Abstract

Treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) represents a highly unmet medical need. Here, we discuss the results and therapeutic potential of first- and second-generation immunomodulatory antibodies targeting distinct immune checkpoints for the treatment of MPM, as well as their prospective therapeutic role in combination strategies. We also discuss the role of appropriate radiological criteria of response for MPM and the potential need of ad hoc criteria of disease evaluation in MPM patients undergoing treatment with immunotherapeutic agents.

Keywords: Mesothelioma, Immune checkpoint, Immunotherapy, NIBIT-2016

Introduction

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is an aggressive, fatal tumour, and the incidence of MPM has been increasing worldwide due to the widespread exposure to asbestos in the past [1]. The long latency period, which is typically caused by the insidious pattern of MPM local spreading, results in patients with an advanced stage of disease at diagnosis, thereby limiting a potentially curative surgical approach in a minority of patients [2]. Medical treatment based on cisplatin and pemetrexed combination has been set as the standard first-line approach for MPM patients. However, this treatment remains largely unsatisfactory, with a median overall survival (OS) ranging from 9 to 12 months [3]. More recently, an improvement in OS for newly diagnosed MPM patients treated with chemotherapy plus bevacizumab has been reported [4]. However, this regimen is far from being considered a new standard of care. The prognosis of MPM patients who relapse to a first-line treatment is dramatically dismal. No therapies provide survival benefits in this setting of disease, and there are no approved agents following progression of a first-line regimen [5]. Therefore, novel therapeutic approaches are needed, and immunotherapy is being extensively explored in MPM.

Role of anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) blockade

In the last few years, immunotherapy with immunomodulatory monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) directed against immune checkpoint(s) inhibitors has proven to represent a promising strategy to fight cancer, and it is now an integral part of the therapeutic armamentarium in different tumour types [6]. CTLA-4, member of the CD28 family of receptors, is expressed on the surface of activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as well as on regulatory T cells [7]. CTLA-4 plays a physiological inhibitory effect on T-cell activation by binding to B7 ligand (CD80 or CD86) expressed on antigen-presenting cells, thus reducing CD28-dependent costimulation and mediating direct inhibitory effects on the MHC-TCR pathway [7]. By blocking CTLA-4, anti-CTLA-4 mAbs prevent its binding to B7, thus allowing T-cell activation. Anti-CTLA-4 mAbs are the prototype of a growing family of immunomodulatory mAbs that induce long-term disease control and significantly prolong survival in metastatic melanoma patients. This initial evidence prompted the use of anti-CTLA-4 mAbs in other cancer histotypes [8, 9].

The highly immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment of MPM indicates a potential clinical benefit from novel immunotherapeutic approaches with anti-checkpoint mAbs [10, 11]. Based on this notion, the investigator-initiated phase 2 study MESOT-TREM-2008 (Clinical trial ID: NCT01649024) was designed to explore the activity of the anti-CTLA-4 mAb tremelimumab in the second-line treatment of MPM and peritoneal mesothelioma patients. In this first study, tremelimumab, given at a dose of 15 mg/kg intravenous (IV) every 90 days, showed the initial signs of clinical activity in terms of long-lasting disease control and a 2-year survival rate in 31 and 36% of mesothelioma patients, respectively [12]. Based on these clinical findings and on pharmacokinetic data [13], the efficacy and safety of an intensified dosing schedule of tremelimumab was subsequently explored in the phase 2, single-arm MESOT-TREM-2012 study (Clinical trial ID: NCT01655888) [14]. Twenty-nine MPM or peritoneal mesothelioma patients progressive to a platinum-based chemotherapy regimen were enrolled in the study. Four immune-related (ir) partial responses (PRs) (14%), an ir-disease control rate (DCR) of 52%, a median OS of 11.3 months (95% CI 3.4–19.2), and a manageable safety profile were observed [14]. These encouraging results contributed to a further evaluation of tremelimumab in the double-blinded, multicenter, randomized DETERMINE study (Clinical trial ID: NCT01843374) in unresectable mesothelioma subjects, including 564 MPM or peritoneal mesothelioma patients progressive to 1 or 2 prior systemic treatments. Unfortunately, tremelimumab failed to demonstrate an improvement in OS (primary endpoint of the study) compared to the placebo arm [15]. The safety profile was consistent with that usually observed with CTLA-4 inhibitors. In particular, grade 3 or higher treatment-related toxicity was observed in 29% of patients treated with tremelimumab. A different site experience with checkpoint inhibitor treatment and patient management during treatment at the different centers partly contributed to the failure of the study. Nevertheless, malignant mesothelioma has a relatively low tumour mutation burden [16], which may limit the activity of tremelimumab utilized in monotherapy in mesothelioma patients.

Evolving role of immune checkpoint blockade in MPM-targeting programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) or its main ligand (PD-L1)

Despite the fact that clinical benefits are limited to a proportion of patients, results from the use of anti-CTLA-4 mAbs have suggested that induction of the immune system may lead to an effective anti-tumour immune response in cancer patients. Indeed, in the last few years, there has been increased development of immunomodulatory mAbs targeting additional immune checkpoints, particularly those directed against PD-1 or PD-L1 utilized in different tumour types [17].

PD-1 is a transmembrane inhibitory receptor expressed by activated T, B, and natural killer cells that negatively regulates immune responses by binding its main ligands, namely PD-L1 or PD-L2. Immunomodulatory mAbs targeting PD-1, or its main ligand PD-L1, de-repress T-cell activation, thereby inducing an anti-tumour immune response [18].

The clinical success achieved with mAbs directed against the PD-1/PD-L1 axis in a variety of malignancies, including non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, kidney cancer, bladder cancer, high instability microsatellite cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, head and neck cancer, and Merkel carcinoma, has also prompted their use in clinical trials in MPM. Moreover, it has been reported that PD-1 is expressed in up to 40% of pleural MPM samples, especially sarcomatoid histotypes, and its expression has been associated with poor prognosis [19–22]. The initial data generated in Phase I/II clinical studies have provided evidence for PD-1/PD-L1 blocking mAbs in pre-treated MPM patients. Consistently, in the Phase 1b multicohort study KEYNOTE-028, the anti-PD-1 pembrolizumab at a dose of 10 mg/kg IV [q2 weeks (wks)] induced an objective response rate (ORR) (according to RECIST 1.1 criteria) and a DCR of 20% and 72%, respectively, in pre-treated MPM patients with PD-L1-positive tumours (score ≥ 1%). Interestingly, the median OS was 18 months, and the 1-year survival was 62.6% [23]. In an additional Phase II study, pembrolizumab at a dose of 200 mg IV (q3 wks) induced an ORR and a DCR of 21 and 80% (based on m-RECIST criteria), respectively, in pre-treated MPM patients unselected for PD-L1 expression. Promising results have also been reported in the NIVO-MES Phase II study with the anti-PD-1 mAb nivolumab at 3 mg/kg IV (q2 wks), with ORR and DCR values of 24 and 50%, respectively, for pre-treated MPM patients per m-RECIST criteria [24]. Finally, in the Phase I multicohort Javelin study, the anti-PD-L1 mAb avelumab administered at a dose of 10-mg/kg IV (q2 wks) induced ORR and DCR values of 9.4 and 56.6%, respectively, for pre-treated MPM patients unselected for PD-L1 expression as evaluated per m-RECIST [25].

Although targeting of the PD-1/PD-L1 axis in MPM may be a potentially promising therapeutic approach, results from the early phase studies have to be considered with caution, because they are still quite preliminary, different radiological evaluation criteria were utilized, and most are still ongoing. Several clinical studies are in progress to corroborate the activity of anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 mAbs in MPM patients, including the Phase III, randomized, double blind CONFIRM study, investigating the activity of nivolumab at 240-mg iv (q2 wks) versus placebo in MPM patients who progressed to more than two lines of treatment (Clinical trial ID: NCT03063450).

Immune checkpoint blockade for MPM: the future ahead

Although long-lasting disease control is achievable in a proportion of treated patients, most of the patients eventually relapse or are refractory to treatment when checkpoint inhibitors are utilized in monotherapy. Therefore, great efforts are currently focused on combination regimens aimed at overcoming the intrinsic or acquired immune-resistance of MPM, thus extending the effectiveness of the treatment to a larger patient population.

CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 are non-redundant but cooperative pathways as they act in two different phases of T-cell activation. Pre-clinical and clinical evidence have shown an additive or synergistic activity of anti-CTLA-4 mAbs in combination with anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 mAbs. Consistently, pivotal clinical studies have demonstrated greater efficacy of nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab compared to nivolumab or ipilimumab utilized alone in metastatic melanoma patients, albeit with increased toxicity [26, 27]. Of note, the improvement of progression-free survival (PFS) obtained from ipilimumab combined with nivolumab has also been observed in patients with PD-L1-negative tumours [27]. Based on these initial results, increasing numbers of clinical trials are currently investigating the efficacy of combination regimens in a variety of tumour types. Seeking to assess the therapeutic potential of blocking CTLA-4 in combination with PD-L1 in malignant mesothelioma, the phase II NIBIT-MESO-1 study has been designed by the NIBIT Foundation (Clinical trial ID: NCT02588131). In this study, the activity and safety of tremelimumab in combination with the anti-PD-L1 mAb durvalumab have been investigated in the first- and second-line treatment for MPM or peritoneal mesothelioma patients. Tremelimumab was given at 1 mg/kg IV every 4 wks for 4 doses in combination with durvalumab at 20 mg/kg IV every 4 wks for 4 doses during the induction phase followed by treatment with durvalumab alone at the same dose and scheduled for an additional 9 doses in a maintenance phase. Patients who relapsed in the maintenance or in the follow-up phase had the chance to be retreated, restarting treatment from the combination regimen. The primary endpoint of the NIBIT-MESO-I study is to investigate the immune-related (ir)-ORR (per m-RECIST) with secondary endpoints of safety, ir-PFS, ir-DCR, and OS. The pre-specified safety analysis performed on the first 10 patients did not show significant treatment-related side effects. Therefore, the study continued and completed the enrolment of 40 mesothelioma patients. As of April 2017, 17% of patients experienced grade 3–4 treatment-related toxicity. Overall, irAEs were generally manageable and reversible per protocol guidelines [28], and 3 patients (7.5%) were discontinued due to irAEs (1 thrombocytopenia, 1 limbic encephalitis, and 1 liver toxicity) [28]. The efficacy analysis of this study has been recently reported, showing an ir-ORR and ir-DCR of 27.5 and 65%, respectively, for mesothelioma patients with a median OS of 16.6 months [29].

The growing interest for the combination regimen with immune checkpoint blocking mAbs in mesothelioma patients promoted the Phase II, randomized, non-comparative MAPS-2 study (Clinical trial ID: NCT02716272), investigating the activity of nivolumab utilized alone or combined with ipilimumab in the second- or third-line treatment for MPM patients. Encouraging results have been recently reported from this study, with a DCR at 12 wks (per m-RECIST) of 44 and 50% for patients treated with nivolumab alone or in combination with ipilimumab, respectively. Moreover, a median OS of 10.4 months was observed in the monotherapy arm, while it was not yet reached in the combination regimen [30]. In addition, the ongoing Phase III Checkmate-743 study is investigating the efficacy of nivolumab combined with ipilimumab compared to a platinum-based regimen in the first-line MPM treatment (Clinical trial ID: NCT02899299). Altogether, the studies combining treatment with anti-CTLA-4 and -PD-1/-PD-L1 mAbs will provide additional support for the activity of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 mAb combination regimens in this hard-to-treat disease.

Furthermore, increasing numbers of combination regimens of immune checkpoint inhibitors with other therapeutic strategies, such as chemotherapy (Clinical trial ID: NCT02784171), mesothelin targeting (Clinical trial ID: NCT02341625), or vaccines (Clinical trial ID: NCT03175172), have recently been initiated.

Immune checkpoint blockade therapy of MPM: a radiological challenge

A reproducible assessment of tumour response to treatment is still a major challenge in MPM due to its peculiar growth pattern. Bi-dimensional response criteria established by the World Health Organization (WHO) or uni-dimensional criteria according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumour (RECIST), both utilized for many years in different tumour types, are poorly suited for the growth pattern of MPM [31]. Therefore, the modified RECIST (m-RECIST) has been developed and is currently utilized as the standard radiological criteria for MPM [32]. However, m-RECIST shows a high degree of inter-operator variability and, thus, is not completely satisfactory. A potential improvement in the radiological assessment using volumetric imaging in MPM has also been proposed and is under evaluation [33].

In the last decade, the radiological scenario of tumour assessment underwent a profound change due to the exponential clinical development of immunotherapeutic agents that have also become the standard of care in a variety of malignancies in different countries. As opposed to cytotoxic agents that target tumour cells directly, which may induce rapid objective responses, immunotherapeutic agents are mainly directed against immune cells and exert indirect effects on tumour cells with distinct characteristics in the clinic. This different mechanism of action can translate into the distinct kinetics of clinical responses well established in the CTLA-4 development era as follows: (1) the potential for delayed objective responses, because the immune activation can take time; and (2) T cells recruited to tumours may increase tumour volume before they can shrink it. These peculiar kinetics responses have led to defining novel radiological criteria for tumour assessment in the course of immunotherapy, which are the so-called immune-related response criteria (ir-RC) [34]. The main concepts of ir-RC are as follows: (1) confirming progression via a subsequent scan performed at least 4–6 weeks later to detect delayed responses and/or pseudo-progression; (2) measuring new lesions to include them into the total tumour volume; (3) accounting for durable stable disease as a clinical benefit; and (4) treating beyond conventional progression if the clinical condition allows. The broad use of the ir-RC, which was developed primarily in metastatic melanoma, has allowed for a more comprehensive evaluation of immunotherapies in clinical trials, suggesting that their concepts can be applied to the RECIST/RECIST 1.1 (thus generating the ir-RECIST) and utilized in other solid tumours [35]. Multiple variations of “immune criteria” used across trials have led to the proposal of the immune-RECIST (i-RECIST) by the international consensus RECIST working to standardize and validate response criteria utilized within clinical trials [36]. According to i-RECIST and in contrast to RECIST-1.1 (the currently most used response criteria for conventional chemotherapy of solid tumours), an initially unconfirmed progressive disease (iUPD) requires confirmation (iCPD) in clinically stable patients by subsequent control imaging after 4–8 weeks, and new lesions are separately assessed within i-RECIST. Similarly, there is a need to apply ir-criteria in the course of immunotherapeutic treatment for MPM. These criteria may be integrated into the m-RECIST, thus generating the “ir-m-RECIST” for MPM. The latter were utilized for the first time in the NIBIT-MESO-1 study [29].

Additional critical aspects to further improve the accuracy and reproducibility of tumour response evaluation in MPM are represented by the radiologist expertise and by the development of alternative assessment modalities. This latter aspect might include measuring tumour volume by novel software, using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and using whole-body-MR imaging, including diffusion-weighted whole-body imaging with background-body-signal-suppression (DWIBS) [37]. More recently, metabolic imaging is currently under investigation to explore the possible role of non-FDG radiotracers (the so-called immuno-PET), such as radiotracer mAbs directed against effector T-cell subpopulations (i.e., CD8), which can identify lymphocyte infiltrates [38–41].

Clinical cases

The following clinical cases of MPM patients are representative examples of different kinetics of tumour responses that may be observed in the course of treatment with checkpoint blocking mAbs. Of note, atypical tumour responses are more frequent with anti-CTLA-4 mAbs than with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 mAbs alone or in combination [42].

Patient case 1

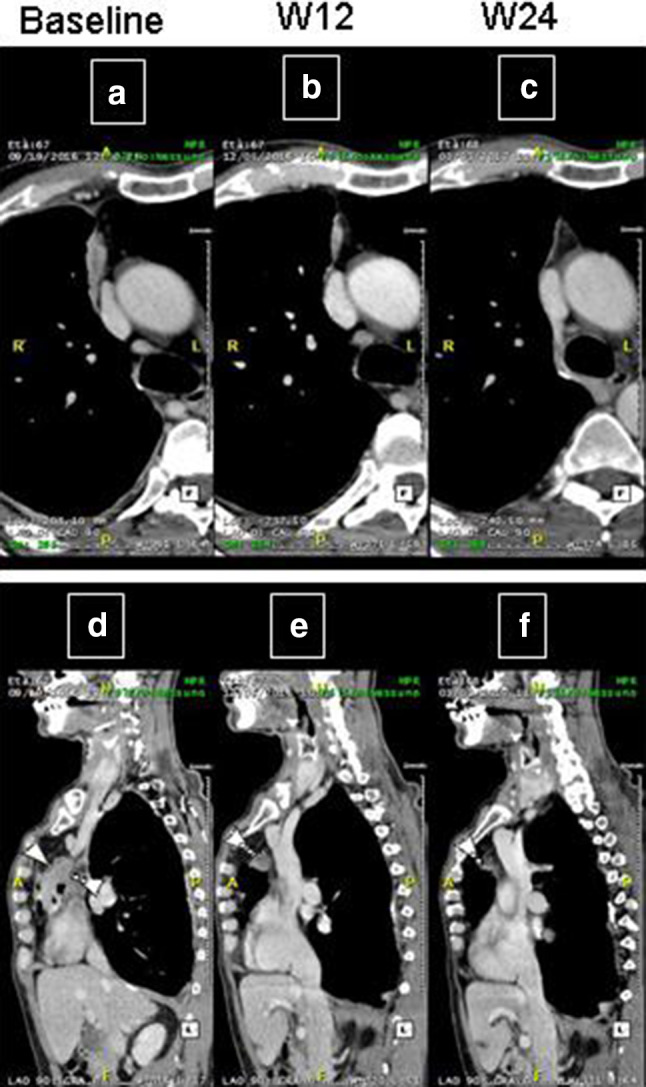

A 67-year-old man without a significant medical history was diagnosed with MPM, specifically the biphasic subtype. The patient refused the first-line chemotherapy and was, therefore, enrolled in the NIBIT-MESO-1 study. Computed tomography (CT) scan evaluation at W12 (Fig. 1b, e) showed PR (per ir-m-RECIST) (Fig. 1a, b, d, e) that persisted at W24 (Fig. 1c, f). The patient is still being treated in April 2018. This case clearly demonstrates that a rapid objective response can be observed during immunotherapy, in particular within combination regimens with immune checkpoint inhibitors, thus mimicking those usually observed with cytotoxic or biological agents.

Fig. 1.

CT scan in axial plan (a–c) and multiplanar reformatting sagittal plane (d–f) of an MPM patient treated with tremelimumab and durvalumab and who achieved rapid PR. Tumour assessment was completed at baseline (a, d), W12 (b, e) and W24 (c, f). The patient achieved a rapid PR at W12 (b, e), persisting at W24 (c, f)

Patient case 2

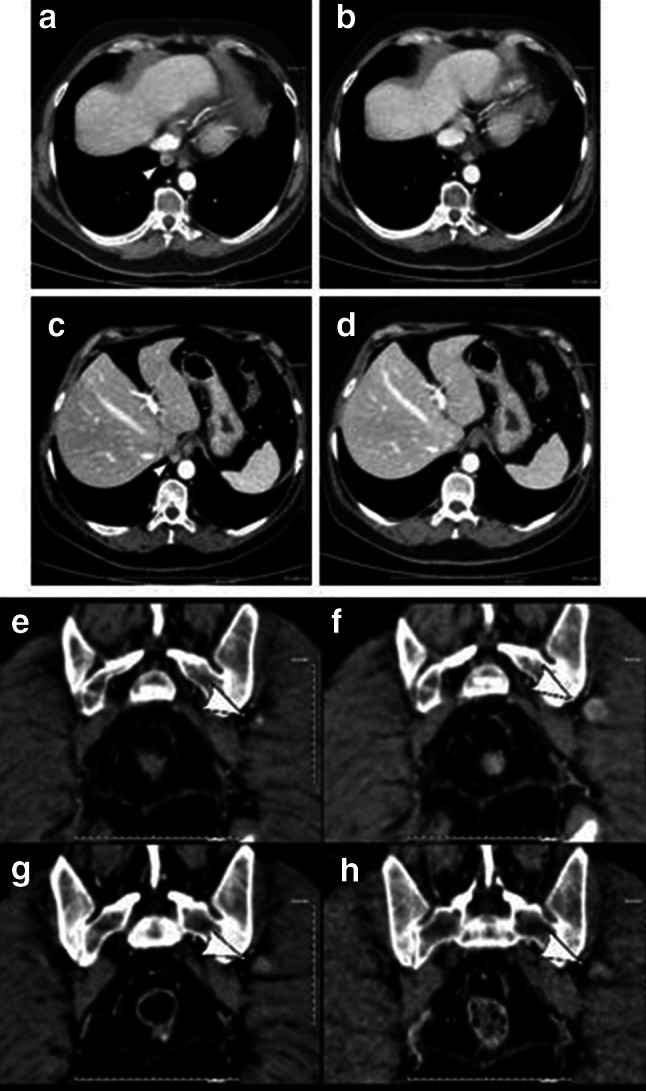

A 64-year-old man without a significant medical history was diagnosed with MPM, specifically the epithelial subtype. Following progression to a first-line carboplatin/pemetrexed-based regimen, he received treatment within the NIBIT-MESO-1 study. He had no clinically significant side effects and received 13 doses overall. The CT scan evaluation at W12 showed PR (per ir-m-RECIST) (Fig. 2a–f) with the disappearance of two lesions (b, d) and an increase in a soft tissue lesion (Fig. 2f). The CT scan performed at W24 showed a persisting PR of pleural lesions, and a significant decrease of the soft tissue (Fig. 2g) persisted at W36 (Fig. 2h). This case clearly shows an unusual tumour response to treatment and suggests that ir-criteria should be considered in the course of treatment with immunotherapeutic agents.

Fig. 2.

CT scan in axial plan of an MPM patient treated with tremelimumab and durvalumab and who had a mixed response. Tumour assessment was completed at baseline (a, c, e), W12 (b, d, f), W24 (g), and W36 (h). The patient achieved a PR for pleural lesions with the disappearance of two lesions (b, d) and an increase of a lesion in soft tissue (f) at W12. CT scan at W24 shows the persistent overall pleural PR and a significant decrease of the lesion in soft tissue (g), persisting at W36 (h)

Patient case 3

A 59-year-old male without a significant medical history was diagnosed with MPM, specifically the epithelial subtype. Following progression to a first-line cisplatin/pemetrexed regimen, he received treatment with tremelimumab within the DETERMINE study. He had no side effects, except for thyroiditis, which was controlled with hormone replacement therapy. The CT scan evaluation at W6 (per m-RECIST) showed progression of the disease (PD) (Fig. 3a, b). As per the study protocol, the patient received additional tremelimumab administrations. The CT scan performed at W12 showed stable disease (SD) followed by PR at W80 (Fig. 3c). Four months later (W96), new peritoneal lesions were observed, and the patient deteriorated. Therefore, tremelimumab was stopped, and the patient restarted treatment with cisplatinum/pemetrexed, which resulted in a PR. This case demonstrates a delayed tumour response to tremelimumab, which may be captured using ir-criteria.

Fig. 3.

CT scan in axial plan of an MPM patient treated with tremelimumab and who had a delayed objective response. Tumour assessment was completed at baseline (a), W6 (b), and W80 (c). The patient achieved a PR (c) at W80 after the initial PD at W6 (b)

Conclusions

There is much to be gained in the therapeutic landscape of MPM; however, immune checkpoint blocking mAbs are beginning to show clinical potential, fuelling additional studies that will further explore their role in this deadly disease. Furthermore, a broader understanding of the immune and inflammatory responses to treatment will allow a better development of potential immunotherapy with checkpoint blocking mAbs in MPM through improved design of the combined/sequential therapies.

Abbreviations

- CT

Computed tomography

- CTLA-4

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4

- DCR

Disease control rate

- ir

Immune-related

- ir-RC

Immune-related response criteria

- iv

Intravenous

- mAb

Monoclonal antibody

- m-RECIST

Modified response evaluation criteria in solid tumours

- MPM

Malignant pleural mesothelioma

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ORR

Objective response rate

- OS

Overall survival

- PD

Progression of disease

- PD-1

Programmed cell death-1

- PD-L1

Programmed cell death ligand-1

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- PR

Partial response

- RECIST

Response evaluation criteria in solid tumours

- SD

Stable disease

- W

Week

- WHO

World Health Organization

- Wks

Weeks

Authors’ contributions

Luana Calabrò, Aldo Morra, Robin Cornelissen, Joachim Aerts, and Michele Maio wrote the manuscript. All co-authors supervised and critically contributed to the final version of the manuscript, and they approved the final version.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (IG15373, 2014).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Luana Calabrò served on the advisory board of Bristol Myers Squibb; Aldo Morra declares no conflict of interest; Robin Cornelissen served on advisory boards of Boehringer-Ingelheim, Roche, and Lilly; Joachim Aerts served on advisory boards of Eli-Lilly Bristol Myers Squibb, Roche-Genetech, Astra-Zeneca, MSD Sharp & Dohme, and Boehringer Ingelheim, and is a stock owner of Amphera Immunotherapy; Michele Maio served on advisory boards of Bristol Myers Squibb, Roche-Genentech, and AstraZeneca-MedImmune.

Research involving human participants

We obtained oral consent from the three patients (reported in the clinical cases) for the description and publication of their cases (including figures).

References

- 1.Delgermaa V, Takahashi K, Park EK, Le GV, Hara T, Sorahan T. Global mesothelioma deaths reported to the World Health Organization between 1994 and 2008. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:716–724. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.086678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baas P, Fennell D, Kerr KM, Van Schil PE, Haas RL, Peters S. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(5 suppl):v31–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogelzang NJ, Rusthoven JJ, Symanowski J, Denham C, Kaukel E, Ruffie P, Gatzemeier U, Boyer M, Emri S, Manegold C, Niyikiza C, Paoletti P. Phase III study of pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2636–2644. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zalcman G, Mazieres J, Margery J, Greillier R, Audigier-Valette C, Moro-Sibilot D, Molinier O, Corre R, Monnet I, Gounant V, Rivièr F, Janicot H, Gervais R, Locher C, Milleron B, Tran Q, Lebitasy MP, Morin F, Creveuil C, Parienti JJ, Scherpereel A, French Cooperative Thoracic Intergroup (IFCT) Bevacizumab for newly diagnosed pleural mesothelioma in the Mesothelioma Avastin Cisplatin Pemetrexed Study (MAPS): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10026):1405–1414. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krug LM, Kindler HL, Calvert H, Manegold C, Tsao AS, Fennell D, Öhman R, Plummer R, Eberhardt WE, Fukuoka K, Gaafar RM, Lafitte JJ, Hillerdal G, Chu Q, Buikhuisen WA, Lubiniecki GM, Sun X, Smith M, Baas P. Vorinostat in patients with advanced malignant pleural mesothelioma who have progressed on previous chemotherapy (VANTAGE-014): a phase 3, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(4):447–456. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Postow MA, Callahan MK, Wolchok JD. Immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(17):1974–1982. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyi C, Postow MA. Immune checkpoint inhibitor combinations in solid tumors: opportunities and challenges. Immunotherapy. 2016;8(7):821–837. doi: 10.2217/imt-2016-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calabrò L, Danielli R, Sigalotti L, Maio M. Clinical studies with anti-CTLA-4 antibodies in non-melanoma indications. Semin Oncol. 2010;37(5):460–467. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maio M, Grob JJ, Aamdal S, Bondarenko I, Robert C, Thomas L, Garbe C, Chiarion-Sileni V, Testori A, Chen TT, Tschaika M, Wolchok JD. Five-year survival rates for treatment-naive patients with advanced melanoma who received ipilimumab plus dacarbazine in a phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(10):1191–1196. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.6018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bograd AJ, Suzuki K, Vertes E, Colovos C, Morales EA, Sadelain M, Adusumilli PS. Immune responses and immunotherapeutic interventions in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60(11):1509–1527. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1103-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornelissen R, Lievense LA, Heuvers ME, Maat AP, Hendriks RW, Hoogsteden HC, Hegmans JP, Aerts JG. Immunotherapy. 2012;4(10):1011–1022. doi: 10.2217/imt.12.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calabrò L, Morra A, Fonsatti E, Cutaia O, Amato G, Giannarelli D, Di Giacomo AM, Danielli R, Altomonte M, Mutti L, Maio M. Tremelimumab for patients with chemotherapy-resistant advanced malignant mesothelioma: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1104–1111. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70381-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calabrò L, Ceresoli GL, di Pietro A, Cutaia O, Morra A, Ibrahim R, Maio M. CTLA4 blockade in mesothelioma: finally a competing strategy over cytotoxic/target therapy? Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2015;64(1):105–112. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1609-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calabrò L, Morra A, Fonsatti E, Cutaia O, Fazio C, Annesi D, Lenoci M, Amato G, Danielli R, Altomonte M, Giannarelli D, Di Giacomo AM, Maio M. Efficacy and safety of an intensified schedule of tremelimumab for chemotherapy-resistant malignant mesothelioma: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(4):301–309. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maio M, Scherpereel A, Calabrò L, Aerts J, Perez CS, Bearz A, Nackaerts K, Fennell DA, Kowalski D, Tsao AS, Taylor P, Grosso F, Atonia SJ, Nowak AK, Taboada M, Puglisi M, Stockman PK, Kindler HL. Tremelimumab as second-line or third-line treatment in relapsed malignant mesothelioma (DETERMINE): a multicenter, international, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(9):1261–1273. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30446-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bueno R, Stawiski EW, Goldstein LD, Durinck S, De Rienzo A, Modrusan Z, Gnad F, Nguyen TT, Jaiswal BS, Chirieac LR, Sciaranghella D, Dao N, Gustafson CE, Munir KJ, Hackney JA, Chaudhuri A, Gupta R, Guillory J, Toy K, Ha C, Chen YJ, Stinson J, Chaudhuri S, Zhang N, Wu TD, Sugarbaker DJ, de Sauvage FJ, Richards WG, Seshagiri S. Comprehensive genomic analysis of malignant pleural mesothelioma identifies recurrent mutations, gene fusions and splicing alterations. Nat Genet. 2016;48:407–416. doi: 10.1038/ng.3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balar AV, Weber JS. PD-1 and PD-L1 antibodies in cancer: current status and future directions. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66(5):551–564. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-1954-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boussiotis VA. Molecular and biochemical aspects of the PD-1 checkpoint pathway. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1767–1778. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1514296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Awad MM, Jones RE, Liu H, Lizotte PH, Ivanova EV, Kulkarni M, Herter-Sprie GS, Liao X, Santos AA, Bittinger MA, Keogh L, Koyama S, Almonte C, English JM, Barlow J, Richards WG, Barbie DA, Bass AJ, Rodig SJ, Hodi FS, Wucherpfennig KW, Jänne PA, Sholl LM, Hammerman PS, Wong KK, Bueno R. Cytotoxic T cells in PD-L1-positive malignant pleural mesotheliomas are counterbalanced by distinct immunosuppressive factors. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4:1038–1048. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cedrés S, Ponce-Aix S, Zugazagoitia J, Sansano I, Enguita A, Navarro-Mendivil A, Martinez-Marti A, Martinez P, Felip E. Analysis of expression of programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) in malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0121071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khanna S, Thomas A, Abate-Daga D, Zhang J, Morrow B, Steinberg SM, Orlandi A, Ferroni P, Schlom J, Guadagni F, Hassan R. Malignant mesothelioma effusions are infiltrated by CD3+ T cells highly expressing PD-L1 and the PD-L1+ tumor cells within these effusions are susceptible to ADCC by the anti-PD-L1 antibody avelumab. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:1993–2005. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mansfield AS, Roden AC, Peikert T, Sheinin YM, Harrington SM, Krco CJ, Dong H, Kwon ED. B7-H1 expression in malignant pleural mesothelioma is associated with sarcomatoid histology and poor prognosis. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:1036–1040. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alley EW, Lopez J, Santoro A, Morosky A, Saraf S, Piperdi B, van Brummelen E. Clinical safety and activity of pembrolizumab in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma (KEYNOTE-028): preliminary results from a non-randomised, open-label, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(5):623–630. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30169-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quispel-Janssen J, Zago J, Schouten R et al (2017) A phase II study of nivolumab in malignant pleural mesothelioma (NivoMes): with translational research (TR) biopsies. J Thorac Oncol 12,(suppl abstr 13.0, presented at the World Conference on Lung Cancer 2016)

- 25.Lievense LA, Sterman DH, Cornelissen R, Aerts JG. Checkpoint blockade in lung cancer and mesothelioma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(3):274–282. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201608-1755CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Das R, Verma R, Sznol M, Boddupalli CS, Gettinger SN, Kluger H, Callahan M, Wolchok JD, Halaban R, Dhodapkar MV, Dhodapkar KM. Combination therapy with anti-CTLA4 and anti-PD-1 leads to distinct immunologic changes in vivo. J Immunol. 2015;194(3):950–959. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larkin J, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Untreated Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(13):1270–1271. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1509660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calabrò L, Morra A, Giannarelli D, Amato G, Bertocci E, D’Incecco A, Danielli R, Brilli L, Giannini F, Altomonte M, Di Giacomo AM, Maio M (2017) Tremelimumab in combination with durvalumab in first or second-line mesothelioma patients: safety analysis from the phase II NIBIT-MESO-1 study. J Clin Oncol 35 (suppl; abstr 8558, presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2017)

- 29.Calabrò L, Morra A, Giannarelli D, Amato G, D’Incecco A, Danielli R, Alessia Covre A, Lewis MC, Altomonte M, Di Giacomo AM, Maio M. Tremelimumab in combination with durvalumab in first or second-line mesothelioma patients: the exploratory, non-randomised, phase 2, NIBIT-MESO-1 study. Lancet Resp Med. 2018 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scherpereel A, Mazieres J, Greillier L, Dô P, Bylicki O, Monnet I, Corre R, Audigier-Valette C, Locatelli-Sanchez M, Molinier O, Thiberville L, Urban T, Ligeza-poisson C, Planchard D, Amour E, Morin F, Moro-Sibilot D, Zalcman G (2017) Second- or third-line nivolumab (Nivo) versus nivo plus ipilimumab (Ipi) in malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) patients: Results of the IFCT-1501 MAPS2 randomized phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 35(suppl; abstr LBA8507, presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2017)

- 31.Miller AB, Hoogstraten B, Staquet M, Winkler A. Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer. 1981;47(1):207–214. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810101)47:1<207::AID-CNCR2820470134>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Byrne MJ, Nowak AK. Modified RECIST criteria for assessment of response in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(2):257–260. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frauenfelder T, Tutic M, Weder W, Gotti RP, Stahel RA, Seifert B, Opitz I. Volumetry: an alternative to assess therapy response for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(1):162–168. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00146110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolchok JD, Hoos A, O’Day S, Weber JS, Hamid O, Lebbé C, Maio M, Binder M, Bohnsack O, Nichol G, Humphrey R, Hodi FS. Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: immune-related response criteria. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(23):7412–7420. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoos A, Wolchok JD, Humphrey RW, Hodi FS. CCR 20th anniversary commentary: immune-related response criteria-capturing clinical activity in immuno-oncology. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(22):4989–4991. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seymour L, Bogaerts J, Perrone A, Ford R, Schwartz LH, Mandrekar S, Lin NU, Litière S, Dancey J, Chen A, Hodi FS, Therasse P, Hoekstra OS, Shankar LK, Wolchok JD, Ballinger M, Caramella C, de Vries EG. iRECIST: guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(3):e143–e152. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30074-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noij DP, Boerhout EJ, Pieters-van den Bos IC, Comans EF, Oprea-Lager D, Reinhard R, Hoekstra OS, de Bree R, de Graaf P, Castelijns JA. Whole-body-MR imaging including DWIBS in the work-up of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a feasibility study. Eur J Radiol. 2014;83(7):1144–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higashikawa K, Yagi K, Watanabe K, Kamino S, Ueda M, Hiromura M, Enomoto S. 64Cu-DOTA-anti-CTLA-4 mAb enabled PET visualization of CTLA-4 on the T-cell infiltrating tumor tissues. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e109866. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hettich M, Braun F, Bartholomä MD, Schirmbeck R, Niedermann G. High-resolution PET imaging with therapeutic antibody-based PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint tracers. Theranostics. 2016;6(10):1629–1640. doi: 10.7150/thno.15253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larimer BM, Wehrenberg-Klee E, Caraballo A, Mahmood U. Quantitative CD3 PET imaging predicts tumor growth response to anti-CTLA-4 therapy. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(10):1607–1611. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.173930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bauckneht M, Piva R, Sambuceti G, Grossi F, Morbelli S. Evaluation of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors: is there a role for positron emission tomography? World J Radiol. 2017;9(2):27–33. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v9.i2.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buchbinder EI, Desai A. CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways: similarities, differences, and implications of their inhibition. Am J Clin Oncol. 2016;39:98–106. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]