Abstract

Using data from the Chicago Longitudinal Study (CLS), an ongoing investigation of a panel of low-income minority children growing up in an inner city, this study investigated whether retention is associated with participation in postsecondary education and public aid receipt. The study sample included 1,367 participants whose data were available for grade retention and educational attainment by age 24. Findings from both regression and propensity score matching indicated that grade retention was significantly associated with lower rates of participation in postsecondary education. Late retention (between fourth and eighth grades) was more strongly linked to lower rates of postsecondary education than early retention (between first and third grades). There was no significant association between retention and public aid receipt.

Keywords: grade retention, postsecondary education, public assistance programs

Introduction

Grade retention has been implemented for decades as an intervention to improve academic proficiency, although its effectiveness on either academic or social-behavioral difficulties has not been consistently reported. Nonetheless, ending social promotion in late 1990s probably has increased the numbers of students who got retained (Heubert & Hauser, 1999). There are no systematic national estimates of the number of students held back each year or of the cost to the public, but Eide and Showalter (2001) estimated that the cost of retention is approximately $2.6 billion per year and affects about 450,000 children when the annual retention rate is assumed at 1%. The cost was estimated based on the annual cost of education only and did not take into account other costs related to retention, such as the cost related to increasing high school dropout rates. The cost is conservative because recent estimates of annual retention rate from other sources are between 7 and 15% (Jimerson, Pletcher, Graydon, Schnurr, Nickerson, & Kundert, 2006). Moreover, among youth ages 16–19 enrolled in high school in 2004, 11.7% had ever been retained in a grade (U.S. Department of Education, 2006).

Given the cost and number of students retained, it is imperative to understand if grade retention is associated with long-term outcomes in addition to academic achievement. If there are associations between grade retention and long-term outcomes, are those associations positive or negative to students’ development? The findings will shed light on the effectiveness of this common practice. In addition, the findings will provide policymakers with important information on the likely cost-effectiveness of retention. The purpose of the present study is to examine the relations between grade retention and two long-term outcomes: postsecondary education participation and public aid receipt.

Grade Retention and Academic Achievement

Grade retention is often used to promote better academic performance and school adjustment. The assumption is that students would be less likely to fail if they have prerequisite skills before they move on to the next grade. Therefore, the potential effects of grade retention should be expected on academic achievement and socio-emotional development. However, majority of the research on grade retention has focused on academic achievement and educational outcomes over the last several decades. Several meta-analyses have been conducted (Holmes, 1989; Holmes & Matthews, 1984; Jackson, 1975; Jimerson, 2001), and authors conclude consistently that grade retention failed to demonstrate greater benefits to students with academic or adjustment difficulties than did promotion to the next grade. The relation between grade retention and academic achievement is discussed here, and findings on social-emotional development are discussed in the next section.

Most studies have shown that either retained students did not perform better academically than low-achieving promoted peers (Beebe-Frankenberger, Bocian, MacMillan & Gresham, 2004; Hong & Raudenbush, 2005; Jimerson, Carlson, Rotert, Egeland & Sroufe, 1997; Silberglitt, Appleton, Burns & Jimerson, 2006) or a negative association between grade retention and academic achievement (Hong & Yu, 2007; McCoy & Reynolds, 1999; Reynolds, 1992). Since the policy of end social promotion was adopted in several large cities and states, the number of studies evaluating the effects of grade retention has been increasing. Most studies have evaluated short- rather than long-term. Short-term gains after retention were frequently reported.

Findings from Florida show that retained students substantially improved academic achievement one year and two years after initial retention relative to the socially promoted students (Greene & Winters, 2004, 2006, 2007). Using longitudinal data (across 6 years) from a cohort of Texas students, researchers found that both grade retention and social promotion were associated with sustained gains (Lorence, Dworkin, Toenhes & Hill, 2002). Although some findings favored the retained students, the gains from retention did not last (Jacob & Lefgren, 2004; Roderick & Nagaoka, 2005). For instance, some studies compared the gains of students whose test scores were just above the threshold (promoted) with those students whose test scores were just below the threshold (retained) under the context of test-based promotion in Chicago (Jacob & Lefgren, 2004; Roderick & Nagaoka, 2005). Their findings show that retained students made gains in reading and math one year after retention, but in the second year these gains disappeared, and became insignificant or negative several years later (Jacob & Lefgren, 2004; Roderick & Nagaoka, 2005). Moreover, a recent study of an at-risk sample indicates that grade retention decreased the growth rate of mathematical skills but had no significant effect on reading skills (Wu, West & Hughes, 2008).

Grade Retention, Social-emotional Development, and Timing of Retention

The effects of grade retention on social-emotional and behavioral adjustment have been investigated (Jimerson & Ferguson, 2007; McCoy & Reynolds, 1999; Reynolds, 1992). Findings on social development are inconsistent. For instance, some findings indicate that retention might have negative influence on social adjustment and behavior, such as low self-esteem, poor social adjustment, negative attitudes toward school, and problem behaviors (Jimerson et al., 1997; Jimerson & Ferguson, 2007; Nagin, Pagani, Tremblay, & Vitaro, 2003). Others indicate that there was no evidence of negative effects of grade retention on problem behaviors (Gottfredson, Fink & Graham, 1994), delinquency (McCoy & Reynolds, 1999), and social-emotional development (Hong & Yu, 2008). However, Reynolds (1992) found that retention was positively and associated with children’s perceived school competence.

In addition to the relation between grade retention and socio-emotional development, it is also important to understand students’ perspectives on grade retention, because how students perceive grade retention may affect their psychological well-being. Grade retention was rated as one of the most stressful life events by students in some studies (Anderson, Jimerson, & Whipple, 2005; Yamamoto & Byrnes, 1987). It is worth noting the potential negative effect of retention on self-esteem and that social-emotional effects may vary by grade, with older students experiencing greater effects due to the internalization of peer group norms. Curriculum content and expectations for academic progress also differs across grades. Thus, the timing of retention may have different impacts on students.

Few studies have been conducted on the effects of the timing of retention. Many studies have focused on retention between kindergarten and the third grade. In particular, third grade retention has been examined because of the high-stakes testing policy. Few studies have examined retention after the third grade, and findings indicate the different effects between early and late retention. McCoy and Reynolds (1999) found that the effects of early grade retention (grades 1–3) were similar to those of later grade retention (grades 4–7). Jacob & Lefgren (2004) found that retention increased achievement for third-grade students but had little effect on math achievement for sixth-grade students. Jacob & Lefgren (2009) found that grade retention leaded to a modest increase in the probability of dropping out for older students (8th grade), but had no significant effect on younger students (6th grade). Temple, Reynolds & Ou (2004) found that late retention was significantly associated with a higher probability of dropping out than early retention, although both early and late retention were significantly associated with higher rates of dropout.

Grade Retention, Dropout, and Adult Outcomes

It is important to understand whether grade retention is associated with long-term outcomes other than academic achievement for two major reasons. The first reason is related to the implications behind such associations. If the experience of grade retention is associated with negative outcomes in adulthood, it might not be worthwhile even if grade retention can improve academic achievement during elementary grades, because the overall impact of grade retention would be negative (Beebe-Frankenberger et al., 2004; Greene & Winters, 2007). For example, if grade retention improves academic achievement but increases the probability of school dropout, the positive effects on achievement would not benefit the students much. Many studies have showed positive associations between grade retention and high school dropout (Alexander, Entwisle, Dauber, & Kabbani, 2004; Eide & Showalter, 2001; Jimerson, 1999; Guèvremont, Roos, Brownell, 2007, Jimerson, Anderson, & Whipple, 2002; Jimerson, Ferguson, Whipple, Anderson, & Dalton, 2002; Jimerson & Kaufman, 2003; Rumberger, 1995; Temple et al., 2004). Moreover, grade retention is an important predictor of dropout in many studies (Alexander, Entwisle & Horsey, 1999; Alexander, Entwisle & Kabbani, 2001; Ensminger & Slusarick, 1992; Janosz, LeBlanc, Boulerice & Tremblay, 1997; Rumberger, 1987, 1995).

Most studies examine outcomes right after retention or through high school. There are few studies examining the effects of grade retention beyond high school. Fine and Davis (2003) found that grade retention was associated with lower rates of enrollment in 4-year colleges and in postsecondary education. Eide and Showalter (2001) found a negative association with post-high school labor market earnings. In a syntheses of longitudinal studies of early intervention, Royce, Darlington, and Murray (1983) found that retained students were less likely to successfully adapt to mainstream society (Royce, Darlington & Murray, 1983). Their definition of adaptation included enrollment in an educational program, military service, weekly earnings from employment beyond a specific threshold, temporarily laid off, or living with a working spouse/companion. Participants who were unemployed, not in the labor force, in prison, or receiving public assistance as the major source of income were defined as not adaptive. These findings indicate that grade retention functioned as a mediator for the effects of early childhood programs on young adult outcomes.

The second reason is related to the cost to society. To understand the costs and benefits of grade retention, it is important to know whether grade retention is associated with long-term outcomes, such as postsecondary education attendance or employment status, beyond academic achievement (Eide & Goldhaber, 2005). If grade retention improves academic achievement in a short period of time, but increases the risk of dropping out or other negative outcomes ultimately, its overall impact would be negative, and the possible improvement of academic achievement might not be worth the cost.

To summarize, findings on the effects of grade retention are mixed. The drawbacks on data and methods reduce the credibility of findings from previous studies. For example, most studies have small sample sizes (sometimes less than 150), and have been criticized for their reliabilities of findings because of non-experimental designs. However, recent studies have utilized advanced methodologies, such as propensity score (Hong & Raudenbush, 2005; Hong & Yu, 2007, 2008; Wu et al., 2008) and regression discountinuity design (Jacob & Lefgren, 2004, 2009), which increase the credibility of findings. Recent findings seem to merge into the conclusion that early retention may be positively associated with academic achievement but gains do not endure beyond 2 years. Moreover, few longitudinal studies have examined comprehensively the links between grade retention and adult outcomes.

In this study, we examined the association between grade retention and enrollment in postsecondary education and public aid receipt. These two adult outcomes were selected for several reasons. First, postsecondary education and labor market outcomes are the only long-term outcomes examined in previous studies of adult outcomes. Replicating the analysis on similar adult outcomes with a different data set and methods will provide a stringent test of long-term effects. Because direct labor market outcomes were not available, we used public aid receipt as an indicator of economic self-sufficiency. Second, to explore the potential long-term outcomes, it is logical to start from outcomes related to academic achievement or dropout, as the relations between grade retention and academic achievement and between grade retention and dropout have been found in many studies. Because academic achievement and school dropout are strong predictors of postsecondary education, it is reasonable to expect an inverse relation between retention and postsecondary education. Moreover, studies have shown that people who lack a high school degree are at risk of receiving public assistance (i.e. Aid to Families with Dependent Children, or AFDC and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or TANF, food stamps, and Medicaid) (Waldfogel, Garfinkel & Kelly, 2005). Moreover, the correlation between public aid receipt and unemployment is well known.

Present Study

Using data in the Chicago Longitudinal Study (CLS, 2005), three major questions are addressed: 1) Is grade retention by eighth grade associated with participation in postsecondary education and public aid receipt? 2) Is timing of retention (early versus late) associated with participation in postsecondary education and public aid receipt differently? 3) If so, what is the pattern of differential effects by outcome?

Although the setting of the present study is Chicago, the same as several retention studies, the context of retention differs between the present and previous studies. For example, Roderick & Nagaoka (2005) examined the effects of retention under high-stakes testing, but retention in the present study was before the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) declared an “end to social promotion” and instituted a test-based retention/promotion policy. Before the high-stakes testing policy, retention was based on multiple criteria including test scores, grades, and other teacher assessments of student performance. Moreover, retention was considered as a last resort or “only after all other intervention strategies have failed” (Chicago Public Schools, 1985, p. 2). Another notable difference was the level of remedial education available. Under the more recent test-based promotion policy, remedial education for students at risk of retention was more systematic than during the time frame of our study, including mandatory summer school for students below test score cut-offs. During the retention year, however, remediation strategies were no more systematic than in previous years. Although these differences should be considered when interpreting effects across studies, the main contrast between those students who are well behind their peers in performance versus those that are not remains conceptually the same.

The present study is unique in several important respects. First, the CLS is an on-going 20-year study of the life course of 1,500 children attending the Chicago Public Schools no later than kindergarten. Prospective longitudinal studies are the methodologically strong designs for assessing the potential causal links between childhood experiences and young adult outcomes. Few studies have data for more than 6 years after initial retention, which makes it difficult to examine long-term outcomes.

Second, the present study included over 1,300 participants from the original study, which is a much larger sample sizes than most previous studies. Although recent studies evaluating the effects of “ending social promotion” or “high-stakes testing” have larger sample sizes, some previous findings are based on sample sizes less than 800 or less than 150 even.

Third, the present study examined the effects of early retention and late retention. Timing of retention has been found to be differentially associated with academic achievement. However, timing is rarely investigated as most studies did not have large enough samples or data on long-term outcomes.

Fourth, two different statistical approaches, regression analysis and propensity score matching, were used to estimate the effects of retention. Because of the potential threat of selection bias in the interpretation of the link between retention and adult outcomes, alternative methods of estimation are recommended. To the extent that findings are consistent across methods and model specification, confidence in the internal validity of findings is strengthened.

Finally, the present study examined 2 adult outcomes: participation in postsecondary education and public aid receipt. Few studies have examined long-term effects of grade retention that extend beyond high school. The near exclusive focus has been on the relations between grade retention and academic achievement, and between grade retention and school dropout. Consistent with the larger literature, previous findings in the CLS found a negative association between retention and academic achievement, and a positive association between retention and school dropout.

Method

Sample and Data

The study sample was drawn from the Chicago Longitudinal Study (CLS), an on-going investigation of a panel of low-income minority children growing up in high-poverty neighborhoods in Chicago. The study sample was at risk of school failure due to poverty. The original sample (N=1,539) included 989 children who entered the Chicago Child-Parent Center (CPC) program in preschool and graduated from kindergarten in 1986 from 20 Centers, and 550 children who participated in alternative government-funded programs in the Chicago Public Schools in 1986 without CPC preschool experience. Continuously promoted children graduated from high school in 1998.

A significant proportion (over 60%) of the study sample participated in the CPC program. The CPC Program is a center-based early childhood intervention that serves high-poverty neighborhoods that are not being served by Head Start or other early intervention programs. Eligible children may attend the program for up to six years from ages 3 to 9. The main goal of the CPCs is to promote children’s school competence, especially school readiness and academic achievement, by providing comprehensive educational and family-support services. The CPC program has operated continuously in the Chicago schools since 1967. See Reynolds (2000) for more information. The CPC preschool program has been found to be associated with positive long-term outcomes, such as lower rates of grade retention, juvenile arrest, and incarceration, and a higher rate of high school completion (Reynolds, Temple, Robertson, & Mann, 2001; Reynolds, Temple, Ou, Robertson, Mersky, Topitzes et al., 2007). Program participation was included as a covariate in the analysis.

The study sample included 1,367 youth (88.8% of the original sample) for whom data were available for grade retention in the elementary grades and status of educational attainment could be determined by August 2004 (mean age = 24). Students in and outside of the Chicago Public Schools were located for status of postsecondary education. Data have been collected longitudinally starting from child’s birth from various sources, such as participants, parents, teachers, school records, and administrative records (Chicago Longitudinal Study, 2005; Reynolds, 2000). Outcome measures of the present study were collected through administrative records and were supplemented with self-report for educational attainment.

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study sample. Characteristics include background information (such as gender, race/ethnicity, family risk status, parents’ educational attainment and family structure), early scholastic abilities, and CPC program participation. There are significant differences between the retention and promotion groups in most characteristics except for percent 4 or more children in household by child’s age 4, percent mother was teen at child’s birth, percent 60% or more poverty in school attendance area, and any child welfare histories by child’s age 4. Those characteristics were used as covariates to ensure that the differences between the groups were not due to background characteristics. The changes in test scores between kindergarten and first grade were also examined in Table 1. Although there was significant difference between the retention and promotion groups (p < .01), the difference was no longer significant after controlling for sociodemographic factors (characteristics in Table 1).

Table 1.

Child Characteristics of the Study Sample

| Characteristics | Study sample (N =1,367) | Retention (n=348) | Promotion (n=1,019) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent black | 93.3 | 93.4 | 93.2 | 1.00 |

| Percent female | 51.7 | 36.5 | 56.9 | .000 |

| Percent eligible for free lunch by child’s age 4 | 82.8 | 89.1 | 80.6 | .000 |

| Percent mother did not completed high school by child’s age 4 | 53.4 | 64.5 | 49.5 | .000 |

| Percent single parent by child’s age 4 | 75.8 | 79.8 | 74.4 | .047 |

| Percent 4 or more children in household by child’s age 4 | 17.6 | 16.6 | 18.0 | .620 |

| Percent mother was less than 18 years old at child’s birth | 17.1 | 20.0 | 16.1 | .096 |

| Percent mother unemployed by child’s age 4 | 62.9 | 70.2 | 60.2 | .001 |

| Percent TANF/AFDC participation by child’s age 4 | 61.8 | 68.4 | 59.4 | .003 |

| Percent 60% or more poverty in school attendance area | 75.9 | 75.3 | 76.2 | .772 |

| Percent any child welfare case histories by child’s age 4 | 3.9 | 4.9 | 3.5 | .253 |

| Percent missing any sociodemographic factor | 13.4 | 9.2 | 14.8 | .008 |

| Number of Family risk index | 4.50 | 4.85 | 4.39 | .000 |

| Percent participation in CPC preschool program | 64.9 | 55.5 | 68.1 | .000 |

| Percent participation in CPC school-age program | 56.2 | 46.6 | 59.5 | .000 |

| ITBS word analysis in Kindergarten | 63.99 | 56.72 | 66.46 | .000 |

| ITBS reading score at first grade | 73.82 | 64.04 | 76.91 | .000 |

| Changes in ITBS scores between first grade and Kindergarten | 13.44 | 10.68 | 14.31 | .000 |

| Number of school moves (1st to 8th grades) | 2.30 | 2.41 | 2.26 | .079 |

Measures

Grade retention.

Grade retention was defined as any incidence of grade retention from first grade through eighth grade (ages 6 through 14). Children who were ever retained during this period were coded 1. Children who were never retained (continuously promoted) were coded 0. Data were derived from year to year school administrative records of grade placements. In the study sample, 38 participants were retained multiple times. For the years of elementary school attendance (1986–1995), the Chicago Board of Education retention policy was that “a student shall not be promoted from one grade to the next if the student has not met the minimum levels of performance from the assigned grade levels” but further stated that retention should be used as a last resort or “only if all other intervention strategies have failed” (Chicago Public Schools, 1985, p. 2).

To distinguish the retention groups better, kindergarten retention was not examined in the present study. There were 19 children who retained in kindergarten. Among the 19 children, 14 were retained again later, and 5 were not retained again. Five children retained only in kindergarten were excluded from the present study, which resulted in sample sizes of 1,367 for educational attainment and 1,310 for public aid receipt.

Timing of retention was measured by two dichotomous variables: early retention and late retention. Early retention indicates if one had been retained in first to third grades. Late retention indicates if one had been retained in fourth to eighth grades. Twenty-four students were retained both early and late. Those students were included in the analysis of overall retention, but were excluded from the analysis of timing of retention. When both early and late retention were examined in the regression model, the reference group was the promotion group.

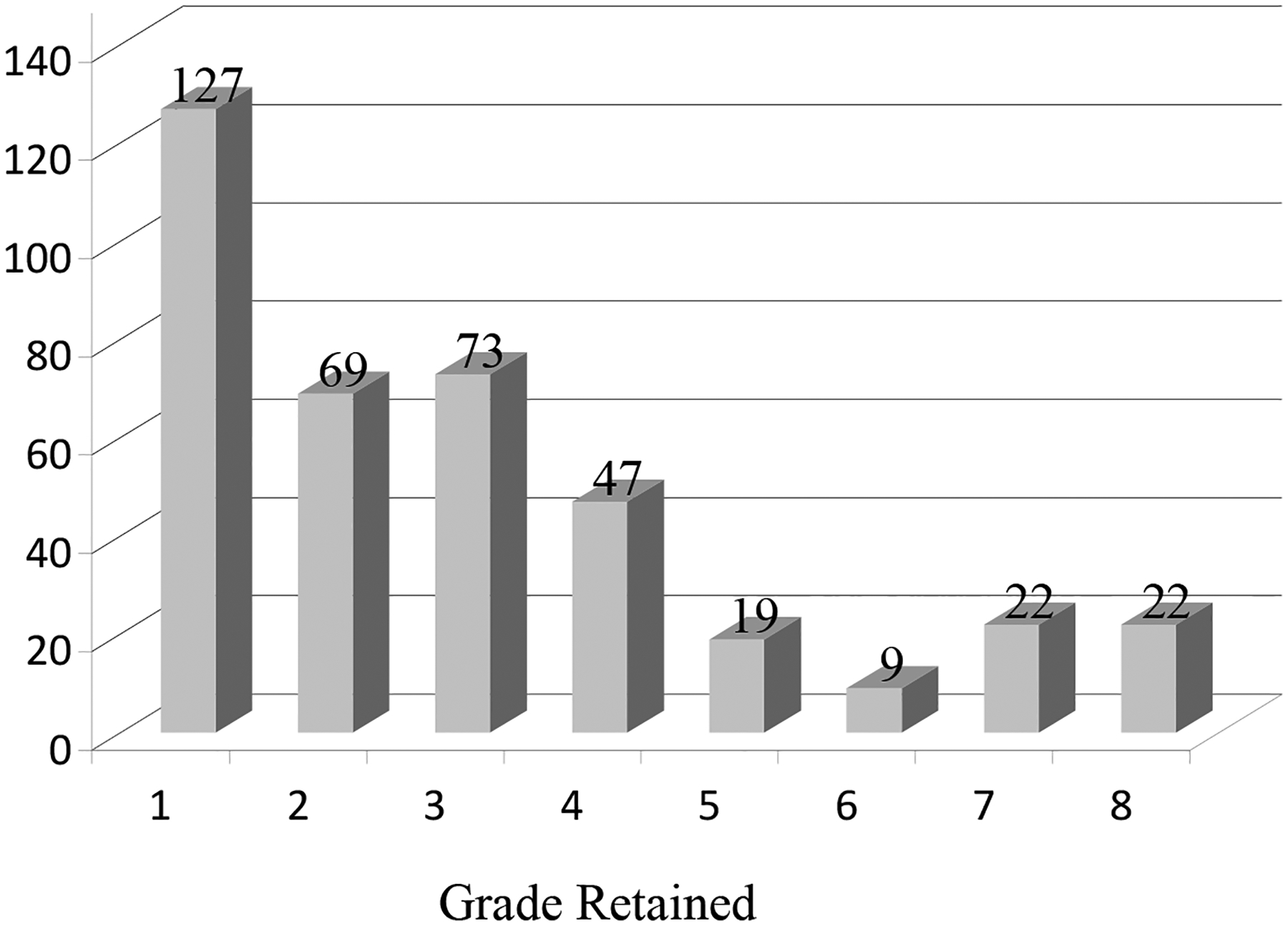

Based on the policies of ending social promotion and high-stakes test, third grade is the first gate-grade for students to be retained in many large cities. As a result, some studies have investigated effects between third grade and sixth grade retention. In addition, previous studies have focused on retention between kindergarten and third grade, and very few studies examined retention after third grade. Separating retention by third grade can increase the compatibility of the present study with findings from other studies. Moreover, the number of retained students dropped after third grade in the study sample. First grade through third grade had more students retained than in other grades. Given the above reasons, third grade was selected to be the cut-off point between early and late retention in the present study. Figure 1 presents the numbers of students who were retained by grade in the study sample. Students retained multiple times were included.

Figure 1.

Numbers of students retained by grade

Outcomes measures.

Postsecondary education was measured by three dichotomous measures: 1) any college attendance, 2) 2-year college attendance, and 3) 4-year college attendance. Because of the different requirements and benefits associated with 2- and 4-year college attendance, three dichotomous measures were used instead of a nominal measure indicating different types of attendance. In addition, students are likely to have attended both 2- and 4-year colleges. Students can also transfer from a 2-year to a 4-year college. Separate measures can capture those students independently. Although 4-year college attendance has been the focus in most research, 2-year college attendance is an important path for minority economically disadvantaged students like those in the study sample. Data were obtained from administrative records in all schools youth attended in Illinois and other states, and were supplemented by self-reports for those who administrative records were not available.

College attendance indicates whether youth ever attended college (2- or 4-year college). Participants who received at least 0.5 college credit was coded 1; otherwise they were coded 0 (never attended college). To obtain a clear comparison on college attendance, certain participants were excluded from the 2 dichotomous measures of 2-year college attendance and 4-year college attendance. Two-year college attendance indicates whether a participant ever attended a 2-year college (coded 1). Those who never attended such an institution were coded 0. participants who attended only a 4-year colleges were excluded from this measure. Four-year college attendance indicates whether a participant ever attended a 4-year college (coded 1). Those who never attended a 4-year college were coded 0. Participants who attended only a 2-year college were excluded from this measure. Due to the exclusion of participants, the sample sizes were, respectively, 1,367, 1,175, and 1,059 for any college attendance, 2-year college attendance, and 4-year college attendance.

Public aid receipt was measured by four dichotomous measures: participation in Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF; previously Aid to Families with Dependent Children [AFDC]), participation in Food Stamps, participation in Medicaid, and participation in any of TANF, Food Stamps, or Medicaid. Public aid receipt was measured from February 1999 to January 2004. Study participants’ ages were between 19 and 24. Data were obtained from the Illinois Longitudinal Public Assistance Research Database (ILPARD). The sample (n=1,310) included youth who residing in Illinois in 1999 or later based on available administrative records.

Covariates.

Research shows that certain characteristics, such as gender (male), low-income families, minority, poor academic achievement, and low parent involvement in school, are associated with grade retention (Alexander, Entwisle & Dauber, 2003; Gottffredson, et al., 1994; Jimerson, et al., 1997; McCoy & Reynolds, 1999; Reynolds, 1992). As showed in Table 1, there are significant differences between the retention and promotion groups for most of the characteristics. To adjust for these differences, many sociodemographic measures were included in the analyses. They included race/ethnicity, gender, maternal education, free lunch eligibility, single parent status, teen parent status, family size, public aid receipt (AFDC/TANF), and status of child welfare history by child’s age 4. All were measured through dichotomous variables. Maternal education and family size were measured through dichotomous variables because previous studies from the CLS showed that family background was better reflected by measures indicating passing a certain threshold. For the covariates, participants who have such characteristics were coded 1; otherwise they were coded 0. For each covariate, missing values were imputed through the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm for multiple imputation based on gender, race/ethnicity, percent poverty in school attendance area, and CPC preschool participation.

Because the CPC program has been found to be associated with a lower rate of grade retention, CPC program participation was included as a covariate. CPC program participation was measured through two dichotomous measures: preschool participation and school-age program participation. Early scholastic abilities were used as covariates to control the initial differences in cognitive abilities. Two measures were used: the Iowa Test Basic Skills (ITBS) word analysis in kindergarten and ITBS reading comprehension subtest at first grade. The ITBS word analysis scale contained 35 items evaluating prereading skills, such as letter-sound recognition and rhyming (alpha = .87). The ITBS reading comprehension subtest includes 49 items on proficiency in understanding text passages (alpha = .93).

Two variables were used for additional analysis (mediational analysis): ITBS reading scores at age 14 and school dropout by age 19. The ITBS reading test at eighth grade is a continuous measure comprised of 58 items that emphasized understanding of text passages (alpha = .92). Dropout by age 19 is a dichotomous measure indicating whether participants were dropouts by age 19. Table 2 presents the descriptive information of key variables.

Table 2.

Description of Key Variables

| Variables | N | Mean | S.D. | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Factors | |||||

| Black | 1,367 | .93 | .251 | 0 | 1 |

| Female | 1,367 | .52 | .500 | 0 | 1 |

| Eligible for free school lunch | 1,316 | .83 | .377 | 0 | 1 |

| Mother not a high school completer | 1,325 | .53 | .499 | 0 | 1 |

| Single parent status | 1,328 | .76 | .429 | 0 | 1 |

| If had more than 4 children | 1,328 | .18 | .381 | 0 | 1 |

| Mother were less than 18 years at child’s birth | 1,337 | .17 | .376 | 0 | 1 |

| Mother unemployment status | 1,228 | .63 | .483 | 0 | 1 |

| TANF/AFDC participation | 1,314 | .62 | .486 | 0 | 1 |

| 60% or more poverty in school attendance area | 1,367 | .76 | .428 | 0 | 1 |

| Missing from any sociodemographic factor | 1,367 | .13 | .341 | 0 | 1 |

| Any child welfare history by age 4 | 1,297 | .04 | .193 | 0 | 1 |

| CPC Program and Early Scholastic Skills | |||||

| Preschool participation | 1,367 | .65 | .478 | 0 | 1 |

| School-age participation | 1,367 | .56 | .496 | 0 | 1 |

| ITBS word analysis Kindergarten | 1,361 | 64.00 | 13.24 | 19.00 | 99.00 |

| Grade Retention | |||||

| Any retention (1st to 8th grade) | 1,367 | .26 | .44 | 0 | 1 |

| Early retention (1st to 3rd grade) | 1,367 | .19 | .39 | 0 | 1 |

| Late retention (4th grade to 8th grade) | 1,367 | .08 | .28 | 0 | 1 |

| Both early and late retention | 1,367 | .02 | .13 | 0 | 1 |

| Outcome Measures | |||||

| 2- or 4-year college attendance | 1,367 | .34 | .47 | 0 | 1 |

| 2-year college attendance | 1,175 | .27 | .44 | 0 | 1 |

| 4-year college attendance | 1,059 | .19 | .39 | 0 | 1 |

| TANF | 1,310 | .27 | .44 | 0 | 1 |

| Food Stamps | 1,310 | .55 | .50 | 0 | 1 |

| Medicaid | 1,310 | .48 | .50 | 0 | 1 |

| Any public assistance | 1,310 | .62 | .49 | 0 | 1 |

Data Analysis

Unadjusted differences in postsecondary education and public aid receipt by retention status were examined using chi-square statistics. In addition, two types of analyses were conducted: regression and propensity score matching. Probit regression analysis was used to examine the differences in outcomes between the retention and promotion groups after adjusting for covariates. The covariates were included to ensure that the differences between groups were not from background characteristics. Marginal effects of retention were reported.

Second, propensity score matching was used to estimate the treatment effects of retention. Because randomized experiments are not always feasible, quasi-experiment designs and analyses to match groups are frequently used to strengthen confidence in inferences. Propensity-score techniques are among many recent approaches for reducing bias, and have been increasingly used in research on grade retention (Hong & Raudenbush, 2005; Hong & Yu, 2007, 2008).

Propensity scores reduce potential bias by creating matched treatment and comparison groups having comparable probabilities of being in the treatment group (retention/promotion) conditioned on a set of predictors (covariates). Propensity scores for each participant are estimated based on a logistic regression of treatment status (retention/promotion) on a set of predictors that are correlated with receipt of treatment and the outcome variables. Treatment and control groups members are then paired with similar values of the estimated propensity scores. One advantage of propensity score matching is that it avoids fitting a parametric model to the relationship between the confounding variables (covariates) and the outcome. Propensity score matching was used rather than propensity score stratification because of the size of the study sample.

The following procedures were conducted for the propensity score analysis. First, predictors of the “treatment” (grade retention) were identified. Based on the literature, predictors of grade retention include a child’s demographic and psychological characteristics, family characteristics, and academic achievement. Many of these factors predict educational attainment and labor market outcomes. Available predictors were selected as confounding covariates to create the propensity score. The propensity score specification included demographic characteristics (race/ethnicity, gender, maternal education, free lunch eligibility, single parent status, teen parent status, family size, public aid receipt, and status of child welfare history by child’s age 4), CPC program participation (preschool program participation and school-age program participation), early scholastic abilities (ITBS word analysis in kindergarten, ITBS reading score at first grade, reading grade rated by teacher at first grade), and classroom adjustment at first grade. The covariates used in the present study were based on the common practice and approaches in other retention studies (Hong & Raudenbush, 2005; Hong & Yu, 2007, 2008).

Second, the predictors were used to estimate each study member’s propensity score based on logistic regression analysis. Third, the propensity scores were used to match treated (retained students) to non-treated participants (promoted students) through the kernel matching method. Kernel matching algorithms enable one-to-many matching by calculating the weighted average of the outcome variable for all non-treated participants. This weighted average is then compared to the outcome for the treated group. The mean difference on outcomes can then be compared between the treated and non-treated. The difference is an estimate of the treatment effect for the treated subjects. Although various matching methods are available, the results are usually very similar across approaches. Nearest-neighbor matching was also estimated and the results were similar. Only findings from kernel matching were reported.

Finally, standard errors were estimated using bootstrap methods with 1000 replications. Analyses were conducted through STATA 10.0 (StataCorp, 2007). For more information on propensity score matching, see Dehejia & Wahba, (1999, 2002), Rosenbaum & Rubin (1983, 1984), and Rubin (1997, 2001).

Results

In 2004, 55% of all 20–24 years olds had at least some college experience whereas 43% of Black 20–24 year olds had such educational experience (U.S. Census Bureau, 2005). Educational attainment at age 24 in the CLS study sample was lower than the national average. Thirty-seven percent of the study sample attended either a 2-year or 4-year college by August 2004 (age 24). By January 2004 (age 24), 26% of the study sample reported TANF participation, 53.2% of the study sample reported food stamps participation, and 46.9% of the study sample participated in Medicaid. About 60% of the study sample participated in some public assistance programs.

Table 3 presents the overall and unadjusted rates of outcomes by groups. The retention group had lower rates of college attendance than the promotion group (p < .01). Although the retention group had higher rates of participation in public assistance programs, the differences between the groups were not statistically significant except for any public assistance programs (p < .01). See Appendix 1 for the unadjusted rates of outcomes by early and late retention groups.

Table 3.

Unadjusted Rates of Outcomes by Groups

| Outcomes | N | Study sample | Retention (grades 1–8) | Promotion | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| College Attendance | n=348 | n=1,019 | |||

| 2- or 4-year college attendance, % | 1,367 | 37.0 | 17.2 | 43.8 | .000 |

| 2-year college attendance, % | 1,175 | 26.7 | 12.7 | 32.2 | .000 |

| 4-year college attendance, % | 1,059 | 18.7 | 5.6 | 24.0 | .000 |

| Public Assistance Programs | n=344 | n=966 | |||

| TANF, % | 1,310 | 26.0 | 27.0 | 25.7 | .617 |

| Food Stamps, % | 1,310 | 53.2 | 57.6 | 51.7 | .068 |

| Medicaid, % | 1,310 | 46.9 | 49.4 | 46.0 | .285 |

| Any public assistance, % | 1,310 | 60.2 | 66.0 | 58.2 | .012 |

Note. Sample sizes for retention and promotion groups are 330 and 845 for 2-year college attendance, and 305 and 754 for 4-year college attendance.

Marginal Effects

The differences between the retention (grades 1–8) and promotion groups were examined after taking into account covariates (sociodemographic factors, CPC program participation, and early scholastic skills). Table 4 shows the marginal effects and coefficients from probit regression analyses. There were significant differences between the retention and promotion groups in all three measures of college attendance. Relative to the promotion group, the retention group had lower rates of college attendance (19.9% vs. 40.6%, marginal effect = −19.4%, p < .01), 2-year college attendance (13.7% vs. 29.9%, marginal effect = −16.2%, p < .01), and 4-year college attendance (7.2% vs. 17.4%, marginal effect = −10.2%, p < .01).

Table 4.

Marginal Effects and Coefficients from Regression

| Adjusted rate / mean | Retention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Ever retained (1–8) | Promotion | Coefficients (Std. Err.) | Marginal effects | P -value |

| College Attendance (N=1,367) | n=348 | n=1,019 | |||

| 2- or 4-year college attendance, % | 19.9 | 40.6 | −.564 (.100) | −19.4% | .000 |

| 2-year college attendance, % | 13.7 | 29.9 | −.565 (.111) | −16.2% | .000 |

| 4-year college attendance, % | 7.2 | 17.4 | −.527 (.146) | −10.2% | .000 |

| Public Assistance Programs (N=1,310) | n=344 | n=966 | |||

| TANF, % | 22.4 | 18.9 | .124 (.109) | 3.5% | .254 |

| Food Stamps, % | 58.3 | 51.8 | .162 (.097) | 6.5% | .094 |

| Medicaid, % | 48.4 | 44.7 | .093 (.099) | 3.7% | .351 |

| Any public assistance, % | 67.0 | 60.4 | .176 (.098) | 6.6% | .073 |

Note.

The marginal effects are shown in percentage change for dichotomous outcomes. Results are adjusted for covariates: sociodemographic factors, CPC program participation, and early scholastic abilities, as listed in the measures section.

Sample sizes for retention and promotion groups are 330 and 845 for 2-year college attendance, and 305 and 754 for 4-year college attendance.

A marginal effect denotes the percentage change in the outcome associated with being retained (value of 1 versus 0, being promoted). For example, the marginal effect of ever retained from first grade to eighth grade on college attendance was −19.4%, which indicates that students who were retained had a rate of college attendance that was19.4 percentage points lower than that students who were continuously promoted. Although the retention group had higher rates of public aid recipient, the differences between the retention and promotion groups were not statistically significant after controlling for covariates (sociodemographic factors, CPC participation, and early cognitive abilities). The marginal effects ranged from 3.5% to 6.6%.

Controlling for covariates, the timing of retention (early versus late retention) also was examined. Table 5 shows the marginal effects and coefficients from probit regression analyses for early retention and late retention. The reference group was the promotion group.

Table 5.

Marginal Effects and Coefficients from Regression

| Adjusted rate / mean | Early retention (1–3) | Late retention (4–8) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Early retention (1–3) | Late retention (4–8) | Promotion | Marginal effects (p-value) | Marginal effects (p-value) |

| College Attendance (N=1,343) | (n=233) | (n=91) | (n=1,019) | ||

| 2- or 4-year college attendance, % | 29.2 | 7.7 | 40.6 | −11.4% (.006) | −32.9% (.000) |

| 2-year college attendance, % | 18.6 | 7.0 | 29.9 | −11.3% (.004) | −22.9% (.000) |

| 4-year college attendance, % | 11.7 | 1.0 | 17.4 | −5.7% (.126) | −16.4% (.001) |

| Public Assistance Programs (N=1,288) | (n=233) | (n=89) | (n=966) | ||

| TANF, % | 24.7 | 17.8 | 18.8 | 5.9% (.107) | −1.0% (.839) |

| Food Stamps, % | 60.2 | 54.0 | 51.6 | 8.6% (.052) | 2.4% (.693) |

| Medicaid, % | 48.7 | 45.7 | 44.8 | 3.9% (.392) | 0.9% (.881) |

| Any public assistance, % | 67.0 | 66.5 | 60.3 | 6.7% (.119) | 6.2% (.282) |

Note. Reference group is the promotion group. The marginal effects are shown in percentage change for dichotomous outcomes. Results are adjusted for covariates: sociodemographic factors, CPC program participation, and early scholastic abilities, as listed in the measures section. Participants retained in both early and late were excluded from the analyses: 24 for college measures and 22 for public assistance measures. Sample sizes for early, late retention, and promotion groups are 215, 91, and 845 for 2-year college attendance, and 195, 86, and 754 for 4-year college attendance.

With the exception of early retention and 4-year college attendance, both early and late retention were consistently associated with lower rates of college attendance (p < .05). The late retention (grades 4 to 8) group had the lowest rates of college attendance among the three groups, and had larger marginal effects on college attendance than the early retention group. For example, the marginal effect of late retention on 2-year college attendance was −22.9% while it was −11.3% for early retention. The marginal effect of late retention on college attendance was −32.9% while it was −11.4% for early retention.

For public aid receipt, neither early retention nor late retention was significantly associated with any of the outcomes measures. The early retention group, however, had consistently higher rates of public aid receipt than the late retention group.

Propensity Score Matching

Sample sizes of propensity score matching varied based on the outcomes and the retention groups (treatment groups) that were matched. Table 6 presents the treatment effects of retention (from 1st grade to 8th grade). There were significant differences (p < .05) between the retention and promotion groups for all three measures of college attendance. The retention group (treatment group) had lower rates of 2-year college attendance, 4-year college attendance, and any college attendance than the promotion group. The retention group had higher rates of participation in public assistance programs, but the differences were not statistically significant. Findings from propensity score matching were consistent with the regression findings reported in previous section, although the mean differences between the retention and promotion groups were smaller based on propensity score matching relative to the ones from probit regression analysis.

Table 6.

Treatment effects of retention (1–8) on the retention (treated) groups

| Outcomes | Difference | S.E. | p-value | Any retention | Promotion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| College Attendance | n=342 | n=1,011 | |||

| 2- or 4-year college | −.1298 | .0319 | .000 | .1725 | .3023 |

| 2-year college1 | −.1071 | .0335 | .001 | .1265 | .2336 |

| 4-year college1 | −.0682 | .0233 | .003 | .0567 | .1248 |

| Public Assistance | n=339 | n=958 | |||

| TANF | .0460 | .0373 | .218 | .2743 | .2284 |

| Food Stamps | .0609 | .0434 | .161 | .5693 | .5085 |

| Medicaid | .0418 | .0414 | .313 | .4926 | .4508 |

| Any public assistance | .0739 | .0415 | .075 | .6549 | .5810 |

Note.

Sample sizes for retention and promotion groups are 324 and 843 for 2-year college attendance, and 300 and 747 for 4-year college attendance, respectively.

Table 7 presents the treatment effects of early (grades 1–3) and late (grades 4–8) retention on the outcomes. Three comparisons between groups were examined: 1) early retention (treatment) versus promotion, 2) late retention (treatment) versus promotion, and 3) late retention (treatment) versus early retention. The first two comparisons showed the treatment effects of early and late retention on the outcomes separately, as they were compared with the promotion group independently. The third comparison showed the treatment effect of late retention on the outcomes compared with participants who received early retention. The various comparisons provide information on the treatment effects of early and late retention when compared with different comparison groups.

Table 7.

Treatment effects of early (1–3) and late (4–8) retention on the retention (treated) groups

| Outcomes | Difference | S.E. | p-value | Treatment (Early) | Comp. (Prom.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| College Attendance | n=210 | n=1,006 | |||

| 2- or 4-year college | −.0711 | .0427 | .096 | .2190 | .2902 |

| n=195 | n=837 | ||||

| 2-year college | −.0605 | .0413 | .142 | .1590 | .2195 |

| n=176 | n=741 | ||||

| 4-year college | −.0522 | .0303 | .085 | .0682 | .1204 |

| Public Assistance | n=211 | n=954 | |||

| TANF | .0763 | .0434 | .079 | .2938 | .2176 |

| Food Stamps | .0895 | .0533 | .093 | .6066 | .5172 |

| Medicaid | .0536 | .0539 | .320 | .5071 | .4535 |

| Any public assistance | .0831 | .0506 | .101 | .6730 | .5899 |

| Treatment (Late) | Comp. (Prom.) | ||||

| College Attendance | n=86 | n=987 | |||

| 2- or 4-year college | −.2722 | .0364 | .000 | .0698 | .3420 |

| n=86 | N=825 | ||||

| 2-year college | −.1878 | .0343 | .000 | .0698 | .2576 |

| n=80 | n=734 | ||||

| 4-year college | −.1578 | .0243 | .000 | .0125 | .1703 |

| Public Assistance | n=84 | n=937 | |||

| TANF | −.0049 | .0463 | .916 | .1905 | .1953 |

| Food Stamps | .0464 | .0601 | .440 | .5000 | .4536 |

| Medicaid | .0029 | .0580 | .960 | .3810 | .3780 |

| Any public assistance | .0719 | .0589 | .222 | .5952 | .5234 |

| Treatment (Late retention) | Comp. (Early retention) | ||||

| College Attendance | n=86 | n=160 | |||

| 2- or 4-year college | −.1659 | .0640 | .010 | .0698 | .2357 |

| n=86 | n=147 | ||||

| 2-year college | −.0650 | .0561 | .247 | .0698 | .1348 |

| n=81 | n=137 | ||||

| 4-year college | −.1138 | .0505 | .024 | .0124 | .1261 |

| Public Assistance | n=84 | n=163 | |||

| TANF | −.0070 | .0673 | .917 | .1905 | .1975 |

| Food Stamps | −.0779 | .0791 | .325 | .5119 | .5898 |

| Medicaid | −.0206 | .0777 | .791 | .3929 | .3723 |

| Any public assistance | −.0326 | .0799 | .683 | .6071 | .6398 |

Although the early retention group had lower rates of college attendance, and higher rates of participation in public assistance programs, the differences between groups were not statistically significant. The late retention group had significantly lower rates of college attendance (p < .01) than the promotion group. There was no significant difference in participation in public assistant programs between late retention and the promotion groups.

Finally, the late retention group had significantly lower rates of 4-year college attendance and any college attendance than the early retention group (p < .05). The difference between early and late retention groups in 2-year college attendance was not significant, although the late retention group had a lower rate of 2-year college attendance. There was no significant difference in public aid receipt between late retention and early retention groups.

Additional Analysis-Mediation of Retention Effects

To further explore the relations between grade retention and college attendance, additional analyses were conducted to investigate the factors that might mediate the demonstrated links between grade retention and college attendance. Baron and Kenny’s (1986) approach was used. Two potential mediators were examined: ITBS reading score at age 14 (8th grade) and school dropout by age 19. To test for mediation, 3 regression equations were estimated: 1) regress the mediators (ITBS reading scores at age 14 and dropout by age 19) on the independent variable (grade retention); 2) regress the dependent variable (college attendance) on the independent variable (grade retention); and 3) regress the dependent variable (college attendance) on both the independent variable (grade retention) and on the mediator (ITBS reading scores at age 14 and dropout by age 19). To establish mediation, the following conditions must hold: 1) the independent variable (grade retention) must be significantly associated with the mediator (ITBS reading scores at age 14 and dropout by age 19) in the first equation; 2) the independent variable (grade retention) much be significantly associated with the dependent variable (college attendance) in the second equation; and 3) the mediator (ITBS reading scores at age 14 and dropout by age 19) must be significantly associated with the dependent variable (college attendance) in the third equation. If these conditions all hold in the predicted direction, the effect of the independent variable (grade retention) on the dependent variable (college attendance) must be less in the third equation than in the second because the mediators are taking account of in the third equation.

In the first equation, the negative association between retention and age 14 achievement and the positive association between retention and dropout were found significant in previous studies using the CLS dataset (McCoy & Reynolds, 1999; Temple et al., 2004). They were not re-tested in the present study. In addition, both ITBS reading score at age 14 and dropout by age 19 were significantly correlated with retention measures and the 3 measures of college attendance at .01 level. In the second equation, findings in the previous section indicate significant associations between retention and college attendance. In the third equation, separate models were estimated for age 14 achievement and dropout by age 19.

For models including age 14 achievement, findings show that age 14 achievement was significantly associated with all 3 measures of college attendance (p < .01), and retention remained significantly associated with 2 measures of college attendance: 2-year college and any college attendance (p < .01), but it was no longer significantly associated with 4-year college attendance. Age 14 achievement mediated the relation between retention and 4-year college attendance. As for early and late retention, late retention remained significantly associated with all 3 measures of college attendance (p < .01). However, early retention was no longer significantly associated with any college attendance and 2-year college attendance. Age 14 achievement mediated the relations between early retention (grades 1–3), and any college attendance and 2-year college attendance. Similar patterns were found in the models including dropout by age 19 except the relation between early retention and 2-year college attendance. Early retention remained significantly associated with 2-year college attendance. See Appendix 2 for the marginal effects and p-values from regression analyses.

Discussion

Findings indicate that grade retention is significantly associated with lower rates of participation in postsecondary education above and beyond the effects of family demographics and early school achievement. However, grade retention is not significantly associated with public aid receipt. As for the timing of retention, both early retention and late retention are significantly associated with lower rates of college attendance. Late retention has larger marginal effects on postsecondary education than early retention. Findings from both regression and propensity score matching are consistent.

Grade Retention and Postsecondary Education

Findings on the negative relations between grade retention and participation in postsecondary education are consistent with the Fine and Davis (2003). Retained students are less likely to attend college than students who have never been retained. It is crucial to understand the relation between grade retention and postsecondary education attendance, because postsecondary education comes with advantages and benefits over the life span. When retained students are less likely to attend college relative to students who have never retained, it implies that retained students have less opportunity to profit from the positive benefits of postsecondary education. Such a relation would more than neutralize the academic gains from retention.

Earning a college degree is associated with higher earnings and lower rates of unemployment than a high school diploma (U.S. Department of Labor, 1999). Some college experience is also associated with higher earnings than a high school diploma only (Hecker, 1998). The negative relation between grade retention and college attendance might be explained through the connection between retention and academic achievement or between retention and dropout. Because academic achievement and dropout are highly correlated with each other, only one, dropout, is discussed here. The relation between grade retention and school dropout is reported in many studies (Hauser, 2001; Jimerson, 1999; Jimerson, Anderson et al., 2002; Kaufman & Bradby, 1992; Rumberger & Larson, 1998; Temple et al., 2004). In 2004, 21.4% of youth ages 16–19 who were ever retained dropped out of school (U.S. Department of Education, 2006). Dropouts are less likely to attend college. Even if some dropouts are qualified to apply for college after they received a General Education Development (GED) credential, GED recipients have a lower rate of participation in postsecondary education than high school graduates (Murnane, Willett, & Boudett, 1997; Murnane, Willett, & Tyler, 2000). Some scholars argue that retained students are a selected group exhibiting poor academic performance before being retained, and thus it is not surprising they are more likely to drop out, and less likely to attend college. The potential mediation effect of dropout on retention and college attendance was tested in the additional analyses.

Findings indicate that grade retention remains significantly associated with college attendance negatively after either age 14 (8th grade) achievement or dropout by age 19 was entered into the model. The coefficient of retention on any college attendance dropped from −.5635 to −.3649 after age 14 achievement was added into the model, which was 35% reduction of the coefficient. However, retention remained significantly associated with any college attendance. Similar pattern occurred when dropout was entered into the model. When dropout by age 19 was added into the model, coefficient of retention on any college attendance dropped from −.5635 to −.4045, a 28% reduction in the estimated effect. Although academic achievement and dropout explained part of the association between grade retention and college attendance, they cannot explain the association fully. Thus, the link between grade retention and postsecondary education is complex and goes beyond traditional explanations of academic failure and selection bias.

Two explanations are possible. First, the experience of grade retention might have negative influence on students’ socio-emotional adjustment. Recent studies found that non-cognitive skills, such as effective social interactions, may have the same or stronger predictive power as cognitive skills on college attendance (Heckman & Rubinstein, 2001; Heckman, Stixrud & Urzua, 2006; Ou & Reynolds, 2009). Students who repeated a grade did not get moved on to next grade as their peers. As a result, they would have to make friends with younger students, which may adversely affect their self-esteem, willingness to interact with classmates, and school commitment thereby reducing the potential to pursue higher education.

The second explanation is that school mobility may function as another mediator of the relation between grade retention and postsecondary education. School mobility has been found to be significantly associated with lower educational attainment (Ou, 2005; Ou & Reynolds, 2008). In addition, the retention groups have higher numbers of school moves than the promotion group. It is likely that the experience of grade retention might be associated with a higher rate of school mobility, an indicator of discontinuity in learning, leading to lower rates of college attendance. This mediational process may be independent of those associated with academic achievement and school dropout. The paths from grade retention and postsecondary education warrant further research.

Timing of Retention

Although both early and late retention groups had lower rates of college attendance than the promotion group, the marginal effects of later retention were twice as large as early retention. Findings are consistent with previous studies: late retention is associated with much higher rates of dropout and lower rates of college attendance than is early retention (Fine & Davis, 2003; Roderick, 1994; Temple et al., 2004). In addition, Pomplui (1988) found that the positive effects of retention decrease as students are retained in higher grades. Although an earlier study using CLS data found that the effects of early retention were similar to those of late retention on age-14 reading and math achievement (McCoy & Reynolds, 1999), another study using the same data found that late retention is associated with higher rates of dropout than early retention (Temple et al., 2004). Thus, retention appears to have long-term detrimental effects which are not evident in the first few years after retention.

The different magnitude of associations between early and late retention on postsecondary education might be due to the fact that late retention has a stronger connection with high school dropout than early retention. Findings from another study using the CLS data (Ou & Reynolds, 2008) showed that among many family and school-related influences, late retention was significantly associated with fewer years of completed education and a lower rate of high school completion at age 20. However, early retention was not significantly associated with the outcomes above and beyond a comprehensive set of predictors.

The strong association between late retention and school dropout might be due to the possibility that students in late elementary grades may be more psychologically sensitive to being over-age for grade, which results in declines in school engagement and attendance and ending in dropout. Although recent studies found that kindergarten and second grade retention are not significantly associated with children’s social-emotional development (Bonvin, Bless & Schuepbach, 2008; Hong & Yu, 2008), the effects of later retention on psychological development has not been fully investigated. Grade retention is rated by students as one of the most stressful life events and the relative rank is higher as students get older (Anderson et al., 2005), which is suggestive of the detrimental impact on socio-emotional development later in the schooling process.

Findings from the present study indicate that grade retention is not significantly associated with public aid receipt, although the direction of influence was as expected. This result contrasts with Royce et al., (1983) who found that retained students were more likely than promoted students to be incarcerated and to receive public assistance. Receipt of public aid was examined as one of many adult outcomes, however. Participation in public assistance programs is expected to be associated with unemployment. The sample in the current study was at-risk due to economical disadvantage. Participants had much lower rates of college attendance than the general population. Although it is likely most of the participants are in the labor force, their employment status is unclear. In addition, about 30% of the female participants had first births before age 18, which increases the rate of participation in public assistance. It is likely that participation in public assistance programs is a more complex process than college attendance and predictors such as grade retention may vary by gender and family socioeconomic status. In addition to these and other moderators, future studies are warranted that assess more direct measures of economic well-being such as employment status, income, and occupational prestige.

Conclusion

Limitations

Four limitations of the study restrict inferences. First, the estimated effects of grade retention were based on regression-adjusted scores within a prospective longitudinal design. Although propensity score matching increases the reliability of the findings, study participants were not randomly assigned to groups. Consequently, the predictive results should be interpreted cautiously. Second, the focus of the present study was to examine the association between grade retention and adult outcomes. Therefore, only a limited set of covariates were included in the analysis. For example, sociodemographic factors, such as maternal education, were used as covariates to control differences in early environments. Some factors, such as problem behaviors, socio-emotional adjustment, and school factors, might be associated with retention and outcomes simultaneously (Jimerson, Fergusion, et al., 2002). However, these factors were not included in the present study primarily because most of the retention decisions were based on children’s academic performance. In addition, the focus was to examine the effect of retention instead of retention along with other factors. Socio-emotional factors and school factors (such as school mobility) deserve investigation as mediators of the effects of retention. Third, in order to better distinguish between early and late retention, students retained both early and late (n=24) were excluded from the analyses of timing of retention. This might underestimate the effect of early retention, because late retention might be associated with early retention. Finally, the CLS follows a primarily low-income sample of almost all African-American children who grew up in high-poverty neighborhoods in Chicago. As a result, the generalizability of findings is limited to children with these attributes in large urban contexts.

Implications

There are two major implications of the study findings. The first is the negative association between grade retention and college attendance. Findings from the present study add to the growing research indicating that grade retention is associated with negative educational outcomes. As noted in the introduction, the context of retention in this study is before the “ending social promotion” or “high-stakes testing” movement. During this earlier time, retention was based on multiple criteria, and was considered as a last resort. Therefore, students were probably less likely to be retained than the students under the high-stakes testing policy. Although students retained under the high-stakes testing policy might receive more systematic remedial education than during the time frame of the present study, recent studies under the high-stakes testing policy have showed that positive gains in academic performance disappeared 2 years after the initial retention. It seems that retention has limited benefit under either of the contexts. Rather than benefitting students, the school practice of retention links to lower rates of college attendance. Many studies indicate that grade retention is not only ineffective as an intervention, but it also increases students’ risk of other negative outcomes. The implications of retention policy are cause for concern. Moreover, retention is not a low-cost intervention (Eide & Goldhaber, 2005). In 1998, the end of high school for study participants, the cost of 1 additional year of instruction in the Chicago Public School was $7,211 (Reynolds, Temple, Robertson & Mann, 2002). Alternative policies and practices should be considered that are more likely to promote children’s academic performance and life-course development.

One example of alternative approaches to promote children’s academic performance instead of grade retention is early childhood education programs. Early childhood education, one type of preventive intervention, has been found to promote scholastic and social competence (Ramey & Ramey, 1998; Reynolds, et al., 2001, 2007; Weissberg & Greenberg, 1998). Studies show that high-quality early education programs, such as Chicago Child-Parent Centers (CPC) program, can have a lasting impact on educational attainment and other developmental outcomes for economically disadvantaged children. For instance, the CPC preschool program was found to provide a return to society of $7.14 per dollar invested by increasing economic well-being and tax revenues, and by reducing public expenditures for remedial education, criminal justice treatment, and crime victims (Reynolds et al., 2002). Prevention and cost-efficient investments have become higher priorities in education and social policy. Other than early intervention programs, involvement in afterschool activities during high school have been found to reduce the risk of dropping out for retained students (Randolph, Fraser, & Orthner, 2004). Schools should consider developing programs that reinforce engagement and school commitment to help reduce the risk of dropping out.

The second implication concerns the potential mediating pathway from grade retention to college attendance. The negative association between grade retention and college attendance can be explained partially through the link between grade retention and academic achievement or between grade retention and dropout. Such mediation indicates that retention can be connected to long-term outcomes through complex processes. It is important to be aware that grade retention not only can be associated with lower academic achievement but disengagement from the school process that is predictive of post high school well-being. Further investigation of other potential unintended negative effects of retention is needed as is a more complete understanding of the processes that lead to long-term detrimental effects.

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this paper was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD034294). Please direct correspondence to: Suh-Ruu Ou, 204 Child Development, Institute of Child Development, 51 East River Road, Minneapolis, MN 55455 or sou@umn.edu.

Biographies

Suh-Ruu Ou, Ph.D., is a Research Associate at the Institute of Child Development at the University of Minnesota - Twin cities. She received her Ph.D. in Social Welfare from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her areas of specialization are program evaluation, research methodology, educational attainment, and the effects of early childhood intervention. Her publications include work on early intervention and educational attainment. Currently, her research focuses on school dropouts, GED recipients, grade retention, and postsecondary education. sou@umn.edu.

Arthur J. Reynolds is a professor in Institute of Child Development at the University of Minnesota, and the director of the Chicago Longitudinal Study (CLS). He received his Ph.D. in Public Policy Analysis from the University of Illinois at Chicago. He is interested more in child development and social policy, evaluation research, and prevention science. His publications include Success in Early Intervention: The Child-Parent Centers (2000), Early Childhood Programs for a New Century (2003), as well as a cost-benefit analysis of the Child-Parent Center Program.

Appendix 1. Unadjusted Rates of Outcomes by Groups

| Outcomes | Study sample | Early Retention | Late Retention | Retained both early and late | Promotion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| College Attendance | N=1,367 | n=233 | n=91 | n=24 | n=1,019 |

| 2- or 4-year college attendance, % | 37.0 | 23.2* | 6.6* | 0.0* | 43.8 |

| 2-year college attendance, %1 | 26.7 | 16.7* | 6.6* | 0.0* | 32.2 |

| 4-year college attendance, %1 | 18.7 | 8.2* | 1.2* | 0.0* | 24.0 |

| Public Assistance Programs | N=1,310 | n=233 | n=89 | n=23 | n=966 |

| TANF, % | 27.1 | 31.0 | 20.3 | 28.6 | 26.7 |

| Food stamps, % | 54.6 | 61.1 | 53.2 | 61.9 | 53.0 |

| Medicaid, % | 47.9 | 50.5 | 41.8 | 71.4 | 47.3 |

| Any public assistance, % | 61.5 | 68.1 | 63.3 | 76.2 | 59.5 |

Note. Retention groups were compared with the promotion group.

p < .05.

Sample sizes for early, late retention, and promotion groups are 215, 91, and 845 for 2-year college attendance, and 195, 86, and 754 for 4-year college attendance.

Appendix 2. Marginal Effects from Additional Analyses

| Retention (1–8) | Early retention (1–3) | Late retention (4–8) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| College Attendance | Marginal effects | P -value | Marginal effects | P -value | Marginal effects | P -value |

| Additional variable: Age 14 Achievement (Iowa Test Basic Skills reading score) | ||||||

| 2- or 4-year college attendance, % | −12.9% | .001 | −4.2% | .343 | −28.7% | .000 |

| 2-year college attendance, % | −13.0% | .000 | −7.7% | .064 | −20.7% | .000 |

| 4-year college attendance, % | −3.7% | .196 | 1.8% | .651 | −11.4% | .008 |

| Additional variable: Dropout by Age 19 | ||||||

| 2- or 4-year college attendance, % | −13.8% | .000 | −6.5% | .141 | −28.0% | .000 |

| 2-year college attendance, % | −12.7% | .000 | −8.4% | .034 | −19.4% | .000 |

| 4-year college attendance, % | −3.0% | .102 | 0.3% | .897 | −6.4% | .005 |

Note. Reference group is the promoted group. The marginal effects were shown in percentage change for dichotomous outcomes. Results are adjusted for covariates: sociodemographic factors, CPC program participation, and early scholastic abilities.

References

- Alexander KL, Entwisle DR & Dauber SL (2003). On the success of failure: a reassessment of the effects of retention in the primary grades (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge university press. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander KL, Entwisle DR, Dauber SL & Kabbani N (2004). Dropout in relation to grade retention: An accounting from the Beginning School Study. In Walberg HJ, Reynolds AJ, & Wang MC (Eds), Can unlike students learn together? Grade retention, tracking and grouping (pp. 5–34). Greenwich, CT: Information Age. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander KL, Entwisle DR & Horsey CS (1999, November). Grade retention, social promotion and “third way” alternatives. Paper presented at the National Invitational Conference on Early Childhood Learning: Programs for a new age. Alexandria, VA. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander KL, Entwisle DR, & Kabbani N (2001). The dropout process in life course perspective: Early risk factors at home and school. Teachers College Record, 103(5), 760–822. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GE, Jimerson SR & Whipple AD (2005). Student ratings of stressful experiences at home and school: Loss of a parent and grade retention as superlative stressors. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 21(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe-Frankenberger M Bocian KM, MacMillan DL & Gresham FM (2004). Sorting second-grade students: Differentiating those retained from those promoted. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(2), 204–215. [Google Scholar]

- Bonvin P, Bless G & Schuepbach M (2008). Grade retention: Decision-making and effects on learning as well as social and emotional development. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 19(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chicago Public Schools. (1985). Elementary school--Criteria for promotion. Chicago: Author. [Google Scholar]

- CLS, Chicago Longitudinal Study. (2005). A study of children in the Chicago public schools: User’s guide (Version 7). Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin. [Google Scholar]

- Dehejia RH & Wahba S (1999). Causal effects in non-experimental studies: Re-evaluating the evaluation of training programs. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 94(448), 1053–1062. [Google Scholar]

- Dehejia RH & Wahba S (2002). Propensity score-matching methods for nonexperimental causal studies. Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(1), 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Eide ER & Showalter MH (2001). The effect of grade retention on educational and labor market outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 20, 563–576. [Google Scholar]

- Eide ER & Goldhaber DD (2005). Grade retention: What are the costs and benefits? Journal of Education Finance, 31(2), 195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Ensminger ME & Slusarcick AL (1992). Paths to high school graduation or dropout: A longitudinal study of a first-grade cohort. Sociology of education, 65(2): 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Fine JG & Davis JM (2003). Grade retention and enrollment in post-secondary education. Journal of school psychology, 41, 401–411. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson DC, Fink CM & Graham N (1994). Grade retention and problem behavior. American Educational Research Journal, 31(4), 761–784. [Google Scholar]

- Greene JP & Winters MA (2004). An evaluation of Florida’s program to end social promotion. Education working paper, No. 7 New York, NY: Center for Civic Innovation at the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research. [Google Scholar]

- Greene JP & Winters MA (2006). Getting farther ahead by staying behind: A second-year evaluation of Florida’s policy to end social promotion. Civic Report, No. 49 New York, NY: Center for Civic Innovation at the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research. [Google Scholar]

- Greene JP & Winters MA (2007). Revisiting grade retention: An evaluation of Florida’s test-based promotion policy. Education Finance and Policy, 2(4), 319–340. [Google Scholar]

- Guèvremont A, Roos NP Brownell M (2007). Predictors and consequences of grade retention: Examining data from Manitoba, Canada. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 22(1), 50–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser RM (2001). Should We End Social Promotion? Truth and Consequences. In Orfield G & Kornhaber M (Eds.), Raising the standards or raising barriers? Inequality and high stakes testing in public education (pp. 151–178). New York: Century Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Hecker D (1998). Occupations and earnings of workers with some college but no degree. Occupational Outlook Quarterly, 42(2), 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ & Rubinstein Y (2001). The importance of noncognitive skills: Lessons from the GED testing program. American Economic Review, 91(2), 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ, Stixrud J & Urzua S (2006). The effects of cognitive and noncognitive abilities on labor market outcomes and social behavior. Journal of Labor Economics, 24(3), 411–482. [Google Scholar]

- Heubert JP & Hauser RM (1999) (eds). High stakes: Testing for tracking, promotion, and graduation. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes CT (1989). Grade-level retention effects: A meta-analysis of research studies. In Shepard LA & Smith ML (Eds.), Flunking grades: Research and policies on retention (pp.16–33). London: Falmer Press. [Google Scholar]