Abstract

Background

Hysteroscopy is an operation in which the gynaecologist examines the uterine cavity using a small telescopic instrument (hysteroscope) inserted via the vagina and the cervix. Almost 50% of hysteroscopic complications are related to difficulty with cervical entry. Potential complications include cervical tears, creation of a false passage, perforation, bleeding, or simply difficulty in entering the internal os (between the cervix and the uterus) with the hysteroscope. These complications may possibly be reduced with adequate preparation of the cervix (cervical ripening) prior to hysteroscopy. Cervical ripening agents include oral or vaginal prostaglandin, which can be synthetic (e.g misoprostol) or natural (e.g. dinoprostone) and vaginal osmotic dilators, which can be naturally occurring (e.g. laminaria) or synthetic.

Objectives

To determine whether preoperative cervical preparation facilitates cervical dilatation and reduces the complications of operative hysteroscopy in women undergoing the procedure for any condition.

Search methods

In August 2014 we searched sources including the Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group (MDSG) Trials Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, ClinicalTrials.gov and reference lists of relevant articles. We searched for published and unpublished studies in any language.

Selection criteria

Two review authors independently selected randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of cervical ripening agents used before operative hysteroscopy in pre‐ and postmenopausal women. Cervical ripening agents could be compared to each other, placebo or no treatment.

Data collection and analysis

Data extraction and quality assessment were conducted independently by two review authors. The primary review outcomes were effectiveness of cervical dilatation (defined as the proportion of women requiring mechanical cervical dilatation) and intraoperative complications. Secondary outcomes were mean time required to dilate the cervix, preoperative pain, cervical width, abandonment of the procedure, side effects of dilating agents and duration of surgery. We calculated odds ratios (ORs) for dichotomous outcomes and mean differences (MDs) for continuous outcomes, with 95% confidence intervals ( CIs). Data were statistically pooled where appropriate. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic. The overall quality of the evidence was assessed using GRADE methods.

Main results

Nineteen RCTs with a total of 1870 participants were included. They compared misoprostol with no treatment or placebo, dinoprostone or osmotic dilators.

Misoprostol was more effective for cervical dilatation than placebo or no intervention, with fewer women requiring mechanical dilatation (OR 0.08, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.16, five RCTs, 441 participants, I2=0%, moderate quality evidence). This suggests that in a population in which 80% of women undergoing hysteroscopy require mechanical dilatation without use of preoperative ripening agents, use of misoprostol will reduce the need for mechanical dilatation to between 14% and 39%. Misoprostol was associated with fewer intraoperative complications (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.77, 12 RCTs, 901 participants, I2=0%, moderate quality evidence). This suggests that in a population in which 3% of women undergoing hysteroscopy experience intraoperative complications without use of preoperative ripening agents, use of misoprostol will reduce the risk of complications to 2% or less.

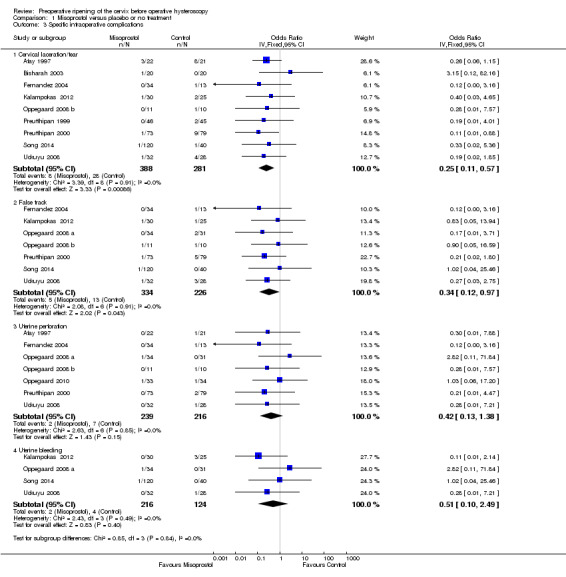

When specific complications were considered, the misoprostol group had a lower rate of cervical laceration or tearing (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.57, nine RCTS, 669 women, I2=0%, moderate quality evidence) or false track formation (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.97, seven RCTs, 560 participants, I2=0%, moderate quality evidence). There was no evidence of a difference between the groups in rates of uterine perforation (0.42, 95% CI 0.13 to 1.38, seven RCTs, 455 participants, I2=0%, low quality evidence) or uterine bleeding (OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.10 to 2.49, four RCTs, 340 participants, I2=0%, low quality evidence). Some treatment side effects (mild abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, and increased body temperature) were more common in the misoprostol group.

Compared with dinoprostone, misoprostol was associated with more effective cervical dilatation, with fewer women requiring mechanical dilatation (OR 0.58; 95% CI 0.34 to 0.98; one RCT, 310 participants, low quality evidence) and with fewer intraoperative complications (OR 0.32; 95% CI 0.12 to 0.83, one RCT, 310 participants, low quality evidence). However treatment side effects were more common in the misoprostol arm.

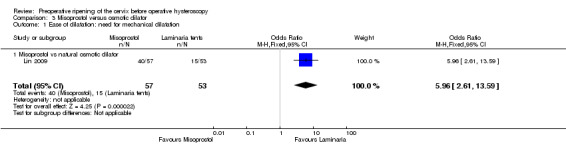

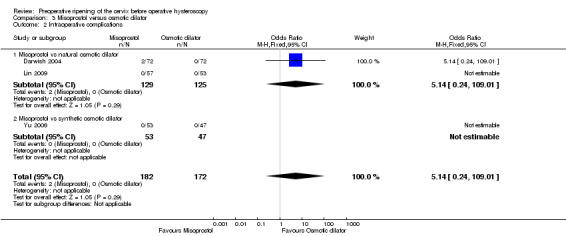

Compared to osmotic dilatation (laminaria), misoprostol was associated with less effective cervical dilatation, with more women in the misoprostol group requiring mechanical dilatation (OR 5.96, 95% CI 2.61 to 13.59, one RCT, 110 participants, low quality evidence). There was no evidence of a difference between misoprostol and osmotic dilators in intraoperative complication rates (OR 5.14, 95% CI 0.24 to 109.01, three RCTs, 354 participants, low quality evidence), with only two events reported altogether.

The overall quality of the evidence ranged from low to moderate. The main limitations in the evidence were imprecision and poor reporting of study methods.

Authors' conclusions

There is moderate quality evidence that use of misoprostol for preoperative ripening of the cervix before operative hysteroscopy is more effective than placebo or no treatment and is associated with fewer intraoperative complications such as lacerations and false tracks. However misoprostol is associated with more side effects, including preoperative pain and vaginal bleeding. There is low quality evidence to suggest that misoprostol has fewer intraoperative complications and is more effective than dinoprostone.

There is also low quality evidence to suggest that laminaria may be more effective than misoprostol, with uncertain effects for complication rates. However the possible benefits of laminaria need to be weighed against the inconvenience of its insertion and retention for one to two days.

Keywords: Female, Humans, Pregnancy, Cervical Ripening, Hysteroscopy, Hysteroscopy/adverse effects, Cervix Uteri, Cervix Uteri/drug effects, Cervix Uteri/injuries, Dilatation, Dilatation/methods, Dinoprostone, Dinoprostone/administration & dosage, Laminaria, Misoprostol, Misoprostol/administration & dosage, Oxytocics, Oxytocics/administration & dosage, Preoperative Care, Preoperative Care/methods, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Preparing the cervix with different ripening agents before operative hysteroscopy

Review question

Are cervical ripening agents effective for dilating the cervix before operative hysteroscopy and do they reduce the risk of complications during the surgery?

Background

Hysteroscopy is an operation in which the gynaecologist examines the uterine cavity using a small telescope (hysteroscope) inserted via the vagina and the cervix. Potential complications of hysteroscopy include cervical tears, formation of a false passage and uterine perforation. Cervical ripening agents are used with the aim of making it easier for the hysteroscope to pass through the cervix and reducing the risk of complications. Ripening agents include different types of prostaglandins (for example misoprostol and dinoprostone) which are administered either orally or vaginally. Osmotic agents are also used, and are administered vaginally. One osmotic agent is laminaria, a sea‐weed based product. Cochrane reviewers assessed the evidence about different ripening agents. The evidence is current to August 2014.

Study characteristics

We included 19 randomised controlled trials (1870 participants) of premenopausal and postmenopausal women undergoing hysteroscopic surgery for a variety of conditions. They compared misoprostol with placebo or no treatment, dinoprostone, and osmotic agents.

Key results

There is moderate quality evidence that misoprostol is safer and is more effective for cervical ripening than placebo or no treatment, and that is associated with fewer complications occurring during the operation, with lower rates of lacerations and false tracks. However misoprostol is associated with more side effects such as preoperative pain and vaginal bleeding.

There is low quality evidence that misoprostol may be safer and more effective than dinoprostone, and that it may be associated with fewer complications occurring during the operation. There is also low quality evidence that laminaria may be more effective than misoprostol. However, the possible benefits of laminaria need to be weighed against the inconvenience of its insertion and retention for one to two days.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence ranged from low to moderate. The main limitations in the evidence were imprecision and poor reporting of study methods. The evidence is current to August 2014.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Misoprostol compared to placebo or no treatment before operative hysteroscopy.

| Misoprostol compared to placebo or no treatment for women undergoing hysteroscopy | ||||||

| Population: Pre and post menopausal women Settings: Operative hysteroscopy Intervention: Preoperative misoprostol Comparison: Placebo or no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo or no treatment | Misoprostol | |||||

| Ease of dilatation: need for mechanical dilatation | 797 per 1000 | 239 per 1000 (136 to 386)5 to 23 per 1000 | OR 0.08 (0.04 to 0.16) | 441 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Intraoperative complications | 29 per 1000 | 11 per 1000 (5 to 23) | OR 0.37 (0.18 to 0.77) | 901 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Specific intraoperative complications ‐ Cervical laceration/tear | 25 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (3 to 14) | OR 0.25 (0.11 to 0.57) | 669 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Specific intraoperative complications ‐ False track | 40 per 1000 | 14 per 1000 (5 to 39) | OR 0.34 (0.12 to 0.97) | 560 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Specific intraoperative complications ‐ Uterine perforation | 29 per 1000 | 13 per 1000 (4 to 40) | OR 0.42 (0.13 to 1.38) | 455 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1,2 | |

| Specific intraoperative complications ‐ Uterine bleeding | 60 per 1000 | 32 per 1000 (6 to 137) | OR 0.51 (0.10 to 2.49) | 340 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1,2 | |

| Side effects | 18 per 1000 | 112 per 1000 (48 to 241) | OR 2.59 (1.15 to 5.79) | 272 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Inadequate reporting of methodology by all or most of the studies

2Imprecision: low event rates and wide confidence intervals compatible with no effect or with meaningful benefit from misoprostol

Summary of findings 2. Misoprostol compared to dinoprostone before operative hysteroscopy.

| Misoprostol compared to dinoprostone for health problem or population | ||||||

| Population: Pre and post menopausal women Settings: Operative hysteroscopy Intervention: Preoperative misoprostol Comparison: Preoperative dinoprostone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Dinoprostone | Misoprostol | |||||

| Ease of dilatation: need for mechanical dilatation | 804 per 1000 | 704 per 1000 (582 to 801) | OR 0.58 (0.34 to 0.98) |

310 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1,2 | |

| Intraoperative complications | 114 per 1000 | 40 per 1000 (15 to 96) | OR 0.32 (0.12 to 0.83) | 310 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1,2 | |

| Side effects | Total side effects not reported. Some specific side effects (abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, diarrhoea and perception of raised temperature) were more common in the misoprostol group. All side effects were mild. | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1,3 | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Inadequate description of study methods, high risk of attrition bias

2Imprecision: wide confidence intervals compatible with meaningful benefit from misoprostol or with little or no meaningful benefit

3Imprecision: wide confidence intervals compatible with harm from misoprostol or no clinically meaningful effect

Summary of findings 3. Misoprostol compared to osmotic dilator before operative hysteroscopy.

| Misoprostol compared to osmotic dilator for health problem or population | ||||||

| Population: Pre and post menopausal women Settings: Operative hysteroscopy Intervention: Preoperative misoprostol Comparison: Preoperative osmotic dilator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Osmotic dilator | Misoprostol | |||||

| Ease of dilatation: need for mechanical dilatation | 283 per 1000 | 702 per 1000 (507 to 843) | OR 5.96 (2.61 to 13.59) |

110 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1,2 | |

| Intraoperative complications | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | OR 5.14 (0.24 to 109.01) | 354 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3,4 | Only two events altogether. No events in two RCTs |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Risk of attrition bias unclear; unclear whether outcome assessment was blinded

2Imprecision: single small study with total of 55 events

3One of studies does not adequately describe methods, unclear whether outcome assessment blinded

4Imprecision: only 2 events

Background

Hysteroscopy is an operation in which the gynaecologist examines the uterine cavity using a small telescopic instrument (hysteroscope) inserted via the vagina and the cervix. Hysteroscopy allows the diagnosis and treatment of submucous fibroids, polyps, scar tissue, and uterine abnormalities. Diagnostic hysteroscopy can be done under paracervical or local anaesthesia. However, operative or therapeutic hysteroscopy is usually performed under general or spinal anaesthesia. At operative hysteroscopy uterine polyps, fibroids, adhesions, or septum can be removed and endometrial resection or ablation can be done. In order to visualize the cavity adequately, the uterine cavity should be expanded with a distending medium such as a solution of glycine.

Possible complications of hysteroscopy include uterine perforation, bleeding, infection, damage to intra‐abdominal organs, and fluid overload. In some cases fluid overload may occur, which can cause electrolytes imbalance and encephalopathy, and rarely death. The incidence of fluid overload is between 1.6% and 2.5% (Agostini A 2002a; Overton 1997). The incidence of uterine perforation is 0.014%, and infectious complications account for 0.3% to 1.6% of cases (Bradley 2002). Although rare, injury to internal organs can occur and this may require a laparotomy.

Difficulty in dilating the cervix is a complication that is infrequently discussed, despite the fact that almost 50% of hysteroscopic complications are related to difficulty with cervical entry (Bradley 2002). Potential complications include cervical tears, creation of a false passage, perforation, bleeding, or simply difficulty in entering the internal os with the hysteroscope (Bradley 2002; Cooper 1996; Loffer 1989). Adequate preparation of the cervix prior to hysteroscopy may reduce these potential complications (Bradley 2002; Ostrzenski 1994).

Description of the condition

Intrauterine pathology such as uterine polyps, fibroids, or adhesions can be treated using operative hysteroscopy. Hysteroscopic endometrial ablation or resection can also be performed by an hysteroscopic approach.

Description of the intervention

Difficulty in cervical entry and associated complications may be reduced by adequate preparation of the cervix prior to hysteroscopy. Cervical ripening agents include oral or vaginal prostaglandin, which can be synthetic (e.g. misoprostol) or natural (e.g. dinoprostone) and vaginal osmotic dilators, which can also be naturally occurring (e.g. laminaria) or synthetic.

Laminaria is made from the stem of brown sea weed (Laminaria digitata). Its dry form absorbs fluid from the cervix facilitating cervical dilatation (Ostrzenski 1994). For insertion the patient is put in the dorsal lithotomy position, a sterile Cuscos speculum is applied and the cervix is sterilized using povidone‐iodine solution. The Laminaria is removed aseptically from its package and grasped from its proximal end where the string is attached using Ring forceps. It is inserted into the cervical canal until it has passed the internal os with the string resting in the vaginal vault for easy removal (Darwish 2004). Laminaria has the disadvantage of requiring insertion and retention for one to two days.

Prostaglandin vaginal suppositories (meteno‐prost potassium or gemeprost), or intracervical sulprostone gel have been used as a cervical ripening agents before hysteroscopy (Hald 1988; Rabe 1985). Oral or vaginal misoprostol, a synthetic prostaglandin E1 analogue, has been shown to be effective in cervical ripening among both pregnant and non‐pregnant women (Nagi 1997; Oppegaard 2010; Preutthipan 2000).

How the intervention might work

Adequate preparation of the cervix prior to operative hysteroscopy may reduce the complications related to difficulty with cervical entry. Preoperative ripening agents are used to dilate the cervix before hysteroscopy.

In some cases mechanical cervical dilatation is required during surgery. In addition, preoperative use of gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist (GnRHa) will create a hypoestrogenic state (medical menopause), thin the endometrium, and facilitate visualization of the endometrial cavity (Sowter 2002). Treatment with GnRHa will also reduce the size of uterine fibroids (Girgoriadis 2012). However, similar to postmenopausal women, GnRHa treated women may have increased resistance to cervical dilatation due to the hypoestrogenic cervix (Thomas 2002a).

Why it is important to do this review

This is the first systematic review related to the research question. It is important to evaluate whether preparation of the cervix prior to operative hysteroscopy is needed and, if so, what is the best method of cervical preparation.

Objectives

To determine whether preoperative cervical preparation facilitates cervical dilatation and reduces the complications of operative hysteroscopy in women undergoing the procedure for any condition.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Quasi‐randomized trials were not included.

Types of participants

Pre‐ or postmenopausal women and women, with or without pretreatment with GnRHa, who underwent operative hysteroscopy with or without pretreatment with cervical ripening agents.

Types of interventions

Studies of different cervical ripening agents compared to placebo or no intervention were eligible for inclusion. Eligible comparisons included the following agents:

Misoprostol versus placebo or no treatment

Laminaria versus placebo or no Laminaria

Misoprostol versus Laminaria

Prostaglandin versus placebo or no prostaglandin

Prostaglandin versus Laminaria

Prostaglandin versus misoprostol

Prostaglandin versus other types of prostaglandins

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Effectiveness of cervical dilatation, defined as requirement for mechanical cervical dilatation

Intraoperative complications of the procedure including:

all complications*

cervical tears,

creation of a false passage

uterine perforation

bleeding.

* Where studies did not report "all complications" as a combined outcome and this could not be calculated from the data reported, we included uterine perforation in this analysis, with a footnote to highlight this.

Secondary outcomes

Time required to dilate the cervix to 9 mm.

Preoperative pain, as defined by the authors of each study.

Cervical width, defined as maximum size of dilator that passes the internal os without resistance

Abandonment of the procedure due to failure to dilate the cervix.

Side effects of the cervical dilating agents (including allergic reaction).

Duration of surgery.

Search methods for identification of studies

In August 2014 we searched for all published and unpublished RCTs meeting our inclusion criteria, without language restriction and in consultation with the Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group (MDSG) Trials Search Co‐ordinator. It is the intention of the review authors that a new search for RCTs will be performed every two years and the review updated accordingly. See Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5 for search strategies.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic sources:

Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group (MDSG) Trials Register

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library,

MEDLINE

EMBASE

PsycINFO

CINAHL

ClinicalTrials.gov

The Cochrane Library at http://www.cochrane.org/index.htm for the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE)

The service of the US National Institutes of Health: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home or the World Health Organization International Trials Registry Platform search portal at http://www.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx.

Conference abstracts on the ISI Web of Knowledge (http://isiwebofknowledge.com/).

Herbal or complimentary therapy protocols and reviews in the Chinese database as described in the MDSG Module.

OpenSigle for grey literature from Europe (http://opensigle.inist.fr/).

Searching other resources

We also searched the following sources.

Appropriate journals were handsearched. The list of journals is found in the MDSG Module. The Module is found at http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clabout/articles/MENSTR/frame.html (we liaised with the MDSG Trials Search Coordinator to avoid duplication of handsearching).

The reference lists of relevant systematic reviews and RCTs.

Personal contact with experts or institutions.

Conference abstracts and announcements were handsearched: European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE), American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) conferences

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently selected trials in accordance with the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data extraction and management

Three of the authors independently extracted all data using forms designed using Cochrane guidelines. The following information was extracted from the studies included in the review and presented in a table Characteristics of included studies.

Participants

Characteristics of the women included

Interventions

Type of intervention and control

Dose, timing, duration, and route of administration of the treatment

Outcomes

Outcomes reported

How outcomes were defined

How outcomes were measured

Timing of outcome measurement

If necessary, the authors of trials that met the eligibility criteria were contacted for additional information on trial methodology or actual trial data, or both. Differences of opinion were resolved by consensus.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the included studies for risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) to assess: selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment); performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel); detection bias (blinding of outcome assessors); attrition bias (incomplete outcome data); reporting bias (selective reporting); and other bias. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or by a third review author. We described all judgements fully and presented the conclusions in Risk of Bias tables.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

We used the numbers of events in the control and intervention groups of each study to calculate Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Continuous data

If all studies reported exactly the same outcomes we calculated mean differences (MDs) between treatment groups. If similar outcomes had been reported on different scales we planned to calculate the standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI.

Where a study compared multiple doses or routes of misoprostol to a control group, we analysed the data as one group regardless of the misoprostol dose or route. In accordance with statistical advice, we calculated the mean by multiplying the mean for each group by the number of women per group, adding the numbers, and then dividing by the total number of women. The same approach was used for the SDs.

Where data to calculate ORs or MDs were not available, we utilised the most detailed numerical data available to facilitate similar analyses of included studies. We compared the magnitude and direction of effect reported by studies with how they were presented in the review, taking into account legitimate differences.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis in the review was per woman randomised.

Dealing with missing data

Data were analysed on an intention‐to‐treat basis as far as possible and attempts were made to obtain missing data from the original trialists. Otherwise only the available data were analysed.

If studies reported sufficient detail to calculate MDs but gave no information on the associated standard deviation (SD), the outcome was assumed to have an SD equal to the highest SD from other studies within the same analysis.

The trial authors were contacted several times to retrieve missing data. Please see the note at the end of each included study in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table for details.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered whether the clinical and methodological characteristics of the included studies were sufficiently similar for meta‐analysis to provide a clinically meaningful summary. Heterogeneity (variation) of the results of different studies was examined by inspecting the scatter in the data points on the graph and the overlap in their CIs and, more formally, by checking the results of the Chi2 tests and the I2 statistics. An I2 value greater than 50% was taken to indicate substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2003; Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

In view of the difficulty of detecting and correcting for publication bias and other reporting biases, the authors aimed to minimise their potential impact by ensuring a comprehensive search for eligible studies and by being alert for duplication of data. If there were ten or more studies in an analysis, we planned to use a funnel plot to explore the possibility of small study effects (a tendency for estimates of the intervention effect to be more beneficial in smaller studies).

Data synthesis

If the studies were sufficiently similar we pooled the data using a fixed effect model.

We reversed the direction of effect of individual studies, if required, to ensure consistency across trials. We planned to treat ordinal data as continuous data, if appropriate.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

For primary outcomes, subgroup analyses were performed to determine the separate evidence in the following subgroups, where data were available:

premenopausal women

postmenopausal women

hypoestrogenic women (women who were pretreated with GnRHa, or who were postmenopausal)

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the effects of the following on primary study outcomes:

study quality: limiting analysis to studies which clearly reported acceptable methods of sequence generation and allocation concealment and which were not at high risk of bias in any domain

use of a random effects model

use of RR rather than OR

Overall quality of the body of evidence: Summary of Findings Table

A Summary of Findings Table was generated using GRADEPRO software. This table evaluated the overall quality of the body of evidence for main review outcomes, using GRADE criteria (study limitations (i.e. risk of bias), consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias). Judgements about evidence quality (high, moderate or low) were justified, documented, and incorporated into reporting of results for the primary outcome.

Results

Description of studies

No RCTs were found which compared the following interventions:

Laminaria versus placebo or no laminaria;

prostaglandin versus placebo or no prostaglandin (other than misoprostol);

prostaglandin versus laminaria (other than misoprostol);

prostaglandin versus other types of prostaglandins (other than misoprostol).

Comparisons included:

misoprostol versus placebo or no treatment

misoprostol versus dinoprostone (another type of prostaglandin);

misoprostol versus laminaria (natural osmotic dilator);

misoprostol versus synthetic osmotic dilators.

Results of the search

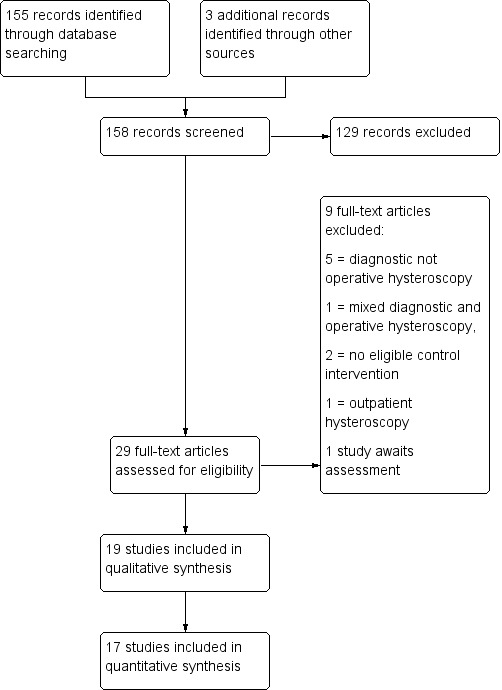

138 records were retrieved in the search, of which 29 were assessed in full text. Nineteen studies were included, nine were excluded and one awaits assessment. See Figure 1

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Study design and setting

Nineteen parallel designed randomised trials were included in the review. Two of the studies (Oppegaard 2008 a; Oppegaard 2008 b) were reported in a single trial publication, but are included separately in this review because they were run as separate trials; they include premenopausal and postmenopausal women respectively.

Participants

There were 1870 participants in total. Ten studies evaluated premenopausal women and four studies evaluated postmenopausal women. Four studies evaluated both premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Menopausal status was unclear in one study (Preen 2002). Indications for operative hysteroscopy included: uterine septae, synechiae, submucous myomas, endometrial polyps and endometrial ablation.

Interventions

1. Fifteen RCTs compared the use of misoprostol (a synthetic prostaglandin) versus placebo/no treatment

2. One RCT compared misoprostol versus dinoprostone (a natural prostaglandin)

3. Three RCTs compared misoprostol versus osmotic dilators, either synthetic or naturally occurring (laminaria)

Fernandez 2004 compared three different doses of misoprostol vaginally (200, 400 and 800 µg) to a control group. We analysed the misoprostol group data as one group regardless of the misoprostol dose, using the methods described above (see Measures of treatment effect). The final results were independent of the data from that study. Similarly, Song 2014 compared three different routes of misoprostol to a control group and the misoprostol data were analysed as one group.

Outcomes

With respect to the primary outcomes of this review, seven of the 19 studies reported need for mechanical dilatation and all 19 reported intraoperative complications. Twelve studies reported side effects but it was not always clear how many women hadany side effect. As noted above, where studies did not report "all complications" as a combined outcome and this could not be calculated from the data reported, where possible we included uterine perforation in this analysis, with a footnote to highlight this.

Two studies did not report any outcomes in a form suitable for analysis. One reported only p values (Preen 2002) and one (Thomas 2002) failed to make it clear how many women were randomised to each group or how many were analysed for each outcome. Efforts to obtain this information from the study authors were unsuccessful.

Excluded studies

Nine studies were excluded. Six were studies of diagnostic hysteroscopy, one included mixed diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy, with no distinction between the two groups, and two did not include eligible control groups.

See Characteristics of excluded studies

Study awaiting classification

One study (Chencheewachat 2012) awaits classification. It compares intravaginal isosorbide mononitrate versus placebo, in women having operative hysteroscopy.

Risk of bias in included studies

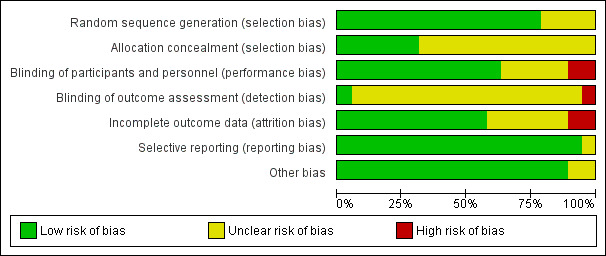

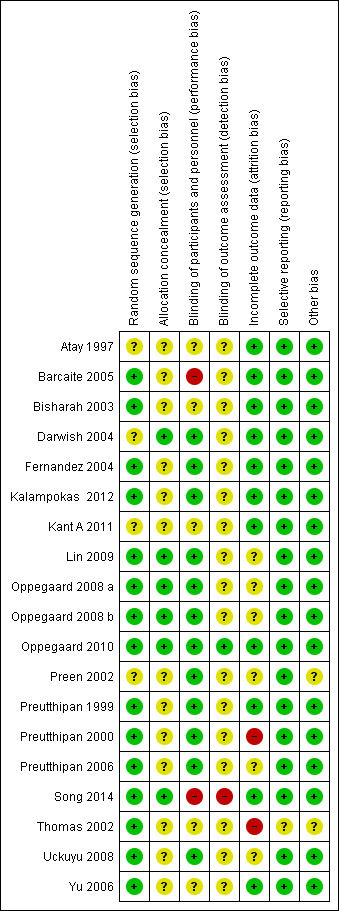

Please see the risk of bias table of the included studies in Characteristics of included studies for full details; also see Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

The methods used to generate the allocation sequence were considered adequate in 15 of the included studies, where the authors used either computer software, permuted tables, or random numbers to generate a random sequence. Accordingly, these trials were considered at low risk of bias. The methods were considered unclear in four trials where no specific method was mentioned. Overall, 15 studies were deemed to be at low risk and four studies at unclear risk of bias for random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment

A satisfactory method of allocation concealment was reported by six RCTs (Darwish 2004; Lin 2009; Oppegaard 2008 a; Oppegaard 2008 b; Oppegaard 2010; Song 2014). The rest of the RCTs were rated as unclear for allocation concealment. Overall, six studies were deemed to be at low risk and 13studies at unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment.

Blinding

Performance bias

Blinding was reported in 13 RCTs (Darwish 2004; Fernandez 2004; Kalampokas 2012; Lin 2009; Oppegaard 2008 a; Oppegaard 2008 b; Oppegaard 2010; Preen 2002; Preutthipan 1999; Preutthipan 2000; Preutthipan 2006; Uckuyu 2008; Yu 2006). Overall, 13 studies were deemed to be at low risk of bias, four studies at unclear risk, and two studies at high risk.

Detection bias

Two studies were deemed to be at low risk of detection bias (Oppegaard 2010, Thomas 2002), 16 studies at unclear risk and one (Song 2014) at high risk.

Incomplete outcome data

Eleven trials had an adequate description of follow‐up and withdrawals and were considered to be at low risk of attrition bias. One study was rated as at high risk of bias as over 10% of participants were not included in analysis (Preutthipan 2000) and one was rated as at high risk of bias because it did not clearly state how many women were randomised to each group (Thomas 2002). Six of the trials had small numbers of participants (7 to 22 women; under 10% of total participants) who were not included in the final analysis (Lin 2009; Oppegaard 2008 a; Oppegaard 2008 b; Preutthipan 2006; Uckuyu 2008) or did not clearly state how many participants were included in analysis (Preen 2002). These studies were rated as at unclear risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

All studies reported all prespecified outcomes including adverse effects, and were rated as at low risk of selective reporting.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not identify any other potential source of bias in 17 of the included studies, which were rated as at low risk of bias in this domain. Two studies which did not report any outcomes in a form suitable for analysis were rated as at unclear risk of bias in this domain (Preen 2002, Thomas 2002).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

1. Misoprostol versus placebo or no treatment

Fifteen RCTs compared misoprostol to placebo or no treatment. Nine (Atay 1997; Barcaite 2005; Bisharah 2003; Fernandez 2004; Kalampokas 2012; Oppegaard 2008 a; Preutthipan 1999; Preutthipan 2000; Song 2014; Uckuyu 2008) included premenopausal women and four (Barcaite 2005; Kant A 2011; Oppegaard 2008 b; Oppegaard 2010) included postmenopausal women. One included both, reporting results separately by menopausal status (Thomas 2002). Menopausal status was unclear in one study (Preen 2002).

Primary outcomes

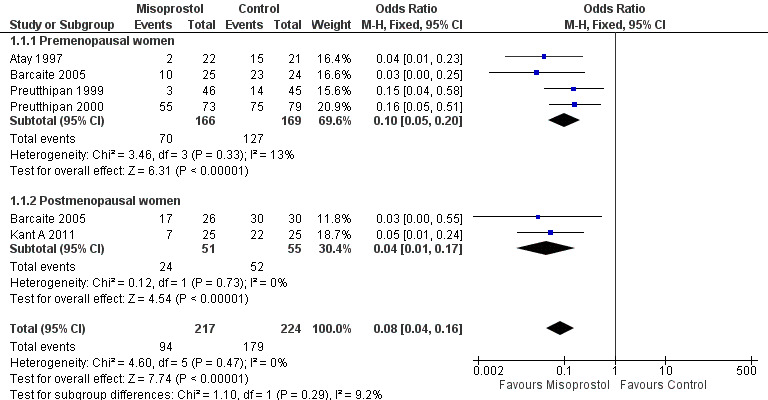

1.1 Effectiveness of cervical dilatation

Five RCTs reported effectiveness of cervical dilatation, which we defined for the purpose of this review as requirement for mechanical cervical dilatation (Atay 1997; Barcaite 2005; Kant A 2011; Preutthipan 1999; Preutthipan 2000).

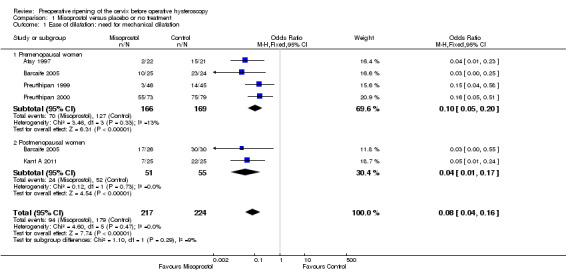

Fewer women who used misoprostol required mechanical cervical dilatation (OR 0.08; 95% CI 0.04 to 0.16; five RCTs, 441 participants, I2=0%, moderate quality evidence, Figure 4, Analysis 1.1). This suggests that in a population in which 80% of women undergoing hysteroscopy require mechanical dilatation without use of preoperative ripening agents, use of misoprostol will reduce the need for mechanical dilatation to between 14% and 37%.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Misoprostol versus placebo or no treatment, outcome: 1.1 Ease of dilatation: need for mechanical dilatation.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 1 Ease of dilatation: need for mechanical dilatation.

Subgroup analysis by menopausal status:

Four RCTs (Atay 1997; Barcaite 2005; Preutthipan 1999; Preutthipan 2000) reported relevant data on premenopausal women. Fewer women who used misoprostol required mechanical cervical dilatation (OR 0.10, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.20; four RCTs, 335 participants, I2=0%, Analysis 1.1).

Two RCTs (Barcaite 2005; Kant A 2011) reported relevant data on postmenopausal women. Fewer women who used misoprostol required mechanical cervical dilatation (OR 0.04, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.17106 participants, I2=9.2 %, Analysis 1.1)

1.2 Intraoperative complications of the procedure

All studies reported intraoperative complications.

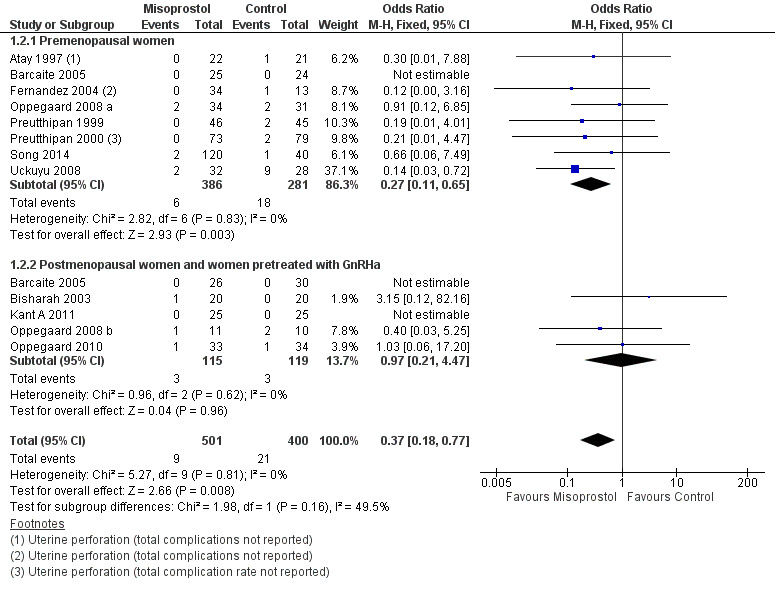

Overall, intraoperative complications were less common in the misoprostol group (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.77), 12 RCTs, 901 participants, I2=0%, moderate quality evidence, Figure 5, Analysis 1.2). This suggests that in a population in which 5% of women undergoing hysteroscopy experience intraoperative complications without use of preoperative ripening agents, use of misoprostol will reduce the risk of complications to between 1% and 4%.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Misoprostol versus placebo or no treatment, outcome: 1.2 Intraoperative complications.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 2 Intraoperative complications.

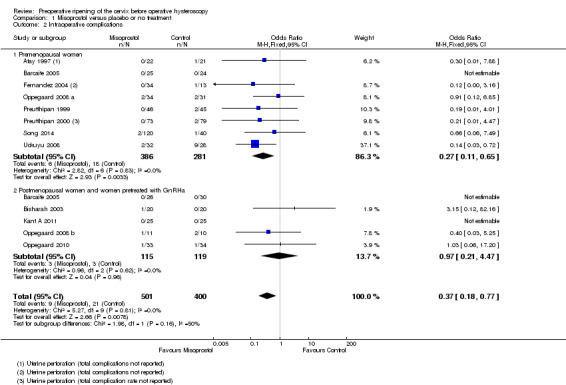

When specific types of complication were considered separately, misoprostol decreased the risk of cervical lacerations and tears (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.57, nine RCTS, 669 women, I2=0%, moderate quality evidence) and false track formation (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.97, seven RCTs, 560 participants, I2=0%, moderate quality evidence). There was no evidence of a difference between the groups in rates of uterine perforation (OR 0.42, 95% CI 0.13 to 1.38, seven RCTs, 455 participants, I2=0%, low quality evidence) or uterine bleeding (OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.10 to 2.49, four RCTs, 340 participants, I2=0%, low quality evidence). See Analysis 1.3.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 3 Specific intraoperative complications.

Preen 2002 reported one cervical laceration and one false track among the 23 women in the misoprostol group, but did not report whether there were any complications in the placebo group. Thomas 2002 reported four cervical lacerations and two perforations in each group, with no significant difference between the groups; however these data were not included in our analysis because it was unclear how many women were in each group.

Subgroup analysis by menopausal status

Eight RCTs (Atay 1997; Barcaite 2005; Fernandez 2004; Oppegaard 2008 a; Preutthipan 1999; Preutthipan 2000; Song 2014; Uckuyu 2008) reported the overall complication rate in premenopausal women. Fewer women in the misoprostol group had complications (OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.65), eight RCTs, 667 participants, I2=0%)

Five RCTs (Barcaite 2005;Bisharah 2003Kant A 2011; Oppegaard 2008 b; Oppegaard 2010) reported the overall complication rate in postmenopausal women and hypoestrogenic women( pretreated with GnRHa). Only five events occurred in these studies and there was no evidence of a difference between the groups (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.21 to 4.47) , five RCTs, 234 participants, I2=0%) Analysis 1.2

Secondary outcomes

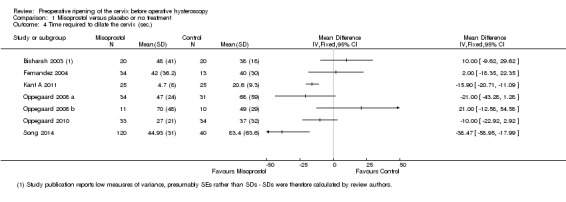

1.3 Time required to dilate the cervix to 9 mm

The time required to dilate the cervix to perform the operative hysteroscopy was reported in nine studies (Bisharah 2003; Fernandez 2004; Kant A 2011; Oppegaard 2008 a; Oppegaard 2008 b; Oppegaard 2010; Preen 2002; Song 2014; Thomas 2002), including a total of 700 women. Seven of these studies reported data suitable for analysis but they were not pooled as there was high heterogeneity (I2=69%) and differences between the studies in the direction of effect. Two studies (Kant A 2011; Song 2014) found a benefit in the misoprostol group, while the other studies found no evidence of a difference between the groups (Analysis 1.4). Two studies reported data unsuitable for analysis, but noted that there was no difference between the groups (Preen 2002: p=0.830, 46 women; Thomas 2002: p=0.18, 204 women).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 4 Time required to dilate the cervix (sec.).

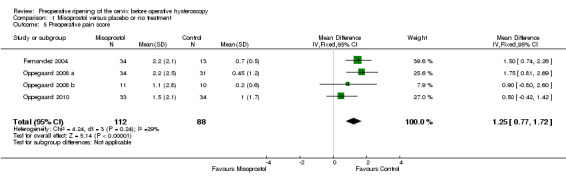

1.4 Preoperative pain

Preoperative pain scores were reported in four studies (Fernandez 2004; Oppegaard 2008 a; Oppegaard 2008 b; Oppegaard 2010). The studies used a visual analogue scale score (VAS) for pain tolerance evaluation, with a range from 0 (no pain) to 10 (unbearable pain). The pooled MD showed a difference between the two groups, favouring the placebo or no treatment group (MD 1.25; 95% CI 0.77 to 1.72; I2=29%, Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 5 Preoperative pain score.

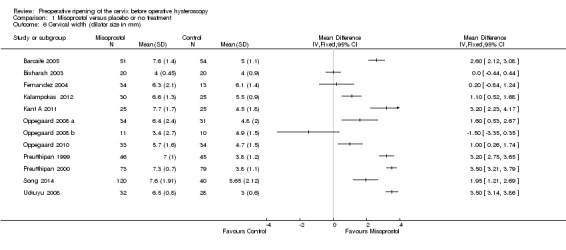

1.5 Cervical width

Cervical width, defined as the largest dilator that passes the internal os without resistance (cervical width), was reported in 12 trials with a total of 913participants (Barcaite 2005;Bisharah 2003;Fernandez 2004; Kalampokas 2012; Kant A 2011; Oppegaard 2008 a; Oppegaard 2008 b; Oppegaard 2010; Preutthipan 1999; Preutthipan 2000; Uckuyu 2008; Song 2014). The findings of these trials varied widely, with summary effects ranging from a mean difference of ‐1.5 to + 3.5 mm. The data were not pooled as this resulted in very high heterogeneity (I2=97%). However nine of the 12 individual RCTS favoured misoprostol. Analysis 1.6

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 6 Cervical width (dilator size in mm).

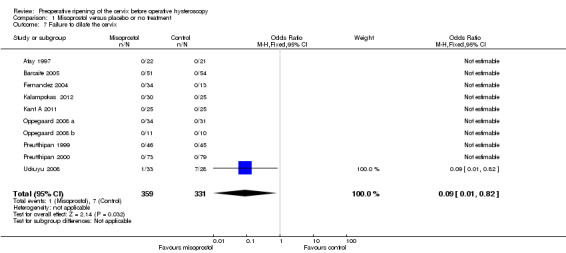

1.6 Abandonment of the procedure due to failure to dilate the cervix

Failure to dilate the cervix was reported in 10 RCTs (Atay 1997; Barcaite 2005; Fernandez 2004; Kalampokas 2012; Kant A 2011; Oppegaard 2008 a; Oppegaard 2008 b; Preutthipan 2000 ; Preutthipan 1999; Uckuyu 2008).

In nine studies there were no events in either group. In one study (Uckuyu 2008) failure to dilate the cervix was reported in 1/32 (3%) in the misoprostol group and 7/28 (25%) in the placebo group (OR 0.09, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.82). Analysis 1.7

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 7 Failure to dilate the cervix.

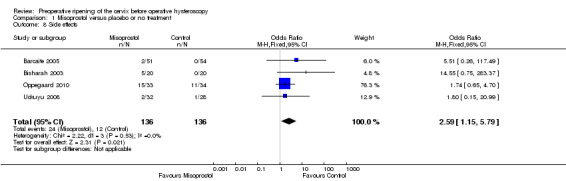

1.7 Side effects

The number of women who had side effects was reported in seven RCTs (Barcaite 2005; Bisharah 2003; Oppegaard 2010; Preen 2002; Song 2014; Thomas 2002; Uckuyu 2008).

When side effects were considered overall, they were more common in the misoprostol group (OR 2.59; 95% CI 1.15 to 5.79; four RCTs, 272 women, I2=0%, Analysis 1.8); 24/136 (19%) in the misoprostol group and 12/136 (9%) of the control group experienced side effects.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 8 Side effects.

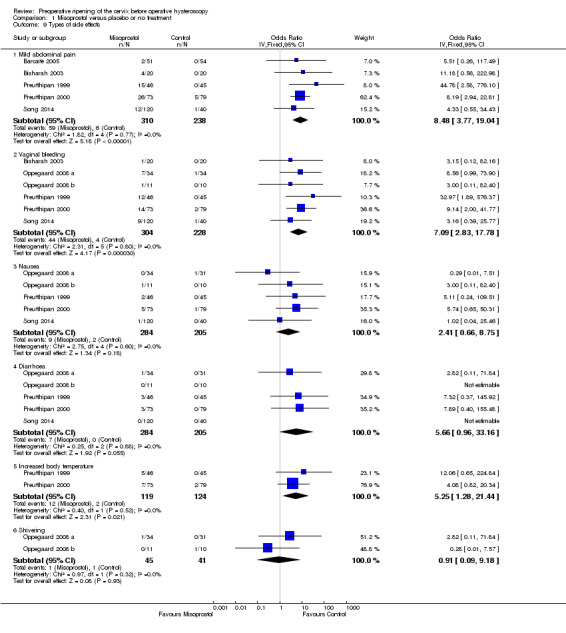

When specific side effects were considered, compared to placebo misoprostol was associated with a higher incidence of mild abdominal pain (OR 8.48, 95% CI 3.77 to 19.04, fiveRCTs, 548 participants, I2=0%), vaginal bleeding (OR 7.09, 95% CI 2.83 to 17.78, six RCTs, 532 participants, I2=0%), and increased body temperature (OR 5.25, 95% CI 1.28 to 21.44, two RCTs, 243 participants, I2=0%). There was no conclusive evidence of a difference between the groups in rates of nausea (OR 2.41, 95% CI 0.66 to 8.75, five RCTs, 489 participants, I2=0%), diarrhoea (OR 5.66, 95% CI 0.96 to 33.16, five RCTs, 489participants, I2=0%) or shivering (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.09 to 9.18, two RCTs 86 participants, I2=0%). See Analysis 1.9.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 9 Types of side effects.

Preen 2002 did not report data suitable for analysis, but noted that there was no evidence of a difference between the groups in postoperative pain rating (p=0.880, 46 women) and that rates of discomfort and overall side effects appeared to be similar in both groups.

Thomas 2002 reported higher rates of overall side‐effects, abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding in the misoprostol group (all p<0.0001), and no significant difference in rates of nausea (p<0.07). These data were not included in our analysis because it was unclear how many women were in each group.

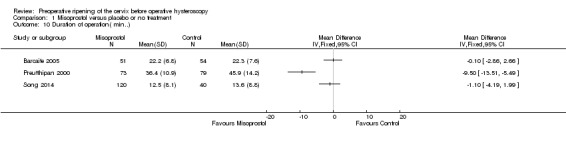

1.8 Duration of surgery.

Duration of surgery was reported in four RCTs, which included a total of 463 participants (Barcaite 2005; Preen 2002; Song 2014; Preutthipan 2000 ). Findings were inconsistent. Two studies found no difference between the groups, while the other reported that the duration of surgery was shorter in the misoprostol group. Three of these studies reported data suitable for analysis but they were not pooled due to high heterogeneity I2=93%). The fourth study (Preen 2002, n=46) failed to report data suitable for analysis.See Analysis 1.10.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 10 Duration of operation( min..).

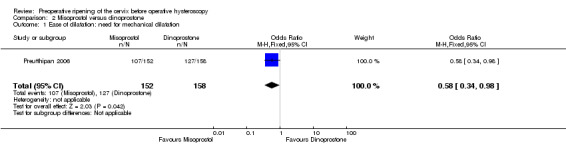

2. Misoprostol versus dinoprostone

A single RCT (Preutthipan 2006) compared misoprostol to dinoprostone (another prostaglandin).

Primary outcomes

2.1 Effectiveness of cervical dilatation

Misoprostol decreased the number of women requiring mechanical cervical dilation, compared to dinoprostone (OR 0.58; 95% CI 0.34 to 0.98; one RCT, 310 participants, low quality evidence, Figure 6, Analysis 2.1); 107/152 (70%) of the women in the misoprostol arm required cervical dilation versus 127/158 (80%) in the dinoprostone arm.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus dinoprostone, Outcome 1 Ease of dilatation: need for mechanical dilatation.

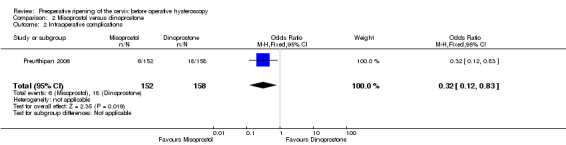

2.2 Intraoperative complications

Misoprostol was associated with fewer intraoperative complications than dinoprostone (OR 0.32; 95% CI 0.12 to 0.83, one RCT, 310 participants, low quality evidence, Analysis 2.2). A total of 6/152 (4%) of the women in the misoprostol arm had intraoperative complications versus 18/158 (11%) in the dinoprostone arm.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus dinoprostone, Outcome 2 Intraoperative complications.

Secondary outcomes

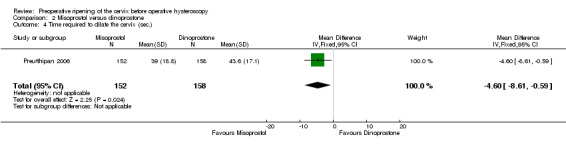

2.3 Time required to dilate the cervix to 9 mm

The time required to dilate the cervix was shorter in the misoprostol group (MD ‐4.60 seconds; 95% CI ‐8.61 to ‐0.59, one RCT, 310 participants, Analysis 2.4). Women in the misoprostol arm required 39 ± 18.8 seconds to dilate the cervix versus 43.6 ± 17.1 seconds in the dinoprostone arm.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus dinoprostone, Outcome 4 Time required to dilate the cervix (sec.).

2.4 Pain

This outcome was not reported.

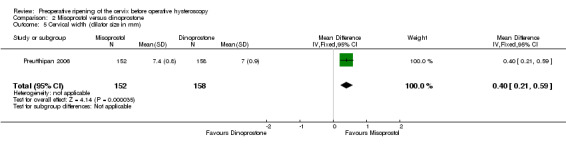

2.5 Cervical width

The mean cervical width was greater in women who used preoperative misoprostol than in those using dinoprostone (MD 0.40 mm; 95% CI 0.21 to 0.59, one RCT, 310 participants, Analysis 2.5).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus dinoprostone, Outcome 5 Cervical width (dilator size in mm).

2.6 Abandonment of the procedure due to failure to dilate the cervix

This outcome was not reported

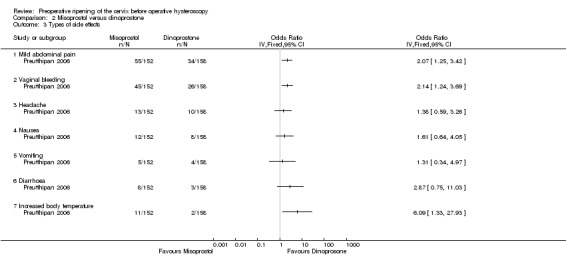

2.7 Side effects of the cervical dilating agents

The total number of women experiencing any side effect was not reported.

With regard to specific complications, women in the misoprostol group had a higher incidence of abdominal pain (OR 2.07, 95% CI 1.25 to 3.42), vaginal bleeding (OR 2.14, 95% CI 1.24 to 3.69) and perception of increased body temperature (OR 6.09, 95% CI 1.33 to 27.93). There was no evidence of a difference between the groups in the incidence of headache (OR 1.38, 95% CI 0.59 to 3.26), nausea (OR 1.61 95% CI 0.64 to 4.05), vomiting (OR 1.31, 95% CI 0.34 to 4.97) or diarrhoea (OR 2.87, 95% CI 0.75 to 11.03) Analysis 2.3. All side effects were mild.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus dinoprostone, Outcome 3 Types of side effects.

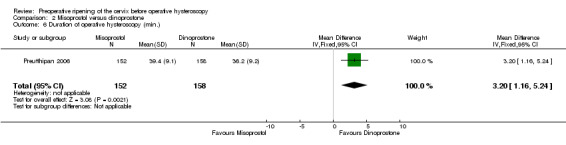

2.8 Duration of surgery.

The duration of surgery was longer in the misoprostol group (MD 3.20 minutes; 95% CI 1.16 to 5.24, one RCT, 310 participants, Analysis 2.6). The duration of operative hysteroscopy in women using misoprostol was 39.4 ± 9.1 minutes versus 36.2 ± 9.2 minutes in women using dinoprostone.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus dinoprostone, Outcome 6 Duration of operative hysteroscopy (min.).

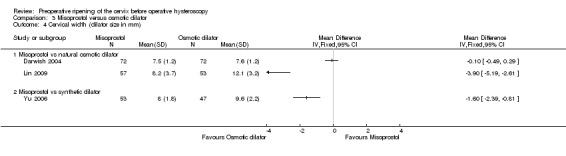

3. Misoprostol versus osmotic dilators (natural and synthetic)

Three RCTs (Darwish 2004,Lin 2009,Yu 2006) compared misoprostol to osmotic dilators. Two of them (Darwish 2004; Lin 2009) compared misoprostol to a natural osmotic dilator (Laminaria), while the remaining RCT (Yu 2006) compared misoprostol to a synthetic osmotic dilator.

Primary outcomes

3.1 Effectiveness of cervical dilatation

Only Darwish 2004, which compared misoprostol to laminaria, reported this outcome. Women in the misoprostol group were more likely to require mechanical dilatation (OR 5.96, 95% CI 2.61 to 13.59, one RCT, 110 participants, low quality evidence, Figure 7, Analysis 3.1). Cervical dilatation was required by 15/53 (43%) women using laminaria and by 40/57 (70%) of those using misoprostol.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Misoprostol versus osmotic dilator, Outcome 1 Ease of dilatation: need for mechanical dilatation.

3.2 Intraoperative complications of the procedure

All three studies (Darwish 2004,Lin 2009,Yu 2006) reported on intraoperative complications. None of the women in either Lin 2009 or Yu 2006 had any intraoperative complications, while in Darwish 2004 two women in the misoprostol group had intraoperative complications; there was no evidence of a difference between the groups (OR 5.14, 95% CI 0.24 to 109.01, one RCT, 310 participants, Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Misoprostol versus osmotic dilator, Outcome 2 Intraoperative complications.

Secondary outcomes

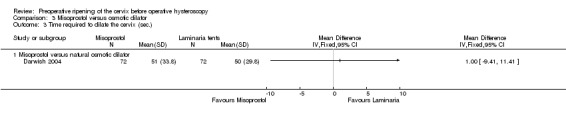

3.3 Time required to dilate the cervix to 9 mm

Only Darwish 2004, which compared misoprostol to laminaria, reported on cervical dilation time. There was no evidence of a difference between the groups (OR 1.00 second, 95% CI ‐9.41 to 11.41, one RCT, 310 participants, Analysis 3.3).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Misoprostol versus osmotic dilator, Outcome 3 Time required to dilate the cervix (sec.).

3.4 Pain

This outcome was not reported.

3.5 Cervical width

All three studies (Darwish 2004,Lin 2009,Yu 2006) reported on cervical width. They included 354 participants.

Findings were inconsistent, and these studies were not pooled due to very high heterogeneity (I2=95%). Two studies Lin 2009,Yu 2006) reported a benefit for osmotic dilators, while the third Darwish 2004 found no evidence of a difference between the groups. (Analysis 3.4)

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Misoprostol versus osmotic dilator, Outcome 4 Cervical width (dilator size in mm).

3.6 Abandonment of the procedure due to failure to dilate the cervix

This outcome was not reported.

3.7 Side effects of the cervical dilating agents

This outcome was not reported.

3.8 Duration of surgery.

This outcome was not reported.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

There were insufficient data to conduct our planned subgroup analysis of hypoestrogenic women. Other subgroup analyses are reported above.

Sensitivity analysis by quality

Only three studies (Darwish 2004; Oppegaard 2008 b; Oppegaard 2010) met our criteria for lower risk of bias (i.e. clear reporting of acceptable methods of sequence generation and allocation concealment and not at high risk of bias in any domain).This sensitivity analysis did not substantially affect our findings for primary outcomes, except that there was no difference in complication rate between misoprostol and placebo or no treatment, when analysis was restricted to studies at lower risk of bias.

Sensitivity analysis by choice of statistical model

Use of a random effects model did not substantially affect our findings for primary outcomes.

Sensitivity analysis by choice of effect estimate

Use of risk ratios did not substantially affect our findings for primary outcomes.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was fairly low or absent for our primary outcomes (0% to 33%). However there was high heterogeneity (69% to 97%) for several continuous outcomes, for which there was no clear explanation. Data for these outcomes were not pooled.

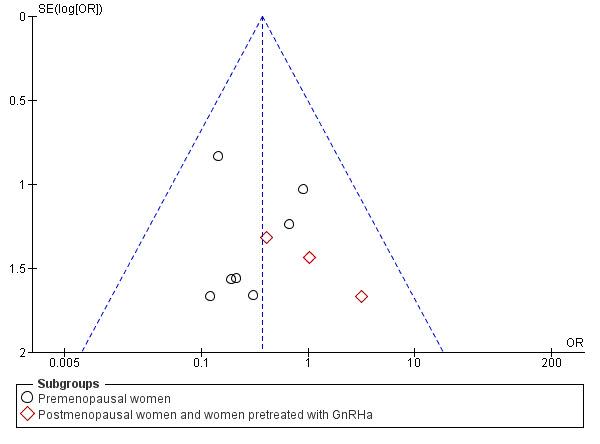

Assessment of publication bias

A funnel plot was constructed for the analysis of intraoperative complications in the comparison of misoprostol versus placebo or no treatment. There was no strong suggestion of publication bias. See Figure 6.

6.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Misoprostol versus placebo or no treatment, outcome: 1.2 Intraoperative complications.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Misoprostol, a prostaglandin E1 analogue, was superior to placebo in facilitating cervical dilatation, with fewer women requiring mechanical dilatation. It was also less likely to cause intraoperative complications. With regard to specific complications, cervical lacerations and false tracks were less common in the misoprostol group. There were too few data on uterine perforation or uterine bleeding to show whether there is any difference between the groups for these outcomes. Findings on cervical width were too heterogeneous to pool, but most studies reported a shorter time in the misoprostol group. Some side effects (preoperative pain, mild abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, and increased body temperature) were more common in the misoprostol group. Findings on time to dilate the cervix and duration of surgery were inconclusive. In most studies abandonment of the procedure did not occur in either group.

Only one study compared misoprostol with dinoprostone. The findings favoured misoprostol for effectiveness of dilatation, risk of intraoperative complications, cervical width and time required to dilate the cervix. However the duration of surgery was about 3 minutes longer and side effects were more common in the misoprostol arm. Our other review outcomes were not reported in this study.

Misoprostol was compared with osmotic dilators, either natural (laminaria) or synthetic. Only one study reported effectiveness of dilatation (defined as need for mechanical dilatation). It found that women in the misoprostol group were more likely to require mechanical dilatation than women in the laminaria group. There was no evidence of a difference between the groups in the rate of intraoperative complications or time taken to dilate the cervix, and findings for cervical width were inconsistent. Other review outcomes were not reported. Clinicians would need to balance the possible benefit of laminaria for cervical dilation and the inconvenience of its insertion and retention for one to two days.

In summary, this review suggests that misoprostol (a synthetic prostaglandin) is preferable to placebo for cervical ripening before operative hysteroscopy. It facilitates cervical dilation and decreases the risk of cervical tears and the formation of a false passage. However, it is associated with treatment side effects including mild abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhoea, and vaginal bleeding. Osmotic dilators are an option for women with contraindications to prostaglandins.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Seven of the 19 included studies reported our primary effectiveness outcome (effectiveness of cervical dilatation), though some of our secondary measures of effectiveness were limited by heterogeneity between the studies which precluded statistical pooling. All studies reported our primary safety outcome (intraoperative complications) and most studies reported on side effects associated with treatment.

The evidence appears to be applicable to women undergoing operative hysteroscopy for any condition, as the indications for operative hysteroscopy in the included studies included: uterine septae, synechiae, submucous myomas, endometrial polyps and endometrial ablation. More evidence is needed on variables such as the specific doses, intervals, and routes of administration used for these agents.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of evidence for comparisons in this review varied from low to moderate. The main limitations in the evidence were imprecision, poor reporting of study methods and statistical heterogeneity which precluded statistical pooling for most of the continuous outcomes. Two of the studies failed to provide data suitable for analysis.

Potential biases in the review process

We conducted this systematic review according to a protocol developed following the recommendations of The Cochrane Collaboration; the protocol was published before conducting the full review. We systematically searched a number of databases and reference lists for randomised clinical trials, which should have reduced the selection bias to a minimum. Two authors selected trials and extracted data in duplicate, independent of each other. We conducted analyses according to the different interventions.

Where a study compared multiple doses or routes of misoprostol to a control group, we analysed the data as one group regardless of the misoprostol dose or route. In accordance with statistical advice, we calculated the mean by multiplying the mean for each group by the number of women per group, adding the numbers, and then dividing by the total number of women. The same approach was used for the SDs. We acknowledge that this approach provides an estimate only, as there is will be no way to obtain the accurate data.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Our review is generally in agreement with other systematic reviews.

Gkrozou F 2011 in their systematic review evaluated the use of vaginal misoprostol before diagnostic or operative hysteroscopy. Misoprostol reduced the need for cervical dilatation in the total population of pre‐ and postmenopausal women. In the subgroup of operative hysteroscopy the need for dilatation and the duration of the procedure were also reduced. Side effects occurred more frequently in the misoprostol group than in the placebo group.

Polyzos 2012 reported in his systematic review on the use of misoprostol prior to hysteroscopy (diagnostic or operative) that misoprostol appears to facilitate an easier and uncomplicated procedure in premenopausal women but not postmenopausal women.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is moderate quality evidence that use of misoprostol for preoperative ripening of the cervix before operative hysteroscopy is more effective than placebo or no treatment and is associated with fewer intraoperative complications such as lacerations and false tracks. However misoprostol is associated with more side effects, including preoperative pain and vaginal bleeding.

There is low quality evidence to suggest that misoprostol has fewer intraoperative complications and is more effective than dinoprostone.

There is low quality evidence to suggest that laminaria may be more effective than misoprostol, with uncertain effects for complication rates. However the possible benefits of laminaria need to be weighed against the inconvenience of its insertion and retention for one to two days.

Clinicians should inform women of the common side effects of misoprostol, including mild abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding, and provide them with appropriate preoperative analgesia.

Implications for research.

Further research is needed on the optimal dose and interval of misoprostol, route of administration, patient satisfaction, and adverse effects. Studies should be stratified by menopausal status. Only large randomised trials will have the power to detect clinically important and patient‐oriented outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the women and investigators who were involved in the clinical trials mentioned in this review. We thank the staff of the Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group Editorial Team for their contribution and excellent collaboration. We appreciate the support of the National and Gulf Center for Evidence Health Care Practice (NGCEBHP). We acknowledge the advice of statisticians M. Hassan Murad, MD, MPH and Zhen Wang, PhD (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA) for advice on combining the intervention groups in Fernandez 2004.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MDSG search string

MDSG search string HAF1151 02.04.09

Keywords CONTAINS "hysteroscopy" or "hysteroscopy pain" or "hysteroscopy pain ‐surgical" or "hysteroscopy, techniques" or "hysterscope " or "office hysteroscopy" or "operative hysteroscopy" or Title CONTAINS "hysteroscopy" or "hysteroscopy pain" or "hysteroscopy pain ‐surgical" or "hysteroscopy, techniques" or "hysterscope " or "office hysteroscopy" or "operative hysteroscopy"

AND

Keywords CONTAINS "cervical dilatation" or "cervical priming" or "cervical relaxation" or "cervical ripening" or "Laminaria" or "misoprostol" or "Prostaglandin*" or "dilation of cervix" or "priming" or Title CONTAINS "cervical dilatation" or "cervical priming" or "cervical relaxation" or "cervical ripening" or "Laminaria" or "misoprostol" or "Prostaglandin*" or "dilation of cervix" or "priming"

Appendix 2. CENTRAL search

Database: EBM Reviews ‐ Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials inception to August 2014 1 exp hysteroscopy/ (265) 2 hysteroscop$.tw. (485) 3 or/1‐2 (511) 4 exp Cervical Ripening/ (238) 5 (Cervi$ adj3 Ripe$).tw. (776) 6 (cervi$ adj3 prim$).tw. (321) 7 (cervi$ adj3 dilat$).tw. (736) 8 (cervi$ adj3 soften$).tw. (71) 9 exp Misoprostol/ (1003) 10 Misoprostol.tw. (1665) 11 exp Laminaria/ (50) 12 laminaria.tw. (90) 13 (Dilateria or Kombu).tw. (0) 14 exp Prostaglandins/ (4450) 15 Prostaglandin$.tw. (4678) 16 (cervi$ adj3 agent$).tw. (127) 17 or/4‐16 (8228) 18 3 and 17 (71) 19 randomized controlled trial.pt. (347677) 20 controlled clinical trial.pt. (84452) 21 randomized.ab. (197013) 22 placebo.tw. (131772) 23 clinical trials as topic.sh. (33055) 24 randomly.ab. (101373) 25 trial.ti. (121577) 26 (crossover or cross‐over or cross over).tw. (45909) 27 or/19‐26 (547268) 28 exp animals/ not humans.sh. (4) 29 27 not 28 (547267) 30 18 and 29 (65)

Appendix 3. MEDLINE search

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to August 2014> 1 exp hysteroscopy/ (3594) 2 hysteroscop$.tw. (4827) 3 or/1‐2 (5615) 4 exp Cervical Ripening/ (790) 5 (Cervi$ adj3 Ripe$).tw. (1565) 6 (cervi$ adj3 prim$).tw. (2399) 7 (cervi$ adj3 dilat$).tw. (2983) 8 (cervi$ adj3 soften$).tw. (214) 9 exp Misoprostol/ (3363) 10 Misoprostol.tw. (3765) 11 exp Laminaria/ (483) 12 laminaria.tw. (855) 13 (Dilateria or Kombu).tw. (26) 14 exp Prostaglandins/ (93501) 15 Prostaglandin$.tw. (88398) 16 (cervi$ adj3 agent$).tw. (592) 17 or/4‐16 (129044) 18 3 and 17 (232) 19 randomized controlled trial.pt. (386058) 20 controlled clinical trial.pt. (89678) 21 randomized.ab. (306238) 22 placebo.tw. (163050) 23 clinical trials as topic.sh. (172069) 24 randomly.ab. (220457) 25 trial.ti. (132096) 26 (crossover or cross‐over or cross over).tw. (62294) 27 or/19‐26 (951578) 28 exp animals/ not humans.sh. (3996345) 29 27 not 28 (877040) 30 18 and 29 (77)

Appendix 4. EMBASE search

Database: Embase <1980 to 2014 Week 33> 1 exp hysteroscopy/ (7727) 2 hysteroscop$.tw. (7507) 3 or/1‐2 (9336) 4 (Cervi$ adj3 Ripe$).tw. (1906) 5 (cervi$ adj3 prim$).tw. (2868) 6 (cervi$ adj3 dilat$).tw. (3327) 7 (cervi$ adj3 soften$).tw. (204) 8 exp Misoprostol/ (9167) 9 Misoprostol.tw. (4878) 10 exp Laminaria/ (664) 11 laminaria.tw. (828) 12 (Dilateria or Kombu).tw. (34) 13 Prostaglandin$.tw. (90598) 14 (cervi$ adj3 agent$).tw. (713) 15 exp uterine cervix ripening/ (1818) 16 exp Prostaglandin/ (121209) 17 or/4‐16 (150343) 18 3 and 17 (419) 19 Clinical Trial/ (833175) 20 Randomized Controlled Trial/ (347685) 21 exp randomization/ (62979) 22 Single Blind Procedure/ (18684) 23 Double Blind Procedure/ (114887) 24 Crossover Procedure/ (39813) 25 Placebo/ (244133) 26 Randomi?ed controlled trial$.tw. (101777) 27 Rct.tw. (14473) 28 random allocation.tw. (1324) 29 randomly allocated.tw. (20543) 30 allocated randomly.tw. (1939) 31 (allocated adj2 random).tw. (715) 32 Single blind$.tw. (14487) 33 Double blind$.tw. (142389) 34 ((treble or triple) adj blind$).tw. (379) 35 placebo$.tw. (200386) 36 prospective study/ (258597) 37 or/19‐36 (1375448) 38 case study/ (27309) 39 case report.tw. (261663) 40 abstract report/ or letter/ (898356) 41 or/38‐40 (1181592) 42 37 not 41 (1337586) 43 42 and 18 (133)

Appendix 5. PsycINFO search

Database: PsycINFO 1 hysteroscop$.tw. (9) 2 (Cervi$ adj3 Ripe$).tw. (4) 3 (cervi$ adj3 prim$).tw. (36) 4 (cervi$ adj3 dilat$).tw. (37) 5 (cervi$ adj3 soften$).tw. (1) 6 Misoprostol.tw. (45) 7 Laminaria.tw. (3) 8 (Dilateria or Kombu).tw. (0) 9 exp Prostaglandins/ (518) 10 Prostaglandin$.tw. (1156) 11 (cervi$ adj3 agent$).tw. (4) 12 or/2‐11 (1300) 13 1 and 12 (0)

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Misoprostol versus placebo or no treatment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Ease of dilatation: need for mechanical dilatation | 5 | 441 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.08 [0.04, 0.16] |

| 1.1 Premenopausal women | 4 | 335 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.10 [0.05, 0.20] |

| 1.2 Postmenopausal women | 2 | 106 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.04 [0.01, 0.17] |

| 2 Intraoperative complications | 12 | 901 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.37 [0.18, 0.77] |

| 2.1 Premenopausal women | 8 | 667 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.27 [0.11, 0.65] |

| 2.2 Postmenopausal women and women pretreated with GnRHa | 5 | 234 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.21, 4.47] |

| 3 Specific intraoperative complications | 11 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Cervical laceration/tear | 9 | 669 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.11, 0.57] |

| 3.2 False track | 7 | 560 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.12, 0.97] |

| 3.3 Uterine perforation | 7 | 455 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.13, 1.38] |

| 3.4 Uterine bleeding | 4 | 340 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.10, 2.49] |

| 4 Time required to dilate the cervix (sec.) | 7 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5 Preoperative pain score | 4 | 200 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.77, 1.72] |

| 6 Cervical width (dilator size in mm) | 12 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 7 Failure to dilate the cervix | 10 | 690 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.09 [0.01, 0.82] |

| 8 Side effects | 4 | 272 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.59 [1.15, 5.79] |

| 9 Types of side effects | 7 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 9.1 Mild abdominal pain | 5 | 548 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 8.48 [3.77, 19.04] |

| 9.2 Vaginal bleeding | 6 | 532 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.09 [2.83, 17.78] |

| 9.3 Nausea | 5 | 489 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.41 [0.66, 8.75] |

| 9.4 Diarrhoea | 5 | 489 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.66 [0.96, 33.16] |

| 9.5 Increased body temperature | 2 | 243 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.25 [1.28, 21.44] |

| 9.6 Shivering | 2 | 86 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.09, 9.18] |

| 10 Duration of operation( min..) | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Comparison 2. Misoprostol versus dinoprostone.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Ease of dilatation: need for mechanical dilatation | 1 | 310 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.34, 0.98] |

| 2 Intraoperative complications | 1 | 310 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.12, 0.83] |

| 3 Types of side effects | 1 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Mild abdominal pain | 1 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 Vaginal bleeding | 1 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.3 Headache | 1 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.4 Nausea | 1 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.5 Vomiting | 1 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.6 Diarrhoea | 1 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.7 Increased body temperature | 1 | Odds Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Time required to dilate the cervix (sec.) | 1 | 310 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐4.60 [‐8.61, ‐0.59] |

| 5 Cervical width (dilator size in mm) | 1 | 310 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.21, 0.59] |

| 6 Duration of operative hysteroscopy (min.) | 1 | 310 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.20 [1.16, 5.24] |

Comparison 3. Misoprostol versus osmotic dilator.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Ease of dilatation: need for mechanical dilatation | 1 | 110 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.96 [2.61, 13.59] |

| 1.1 Misoprostol vs natural osmotic dilator | 1 | 110 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.96 [2.61, 13.59] |

| 2 Intraoperative complications | 3 | 354 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.14 [0.24, 109.01] |

| 2.1 Misoprostol vs natural osmotic dilator | 2 | 254 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.14 [0.24, 109.01] |

| 2.2 Misoprostol vs synthetic osmotic dilator | 1 | 100 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Time required to dilate the cervix (sec.) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Misoprostol versus natural osmotic dilator | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Cervical width (dilator size in mm) | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 Misoprostol vs natural osmotic dilator | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 Misoprostol vs synthetic dilator | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Atay 1997.

| Methods | Randomized, placebo‐controlled clinical trial | |

| Participants | Patients undergoing hysteroscopy, for simultaneous diagnostic and operative indications such as uterine septae, synechiae, submucous myomas, endometrial polyps and lost intrauterine devices, were included into the study. They studied a total of 43 women scheduled for hysteroscopy at Guhane school of medicine Ankara, Turkey | |

| Interventions | 43 patients undergoing hysteroscopy as an operative office procedure were randomised to misoprostol (n = 22) or placebo (n = 21) groups. Indications for hysteroscopy were similar in both groups and included: uterine septae, synechiae, submucous myomas, endometrial polyps and removal of intrauterine devices. In the misoprostol group, the number of patients having undergone previous delivery was nine (41%) and it was eight (38%) in the placebo group. The median age for misoprostol group was 26.2 years with range of(17‐36), while in placebo group was 27.1 years with range of (18‐38). Misoprostol 400 mcg, was administered to the posterior fornix 4 h before hysteroscopic intervention. The same protocol was performed for the placebo (control) group. A pain score was provided by using a comparison with the patients worst menstrual pain. The patient was asked to score the pain of dilatation, noted that the worst menstrual pain was scored 10, moderate pain as 5, and no pain as zero. |

|

| Outcomes | Dilatation time, pain score, cervical bleeding and laceration, and uterine perforation. | |

| Notes | The procedure was done as an office hysteroscopy, but Intravenous analgesia was used in addition to cervical block which possible in case of operative procedure. For operative hysteroscopy in this study, the 7 mm operative hysteroscopic sheath was used.The cervix was dilated to 7‐8 mm in all patients even if it was started as diagnostic. Author contacted for: Method of randomisation, Method of treatment allocation, Was blinding used, and if so who was blinded, intention‐to‐treat analysis, Power Calculation, Source of funding, Declaration of interest, mean +/‐ SD ( or cervical width, dilation time, and operation time), and no.of women who had chills as a side effect, with no response. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No description of method of randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 43 women were included in the study and all were included in the analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported, including complications |

| Other bias | Low risk | no other sources of bias can be identified |

Barcaite 2005.

| Methods | Prospective randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | From June to December 2004, they studied a total of 105 women scheduled for hysteroscopy at the department of obstetrics and gynaecology of Kaunas University hospital of Medicine, Kaunas, Lithuania. The inclusion criteria were being perimenopausal or postmenopausal women, having definite indication for hysteroscopy and being in good health. Allergy to prostaglandin and lesions of the endocervical canal were considered as exclusion criteria. | |