Abstract

Background

The initial phase II stuty (NCT03215693) demonstrated that ensartinib has shown clinical activity in patients with advanced crizotinib‐refractory, anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)‐positive non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Herein, we reported the updated data on overall survival (OS) and molecular profiling from the initial phase II study.

Methods

In this study, 180 patients received 225 mg of ensartinib orally once daily until disease progression, death or withdrawal. OS was estimated by Kaplan‒Meier methods with two‐sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Next‐generation sequencing was employed to explore prognostic biomarkers based on plasma samples collected at baseline and after initiating ensartinib. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) was detected to dynamically monitor the genomic alternations during treatment and indicate the existence of molecular residual disease, facilitating improvement of clinical management.

Results

At the data cut‐off date (August 31, 2022), with a median follow‐up time of 53.2 months, 97 of 180 (53.9%) patients had died. The median OS was 42.8 months (95% CI: 29.3‐53.2 months). A total of 333 plasma samples from 168 patients were included for ctDNA analysis. An inferior OS correlated significantly with baseline ALK or tumor protein 53 (TP53) mutation. In addition, patients with concurrent TP53 mutations had shorter OS than those without concurrent TP53 mutations. High ctDNA levels evaluated by variant allele frequency (VAF) and haploid genome equivalents per milliliter of plasma (hGE/mL) at baseline were associated with poor OS. Additionally, patients with ctDNA clearance at 6 weeks and slow ascent growth had dramatically longer OS than those with ctDNA residual and fast ascent growth, respectively. Furthermore, patients who had a lower tumor burden, as evaluated by the diameter of target lesions, had a longer OS. Multivariate Cox regression analysis further uncovered the independent prognostic values of bone metastases, higher hGE, and elevated ALK mutation abundance at 6 weeks.

Conclusion

Ensartinib led to a favorable OS in patients with advanced, crizotinib‐resistant, and ALK‐positive NSCLC. Quantification of ctDNA levels also provided valuable prognostic information for risk stratification.

Keywords: anaplastic lymphoma kinase, ctDNA, ensartinib, non‐small cell lung cancer, overall survival

Abbreviations

- ABL2

abelson‐related gene

- ALK

anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- AR

androgen receptor

- ARID1A

AT‐rich interaction domain 1A

- ARID2

AT‐rich interaction domain 2

- BCR

B cell receptor

- BRCA1/2

breast cancer susceptibility gene 1/2

- CDK12

cyclin‐dependent kinases12

- CI

confidence interval

- CNS

central nervous system

- CNV

copy number variation

- ctDNA

circulating tumor DNA

- DAG1

dystroglycan 1

- DNMT3A

DNA methyltransferase 3A

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor rescepor

- EML4

echinoderm microtubule‐associated protein‐like 4

- EPHA2

ephrin type‐A receptor 2

- ERBB2/3

Erb‐B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2/3

- hGE

haploid genome equivalents

- HR

hazard ratio

- IGF1R

insulin‐like growth factor‐1 receptor

- JAK1

Janus kinase 1

- KAT6A

K(lysine) acetyltransferase 6A

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- KIT

tyrosine protein kinase

- KMT2A/2B/2C

lysine (K)‐specific methyltransferase 2A/2B/2C

- KRAS

kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- MET

mesenchymal epithelial transition

- MSH6

mut‐S homolog 6

- NE

not evaluable

- NGS

next‐generation sequencing

- NOTCH2/3

notch homolog protein 2/3

- NR

not reached

- NSCLC

non‐small‐cell lung cancer

- ORR

objective response rate

- OS

overall survival

- PARP1/4

poly (ADP‐ribose) polymerase 1/4

- PBRM1

polybromo 1

- PFS

progression‐free survival

- PIK3CA

phosphatidylinositol‐4, 5‐bisphosphate 3‐kinase catalytic subunit alpha

- PIK3C2A

phosphatidylinositol‐4‐phosphate 3‐kinase, catalytic subunit type 2 alpha

- PLA

People's Liberation Army

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog

- RB1

retinoblastoma susceptibility gene

- RET

rearranged during transfection

- SNV

single nucleotide variants

- SYK

spleen tyrosine kinase

- TAPE

tandem atypical beta‐propeller

- TET1/2

ten‐eleven translocation 1/2

- Th17

T helper 17

- TKI

tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- TP53

tumor protein 53

- VAF

variant allele frequency

1. BACKGROUND

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene rearrangement occurs in approximately 3%‐5% of patients with non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [1, 2]. Despite the prolonged progression‐free survival (PFS) of east Asian patients with an objective response rate (ORR) of 87.5% for crizotinib, half of the patients experience disease progression after approximately 11 months [3, 4, 5]. Novel second‐ and third‐generation ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (e.g., alectinib, ceritinib, brigatinib, ensartinib and lorlatinib) have become the standard treatment after the development of resistance to crizotinib [6, 7, 8, 9, 10], and even in the first‐line settings [1, 5, 11‐13].

The resistance mechanisms of ALK TKIs are divided into ALK‐dependent mechanisms, including secondary mutations or amplification, and ALK‐independent mechanisms, such as activation of the bypass pathway or lineage changes, regardless of ALK activity [14, 15]. Concomitant tumor protein 53 (TP53) mutations may also affect ensartinib treatment efficacy, with unfavorable PFS outcomes in patients with advanced ALK‐positive NSCLC post‐crizotinib [16]. Therefore, elucidating the related resistance mechanisms is critical for deciding subsequent treatment strategies in patients with ALK‐positive NSCLC.

Given the minimal invasiveness compared with tissue biopsies, liquid biopsy has been employed to assess genomic alterations in advanced cancers and to explore mechanisms of resistance to ALK TKIs, highlighting its advantages [13, 17‐23]. Recently, plasma samples were collected and analyzed after progression on first‐, second‐, or third‐generation ALK TKIs, and the findings suggested that ALK mutations emerged as a result of increased lines of ALK inhibitors [24]. In our previous trial involving patients with crizotinib‐resistant ALK‐positive NSCLC, longitudinal circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis revealed ALK‐dependent (G1269A, G1202R, and E1210K mutations) and ALK‐independent (TP53 mutation) resistance mechanisms for ensartinib, emphasizing the significance of ctDNA analysis for monitoring tumor mutational evolution [16].

In addition to tracking tumor mutation evolution, ctDNA levels are usually quantified by evaluating the variant allele frequency (VAF) or haploid genomelents per milliliter of plasma (hGE/mL) in prospective and observational studies with large cohorts. It has been well recognized that ctDNA levels at multiple time points and the patterns of ctDNA changes may serve as prognostic biomarkers. For patients with resectable NSCLC, the positive predictive value, referring to the recurrence rate of ctDNA‐positive samples, was reported to be approximately 90% within 1 month after definitive treatment, indicating reliable predictive performance [25]. In advanced colorectal cancer, patients without recurrences showed clearance of ctDNA at the last sampling. Among cases of recurrence, longer overall survival (OS) was associated with a slower growth rate of ctDNA levels [26]. In a phase III trial of camrelizumab combined with chemotherapy for advanced squamous NSCLC, patients with ctDNA clearance after two cycles of treatment had prolonged PFS and OS [27]. Although the mutation landscapes of drug resistance have been profiled in detail in our previous work, survival analyses based on quantification and dynamic changes in ctDNA levels are lacking.

Here, we present the final OS data from our phase II study, in which molecular profiling of ctDNA was used to investigate the effects of ctDNA levels, echinoderm microtubule‐associated protein‐like 4 (EML4)‐ALK variant subtypes and concomitant TP53 mutations on clinical OS outcomes in patients with crizotinib‐resistant ALK‐positive NSCLC. By combining analyses of clinical risk factors and efficacy data, we hope our exploration provides some insights into tumor monitoring and therapeutic strategies.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design and patients

This study (NCT03215693) was a single‐arm, open‐label, phase II study in China. The full protocol has been published previously [9]. Briefly, eligible patients were aged 18 years or older, had locally advanced or metastatic ALK‐positive NSCLC and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≤ 2, and were previously resistant to crizotinib, with no other prior ALK TKI therapy. Patients with central nervous system (CNS) metastases were eligible if these metastases were asymptomatic and did not require steroid therapy. Previous CNS radiotherapy was permitted if the treated lesions were neurologically stable for at least 4 weeks before enrolment. We excluded patients with leptomeningeal metastases.

The patients received 225 mg of ensartinib (Betta Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China) orally once daily until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity or withdrawal. The dose could be reduced by no more than two dose levels (i.e., 200 mg per day or 150 mg per day) if adverse events occurred. A total of 182 patients participated in the clinical trial, and 168 patients with an assessable blood mutational spectrum were included in the ctDNA analysis.

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The study protocols were reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of Sun Yat‐sen University Cancer Center, State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China, Collaborative Innovation Center for Cancer Medicine (A2017‐014‐01) and each participating institution, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

2.2. Sample collection and ctDNA sequencing

For cases with available efficacy information, 333 blood samples collected from the 168 patients were sequenced, incorporating 168 samples at baseline and 165 samples on day 1 of cycle 3 (6 weeks after baseline). Three samples cannot be collected on day 1 of cycle 3 due to the personal reasons of the patients. DNA extraction, library preparation, sequencing and data analysis were performed as previously described [16]. Briefly, DNA was extracted from frozen plasma specimens using the QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Libraries were constructed with a KAPA Hyper Prep kit (Kapa Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA), enriched for a 212‐gene PanCancer gene panel using SureSelect XT‐HS Target Enrichment System (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq‐X10 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), with average sequencing depths of approximately 20,000 ×. Single‐nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertions/deletions were assessed using MuTect2 (https://gatk.broadinstitute.org/hc/en‐us/articles/360037593851‐Mutect2). LUMPY (version 0.2.13) [28] was used for gene fusion detection. Copy number variation (CNV) was detected using CNVkit software (version 0.9.5; https://cnvkit.readthedocs.io/en/latest/). The mean VAF (ratio of the number of variant reads to wild‐type reads) was assessed per patient, and another parameter of ctDNA levels (hGE/mL) was calculated by multiplying the average VAF by the concentration of total ctDNA mass in pg/mL divided by 3.3.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The association between ctDNA levels and tumor burden at baseline measured by the sums of diameters of target lesions for each patient was explored by Pearson correlation coefficients. Discrepancy in clinical outcomes was compared in patients with different EML4‐ALK fusion subtypes. Median OS (defined as the time from the date of first ensartinib treatment to the date of death) was estimated using a Kaplan‒Meier method, and the P value of the log‐rank test was calculated with hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) using the Brookmeyer‐Crowley method. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were carried out using the R packages “survminer” (version 0.4.9) and “survival” (version 3.2‐11) to determine independent factors related to patient prognosis. For continuous variables in statistical analysis, the median value of parameter is widely employed to group samples, along with mean value and quartile. The median value of ctDNA (hGE/mL) were assessed in two subgroups to characterize ctDNA levels at baseline [29]. The median value of freedom from progression was used to demonstrate the associations of prognoses with patterns of ctDNA dynamics. Furthermore, blood‐based tumor mutational burden can serve as a predictor of immunotherpay response, indicating that patients with different survival are characterized by discrepant variant signatures [30]. Additionally, median survival is a critical efficacy index in clinical trials. Therefore, median OS was employed to divide patients into long‐OS and short‐OS groups, and the mutation landscapes of the two subgroups were profiled by the R package “maftools”. For specific mutant genes of long‐OS or short‐OS groups, further, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis was performed using the R package “clusterProfiler”. A P value less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant for all analyses. The final data cut‐off date was August 31, 2022.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patients

A total of 182 patients were enrolled, of whom 180 patients with baseline target lesions were included for OS analysis. The median age was 51.9 years (range, 20.6‐79.9 years). A total of 113 (62.8%) patients had baseline CNS metastases. A total of 168 patients with an assessable blood mutational spectrum were included in the ctDNA analysis.

3.2. Efficacy

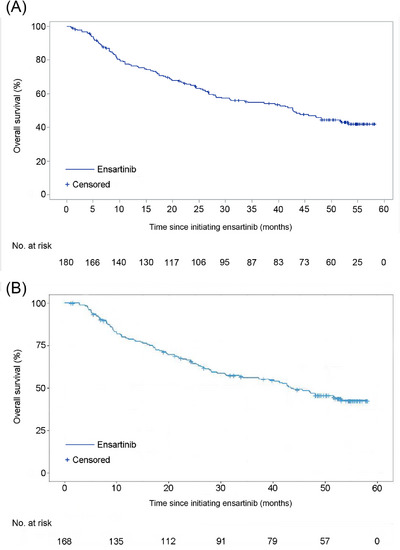

At the final data cut‐off date with a median follow‐up time of 53.2 months, 97 (53.9%) patients had died. The final median OS was 42.8 months (95% CI: 29.3‐53.2 months; Figure 1A). The median OS for patients with baseline CNS metastases (n = 113) was 43.0 months (95% CI: 28.1 months‐not reached [NR]) compared with 41.8 months (95% CI: 25.3 months‐NR) in patients without baseline CNS metastases (n = 67). The median OS data for patient subgroups are presented in Table 1. Post‐relapse treatments are listed in Supplementary Table S1, with 127 (70.6%) patients receiving subsequent treatments after relapse. In ctDNA analysis, the median OS of 168 patients was 43.4 months (95% CI: 29.3 months‐NR; Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves of final overall survival for the 180 patients in the whole cohort (A) and 168 patients in the ctDNA analysis (B). Abbreviations: No abbreviations.

TABLE 1.

Subgroup analysis for overall survival.

| Characteristics | Patients (n) | Median OS, months (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 180 | 42.8 (29.3‐53.2) | |

| Age | 0.629 | ||

| <65 years | 163 | 42.8 (28.2‐NR) | |

| ≥65 years | 17 | 40.3 (6.1‐NR) | |

| Sex | 0.467 | ||

| Male | 93 | 41.8 (24.5‐NR) | |

| Female | 87 | 47.0 (28.1‐NR) | |

| ECOG PS | 0.920 | ||

| 0 | 27 | 41.8 (24.5‐NR) | |

| 1‐2 | 153 | 42.8 (28.2‐NR) | |

| CNS metastases | 0.820 | ||

| Yes | 113 | 43.0 (28.1‐NR) | |

| No | 67 | 41.8 (25.3‐NR) | |

| Prior chemotherapy | 0.714 | ||

| Yes | 97 | 41.8 (26.8‐NR) | |

| No | 83 | 48.1 (26.6‐NR) | |

| The best efficacy of first‐line crizotinib a | 0.497 | ||

| CR/PR | 127 | 43.0 (28.2‐NR) | |

| SD/PD | 41 | 30.8 (19.6‐NR) | |

| Post‐relapse treatments | 0.340 | ||

| Yes | 127 | 43.4 (30.8‐NR) | |

| No | 53 | 31.0 (17.1‐NR) |

The efficacy of these 12 patients were unknown because the data were not collected. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CNS, central nervous system; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; NR, not reached; OS, overall survival.

3.3. Mutational differences and enriched pathway analysis between long‐ and short‐OS groups

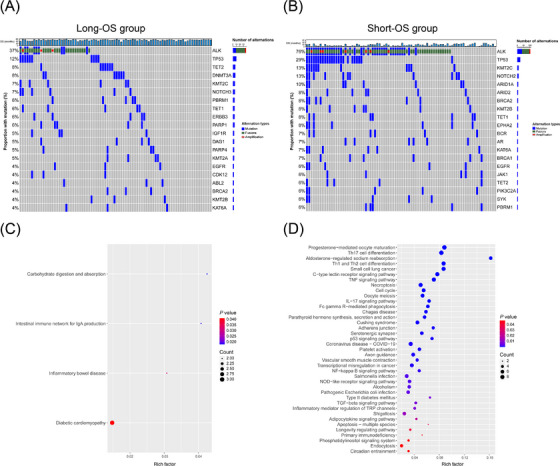

As the median OS in the ctDNA analysis was 43.4 months for 168 patients, these 168 patients were divided into a long‐OS group (≥ median OS) and a short‐OS group (< median OS). Genomic profiles of the top 20 genes with the highest mutation frequencies were visualized for each group. ALK alterations (fusion or mutation) were the most common, followed by TP53 mutations, regardless of OS time (Figure 2A‐B). Although variations occurred in almost the same set of genes, more alterations and higher mutation frequencies were detected in the short‐OS group than in the long‐OS group, indicating a higher mutation burden (Figure 2A‐B). Except for genes shared by the two groups, some mutated genes were detected only in one group. For these genes, specific to the long‐OS or short‐OS group, KEGG enrichment analysis was performed and suggested more cancer‐related pathways enriched in the short‐OS group, including T helper 17 (Th17) cell differentiation, small cell lung cancer, p53 signaling pathway, and transcriptional misregulation in cancer, compared to the long‐OS group (Figure 2C‐D).

FIGURE 2.

The genomic profiles and enriched pathway analysis between patients with long and short overall survival time. The landscape of somatic alterations in patients with long (A) or short (B) overall survival time. Pathways significantly enriched by mutant genes specific to long (C) and short (D) overall survival time. Abbreviations: ABL2, abelson‐related gene; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; AR, androgen receptor; ARID1A, AT‐rich interaction domain 1A; ARID2, AT‐rich interaction domain 2; BCR, B cell receptor; BRCA1/2, breast cancer susceptibility gene 1/2; CDK12, cyclin‐dependent kinases 12; DAG1, dystroglycan 1; DNMT3A, DNA methyltransferase 3A; EGFR, epidermal growth factor rescepor; EPHA2, ephrin type‐A receptor 2; ERBB3, Erb‐B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 3; IGF1R, insulin‐like growth factor‐1 receptor; JAK1, Janus kinase 1; KAT6A, K(lysine) acetyltransferase 6A; KMT2A/2B/2C, lysine (K)‐specific methyltransferase 2A/2B/2C; NOTCH2/3, notch homolog protein 2/3; OS, overall survival; PARP1/4, poly (ADP‐ribose) polymerase 1/4; PBRM1, polybromo 1; PIK3C2A, phosphatidylinositol‐4‐phosphate 3‐kinase, catalytic subunit type 2 alpha; SYK, spleen tyrosine kinase; TET1/2, ten‐eleven translocation 1/2; Th17, T helper 17; TP53, tumor protein 53.

3.4. Baseline alterations and clinical outcomes

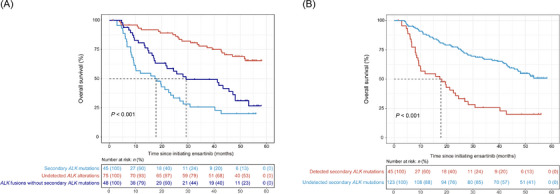

At baseline, ALK alterations were detected in 93 patients, including 48 patients harboring ALK fusions without secondary ALK mutations and 45 patients harboring secondary ALK mutations (regardless of the ALK fusions; Figure 3A). The patients with undetected ALK alterations at baseline (n = 75) had prolonged OS compared with those with ALK fusions or secondary ALK mutations (median NR [95% CI: NR‐NR] vs. 29.3 months [95% CI: 21.6‐48.1 months] vs. 17.8 months [95% CI: 9.4‐26.9 months], HR: 0.6, 95% CI: 0.4‐1.0, P < 0.001; Figure 3A). Furthermore, patients with detected secondary ALK mutations at baseline showed significantly shorter OS than those with undetected secondary ALK mutations (median 17.8 months [95% CI: 9.4‐26.9 months] vs. NR [95% CI: 47.0 months‐NR], HR: 3.0, 95% CI: 1.9‐4.6, P < 0.001; Figure 3B). Additionally, the survival status of patients characterized by different ALK mutation types was compared. Although the difference was not significant, patients harboring F1174L, L1196M, G1269A and C1156Y seemed to have better prognoses (Supplementary Figure S1).

FIGURE 3.

Prognoses of patients with disparate ALK fusions/mutations (A) and secondary ALK mutations at baseline (B). The dotted lines refer to the median survival time. Abbreviation: ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase.

Considering the effect, we further investigated the effects of TP53 status and EML4‐ALK variants on OS. When focusing on the TP53 status of 168 patients at baseline, we found that patients with TP53 mutations (n = 34) had shorter OS than those without TP53 mutations (n = 134) (median 14.8 months, [95% CI: 9.3‐40.3 months] vs. NR [95% CI 44.0 months‐NR], HR: 3.1, 95% CI 2.0‐4.9, P < 0.001; Supplementary Figure S2A). For 93 ALK‐positive samples pre‐ensartinib, 29 (31.2%) harbored concurrent TP53 mutations, who showed shorter OS than those without TP53 mutations (median 9.4 months [95% CI: 8.3‐24.5 months] vs. 28.2 months [95% CI: 19.6‐48.1 months], HR: 2.3, 95% CI: 1.4‐3.9, P < 0.001; Supplementary Figure S2B). A total of 5 EML4‐ALK variants were detected, including variant 1 (n = 34), variant 2 (n = 12), variant 3 (n = 26), variant 5’ (n = 4) and variant 5a (n = 2). However, no significant difference in OS was found between patients with these 5 EML4‐ALK variants (median 18.2 months [95% CI: 14.7‐45.7 months] vs. 42.7 months [95% CI: 21.6 months‐NR] vs. 23.6 months [95% CI: 11.0‐48.1 months] vs. 10.6 months [95% CI: 8.1 months‐NR] vs. 25.5 months [95% CI: 2.9 months‐NR], P = 0.470; Supplementary Figure S3). Multivariate Cox regression modeling identified the presence of hGE, ALK mutation and TP53 mutation at baseline as independent negative prognostic factors for OS (Supplementary Figure S4).

To further explore the influence of other important genes on clinical outcomes, we divided the 168 patients into three groups based on the type of mutant genes detected, including the oncogene mutations group, tumor suppressor gene mutations group, and the no tumor suppressor or oncogene mutations group. In 24 patients harboring oncogene mutations, mutations occurred in genes related to bypass signaling pathways, such as mesenchymal epithelial transition (MET), kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS), epidermal growth factor recepor (EGFR), Erb‐B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (ERBB2), tyrosine protein kinase (KIT), phosphatidylinositol‐4, 5‐bisphosphate 3‐kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA) and rearranged during transfection (RET). In 38 patients with tumor suppressor gene mutations, mutations were found, including TP53, retinoblastoma susceptibility gene (RB1), breast cancer susceptibility gene 1 (BRCA1), breast cancer susceptibility gene 2 (BRCA2), mut‐S homolog 6 (MSH6) and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) (Supplementary Table S2). The group with no mutations detected in oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes had significantly longer OS than the other two groups (P < 0.001; Supplementary Figure S5).

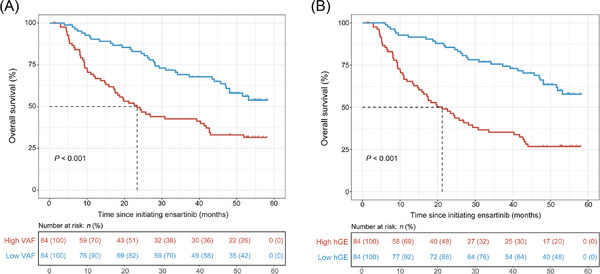

3.5. Prognostic value of ctDNA levels at baseline

Given the possible association of ctDNA level with tumor mutation burden, an analysis of ctDNA quantification was performed. With the available VAF for each mutated gene, the average value of multiple genes for each sample was assessed, and the median VAF (0.0049) of all patients was further utilized for grouping. Overall, patients with higher VAF at baseline presented a shorter OS trend than those with lower VAF at baseline (median 23.4 months [95% CI: 17.4‐41.8 months] vs. NR [95% CI: 48.1 months‐NR], HR: 2.3, 95% CI: 1.5‐3.5, P < 0.001; Figure 4A). In addition, we obtained data on hGE/mL of plasma for each patient. Using a median value of 1,474.788 hGE/mL, patients with higher levels showed significantly inferior OS than those with lower levels (median 21.2 months [95% CI: 15.8‐30.8 months] vs. NR [95% CI: 51.9 months‐NR], HR: 3.0, 95% CI: 2.0‐4.7, P < 0.001; Figure 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Overall survival of patients with different ctDNA levels at baseline assessed by VAF (A) and hGE per milliliter of plasma (B). The dotted lines refer to the median survival time. Abbreviations: hGE, haploid genome equivalents; VAF, variant allele frequency.

3.6. Dynamic analysis of ctDNA

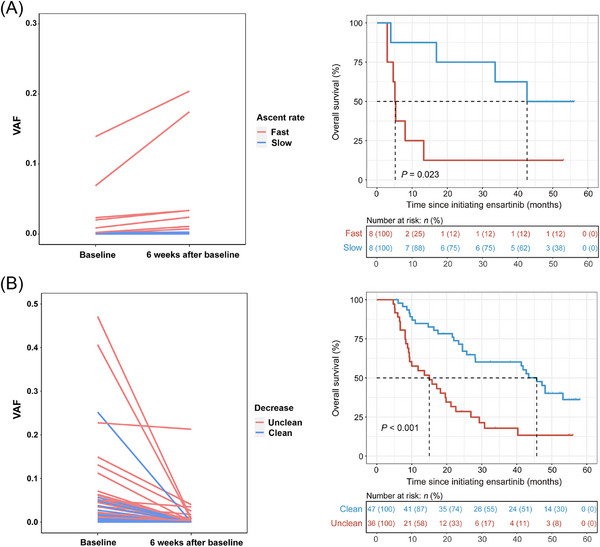

We then investigated the effect of treatment on ctDNA dynamics and its predictive value. Plasma ctDNA was monitored from baseline until the first follow‐up at 6 weeks after ensartinib therapy. Patients with increased ctDNA levels (n = 16) showed a significantly worse OS trend than those with decreased ctDNA levels (n = 149) (median 15.1 months [95% CI: 5.1 months‐NR] vs. 47.0 months [95% CI: 37.3 months‐NR], HR: 1.9, 95% CI: 1.0‐3.5, P = 0.048; Supplementary Figure S6). Among 16 patients with increased ctDNA levels, 8 with a fast ascent rate showed remarkably shorter OS than 8 with a slow ascent rate (median 5.2 months [95% CI: 4.6 months‐NR] vs. 42.7 months [95% CI: 33.6 months‐NR], HR: 4.2, 95% CI: 1.1‐15.0, P = 0.023; Figure 5A). Among those with decreased ctDNA levels, patients with ctDNA clearance at 6 weeks (n = 47) had dramatically longer OS than those without clearance (n = 36) (median 45.7 months [95% CI: 28.1 months‐NR] vs. 15.0 months [95% CI: 9.3‐22.6 months], HR: 0.4, 95% CI: 0.2‐0.6, P < 0.001; Figure 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Comparison of clinical outcomes among patients with several patterns of ctDNA changes, incorporating groups of increased (A) and declined (B) ctDNA levels from baseline to 6 weeks after ensartinib treatment. Abbreviations: ctDNA, circulating tumour DNA; VAF, variant allele frequency.

3.7. Baseline tumor burden as a predictor of OS

We found that the total diameters of baseline target lesions were significantly related to the average ctDNA VAF (Spearman r = 0.259, P < 0.01; Pearson r = 0.261, P < 0.01; Supplementary Figure S7A‐B). With the median value (41.25 mm) of total target lesion diameters at baseline as the cut‐off, patients with long diameters had poorer OS than those with short diameters (median 31.0 months [95% CI: 21.6‐45.7 months] vs. NR [95% CI: 44.0 months‐NR], HR: 1.7, 95% CI: 1.1‐2.6, P = 0.01; Supplementary Figure S8), suggesting the prognostic value of baseline sums of diameters of target lesions.

4. DISCUSSION

Consistent with the phase II study [9], this final analysis provides further evidence that ensartinib has high efficacy in the second‐line setting in patients with ALK‐positive NSCLC who are resistant to crizotinib. The median OS was 42.8 months, and the median OS was similar in patients with or without baseline CNS metastases.

OS data in the second‐line setting have also been published for other ALK TKIs. In the ALTA‐2 study, the median OS for brigatinib was 25.9 months (95% CI: 18.2‐45.8 months) at 90 mg once daily (n = 112) and 40.6 months (95% CI: 32.5 months‐NR) at 180 mg once daily (n = 110) in patients with ALK‐positive NSCLC previously treated with crizotinib [31]. The final median OS for alectinib was 29.1 months (95% CI: 21.3‐39.0 months) in a pooled analysis (NP28673: median 29.2 months; 95% CI: 21.5‐44.4 months; NP28761: median 27.9 months; 95% CI: 17.2 months‐not evaluable [NE]) [32]. Furthermore, in the ALUR study, the median OS was 27.8 months (95% CI: 18.2 months‐NE) with alectinib and NE (95% CI: 8.6 months‐NE) with chemotherapy, which did not show an OS benefit. The possible reason may be the high rate of crossover from chemotherapy to alectinib (86.5%) [33]. In the present study, the median OS for ensartinib was 42.8 months (95% CI: 29.3‐53.2 months), which was comparable to that reported for high‐dose brigatinib and longer than that for alectinib. However, cross‐trial comparisons are difficult due to the different study design and lack of head‐to‐head conparison. Lorlatinib has also been investigated in the second‐line setting in patients with ALK‐positive NSCLC. The ORR was 70% in patients previously treated with crizotinib, regardless of the combination with chemotherapy (n = 59) [10]. OS data for lorlatinib have not yet been reported.

Several studies have shown the potential OS benefit of sequential use of a second‐generation ALK TKI post crizotinib; however, these were retrospective studies [34, 35, 36]. Furthermore, several studies have supported the use of some second‐generation ALK inhibitors after failure of a second‐generation ALK TKI. The efficacy of ceritinib was found to be limited in patients who had progressed on alectinib, with a median PFS of 3.7 months, while brigatinib (median PFS: 7.3 months) or lorlatinib (median PFS: 5.5 months) had efficacy post alectinib [37, 38, 39]. In a retrospective study, brigatinib showed limited efficacy (median PFS: 4.4 months) in patients with alectinib‐refractory ALK‐rearranged NSCLC [40]. Ensartinib was also assessed in an alectinib‐refractory setting with an ORR of 23% and a disease control rate (DCR) of 50% [41]. Indeed, previous studies have suggested that the benefit of initial use of a second‐generation ALK TKI may be superior to sequential treatment with first‐generation followed by second‐generation TKIs [1, 5, 11‐13]. In addition, some advocate using second‐generation ALK TKIs due to their favorable toxicity profile while retaining lorlatinib, the only third‐generation ALK TKI, for salvage treatment. It is also important to note that platinum doublet chemotherapy is a valid treatment option for patients with ALK translocation [42]. In this study, the OS was longest compared with other ALK TKIs in the second‐line setting to date. Administration of other next‐generation ALK TKIs occurred in 102 (56.7%) patients after ensartinib discontinuation. These findings support that ensartinib can serve as an initial therapy, followed by other ALK TKIs when progression on ensartinib occurs.

EML4‐ALK variant 1 and variant 3 are the two most common variants, followed by variant 2 and variant 5′ [43]. EML4‐ALK variants can be broadly divided into the “long” variants (variant 1, variant 2, variant 5′, variant 7 and variant 8 which contain tandem atypical β‐propeller EML [TAPE] domain) and “short” (variant 3a/b and variant 5a/b which lack TAPE domain), resulting in differential clinical outcomes to ALK TKIs [43]. Variant 3 led to a shorter PFS than variant 1 or variant 2 with crizotinib, alectinib, and ceritinib [44, 45]. The ALTA‐1L trial evaluated the efficacy of each variant with brigatinib, and similarly, variant 3 led to poorer outcomes than variant 1 [46]. Furthermore, patients with variant 3 or variant 5 who received crizotinib displayed an inferior PFS compared to those with other variants [47]. In our study, patients with 5 variants had a similar OS, suggesting that ensartinib had a robust efficacy regardless of variants. Higher drug sensitivity to lorlatinib of those with variant 3 than variant 1 was observed. The possible reason may be that lorlatinib retain potent activity against ALK mutations, including G1202R, and variant 3 was significantly associated with the development of ALK resistance mutations, particularly G1202R [48]. G1202R is the most common secondary ALK mutation post ceritinib, alectinib or brigatinib treatment [49] but was not the most common ALK mutation in ensartinib‐resistant patients, with G1269A (6.6%) being identified more often than G1202R (2.8%) among patients with secondary ALK mutations post second‐line ensartinib [16]. On‐target resistance to the third‐generation ALK inhibitor lorlatinib is primarily mediated by compound ALK mutations. Interestingly, some compound mutations that cause resistance to lorlatinib result in resensitization to first‐ or second‐generation ALK TKIs [50, 51]. Furthermore, tumors can switch to ALK‐independent growth through the activation of bypass signaling pathways, including EGFR, cMET, and AXL. Co‐occurrence of EML4‐ALK with TP53 mutation can serve as a resistance mechanism by promoting cell survival and other tumor‐related adaptations. In our study, the incidence of NGS‐identified concomitant TP53 mutations with ALK rearrangement was 31.2%, which was comparable to the 20‐29% reported previously [52, 53]. Concomitant TP53 mutations are predictive of poor survival outcomes in oncogene‐driven NSCLC, including EGFR‐positive NSCLC and ALK‐positive NSCLC [54, 55]. Additionally, we observed that patients with concomitant TP53 mutations had a shorter OS than patients without concomitant TP53 mutations (median, 9.4 vs. 28.2 months, P < 0.001). Therefore, overcoming TP53 mutations remains an unmet need for patients with ALK‐positive NSCLC. In addition, KEGG enrichment analysis revealed more enrichment of cancer‐related pathways, including Th17 cell differentiation, p53 signaling pathway, and transcriptional misregulation in cancer in the short‐OS group. This result suggests that the poorer survival time of patients may be related to the abnormal Th17 cell‐mediated immune pathway and p53 signaling pathway.

This study collectively found that a lower ctDNA level at baseline, a slow growth rate and ctDNA clearance from pre‐ensartinib to 6 weeks after baseline were related to superior survival, demonstrating the predictive value of ctDNA. We noted that only 16 patients showed increased ctDNA levels, possibly due to the clinical benefits of ensartinib for ALK‐positive NSCLC. Although the size of this population is limited, our findings provide some insights into disease monitoring. Recently, a retrospective study of ALK‐positive NSCLC revealed that patients with detected mutations at baseline had faster tumor progression than ctDNA‐negative patients. Furthermore, radiographic progression was predicted by elevated ctDNA levels during molecular motoring [56]. Decreased alterations correlated positively with better clinical response in ALK rearrangement NSCLC [18]. Of note, associations of survival with ctDNA levels at baseline in ALK‐positive patients treated with ensartinib have been proposed. Unfortunately, the cohort size was relatively limited, with longitudinal samples from only 11 patients involved in ctDNA analysis, resulting in a lack of evaluation of ctDNA changes [57].

To further investigate clinical risk factors, we detected the relationship between baseline sums of diameters of target lesions and OS, as well as the relationship between baseline ctDNA level and OS. The results showed that patients with larger target lesion diameters had poorer OS and that patients with higher baseline ctDNA levels (based on either VAF or hGE) had shorter OS, suggesting that baseline sums of diameters of target lesions may be prognostic factors. The superior efficacy of ensartinib to crizotinib in advanced ALK‐positive NSCLC can be partially explained by its favorable CNS activity. In the global eXalt3 study, the median PFS among patients with brain metastases at baseline was 11.8 months (95% CI: 5.5 months‐NR) in the ensartinib group and 7.5 months (95% CI: 5.5‐9.3 months) in the crizotinib group (HR: 0.55, 95% CI: 0.30‐1.01; P = 0.05) [12]. Similar findings were reported in a phase II study [9]. In our study, the median OS was similar in patients with and without baseline CNS metastases, suggesting favorable efficacy regardless of CNS metastases.

One of the limitations of this study was the small sample size. In addition, the lack of a comparator arm in this phase II single‐arm study is also a limitation; however, the phase III eXalt3 study has provided data regarding the efficacy of ensartinib versus crizotinib in the first‐line setting [12]. Finally, this analysis does not provide information on the role of various ALK mutations in response to ensartinib, though resistance mechanisms to ensartinib were preliminarily explored in our previous study [16].

5. CONCLUSIONS

The final results from our phase II study confirm the robust clinical efficacy of ensartinib in crizotinib‐pretreated patients with advanced ALK‐positive NSCLC. The perspective of ctDNA use in prognostic, diagnostic and predictive testing using NSCLC‐associated biomarkers is expected to become a reality in routine clinical procedures in the near future.

DECLARATIONS

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jianya Zhou, Jiangying Zhou and Li Zhang contributed to the conceptualization. Jing Zheng, Yunpeng Yang, Jie Huang, Jifeng Feng, Wu Zhuang, Jianhua Chen, Jun Zhao, Wei Zhong, Yanqiu Zhao, Yiping Zhang, Yong Song, Yi Hu, Zhuang Yu, Youling Gong, Yuan Chen, Feng Ye, Shucai Zhang, Lejie Cao, Yun Fan, Gang Wu, Yubiao Guo, Chengzhi Zhou, Kewei Ma, Jian Fang, Weineng Feng, Yunpeng Liu, Zhendong Zheng, Gaofeng Li, Huijie Wang, Shundong Cang, Ning Wu, Wei Song, Xiaoqing Liu and Shijun Zhao contributed to resources, data curation and analysis. Lieming Ding, Giovanni Selvaggi, Yang Wang contributed to supervision and project administration. Tao Wang, Shanshan Xiao, Qian Wang, Zhilin Shen contributed to methodology and data analysis. Jing Zheng, Tao Wang and Zhilin Shen contributed to manuscript drafting. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. The corresponding author takes full responsibility of the accuracy of all data and description in this work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Lieming Ding, Yang Wang, and Zhilin Shen are employees of Betta Pharmaceuticals. Tao Wang, Shanshan Xiao, and Qian Wang are employees of Hangzhou Repugene Technology. Giovanni Selvaggi is an employee of X‐covery Holdings. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The Ethics Committee Review Board approved the study protocol at Sun Yat‐sen University Cancer Center, State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China, Collaborative Innovation Center for Cancer Medicine (A2017‐014‐01) and each participating institution, and all patients provided written informed consent. The studies were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

Supporting information

Supporting informaton

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We appreciate all the sites that contributed to recruitment, the patients and their families who participated in this study. This study was supported by Betta Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd.

Zheng J, Wang T, Yang Y, Huang J, Feng J, Zhuang W, et al. Updated overall survival and circulating tumor DNA analysis of ensartinib for crizotinib‐refractory ALK‐positive NSCLC from a phase II study. Cancer Commun. 2024;44:455–468. 10.1002/cac2.12524

Jing Zheng and Tao Wang contributed equally to this work.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated and analyzed in the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Camidge DR, Kim HR, Ahn MJ, Yang JC, Han JY, Lee JS, et al. Brigatinib versus Crizotinib in ALK‐Positive Non‐Small‐Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(21):2027–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gainor JF, Varghese AM, Ou SH, Kabraji S, Awad MM, Katayama R, et al. ALK rearrangements are mutually exclusive with mutations in EGFR or KRAS: an analysis of 1,683 patients with non‐small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(15):4273–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wu YL, Lu S, Lu Y, Zhou J, Shi YK, Sriuranpong V, et al. Results of PROFILE 1029, a Phase III Comparison of First‐Line Crizotinib versus Chemotherapy in East Asian Patients with ALK‐Positive Advanced Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(10):1539–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, Wu YL, Nakagawa K, Mekhail T, et al. First‐line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK‐positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(23):2167–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Peters S, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Gadgeel S, Ahn JS, Kim DW, et al. Alectinib versus Crizotinib in Untreated ALK‐Positive Non‐Small‐Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(9):829–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yang JC, Ou SI, De Petris L, Gadgeel S, Gandhi L, Kim DW, et al. Pooled Systemic Efficacy and Safety Data from the Pivotal Phase II Studies (NP28673 and NP28761) of Alectinib in ALK‐positive Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(10):1552–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shaw AT, Kim DW, Mehra R, Tan DS, Felip E, Chow LQ, et al. Ceritinib in ALK‐rearranged non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(13):1189–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim DW, Tiseo M, Ahn MJ, Reckamp KL, Hansen KH, Kim SW, et al. Brigatinib in Patients With Crizotinib‐Refractory Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase‐Positive Non‐Small‐Cell Lung Cancer: A Randomized, Multicenter Phase II Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(22):2490–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang Y, Zhou J, Zhou J, Feng J, Zhuang W, Chen J, et al. Efficacy, safety, and biomarker analysis of ensartinib in crizotinib‐resistant, ALK‐positive non‐small‐cell lung cancer: a multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(1):45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Solomon BJ, Besse B, Bauer TM, Felip E, Soo RA, Camidge DR, et al. Lorlatinib in patients with ALK‐positive non‐small‐cell lung cancer: results from a global phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(12):1654–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Soria JC, Tan DSW, Chiari R, Wu YL, Paz‐Ares L, Wolf J, et al. First‐line ceritinib versus platinum‐based chemotherapy in advanced ALK‐rearranged non‐small‐cell lung cancer (ASCEND‐4): a randomised, open‐label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2017;389(10072):917–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Horn L, Wang Z, Wu G, Poddubskaya E, Mok T, Reck M, et al. Ensartinib vs Crizotinib for Patients With Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase‐Positive Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(11):1617–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shaw AT, Bauer TM, de Marinis F, Felip E, Goto Y, Liu G, et al. First‐Line Lorlatinib or Crizotinib in Advanced ALK‐Positive Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(21):2018–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lin JJ, Riely GJ, Shaw AT. Targeting ALK: Precision Medicine Takes on Drug Resistance. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(2):137–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shaurova T, Yan L, Su Y, Rich LJ, Vincent‐Chong VK, Calkins H, et al. A nanotherapeutic strategy to target drug‐tolerant cells and overcome EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance in lung cancer. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2023;43(4):503–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yang Y, Huang J, Wang T, Zhou J, Zheng J, Feng J, et al. Decoding the Evolutionary Response to Ensartinib in Patients With ALK‐Positive NSCLC by Dynamic Circulating Tumor DNA Sequencing. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(5):827–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Esposito Abate R, Frezzetti D, Maiello MR, Gallo M, Camerlingo R, De Luca A, et al. Next Generation Sequencing‐Based Profiling of Cell Free DNA in Patients with Advanced Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer: Advantages and Pitfalls. Cancers. 2020;12(12):3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dagogo‐Jack I, Brannon AR, Ferris LA, Campbell CD, Lin JJ, Schultz KR, et al. Tracking the Evolution of Resistance to ALK Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors through Longitudinal Analysis of Circulating Tumor DNA. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2018:PO1700160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mondaca S, Lebow ES, Namakydoust A, Razavi P, Reis‐Filho JS, Shen R, et al. Clinical utility of next‐generation sequencing‐based ctDNA testing for common and novel ALK fusions. Lung Cancer. 2021;159:66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lawrence MN, Tamen RM, Martinez P, Sable‐Hunt A, Addario T, Barbour P, et al. SPACEWALK: A Remote Participation Study of ALK Resistance Leveraging Plasma Cell‐Free DNA Genotyping. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2021;2(4):100151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin YT, Chiang CL, Hung JY, Lee MH, Su WC, Wu SY, et al. Resistance profiles of anaplastic lymphoma kinase tyrosine kinase inhibitors in advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer: a multicenter study using targeted next‐generation sequencing. Eur J Cancer. 2021;156:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bordi P, Tiseo M, Rofi E, Petrini I, Restante G, Danesi R, et al. Detection of ALK and KRAS Mutations in Circulating Tumor DNA of Patients With Advanced ALK‐Positive NSCLC With Disease Progression During Crizotinib Treatment. Clin Lung Cancer. 2017;18(6):692–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Esposito Abate R, Frezzetti D, Maiello MR, Gallo M, Camerlingo R, De Luca A, et al. Next Generation Sequencing‐Based Profiling of Cell Free DNA in Patients with Advanced Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer: Advantages and Pitfalls. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(12):3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hua G, Zhang X, Zhang M, Wang Q, Chen X, Yu R, et al. Real‐world circulating tumor DNA analysis depicts resistance mechanism and clonal evolution in ALK inhibitor‐treated lung adenocarcinoma patients. ESMO Open. 2022;7(1):100337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang JT, Liu SY, Gao W, Liu SM, Yan HH, Ji L, et al. Longitudinal Undetectable Molecular Residual Disease Defines Potentially Cured Population in Localized Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2022;12(7):1690–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Henriksen TV, Tarazona N, Frydendahl A, Reinert T, Gimeno‐Valiente F, Carbonell‐Asins JA, et al. Circulating Tumor DNA in Stage III Colorectal Cancer, beyond Minimal Residual Disease Detection, toward Assessment of Adjuvant Therapy Efficacy and Clinical Behavior of Recurrences. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28(3):507–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ren S, Chen J, Xu X, Jiang T, Cheng Y, Chen G, et al. Camrelizumab Plus Carboplatin and Paclitaxel as First‐Line Treatment for Advanced Squamous NSCLC (CameL‐Sq): A Phase 3 Trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2022;17(4):544–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Layer RM, Chiang C, Quinlan AR, Hall IM. LUMPY: a probabilistic framework for structural variant discovery. Genome Biology. 2014;15(6):R84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moding EJ, Liu Y, Nabet BY, Chabon JJ, Chaudhuri AA, Hui AB, et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Dynamics Predict Benefit from Consolidation Immunotherapy in Locally Advanced Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer. Nat Cancer. 2020;1(2):176–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nabet BY, Esfahani MS, Moding EJ, Hamilton EG, Chabon JJ, Rizvi H, et al. Noninvasive Early Identification of Therapeutic Benefit from Immune Checkpoint Inhibition. Cell. 2020;183(2):363–76.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gettinger SN, Huber RM, Kim DW, Bazhenova L, Camidge DR. Brigatinib (BRG) in ALK+ crizotinib (CRZ)‐refractory non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Final results of the phase 1/2 and phase 2 (ALTA) trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2021;39(15_suppl):9071. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ou SI, Gadgeel SM, Barlesi F, Yang JC, De Petris L, Kim DW, et al. Pooled overall survival and safety data from the pivotal phase II studies (NP28673 and NP28761) of alectinib in ALK‐positive non‐small‐cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2020;139:22–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wolf J, Helland Å, Oh IJ, Migliorino MR, Dziadziuszko R, Wrona A, et al. Final efficacy and safety data, and exploratory molecular profiling from the phase III ALUR study of alectinib versus chemotherapy in crizotinib‐pretreated ALK‐positive non‐small‐cell lung cancer. ESMO Open. 2022;7(1):100333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gainor JF, Tan DS, De Pas T, Solomon BJ, Ahmad A, Lazzari C, et al. Progression‐Free and Overall Survival in ALK‐Positive NSCLC Patients Treated with Sequential Crizotinib and Ceritinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(12):2745–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chiari R, Metro G, Iacono D, Bellezza G, Rebonato A, Dubini A, et al. Clinical impact of sequential treatment with ALK‐TKIs in patients with advanced ALK‐positive non‐small cell lung cancer: Results of a multicenter analysis. Lung Cancer. 2015;90(2):255–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ito K, Hataji O, Kobayashi H, Fujiwara A, Yoshida M, D'Alessandro‐Gabazza CN, et al. Sequential Therapy with Crizotinib and Alectinib in ALK‐Rearranged Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer‐A Multicenter Retrospective Study. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(2):390–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hida T, Seto T, Horinouchi H, Maemondo M, Takeda M, Hotta K, et al. Phase II study of ceritinib in alectinib‐pretreated patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase‐rearranged metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer in Japan: ASCEND‐9. Cancer Sci. 2018;109(9):2863–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Borghaei H, Gettinger S, Vokes EE, Chow LQM, Burgio MA, de Castro Carpeno J, et al. Five‐Year Outcomes From the Randomized, Phase III Trials CheckMate 017 and 057: Nivolumab Versus Docetaxel in Previously Treated Non‐Small‐Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(7):723–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nishio M, Yoshida T, Kumagai T, Hida T, Toyozawa R, Shimokawaji T, et al. Brigatinib in Japanese Patients With ALK‐Positive NSCLC Previously Treated With Alectinib and Other Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: Outcomes of the Phase 2 J‐ALTA Trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(3):452–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lin JJ, Zhu VW, Schoenfeld AJ, Yeap BY, Saxena A, Ferris LA, et al. Brigatinib in Patients With Alectinib‐Refractory ALK‐Positive NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(10):1530–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Horn L, Leal T, Oxnard G, Wakelee H, Blumenschein G, Waqar S, et al. OA03. 08 Activity of ensartinib after second generation anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI): topic: medical oncology. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(11):S1556. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lin JJ, Schoenfeld AJ, Zhu VW, Yeap BY, Chin E, Rooney M, et al. Efficacy of Platinum/Pemetrexed Combination Chemotherapy in ALK‐Positive NSCLC Refractory to Second‐Generation ALK Inhibitors. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(2):258–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang SS, Nagasaka M, Zhu VW, Ou SI. Going beneath the tip of the iceberg. Identifying and understanding EML4‐ALK variants and TP53 mutations to optimize treatment of ALK fusion positive (ALK+) NSCLC. Lung Cancer. 2021;158:126–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Woo CG, Seo S, Kim SW, Jang SJ, Park KS, Song JY, et al. Differential protein stability and clinical responses of EML4‐ALK fusion variants to various ALK inhibitors in advanced ALK‐rearranged non‐small cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(4):791–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Christopoulos P, Endris V, Bozorgmehr F, Elsayed M, Kirchner M, Ristau J, et al. EML4‐ALK fusion variant V3 is a high‐risk feature conferring accelerated metastatic spread, early treatment failure and worse overall survival in ALK(+) non‐small cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2018;142(12):2589–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Camidge DR, Kim HR, Ahn MJ, Yang JCH, Han JY, Hochmair MJ, et al. Brigatinib Versus Crizotinib in ALK Inhibitor‐Naive Advanced ALK‐Positive NSCLC: Final Results of Phase 3 ALTA‐1L Trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(12):2091–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Su Y, Long X, Song Y, Chen P, Li S, Yang H, et al. Distribution of ALK Fusion Variants and Correlation with Clinical Outcomes in Chinese Patients with Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Crizotinib. Target Oncol. 2019;14(2):159–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lin JJ, Zhu VW, Yoda S, Yeap BY, Schrock AB, Dagogo‐Jack I, et al. Impact of EML4‐ALK Variant on Resistance Mechanisms and Clinical Outcomes in ALK‐Positive Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(12):1199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gainor JF, Dardaei L, Yoda S, Friboulet L, Leshchiner I, Katayama R, et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Resistance to First‐ and Second‐Generation ALK Inhibitors in ALK‐Rearranged Lung Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(10):1118–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shaw AT, Friboulet L, Leshchiner I, Gainor JF, Bergqvist S, Brooun A, et al. Resensitization to Crizotinib by the Lorlatinib ALK Resistance Mutation L1198F. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(1):54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Okada K, Araki M, Sakashita T, Ma B, Kanada R, Yanagitani N, et al. Prediction of ALK mutations mediating ALK‐TKIs resistance and drug re‐purposing to overcome the resistance. EBioMedicine. 2019;41:105–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Li M, Hou X, Zhou C, Feng W, Jiang G, Long H, et al. Prevalence and Clinical Impact of Concomitant Mutations in Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase Rearrangement Advanced Non‐small‐Cell Lung Cancer (Guangdong Association of Thoracic Oncology Study 1055). Front Oncol. 2020;10:1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Christopoulos P, Kirchner M, Bozorgmehr F, Endris V, Elsayed M, Budczies J, et al. Identification of a highly lethal V3(+) TP53(+) subset in ALK(+) lung adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(1):190–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kron A, Alidousty C, Scheffler M, Merkelbach‐Bruse S, Seidel D, Riedel R, et al. Impact of TP53 mutation status on systemic treatment outcome in ALK‐rearranged non‐small‐cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(10):2068–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Frost N, Christopoulos P, Kauffmann‐Guerrero D, Stratmann J, Riedel R, Schaefer M, et al. Lorlatinib in pretreated ALK‐ or ROS1‐positive lung cancer and impact of TP53 co‐mutations: results from the German early access program. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2021;13:1758835920980558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Angeles AK, Christopoulos P, Yuan Z, Bauer S, Janke F, Ogrodnik SJ, et al. Early identification of disease progression in ALK‐rearranged lung cancer using circulating tumor DNA analysis. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2021;5(1):100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Horn L, Whisenant JG, Wakelee H, Reckamp KL, Qiao H, Leal TA, et al. Monitoring Therapeutic Response and Resistance: Analysis of Circulating Tumor DNA in Patients With ALK+ Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(11):1901–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting informaton

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed in the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.