Abstract

Dendritic cell (DC)-based immunotherapies have been created for a broad expanse of cancers, and DC vaccines prepared with Wilms’ tumor protein 1 (WT1) peptides have shown great therapeutic efficacy in these diseases. In this paper, we report the results of a phase I/II study of a DC-based vaccination for advanced breast, ovarian, and gastric cancers, and we offer evidence that patients can be effectively vaccinated with autologous DCs pulsed with WT1 peptide. There were ten patients who took part in this clinical study; they were treated biweekly with a WT1 peptide-pulsed DC vaccination, with toxicity and clinical and immunological responses as the principal endpoints. All of the adverse events to DC vaccinations were tolerable under an adjuvant setting. The clinical response was stable disease in seven patients. Karnofsky Performance Scale scores were enhanced, and computed tomography scans revealed tumor shrinkage in three of seven patients. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA)/WT1-tetramer and cytoplasmic IFN-γ assays were used to examine the induction of a WT-1-specific immune response. The immunological responses to DC vaccination were significantly correlated with fewer myeloid-derived suppressor cells (P = 0.045) in the pretreated peripheral blood. These outcomes offered initial clinical evidence that the WT1 peptide-pulsed DC vaccination is a potential treatment for advanced cancer.

Keywords: Dendritic cell, WT1, Tumor-associated antigens, Cytotoxic T lymphocytes, Immunotherapy

Introduction

As we continue to develop and enhance tumor immunotherapies, research has concentrated on particular immune reactions against tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) and their epitopes, which are identified by human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class-I-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) from different malignant neoplasms [1]. Of the currently determined TAAs, Wilms’ tumor gene product WT1 is noted as a causative gene of Wilms’ childhood renal tumors [2]. The WT1 gene encodes a zinc finger transcription factor that is overexpressed in numerous hematological malignancies and solid tumors [3–5]. Since WT1 is an intracellular protein that is not targeted by conventional monoclonal antibody therapies, generating WT1-specific CTL responses that recognize peptides presented on cell surfaces by HLA class-I molecules is a major goal for this therapy [6–8]. High WT1 is linked to poor prognosis for patients with various hematological malignancies and solid tumors, such as breast cancer [9, 10], ovarian cancer, and gastric adenocarcinoma [11–13]; with general 5-year survival rates in these cancers of approximately 90%, 47%, and 30%, respectively [14]. Therefore, WT1 could be a target antigen for immunotherapy for these types of cancers. WT1 is an appealing vaccine candidate due to its limited expression and its oncogenic functions.

A prior WT1 peptide vaccine was used for different solid tumors, [15, 16] and vaccination with dendritic cells (DCs) prepared with TAAs may be potential immunotherapeutics for carcinoma patients [17, 18]. Antigen-presenting cell-based immunotherapies with active DCs have been documented to prompt immunity, and while DC-based treatments against TAAs are “anti-idiotypic vaccines”, they are conceptually identical to other strategies with autologous monocyte-derived mature DCs to promote a tumor-specific immune reaction [19]. Further, the expression of cancer-associated antigens with HLA class-I and II antigens in tumor tissues could provide immunotherapy against cancers [20, 21]. Specifically, HLA-limited modified WT1 peptide, revealed by HLA-A*24:02 (amino acids 235–243 CYTWNQML), in which Y was substituted for M at amino acid position 2 of the natural WT1 peptide, were used for DC vaccines. The modified WT1 peptide elicits stronger tumor-recognizing cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity natural peptides and it induces immunological and clinical reactions [22, 23].

This novel DC-based vaccination strategy could be a beneficial therapy for advanced cancer [24–33]. Immunotherapies utilizing CTLs are central cancer immunotherapy [34]. We performed a phase I/II clinical study to examine the feasibility and efficacy of WT1-pulsed “mature” DC vaccinations in extremely pretreated metastatic breast, ovarian, and gastric cancer patients. We established the feasibility and capability of prompting WT1-specific CTLs, which led to cancer regression without the destruction of healthy tissues in the clinic.

Materials and methods

Objectives

This trial was a I/II clinical study. The planned sample size was ten. The primary endpoint was adverse events graded according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.0). The secondary endpoint was overall survival. The duration of overall survival was defined as the date patients’ informed consent was obtained to the date of death. Eligibility: patients aged 20–70 with gastric, ovarian or breast cancer were eligible if their disease was resistant to conventional chemotherapy or surgery. Other inclusion criteria were: (1) HLA-A*2402-positivity, (2) a score of 0 or 1 on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance scale; (3) estimated survival of > 2 months; (4) lesion that could be evaluated according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST); (5) no immediate allergy to the WT1 peptide; (6) no severe impairment of organ function, including hematologic, hepatic, renal and cardiac function.

Follow-up was conducted with clinical examinations to determine the efficacy of vaccine given together with typical neoadjuvant treatment. The Karnofsky Performance Scale was utilized to evaluate each patient at every visit, and tumor regression was determined according to RECIST to measure initial safety and immunogenicity data for the neoadjuvant therapy. Patients continued therapy unless progressive disease occurred, or they experienced unacceptable toxicity requiring cessation of treatment. If there was a change in medical status (including pregnancy), compromised patient safety, withdrawn consent, non-compliance, or a loss to follow-up, the treatment was stopped.

DC vaccination preparation

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were freshly isolated from patients, and DCs were generated from monocytes isolated with the MagCellect Human CD14+ Cell Isolation Kit (R&D Systems). The PBMCs were incubated at 37 °C, and adherent cells (composed of 96.1% ± 2.6% CD14+ monocytes) were cultured in AIM-V medium containing granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (1000 units/mL; PeproTech) and IL-4 (500 units/mL; R&D Systems) to generate immature DCs. After 6 days of incubation at 37 °C, the DC maturing agent TNF-α (500 units/mL; PeproTech) was added to the culture for 48 h. DC vaccine preparation is described in the literature [35]. Briefly, mature DCs were incubated with 100 µg/mL WT1 peptide for 30 min and washed with saline. The WT1 peptide (a modified-type, HLA-A*2402-restricted, 9-mer WT1 peptide residues 235–243: CYTWNQMNL) of good manufacturing practice grade was purchased from Multiple Peptide Systems (San Diego CA, USA) as lyophilized peptides.

Based on quality criteria for DC vaccines, the phenotypes CD11c+, CD40+, CD80+, CD83+, CD86+, CCR7+, and HLA-DR + were established as mature DCs. For every DC vaccination, about 1–2 × 107 DCs with OK-432 (1–2 KE, Chugai Pharmaceutical), a streptococcal primer, were injected intradermally into bilateral axillary parts on day 8 and at biweekly intervals for at least 5 sessions (1 course) based on detailed techniques for the clinical use of Cellular and Tissue-Based Products Manufacturing Products throughout a single chemotherapy regimen. If a positive response to treatment or no adverse effects were noted following a single vaccination course, more vaccinations were administered with the patient’s informed consent.

WT1 peptide/HLA-A*2402 tetramer assay

WT1-specific CTLs in peripheral blood were evaluated based on HLA tetramers (Medical & Biological Laboratories Co., Ltd) before and after the course of DC vaccination. Outcomes were regarded as positive when CD3-positive, CD8-positive, and WT1/HLA-A24 tetramer-positive cell populations were discovered with the cultured cells. HIVenv/HLA-A24 tetramer-positive cells were utilized as the negative controls.

WT1-specific interferon-γ enzyme-linked immunospot assay

The IFN-γ ELISPOT assay was conducted as detailed previously. PBMCs were established as specifically sensitized when spots suggesting IFN-γ release in reaction to the WT1 peptide were twice that of the reaction to HIVenv peptide-pulsed stimulator cells in the ELISPOT assay.

Surface marker analysis

PBMCs were incubated with fluorescent-conjugated monoclonal antibodies for 40 min at 4 °C in the dark. After surface staining, cells were washed and fixed with stabilizing fixative (BD Biosciences) and determined with the fluorescent-activated cell sorting Calibur and CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

Data are shown as mean values ± SD. Statistical significance was evaluated with GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.), using a Student’s t test or one- and two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s and Bonferroni’s post-hoc tests, as indicated. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1, and specifics of the immunological results for every one of the patients following vaccinations are shown in Table 2. We noted no Grade 3 or greater National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria toxicities linked to DC vaccination. Every one of the 10 enrolled patients had a local inflammatory reaction with mild erythema at the vaccination injection site within several days. There were four patients who experienced postvaccination fever, and this continued for a few hours following the initial DC vaccination. Fatigue was observed in two patients.

Table 1.

Summary of patient characteristics and clinical outcomes of DC-based immunotherapy

| Patient no. | Age (years) sex | Dx | Clinical stage | Previous therapy | Clinical response after first course | Clinical response after final session | Immunological responses (IR) | Overall survival (mos) | Survival status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tx (no. of cycles) | Additional Tx | KPS score (%) | RECIST | Clinical effect | RECIST | Clinical effect | |||||||

| 1 | 56, F | Breast | III | CTX (20) | – | 70 | SD | Yes | SD PR PD | Yes | + | 15.3 | Deceased |

| 2 | 45, F | Breast | IV | CTX (17) | – | 50 | SD | Yes | SD | Yes | − | > 23.2 | Alive |

| 3 | 37, F | Breast | IV | CTX(10), HTX(2) | – | 60 | SD | Yes | PR | Yes | + | > 22.6 | Alive |

| 4 | 57, F | Breast | III | CTX (19) | – | 70 | SD | Yes | SD | Yes | − | > 17.2 | Alive |

| 5 | 50, F | Ovarian | IV | CTX (16) | Ovariectomy between second and third vaccination | 70 | SD | Yes | PD | No | − | 13.1 | Deceased |

| 6 | 39, F | Ovarian | III | CTX (12) | – | 80 | PD | No | PD | No | − | 9.3 | Deceased |

| 7 | 59, F | Ovarian | IV | CTX (10) | – | 50 | SD | Yes | SD | Yes | + | > 20.1 | Alive |

| 8 | 42, M | Gastric | IV | CTX (13) | – | 70 | SD | Yes | PD | Yes | + | 16.7 | Deceased |

| 9 | 67, M | Gastric | III | CTX (12) | – | 70 | PD | No | PD | No | − | 12.3 | Deceased |

| 10 | 56, F | Gastric | IV | CTX (16) | – | 60 | PD | No | PD | No | − | 11.6 | Deceased |

Dx diagnosis, Tx treatment, CTX chemotherapy treatment, HTX Hormones treatment, KPS Karnofsky Performance Status, – no further treatment

Table 2.

Immunological monitoring data in patients who received WT1-pulsed DC vaccination

| Patient no. | WT1 tetramer, % | ELISpot assay (spots/1 × 105 PBMCs) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-therapy | Post-therapy | Pre-therapy | Post-therapy | |

| 1 | 0.17 | 1.21 | 17 | 113 |

| 2 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 98 | 61 |

| 3 | 0.68 | 5.67 | 6 | 390 |

| 4 | 0.78 | 1.03 | 23 | 211 |

| 5 | 0.56 | 3.31 | 46 | 256 |

| 6 | 0.29 | 11.01 | 9 | 13 |

| 7 | 0.22 | 16.72 | 4 | 506 |

| 8 | 0.30 | 19.81 | 12 | 106 |

| 9 | 0.57 | 1.21 | 121 | 136 |

| 10 | 0.37 | 1.56 | 106 | 70 |

ELISpot enzyme-linked immunospot, PBMCs peripheral blood mononuclear cells

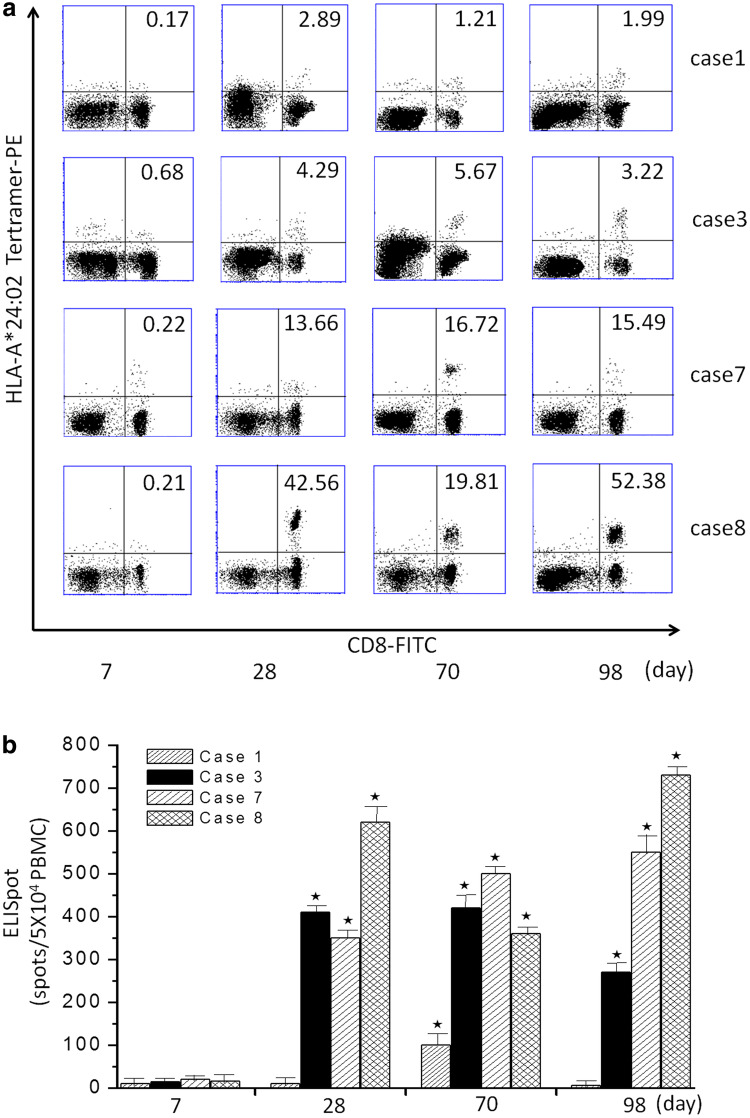

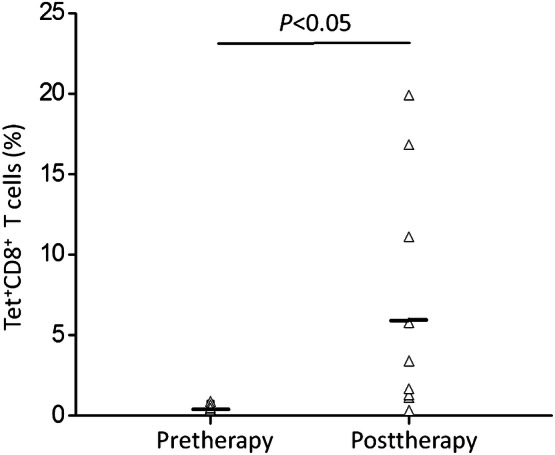

Immunological responses

WT1-pulsed DC vaccination therapy was assessed with a HLA/WT1-tetramer and cytoplasmic IFN-γ assays with PBMCs. Levels of tetramer-positive WT1-specific CTLs were significantly raised following DC vaccination (P < 0.05; Fig. 1). An ELISPOT assay showed that WT1-specific CTL responses were enhanced in eight patients (Table 2). Immunological responses data appear in Table 2. There were four patients (cases 1, 3, 7, and 8) who had stronger reactions to HLA-tetramer and IFN-γ ELISPOT assays following DC vaccination (P < 0.05; Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Frequency of WT1-specific CTLs before and after DC vaccination in the tetramer assay. The black horizontal bar shows the median. Differences between values before and after WT1 vaccination were statistically significant (P < 0.05)

Fig. 2.

WT1-specific CTLs induced by DC vaccination. a Upper panel, WT1-peptide/HLA-A*2402 tetramer assays. Percentages represent the frequency of tetramer+CD8+ T cells. Cases 1, 3, 7, and 8 show a significant increase in the frequency of tetramer+CD8+ T cells after DC vaccination compared to pre-therapy (*P < 0.05). b Lower panel, IFN-γ-producing clones in ELISPOT assays with WT1 peptide. Cases 1, 3, 7, and 8 show a significant increase in the response in the ELISPOT after DC vaccination compared to pre-therapy values (*P < 0.05)

Clinical outcomes

Data for each treatment group appear in Table 1. At the conclusion of the initial DC vaccination, seven patients had stable disease and three patients had PD. Every individual with stable disease was treated with WT1-pulsed DC vaccination. For three of the seven patients with stable disease, their Karnofsky Performance Scale scores improved from 50 to 60% (patients 2 and 7) and from 60 to 70% (patient 3). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scans revealed a regression of metastatic tumors for patient 3 (Fig. 3a), and patient 7 had tumor shrinkage (Fig. 3b) following DC vaccination. A partial response was observed throughout ongoing vaccination following the initial session. The maximum follow-up was 26 months following the initial DC vaccination; at that time, six patients had died.

Fig. 3.

Tumor regression occurred in patient 3 a with metastatic breast cancer and in patient 7 b with ovarian cancer during the course of DC vaccination. (Left) Before and (right) after DC vaccination, respectively. Arrows indicate the presumed location of the tumor

To determine the factors that were predictive of immune reactions to DC vaccination, we examined immune cell subsets in pretreated peripheral blood, utilizing cytometry-based comprehensive leukocyte immunophenotyping. Figure 4 shows that immunological responses were significantly correlated with fewer myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) (CD14−CD11b+CD33+) (P = 0.045), and there were no differences in the percentages of Treg (CD25+Foxp3+CD4+) cells (P = 0.295), the total CD14+CD11b+ (P = 0.11), and CD14+CD11b− cells (P = 0.36) between immunological response-positive and immunological response-negative patients. Thus, DC vaccination may be effective for patients with fewer MDSCs and fewer Tregs prior to treatment. In contrast, there was no difference in total lymphocytes observed in the 10 evaluable patients.

Fig. 4.

Pretreatment total lymphocyte numbers and the frequency of various circulating lymphocyte phenotypes in the peripheral blood of all patients. The immunological responses were significantly correlated with fewer myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). MDSCs were identified as CD14−CD11b+CD33+. IR, immunological responses

Discussion

Over the last decade, DCs have emerged as key players in the initiation of anti-tumor immunity [36, 37]. Induction of potent tumor-specific cytotoxic CD8 + T-cell responses after peptide-based vaccination is the foundation of immune-based therapies for cancer patients [38, 39]. Here, we provide evidence that vaccination with WT1 peptide-pulsed DCs can be used for patients with breast, ovarian, and gastric cancers, and the DCs induce immunological response directed toward less immunogenic tumors. Patients were eligible if the disease was resistant to conventional chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or hormonal therapy (breast cancer). Patients declining such treatments but requesting DC vaccine therapy were also eligible. Clinical responses observed in this phase I/II clinical study were satisfactory. Partial response was reached in two of the ten patients throughout ongoing vaccination following the initial session. Stable disease was achieved following the first course in seven of the patients who were given DC vaccinations. Two of the patients had positive clinical and radiological reactions based on RECIST throughout the clinical course. Noted toxicities were all Grade 1 or 2 based on the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria. Further, no autoimmune reactivity was noted in the patients who received WT1-pulsed DC vaccinations. Therefore, vaccination therapy utilizing DCs pulsed with WT1-derived peptides is well tolerated, safe, and practical for the treatment of solid tumors.

Efficacious anti-tumor immunity in humans has been associated with the presence of CD8+ T-cell uptake of tumor neoantigens, a class of MHC-I-bound peptides that is highly immunogenic and not present in normal tissues. Since tumor neoantigens are unique to patients, identification of tumor-specific shared targets across a range of cancers is needed. At the National Cancer Institute, WT1 was reported to be a promising target due to its abundance and broad expression in many cancer types as well as its limited expression in normal organs [2].

Clinical studies of cancer immunotherapies targeting WT1 in leukemia and solid tumors indicate that WT1-specific CTL reactions can be stimulated, and clinical reactions have been assessed in several patients. The data reveal that WT1-specific CTLs attack WT1-expressing tumor cells and transformed stem cells, but they do not destroy healthy cells [40]. Induction and activation of WT1-specific CTLs are attained via cross priming mediated by DCs, which subsequently prompts peptides to be presented to HLA class-I (HLA-I) molecules (cross-presentation) [41, 42]. HLA-A*24:02-restricted altered WT1 peptides could improve cancer immunity [43–45]. Here, we report that the antigen-specific response in four patients was elicited by WT1-pulsed DC immunizations. Then, HLA-tetramer and cytoplasmic IFN-γ assays were used to evaluate the data, and the patients tested positive in both assays. In addition, immunological reactions corresponded with several MDSCs in pretreated peripheral blood.

In the tumor microenvironment, there are many immunosuppressive cells, including CD25+Foxp3+CD4+ Tregs [46] and MDSCs [46]. Further, MDSC-repressed anti-tumor immunity is linked to poor outcomes in cancer patients [47–49]. Thus, limited MDSCs and fewer CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs prior to treatment could be useful markers for DC vaccination efficacy in cancer patients. Therefore, the evaluation of reactions to DC vaccinations could be predicted from immunological variables that correspond with the induction of immune reactions and anti-tumor impact. However, standardization of DC vaccine-manufacturing technology and investigation of the quality and immunological efficacy are needed for DC-based vaccination therapy to be used routinely.

In summary, DCs pulsed with WT1 peptide antigens could be helpful for certain patients; however, the efficacy and safety of DC vaccinations need to be assessed in bigger populations and in prospectively designed studies. This evaluation may lay a foundation for future studies that examine treatment of other tumors expressing WT1 peptides.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- CTLs

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes

- DC

Dendritic cell

- ELISPOT

Enzyme-linked immuno spot

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HLA

Human leukocyte antigen

- IFN

Interferon

- KPS

Karnofsky Performance Status

- MDSCs

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- PBMCs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- RECIST

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- TAA

Tumor-associated antigens

- Treg

Regulatory cells

- WT1

Wilms tumor protein 1

Author contributions

WZ, XL and PC designed and coordinated the project. CP, MX, XL, YW and XW performed the clinical and laboratory experiments. All authors take responsibility for the accuracy of the final revision of the text. LY and JL took the lead in writing the paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81770468), Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (7162030) and the Beijing Science and Technology Plan special issue (Z14010101101).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This trial was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Cancer Center/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, and was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trials Registry (ChiCTR-IPR-15005923).

Informed consent

Written informed consent was acquired from each patient in the study.

Footnotes

Wen Zhang, Xu Lu and Peilin Cui have contributed equally to this study.

Contributor Information

Jingwei Liu, Phone: 0086-10-80498890, Email: ljwgirl361@163.com.

Lin Yang, Phone: 0086-10-87788519, Email: 403182179@qq.com.

References

- 1.Couzin-Frankel J. Breakthrough of the year 2013. Cancer Immunother Sci. 2013;342:1432–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.342.6165.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheever MA, Allison JP, Ferris AS, Finn OJ, Hastings BM, Hecht TT, Mellman I, Prindiville SA, Viner JL, Weiner LM, Matrisian LM. The prioritization of cancer antigens: a national cancer institute pilot project for the acceleration of translational research. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5323–5337. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oji Y, Suzuki T, Nakano Y, Maruno M, Nakatsuka S, Jomgeow T, Abeno S, Tatsumi N, Yokota A, Aoyagi S, Nakazawa T, Ito K, Kanato K, Shirakata T, Nishida S, Hosen N, Kawakami M, Tsuboi A, Oka Y, Aozasa K, Yoshimine T, Sugiyama H. Overexpression of the Wilms’ tumor gene WT1 in primary astrocytic tumors. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:822–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb02188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keilholz U, Letsch A, Busse A, Asemissen AM, Bauer S, Blau IW, Hofmann WK, Uharek L, Thiel E, Scheibenbogen C. A clinical and immunologic phase 2 trial of Wilms tumor gene product 1 (WT1) peptide vaccination in patients with AML and MDS. Blood. 2009;113:6541–6548. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-202598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsuboi A, Oka Y, Kyo T, Katayama Y, Elisseeva OA, Kawakami M, Nishida S, Morimoto S, Murao A, Nakajima H, Hosen N, Oji Y, Sugiyama H. Long-term WT1 peptide vaccination for patients with acute myeloid leukemia with minimal residual disease. Leukemia. 2012;26:1410–1413. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oka Y, Tsuboi A, Taguchi T, Osaki T, Kyo T, Nakajima H, Elisseeva OA, Oji Y, Kawakami M, Ikegame K, Hosen N, Yoshihara S, Wu F, Fujiki F, Murakami M, Masuda T, Nishida S, Shirakata T, Nakatsuka S, Sasaki A, Udaka K, Dohy H, Aozasa K, Noguchi S, Kawase I, Sugiyama H. Induction of WT1 (Wilms’ tumor gene)-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes by WT1 peptide vaccine and the resultant cancer regression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13885–13890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405884101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapuis AG, Ragnarsson GB, Nguyen HN, Chaney CN, Pufnock JS, Schmitt TM, Duerkopp N, Roberts IM, Pogosov GL, Ho WY, Ochsenreither S, Wolfl M, Bar M, Radich JP, Yee C, Greenberg PD. Transferred WT1-reactive CD8 + T cells can mediate antileukemic activity and persist in post-transplant patients. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:127–174. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dao T, Pankov D, Scott A, Korontsvit T, Zakhaleva V, Xu Y, Xiang J, Yan S, de Morais Guerreiro MD, Veomett N, Dubrovsky L, Curcio M, Doubrovina E, Ponomarev V, Liu C, O’Reilly RJ, Scheinberg DA. Therapeutic bispecific T-cell engager antibody targeting the intracellular oncoprotein WT1. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:1079–1086. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caldon CE, Lee CS, Sutherland RL, Musgrove EA. Wilms’ tumor protein 1: an early target of progestin regulation in T-47D breast cancer cells that modulates proliferation and differentiation. Oncogene. 2008;27:126–138. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qi XW, Zhang F, Yang XH, Fan LJ, Zhang Y, Liang Y, Ren L, Zhong L, Chen QQ, Zhang KY, Zang WD, Wang LS, Zhang Y, Jiang J. High Wilms’ tumor 1 mRNA expression correlates with basal-like and ERBB2 molecular subtypes and poor prognosis of breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:1231–1236. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han SH, Joo M, Kim H, Chang S. Mesothelin expression in gastric adenocarcinoma and its relation to clinical outcomes. J Pathol Transl Med. 2017;51:122–128. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2016.11.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Z, Yamanouchi K, Ohtao T, Matsumura S, Seino M, Shridhar V, Takahashi T, Takahashi K, Kurachi H. High levels of Wilms’ tumor 1 (WT1) expression were associated with aggressive clinical features in ovarian cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:2331–2340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qi XW, Zhang F, Wu H, Liu JL, Zong BG, Xu C, Jiang J. Wilms’ tumor 1 (WT1) expression and prognosis in solid cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8924. doi: 10.1038/srep08924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noone AM, Howlader N, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds) (2018) SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2015, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2015/, based on November 2017 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2018

- 15.Miyatake T, Ueda Y, Morimoto A, Enomoto T, Nishida S, Shirakata T, Oka Y, Tsuboi A, Oji Y, Hosen N, Nakatsuka S, Morita S, Sakamoto J, Sugiyama H, Kimura T. WT1 peptide immunotherapy for gynecologic malignancies resistant to conventional therapies: a phase II trial. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139:457–463. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1348-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohno S, Okuyama R, Aruga A, Sugiyama H, Yamamoto M. Phase I trial of Wilms’ Tumor 1 (WT1) peptide vaccine with GM-CSF or CpG in patients with solid malignancy. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:2263–2269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takahashi H, Okamoto M, Shimodaira S, Tsujitani S, Nagaya M, Ishidao T, Kishimoto J, Yonemitsu Y, Therapy DC-vsgatJSoIC. Impact of dendritic cell vaccines pulsed with Wilms’ tumour-1 peptide antigen on the survival of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancers. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:852–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakai K, Shimodaira S, Maejima S, Udagawa N, Sano K, Higuchi Y, Koya T, Ochiai T, Koide M, Uehara S, Nakamura M, Sugiyama H, Yonemitsu Y, Okamoto M, Hongo K. Dendritic cell-based immunotherapy targeting Wilms’ tumor 1 in patients with recurrent malignant glioma. J Neurosurg. 2015;123:989–997. doi: 10.3171/2015.1.JNS141554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palucka K, Banchereau J. Cancer immunotherapy via dendritic cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:265–277. doi: 10.1038/nrc3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujiki F, Oka Y, Tsuboi A, Kawakami M, Kawakatsu M, Nakajima H, Elisseeva OA, Harada Y, Ito K, Li Z, Tatsumi N, Sakaguchi N, Fujioka T, Masuda T, Yasukawa M, Udaka K, Kawase I, Oji Y, Sugiyama H. Identification and characterization of a WT1 (Wilms Tumor Gene) protein-derived HLA-DRB1*0405-restricted 16-mer helper peptide that promotes the induction and activation of WT1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Immunother. 2007;30:282–293. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000211337.91513.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.May RJ, Dao T, Pinilla-Ibarz J, Korontsvit T, Zakhaleva V, Zhang RH, Maslak P, Scheinberg DA. Peptide epitopes from the Wilms’ tumor 1 oncoprotein stimulate CD4 + and CD8 + T cells that recognize and kill human malignant mesothelioma tumor cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4547–4555. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oka Y, Tsuboi A, Elisseeva OA, Nakajima H, Fujiki F, Kawakami M, Shirakata T, Nishida S, Hosen N, Oji Y, Kawase I, Sugiyama H. WT1 peptide cancer vaccine for patients with hematopoietic malignancies and solid cancers. ScientificWorldJournal. 2007;7:649–665. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oka Y, Tsuboi A, Murakami M, Hirai M, Tominaga N, Nakajima H, Elisseeva OA, Masuda T, Nakano A, Kawakami M, Oji Y, Ikegame K, Hosen N, Udaka K, Yasukawa M, Ogawa H, Kawase I, Sugiyama H. Wilms tumor gene peptide-based immunotherapy for patients with overt leukemia from myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or MDS with myelofibrosis. Int J Hematol. 2003;78:56–61. doi: 10.1007/BF02983241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uttenthal B, Martinez-Davila I, Ivey A, Craddock C, Chen F, Virchis A, Kottaridis P, Grimwade D, Khwaja A, Stauss H, Morris EC. Wilms’ Tumour 1 (WT1) peptide vaccination in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia induces short-lived WT1-specific immune responses. Br J Haematol. 2014;164:366–375. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anguille S, Van de Velde AL, Smits EL, Van Tendeloo VF, Juliusson G, Cools N, Nijs G, Stein B, Lion E, Van Driessche A, Vandenbosch I, Verlinden A, Gadisseur AP, Schroyens WA, Muylle L, Vermeulen K, Maes MB, Deiteren K, Malfait R, Gostick E, Lammens M, Couttenye MM, Jorens P, Goossens H, Price DA, Ladell K, Oka Y, Fujiki F, Oji Y, Sugiyama H, Berneman ZN. Dendritic cell vaccination as postremission treatment to prevent or delay relapse in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2017;130:1713–1721. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-04-780155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukuda K, Funakoshi T, Sakurai T, Nakamura Y, Mori M, Tanese K, Tanikawa A, Taguchi J, Fujita T, Okamoto M, Amagai M, Kawakami Y. Peptide-pulsed dendritic cell vaccine in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy for stage IV melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2017;27:326–334. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitawaki T, Kadowaki N, Kondo T, Ishikawa T, Ichinohe T, Teramukai S, Fukushima M, Kasai Y, Maekawa T, Uchiyama T. Potential of dendritic-cell immunotherapy for relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, shown by WT1 peptide- and keyhole-limpet-hemocyanin-pulsed, donor-derived dendritic-cell vaccine for acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:315–317. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kobayashi M, Sakabe T, Abe H, Tanii M, Takahashi H, Chiba A, Yanagida E, Shibamoto Y, Ogasawara M, Tsujitani S, Koido S, Nagai K, Shimodaira S, Okamoto M, Yonemitsu Y, Suzuki N, Nagaya M, Therapy DC-vsgatJSoIC. Dendritic cell-based immunotherapy targeting synthesized peptides for advanced biliary tract cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1609–1617. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2286-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koido S, Kan S, Yoshida K, Yoshizaki S, Takakura K, Namiki Y, Tsukinaga S, Odahara S, Kajihara M, Okamoto M, Ito M, Yusa S, Gong J, Sugiyama H, Ohkusa T, Homma S, Tajiri H. Immunogenic modulation of cholangiocarcinoma cells by chemoimmunotherapy. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:6353–6361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayanagi S, Kitago M, Sakurai T, Matsuda T, Fujita T, Higuchi H, Taguchi J, Takeuchi H, Itano O, Aiura K, Hamamoto Y, Takaishi H, Okamoto M, Sunamura M, Kawakami Y, Kitagawa Y. Phase I pilot study of Wilms tumor gene 1 peptide-pulsed dendritic cell vaccination combined with gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci. 2015;106:397–406. doi: 10.1111/cas.12621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saito S, Yanagisawa R, Yoshikawa K, Higuchi Y, Koya T, Yoshizawa K, Tanaka M, Sakashita K, Kobayashi T, Kurata T, Hirabayashi K, Nakazawa Y, Shiohara M, Yonemitsu Y, Okamoto M, Sugiyama H, Koike K, Shimodaira S. Safety and tolerability of allogeneic dendritic cell vaccination with induction of Wilms tumor 1-specific T cells in a pediatric donor and pediatric patient with relapsed leukemia: a case report and review of the literature. Cytotherapy. 2015;17:330–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takakura K, Koido S, Kan S, Yoshida K, Mori M, Hirano Y, Ito Z, Kobayashi H, Takami S, Matsumoto Y, Kajihara M, Misawa T, Okamoto M, Sugiyama H, Homma S, Ohkusa T, Tajiri H. Prognostic markers for patient outcome following vaccination with multiple MHC Class I/II-restricted WT1 peptide-pulsed dendritic cells plus chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:555–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsukinaga S, Kajihara M, Takakura K, Ito Z, Kanai T, Saito K, Takami S, Kobayashi H, Matsumoto Y, Odahara S, Uchiyama K, Arakawa H, Okamoto M, Sugiyama H, Sumiyama K, Ohkusa T, Koido S. Prognostic significance of plasma interleukin-6/-8 in pancreatic cancer patients receiving chemoimmunotherapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11168–11178. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i39.11168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Tendeloo VF, Van deVan Driessche VA, Cools A, Anguille N, Ladell S, Gostick K, Vermeulen E, Pieters K, Nijs K, Stein G, Smits B, Schroyens EL, Gadisseur WA, Vrelust AP, Jorens I, Goossens PG, de Vries H, Price IJ, Oji DA, Oka Y, Sugiyama Y, Berneman H. Induction of complete and molecular remissions in acute myeloid leukemia by Wilms’ tumor 1 antigen-targeted dendritic cell vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:13824–13829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008051107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kimura Y, Tsukada J, Tomoda T, Takahashi H, Imai K, Shimamura K, Sunamura M, Yonemitsu Y, Shimodaira S, Koido S, Homma S, Okamoto M. Clinical and immunologic evaluation of dendritic cell-based immunotherapy in combination with gemcitabine and/or S-1 in patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Pancreas. 2012;41:195–205. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31822398c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dagvadorj N, Deuretzbacher A, Weisenberger D, Baumeister E, Trebing J, Lang I, Kochel C, Kapp M, Kapp K, Beilhack A, Hunig T, Einsele H, Wajant H, Grigoleit GU. Targeting of the WT191-138 fragment to human dendritic cells improves leukemia-specific T-cell responses providing an alternative approach to WT1-based vaccination. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:319–332. doi: 10.1007/s00262-016-1938-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garg AD, Vara Perez M, Schaaf M, Agostinis P, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G, Galluzzi L. Trial watch: dendritic cell-based anticancer immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1328341. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1328341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wei FQ, Sun W, Wong TS, Gao W, Wen YH, Wei JW, Wei Y, Wen WP. Eliciting cytotoxic T lymphocytes against human laryngeal cancer-derived antigens: evaluation of dendritic cells pulsed with a heat-treated tumor lysate and other antigen-loading strategies for dendritic-cell-based vaccination. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35:18. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0295-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ueda N, Zhang R, Tatsumi M, Liu TY, Kitayama S, Yasui Y, Sugai S, Iwama T, Senju S, Okada S, Nakatsura T, Kuzushima K, Kiyoi H, Naoe T, Kaneko S, Uemura Y. BCR-ABL-specific CD4 + T-helper cells promote the priming of antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells via dendritic cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2018;15:15–26. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2016.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao L, Bellantuono I, Elsasser A, Marley SB, Gordon MY, Goldman JM, Stauss HJ. Selective elimination of leukemic CD34(+) progenitor cells by cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for WT1. Blood. 2000;95:2198–2203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishida S, Koido S, Takeda Y, Homma S, Komita H, Takahara A, Morita S, Ito T, Morimoto S, Hara K, Tsuboi A, Oka Y, Yanagisawa S, Toyama Y, Ikegami M, Kitagawa T, Eguchi H, Wada H, Nagano H, Nakata J, Nakae Y, Hosen N, Oji Y, Tanaka T, Kawase I, Kumanogoh A, Sakamoto J, Doki Y, Mori M, Ohkusa T, Tajiri H, Sugiyama H. Wilms tumor gene (WT1) peptide-based cancer vaccine combined with gemcitabine for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Immunother. 2014;37:105–114. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dao T, Korontsvit T, Zakhaleva V, Jarvis C, Mondello P, Oh C, Scheinberg DA. An immunogenic WT1-derived peptide that induces T cell response in the context of HLA-A*02:01 and HLA-A*24:02 molecules. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1252895. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1252895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsuboi A, Oka Y, Udaka K, Murakami M, Masuda T, Nakano A, Nakajima H, Yasukawa M, Hiraki A, Oji Y, Kawakami M, Hosen N, Fujioka T, Wu F, Taniguchi Y, Nishida S, Asada M, Ogawa H, Kawase I, Sugiyama H. Enhanced induction of human WT1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes with a 9-mer WT1 peptide modified at HLA-A*2402-binding residues. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2002;51:614–620. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0328-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koido S, Homma S, Okamoto M, Takakura K, Mori M, Yoshizaki S, Tsukinaga S, Odahara S, Koyama S, Imazu H, Uchiyama K, Kajihara M, Arakawa H, Misawa T, Toyama Y, Yanagisawa S, Ikegami M, Kan S, Hayashi K, Komita H, Kamata Y, Ito M, Ishidao T, Yusa S, Shimodaira S, Gong J, Sugiyama H, Ohkusa T, Tajiri H. Treatment with chemotherapy and dendritic cells pulsed with multiple Wilms’ tumor 1 (WT1)-specific MHC class I/II-restricted epitopes for pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:4228–4239. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimodaira S, Sano K, Hirabayashi K, Koya T, Higuchi Y, Mizuno Y, Yamaoka N, Yuzawa M, Kobayashi T, Ito K, Koizumi T. Dendritic cell-based adjuvant vaccination targeting Wilms’ tumor 1 in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Vaccines (Basel) 2015;3:1004–1018. doi: 10.3390/vaccines3041004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanaka A, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells in cancer immunotherapy. Cell Res. 2017;27:109–118. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodriguez PC, Ernstoff MS, Hernandez C, Atkins M, Zabaleta J, Sierra R, Ochoa AC. Arginase I-producing myeloid-derived suppressor cells in renal cell carcinoma are a subpopulation of activated granulocytes. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1553–1560. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ibanez-Vea M, Zuazo M, Gato M, Arasanz H, Fernandez-Hinojal G, Escors D, Kochan G. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment: current knowledge and future perspectives. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2017 doi: 10.1007/s00005-017-0492-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heine A, Flores C, Gevensleben H, Diehl L, Heikenwalder M, Ringelhan M, Janssen KP, Nitsche U, Garbi N, Brossart P, Knolle PA, Kurts C, Hochst B. Targeting myeloid derived suppressor cells with all-trans retinoic acid is highly time-dependent in therapeutic tumor vaccination. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1338995. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1338995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]