Abstract

Objectives

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and sleep problems are highly prevalent among the general population. Both them are associated with a variety of psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety, which is highlighting an underexplored connection between them. This meta-analysis aims to explore the association between sleep problems and GERD.

Methods

We conducted a comprehensive search on PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, and Web of Science, using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords, covering articles from the inception of the databases until August 2023. Stata statistical software, version 14.0, was utilized for all statistical analyses. A fixed-effects model was applied when p > 0.1 and I2 ≤ 50%, while a random-effects model was employed for high heterogeneity (p < 0.1 and I2 > 50%). Funnel plots and Egger’s test were used to assess publication bias.

Results

Involving 22 studies, our meta-analysis revealed that insomnia, sleep disturbance, or short sleep duration significantly increased the risk of GERD (OR = 2.02, 95% CI [1.64–2.49], p < 0.001; I2 = 66.4%; OR = 1.98, 95% CI [1.58–2.50], p < 0.001, I2 = 50.1%; OR = 2.66, 95% CI [2.02–3.15], p < 0.001; I2 = 62.5%, respectively). GERD was associated with an elevated risk of poor sleep quality (OR = 1.47, 95% CI [1.47–1.79], p < 0.001, I2 = 72.4%), sleep disturbance (OR = 1.47, 95% CI [1.24–1.74], p < 0.001, I2 = 71.6%), or short sleep duration (OR = 1.17, 95% CI [1.12–1.21], p < 0.001, I2 = 0).

Conclusion

This meta-analysis establishes a bidirectional relationship between four distinct types of sleep problems and GERD. The findings offer insights for the development of innovative approaches in the treatment of both GERD and sleep problems.

Keywords: Gastroesophageal reflux disease, GERD, Insomnia, Sleep disturbance, Short sleep duration, Poor sleep quality

Introduction

As the pace of life quickens, sleep problems are becoming increasingly prevalent. with an article reporting a prevalence rate of 7% (Liu et al., 2016). The digestive system is particularly sensitive to lifestyle changes due to its connection to emotions, resulting in an increase in gastrointestinal disorders such as gastroesophageal reflux disease. Disrupted circadian rhythms due to sleep problems can impact melatonin secretion, potentially leading to depression and anxiety (De Berardis et al., 2013), factors that may exacerbate GERD incidence (Zamani et al., 2023). Moreover, a link has been found between GERD and sleep problems; individuals with either GERD (Hu et al., 2024) or sleep problems (Shoib et al., 2022) are more likely to experience obstructive sleep apnea.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), is a condition triggered by the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus, with its diagnosis being based on typical symptoms or visible mucosal damage observed during endoscopy (Sasankan & Thota, 2022). As its prevalence rises, further investigation becomes imperative (Peery et al., 2019). Despite recent advancements in our understanding of its pathology, drug development, and treatment methods, optimal patient outcomes are yet to be achieved. This underscores the urgency to augment clinician awareness of GERD-related symptoms for early diagnosis, and addressing early risk factors may be key to preventing the development of GERD. Prior meta-analyses confirm higher GERD prevalence in obese, smoking, and NSAID individuals (Eusebi et al., 2018). Additionally, a correlation has been identified linking reflux to apnea, reduced sleep efficiency, and decreased oxygen levels during sleep (El Hage Chehade et al., 2023), which warrants further exploration of sleep issues and their connection to GERD.

Sleep problems, ranging from insomnia, short duration, disturbances, and poor quality, are encountered among the general population and are associated with a broad array of health complications, such as lung disease (Sunwoo & Owens, 2022), high blood pressure(Ziegler, 2003), cardiovascular conditions (Pomeroy et al., 2023), migraines (Bigal & Lipton, 2006), cognitive decline (Sun et al., 2023), and mental disorders (On et al., 2017). Insufficient sleep can precipitate abnormal acid exposure in the esophagus (Yamasaki, Quan & Fass, 2019), a significant risk factor for GERD due to prolonged acid exposure (Hung et al., 2016). GERD is particularly linked to insomnia (Suganuma et al., 2001), and this relationship forms the basis of our hypothesis: we propose a potential bidirectional relationship between GERD and sleep problems, and to examine this, we conducted a methodical review of population-based evidence to elucidate their association.

Method

This study was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Evaluation and Meta-Analysis 2020 (PRISMA, 2020) guidelines (Page et al., 2021). The protocols have been pre-registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) platform under the approval number: CRD42023452348.

Data sources

We retrieved publicly accessible studies up to August 2023 from PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase and Web of Science. The language is restricted to English. The search strategy was a combination of medical subject headings (Mesh) and text words. The keywords used for the search were ‘gastro-esophageal reflux’, ‘gastric acid reflux’, ‘gastric acid reflux disease’, ‘gastro-esophageal reflux disease’, ‘reflux disease, gastro-esophageal’ as well as ‘sleep*’. All search terms used for the retrieval of articles are detailed in Tables S3–S6.

Eligibility criteria

We included case-control or cohort studies that assessed the association between gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and sleep problems. According to the Montreal definition, GERD is a condition which develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications (Vakil et al., 2006). A diagnosis of GERD could be made clinically by any of the following: (A) heart burn and/or regurgitation of any severity, or symptoms felt to be compatible with gastroesophageal reflux as diagnosed by a clinician or according to a questionnaire; (B) esophageal erosions defined by endoscopy. Sleep problems almost always can be diagnosed based solely on a careful history. Therefore, after reviewing the literature, we have identified four categories of sleep problems, including: sleep disturbance, short sleep duration, insomnia and poor sleep quality. In this study, sleep disturbance means people were found to be struggling to fall asleep, or waking up too early and not being able to get back to sleep. Criteria for insomnia include difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) or self-report. Short sleep duration was defined as sleeping less than 7 h on average per night. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index or a Likert scale containing the question: how do you rate your sleep quality is used to assess sleep quality. Poor sleep quality is considered to be present if the patient’s Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index is higher than normal or if the patient reports that sleep quality is poor.

The articles included had to be fulfilled the following criteria: (1) case-control or cohort study; (2) investigations of the association of gastroesophageal reflux with the risk of incident any type of sleep problem vice versa; (3) provide an odds ratio (OR) estimate with corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). The exclusion criteria included the following: (1) Studies did not provide an odds ratio (OR) estimate with 95% confidence interval (CI). (2) Literature with the same data. (3) Conference abstracts, study protocols, duplicate publications and studies without outcomes of interest.

Study selection

Study selection was performed by two reviewers (XLT and SSW) who independently screened the literature based on the eligibility and exclusion criteria. Duplicate and irrelevant articles were first excluded from the titles and abstracts. The full text of potentially eligible articles was then downloaded and read to identify all eligible studies. Any disagreements were resolved by the third reviewer (WFJ), who acted as an arbiter.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (XLT, FJW) independently extracted the following information according to the guideline for data extraction for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (Taylor, Mahtani & Aronson, 2021), including the following information: first author, study type, country, year of publication, age of participants, sample size, diagnosis of GERD and different type of sleep problem, type of sleep problem, confounder, odds ratio and 95% confidence interval.

Risk of bias

To ensure a comprehensive assessment, risk of bias was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) (Glaviano, Bazett-Jones & Boling, 2022) by classifying studies as either case-control or cohort studies. The NOS tool awards stars to responses meeting the eligibility criteria, a maximum total of nine stars can be attained by each study: four for selection, two for comparability, and three for outcome, with a higher star count reflective of a superior study quality. Scores of 0–3, 4–6, and 7–9 were regarded as indicative of low, moderate, and high quality, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The adjusted OR and 95% CI from each study were used to assess the association between GERD and sleep problems. The χ2 test and I2 values were used for the assessment of heterogeneity. A fixed effects model was used when p > 0.1 and I2 ≤ 50%. If p < 0.1 and I2 > 50% indicated high heterogeneity (Lei et al., 2022), a random effects model was used (Higgins et al., 2003). To check the robustness of the overall effects, the sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding one study each time and rerunning the analysis. Publication bias was confirmed by visual inspection of funnel plots and statistical assessment using Egger’s regression test (Egger et al., 1997). We performed several analyses based on GERD and each type of sleep problem. All statistical analyses were carried out using the Stata statistical software package, version 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Literature search

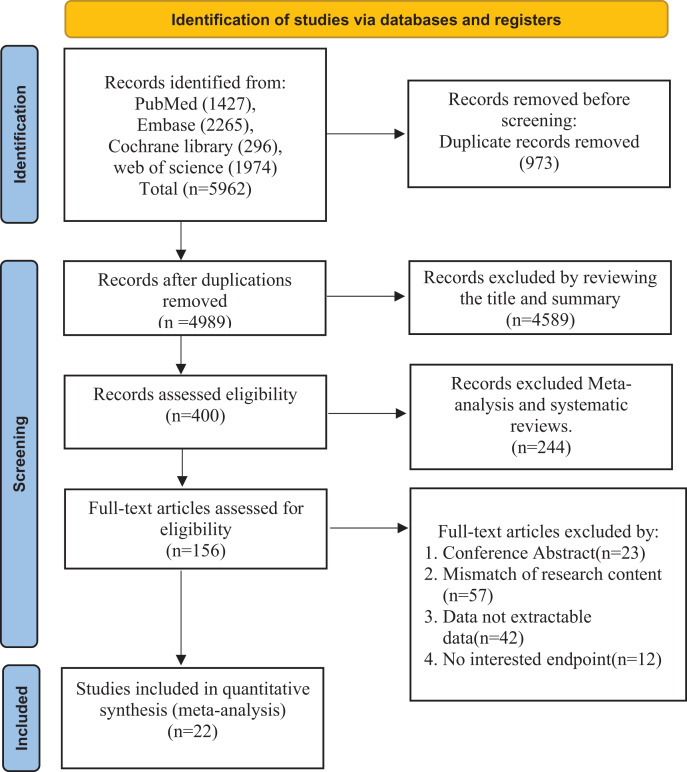

During the literature search, a total of 5,962 records were identified from the above databases. The first step was to exclude 973 duplicate articles. In the second step, after screening the abstracts and titles, 4,589 records were excluded. Subsequently, we excluded meta-analyses and systematic reviews. Finally, 22 studies (Ahmed et al., 2020; Cadiot et al., 2011; Chang et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2009; Cremonini et al., 2009; Emilsson et al., 2022; Fass et al., 2005; Ha et al., 2023; Horsley-Silva et al., 2019; Hyun, Baek & Lee, 2019; Jansson et al., 2009; Ju et al., 2013; Lei et al., 2019; Lindam et al., 2012, 2016; Murase et al., 2014; Okuyama et al., 2017; Wallander et al., 2007; Yadegarfar et al., 2018; You et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2012a, 2012b) were included in our meta-analysis after excluding literature with unrelated outcomes, conference abstracts, and literature from which data could not be extracted. The selection process is illustrated in the Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Studies screening process.

Study characteristics

Of the 22 studies (Ahmed et al., 2020; Cadiot et al., 2011; Chang et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2009; Cremonini et al., 2009; Emilsson et al., 2022; Fass et al., 2005; Ha et al., 2023; Horsley-Silva et al., 2019; Hyun, Baek & Lee, 2019; Jansson et al., 2009; Ju et al., 2013; Lei et al., 2019; Lindam et al., 2012, 2016; Murase et al., 2014; Okuyama et al., 2017; Wallander et al., 2007; Yadegarfar et al., 2018; You et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2012a, 2012b) that were included, 14 were case-control and eight were cohort studies, spanning from 2005 to 2023. Table 1 (Ahmed et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2021; Emilsson et al., 2022; Fass et al., 2005; Jansson et al., 2009; Ju et al., 2013; Lindam et al., 2012, 2016; Yadegarfar et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2012a, 2012b) presents the characteristics of the 11 included studies with GERD as an outcome. In these studies, risk factors identified for GERD included sleep disturbance, short sleep duration and insomnia. Eight of these articles (Ahmed et al., 2020; Emilsson et al., 2022; Jansson et al., 2009; Ju et al., 2013; Lindam et al., 2012, 2016; Zhang et al., 2012a, 2012b) adjusted for confounders such as sex and age. Table 2 (Cadiot et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2009; Cremonini et al., 2009; Ha et al., 2023; Horsley-Silva et al., 2019; Hyun, Baek & Lee, 2019; Lei et al., 2019; Murase et al., 2014; Okuyama et al., 2017; Wallander et al., 2007; You et al., 2015), outlines basic information from the literature covering sleep problems, which includes poor sleep quality, short sleep duration, and sleep disturbance. Of the studies (Cadiot et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2009; Cremonini et al., 2009; Ha et al., 2023; Horsley-Silva et al., 2019; Hyun, Baek & Lee, 2019; Lei et al., 2019; Murase et al., 2014; Okuyama et al., 2017; Wallander et al., 2007; You et al., 2015) focusing on sleep problems as an outcome, six (Cremonini et al., 2009; Ha et al., 2023; Horsley-Silva et al., 2019; Hyun, Baek & Lee, 2019; Wallander et al., 2007; You et al., 2015) controlled for confounders such as gender, age, and drinking history.

Table 1. Basic information on the included literature with gastroesophageal reflux disease as an outcome.

| Author | Year | Country | Study type | Exposure size | Normal size | Age (years) | Sleep problem type | Confounders adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jansson et al. | 2009 | Norway | Case-control | 3,153 | 40,210 | 19–81+ | Insomnia, Sleep disturbance | Age, sex, smoking, BMI, SES, anxiety, depression, myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, stroke, nausea, diarrhea, constipation |

| Emilsson et al. | 2022 | Sweden | Cohort study | 839 | 4,872 | Exposure: 29–57; Normal: 39–67 | Short Sleep Duration | Age, BMI, smoking status, caffeine consumption, alcohol dependence, physical activity level, depression, anxiety, snoring |

| Lindam et al. | 2012 | Sweden | Case-control | 1,327 | 6,687 | 65–75+ | Insomnia, Sleep disturbance | Age, sex, educational level, BMI, smoking |

| Zhang et al. | 2012a | Hong Kong | Cohort study | 185 | 2,106 | Mean (SD): 41.1 (5.4) | Sleep disturbance | Age, gender, education level, marital status, family income, regular use of medication(s), subtypes of insomnia, snoring, sleep duration |

| Ahmed et al. | 2020 | Pakistan | Case-control | 1,000 | 1,000 | Exposure: mean (SD): 30 (10.47); Normal: mean (SD): 44.73 (13.92) | Short Sleep Duration | Age, gender, BMI |

| Lindam et al. | 2016 | Norway | Cohort study | Total: 16,754 | Mean (SD): 43 (12) | Insomnia, Sleep disturbance | Sex, age, BMI, smoking, education, anxiety, depression | |

| Yadegarfar et al. | 2018 | Iran | Case-control | 717 | 308 | Exposure: mean (SD): 39.1 (9.6) Normal: mean (SD): 39.93 (10.7) | Short Sleep Duration | |

| Zhang et al. | 2012b | Hong Kong | Cohort study | 115 | 2,036 | Mean (SD): 46.3 (5.1) | Insomnia | Age, gender, education level, family income, regular use of medication |

| Fass et al. | 2005 | USA | Cohort study | 6,369 | 15,699 | Exposure: mean (SD): 62.9 (10.9) Normal: mean (SD): 63.6 (10.4) | Insomnia | |

| Ju et al. | 2013 | Korean | Case-control | 21 | 513 | Exposure: mean (SD): 50.8 (13.69) Normal: mean (SD): 50.95 (13.51) | Insomnia | Age, sex, alcohol consumption, BMI, depressed mood |

| Chang et al. | 2021 | Taiwan | Case-control | 401 | 2,249 | ≤30 3.4% 31–60 71.6% >60 25.0% |

Sleep disturbance |

Table 2. Basic information on the included literatures with three types of sleep problem as an outcome.

| Author | Year | Country | Study type | Exposure size | Normal size | Age (years) | Sleep problem type | Confounders adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horsley-Silva et al. | 2019 | USA | Case-control | Total 16,754 | Mean (SD): 59 (14) | Poor Sleep Quality | Age, sex, BMI, narcotic, antidepressant use | |

| Ha et al. | 2023 | USA | Cohort study | 7,726 | 28,911 | 48–69 | Poor Sleep Quality; Sleep disturbance; Short sleep duration | Age, BMI, menopausal status or menopausal hormone use, smoking status, race, presence of cancer, congestive heart failure, diabetes, asthma, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, depression, self-reported depression and anxiety symptoms, urinary incontinence, hot flushing, alcohol consumption, intake of caffeinated beverage, decaffeinated beverage, physical activity, diuretics use, proton pump inhibitor histamine-2 receptor antagonist use |

| Okuyama et al. | 2017 | Japan | Case-control | 483 | 1,253 | Exposure: mean (SD): 59.8 (12.1)Normal: mean (SD): 61.6 (2.0) | Sleep disturbance | |

| Hyun, Baek & Lee | 2019 | Korea | Case-control | 844 | 4,948 | Exposure: mean (SD): 61.99 (9.64)Normal: mean (SD): 64.06 (10.15) | Sleep disturbance | Gender, age, marital status, education level, tobacco, alcohol, physical activity, obesity, abdominal pains, heartburn, acid regurgitation, sucking sensations in the epigastrium, nausea and vomiting, borborygmus, abdominal distension and eructation |

| Chen et al. | 2009 | Taiwan | Case-control | 653 | 3,010 | Mean (SD): 50.6 (11.83) | Poor sleep quality; Short sleep duration | |

| Murase et al. | 2014 | Japan | Cohort study | Total: 8,614 | Mean (SD): 56 (13) | Short sleep duration | ||

| Wallander et al. | 2007 | U. K | Case-control | 12,437 | 18,350 | 20–79 | Sleep disturbance | Gender, age, Smoking status, BMI, alcohol consumption |

| You et al. | 2015 | Taiwan | Cohort study | 3,813 | 15,252 | 35–65.7 | Sleep disturbance | Age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, malignancy, income and urbanist |

| Lei et al. | 2019 | Taiwan | Case-control | 956 | 1,718 | Exposure: mean (SD): 53.33 (11.3)Normal: mean (SD): 52.04 (10.98) | Sleep disturbance | |

| Cremonini et al. | 2009 | U.S.A | Case-control | 542 | 2,686 | Exposure: mean (SD): 51.5 (0.7)Normal: mean (SD): 53 (0.3) | Sleep disturbance | Age, gender, smoking status, alcohol use, mental health status score |

| Cadiot et al. | 2011 | France | Case-control | Total 33,391 | Sleep disturbance |

Quality assessment

According to NOS criteria, the quality score of cohort studies ranged from five to nine, with an average score of 6.55 (Table S1). Out of the included articles, 16 scored between six and eight, and only one article achieved the maximum score of 9. This suggests that the bulk of the studies included in the meta-analysis were deemed moderate to high quality.

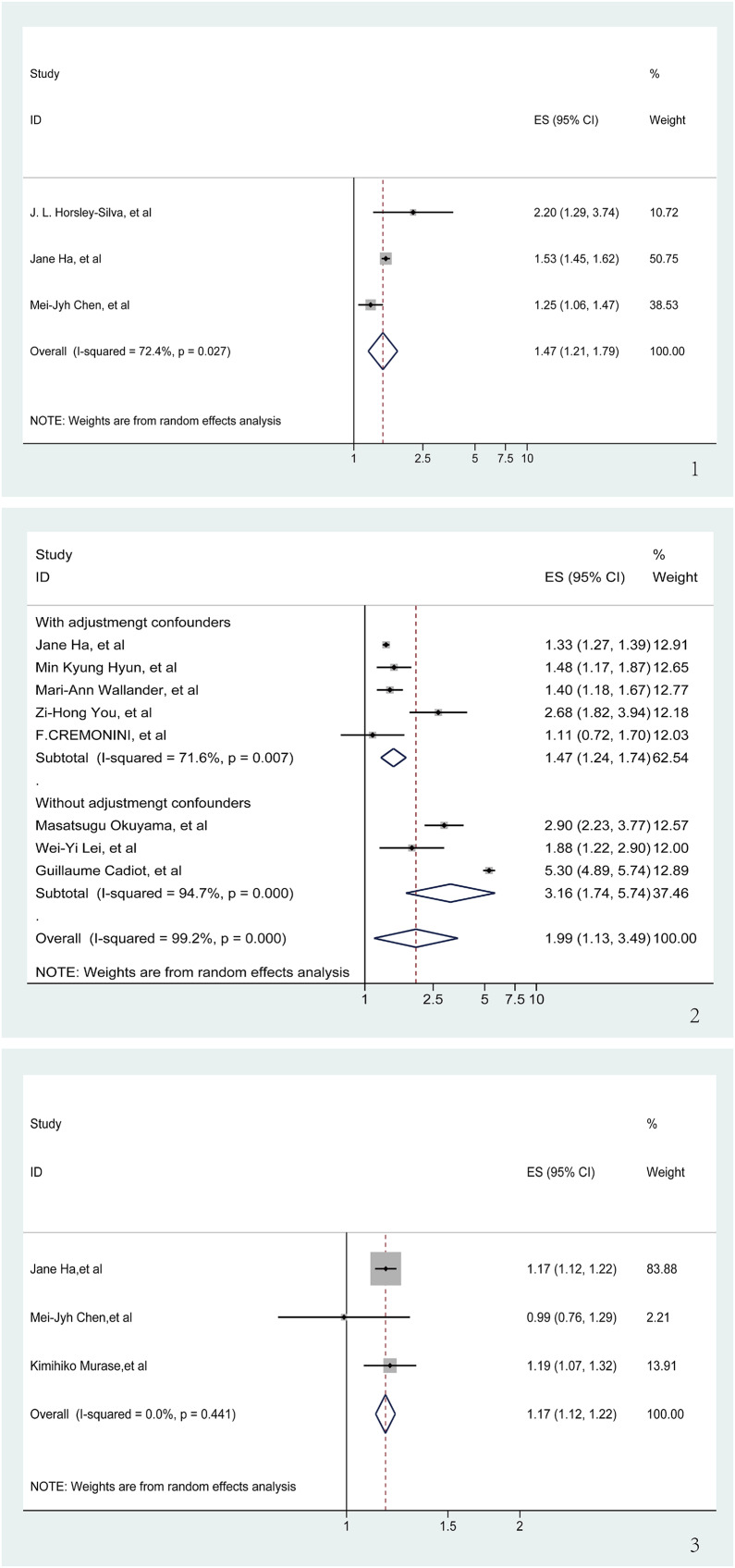

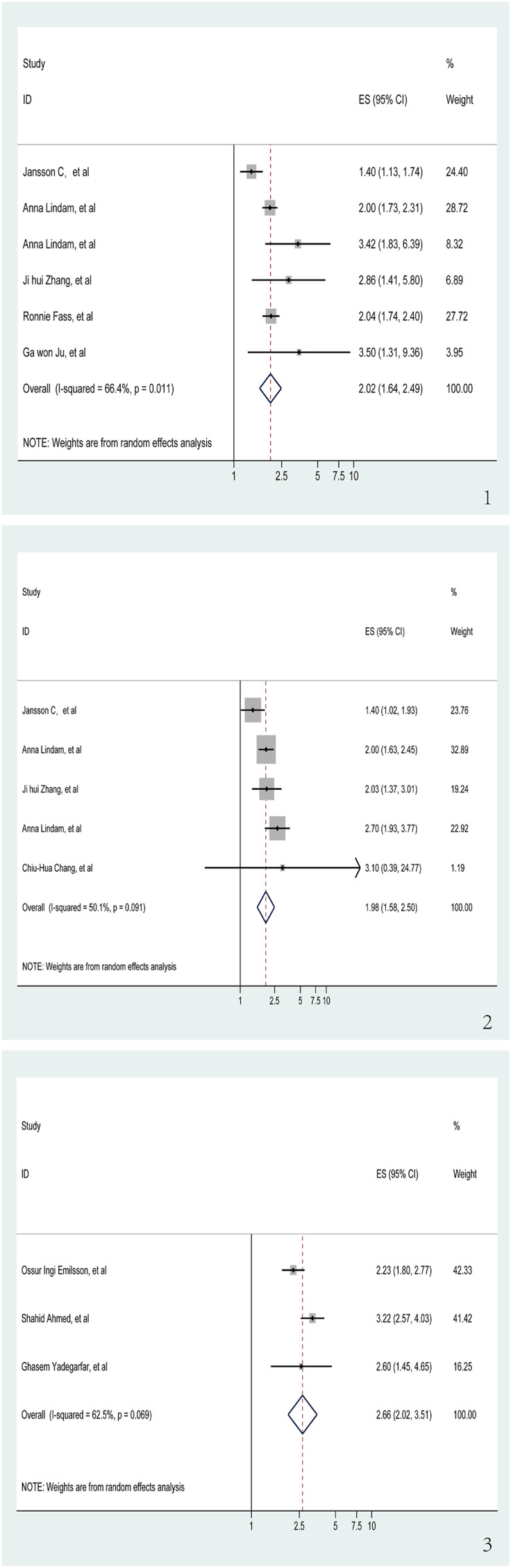

Insomnia and risk of GERD

We investigated the relationship between insomnia and GERD risk in six trials (Fass et al., 2005; Jansson et al., 2009; Ju et al., 2013; Lindam et al., 2012, 2016; Zhang et al., 2012b), which included three cohort studies and three case-control studies. The aggregated data revealed that a history of insomnia was associated with an increased risk of GERD in the pooled analysis (OR = 2.02, 95% CI [1.64–2.49], p < 0.001; I2 = 66.4%, z = 6.62; Fig. 2.1). Sensitivity analysis showed that none of the individual studies had a reversal of the pool effect size. That means the results are robust (Fig. S1).

Figure 2. Meta-analysis of the risk of GERD associated with sleep problems.

(1) Meta-analysis of the risk of GERD associated with insomnia. (2) Meta-analysis of the risk of GERD associated with sleep disturbance. (3) Meta-analysis of the risk of GERD associated with short sleep duration (Jansson et al., 2009; Lindam et al., 2012, 2016; Zhang et al., 2012b; Fass et al., 2005; Ju et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2012a; Chang et al., 2021; Emilsson et al., 2022; Ahmed et al., 2020; Yadegarfar et al., 2018).

Sleep disturbance and risk of GERD

The association between sleep disturbance and GERD, which was analyzed in five studies (Chang et al., 2021; Jansson et al., 2009; Lindam et al., 2012, 2016; Zhang et al., 2012a), was highly significant. The OR was 1.98 (95% CI [1.58–2.50], p < 0.001) in these trials that looked at the relationship between sleep disturbance and GERD (Fig. 2.2). I2 of the meta-analysis was 50.1% (z = 5.84). Sensitivity analysis upheld the reliability of these findings, showing no individual study caused a significant change in the pooled effect size, which validates that the results are robust (Fig. S2).

Short sleep duration and risk of GERD

Out of the studies selected for evaluating the association between GERD and short sleep duration, three (Ahmed et al., 2020; Emilsson et al., 2022; Yadegarfar et al., 2018) showed significant results (OR = 2.66, 95% CI [2.02–3.15], p < 0.001; I2 = 62.5%, z = 6.92; Fig. 2.3). Sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of the results, as no individual study caused a reversal of the pooled effect size (Fig. S3).

GERD and risk of poor sleep quality

During the meta-analysis concerning GERD and poor sleep quality, three publications (Chen et al., 2009; Ha et al., 2023; Horsley-Silva et al., 2019) yielded significant findings (OR = 1.47, 95% CI [1.47–1.79], p < 0.001; I2 = 72.4%, z = 3.89; Fig. 3.1). Sensitivity analysis demonstrated the stability of these results since none of the individual studies reversed the pooled effect size (Fig. S4).

Figure 3. Meta-analysis of the risk of sleep problems associated with GERD.

(1) Meta-analysis of the risk of poor sleep quality associated with GERD. (2) Meta-analysis of the risk of sleep disturbance associated with GERD. (3) Meta-analysis of the risk of short sleep duration associated with GERD (Horsley-Silva et al., 2019; Ha et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2009; Hyun, Baek & Lee, 2019; Wallander et al., 2007; You et al., 2015; Cremonini et al., 2009; Okuyama et al., 2017; Lei et al., 2019; Cadiot et al., 2011; Ha et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2009; Murase et al., 2014).

GERD and risk of Sleep disturbance

Eight articles (Cadiot et al., 2011; Cremonini et al., 2009; Ha et al., 2023; Hyun, Baek & Lee, 2019; Lei et al., 2019; Okuyama et al., 2017; Wallander et al., 2007; You et al., 2015) were reviewed to determine the risk of sleep disturbance associated with GERD. In spite of a significant OR (OR = 1.99, 95% CI [1.13–3.49], p < 0.001), there was a high degree of heterogeneity between the articles (I2 = 99.2%, z = 2.39; Fig. S5), and sensitivity analyses showed that none of the individual studies had a significant impact on the results of the meta-analysis (Fig. S6). It is noteworthy that three (Cadiot et al., 2011; Lei et al., 2019; Okuyama et al., 2017) of these eight articles did not adjust for confounders in the study population during the course of the study. Regression analysis, applied to derive a p-value for the comparison between the two groups, was significant (p = 0.038). Consequently, only studies adjusting for confounders were analyzed (Cremonini et al., 2009; Ha et al., 2023; Hyun, Baek & Lee, 2019; Wallander et al., 2007; You et al., 2015). Accounting for adjusting confounders significantly reduced the aforementioned heterogeneity (I2 from 99.2% to 71.6%), and a significant link between GERD and the risk of developing sleep disturbance was re-affirmed (OR = 1.47, 95% CI [1.24–1.74], p < 0.001; Fig. 3.2).

GERD and risk of short sleep duration

An analysis of three articles (Chen et al., 2009; Ha et al., 2023; Murase et al., 2014) examining the correlation between GERD and short sleep duration demonstrated a clear association. There was no significant heterogeneity between the three included articles (I2 = 0, z = 7.79). Therefore, we decided to use fixed effects for our meta-analyses. The pooling analysis shows that a history of GERD corresponds with an increased risk of short sleep duration (OR = 1.17, 95% CI [1.12–1.21], p < 0.001; Fig. 3.3). Subsequent sensitivity analyses bolstered these findings, with no individual study significantly influencing the meta-analysis results (Fig. S7).

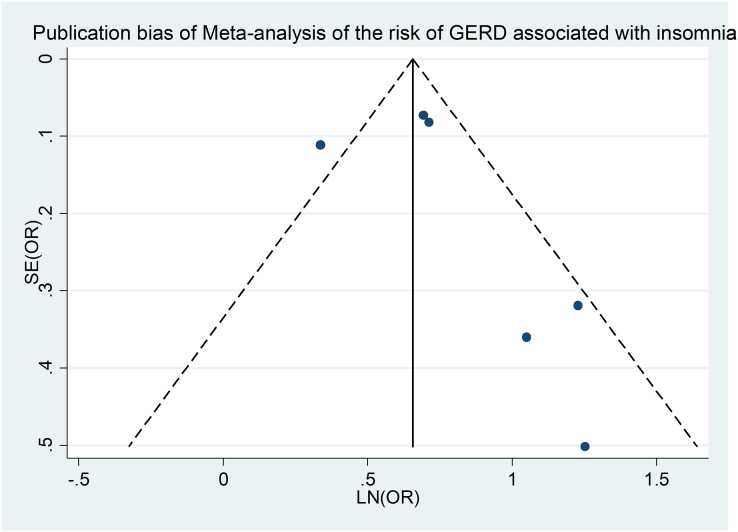

Publication bias

Our investigation into publication bias involved examining funnel plots across different subgroups and conducting Egger’s regression test for statistical verification. Figure 4 is a funnel plot of the meta-analysis of insomnia and the risk of GERD (Fass et al., 2005; Jansson et al., 2009; Ju et al., 2013; Lindam et al., 2012, 2016; Zhang et al., 2012b), and the Egger’s regression test (p = 0.038) also showed no significant publication bias in our meta-analysis. Similar methodology was applied for testing publication bias for additional outcomes, revealing no evidence of bias (Table S2).

Figure 4. Publication bias of meta-analysis of the risk of GERD associated with insomnia.

Discussion

This meta-analysis incorporating 22 studies thoroughly addressed the bidirectional relationship between GERD and sleep problems. We found a significant higher risk of poor sleep quality, short sleep duration, or sleep disturbance in individuals with GERD, with the respective risks increased by 1.47-fold, 1.17-fold and 1.47-fold compared to healthy counterparts. Meanwhile, the risk of GERD is notably higher in those with insomnia, short sleep duration, or sleep disturbances, with risks higher by 1.5, 2.66, or 1.98, respectively. These findings highlight the significance of early recognition of GERD and its sleep-related comorbidities for better clinical outcomes.

A previous meta-analysis examined the relationship between sleep problems and their comorbidities, including GERD (Huang et al., 2022). The study with a focus on first responders, showed insomnia increased the risk of depression and anxiety. Though it included GERD data, it lacked definitive insights on the link between insomnia and GERD, potentially due to the targeted population. To fill this research void, we expanded our scope and performed a more comprehensive analysis based on types of sleep problems, substantiating a strong association between insomnia, short sleep duration, sleep disturbance, and GERD. Another prior review posited GERD as a potential indicator of insomnia and sleep initiation issues (Jung, Choung & Talley, 2010). However, it did not conclusively infer an increased risk for these sleep problems. In contrast, our statistical analysis clearly revealed that GERD indeed increases the risk of poor sleep quality, short sleep duration, and sleep disturbance.

Both GERD and sleep problems are common. A cross-sectional study of 11,685 GERD patients found them more susceptible to sleep problems (Mody et al., 2009). Another previous case-control study showed that patients with sleep problems had significantly higher rates of reflux symptoms than healthy people (Orr et al., 2008). GERD is a multifactorial chronic condition with symptoms arising from gastric content reflux. The 24-h esophageal pH test, used in GERD diagnosis (Gyawali et al., 2018), shows patients typically exhibiting increased acid reflux frequency, reduced esophageal impedance, and prolonged mucosal recovery time (Woodland et al., 2013). Its pathogenesis involves esophagogastric junction incompetence, acid erosion, helicobacter pylori infection, hiatal hernia, and chronic inflammation (Katzka & Kahrilas, 2020). These factors together suggest that a single conventional theory cannot fully account for the coexistence of GERD and sleep issues. Therefore, we propose instead that a multitude of pathogenic mechanisms contribute to their concurrent emergence.

The underlying mechanisms of the reciprocal influence between gastroesophageal reflux disease and sleep disturbances remains poorly understood. The TRPV1 and melatonin pathways may play significant roles in this interplay. TRPV1, an acid-sensitive receptor, is activated by both capsaicin and heat and is present in the esophageal mucosa epithelial cells, which produces a burning sensation during acid reflux (Ma et al., 2012). Studies have identified TRPV1 expression in the hypothalamus (Jeong et al., 2018). Research by Liu & Tian (2023) elucidated TRPV1’s involvement in sleep-wake cycles through experiments involving capsaicin administration in animal subjects. Sustained acid-mucosal contact may have an initiating effect on central nervous system arousal mechanisms. At the same time, evidence suggests that poor sleep quality can exacerbate reflux incidents and increase acid contact time (Hung et al., 2016). Total sleep deprivation has been shown to induce esophageal hyperalgesia, a condition observable in the acid perfusion test (Onen et al., 2001). This acid reflux abnormality can induce esophageal pain and consequently disrupt sleep, while simultaneous sleep deprivation can intensify esophageal sensitivity and aggravate this effect. Hormonal changes could influence both GERD and sleep issues. It is well known that sleep problems can directly affect sleep rhythms. Melatonin, derived from L-tryptophan, is synthesized in the pineal gland and operates under the regulation of sleep rhythms (Majka et al., 2018). This hormone acts to reduce transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations by suppressing nitric oxide biosynthesis, thus potentially mitigating GERD morbidity (Pereira, 2006), which may elucidate the link between sleep problems and GERD. Furthermore, psychological aspects are influential; GERD symptoms could predispose individuals to psychiatric conditions, including depression (Núñez-Rodríguez & Miranda Sivelo, 2008). In cases of GERD, mucosal damage results from a combination of inflammatory and immune factors (Kandulski & Malfertheiner, 2011), both of which have been implicated in depression (Slavich & Irwin, 2014). A meta-analysis puts forward that sleep problems can double the risk of depression or even herald its onset (Baglioni et al., 2011). Thus, depression might act as a mediator between GERD and sleep issues, with inflammation being a significant contributor. In summary, the association between GERD and sleep disturbances is complex and mutual, challenging simple explanations offered by traditional theories.

Implications and limitations

Our study synthesizes the existing evidence on the relationship between GERD and sleep problems, demonstrating their bilateral influence. It emphasizes the need to consider the risk of sleep problems in patients with GERD as well as recognizing that those with sleep problems are more prone to GERD symptoms. These conclusions inform clinical practice. Confirming the bidirectional association between GERD and sleep problems offers a foundational basis for further clinical research. Future studies could explore the causative factors underlying the relationship between GERD and sleep problems. Healthcare providers should be aware that GERD may coexist with sleep problems, prompting consideration for combined treatment strategies to improve therapeutic outcomes.

Nonetheless, this study is not without limitations. The use of multiple diagnostic criteria for sleep problems introduces variability, and future studies should strive for standardized inclusion criteria. The study’s use of clinical symptoms as inclusion criteria, rather than objective clinical examination, may have resulted in the exclusion of some patients who were asymptomatic. The inclusion of cohort and case-control studies instead of randomized controlled studies may lead to heterogeneity. Perhaps due to the presence of well-defined diagnostic criteria and clinical indicators for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), as opposed to other sleep problems diagnosed primarily through medical history and questionnaires, there is a scarcity of research concurrently investigating gastroesophageal reflux, OSA, and other sleep problems. Therefore, this study did not include OSA as a focal point of investigation. In addition, we did not include covariate analysis in this study. Although most of the literatures we included had been adjusted for confounders, differences in the adjustment for confounders between the articles are still likely to have an impact on the results. While previous studies have established an association between GERD and esophageal hiatal hernia (Jones et al., 2001), we did not incorporate it as a confounding factor due to insufficient relevant data, potentially introducing bias. Finally, some articles in the meta-analysis scored lower on quality assessment. Future research should include high-quality prospective cohort studies to ensure more reliable results.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis indicates that GERD elevates the risk of insomnia, short sleep duration, or sleep disturbance. Conversely, poor sleep quality, short sleep duration, or sleep disturbance independently pose a risk for GERD. Our findings underscore the importance for healthcare practitioners to be vigilant regarding the correlation between GERD and sleep disturbances in clinical settings.

Supplemental Information

Funding Statement

The authors received no funding for this work.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Xiaolong Tan conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Shasha Wang performed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables, and approved the final draft.

Fengjie Wu analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, and approved the final draft.

Jun Zhu conceived and designed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

This is a systematic review/meta-analysis.

References

- Ahmed et al. (2020).Ahmed S, Jamil S, Shaikh H, Abbasi M. Effects of Life style factors on the symptoms of gastro esophageal reflux disease: a cross sectional study in a Pakistani population. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 2020;36(2):115–120. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.2.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglioni et al. (2011).Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, Spiegelhalder K, Nissen C, Voderholzer U, Lombardo C, Riemann D. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;135(1–3):10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigal & Lipton (2006).Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Modifiable risk factors for migraine progression. Headache. 2006;46(9):1334–1343. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadiot et al. (2011).Cadiot G, Delaage P-H, Fabry C, Soufflet C, Barthélemy P. Sleep disturbances associated with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: prevalence and impact of treatment in French primary care patients. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2011;43(10):784–787. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang et al. (2021).Chang C-H, Chen T-H, Chiang L-LL, Hsu C-L, Yu H-C, Mar G-Y, Ma C-C. Associations between lifestyle habits, perceived symptoms and gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients seeking health check-ups. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(7):3808. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen et al. (2009).Chen M-J, Wu M-S, Lin J-T, Chang K-Y, Chiu H-M, Liao W-C, Chen C-C, Lai Y-P, Wang H-P, Lee Y-C. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and sleep quality in a Chinese population. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association = Taiwan Yi Zhi. 2009;108(1):53–60. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremonini et al. (2009).Cremonini F, Camilleri M, Zinsmeister AR, Herrick LM, Beebe T, Talley NJ. Sleep disturbances are linked to both upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms in the general population. Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 2009;21(2):128–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Berardis et al. (2013).De Berardis D, Marini S, Fornaro M, Srinivasan V, Iasevoli F, Tomasetti C, Valchera A, Perna G, Quera-Salva M-A, Martinotti G, di Giannantonio M. The melatonergic system in mood and anxiety disorders and the role of agomelatine: implications for clinical practice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013;14(6):12458–12483. doi: 10.3390/ijms140612458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger et al. (1997).Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Hage Chehade et al. (2023).El Hage Chehade N, Fu Y, Ghoneim S, Shah S, Song G, Fass R. Association between obstructive sleep apnea and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2023;38(8):1244–1251. doi: 10.1111/jgh.16245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emilsson et al. (2022).Emilsson ÖI, Al Yasiry H, Theorell-Haglöw J, Ljunggren M, Lindberg E. Insufficient sleep and new onset of nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux among women: a longitudinal cohort study. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2022;18(7):1731–1737. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eusebi et al. (2018).Eusebi LH, Ratnakumaran R, Yuan Y, Solaymani-Dodaran M, Bazzoli F, Ford AC. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2018;67(3):430–440. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fass et al. (2005).Fass R, Quan SF, O’Connor GT, Ervin A, Iber C. Predictors of heartburn during sleep in a large prospective cohort study. Chest. 2005;127(5):1658–1666. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaviano, Bazett-Jones & Boling (2022).Glaviano NR, Bazett-Jones DM, Boling MC. Pain severity during functional activities in individuals with patellofemoral pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2022;25(5):399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2022.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyawali et al. (2018).Gyawali CP, Kahrilas PJ, Savarino E, Zerbib F, Mion F, Smout AJPM, Vaezi M, Sifrim D, Fox MR, Vela MF, Tutuian R, Tack J, Bredenoord AJ, Pandolfino J, Roman S. Modern diagnosis of GERD: the Lyon Consensus. Gut. 2018;67(7):1351–1362. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha et al. (2023).Ha J, Mehta RS, Cao Y, Huang T, Staller K, Chan AT. Assessment of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and sleep quality among women in the nurses’ health study II. JAMA Network Open. 2023;6(7):e2324240. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.24240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins et al. (2003).Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clinical Research ed) 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsley-Silva et al. (2019).Horsley-Silva JL, Umar SB, Vela MF, Griffing WL, Parish JM, DiBaise JK, Crowell MD. The impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms in scleroderma: effects on sleep quality. Diseases of the Esophagus. 2019;32(5):330. doi: 10.1093/dote/doy136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu et al. (2024).Hu K-Y, Tseng P-H, Hsu W-C, Lee P-L, Tu C-H, Chen C-C, Lee Y-C, Chiu H-M, Wu M-S, Peng C-K. Association of subjective and objective sleep disturbance with the spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2024 doi: 10.5664/jcsm.11028. Epub ahead of print 1 February 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang et al. (2022).Huang G, Lee T-Y, Banda KJ, Pien L-C, Jen H-J, Chen R, Liu D, Hsiao S-TS, Chou K-R. Prevalence of sleep disorders among first responders for medical emergencies: a meta-analysis. Journal of Global Health. 2022;12(3):4092. doi: 10.7189/jogh.12.04092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung et al. (2016).Hung J-S, Lei W-Y, Yi C-H, Liu T-T, Chen C-L. Association between nocturnal acid reflux and sleep disturbance in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2016;352(2):141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun, Baek & Lee (2019).Hyun MK, Baek Y, Lee S. Association between digestive symptoms and sleep disturbance: a cross-sectional community-based study. BMC Gastroenterology. 2019;19(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s12876-019-0945-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson et al. (2009).Jansson C, Nordenstedt H, Wallander M-A, Johansson S, Johnsen R, Hveem K, Lagergren J. A population-based study showing an association between gastroesophageal reflux disease and sleep problems. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2009;7(9):960–965. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong et al. (2018).Jeong JH, Lee DK, Liu S-M, Chua SC, Schwartz GJ, Jo Y-H. Activation of temperature-sensitive TRPV1-like receptors in ARC POMC neurons reduces food intake. PLOS Biology. 2018;16(4):e2004399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2004399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones et al. (2001).Jones MP, Sloan SS, Rabine JC, Ebert CC, Huang CF, Kahrilas PJ. Hiatal hernia size is the dominant determinant of esophagitis presence and severity in gastroesophageal reflux disease. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2001;96(6):1711–1717. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju et al. (2013).Ju G, Yoon I-Y, Lee SD, Kim N. Relationships between sleep disturbances and gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asian sleep clinic referrals. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2013;75(6):551–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Choung & Talley (2010).Jung H-K, Choung RS, Talley NJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and sleep disorders: evidence for a causal link and therapeutic implications. Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 2010;16(1):22–29. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2010.16.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandulski & Malfertheiner (2011).Kandulski A, Malfertheiner P. Gastroesophageal reflux disease—from reflux episodes to mucosal inflammation. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2011;9(1):15–22. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzka & Kahrilas (2020).Katzka DA, Kahrilas PJ. Advances in the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. BMJ. 2020;371:m3786. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei et al. (2019).Lei W-Y, Chang W-C, Wong M-W, Hung J-S, Wen S-H, Yi C-H, Liu T-T, Chen J-H, Hsu C-S, Hsieh T-C, Chen C-L. Sleep disturbance and its association with gastrointestinal symptoms/diseases and psychological comorbidity. Digestion. 2019;99(3):205–212. doi: 10.1159/000490941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei et al. (2022).Lei S, Li X, Zhao H, Feng Z, Chun L, Xie Y, Li J. Risk of dementia or cognitive impairment in sepsis survivals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2022;14:839472. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.839472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindam et al. (2012).Lindam A, Jansson C, Nordenstedt H, Pedersen NL, Lagergren J. A population-based study of gastroesophageal reflux disease and sleep problems in elderly twins. PLOS ONE. 2012;7(10):e48602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindam et al. (2016).Lindam A, Ness-Jensen E, Jansson C, Nordenstedt H, Åkerstedt T, Hveem K, Lagergren J. Gastroesophageal reflux and sleep disturbances: a bidirectional association in a population-based cohort study, the HUNT study. Sleep. 2016;39(7):1421–1427. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu & Tian (2023).Liu L, Tian Y. Capsaicin changes the pattern of brain rhythms in sleeping rats. Molecules. 2023;28:4736. doi: 10.3390/molecules28124736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu et al. (2016).Liu Y, Wheaton AG, Chapman DP, Cunningham TJ, Lu H, Croft JB. Prevalence of healthy sleep duration among adults—United States, 2014. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2016;65(6):137–141. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6506a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma et al. (2012).Ma J, Altomare A, Guarino M, Cicala M, Rieder F, Fiocchi C, Li D, Cao W, Behar J, Biancani P, Harnett KM. HCl-induced and ATP-dependent upregulation of TRPV1 receptor expression and cytokine production by human esophageal epithelial cells. American Journal of Physiology Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2012;303(5):G635–G645. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00097.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majka et al. (2018).Majka J, Wierdak M, Brzozowska I, Magierowski M, Szlachcic A, Wojcik D, Kwiecien S, Magierowska K, Zagajewski J, Brzozowski T. Melatonin in prevention of the sequence from reflux esophagitis to Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma: experimental and clinical perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018;19(7):20033. doi: 10.3390/ijms19072033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mody et al. (2009).Mody R, Bolge SC, Kannan H, Fass R. Effects of gastroesophageal reflux disease on sleep and outcomes. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2009;7(9):953–959. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murase et al. (2014).Murase K, Tabara Y, Takahashi Y, Muro S, Yamada R, Setoh K, Kawaguchi T, Kadotani H, Kosugi S, Sekine A, Nakayama T, Mishima M, Chiba T, Chin K, Matsuda F. Gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms and dietary behaviors are significant correlates of short sleep duration in the general population: the Nagahama study. Sleep. 2014;37(11):1809–1815. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Núñez-Rodríguez & Miranda Sivelo (2008).Núñez-Rodríguez MH, Miranda Sivelo A. Psychological factors in gastroesophageal reflux disease measured by SCL-90-R questionnaire. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2008;53(12):3071–3075. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuyama et al. (2017).Okuyama M, Takaishi O, Nakahara K, Iwakura N, Hasegawa T, Oyama M, Inoue A, Ishizu H, Satoh H, Fujiwara Y. Associations among gastroesophageal reflux disease, psychological stress, and sleep disturbances in Japanese adults. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2017;52(1):44–49. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2016.1224383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- On et al. (2017).On ZX, Grant J, Shi Z, Taylor AW, Wittert GA, Tully PJ, Hayley AC, Martin S. The association between gastroesophageal reflux disease with sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in a cohort study of Australian men. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2017;32(6):1170–1177. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onen et al. (2001).Onen SH, Alloui A, Gross A, Eschallier A, Dubray C. The effects of total sleep deprivation, selective sleep interruption and sleep recovery on pain tolerance thresholds in healthy subjects. Journal of Sleep Research. 2001;10(1):35–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2001.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr et al. (2008).Orr WC, Goodrich S, Fernström P, Hasselgren G. Occurrence of nighttime gastroesophageal reflux in disturbed and normal sleepers. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2008;6(10):1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page et al. (2021).Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peery et al. (2019).Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC, Lund JL, Dellon ES, Williams JL, Jensen ET, Shaheen NJ, Barritt AS, Lieber SR, Kochar B, Barnes EL, Fan YC, Pate V, Galanko J, Baron TH, Sandler RS. Burden and cost of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic diseases in the United States: update 2018. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(1):254–272.e11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira (2006).Pereira RDS. Regression of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms using dietary supplementation with melatonin, vitamins and aminoacids: comparison with omeprazole. Journal of Pineal Research. 2006;41(3):195–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy et al. (2023).Pomeroy A, Pagan Lassalle P, Kline CE, Heffernan KS, Meyer ML, Stoner L. The relationship between sleep duration and arterial stiffness: a meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2023;70:101794. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2023.101794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasankan & Thota (2022).Sasankan P, Thota PN. Evaluation and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a brief look at the updated guidelines. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 2022;89:700–703. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.89a.22059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoib et al. (2022).Shoib S, Ullah I, Nagendrappa S, Taseer AR, De Berardis D, Singh M, Asghar MS. Prevalence of mental illness in patients with obstructive sleep apnea—a cross-sectional study from Kashmir, India. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2022;80:104056. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavich & Irwin (2014).Slavich GM, Irwin MR. From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: a social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140(3):774–815. doi: 10.1037/a0035302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suganuma et al. (2001).Suganuma N, Shigedo Y, Adachi H, Watanabe T, Kumano-Go T, Terashima K, Mikami A, Sugita Y, Takeda M. Association of gastroesophageal reflux disease with weight gain and apnea, and their disturbance on sleep. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2001;55(3):255–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2001.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun et al. (2023).Sun L, Zhang J, Li W, Sheng J, Xiao S. Neutrophil activation may trigger tau burden contributing to cognitive progression of chronic sleep disturbance in elderly individuals not living with dementia. BMC Medicine. 2023;21:205. doi: 10.1186/s12916-023-02910-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunwoo & Owens (2022).Sunwoo BY, Owens RL. Sleep deficiency, sleep apnea, and chronic lung disease. Clinics in Chest Medicine. 2022;43(2):337–352. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2022.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Mahtani & Aronson (2021).Taylor KS, Mahtani KR, Aronson JK. Summarising good practice guidelines for data extraction for systematic reviews and meta-analysis. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine. 2021;26(3):88–90. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vakil et al. (2006).Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006;101(8):1900–1920. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallander et al. (2007).Wallander M-A, Johansson S, Ruigómez A, García Rodríguez LA, Jones R. Morbidity associated with sleep disorders in primary care: a longitudinal cohort study. Primary Care Companion To the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2007;9(05):338–345. doi: 10.4088/PCC.v09n0502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodland et al. (2013).Woodland P, Al-Zinaty M, Yazaki E, Sifrim D. In vivo evaluation of acid-induced changes in oesophageal mucosa integrity and sensitivity in non-erosive reflux disease. Gut. 2013;62(9):1256–1261. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadegarfar et al. (2018).Yadegarfar G, Momenyan S, Khoobi M, Salimi S, Sheikhhaeri A, Farahabadi M, Heidari S. Iranian lifestyle factors affecting reflux disease among healthy people in Qom. Electronic Physician. 2018;10(4):6718–6724. doi: 10.19082/6718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki, Quan & Fass (2019).Yamasaki T, Quan SF, Fass R. The effect of sleep deficiency on esophageal acid exposure of healthy controls and patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 2019;31(12):e13705. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You et al. (2015).You Z-H, Perng C-L, Hu L-Y, Lu T, Chen P-M, Yang AC, Tsai S-J, Huang Y-S, Chen H-J. Risk of psychiatric disorders following gastroesophageal reflux disease: a nationwide population-based cohort study. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2015;26(7):534–539. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamani et al. (2023).Zamani M, Alizadeh-Tabari S, Chan WW, Talley NJ. Association between anxiety/depression and gastroesophageal reflux: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2023;118(12):2133–2143. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. (2012a).Zhang J, Lam S-P, Li SX, Li AM, Wing Y-K. The longitudinal course and impact of non-restorative sleep: a five-year community-based follow-up study. Sleep Medicine. 2012a;13(6):570–576. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. (2012b).Zhang J, Lam SP, Li SX, Yu MWM, Li AM, Ma RCW, Kong APS, Wing YK. Long-term outcomes and predictors of chronic insomnia: a prospective study in Hong Kong Chinese adults. Sleep Medicine. 2012b;13(5):455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler (2003).Ziegler MG. Sleep disorders and the failure to lower nocturnal blood pressure. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 2003;12(1):97–102. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200301000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

This is a systematic review/meta-analysis.