Abstract

To evaluate the feasibility of using transgenic rabbits expressing CCR5 and CD4 as a small-animal model of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV) disease, we examined whether the expression of the human chemokine receptor (CCR5) and human CD4 would render a rabbit cell line (SIRC) permissive to HIV replication. Histologically, SIRC cells expressing CD4 and CCR5 formed multinucleated cells (syncytia) upon exposure to BaL, a macrophagetropic strain of HIV that uses CCR5 for cell entry. Intracellular viral capsid p24 staining showed abundant viral gene expression in BaL-infected SIRC cells expressing CD4 and CCR5. In contrast, neither SIRC cells expressing CD4 alone nor murine 3T3 cells expressing CCR5 and CD4 exhibited significant expression of p24. These stably transfected rabbit cells were also highly permissive for the production of virions upon infection by two other CCR5-dependent strains (JR-CSF and YU-2) but not by a CXCR4-dependent strain (NL4-3). The functional integrity of these virions was demonstrated by the successful infection of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) with viral stocks prepared from these transfected rabbit cells. Furthermore, primary rabbit PBMC were found to be permissive for production of infectious virions after circumventing the cellular entry step. These results suggest that a transgenic rabbit model for the study of HIV disease may be feasible.

An important scientific goal has been the development of small-animal models of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV) infection that simulate the stages of HIV disease in humans (32, 39, 46, 53). Even though severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice transplanted with fetal human tissue (e.g., thymus or peripheral blood lymphocytes [reviewed in reference 47]) provide the means to study specific organ pathology induced by HIV in vivo, they do not fully represent the complex immunopathogenesis of HIV disease, which involves different tissues and occurs over an extended period of time, resulting in AIDS (48). Of the small animals tested as alternative models, rabbits have been proposed to be the most promising in certain respects (53). Infection with HIV, defined as the replication of detectable virus in the host and the development of antibodies to HIV, has been well documented in native rabbits in vivo (14, 20, 26, 36, 49). However, immunosuppression in HIV-infected rabbits has been observed inconsistently, and other clinical signs have been detected in rabbits only upon exposure to both human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 and HIV (36). The absence of AIDS-like symptoms in these animals may be explained by the low level of viral replication. Viral replication has been observed in native rabbit cells in vitro but never at levels approaching that in human cells (29, 37, 57). The production of mature and infectious viral particles relies on the accurate interplay of regulatory HIV proteins with cellular host factors (4, 12, 28, 30, 44, 54, 59). Unlike those in murine cells (56), cellular host factors in rabbit cells may support regulatory HIV proteins critical for viral transcription, suggesting that the main barrier to the replication cycle occurs before transcription, presumably at the level of viral entry (8).

Efficient HIV entry has long been recognized to require the human cell surface protein CD4 (43). However, expression of human CD4 does not render cells in mice and rabbits entirely permissive to the HIV replication cycle (10, 18, 42). The recent discovery that human chemokine receptors are essential cofactors for HIV entry into cells might explain the viral entry block in these cells (3, 9, 16, 17, 19). The principal chemokine receptors for HIV entry are CCR5 (3, 16, 17, 58), which mediates viral entry into macrophages (macrophagetropic viruses), and CXCR4 (19), which mediates entry into transformed T-cell lines (T-cell line-tropic viruses). Macrophagetropic viruses (using CCR5) predominate in HIV-positive patients over a long period of time (51) and may be responsible for sexual transmission of HIV (13, 41, 50, 60). In contrast, T-cell line-tropic viruses (using CXCR4) emerge in at least half of patients later in the course of HIV disease and have been associated with an acceleration of the immunodeficiency (11, 27, 33).

These findings suggest the possibility that a small-animal model of HIV disease could be generated by the expression of human CD4 and coreceptors in transgenic lines. However, in mice such transgenes were recently found to be insufficient to support HIV replication, which is likely to be the result of postentry restrictions (6). Alternatively, since earlier work suggested that the main restriction in rabbit cells may be at the level of viral entry, rabbit cells expressing human chemokine receptors and CD4 might permit robust viral replication and spread. The present study was performed to evaluate the feasibility of transgenic rabbits expressing human CCR5 and CD4 as a small-animal model of HIV infection. Using transfected cell lines, we compared the permissivity of rabbit-, mouse-, and human-derived cells for HIV infection after introduction of human CCR5 and CD4.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

HeLa cells expressing human CD4 (HeLa-CD4, provided by B. Chesebro) (52) or both CD4 and CCR5 (HeLa-CD4/CCR5, provided by D. Kabat) (52) and 3T3 cells (a murine fibroblast cell line, provided by D. Littman) (16) expressing human CD4 (3T3-CD4) or both CD4 and CCR5 (3T3-CD4/CCR5) were grown as previously described (16, 52). To generate rabbit cells expressing human CD4, parental SIRC cells (a rabbit fibroblast-like cell line derived from the cornea of a normal rabbit with no detectable reverse transcriptase activity; American Type Culture Collection [ATCC CCL-60], Rockville, Md.) were transfected by the calcium phosphate method with an expression vector (pcDNA3; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) encoding human CD4 and a neomycin resistance gene (pCD4neo [25]) and were selected in culture medium with 400 μg of neomycin (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.) per ml. To introduce human CCR5, SIRC-CD4 cells were transfected with an expression vector (LPXsrf-CCR5; see below) encoding an epitope-tagged form of human CCR5 (5) and a puromycin resistance gene and were selected in medium containing 0.5 μg of puromycin per ml. Clones for surface expression of either CD4 or both CD4 and CCR5 were screened by flow cytometry (see below). Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from random donors and rabbit PBMC were recovered by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation (Histopaque 1077; Sigma Diagnostics). Human and rabbit PBMC were activated overnight by incubation in RPMI 1640 medium (Mediatech) with phytohemagglutinin (PHA; 5 mg/ml; Sigma) or PHA-M (2 ml of rehydrated PHA-M per 100 ml of culture medium; Life Technologies), respectively, per ml overnight. Human macrophages were isolated as previously described by Miller et al. (45).

Construction of the CCR5 expression plasmid.

Plasmid pcDNA3-CCR5 (5) was digested with HindIII and XhoI, which released the epitope-tagged CCR5 fragment. This fragment was then ligated into the linearized retroviral vector LPXsrf, which had been digested with HindIII and SalI. LPXsrf (provided by A. DeFranco) is a Moloney murine leukemia virus-based retroviral vector containing a puromycin resistance gene.

Flow cytometry.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) was performed as previously described (5), using a phycoerythrin-conjugated monoclonal antibody (MAb) against CD4 (Leu-3a; Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) and a murine MAb against the epitope tag of CCR5 (anti-FLAG MAb M1; Eastman Kodak Co., New Haven, Conn.).

Transfection.

Transfection to assess CD4 downregulation by Nef was performed with SIRC-CD4 cells. Transfections for assessing auxiliary HIV gene function were done in SIRC-CD4, HeLa-CD4, and 3T3-CD4 cells in triplicate. All transfections were performed by the calcium phosphate method (Profection Mammalian Transfection Systems, Madison, Wis.). Testing was initiated 48 h after transfection as described below.

To assess viral gene expression independently of viral entry, cells were transfected with the molecular clone pNL4-3 (see below). Supernatants of the transfected cells were assessed for viral capsid p24 antigen production by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (HIV-1 ELISA; Dupont, NEN, Life Science Products, Boston, Mass.). Further, human PHA-blasted PBMC were exposed to the supernatants to determine if the virions produced by the various cell lines were mature and able to initiate infection in indicator cells. Virus production in these PBMC was verified by assessing p24 viral expression in the supernatant.

To assess CD4 downregulation by Nef, SIRC-CD4 cells were cotransfected by pNef (expression vector [25]) and pCMV4-CD8 (provided by R. Geleziunas). Because cotransfected plasmids typically enter the same cells (25), CD8+ cells represent cells most likely to have been successfully transfected by pNef. Transfected cells were stained with phycoerythrin-labeled MAb against CD4 and fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled MAb against CD8 (Becton Dickinson) and subsequently analyzed for CD4 expression by FACS by gating on CD8+ cells.

To assess Tat function, pSVtat (Tat expression vector) and pLTR-CAT (reporter construct encoding chloramphenicol transferase [CAT] activity driven by a long terminal repeat [LTR]) (both provided by M. Peterlin) (4) and pSVβ-gal (Promega, Madison, Wis.) were cotransfected in equimolar amounts. To assess Rev function, pCMVrev (Rev expression vector) and pDM128 (reporter construct) (both provided by T. Parslow) (31) and pSVβ-gal were cotransfected in equal amounts. In both cases, the cotransfection with pSVβ-gal allowed for constitutive expression of β-galactosidase. To compensate for the different transfection efficiencies of the cell lines, equivalent amounts of cellular extract as determined by β-galactosidase activity (Invitrogen) were assayed for CAT activity with an ELISA kit (Boehringer Mannheim Co., Indianapolis, Ind.).

To assess whether primary rabbit cells are able to produce mature virions independently of viral entry, activated rabbit PBMC (2 × 106) were electroporated with 15 μg of pYU-2 DNA (see below) at 950 μFD and 280 V (Bio-Rad Gene Pulser), and the supernatant was harvested 2 days after electroporation. To examine whether virion particles produced by rabbit PBMC are functional, human PBMC were exposed to this supernatant and were monitored over time for p24 generation.

Viruses.

Viral stocks of YU-2 and NL4-3 were obtained by transfecting 293T cells with the molecular clones pYU-2 and pNL4-3 (from B. Hahn and M. Martin via the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program) (1, 40). Viral stocks of BaL (from R. Gallo, S. Gartner, and M. Popovic via the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program) (23) were grown on macrophages, and viral stocks of JR-CSF (provided by B. Chesebro) (35) were expanded in PHA-activated PBMC from healthy donors. YU-2, BaL, and JR-CSF are macrophagetropic viruses which predominantly use CCR5 for viral entry. YU-2, in addition, can enter cells by using CCR3 (3, 9, 16, 52). NL4-3 has a tropism for T cells and uses predominantly CXCR4 for cell entry (52). High-titer HIV aliquots with viral capsid p24 values greater than 150 ng/ml were used for all inoculations.

Histology.

Infected cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, washed, and dried at room temperature. Cells were subsequently stained with hematoxylin-eosin and examined by light microscopy.

Northern blotting.

Northern blot analysis was performed as described previously (38), using an α-32P-labeled fragment of full-length YU-2.

p24 measurements.

The intracellular p24 assay measuring cell entry of HIV was performed as previously described (5). For secreted p24 antigen, 1 day after plating, SIRC, HeLa, and 3T3 cells expressing CD4 or both CD4 and CCR5 into a 96-well plate (104 cells/well) were inoculated with HIV strains. Twenty-four hours after infection, the cells were washed three times to remove exogenous virus and the medium was replaced. Culture supernatants were harvested 2 days after infection and analyzed for p24 antigen content.

RESULTS

Nef, Tat, and Rev functions in rabbit, human, and murine cells.

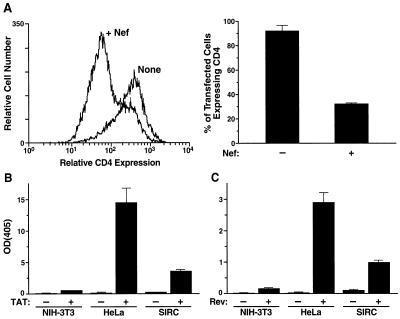

To determine whether SIRC cells support the functions of select regulatory HIV proteins, we studied the activities of Nef, Tat, and Rev. First, Nef promotes the endocytosis and lysosomal degradation of cell surface CD4 in human cells (22) through mechanisms that are incompletely understood (2, 24). This function of Nef was studied by transfecting SIRC-CD4 cells with expression vectors encoding Nef and cell surface CD8. Concomitantly supplied plasmids are typically taken up by the same cells. Thus, after staining with a MAb against CD8, gating on CD8+ cells selected cells most likely to be transfected with Nef. CD8+ cells were subsequently analyzed for CD4 downregulation. CD4 expression was decreased by approximately 60% in SIRC-CD4 cells transfected with a Nef-encoding vector, which is similar to the decrease in human-derived cells (21) (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Rabbit cells support Nef, Tat, and Rev function. (A) To estimate CD4 downregulation by Nef, a vector encoding Nef and a vector encoding CD8 were cotransfected into SIRC-CD4 cells. Surface protein expression was detected by staining with a MAb against CD4 or CD8 followed by FACS analysis. Cotransfection was performed because plasmids typically enter the same cells. By gating on CD8+ cells, mainly cells transfected with pNef were analyzed for CD4 expression. (B) Tat function was measured in cells cotransfected with a reporter construct (pLTR-CAT) and a vector encoding Tat protein. (C) Rev function was measured in cells cotransfected with a reporter construct (pDM128) and a vector encoding Rev protein. All analyses were performed in triplicate. OD(405), optical density at 405 nm.

Second, Tat is a potent activator of HIV transcription, and it requires cellular host factors to be fully active (28, 30, 44, 59). To assess this function, rabbit, human, and murine cells were cotransfected with a reporter construct (pLTR-CAT), an expression vector for Tat (pSVtat), and a constitutive expression vector for β-galactosidase. The cotransfection with an expression vector for β-galactosidase allowed us to correct for different transfection efficiencies between the cell lines. Rabbit cells clearly supported Tat activity detected by CAT induction, although at somewhat lower levels than did human cells (Fig. 1B). In contrast, murine cells did not support Tat-dependent transactivation of the LTR substantially over background levels (Fig. 1B).

Third, Rev controls splicing and the nuclear export of viral RNA species through interactions with cellular proteins and thus mediates the ordered temporal expression of the various gene products (12, 54). In the absence of intact Rev function, HIV transcripts reach the cytoplasm exclusively in the form of the multiply spliced 2-kb mRNA species, which encode regulatory HIV proteins, and not in the form of unspliced (9-kb) or singly spliced (4-kb) mRNA, both of which encode structural HIV proteins. Rev function was assessed by a reporter construct (pDM128) and by supplying Rev by an expression vector (pCMVrev) (31). Rev activity was clearly evident in SIRC cells, but this activity was somewhat lower than that in human cells and much more prominent than that in murine cells (Fig. 1C). These findings demonstrate that rabbit cells, unlike murine cells, bear the cellular host factors required to support the functions of HIV proteins that are critical for the HIV replication cycle.

SIRC-CD4 cells transfected by pNL4-3 produce infectious viruses.

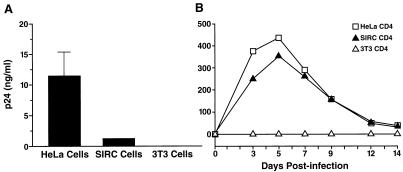

To determine if SIRC cells can support production of mature HIV virions independently of viral entry, SIRC-CD4 cells were transfected with the proviral molecular clone pNL4-3 to circumvent the cellular entry step. SIRC-CD4 cells clearly supported viral production, although at levels somewhat lower than that of HeLa-CD4 cells transfected with pNL4-3 (Fig. 2A). In contrast, no p24 antigen was detected upon transfection of murine 3T3-CD4 cells (Fig. 2A). Functional integrity of virions produced by rabbit cells was shown by the production of p24 antigen of human PBMC exposed to supernatants from transfected rabbit cell cultures (Fig. 2B), while PBMC exposed to supernatant from transfected murine cells showed no signs of infection. Thus, rabbit cells, unlike murine cells, are able to carry out the basic postentry activities to produce mature virions. This finding implies that the major barrier to the HIV replication cycle in rabbit cells occurs before reverse transcription.

FIG. 2.

Rabbit cells produce infectious viral particles independently of viral entry. (A) Cells were transfected by the molecular clone pNL4-3. Two days later, supernatants were analyzed for the production of viral capsid p24 antigen. (B) To assess the functional integrity of virions produced by transfection, human PBMC were exposed to the supernatants of transfected cells, and p24 levels in supernatants of the PBMC were analyzed at different time points.

SIRC cells expressing human CD4 and CCR5 form multinucleated giant cells upon exposure to CCR5-dependent viral strains.

To examine directly the effects of chemokine receptor and CD4 expression in rabbit cells on the HIV replication cycle, we generated SIRC cell lines that stably expressed CCR5 and CD4. Cell surface expression of these proteins was verified by flow cytometry (data not shown).

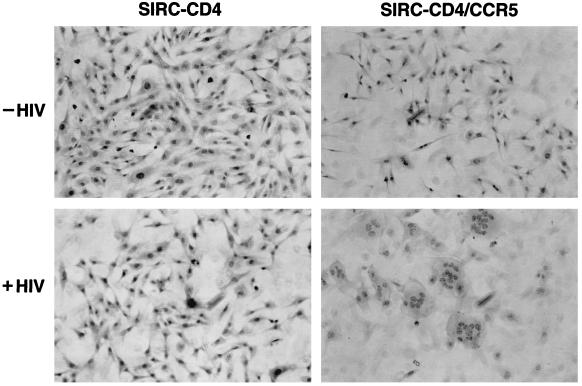

The induction of multinucleated giant cells (syncytia) has been considered a key feature of T-cell line-tropic viruses (7, 15, 33, 34, 51). However, we and others have recently suggested that the ability to induce syncytia experimentally rather reflects the type of coreceptor expressed in given target cells infected by distinct viruses (3, 9, 16, 17, 52). Indeed, in SIRC-CD4/CCR5 cultures infected by the CCR5-dependent HIV strain BaL, multinucleated giant cells were abundant, indicating the ability of macrophagetropic viruses to induce such cytopathic effects in the context of expression of the proper coreceptors (Fig. 3). In contrast, no cytopathic effects were seen in rabbit cells expressing only CD4 after infection with either CCR5-dependent viral strain or in SIRC-CD4/CCR5 cells infected by NL4-3, which uses CXCR4 (not shown). Similar disruptions of cellular morphology were also observed in SIRC-CD4/CCR5 cell cultures infected by YU-2 and JR-CSF, both of which are capable of using CCR5 (not shown). These findings demonstrate that the main barrier to HIV infection in rabbit cells is at the level of viral entry and suggest that rabbit cells expressing CD4 and CCR5 may be highly susceptible to the HIV replication cycle.

FIG. 3.

CCR5-dependent induction of syncytia in SIRC-CD4/CCR5 cells infected by BaL. Hematoxylin-eosin staining was performed 2 days after infection.

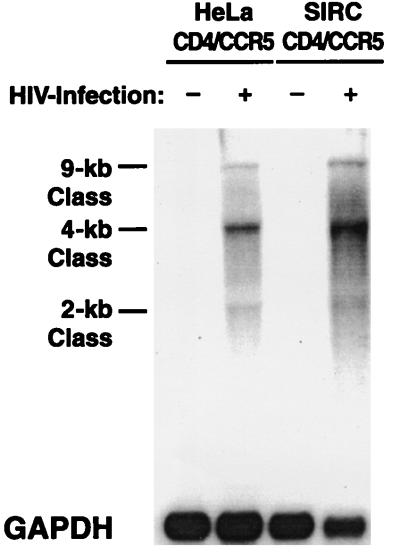

Viral gene expression in SIRC-CD4/CCR5 cells infected by YU-2.

To assess the ability of rabbit cells to support viral gene expression upon infection by HIV, we measured viral transcripts in the cytoplasm of infected cells by Northern blot analysis. SIRC-CD4/CCR5 cells infected with YU-2 displayed the expected 2-, 4-, and 9-kb classes of viral mRNA, indicating intact viral promoter, transactivation, and splicing functions (Fig. 4). No viral transcripts were detected in cells expressing only CD4 that were exposed to HIV. The intensity of the hybridization signals was similar with RNAs obtained from infected rabbit or human cells expressing CD4 and CCR5 (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

HIV-specific hybridization transcripts obtained from total RNA of infected rabbit and human cell cultures. Two days after infection with YU-2, total RNA was isolated, resolved by electrophoresis, and transferred onto a Zeta GT probe. The blot was probed with an α-32P-labeled fragment of full-length YU-2. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

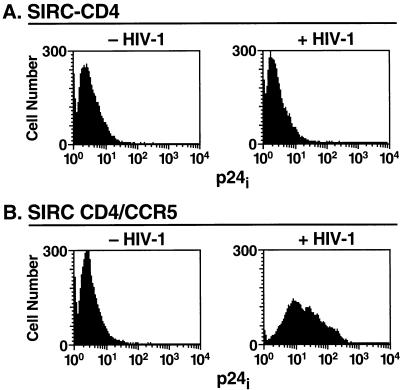

To assess viral protein production in rabbit cells, SIRC cells expressing CD4 or both CD4 and CCR5 were exposed to BaL. Two days later, the cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for intracellular viral capsid p24 expression. SIRC-CD4/CCR5 cells showed significant expression of intracellular p24 after infection with BaL. In contrast, neither SIRC-CD4 cells nor murine 3T3-CD4/CCR5 cells exhibited significant expression of p24 upon inoculation with BaL (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Intracellular viral gene expression indicates vigorous viral replication. After fixation and permeabilization, SIRC cells infected with BaL were stained with MAb against intracellular p24 (p24i) antigen.

Production of mature virions by SIRC-CD4/CCR5 cells upon exposure to various CCR5-dependent viral strains.

To assess the permissiveness of rabbit cells expressing CD4 and CCR5 to various CCR5-dependent viral strains, we also assessed viral capsid p24 production in the supernatant of infected cell cultures. SIRC-CD4/CCR5 cells and HeLa-CD4/CCR5 cells showed abundant secretion of p24 upon infection with BaL, YU-2, and JR-CSF, all of which are viral strains that use CCR5 as a coreceptor (Fig. 6A). The amounts of p24 antigen produced were similar in rabbit and human cells but varied depending on the viral strain used for inoculation. No infection of rabbit cells by NL4-3 was observed (Fig. 6A), which is consistent with the lack of human CXCR4 on these cells. No p24 antigen was produced by murine cells infected by these viruses, even in the presence of human CD4 and CCR5. These results indicate that the expression of CCR5 and CD4 on SIRC cells confers general susceptibility to infection with CCR5-dependent HIV strains but not with CXCR4-dependent strains.

FIG. 6.

Extracellular viral gene expression and production of mature virions in rabbit cells. (A) Two days after infection of cells with various HIV strains, culture supernatants were harvested and analyzed for p24 antigen. (B) To test the functional integrity of virions produced, human PBMC were exposed to the supernatant of transfected cells, and p24 levels in supernatants of the PBMC were analyzed at different time points.

To determine if the virus produced by rabbit cells was fully infectious, we inoculated PHA-activated human PBMC with viral stocks prepared from infected cell cultures. Viral stocks from both human and rabbit cells could be easily propagated in cultured human PBMC and reached similar peak values approximately 8 days after inoculation although with somewhat different kinetics, indicating the functional integrity of virus generated upon infection of rabbit cells (Fig. 6B).

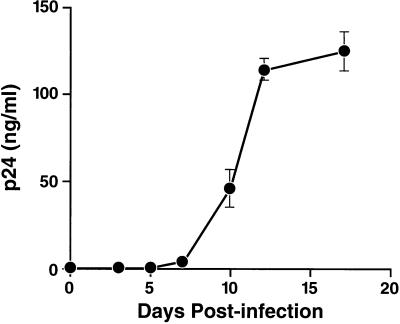

Primary rabbit PBMC electroporated with pYU-2 produce infectious virus.

To examine whether primary rabbit PBMC are able to produce infectious virus upon bypassing the entry step, activated rabbit PBMC were electroporated with pYU-2. Supernatants of three of six electroporations showed detectable p24 antigen production with a yield of 0.05 to 1.5 ng/ml, consistent with a very low transfection efficiency of primary rabbit PBMC. To assess whether virion particles produced by rabbit PBMC are functional, human PBMC were exposed to these supernatants. Indeed, these cultures produced abundant p24 antigen over time (Fig. 7), indicating that rabbit PBMC are able to support postintegration steps in the HIV replication cycle, leading to release of infectious virions.

FIG. 7.

Production of mature virions by primary rabbit PBMC. Human PBMC were exposed to supernatant of rabbit PBMC, which had been electroporated with pYU-2 2 days before. As demonstrated by the abundant production of p24 antigen in human PBMC, virions generated by rabbit PBMC were infectious.

DISCUSSION

This study provides a clear demonstration that expression of human CCR5 in rabbit cells abolishes the entry block for HIV and permits HIV replication at levels similar to those in human cells. In addition, the virions produced by HIV-infected SIRC-CD4/CCR5 cells are intact and infectious as determined by several criteria. These findings imply that a transgenic rabbit model for CCR5 and CD4 may be feasible, although it is impossible to predict the levels of viral replication that would be achieved in vivo or the extent of disease that would be associated with such an infection.

The rabbit cell line that we used has no inherent susceptibility to infection by HIV. Nonetheless, this rabbit cell line appeared to have the necessary host-specific factors to support the regulatory HIV proteins that are critical for infectivity. First, Nef downregulated CD4 in SIRC-CD4 cells to an extent similar to that reported for human and murine cells (21), consistent with the notion that Nef-mediated downregulation of CD4 is neither species nor tissue specific (21). Second, the HIV LTR in SIRC cells was clearly transactivated by Tat, although somewhat less efficiently than in HeLa cells. Other reports have suggested that Tat function is intact in native rabbit T cells (8), implying that at least certain rabbit tissues express the cellular host factors needed for Tat function. Third, the expression of early and late viral gene products requires host cell factors to interact appropriately with Rev and its responsive elements in viral RNA (12, 54). The present transfection data indicated that Rev constructs functioned properly in rabbit cells, albeit somewhat less efficiently than in HeLa cells. Insignificant levels of Tat and Rev function were seen in murine cells in these experiments, as previously reported (56). Thus, our findings confirm and extend the observations of intact function of Tat and Rev previously reported in other rabbit cell lines (8) and, in addition, demonstrate intact Nef function in rabbit cells.

Evaluating the activity of HIV proteins is useful for delineating potential barriers to HIV replication in a cell line, but it provides no information about the ability of the cells to produce infectious viral particles. To test the ability of rabbit cells to support the HIV replication cycle independently of viral entry, we transfected the cells with the molecular clone pNL4-3. Indeed, consistent with earlier studies, they produced viral capsid p24 antigen at a lower level than did HeLa cells (8). The difference in p24 antigen production may reflect lower transfection efficiency in rabbit cells than in HeLa cells or lower efficiency of HIV regulatory proteins. Importantly, the virions produced by this method were infectious, as demonstrated by the positive infection of human PBMC by viral stocks prepared from these transfected cells. No viral capsid p24 was detected upon transfection of murine cells, and as expected, human PBMC exposed to supernatant from those cells were not infected.

The key experiments in our study were to determine if coexpression of CD4 and CCR5 would render rabbit cells permissive to HIV infection, including viral entry and production of virions capable of spreading infection. Indeed, SIRC-CD4/CCR5 cells infected with BaL, a macrophagetropic virus, formed massive multinucleated giant cells (syncytia) and showed complete disruption of the cellular structure, as was observed in infected HeLa-CD4/CCR5 cells. Similar destruction of the cell architecture was also observed after infections by the CCR5-dependent strains, JR-CSF and YU-2, but not after infection with the CXCR4-dependent strain, NL4-3. No cytopathic effects were observed in SIRC-CD4 cells infected with BaL. Thus, these results demonstrate that the main barrier to efficient HIV replication in rabbit cells is at the level of viral entry and is removed by the expression of human cell surface molecules. Our observations also substantiate the notion (3, 9, 16, 17, 52) that syncytium formation is induced not only by T-cell line-tropic HIV strains but also by macrophagetropic strains in the context of appropriate cognate coreceptors.

Northern analysis of SIRC-CD4/CCR5 and HeLa-CD4/CCR5 cells infected by YU-2 showed similar intensities of viral transcripts, which implies that similar amounts of viral transcripts were produced in these cells. In contrast to our findings, transcripts from HIV-infected native rabbit T cells were reported to be of much lower intensity than those from infected human T cells (8). We believe this difference reflects inefficient viral entry into native rabbit T cells rather than a lack of cellular factors supporting Rev function, although tissue-specific differences in host cell factors cannot be excluded as a factor in these studies.

Staining for intracellular viral capsid p24 antigen of BaL-infected SIRC-CD4/CCR5 cells also confirmed vigorous viral gene expression, which indicates permissivity to the HIV replication cycle and corroborates the histological findings. In contrast, neither SIRC-CD4 cells nor murine 3T3-CD4/CCR5 cells exhibited significant p24 expression.

The general susceptibility of SIRC CD4/CCR5 cells to CCR5-dependent strains was also verified by measuring p24 antigen production by cells infected by JR-CSF, YU-2, and BaL. As expected, no infection could be documented in SIRC-CD4/CCR5 cells infected with NL4-3, a T-cell line-tropic virus that uses CXCR4, indicating the selective susceptibility of these cells to CCR5-dependent strains. Since levels of virus production as assessed by p24 antigen levels were similar in rabbit and human cells, the lower efficiency of regulatory HIV protein function in rabbit cells does not appear to be critical for overall infectivity. The production of viral capsid p24 antigen in SIRC-CD4/CCR5 cells was 100 to 4,000 times higher (depending on the viral stain) than that in transformed rabbit T-cell lines lacking appropriate human chemokine receptors (8).

The final and most crucial test of virion integrity is the ability of virions to infect other cells. This was demonstrated by their successful passage to human PBMC. Thus, there are no absolute blocks or restrictions to the HIV replication cycle and the spread of infectious HIV virions in rabbit cells. One report has described the production of immature virions by primary rabbit PBMC infected by HIV (55). It is more likely that virions infecting primary rabbit PBMC lacking human chemokine receptors and human CD4 will be targeted to an unusual endocytic pathway, resulting in their disruption. Indeed, in the present study, electroporation experiments using primary rabbit PBMC confirmed that these cells are able to support postintegration steps in the HIV replication cycle. Thus, we have no reason to conclude that rabbit PBMC have an intrinsic inability to carry out the basic activities required for HIV replication.

In conclusion, viral replication in rabbit cells expressing human CCR5 and CD4 in vitro approaches the level seen in human cells and is markedly higher than that in murine cells. HIV virions produced by these cells are able to support spreading infection and successfully infect human PBMC. These findings suggest that transgenic rabbits expressing CCR5 and CD4 may support reasonable levels of HIV replication in vivo, and we speculate that such animals might serve as a useful small-animal model for HIV disease. A small-animal model that simulates selected stages of HIV transmission and/or disease pathogenesis in humans would be invaluable for the study of HIV disease, mechanisms of transmission and pathogenesis, and treatment or prevention strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Bruce Chesebro, Anthony DeFranco, Romas Geleziunas, David Kabat, Dan Littman, Matija Peterlin, and Tris Parslow for materials, Stephen Ordway and Gary Howard for editorial assistance, John Carroll and Stephen Gonzales for the preparation of figures, Yang He for technical assistance, and Jessica Diamond and Airion Rapaport for preparing the manuscript.

This work was supported by the J. David Gladstone Institutes, the UCSF Center for AIDS Research, the UCSF AIDS Clinical Research Center, and the National Institutes of Health (grants AI28240-09S1 and AI42654-01). R.F.S. was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi A, Gendelman H E, Koenig S, Folks T, Willey R, Rabson A, Martin M A. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J Virol. 1986;59:284–291. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.2.284-291.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiken C, Konner J, Landau N R, Lenburg M E, Trono D. Nef induces CD4 endocytosis: requirement for a critical dileucine motif in the membrane-proximal CD4 cytoplasmic domain. Cell. 1994;76:853–864. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alkhatib G, Combadiere C, Broder C C, Feng Y, Kennedy P E, Murphy P M, Berger E A. CC CKR5: A RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science. 1996;272:1955–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alonso A, Derse D, Peterlin B M. Human chromosome 12 is required for optimal interactions between Tat and TAR of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in rodent cells. J Virol. 1992;66:4617–4621. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4617-4621.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atchison R E, Gosling J, Monteclaro F S, Franci C, Digilio L, Charo I F, Goldsmith M A. Multiple extracellular elements of CCR5 and HIV-1 entry: dissociation from response to chemokines. Science. 1996;274:1924–1926. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Browning J, Horner J W, Pettoello-Mantovani M, Raker C, Yurasov S, Depinho R A, Goldstein H. Mice transgenic for human CD4 and CCR5 are susceptible to HIV infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14637–14641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chesebro B, Wehrly K, Nishio J, Perryman S. Mapping of independent V3 envelope determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 macrophage tropism and syncytium formation in lymphocytes. J Virol. 1996;70:9055–9059. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.9055-9059.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho S, Kindt T J, Zhao T M, Sawasdikosol S, Hague B F. Replication of HIV type 1 in rabbit cell lines is not limited by deficiencies in tat, rev, or long terminal repeat function. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1995;11:1487–1493. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choe H, Farzan M, Sun Y, Sullivan N, Rollins B, Ponath P D, Wu L, Mackay C R, LaRosa G, Newman W, Gerard N, Gerard C, Sodroski J. The b-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell. 1996;85:1135–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clapham P, McKnight A, Simmons G, Weiss R. Is CD4 sufficient for HIV entry? Cell surface molecules involved in HIV infection. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B. 1993;342:67–73. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1993.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Connor R I, Sheridan K E, Ceradini D, Choe S, Landau N R. Change in coreceptor use correlates with disease progression in HIV-1-infected individuals. J Exp Med. 1997;185:621–628. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cullen B R, Malim M H. The HIV-1 rev protein: prototype of a novel class of eukaryotic post-transcriptional regulators. Trends Biomed Sci. 1991;16:346–350. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90141-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dean M, Carrington M, Winkler C, Huttley G A, Smith M W, Allikemts R, Goedert J J, Buchbinder S P, Vittinghoff E, Gomperts E, Donfield S, Vlahov D, Kaslow R, Saah A, Rinaldo C, Detels R, O’Brien S Hemophilia Growth and Development Study; Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study; Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study; San Francisco Cohort Study; ALIVE Study. Genetic restriction of HIV-1 infection and progression to AIDS by a deletion allele of the CKR5 structural gene. Science. 1996;273:1856–1862. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Debiaggi M, Bruno R, Carlevari M, Achilli G, Emanuelli B, Cereda P M, Romero E, Filice G. HIV type 1 intraperitoneal infection of rabbits permits early detection of serum antibodies to Gag, Pol, and Env proteins, neutralizing antibodies, and proviral DNA from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1995;11:287–296. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Jong J-J, Goudsmith J, Keulen W, Klaver B, Krone W, Tersmette M, De Ronde A. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clones chimeric for the envelope V3 domain differ in syncytium formation and replication capacity. J Virol. 1992;66:757–765. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.757-765.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng H, Liu R, Ellmeier W, Choe S, Unutmaz D, Burkhart M, Di Marzio P, Marmon S, Sutton R E, Hill C M, Davis C B, Peiper S C, Schall T J, Littman D R, Landau N R. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature. 1996;381:661–666. doi: 10.1038/381661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway G P, Martin S R, Huang Y, Nagashima K A, Cayanan C, Maddon P J, Koup R A, Moore J P, Paxton W A. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature. 1996;381:667–673. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunn C S, Mehtali M, Houdebine L M, Gut J P, Kirn A, Aubertin A M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of human CD4-transgenic rabbits. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:1327–1336. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-6-1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng Y, Broder C C, Kennedy P E, Berger E A. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Filice G, Cereda P M, Varnier O E. Infection of rabbits with human immunodeficiency virus. Nature. 1988;335:366–369. doi: 10.1038/335366a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia J V, Alfano J, Miller A D. The negative effect of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef on cell surface CD4 expression is not species specific and requires the cytoplasmic domain of CD4. J Virol. 1993;67:1511–1516. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1511-1516.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia J V, Miller A D. Serine phosphorylation-independent downregulation of cell-surface CD4 by nef. Nature. 1991;350:508. doi: 10.1038/350508a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gartner S, Markovits P, Markovits D M, Kaplan M H, Gallo R C, Popovic M. The role of mononuclear phagocytes in HTLV-III/LAV infection. Science. 1986;233:215–219. doi: 10.1126/science.3014648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geleziunas R, Miller M D, Greene W C. Unraveling the function of HIV Type 1 Nef. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1996;12:1579–1582. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldsmith M A, Warmerdam M T, Atchison R E, Miller M D, Greene W C. Dissociation of the CD4 downregulation and viral infectivity enhancement functions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Nef. J Virol. 1995;69:4112–4121. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4112-4121.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon M R, Truckenmiller M E, Recker D P, Dickerson D R, Kuta E, Kulaga H, Kindt T J. Evidence for HIV-1 infection in rabbits. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;616:270–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb17847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goudsmit J. The role of viral diversity in HIV pathogenesis. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;10:S15–S19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenberg M E, Ostapenko D A, Mathews M B. Potentiation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat by human cellular proteins. J Virol. 1997;71:7140–7144. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.7140-7144.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hague B F, Sawasdikosol S, Brown T J, Lee K, Recker D P, Kindt T J. CD4 and its role in infection of rabbit cell lines by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Immunology. 1992;89:7963–7967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.7963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hart C E, Ou C Y, Galphin J C, Moore J, Bacheler L T, Wasmuth J, Petteway S R, Schochetman G. Human chromosome 12 is required for elevated HIV-1 expression in human-hamster hybrid cells. Science. 1989;246:488–491. doi: 10.1126/science.2683071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hope T J, Huang X, McDonald D, Parslow T G. Steroid-receptor fusion of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev transactivator: mapping cryptic functions of the arginine-rich motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7787–7791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klotman P E, Rappaport J, Ray P, Kopp J B, Franks R, Bruggeman L A, Notkins A L. Transgenic models of HIV-1. AIDS. 1995;9:313–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koot M, Keet I P M, Vos A H V, de Goede R E Y, Roos M T L, Coutinho R A, Miedema F, Schellekens P T A, Tersmette M. Prognostic value of HIV-1 syncytium-inducing phenotype for rate of CD4+ cell depletion and progression to AIDS. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:681–688. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-9-199305010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koot M, Vos A H V, Keet R P M, de Goede R E Y, Dercksen M W, Terpstra F G, Coutinho R A, Miedema F, Tersmette M. HIV-1 biological phenotype in long-term infected individuals evaluated with an MT-2 cocultivation assay. AIDS. 1992;6:49–54. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199201000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koyanagi Y, Miles S, Mitsuyasu R T, Merrill J E, Vinters H V, Chen I S Y. Dual infection of the central nervous system by AIDS viruses with distinct cellular tropisms. Science. 1987;236:819–822. doi: 10.1126/science.3646751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kulaga H, Folks T, Rutledge R, Truckenmiller M E, Gugel E, Kindt T J. Infection of rabbits with human immunodeficiency virus 1. J Exp Med. 1989;169:321–326. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kulaga H, Folks T M, Rutledge R, Kindt T J. Infection of rabbit T-cell and macrophage lines with human immunodeficiency virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4455–4459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lamson G, Koshland M E. Changes in J chain and μ chain RNA expression as a function of B cell differentiation. J Exp Med. 1984;160:877–892. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.3.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewis A D, Johnson P R. Developing animal models for AIDS research—progress and problems. Trends Biotechnol. 1995;13:142–150. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(00)88925-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Y, Kappes J C, Conway J A, Price R W, Shaw G M, Hahn B H. Molecular characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cloned directly from uncultured human brain tissue: identification of replication-competent and -defective viral genomes. J Virol. 1991;65:3973–3985. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.8.3973-3985.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu R, Paxton W A, Choe S, Ceradini D, Martin S R, Horuk R, McDonald M E, Stuhlmann H, Koup R A, Landau N R. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply-exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell. 1996;86:367–377. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lores P, Boucher V, Mackay C, Pla M, von Boehmer H, Jami J, Barre-Sinoussi F, Weill J-C. Expression of human CD4 in transgenic mice does not confer sensitivity to human immunodeficiency virus infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1992;8:2063–2071. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maddon P J, Dalgleish A G, McDougal J S, Clapham P R, Weiss R A, Axel R. The T4 gene encodes the AIDS virus receptor and is expressed in the immune system and the brain. Cell. 1986;47:333–348. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90590-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Madore S J, Cullen B R. Genetic analysis of the cofactor requirement for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat function. J Virol. 1993;67:3703–3711. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.3703-3711.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller M D, Warmerdam M T, Gaston I, Greene W C, Feinberg M B. The human immunodeficiency virus-1 nef gene product: a positive factor for viral infection and replication in primary lymphocytes and macrophages. J Exp Med. 1994;179:101–113. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morrow W J W, Wharton M, Lau D, Levy J A. Small animals are not susceptible to human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Gen Virol. 1987;68:2253–2257. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-8-2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mosier D E. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of human cells transplanted to severe combined immunodeficient mice. Adv Immunol. 1996;63:79–125. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60855-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pantaleo G, Graziosi C, Fauci A S. The immunopathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:327–335. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302043280508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reina S, Markham P, Gard E, Rayed F, Reitz M, Gallo R C, Varnier O E. Serological, biological, and molecular characterization of New Zealand White rabbits infected by intraperitoneal inoculation with cell-free human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1993;67:5367–5374. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5367-5374.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Samson M, Libert F, Doranz B J, Rucker J, Liesnard C, Farber C-M, Saragosti S, Lapoumeroulie C, Cognaux J, Forceille C, Muyldermans G, Verhofstede C, Burtonboy G, Georges M, Imai T, Rana S, Yi Y, Smyth R J, Collman R G, Doms R W, Vassart G, Parmentier M. Resistance to HIV-1 infection in caucasian individuals bearing mutant alleles of the CCR-5 chemokine receptor gene. Nature. 1996;382:722–725. doi: 10.1038/382722a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schuitemaker H, Koot M, Kootstra N A, Dercksen M W, De Goede R E Y, van Steenwijk R P, Lange J M A, Schattenkerk J, Miedema F, Tersmette M. Biological phenotype of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clones at different stages of infection: progression of disease is associated with a shift from monocytotropic to T-cell-tropic virus populations. J Virol. 1992;66:1354–1360. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1354-1360.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Speck R F, Chesebro B, Atchison R E, Wehrly K, Charo I F, Goldsmith M A. Selective employment of chemokine receptors as human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coreceptors determined by individual amino acids within the envelope V3 loop. J Virol. 1997;71:7136–7139. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.7136-7139.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spertzel R O Public Health Service Animal Models Committee. Animal models of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Antiviral Res. 1989;12:223–230. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(89)90050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trono D, Baltimore D. A human cell factor is essential for HIV-1 Rev action. EMBO J. 1990;9:4155–4160. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07638.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tseng C K, Leibowitz J, Sell S. Defective infection of rabbit peripheral blood monocyte cultures with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:285–293. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Winslow B J, Trono D. The blocks to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat and Rev functions in mouse cell lines are independent. J Virol. 1993;67:2349–2354. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2349-2354.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamamura Y, Kotani M, Chowdhury M I H, Yamamoto N, Yamaguchi K, Karasuyama H, Katsura Y, Miyasaka M. Infection of human CD4+ rabbit cells with HIV-1: the possibility of the rabbit as a model for HIV-1 infection. Int Immunol. 1991;3:1183–1187. doi: 10.1093/intimm/3.11.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang L, Carruthers C D, He T, Huang Y, Cao Y, Wang G, Hahn B, Ho D D. HIV Type 1 subtypes, coreceptor usage, and CCR5 polymorphism. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1997;13:1357–1366. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou Q, Sharp P A. Novel mechanism and factor for regulation by HIV-1 Tat. EMBO J. 1995;14:321–328. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07006.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu T, Mo H, Wang N, Nam D S, Cao Y, Koup R A, Ho D D. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of HIV-1 in patients with primary infection. Science. 1993;261:1179–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.8356453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]