Abstract

Background:

HIV and other sexually transmissible infections (HIV/STIs) are significant contributors to adolescent girls’ morbidity in the US. Risks for HIV/STIs are increased among adolescent girls involved in the juvenile justice system, and African American adolescent girls comprise nearly 50% of adolescent girls in detention centres. Although HIV prevention programs focus on HIV/STI knowledge, increased knowledge may not be sufficient to reduce sexual risk. The present study examined the interactive effects of HIV/STI knowledge and the importance of being in a relationship (a relationship imperative) on sexual risk behaviours in a sample of detained African American adolescent girls.

Methods:

In all, 188 African American adolescent girls, 13–17 years of age, were recruited from a short-term detention facility in Atlanta, Georgia, and completed assessments on sexual risk behaviours, relationship characteristics, HIV/STI knowledge and several psychosocial risk factors.

Results:

When girls endorsed a relationship imperative, higher HIV/STI knowledge was associated with low partner communication self-efficacy, inconsistent condom use and unprotected sex, when controlling for demographics and self-esteem.

Conclusions:

Young girls with high HIV/STI knowledge may have placed themselves at risk for HIV/STIs given the importance and value they place on being in a relationship. Contextual factors should be considered when developing interventions.

Keywords: condom use, detention, detained, HIV/STI, incarcerated, knowledge

Introduction

HIV and other sexually transmissible infections (HIV/STIs) are significant contributors to adolescent girls’ morbidity in the US.1 Although adolescents, 13–24 years of age, account for 17% of the US population, they accounted for 26% of new HIV infections in 2010, with African Americans accounting for 57% of those new infections.2 In addition, adolescents and young adults, 15–24 years of age, account for approximately 50% of new STI cases each year,3 and it is estimated that 24.1% of adolescent girls, 14–19 years of age, have one of five commonly reported STIs (herpes simplex virus, trichomoniasis, chlamydia, gonorrhoea and human papillomavirus). A national study found that among African American adolescent girls, 14–19 years of age, 44% had at least one STI.4

Risks for HIV/STIs are increased among certain subgroups of this population, such as adolescent girls with a history of juvenile justice detention. Although males represent a larger proportion of the juvenile detention caseload, the number of juvenile detention cases decreased more for males than for females from 2002 to 2011.5 Adolescent females are at a higher risk for several negative health outcomes, including substance use, mental health issues and risky sexual behaviour.6-10 In addition, African American adolescent girls comprise nearly 50% of adolescent girls in detention centers.7,8,11 Previous research has suggested that the context of romantic relationships may also play an important role in HIV/STI risk among adolescent girls involved in juvenile justice. A study of incarcerated adolescent girls, in which the majority were African American, found that 53% had partners who were older by 3 years of more.10 Age differences of 2 or more years between sexual partners are associated with lower perceived relationship power,12 and research indicates that young women who report less relationship power are more likely to report less condom use.13 Furthermore, older partners may link girls to a higher HIV prevalent sexual network.14

Given that adolescent girls involved in the juvenile justice system are at heightened risk for engaging in risky sexual behaviour and STI acquisition,7,8 it is important to gain a better understanding of factors that may be associated with HIV/STI risks among this special population. During the developmental period, adolescents may be concerned with their identity within a romantic relationship, and youth with a stronger relational identity than self-identity may view intimate romantic relationships as imperative to a positive self-concept.15-18 During adolescence, teens are learning how to interact with the opposite sex, methods for initiating and engaging in sexual activity and which sexual activities to participate in.19 Overwhelming societal and peer pressure to be in a romantic relationship,20,21 as well as pressure by potential male partners to engage in sex in order to maintain relationships,22 may heighten the sexual risk behaviours among young women. For example, a previous study found that despite having high HIV/STI knowledge, African American adolescent girls who were afraid their attempts to negotiate condom use would place their relationship in jeopardy, including relationship termination or experiencing emotional or physical abuse, were more likely to report inconsistent condom use with their sexual partners.23

For many, dating in adolescence teaches young women how to bargain for perceived social and emotional benefits of being in a relationship by exchanging sex in order to attain or maintain the coveted ‘girlfriend status’.24 The principle of least interest suggests that if there is a difference in intensity of feelings between partners, the partner with the least interest in the relationship possesses a greater degree of power than the partner with the most interest.25 Hence, young women who endorse the need to always be in a relationship will have less relational power and will be more likely to engage in risky sex practices. A previous study on African American adolescent girls recruited from sexual health clinics found that girls who endorsed a relationship imperative (i.e. ‘having a partner at all times is important’) were more likely to report unprotected sex, anal sex, less power in their relationships, perceived inability to refuse sex, sex while their partner was high on alcohol or drugs and partner abuse.26 These findings suggest that placing a premium on being in a relationship may affect HIV/STI risk behaviour and acquisition among adolescent girls.

Additional factors associated with HIV/STI risk include self-esteem27,28 and knowledge about HIV/STI transmission.29,30 Low self-esteem has been associated with early sexual debut and risky sexual partners among adolescents.31,32 Although behaviour change theory suggests HIV/STI knowledge is required to change risk behaviours,33,34 previous research suggests that context can affect the protective qualities of HIV/STI knowledge.23 For example, despite having high HIV/STI knowledge, adolescent girls may still engage in high-risk behaviour in instances where they fear adverse effects to their relationship.23 The present study examines the elevated risk for HIV/STIs by examining the association between the relative importance adolescent girls involved in juvenile justice place on being in a romantic relationship, their knowledge about HIV/STI transmission (HIV/STI knowledge) and HIV/STI-associated psychosocial factors and sexual risk behaviour. Although previous studies of African American adolescent girls have examined associations between HIV/STI knowledge, fear of adverse consequences when attempting to negotiate condom use and risky sexual behaviour,23 as well as associations between a relationship imperative, psychosocial factors and sexual risk behaviour,26 the present study expands upon these findings. To our knowledge, the present study is one of the first to examine a relationship imperative as a moderator between HIV/STI knowledge and HIV/STI risk behaviour and psychosocial factors, and is the first to examine this relationship among African American girls in the juvenile justice system. The present study asks the important question, ‘When being in a relationship is imperative, will young women knowingly place their sexual health at risk?’.

Methods

Procedures

From March 2011 to February 2012, project recruiters screened African American adolescent girls in a short-term juvenile detention facility in Atlanta, Georgia, for enrolment in a randomised controlled trial of a culturally sensitive HIV prevention program. The present study includes baseline data only. All potentially eligible young women were escorted by detention facility staff for screening by an African American female recruiter. African American girls between the ages of 13 and 17 years at the time of enrolment who reported lifetime vaginal intercourse were eligible to participate. Adolescents who were married, currently pregnant, wards of the State of Georgia or scheduled to be placed in a restricted location upon release (i.e. group home) were excluded from participating. All adolescents recruited into the study provided written informed assent to participate and verbal parental consent was also obtained. Of the 202 eligible adolescents, 188 (93%) agreed to participate. Participants were not compensated for their participation while in the detention facility; however, the larger HIV prevention intervention study35 continued 6 months after release and participants were given up to US$150 for completion of all intervention sessions and study assessments that occurred at baseline and 3 and 6 months post-randomisation. All study protocols were approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board.

Data collection

Data collection occurred at the detention facility and included: (1) a self-collected vaginal swab to detect Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae; a (2) condom skills assessment; and (3) an audio computer-assisted self-interview (A-CASI). The A-CASI assessed sociodemographics, juvenile justice detention history, sexual history, attitudes and HIV/STI prevention-related psychosocial constructs. Sexual behaviours were assessed for the 30 and 90 days preceding baseline assessment.

Measures

Sociodemographics

The A-CASI assessed several sociodemographic characteristics, including age, public assistance (‘In the past 12 months, did you or anyone you live with receive any money or services from any of the following?’; options were welfare, including temporary assistance to needy families, women, infants and children, food stamps and Section 8 housing) and education (‘What is the last grade that you completed in school?’). Juvenile justice detention information for each participant was obtained via self-report (lifetime number of times and number of days each participant had been detained) and detention records (main reason for current detention; i.e. status offence, property offence, personal larceny, weapons, violent offence, violation of probation and non-violent sexual offence]).

Self-esteem

Self-esteem was a covariate and was assessed using a 10-item Likert-type scale36 (Cronbach’s α = 0.84) ranging from 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 4 ‘strongly agree’. Items included ‘I feel that I am a person of worth’ and ‘I feel that I have a number of good qualities’. Negatively worded items were reverse scored; all scores were summed and a median split derived low and high self-esteem categories (median = 30).

Independent variable

The independent variable HIV/STI knowledge was assessed using an 11-item scale,37 using true or false response options. Example items include: ‘Most people who have AIDS look sick’; ‘If a man has an STI he will have noticeable symptoms’; and ‘Birth control pills protect women against the AIDS virus’. Each item was scored for correctness (‘do not know’ was scored as an incorrect response). A total score was calculated, where higher scores indicated greater HIV/STI knowledge. A median split derived low and high HIV/STI knowledge categories (median = 19).

Moderator variable

The moderator variable relationship imperative was assessed by asking participants to rate the degree to which they agreed with the statement ‘Having a partner at all times is important to me’. Response options ranged from 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 4 ‘strongly agree’. Responses were collapsed into two categories: 1 = relationship imperative (agree or strongly agree); and 0 = no relationship imperative (disagree or strongly disagree).

Dependent variables

Partner communication self-efficacy.

This was assessed by a six-item measure38 (Cronbach’s α = 0.79). For each item, participants indicated how difficult it would be to communicate with a partner about sexual health topics and condom use (e.g. ‘How hard is it for you to ask if he has an STD?’) using a four-point scale (i.e. ‘very hard’, ‘hard’, ‘easy’ and ‘very easy’). All scores were summed, and a median split derived low and high partner communication self-efficacy categories (median = 22).

Perceived self-efficacy to refuse sex.

Participants responded to a seven-item Likert-type scale39 (Cronbach’s α = 0.87) that asked questions such as ‘How sure are you that you would be able to say NO to having sex with someone (a) you want to date again? or (b) who refuses to wear a condom?’. Response options ranged from 1 ‘I definitely can say no’ to 4 ‘I definitely can’t say no’. All scores were summed, and a median split derived low and high refusal self-efficacy categories (median = 25).

Relationship power.

This measure was assessed using an 11-item Likert-type scale40 (Cronbach’s α = 0.81) ranging from 1 ‘strongly agree’ to 4 ‘strongly disagree’. Items included ‘Most of the time we do what my partner wants to do’ and ‘I am more committed to our relationship than my partner’. All scores were summed and a median split derived low and high perceived relationship power categories (median =31).

Risky sexual behaviour.

Unprotected vaginal sex and consistent condom use during vaginal, anal or oral sex in the past 30 and 90 days were determined. Both sets of variables were calculated as the proportion of the number of times participants reported using a condom during a sex act to the total number of sex acts reported in a given time frame (past 30 or 90 days). Values less than 1 (i.e. inconsistent condom users) were categorised as having unprotected sex. Values of 1 (i.e. consistent condom users) were categorised as having no unprotected sex. Individuals who did not have vaginal, anal or oral sex in the past 30 or 90 days were also categorised as having no unprotected sex.

Data analysis

Seven separate hierarchical logistic regression analyses were conducted to test the interaction of HIV/STI knowledge and relationship imperative on these HIV/STI-related sexual risk behaviours and psychosocial outcomes. Each outcome was regressed on the covariates (i.e. age, financial assistance and self-esteem) in the first step, HIV/STI knowledge (independent variable) in the second step, relationship imperative (moderator variable) in the third step and the interaction term in the fourth step. A layered Chi-squared was used to produce frequencies for each category of the interaction term for each model. Where appropriate, data are reported as the mean ± s.d.

Results

Descriptive analyses

Among this sample of detained African American adolescent girls, the mean age was 15.3 ± 1.1 years. Most (71.3%) reported having lived in a household that received public financial assistance and most (93%) had completed 9th or 10th grade. Regarding detention history, on average young women had a lifetime detention of 1.5 ± 2.1 times and 26.1 ± 47.5 days. The three most common offences were status offence (57.4%), violent offence (20.2%) and property offence (8.0%). More than half the sample reported unprotected vaginal sex in the past 30 days (53.7%) and 90 days (58.8%), and a smaller percentage reported consistent condom use during vaginal, anal or oral sex in the past 30 days (21.8%) and 90 days (25.5%). Half the sample (49.5%) reported ever engaging in oral sex and 20.7% reported ever engaging in anal sex, of which 38.5% and 46.2% reported engaging in anal sex in the past 30 and 90 days respectively. Approximately one-quarter (26.1%) endorsed a relationship imperative and most young women were somewhat knowledgeable (17.7 ± 2.4) about how HIV/STIs are transmitted.

Hierarchical logistic regression analyses

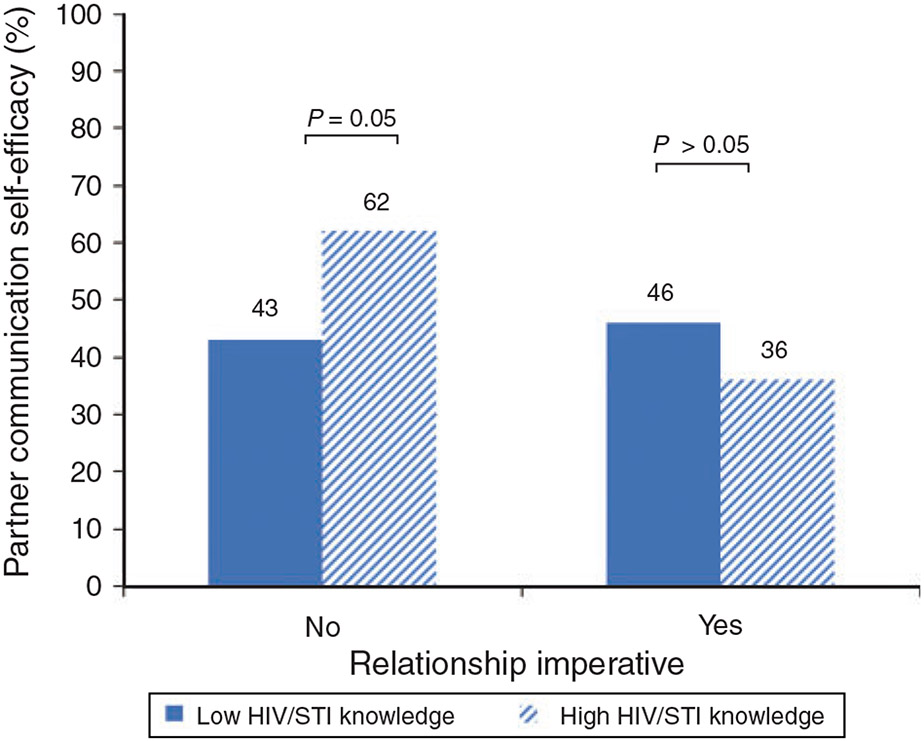

When testing the interaction of HIV/STI knowledge and relationship imperative on HIV/STI-related sexual risk behaviours and psychosocial outcomes, there were four significant interaction effects (Step 4, Table 1) and two main effects (Step 3, Table 1). Post hoc analyses revealed that among detained African American adolescent girls who did not report a relationship imperative, those reporting high HIV/STI knowledge were more likely than those reporting low HIV/STI knowledge to report partner communication self-efficacy (Fig. 1). Among girls who did report a relationship imperative, those reporting high HIV/STI knowledge were more likely than those reporting low HIV/STI knowledge to report unprotected vaginal sex in the past 30 days (Fig. 2) and less likely to report consistent condom use during vaginal, anal or oral sex in the past 30 (Fig. 3) or 90 days (Fig. 4).

Table 1. Logistic regression analyses assessing the effect of HIV and other sexually transmissible infections (HIV/STI) knowledge and relationship imperative on risky sexual behaviour and related psychosocial outcomes (n = 188).

Step 2, outcomes were regressed on HIV/STI knowledge (independent variable); Step 3, outcomes were regressed on relationship imperative (moderator variable); Step 4, outcomes were regressed on the interaction term. aOR, adjusted odds ratio, adjusted for age, financial assistance, and self-esteem in Step 1 (see text for details); CI, confidence interval

| Outcomes | Step 2: HIV/STI knowledge |

Step 3: relationship imperative |

Step 4: knowledge × imperative |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | 95% CI | P-value | aOR | 95% CI | P-value | aOR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Psychosocial | |||||||||

| Partner communication self-efficacy | 1.9 | 0.96–3.69 | 0.07 | 0.74 | 0.36–1.51 | 0.40 | 0.72 | 0.52–1.01 | 0.05 |

| Sex refusal self-efficacy | 1.6 | 0.81–3.07 | 0.18 | 0.38 | 0.18–0.81 | 0.01 | 0.83 | 0.60–1.15 | 0.27 |

| Relationship power | 1.6 | 0.83–3.09 | 0.16 | 0.28 | 0.13–0.61 | 0.001 | 0.91 | 0.65–1.27 | 0.58 |

| Condom use | |||||||||

| Unprotected vaginal sex, past 30 days | 1.3 | 0.68–2.51 | 0.42 | 2.1 | 0.98–4.31 | 0.06 | 1.4 | 1.02–2.01 | 0.04 |

| Unprotected vaginal sex, past 90 days | 1.2 | 0.64–2.36 | 0.54 | 1.1 | 0.56–2.27 | 0.73 | 1.2 | 0.90–1.67 | 0.20 |

| Consistent condom use during vaginal, anal, oral sex | |||||||||

| Past 30 days | 0.86 | 0.38–1.98 | 0.73 | 0.53 | 0.20–1.46 | 0.22 | 0.60 | 0.39–0.92 | 0.02 |

| Past 90 days | 0.91 | 0.42–1.96 | 0.81 | 0.59 | 0.24–1.44 | 0.25 | 0.68 | 0.47–0.98 | 0.04 |

Fig. 1.

Percentage of those reporting partner communication self-efficacy as a function of HIV and other sexually transmissible infections (HIV/STI) knowledge and relationship imperative.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of those reporting unprotected vaginal sex in the past 30 days as a function of HIV and other sexually transmissible infections (HIV/STI) knowledge and relationship imperative.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of those reporting consistent condom use for vaginal, anal or oral sex in the past 30 days as a function of HIV and other sexually transmissible infections (HIV/STI) knowledge and relationship imperative.

Fig. 4.

Percentage of those reporting consistent condom use for vaginal, anal or oral sex in the past 90 days as a function of HIV and other sexually transmissible infections (HIV/STI) knowledge and relationship imperative.

When testing the interaction of HIV/STI knowledge and relationship imperative while controlling for self-esteem, no interaction effect was found for refusal self-efficacy and relationship power; however, main effects were observed. Detained African American adolescent girls who did report a relationship imperative were less likely to perceive themselves able to refuse sex (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 0.38; P = 0.01) and less likely to report high relationship power (aOR 0.28; P = 0.001) than girls who did not report a relationship imperative.

Discussion

The present study examined the heightened risk for HIV/STIs when HIV/STI knowledge is high by applying the principle of least interest25 to understand sexual risk taking among a detained sample of young African American women. Although some girls had a high degree of knowledge regarding the transmission of HIV/STIs, this knowledge interacted with the endorsement of a relationship imperative to increase HIV/STI risk among this group. As expected, for girls who did not endorse a relationship imperative, HIV/STI knowledge was positively associated with self-efficacy to communicate with a partner about safer sex. However, this relationship did not exist for those girls who believed that being in a relationship at all times is important, because these girls were more likely to perceive themselves as unable to communicate with a partner about sexual health topics and condom use, despite having high HIV/STI knowledge. Raiford et al.23 found that despite having high HIV/STI knowledge, African American adolescent girls who were afraid that condom negotiation would place their relationship in jeopardy, including relationship termination or emotional or physical abuse, were more likely to report inconsistent condom use with their sexual partners. Given that in the present study greater HIV/STI knowledge was negatively associated with safe sexual behaviour when girls prioritised being in a relationship, it is possible that girls balanced the potential threat that negotiating safer sex may have on their relationship status with their perceived risk of contracting HIV or an STI. These girls may have determined that their relationship was at greater risk than their sexual health, despite having high knowledge of HIV/STIs, which, in turn, may have affected their self-efficacy to communicate with partners about safer sex.

Higher HIV/STI knowledge was associated with increased risk of unprotected or condomless sex among girls when they do endorse a relationship imperative. Furthermore, HIV/ STI knowledge did not predict sex refusal self-efficacy or relationship power, nor did it interact with endorsing a relationship imperative to affect these outcomes. However, endorsing a relationship imperative was negatively associated with relationship power and perceived self-efficacy to refuse sex. Consequently, African American girls involved in the juvenile justice system may be knowledgeable about how infections are transmitted, but they do not appear to use this knowledge to protect themselves sexually, either through condom use or refusing sex. It seems that endorsing a relationship imperative may create a power dynamic that limits their power in relationships, including their ability to refuse sex.

If young girls involved with the juvenile justice system believe that a relationship is imperative, they may engage in higher sexual risk behaviours or be in relationships characterized by a power imbalance that could jeopardises their sexual health. Therefore, it is incumbent upon researchers and practitioners to develop HIV prevention for young women that addresses these issues.

Prioritising romantic or sexual relationships may be particularly salient among a vulnerable population, like adolescent girls with a history of detention in the juvenile justice system. The majority of this sample of young girls was receiving financial assistance and had been detained multiple times. Relationships may be perceived as imperative because of financial strain and dependence on partners to alleviate that strain. It also is possible that youth with repetitive involvement in the justice system place a premium on romantic relationships as a means to cope with instability and seek connection, especially if they come from an unstable home environment. Research on detained males indicates family issues are implicated in youth involvement with the juvenile justice system41,42 and suggests that ‘unstable or highly dysfunctional families can lead youth to look elsewhere for a family of their own’ 43

Implications for practice

Detained African American adolescent girls are particularly vulnerable to contracting HIV/STIs compared with other adolescent populations. Risk reduction interventions are needed that acknowledge the vulnerabilities for this population and increase the opportunities for appropriate HIV/STI prevention efforts. Previous research has suggested that adult African American women are more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviours in order to maintain their relationships.44 Therefore, it is pertinent to intervene with African American girls, particularly those who are at high risk and may have riskier sexual networks. It also is important to improve their self-worth and self-esteem, as well as their understanding of healthy romantic and sexual relationships. However, there are varying reasons as to why adolescent girls may place their sexual health at risk because of the value and importance they place on being in a relationship. As a result, it is important to consider contextual factors that may be affecting their sexual decision making.

Intervening with girls while detained may seem ideal because many become ‘lost’ after release, making prevention efforts much more challenging. However, it is often not sufficient because the adolescent girls are returning to their communities, potentially placing themselves at higher risk. Detention interrupts any romantic relationship, and previous research has suggested that non-incarcerated men may engage in concurrent sexual partnerships during this time.45 Continuity of services and engagement of communities, families, peers and community-based organisations may be needed to assist in the transition back to their communities.

There are limitations to the present study. Cross-sectional analyses were conducted; therefore, temporal or causal interpretations cannot be made. Future longitudinal research could assess mediating factors that may also explain the associations between HIV/STI knowledge, relationship imperative and sexual risk among this population. Although an A-CASI was used to collect responses from participants, data were self-reported and are therefore subject to social desirability bias. Finally, the study sample was small and specific to African American adolescent girls involved with the juvenile justice system; hence, the results may not be generalisable to all adolescents or African American adolescent girls involved with the juvenile justice system. Further research with a larger sample size and diverse ethnic and geographic populations may be needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the young women who participated in this study. This study was funded by CDC Cooperative Agreement 1UR6PS 000679–01.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014; 63: 1–172.24402465 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitmore SK, Kann L, Prejean J, Koenig LJ, Branson BM, et al. Vital signs: HIV infection, testing, and risk behaviors among youths – United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012; 61: 971–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Reported STDs in the United States: 2012 national data for chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2014. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats12/std-trends-508-2012.pdf [cerified 22 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forhan SE, Gottlieb SL, Sternberg MR, Xu FJ, Datta SD, McQuillan GM, et al. Prevalence ofsexually transmitted infections among female adolescents aged 14 to 19 in the United States. Pediatrics 2009; 124: 1505–12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hockenberry S, Puzzanchera C. Delinquency cases in juvenile court, 2011. Pittsburgh, PA: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Preventions; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tolou-Shams M, Stewart A, Fasciano J, Brown LK. A review of HIV prevention interventions for juvenile offenders. J Pediatr Psychol 2010; 35: 250–61. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lederman CS, Dakof GA, Larrea MA, Li H. Characteristics of adolescent females in juvenile detention. Int J Law Psychiatry 2004; 27: 321–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2004.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chesney-Lind M, Sheldon RG. Girls, delinquency, and juvenile justice. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robertson AA, Thomas CB, St Lawrence JS, Pack R. Predictors of infection with chlamydia or gonorrhea in incarcerated adolescents. Sex TransmDis 2005; 32: 115–22. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000151419.11934.1b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robertson AA, St Lawrence J, Morse DT, Baird-Thomas C, Liew H, Gresham K. The Healthy Teen Girls Project: comparison of health education and STD risk reduction intervention for incarcerated adolescent females. Health Educ Behav 2011; 38: 241–50. doi: 10.1177/1090198110372332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snyder H, Sickmund M. Juvenile offenders and victims: 2006 national report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Crosby RA, Sionean C, Cobb BK, Harrington K, et al. Sexual risk behaviors associated with having older sex partners: a study of black adolescent females. Sex Transm Dis 2002; 29: 20–4. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200201000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pulerwitz J, Amaro H, De Jong W, Gortmaker SL, Rudd R. Relationship power, condom use and HIV risk among women in the USA. AIDS Care-Psychol Socio-Med Asp AIDS/HIV 2002; 14: 789–800. doi: 10.1080/0954012021000031868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report, 2013. Volume 25. 2015. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2013-vol-25.pdf [verified 6 March 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harter S. The construction of the self. New York: Guilford; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davila J, Steinberg S, Kachadourian L, Cobb R, Fincham F. Romantic involvement and depressive symptoms in early and late adolescence: the role of a preoccupied relational style. Pers Relatsh 2004; 11: 161–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00076.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Siebenbruner J, Collins WA. Diverse aspects of dating: associations with psychosocial functioning from early to middle adolescence. J Adolesc 2001; 24: 313–36. doi: 10.1006/jado.2001.0410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Siebenbruner J, Collins WA. A prospective study of intraindividual and peer influences on adolescents’ heterosexual romantic and sexual behavior. Arch Sex Behav 2004; 33: 381–94. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000028891.16654.2c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furman W, Wehner EA. Adolescent romantic relationships: a developmental perspective. In Shulman S, Collins WA, editors. Romantic relationships in adolescence: developmental perspectives. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1997. pp. 21–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banister EM, Jakubec SL, Stein JA. ‘Like what am I supposed to do?’: adolescent girls’ health concerns in their dating relationships. Can JNurs Res 2003; 35: 16–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teitelman AM, Bohinski JM, Boente A. The social context of sexual health and sexual risk for urban adolescent girls in the United States. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2009; 30: 460–9. doi: 10.1080/01612840802641735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banister E, Schreiber R. Young women’ s health concerns: revealing paradox. Health Care Women Int 2001; 22: 633–47. doi: 10.1080/07399330127170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raiford JL, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM. Effects of fear of abuse and possible STI acquisition on the sexual behavior of African American adolescent girls and young women. Am J Public Health 2009; 99: 1067–71. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.131482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Roosmalen E. Forces of patriarchy: adolescent experiences of sexuality and conceptions of relationships. Youth Soc 2000; 32: 202–27. doi: 10.1177/0044118X00032002004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guerrero LK, Andersen PA, Afifi WA. Close encounters: communication in relationships, 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raiford JL, Seth P, DiClemente RJ. What girls won’t do for love: human immunodeficiency virus/sexually transmitted infections risk among young African-American women driven by a relationship imperative. J Adolesc Health 2013; 52: 566–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bryan A, Aiken LS, West SG. HIV/STD risk among incarcerated adolescents: optimism about the future and self-esteem as predictors of condom use self-efficacy. J Appl Soc Psychol 2004; 34: 912–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02577.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danielson CK, Walsh K, McCauley J, Ruggiero KJ, Brown JL, Sales JM, et al. HIV-related sexual risk behavior among African American adolescent girls. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014; 23: 413–9. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swenson RR, Rizzo CJ, Brown LK, Vanable PA, Carey MP, Valois RF, et al. HIV knowledge and its contribution to sexual health behaviors of low-income African American adolescents. J Natl Med Assoc 2010; 102: 1173–82. doi: 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30772-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DiClemente RJ, Lanier MM, Horan PF, Lodico M. Comparison of AIDS knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors among incarcerated adolescents and a public school sample in San Francisco. Am J Public Health 1991; 81: 628–30. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.81.5.628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiClemente RJ, Crittenden CP, Rose E, Sales JM, Wingood GM, Crosby RA, et al. Psychosocial predictors of HIV-associated sexual behaviors and the efficacy of prevention interventions in adolescents at-risk for HIV infection: what works and what doesn’t work? Psychosomatic Med 2008; 70: 598–605. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181775edb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Price MN, Hyde JS. When two isn’t better than one: predictors of early sexual activity in adolescence using a cumulative risk model. J Youth Adolesc 2009; 38: 1059–71. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9351-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montano DE, Kasprzyk D, Taplin SH. The theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior. In Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, editors. Health behavior and health education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1997. pp. 85–112. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strecher VJ, Rosenstock IM. The health belief model. In Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, editors. Health behavior and health education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1997. pp. 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- 35.DiClemente RJ, Davis TL, Swartzendruber A, Fasula AM, Boyce L, Gelaude D, et al. Efficacy of an HIV/STI sexual risk-reduction intervention for African American adolescent girls in juvenile detention centers: a randomized controlled trial. Women Health 2014; 54: 726–49. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2014.932893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenburg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton. NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sikkema K, Kelly J, Winnett R, Solomon L, Cargil V, Roffman R, et al. Outcomes of a randomized community-level HIV prevention intervention for women living in 18 low-income housing developments. Am J Public Health 2000; 200: 57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Partner influences and gender-related factors associated with noncondom use among young adult African American women. Am J Community Psychol 1998; 26: 29–51. doi: 10.1023/A:1021830023545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Relationship characteristics and gender-related factors associated with noncondom use among young adult African American women. Am J Community Psychol 1998; 26: 29–51. doi: 10.1023/A:1021830023545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pulerwitz J, Gortmaker SL, DeJong W. Measuring sexual relationship power in HIV/STD research. Sex Roles 2000; 42: 637–60. doi: 10.1023/A:1007051506972 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farrington DP. Predictors, causes and correlates of male youth violence. In Tonry M, Moore MH, editors. Youth violence. Vol. 24. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1998. pp. 421–47. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. A social learning approach: antisocial boys. Eugene, OR: Castalia; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Underwood LA, Phillips A, von Dresner K, Knight PD. Critical factors in mental health programming for juveniles in corrections facilities. Int J Behav Consult Ther 2006; 2: 107–40. doi: 10.1037/h0100771 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FE, Donaldson KH, Fullilove RE, Aral SO. Social context of sexual relationships among rural African Americans. Sex Transm Dis Aquatic Organisms 2001; 28: 69–76. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200102000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nunn A, Dickman S, Cornwall A, Kwakwa H, Mayer KH, Rana A, et al. Concurrent sexual partnerships among African American women in Philadelphia: results from a qualitative study. Sex Health 2012; 9: 288–96. doi: 10.1071/SH11099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]