Abstract

Background:

Child maltreatment leads to substantial adverse health outcomes, but little is known about acute health care utilization patterns after children are evaluated for a concern of maltreatment at a child abuse and neglect medical evaluation clinic.

Objective:

To quantify the association of having a child maltreatment evaluation with subsequent acute health care utilization among children from birth to age three.

Participants and setting:

Children who received a maltreatment evaluation (N = 367) at a child abuse and neglect subspecialty clinic in an academic health system in the United States and the general pediatric population (N = 21,231).

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective cohort study that compared acute health care utilization over 18 months between the two samples using data from electronic health records. Outcomes were time to first emergency department (ED) visit or inpatient hospitalization, maltreatment-related ED use or inpatient hospitalization, and ED use or inpatient hospitalization for ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSCs). Multilevel survival analyses were performed.

Results:

Children who received a maltreatment evaluation had an increased hazard for a subsequent ED visit or inpatient hospitalization (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.3, 95 % confidence interval [CI]: 1.1, 1.5) and a maltreatment-related visit (HR: 4.4, 95 % CI: 2.3, 8.2) relative to the general pediatric population. A maltreatment evaluation was not associated with a higher hazard of health care use for ACSCs (HR: 1.0, 95 % CI: 0.7, 1.3).

Conclusion:

This work can inform targeted anticipatory guidance to aid high-risk families in preventing future harm or minimizing complications from previous maltreatment.

Keywords: Child maltreatment, Health care utilization, Health services, Child protection, Pediatrics

1. Introduction

Child maltreatment is a major public health problem leading to significant pediatric morbidity and mortality (Vaithianathan et al., 2018). In 2020 alone, roughly 7.1 million children in the United States were subject of maltreatment reports and over one-third of maltreatment victims were younger than four years (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2022). Child maltreatment is associated with an elevated risk of common and high-cost pediatric illnesses, which result in a substantial health care burden in terms of both short- and long-term health care use (Peterson et al., 2018). Therefore, an understanding of health care use patterns of potential maltreated children may help prevent escalating or recurrent subsequent maltreatment and reduce inappropriate use of health care.

Children who have been previously maltreated are at high risk of developing diseases, illnesses, or conditions because of new maltreatment (Hindley et al., 2006) or complications from prior maltreatment (Huffhines & Jackson, 2019). These children are likely to experience recurrence of maltreatment (Hindley et al., 2006) and to receive acute health care service for injuries such as fractures and burns (Hunter & Bernstein, 2019; King et al., 2015) that may have resulted from an act related to maltreatment. They may also use acute health care due to increased chance of developing chronic health conditions that may be complicated by previous maltreatment, such as asthma, obesity, diabetes, and eczema (Huffhines & Jackson, 2019; Jackson et al., 2016; Jee et al., 2006; Lanier et al., 2010). This raises important concerns for health care providers in assessing pediatric health outcomes and risk of maltreatment recurrence for children who have a previous concern of maltreatment.

Consistent evidence has shown that compared to children in the general population, children who have experienced maltreatment are high utilizers of emergency department (ED) and inpatient hospitalization (Guenther et al., 2009; Kuang et al., 2018; O’Donnell et al., 2010). Several prevalence studies have estimated incidences of maltreatment-related ED visits or hospitalization among the general pediatric population (Hunter & Bernstein, 2019; King et al., 2015). However, prior studies focused primarily on patterns of health service use before children were diagnosed with maltreatment or involved in child protective service (CPS) systems (Kuang et al., 2018; O’Donnell et al., 2010). Few studies have examined children’s health care use or maltreatment-related medical encounters after they were identified as being at risk for maltreatment.

With such a high risk of acute health care use and development of undiagnosed or untreated chronic health conditions (e.g., Lanier et al., 2010), children at risk for maltreatment are likely to have preventable ED or hospital admissions (Szilagyi et al., 2015). Some of these chronic conditions (e.g., asthma) are considered to be ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSCs) for which an ED visit or hospital admission could be prevented by proper treatment in primary care (Burgdorf & Sundmacher, 2014). Hospitalization and ED visit for ACSCs could serve as an important indicator to quantify health care use disparities among children with previous concerns for maltreatment and children of the general population (Lichtl et al., 2017). Despite this, no research has focused on the prevalence of ACSCs in pediatric patients who have been evaluated for concerns of maltreatment.

Healthcare encounters are one of the only settings in which nearly all young children in the United States are regularly evaluated by a non-caregiver for health, growth, and development, which can provide potential opportunity to identify and prevent adverse pediatric health outcomes among children at risk of maltreatment. Given the high risk of maltreatment recurrence (Hindley et al., 2006), potential for ongoing health complications related to past maltreatment (Jonson-Reid et al., 2012), and improper use of acute health care for chronic conditions (Szilagyi et al., 2015), it is imperative to assess patterns of high-cost, intensive care use (e.g., ED and inpatient visits) among children with previous concerns of maltreatment. This could help facilitate our understanding of how healthcare systems could provide sentinel information about these children’s wellbeing over time and ameliorate negative health outcomes.

Evidence as to whether or not potential maltreatment is related to higher rates of subsequent health care use is limited. Moreover, pediatric studies that evaluated health care use of maltreated children have not comprehensively considered these health care use patterns together. Our study addresses this research gap to improve recommendations for care of this high-risk population and prevent escalating or recurrent maltreatment.

This study used information from the electronic health records (EHR) data for children from birth to three years old who were medically evaluated at a child abuse and neglect subspecialty clinic in a teaching and research hospital in the U.S. The aim of this study was to quantify the association of being evaluated for a concern of maltreatment with subsequent acute health care utilization. We assessed three health care utilization outcomes over 18 months after a child received an evaluation for maltreatment, including (1) ED use and inpatient hospitalization, (2) child maltreatment-related ED use and inpatient hospitalization, and (3) ED use and inpatient hospitalization for ACSCs.

2. Methods

2.1. Data source

Data came from electronic health records (EHR) spanning 3/1/2013 to 6/30/2019 from a large academic health system in the southeastern United States. This health system serves about 85 % of children in its primary catchment area. There are one tertiary care and two community-based hospitals, each with an ED. Healthcare is coordinated by utilizing a single EHR system that captures patients’ information from a network of primary care and specialty clinics. The university Institutional Review Board approved this study (Protocol #: Pro00100947).

2.2. Study population

This study used a retrospective cohort design comparing children who received maltreatment evaluation and the general pediatric population. Based on EHR data extracted from the health system, we constructed a cohort of children from birth to three years who (1) resided in a single county that serves as a primary catchment area for the health system, and (2) had either an evaluation for maltreatment at the child abuse and neglect subspecialty clinic or a well-child visit in the health system between 3/1/2013 and 12/1/2017. No other exclusion restrictions were applied.

We extracted EHR data for child demographic characteristics, county of residence, health insurance type, date a child was medically evaluated by a child abuse and neglect clinician (applicable to sample evaluated for a concern of maltreatment), date a child received a well-child visit (applicable to the general pediatric population), and date that a child had an ED visit or inpatient hospitalization. ED and inpatient visits were linked to diagnostic (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] or International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM]) and e-codes to assess whether these visits were related to maltreatment or ACSCs.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Independent variable

Our independent variable is whether or not a child received a medical evaluation for a concern of maltreatment. Hospitals and healthcare systems often utilize a specialty clinic to perform maltreatment evaluations, which is the gold standard for assessing levels of concern about whether or not a child has experienced maltreatment (Berger & Lindberg, 2019). The medical evaluations are usually completed by a board-certified child abuse pediatrician or experienced advanced practice provider and a social worker, and include medical and social histories, a thorough physical exam, and a diagnostic child interview for children older than three years. These evaluations result in a medical diagnosis that includes a level of concern for maltreatment including “no,” “unlikely,” “unknown,” “suspicious,” “probable,” and “clear and confirmed,” as well as recommendations for focal child’s health and safety.

A binary variable was developed indicating children from birth to three years who (1) were evaluated for a concern of maltreatment between 3/1/2013 and 12/1/2017 at the only child abuse and neglect medical evaluation subspecialty clinic in the health system (hereafter referred to as sample evaluated for a concern of maltreatment), or (2) had at least one well-child visit in the same health system and had not been medically evaluated for a concern of maltreatment at any time between 2014 and 2017 (hereafter referred to as the general pediatric population). We did not select the first well-child visit as an index visit to avoid an oversampling of infants. Instead, one well-child visit for each child within this time frame was randomly selected as their index visit. Data before 2014 for the general pediatric population are unavailable because the health system began using a single EHR system for all practices starting from 2014 (Hurst et al., 2021).

2.3.2. Dependent variables

2.3.2.1. Acute health service utilization.

Acute health service use was assessed by whether children had an ED visit or an overnight inpatient hospitalization 18 months following their index visit.

2.3.2.2. Child maltreatment-related health care utilization.

We also assessed ED visit or inpatient hospitalization possibly associated with maltreatment. To identify maltreatment-related diagnoses in our study, we applied a comprehensive list of ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes for explicit maltreatment (Supplemental Table 1) and ICD-9-CM codes suggestive of maltreatment (Supplemental Table 2) based on a previously published study (Hunter & Bernstein, 2019). Explicit maltreatment is under-documented in official health records (Hooft et al., 2015; Karatekin et al., 2018); therefore, studies have developed coding schemes using the codes to classify certain injuries or illnesses as suggestive of maltreatment (Lindberg et al., 2015; Schnitzer et al., 2011). Hunter and Bernstein’s (2019) study identified 62 ICD-9-CM and e-codes for suggestive maltreatment. These codes were built upon several key and seminal studies (Ben-Arieh & McDonell, 2009; King et al., 2015; Lindberg et al., 2015; Schnitzer et al., 2011). We excluded age-specific co-occurring codes (e.g., motor vehicle crash or unintentional fall) for different types of injuries to ensure that the diagnosis was associated with maltreatment rather than any other causes (Hunter & Bernstein, 2019). The presence of either a code for explicit maltreatment or suggestive maltreatment was considered to be child maltreatment-related health service use. We conducted a crosswalk from ICD-9-CM to ICD-10-CM codes to identify diagnoses related to child maltreatment using the corresponding codes for the general pediatric sample.

2.3.2.3. Ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSCs).

ED visit or inpatient hospitalization for ACSCs was defined based on Lichtl et al.’s (2017) study, which identified conditions that were used and validated in at least three out of seven previously conducted studies (Anderson et al., 2012; Becker et al., 2011; Casanova et al., 1996; Flores et al., 2005; Jaeger et al., 2015; Lu & Kuo, 2012; Prezotto et al., 2015). Lichtl et al.’s (2017) study added three more conditions (i.e., allergies & allergic reactions, gastritis, and neonatal jaundice) based on local pediatricians’ opinions. We decided to use this list given these ACSCs represent a consensus from previous studies and were studied in vulnerable pediatric populations (e.g., asylum-seeking children) (Brandenberger et al., 2020; Lichtl et al., 2017). Lichtl et al. (2017) identified 304 ICD-10-GM (German modification) codes that were classified into 17 condition categories including 1) allergies & allergic reactions, 2) asthma, 3) convulsions, 4) dental conditions, 5) diabetes mellitus, 6) failure to thrive, 7) gastritis, 8) gastroenteritis/dehydration, 9) immunization-preventable diseases, 10) inflammatory diseases of female pelvic organs, 11) iron deficiency anemia/anemia, 12) kidney- and urinary infections, 13) nutritional deficiency, 14) neonatal jaundice, 15) severe ENT & upper airway infection 16) skin infection, and 17) doctor’s orders have not been followed by patient. Using a framework from a prior study (Anderson et al., 2012), we assessed each of the 17 categories for inclusion to ensure relevance for a pediatric population. These considerations included (1) early access to primary care would prevent an ED visit for this condition and (2) the condition could be managed almost entirely in an ambulatory setting, assuming appropriate management (e.g., adherence to treatment). Based on this, we did not include ICD codes under the category “convulsions” given a high frequency of head trauma in our study population, which may be complicated by sequalae (e.g., subdural bleed) that lead to seizures and would require an ED visit. We created a crosswalk from ICD-10-GM to ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM codes for the 16 ACSCs. Our final identified ICD codes for this study are provided in Supplemental Table 3.

All dependent variables were assessed within 18 months following children’s index maltreatment evaluation visit (i.e., first visit in an episode from 2013 to 2017) or well-child visit (i.e., a randomly selected visit from 2014 to 2017). We then calculated the number of days between an index visit and the date that first outcome encounter occurred.

2.3.3. Covariates

A set of child demographic characteristics was selected for inclusion in multivariable analyses as covariates. These covariates included age (<one year of age, one year of age, two years of age, and three years of age [reference group]), sex at birth (female vs. male), and race (non-Hispanic White [reference group], non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and other or unknown). Health insurance was categorized by primary payor type as Medicaid and all other categories (i.e., private, other government, or others). To account for the role of socioeconomic status, we included the Area Deprivation Index (ADI) at state level in 2015, which is a ranking of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage. This index ranges from one to ten, with higher score indicating a higher level of disadvantage (Kind et al., 2014). We also controlled for the year of index visit (2013–2017).

2.4. Analytic strategy

Key characteristics of children were described using descriptive statistics including frequency, mean, standard deviation (SD), median, and interquartile range (IQR). We then conducted descriptive bivariate analyses (i.e., test of proportions, t-test, and Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon text) to compare health care use patterns and socio-demographic characteristics of children who were evaluated for a concern of maltreatment and the general pediatric population. For categorical variables, z-scores and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported for the differences of proportions between the two samples. The test of proportions is a type of z-test that assesses whether one population’s proportion statistically significantly differs from a second population’s proportion (Girdler-Brown & Dzikiti, 2018). For continuous variable, t-score and 95 % CI were reported for the differences of means between the two samples. To assess trends in time to all outcomes, we estimated Kaplan-Meier curves. Multilevel survival models were used to examine the associations between receipt of a child maltreatment evaluation and time to subsequent health care use, including first ED or inpatient visit, first maltreatment-related ED or inpatient visit, and first ED or inpatient visit for ACSCs, adjusting all pre-specified covariates. This method was chosen to account for the clustering of individual within neighborhoods. Time was defined as the number of days from an index visit to first date of an outcome, or until 18 months following an index visit (right-censored cases). We examined whether all outcome models met the proportional hazards assumptions. Findings were reported as adjusted hazard ratios (HRs), and 95 % CI. p-Values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. Stata 16.0 was used for data management and analyses (StataCorp, 2019).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive analysis

Our total sample included 21,598 children. Below we describe the sample evaluated for a concern of maltreatment and the general pediatric population, respectively.

3.1.1. Description of sample evaluated for a concern of maltreatment

Descriptive characteristics of children who were evaluated for a concern of maltreatment are shown in Table 1. This sample consisted of 367 children who were evaluated at the child abuse and neglect subspecialty clinic. Among this group, about one-third (n = 107) were under one year of age. The children were predominantly non-Hispanic Black (n = 213, 58.0 %) and nearly 80 % (n = 288) of this sample were covered by Medicaid. The median ADI score was 5 (IQR = 5.0). Notably, about 43.3 % (n = 159) of children had ED visits or inpatient hospitalizations in 18 months following an index evaluation and 3.3 % (n = 12) had visits related to maltreatment. Of the children who had a subsequent ED or inpatient visit, 7.6 % (12/159) of those visits were explicit for or suggestive of maltreatment. Around 15.3 % (n = 56) of children had visits for ACSCs.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of sample evaluated for a concern of maltreatment and general pediatric population (N = 21,598).

| Characteristics | Sample evaluated for maltreatment, n (%) (n = 367) | General pediatric population, n (%) (n = 21,231) | Test results | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Emergency department use/inpatient hospitalization | 159 (43.3) | 6415 (30.2) | 5.4 | 8.0, 18.2*** |

| Maltreatment-related emergency department use/ inpatient hospitalization | 12 (3.3) | 133 (0.6) | 6.2 | 0.8, 4.5*** |

| Emergency department use/inpatient hospitalization for ambulatory care sensitive conditions | 56 (15.3) | 2259 (10.6) | 2.8 | 0.9, 8.3** |

| Age at first encounter | ||||

| <1 year | 107 (29.2) | 10,015 (47.2) | −6.9 | −22.7, −13.3*** |

| 1 year | 76 (20.7) | 4527 (21.3) | −0.3 | −4.8, 3.6 |

| 2 years | 84 (22.9) | 2819 (13.3) | 5.4 | 5.3, 13.9*** |

| 3 years | 100 (27.3) | 3870 (18.2) | 4.4 | 4.4, 13.6*** |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 213 (58.0) | 7258 (34.2) | 9.5 | 18.8, 28.9*** |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 64 (17.4) | 6849 (32.3) | −6.0 | −18.8, −10.9*** |

| Hispanic | 59 (16.1) | 3586 (16.9) | −0.4 | −4.6, 3.0 |

| Other or unknown | 31 (8.5) | 2538 (16.7) | −4.2 | −11.1, −5.3*** |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 197 (53.7) | 10,406 (49.0) | 1.8 | −0.5, 9.8 |

| Male | 170 (46.3) | 10,825 (51.0) | −1.8 | −9.8, 0.5 |

| Health insurance status | ||||

| Medicaid | 288 (78.5) | 9788 (46.1) | 12.3 | 28.1, 36.6*** |

| All other types | 79 (21.5) | 11,443 (53.9) | −12.3 | −36.6, −28.1*** |

| Area Deprivation Index, mean (SD) | 5.3 (2.8) | 4.1 (2.6) | 8.0 | 0.9, 1.5*** |

| Area Deprivation Index, median (IQR) | 5.0 (5.0) | 3.0 (4.0) | 8.2 | 0.2, 0.3*** |

Note. SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; percentages of categorical variables were compared using test of proportions and the z-scores were reported; means of Area Deprivation Index were compared using t-test and the t-score was reported; medians of Area Deprivation Index were compared using Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test and the z-score was reported. Z-scores, t-scores, and 95 % confidence intervals were reported for the differences of proportions or means between the two samples.

Significant at the p-value < 0.01 level.

Significant at the p-value < 0.001 level.

3.1.2. Description of the general pediatric population

The general pediatric population who were not evaluated for a concern of maltreatment at the subspecialty clinic consists of 21,231 children (Table 1). Among this sample, almost 50 % (n = 10,015) were under one year old. The distribution of race/ethnicity was approximately equal between non-Hispanic White (n = 6849, 32.3 %) and non-Hispanic Black (n = 7258, 34.2 %), and slightly less than half of children were covered by Medicaid (n = 9788, 46.1 %). This group of children had a median ADI score of 3 (IQR = 4.0). Approximately 30.2 % (n = 6415) had a subsequent ED visit or inpatient hospitalization and 0.6 % (n = 133) had maltreatment-related ED visits or inpatient hospitalizations. Thus, 2.1 % (133/6415) of the ED or inpatient visits were explicit for or suggestive of maltreatment. About 10.6 % (n = 2259) of children presented for ED or inpatient care for ACSCs.

3.2. Bivariate analysis

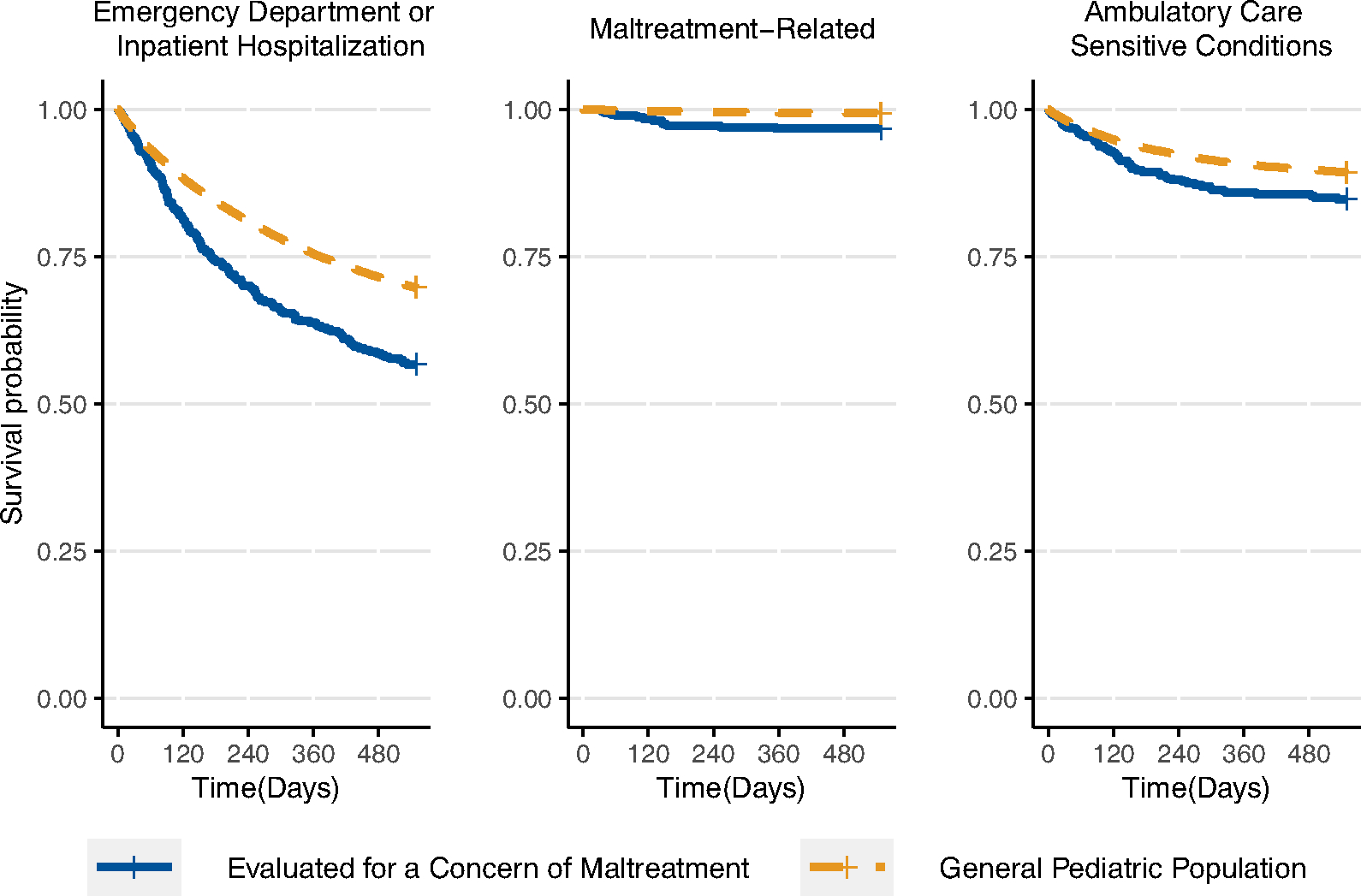

Table 1 shows results for bivariate comparisons between the sample evaluated for a concern of maltreatment and the general pediatric population. The tests of proportions indicated that compared to the general pediatric population, children evaluated for a concern of maltreatment were significantly more likely to have subsequent acute health care use, including ED visits or inpatient hospitalizations in general (43.3 % vs. 30.2 %, z = 5.4, 95 % CI [8.0, 18.2]), maltreatment-related ED visits or inpatient hospitalization (3.3 % vs. 0.6 %, z = 6.2, 95 % CI [0.8, 4.5]), and ED visits or inpatient hospitalization for ACSCs (15.3 % vs. 10.6 %, z = 2.8, 95 % CI [0.9, 8.3]) in 18 months following an index visit. Kaplan-Meier curves were demonstrated in Fig. 1, indicating that the probabilities of different acute health care use patterns were constantly higher among children who were evaluated for a concern of maltreatment as compared to the general pediatric population.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves describing acute health care use within 18 months after index encounter among children from birth to age three years.

Children evaluated for a concern of maltreatment were less likely to be younger than one year of age (29.2 % vs. 47.2 %, z = −6.9, 95 % CI [−22.7, −13.3]), and more likely to be non-Hispanic Black (58.0 % vs. 34.2 %, z = 9.5, 95 % CI [18.8, 28.9]), Medicaid-enrolled (78.5 % vs. 46.1 %, z = 12.3, 95 % CI [28.1, 36.6]), and live in more disadvantaged neighborhoods (mean of ADI = 5.3 vs. 4.1, t = 8.0, 95 % CI [0.9, 1.5]) than the general pediatric population.

3.3. Multivariable analysis

All of our multivariate models met the proportional hazards assumptions. Overall, models were significant for the associations between a receipt of maltreatment evaluation and an acute health care use (Wald χ2 = 2024.4, df = 14, p < 0.001), child maltreatment-related acute health care use (Wald χ2 = 125.9, df = 14, p < 0.001), and acute health care use for ACSCs (Wald χ2 = 1056.3, df = 14, p < 0.001). Results of the multivariable analysis (Table 2) indicated that after adjusting for child age, sex, race/ethnicity, health insurance status, and ADI, children who were evaluated for a concern of maltreatment had an increased hazard ratio for any type of subsequent ED visit or inpatient hospitalization (HR: 1.3, 95 % CI [1.1, 1.5]), and a subsequent maltreatment-related visit (HR: 4.4, 95 % CI [2.3, 8.2]) relative to the general pediatric population. However, receipt of an evaluation for maltreatment was not associated with higher hazard of a subsequent health care use for ACSCs (HR: 1.0, 95 % CI [0.7, 1.3]).

Table 2.

Cox regression results: Association between receipt of a maltreatment medical evaluation and time until acute health care use with 95 % confidence intervals (N = 21,598).

| Cox model | Any emergency department or inpatient visit |

Any maltreatment-related emergency department or inpatient visit |

Any emergency department or inpatient visit for ACSCs |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95 % CI | HR | 95 % CI | HR | 95 % CI | |

|

| ||||||

| Children received medical evaluation for a concern of maltreatment | 1.3 | 1.1, 1.5** | 4.4 | 2.3, 8.2*** | 1.0 | 0.7, 1.3 |

| Age at first encounter | ||||||

| <1 year | 2.1 | 1.9, 2.2*** | 1.7 | 1.0, 2.9 | 2.3 | 2.0, 2.6*** |

| 1 year | 1.6 | 1.5, 1.8*** | 1.7 | 0.9, 3.0 | 1.7 | 1.5, 2.0*** |

| 2 years | 1.2 | 1.1 1.4*** | 1.3 | 0.7, 2.5 | 1.3 | 1.1, 1.5** |

| 2 years (ref) | ||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White, Non-Hispanic (ref) | ||||||

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 1.9 | 1.8, 2.1*** | 2.1 | 1.2, 3.6*** | 2.9 | 2.5, 3.3*** |

| Hispanic | 1.7 | 1.6, 1.9*** | 0.9 | 0.5, 1.8 | 2.2 | 1.9, 2.6*** |

| Other or unknown | 1.1 | 1.0, 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.3, 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.1, 1.5** |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 0.9 | 0.8, 0.9*** | 0.9 | 0.7, 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.8, 0.9** |

| Male (ref) | ||||||

| Health insurance status | ||||||

| Medicaid | 1.8 | 17 1 9*** | 2.9 | 1.8, 4.5*** | 2.2 | 1.9 2.4*** |

| All other types (ref) | ||||||

| Area Deprivation Index | 1.1 | 111 1*** | 1.0 | 1.0, 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0, 1.1*** |

| Model fit | Wald χ2 = 2024.4, df = 14, p < 0.001 | Wald χ2 = 125.9, df = 14, p < 0.001 | Wald χ2 = 1056.3, df = 14, p < 0.001 | |||

Note. ACSC, ambulatory care sensitive condition; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ref., reference group for categorical variables; df, degree of freedom. Controlling for year of index child maltreatment visit.

Significant at the p-value < 0.01 level.

Significant at the p-value < 0.001 level.

4. Discussion

Our study aimed to assess whether a child maltreatment evaluation was associated with a higher risk of subsequent health care use over an 18-month period. Our findings revealed that, compared to the general pediatric population who were not evaluated for maltreatment, receiving a medical evaluation for a concern of maltreatment was significantly associated with higher hazards of subsequent ED visits or inpatient hospitalizations and maltreatment-related visits. The observed associations could not be explained by differences in age, sex, race/ethnicity, or health insurance status.

The occurrence of an ED visit or inpatient hospitalization for children who were evaluated for a concern of maltreatment was descriptively higher than that in the general pediatric population in our study, as well as previous estimates for general pediatric samples (34 %–38 %; Lee & Monuteaux, 2019; McDermott et al., 2018). The risk was still 1.3 times higher even after accounting for race/ethnicity, Medicaid enrollment, and neighborhood level disadvantage – salient factors affecting health care use (Hong et al., 2007; Kirby & Kaneda, 2005; Riera & Walker, 2010). We found that children who were evaluated for a concern of maltreatment were approximately four times more likely than the general pediatric population to use the ED or receive inpatient care for maltreatment or for injuries, illnesses, or conditions potentially associated with maltreatment. The proportions of maltreatment-related visits in all ED or inpatient visits for the evaluated children and the general pediatric population (7.6 % vs 2.1 %) were similar to proportions found in prior studies (Hunter & Bernstein, 2019; King et al., 2015). This substantial difference suggests that even after services and referrals were provided, children evaluated for a concern of maltreatment were still at a higher risk of experiencing future harm or complications from maltreatment evaluated at the index visit. To contextualize our results, we further examined the CPS records of our sample. Among the 367 children who had a maltreatment evaluation, 131 (35.7 %) were reported to CPS within 18 months after the evaluation and 11.7 % (n = 43) of the evaluated children had a substantiated report (i.e., reports with serious safety issues for children and/or criminal charges against perpetrator, or reports that need services), which was much higher than the rates for general pediatric sample (0.7 % [n = 151] of the children had a substantiated report). Together, our findings highlight the high risk of being a victim of maltreatment or experiencing maltreatment recurrence among the evaluated children.

It should be noted that clinicians in the subspecialty clinic typically recommend services rather than directly place orders for services following a maltreatment evaluation (Golonka et al., 2022). Thus, the effectiveness of the services is largely determined by whether the caregivers can and do follow the recommendations and the quality of services provided. Many families experiencing trauma report a range of barriers to receiving treatment such as lack of knowledge or resources associated with services, stigma, financial barriers, and time constraints (Kantor et al., 2017). Such barriers have been reported by families of children who experienced maltreatment, which led to a low adherence to treatment plans or service orders (Staudt, 2003) and limited benefits they could receive. Moreover, caregivers and children may have negative experiences if the services are not delivered as they expected (Hardy & Darlington, 2008), preventing them from participating in any further services. As limited research has examined the effectiveness of follow-up service utilization for children evaluated for maltreatment, research is needed to examine families’ adherence to service recommendations, ways to minimize the barriers to accessing services, and outcomes of the services delivered.

Whether young children use acute health care services for potentially maltreatment-related conditions following a maltreatment evaluation is subject to both medical providers’ and caregivers’ actions. A child’s history of maltreatment evaluation with repeated injuries could raise suspicion of primary care providers about a maltreatment recurrence and affect their following actions including a referral to ED or a report to CPS. As mandatory reporters of child maltreatment, primary care providers experience challenges to make decisive conclusions on maltreatment partially due to lack of evidence to support a maltreatment claim (Kuruppu et al., 2020). Thus, they may refer the child to be further evaluated by pediatric specialists in ED or hospital-based child abuse medical experts (Flaherty et al., 2008; Kuruppu et al., 2020). Similarly, caregivers of children who were evaluated for maltreatment or with a history of maltreatment may be more vigilant about any injuries or illnesses that could result from abuse or neglect, and thus use more health care for further assessments. However, a maltreatment evaluation or a mandatory report to CPS by health care providers risk alienating families’ trust in the healthcare system (Flaherty et al., 2006; McTavish et al., 2017). Families may disengage from such systems if they suspect coercive power (Fong, 2020), leading to less use of health care services. While our findings indicate a higher likelihood of acute health care use among children who were evaluated for maltreatment, future work using qualitative methods could help disentangle such nuances in medical providers’ decision-making process and caregivers’ healthcare-seeking behaviors by considering their perspectives on health care use after a maltreatment evaluation.

Children who were evaluated for a concern of maltreatment had a higher rate of visiting an ED or inpatient care for ACSCs than the general pediatric population. Yet when we controlled for socio-demographic characteristics that might confound this association in multivariate analyses, an evaluation for maltreatment was not associated with a higher probability of health care visits for ACSCs relative to the general pediatric population. Despite this, our study reified several previously identified demographic and socioeconomic factors that were potentially associated with preventable ED use or hospitalization (Bettenhausen et al., 2017; Kangovi et al., 2013). As previous studies have shown, children at risk for maltreatment are more likely to reside in areas with high levels of poverty and social, political, and economic disenfranchisement, and where systemic resources to support parents and families are limited (Kim & Drake, 2018). Such living environment and socioeconomic status (SES) may lead to elevated risk for hospitalizations for ACSCs (Bettenhausen et al., 2017; Kangovi et al., 2013; Wallar et al., 2020) because children from low SES families are more likely to be injured than those from high SES backgrounds and use acute health services as their primary source of medical care than ambulatory care.

Although the nonsignificant association between a maltreatment evaluation and increased use of ED or inpatient care for ACSCs was unexpected, it reflects a more important role of non-dominant racial/ethnic groups, Medicaid enrollment, and low SES in driving a high rate of accessing acute health care for ACSCs. This is possibly caused by poor parental health literacy (Sanders et al., 2009), restricted access to transportation, limited availability of primary care in this population, or perceptions that hospitals offer better access, health care quality, and technical competence (Kangovi et al., 2013). Due to limited studies in this area, future pediatric research should explore measurements of ACSCs and better understand its relationship with children’s use of health care and potential complex relationships with SES and race/ethnicity.

This study indicates that it is important to characterize health care utilization by the nature of services, which allows for targeted interventions for children with various utilization patterns. In addition to maltreatment-related health encounters and ACSCs, there were still a large proportion of children who experienced maltreatment or had a concern for maltreatment presented to ED or inpatient care with other complaints or diagnoses, though not necessarily ACSCs. We did not assess chief complaint or diagnosis that could provide an explanation for the high rate of utilization. Previous literature is limited regarding diagnostic differences between maltreated and general pediatric patients. Some studies suggested that although compared to population-based control subjects, children with confirmed child abuse had almost twice risk of ED visits before their visits for maltreatment symptoms, these two groups were similar in symptoms presented in ED visits (Bailhache et al., 2022; Guenther et al., 2009). Since child maltreatment is associated with a variety of negative behavioral, emotional, and health outcomes leading to ED or hospitalization (Jonson-Reid et al., 2012), our study reinforces a need for investigating other potential reasons or utilization patterns that may lead to the high rate of acute health care use among high-risk cohorts.

4.1. Limitations

There were several limitations with our study. Our data were from one academic medical system and, therefore, our findings may not be more broadly representative. While sufficient for addressing our objectives, the relatively small sample of children who were evaluated for a concern of maltreatment prevented us from exploring specific types of maltreatment. Second, ICD codes for maltreatment are often under-utilized in medical records (Scott et al., 2009). This could potentially result in an underestimation of maltreatment-related health care use. We used an algorithm to identify suspected maltreatment in the EHR to help more accurately quantify this public health problem. Third, due to limited information on household socioeconomic characteristics, we used two proxy measures: the neighborhood-level ADI which combines information on education, employment, income, and housing quality (Kind et al., 2014) and individual-level health insurance status (Medicaid vs. other). As most young children who are enrolled on Medicaid are eligible due to their household’s low-income status, Medicaid coverage is considered an indicator of low SES (Foraker et al., 2010; Nattinger et al., 2021). Future work including individual-level and household-level socioeconomic status could improve our understanding of how these factors differentially affect health care utilization. Finally, data on index dates for children evaluated for a concern of maltreatment and the general pediatric population were not matched. However, we did choose dates of services during an overlapping set of years to prevent immortal time bias (Lévesque et al., 2010). Data were unobservable for children who left our sample due to competing risk events (Satagopan et al., 2004), such as dying, moving out of the county, or other causes. We assume that death is relatively rare and unlikely to have substantially affected results. Residential moves to other counties could result in children seeking health care from other systems, which our study could not observe. However, given that low-income children are more likely to experience a residential move than higher income children (Coulton et al., 2012; Lichter et al., 2022; Mollborn et al., 2018) and that lower-income children are disproportionately represented in the group evaluated for maltreatment, bias resulting from this confounder likely implies that our estimated between group differences are conservative.

4.2. Implications for practice

Our study has clinical and research implications regarding early prevention and ambulatory care use for children who have been evaluated for a concern of maltreatment. Our findings highlight that these children had a higher risk of acute health service use, both for maltreatment-related injuries or illnesses and conditions more broadly, even after potential maltreatment has been diagnosed, involvement with child welfare when mandated, and when other referrals and supports were offered. Characterizing health care utilization by patterns of service use would allow for targeted preventative measures and anticipatory guidance to help families and children with different medical needs seek care from appropriate general or subspecialty pediatricians. Clinicians in the child abuse and neglect subspecialty clinic could provide appropriate health service recommendations to high-risk children and families, and work with community partners to ensure children’s adherence to the recommended or placed services. Clinicians could ensure children who have been evaluated for a concern of maltreatment have access to routine care with a trusted health care provider. This provider can continue to monitor children’s health and proactively provide advice and guidance should there be complications of existing conditions. Furthermore, to minimize risks of escalating or repeated maltreatment, health care providers in hospitals and EDs should be aware of children’s maltreatment history and target children who have maltreatment-related diagnoses as a high-risk group to prevent ongoing or further victimization. Given that many children who have been evaluated for a concern of maltreatment used health services not specific to maltreatment, clinicians should also pay attention to other health needs separate from concerns of immediate harm.

To avoid potentially preventable ED or hospital utilization, reduce cost of care, and improve patient experience, access to appropriate ambulatory care should be improved for non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients, and low-SES patients. It should be noted that very few studies have assessed ACSCs for children who have possibly experienced maltreatment, and this issue needs to be investigated further in other samples (e.g., children involved in CPS). Relative to the general pediatric population, children with suspected maltreatment have more chronic illnesses and higher medical complexity (Azzopardi et al., 2021), and therefore may have unique reasons to make health care use decisions. To identify potentially modifiable factors and develop appropriate interventions, more in-depth studies are needed on parent perspectives about the reasons that drive their use of ambulatory care for children at risk of maltreatment.

5. Conclusion

This study examined the association between receiving a maltreatment evaluation and risk of subsequent health care use among children from birth to age three. Specifically, we found that a receipt of maltreatment evaluation was associated with higher risk for a subsequent ED visit or inpatient hospitalization, and a maltreatment-related visit. Hospitals and EDs should pay attention to complications of maltreatment, maltreatment history, and health needs of high-risk children. Child abuse and neglect clinicians could utilize these patterns of health care use to identify concerning trends and help high-risk families minimize complications resulting from potential previous maltreatment or prevent future harm.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by the Duke Endowment, ABC Thrive Bass Connections, and the Translating Duke Health Children’s Health and Discovery Initiative.

Role of funder/sponsor

None of the funders had any role in the design or conduct of this study. The state Division of Social Services and/or the Human Services Business Information & Analytics Office does not take responsibility for the scientific validity or accuracy of methodology, results, statistical analyses, or conclusions presented.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105938.

Data availability

The data that has been used is confidential.

References

- Anderson P, Craig E, Jackson G, & Jackson C (2012). Developing a tool to monitor potentially avoidable and ambulatory care sensitive hospitalisations in New Zealand children. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 125(1366), 25–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzopardi C, Cohen E, Pépin K, Netten K, Birken C, & Madigan S (2021). Child welfare system involvement among children with medical complexity. Child Maltreatment, 27(2), 257–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailhache M, Lafagne A, Lagarde M, & Richer O (2022). Do victims of abusive head trauma visit emergency departments more often than children hospitalized for fever? A case-control study. Pediatric Emergency Care, 38(1), e310–e315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker DJ, Blackburn JL, Kilgore ML, Morrisey MA, Sen B, Caldwell C, & Menachemi N (2011). Continuity of insurance coverage and ambulatory care–sensitive hospitalizations/ED visits: Evidence from the Children’s health insurance program. Clinical Pediatrics, 50(10), 963–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Arieh A, & McDonell J (2009). Child safety measure as a proxy for child maltreatment: Preliminary evidence for the potential and validity of using ICD-9 coded hospital discharge data at the community level. Children and Youth Services Review, 31(8), 873–878. [Google Scholar]

- Berger RP, & Lindberg DM (2019). Early recognition of physical abuse: Bridging the gap between knowledge and practice. The Journal of Pediatrics, 204, 16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettenhausen JL, Colvin JD, Berry JG, Puls HT, Markham JL, Plencner LM, & Walker JM (2017). Association of income inequality with pediatric hospitalizations for ambulatory care–sensitive conditions. JAMA Pediatrics, 171(6). e170322–e170322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandenberger J, Bozorgmehr K, Vogt F, Tylleskär T, & Ritz N (2020). Preventable admissions and emergency-department-visits in pediatric asylum-seeking and non-asylum-seeking patients. International Journal for Equity in Health, 19(1), 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorf F, & Sundmacher L (2014). Potentially avoidable hospital admissions in Germany: An analysis of factors influencing rates of ambulatory care sensitive hospitalizations. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 11 1(13), 215–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova C, Colomer C, & Starfield B (1996). Pediatric hospitalization due to ambulatory care-sensitive conditions in Valencia (Spain). International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 8(1), 51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulton C, Theodos B, & Turner MA (2012). Residential mobility and neighborhood change: Real neighborhoods under the microscope. Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research, 14(3), 55–89. [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty EG, Sege RD, Griffith J, Price LL, Wasserman R, Slora E, Dhepyasuwan N, Harris D, Norton D, Angelili ML, Abney D, & Binns HJ (2008). From suspicion of physical child abuse to reporting: Primary care clinician decision-making. Pediatrics, 122(3), 611–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty EG, Sege R, Price LL, Christoffel KK, Norton DP, & O’Connor KG (2006). Pediatrician characteristics associated with child abuse identification and reporting: Results from a national survey of pediatricians. Child Maltreatment, 11(4), 361–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores G, Abreu M, Tomany-Korman S, & Meurer J (2005). Keeping children with asthma out of hospitals: parents’ and physicians’ perspectives on how pediatric asthma hospitalizations can be prevented. Pediatrics, 116(4), 957–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong K (2020). Getting eyes in the home: Child protective services investigations and state surveillance of family life. American Sociological Review, 85(4), 610–638. [Google Scholar]

- Foraker RE, Rose KM, Whitsel EA, Suchindran CM, Wood JL, & Rosamond WD (2010). Neighborhood socioeconomic status, medicaid coverage and medical management of myocardial infarction: Atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) community surveillance. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girdler-Brown BV, & Dzikiti LN (2018). Hypothesis tests for the difference between two population proportions using stata. Southern African Journal of Public Health, 2(3), 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Guenther E, Knight S, Olson LM, Dean JM, & Keenan HT (2009). Prediction of child abuse risk from emergency department use. The Journal of Pediatrics, 154(2), 272–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy F, & Darlington Y (2008). What parents value from formal support services in the context of identified child abuse. Child & Family Social Work, 13(3), 252–261. [Google Scholar]

- Hindley N, Ramchandani PG, & Jones DP (2006). Risk factors for recurrence of maltreatment: A systematic review. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 91(9), 744–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong R, Baumann BM, & Boudreaux ED (2007). The emergency department for routine healthcare: Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and perceptual factors. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 32(2), 149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooft AM, Asnes AG, Livingston N, Deutsch S, Cahill L, Wood JN, & Leventhal JM (2015). The accuracy of ICD codes: Identifying physical abuse in 4 children’s hospitals. Academic Pediatrics, 15(4), 444–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffhines L, & Jackson Y (2019). Child maltreatment, chronic pain, and other chronic health conditions in youth in foster care. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 12(4), 437–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter AA, & Bernstein B (2019). Identification of child maltreatment-related emergency department visits in Connecticut, 2011 to 2014. Clinical Pediatrics, 58(9), 970–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst JH, Liu Y, Maxson PJ, Permar SR, Boulware LE, & Goldstein BA (2021). Development of an electronic health records datamart to support clinical and population health research. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, 5(e13), 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson Y, Cushing CC, Gabrielli J, Fleming K, O’Connor BM, & Huffhines L (2016). Child maltreatment, trauma, and physical health outcomes: The role of abuse type and placement moves on health conditions and service use for youth in foster care. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 41(1), 28–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger MW, Ambadwar PB, King AJ, Onukwube JI, & Robbins JM (2015). Emergency care of children with ambulatory care sensitive conditions in the United States. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 49(5), 729–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jee SH, Barth RP, Szilagyi MA, Szilagyi PG, Aida M, & Davis MM (2006). Factors associated with chronic conditions among children in foster care. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 17(2), 328–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonson-Reid M, Kohl PL, & Drake B (2012). Child and adult outcomes of chronic child maltreatment. Pediatrics, 129(5), 839–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangovi S, Barg FK, Carter T, Long JA, Shannon R, & Grande D (2013). Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Affairs, 32(7), 1196–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor V, Knefel M, & Lueger-Schuster B (2017). Perceived barriers and facilitators of mental health service utilization in adult trauma survivors: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 52, 52–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karatekin C, Almy B, Mason SM, Borowsky I, & Barnes A (2018). Health-care utilization patterns of maltreated youth. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 43(6), 654–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby JB, & Kaneda T (2005). Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and access to health care. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46(1), 15–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, & Drake B (2018). Child maltreatment risk as a function of poverty and race/ethnicity in the USA. International Journal of Epidemiology, 47(3), 780–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kind AJ, Jencks S, Brock J, Yu M, Bartels C, Ehlenbach W, & Smith M (2014). Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and 30-day rehospitalization: A retrospective cohort study. Annals of Internal Medicine, 161(11), 765–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AJ, Farst KJ, Jaeger MW, Onukwube JI, & Robbins JM (2015). Maltreatment-related emergency department visits among children 0 to 3 years old in the United States. Child Maltreatment, 20(3), 151–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang X, Aratani Y, & Li G (2018). Association between emergency department utilization and the risk of child maltreatment in young children. Injury Epidemiology, 5(1), 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuruppu J, McKibbin G, Humphreys C, & Hegarty K (2020). Tipping the scales: Factors influencing the decision to report child maltreatment in primary care. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(3), 427–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier P, Jonson-Reid M, Stahlschmidt MJ, Drake B, & Constantino J (2010). Child maltreatment and pediatric health outcomes: A longitudinal study of low-income children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 35(5), 511–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, & Monuteaux MC (2019). Trends in pediatric emergency department use after the affordable care act. Pediatrics, 143(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lévesque LE, Hanley JA, Kezouh A, & Suissa S (2010). Problem of immortal time bias in cohort studies: Example using statins for preventing progression of diabetes. BMJ, 340, Article b5087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtl C, Lutz T, Szecsenyi J, & Bozorgmehr K (2017). Differences in the prevalence of hospitalizations and utilization of emergency outpatient services for ambulatory care sensitive conditions between asylum-seeking children and children of the general population: A cross-sectional medical records study (2015). BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Parisi D, & Taquino MC (2022). Inter-county migration and the spatial concentration of poverty: Comparing metro and nonmetro patterns. Rural Sociology, 87(1), 119–143. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg DM, Beaty B, Juarez-Colunga E, Wood JN, & Runyan DK (2015). Testing for abuse in children with sentinel injuries. Pediatrics, 136(5), 831–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S, & Kuo DZ (2012). Hospital charges of potentially preventable pediatric hospitalizations. Academic Pediatrics, 12(5), 436–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golonka M, Liu Y, Rohrs R, Copeland J, Byrd J, Stilwell L, … Gifford EJ (2022). What do child abuse and neglect medical evaluation consultation notes tell researchers and clinicians? Child Maltreatment. 10.1177/10775595221134537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott KW, Stocks C, & Freeman WJ (2018). Overview of pediatric emergency department visits, 2015: Statistical Brief# 242. Retrieved July 28, 2021, from https://europepmc.org/article/NBK/nbk526418. [Google Scholar]

- McTavish JR, Kimber M, Devries K, Colombini M, MacGregor JC, Wathen CN MacMillan HL., … (2017). Mandated reporters’ experiences with reporting child maltreatment: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ Open, 7(10), Article e013942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollborn S, Lawrence E, & Root ED (2018). Residential mobility across early childhood and children’s kindergarten readiness. Demography, 55(2), 485–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattinger AB, Rademacher N, McGinley EL, Bickell NA, & Pezzin LE (2021). Can regionalization of care reduce socioeconomic disparities in breast cancer survival? Medical Care, 59(1), 77–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell M, Nassar N, Leonard H, Jacoby P, Mathews R, Patterson Y, & Stanley F (2010). Rates and types of hospitalisations for children who have subsequent contact with the child protection system: A population based case-control study. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 64(9), 784–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, Florence C, & Klevens J (2018). The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States, 2015. Child Abuse & Neglect, 86, 178–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prezotto KH, Chaves MMN, & Mathias TADF (2015). Hospital admissions due to ambulatory care sensitive conditions among children by age group and health region. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP, 49, 44–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riera A, & Walker DM (2010). The impact of race and ethnicity on care in the pediatric emergency department. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 22(3), 284–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders LM, Shaw JS, Guez G, Baur C, & Rudd R (2009). Health literacy and child health promotion: Implications for research, clinical care, and public policy. Pediatrics, 124(Supplement 3), S306–S314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satagopan J, Ben-Porat L, Berwick M, Robson M, Kutler D, & Auerbach A (2004). A note on competing risks in survival data analysis. British Journal of Cancer, 91(7), 1229–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzer PG, Slusher PL, Kruse RL, & Tarleton MM (2011). Identification of ICD codes suggestive of child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 35(1), 3–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott D, Tonmyr L, Fraser J, Walker S, & McKenzie K (2009). The utility and challenges of using ICD codes in child maltreatment research: A review of existing literature. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(11), 791–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2019). Stata statistical software (release 16). College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. https://www.stata.com. [Google Scholar]

- Staudt MM (2003). Mental health services utilization by maltreated children: Research findings and recommendations. Child Maltreatment, 8(3), 195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szilagyi MA, Rosen DS, Rubin D, & Zlotnik S (2015). Health care issues for children and adolescents in foster care and kinship care. Pediatrics, 136(4), e1142–e1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health& Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. (2022). Child Maltreatment 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2022, from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment. [Google Scholar]

- Vaithianathan R, Rouland B, & Putnam-Hornstein E (2018). Injury and mortality among children identified as at high risk of maltreatment. Pediatrics, 141(2), Article e20172882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallar LE, De Prophetis E, & Rosella LC (2020). Socioeconomic inequalities in hospitalizations for chronic ambulatory care sensitive conditions: A systematic review of peer-reviewed literature, 1990–2018. International Journal for Equity in Health, 19(1), 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that has been used is confidential.