Abstract

Stag beetles (Coleoptera: Lucanidae) represent a significant saproxylic assemblage in forest ecosystems and are noted for their enlarged mandibles and male polymorphism. Despite their relevance as ideal models for the study of exaggerated mandibles that aid in attracting mates, the regulatory mechanisms associated with these traits remain understudied, and restricted by the lack of high-quality reference genomes for stag beetles. To address this limitation, we successfully assembled the first chromosome-level genome of a representative species Dorcus hopei. The genome was 496.58 Mb in length, with a scaffold N50 size of 54.61 Mb, BUSCO values of 99.8%, and 96.8% of scaffolds anchored to nine pairs of chromosomes. We identified 285.27 Mb (57.45%) of repeat sequences and annotated 11,231 protein-coding genes. This genome will be a valuable resource for further understanding the evolution and ecology of stag beetles, and provides a basis for studying the mechanisms of exaggerated mandibles through comparative analysis.

Subject terms: Genome, Entomology

Background & Summary

Stag beetles (Family: Lucanidae), comprise over 1,800 species and subspecies1, noted for enlarged allometry mandibles and male polymorphism2. As a holometabolous insect, they undergo a complete metamorphosis with four life stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult3,4. The larvae primarily feed on decaying wood, while the adults are mostly nocturnal and feed on plant juices, fruits, or other decaying organic matter5–7. Due to their saprophagous nature, stag beetles play essential roles in the carbon and nitrogen cycles, which also makes stag beetles an important indicator species for evaluating forest ecosystems1,8,9. Based on observations of male lucanid beetles, Darwin (1871)10 noted that “The great mandibles of the male Lucanidae are extremely variable both in size and structure…and are used as efficient weapons for fighting”. It implies that individuals with larger mandibles have a better chance of defeating their rivals and winning mating rights11,12. Due to its unique and variable appearances, as well as interesting behavioral phenomena, this group has garnered the affection of many collectors, entomologists and evolutionary biologists8,10.

Stag beetles are widely distributed across various biogeographic regions and represent a group with significant nodal importance in the process of evolution13. The research on the Lucanidae family is predominantly concentrated on molecular taxonomic studies8,14,15, based on the data from nuclear gene fragments16, mitochondrial multi-gene fragments17 and mitochondrial genomes18,19. However, these data are insufficient to provide more insights into the formation and differentiation of the stag beetles’ mandibles20. Decoding high-quality reference genomes has been proven to be the cornerstone of inferring phylogeny and exploring the molecular basis behind phenotypic innovation21, e.g., the antlers of cervids22, the long tail feathers of birds23,24, and the horns of some scarabs25,26. The limited availability of genomic data hindered our research on Lucanidae family.

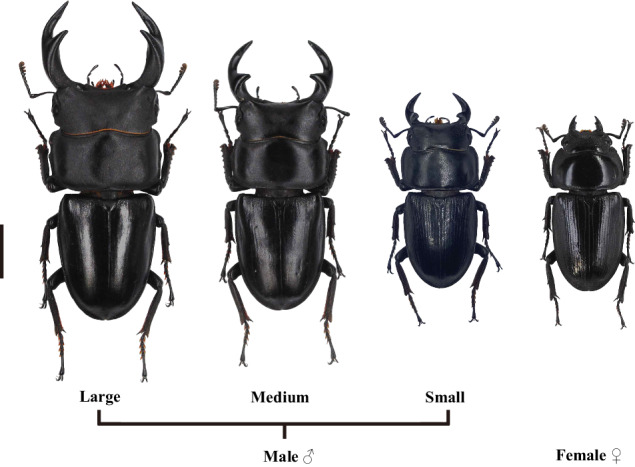

Dorcus hopei (Saunders, 1854), distributing from central and northeastern China, is a well-known species notable for its sword-shaped mandibles2,27,28 (Fig. 1). Comparatively, its mandibles are simpler to observe, with a large sharp bump and a relatively small inner tooth. Owing to the restriction of insect allometry and scaling relationship29–31, its male trimorphism in mandibles and body sizes is a very rare type. Based on these characteristics, D. hopei is a good choice for performing long-term studies in stag beetles.

Fig. 1.

Sexual dimorphism and male trimorphism in Dorcus hopei. The scale bar is 1 cm.

In this study, we successfully assembled the first chromosome-level reference genome of D. hopei using Illumina, Nanopore and Hi-C sequencing, the information from which could enhance our understanding of stag beetle survival and evolution. Furthermore, it provides a novel clue for uncovering the molecular basis of extreme mandibles development and male trimorphism formation in the future.

Methods

Sample information

Adult male D. hopei specimens were collected from Shou County, Huainan City, Anhui Province, China, during May and June from 2017 to 2021. The beetles were subsequently reared in the laboratory (23 °C, 14 h:10 h light/dark cycle, and 45% relative humidity) and provided with brown sugar jelly and bananas as food. Two adult males were selected for next-generation genomic sequencing using the Illumina platform, one adult male was used for long-read genomic sequencing with the Oxford Nanopore platform, two adult males were selected for Hi-C sequencing, and one adult male was used for transcriptomic sequencing.

Illumina, nanopore, Hi-C, and RNA sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from the leg muscles using a Trelief Animal Genomic DNA Kit (TsingKe, China). Paired-end libraries (insert size: 350 bp) were generated using a NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit (New England Biolabs, USA) with the Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform at Novogene (Tianjin, China). After filtering the bases in the raw reads of quality <Q20, we obtained 55.13 Gb (113x) clean Illumina data.

For Oxford Nanopore long-read sequencing, DNA from thorax muscles were extracted using a Qiagen DNAeasy Kit (Qiagen, German). Subsequently, the extracted DNA was treated with the NEBNext Ultra End Repair/dA-Tailing module (New England Biolabs, USA) to incorporate adapters for priming sequencing reactions (NextOmics, China). The library was constructed using a 1D DNA Ligation Sequencing Kit (SQK-LSK109) (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, England) and sequencing was performed on a PromethION flow cell (NextOmics, China) to obtain 46.34 Gb (95x) Nanopore data.

For Hi-C sequencing, cells isolated from head tissues were fixed with formaldehyde and subsequently digested using the restriction enzyme MboI. The DNA was purified and then sheared into 300–600 bp fragments using a Covaris M220 device (Covaris, USA). After DNA size selection using AMPure XP beads, point ligation junctions were pulled down using Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin C1 (ThermoFisher, USA). Then the Hi-C library was sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq sequencing platform at Novogene (China), and we got 48.46 Gb (100x) Hi-C data.

Transcriptomic sequencing was used to assist in gene structure annotation. RNA was extracted from the head tissue of one adult male using TRIzol. RNA quality was assessed using an RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit for 2100 Bioanalyzer Systems Kit (Agilent Technologies, China). The libraries were generated using a NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit (New England Biolabs, USA) and sequenced on the Illumina Hiseq platform at Novogene (Tianjin, China). And 8.07 Gb were obtained for assisting genomic annotation.

Chromosome-level genome assembly

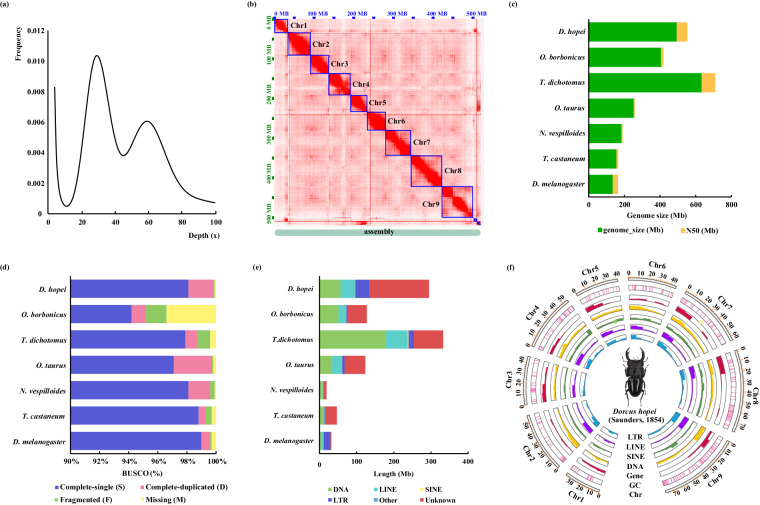

Illumina data was used to estimate genome size based on 17 k-mer size analysis using KmerFreq v5.032. The estimated genome size of D. hopei was 487.15 Mb, with heterozygosity of 0.021 based on the frequency distribution of 17-mers (Fig. 2a). The Oxford Nanopore long reads were used to assemble and polish the primary genome with NextDenovo v2.5.0 (https://github.com/Nextomics/NextDenovo) (parameters: -k 0 -p 15) and purge_dups v1.0.033. The Illumina short reads were used to correct errors at the base level in the above-polished genome using NextPolish v1.4.034. The Nanopore assembly was 496.47 Mb (N50 = 3.94 Mb), comprised 232 contigs, and achieved a BUSCO completeness score of 99.90% (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Assembly of chromosome-level genome of Dorcus hopei. (a) 17-mer analysis of the D. hopei genome based on Illumina reads, X-axis represented depth (x); Y-axis represented the proportion of the frequency of that depth to the total frequency of all depths. (b) Heatmap of Hi-C data showing nine chromosome boundaries (Chr1 to Chr9). The comparison of (c) genome size and N50 length, (d) BUSCO scores, and (e) repeat elements in D. hopei and six other species. (f) Circos tracks showing chromosome length, GC content, density of protein-coding genes, and repetitive elements (SINE, short interspersed elements; LINE, long interspersed elements; LTR, long terminal repeat elements).

Table 1.

Statistics for Dorcus hopei genome assembly and gene annotation.

| Statistics | Nanopore assembly | Hi-C assembly |

|---|---|---|

| Assembly | ||

| Total number | 232 | 27 |

| Genome size (Mb) | 496.47 | 496.58 |

| Average length (Mb) | 2.14 | 18.39 |

| N50 length (Mb) | 3.94 | 54.61 |

| N90 length (Mb) | 1.01 | 33.12 |

| Maximum length (Mb) | 17.85 | 75.00 |

| GC content (%) | 35.23 | 35.22 |

| BUSCO (completeness, %) | 99.9 | 99.8 |

| Anchor rate (%) | — | 96.18 |

| Illumina reads mapping rate (properly paired) (%) | 99.10 (94.20) | 99.10 (94.20) |

| Nanopore reads mapping rate (%) | 88.81 | 100.00 |

| Annotation | ||

| Gene number | 11,231 | |

| Average gene length (bp) | 15,840.00 | |

| Average CDSa length (bp) | 1,714.51 | |

| Average exon number | 6.58 | |

| Average exon length (bp) | 260.59 | |

| Average intron length (bp) | 2,531.69 | |

| BUSCO (%) | 92.0 | |

aCDS: coding sequence.

The Hi-C paired-end reads were iteratively mapped to the Nanopore assembly using HiC-Pro v2.9.035. The paired tags were then filtered using restriction enzyme digesting fragments with Juicer v1.60 and contigs were ordered and orientated using 3D de novo assembly software (3D-DNA) v18092236. Finally, JuiceBox v1.11.0837 was applied to correct contig orientation and move suspicious fragments into unanchored groups by visual exploration of the Hi-C heatmap. After Hi-C assembly, the resulting 496.58 Mb genome was assembled into 18 chromosomes (2n = 8AA + XY) (Table 1; Fig. 2b). Notably, 96.18% of the contigs from the “Nanopore assembly” were successfully anchored to nine chromosomes, with a scaffold N50 of 54.61 Mb and 99.80% BUSCO completeness (1.7% duplicated genes) (Table 1), indicating relatively high assembly integrity (Fig. 2c,d).

Genome annotation

We choose several reference species to assist annotation, including five other coleopteran species (Scarabaeoidea: Onthophagus taurus (GCA_000648695.2), Oryctes borbonicus38 (GCA_902654985.2), Trypoxylus dichotomus39 (GCA_023509865.1); Staphylinidea: Nicrophorus vespilloides40 (GCA_001412225.1); Tenebrionoidea: Tribolium castaneum41 (GCA_000002335.3)), and one dipteran species, Drosophila melanogaster42 (GCA_000001215.4). We uploaded the detailed species information table to figshare43. Initially, we annotated repetitive sequences in the D. hopei genome by identifying LTRs and tandem repeats using LTR_Finder v1.0544 and Tandem Repeat Finder v4.07b45, respectively. Transposable elements (TEs), including DNA elements, long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs), short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs), and long terminal repeats (LTRs), were next identified using RepeatMasker v4.0.546 against a de novo repeat library constructed with RepeatModeler v1.0.447 and Repbase TE library v16.0248 separately at the DNA level. Finally, TE-relevant proteins were identified using RepeatProteinMask v4.0.947 at the protein level. The final genome assembly (Hi-C assembly) of D. hopei comprised 57.45% repetitive sequences, totaling approximately 285.27 Mb, which is almost twice that of T. castaneum (31.15%) (Fig. 2e). Among the repetitive sequences in the D. hopei genome, the major categories included unclassified sequences (32.39%), DNA elements (11.36%) with maximum density in each chromosome, LINEs (7.95%), and LTRs (7.55%) (Fig. 2f).

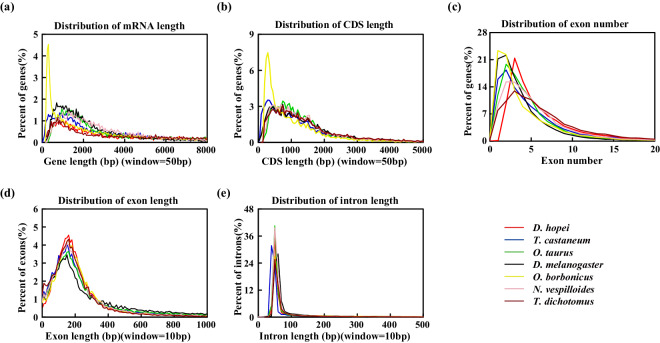

Protein-coding genes were predicted using a combination of de novo-, homology-, and transcriptome-based approaches. We utilized the repeat-masked genome and applied the de novo-based gene prediction software Augustus v3.4.049, using models trained on protein sequences from the O. borbonicus genome38, with default parameters. TBLASTN v2.12.050 and GeneWise v2.4.151 were used for homology prediction. The transcriptome data were then aligned to the genome using HISAT2 v2.0.0-beta52. Based on the resulting BAM files and reference genome, the transcriptomic sequences were assembled using StringTie v2.1.453. To form a comprehensive, non-redundant set of genes, we performed several integrations using EVidenceModeler (EVM) v1.1.154, assigning different weight values to the seven genomes based on their BUSCO scores and gene structure components (gene length, coding sequence length, exon number and length, and intron length). The EVM gene set with the best BUSCO value and gene structure components was then selected as the final gene prediction. Finally, resulting in the annotation of 11,231 protein-coding genes in the D. hopei genome. We uploaded the complete gene annotation tables to figshare43. Compared to the different gene features of other six species, the D. hopei genome annotations were comprehensive (Fig. 3), further validating the quality and accuracy of the genome annotation.

Fig. 3.

Distribution statistics of gene features among the seven species. The comparison of (a) mRNA length, (b) CDS length, (c) exon number, (d) exon length and (e) intron length in D. hopei and other six species.

Finally, we performed functional annotation of the genome. The protein sequences of the genome were searched for homology-based function assignments against the KEGG, NR, TrEMBL, and SwissProt databases using BLASTP v2.2.2655 with an e-value cut-off of 1e-5. Domains in the D. hopei genome using InterProScan v5.54–87.056 with InterPro and GO database. And combined above results, 88.52% of the predicted genes were functionally annotated using six functional protein databases (Table 2).

Table 2.

Statistics of functional annotation of the Dorcus hopei protein-coding genes.

| Functional database | Number of genes annotated (11,231) |

|---|---|

| Annotated | 9,942 (88.52%) |

| Unannotated | 1,289 (11.48%) |

| InterPro | 8,737 (77.79%) |

| GO | 8,737 (77.79%) |

| KEGG | 6,556 (58.37%) |

| SwissProt | 7,654 (68.15%) |

| TrEMBL | 9,779 (87.07%) |

| NR | 9,838 (87.60%) |

Data Records

The chromosome-level assembly and annotation file of D. hopei has been deposited in figshare database57. Raw sequencing data (Illumina reads, Nanopore reads, Hi-C reads, RNA-seq reads) and sample information are available at NCBI, which can be found under identification number SRP44076458. The assembly also has been deposited in NCBI with the accession number GCA_033060865.159. More detailed information about selected species, the results of genomic annotation (repeated sequences and gene structure), orthologs, and synteny has been deposited in figshare database43.

Technical Validation

Quality assessment of the assembled genome was performed using the following methods. Firstly, BWA v0.7.1760 was used to map the Illumina reads to the D. hopei assembly and Samtools v1.3.161 was used to calculate the mapping ratio. The Illumina short reads with a 99.10% accuracy ratio were mapped to the final assembly (Table 1). Secondly, compared N50 length/number with other six selected species. The D. hopei genome displayed a longer N50 (54.61 Mb) and better continuity compared to the chromosome-level genomes of T. castaneum and T. dichotomus (Fig. 2c). Thirdly, insecta_odb10 with 1,367 genes in BUSCO v5.2.262 was used to evaluate genome assembly and annotation completeness. The final assembly had 99.8% BUSCO scores with 0.1% fragmented and 0.1% missing sequences (Fig. 2d). Additionally, we got nine pairs of chromosomes based on Hi-C data, mirroring that of congeneric species Dorcus parallelipipedus63. All these results suggest that we got a high-quality assembly of D. hopei with high integrity, continuity and accuracy.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31872276, No. 31572311) and from Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Department (No. 202105AC160039). We are grateful to Professor Wen Wang (Kunming Institution of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and Northwestern Polytechnical University, China) for his support in bioinformatics analysis. We thank Yongjing Chen and Ziqi Li (Anhui University, China) for their assistance in sample collection.

Author contributions

Xueyan Li and Xia Wan conceived and supervised the study. Xiaoyan Bing, Guichun Liu, Zhiwei Dong, and Ruoping Zhao collected samples and sequencing data, and finished relevant experiments. Chuyang Mao and Jinwu He provided analysis guidance. Xiaolu Li and Chuyang Mao performed the analyses. Xiaolu Li wrote the manuscript. Xueyan Li and Xia Wan revised the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Code availability

No custom code was used in this study. The data analyses used standard bioinformatic tools specified in the methods.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Xiaolu Li, Chuyang Mao.

Contributor Information

Xia Wan, Email: wanxia@ahu.edu.cn.

Xueyan Li, Email: lixy@mail.kiz.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Wan X, Jiang Y, Cao Y, Sun B, Xiang X. Divergence in gut bacterial community structure between male and female stag beetles Odontolabis fallaciosa (Coleoptera, Lucanidae) Animals. 2020;10:2352. doi: 10.3390/ani10122352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arai T, et al. Discovery of hyperactive antifreeze protein from phylogenetically distant beetles questions its evolutionary origin. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:3637. doi: 10.3390/ijms22073637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goyens J, Dirckx J, Aerts P. Jaw morphology and fighting forces in stag beetles. J Exp Biol. 2016;219:2955–2961. doi: 10.1242/jeb.141614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gotoh H, et al. Juvenile hormone regulates extreme mandible growth in male stag beetles. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harvey DJ, Gange AC, Hawes CJ, Rink M. Bionomics and distribution of the stag beetle, Lucanus cervus (L.) across Europe*. Insect Conserv Divers. 2011;4:23–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4598.2010.00107.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kubota K, et al. Evolutionary relationship between Platycerus stag beetles and their mycangium-associated yeast symbionts. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1436. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hendriks P. Life cycle length of the lesser stag beetle (Coleoptera: Lucanidae: Dorcus parallelipipedus) Entomol Ber. 2019;79:208–216. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SI, Farrell BD. Phylogeny of world stag beetles (Coleoptera: Lucanidae) reveals a Gondwanan origin of Darwin’s stag beetle. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2015;86:35–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanahashi M, Ikeda H, Kubota K. Elementary budget of stag beetle larvae associated with selective utilization of nitrogen in decaying wood. Sci Nat. 2018;105:33. doi: 10.1007/s00114-018-1557-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darwin, C. The Descent Of Man, And Selection In Relation To Sex, Vol 1 (John Murray, 1871).

- 11.Pennisi E. Insulin may guarantee the honesty of beetle’s massive horn. Science. 2012;337:408. doi: 10.1126/science.337.6093.408-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mills MR, et al. Functional mechanics of beetle mandibles: honest signaling in a sexually selected system. J Exp Zool A Ecol Integr Physiol. 2016;325A:3–12. doi: 10.1002/jez.1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang M, et al. Geometric morphometric analysis of the pronotum and elytron in stag beetles: insight into its diversity and evolution. Zookeys. 2019;833:21–40. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.833.26164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartolozzi L, Norbiato M, Cianferoni F. A review of geographical distribution of the stag beetles in Mediterranean countries (Coleoptera: Lucanidae) Fragm Entomol. 2016;48:153–168. doi: 10.4081/fe.2016.182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Méndez M, Thomaes A. Biology and conservation of the European stag beetle: recent advances and lessons learned. Insect Conserv Divers. 2021;14:271–284. doi: 10.1111/icad.12465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kubota K, et al. Diversification process of stag beetles belonging to the genus Platycerus Geoffroy (Coleoptera: Lucanidae) in Japan based on nuclear and mitochondrial genes. Entomol Sci. 2011;14:411–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8298.2011.00466.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuan JJ, Chen D, Wan X. A multilocus assessment reveals two new synonymies for East Asian Cyclommatus stag beetles (Coleoptera, Lucanidae) ZooKeys. 2021;1021:65–79. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.1021.58832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin Z-Q, Song F, Li T, Wu Y-Y, Wan X. New mitogenomes of two Chinese stag beetles (Coleoptera, Lucanidae) and their implications for systematics. J Insect Sci. 2017;17:63. doi: 10.1093/jisesa/iex041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeng L, et al. Comparative mitochondrial genomics of five Dermestid beetles (Coleoptera: Dermestidae) and its implications for phylogeny. Genomics. 2021;113:927–934. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2020.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang J-P, Lin C-P. Diversification in subtropical mountains: Phylogeography, Pleistocene demographic expansion, and evolution of polyphenic mandibles in Taiwanese stag beetle, Lucanus formosanus. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2010;57:1149–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nobrega MA, Pennacchio LA. Comparative genomic analysis as a tool for biological discovery. J Physiol. 2004;554:31–39. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.050948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen L, et al. Large-scale ruminant genome sequencing provides insights into their evolution and distinct traits. Science. 2019;364:eaav6202. doi: 10.1126/science.aav6202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaiswal SK, et al. Genome sequence of peacock reveals the peculiar case of a glittering bird. Front Genet. 2018;9:392. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prost S, et al. Comparative analyses identify genomic features potentially involved in the evolution of birds-of-paradise. GigaScience. 2019;8:giz003. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giz003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu YG, Linz DM, Moczek AP. Beetle horns evolved from wing serial homologs. Science. 2019;366:1004–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw2980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morita S, et al. The draft genome sequence of the Japanese rhinoceros beetle Trypoxylus dichotomus septentrionalis towards an understanding of horn formation. Sci Rep. 2023;13:8735. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-35246-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kenzaka T, Yamada Y, Tani K. Draft genome sequence of an antifungal bacterium isolated from the breeding environment of Dorcus hopei binodulosus. Genome Announc. 2014;2:e00424–00414. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00424-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Y, Liu J, Cao Y, Zhou S, Wan X. Two new complete mitochondrial genomes of Dorcus stag beetles (Coleoptera, Lucanidae) Genes Genom. 2018;40:873–880. doi: 10.1007/s13258-018-0699-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huxley JS. Relative growth of mandibles in stag-beetles (Lucanidae)*. Zool J Linn Soc. 1931;37:675–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1931.tb02368.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emlen DJ, Nijhout HF. The development and evolution of exaggerated morphologies in insects. Annu Rev Entomol. 2000;45:661–708. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.45.1.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rowland JM, Emlen DJ. Two thresholds, three male forms result in facultative male trimorphism in beetles. Science. 2009;323:773–776. doi: 10.1126/science.1167345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, B. H. et al. Estimation of genomic characteristicsby analyzing k-mer frequency in de novo genome projects. Preprint at 10.48550/arXiv.1308.2012 (2013).

- 33.Guan DF, et al. Identifying and removing haplotypic duplication in primary genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:2896–2898. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu J, Fan JP, Sun ZY, Liu SL. NextPolish: a fast and efficient genome polishing tool for long-read assembly. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:2253–2255. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Servant, N. et al. HiC-Pro: an optimized and flexible pipeline for Hi-C data processing. Genome Biol. 16 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Durand NC, et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 2016;3:95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Durand NC, et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst. 2016;3:99–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyer JM, et al. Draft genome of the scarab beetle Oryctes borbonicus on La Réunion Island. Genome Biol Evol. 2016;8:2093–2105. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Q, Liu L, Zhang S, Wu H, Huang J. A chromosome-level genome assembly and intestinal transcriptome of Trypoxylus dichotomus (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) to understand its lignocellulose digestion ability. GigaScience. 2022;11:giac059. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giac059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cunningham CB, et al. The genome and methylome of a beetle with complex social behavior, Nicrophorus vespilloides (Coleoptera: Silphidae) Genome Biol Evol. 2015;7:3383–3396. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tribolium Genome Sequencing Consortium The genome of the model beetle and pest Tribolium castaneum. Nature. 2008;452:949–955. doi: 10.1038/nature06784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoskins RA, et al. The Release 6 reference sequence of the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Genome research. 2015;25:445–458. doi: 10.1101/gr.185579.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li X. 2023. Detailed tables for genome assembly and annotations of Dorcus hopei (Coleoptera: Lucanidae) figshare. [DOI]

- 44.Xu Z, Wang H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W265–W268. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tarailo-Graovac M, Chen N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2009;25:4.10.11–14.10.14. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flynn JM, et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:9451–9457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1921046117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bao W, Kojima KK, Kohany O. Repbase Update, a database of repetitive elements in eukaryotic genomes. Mob DNA. 2015;6:11. doi: 10.1186/s13100-015-0041-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stanke M, et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W435–W439. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gertz EM, Yu YK, Agarwala R, Schäffer AA, Altschul SF. Composition-based statistics and translated nucleotide searches: improving the TBLASTN module of BLAST. BMC Biol. 2006;4:41. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-4-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Birney E, Clamp M, Durbin R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res. 2004;14:988–995. doi: 10.1101/gr.1865504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim D, Landmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12:357–U121. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kovaka S, et al. Transcriptome assembly from long-read RNA-seq alignments with StringTie2. Genome Biol. 2019;20:278. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1910-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haas BJ, et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the program to assemble spliced alignments. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Camacho C, et al. BLAST plus: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mulder N, Apweiler R. InterPro and InterProScan: tools for protein sequence classification and comparison. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;396:59–70. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-515-2_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li X. 2023. Genome assembly and annotations of Dorcus hopei (Coleoptera: Lucanidae) figshare. [DOI]

- 58.2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP440764

- 59.Li X, 2023. Genome assembly AHU_Dhop_1.0. GenBank. GCA_033060865.1

- 60.Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. Preprint at 10.48550/arXiv.1303.3997 (2013).

- 61.Danecek P, et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience. 2021;10:giab008. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giab008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Simao FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Colomba MS, Vitturi R, Zunino M. Chromosome analysis and rDNA FISH in the stag beetle Dorcus parallelipipedus L. (Coleoptera: Scarabaeoidea: Lucanidae) Hereditas. 2000;133:249–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.2000.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Li X. 2023. Detailed tables for genome assembly and annotations of Dorcus hopei (Coleoptera: Lucanidae) figshare. [DOI]

- Li X. 2023. Genome assembly and annotations of Dorcus hopei (Coleoptera: Lucanidae) figshare. [DOI]

- 2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP440764

- Li X, 2023. Genome assembly AHU_Dhop_1.0. GenBank. GCA_033060865.1

Data Availability Statement

No custom code was used in this study. The data analyses used standard bioinformatic tools specified in the methods.