a (The MathWorks). Data shown are mean ± SD with n ≥ 5 from at least two independent injections.

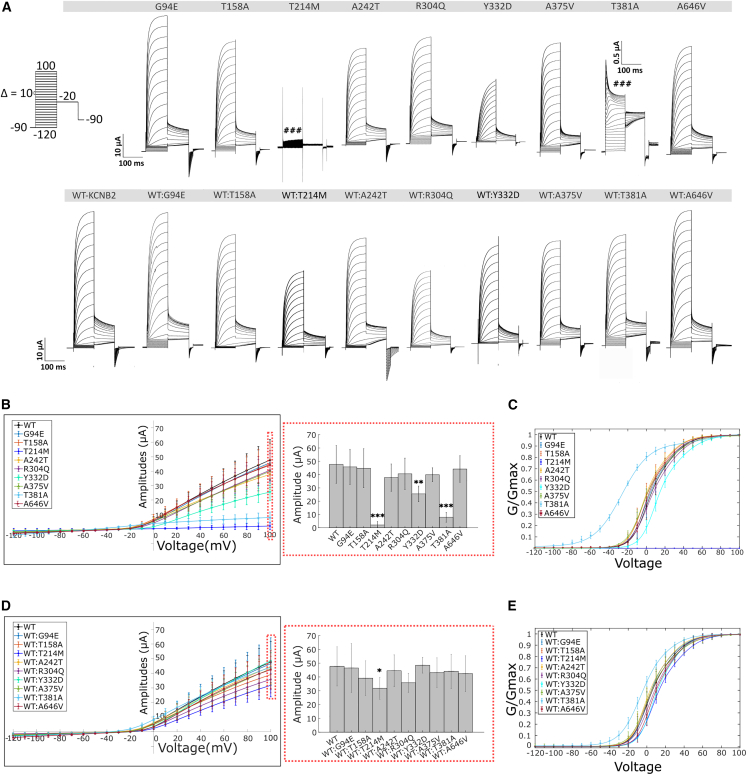

Figure 3.

Activation properties of Kv2.2 variants

(A) Activation currents from oocytes expressing WT-Kv2.2 and variant channels (expressed in the absence [top] and presence [below] of WT, see material and methods) were evoked by stepping from −90 mV to voltages ranging from −120 to +100 mV in 10 mV increments for 100 ms. This was followed by a voltage step to −20 mV for 100 ms and back to −90 mv for 5 s to allow recovery of the channels to deactivated states (protocol illustrated in the left corner). c.641C>T (p.Thr214Met) does not evoke any currents. c.994T>G (p.Tyr332Asp) show reduced currents. c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala) shows transient channel opening followed by a rapid inactivation of ionic currents.

(B) Current-voltage (IV) relationship of Kv2.2 variants (left) and corresponding boxplots of maximal current amplitudes measured at +100 mV (right). p.Thr214Met, p.Tyr332Asp, and p.Thr381Ala show significant reduction in current amplitudes as compared to WT.

(C) Conductance-voltage (GV) relationship of KCNB2 variants when expressed in oocytes alone.

(D and E) IV (D) and GV (E) relationship of Kv2.2 variants when co-expressed with equal amounts of WT. WT:p.Thr214Met show significant reduction in current amplitudes as compared to WT alone. GV curves were best fitted by a sum of two Boltzmann relations of the form G/Gmax = Bottom + (Top1 − Bottom)/(1 + exp((V50(1) − X)/k1)) + (Top2 − Top1)/(1 + exp((V50(2) − X)/k2)). The fitting parameters (V50(1),V50(2), k1, k2) for the GV activation relationships have been compiled in Table 2. Values are provided as means ± SD from n > 6 oocytes per conditions from at least 2 independent experiments. Statistical significance was tested by Kruskal Wallis one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test comparing amplitudes of the different variants to WT. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Figure 5.

Inactivation features of currents by KCNB2 variants

(A) Protocol to measure voltage-dependent inactivation in Kv2.2 variants. To measure inactivation, currents from oocytes expressing Kv2.2 variant channels were evoked by stepping from −90 mV to voltages ranging from −120 to +40 mV in 10 mV increments for 20 s. This was followed by a voltage step to +60 mV for 100 ms and back to −120 mv for 5 s to allow recovery of the channels from inactivation.

(B and C) The raw traces from voltage steps highlighted in thickened line (−90 mV → 40 mV → 60 mV → 120 mV) are highlighted in (B) from oocytes expressing the individual variants alone or in (C) from oocytes expressing both WT and a specific variant. c.641C>T (p.Thr214Met) was excluded in (B) because of lack of any currents evoked by this variant. Currents evoked by c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala) are represented and further explained below.

(D and E) The inactivation current-voltage (IV) relationship of these recordings are plotted. The IV relationship was best fitted by a sum of two Boltzmann relations of the form I/Imax = Top + (Bottom1 − Top)/(1 + exp((V50(1) − X)/k1)) + (Bottom2 − Bottom1)/(1 + exp((V50(2) − X)/k2)). The fitting parameters (V50(1),V50(2), k1, k2) for the IV relationships have been compiled in Table 3. Mean ± SD are shown.

(F) The fitting function mentioned above also calculates the parameter “Bottom2,” which describes the extent of inactivation in these variants expressed either alone (top) or with WT (below). The differences in extent of inactivation between the variants and WT (red dashed lines) were tested for significance using the Kruskal Wallis one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test comparing amplitudes of the different variants to WT-KCNB2. ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001. Values are provided as means ± SD from n > 6 oocytes per conditions from at least 2 independent experiments.

(G) Representative current trace of an oocyte expressing only the p.Thr381Ala variant (blue trace) or only WT (black trace). p.Thr381Ala-expressing oocytes show diminished currents (blue trace) in the inactivation protocol as compared to WT, in a manner like the activation protocol in Figures 2 and 3.

(H) Raw traces of the inactivation protocol of residual currents of the p.Thr381Ala variant.

(I) The IV relationship of the p.Thr381Ala variant (blue line) shows recovery of inactivation with increasing voltages as opposed to WT (dashed fit representing the fit to WT IV shown in D and E).Mean ± SD are shown.

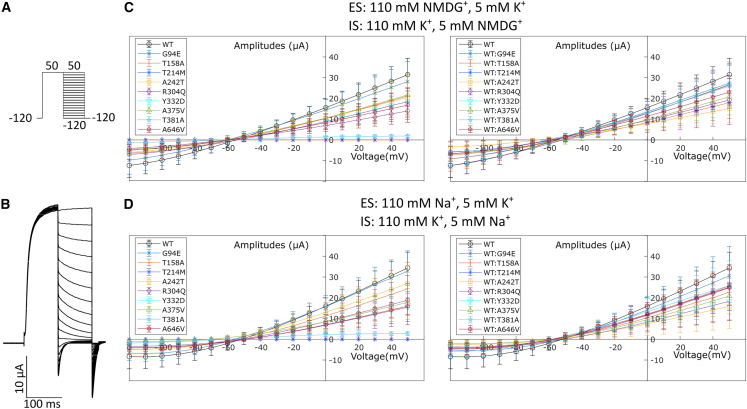

Figure 4.

Reversal potential of Kv2.2 variants

(A) For calculating the reversal potentials of the Kv2.2 variants, currents were evoked by stepping from −120 mV to +50 mV for 100 ms followed by voltages ranging from −120 to +50 mV in 10 mV increments for 100 ms. This was followed by a voltage step to −120 mV for 20 ms and back to the holding potential of −90 mv for 5 s to allow recovery of the channels to deactivated states. The external and internal solutions used in these experiments contained K+ and either NMDG+ or Na+ in the concentrations mentioned in the figure.

(B) Representative raw traces of the reversal potential protocol in an oocyte expressing WT-Kv2.2 in NMDG+ and K+ containing external and internal solutions.

(C and D) The resulting IV curves for this protocol of Kv2.2 variants alone (left) or co-injected with WT (right) in solutions containing either NMDG+ and K+ (C) or Na+ and K+ (D) are shown. The variants do not appear to alter the K+ selectivity of the channel pore (X-intercept data compiled with 95% C.I. in Table S3). Mean ± SD are shown.

Molecular dynamics

We created an in silico homology model of full-length KCNB2 based on the known structure of the Kv1.2/2.1 chimera.40 The model was generated using alphafold2.41 The variants discussed here in the manuscript were introduced into the homology structure and the channels set into an in silico membrane containing: 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC): 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE):stearoyl-sphingomyelin (DPSM) in a molar ratio of 59:9:32 and inner leaflet: POPC:POPE:1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine (POPS):DPSM:1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoinositol (POPI) in a molar ratio of 25:38:16:14:7. The system was set in water containing 150 mM KCl at a temperature of 300K using charmm-gui.42,43,44 The different mutant channels as well as the wild-type channel were equilibrated and simulated in silico for 100 ns using NAMD.45

Results

Clinical characteristics

The clinical phenotypes of the six individuals with de novo or dominantly transmitted variants in KCNB2 are outlined in Table 1. Five variants were de novo, and one was inherited from a symptomatic father. Individual 7 inherited the variant from an unaffected mosaic father. The age at last evaluation ranged from 21 months of life to 18 years. Individuals were born at term and had normal birth growth parameters. Growth parameters, at last visit, were within the normal range in all individuals.

Table 1.

Main clinical features of the affected and phenotyped individuals

| Individual | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KCNB2 variant (NM_004770.3) | c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala) | c.281G>A (p.Gly94Glu) | c.1937C>T (p.Ala646Val) | c.641C>T (p.Thr214Met) | c.994T>G (p.Tyr332Asp) | c.911G>A (p.Arg304Gln) | c.827C>T (p.Pro276Leu) |

| Inheritance | de novo | de novo | inherited | de novo | de novo | de novo | inheriteda |

| Sex | female | male | female | male | female | male | male |

| Age at last assessment | 5 years | 2.5 years | 3 years | 18 years | 21 months | 9 years | 15 years |

| Medical history | |||||||

| Brain anomalies (MRI results) | + | N/A | – | N/A | + | N/A | – |

| Cardiac anomalies | + | + | – | – | N/A | N/A | – |

| Urogenital anomalies | + | + | – | – | – | – | – |

| Ophthalmological anomalies | + | + | – | + | + | N/A | – |

| Growth and development | |||||||

| DD | + | + | + | + | +b | + | + |

| ID | + | N/A | + | + | + | + | + |

| Autistic features | – | N/Ac | – | mild | N/Ac | mild | mild |

| Epilepsy | +d | – | – | – | – | – | +e |

| Dysmorphisms | |||||||

| Facial | + | + | + | – | + | + | – |

| Hand | – | + | + | – | + | + | – |

| Synophrys | – | + | – | + | – | – | – |

| Other features | |||||||

| Hypotonia | + | +f | – | – | – | – | – |

| ADHD | – | – | – | N/A | – | + | – |

Abbreviations are as follows: N/A, not available; DD, developmental delay; ID, intellectual disability; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, mosaic.

Inherited from an asymptomatic father, +

Severe

Too young to make an autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnosis, +

Seizure effectively treated with Levetiracetam, +

Multiple anti-seizure medication (refer to supplemental information), +

Hypotonia with ataxic cerebral palsy; please refer to case reports in supplemental notes

All seven individuals presented with global developmental delay. Six were diagnosed with intellectual disability. Three individuals presented with mild autistic traits while two were too young to make an autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnosis. Two individuals were medicated with Levetiracetam for seizures. Two individuals had hypotonia including one with ataxic cerebral palsy. One individual was diagnosed with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Five individuals presented with various facial dysmorphisms (see Figure 1 for Individuals 1 and 4). Synophrys was observed in two individuals. A broad forehead was noted in two individuals. Hand anomalies were described in four individuals with one presenting with clinodactyly and another with nail hypoplasia. Mild blepharoptosis, beaked nose, flat mid face, frontal bossing, full lower lip, tongue protrusion and high palate were noted in one individual each.

Figure 1.

Photographs of two of the affected individuals

Left: individual 1 through the years. Photos and X-rays of her hands and feet, illustrating nail hypoplasia and aplasia, and terminal phalanx hypoplasia (brachytelephalangia). Photos were taken at age 14 months; top right picture at 2 years 7 months. Right: individual 4, illustrating synophrys and nail hypoplasia. The proband was 18 years old at time of photo.

Ophthalmological anomalies were found in four individuals. One individual presented with cortical vision impairment, Duane syndrome, hyperopia, astigmatism, and cataracts. Delayed visual maturation, myopia, or severe strabismus were found in the other three individuals.

Two individuals had heart anomalies, notably one with aortic dilation and one with an abnormal trabeculation of the left ventricular myocardium. Two individuals had genitourinary malformations: one with a neurogenic bladder and the other with a suggestion of a slight shawl scrotum.

One individual was diagnosed with diabetes, gingival fibromatosis, low bone density, and oropharyngeal dysphagia. She (individual 1, with the c.1141A>G [p.Thr381Ala] variant) seemed to have more extensive involvement than the others (see supplemental note for case reports), and her phenotype overlapped partially with Zimmerman-Laband (ZLS [MIM: 135500, 616455, 618658]) and DOORS (MIM: 220500) syndromes, which are neurodevelopmental disorders with epilepsy (treated with Levetiracetam) and hypoplasia of the terminal phalanges and nails. Of relevance, we have previously reported pathogenic variants in potassium channels KCNH1 (MIM: 603305) and KCNN3 (MIM: 602983) in ZLS46,47 and vacuolar ATPase subunit ATP6V1B2 (MIM: 606939) in ZLS and DOORS syndrome.46,48

To identify additional candidate variants, we searched epilepsy study datasets. A missense variant (c.724G>A [p.Ala242Thr]) was identified in an individual with sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP), from a SUDEP study.49 Additionally, c.472A>G (p.Thr158Ala) was identified in two individuals with NAFE (non-acquired focal epilepsy [MIM: 604364, 245570]) and c.1124C>T (p.Ala375Val) in one individual with GGE (genetic generalized epilepsy [MIM: 600669]), all from the Epi25 exome study variant server.50 The variants were selected as they were absent in gnomAD and affected highly conserved residues. Additional clinical details or parental samples for segregation of the variants were not available to us, so there is more uncertainty (compared to the first 6 variants identified) regarding the involvement of the variants in the neurological phenotypes of the individuals.

Using ACMG criteria51 through the Varsome Classifier,52 all variants were predicted to be pathogenic or likely pathogenic (see criteria used in Table S2). The gnomAD missense tolerance score53 for KCNB2 is relatively high with a Z score of 2.25 (range −5 to 5) since there were 511 expected missense variants but only 368 were observed. We have assessed the tolerance of each affected amino acid to missense variants using Metadome,54 and all amino acids are intolerant to missense variants, with scores in Table S2 and the tolerance landscape of the proteins in Figure S1. Additionally, Table S2 shows the pathogenicity prediction and conservation scores obtained from Ensembl’s Variant Effect Predictor for various commonly used tools.55

Effect of KCNB2 variants on functional expression and activation kinetics

The topology of a KCNB2 monomer, like that of other Kv channels, consists of an N terminus, hexahelical transmembrane domain including a pore-helix (P loop ion selectivity filter), and a C-terminus (Figure 2A). Most of the amino acids altered in the KCNB2 variants characterized in this study are highly conserved in homologous proteins across different species (Figure 2B) and in human KCNB1 (not shown). The exception is amino acid position 646 (KCNB2), which exists as alanine in some species (including humans) and co-incidentally as valine in others. This might suggest it is not the only factor contributing to an individual’s phenotype. 3D protein structures of KCNB2 and distribution of the variants characterized in this study are shown in tetrameric (top view, Figure 2C) and monomeric (side view, Figure 2D) configuration based on the homology model of the known structure of the Kv1.2/2.1 chimera.40

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of mutations in Kv2.2

(A) Topology of Kv2.2 channel and schematic representation of distribution of KCNB2 variants. The variants are in the following regions: c.281G>A (p.Gly94Glu) and c.472A>G (p.Thr158Ala) in the N terminus; c.641C>T (p.Thr214Met) in the S1-S2 linker; c.724G>A (p.Ala242Thr) in the S2; c.827C>T (p.Pro276Leu) in the S3; c.911G>A (p.Arg304Gln) in the S4; c.994T>G (p.Tyr332Asp) in the S4-S5 linker; c.1124C>T (p.Ala375Val) and c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala) in the pore helix; and c.1937C>T (p.Ala646Val) in the C terminus.

(B) Alignment of the variant Kv2.2 amino acids across different species.

(C and D) Homology model and variant distribution of Kv2.2 as a tetramer (top view, C) and as a monomer (D) based on the known structure of the Kv1.2/2.1 chimera.40 The model was generated using alphafold2.41

To assess biophysical properties and functional expression of the KCNB2 mutants, the cRNAs generated from the plasmids encoding the individual mutants were injected into oocytes of Xenopus laevis either alone (1 ng) or in equal amounts with WT-KCNB2 (0.5 ng each). 16–24 h post-injection, the currents were studied using the cut-open oocyte voltage clamp technique. To record absolute amplitudes of K+ conductance, the channels were held at −90 mV followed by a depolarizing pulse to 100 mV for 200 ms (Figure 3A). Most variants, when expressed either alone or with WT, did not show a significant change in current amplitudes when compared to WT. Exceptions are the c.641C>T (p.Thr214Met) and c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala) variants; these mutants showed complete and strong abrogation of K+ conductance, respectively (Figure 3B). K+ conductance was rescued when the mutants were co-expressed with WT-KCNB2 (Figure 3D). The c.641C>T (p.Thr214Met) variant, when co-expressed with WT-KCNB2, and the c.994T>G (p.Tyr332Asp) variant, when expressed alone, show significant reduction in current amplitudes as compared to WT-KCNB2 (Figures 3B and 3D; Table 2).

Table 2.

Activation properties of Kv2.2 variants

| Variants |

Without WT |

With WT |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current amplitudes (±SD) [μA] | V50(1) (mV) | k1 | V50(2)(mV) | k2 | Current amplitudes (±SD) [μA] | V50(1)(mV) | k1 | V50(2)(mV) | k2 | |

| WT | 47.7 ± 14.2 | −1.9 ± 5.4 | 6.7 ± 0.9 | 24.4 ± 5.9 | 12.3 ± 2.1 | 47.7 ± 14.2 | −1.9 ± 5.4 | 6.7 ± 0.9 | 24.4 ± 5.9 | 12.3 ± 2.1 |

| p.Gly94Glu | 45.8 ± 13.2 | −1.6 ± 5.8 | 6.7 ± 0.6 | 24.5 ± 4.4 | 12.3 ± 1.7 | 46.5 ± 17.7 | −1.4 ± 5.2 | 6.7 ± 0.8 | 26.1 ± 10.7 | 12.3 ± 2.4 |

| p.Thr158Ala | 44.8 ± 14.7 | −5.6 ± 5.9 | 6.7 ± 0.8 | 20.4 ± 6.9 | 12.1 ± 2.0 | 39.1 ± 12.6 | −2.2 ± 5.7 | 6.8 ± 0.6 | 26.3 ± 8.2 | 13.8 ± 2.3 |

| p.Thr214Met | 2.1 ± 2.6c | N/A | 31.8 ± 7.9a | 5.0 ± 2.9 | 7.5 ± 0.6 | 34.6 ± 4.8a | 13.5 ± 1.6 | |||

| p.Ala242Thr | 37.7 ± 10.3 | −6.6 ± 3.5 | 6.7 ± 0.5 | 18.8 ± 5.6 | 12.3 ± 1.4 | 44.5 ± 11.6 | −3.9 ± 5.4 | 6.6 ± 0.5 | 21.8 ± 7.6 | 11.8 ± 1.9 |

| p.Arg304Gln | 40.6 ± 11.8 | −1.2 ± 3.0 | 8.2 ± 0.9b | 26.6 ± 5.0 | 13.4 ± 2.1 | 35.8 ± 6.9 | 0.8 ± 3.9 | 7.7 ± 0.4a | 27.4 ± 5.2 | 12.9 ± 1.0 |

| p.Tyr332Asp | 25.5 ± 5.9b | 7.6 ± 3.2b | 7.1 ± 0.6 | 36.4 ± 5.2b | 13.9 ± 1.6 | 48.5 ± 5.7 | 4.4 ± 2.8 | 7.0 ± 1.1 | 30.3 ± 5.3 | 10.8 ± 1.8 |

| p.Ala375Val | 39.9 ± 5.2 | −6.4 ± 4.4 | 7.5 ± 0.9 | 25.7 ± 6.4 | 14.0 ± 2.9 | 43.1 ± 10.8 | −3.3 ± 6.2 | 7.2 ± 0.9 | 26.5 ± 9.2 | 13.8 ± 2.2 |

| p.Thr381Ala | 7.9 ± 3.7c | −22.7 ± 5.9c | 14.3 ± 0.9c | 59.1 ± 6.4c | 14.0 ± 3.6 | 44.1 ± 12.4 | −7.3 ± 1.6a | 10.3 ± 1.3c | 26.1 ± 9.1 | 12.0 ± 4.9 |

| p.Ala646Val | 44.2 ± 10.0 | −3.3 ± 2.3 | 6.7 ± 0.6 | 22.7 ± 3.3 | 13.3 ± 1.7 | 42.4 ± 12.9 | 1.5 ± 5.1 | 6.2 ± 0.7 | 27.8 ± 5.5 | 10.9 ± 1.8 |

N/A, not analyzed; the amplitudes were too low to determine activation properties; mean ± SD are shown

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001 via Kruskal Wallis one-way ANOVA with post hoc correction for multiple comparisons with Dunn’s post-hoc test

We next characterized the activation properties of the KCNB2 variants by analyzing their conductance-voltage (GV) relationship. Conductance can be inferred from the tabulation of the isochronal current amplitudes at the beginning of the −20 mV step in Figure 3A. The representative raw traces of the corresponding currents are presented from an oocyte that either expresses the individual variants alone (top) or co-expresses both the individual variant and WT (below). The c.641C>T (p.Thr214Met) variant was excluded from the GV analyses due to lack of any activation currents by this mutant. The GV datasets (Figures 3C and 3E) were best fitted by a sum of two Boltzmann distributions that generated two activation midpoints (V50(1) and V50(2)) and two corresponding slope factors (k1 and k2, respectively). These parameters are compiled in Table 2. Of all variants, GV profiles of c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala) and c.994T>G (p.Tyr332Asp) channels showed significant differences when compared to those of WT. However, while c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala) channels showed a ∼20 mV shift to hyperpolarized potentials in activation V50(1) compared to WT, c.994T>G (p.Tyr332Asp) was shifted by 5 mV to depolarized potentials. The other mutants did not show significant differences compared to WT, although higher k1 values were observed for the c.911G>A (p.Arg304Gln) variant. In affected individuals, the variants would be expressed with WT-KCNB2 in a heterozygous manner. We therefore tested the effect on co-expression. While the effects were similar, the voltage dependence and slope of activation was attenuated in the heteromeric as opposed to homomeric expression. This is indicative of difference in activation properties of c.911G>A (p.Arg304Gln), c.994T>G (p.Tyr332Asp), and c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala) as compared to WT, but it is notable that the effects were not conserved throughout the mutants nor were the effects consistent among the variants.

KCNB2 variants show no effect on reversal potential of the channel

We next investigated whether the KCNB2 variants affect the reversal potential of the channel. To do this, we looked at currents evoked by the deactivation protocol illustrated in Figure 4A under conditions of high external NMDG+/Na+ and low K+ and high internal K+ and low NMDG+/Na+. The deactivation protocol involves channel opening of the variants at +50 mV followed by the deactivation of the channel at different voltages ranging from +50 mV to −120 mV. The raw traces shown in Figure 4B are representative of an oocyte expressing WT-KCNB2. The ensuing current voltage relationship from this protocol leads to the determination of the reversal potential of the channel, representative of the voltage with no net current. As shown in Figures 4C and 4D, the reversal potential of all KCNB2 variants lies between −60 and −80 mV (Table S3), which is closer to the equilibrium potential of K+. These results indicate that potassium conductivity by the variants is unaffected in the presence of Na+ or NMDG+ both extra- and intracellularly.

KCNB2 variants show greater extent of inactivation when compared to WT-KCNB2

Many Kv channels undergo inactivation either during subthreshold depolarization (referred to as closed state inactivation) or during suprathreshold membrane depolarization (referred to as open-state inactivation).56 Shab-related KCNB channels are characterized by slow inactivation that strongly influences duration of action potentials during repetitive high-frequency firing of different neuronal subsets. To assess voltage dependence and the extent of this inactivation, we employed the protocol illustrated in Figure 5A; the bold lines in the protocol correspond to the raw traces shown in Figures 5B and 5C when the variants are expressed either alone or with WT-KCNB2, respectively. Both WT-KCNB2 and the variants exhibit slow inactivation as described previously17,57 during sustained depolarizations at +40 mV for up to 20 s.

We next assessed and compared voltage dependence of inactivation of WT-KCNB2 and the variants. All KCNB2 variants exhibit U-shaped inactivation profiles (Figures 5D and 5E) as described previously.56,58 Such profiles are indicative of increased inactivation at negative potentials, which is overcome by channel opening at more depolarized potentials because of increased open probability. To determine the mean free energy required to trigger closed state inactivation, we fitted the data between −150 mV and 10 mV with the sum of two Boltzmann’s equations. As compared to WT, most variants, when co-expressed with WT, show a shift to hyperpolarized potentials of the inactivation characteristics (Figure 5E; Table 3). These effects are even more pronounced when the variants are expressed in the absence of WT, indicating these amino acid substitutions contribute to voltage dependency of inactivation (Figure 5D; Table 3). Most variants also showed an increase in the slope factors of the Boltzmann relations k1 and k2 (Table 3), especially c.911G>A (p.Arg304Gln). The slope factor k can be written as ratio of thermal energy and electrical energy per Volt (RT/zF with R = universal gas constant, T = temperature, z = the apparent gating charge, and F = the Faraday constant), indicating that, in these variants, the apparent electrical charge z driving inactivation was reduced. By comparing the extent of inactivation exhibited by the variants with respect to WT (Figure 5F), most variants showed increased inactivation with the exception of c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala). c.994T>G (p.Tyr332Asp), when expressed alone, showed the greatest extent of inactivation (∼35% more inactivation as WT, Figure 5F). It was remarkable, however, that this effect disappeared in the presence of WT-KCNB2.

Table 3.

Inactivation properties of Kv2.2 variants

| Variants |

Without WT |

With WT |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V50(1)(mV) | k1 | V50(2)(mV) | k2 | V50(1)(mV) | k1 | V50(2)(mV) | k2 | |

| WT | −51.3 ± 11.1 | 11.6 ± 5.0 | −19.9 ± 4.0 | 6.5 ± 1.6 | −51.3 ± 11.1 | 11.6 ± 5.0 | −19.9 ± 4.0 | 6.5 ± 1.6 |

| p.Gly94Glu | −46.9 ± 10.83 | 10.7 ± 4.9 | −23.5 ± 4.7 | 5.1 ± 0.8 | −41.3 ± 13.4 | 9.8 ± 5.0 | −24.0 ± 4.0 | 4.5 ± 0.9 |

| p.Thr158Ala | −58.7 ± 10.3 | 11.9 ± 3.4 | −29.5 ± 4.4a | 5.7 ± 1.7 | −59.1 ± 10.9 | 13.5 ± 3.7 | −29.2 ± 9.5 | 5.5 ± 0.8 |

| p.Thr214Met | N/A | −34.6 ± 5.0 | 7.0 ± 2.1 | −18.5 ± 0.8 | 4.7 ± 1.1 | |||

| p.Ala242Thr | −59.3 ± 5.9 | 18.1 ± 1.8a | −30.4 ± 2.2a | 6.4 ± 0.5 | −57.1 ± 16.1 | 15.4 ± 2.7 | −25.3 ± 3.8 | 6.2 ± 1.4 |

| p.Arg304Gln | −82.9 ± 12.8b | 14.6 ± 2.5 | −37.8 ± 4.5c | 7.1 ± 1.5 | −67.4 ± 11.3 | 18.8 ± 2.1a | −27.6 ± 3.1 | 6.8 ± 0.5 |

| p.Tyr332Asp | −34.1 ± 11.9 | 6.5 ± 2.5 | −16.8 ± 4.9 | 4.3 ± 1.0a | −23.0 ± 3.6a | 5.3 ± 2.1 | −11.0 ± 0.9 | 4.0 ± 0.9a |

| p.Ala375Val | −52.1 ± 9.4 | 9.7 ± 3.2 | −34.0 ± 4.2c | 3.9 ± 1.0b | −54.3 ± 10.3 | 15.0 ± 5.2 | −29.8 ± 4.3a | 6.0 ± 1.6 |

| p.Thr381Ala | N/A | −60.0 ± 11.5 | 12.1 ± 3.4 | −30.4 ± 7.2a | 6.1 ± 1.1 | |||

| p.Ala646Val | −64.7 ± 14.2 | 16.2 ± 3.9 | −29.8 ± 6.7 | 6.2 ± 0.8 | −61.3 ± 9.0 | 13.3 ± 2.2 | −28.3 ± 3.0 | 6.0 ± 0.8 |

N/A, not analyzed; the amplitudes were too low in p.Thr214Met and recovery from inactivation was seen in p.Thr381Ala that prevented determination of their inactivation properties. Mean ± SD are shown.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001 via Kruskal Wallis one-way ANOVA with post hoc correction for multiple comparisons with Dunn’s post-hoc test

Similar to the activation kinetics, where c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala) showed a distinct phenotype with fast inactivation at high depolarizations, this variant showed a behavior distinct to the other variants that we characterized. c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala) opens transiently followed by quick inactivation to a new baseline (Figure 3A). To check whether this variant persists in this inactivated state, we kept the channel open for a longer time with our inactivation protocol. As shown in the raw traces represented in Figure 5G, oocytes expressing WT-KCNB2 (black trace) showed increasing inactivation with time whereas oocytes expressing the c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala) variant did not show inactivation in addition to the rapid inactivation of the open state (blue trace, Figure 5G, zoomed in Figure 5H) in the 20 s after opening of the channel. In contrast, c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala) increases in current indicating that channels are recovered from inactivation (Figure 5I, cf. dashed WT black fit from Figures 5D and 5E to C1141A>G [p.Thr381Ala] blue data points). The data suggest that there are two types of inactivation in the c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala) mutant: closed state inactivation (typical for KCNB2) and a very rapid open state inactivation. Because of the rapid open state inactivation, we cannot clearly determine how many channels are expressed, which explains the low currents observed in Figure 3A. The rapid inactivation is abolished when co-expressed with WT-KCNB2. The heteromers exhibited activation amplitudes (Figure 3D) and extent of inactivation (Figure 5F) similar to those expressing WT alone (Tables 2 and 3).

In contrast to activation and functional expression, which resulted in variable phenotypes among the variants, an increased inactivation, both in voltage dependence and extent, was common to all variants studied in this work. This communality emphasizes the importance of channel inactivation for the development of the disease.

Discussion

Human homologs of the Drosophila shab family are the KCNB family of voltage-gated potassium channels that contain two known members: KCNB1 and KCNB2. Variants in KCNB1 have been identified in individuals suffering from early-onset developmental and epileptic encephalopathies.23 In this study, we identified several variants in KCNB2 clinically and from the Epi25 and other epilepsy cohorts. The variants identified clinically are in children and are mostly de novo (except for c.1937C>T [p.Ala646Val] and c.827C>T [p.Pro276Leu] variants, which were inherited). Individuals harboring these variants exhibit a wide array of neurological disorders. Most individuals exhibit delays in either global development, motor milestones, or speech/language. These individuals also displayed intellectual disabilities and different dysmorphisms. Dysmorphic facial features were variable across individuals, with synophrys and broad forehead being most common. Functional characterization of the KCNB2 variants revealed a unifying feature: all variants have reduced KCNB2 channel function achieved either by reduced functional expression (c.641C>T [p.Thr214Met], c.994T>G [p.Tyr332Asp], and c.1141A>G [p.Thr381Ala]) or by increased extent of inactivation occurring at more hyperpolarized potentials compared to WT. We, therefore, provide a compelling etiological basis for the onset of neurological disorders in individuals with mutations in KCNB2.

KCNB channels are delayed rectifying channels, i.e., the channels activate and conduct K+ under depolarized membrane potentials and undergo slow inactivation. Activation and inactivation of KCNB channels, like most Kv channels, are regulated by two mechanisms governed by structural rearrangements of the protein referred to as “gating”: activation gating and inactivation gating.59 Activation gating occurs when voltage-sensing S1–S4 domains of Kv channels sense membrane depolarization and undergo conformational changes. These structural changes are communicated to the pore domain by electromechanical coupling that leads to pore opening and channel conductance.60 Inactivation gating involves structural transitions of Kv channels that act as intrinsic negative feedback to inhibit channel conductance and thereby availability, leading to modulation of cellular excitability. Kv2 channels exhibit U-type inactivation arising from pre-open activated but non-conductive channel states.58 Such inactivation profiles entail a lower degree of inactivation at more depolarized potentials (hence the U-shape of voltage dependence).

One of the variants with the most severe disease phenotype is c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala). The affected individual (individual 1, Figure 1; Table 1) harboring this variant suffers from global developmental delay with intellectual disability, seizures, and diabetes (for more information, please refer to case reports in the supplemental note). Electrophysiological properties of the variant corroborate with the severity of the disease. When expressed alone, the current amplitude of the c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala) variant is ∼10% of that of WT (Figures 3B and 5G) and is rescued when this variant is co-expressed with WT (Figure 3D). Significant changes in activation midpoint of this variant are seen when expressed either alone or with WT (∼20 and 5 mV shift in V50(1) to hyperpolarized potentials, respectively) and slope factor (increase in k1) is observed (Figures 3C and 3E; Table 2). As mentioned above, normalized current-voltage relationship of inactivation, displayed in Figure 5I, shows an increased recovery from inactivation with increasing voltage (cf. blue line for c.1141A>G [p.Thr381Ala] and dashed black fit for WT). This inactivation profile is very similar to other channels that express the equivalent T→A variant. c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala), present in the channel selectivity filter, is the conserved fourth residue of the TXXTXGYG signature sequence present in all K+ channels.61 The hydroxyl group of this threonine contributes to one of the four K+ binding sites in potassium channels.62 Variants of p.Thr381 equivalent positions in other Kv channels, including the closely related KCNB1, does not produce drastic loss of K+ conductance as seen with KCNB2.61,63,64 When the equivalent threonine in bacterial KcsA channel (T75) was altered to a glycine, the rate of inactivation was slower by ∼2-fold.62 With a substitution to an alanine (identical to c.1141A>G [p.Thr381Ala] in KCNB2 in this study), KcsA, Kv1.5, and Shaker channels all show a loss in C-type inactivation, indicating the importance of p.Thr381 equivalent threonine in these channels in allosteric coupling of the activation gate and the selectivity filter.64 When Coonen et al. modified the equivalent residue to an alanine in KCNB1 (p.Thr377Ala) and Kv3.1 (p.Thr400Ala), the channel variants were resistant to inactivation, thereby losing their U-shape profile as shown by their WT counterparts.63 We also observe similar reduced inactivation of WT:p.Thr381Ala channels (Figure 5E, cyan trace). Given the involvement of potassium channels in insulin secretion and the presence of diabetes in other potassium channelopathies (ATP-sensitive ones),65 it is interesting to note that the individual harboring the c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala) mutation was diagnosed with childhood-onset diabetes but was not found to have pancreas islet cell autoantibodies. It remains to be determined whether diabetes is strongly associated with KCNB2 variants once a larger cohort is established. Previous studies have shown that KCNB2 is expressed in human δ cells of the pancreatic islets.66 Pharmacological inhibition of KCNB2 currents increase action potential duration and amplitude in these cells67 that leads to augmented somatostatin secretion and powerful inhibition of insulin secretion from pancreatic β cells.68 The lack of functional expression of the KCNB2 c.1141A>G (p.Thr381Ala) could potentially mimic KCNB2 inhibition that leads to somatostatin-induced paracrine blocking of insulin secretion and onset of diabetes in the individual harboring this mutation.

The affected individual harboring the c.641C>T (p.Thr214Met) mutation (individual 4, Figure 1; Table 1, and case reports in supplemental notes) exhibited delayed language milestones along with mild autistic traits in infancy, myopia, and synophrys. p.Thr214 is present in the S1-S2 linker; this linker (by virtue of its length) has been shown in KCNA2 (MIM: 176262) to be essential for N-glycosylation that influences their functioning, proper folding, and trafficking to cell surface.69,70 However, the S1-S2 linker glycosylation is not conserved in all Kv channels. The threonine present in position 214 in KCNB2 is conserved in all human Kv channels.71 The c.641C>T (p.Thr214Met) variant, when expressed alone, leads to complete abrogation of K+ conductance (Figures 3A and 3B). The lack of functional expression is rescued when the c.641C>T (p.Thr214Met) variant is co-expressed with WT, albeit significantly lower than WT (Figure 3D; Table 2). Such observations have also been reported in other Kv channels. Synthetic mutations in KCNA4 (MIM: 176266) and KCNC1 (MIM: 176258) and disease-relevant mutations in KCNB1 affecting equivalent threonine residues caused intracellular retention of the protein and little to no channel currents.71,72,73 A change of alanine to the equivalent threonine in KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 also yielded reduced potassium currents with drastic effects on voltage dependence and kinetics of activation and kinetics of deactivation.74

The individual harboring the c.994T>G (p.Tyr332Asp) (individual 5, Table 1 and case reports in supplemental notes) mutation in KCNB2 exhibited global development delay with intellectual disabilities and facial dysmorphisms. The c.994T>G (p.Tyr332Asp) mutation affects the S4-S5 linker of KCNB2. The S4-S5 linker provides electromechanical coupling between the voltage sensing and pore domains that leads to voltage gating of Kv channel function. The S4-S5 linker is very dynamic; this flexible region present on the intracellular side undergoes conformational rearrangements not only during gating and late gating processes, but also during inactivation of some Kv channels.75,76,77,78 Interestingly, this tyrosine present at the end of S4-S5 linker is conserved only in KCNB1 and KCNB2. These channels undergo slow inactivation as compared to other inactivating Kv channels. The c.994T>G (p.Tyr332Asp) variant, when expressed alone or with WT, show minor effects on the coupling between the voltage sensor and pore domains; this is evident by the shift in the voltage dependence of conductance to hyperpolarized potentials in this variant compared to WT (Figure 3; Table 2). However, the major effect of the c.994T>G (p.Tyr332Asp) mutation is the extent of inactivation observed in this variant (Figures 5D and 5F), which is the strongest among the mutants studied here (apart from perhaps c.1141A>G [p.Thr381Ala]). This effect on inactivation, however, is lost on co-expression of this variant with WT (Figures 5E and 5F). This observation indicates a hitherto unappreciated role of the tyrosine residue at positions 328 and 332, respectively, in KCNB1 and KCNB2 on the electromechanical coupling of their activation and in the inactivation of these channels.

Arg304, within S4 of KCNB2, is one of many positively charged arginine and lysine residues present in the S4 that mediate sensitivity of the ion channel to voltage fluxes; movement of these positive charges in S4 during membrane depolarization cause conformational changes that lead to the opening of the central channel pore.79,80 Variants of arginine residues within the S4 of Kv and several other ion channels have been described associated with different channelopathies.23,80,81 Likewise, the individual harboring the c.911G>A (p.Arg304Gln) mutation in KCNB2 (individual 6, Table 1 and case reports in supplemental notes) exhibited delayed motor, speech, and language milestones along with autism spectrum disorder and ADHD. c.911G>A (p.Arg304Gln) has significant effect on the slope factor k1 of channel activation (Table 2), in the absence or presence of WT, consistent with a reduction of the apparent gating charge in the S4 voltage sensor. This variant, either when expressed alone or with WT, unsurprisingly show significant and drastic effects of the voltage dependence and extent of inactivation (Figures 5D–5F; Table 3).

The c.1937C>T (p.Ala646Val) variant affects a residue in the C terminus of KCNB2. The individual harboring this mutation (individual 3, Table 1 and case reports in supplemental notes) displayed onset of regression/neurodegenerative disease along with delayed motor, speech, and language milestones. The c.1937C>T (p.Ala646Val) variant, when co-expressed with WT or alone, increased inactivation and altered voltage dependence of inactivation (Figure 5F; Table 3). The c.281G>A (p.Gly94Glu) mutation was identified in an individual (individual 2, Table 1 and case reports in supplemental notes) with developmental and speech delay along with hypotonia and ataxia cerebral palsy. The other N terminus variant is the c.472A>G (p.Thr158Ala) identified in two individuals with non-acquired focal epilepsy from the Epi25k exome study. Both the N terminus variants show increase in extent of inactivation, especially when expressed with WT (Figure 5F). There is no precedence on the role of the N terminus on the inactivation of KCNB2. Interestingly, previous work on exchanging N terminus of KCNB2 with that of Kv4.2 (KCND2 [MIM: 605410]) accelerated inactivation of the KCNB2 chimera.82 Gly94 is a glutamate at equivalent positions in Kv4.2 channels, just like one of our variants (c.281G>A [p.Gly94Glu]). Detailed investigation on the role of both N and C termini on KCNB2 channel activity is therefore warranted.

Ala375, like Thr381, is present in the pore domain and is located at the pore-helix preceding the selectivity filter of KCNB2. A substitution of this residue to valine (c.1124C>T [p.Ala375Val]) in KCNB2, both in the absence or presence of WT, significantly enhances the extent of inactivation exhibited by these channels (Figures 5D–5F). This variant was identified in an individual with genetic generalized epilepsy from the Epi25 exome study. p.Ala375 is conserved in other Kv channels such as KCNB1, Kv1.5, and Shaker at equivalent positions, but not in KcsA, Kv4s, and hERG channels. Introducing variants at Ala375 equivalent positions in hERG-1 channel (p.Thr618Ala in Kv11.1/encoded by KCNH2 [MIM: 152427] and p.Ala473Thr in Kv1.5, encoded by KCNA5 [MIM: 176267]) alters voltage dependence of inactivation in these channels,83 suggesting the importance of Ala375 and analogous regions in the onset of inactivation in numerous Kv channels.

In addition, we characterized the c.724G>A (p.Ala242Thr) variant identified in an individual with sudden unexpected death in epilepsy.49 Ala242 in KCNB2 is present in the S2 interspersed between two negatively charged glutamates at positions 237 and 247. These glutamates in KCNB2 and equivalent positions in other ion channels are thought to interact with positive charge amino acids in the S4 voltage sensor during resting and activated channel states.79 We speculate that amino acid substitutions of Ala242 should affect the voltage sensing of KCNB2. This is evident in the significant changes in slope factors of the voltage dependence of inactivation in KCNB2-p.Ala242Thr (with or without WT, Table 3) although no changes were observed in activation-voltage relationship of this variant as compared to WT (Figures 2B–2E; Table 2). Of note, Ala242 is conserved in KCNB1 but is replaced by other non-polar aliphatic amino acids in other Kv channels such as Shaker or Kv1.5 (isoleucine at equivalent positions) or Kv4s (leucine/methionine).

Finally, we identified a seventh individual (individual 7, Table 1 and case reports in supplemental notes) harboring a c.827C>T (p.Pro276Leu) mutation. This variant is inherited from an unaffected mosaic father, with the variant present in 10% of the reads in blood DNA. The affected individual exhibited global developmental delay with moderate intellectual disability, refractory epilepsy, and some behavioral issues. He is being treated with multiple anti-seizure medications (for more information, please refer to case reports in supplemental notes). Brain MRI showed prominent perivascular spaces.

Conclusions

We report variants in KCNB2 that are associated with a range of neurological disorders including autism and epilepsy. We show strong evidence that the de novo KCNB2 variants cause neurodevelopmental disorders and that these variants either significantly (1) reduce the currents generated by these Kv channels or (2) shift the voltage dependence of inactivation to hyperpolarized membranes and increase the extent of inactivation as compared to WT. Inactivation, in general, is a cumulative effect that is most impactful when trains of stimulations do not allow for recovery from inactivation before the next stimulus.58 The effect is a reduction of the available functional KCNB2 channels that shapes the duration and interspike intervals of action potentials, leading to changes in cellular excitability in neurons that express these variants. Further experiments in native systems are warranted to corroborate this hypothesis, which provides the underlying etiological basis of how KCNB2 dysfunction causes disease. Despite variation in the associated diseases, it is remarkable that all variants had a common underlying phenotype on the molecular level.

Data and code availability

The published article includes all datasets generated or analyzed during this study, apart from exome-sequencing data which are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions. All experimental data will be freely available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (PJT-169160 to R.B.) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN-2023-04752 to R.B.). CIRCA is a research center financially supported by the Fonds de recherche Québec — Santé. For simulations, computational resources were provided by the Digital Research Alliance of Canada. S.M.S. is supported by the UK Epilepsy Society. Part of this work was undertaken at University College London Hospitals, which received a proportion of funding from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme. We would like to thank Nassima Addour-Boudrahem and the C4R-SOLVE study staff at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute for their contribution to the exome analysis of individual 7. Portions of this work was performed under the Care4Rare Canada Consortium funded by Genome Canada and the Ontario Genomics Institute (OGI-147), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Ontario Research Foundation, Genome Alberta, Genome British Columbia, Génome Québec, and Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario Foundation.

Author contributions

The study was designed by S.B., J.R., R.B., and P.M.C. The individuals were recruited by C.M.L., J.M.S., R.J.L., L.K.C., A.L., D.C.K., S.C.R., S.M.S., E.M.M.H.v.K., K.K., P.M.v.H., F.D., C.D., B.R.S., A.A., M.S., E.S.T., S.S.H., I.T., and P.M.C. The disease manifestations were summarized and compared by C.M. and P.M.C. The experiments were performed or supervised by S.B., J.R., R.B., and P.M.C. The data were analyzed by S.B., J.R., R.B., and P.M.C. The draft was written by S.B., J.R., C.M., R.B., and P.M.C. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: March 18, 2024

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2024.02.014.

Contributor Information

Rikard Blunck, Email: rikard.blunck@umontreal.ca.

Philippe M. Campeau, Email: p.campeau@umontreal.ca.

Web resources

Epi25 exome server, https://epi25.broadinstitute.org/

gnomAD population database, https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/

OMIM, https://www.omim.org/

Supplemental information

Definition of acronyms and details on the scores with links and references for the tools can be found in the dbNSFP v4 "read me" file at https://usf.app.box.com/s/6yi6huheisol3bhmld8bitcon1oi53p.m.

References

- 1.Misonou H., Trimmer J.S. Determinants of voltage-gated potassium channel surface expression and localization in Mammalian neurons. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;39:125–145. doi: 10.1080/10409230490475417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson B., Leek A.N., Tamkun M.M. Kv2 channels create endoplasmic reticulum/plasma membrane junctions: a brief history of Kv2 channel subcellular localization. Channels. 2019;13:88–101. doi: 10.1080/19336950.2019.1568824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kihira Y., Hermanstyne T.O., Misonou H. Formation of heteromeric Kv2 channels in mammalian brain neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:15048–15055. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.074260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trimmer J.S. Immunological identification and characterization of a delayed rectifier K+ channel polypeptide in rat brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:10764–10768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murakoshi H., Trimmer J.S. Identification of the Kv2.1 K+ channel as a major component of the delayed rectifier K+ current in rat hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:1728–1735. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-05-01728.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hwang P.M., Fotuhi M., Bredt D.S., Cunningham A.M., Snyder S.H. Contrasting immunohistochemical localizations in rat brain of two novel K+ channels of the Shab subfamily. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:1569–1576. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-04-01569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guan D., Tkatch T., Surmeier D.J., Armstrong W.E., Foehring R.C. Kv2 subunits underlie slowly inactivating potassium current in rat neocortical pyramidal neurons. J. Physiol. 2007;581:941–960. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.128454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim S.T., Antonucci D.E., Scannevin R.H., Trimmer J.S. A novel targeting signal for proximal clustering of the Kv2.1 K+ channel in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2000;25:385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80902-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bishop H.I., Guan D., Bocksteins E., Parajuli L.K., Murray K.D., Cobb M.M., Misonou H., Zito K., Foehring R.C., Trimmer J.S. Distinct Cell- and Layer-Specific Expression Patterns and Independent Regulation of Kv2 Channel Subtypes in Cortical Pyramidal Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:14922–14942. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1897-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trimmer J.S. Subcellular localization of K+ channels in mammalian brain neurons: remarkable precision in the midst of extraordinary complexity. Neuron. 2015;85:238–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnston J., Griffin S.J., Baker C., Skrzypiec A., Chernova T., Forsythe I.D. Initial segment Kv2.2 channels mediate a slow delayed rectifier and maintain high frequency action potential firing in medial nucleus of the trapezoid body neurons. J. Physiol. 2008;586:3493–3509. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.153734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hermanstyne T.O., Kihira Y., Misono K., Deitchler A., Yanagawa Y., Misonou H. Immunolocalization of the voltage-gated potassium channel Kv2.2 in GABAergic neurons in the basal forebrain of rats and mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 2010;518:4298–4310. doi: 10.1002/cne.22457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hermanstyne T.O., Subedi K., Le W.W., Hoffman G.E., Meredith A.L., Mong J.A., Misonou H. Kv2.2: a novel molecular target to study the role of basal forebrain GABAergic neurons in the sleep-wake cycle. Sleep. 2013;36:1839–1848. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Regnier G., Bocksteins E., Van de Vijver G., Snyders D.J., van Bogaert P.P. The contribution of Kv2.2-mediated currents decreases during the postnatal development of mouse dorsal root ganglion neurons. Phys. Rep. 2016;4 doi: 10.14814/phy2.12731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston J., Forsythe I.D., Kopp-Scheinpflug C. Going native: voltage-gated potassium channels controlling neuronal excitability. J. Physiol. 2010;588:3187–3200. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.191973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsantoulas C., McMahon S.B. Opening paths to novel analgesics: the role of potassium channels in chronic pain. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37:146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du J., Haak L.L., Phillips-Tansey E., Russell J.T., McBain C.J. Frequency-dependent regulation of rat hippocampal somato-dendritic excitability by the K+ channel subunit Kv2.1. J. Physiol. 2000;522 Pt 1:19–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00019.xm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malin S.A., Nerbonne J.M. Delayed rectifier K+ currents, IK, are encoded by Kv2 alpha-subunits and regulate tonic firing in mammalian sympathetic neurons. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:10094–10105. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10094.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohapatra D.P., Misonou H., Pan S.J., Held J.E., Surmeier D.J., Trimmer J.S. Regulation of intrinsic excitability in hippocampal neurons by activity-dependent modulation of the KV2.1 potassium channel. Channels. 2009;3:46–56. doi: 10.4161/chan.3.1.7655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsantoulas C., Zhu L., Yip P., Grist J., Michael G.J., McMahon S.B. Kv2 dysfunction after peripheral axotomy enhances sensory neuron responsiveness to sustained input. Exp. Neurol. 2014;251:115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bocksteins E. Kv5, Kv6, Kv8, and Kv9 subunits: No simple silent bystanders. J. Gen. Physiol. 2016;147:105–125. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201511507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pongs O., Schwarz J.R. Ancillary subunits associated with voltage-dependent K+ channels. Physiol. Rev. 2010;90:755–796. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bar C., Barcia G., Jennesson M., Le Guyader G., Schneider A., Mignot C., Lesca G., Breuillard D., Montomoli M., Keren B., et al. Expanding the genetic and phenotypic relevance of KCNB1 variants in developmental and epileptic encephalopathies: 27 new patients and overview of the literature. Hum. Mutat. 2020;41:69–80. doi: 10.1002/humu.23915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torkamani A., Bersell K., Jorge B.S., Bjork R.L., Jr., Friedman J.R., Bloss C.S., Cohen J., Gupta S., Naidu S., Vanoye C.G., et al. De novo KCNB1 mutations in epileptic encephalopathy. Ann. Neurol. 2014;76:529–540. doi: 10.1002/ana.24263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calhoun J.D., Vanoye C.G., Kok F., George A.L., Jr., Kearney J.A. Characterization of a KCNB1 variant associated with autism, intellectual disability, and epilepsy. Neurol. Genet. 2017;3:e198. doi: 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saitsu H., Akita T., Tohyama J., Goldberg-Stern H., Kobayashi Y., Cohen R., Kato M., Ohba C., Miyatake S., Tsurusaki Y., et al. De novo KCNB1 mutations in infantile epilepsy inhibit repetitive neuronal firing. Sci. Rep. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep15199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thiffault I., Speca D.J., Austin D.C., Cobb M.M., Eum K.S., Safina N.P., Grote L., Farrow E.G., Miller N., Soden S., et al. A novel epileptic encephalopathy mutation in KCNB1 disrupts Kv2.1 ion selectivity, expression, and localization. J. Gen. Physiol. 2015;146:399–410. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201511444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Speca D.J., Ogata G., Mandikian D., Bishop H.I., Wiler S.W., Eum K., Wenzel H.J., Doisy E.T., Matt L., Campi K.L., et al. Deletion of the Kv2.1 delayed rectifier potassium channel leads to neuronal and behavioral hyperexcitability. Gene Brain Behav. 2014;13:394–408. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hawkins N.A., Misra S.N., Jurado M., Kang S.K., Vierra N.C., Nguyen K., Wren L., George A.L., Jr., Trimmer J.S., Kearney J.A. Epilepsy and neurobehavioral abnormalities in mice with a dominant-negative KCNB1 pathogenic variant. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021;147 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2020.105141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campeau P.M., Kasperaviciute D., Lu J.T., Burrage L.C., Kim C., Hori M., Powell B.R., Stewart F., Félix T.M., van den Ende J., et al. The genetic basis of DOORS syndrome: an exome-sequencing study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:44–58. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70265-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunter J.M., Massingham L.J., Manickam K., Bartholomew D., Williamson R.K., Schwab J.L., Marhabaie M., Siemon A., de Los Reyes E., Reshmi S.C., et al. Inherited and de novo variants extend the etiology of TAOK1-associated neurodevelopmental disorder. Cold Spring Harb. Mol. Case Stud. 2022;8 doi: 10.1101/mcs.a006180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen A.S.A., Farrow E.G., Abdelmoity A.T., Alaimo J.T., Amudhavalli S.M., Anderson J.T., Bansal L., Bartik L., Baybayan P., Belden B., et al. Genomic answers for children: Dynamic analyses of >1000 pediatric rare disease genomes. Genet. Med. 2022;24:1336–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.gim.2022.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chevarin M., Duffourd Y., A Barnard R., Moutton S., Lecoquierre F., Daoud F., Kuentz P., Cabret C., Thevenon J., Gautier E., et al. Excess of de novo variants in genes involved in chromatin remodelling in patients with marfanoid habitus and intellectual disability. J. Med. Genet. 2020;57:466–474. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2019-106425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwantje M., de Sain-van der Velden M., Jans J., van Gassen K., Dorrepaal C., Koop K., Visser G. Genetic defect of the sodium-dependent multivitamin transporter: A treatable disease, mimicking biotinidase deficiency. JIMD Rep. 2019;48:11–14. doi: 10.1002/jmd2.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stolerman E.S., Francisco E., Stallworth J.L., Jones J.R., Monaghan K.G., Keller-Ramey J., Person R., Wentzensen I.M., McWalter K., Keren B., et al. Genetic variants in the KDM6B gene are associated with neurodevelopmental delays and dysmorphic features. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2019;179:1276–1286. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.61173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamilton A., Tétreault M., Dyment D.A., Zou R., Kernohan K., Geraghty M.T., FORGE Canada Consortium. Care4Rare Canada Consortium. Hartley T., Boycott K.M. Concordance between whole-exome sequencing and clinical Sanger sequencing: implications for patient care. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2016;4:504–512. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boycott K.M., Azzariti D.R., Hamosh A., Rehm H.L. Seven years since the launch of the Matchmaker Exchange: The evolution of genomic matchmaking. Hum. Mutat. 2022;43:659–667. doi: 10.1002/humu.24373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bossi E., Fabbrini M.S., Ceriotti A. Exogenous protein expression in Xenopus oocytes: basic procedures. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007;375:107–131. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-388-2_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stefani E., Bezanilla F. Cut-open oocyte voltage-clamp technique. Methods Enzymol. 1998;293:300–318. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)93020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Long S.B., Tao X., Campbell E.B., MacKinnon R. Atomic structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel in a lipid membrane-like environment. Nature. 2007;450:376–382. doi: 10.1038/nature06265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jumper J., Evans R., Pritzel A., Green T., Figurnov M., Ronneberger O., Tunyasuvunakool K., Bates R., Žídek A., Potapenko A., et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596:583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brooks B.R., Brooks C.L., 3rd, Mackerell A.D., Jr., Nilsson L., Petrella R.J., Roux B., Won Y., Archontis G., Bartels C., Boresch S., et al. CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jo S., Kim T., Iyer V.G., Im W. CHARMM-GUI: a web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008;29:1859–1865. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee J., Cheng X., Swails J.M., Yeom M.S., Eastman P.K., Lemkul J.A., Wei S., Buckner J., Jeong J.C., Qi Y., et al. CHARMM-GUI Input Generator for NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, and CHARMM/OpenMM Simulations Using the CHARMM36 Additive Force Field. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2016;12:405–413. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phillips J.C., Hardy D.J., Maia J.D.C., Stone J.E., Ribeiro J.V., Bernardi R.C., Buch R., Fiorin G., Hénin J., Jiang W., et al. Scalable molecular dynamics on CPU and GPU architectures with NAMD. J. Chem. Phys. 2020;153 doi: 10.1063/5.0014475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kortüm F., Caputo V., Bauer C.K., Stella L., Ciolfi A., Alawi M., Bocchinfuso G., Flex E., Paolacci S., Dentici M.L., et al. Mutations in KCNH1 and ATP6V1B2 cause Zimmermann-Laband syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:661–667. doi: 10.1038/ng.3282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bauer C.K., Schneeberger P.E., Kortüm F., Altmüller J., Santos-Simarro F., Baker L., Keller-Ramey J., White S.M., Campeau P.M., Gripp K.W., Kutsche K. Gain-of-Function Mutations in KCNN3 Encoding the Small-Conductance Ca(2+)-Activated K(+) Channel SK3 Cause Zimmermann-Laband Syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019;104:1139–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beauregard-Lacroix E., Pacheco-Cuellar G., Ajeawung N.F., Tardif J., Dieterich K., Dabir T., Vind-Kezunovic D., White S.M., Zadori D., Castiglioni C., et al. DOORS syndrome and a recurrent truncating ATP6V1B2 variant. Genet. Med. 2021;23:149–154. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-00950-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leu C., Balestrini S., Maher B., Hernández-Hernández L., Gormley P., Hämäläinen E., Heggeli K., Schoeler N., Novy J., Willis J., et al. Genome-wide Polygenic Burden of Rare Deleterious Variants in Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Epi C., Chen S., Neale B.M., Berkovic S.F. Shared and distinct ultra-rare genetic risk for diverse epilepsies: A whole-exome sequencing study of 54,423 individuals across multiple genetic ancestries. medRxiv. 2023 doi: 10.1101/2023.02.22.23286310. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tavtigian S.V., Harrison S.M., Boucher K.M., Biesecker L.G. Fitting a naturally scaled point system to the ACMG/AMP variant classification guidelines. Hum. Mutat. 2020;41:1734–1737. doi: 10.1002/humu.24088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kopanos C., Tsiolkas V., Kouris A., Chapple C.E., Albarca Aguilera M., Meyer R., Massouras A. VarSome: the human genomic variant search engine. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:1978–1980. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lek M., Karczewski K.J., Minikel E.V., Samocha K.E., Banks E., Fennell T., O'Donnell-Luria A.H., Ware J.S., Hill A.J., Cummings B.B., et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wiel L., Baakman C., Gilissen D., Veltman J.A., Vriend G., Gilissen C. MetaDome: Pathogenicity analysis of genetic variants through aggregation of homologous human protein domains. Hum. Mutat. 2019;40:1030–1038. doi: 10.1002/humu.23798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McLaren W., Gil L., Hunt S.E., Riat H.S., Ritchie G.R.S., Thormann A., Flicek P., Cunningham F. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol. 2016;17:122. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0974-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bähring R., Barghaan J., Westermeier R., Wollberg J. Voltage sensor inactivation in potassium channels. Front. Pharmacol. 2012;3:100. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schmalz F., Kinsella J., Koh S.D., Vogalis F., Schneider A., Flynn E.R., Kenyon J.L., Horowitz B. Molecular identification of a component of delayed rectifier current in gastrointestinal smooth muscles. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:G901–G911. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.5.G901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klemic K.G., Shieh C.C., Kirsch G.E., Jones S.W. Inactivation of Kv2.1 potassium channels. Biophys. J. 1998;74:1779–1789. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77888-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim D.M., Nimigean C.M. Voltage-Gated Potassium Channels: A Structural Examination of Selectivity and Gating. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2016;8 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a029231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blunck R., Batulan Z. Mechanism of electromechanical coupling in voltage-gated potassium channels. Front. Pharmacol. 2012;3:166. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heginbotham L., Lu Z., Abramson T., MacKinnon R. Mutations in the K+ channel signature sequence. Biophys. J. 1994;66:1061–1067. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80887-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matulef K., Annen A.W., Nix J.C., Valiyaveetil F.I. Individual Ion Binding Sites in the K(+) Channel Play Distinct Roles in C-type Inactivation and in Recovery from Inactivation. Structure. 2016;24:750–761. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Coonen L., Mayeur E., De Neuter N., Snyders D.J., Cuello L.G., Labro A.J. The Selectivity Filter Is Involved in the U-Type Inactivation Process of Kv2.1 and Kv3.1 Channels. Biophys. J. 2020;118:2612–2620. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Labro A.J., Cortes D.M., Tilegenova C., Cuello L.G. Inverted allosteric coupling between activation and inactivation gates in K(+) channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:5426–5431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1800559115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ashcroft F.M. ATP-sensitive potassium channelopathies: focus on insulin secretion. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:2047–2058. doi: 10.1172/JCI25495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yan L., Figueroa D.J., Austin C.P., Liu Y., Bugianesi R.M., Slaughter R.S., Kaczorowski G.J., Kohler M.G. Expression of voltage-gated potassium channels in human and rhesus pancreatic islets. Diabetes. 2004;53:597–607. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.3.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Braun M., Ramracheya R., Amisten S., Bengtsson M., Moritoh Y., Zhang Q., Johnson P.R., Rorsman P. Somatostatin release, electrical activity, membrane currents and exocytosis in human pancreatic delta cells. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1566–1578. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1382-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li X.N., Herrington J., Petrov A., Ge L., Eiermann G., Xiong Y., Jensen M.V., Hohmeier H.E., Newgard C.B., Garcia M.L., et al. The role of voltage-gated potassium channels Kv2.1 and Kv2.2 in the regulation of insulin and somatostatin release from pancreatic islets. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut. 2013;344:407–416. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.199083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhu J., Watanabe I., Poholek A., Koss M., Gomez B., Yan C., Recio-Pinto E., Thornhill W.B. Allowed N-glycosylation sites on the Kv1.2 potassium channel S1-S2 linker: implications for linker secondary structure and the glycosylation effect on channel function. Biochem. J. 2003;375:769–775. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Watanabe I., Zhu J., Sutachan J.J., Gottschalk A., Recio-Pinto E., Thornhill W.B. The glycosylation state of Kv1.2 potassium channels affects trafficking, gating, and simulated action potentials. Brain Res. 2007;1144:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McKeown L., Burnham M.P., Hodson C., Jones O.T. Identification of an evolutionarily conserved extracellular threonine residue critical for surface expression and its potential coupling of adjacent voltage-sensing and gating domains in voltage-gated potassium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:30421–30432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708921200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marini C., Romoli M., Parrini E., Costa C., Mei D., Mari F., Parmeggiani L., Procopio E., Metitieri T., Cellini E., et al. Clinical features and outcome of 6 new patients carrying de novo KCNB1 gene mutations. Neurol. Genet. 2017;3 doi: 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]