Abstract

For decades, a wide variety of natural and synthetic materials have been used to augment human tissue to improve aesthetic outcomes. Dermal fillers are some of the most widely used aesthetic treatments throughout the body. Initially, the primary function of dermal fillers was to restore depleted volume. As biomaterial research has advanced, however, a variety of biostimulatory fillers have become staples in aesthetic medicine. Such fillers often contain a carrying vehicle and a biostimulatory material that induces de novo synthesis of major structural components of the extracellular matrix. One such filler, Radiesse (Merz Aesthetics, Raleigh, NC), is composed of calcium hydroxylapatite microspheres suspended in a carboxymethylcellulose gel. In addition to immediate volumization, Radiesse treatment results in increases of collagen, elastin, vasculature, proteoglycans, and fibroblast populations via a cell-biomaterial–mediated interaction. When injected, Radiesse acts as a cell scaffold and clinically manifests as immediate restoration of depleted volume, improvements in skin quality and appearance, and regeneration of endogenous extracellular matrices. This narrative review contextualizes Radiesse as a regenerative aesthetic treatment, summarizes its unique use cases, reviews its rheological, material, and regenerative properties, and hypothesizes future combination treatments in the age of regenerative aesthetics.

Level of Evidence: 5

Regenerative medicine is an emerging interdisciplinary field of medicine that aims to restore the structure and function of damaged or diseased tissues.1 Tissue damage can arise from injury, extrinsic factors, pathologies, malnutrition, and many other causes.2 Aging is one such cause and is driven both chronologically and environmentally. Aging produces ongoing degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM) of the skin and a decrease in fibroblast quantity and activity that clinically manifests as progressive wrinkling, fat loss, and worsening skin quality.2 Dermatologists, plastic surgeons, and other aesthetic practitioners have been applying regenerative medicine modalities to address aging, thus giving rise to the field of regenerative aesthetics. Regenerative aesthetics can be defined as a branch of regenerative medicine with therapies aimed at recapturing the youthful structure and function of tissue by exploiting the body's own systems.3 Some regenerative aesthetic treatments are biologically derived. For example, stem cells, stromal vascular fraction, exosomes and extracellular vesicles, growth factors, platelet-rich plasma and fibrin, and allograft adipose matrices are becoming increasingly common treatment options in aesthetics.3,4 Some injectable fillers containing exogenous materials have been repeatedly shown to drive endogenous ECM regeneration.5 Injectable treatments offer the ability to augment and regenerate soft tissue in a minimally invasive manner with minimal downtime. As such, interest in these procedures has seen dramatic increases in the past several years.6

Calcium hydroxylapatite (CaHA) is a bioceramic with exceptionally high biocompatibility that, when injected, drives the regeneration of collagens I and III, elastin, and proteoglycans, and de novo formation of tissue and vasculature. The restoration of these structures clinically manifests as tighter, brighter, more pliable, more elastic, more hydrated, less wrinkled, and more youthful skin in a variety of anatomies. In contrast to some other treatments such as poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA), CaHA drives soft tissue regeneration with minimal adaptive immune cell recruitment and without chronic inflammation. Radiesse (CaHA-R; Merz Aesthetics, Raleigh, NC), a commercially available regenerative dermal filler that contains CaHA microspheres suspended in a carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) gel, received FDA approval in 2006 for the correction of facial lipoatrophy in people with human immunodeficiency virus and moderate to severe facial wrinkles and folds. In subsequent years, additional approvals from the FDA have included correction of volume loss in the dorsum of the hands and augmentation to improve moderate to severe loss of jawline contour, with injections indicated in the subdermal and supraperiosteal planes. In clinical practice, Radiesse is often mixed with diluents of varying volumes to treat larger volumes of soft tissue with the observation that it improved the structure and function of the skin.

Noting the increasing interest in regenerative aesthetics and use of Radiesse, the following review article summarizes literature published in both the biomaterials, mechanobiology, dermatology, and aesthetic fields pertaining to the influence of CaHA, CMC gel, and Radiesse to restore components of the skin. The preliminary literature screen consisted of searching Google Scholar (Alphabet Inc., Mountain View, CA), PubMed (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), and ResearchGate (Berlin, Germany) for published works that contributed to the understanding of the mechanism of Radiesse. All peer-reviewed manuscripts, regardless of publication date and language, were considered. To this end, the manuscript reviews the independent and aggregate material components of Radiesse and their unique properties, its rheological and mechanical characteristics, cell-biomaterial interactions, the regenerative mechanism of action (MOA) of Radiesse and its role in restoring the structure and function of the skin. The structure of the review begins with the material properties of Radiesse, progresses into the physiology of aging, expands into cellular and structural studies with Radiesse, and broadens into clinical evidence of the recovery of youthful skin structure and function. Because Radiesse is not the only CaHA-containing filler, it will be herein referred to as CaHA-R; CaHA will refer to just the CaHA microsphere component of the filler(s), and CMC will refer only to CMC.

MATERIAL COMPONENTS

Calcium Hydroxylapatite

CaHA is a bioceramic with exceptionally high biocompatibility that, when injected, drives the regeneration of collagens I and III, elastin, and proteoglycans, and causes de novo formation of tissue and vasculature. The restoration of these structures clinically manifests as tighter, brighter, more pliable, more elastic, more hydrated, less wrinkled, and more youthful skin in a variety of anatomies. In contrast to some other treatments such as PLLA, CaHA drives soft tissue regeneration with minimal adaptive immune cell recruitment and without chronic inflammation.

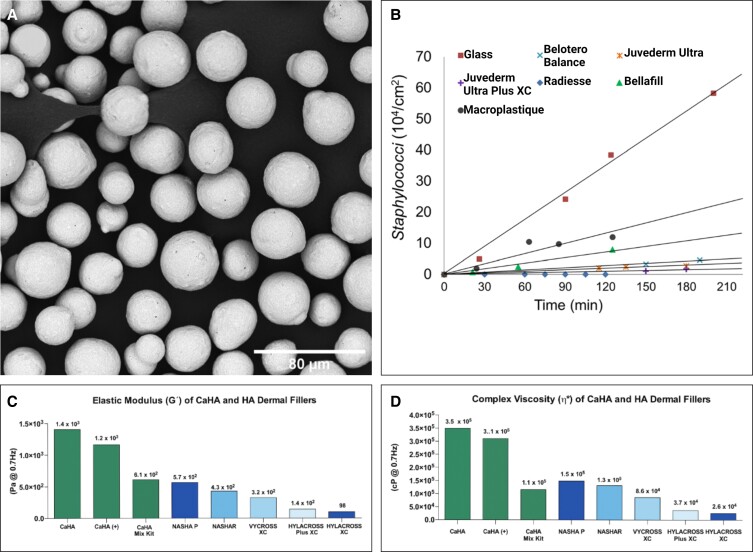

Comprising 30% weight by volume (w/v) of CaHA-R, CaHA is a critically important material integral to tissue regeneration. The CaHA used in CaHA-R is a calcium- and hydroxylapatite-based bioceramic that is nearly identical to the molecular composition of endogenous CaHA and has a long history of use for a variety of biomedical applications.7 Additionally, the synthetic CaHA is manufactured as homogeneous microspheres (20-45 µm in diameter) via precipitation and sintering (Figure 1A).8 Whereas other fillers in aesthetics contain polymers such as PLLA (Sculptra [PLLA-SCA]; Galderma Laboratories LP, Dallas, TX), polycaprolactone (PCL; Ellansé, Sinclair Pharma GmbH, Frankfurt, Germany), and polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA; Bellafill, Suneva Medical, San Diego, CA), CaHA-R exists as the only FDA-approved bioceramic for aesthetic indications. Bioceramics have a variety of favorable properties compared to polymeric fillers. CaHA-R is entirely biodegradable, has excellent stability in situ, and can persist for up to 30 months.11,12 Hydroxylapatites are thermally superior to polymers and have sintering temperatures of ∼1000°C, far above supraphysiological temperatures.13

Figure 1.

CaHA-R filler characterization data. (A) Scanning electron microscopy images of CaHA-R show uniformly sized, smooth, and defect-free microspheres. (B) Antibacterial properties of different filler types showing near-zero Staphylococci adherence to CaHA-R. (C) Elastic moduli and (D) Complex viscosity of different filler types measured at 0.7 Hz. CaHA, calcium hydroxylapatite; CaHA-R, calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse; Merz Aesthetics, Raleigh, NC); HA, hyaluronic acid. Juvederm Ultra Plus XC, Juvederm Ultra (Allergan, an AbbVie Compay, Chicago, IL), Belotero Balance (Merz Aesthetics, Raleigh, NC), Bellafill (polymethylmethacrylate; Suneva Medical, San Diego, CA), Macroplastique (polydimethylsiloxane/polyvinylpyrrolidone; Laborie Medical Technologies Corporation, Portsmouth, NH). Figure 1B is reproduced with permission from Wang et al (2022).9 Figure 1C, D is reproduced with permission from Lorenc et al (2018).10

Conversely, polymeric fillers have glass transition temperatures (where the polymer becomes soft) within or near physiological temperatures or temperatures encountered with use of energy-based devices. For example, PLLA and PCL have glass transition temperatures of 55 to 60°C and −84 to −60°C, respectively.14,15 Thermal stability is an important consideration for combination treatments that may use energy-based devices because localized heating may deform polymeric fillers and render them less efficacious or increase immune cell recruitment.16 Adsorption of cells and proteins onto the surfaces of the microsphere components may be particularly important for long-term regeneration and thus it is favorable to have microspheres with hydrophilic surfaces for maintaining protein and cell attachment. Polymers such as PLLA are relatively hydrophobic, whereas CaHA microspheres are generally hydrophilic.17,18 To summarize, CaHA is a bioceramic with high biocompatibility, excellent stability and intrinsic material properties, and high cell and protein adsorption rates that can be used alone or in combination with other treatments without interfering with its regenerative properties.

Carboxymethylcellulose

CMC gel makes up 70% w/v of CaHA-R and is a water-soluble derivative of cellulose prepared with alkylating reagents on the activated noncrystalline portions of cellulose.19 CMC gel possesses several properties that make it uniquely suited as a gel carrier. CMC is a widely used biomaterial in regenerative medicine due to its organic origin, high biocompatibility, minimal inflammatory reaction, and ability to sustain cell proliferation.20,21 CMC is also biodegradable and rapidly removed from the body within 6 to 8 weeks. Although it is essential to meet some of the basic material requirements as a filler (ie, biocompatible, noncytotoxic, noninflammatory, etc), 3 properties of CMC make it uniquely suited as a dermal filler gel for aesthetic indications: high porosity, antibacterial activity, and shear-thinning fluid mechanics.

Porosity of the CMC gel is critically important to enable cellular penetration into the filler to ensure occurrence of CaHA-fibroblast interactions22 and to achieve natural-looking and natural-feeling integration with host tissue. When comparing pore size and bead penetration into hyaluronic acid (HA), CaHA-R, and PMMA fillers, CaHA-R demonstrated superior porosity compared to all HA fillers and similar porosity to PMMA fillers.9 CMC gel is inherently antibacterial against a variety of bacterial pathogens, including Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus.23 CaHA-R has been shown to be the only filler to have no S. aureus interactions despite having high protein adsorption and porosity (Figure 1B).9 The ability to resist bacterial invasion and biofilm formation is particularly relevant in aesthetic medicine as these issues often clinically manifest in anatomies that are difficult to hide (eg, face, neck, chest), may induce physiological distress for patients, and may, in part, explain why late-onset nodule formation is more commonly seen in HA fillers.24-26

CMC gel is also shear-thinning (ie, its viscosity decreases under shear strain).27,28 Shear-thinning, non-Newtonian fluids are ideal gel carriers for microspheres, as decreased viscosity during injection through small needles and cannulas remove shearing forces from the microspheres, thus preserving their shape and preventing fractures—both of which are necessary for preventing adverse events and mitigating inflammation.29,30 Additionally, shear-thinning gel carriers may disperse in situ more evenly and efficiently than Newtonian or shear-thickening fillers, such as saline or water, common diluents for PLLA, or some differentially crosslinked HA gels. Homogeneous dispersion is critical in preventing formation of nodules of accumulated product, which may explain why other filler types, such as PLLA and PMMA, have higher nodule formation rates.30-32 Taken together, CMC gel is an ideal gel carrier due to its favorable biocompatibility, biodegradation, high porosity, antimicrobial properties, and shear-thinning rheology.

Mechanical and Rheological Properties of CaHA-R

An aesthetic filler's mechanical and rheological properties are important factors in filler selection.33 Two primary measures of these filler properties are elastic moduli (G′) and complex viscosity (η*). G′ is a measure of rigidity or stiffness and is often clinically referred to as “lift.” Materials with high G′ values are mechanically strong and may resist deforming loads exerted by surrounding tissues; therefore, materials with high G′ values are ideal fillers for lifting or supporting soft tissue and mimicking bony morphologies, such as chin and jawline.34,35 Complex viscosity is the measure of flow resistance and is relevant to evaluate filler migration potential. Materials with high η* are less likely to migrate, even in highly mobile anatomies. Occasionally, clinicians consider viscous modulus (G″), which is a measure of loss modulus and is equivalent to η* when considering linearly viscoelastic materials, although it is generally agreed that η* is a more clinically relevant measure.36

A myriad of studies have investigated differences in the mechanical and rheological properties of dermal fillers and have linked various rheological properties with differential clinical outcomes. Two factors largely influence the rheology of fillers: material selection and subsequent modification (ie, crosslinking, polymerization, addition of microspheres). For HA fillers, the degree and type of crosslinking is a large determinant of rheological properties. For fillers capable of restoring parts of the ECM, such as CaHA, PLLA, and PMMA, the type of carrier gel, concentration of microparticles, and microparticle material determine the rheological properties.37 Of all HA, semipermanent, biostimulatory, and regenerative fillers across numerous studies in the literature, CaHA-R has demonstrated the highest measures in elastic modulus, compression resistance, and viscosity.

In a rheological study of 7 commercially available fillers, CaHA-R had an η* of 349,830 cPa and a G′ of 1407 Pa at 0.7 Hz (measurement frequency for the tests); both measures were approximately 3 times higher than the second-highest filler, Restylane SubQ (Galderma Laboratories, Dallas, TX).38 In another study at 5 Hz, CaHA-R had a G′ of 2782 Pa, a G″ of 1075 Pa, and a compressive force of 225 gram-force. While the G′ and compressive force of CaHA-R were approximately 3 times higher than values for the next highest fillers (Perlane [Galderma Laboratories, Dallas, TX] and Juvéderm Ultra Plus [Allergan, an AbbVie Company, Chicago, IL], respectively), the G″ was nearly 5 times higher than the next highest filler (Restylane).37 Studies by Sundaram et al and Lorenc et al all present similar findings, with CaHA-R showing the highest G′ and η* of all HA and semipermanent fillers,10,36,39 indicating that CaHA-R is the most mechanically and rheologically robust semipermanent filler currently commercially available.

Diluting CaHA-R decreases its rheological and mechanical properties, and while one can always dilute a filler into a range of lower G′ or η* values, it is not possible to concentrate a filler into a higher range of values. In practice, the rheological and mechanical properties of CaHA-R make it an incredibly versatile filler. For example, undiluted CaHA-R is uniquely suited for supraperiosteal injections due to its high G′, which may effectively augment the lift supplied by endogenous boney morphologies. Similarly, diluting CaHA-R into a range of lower G′ values may closely emulate the rheology and feel of subcutaneous fat.

Extrusion Force

Extrusion force (ie, the pressure necessary to extrude a filler) is another important factor for selecting a filler because it may determine the ease and safety of application for an injector—fillers with lower extrusion forces may be preferred for some treatment areas. Ease of injection is likely related to particle distribution, with several studies highlighting the importance of even flow and distribution important for preventing nodule formation.31

Although rheological properties and extrusion forces are intricately connected, it is not always the case in some non-Newtonian fluids. The CMC component of CaHA-R may impart some shear-thinning aspects to the filler, which is supported by data generated by Backfisch et al.27,28,40 Backfisch et al measured the extrusion force of CaHA-R, CaHA/HA, and CaHA/polyethylene glycol (PEG), and found that CaHA-R had the lowest extrusion force despite having the highest G′.40 This is largely explained by the non-Newtonian fluid mechanics of the CMC gel. During shear-thinning, CMC gel protects CaHA microspheres from shearing forces, which may explain why the particles appear defect-free after injection with small-gauge needles, while the CaHA/HA and CaHA/PEG microspheres appear damaged after application of a constant extrusion force. After injection, however, the CMC gel returns to a Newtonian state with high G′ values. Another study investigating the effect of different fillers and their apparatus on ease of injection found that CaHA-R had extrusion forces that varied significantly only when injecting from a 30-gauge needle; the lowest extrusion forces with CaHA-R were approximately 5 N from a 27-gauge needle, increasing to about 9 N with a 30-gauge needle.41 While CaHA-R generally had the highest extrusion forces compared to the HAs investigated (Belotero Balance [Merz Aesthetics, Raleigh, NC], Juvéderm Voluma [Allergan, an AbbVie Company, Chicago, IL], Revanesse Versa [Prollenium Medical Technologies Inc., Ontario, Canada], Restylane Lyft [Galderma Laboratories GmbH, Dallas, TX], and Teosyal RHA3 [Teoxane Laboratories, Geneva, Switzerland]), it was one of 2 fillers with G′ values higher than its relative extrusion force, meaning that despite having a tremendously high G′, CaHA-R does not suffer from exceptionally high extrusion forces.41

FILLER CHARACTERIZATION

In addition to rheological and mechanical properties, a variety of other characteristics are important when considering a filler, particularly one that incorporates particles or microspheres for regeneration. Particle size homogeneity, particle distribution, surface smoothness, microsphere roundness, and particle defects all play a role in modulating dermal regeneration and immune response.16,29 It is well known that the body recognizes size discrepancies in foreign objects and attenuates its immune response accordingly.42 To mitigate robust inflammation, an ideal biostimulatory or regenerative filler would have a relatively homogeneous particle size distribution. Particles that are too small (<10 µm) will be easily phagocytosed, will not lead to a significant duration of effect, and may increase inflammation;29,42 if particles are too large, they will suffer from accumulation (ie, nodule formation) and lack of lateral tissue spread, and may inhibit ideal cellular proliferation.43 A combination of particles that are too small and too large may result in sustained inflammation, increased degradation rates, and undesirable aesthetic outcomes.42 Similarly, the roundness and smoothness (quantity of surface irregularities) are significant immune modulators.16,29 Although most fillers containing microspheres appear to be spherical prior to injection, polymeric microspheres frequently appear deformed in situ, even after several weeks.44,45 These deformations may lead to an increase in immune cell activation, product accumulation, nodule formation, and diminished cell-biomaterial activation. Unlike polymeric microspheres, however, CaHA-R appears as spheres in nearly all clinical study biopsies.10,46,47 The retention of sphericity in situ likely contributes to the lack of inflammatory cytokines and immune cell recruitment to CaHA-R injection sites.48,49 Particle shape, smoothness, aspect ratio, and degree of surface defects are known activators of immune cells and can increase the release of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL) β-1.42,50

CaHA-R IS A REGENERATIVE AESTHETIC TREATMENT

In aesthetic medicine, treatments restoring endogenous tissue form and function have been loosely described as “biostimulators.”5 A more accurate syntax can distinguish modalities, as biostimulators stimulate the synthesis or release of some biologic component (eg, growth factors, cells, proteins). Conversely, regenerative aesthetics implies the repair and restoration of damaged tissues and/or the synthesis of de novo cells or tissues that retain youthful structure and proper physiological function.1 Within this syntax, treatment may be biostimulatory but not necessarily regenerative, or it may be regenerative, which is de facto biostimulatory.

Extracellular Matrix and Mechanobiology

The ECM is the acellular, protein-based scaffolding that supplies tissues with structure.51 Although acellular, a healthy ECM is populated with a variety of cells in a complex network that supplies tissues with their intended biological function. The bulk of the ECM is made up of collagen (types I, III, IV), elastin, laminin, glycosaminoglycans, and proteoglycans.52 In the skin ECM, collagen I and collagen III impart the most structure and rigidity and act as the primary cell scaffolding; the ratio of collagen I to collagen III and their degree of crosslinking largely determine the skin's tensile and mechanical strengths.53 Another protein, elastin, imparts the elasticity, stretch, and pliability of the skin.54 Proteoglycans and HA contribute to the hydration, viscoelasticity, and smoothness of the skin.55

Skin ECM is mostly populated with fibroblasts and keratinocytes. During aging, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) or environmental stressors (eg, ultraviolet damage, smoking, chemical exposure leading to increased matrix metalloproteinases, reactive oxygen species) slowly degrade the skin ECM, resulting in a loss of form and eventually function, which clinically manifests as skin laxity, wrinkling, discoloration, and volume depletion.2,53,55 The destruction of collagen is the primary driver of cellular aging, and when the rate of collagen degradation outpaces the rate of collagen renewal, mechanical aging occurs.2

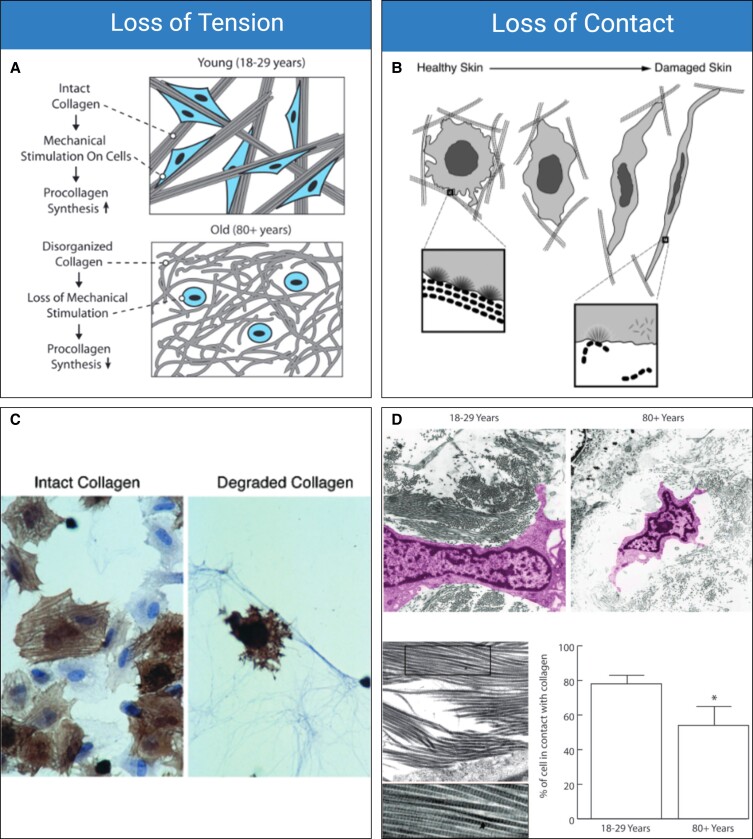

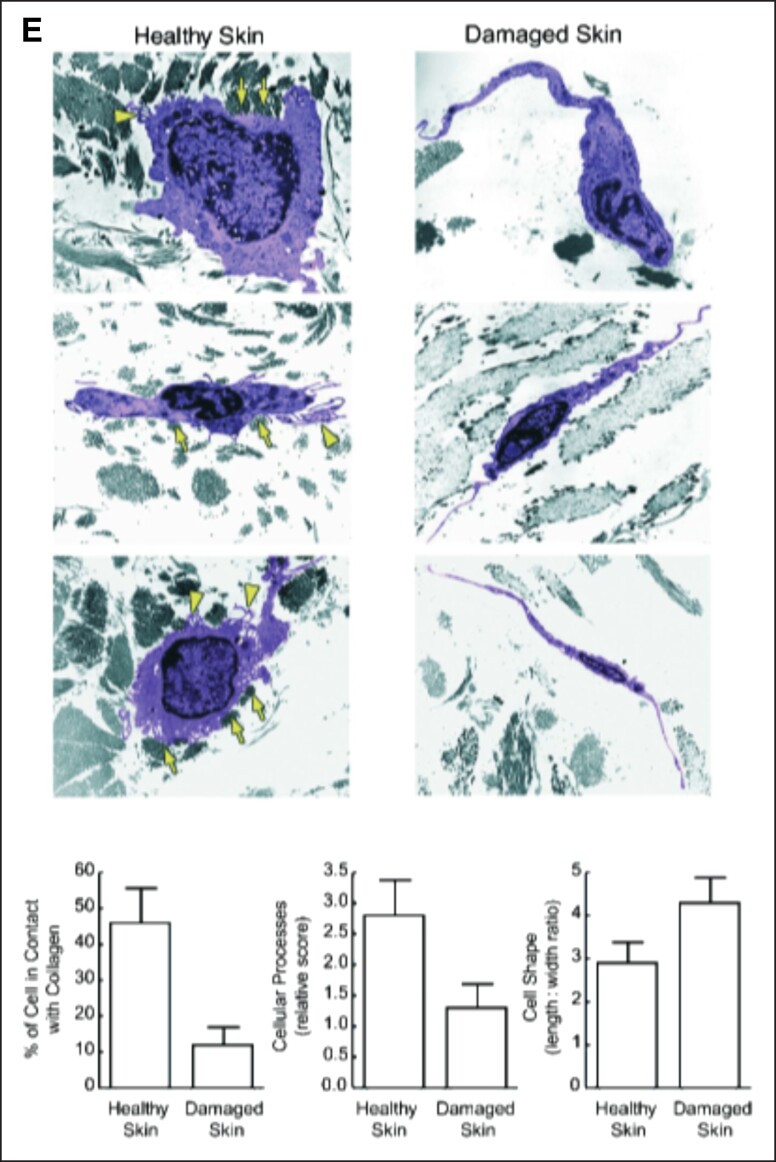

As the ECM is degraded, the tension and rigidity of the constituting fibers are lost.51 Fibroblasts rely upon contact and tension with mechanically robust ECM fibers for proper function. The mechanical interaction between the ECM and fibroblasts is broadly referred to as mechanotransduction.56,57 When fibroblasts are in contact with a healthy ECM (which can be defined as mechanically robust, with thick, oriented fibers, and a high density of endogenous proteoglycans), their mechanoreceptors are activated and in a proliferative and anabolic state. Loss of either contact or tension will initiate cellular senescence or apoptosis (Figure 2A, B).58-61 Delvoye et al directly measured the mechanical forces generated by fibroblasts in a 3-dimensional matrix, demonstrating that the reduction in synthesized collagen was a direct consequence of reduced mechanical tension and further showing that the loss of tension downregulated transcription of procollagen genes and increased MMP concentrations.62 In 2 pivotal studies, Varani et al studied the mechanoregulation of fibroblasts relative to aging, revealing that chronologically aged skin produces significantly less collagen due to the gradual loss of mechanical tension with ECM fibers.2,59 In Varani et al's first (2004) study, the role of mechanoreceptor activation and aging were investigated. In this study, it was revealed that the loss of contact with intact collagen led to a similarly negative change in both fibroblast morphology and function (Figure 2C).59 Varani et al's second (2006) study demonstrated that aged collagen loses orientation, rigidity, and thickness, all of which negatively affect the morphology of endogenous fibroblasts and result in less cellular surface area coverage (Figure 2D).2 In healthy skin, fibroblasts are flattened and cover a large surface area; in damaged skin, the cells appear spindly, lack anchoring sites, and are significantly less active than healthy fibroblasts (Figure 2E).2

Figure 2.

Mechanobiology of aging. (A) Loss of tension and (B) loss of contact are proposed as 2 driving mechanobiological factors of aging. (C) Confocal images of α-actin–stained fibroblasts (brown) cultured with intact collagen (left) and degraded collagen (right) show differences in cellular morphologies. (D) Young (18- to 29-year-old) fibroblasts and old (80+-year-old) fibroblasts show different morphologies and are correlated with less organized and misaligned collagen fibers, resulting in aged fibroblasts having significantly less mechanoreceptor activation. (E) Healthy (sun protected) and damaged (sun damaged) fibroblasts show changes in morphology. Damaged fibroblasts have less contact with collagen, are less active, and are significantly more elongated than healthy fibroblasts. Figure 2A, D is reproduced with permission from Varani et al (2006).2 Figure 2B, C, E is reproduced with permission from Varani et al (2004).59

Contact and mechanical tension are crucial in retaining proper cellular function. Two studies identified a network of genes related to fibroblast attachment–regulated signaling, demonstrating that the loss of mechanical tension in a 3-dimensional scaffold caused a rapid change in fibroblast gene expression related to cell death and loss of collagen production. The mechanoregulatory pathways involved modulation of IL-6, IL-8, nuclear factor (NF) κB, transforming growth factor β1, p53, and interferon-γ as central participants.60,61,63,64

Applying this to aesthetic medicine, regenerative treatments aim to interrupt the aging process by increasing collagen production, by halting collagen degradation, or by favorably modulating gene expression. When tension and contact are restored to fibroblasts, their function is usually recovered, in turn interrupting the degradative processes that characterize aging, such as MMP degradation of the ECM.59 Therefore, an ideal regenerative dermal filler would act as a scaffold for fibroblasts, induce cell-biomaterial interactions resulting in the restoration of the architecture of the ECM, functionally regenerate major components of the ECM, restore the structure and function of the skin, and lead to a favorable aesthetic outcome.

Proliferative Effect of CaHA-R

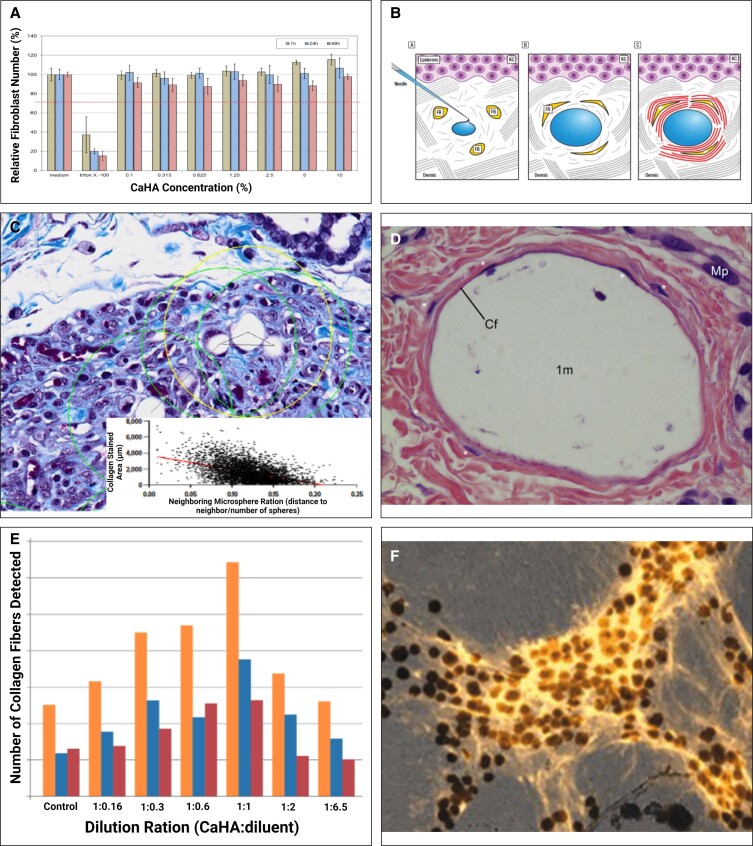

In general, an ideal biomaterial implant is biocompatible, biodegradable, immunologically inert, efficacious, and tunable to the patient. CaHA has been used as a biomaterial in aesthetics, orthopedics, laryngology, and other subspecialties for years.65-67 Many studies have investigated the biocompatibility of CaHA, finding it to be biocompatible even at extremely high concentrations.49,68-70 Specifically, in vitro studies with normal primary human fibroblasts co-cultured with CaHA show viability (>80%) up to a 0.1% concentration of CaHA.68 In an in vitro study of several cellular analyses with both human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) and human keratinocyte (HaCaT) cells cultured directly with CaHA for 48 hours,69 cell proliferation and cytotoxicity were measured via luminometric adenosine triphosphate (ATP) luciferase fluorescence and lactate dehydrogenase, respectively (Figure 3A). This study found that for both HaCaT and HDFs, ATP concentrations increased over time in both control and CaHA-treated groups. Additionally, there was no linear dose-dependent decrease in lactate dehydrogenase concentration with increasing CaHA concentrations. Together, this study demonstrated that both HaCaT and HDFs had increased metabolic activity when cultured with CaHA and did not experience any cytotoxicity, regardless of the concentration of the microspheres.

Figure 3.

Regenerative mechanism of action of CaHA-R. (A) Cell culture studies demonstrated dose-independent cell viability demonstrating excellent biocompatibility of CaHA-R. (B) The “stretch” mechanism of action hypothesized by Wang et al, which states that: (1) a hydrogel filler is shown as preferentially localizing in areas containing more highly fragmented collagen fibers, since these regions may be more accommodating; (2) this results in stretching of existing collagen fibers (curved lines), which is sensed by nearby fibroblasts through cell surface receptors such as integrins. In response, fibroblasts become morphologically stretched (3) and activated to produce extracellular matrix components, suggesting the volumetric displacement from the carboxymethylcellulose carrier gel may contribute to regeneration. (C) Collagen staining (blue) and regression analysis showing relationship between microsphere density and collagen regeneration. Green circles denote single microspheres; yellow circle denotes microsphere grouping; black triangluation denotes the distance calculation between microspheres. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin stains showing a capsule of stretched endogenous fibroblasts (denoted with *) encapsulating a CaHA microsphere surrounded by collagen fibers (Cf) and not in contact with macrophages (Mp). 1 m = 1 month post injection. (E) Clinical study showing the dilution-dependent regeneration of collagen I and III, thus highlighting the relevance of having space between microspheres to enable cell-biomaterial interactions. (F) Confocal microscopy images of de novo collagen I fibers arising from and connecting to neighboring CaHA microspheres, resulting in (G) highly aligned and dense collagen networks. (H) The working mechanism of action of CaHA-R: fibroblasts encounter CaHA microspheres and undergo direct mechanotransduction (activation of mechanoreceptors and stretching) that results in extracellular matrix protein synthesis. CaHA, calcium hydroxylapatite; CaHA-R, calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse; Merz Aesthetics, Raleigh, NC); FB, fibroblasts; KC, keratinocytes. Figure 3A is reproduced with permission from Wollina et al (2018).69 Figure 3B is reproduced with permission from Wang et al (2007).71 Figure 3D is reproduced with permission from Kim (2019).72 Figure 3E is reproduced with permission from Casabona and Pereira (2017).73

In vivo results from both animal and human studies have demonstrated the sustained and long-term proliferation of endogenous cells following injection of CaHA-R. Yutskovskaya et al measured endogenous cell proliferation with a Ki67 assay following a treatment with diluted CaHA and microfocused ultrasound and observed significant increases in proliferation at 8 and 12 months.47 The authors hypothesized that the significant change in proliferation at 8 months could be due to angiogenesis following treatment. Other studies have demonstrated that mechanical stimulation can induce rapid fibroblast proliferation.74 This may indicate that, as cells contact CaHA microspheres, their mechanoreceptors increase their proliferative response. The mechanism by which CaHA-R induces cellular proliferation is likely combinatorial and multifaceted.

Regenerative Mechanism of Action of CaHA-R

An injectable filler that can interrupt one or more of the degenerative pathways (ie, loss of tension in the ECM, upregulation of MMPs, lack of cell mechanical stimulation) will lead to the regeneration or restoration of youthful skin structure and function. When CaHA-R is injected, a variety of regenerative pathways and phenotypic changes are initiated, beginning with immediate volumization and aesthetic correction supplied by the CMC gel.75 In the past, studies have demonstrated that HA fillers may induce some de novo collagen and elastin synthesis via bulk mechanical tension (Figure 3B).71 Although the elastic deformation of the skin from the CMC gel may drive some minor regeneration, it is likely marginal as other studies have comparatively evaluated the regenerative effect of CaHA and HA and found that the CaHA microsphere-fibroblast interaction is the driving regenerative mechanism.76 For instance, when the regenerative effect of CaHA-R was compared to Juvéderm Voluma, CaHA-R-treated patients saw significantly more collagen I and elastin synthesis than did the Juvéderm-treated group (Table 1).76

Table 1.

Differences in Regenerative Effects of CaHA-R and HA Gel in a Randomized, Split-Face Human Study76

| Treatment | Collagen I staining index (month 9) | Elastin staining index (month 9) | Angiogenesis mean score (month 9) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CaHA-R (Radiesse; Merz Aesthetics, Raleigh, NC) | 6.58 | 5.20 | 3.4 |

| HA gel (Voluma; Allergan, an AbbVie Company, Chicago, IL) | 4.80 | 4.33 | 1.1 |

| % Difference | 31.57% | 18.26% | 102.22% |

| P-value | 0.0135 | 0.0004 | <0.0001 |

CaHA-R, calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse; Merz Aesthetics, Raleigh, NC); HA, hyaluronic acid.

Evidence of mechanotransduction via direct mechanical interaction is documented in both in vitro and in vivo studies. Nowag et al investigated the impact microsphere proximity has on neocollagenesis and fibroblast proliferation.77 Their findings indicate that sufficient space between microspheres is required to allow fibroblasts to contact microspheres, thus activating their mechanoreceptors (Figure 3C). When sufficient distance between neighboring microspheres was achieved, a greater amount of de novo collagen was synthesized. This study suggested that mechanical interactions between fibroblasts and CaHA microspheres is critical to initiate early neocollagenesis.77 Kim et al investigated regeneration of ischial soft tissue from previous phase chronic sitting pressure sores by injecting hyperdiluted CaHA-R into multiple planes of the skin. A histologic analysis revealed CaHA microspheres directly interacting with dermal fibroblasts (Figure 3D).72 The morphology of the fibroblasts in direct contact with CaHA microspheres corroborates the morphology of the healthy fibroblasts on a robust ECM.59 The mechanical interaction and subsequent activation of fibroblastic mechanoreceptors initiates a proliferative and proregenerative pathway.

Further support for the mechanotransduction theory is evident in work investigating the importance of space between CaHA microspheres for early neocollagenesis, which observed that an optimal distance between microspheres is necessary for regeneration because the cell-biomaterial interaction is limited when microspheres are too densely packed. That is, in early neocollagenesis, lower density of microspheres per area leads to more collagen production, which similarly correlates with an increase in fibroblasts present in the area (Figure 3C).43 Casabona and Pereira's recent clinical study demonstrated a dilution-dependent neocollagenesis effect (Figure 3E).73 In this study, a 1:1 dilution was optimal for collagen regeneration, and the authors hypothesized that the fibroblastic response to CaHA is dependent on the cell-material interactions. Dilutions up to 1:6.5 still led to higher total collagen relative to control. Similarly, an in vitro study co-culturing CaHA-R and fibroblasts showed the neocollagenic effect—that is, an increase in collagen I in areas of high CaHA microsphere density after 7 days of culture (Figure 3F).78 Collagen I expression was increased after incubation with CaHA microspheres and was densest directly surrounding the microspheres. In addition, collagen fiber thickness and orientation were increased with CaHA–co-cultured fibroblasts (Figure 3G). Thick, oriented collagen fibers are the hallmark of healthy and mechanically robust ECM.79 CaHA microspheres alone can drive favorable ECM reorganization by increasing the quality, quantity, and alignment of collagen fibers. However, polymers such as PLLA function via a distinctly different mechanism.

Ray and Ta investigated the biostimulatory effect of PLLA in vitro and found that significant neocollagenesis could not be achieved without the presence of macrophages.80 In an in vivo study, Stein et al revealed direct PLLA microsphere-macrophage interaction with both confocal and histologic analysis.81 In this study, PLLA microspheres were surrounded by macrophages and showed peripheral activation of fibroblasts and synthesis of de novo collagen. Although significant neocollagenesis of type I collagen was achieved and is widely reported in the literature, it occurs without direct mechanical stimulation of fibroblasts and in the absence of collagen III.80-82 These findings are consistent with the subclinical chronic inflammatory response sustained with PLLA-SCA treatment.

Direct mechanotransduction may remove or reduce the variability in outcomes by minimizing the role of the immune system in expected aesthetic outcomes. Mechanical interaction may be favorable in that CaHA serves to immediately initiate regeneration with direct contact via mechanoreceptor activation (Figure 3H). Significant changes in both collagen I and III content have been observed after 72 hours in fibroblasts co-cultured with CaHA-R.83 The immediate restoration of mechanical stimulation to fibroblasts serves to instantly disrupt the degradative aging processes.74 Mechanically activated fibroblasts quickly begin to secrete components of the ECM and initiate a positive-feedback loop where, as more ECM is secreted, cells proliferate into the restored volume. As the tissue is expanded, angiogenesis increases to replenish the blood and nutrient supply to the de novo tissue.

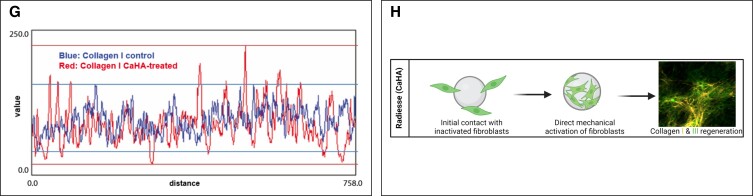

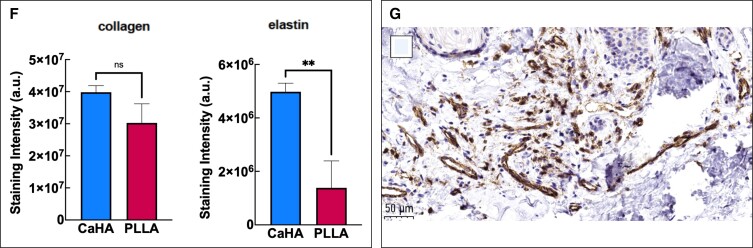

Regenerated Components of the Skin

Mechanotransduction of dermal fibroblasts leads to a variety of cellular, mechanical, and biophysical changes in the skin. A variety of clinical and in vivo studies have shown that CaHA-R significantly regenerates collagen I and collagen III.46,47,83 Casabona et al detected mean collagen fibers in a defined region of interest and found that both collagen I and III were significantly increased in CaHA-treated patients.73 Patients treated with a 1:1 dilution had approximately 650,000 collagen fibers, while the control group had roughly 250,000, equating to a 160% increase in total collagen. In another study, Yustkovskaya and Kogan showed significant increases in collagen I and elastin at 4 and 7 months posttreatment and observed a significant increase in collagen III at 4 months, which decreased by Month 7 (Table 2).46 The role of collagen I and collagen III are critical to skin function, and discrepancies and ratios between the types of collagen are seldom discussed in aesthetics. In skin, collagen III plays a critically important role in stabilizing collagen I fibers during fibrillogenesis and maturation of the ECM.84 Ideally, as skin regenerates, collagen III is gradually replaced by collagen I. Zerbinati and Calligaro documented collagen turnover in CaHA-treated patients using Picrosirius red staining and circularly polarized microscopy, finding that after CaHA treatment an abundance of collagen III fibers were synthesized and gradually replaced by mature collagen I fibers (Figure 4A, B).85 In the untreated group, the proportion of “old” (610-700 nm wavelength) and “new” (510-580 nm wavelength) collagen was 40.59% and 1.76%, respectively, while in the CaHA-treated group, the proportion of “old” and “new” collagen was 15.54% and 34.42%, respectively. Another Yutskovskaya et al study observed significant increases in collagen I and collagen III at 8 and 12 months posttreatment with diluted CaHA-R in the neck and chest.47

Table 2.

Histological Changes in Collagen I, Collagen III, and Elastin Staining Scores at Baseline and at 4 and 7 Months Post-CaHA Treatment46

| Protein | Stain intensity (baseline) | Stain intensity (M4) | Change from baseline to M4 (%) | P-value | Stain intensity (M7) | Change from baseline to M7 (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen I | 4.29 | 4.95 | 14.29% | 0.04 | 6 | 33.24% | <0.00001 |

| Collagen III | 2.38 | 5.26 | 75.39% | <0.00001 | 2.59 | 8.46% | NS |

| Elastin | 2.24 | 2.95 | 27.36% | <0.05 | 3.88 | 53.59% | <0.00001 |

CaHA, calcium hydroxylapatite; M, month; NS, not significant.

Figure 4.

CaHA-R regenerates different components of the skin. (A, B) Evidence of collagen turnover reveals the formation of new collagen after 2 months in vivo. (C) Histologic stains show significant increases in elastin. (D) Histologic stains show significant increases in proteoglycans (top), and rete ride depth (bottom) after treatment with CaHA. (E, F) Split-arm comparison of Sculptra (Galderma, Lausanne, Switzerland) and CaHA-R shows similar rates of collagen formation and higher staining intensity for elastin fibers with CaHA-R. (G) Anti-CD31 antibody staining revealing an abundance of neovasculature in the deep dermis, 1 month postinjection of CaHA. CaHA, calcium hydroxylapatite; CaHA-R, calcium hydroxylapatite (Radisesse; Merz Aesthetics, Raleigh, NC); PLLA, poly-L-lactic acid. Figure 4A, B is reproduced with permission from Zerbinati and Calligaro (2018).85 Figure 4C, D is reproduced with permission from González and Goldberg (2019).86 Figure 4E, F is reproduced with permission from Mazzuco et al (2022).87 Figure 4G is reproduced with permission from Shalak OV, Satygo EA, Deev RV, Presnyakov EV, The Effectiveness of Radiesse in Dental Practice for Prevention and Non-Surgical Treatment of Gum Recession. Her North-West State Med Univ Named II Mechnikov. 2023, Volume 14, Issue 4, pages 43-52; use permitted under the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Although regeneration of collagen has been the primary focus for regenerative aesthetics, more components of the ECM are involved in the aging equation. As previously mentioned, elastin plays a critically important role in aging, and its loss is the primary cause of skin laxity.54,88 As endogenous elastin is depleted, the skin undergoes permanent, nonlinear elastic deformation that results in “sagging” skin that lacks pliability.54 Through anecdotal observations in improvement of skin laxity, it was hypothesized that CaHA-R may restore elastin in the skin. Yutskovskaya and Kogan measured changes in elastin following multiple subdermal injections of diluted CaHA-R in otherwise healthy patients and observed that significant neoelastin formation was achieved 4 months posttreatment, regardless of the dilution ratios.46 In this study, mean elastin staining intensity (scaled from 0 to 8) improved from 2.24 at baseline to 2.95 and 3.88 at Months 4 and 7, respectively, an approximate 73% increase (Table 2). Increases in elastin were correlated with increases in collagen I, suggesting a common underlying regenerative mechanism.

In a follow-up study, Yutskovskaya et al treated the neck and chest with varying dilutions of CaHA-R and stained for changes in elastin, observing significant increases in elastin at 8 and 12 months posttreatment, respectively, with morphological assessments improving from a score of 1 at baseline to 3.6 and 5.4 at Months 8 and 12, respectively.47 González et al further evaluated the effects of CaHA-R on elastin formation in 15 patients after 180 days of treatment and observed significant elastin increases that ranged from 29% to 179% (Figure 4C).86 In a split-arm study, patients were treated with PLLA in the left arm and 1:3 hyperdiluted CaHA in the right arm.87 Both arms underwent punch biopsies and staining for collagen and elastin. Although no quantitative analysis was carried out, histologic slides show many thick neoelastin bands in the CaHA-R-treated arm and a single elastin fiber in the PLLA-treated arm, similar amounts of collagen I between groups, and fewer immune cells at the injection site in the CaHA-R group 2 months after the last treatment session. A post hoc analysis analyzing fluorescent intensity showed the CaHA-R-treated side had more than 6 times the fluorescent intensity on the elastin staining (Figure 4E, F).89 Differences in the synthesis of elastin relative to other regenerative treatments may be due to the direct mechanotransduction of fibroblasts, which is distinct to CaHA.

Other components of the skin ECM are glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans.90 Proteoglycans have a variety of functions in the skin ECM, ranging from cell restoration, hydration, prevention of superficial wrinkling, and improvement in skin smoothness and texture.90,91 Proteoglycans interact directly with endogenous HA and collagen fibers and, although seldom discussed in the context of aesthetic medicine, are worth evaluating as potential therapeutic targets and measures for skin improvement. To this end, 2 studies have evaluated the proteoglycan synthesizing effect of CaHA-R. Erdogmuş et al conducted an in vivo rabbit study investigating the response and survivability after implantation of block cartilage with and without CaHA.92 Chondrocyte viability and proliferation, collagen content, elastin content, and proteoglycan content were evaluated histologically. In the groups treated with CaHA, viability, proliferation, collagen, and elastin content were elevated, consistent with previous reports. However, Erdogmuş et al were the first to demonstrate significant increases in matrix proteoglycans. Using a 4-point scale (0% = 0 points, >0%-25% = 1 point, >25%-50% = 2 points, >50%-75% = 3 points, >75%-100% = 4 points), the group found that CaHA-treated groups achieved a mean score of 2.42/4 and control groups (with only implanted cartilage) achieved a mean score of 1.92/4.92 In an investigation of proteoglycan formation in human subjects, González and Goldberg made similar observations;86 6 months after treatment with CaHA-R, patients had 65% to 839% increases in proteoglycan content, with a mean percent change of 76.27% (Figure 4D). This increase in proteoglycan content was hypothesized to play a short-term role in superficial and structural improvements in the skin.

Although not considered part of the ECM, angiogenesis is another marker for tissue regeneration because newly formed tissue is typically accompanied by neovascularization.92 New vessels are critical for supporting regenerating tissue with blood and other circulatory nutrients, as well as for the continued regeneration of new tissue. It is therefore useful to evaluate the angiogenic effect of regenerative fillers as a proxy for new tissue formation. Yutskovskaya et al compared the angiogenic effect of Juvéderm Voluma and CaHA-R in humans and observed a significant difference in mean scores of angiogenesis, with HA gel reaching a mean score of 0.2 and CaHA reaching a mean score of 1.0 at Month 4.76 By Month 9, HA reached a score of 1.1 while CaHA reached a score of nearly 3.5. In another study, Yutskovskaya et al measured CD34 expression as a proxy for angiogenesis as CD34 is an endothelial marker for newly formed vessels. Mean scores for angiogenesis increased 1 to 2 points from baseline at Month 8 and up to 5.2 points by Month 12 (on a 6-point scale) in patients treated with diluted or hyperdiluted CaHA.46 In a follow-up study, Yutskovskaya et al again measured CD34 at 4 and 7 months posttreatment and observed significant changes in CD34 expression at both time points. CD34 expression increased from 3.62 at baseline to 4.63 and 5.53 at Months 4 and 7, respectively, marking an overall increase of 53%.47 In a study investigating the regenerative role of CaHA-R for gumline restoration, Shalak et al observed significant changes in neovasculature 1, 6, and 12 months following CaHA-R injection, which correlated with significant increases in blood flow volume and velocity.85 Anti-CD31 antibody staining allows for visualization of new vasculature 30 days after treatment (Figure 4G). The new vasculature was further correlated with significant tissue regeneration, collagen production, and epidermal thickening. Taken together, these studies have demonstrated significant and robust angiogenesis and neovascularization induced by CaHA-R treatment, regardless of the dilution rate of the product.

Restoration of Structure and Function of the Skin

Evidence thus far has documented the robust regeneration of multiple ECM components, the expansion and proliferation of fibroblasts and keratinocytes, and the induction of new vasculature resulting from CaHA-R treatments. Regeneration of these components provides the foundation for viewing CaHA-R as a regenerative aesthetic treatment, but ensuring the restoration of function in regenerated tissue is also of primary importance when analyzing the regenerative capacity of a biomaterial. For example, it is possible to regenerate a portion of a tissue yet fail to restore its function. Such a challenge continues to plague biomedical engineers and clinicians working in regenerative medicine. Several studies have evaluated the capacity of CaHA-R to restore components of the ECM and of tissue as well as the restoration of structure and function of the skin.

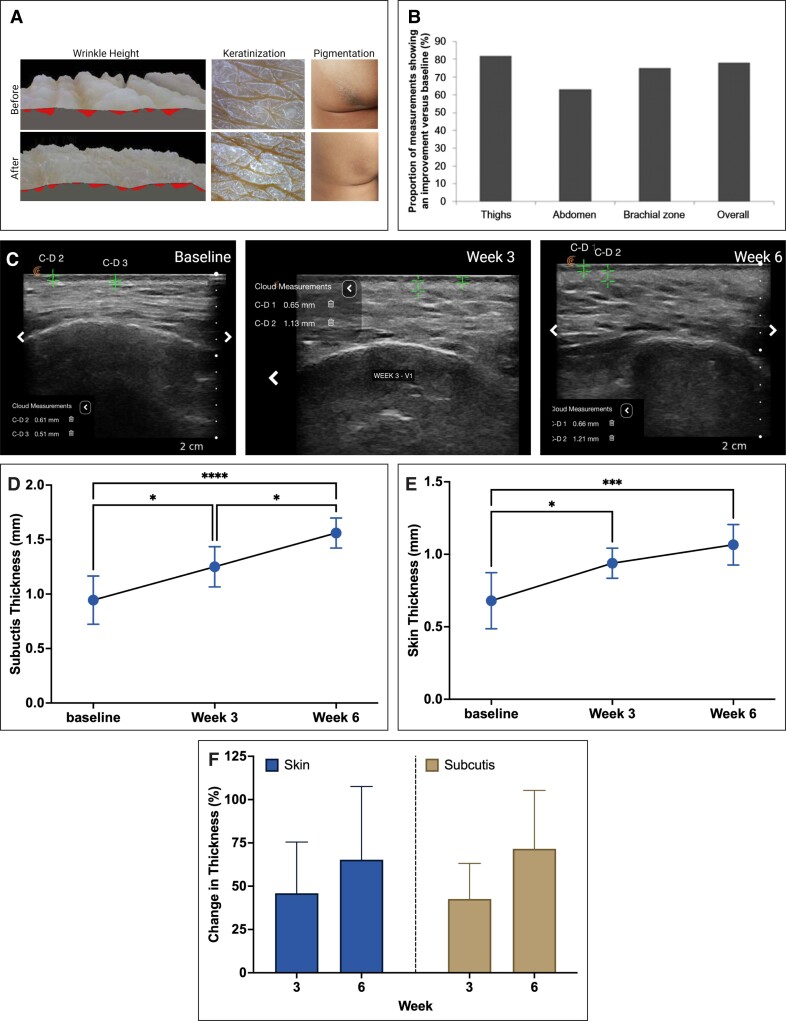

Structural restoration has been observed both superficially and across different layers of the skin. Kim measured superficial changes in skin wrinkles using a dermatoscope and computed triangulation.72 Before treatment with diluted CaHA-R, the sum of triangle areas (a measure of wrinkle depth) was 366; 7 months after treatment, the sum decreased to 231.5. Further, the depressions in the skin improved from 3.03 to 1.53 on a 4-point scale (with lower scores indicating flatter surfaces). Finally, the discoloration index improved from 2.59 to 1.96 on a 4-point scale (with lower scores indicating less discoloration). Thus, treatment with CaHA-R decreased the depth of the wrinkles in the skin, alleviated roughness associated with keratinization, and improved discoloration (Figure 5A). All observed changes were superficial, despite the deep epidermal injection planes.

Figure 5.

CaHA-R can restore the structure and function of skin. (A) Results from a clinical study administering multiple layers of CaHA-R show significant reduction in wrinkles (left), significant reduction in keratinization (middle), and significant improvements in discoloration (right). (B) Cutometric analysis of CaHA-R-treated skin shows improvements in skin mechanical properties in the thighs, abdomen, and brachial zone. (C-F) Ultrasound analysis shows significant increases in the thickness of the skin and the subcutis 3 and 6 weeks after a single CaHA-R treatment. (G) In vitro study measuring fibroblast contractile force (left) in normal or wrinkled fibroblasts with CaHA revealed the restoration of contractile forces in wrinkled fibroblasts to the level of normal fibroblasts and the attainment of supraphysiological contractile forces in normal fibroblasts treated with CaHA. The changes in contractile force were consistent throughout the duration of the study. CaHA, calcium hydroxylapatite; CaHA-R, calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse; Merz Aesthetics, Raleigh, NC); NF, normal fibroblast; WF, wrinkle fibroblast. Figure 5A is reproduced with permission from Kim (2019).72 Figure 5B is reproduced with permission from Wasylkowski (2015).93 Figure 5F, G is reproduced with permission from Courderot-Masuyer C, Robin S, Tauzin H, Humbert P. Evaluation of Lifting and Antiwrinkle Effects of Calcium Hydroxylapatite Filler In Vitro Quantification of Contractile Forces of Human Wrinkle and Normal Aged Fibroblasts Treated with Calcium Hydroxylapatite. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2016, Volume 15, Issue 3, pages 260-268, with permission from John Wiley & Sons (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com).

To date, there is no definitive mechanism to explain how deeper injections may stimulate changes in the epidermis, although several hypotheses have been explored. Combinatorial effects on angiogenesis and proteoglycans may hydrate and nourish even the epidermis, despite their distance when injected supraperiosteally or subdermally.72 Another recent hypothesis suggests that stimulation of fibroblasts, in this case via cell-material interaction, may result in an increase of fibroblast growth factors, which may either bind to receptors in the epidermis or promote the acquisition of epidermal growth factors.94-96 The latter may warrant further investigation as there may be intricate interactions between epidermal and dermal remodeling, largely modulated by fibroblast activation or lack thereof.

Gonzalez et al demonstrated an interesting histomorphological observation. Changes in the number and depth of rete ridges increased dramatically following CaHA-R treatment.86 In normal skin, the rete ridges are interdigitations between the epidermis and dermis and play a role in adhering the different layers of the skin.97 In healthy, young populations, rete ridges are deep and plentiful. With age and/or sun damage, the rete ridges tend to flatten, which is accompanied by decreases in skin mechanical properties.98 Similar changes in rete ridge peg count and depth can be observed in several histologic studies, and indicate dermal/epidermal remodeling and restoration of skin biomechanics following CaHA-R treatment.46,47

The saying “form follows function” implies that the design of a material is meant to optimize its desired function. This is true in much of dermatology and biomechanics and can be readily seen in skin and its mechanics. One method to measure the restoration of skin function is by measuring changes in its mechanical and viscoelastic properties via cutometric analysis. Two studies have evaluated macroscale changes in skin mechanical properties using cutometry. Wasylkowski evaluated changes in skin mechanical properties in the abdomen, thighs, and brachial zone after treatment with diluted CaHA-R.93 Flaccidity, skin density, skin thickness, and mean self-assessed flaccidity scores all improved across all anatomies treated (Figure 5B). Cutometric analysis showed improvements in skin flaccidity in 78% of cases only 5 weeks after treatment, indicating a significant skin-tightening effect.

A more comprehensive mechanical analysis was conducted by Yutskovskaya and Kogan, who used both ultrasound scanning and cutometry to assess biomechanical changes in the skin.46 The cutometer measured immediate deformation (skin extensibility, Ue), delayed distension (Uv), final deformation (Uf), and final retraction (Ua), with elastic recoil (Ua/Uf) and viscoelastic ratio (Uv/Ue). Both Ua/Uf values closer to 1 and smaller Uv/Ue values represent higher elasticity. Results showed an increase in skin elasticity over 3 visits, with increasing Ua/Uf from 0.57 at baseline to 0.66 and 0.73 at Months 4 and 7, respectively. Similarly, Uv/Ue decreased from baseline to 0.66 and 0.53, indicating improvements in elasticity, despite the viscoelasticity remaining constant (Table 3). This biomechanical analysis showed increased elasticity and improved pliability after 2 treatments of diluted CaHA with a subsequent ultrasound demonstrating significant increases in the thickness of the dermis at both 4 and 7 months (Table 4). These macroscale mechanical studies correlate with the histologic confirmation of regenerated elastin and ultrasonographically confirmed changes in dermal thickness. A similar increase in skin and subcutis thickness was observed by Theodorakopoulou et al, who investigated the regenerative effects of CaHA diluted 1:1 with an amino acid diluent injected into the midface. In addition to improving skin quality and radiance, they found significant increases in skin and subcutis thickness 3 and 6 weeks after a single treatment (Figure 5C-F).99 These changes correlated to significant improvements in skin luminosity and decreases in wrinkle severity and midface hollowness.

Table 3.

Changes in Skin Mechanical Properties Following 2 Treatments With Diluted CaHA at Baseline, 4 Months Posttreatment, and 7 Months Posttreatment46

| Measure | Ratio (baseline) | Ratio (M4) | Change from baseline to M4 (%) | P-value | Ratio (M7) | Change from baseline to M7 (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elastic recoil (increase = improvement) | 57 | 66 | 14.63% | <0.05 | 73 | 24.62% | <0.00001 |

| Viscoelastic ratio (decrease = improvement) | 66 | 53 | 21.85% | <0.05 | 50 | 27.59% | <0.05 |

CaHA, calcium hydroxylapatite; M, month.

Table 4.

Ultrasound Scan Values Demonstrating a Significant Increase in Dermis Thickness After CaHA Treatment46

| Component | Thickness at baseline (mm) | Thickness at M4 (mm) | Change from baseline to M4 (%) | P-value | Thickness at M7 (mm) | Change from baseline to M7 (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epidermis | 169.5 | 171.1 | 0.76% | NS | 157.1 | 7.77% | NS |

| Dermis | 1462.3 | 1642.8 | 11.63% | <0.01 | 1865.9 | 24.25% | <0.0001 |

CaHA, calcium hydroxylapatite; M, month; NS, not significant.

Finally, a fundamental cellular mechanics study conducted by Courderot-Masyer et al examined changes in contractile forces of normal and wrinkled fibroblasts with and without CaHA while investigating its ability to restore or improve fibroblast functionality.68 As discussed previously, the ability of fibroblasts to contract significantly modulates their internal tension, which in turn regulates their mechanoreceptors, contact with collagen, and metabolic state. A collagen lattice populated with wrinkled human dermal fibroblasts (WFs) as well as normal fibroblasts (NFs) was attached to a mechanical testing device that measures contractile force as a function of resistance. In the first set of experiments, it was confirmed that WFs exert significantly less contractile force than NFs. Next, NFs were cultured with CaHA and retested in the collagen lattice. The addition of CaHA to NFs significantly increased their contractile forces for the duration (24 hours) of the experiment, indicating that even healthy, undamaged fibroblasts can significantly increase their contractile force and possibly ECM production with CaHA treatment. Similarly, WFs treated with CaHA produced significantly more contractile force than untreated WFs. When a between-group analysis was conducted, it was revealed that WFs treated with CaHA achieved a similar contractile force as NFs alone. Profoundly, the addition of CaHA restored the cellular function of damaged/aged fibroblasts to the same functional capacity as healthy fibroblasts and, further, improved the function of healthy fibroblasts to a supraphysiological level (Figure 5G).

The restoration of different structures of the skin, from the epidermis, rete ridges, and dermis, is accompanied by confirmed recovery of tissue function via improved mechanical properties, thickness, elasticity, and pliability. These functional improvements are, in large part, explained by the regeneration of ECM proteins and further explained by the contractile force restoration enabled by CaHA treatment.

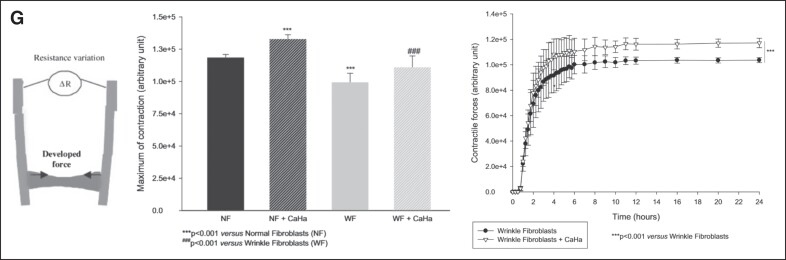

IMMUNE RESPONSE

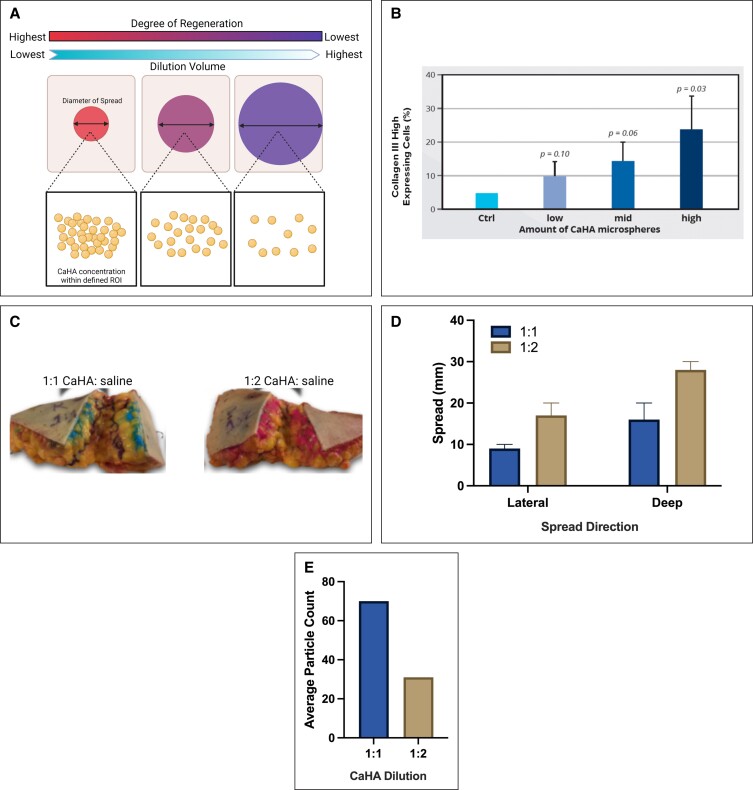

In general, when an exogenous material is implanted, it activates a variety of immune responses which vary by filler type, composition, and a patient's immune status. The material, size, and homogeneity of particles largely modulate portions of the adaptive immune system.30,42 While little can be done to mitigate transient inflammation more closely associated with damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), it may be desirable to mitigate chronic inflammation following injection. CaHA is largely considered immunologically inert, with minimal immune cell recruitment and activation.48,49 This may be somewhat expected, as bioceramics are generally regarded as very immunologically inert.100 Lemperle et al noted in one histological study that CaHA did not form granulation tissue or elicit significant foreign body responses.48 Granulation tissue, more associated with wound healing, is generally characterized by de novo collagen and a variety of inflammatory cells.101 Berlin et al assessed the immunohistochemical response to CaHA injected in the face and found that only a mild histiocytic response was achieved, with peripheral macrophage and foreign body giant cell (FBGC) activation.49

In another histologic study, Marmur et al observed scant or no inflammatory response to the filler after 1 month, although macrophages and FBGCs were detected within the injection region (Figure 6A).102 By Month 6, significant increases in collagen were observed despite the noted lack of immune cells. However, although the CaHA was homeostatically degraded, it was observed that macrophage-mediated phagocytosis was the primary clearance mechanism (Figure 6B). Notably, the long-term degradation driven by macrophage subtype polarization to M2 macrophages may serve to further drive a regenerative response as the CaHA is broken down. M2 macrophages are known to play a significant role in tissue regeneration and may be beneficial.103 The activation of immune cells with CaHA is notably different from those of other fillers, as Berlin et al pointed out; early macrophage activation to CaHA is minimal, whereas early macrophage activation following PLLA and HA gels may be more significant.49,81 Zerbinati and Calligaro observed almost no immune cell activation following CaHA treatment, noting that no inflammation or granulation tissue formation was associated with the filler implantation, and that the treatment was safe, regenerative, with no immune system stimulation.85

Figure 6.

Immunological response to CaHA-R. (A) Scant inflammatory cell activation both 1 and 6 months after CaHA-R treatment, despite the increase in collagen staining intensity (blue). (B) Evidence of eventual macrophage-mediated breakdown of CaHA microspheres. (C) Hematoxylin and eosin stains of the same magnification from a CaHA-R-treated and PLLA-SCA-treated arm show profound differences in immune cell infiltration at injection site. (D) Proposed gradient on particle morphology and its role in regulating inflammation. The smoother and more homogeneous a particle, the less inflammatory. (E) Scanning electron microscopy images of CaHA-R microspheres and (F) PLLA-SCA flakes reveal dramatic differences in size, shape, surface irregularities, and phagocytosable materials. (G) Significant differences in proinflammatory cytokine release from M1 macrophages cultured with CaHA and PLLA, demonstrating the minimal inflammatory potential of CaHA. CaHA, calcium hydroxylapatite; CaHA-R, calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse; Merz Aesthetics, Raleigh, NC); MIP1a, macrophage inflammatory protein 1α; PLLA, poly-L-lactic acid; PLLA-SCA, poly-L-lactic acid (Sculptra; Galderma, Lausanne, Switzerland); TNFRII, tumor necrosis factor receptor II. Figure 6A is reproduced with permission from Marmur et al (2004).102 Figure 6C is reproduced with permission from Mazzuco et al (2022).87 Figure 6D is reproduced with permission from Baranov et al (2021).42 Figure 6E is reproduced with permission from Oh et al (2021).105 Figure 6F is reproduced with permission from Kim (2019).72

The lack of immune cell activation associated with CaHA fillers further supports the mechanotransduction hypothesis for tissue regeneration, especially when comparing with PLLA, which is observed to not only initiate M1 macrophage polarization short-term, but also to recruit a variety of immune cells, such as neutrophils, FBGCs, and T cells, to the injection site and result in a chronic inflammatory response more associated with fibrotic wound healing.81 In the Mazzuco et al split-arm study comparing PLLA and 1:3 CaHA, a post hoc analysis on the hematoxylin and eosin stains revealed that PLLA recruited significantly more immune cells to the injection site than did CaHA (Figure 6C).89 One explanation for this phenomenon may be the morphology of the particles in each filler; several studies have demonstrated that particle shape homogeneity and the lack of surface irregularities are vital in reducing an inflammatory response.16,42,104 As summarized by Baranov et al, complex geometries, surface irregularities, and uneven particle shape and size distributions can increase the recruitment of neutrophils and other immune cells, thus leading to a sustained inflammatory response.42 In particular, IL-1β secretion can be directly regulated by particle shape (Figure 6D). Scanning electron microscopy revealed that PLLA-SCA particles appear as nonhomogeneous, spiky particles with vast shape and size discrepancies (Figure 6F), while CaHA particles appear uniform in shape, size, and smoothness (Figure 6E).72,105 Further evidence demonstrating the distinctly different MOAs between CaHA and PLLA revealed significant differences in inflammatory cytokine expression. Different dilutions of CaHA and PLLA were seeded into primary samples of M1 and M2 macrophages and a subsequent inflammation array and confirmatory enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay were conducted. The results from this study demonstrated that stimulation with PLLA, but not CaHA, resulted in increases in the proinflammatory M1 cytokines CCL1, MIP1a, and TNFRII (Figure 6G). These differences suggest a low inflammatory potential for CaHA relative to PLLA, and further support the inflammatory neocollagenic effect of PLLA relative to the mechanotransductive MOA of CaHA.106

Several unique features of the CaHA manufacturing process contribute to its immunological inertness. Because it is not bacterially derived, it does not contain any pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) to stimulate the immune response. PAMPs and DAMPs are mechanisms that facilitate the innate immune response to rapidly respond to “danger” signals without recruitment of the slower, but more specific, adaptive immune response.107 HA fillers are known to contain bacterial proteins, as reported on their product information labels, and these may serve as the “danger” signal that is required to initiate an immune response.108 Furthermore, CaHA and bioceramics in general do not stimulate toll-like receptors or inflammatory cytokine signaling to the extent that other implantable fillers do due to their similarity to endogenous hydroxylapatite. Although any foreign material can stimulate an immune response, CaHA is less inflammatory than HA fillers and PLLA as reported in numerous studies.76,106 Other features of HAs may play a role in propagating an immune response, including the extent of cross-linking, injection in more superficial planes, and closer proximity to heavily immune-surveilled areas (eg, the lips and under the eyes). Materials that are placed deeper (eg, supraperiosteally) may likewise produce a subclinical inflammatory immune response, but they do not reach clinical significance since they are relatively hidden by a greater amount of overlying tissue. Emerging evidence has demonstrated that most, if not all, HA fillers undergo pseudocapsule formation, which initially can protect it from an inflammatory immune response; however, as that pseudocapsule breaks down it exposes more antigen that can be processed by dendritic cells and subsequently drive delayed-onset adverse events, including granuloma formation.109,110 Although CaHA may also undergo nodule formation, this is typically due to product accumulation from poor technique rather than true granuloma formation.

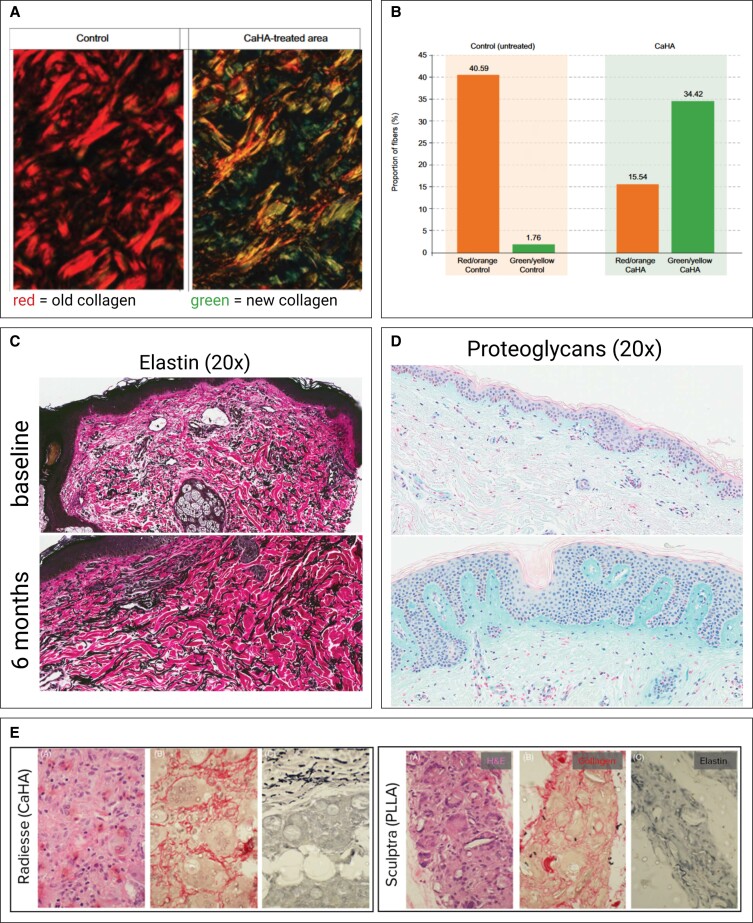

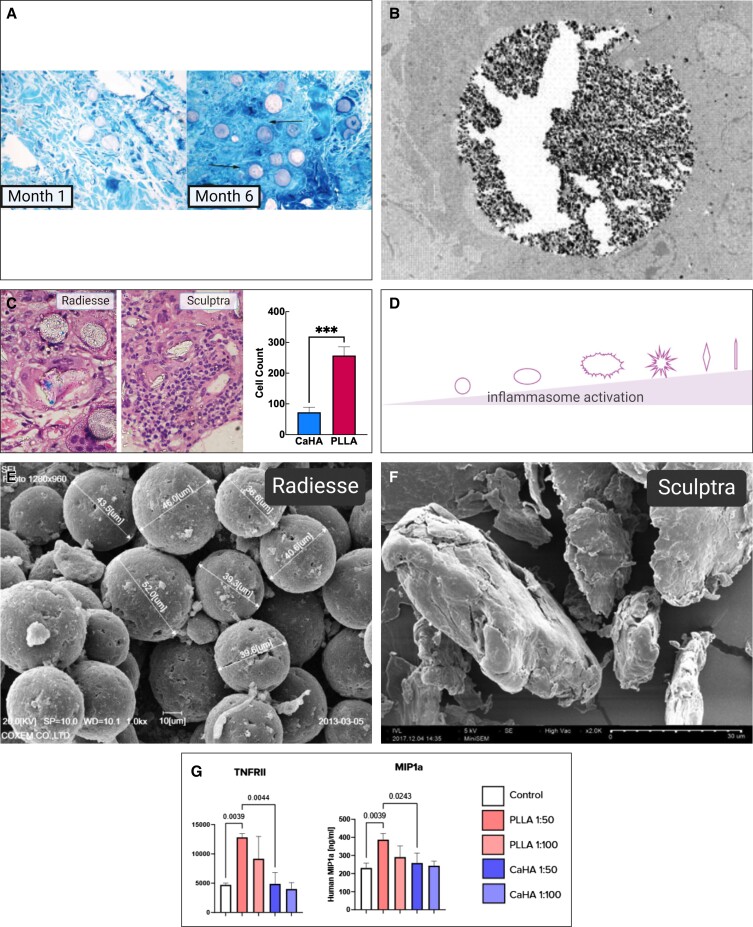

DILUTE AND HYPERDILUTE CaHA-R

When undiluted, CaHA-R is commonly used for supraperiosteal injection aiming to augment boney morphologies such as the jawline or cheek. In the past several years, however, use of CaHA-R in a diluted or hyperdiluted form has increased tremendously. Diluted Radiesse (DR) is considered a 1:1 dilution, with hyperdiluted Radiesse (HDR) considered any dilution >1:1. Although there are several advantages to diluting or hyperdiluting CaHA-R, optimal regeneration occurs at a 1:1 dilution because fibroblasts need space between particles to migrate and interact with the microspheres.73,77 Increasing dilutions decreases the rheology of the filler, and therefore decreases complications, making postinjection inflammation significantly less likely by reducing the mechanical load on the skin. Diluting CaHA-R decreases the rheological properties to near that of blood, making vascular clearance in the case of an occlusion easier to achieve. As mentioned previously, fillers can be diluted from high G′ to lower G′ values; however, the reverse is not possible. Therefore, clinicians can and do vary their dilution ratios with great subjectivity to better optimize the look and feel of the patient's skin at a given anatomic location. This versatility expands into the spread of the microspheres as well. In general, the spread increases from CaHA-R to DR to HDR at increasing dilutions. It is important to consider that increasing the dilution of the filler will lead to a greater lateral and deep spread of the product, meaning more tissue will be treated, but to a lesser degree (because the microspheres are less dense at any given region of interest) (Figure 7A). This facilitates activation of fibroblasts in deeper tissue planes without the need for placing a needle or cannula into those deeper tissue planes, thereby mitigating risk in some instances.

Figure 7.

Dilute and hyperdilute CaHA-R. (A) The spread and regeneration mechanism of diluting CaHA-R. Increasing dilutions stimulate a larger volume of tissue, but to a lesser degree. (B) In vitro study demonstrating the dilution-dependent synthesis of collagen III. (C) Differences in spread of 1:1 and 1:2 CaHA:saline–treated abdominal tissue reveal a near-linear (D) increase in filler spread and (E) a decrease in microsphere count. CaHA, calcium hydroxylapatite; CaHA-R, calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse; Merz Aesthetics, Raleigh, NC).

Nowag et al investigated the dilution-dependent regenerative effect of CaHA-R and found that the quantity of collagen III–expressing cells increased with increasing amounts of CaHA microspheres. Similarly, the degree of de novo collagen III decreased with increasing dilutions (Figure 7B).83 This finding is also supportive of the regenerative MOA being driven by cell-biomaterial interactions. When investigating the spread kinetics of different dilutions in human abdominal fat, the average lateral spread of DR (1:1) and HDR (1:2) was approximately 9 and 17 mm, respectively. The average deep spread of DR (1:1) and HDR (1:2) was approximately 16 and 28 mm, respectively (Figure 7C, D).111 Relatedly, the average number of particles linearly decreased with increasing dilution (Figure 7E). Therefore, increasing the dilution will disperse the microspheres to a larger tissue volume, but regenerate it to a lesser degree. Clinically, significant volumization and regeneration has been observed with dilutions up to 1:6, although increasing dilution may necessitate more treatments.46,112 This study served to help approximate product spread as a function of dilution. As dilute-hyperdilute CaHA is more frequently used in body contouring, further optimization of HDR is warranted.

COMPARISON OF DIFFERENT CaHA-CONTAINING FILLERS

CaHA-R was the first, and is so far the only, CaHA-containing filler with FDA approval, but a variety of other CaHA-containing fillers are used around the world and vary in their compositions, particle morphology, and biological response. Although comparisons between different CaHA-containing fillers are sparse, the literature supports the presence of CaHA driving a regenerative response in vitro and in vivo.

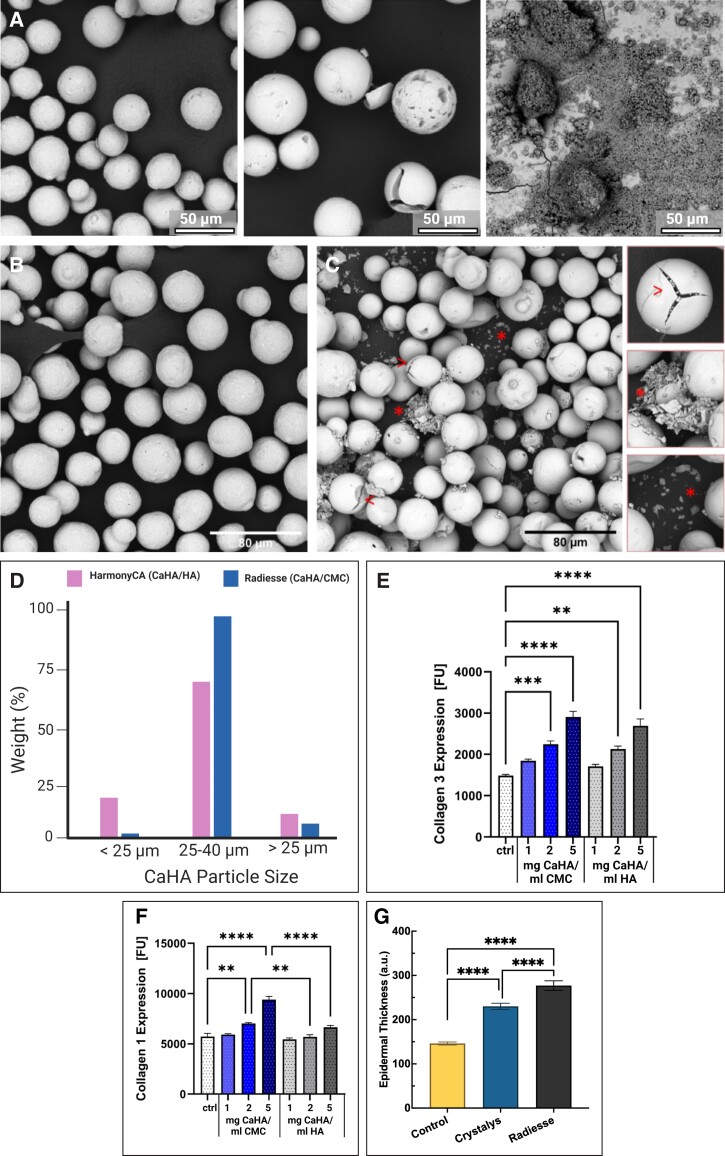

Backfisch et al compared the morphological and mechanical features of CaHA-R (CaHA/CMC), HArmonyCA (CaHA-H [CaHA/HA], Allergan Aesthetics, an AbbVie Company, Irvine, CA), and Neauvia Stimulate (CaHA-N [CaHA/PEG], MatexLab SA, Lugano, Switzerland).40 In the first set of experiments, the CaHA components were isolated from each gel carrier and imaged with electron microscopy, revealing the CaHA in CaHA-R to be smooth and spherical microspheres that were largely defect free, CaHA-H CaHA appeared as microspheres with fragments and fissures or holes in the majority of particles, and that the CaHA in CaHA-N were small crystalline fragments less than 500 nm in size (Figure 8A). In the second set of experiments, the rheological properties of the 3 formulations were measured. At 1 Hz, the G′ values of CaHA-R, CaHA-H, and CaHA-N were around 1400, 120, and 80 Pa, respectively. However, the extrusion forces appeared unrelated to the G′ of the fillers: CaHA-R had the lowest extrusion force of 19 N, followed by CaHA-N at 23 N, and finally CaHA-H at 25 N. This phenomenon is perhaps explained by the shear-thinning behavior of CMC, as reviewed in the material section.

Figure 8.

Comparisons between different CaHA-containing dermal fillers. (A) Scanning electron microscopy images of CaHA-R (left), HArmonyCA (middle), and Neauvia Stimulate (right) show differences in size, shape, and homogeneity between CaHA components of each filler. (B) Scanning electron microscopy images of CaHA-R and (C) HArmonyCA show differences in stability and particle consistency as well as (D) size distribution. (E) Effects of different concentrations of CaHA-R (blue) and HArmonyCA (grey) on collagen III and (F) collagen I expression. (G) Epidermal thickness of rats 16 weeks after treatment with either saline (control), Crystalys, or CaHA-R. CaHA-R, calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse; Merz Aesthetics, Raleigh, NC).

In another study, Kunzler et al compared and evaluated the morphological effect of CaHA-R and CaHA-H on collagen generation in vitro.113 When the CaHA microspheres were isolated from their respective carrier gels, the CaHA from CaHA-R appeared largely defect free, whereas the CaHA from CaHA-H was riddled with defects that included small, fragmented particles, surface cracks, holes, and fissures (Figure 8B, C). Additionally, it appeared that the size distribution of CaHA-R microspheres was significantly tighter than that of CaHA-H, which had a larger percentage of CaHA microspheres <25 µm in diameter (Figure 8D). When the fillers were examined in their carrier gels, no visible defects were noted with CaHA-R, but a variety of broken particles appeared embedded in the HA polymer matrix of CaHA-H. When both CaHA-R and CaHA-H microspheres were cultured with primary human fibroblasts at different concentrations for 7 days, collagen III expression was significantly increased with both CaHA-R and CaHA-H microspheres at 2 and 5 mg/mL (Figure 8E). However, only CaHA-R microspheres resulted in a short-term increase in collagen I, which occurred at both 2 and 5 mg/mL (Figure 8F). The findings from this study demonstrate that there are morphological differences between the 2 CaHA-containing fillers, that the CaHA microspheres of both fillers results in de novo collagen III synthesis, but only CaHA from CaHA-R significantly increased collagen I expression within the study time frame.

In a recent study, Mogilnaya et al compared two CaHA-containing fillers, CaHA-R and Crystalys (CaHA-C; Luminera, Lod, HaMerkaz, Israel) in a rat model.114 Forty-eight rats were injected with either CaHA-R, CaHA-C, or sterile water intradermally and evaluated at 2, 4, and 16 weeks. At Week 16, histologic samples confirmed that both the CaHA-containing groups had significantly thicker epidermal layers relative to the control group (Figure 8G). Notably, the CaHA-R-treated group had significantly thicker epidermises than the CaHA-C group. Additionally, the size of the nuclei of stained epithelial cells increased significantly for CaHA-R-treated rats, but not in CaHA-C- or saline-treated rats. Nuclei size is related to the amount of gene expression and protein production. The authors hypothesize that this change had to do with the increased fibrillar protein noted in the CaHA-R group at Week 2. From this study, it is clear that CaHA-containing fillers elicit an increase in epidermal thickness and modulate epithelial nuclei, as well as produce fibrillar components of the ECM.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND LIMITATIONS

Regenerative aesthetics is relatively new, and various products are not yet intricately differentiated. Further studies investigating and comparing differences between injectable regenerative and biostimulatory treatments might help clinicians improve treatment paradigms. Synergistic use with regenerative adjuvants (ie, platelet-rich plasma, exosomes,115 mesotherapies,99 etc) is emerging as a common and efficacious practice. Due to the flexibility of preparation, CaHA-R may be used with other regenerative suspensions and/or treatments on the basis that initiating multiple regenerative pathways may enhance the effect of the treatment. Research is needed to quantify and substantiate the efficacy of such treatments and regulatory bodies have different laws on the injection of such adjuvants. Nevertheless, innovative treatments are growing in popularity.

This review article has several limitations. First, it is not a meta-analysis or a systematic review. Instead, this narrative review consists of the scientific and clinical interpretation of previously published works which were aggregated based on keyword searches from a variety of publication libraries. In addition, because this review focuses on the MOA and supporting evidence of soft tissue regeneration, no clinical recommendations or protocols are presented, although many are cited. Given the scope of this article, the potential risks and prevalence of adverse events are not thoroughly covered. Future meta-analyses should aim to quantify the efficacy of CaHA-R in a regenerative context, evaluate its impact on patients, and summarize the risk profile and most common adverse events at each common dilution used. Despite these limitations, this article offers a scoping review that begins with individual material properties and expands into evidence of the restoration of structure and function of soft tissue post CaHA-R treatment in a succinct way.

CONCLUSIONS