Abstract

Limited research has explored the effectiveness of insulin resistance (IR) in forecasting metabolic syndrome (MetS) risk, especially within the Iranian population afflicted with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). The present investigation aimed to assess the efficacy of IR indices in predicting the risk of MetS among T2DM patients. Convenient sampling was utilized to select four hundred subjects with T2DM. Metabolic factors and IR indices, including the Waist Circumference-Triglyceride Index (WTI), Triglyceride and Glucose Index (TyG index), the product of TyG index and abdominal obesity indices, and the Metabolic Score for Insulin Resistance (METS-IR), were evaluated. Logistic regression, coupled with modeling, was employed to explore the risk of MetS. The predictive performance of the indices for MetS stratified by sex was evaluated via receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and estimation of the area under the curve (AUC) values. The TyG-Waist Circumference (TyG-WC) index exhibited the largest AUCs in both males (0.91) and females (0.93), while the TyG-Body Mass Index (TyG-BMI) demonstrated the smallest AUCs (0.77 in males and 0.74 in females). All indices significantly predicted the risk of MetS in all subjects before and after adjustment (p < 0.001 for all). The TyG-WC index demonstrated the highest odds ratios for MetS (8.06, 95% CI 5.41–12.00). In conclusion, all IR indices assessed in this study effectively predicted the risk of MetS among Iranian patients with T2DM, with the TyG-WC index emerging as the most robust predictor across both genders.

Keywords: TyG index, Insulin resistance indices, Metabolic syndrome, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Obesity

Subject terms: Endocrinology, Medical research

Introduction

Insulin resistance (IR) arises from inadequate physiological responses due to reduced sensitivity of peripheral tissues to insulin, leading to elevated insulin levels through compensatory mechanisms involving pancreatic β-cell insulin production1. Predominantly affecting muscle, liver, and adipose tissue, IR onset in muscle tissue stems from immune-induced inflammatory changes and excess free fatty acids. With impaired glucose uptake by muscles, surplus glucose is redirected to the liver, triggering increased lipogenesis and release of free fatty acids, thereby promoting fat accumulation outside adipose tissue and exacerbating IR2,3. In individuals with compromised insulin signaling, such as those with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), insulin fails to suppress hepatic gluconeogenesis, even in the fed state, critically influencing blood glucose regulation4. Recognized as a major risk factor for metabolic syndrome (MetS), T2DM, and cardiovascular diseases (CVD), early detection of IR is vital for preventing these conditions5–7. While the glucose clamp technique serves as the gold standard for quantifying IR8, its complexity, cost, and invasiveness limit its routine use in laboratories9,10. Therefore, simpler methods like the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) have been widely adopted since its proposal in 198511. However, challenges with insulin measurement availability and standardization have prompted the exploration of alternative IR prediction approaches, including lipid ratios and visceral fat index (VAI)9,12,13. The triglyceride-glucose index (TyG index), derived from circulating triglyceride and glucose concentrations, has emerged as a promising tool for IR assessment, outperforming HOMA-IR in predictive accuracy13–15. Its strong correlation with IR, high diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, and ease of clinical application make it particularly valuable9,10,12–14. Additionally, obesity, prevalent among individuals with T2DM, is closely linked to IR. Anthropometric measures such as body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC), and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) are commonly used due to their practicality. Combined TyG-related parameters, such as TyG-BMI and TyG-WC, exhibit superior performance compared to the standalone TyG index in IR evaluation16–18. Simultaneous consideration of WC and TG values, known as the waist circumference-triglyceride index (WTI), offers enhanced effectiveness in investigating MetS, T2DM, and CVD prevalence compared to individual parameters19–21. Moreover, the majority of individuals with T2DM are overweight or obese, and it is anticipated that a significant proportion of them will develop MetS22,23.

Given the scarcity of research on IR index effectiveness in predicting MetS risk among Iranian T2DM patients, this study seeks to evaluate the predictive capacity of IR indices, including WTI, TyG index, the product of TyG index and abdominal obesity indices, and METS-IR, in this population.

Results

The prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome (MetS), as per the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) criteria, was found to be 63.3% in the study sample. The demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects across quartiles of the Triglyceride-Glucose (TyG) index scores are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Compared to individuals in quartile 4, those in quartile 1 exhibited significantly lower values for weight, Body Mass Index (BMI), Waist Circumference (WC), Hip Circumference (HC), Fasting Blood Glucose (FBG), Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C), Triglycerides (TG), Total Cholesterol (TC), Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDL-C), LDL/HDL Cholesterol ratio (LDL.HDL-c), Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP), Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP), Diastolic Blood Pressure (DBP), Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP), prevalence of MetS, TyG index score, TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, TyG-Waist-to-Hip Ratio (TyG-WHR), TyG-Waist-to-Height Ratio (TyG-WHtR), Waist Circumference-Triglyceride Index (WTI), and Metabolic Score for Insulin Resistance (METS-IR) (p < 0.001). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons revealed a significant reduction in FBG, HbA1C, TG, TC, LDL-C, AIP, TyG index score, TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, TyG-WHR, TyG-WHtR, and WTI in the third quartile compared to the fourth quartile (p < 0.001). Additionally, a significant reduction in mean weight, BMI, WC, HC, FBG, TG, LDL-C, LDL.HDL-c, AIP, TyG index score, TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, TyG-WHR, TyG-WHtR, WTI, and METS-IR were observed in the second quartile of TyG index score compared to the third and fourth quartiles (p < 0.001). Conversely, a significant increase in HDL-C was observed in the first quartile compared to the fourth quartile (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

The demographic and anthropometric characteristics of subjects across quartiles of TyG score.

| Characteristics (mean (SD) or N (%) | TyG quartiles | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (N = 100) | Q2 (N = 99) | Q3 (N = 101) | Q4 (N = 100) | Total (N = 400) | ||

| Age (years) | 51.79 ± 5.70 | 50.44 ± 4.99 | 51.02 ± 5.52 | 51.08 ± 5.68 | 51.08 ± 5.48 | 0.39a |

| Sex (N) (%) | 0.55b | |||||

| Male | 36 (22.8) | 42 (26.6) | 44 (27.8) | 36 (22.8) | 158 (39.5) | |

| Female | 64 (26.4) | 57 (23.6) | 57 (23.6) | 64 (26.4) | 242 (60.5) | |

| Education (N) (%) | 0.10b | |||||

| Illiterate-elementary | 61 (27.4) | 61 (27.4) | 52 (23.3) | 49 (22) | 223 (55.8) | |

| Middle-school | 21 (26.3) | 14 (17.5) | 25 (31.3) | 20 (25) | 80 (20) | |

| High-school | 13 (19.7) | 20 (30.3) | 16 (24.2) | 17 (25.8) | 66 (16.5) | |

| Collage | 5 (16.1) | 4 (12.9) | 8 (25.8) | 14 (45.2) | 31 (7.8) | |

| Race (N) (%) | 0.44b | |||||

| Fars | 18 (19.4) | 26 (28) | 24 (25.8) | 25 (26.9) | 93 (23.3) | |

| Lore | 38 (22.6) | 42 (25) | 43 (25.6) | 45 (26.8) | 168 (42) | |

| Arab | 44 (31.7) | 31 (22.3) | 34 (24.5) | 30 (21.6) | 139 (34.8) | |

| Job (N) (%) | 0.003b | |||||

| Unemployed | 5 (18.5) | 11 (40.7) | 5 (18.5) | 6 (22.2) | 27 (6.8) | |

| Labor | 15 (19.2) | 17 (21.8) | 32 (41) | 14 (17.9) | 78 (19.5) | |

| Housekeeper | 65 (31) | 48 (22.9) | 47 (22.4) | 50 (23.8) | 210 (52.5) | |

| Employee | 15 (17.6) | 23 (27.1) | 17 (20) | 30 (35.3) | 85 (21.3) | |

| P.A (met-min/week) | 314.72 ± 152.50 | 283.49 ± 133.54 | 312.79 ± 178.75 | 298.17 ± 146.36 | 302.36 ± 153.73 | 0.44a |

| Duration of disease | 7.71 ± 2.84 | 7.42 ± 2.55 | 7.27 ± 2.45 | 7.79 ± 2.80 | 7.55 2.66 | 0.48a |

| Weight (kg) | 70.86 ± 8.52b,c | 72.76 ± 8.53d,e | 77.01 ± 8.90 | 78.12 ± 9.75 | 74.70 ± 9.39 | < 0.001a |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.21 ± 3.29 b,c | 26.46 ± 2.91 d,e | 28.13 ± 3.48 | 28.37 ± 3.22 | 27.30 ± 3.36 | < 0.001a |

| WC (cm) | 97.91 ± 7.93a,b,c | 100.13 ± 8.37d,e | 103.04 ± 6.96 | 103.82 ± 7.67 | 101.23 ± 8.07 | < 0.001a |

| HC (cm) | 102.48 ± 7.67b,c | 104.28 ± 6.98d,e | 106.58 ± 7.03 | 107.86 ± 6.77 | 105.30 ± 7.39 | < 0.001a |

| WHR | 0.95 ± 0.05 | 0.96 ± 0.05 | 0.96 ± 0.04 | 0.96 ± 0.05 | 0.96 ± 0.05 | 0.45a |

| WHtR | 0.59 ± 0.05 b,c | 0.60 ± 0.06 d,e | 0.62 ± 0.06 | 0.62 ± 0.06 | 0.61 ± 0.06 | < 0.001a |

Data are means ± SD for quantitative variables and frequency (percent) for qualitative variables.

BMI; body mass index, WC; waist circumference, HC; hip circumference, WHR; waist-to-hip ratio, WHtR; waist to height ratio, PA; physical activity.

aFrom ANOVA for quantitative variables, bChi-square for qualitative variables.

Table 2.

The biochemical characteristics and insulin resistance indices of subjects across quartiles of TyG index score.

| Characteristics (mean (SD) or N (%) | TyG quartiles | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (N = 100) | Q2 (N = 99) | Q3 (N = 101) | Q4 (N = 100) | Total (N = 400) | ||

| FBG (mg/dL) | 143.01 ± 15.03a,b,c | 152.21 ± 20.82d,e | 161.40 ± 21.52f. | 203.42 ± 37.46 | 165.03 ± 34.08 | < 0.001a |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.61 ± 0.76a,b,c | 8.34 ± 1.06e | 8.31 ± 0.99f. | 9.21 ± 1.08 | 8.37 ± 1.13 | < 0.001a |

| TG (mg/dL) | 107.13 ± 18.74a,b,c | 137.43 ± 19.75d,e | 166.91 ± 18.21f. | 209.66 ± 47.67 | 155.35 ± 47.59 | < 0.001a |

| TC (mg/dL) | 135.87 ± 27.70a,b,c | 153.85 ± 28.53e | 158.09 ± 37.76f. | 191.02 ± 43.08 | 159.72 ± 40.07 | < 0.001a |

| LDL-c (mg/dL) | 71.03 ± 26.23a,b,c | 83.21 ± 26.14d,e | 95.17 ± 41.08f. | 106.49 ± 41.28 | 89.00 ± 36.88 | < 0.001a |

| HDL-c (mg/dL) | 45.79 ± 9.05b,c | 43.56 ± 7.38d | 38.98 ± 7.28f. | 42.99 ± 8.40 | 42.82 ± 8.40 | < 0.001a |

| LDL.HDL-c | 1.58 ± 0.61a,b,c | 1.96 ± 0.70d,e | 2.56 ± 1.42 | 2.59 ± 1.20 | 2.17 ± 1.12 | < 0.001a |

| AIP | 0.37 ± 0.12a,b,c | 0.50 ± 0.10d,e | 0.63 ± 0.10f. | 0.68 ± 0.12 | 0.54 ± 0.16 | < 0.001a |

| SBP(mmHg) | 123.59 ± 10.50b,c | 125.92 ± 10.38e | 129.00 ± 10.71 | 129.64 ± 13.80 | 127.04 ± 11.65 | < 0.001a |

| DBP(mmHg) | 77.37 ± 7.18b,c | 78.53 ± 7.47e | 80.47 ± 8.06 | 82.47 ± 9.28 | 79.71 ± 8.24 | < 0.001a |

| PP(mmHg) | 46.22 ± 7.13 | 47.39 ± 6.11 | 48.52 ± 8.38 | 47.17 ± 9.46 | 47.33 ± 7.89 | 0.22a |

| MAP(mmHg) | 92.77 ± 7.74b,c | 94.33 ± 8.05e | 96.65 ± 8.12 | 98.19 ± 10.05 | 95.49 ± 8.76 | < 0.001a |

| Mets (N) (%) | < 0.001b | |||||

| Yes | 29 (11.5) | 51 (20.2) | 86 (34) | 87 (34.4) | 253 (63.3) | |

| No | 71 (48.3) | 48 (32.7) | 15 (10.2) | 13 (8.8) | 147 (36.8) | |

| TyG index score | 8.99 ± 0.17a,b,c | 9.23 ± 0.07d,e | 9.49 ± 0.06f. | 9.92 ± 0.27 | 9.39 ± 0.40 | < 0.001a |

| TyG-BMI | 233.93 ± 29.77a,b,c | 244.39 ± 26.67d,e | 267.12 ± 33.29f. | 281.84 ± 33.98 | 256.88 ± 36.22 | < 0.001a |

| TyG-WC | 873.61 ± 72.95a,b,c | 924.65 ± 76.51d,e | 978.34 ± 66.89f. | 1030.67 ± 79.55 | 951.95 ± 94.35 | < 0.001a |

| TyG-WHR | 8.53 ± 0.49a,b,c | 8.87 ± 0.51d,e | 9.18 ± 0.45f. | 9.56 ± 0.60 | 9.03 ± 0.64 | < 0.001a |

| TyG-WHtR | 5.31 ± 0.51a,b,c | 5.58 ± 0.57d,e | 5.92 ± 0.58f. | 6.22 ± 0.61 | 5.76 ± 0.66 | < 0.001a |

| WTI | 8.54 ± 0.20a,b,c | 8.82 ± 0.14d,e | 9.05 ± 0.14f. | 9.27 ± 0.22 | 8.92 ± 0.32 | < 0.001a |

| METS-IR | 41.27 ± 5.50a,b,c | 42.94 ± 5.08d,e | 47.97 ± 6.92 | 48.73 ± 5.88 | 45.24 ± 6.68 | < 0.001a |

Data are means ± SD for quantitative variables and frequency (percent) for qualitative variables.

FBG; fasting blood glucose, HbA1c; hemoglobin A1C, TG; triglyceride, TC; total cholesterol, HDL-C; high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C; low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, AIP; atherogenic index of plasma, SBP; systolic blood pressure, DBP; diastolic blood pressure, MAP; mean arterial pressure, PP; pulse pressure, MetS; metabolic syndrome, TyG index; triglyceride and glucose index, WTI; waist circumference-triglyceride index, METS-IR; metabolic score for insulin resistance.

aFrom ANOVA for quantitative variables, bChi-square for qualitative variables.

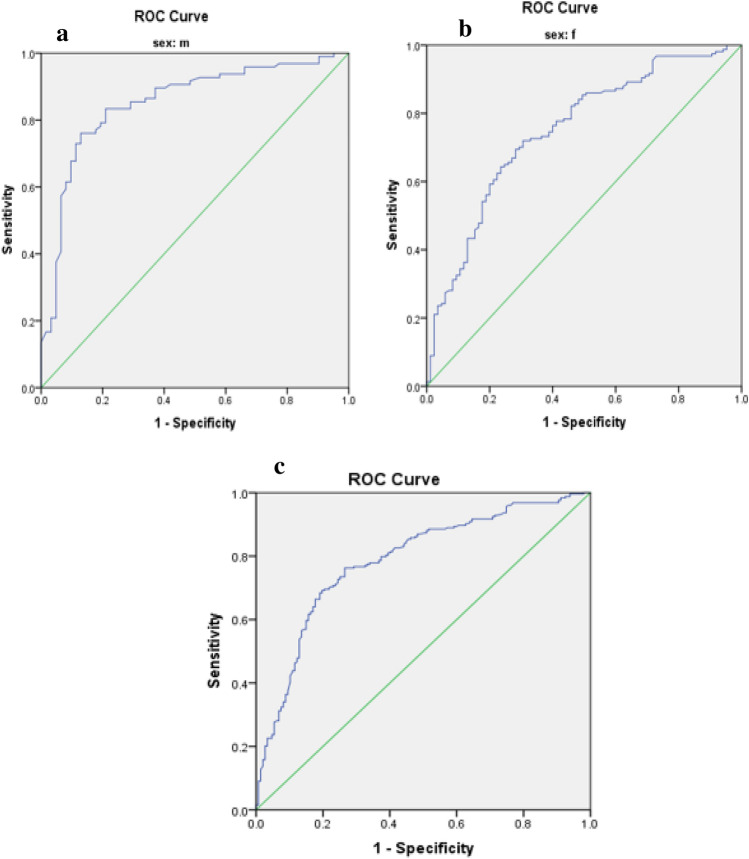

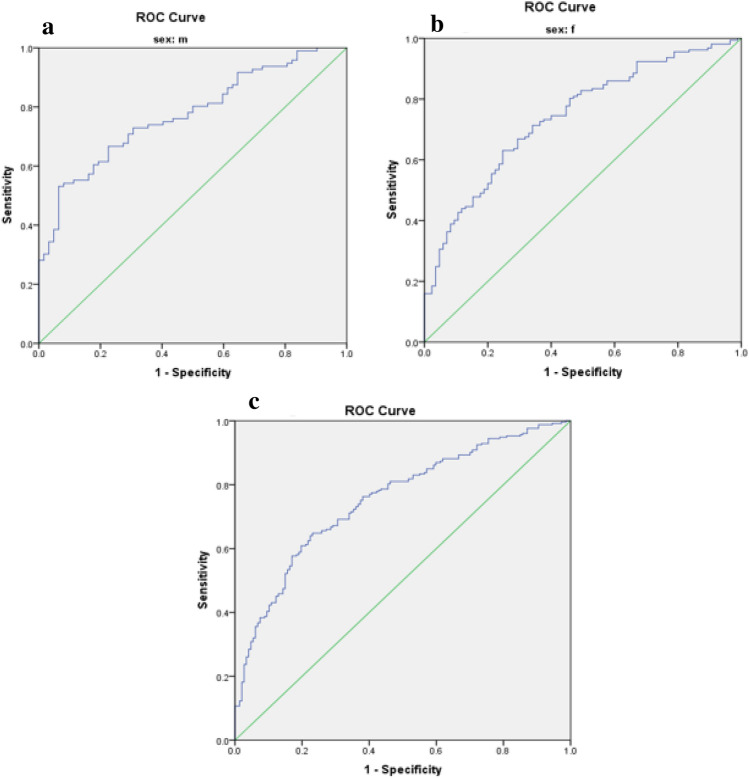

Optimal cut-off values for IR indices in predicting MetS risk in patients with T2DM are presented in Table 3. The predictive performance of anthropometric indices (TyG index, TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, TyG-WHR, TyG-WHtR, WTI, and METS-IR) for MetS, stratified by sex, was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, and the corresponding area under the curve (AUC) values are depicted in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

Table 3.

The optimal cut-off value for indices of insulin resistance in predicting the risk of MetS in patients with T2DM.

| Variable | Cutoff | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | AUC (%) | AUC p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TyG index | |||||

| Male | 9.36 | 0.76 | 0.87 | 0.85 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 9.29 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.75 | < 0.001 |

| Total | 9.30 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.78 | < 0.001 |

| TyG-BMI | |||||

| Male | 256.31 | 0.53 | 0.94 | 0.77 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 261.74 | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0.74 | < 0.001 |

| Total | 255.33 | 0.65 | 0.77 | 0.75 | < 0.001 |

| TyG-WC | |||||

| Male | 929.10 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.91 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 947.80 | 0.84 | 0.92 | 0.93 | < 0.001 |

| Total | 929.10 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.92 | < 0.001 |

| TyG-WHR | |||||

| Male | 9.02 | 0.79 | 0.84 | 0.86 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 8.94 | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.77 | < 0.001 |

| Total | 8.92 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.80 | < 0.001 |

| TyG-WHtR | |||||

| Male | 5.47 | 0.76 | 0.87 | 0.86 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 5.72 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.89 | < 0.001 |

| Total | 5.73 | 0.72 | 0.88 | 0.87 | < 0.001 |

| WTI | |||||

| Male | 8.89 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.88 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 8.91 | 0.74 | 0.84 | 0.82 | < 0.001 |

| Total | 8.91 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0.85 | < 0.001 |

| METS-IR | |||||

| Male | 43.76 | 0.70 | 0.82 | 0.80 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 44.06 | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.80 | < 0.001 |

| Total | 44.06 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.80 | < 0.001 |

Figure 1.

Roc Curve for TyG index (a male, b female, c total).

Figure 2.

Roc Curve for TyG-BMI index (a male, b female, c total).

Figure 3.

Roc Curve for TyG.WC index (a male, b female, c total).

Figure 4.

Roc Curve for total TyG-WHR index (a male, b female, c total).

Figure 5.

Roc Curve for total TyG-WHtR index (a male, b female, c total).

The TyG-WC index exhibited the largest AUCs in both males and females (0.91 and 0.93, respectively) (Fig. 3, Table 3), while the TyG-BMI demonstrated the smallest AUCs (0.77 in males and 0.74 in females) (Fig. 2, Table 3).

Odds ratios (95% CI) for MetS, with IR indices as independent variables among participants, are presented in Table 4. All indices significantly predicted the risk of MetS in all subjects before and after adjustment (p < 0.001). The TyG-WC index presented the highest odds ratios for MetS (8.06, 95% CI 5.41–12.00).

Table 4.

Odds ratios (95% CI) for MetS according to insulin resistance indices.

| Variables | Or (CI) | B | *P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TyG index | |||

| Model 1a | 2.89 (2.28–3.66) | 1.06 | < 0.001 |

| Model 2b | 2.94 (2.31–3.73) | 1.07 | < 0.001 |

| Model 3c | 2.91 (2.28–3.72) | 1.07 | < 0.001 |

| TyG-BMI | |||

| Model 1a | 2.38 (2.02–2.97) | 0.87 | < 0.001 |

| Model 2b | 2.48 (1.97–3.12) | 0.91 | < 0.001 |

| Model 3c | 2.56 (2.02–3.25) | 0.94 | < 0.001 |

| TyG-WC | |||

| Model 1a | 7.72 (5.26–11.32) | 2.04 | < 0.001 |

| Model 2b | 7.87 (5.34–11.60) | 2.06 | < 0.001 |

| Model 3c | 8.06 (5.41–12.00) | 2.08 | < 0.001 |

| TyG-WHR | |||

| Model 1a | 3.01 (2.36–3.82) | 1.10 | < 0.001 |

| Model 2b | 3.16 (2.46–4.05) | 1.15 | < 0.001 |

| Model 3c | 3.12 (2.42–4.02) | 1.13 | < 0.001 |

| TyG-WHtR | |||

| Model 1a | 5.03 (3.70–6.85) | 1.61 | < 0.001 |

| Model 2b | 6.17 (4.38–8.71) | 1.82 | < 0.001 |

| Model 3c | 6.48 (4.52–9.29) | 1.87 | < 0.001 |

| WTI | |||

| Model 1a | 4.19 (3.16–5.56) | 1.43 | < 0.001 |

| Model 2b | 4.22 (3.18–5.61) | 1.44 | < 0.001 |

| Model 3c | 4.16 (3.13–5.55) | 1.42 | < 0.001 |

| METS-IR | |||

| Model 1a | 2.92 (2.30–3.70) | 1.07 | < 0.001 |

| Model 2b | 2.95 (2.32–3.76) | 1.08 | < 0.001 |

| Model 3c | 3.12 (2.42–4.01) | 1.13 | < 0.001 |

*P < 0.05 statistically significant by Multivariable logistic regression. a. model 1: unadjusted. b. model 2: adjusted for age, gender. c. model 3: adjustment for age, gender, race, education, job, duration of disease, physical activity, and medications.

Discussion

The coexistence of Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) in diabetic individuals is associated with the development of both microvascular and macrovascular complications, as evidenced by previous research24,25. Within our study sample, MetS was found to be prevalent in 63.3% of participants. Notably, all insulin resistance (IR) indices investigated demonstrated predictive potential for MetS risk. Among these indices, the TyG-WC index exhibited the most pronounced area under the curve (AUC) values and highest odds ratios for MetS among patients diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM).

In line with our findings, prior investigations have also demonstrated the predictive capability of the TyG index for Metabolic Syndrome (MetS). The predictive capacity of the TyG index can be elucidated by mechanisms involving glucotoxicity and lipotoxicity, alongside the intimate associations of its constituent components (triglycerides and fasting plasma glucose) with insulin resistance, a pivotal factor in MetS pathogenesis18,26–28. However, combining the TyG index with measures of adiposity such as body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC) may enhance predictive accuracy29. Indeed, in our study, the composite of the TyG index with abdominal obesity indices such as WC and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) demonstrated higher odds ratios for MetS compared to the TyG index alone. Khan et al. revealed that the TyG index, with its robust area under the curve (AUC) of 0.764, outperforms other traditional markers such as fasting blood glucose, triglycerides, small dense LDL-c, non-HDL-c, and HOMA-IR in predicting MetS26. Similarly, Gui et al. demonstrated the predictive potential of various obesity- and lipid-related indices for MetS in middle-aged and older adults, with TyG-BMI and the Chinese visceral adiposity index (CVAI) emerging as the most effective markers for predicting MetS in men and women, respectively30. In a cross-sectional study, Raimi et al. assessed the utility of the TyG index in identifying MetS among Nigerians, concluding that it was effective in predicting MetS. Furthermore, combining anthropometric and TyG index indicators enhanced predictive accuracy, consistent with our findings18. Similarly, in our study, TyG-WC and TyG-WHtR exhibited the largest AUCs in both genders, with overall AUC values higher than those reported by Raimi et al. This suggests that TyG-WC and TyG-WHtR may possess greater predictive utility in our population. Both waist circumference (WC) and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) serve as markers of visceral adiposity, which correlates more strongly with cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk than BMI, a measure of overall obesity31. Notably, WHtR, corrected for height, may offer superior predictive capability compared to WC alone. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated that WHtR identifies individuals at early health risks more effectively than a composite index combining BMI and WC18,32,33. Moreover, in a study by Laurindo et al. conducted among the Brazilian population, the TyG-WC index exhibited the largest AUC (0.849) for detecting MetS using IR indices34. Differences in AUC values between studies may be attributed to differences in mean fasting plasma glucose and triglyceride levels, variation in study populations (diabetic versus non-diabetic individuals), and ethnic diversity.

Mao et al. conducted a study aiming to identify the optimal predictors and cut-off points for Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) among Chinese adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM). Their findings indicated that TyG-WC was the most effective predictor of MetS among women, while BMI emerged as the best predictor for both genders combined35. In contrast, our study revealed that TyG-WC was the superior predictor of MetS for both women and men. Another study utilizing data from the 2013–2016 US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found TyG-WC to be more robust in predicting MetS among the non-Hispanic population, though gender-specific analysis was not conducted36. Our findings demonstrated that TyG-WC outperformed TyG-BMI in MetS prediction, with TyG-WC exhibiting the largest area under the curve (AUC) and TyG-BMI the smallest. Body Mass Index (BMI) is commonly regarded as a general indicator of obesity, while waist circumference (WC) is considered a measure of central obesity37. However, the distribution of adipose tissue, particularly visceral fat, holds greater significance in metabolic dysfunction and insulin resistance. WC is closely associated with cardiometabolic risks38, highlighting its importance in predicting MetS. Moreover, in a study by Song et al., in addition to MetS, the product of the TyG index and anthropometric indices was also employed for predicting non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. TyG-WC exhibited superiority over TyG-BMI in predicting non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, further emphasizing the utility of WC as a predictor of metabolic disorders39.

In the present study, both the Waist-Triglyceride Index (WTI) and Metabolic Syndrome-Insulin Resistance (METS-IR) significantly predicted the risk of Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) in all participants, both before and after adjusting for relevant factors. Yang et al. highlighted the Waist-Triglyceride (WT) index, calculated as the product of waist circumference (WC) and triglyceride levels, as strongly associated with coronary heart disease risk40. Additionally, the WT index demonstrated effectiveness in screening for MetS in individuals with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM)41. Recently, Liu et al. introduced a modified form of the WT index, termed WTI, which exhibited a robust ability to identify MetS42. Similarly, Endukuru et al. demonstrated that WTI had the highest predictive ability for detecting low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), elevated blood pressure, and high triglyceride levels in women compared to other indices43. Several studies have also demonstrated the high predictive capacity of WTI for discriminating MetS44,45. The METS-IR was developed by Chavolla et al. to evaluate insulin sensitivity, validated against the euglycemic–hyperinsulinemic clamp. Moreover, they found that METS-IR was associated with ectopic fat accumulation and could better predict incident T2DM than the triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (TG/HDL-C) and TyG index in the Mexican population46. Han et al. investigated the association of various insulin resistance indicators, including METS-IR, TG/HDL-C, TyG-BMI, and TyG index, with serum uric acid levels in patients with T2DM, revealing significant associations between all indices and serum uric acid levels47. Furthermore, Zhang et al. demonstrated that METS-IR could predict the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events in individuals with ischemic cardiomyopathy and T2DM48. It has been reported that METS-IR is strongly associated with hypertension even in individuals with normal weight49. Pathophysiological studies have elucidated that insulin resistance can perturb the lipid metabolism of the entire body, increase cardiac lipotoxicity, and induce oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction, ultimately culminating in dyslipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease50.

Variations in the literature may stem from differences in chosen anthropometric indices, gender, ethnicity, underlying conditions, participant age, confounder variables, and criteria used to define Metabolic Syndrome (MetS), such as those by WHO, IDF, ATP III, and AHA/NHLBI. A limitation of our study is its cross-sectional design, which doesn't establish causality. Additionally, our focus on the Iranian population may limit generalizability. However, our study is the first to explore IR indices in predicting MetS risk among Iranian T2DM patients, and it includes both genders and employs multivariable logistic regression across three models.

All IR indices examined predicted MetS risk in our study, with the TyG-WC index emerging as the most effective predictor for both genders among Iranian T2DM patients.

Methods

Study design and participants

In this cross-sectional investigation, 400 Iranian patients diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) were prospectively enrolled from the Endocrine and Metabolism Clinic of Golestan Hospital, located in Ahvaz City, during the period spanning from March to May 2023. Patients were selected utilizing a convenient consecutive sampling method. Inclusion criteria comprised willingness to participate, age between 18 and 60 years, and a minimum of 2 years since the diagnosis of T2DM. Exclusion criteria consisted of insulin usage, pregnancy or lactation, smoking, alcohol consumption, incomplete demographic or anthropometric data, adherence to specialized diets, recent intake of antioxidant supplements within the last 3 months, and presence of comorbidities such as renal, hepatic, thyroidal, neoplastic, HIV, or infectious diseases.

A structured questionnaire was employed to collect demographic and baseline characteristics, encompassing sociodemographic factors such as gender, age, educational level, occupation, ethnicity, duration of diabetes, physical activity, and medication history. The study protocol adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee in Research of Sirjan University of Medical Sciences (Ethical code: IR.SIRUMS.REC.1401.017, Approval date: 18-03-2023). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before their involvement. The sample size was determined based on the study conducted by Zhang et al.51 and the utilization of the TyG-WHtR index, employing the formula (n = (z1 − a/2)2. SD2/d2) with a precision (d) of 0.05, a standard deviation (SD) of 0.45, and a confidence level of 95%, resulting in a final sample size of 400 subjects.

Definition of MetS

Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) was defined according to the criteria established by the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), which includes the presence of central obesity, defined as a waist circumference (WC) equal to or greater than 95 cm for both genders based on guidelines provided by the Iranian National Obesity Committee52, in addition to meeting two or more of the following criteria: fasting blood glucose (FBG) levels equal to or greater than 100 mg/dL, or receiving medications for hyperglycemia; triglyceride (TG) levels equal to or greater than 150 mg/dL, or receiving medications for hypertriglyceridemia; low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), defined as less than 40 mg/dL in men and less than 50 mg/dL in women, or receiving drug treatment for low HDL-C; and elevated blood pressure, indicated by systolic blood pressure (SBP) equal to or greater than 130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) equal to or greater than 85 mmHg, or receiving drug treatment for hypertension53.

Blood pressure (BP) measurement

Blood pressure (BP) measurements were taken by a trained professional following a 20-min rest period for the patients, between 8:00 and 9:00 AM. This procedure was iterated thrice consecutively, and the average of the three successive readings was utilized for analysis. The mean arterial pressure (MAP) and pulse pressure (PP) were calculated employing the following formulas54:

where SBP represents systolic blood pressure and DBP represents diastolic blood pressure, both measured in millimeters of mercury (mmHg).

Biochemical assessment

Serum levels of fasting blood glucose (FBG) with a coefficient of variation (CV) interassay of 1.2% and lipid profile parameters, including triglycerides (TG) with a CV interassay of 1.6%, total cholesterol (TC) with a CV interassay of 2%, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) with a CV interassay of 1.8%, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) with a CV interassay of 1.29%, and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), were measured following a 12-h fasting period. Blood samples of 5 cc were drawn from each participant. FBG and the lipid profile were determined utilizing the enzymatic method with Pars Azmoon kits (Tehran, Iran) and analyzed on an auto analyzer (Hitachi 902, Japan). The Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP) was calculated using the logarithm of the TG to HDL-C ratio55. Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels in whole blood were quantified via automated high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) utilizing an exchange ion method with a DS5 set (DREW, United Kingdom).

Measurement of anthropometric indices and physical activity

All anthropometric assessments were conducted by a trained professional. Weight was measured using a digital scale manufactured in Japan with a precision of 0.1 kg, with participants asked to remove their shoes and wear minimal clothing. Height was determined using a tape measure with a precision of 0.5 cm. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated using the formula: weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Waist circumference (WC) was measured at the narrowest point of the torso with a precision of 0.5 cm, while hip circumference (HC) was assessed at the most prominent part of the hip area using a tape measure56–58. Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) was computed by dividing WC by HC. Additionally, Waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) was obtained by dividing WC by height59.

Formulas for calculating novel indices of insulin resistance (IR) were applied as follows18,36:

Physical activity levels were assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), and results were reported as metabolic equivalent hours per week (METs hr/wk)60.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 23 software. The normal distribution of the data was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistical test. Quantitative variables were compared between two groups using the independent t-test, while qualitative variables were compared using the chi-square test. Differences in variables across quartiles of the Triglyceride and glucose index (TyG index) were examined using One-way ANOVA with Post hoc (Least Significant Difference, LSD) analysis. To investigate the risk of Metabolic Syndrome (MetS), logistic regression was utilized, incorporating models with both crude and adjusted effects for potential confounding factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, educational level, occupation, duration of disease, physical activity, and medication usage. The predictive capacity of anthropometric indices (TyG index, TyG-BMI, TyG-WC, TyG-WHR, TyG-WHtR, Waist circumference-triglyceride index (WTI), and Metabolic Syndrome-Insulin Resistance (METS-IR)) for MetS stratified by sex was evaluated through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, with the area under the curve (AUC) values calculated. Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 depict the results, highlighting the best predictors for both genders alongside their optimal threshold values. Quantitative data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while qualitative data are expressed as frequencies (percentages). A significance level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics declarations

The research protocol was in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee in Research of Sirjan University of Medical Sciences approved the study protocol (Ethical code: IR.SIRUMS.REC.1401.017, Approval date: 18-03-2023). The informed written consent form was acquired from all subjects at the starting of the study. For illiterate participants, informed consent was obtained from their guardian/legally authorized representative.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Endocrinology and Metabolism clinic employees of Golestan Hospital and also the laboratory staff of Golestan Hospital in Ahvaz.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under the curve

- BMI

Body mass index

- HOMA-IR

Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

- IR

Insulin resistance

- MAP

Mean arterial pressure

- MetS

Metabolic syndrome

- METS-IR

Metabolic score for insulin resistance

- PP

Pulse pressure

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TyG index

Triglyceride and glucose index

- TyG-WC

TyG-waist circumference

- TyG-BMI

TyG-body mass index

- VAI

Visceral fat index

- WC

Waist circumference

- WHtR

Waist to height ratio

- WTI

Waist circumference-triglyceride index

Author contributions

HB: all steps of research and writing the manuscript, A-ZJ: drafting of the manuscript, MR-M: drafting of the manuscript, FH: revision of the manuscript, ZH: drafting and revision of the manuscript, SH: drafting of the manuscript, VA: corresponding author, supervision and all steps of research and writing the manuscript, MV: co-corresponding and all steps of research. All authors reviewed the manuscript. The final version of the manuscript was approved by all authors.

Funding

This work has been financially supported by the Student Research Committee of Sirjan School of Medical Sciences (No: 401000024).

Data availability

All data and materials are fully presented in the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the spelling of the author Mahdi Vajdi which was incorrectly given as Mehdi Vajdi.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

5/23/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-024-62809-2

Contributor Information

Vahideh Aghamohammadi, Email: v_agamohammadi@yahoo.com.

Mahdi Vajdi, Email: mv.vajdi@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Cerf ME. Beta cell dysfunction and insulin resistance. Front. Endocrinol. 2013;4:43179. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bugianesi E, McCullough AJ, Marchesini G. Insulin resistance: A metabolic pathway to chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;42:987–1000. doi: 10.1002/hep.20920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman, A. M. & Pennings, N. Insulin resistance. (2018). [PubMed]

- 4.Hatting M, Tavares CD, Sharabi K, Rines AK, Puigserver P. Insulin regulation of gluconeogenesis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018;1411:21–35. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gast KB, Tjeerdema N, Stijnen T, Smit JW, Dekkers OM. Insulin resistance and risk of incident cardiovascular events in adults without diabetes: Meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e52036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nilsson PM, Tuomilehto J, Rydén L. The metabolic syndrome–What is it and how should it be managed? Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2019;26:33–46. doi: 10.1177/2047487319886404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xia C, et al. Lipid accumulation product is a powerful index for recognizing insulin resistance in non-diabetic individuals. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012;66:1035–1038. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeFronzo RA, Tobin JD, Andres R. Glucose clamp technique: A method for quantifying insulin secretion and resistance. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 1979;237:E214. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1979.237.3.E214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du T, et al. Clinical usefulness of lipid ratios, visceral adiposity indicators, and the triglycerides and glucose index as risk markers of insulin resistance. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2014;13:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12933-014-0146-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matthews DR, et al. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and β-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller WG, et al. Toward standardization of insulin immunoassays. Clin. Chem. 2009;55:1011–1018. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.118380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ren X, et al. Association between triglyceride to HDL-C ratio (TG/HDL-C) and insulin resistance in Chinese patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0154345. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim-Dorner S-J, Deuster PA, Zeno SA, Remaley AT, Poth M. Should triglycerides and the triglycerides to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio be used as surrogates for insulin resistance? Metabolism. 2010;59:299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerrero-Romero F, et al. The product of triglycerides and glucose, a simple measure of insulin sensitivity. Comparison with the euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;95:3347–3351. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simental-Mendía LE, Rodríguez-Morán M, Guerrero-Romero F. The product of fasting glucose and triglycerides as surrogate for identifying insulin resistance in apparently healthy subjects. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2008;6:299–304. doi: 10.1089/met.2008.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Er L-K, et al. Triglyceride glucose-body mass index is a simple and clinically useful surrogate marker for insulin resistance in nondiabetic individuals. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0149731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng S, et al. Triglyceride glucose-waist circumference, a novel and effective predictor of diabetes in first-degree relatives of type 2 diabetes patients: Cross-sectional and prospective cohort study. J. Transl. Med. 2016;14:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-1020-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raimi TH, et al. Triglyceride-glucose index and related parameters predicted metabolic syndrome in Nigerians. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2021;19:76–82. doi: 10.1089/met.2020.0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao K, et al. Association between the hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype and prediabetes in Chinese adults aged 40 years and older. J. Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2018/1031939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sam S, et al. Hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype predicts increased visceral fat in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1916–1920. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanko LB, et al. Enlarged waist combined with elevated triglycerides is a strong predictor of accelerated atherogenesis and related cardiovascular mortality in postmenopausal women. Circulation. 2005;111:1883–1890. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000161801.65408.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cardenas V, et al. Depression is associated with increased risk for metabolic syndrome in latinos with type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2017;25:646–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nsiah K, Shang VO, Boateng KA, Mensah F. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Int. J. Appl. Basic Med. Res. 2015;5:133–138. doi: 10.4103/2229-516X.157170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katsiki N, Anagnostis P, Kotsa K, Goulis DG, Mikhailidis DP. Obesity, metabolic syndrome and the risk of microvascular complications in patients with diabetes mellitus. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019;25:2051–2059. doi: 10.2174/1381612825666190708192134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee M-Y, et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and microvascular and macrovascular disease in type 2 diabetic mellitus. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2018;355:342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan SH, et al. Metabolic clustering of risk factors: Evaluation of triglyceride-glucose index (TyG index) for evaluation of insulin resistance. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2018;10:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13098-018-0376-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mirr M, Skrypnik D, Bogdański P, Owecki M. Newly proposed insulin resistance indexes called TyG-NC and TyG-NHtR show efficacy in diagnosing the metabolic syndrome. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021;44:2831–2843. doi: 10.1007/s40618-021-01608-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shin K-A. Triglyceride and glucose (TyG) index is a clinical surrogate marker for the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome. Biomed. Sci. Lett. 2017;23:348–354. doi: 10.15616/BSL.2017.23.4.348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khamseh ME, et al. Triglyceride glucose index and related parameters (triglyceride glucose-body mass index and triglyceride glucose-waist circumference) identify nonalcoholic fatty liver and liver fibrosis in individuals with overweight/obesity. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2021;19:167–173. doi: 10.1089/met.2020.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gui J, Li Y, Yuan T, Zhang L. Obesity-and lipid-related indices as a predictor of obesity metabolic syndrome in a national cohort study. Front. Public Health. 2023;11:1073824. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1073824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nalini M, et al. Comparing anthropometric indicators of visceral and general adiposity as determinants of overall and cardiovascular mortality. Arch. Iran. Med. 2019;22:301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashwell M, Gibson S. Waist-to-height ratio as an indicator of ‘early health risk’: Simpler and more predictive than using a ‘matrix’based on BMI and waist circumference. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010159. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gibson S, Ashwell M. A simple cut-off for waist-to-height ratio (0· 5) can act as an indicator for cardiometabolic risk: Recent data from adults in the Health Survey for England. Br. J. Nutr. 2020;123:681–690. doi: 10.1017/S0007114519003301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fornari Laurindo L, et al. Detection of metabolic syndrome using insulin resistance indexes: A cross-sectional observational cohort study. Endocrines. 2023;4:257–268. doi: 10.3390/endocrines4020021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mao J, Gan S, Zhou Q, Zhou H, Deng Z. Optimal anthropometric indicators and cut points for predicting metabolic syndrome in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus by gender. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2023;16:505–514. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S399275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okosun IS, Okosun B, Lyn R, Airhihenbuwa C. Surrogate indexes of insulin resistance and risk of metabolic syndrome in non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black and Mexican American. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020;14:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2019.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kissebah AH, et al. Relation of body fat distribution to metabolic complications of obesity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1982;54:254–260. doi: 10.1210/jcem-54-2-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pouliot M-C, et al. Waist circumference and abdominal sagittal diameter: best simple anthropometric indexes of abdominal visceral adipose tissue accumulation and related cardiovascular risk in men and women. Am. J. Cardiol. 1994;73:460–468. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90676-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song S, Son D-H, Baik S-J, Cho W-J, Lee Y-J. Triglyceride glucose-waist circumference (TyG-WC) is a reliable marker to predict non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Biomedicines. 2022;10:2251. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10092251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang R, Liu X, Lin Z, Zhang G. Correlation study on waist circumference-triglyceride (WT) index and coronary artery scores in patients with coronary heart disease. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015;19:113–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma C-M, et al. Three novel obese indicators perform better in monitoring management of metabolic syndrome in type 2 diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:9843. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10446-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu, P. J., Lou, H. P. & Zhu, Y. N. Screening for metabolic syndrome using an integrated continuous index consisting of waist circumference and triglyceride: A preliminary cross-sectional study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes.18, 2899–2907 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Endukuru CK, Gaur GS, Dhanalakshmi Y, Sahoo J, Vairappan B. Cut-off values and clinical efficacy of body roundness index and other novel anthropometric indices in identifying metabolic syndrome and its components among Southern-Indian adults. Diabetol. Int. 2022;13:188–200. doi: 10.1007/s13340-021-00522-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yin Q, Zheng J, Cao Y, Yan X, Zhang H. Evaluation of novel obesity and lipid-related indices as indicators for the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome and Premetabolic syndrome in Chinese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2021;2021:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2021/7172388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adejumo EN, et al. Anthropometric parameter that best predict metabolic syndrome in South west Nigeria. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2019;13:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2018.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bello-Chavolla OY, et al. METS-IR, a novel score to evaluate insulin sensitivity, is predictive of visceral adiposity and incident type 2 diabetes. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2018;178:533–544. doi: 10.1530/EJE-17-0883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Han, R., Zhang, Y. & Jiang, X. Relationship between four non-insulin-based indexes of insulin resistance and serum uric acid in patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther.9, 1461–1471 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Zhang, X. et al. Metabolic score for insulin resistance (METS-IR) predicts adverse cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes and ischemic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes.5, 1283–1295 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Liu XZ, Fan J, Pan SJ. METS-IR, a novel simple insulin resistance indexes, is associated with hypertension in normal-weight Chinese adults. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2019;21:1075–1081. doi: 10.1111/jch.13591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang W, et al. The metabolic score for insulin resistance (METS-IR) predicts cardiovascular disease and its subtypes in patients with hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. Clin. Epidemiol. 2023;15:177–189. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S395938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang X, et al. Association of metabolic syndrome with TyG index and TyG-related parameters in an urban Chinese population: A 15-year prospective study. Diabetol.Metab. Syndr. 2022;14:1. doi: 10.1186/s13098-022-00855-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 52.AZIZI, F. et al. Appropriate waist circumference cut-off points among Iranian adults: the first report of the Iranian National Committee of Obesity. (2010). [PubMed]

- 53.KG, A. International diabetes federation task force on epidemiology and prevention; hational heart, lung, and blood institute; American heart association; world heart federation; international atherosclerosis society; international association for the study of obesity: harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the international diabetes federation task force on epidemiology and prevention; national heart, lung, and blood institute; American heart association; world heart federation; international atherosclerosis society; and international association for the study of obesity. Circulation120, 1640–1645 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Bazyar H, et al. The effects of rutin supplement on blood pressure markers, some serum antioxidant enzymes, and quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus compared with placebo. Front. Nutr. 2023 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1214420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dobiasˇova, M. Vol. 50 1113–1115 (Oxford University Press, 2004).

- 56.Haidari F, Aghamohammadi V, Mohammadshahi M, Ahmadi-Angali K, Asghari-Jafarabadi M. Whey protein supplementation reducing fasting levels of anandamide and 2-AG without weight loss in pre-menopausal women with obesity on a weight-loss diet. Trials. 2020;21:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04586-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haidari F, Aghamohammadi V, Mohammadshahi M, Ahmadi-Angali K. Effect of whey protein supplementation on levels of endocannabinoids and some of metabolic risk factors in obese women on a weight-loss diet: A study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Nutr. J. 2017;16:1–5. doi: 10.1186/s12937-017-0294-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Behbahani HB, et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load, dietary insulin index, and dietary insulin load in relation to cardiometabolic risk factors among participants with atherosclerosis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nutr. 2023;9:98. doi: 10.1186/s40795-023-00755-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoo E-G. Waist-to-height ratio as a screening tool for obesity and cardiometabolic risk. Korean J. Pediatr. 2016;59:425. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2016.59.11.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aadahl M, Jørgensen T. Validation of a new self-report instrument for measuring physical activity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1196–1202. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000074446.02192.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials are fully presented in the manuscript.