Abstract

Our recent clinical study demonstrated that glypican-3 (GPC3)-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T (CAR-T) cells are a promising treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, the interaction of programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and PD-L1-mediated T-cell inhibition is involved in immune evasion in a wide range of solid tumors, including HCC. To overcome this problem, we introduced a fusion protein composed of a PD-1 extracellular domain and CH3 from IgG4 into GPC3-specific CAR-T cells (GPC3-28Z) to block the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. GPC3-specific CAR-T cells carrying the PD-1–CH3 fusion protein (sPD1) specifically recognized and lysed GPC3-positive HCC cells. The proliferation capacity of GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells after weekly stimulation with target cells was much higher than that of control GPC3-28Z T cells. Additionally, the coexpression of sPD1 could protect CAR-T cells from exhaustion when incubated with target cells, as phosphorylated AKT and Bcl-xL expression levels were higher in GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells than in GPC3-28Z cells. Importantly, in two HCC tumor xenograft models, GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells displayed a significantly higher tumor suppression capacity than GPC3-28Z T cells. In addition, an increased number of CD3+ T cells in the circulation and tumors and increased granzyme B levels and decreased Ki67 expression levels in the tumors were observed in the mice treated with GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells. Together, these data indicated that GPC3-specific CAR-T cells carrying sPD1 show promise as a treatment for patients with HCC.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00262-018-2221-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Chimeric antigen receptor, PD-1/PD-L1, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Glypican-3, sPD1

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-engineered T cells have been demonstrated as a promising strategy for cancer treatment in recent years [1]. In previous studies, we demonstrated the effects of glypican-3 (GPC3)-targeted CAR-T cells against hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in tumor-bearing mice [2]. Recently, the safety and preliminary efficacy of GPC3 CAR-T cells were demonstrated in a phase 1 trial of 13 Chinese patients with GPC3+ HCC in [3]. However, the response rate is far from satisfactory when compared to CD19-targeted CAR-T cells. Similarly, the clinical outcome of most patients with solid tumors treated with CAR-T cells is far from satisfactory [4, 5]. This is partially due to a host of problems encountered in the tumor microenvironment (TME) of solid tumors, including intrinsic inhibitory pathways mediated by upregulated inhibitory receptors reacting with their cognate ligands within the tumor [6].

PD-1 is an inhibitory receptor that is absent in resting T cells, but expressed in exhausted T cells in patients with cancer [7]. PD-L1, which has been identified as a counter-receptor for PD-1 [8], is expressed on the surface of antigen-presenting cells and malignant cells, particularly in response to local inflammatory cytokines, such as type I and II interferons. The engagement of PD-L1 and PD-1 may cause T-cell apoptosis, anergy and exhaustion. Thus, these T cells are functionally impaired, but their biological activity can be partially recovered by blocking PD-1 or PD-L1 [9–11]. The anti-PD-1 mAbs pembrolizumab and nivolumab, which were approved by the FDA in 2014, have achieved modestly satisfactory results in patients with melanoma [12, 13], NSCLC [14], RCC [12], bladder cancer [15], and a growing list of other malignancies. However, most of the patients do not experience a complete response upon anti-PD-1 treatment, and some of them do not respond at all, highlighting the need to better understand the molecular and cellular effects of blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and the mechanism underlying those effects. Studies in animal models and clinical trials have indicated that blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway may influence tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and other immune cells in the tumor microenvironment [16]. Interference with the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway may cause T cells to remain in a dysfunctional state during cancer [17]. Given the inhibitory effects of PD-1/PD-L1 engagement in T cells, we speculate that CAR-T cells carrying PD-1 blockade agents may be spared from exhaustion, which could enhance antitumor effects in solid tumors.

In this study, we engineered T cells with a CAR targeting GPC3, which is highly expressed in HCC, but is limited in normal tissues and has been proven to be an ideal tumor antigen in our previous studies [2]. GPC3-28Z-sPD1 CAR-T cells were constructed to secrete sPD1 to block the PD-1/PD-L1 signaling pathway. We aimed to explore whether blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway would enhance the antitumor effect of CAR-T cells and prolong cell persistence in HCC.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture

Human HCC cell lines (SK-HEP-1, PLC/PRF/5, HepG2 and Hep3B) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA). The Huh7 cell line was obtained from the RIKEN Cell Bank. The human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293T cell line was purchased from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). SK-HEP-1-GPC3 cells were established by transduction with a lentivirus expressing the GPC3 gene (constructed by our laboratory) into SK-HEP-1 cells. All of the cells mentioned above were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The medium was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 µg/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin.

Vector construction and lentivirus production

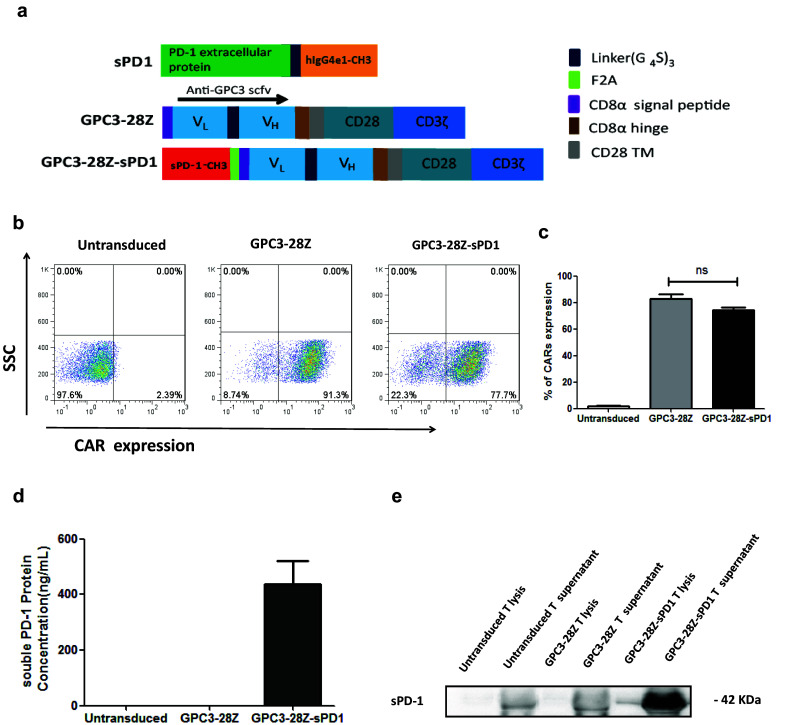

The sequence encoding the anti-GPC3 scFv antibody, developed by our laboratory, recognizes the C-terminal region of GPC3, which was obtained by PCR splicing and the overlap extension technique. As shown in Fig. 1a, GPC3-28Z CAR (second-generation) contained anti-GPC3 scFv linked in-frame to the hinge domain of CD8α (GenBank NM 001768.6) and fused to the transmembrane region of human CD28 (GenBank NM_006139.3) and the intracellular signaling domain (GenBank NM_006139.3) of CD3ζ (GenBank NM_198253.2) in tandem. GPC3-28Z-sPD1 CAR was constructed by linking the PD-1 extracellular domain (GenBank NM_005018.2) and the human IgG4e1 CH3 domain to GPC3-28Z with a foot-and-mouth disease virus 2A oligopeptide [18]. Finally, all the products contained a Mlu I site at the 5′ end and a Sal I site at the 3′ end and were ligated to the third-generation self-inactivating EF-1a promoter-based lentiviral expression vector pRRLSIN-cPPT.EF1α (purchased from Addgene). The primers are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Fig. 1.

GPC3-28Z and GPC3-28Z-sPD1 CAR constructs and T-cell transfection. a Schematic representation of soluble PD-1–CH3 fusion protein (sPD1) and GPC3-28Z CAR; GPC3-28Z was fused with sPD1 using the ‘self-cleaving’ F2A peptide; b Expression of GPC3-28Z and GPC3-28Z-sPD1 on T-cell surface were detected with the indicated antibodies; c CAR expression data pooled from three independent experiments with individual donors (n = 3, mean ± SEM; not significant, P > 0.05); d Concentration of sPD1 in the medium of transduced T cells was measured by Human PD/CD1 ELISA Quantitation Set (Sino Biological); data are pooled from three independent experiments with individual donors (n = 12, mean ± SEM); e sPD1 in the cell lysate and supernatant was determined by Western blot

High-titer lentivirus stocks were produced by the transient transfection of transfer and packaging vectors into 293T cells using polyethyleneimine (PEI) [19]. Briefly, 80% confluent 293T cells in 15-cm plates were transfected with 20.2 µg of the following four plasmids: 6.2 µg each of pMDLg-pRRE and pRSV-Rev, 2.4 µg of pCMV-VSV-G, and 5.4 µg of the CAR-encoding plasmid GPC3-28Z or GPC3-28Z-sPD1. Lentiviral particles were concentrated 30-fold by ultracentrifugation (Beckman Optima XL-100 K, Beckman) for 2 h at 28,000 rpm, aliquoted and frozen at − 80 °C.

Isolation, culture and transduction of primary T cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors were obtained from the Shanghai Blood Center. These cells were stimulated for 48 h with Dynabeads® ClinExVivo™ CD3/CD28 (ThermoFisher Scientific). Activated T cells were transduced with lentivirus in 24-well plates precoated with retronectin (5 µg/ml) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. The transduced T cells were cultured at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/ml in AIM-V® Medium CTS™ (GIBCO) supplemented with 2% human AB serum (Gemini) in the presence of rhIL-2 (500 U/ml; Shanghai Huaxin High Biotech).

T-cell proliferation assay

SK-HEP-1-GPC3 and Huh7 cells were exposed to a 50 Gy X-ray dose. Then, the tumor cells were cocultured with an equal number of CAR-transduced T cells. A total of 1 × 106 T cells were cocultured with the same number of irradiated tumor cells in a 12-well plate at the start of the experiment. T-cell density was maintained at 5 × 105/ml. Viable T cells were counted using a hemocytometer and the trypan blue exclusion method every other day. The cells in all groups were stimulated weekly with the irradiated tumor cells. The cells were observed for no less than 3 weeks. No exogenous cytokines were added during the proliferation assays.

Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-based proliferation assays were used during the repetitive antigen-specific stimulation; before the third stimulation, CAR-T cells were labeled. The stained T cells were cocultured with SK-HEP-1-GPC3 for 96 h before flow cytometric analyses.

Flow cytometry

GPC3 expression on the surface of the HCC cell lines was detected using a humanized anti-GPC3 Ab (developed by our laboratory), followed by a goat-anti-human IgG-FITC secondary antibody. PD-L1 mAb (eBioscience, clone: MIH1) was used to detect PD-L1 expression on the tumor cells. CAR expression on CD3+ T cells was detected by a goat-anti-human IgG F(ab′)2 antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and phycoerythrin (PE)-streptavidin (BD Pharmingen). A panel of antibodies, including anti-CD4+ (BD, FITC-conjugated, clone: RPA-T4), anti-CD8+ (BD, PE-conjugated, clone: RPA-T8), anti-CD45RA (BD, PerCp-Cy5.5-conjugated, clone: H100) and anti-CD197 (BD, APC-R700-conjugated, clone: 3D12), were used to examine the phenotype of the expanded T cells. After three rounds of antigen-specific stimulation, PD-1, TIM-3 and LAG-3 expression on the CAR-T cells was detected by anti-human CD279 (BD, BV421-conjugated, clone: MIH4), anti-human CD366 (eBioscience, APC-conjugated, clone: F38-2E2) and anti-human CD223 (eBioscience, eFluor 450-conjugated, clone: 3DS223H) antibodies, respectively. Additionally, a CD3-PerCP/CD4-FITC/CD8-PE TruCOUNT kit (BD Bioscience) was used to detect the number of circulating human T cells from xenograft-bearing mice treated with CAR-T cells. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were quantified according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blot analysis

To confirm the expression of GPC3 and PD-L1 in various HCC cell lines, cell lysates were denatured and separated by SDS-PAGE. The samples were then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and immunoblotted with an anti-GPC3 antibody (developed by our lab, clone: 9F2) and an anti-PD-L1 antibody (Abcam, clone: 28-8).

To determine the secretion of sPD1 by GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells, the xMag™ protein A/G (GE) was used to enrich sPD1 from the cultural supernatant by attachment to the CH3 subunit. Untransduced T and GPC3-28Z CAR-T cell culture supernatants were used as controls. sPD1 in the supernatant of the cell lysates was assessed with an anti-PD-1 antibody (Abcam, clone: NAT105).

Similarly, to determine the phosphorylation levels of AKT and Bcl-xL in cellular lysates, T cells were cocultured with Huh7 or SK-HEP-1-GPC3 cells at a 1:1 target-to-effector ratio for 48 h. Next, the contents of all culture wells were washed twice with PBS and subjected to low-speed centrifugation to remove the debris. The extracted proteins were used for Western blot analysis. The primary antibodies used were an anti-AKT rabbit mAb (Cell Signaling Technology, clone: 40D4), an anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473) rabbit mAb (Cell Signaling Technology, clone: D9E), and an anti-Bcl-xL rabbit mAb (Cell Signaling Technology, clone: 54H6). Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ 1.45 software.

sPD1 and cytokine release measurement

A total of 1 × 106 GPC3-28Z-sPD1-transduced T cells were maintained with/without antigen-specific stimulation in a 12-well plate containing 1.5 ml of culture medium per well. After 24 h, 100 µl of supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plate precoated with a PD1/PDCD1/CD279 antibody (Sino Biological, clone: H08H). The level of sPD1 secreted into the culture medium of the transduced T cells was detected using human PD1/PDCD1/CD279 ELISA kits (Sino Biological) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cytokines, including IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, that were secreted by CAR-T cells cocultured with different tumor cells at the effector/target ratio of 1:1 for 24 h were measured with ELISA kits (MultiSciences Biotechnology, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Mouse blood was collected and clotted at 4 °C, and the serum was used for IFN-γ detection.

In vitro cytotoxicity

An impedance-based tumor cell killing assay (xCELLigence) was used to determine the specific cytotoxicity of CAR-T cells toward various HCC cells at an effector/target ratio of 2:1. Tumor cells were added to a resistor-bottomed plate at 5000 cells per well. After 24 h, 2500 effector T cells were added; at this point, the cell index values were correlated with target tumor cell adherence and normalized. Impedance-based measurements of the normalized cell index were collected every 15 min, and tumor cell killing was evaluated for 72 h.

Xenograft models of human hepatocellular carcinoma and CAR-T therapy

NOD/SCID mice (6–8-weeks-old) were housed and treated under specific pathogen-free conditions. For the establishment of the Huh7 and SK-HEP-1-GPC3 models, mice were inoculated subcutaneously (s.c.) on their right flank with 2 × 106 tumor cells. When the tumor burden was approximately 150–200 mm3, the mice were allocated into three groups and injected intravenously (i.v.) with the corresponding CAR-T cells (8 × 106 CAR-T cells/mouse for SK-HEP-1-GPC3 models and 7 × 106 CAR-T cells/mouse for Huh7 models) after lymphocyte depletion with cyclophosphamide (200 mg/kg). The tumor dimensions were measured with calipers, and the tumor volumes were calculated using the formula V = (length × width2)/2, where the length was the greatest longitudinal diameter and the width was the greatest transverse diameter.

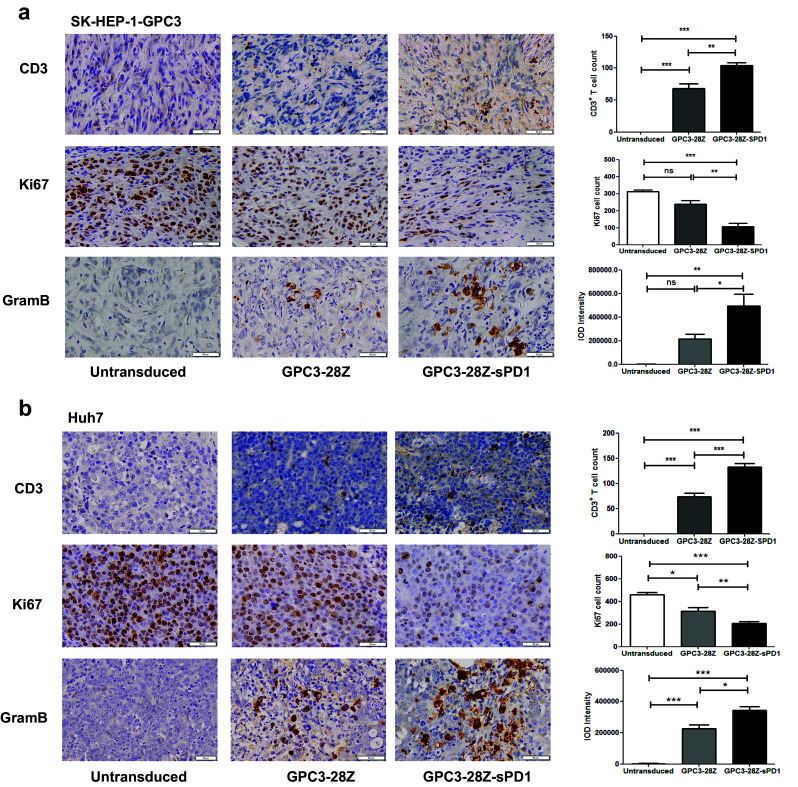

Immunohistochemistry assay

To assess the persistence of administered human T cells and Ki67 expression in the xenografts after treatment, sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissues were immunostained using a mouse monoclonal anti-CD3 antibody (1:150, Thermo Scientific, clone: SP7) and a rabbit polyclonal anti-Ki67 antibody (1:100, Invitrogen). All of the antibodies were incubated overnight. The samples were stained with a rabbit anti-human granzyme B polyclonal Ab (1:100, Abcam) for 45 min. The slides were stained with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) and counterstained with hematoxylin. Photographs of three representative fields were captured. CD3-positive and Ki67-positive cells were counted, and granzyme B staining was analyzed by integrated optical density (IDO) measurement using Image-Pro PLUS v6.0 software.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison was performed to assess the differences in tumor burden (tumor volume, tumor weight, and photon counts). Differences in the absolute number of various transferred T cells were evaluated by Student’s t test, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Generation of GPC3-28Z and GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells

To treat tumors, we developed a new type of CAR to prevent T-cell exhaustion by blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway; we engineered a bicistronic lentiviral vector to express anti-GPC3 scFv linked to CD28 and CD3-ζ signaling domains in the first cassette and coexpressed with sPD1 in the second expression cassette using a “self-cleaving” F2A peptide [20], namely, GPC3-28Z-sPD1 (Fig. 1a). The extracellular domain of PD-1 was fused to the IgG4-CH3 domain, as it plays a critical role in stabilizing soluble proteins [21]. As a control, the second-generation parent CAR, GPC3-28Z, was also prepared. Both CARs showed high transduction efficiency, as shown in Fig. 1b, c. The level of sPD1 secreted by GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells with/without antigen-specific stimulation was determined by ELISA and ranged from 400 to 500 ng/µl (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 3), while no sPD1 secretion could be detected from untransduced T and GPC3-28Z T cells. sPD1 secreted into the culture supernatant was further confirmed by Western blotting, as shown in Fig. 1e. The sPD-1–CH3 fusion protein band was predicted to be 31 kDa according to Vector NTI; because the sPD-1–CH3 fusion protein likely undergoes extensive posttranslational processing when secreted into the supernatant, the final band size was determined to be 42 kDa [22, 23]. Additionally, there appear to be nonspecific bands in the supernatants of both untransduced and GPC3-28Z T cells.

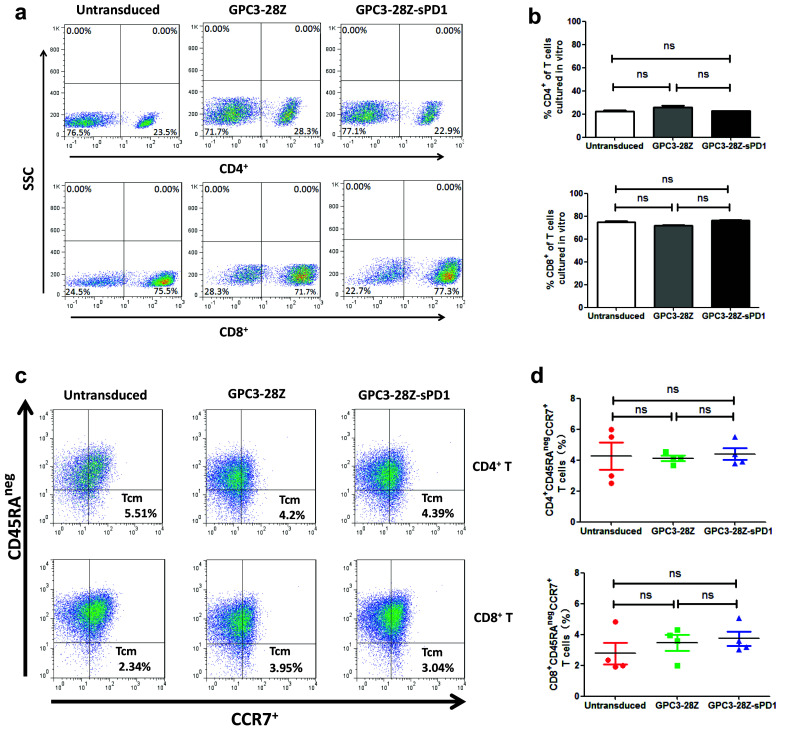

Phenotype of CAR-T cells

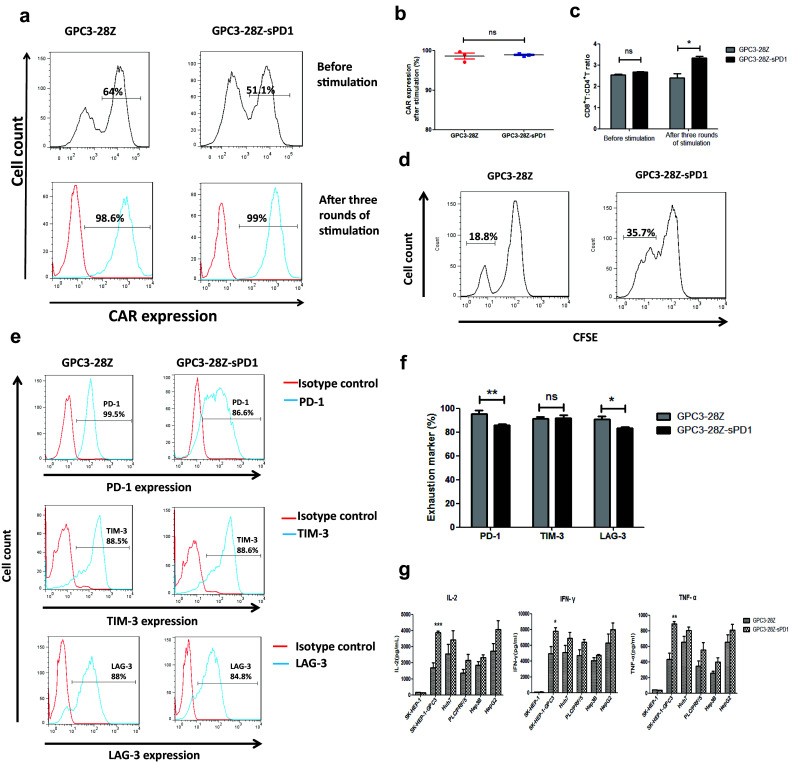

After expansion in vitro for 14 days, more than 70% of the T cells became CD8-positive, which occurred independently of the gene transduction (Fig. 2a, b). According to previous studies, a high CD8/CD4 ratio is an effective indicator of a better outcome of adoptive T-cell immunotherapy against cancer [24]. After repetitive antigen-specific stimulation, the CD8/CD4 ratio of GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells was much higher than that of GPC3-28Z T cells (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 2.

Phenotypes of CAR-T cells. a CD4+ and CD8+ phenotypes assay of expanded CAR-T cells by flow cytometry; b Data are pooled from three independent experiments with individual donors (n = 3, mean ± SEM; not significant, P > 0.05); c Expression levels of CD45RAneg and CCR7 were detected using flow cytometry with the indicated antibodies; d Data are pooled from four independent experiments with individual donors (n = 4, mean ± SEM; not significant, P > 0.05);

Fig. 4.

In vitro behavior of CAR-T cells after repetitive stimulation with SK-HEP-1-GPC3 cells. a CAR expression on the T-cell surface after three rounds of antigen-specific stimulation with SK-HEP-1-GPC3 cells. b Each data set is pooled from four independent experiments with individual donors (n = 4, mean ± SEM; ns not significant, P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001); c The ratio of CD8+ versus CD4+ T cells after three rounds of antigen-specific stimulation (n = 3, mean ± SEM; ns not significant, P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01); d Proliferation of both CAR-T cells after three rounds of antigen-specific stimulation. The two groups of CAR-T cells were prestained with CFSE before the third stimulation, and then the stained CAR-T cells were cocultured with SK-HEP-1-GPC3 at a 1:1 effector-to-target ratio for 96 h. The intensity of CFSE in each group was measured by flow cytometry. e After three rounds of antigen-specific stimulation with SK-HEP-1-GPC3 cells, the expression of exhaustion biomarkers on the T-cell surface, including PD-1, TIM-3 and LAG-3, was determined using flow cytometry with the indicated antibodies; f Each data set is pooled from three independent experiments with individual donors (n = 3, mean ± SEM; ns not significant, P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001); g Cytokine release of the engineered T cells after three rounds of antigen-specific stimulation with SK-HEP-1-GPC3 cells. A total of 1 × 106 engineered T cells were cocultured with 1 × 106 tumor cells for 24 h. The levels of IL-2, IFN-γ and TNF-α in the supernatants were evaluated by ELISA (n = 6, mean ± SEM; ns not significant, P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

Freshly isolated CD3+ PBMCs often contain a naive T-cell subset [25]. Our ex vivo genetic modification and propagation of GPC3-28Z and GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells resulted in differentiation toward a central memory (Tcm) phenotype characterized by CD45RAnegCCR7+ (Fig. 2c, d). T cells with a central memory phenotype may be the most appropriate cell type for adoptive cell therapy because they can not only transfer instant antitumor immunity to patients but also endow them with immune memory to prevent cancer from recurring [2].

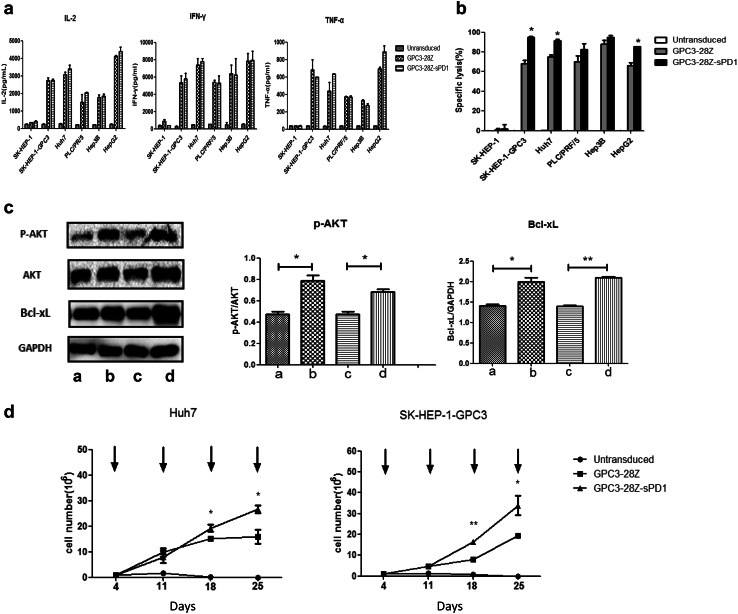

Cytokine release

The levels of IL-2, IFN-γ and TNF-α secreted by T cells were assayed after coculture with various HCC cell lines. As shown in Fig. 3a, in the presence of GPC3-positive HCC cells, levels of all of the cytokines were higher in CAR-T cells than in untransduced T cells. Only basal expression levels of IL-2, IFN-γ and TNF-α were detected in CAR-T cells cocultured with GPC3-negative SK-HEP-1 cells. Both GPC3-28Z and GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T-cell groups showed no significant differences at this time point. However, after three rounds of antigen-specific stimulation, the GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T-cell groups secreted higher levels of IL-2, IFN-γ and TNF-α than did GPC3-28Z T-cell groups, especially toward SK-HEP-1-GPC3 cells (Fig. 4g).

Fig. 3.

In vitro cytokine release and cytotoxicity of CAR-T against target cells and the behavior after coculture with SK-HEP-1-GPC3 or Huh7 cells. a Cytokine release of the engineered T cells. A total of 1 × 106 engineered T cells were cocultured with 1 × 106 tumor cells for 24 h. The levels of IL-2, IFN-γ and TNF-α in the supernatants were evaluated by ELISA; b Cytotoxicity of the engineered T cells against tumor cells. Untransduced, GPC3-28Z and GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells were cocultured with the various HCC cells at the indicated effector:target ratios for 72 h. Each data set is pooled from three independent experiments with individual donors (n = 12–15, mean ± SEM); c GPC3-28Z and GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells were cocultured with GPC3- and PD-L1-positive cells (Huh7 or SK-HEP-1-GPC3) for 48 h. Then, T cells were isolated and subjected to Western blot analysis to measure the expression levels of phospho-Akt and Bcl-xL. The densitometry quantification of the protein levels of phospho-Akt and Bcl-xL is shown. a: GPC3-28Z + Huh7, b: GPC3-28Z-sPD1 + Huh7, c: GPC3-28Z + SK-HEP-1-GPC3, d: GPC3-28Z-sPD1 + SK-HEP-1-GPC3. Data were quantitated, and expression relative to Akt and GAPDH was plotted. Each data set is pooled from three independent experiments with individual donors (n = 3, mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01); d Proliferation capacity of the engineered T cells. A total of 1 × 106 untransduced, GPC3-28Z and GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells were stimulated with freshly irradiated tumor cells every week. The numbers of viable T cells were counted twice a week, and the data were pooled from three independent experiments with individual donors (n = 9, mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

In vitro cytotoxicity of CAR-T cells toward HCC cells

The in vitro cytotoxicity of GPC3-28Z- and GPC3-28Z-sPD1-modified T cells was examined using an impedance-based tumor cell killing assay (xCELLigence). The results indicated that both CAR-T cell types could efficiently lyse GPC3-positive HCC cells, but not GPC3-negative SK-HEP-1 cells, whereas untransduced T cells could not initiate the specific lysis on any of the tumor cell lines (Fig. 3b). After 72 h of coculture, the cytotoxicity of GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells was significantly greater than that of GPC3-28Z T cells against SK-HEP-1-GPC3, Huh7 and HepG2 cells.

P-AKT and Bcl-xL expression

PI3K/Akt activation is a key downstream signal of CD28, while the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction blocks the CD28-mediated activation of PI3K and AKT [26]. On the other hand, given that the GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells proliferated much more than the GPC3-28Z T cells, we speculated that sPD1 protects CAR-T cells from apoptosis induced by repeated antigen stimulation. Consequently, we assessed the level of AKT phosphorylation and the expression levels of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-xL in both GPC3-28Z and GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells after coculture with SK-HEP-1-GPC3 or Huh7 cells. As expected, AKT phosphorylation and Bcl-xL expression were higher in GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells than in GPC3-28Z T cells (Fig. 3c), and these differences were significant (*P < 0.05).

Expansion capacity of CAR-T cells

The proliferation ability of T cells was examined after weekly stimulation with SK-HEP-1-GPC3 or Huh7 cells in the absence of exogenous cytokines. GPC3 and PD-L1 expression on the surface of HCC cells was verified (see also Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). We found that GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells showed a higher proliferation rate than GPC3-28Z T cells (Fig. 3d). After in vitro culture for 25 days, the former expanded approximately 30-fold, while the latter expanded approximately 20-fold. Both types of CAR-T cells showed higher expression levels after repetitive antigen-specific activation (Fig. 4a, b). As we reported previously, no untransduced T cells were maintained after 14 days due to insufficient antigen stimulation [2] (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

Next, PD-1, TIM-3 and LAG-3 expression on the T cells was detected (Fig. 4e, f). We found that after three rounds of antigen-specific stimulation with SK-HEP-1-GPC3, TIM-3 levels were not apparently different among untransduced, GPC3-28Z and GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells. However, PD-1 and LAG-3 expression on both types of CAR-T cells was upregulated after antigen-specific stimulation. These data indicated that the exhaustion stage occurred in CAR-T cells after repetitive antigen activation. Nevertheless, PD-1 levels were significantly lower in GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells than in the parent GPC3-28Z T cells, suggesting that the coexpression of sPD1 might have suppressed the expression of endogenous PD-1 (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Thus, GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells (31.33 ± 2.484%) also showed higher proliferation than GPC3-28Z T cells (20.00 ± 1.007%) after repetitive antigen-specific activation, as assessed with a carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-based proliferation assay (Fig. 4d).

Antitumor activities of CAR-T cells with or without sPD1

To further compare the in vivo cytotoxic activities of GPC3-28Z and GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells, NOD/SCID mice bearing established subcutaneous HCC xenografts were used. To assess the nonspecific cytotoxicity of CAR-T cells, GPC3-negative SK-HEP-1 xenografts were established as a parallel control. No inhibition of tumor growth was found in either type of CAR-T-treated tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 5a, d).

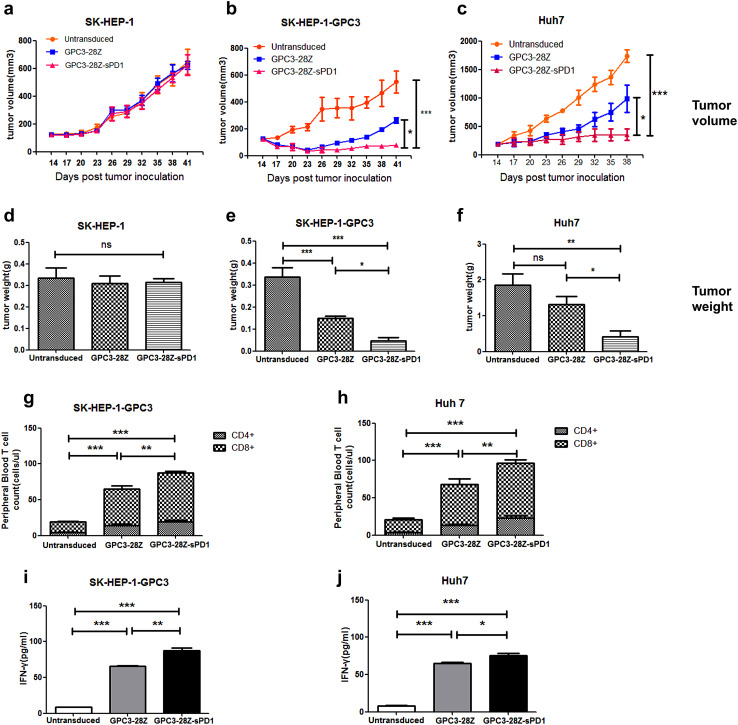

Fig. 5.

Antitumor activity of the modified T cells in established murine xenogeneic HCC models. To examine the unspecific cytotoxicity of CAR-T, a SK-HEP-1 xenograft model was established. No in vivo antitumor activity was observed after CAR-T injections (a); Mice bearing established SK-HEP-1-GPC3 (b) or Huh7 (c) xenografts were pretreated with cyclophosphamide (200 mg/ml). The next day, mice were infused with GPC3-28Z or GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells (8 × 106 CAR-T cells for SK-HEP-1-GPC3 xenograft models and 7 × 106 for Huh7 xenograft models). Control groups received untransduced T cells. The tumor volumes were measured with calipers every 3 days. On day 27, the mice were sacrificed, and tumor weight was measured (d–f). Quantitation of circulating human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from mice bearing SK-HEP-1-GPC3 (g) or Huh7 xenografts (h) treated with the indicated genetically modified T cells. The mean cell level (cells/µl ± SEM) in tumor-bearing mice treated by untransduced or modified T cells are shown. The level of IFN-γ in mouse serum was evaluated by ELISA in SK-HEP-1-GPC3 (i) or Huh7 (j) xenograft models. Each data set is pooled from 3 independent experiments with individual donors (n = 9–15, mean ± SEM; ns not significant, P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

With respect to mice bearing SK-HEP-1-GPC3 xenografts, both types of CAR-T cells potently retarded tumor growth at the early stage. Ten days after T-cell injection, the inhibition of tumor growth by GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells became markedly stronger than that by GPC3-28Z T cells (Fig. 5b).

Next, NOD/SCID mice bearing Huh7 xenografts were used to further evaluate the in vivo antitumor effect of CAR-T cells. During the first week, similar cytotoxic activities were observed in both CAR-T treated groups. However, unlike GPC3-28Z cells, GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells began to prominently suppress tumor growth 7 days after the CAR-T injection (Fig. 5c).

At the end of the experiment, for both xenograft models, the tumor weights of both CAR-T-treated groups were significantly lower than those of the group treated with untransduced T cells (Fig. 5e, f and see also Supplementary Fig. 4). Moreover, the tumor weights of the GPC3-28Z-sPD1 group were much lower than those of the GPC3-28Z group. These results suggested that sPD1 could enhance the in vivo antitumor activities of CAR-T cells.

T-cell persistence and Ki67 and granzyme B expression

Previous studies indicated that the persistence of transferred T cells in vivo was highly correlated with tumor regression [27]. Therefore, we detected circulating human T-cell levels in the peripheral blood of mice bearing established subcutaneous SK-HEP-1-GPC3 or Huh7 xenografts at 9 days after T-cell injection. We found that both types of CAR-T cells had better persistence in vivo than the untransduced T cells (Fig. 5g, h). More CAR-T cells were detected in the GPC3-28Z-sPD1 group than in the GPC3-28Z group (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). In addition, the IFN-γ level was much higher in the GPC3-28Z-sPD1 group than in the GPC3-28Z group (Fig. 5i, j), and this difference was statistically significant in the SK-HEP-1-GPC3 xenograft model (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

In immunohistochemical assays of tumor tissues, for both xenograft models, we found greater numbers of infiltrated T cells in the tumor tissues from the GPC3-28Z-sPD1 group than those from the GPC3-28Z group (Fig. 6a, b). This is consistent with the different numbers of circulating T cells in the peripheral blood. Next, the Ki67 staining intensity was determined, and the GPC3-28Z-sPD1 CAR-T cell treatment groups showed significantly lower staining intensity than the other two groups. In addition, the GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cell-treated group showed the highest level of granzyme B expression among the three groups. These results indicated that sPD1 prolonged CAR-T persistence and enhanced antitumor activity in vivo.

Fig. 6.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of CD3, Ki67 and granzyme B in tumor sections. a CD3, Ki67 and granzyme B detection on tumor sections from the SK-HEP-1-GPC3 xenograft model. CD3+ T cells were obvious in SK-HEP-1-GPC3 tumors treated with GPC3-28Z-sPD1 and GPC3-28Z T cells; Ki67 expression in the GPC3-28Z-sPD1 treatment group was significantly reduced, and granzyme B showed a higher expression in the GPC3-28Z-sPD1 treatment group than in the other two groups. b CD3, Ki67 and Granzyme B expression was detected in tumor sections after Huh7 xenografts. CD3+ T cells were found to be located in Huh7 tumor sites in CAR-T treated groups, and more cells were detected in GPC3-28Z-sPD1 treated mice; Ki67 expression in GPC3-28Z-sPD1 group showed an obvious decrease compared with GPC3-28Z and untransduced T cells; granzyme B expression was higher in the GPC3-28Z-sPD1 group than in the other two groups. Representative sections are shown at a magnification of ×400. Each data set is pooled from three independent experiments (n = 3, mean ± SEM; ns not significant, P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

Discussion

The increased expression of PD-1 on CAR-T cells correlated with their hypofunction. To overcome PD-1/PD-L1-mediated inhibition, several strategies targeting this pathway in CAR-T cells have been explored. One strategy is to combine CAR-T cells with anti-PD-1 antibody to increase their antitumor activity [28, 29]. However, it should be noted that systemic PD-1 blockade may lead to an imbalance in immunologic tolerance that results in an unchecked immune response. This may clinically manifest as autoimmune-like/inflammatory side effects [30]. The second way to block immune checkpoints is to use genetic engineering strategies, such as the CRISPR/Cas9 system, to generate PD-1-disrupted CAR-T cells [7, 31]. These studies suggest that PD-1 disruption augments CAR-T cell-mediated tumor cell killing in vitro and enhances the clearance of PD-L1+ tumor xenografts in vivo. In contrast, Odorizzi et al. [32] demonstrated that the genetic depletion of PD-1 in naive CD8+ T cells unexpectedly led to increased exhaustion and impaired CD8+ T-cell survival and function. Nevertheless, concerns persist regarding secondary mutations in regions not targeted by the single guide RNA [33]. Other strategies, including cell-intrinsic PD-1 shRNA, a PD-1 dominant negative receptor [34], anti-PD-L1 antibody secretion [35], an anti-PD-1 antibody [36] and PD-1 conversion to T-cell costimulatory receptors [6, 37, 38], have also been used to improve the antitumor activities of CAR-T cells. Each strategy has advantages and drawbacks. For instance, PD-L1 antibody secretion is good. However, because of the large size of the gene encoding the single chain, as well as the heavy chain, of the PD-L1 antibody, manufacturing this antibody for lentiviral transfection would be a burden. However, the sPD1 coding sequence is only 777 bp, which is very easy to coexpress with CAR using F2A as a cleavable linker. Additionally, unlike the PD-1-CD28 chimeric protein, sPD1 may help reactivate the other effector cells in the tumor tissues.

Our data demonstrated that the incorporation of sPD1 significantly increased the antitumor activities of CD28 domain-containing second-generation CAR-T cells. In our in vitro studies, we found that compared with control cells, both GPC3-28Z and GPC3-28Z-sPD1 CAR-T cells showed potent cytotoxicity against HCC cell lines. Although there was no significant advantage regarding cytotoxicity and cytokine release, GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells resulted in greater proliferation ability than GPC3-28Z T cells when repeated stimulation with GPC3+ PD-L1+ tumor cells. Further studies revealed that PD-1 expression on GPC3-28Z-sPD1 T cells was down-regulated, suggesting that secreted sPD1 could interact with PD-L1+ HCC cells and inhibit the expression of PD-1. In accordance with our results, anti-PD-L1 mAb-secreting CAR-T cells down-regulated PD-1 expression when they were cultured with PD-L1+ renal cell carcinoma cells [35]. According to a previous study, PD-1 influences T-cell activity by directly inhibiting PI3K [26]. Because the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway was blocked, the levels of AKT phosphorylation and the expression levels of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-xL were significantly increased in GPC3-28Z-sPD1 cells. These data suggested that sPD1 protects CAR-T cells from exhaustion when combating PD-L1+ target cells, but it could not enhance in vitro cytotoxicity within the short coculture time. There was less evidence to demonstrate whether CAR-T cells can directly inhibit tumor proliferation, as Ki67 expression in the tumor tissues of CAR-T cell-treated groups was decreased. Donskov et al. reported that low-dose IFN may lead to a decrease in Ki67 expression in renal cell carcinoma [39], and Bourouba et al. found that tumors treated with a TNF-α mAb displayed reduced Ki67 expression [40]. When CAR-T cells fight tumors, high levels of cytokine secretion may cause additive effects, one of which is a decrease in Ki67 expression. In accordance with our results, Ren et al. [31] found that CAR-T cells with PD-1 disruption showed robust in vitro antitumor activities, including lytic capacity, cytokine secretion and proliferation, which were as potent as those of wild CAR-T cells. In contrast, Levi J. Rupp et al. [7] reported that PD-L1+ tumor cells were killed more efficiently by anti-CD19 CAR-T cells with PD-1 disruption than by control CAR-T cells. This inconsistency may be correlated with T-cell exhaustion, as they did not examine PD-1, TIM-3 or LAG-3 expression on the T cells used to induce in vitro cytotoxicity. It has been reported that the overexpression of PD-L1 on tumor cells rendered them less susceptible to specific lysis by exhausted cytotoxic T cells [41]. However, PD-1/PD-L1 blockade could restore T–cell function.

Several reports indicate that PD-L1 expression is correlated with poor prognosis in HCC [42–44]. Recently, in a phase 1/2 study, treatment with nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody, resulted in substantial tumor reduction and in objective response rates of 15–20% in patients with advanced HCC [45]. These studies suggest that blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a feasible strategy for treating HCC. However, there are concerns about the toxicity of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies because drug-related death may occasionally occur [46]. Additionally, the combination of PD-1 antibodies with other immunotherapies, such as CTLA-4 antibodies, may exacerbate the toxicities [47]. Thus, selecting rational combinations of reagents to use with a PD-1 antibody is very important.

CAR-T cells have been regarded as a curative treatment modality for cancer. However, potential on-target off-tumor toxicities are major concerns. Therefore, the choice of a rational target is critical. In this study, GPC3 was chosen as the target because our previous study demonstrated that it is not expressed in normal tissues but is highly expressed in HCC tissues [2, 48]. Our recent study demonstrated that GPC3-28Z CAR-T cells were well tolerated by all HCC patients [3], further supporting the idea that GPC3 is a rational target for CAR-T cells. Therefore, sPD1-equipped GPC3-targeted CAR-T cells are a relatively safe treatment for patients with HCC, especially considering that sPD1 is produced in an autocrine manner.

In summary, our study demonstrated that CAR-T cells with sPD1 coexpression could increase antitumor activities and should be a promising treatment for HCC patients. In addition, considering the good safety profile of second-generation GPC3 CAR-T cells in the initial clinical studies, further clinical studies using GPC3 CAR-T cells carrying sPD1 are warranted.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Linguistic revision was done by Nature Research Editing Service.

Abbreviations

- Bcl-xL

B cell lymphoma-extra large

- CAR

Chimeric antigen receptor

- CFSE

Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester

- GPC3

Glypican-3

- LAG-3

Lymphocyte activation gene 3

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- MOI

Multiplicity of infection

- PBMCs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PD-1

Programmed cell death 1

- PD-L1

Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1

- P-AKT

Phosphorylated AKT

- sPD1

Soluble PD-1–CH3 fusion protein

- Tcm

Central memory T cell

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

- TIM-3

T cell/transmembrane, immunoglobulin, and mucin-1

Author Contributions

ZL conceived the ideas, designed the research and revised the manuscript; ZP designed subsequent experiments; ZP and SD performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript; BS performed molecular cloning work; HJ helped to perform the in vitro and in vivo work; ZS analyzed the data; YL, YW, HL, MY and XW assisted with the in vitro work.

Funding

This work was supported by the Supporting Programs of Shanghai Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan (No. 16DZ1910700), the “13th Five-Year Plan” National Science and Technology Major Project of China (2017ZX10203206006), the Collaborative Innovation Center for Translational Medicine at Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (TM201601), the Research Fund of the Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (No. 20174Y0178), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81472569).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Dr. Zonghai Li has ownership interests regarding GPC3-specific CAR-T cells with sPD1 coexpression. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval and ethical standards

The study was approved by the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee, approval number: SYXK (SH) 2017-0011. The protocols followed the appropriate guidelines and were approved by the Shanghai Medical Experimental Animal Care Commission.

Informed consent

The peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors were obtained by the Shanghai Blood Center from staff members of the research laboratory who volunteered to donate blood. They consented to the use of this blood for research purposes.

Footnotes

Zeyan Pan and Shengmeng Di contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Lim WA, June CH. The principles of engineering immune cells to treat cancer. Cell. 2017;168(4):724–740. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao H, Li K, Tu H, Pan X, Jiang H, Shi B, Kong J, Wang H, Yang S, Gu J, Li Z. Development of T cells redirected to glypican-3 for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(24):6418–6428. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhai B, Shi D, Gao H, Qi X, Jiang H, Zhang Y, Chi J, Ruan H, Wang H, Ru QC, Li Z. A phase I study of anti-GPC3 chimeric antigen receptor modified T cells (GPC3 CAR-T) in Chinese patients with refractory or relapsed GPC3 + hepatocellular carcinoma (r/r GPC3 + HCC) J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(suppl; abstr):3049. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.3049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katz SC, Burga RA, McCormack E, Wang LJ, Mooring W, Point GR, Khare PD, Thorn M, Ma Q, Stainken BF, Assanah EO, Davies R, Espat NJ, Junghans RP. Phase I hepatic immunotherapy for metastases study of intra-arterial chimeric antigen receptor-modified T-cell therapy for CEA + liver metastases. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(14):3149–3159. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang C, Wang Z, Yang Z, Wang M, Li S, Li Y, Zhang R, Xiong Z, Wei Z, Shen J, Luo Y, Zhang Q, Liu L, Qin H, Liu W, Wu F, Chen W, Pan F, Zhang X, Bie P, Liang H, Pecher G, Qian C. Phase I escalating-dose trial of CAR-T therapy targeting CEA + metastatic colorectal cancers. Mol Ther. 2017;25(5):1248–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu X, Ranganathan R, Jiang S, Fang C, Sun J, Kim S, Newick K, Lo A, June CH, Zhao Y, Moon EK. A chimeric switch-receptor targeting PD1 augments the efficacy of second-generation CAR T cells in advanced solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2016;76(6):1578–1590. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rupp LJ, Schumann K, Roybal KT, Gate RE, Ye CJ, Lim WA, Marson A. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated PD-1 disruption enhances anti-tumor efficacy of human chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):737. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00462-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freeman GJ, Long AJ, Iwai Y, Bourque K, Chernova T, Nishimura H, Fitz LJ, Malenkovich N, Okazaki T, Byrne MC, Horton HF, Fouser L, Carter L, Ling V, Bowman MR, Carreno BM, Collins M, Wood CR, Honjo T. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J Exp Med. 2000;192(7):1027–1034. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong RM, Scotland RR, Lau RL, Wang C, Korman AJ, Kast WM, Weber JS. Programmed death-1 blockade enhances expansion and functional capacity of human melanoma antigen-specific CTLs. Int Immunol. 2007;19(10):1223–1234. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu K, Kryczek I, Chen L, Zou W, Welling TH. Kupffer cell suppression of CD8 + T cells in human hepatocellular carcinoma is mediated by B7-H1/programmed death-1 interactions. Cancer Res. 2009;69(20):8067–8075. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-09-0901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmadzadeh M, Johnson LA, Heemskerk B, Wunderlich JR, Dudley ME, White DE, Rosenberg SA. Tumor antigen-specific CD8 T cells infiltrating the tumor express high levels of PD-1 and are functionally impaired. Blood. 2009;114(8):1537–1544. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Atkins MB, Leming PD, Spigel DR, Antonia SJ, Horn L, Drake CG, Pardoll DM, Chen L, Sharfman WH, Anders RA, Taube JM, McMiller TL, Xu H, Korman AJ, Jure-Kunkel M, Agrawal S, McDonald D, Kollia GD, Gupta A, Wigginton JM, Sznol M. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, Arance A, Grob JJ, Mortier L, Daud A, Carlino MS, McNeil C, Lotem M, Larkin J, Lorigan P, Neyns B, Blank CU, Hamid O, Mateus C, Shapira-Frommer R, Kosh M, Zhou H, Ibrahim N, Ebbinghaus S, Ribas A. Pembrolizumab versus Ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2521–2532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, Crino L, Eberhardt WE, Poddubskaya E, Antonia S, Pluzanski A, Vokes EE, Holgado E, Waterhouse D, Ready N, Gainor J, Aren Frontera O, Havel L, Steins M, Garassino MC, Aerts JG, Domine M, Paz-Ares L, Reck M, Baudelet C, Harbison CT, Lestini B, Spigel DR. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powles T, Eder JP, Fine GD, Braiteh FS, Loriot Y, Cruz C, Bellmunt J, Burris HA, Petrylak DP, Teng SL, Shen X, Boyd Z, Hegde PS, Chen DS, Vogelzang NJ. MPDL3280A (anti-PD-L1) treatment leads to clinical activity in metastatic bladder cancer. Nature. 2014;515(7528):558–562. doi: 10.1038/nature13904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gubin MM, Zhang X, Schuster H, Caron E, Ward JP, Noguchi T, Ivanova Y, Hundal J, Arthur CD, Krebber WJ, Mulder GE, Toebes M, Vesely MD, Lam SS, Korman AJ, Allison JP, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH, Pearce EL, Schumacher TN, Aebersold R, Rammensee HG, Melief CJ, Mardis ER, Gillanders WE, Artyomov MN, Schreiber RD. Checkpoint blockade cancer immunotherapy targets tumour-specific mutant antigens. Nature. 2014;515(7528):577–581. doi: 10.1038/nature13988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pauken KE, Wherry EJ. Overcoming T cell exhaustion in infection and cancer. Trends Immunol. 2015;36(4):265–276. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szymczak AL, Workman CJ, Wang Y, Vignali KM, Dilioglou S, Vanin EF, Vignali DA. Correction of multi-gene deficiency in vivo using a single ‘self-cleaving’ 2A peptide-based retroviral vector. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22(5):589–594. doi: 10.1038/nbt957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsu CY, Uludag H. A simple and rapid nonviral approach to efficiently transfect primary tissue-derived cells using polyethylenimine. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(5):935–945. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JH, Lee SR, Li LH, Park HJ, Park JH, Lee KY, Kim MK, Shin BA, Choi SY. High cleavage efficiency of a 2A peptide derived from porcine teschovirus-1 in human cell lines, zebrafish and mice. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Neut Kolfschoten M, Schuurman J, Losen M, Bleeker WK, Martinez-Martinez P, Vermeulen E, den Bleker TH, Wiegman L, Vink T, Aarden LA, De Baets MH, van de Winkel JG, Aalberse RC, Parren PW. Anti-inflammatory activity of human IgG4 antibodies by dynamic Fab arm exchange. Science. 2007;317(5844):1554–1557. doi: 10.1126/science.1144603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blom N, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Gupta R, Gammeltoft S, Brunak S. Prediction of post-translational glycosylation and phosphorylation of proteins from the amino acid sequence. Proteomics. 2004;4(6):1633–1649. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hart GW. Dynamic O-linked glycosylation of nuclear and cytoskeletal proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:315–335. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shindo G, Endo T, Onda M, Goto S, Miyamoto Y, Kaneko T. Is the CD4/CD8 ratio an effective indicator for clinical estimation of adoptive immunotherapy for cancer treatment? JCT. 2013;4(8):1382–1390. doi: 10.4236/jct.2013.48164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geginat J, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Proliferation and differentiation potential of human CD8 + memory T-cell subsets in response to antigen or homeostatic cytokines. Blood. 2003;101(11):4260–4266. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parry RV, Chemnitz JM, Frauwirth KA, Lanfranco AR, Braunstein I, Kobayashi SV, Linsley PS, Thompson CB, Riley JL. CTLA-4 and PD-1 receptors inhibit T-cell activation by distinct mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(21):9543–9553. doi: 10.1128/mcb.25.21.9543-9553.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chapuis AG, Ragnarsson GB, Nguyen HN, Chaney CN, Pufnock JS, Schmitt TM, Duerkopp N, Roberts IM, Pogosov GL, Ho WY, Ochsenreither S, Wolfl M, Bar M, Radich JP, Yee C, Greenberg PD. Transferred WT1-reactive CD8 + T cells can mediate antileukemic activity and persist in post-transplant patients. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(174):174ra127. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scarfo I, Maus MV. Current approaches to increase CAR T cell potency in solid tumors: targeting the tumor microenvironment. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:28. doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0230-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.John LB, Devaud C, Duong CP, Yong CS, Beavis PA, Haynes NM, Chow MT, Smyth MJ, Kershaw MH, Darcy PK. Anti-PD-1 antibody therapy potently enhances the eradication of established tumors by gene-modified T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(20):5636–5646. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, Connell LC, Schindler K, Lacouture ME, Postow MA, Wolchok JD. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(12):2375–2391. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ren J, Liu X, Fang C, Jiang S, June CH, Zhao Y. Multiplex genome editing to generate universal CAR T cells resistant to PD1 inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(9):2255–2266. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Odorizzi PM, Pauken KE, Paley MA, Sharpe A, Wherry EJ. Genetic absence of PD-1 promotes accumulation of terminally differentiated exhausted CD8 + T cells. J Exp Med. 2015;212(7):1125–1137. doi: 10.1084/jem.20142237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schaefer KA, Wu WH, Colgan DF, Tsang SH, Bassuk AG, Mahajan VB. Unexpected mutations after CRISPR-Cas9 editing in vivo. Nat Methods. 2017;14(6):547–548. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cherkassky L, Morello A, Villena-Vargas J, Feng Y, Dimitrov DS, Jones DR, Sadelain M, Adusumilli PS. Human CAR T cells with cell-intrinsic PD-1 checkpoint blockade resist tumor-mediated inhibition. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(8):3130–3144. doi: 10.1172/jci83092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suarez ER, Chang de K, Sun J, Sui J, Freeman GJ, Signoretti S, Zhu Q, Marasco WA. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells secreting anti-PD-L1 antibodies more effectively regress renal cell carcinoma in a humanized mouse model. Oncotarget. 2016;7(23):34341–34355. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li S, Siriwon N, Zhang X, Yang S, Jin T, He F, Kim YJ, Mac J, Lu Z, Wang S, Han X, Wang P. Enhanced cancer immunotherapy by chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells engineered to secrete checkpoint inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;15(22):6982–6992. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang X, Li Q, Zhu Y, Zheng D, Dai J, Ni W, Wei J, Xue Y, Chen K, Hou W, Zhang C, Feng X, Liang Y. The advantages of PD1 activating chimeric receptor (PD1-ACR) engineered lymphocytes for PDL1(+) cancer therapy. Am J Transl Res. 2015;7(3):460–473. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobold S, Grassmann S, Chaloupka M, Lampert C, Wenk S, Kraus F, Rapp M, Duwell P, Zeng Y, Schmollinger JC, Schnurr M, Endres S, Rothenfusser S (2015) Impact of a new fusion receptor on PD-1-mediated immunosuppression in adoptive T cell therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 107(8). 10.1093/jnci/djv146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Donskov F, Marcussen N, Hokland M, Fisker R, Madsen HH, von der Maase H. In vivo assessment of the antiproliferative properties of interferon-alpha during immunotherapy: Ki-67 (MIB-1) in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(3):626–631. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bourouba M, Zergoun AA, Maffei JS, Chila D, Djennaoui D, Asselah F, Amir-Tidadini ZC, Touil-Boukoffa C, Zaman MH. TNFalpha antagonization alters NOS2 dependent nasopharyngeal carcinoma tumor growth. Cytokine. 2015;74(1):157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang Y, Li Y, Zhu B. T-cell exhaustion in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1792. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao Q, Wang XY, Qiu SJ, Yamato I, Sho M, Nakajima Y, Zhou J, Li BZ, Shi YH, Xiao YS, Xu Y, Fan J. Overexpression of PD-L1 significantly associates with tumor aggressiveness and postoperative recurrence in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(3):971–979. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuang DM, Zhao QY, Peng C, Xu J, Zhang JP, Wu CY, Zheng LM. Activated monocytes in peritumoral stroma of hepatocellular carcinoma foster immune privilege and disease progression through PD-L1. J Exp Med. 2009;206(6):1327–1337. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi F, Shi M, Zeng Z, Qi R-Z, Liu Z-W, Zhang J-Y, Yang Y-P, Tien P, Wang F-S. PD-1 and PD-L1 upregulation promotes CD8+ T-cell apoptosis and postoperative recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:887–896. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, Crocenzi TS, Kudo M, Hsu C, Kim TY, Choo SP, Trojan J, Welling THR, Meyer T, Kang YK, Yeo W, Chopra A, Anderson J, Dela Cruz C, Lang L, Neely J, Tang H, Dastani HB, Melero I. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10088):2492–2502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31046-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Swaika A, Hammond WA, Joseph RW. Current state of anti-PD-L1 and anti-PD-1 agents in cancer therapy. Mol Immunol. 2015;67(2 Pt A):4–17. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Collins LK, Chapman MS, Carter JB, Samie FH. Cutaneous adverse effects of the immune checkpoint inhibitors. Curr Probl Cancer. 2017;41(2):125–128. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bi Y, Jiang H, Wang P, Song B, Wang H, Kong X, Li Z. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with a GPC3-targeted bispecific T cell engager. Oncotarget. 2017;8(32):52866–52876. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.