Abstract

Adjuvant cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cell immunotherapy has shown potential in improving the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients after curative resection. However, whether an individual could obtain survival benefit from CIK cell treatment remains unknown. In the present study, we focused on the characteristics of CIK cells and aimed to identify the best predictive biomarker for adjuvant CIK cell treatment in patients with HCC after surgery. This study included 48 patients with HCC treated with postoperative adjuvant CIK cell immunotherapy. The phenotype activity and cytotoxic activity of CIK cells were determined by flow cytometry and xCELLigence™ Real-Time Cell Analysis (RTCA) system, respectively. Correlation analysis revealed that the cytotoxic activity of CIK cells was significantly negative correlated with the percentage of CD3+ CD4+ cell subsets, but significantly positive correlated with CD3-CD56+ and CD3+ CD56+ cell subsets. Survival analysis showed that there were no significant associations between patients’ prognosis and the phenotype of CIK cells. By contrast, there was statistically significant improvement in recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) for patients with high cytotoxic activity of CIK cells as compared with those with low cytotoxic activity of CIK cells. Univariate and multivariate analyses indicated that CIK cell cytotoxicity was an independent prognostic factor for RFS and OS. In conclusion, a high cytotoxic activity of CIK cells can serve as a valuable biomarker for adjuvant CIK cell immunotherapy of HCC patients after surgery.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00262-020-02486-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: CIK cell immunotherapy, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Cytotoxicity, Prognosis

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a common and aggressive cancer, representing the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide [1]. Surgical resection is considered to be a curative treatment option for patients with early stage HCC and preserved liver function [2]. However, the long-term outcome is still poor even after a radical surgery because of a high incidence of local recurrence and distant metastases [3, 4]. Such a high recurrence rate has led efforts to develop postoperative adjuvant therapies to reduce recurrence. However, whether postoperative adjuvant treatments can improve HCC patients’ outcome is unclear [5], and no adjuvant treatment for HCC is recommended after surgery according to current international guidelines.

Clinical studies have shown a potent anti-tumor activity of cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells against various tumors [6–10], including HCC [11, 12]. Recently, CIK cell-based immunotherapy has become a promising adjuvant treatment option for postoperative HCC patients [13]. Lee et al. found that adjuvant CIK cell immunotherapy improved recurrence-free and overall survival in patients who underwent radical surgery for HCC [13, 14]. Our previous clinical trial also demonstrated that adjuvant CIK cell treatment could prolong the median time to recurrence in HCC patients after curative resection [15]. Thus, CIK cells may serve as an alternative adjuvant cellular immunotherapy for HCC. However, the therapeutic benefit between HCC patients who receive postoperative adjuvant CIK cell immunotherapy varied significantly, and some patients were nonresponsive to CIK cell immunotherapy [16]. There were no standard biomarkers to indicate the immune status of hosts. It is warranted to identify biomarkers that can distinguish which patients are responsive to CIK cell treatment and which patients are ineffective.

CIK cells have several characters of rapid proliferation, a broad spectrum of anti-tumor activity (more sensitive to multidrug-resistant tumor cells and cancer stem cells), strong anti-tumor activity, and minimal toxicity [17], which are generated by expanding peripheral blood mononuclear cells with cytokines comprising IFN-γ, IL-2, and anti-CD3 antibody [18]. Meanwhile, CIK cells are a mixture of cell population, containing CD3+ CD4+ , CD3+ CD8+ , CD3+ CD56+ , and CD3-CD56+ cell subsets. Therefore, we explored whether the phenotype and cytotoxic activity of CIK cells could serve as a predictor of the efficacy of adjuvant CIK cell treatment for patients with HCC after curative resection.

This study aimed to characterize the phenotype and cytotoxic activity of CIK cells and to evaluate their correlation with prognosis of HCC patients who underwent surgical resection and received adjuvant CIK cell immunotherapy. This study provides valuable evidence as to whether the phenotype and cytotoxic activity of CIK cells could be a potent biomarker in predicting the response of CIK cell treatment.

Materials and methods

Study population

CIK cell treatment was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, and complied with the provisions of the Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines and Declaration of Helsinki. Written consent from each patient was obtained. Between November 2014 and October 2015, a total of 48 HCC patients were included in this study. All of the patients underwent curatively surgical resection as initial treatment, and received adjuvant CIK cell immunotherapy at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center.

CIK cell preparation

CIK cells were generated according to the established procedures as described in our previous studies [19, 20]. Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were separated by Ficoll-Hypaque density centrifugation, resuspended at 2 × 106 cells/mL in fresh serum-free X-VIVO 15 medium (Lonza, Visp, Switzerland) supplemented with 1000 U/mL recombinant human IFN-γ (Shanghai Clone Company) for the first 24 h. Then, 100 ng/mL mouse anti-human CD3 monoclonal antibody (R&D Systems, MN, USA), 1000 U/mL IL-2 (Beijing Sihuan Pharm, Beijing, China), and 100 U/mL IL-1α (Life Technologies, CA, USA) were added to the medium. Fresh medium-containing IL-2 was refreshed every 2 days and the CIK cells were harvested at 14 days. A fraction of harvested CIK cells were collected to detect their phenotype and cytotoxicity. The bulk of fresh CIK cells were infused into the patients within 60 min after quality inspection.

Phenotypic analyses

After culturing for 14 days, the phenotype of the autologous CIK cells from each patient was characterized using flow cytometry (FC500, Beckman Coulter, CA, USA). Briefly, CIK cells were resuspended at 2 × 105 cells per 100 μL of phosphate-buffered saline and incubated for 20 min at 4 °C with the following anti-human antibodies: anti-CD3-Phycoerythrin (PE)-cyanine (Cy) 5, anti-CD4-PE-Cy7, anti-CD8-PE, and anti-CD56-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (all from BD Bioscience, NJ, USA). Corresponding isotype antibodies were used to stain the cells of the negative control. After washing twice, the cells were analyzed using a CytomicsTM FC500 Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter, USA), and data analysis was performed with CXP analysis software (Beckman Coulter). Then, based on the median percentage of each cell subsets (CD3+ CD4+ , CD3+ CD8+ , CD3+ CD56+ , and CD3-CD56+), patients were divided into high percentage group and low percentage group.

Cell-mediated lysis assay using xCELLigence system

In the cytotoxic assay, the cytotoxicity of CIK cells was assessed using the xCELLigence™ Real-Time Cell Analysis (RTCA) system (E-plate, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) which is placed into the standard cell culture incubator where the experiment takes place [21]. The CIK cells from each patient were effector cells, and the target cells were two HCC cell lines, HepG2 and BEL-7402, which were obtained from the Committee of the Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) and cultured at RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS,Gibco, Grand Island, NY) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. For cell-mediated lysis assay, target cells (2.0 × 104 cells/well) were seeded into 96-well E-plates for approximately 24 h followed by addition of CIK cells (50 μl/well) into the E-plates at an effector:target cells ratio of 3:1, 10:1, and 30:1. Cocultures were assessed by the xCELLigence RTCA system with a measure every 15 min for up to 48 h. The system dynamically monitors electrical impedance across interdigitated microelectrodes integrated on the bottom of tissue culture E-plates. The electrical impedance values, expressed as cell index (CI), provide quantitative information of living adherent tumor cells. Results are shown as percentage of lysis determined from cellular index (CI) normalized with RTCA Software: percentage of lysis = [CI (no effector) − CI (effector)]/CI (no effector) × 100%. The median values of cytotoxicity of CIK cells were used as cut-offs for defining the subgroups (high cytotoxicity group and low cytotoxicity group).

Surgical resection and CIK cell treatment

All included patients underwent curative resection by experienced surgeons. After surgery, patients received CIK infusions intravenously in an upper limb at each cycle. In general, patients will receive at least four cycles of CIK cell treatment with 2-week intervals between each cycle. The cell dose was based on the total viable cell number, as determined by manual hemacytometer cell counts. Before infusion, samples of CIK were evaluated for viability using the dye exclusion test and checked to exclude possible contamination by bacteria, fungi, and endotoxins. The patients were eligible for CIK cell maintenance treatment at an interval of 1–3 months if they were free of disease. Otherwise, the CIK cell treatment would be stopped if the tumor recurrence or the patients did not want to continue. For patients who suffered from tumor recurrence, a second resection or other therapies (RFA, TACE, SIRT, and sorafenib) were decided by a multidisciplinary group, which consisted of surgeons, physicians, interventional oncologist, and immunologists.

Follow-up

All the HCC patients were follow-up regularly after discharge, including clinic or telephone contact once every 3 months during the first 2 years, every 6 months from the 3rd to 5th years, and annually thereafter. At each follow-up visit, serum AFP, abdominal ultrasonography, and chest radiography were obtained. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was measured from the date of surgery to the first recurrence or to the date of death. Overall survival (OS) was defined from the time of surgery until death or the end of follow-up date.

Statistical analysis

For the comparison of groups, the Pearson chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test were used where appropriate. RFS and OS curves were constructed according to the Kaplan–Meier method. The difference of survival time between each subgroup was assessed by log-rank test. Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the Cox proportional hazard model. The correlation between the phenotype and cytotoxicity of CIK cells was analyzed using the Pearson chi-squared test. All statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software (Statistical Package for the Social Science, version 17.0, IBM Corp. Armonk, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism 5 (Version 5.01, GraphPad Software, Inc.). P < 0.05 was considered statistical significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the patients

In total, 48 patients with HCC were recruited for investigation; 39 (81.3%) were men and 9 (18.7%) were women. The median age was 52 years (range, 21–79 years). All patients received complete hepatectomy and 44 (91.7%) were Child–Pugh classes A; 42 (87.5%) patients were positive for HBsAg and 16 (33.3%) patients had multiple tumor sites (Table 1).

Table 1.

Correlation of clinicopathologic and CIK cell cytotoxicity in HCC patients

| Characteristic | Target (HepG2) | P | Target (BEL-7402) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High cytotoxicity | Low cytotoxicity | High cytotoxicity | Low cytotoxicity | |||

| No. of patients | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | ||

| Sex | 0.712 | 0.712 | ||||

| Male | 20 | 19 | 20 | 19 | ||

| Female | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Age (years) | 0.562 | 1.000 | ||||

| ≥ 50 | 14 | 12 | 13 | 13 | ||

| < 50 | 10 | 12 | 11 | 11 | ||

| HBsAg | 1.000a | 1.000a | ||||

| Positive | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | ||

| Negative | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Histology | 1.000a | 0.361a | ||||

| Well differentiated | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | ||

| Moderate differentiated | 17 | 17 | 16 | 18 | ||

| Poorly differentiated | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | ||

| AFP (ng/mL) | 0.140 | 0.140 | ||||

| ≤ 25 | 17 | 12 | 17 | 12 | ||

| > 25 | 7 | 12 | 7 | 12 | ||

| Child–Pugh score | 1.000a | 1.000a | ||||

| A | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | ||

| B | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.551 | 0.551 | ||||

| ≤ 5 | 16 | 14 | 16 | 14 | ||

| > 5 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 10 | ||

| Tumor number | 0.221 | 0.221 | ||||

| Single | 18 | 14 | 18 | 14 | ||

| Multiple | 6 | 10 | 6 | 10 | ||

HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, CIK cytokine-induced killer cell, AFP Alpha-fetoprotein, HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen

aFisher’s exact test

The phenotype of CIK cells

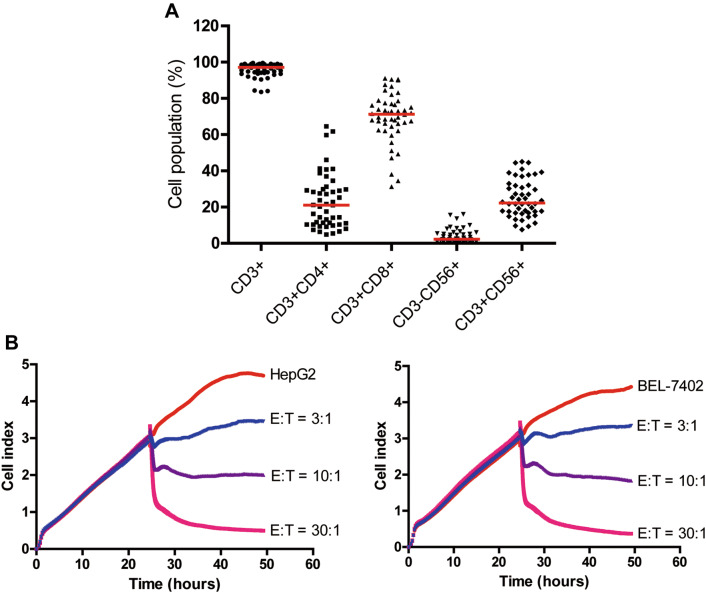

After 14 days of expansion, the final number of CIK cells was approximately 1.0 × 1010–1.5 × 1010). All cultured CIK cells were infused back into the patients after quality inspection, such as viability, possible contamination, and endotoxin test. The phenotype of CIK cells was determined by flow cytometry. We found that there were obvious variations among different patients. The median percentage of CD3+, CD3+CD4+, CD3+CD8+, CD3−CD56+, and CD3+CD56+ population in the final CIK cells was 97.2% (range, 83.5–99.6%), 21.1% (range, 4.8–64.5%), 71.3% (range, 31.3–91.1%), 2.3% (range, 0.2–16.0%), and 22.3% (range, 7.5–45.0%), respectively (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Characteristics of CIK cells after expansion. a The phenotype of autologous CIK cells after 14-day culture from 48 patients was evaluated using flow cytometry. The positive proportions of CD3+, CD3+CD4+, CD3+CD8+, CD3−CD56+, and CD3+CD56+ are shown. b Cell index (CI) values of HCC cell lines incubated alone or with varying concentrations of CIK cells as determined by the xCELLigence RTCA system. Representative time- and dose-dependent effects of CIK cells on HepG2 and BEL-7402 cell lines by real-time monitoring are shown. E effector cells, T target cells

Cytotoxic activity of CIK cells

CIK cell-mediated lysis of HCC cells was evaluated using the xCELLigence™ RTCA system that allows the dynamic measure of adherent target cell index (CI), which is correlated with attached tumor cell viability [22]. CI values obtained from xCELLigence RTCA system demonstrated that CIK cells efficiently killed HCC cells in an E/T ratio- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 1b). These values also showed that CIK cells exhibited the highest levels of cytotoxicity against HCC cell lines at an E/T ratio of 30:1 as compared to an E/T ratio of 10:1 or 3:1(Fig. 1b). CIK cell cytotoxicity increased rapidly after 6 h of co-culturing with either HepG2 or BEL-7402 cell lines at an E/T ratio of 30:1, which was recorded and further used in subsequent analysis (Fig. 1b). Besides, the cytotoxic activity of CIK cells against the two HCC cell lines was comparable (Supplementary Fig. 1), the median values of which were used as cut-offs for defining the subgroups (high cytotoxicity group and low cytotoxicity group).

Association between the phenotype and cytotoxicity of CIK cells

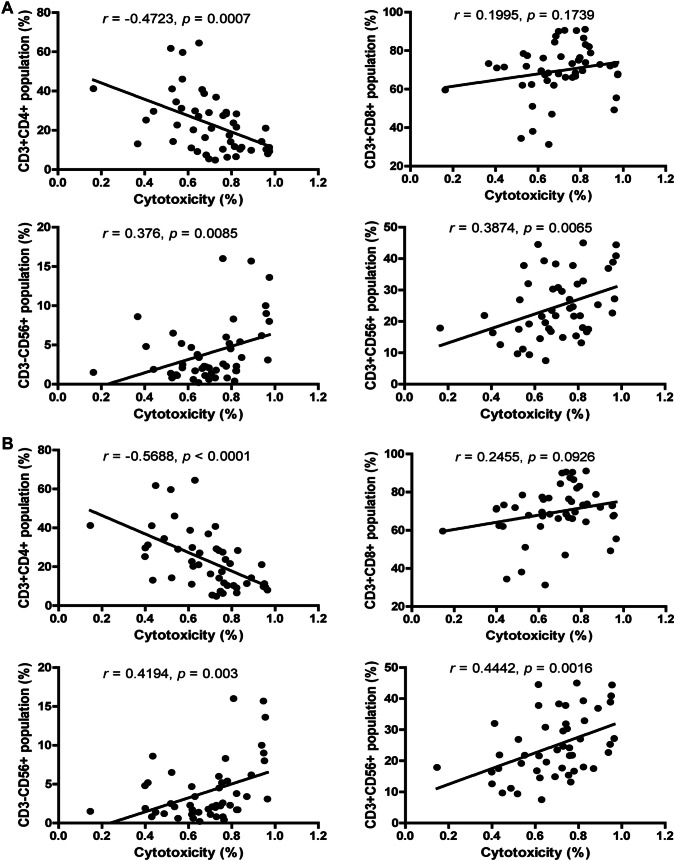

As CIK cells are a mixture of cell population and CD3+CD56+ subsets represent the main anti-tumor immuno-effector cells [23, 24], we further investigated the relationship between the phenotype and cytotoxicity of CIK cells. The percentage of CD3+ CD4+ cell subsets negatively correlated with the cytotoxicity of CIK cells against both HepG2 and BEL-7402 (Fig. 2a, b; P = 0.0007 for HepG2; P < 0.0001 for BEL-7402). The percentage of CD3-CD56+ and CD3+ CD56+ cell subsets positively correlated with the cytotoxicity of CIK cells against both HepG2 and BEL-7402 (Fig. 2a, b; CD3-CD56+ : P = 0.0085 for HepG2; P = 0.003 for BEL-7402; CD3+ CD56+ : P = 0.0065 for HepG2; P = 0.0016 for BEL-7402). However, no obvious correlation was observed between the percentage of CD3+ CD8+ cell subsets and the cytotoxicity of CIK cells (Fig. 2a, b).

Fig. 2.

Association between the phenotype and cytotoxicity of CIK cells. Pearson’s correlation analyses for the correlation between the phenotype and cytotoxic activity of CIK cells against HepG2 (a) and BEL-7402 (b) cell lines

Associations between the phenotype and cytotoxicity of CIK cells and survival benefits from CIK cell therapy

By the end of follow-up, 43.75% (21/48) of the patients died. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS rates for the whole study population after postoperative adjuvant CIK cell immunotherapy were 89.6%, 73.9%, and 51.4%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2a). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates were 93.8%, 80.9%, and 67.2%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2b).

To explore whether the phenotype and cytotoxicity of CIK cells could be a potential factor that affect the clinical efficacy of CIK cell treatment, we first investigated the correlation between the phenotype of CIK cells and prognosis of patients with HCC who received postoperative adjuvant CIK cell treatment. Patients were divided into two groups, high percentage group and low percentage group, based on the median percentage of each cell subsets. Unexpectedly, there were no significant associations between RFS or OS and the phenotype of CIK cells, regardless of CD3+ CD4+ , CD3+ CD8+ , CD3-CD56+, and CD3+ CD56+ (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier overall survival (OS) curves for patients with HCC stratified into groups with high and low percentages of different subsets of CIK cells. There were no significant associations between OS and the phenotype of CIK cells, regardless of CD3+ CD4+ , CD3+ CD8+ , CD3-CD56+, and CD3+ CD56+

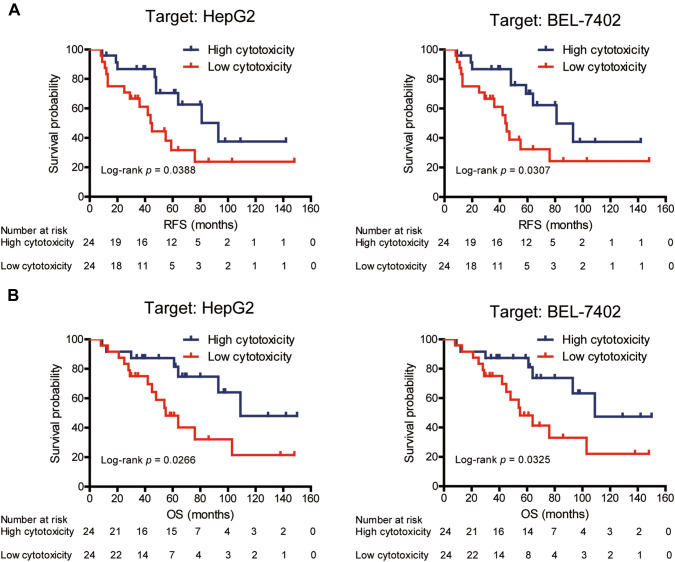

We next investigated the effect of cytotoxic activity of CIK cells on patient prognosis. Based on the median values of CIK cell cytotoxicity, patients were divided into high cytotoxicity group and low cytotoxicity group. The proportion of patients’ sex, age, HBsAg, histology, AFP, Child–Pugh score, tumor size, and tumor number were comparable between the two groups (Table 1). Survival analysis revealed that there was statistically significant improvement in RFS and OS for patients with high cytotoxic activity of CIK cells as compared with those with low cytotoxic activity of CIK cells (Fig. 4; log-rank test; RFS: P = 0.0388 for HepG2; P = 0.0307 for BEL-7402; OS: P = 0.0266 for HepG2; P = 0.0325 for BEL-7402). Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analyses were used to evaluate the impact of CIK cell cytotoxicity on the prognosis of patients with HCC. Low tumor size and high CIK cell cytotoxicity were significantly associated with better RFS and OS in the univariate analysis (Tables 2, Supplementary Table 1). Further multivariate survival analysis indicated that low tumor size and high CIK cell cytotoxicity were independent prognostic factors for improved RFS and OS (Tables 2, Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves of recurrence-free survival (RFS) (a) and overall survival (OS) (b) for patients with HCC stratified into groups with high and low cytotoxicity of CIK cells. After co-culturing for 6 h at an E/T ratio of 30:1, the median values of cytotoxic activity of CIK cells against either HepG2 or BEL-7402 cell lines were used as cut-offs for defining the subgroups (high cytotoxicity group and low cytotoxicity group). There was statistically significant improvement in both RFS and OS for patients with high cytotoxic activity of CIK cells against either HepG2 or BEL-7402 cell lines, comparing with those with low cytotoxic activity of CIK cells

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of overall survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 2.163 (0.503–9.311) | 0.300 | ||

| Age (≥ 50 vs. < 50) | 0.966 (0.405–2.304) | 0.938 | ||

| HBsAg (positive vs. negative) | 1.441 (0.335–6.195) | 0.623 | ||

| Histology (poorly vs. moderate vs. well) | 1.179 (0.541–2.571) | 0.679 | ||

| AFP (> 25 vs. ≤ 25) | 1.431 (0.606–3.379) | 0.414 | ||

| Child–Pugh score (B vs. A) | 1.512 (0.196–11.693) | 0.692 | ||

| Tumor size (> 5 vs. ≤ 5) | 3.137 (1.220–8.065) | 0.018a | 3.189 (1.209–8.413) | 0.019a |

| Tumor number (multiple vs. single) | 1.836(0.767–4.397) | 0.173 | ||

| CIK cell cytotoxicity (high vs. low)b | 0.364 (0.146–0.912) | 0.031a | 0.378 (0.150–0.952) | 0.039a |

HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval

aP value < 0.05

bHepG2 was the target

Discussion

Our and others previous clinical studies observed that adjuvant CIK cell treatment could improve the prognosis of HCC patients after curative resection [13–15, 25] Therefore, CIK cells may serve as an alternative adjuvant therapy for HCC. However, the survival of individuals received CIK cell treatment varied significantly (OS range, 8–150 months), indicating that identifying biomarkers that can differentiate between responders and non-responders are warranted to achieve optimal outcome and cost-effectiveness. In the present study, we focused our research on the relationship between characteristics of CIK cells and clinical benefit of HCC patients from adjuvant CIK cell immunotherapy. We explored whether the phenotype and cytotoxic activity of CIK cells could serve as a predictor of adjuvant CIK therapy among HCC patients after surgery. The results showed that CIK cell cytotoxicity, but not CIK cell phenotype, could be a biomarker for predicting favorable efficacy of CIK cell-assisted immunotherapy of HCC patients after surgery.

CIK cells, first reported by Schmidt-Wolf et al., are a group of heterogeneous immune-active host effector cells, mainly comprising of CD3+ CD4+ , CD3+ CD8+ , CD3+ CD56+ , and CD3-CD56+ cell subsets [18]. We also observed that the percentage of CD3+ CD4+ , CD3+ CD8+ , CD3+ CD56+ , and CD3-CD56+ cell subsets varied among patients. The cytotoxic activity of CIK cells was significantly negative correlated with the percentage of CD3+ CD4+ cell subsets, but significantly positive correlated with the percentage of CD3-CD56+ and CD3+ CD56+ cell subsets. However, none of these cell subsets could be a biomarker in predicting the response of CIK cell treatment with regard to patients’ survival benefit, although CD3+ CD56+ cell subsets are considered as the main anti-tumor immuno-effector cells [23, 24]. A possible explanation for this observation may be the fact that the phenotype of CIK cells evolves during ex vivo expansion and in vivo development period [23, 26]. Thus, the period chose in this study to detect the phenotype of CIK cells may be not the optimal, and another time point to detect the phenotype of CIK cells is warranted to further evaluate their association.

The cytotoxic activity of CIK cells is mediated by releasing perforin and granzyme granules and dependent on several activating receptors such as NKG2D, NKp30, NKp44, NKp46, and DNAM-1 [17]. Thus, the clinical effect of CIK cells may be due to the direct tumor killing activity in a non-MHC-restricted way [27]. To detect the cytotoxic activity of CIK cells more sensitive and reproducible, instead of chromium release assay or LDH cytotoxicity assay, the xCELLigence™ RTCA system was used to conduct the cytotoxicity assays, which collects continuous real-time data and allows the user to compare multiple lysis time points on the same experiment with minimal additional labor and cells [21]. Unlike the phenotype, the cytotoxic activity of CIK cells was significantly positive correlated with the RFS and OS of HCC patients. Furthermore, multivariate survival analysis suggested that the CIK cell cytotoxicity was an independent prognostic factor for RFS and OS, indicating that CIK cell cytotoxicity can be an indicator of adjuvant CIK cell treatment for patients with HCC after surgery. A plausible explanation for such difference in the effect of phenotype and cytotoxicity of CIK cells is that the highest cytotoxic activity of CIK cells occurs at day 14–15, which corresponds to the optimal time of clinical transfusion of CIK cells [26], thus accurately reflecting the characteristic of CIK cells.

Our study has several limitations. First, this is a single-center-based retrospective study. External validation is warranted to achieve the optimal cut-off of CIK cell cytotoxicity. Second, small sample size may underestimate the value of CIK cell phenotype. Third, we did not detect immune suppressor cell subpopulations among CIK cell agent, which could reduce the clinical efficacy of CIK cells [28, 29]. Analyzing the correlation between immune suppressor cell subpopulations of CIK cells and patients’ prognosis is warranted to further verify the present results. Nevertheless, our study primarily revealed that cytotoxic activity of CIK cells was a valuable biomarker in predicting the survival benefit of CIK immunotherapy in HCC patients.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that it is CIK cell cytotoxicity, but not CIK cell phenotype, that could be a biomarker for predicting favorable efficacy of adjuvant CIK cell immunotherapy of HCC patients after surgery. Additional multicenter and large sample external validation studies are required to verify our results.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was primarily supported by a grant from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2018YFC1313400), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81803079; 81402560; 81572865; 81472387), the Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (No. 2018A030310237), and the Guangdong Province Science and Technology Plan Project (No. 2017A020215029).

Abbreviations

- CI

Cellular index

- CIK cells

Cytokine-induced killer cells

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- OS

Overall survival

- RFS

Recurrence-free survival

- RTCA system

Real-Time Cell Analysis system

Author contributions

QZP and QL: data collection, assembly, and data analysis. YQZ, JJZ, QJW, YQL, JMG, YT, JH, and SPC: cell generation, and data analysis and interpretation. DSW and JCX: designed and directed the overall project. QZP, QL, DSW, and JCX: manuscript writing and final approval of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board of the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center approved the study design (B2016-035-01). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Qiu-Zhong Pan and Qing Liu have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

De-Sheng Weng, Email: wengds@sysucc.org.cn.

Jian-Chuan Xia, Email: xiajch@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Page AJ, Cosgrove DC, Philosophe B, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: diagnosis, management, and prognosis. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2014;23(2):289–311. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai EC, Fan ST, Lo CM, et al. Hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. An audit of 343 patients. Ann Surg. 1995;221(3):291–298. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199503000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhir M, Melin AA, Douaiher J, et al. A review and update of treatment options and controversies in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2016;263(6):1112–1125. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samuel M, Chow PK, Chan Shih-Yen E et al (2009) Neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy for surgical resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD001199 10.1002/14651858.CD001199.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Xiao Z, Wang CQ, Feng JH, et al. Effectiveness and safety of chemotherapy with cytokine-induced killer cells in non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 32 randomized controlled trials. Cytotherapy. 2019;21(2):125–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2018.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu J, Li R, Tiselius E et al (2017) Immunotherapy (excluding checkpoint inhibitors) for stage I to III non-small cell lung cancer treated with surgery or radiotherapy with curative intent. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12:CD011300 10.1002/14651858.CD011300.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Zhou X, Mo X, Qiu J, et al. Chemotherapy combined with dendritic cell vaccine and cytokine-induced killer cells in the treatment of colorectal carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:5363–5372. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S173201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma Y, Zhang Z, Tang L, et al. Cytokine-induced killer cells in the treatment of patients with solid carcinomas: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Cytotherapy. 2012;14(4):483–493. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2011.649185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmeel LC, Schmeel FC, Coch C, et al. Cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells in cancer immunotherapy: report of the international registry on CIK cells (IRCC) J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2015;141(5):839–849. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1864-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen C, Ma YH, Zhang YT, et al. Effect of dendritic cell-based immunotherapy on hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cytotherapy. 2018;20(8):975–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao J, Kong FH, Liu X, et al. Immunotherapy with dendritic cells and cytokine-induced killer cells for hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(27):3649–3663. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i27.3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JH, Lee JH, Lim YS, et al. Adjuvant immunotherapy with autologous cytokine-induced killer cells for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(7):1383–1391. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JH, Lee JH, Lim YS, et al. Sustained efficacy of adjuvant immunotherapy with cytokine-induced killer cells for hepatocellular carcinoma: an extended 5-year follow-up. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019;68(1):23–32. doi: 10.1007/s00262-018-2247-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu L, Wang J, Kim Y, et al. A randomized controlled trial on patients with or without adjuvant autologous cytokine-induced killer cells after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5(3):e1083671. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1083671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan QZ, Wang QJ, Dan JQ, et al. A nomogram for predicting the benefit of adjuvant cytokine-induced killer cell immunotherapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9202. doi: 10.1038/srep09202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mata-Molanes JJ, Sureda Gonzalez M, Valenzuela Jimenez B, et al. Cancer immunotherapy with cytokine-induced killer cells. Target Oncol. 2017;12(3):289–299. doi: 10.1007/s11523-017-0489-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt-Wolf IG, Negrin RS, Kiem HP, et al. Use of a SCID mouse/human lymphoma model to evaluate cytokine-induced killer cells with potent antitumor cell activity. J Exp Med. 1991;174(1):139–149. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan K, Guan XX, Li YQ, et al. Clinical activity of adjuvant cytokine-induced killer cell immunotherapy in patients with post-mastectomy triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(11):3003–3011. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan QZ, Tang Y, Wang QJ, et al. Adjuvant cellular immunotherapy in patients with resected primary non-small cell lung cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4(9):e1038017. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1038017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erskine CL, Henle AM, Knutson KL. Determining optimal cytotoxic activity of human Her2neu specific CD8 T cells by comparing the Cr51 release assay to the xCELLigence system. J Vis Exp. 2012;66:e3683. doi: 10.3791/3683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Messaoudene M, Fregni G, Fourmentraux-Neves E, et al. Mature cytotoxic CD56(bright)/CD16(+) natural killer cells can infiltrate lymph nodes adjacent to metastatic melanoma. Cancer Res. 2014;74(1):81–92. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt-Wolf IG, Lefterova P, Mehta BA, et al. Phenotypic characterization and identification of effector cells involved in tumor cell recognition of cytokine-induced killer cells. Exp Hematol. 1993;21(13):1673–1679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu PH, Negrin RS. A novel population of expanded human CD3+CD56+ cells derived from T cells with potent in vivo antitumor activity in mice with severe combined immunodeficiency. J Immunol. 1994;153(4):1687–1696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan K, Li YQ, Wang W, et al. The efficacy of cytokine-induced killer cell infusion as an adjuvant therapy for postoperative hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(13):4305–4311. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang L, Wang J, Wei F, et al. Profiling the dynamic expression of checkpoint molecules on cytokine-induced killer cells from non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2016;7(28):43604–43615. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verneris MR, Karimi M, Baker J, et al. Role of NKG2D signaling in the cytotoxicity of activated and expanded CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2004;103(8):3065–3072. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li H, Yu JP, Cao S, et al. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells decreased the antitumor activity of cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells of lung cancer patients. J Clin Immunol. 2007;27(3):317–326. doi: 10.1007/s10875-007-9076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang L, Qiao G, Morse MA, et al. Predictive significance of T cell subset changes during ex vivo generation of adoptive cellular therapy products for the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett. 2019;18(6):5717–5724. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.