Abstract

Background

Several articles have recently reported that certain colon microbiota can improve the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. To develop new treatment strategies, including immunotherapy for colorectal cancer (CRC), we evaluated the correlations between subpopulations of tumor-infiltrating immune cells (TIICs) and intestinal microbiota in CRC.

Methods

Fresh surgically resected specimens, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded whole tissue samples, and stool samples were collected. TIICs including Tregs, Th17 cells and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) in the surgically resected specimens were analyzed using flow cytometry. FOXp3, CD8, CD163, and phosphorylated-STAT1-positive TIICs in the whole tissue samples were analyzed using IHC, and intestinal microbiota in the stool samples was analyzed using 16S metagenome sequencing. TIICs subpopulations in the normal mucosa and tumor samples were evaluated, and the correlations between the TIIC subpopulations and intestinal microbiota were analyzed.

Results

FOXp3lowCD45RA+ Tregs were significantly reduced (p = 0.02), FOXp3lowCD45RA− Tregs were significantly increased (p = 0.006), and M1 TAMs were significantly reduced in the tumor samples (p = 0.03). Bacteroides (phylum Bacteroidetes) and Faecalibacterium (phylum Firmicutes) were increased in the patients with high numbers of Tregs and clearly high distribution of FOXp3highCD45RA− Tregs, which are the effector Tregs. Faecalibacterium, Ruminococcaceae, Eubacterium (phylum Firmicutes), and Bacteroides were increased in patients with a high distribution of M1 TAMs.

Conclusions

The findings of the present study indicate that immune responses to tumors are suppressed in the tumor microenvironment of CRC depending on the increment of Tregs and the reduction of M1 TAMs and that intestinal microbiota might be involved in immunosuppression.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00262-019-02433-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Microbiota, Tumor-associated macrophage, Treg

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide [1–3]. Although patients with advanced CRC typically undergo multidisciplinary treatment such as surgical resection combined with chemotherapy, their prognosis remains poor and the development of new treatment strategies is required [4, 5].

Immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors has recently become an important part of cancer treatment [6, 7]. To enhance the effect of immunotherapy, tumor-infiltrating immune cells (TIICs) are regarded as important. The function of TILs is known to be regulated by Tregs, MDSCs and M2 macrophages in the tumor microenvironment because the abundance of these immunosuppressive cells correlates with poor tumor differentiation and/or survival [8–13].

Saito et al. recently reported that FOXp3highCD45RA− Tregs in the tumor microenvironment attenuated immunity in CRC [14]. In the tumor microenvironment, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) have a variety of functions, including tumor-associated angiogenesis, and promote invasion, migration and intravasation of tumor cells, resulting in the suppression of antitumor immune responses [15–17]. TAMs have subsets: one is activated macrophages, called M1 TAMs; and the other is alternatively-activated macrophages, called M2 TAMs. M1 TAMs are involved in the Th1 type responses to pathogens. On the other hand, M2 TAMs, which are differentiated in response to IL-4 and IL-13, are involved in Th2 type responses, including humoral immunity and wound healing [18]. Recent reports have suggested that macrophages in tumors are biased away from the activated M1 TAMs to the alternatively activated M2 TAMs [19], and gene profiling studies on TAMs have supported this shift to M2 from M1 TAMs in the tumor microenvironment [20–22]. We recently reported that obesity-induced M1/M2 TAMs might be involved in obesity-associated tumor growth through the enhancement of cancer cell proliferation [23]. Cell surface markers of human M1 TAMs include CD11c, CD40, CD86, HLA-DR, and TLR-4 [24–26], and several groups have reported CD11c to be a marker of human M1 TAMs [27–29]. On the other hand, cell surface markers of M2 TAMs include CD163, CD204, and CD206 [24–26]. We recently used CD14, CD11c, and CD163 to analyze the phenotype of macrophages in adipose tissue [23].

In the human gut, there are a number of bacteria, consisting of one thousand species and 100 trillion individuals [30], and the role of intestinal microbiota against tumor immune responses is still controversial. Sears et al. recently reported that Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Verrucomicrobia were implicated in response to immunotherapy and that certain bacteria within the intestinal microbiota enhanced clinical responses to checkpoint blockade [31]. For example, it has been reported that bacteria in the genus Fusobacterium are enriched in some CRC patients’ microbiota [32–35], and the gene of the genus Providencia has also been detected in the CRC microenvironment, similar to Fusobacterium [36]. Although Saito et al. suggested that an increment of the number of FOXp3lowCD45RA− Tregs, in which their presence was correlated with Fusobacterium, in the tumor microenvironment could be used to suppress or prevent tumor formation [14], several articles have shown that inflammation caused by Fusobacterium induced tumor formation and/or progression in the tumor microenvironment [32, 37–39].

In the present study, we examined the characteristics of TIICs, including Tregs, Th17 cells, and TAMs, using freshly resected surgical specimens and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded whole tissue samples from patients with CRC. Furthermore, we evaluated the correlations between TIIC subpopulations and intestinal microbiota in CRC.

Materials and methods

Patients

The inclusion criteria were patients who did not have a history of previous CRC and who underwent surgery for CRC at Fukushima Medical University Hospital between April 2017 and March 2018. The exclusion criteria were the preoperative treatment with self-expanding metal stent for obstructive CRC and the tumor diameter of 3 cm or less. Because the physical stimulation by the stent caused local inflammation in the tumor, we required a sufficient amount of TIICs to analyze their characteristics by flow cytometry.

Clinical samples

When the surgical specimens were removed, 1–2 cm3 samples of both the normal mucosa from a distance 5 cm or more from the tumor, and the tumors were immediately collected in 10 ml RPMI with 2% FBS. The samples were minced with scissors into 1 mm3 pieces or smaller, and incubated with collagenase type I and DNase I at 37 °C for 1 h. The samples were then filtered out with metal sieves (150 μm test sieve, TOKYO SCREEN CO., LTD, Tokyo, Japan) and incubated for an additional 1 h under the same conditions. After incubation, lysing buffer was added to hemolyze erythrocytes. Finally, the digested samples were sieved through a Falcon® 100 μm Cell Strainer (Corning, NY, USA) and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min to remove extract stromal vascular fraction. The pellets were then washed and resuspended with PBS for flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

All cells in the small amount of clinical samples were stained with Trypan Blue Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), and were counted by Automated Cell Counter (Thermo Fisher Scientific). We confirmed that the viability of the cells was more than 98% in all samples. A list of the kit and antibodies that were used in the present study are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Tregs were detected using a human Treg Detection Kit, which included FITC-conjugated human CD4 mAb and APC-conjugated human FOXp3 mAb (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), and VioBlue-conjugated human CD45RA Ab (Miltenyi Biotec). The cells were stained according to each manufacturer’s flow cytometry preparation protocol. Briefly, resuspended 106 cells were stained with 10 μl of CD4 mAb and CD45RA mAb. Following fixation and permeabilization with FcR blocking, the samples were stained with 10 μl of FOXp3 mAb for intracellular staining.

Th17 cells were detected using APC-conjugated human CD4 Ab (BD Biosciences, CA, USA), PE-conjugated human IL-17A Ab (BD Biosciences), and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated human IL-17F Ab (BD Biosciences). For the Th17 cell staining, resuspended 106 cells were stained with 20 μl of CD4 mAb. Then, following fixation and permeabilization with FcR blocking, the samples were stained with 20 μl of IL-17A mAb and 5 μl of IL-17F mAb for intracellular staining, according to the manufacturer’s flow cytometry preparation protocol for these antibodies.

TAMs were detected using APC-conjugated human CD14 Ab (BD Biosciences), PE-conjugated human CD11c Ab (BD Biosciences), and FITC-conjugated human CD163 Ab (BD Biosciences). Resuspended 106 cells were stained with 20 μl of CD14 mAb and CD11c mAb, and 5 μl of CD163 mAb for TAMs staining.

All stainings were measured using a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). To analyze the data, at least 106 cells for normal mucosa samples and at least 107 cells for tumor samples were acquired by a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer. The number of events for analysis in each sample is presented in Supplementary Table S2. FACS data were analyzed using FlowJo software, version 10.3.0 (FlowJo, LLC, OR, USA). Regarding the gating to remove non-target cells, we first gated the population of lymphocytes for Tregs and Th17 cells or the population of monocytes for TAMs with forward scatter and side scatter. Following the gate for lymphocytes, a second gate was added to the CD4-positive cells to analyze the Tregs and Th17 cells. Under these two gates, the quadrant was made with CD45RA and FOXp3 for analysis of the Tregs, as well as with IL-17A and IL-17F for analysis of the Th17 cells. Following the gate for monocytes, a second gate was added to the CD14-positive cells to analyze the TAMs. Under these two gates, the quadrant was made with CD11c and CD163 for analysis of the TAMs.

IHC

We used seventeen formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded whole tissue samples of CRC, which were made from patients whose fresh surgically resected samples were analyzed by flow cytometry. Then, 4-μm thick sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated. Endogenous peroxidases were blocked with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol. For the CD8 and FOXp3 staining, antigens were retrieved by autoclave for 5 min in Target Retrieval Solution (Dako/Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) (105 °C, pH9.0). For the CD163 and phosphorylated-STAT1 (p-STAT1) staining, antigens were retrieved by autoclave for 5 min in citrate buffer solution (105 °C, pH6.0). Slides were incubated at 4 °C overnight with the following primary antibodies: CD8 mAb (clone C8/144B; Dako/Agilent Technologies) at 1:100, FOXp3 mAb (clone 236A/E7; abcam, Cambridge, UK) at 1:200, CD163 mAb (clone 10D6; Leica Biosystems, Nussloch, Germany) at 1:1000, and p-STAT1 mAb (clone D3B7; Cell Signaling Technology) at 1:800. The sections were detected by a horseradish peroxidase coupled anti-rabbit or anti-mouse polymer (Dako/Agilent Technologies), and incubated with diaminobenzidine (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan), before counterstaining with Mayer’s Hematoxylin Solution (Wako/Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan). Negative controls were performed with PBS as primary antibody.

IHC analysis was performed by observers who were blinded to the clinical data. For the assessment of IHC, four independent areas at the invasive front region of the tumor were reviewed at a magnification of ×400. CD8, FOXp3, CD163, and p-STAT1 were defined as average of the number of staining TILs or TIICs in four independent areas.

16S metagenome sequencing

Stool samples were collected from the patients and suspended in a solution including guanidine. Genomic DNA from the samples were extracted using a Maxwell RSC Blood DNA kit (Promega Corporation, WI, USA). The 16S rRNA gene V1-2 regions were amplified by PCR using a Veriti Thermal Cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The reaction mixture contained a DNA solution, Prime STAR Max Polymerase (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan), forward primer with an A adapter and barcode, and reverse primer with a P1 adapter. The thermal cycle program was as follows: initial denaturation at 98 °C for 30 s, 20 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 55 °C for 10 s, extension at 72 °C for 5 s, and final cooling at 4 °C. Unnecessary dNTPs and primers were removed from the amplicons by ExoSAP-IT Express PCR Cleanup Reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cleaned amplicons were quantified using Step One Real-Time PCR Systems (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA), and KAPA Library Quantification Kits Ion Torrent/ABI Prism (Kapa Biosystems, MA, USA). The thermal cycle program was as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, and annealing at 60 °C for 45 s. The libraries were adjusted to 10 pM and prepared for the template using an Ion OneTouch2 System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and an Ion PGM Hi-Q View OT2 Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The templates were sequenced by a single-end protocol using an Ion PGM System (Thermo Fisher Scientific), an Ion 318 Chip v2 BC (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and an Ion PGM Hi-Q View Sequencing Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The raw sequence data were filtered to identify target sequences using a Torrent Browser (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the filtered data was exported to a BAM file. The file was then analyzed with an Ion Reporter to identify the presence and percentage of the microbes using databases that Micro SEQ (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and GreenGenes.

Statistical analyses

The Mann–Whitney U test was used to determine the differences in each group regarding proportions of Tregs, Th17 cells, and TAMs between normal mucosa and the tumor samples. Only data with the normal mucosa and tumor samples were used in the present study. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

FOXp3lowCD45RA+ Tregs were reduced and FOXp3lowCD45RA− Tregs were increased in the tumor samples

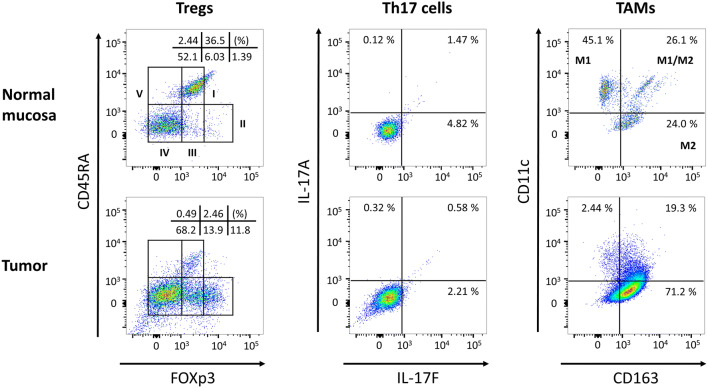

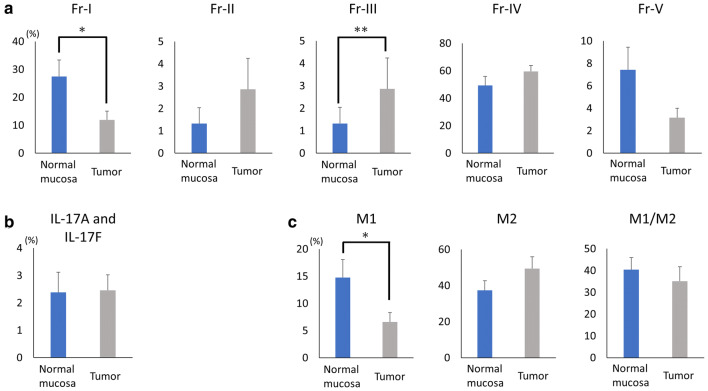

The patient and tumor characteristics are presented in Table 1. CRC stage was confirmed by pathologists at Fukushima Medical University Hospital. A patient with ulcerative colitis, a patient with familial adenomatous polyposis, a patient underwent chemotherapy (four cycles of CAPOX), and a patient underwent preoperative antibiotics treatment were enrolled in the present study (Table 1). We evaluated the prevalence of TIICs, including Tregs, Th-17 cells, and TAMs, between the normal mucosa and the tumor samples taken from patients with CRC. Regarding Tregs, CD4+ TILs were classified into five subpopulations on the basis of FOXp3 and CD45RA expression levels according to a previous report [14]. Representative flow cytometry in a CRC patient (Fig. 1) showed the distribution of Fraction I (FOXp3lowCD45RA+), Fraction II (FOXp3highCD45RA−), Fraction III (FOXp3lowCD45RA−), Fraction IV (FOXp3−CD45RA−) and Fraction V (FOXp3−CD45RA+) between the normal mucosa and the tumor samples. In the summarized data (n = 17), Fraction I Tregs were significantly reduced (p = 0.02) and Fraction III Tregs were significantly increased in the tumor samples (p = 0.006, Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table S3) in comparison to the normal mucosa.

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics of CRC

| No. | Age | Sex | Diagnosis | T | N | M | Stage | Pathology | Preoperative chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy | Preoperative antibiotics treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 63 | M | S | 4b | 0 | 0 | 2 | tub1 | – | PIPC/TAZ, LVFX |

| 2 | 55 | M | R | 4a | 3 | 1 | 4 | tub2 | – | – |

| 3 | 59 | M | R | 3 | 1 | 0 | 3a | tub1 | – | – |

| 4 | 35 | F | R, FAP | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | tub2 | – | – |

| 5 | 70 | M | R | 4a | 3 | 1 | 4 | tub2 | – | – |

| 6 | 57 | M | R, UC | 3 | 3 | 1 | 4 | tub1 | – | – |

| 7 | 66 | F | S | 4a | 0 | 0 | 2 | tub2 | – | – |

| 8 | 62 | F | A | 4a | 0 | 0 | 2 | tub2 | – | – |

| 9 | 59 | M | R | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | tub1 | – | – |

| 10 | 56 | M | R | 4a | 3 | 1 | 4 | tub2 | CAPOX | – |

| 11 | 76 | F | R | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3a | tub1 | – | – |

| 12 | 88 | F | A | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | tub2 | – | – |

| 13 | 67 | M | R | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | tub1 | – | – |

| 14 | 74 | M | S | 4a | 0 | 1 | 4 | tub2 | – | – |

| 15 | 68 | M | A | 4a | 2 | 0 | 3b | muc | – | – |

| 16 | 80 | M | R | 4b | 0 | 0 | 2 | tub2 | – | – |

| 17 | 82 | M | A | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | tub2 | – | – |

A ascending colon cancer, D descending colon cancer, S sigmoid colon cancer, R rectal cancer, FAP familial adenomatous polyposis, UC ulcerative colitis, CAPOX capecitabine (2000 mg/m2/day, internal use on day 1–14)—oxaliplatin (130 mg/m2, intravenous injection on day 1)/every 3 weeks, PIPC piperacillin, TAZ tazobactam, LVFX levofloxacin

Fig. 1.

Representative flow cytometry plots of Tregs, Th17 cells, TAMs in normal mucosa and tumor samples. The upper plots are the results of the normal mucosa and the lower plots are the results of the tumor samples. The two left plots are the results of the Tregs analyzed with FOXp3 and CD45RA. The two middle plots are the results of the Th17 cells analyzed with IL-17F and IL-17A. The two right plots are the results of the TAMs analyzed with CD163 and CD11c. The Tregs were classified into five subpopulations and the TAMs were classified into three subpopulations, as mentioned in the Materials and Methods

Fig. 2.

Summarized data for the distribution of Tregs, Th17 cells, and TAMs. TIICs were evaluated between normal mucosa and tumor samples. Each distribution of Tregs (a), Th17 cells (b), and each distribution of TAMs (c) are presented. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 between normal mucosa and tumor samples

There was no change in Th17 cells between normal mucosa and the tumor samples

We evaluated the prevalence of Th17 cells with IL-17A and IL-17F expression in CD4-positive TILs (Fig. 1). There were no significant differences in the proportion of Th17 cells between the normal mucosa and the tumor samples (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table S4).

M1 TAMs were reduced in the tumor samples

To evaluate the phenotypes of the TAMs, the collected cells from the normal mucosa and the tumor samples were stained with anti-CD14 Ab (a monocyte/macrophage marker), anti-CD11c Ab (a marker of M1 TAMs), and anti-CD163 Ab (a marker of M2 TAMs) for flow cytometry. In accordance with previous studies [23–29, 40], TAMs were classified into three subpopulations in the present study: M1 TAMs (CD14+CD11c+CD163−); M2 TAMs (CD14+CD11c−CD163+); and M1/M2 TAMs (CD14+CD11c+CD163+) (Fig. 1). As a result, the distribution of M1 TAMs was significantly reduced in the tumor samples (p = 0.03, Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table S5) in comparison to the normal mucosa. Although there were no statistically significant differences, the distribution of M2 TAMs tended to increase in the tumor samples compared to the normal mucosa (p = 0.16, Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table S5).

The intestinal microbiota may affect subpopulations of TIICs

In the present study, we analyzed the subpopulations of TIICs using IHC (Supplementary Fig. S1) and intestinal microbiota using 16S metagenome sequencing (Supplementary Fig. S2). We evaluated the frequency of Tregs, CD8 T lymphocytes, and M2 TAMs in the tumor microenvironment using IHC. We used FOXp3 staining to evaluate the Tregs, and CD163 staining to evaluate the M2 TAMs. Since Th1 and Th2 have contrasting roles in cancer development and IFN-γ is a main cytokine in Th1, we evaluated the presence of p-STAT1 expressing TIICs because p-STAT1 is a main molecule of the IFN-γ signaling pathway [41]. Representative IHC stainings with CD8, FOXp3, CD163, and p-STAT1 are presented in Supplementary Figure S1.

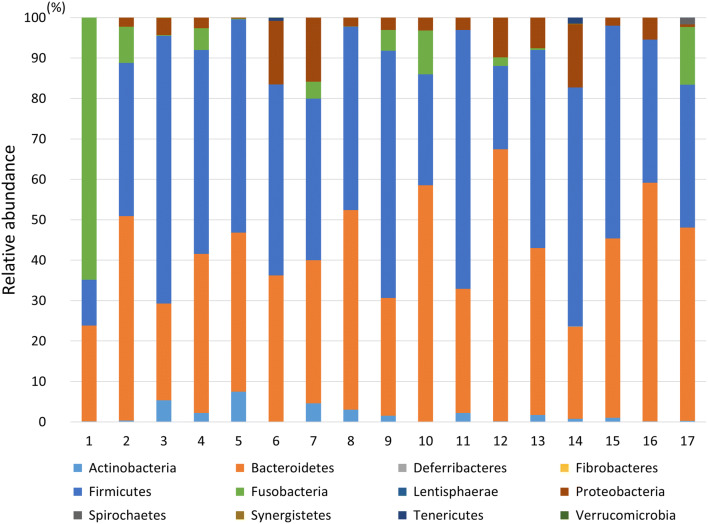

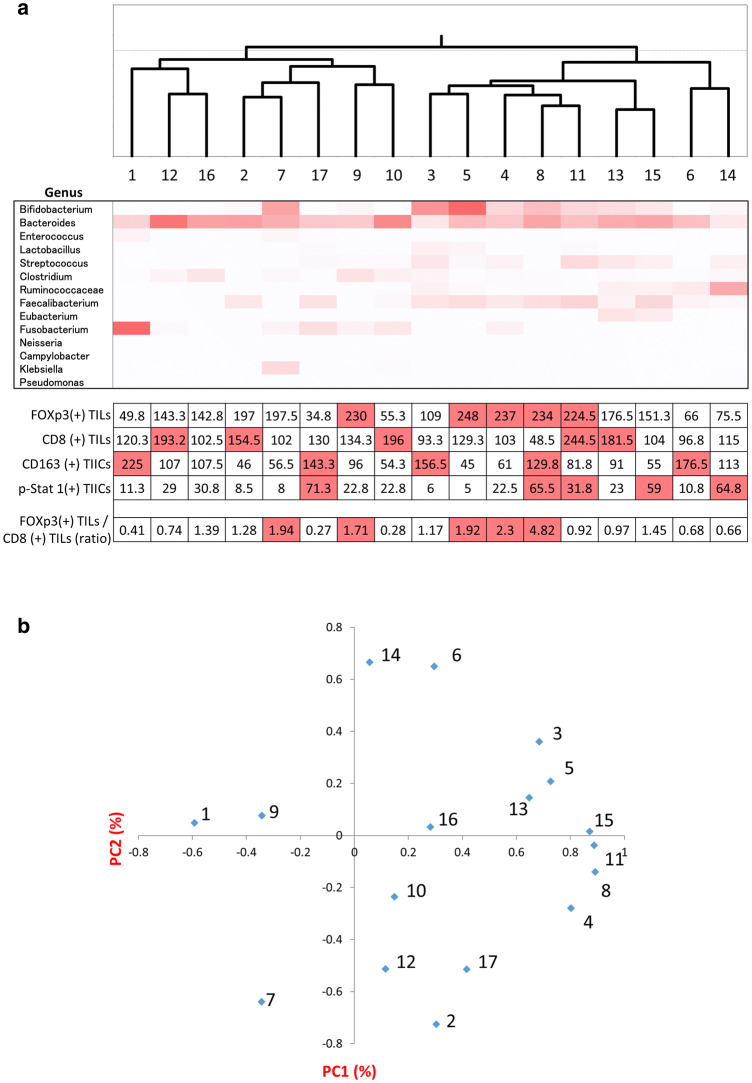

Although intestinal microbiota were analyzed using the relative abundance in phylum level (Fig. 3), there were no significant correlations between the TIIC subpopulations and intestinal microbiota. To analyze the correlation between the subpopulations of TIICs and intestinal microbiota in detail, intestinal microbiome were analyzed using hierarchical clustering analysis based on genus-level classifications, and principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) (Fig. 4a, b). According to the results from both analyses, patients with a clearly high distribution of Fraction II Tregs in their tumor samples, namely patients No. 8 and 11 (Supplementary Table S3), were in the same branch in the hierarchical clustering analysis (Fig. 4a) and in the same area in the PCoA (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, the number of infiltrating Tregs was increased in patients No. 8 and 11 (Fig. 4a). Four out of five patients with a high distribution of M1 TAMs in their tumor samples, namely patients No. 8, 11, 13, and 15 (Supplementary Table S5), were in the same area in the PCoA (Fig. 4b). Bacteroides (phylum Bacteroidetes) and Faecalibacterium (phylum Firmicutes) were increased in patients No. 8 and 11 (Fig. 4a). Ruminococcaceae, Faecalibacterium, Eubacterium (phylum Firmicutes), and Bacteroides were increased in patients No. 8, 11, 13, and 15 (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 3.

Relative abundance of intestinal microbiota in phylum level. We analyzed intestinal microbiota using 16S metagenome sequencing as mentioned in the Materials and Methods. We presented the intestinal microbiota in the phylum level for all patients

Fig. 4.

Analysis of intestinal microbiome. Hierarchical clustering analysis (upper), heatmap based on genus-level classification (middle), and results of IHC (lower) are presented (a). The IHC results present the ratio or the average number of staining TILs or TIICs at four independent areas. The top five patients in each item are highlighted in red (a). Principal coordinates analysis was performed on a genus level (b)

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to have shown that the distribution of Fraction I Tregs are significantly reduced, the distribution of Fraction III Tregs are significantly increased, and the distribution of M1 TAMs are significantly reduced in tumor samples in comparison to normal mucosa in CRC patients. Furthermore, in the present study, the prevalence of Fraction II Tregs in the tumor samples and the number of Tregs in the tumor microenvironment were clearly increased in the CRC patients with Bacteroides and Faecalibacterium, and the distribution of M1 TAMs in the tumor samples was increased in those with Ruminococcaceae, Faecalibacterium, Eubacterium, and Bacteroides.

Saito et al. recently reported that Fraction III Tregs might develop from Fraction I Tregs in the presence of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-12 and TGF-β, produced by tumor invading intestinal bacteria [14]. In the present study, we showed that Fraction I Tregs were significantly decreased and that Fraction III Tregs were significantly increased in the tumor samples in comparison to the normal mucosa (Fig. 2a). Our results, as well as others’, suggest the possibility that Fraction III Tregs develop from Fraction I Tregs by inflammation caused by the tumor microenvironment, resulting in the reduction of Fraction I and the increment of Fraction III Tregs in the tumor. Among several factors within the tumor microenvironment, it is believed that inflammation-related cytokines induced by bacteria or tumor formation play an important role in the regulation of Tregs. For example, it was reported that Fusobacterium nucleatum plays a role in the production of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-12, TGF-α and TGF-β, contributing to the induction of Fraction III Tregs [14]. However, in the present study we could not identify any specific intestinal bacteria strongly related to the increment of Fraction III Tregs in the patients. On the other hand, the prevalence of Fraction II Tregs and the number of Tregs overall in the tumor samples were clearly increased in the patients who had Bacteroides and Faecalibacterium. Sears et al. also reported that Bacteroides, Ruminococci and Roseburia (phylum Firmicutes) are associated with a negative response to immunotherapy and that certain bacteria within the intestinal microbiota enhanced clinical responses to the checkpoint blockade [31]. Although there were no statistically significant differences in the distribution of Fraction II Tregs between the normal mucosa and tumor samples in the present study, the distribution of Fraction II Tregs tended to be increased in the tumor samples (p = 0.11). Since Fraction II Tregs have a highly suppressive immune function [14], the depletion of Fraction II Tregs from the tumor microenvironment would be an effective treatment strategy for CRC.

Although the simultaneous accumulation of M1, M2, and M1/M2 TAMs were observed in CRC [42], their role within remains controversial [43–45]. We showed in the present study that M1 TAMs were significantly reduced (p = 0.03) and that M2 TAMs tended to increase in the tumor samples (p = 0.16) (Fig. 2c). Therefore, we suspect that TAMs are shifted from M1 type TAMs to M2 type TAMs within the tumor microenvironment depending on tumor progression in CRC. Although M1 TAMs in the tumor samples were increased in patients who had Ruminococcaceae, Faecalibacterium, Eubacterium, and Bacteroides in the present study, we could not show a significant correlation between M2 TAMs and intestinal microbiota. Since there was a possibility that certain intestinal microbiota could induce a shift from M1 TAMs to M2 TAMs, further investigation with larger cohorts is required.

Taken together, the results of the present study indicate that the immune responses to tumors would be suppressed in the tumor microenvironment of CRC depending on the increment of Tregs and the reduction of M1 TAMs. Furthermore, intestinal microbiota might be involved in immunosuppression.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- p-STAT1

Phosphorylated-STAT1

- PCoA

Principal coordinates analysis

- TAMs

Tumor-associated macrophages

- TIICs

Tumor-infiltrating immune cells

Author contributions

TK, KM, TT, and KK contributed to the study conception and design. TK, MA, HO, EE, KS, WS, SF, HE, MS, TM, ZS, and SO contributed to the acquisition of patient samples. TK, KM, MA, HO, WS, SF, HE, MS, TM, ZS, and SO performed flow cytometry and analyzed the flow cytometry data. KS, KY, and TT performed the 16S metagenome sequencing and analyzed the microbiota data. EE and KS performed IHC and evaluated the IHC staining. TK, KM, KS, KY, TT, and KK drafted the manuscript.

Funding

No relevant funding.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval and standards

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Fukushima Medical University Research Ethics Committee (Receipt No. 29020).

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study for the use of their specimens and clinical data for research and publication prior to collecting the specimen at Fukushima Medical University Hospital.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner H, Kloor M, Pox CP. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2014;383(9927):1490–1502. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cercek A, Roxburgh CSD, Strombom P, Smith JJ, Temple LKF, Nash GM, Guillem JG, Paty PB, Yaeger R, Stadler ZK, Seier K, Gonen M, Segal NH, Reidy DL, Varghese A, Shia J, Vakiani E, Wu AJ, Crane CH, Gollub MJ, Garcia-Aguilar J, Saltz LB, Weiser MR. Adoption of total neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gollins S, Sebag-Montefiore D. Neoadjuvant treatment strategies for locally advanced rectal cancer. Clin Oncol. 2016;28(2):146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellman I, Coukos G, Dranoff G. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature. 2011;480(7378):480–489. doi: 10.1038/nature10673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Afreen S, Dermime S. The immunoinhibitory B7-H1 molecule as a potential target in cancer: killing many birds with one stone. Hematol Oncol stem cell Ther. 2014;7(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.hemonc.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shibuya KC, Goel VK, Xiong W, Sham JG, Pollack SM, Leahy AM, Whiting SH, Yeh MM, Yee C, Riddell SR, Pillarisetty VG. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma contains an effector and regulatory immune cell infiltrate that is altered by multimodal neoadjuvant treatment. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tassi E, Gavazzi F, Albarello L, Senyukov V, Longhi R, Dellabona P, Doglioni C, Braga M, Di Carlo V, Protti MP. Carcinoembryonic antigen-specific but not antiviral CD4 + T cell immunity is impaired in pancreatic carcinoma patients. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2008;181(9):6595–6603. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Monte L, Reni M, Tassi E, Clavenna D, Papa I, Recalde H, Braga M, Di Carlo V, Doglioni C, Protti MP. Intratumor T helper type 2 cell infiltrate correlates with cancer-associated fibroblast thymic stromal lymphopoietin production and reduced survival in pancreatic cancer. J Exp Med. 2011;208(3):469–478. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ozdemir BC, Pentcheva-Hoang T, Carstens JL, Zheng X, Wu CC, Simpson TR, Laklai H, Sugimoto H, Kahlert C, Novitskiy SV, De Jesus-Acosta A, Sharma P, Heidari P, Mahmood U, Chin L, Moses HL, Weaver VM, Maitra A, Allison JP, LeBleu VS, Kalluri R. Depletion of carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and fibrosis induces immunosuppression and accelerates pancreas cancer with reduced survival. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(6):719–734. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soares KC, Rucki AA, Kim V, Foley K, Solt S, Wolfgang CL, Jaffee EM, Zheng L. TGF-β blockade depletes T regulatory cells from metastatic pancreatic tumors in a vaccine dependent manner. Oncotarget. 2015;6(40):43005–43015. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soares KC, Rucki AA, Wu AA, Olino K, Xiao Q, Chai Y, Wamwea A, Bigelow E, Lutz E, Liu L, Yao S, Anders RA, Laheru D, Wolfgang CL, Edil BH, Schulick RD, Jaffee EM, Zheng L. PD-1/PD-L1 blockade together with vaccine therapy facilitates effector T-cell infiltration into pancreatic tumors. J Immunother (Hagerstown, Md: 1997) 2015;38(1):1–11. doi: 10.1097/cji.0000000000000062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saito T, Nishikawa H, Wada H, Nagano Y, Sugiyama D, Atarashi K, Maeda Y, Hamaguchi M, Ohkura N, Sato E, Nagase H, Nishimura J, Yamamoto H, Takiguchi S, Tanoue T, Suda W, Morita H, Hattori M, Honda K, Mori M, Doki Y, Sakaguchi S. Two FOXP3(+)CD4(+) T cell subpopulations distinctly control the prognosis of colorectal cancers. Nat Med. 2016;22(6):679–684. doi: 10.1038/nm.4086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qian BZ, Pollard JW. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell. 2010;141(1):39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Condeelis J, Pollard JW. Macrophages: obligate partners for tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. Cell. 2006;124(2):263–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollard JW. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(1):71–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(1):23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mantovani A, Sica A. Macrophages, innate immunity and cancer: balance, tolerance, and diversity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22(2):231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biswas SK, Gangi L, Paul S, Schioppa T, Saccani A, Sironi M, Bottazzi B, Doni A, Vincenzo B, Pasqualini F, Vago L, Nebuloni M, Mantovani A, Sica A. A distinct and unique transcriptional program expressed by tumor-associated macrophages (defective NF-kappaB and enhanced IRF-3/STAT1 activation) Blood. 2006;107(5):2112–2122. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ojalvo LS, King W, Cox D, Pollard JW. High-density gene expression analysis of tumor-associated macrophages from mouse mammary tumors. Am J Pathol. 2009;174(3):1048–1064. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pucci F, Venneri MA, Biziato D, Nonis A, Moi D, Sica A, Di Serio C, Naldini L, De Palma M. A distinguishing gene signature shared by tumor-infiltrating Tie2-expressing monocytes, blood “resident” monocytes, and embryonic macrophages suggests common functions and developmental relationships. Blood. 2009;114(4):901–914. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-200931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakajima S, Koh V, Kua LF, So J, Davide L, Lim KS, Petersen SH, Yong WP, Shabbir A, Kono K. Accumulation of CD11c + CD163 + adipose tissue macrophages through upregulation of intracellular 11beta-HSD1 in human obesity. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2016;197(9):3735–3745. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dalmas E, Clement K, Guerre-Millo M. Defining macrophage phenotype and function in adipose tissue. Trends Immunol. 2011;32(7):307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill AA, Reid Bolus W, Hasty AH. A decade of progress in adipose tissue macrophage biology. Immunol Rev. 2014;262(1):134–152. doi: 10.1111/imr.12216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komohara Y, Fujiwara Y, Ohnishi K, Shiraishi D, Takeya M. Contribution of macrophage polarization to metabolic diseases. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2016;23(1):10–17. doi: 10.5551/jat.32359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deiuliis J, Shah Z, Shah N, Needleman B, Mikami D, Narula V, Perry K, Hazey J, Kampfrath T, Kollengode M, Sun Q, Satoskar AR, Lumeng C, Moffatt-Bruce S, Rajagopalan S. Visceral adipose inflammation in obesity is associated with critical alterations in tregulatory cell numbers. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e16376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michaud A, Pelletier M, Noel S, Bouchard C, Tchernof A. Markers of macrophage infiltration and measures of lipolysis in human abdominal adipose tissues. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2013;21(11):2342–2349. doi: 10.1002/oby.20341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boon MR, Bakker LE, Haks MC, Quinten E, Schaart G, Van Beek L, Wang Y, Van Schinkel L, Van Harmelen V, Meinders AE, Ottenhoff TH, Van Dijk KW, Guigas B, Jazet IM, Rensen PC. Short-term high-fat diet increases macrophage markers in skeletal muscle accompanied by impaired insulin signalling in healthy male subjects. Clin Sci (London, England: 1979) 2015;128(2):143–151. doi: 10.1042/cs20140179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Consortium HMP Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486(7402):207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sears CL, Pardoll DM. The intestinal microbiome influences checkpoint blockade. Nat Med. 2018;24(3):254–255. doi: 10.1038/nm.4511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castellarin M, Warren RL, Freeman JD, Dreolini L, Krzywinski M, Strauss J, Barnes R, Watson P, Allen-Vercoe E, Moore RA, Holt RA. Fusobacterium nucleatum infection is prevalent in human colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res. 2012;22(2):299–306. doi: 10.1101/gr.126516.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tahara T, Yamamoto E, Suzuki H, Maruyama R, Chung W, Garriga J, Jelinek J, Yamano HO, Sugai T, An B, Shureiqi I, Toyota M, Kondo Y, Estecio MR, Issa JP. Fusobacterium in colonic flora and molecular features of colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2014;74(5):1311–1318. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-13-1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kostic AD, Gevers D, Pedamallu CS, Michaud M, Duke F, Earl AM, Ojesina AI, Jung J, Bass AJ, Tabernero J, Baselga J, Liu C, Shivdasani RA, Ogino S, Birren BW, Huttenhower C, Garrett WS, Meyerson M. Genomic analysis identifies association of Fusobacterium with colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res. 2012;22(2):292–298. doi: 10.1101/gr.126573.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marchesi JR, Dutilh BE, Hall N, Peters WH, Roelofs R, Boleij A, Tjalsma H. Towards the human colorectal cancer microbiome. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e20447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burns MB, Lynch J, Starr TK, Knights D, Blekhman R. Virulence genes are a signature of the microbiome in the colorectal tumor microenvironment. Genome Med. 2015;7(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0177-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kostic AD, Chun E, Robertson L, Glickman JN, Gallini CA, Michaud M, Clancy TE, Chung DC, Lochhead P, Hold GL, El-Omar EM, Brenner D, Fuchs CS, Meyerson M, Garrett WS. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14(2):207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warren RL, Freeman DJ, Pleasance S, Watson P, Moore RA, Cochrane K, Allen-Vercoe E, Holt RA. Co-occurrence of anaerobic bacteria in colorectal carcinomas. Microbiome. 2013;1(1):16. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei Z, Cao S, Liu S, Yao Z, Sun T, Li Y, Li J, Zhang D, Zhou Y. Could gut microbiota serve as prognostic biomarker associated with colorectal cancer patients’ survival? A pilot study on relevant mechanism. Oncotarget. 2016;7(29):46158–46172. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fjeldborg K, Pedersen SB, Møller HJ, Christiansen T, Bennetzen M, Richelsen B. Human adipose tissue macrophages are enhanced but changed to an anti-inflammatory profile in obesity. J Immunol Res. 2014;2014:309548. doi: 10.1155/2014/309548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khodarev NN, Roizman B, Weichselbaum RR. Molecular pathways: interferon/stat1 pathway: role in the tumor resistance to genotoxic stress and aggressive growth. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(11):3015–3021. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-11-3225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edin S, Wikberg ML, Dahlin AM, Rutegård J, Öberg Å, Oldenborg PA, Palmqvist R. The distribution of macrophages with a M1 or M2 phenotype in relation to prognosis and the molecular characteristics of colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erreni M, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) and inflammation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Microenviron. 2011;4(2):141–154. doi: 10.1007/s12307-010-0052-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Braster R, Bogels M, Beelen RH, van Egmond M. The delicate balance of macrophages in colorectal cancer; their role in tumour development and therapeutic potential. Immunobiology. 2017;222(1):21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Norton SE, Ward-Hartstonge KA, Taylor ES, Kemp RA. Immune cell interplay in colorectal cancer prognosis. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015;7(10):221–232. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v7.i10.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.