Abstract

The transformation and progression of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) to secondary acute myeloid leukemia (sAML) involve genetic, epigenetic, and microenvironmental factors. Driver mutations have emerged as valuable markers for defining risk groups and as candidates for targeted treatment approaches in MDS. It is also evident that the risk of transformation to sAML is increased by evasion of adaptive immune surveillance. This study was designed to explore the immune microenvironment, immunogenic tumor-intrinsic mechanisms (HLA and PD-L1 expression), and tumor genetic features (somatic mutations and altered karyotypes) in MDS patients and to determine their influence on the progression of the disease. We detected major alterations of the immune microenvironment in MDS patients, with a reduced count of CD4+ T cells, a more frequent presence of markers related to T cell exhaustion, a more frequent presence of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and changes in the functional phenotype of NK cells. HLA Class I (HLA-I) expression was normally expressed in CD34+ blasts and during myeloid differentiation. Only two out of thirty-six patients with homozygosity for HLA-C groups acquired complete copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity in the HLA region. PD-L1 expression on the leukemic clone was also increased in MDS patients. Finally, no interplay was observed between the anti-tumor immune microenvironment and mutational genomic features. In summary, extrinsic and intrinsic immunological factors might severely impair immune surveillance and contribute to clonal immune escape. Genomic alterations appear to make an independent contribution to the clonal evolution and progression of MDS.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00262-019-02420-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), Immune microenvironment, High molecular risk (HMR) mutations, Loss of heterozygosity (LOH), Immune-evasion

Introduction

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a heterogeneous group of clonal stem-cell disorders characterized by ineffective hematopoiesis, abnormal cellular morphology, and a propensity for progression to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [1]. The annual incidence of MDS is 4–5 cases/100,000 inhabitants and its prevalence is 7/100,000 inhabitance [2]. Its clinical course is very heterogeneous, and the survival rate is, therefore, highly variable [2]. This has led to the development of several classification systems, most recently WHO-2016 [3], and various prognostic systems such as the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) [4] and its revision (IPSS-R) [5].

Factors determining the pathogenesis and progression of MDS have not been fully elucidated. Cytogenetic alterations are detected in only 50% of MDS patients at diagnosis [6], whereas next-generation sequencing (NGS) studies have identified at least one recurrent somatic mutation in 85–90% of these patients [7]. Specifically, mutations in high molecular risk (HMR) genes (TP53, ETV6, ASXL1, RUNX1, EZH2) have been associated with an unfavorable prognosis and are considered an independent risk factor of progression to AML, regardless of the results of current prognostic score systems [8, 9]. However, independently of the selective advantage conferred by mutations (increase in proliferative and anti-apoptotic capacities, etc.), there is considerable evidence that deregulation of the immune system in the tumor microenvironment favors immunosurveillance evasion by the tumor cell, allowing progression and/or expansion of the malignant clone [10, 11]. In this regard, increased apoptosis is the hallmark of low-risk MDS and is associated with autoimmune disease-like characteristics, including activation of cytotoxic T CD8+ lymphocytes (CTLs), reduced regulatory T cell (Treg) count, and increased type 17 T-helper (Th17) cell count [12–14]. By contrast, immunodeficiency and immune exhaustion indicate high-risk MDS, characterized by a microenvironment that may favor immune evasion by the malignant clone [15, 16].

The immunogenicity of many types of cancer is known to be impacted by alterations in the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway or in antigen presentation, due to the abnormal expression of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules [17–19]. Our group recently identified a loss of heterozygosity in the HLA region (LOH HLA) as a possible immunoevasion mechanism in advanced cases of MDS, which may explain its progression and leukemic transformation in patients with no risk factors, i.e., HMR mutations or complex karyotypes. However, besides mechanisms affecting the immunogenicity of the tumor cell, the progression to secondary AML (sAML) may also be explained by high-risk genetic alterations and/or the dysregulation of cellular immune responses [19], factors that have been separately analyzed in numerous studies [9, 15]. In the present investigation, we conduct simultaneous analyzes of the genetic and immunogenic characteristics of the malignant clone alongside analysis of the immune microenvironment to explore a possible interplay between them in MDS and sAML patients.

Materials and methods

Patient samples and controls

The study included 130 patients from hospitals in Andalusia (Southern Spain) and on the Spanish MDS Registry (RESMD) diagnosed with MDS between December 2016 and November 2018. The patients (87 males, 43 females; mean age of 72 years) were categorized according to the WHO-2016 classification [3] as (1) early-stage disease: 5 with single lineage dysplasia (MDS-SLD), 71 with multilineage dysplasia (MDS-MLD), 10 with MLD and ring sideroblasts (MDS-RS), 13 with isolated del(5q) MDS del(5q), and 1 unclassifiable (MDS-U); or (2) advanced-stage disease: 30 with excess blasts: 14 with excess blasts-1 (MDS EB-1) and 16 with excess blasts-2 (MDS EB-2). MDS patients were categorized according to the IPSS and IPSS-R score prognosis systems as IPSS: low risk (low risk (LR)/intermediate-1 risk (INT-1); high risk (intermediate-2 risk (INT-2)/high risk (HR)) and IPSS-R: low risk (very low risk (VLR)/low risk (LR); high risk (intermediate risk (INT)/high risk (HR)/very high risk (VHR). Cytogenetic data were available for 111 of the 130 patients. MDS patients were classified according to their cytogenetic risk as: favorable [very good (−Y, del(11q), good (normal, del(20q), del(5q) alone or with 1 other anomaly and del(12p)], poor [poor (complex with 3 abnormalities, der(3q) or chromosome 7 abnormalities), very poor (complex with ≥ 3 abnormalities)], or intermediate (all other single or double abnormalities not listed). In addition, 23 patients (12 males, 11 females; mean age of 72 years) were diagnosed with sAML. The characteristics of all patients in the study are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients included in the study

| MDS patients | |

| No | 130 |

| Mean age (years) | 72 (24–95) |

| Sex | 87 male/43 female |

| Classification of WHO 2016 | |

| MDS-SLD | 5 (3.8%) |

| MDS-MLD | 71 (54.6%) |

| MDS-RS | 10 (7.7%) |

| MDS del(5q) | 13 (10%) |

| SMD-U | 1 (0.8%) |

| MDS EB-1 | 14 (10.8%) |

| MDS EB-2 | 16 (12.3%) |

| IPSS group | |

| Low risk | 92 (78.6%) |

| Low | 65 |

| Intermediate-1 | 27 |

| High risk | 25 (21.4%) |

| Intermediate-2 | 22 |

| High | 3 |

| IPSS-R group | |

| Low risk | 68 (57.6%) |

| Very low | 20 |

| Low | 48 |

| High risk | 50 (42.4%) |

| Intermediate | 31 |

| High | 7 |

| Very high | 12 |

| Cytogenetic risk | |

| Poor | 10 (9%) |

| Intermediate | 30 (27%) |

| Favorable | 71 (64%) |

| sAML patients | |

| No | 23 |

| Mean age (years) | 71 (56–85) |

| Sex | 12 male/11 female |

Cytogenetic risk: favorable [very good (−Y, del(11q), good (normal, del(20q), del(5q) alone or with 1 other anomaly and del(12p)], poor [poor (complex with 3 abnormalities, der(3q) or chromosome 7 abnormalities), very poor (complex with ≥ 3 abnormalities)], or Intermediate (all other single or double abnormalities not listed)

MDS-SLD myelodysplastic syndrome with single-lineage dysplasia, MDS-MLD MDS with multilineage dysplasia, MDS-RS MLD and ring sideroblasts, MDS del(5q) MDS with isolated del(5q), MDS-U MDS unclassifiable, MDS EB-1, -2 myelodysplastic syndrome with excess blasts-1, -2, sAML acute myeloid leukemia secondary to MDS, IPSS prognostic scoring system, IPSS-R revised international prognostic scoring system, VHR very high risk, HR high risk, INT intermediate, LR low risk, VL very low risk

The tumor microenvironment in MDS patients was separately studied in bone marrow (BM) (n = 61) and peripheral blood (PB) (n = 69) samples, while PB samples from 40 healthy donors (median age 70 years; range 50–91 years) served as controls.

Multiparameter flow cytometry analysis

Flow cytometry studies and characterization of the functional subset of T-cells and NK cells on BM and PB samples used fluorescent-labeled monoclonal antibodies (moAbs) described elsewhere [20]. A human regulatory T cell cocktail was used to identify Tregs defined as CD4+ CD127low CD25bright. The amount of Tregs was expressed as a percentage of total CD4 cells. NK cells were expressed as a percentage of the total T lymphocyte pool. NK cell subpopulations were determined by the selection of CD45+, CD3−, CD20− cells in the lymphocyte gate. The following subpopulations were detected in the plot, based on CD56 and CD16 markers: CD56bright (CD16dim/−), CD56dimCD16−, double-positive CD56dimCD16bright mature NK cells, and low cytolytic CD56−CD16bright NK cells. NK receptors were expressed as a percentage of CD56+ NK cells. The following moAbs against NK cell receptors were also used: CD158a (KIR2DL1)-FITC, anti-CD158b (KIR2DL3)-APC from RɣD Systems (Abingdon, UK); and anti-CD158b1/b2/j-PercP-Cy5.5, anti-CD158a/h-PE from Beckman Coulter (CA, USA).

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) were expressed as a percentage of total PB cellularity. For polymorphonuclear (PMN-MDSC) cells, Lin−/HLA DRlow/− cells were gated after the exclusion of eosinophils (FSC/SSC). In this gate, double-positive CD11b+CD33+ cells were selected, and the fraction of these cells expressing CD15 was then determined. For monocytic (Mo-MDSC) cells, monocyte populations were first gated in the SSC/CD14 plot, followed by the selection of HLA-DRlow/− cells in this gate [21].

PD-L1 expression was evaluated on blast cells, which were identified using the CD34+/SSClow gate. Next, the fraction of these cells expressing PD-L1 was determined.

Automated CD34+ cell isolation

CD34+ cells of patients were isolated from fresh BM or PB samples using an automatic immunomagnetic cell processing system (autoMACS Pro, Miltenyi Biotec), and the genomic DNA obtained was stored at − 40 °C for genetic studies.

Molecular and cytogenetic analysis

The NGS techniques, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array studies, and cytogenetic analysis used were previously reported [19].

NGS analysis of genes related to myeloid neoplasms detected mutations in MDS predictive genes (TP53, ASXL1, ETV6, EZH2, RUNX1), which were previously described as high molecular risk (HMR) mutations [9].

Statistical analysis

Variables with normal distribution (as checked by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test) were expressed as means ± standard deviation and non-normally distributed variables as medians (range). The parametric Student’s t test was used to compare between groups when the distribution was normal and the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test when it was not. Spearman analysis was used to evaluate correlations between quantitative variables. IBM-SPSS Statistics Ver.21.0. was used for all statistical analyses, and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Changes in leukocyte populations in PB from MDS patients

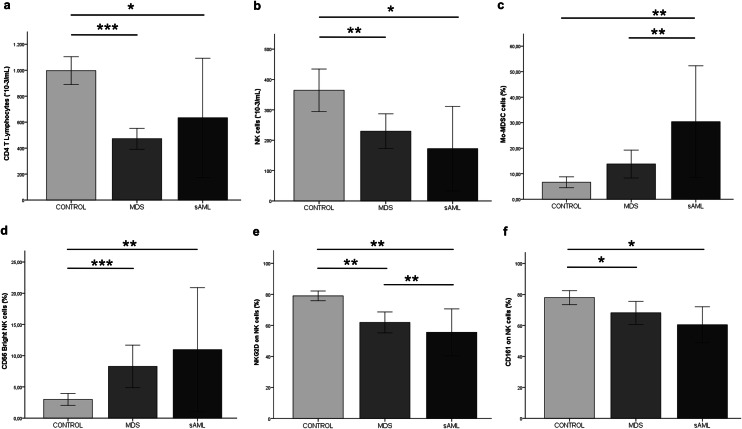

A significantly lower absolute T lymphocyte count (P = 0.0001) and CD4:CD8 ratio were observed in MDS patients than in healthy controls. The reduced CD4:CD8 ratio was attributable to changes in the CD4+ lymphocyte pool. The absolute CD4+ T cell count was markedly lower in MDS patients than in controls (P = 0.0001) (Fig. 1a), while the CD8+ T cell count was slightly lower than in controls (P = 0.007) (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Graphs representing different cell populations in the microenvironment in different groups of disease progression and healthy controls. The absolute number (cells*10−3/mL) of a CD4 T cells, b NK cells, in control, MDS and sAML groups. Percentages of c Mo-MDSCs cells, d NK CD56bright cells in control, MDS, and sAML groups. The percentage of e NKG2D and f CD161 receptors on NK cells of patients with MDS, sAML and healthy controls. Results are expressed as means ± SD. When significant, statistical results are indicated with the corresponding P value: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

Table 2.

Absolute count and percentages (mean ± SEM) of the different cells populations and immunogenic intrinsic characteristics (PD-L1 and HLA-I) in peripheral blood samples of healthy controls and MDS and sAML patients

| Control | MDS | P1 | sAML | P2* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphocyte pool (× 10−3/mL) | 1658.2 ± 690.7 | 1301.8 ± 593.4 | 0.028 | 1590.0 ± 804.5 | 0.641 |

| T cells (× 10−3/mL) | 1446.6 ± 608.4 | 894.4 ± 482.2 | 0.0001 | 1185.1 ± 775.3 | 0.569 |

| T-CD4+ | 996.5 ± 320.6 | 471.9 ± 277.3 | 0.0001 | 633.2 ± 496.2 | 0.026 |

| T-CD8+ | 530.8 ± 296.2 | 365.6 ± 242.0 | 0.007 | 408.3 ± 203.8 | 0.400 |

| B cells (× 10−3/mL) | 174.6 ± 144.4 | 106.0 ± 143.4 | 0.0001* | 107.5 ± 103.9 | 0.110 |

| NK cells (× 10−3/mL) | 364.3 ± 271.2 | 229.5 ± 195.5 | 0.004 | 172.2 ± 150.5 | 0.037 |

| T lymphocytes (%) | |||||

| CD3 | 73.9 ± 9.5 | 68.7 ± 14.8 | 0.093 | 72.1 ± 19.6 | 0.569 |

| CD4 | 43.0 ± 9.2 | 35.7 ± 11.4 | 0.001 | 36.7 ± 13.1 | 0.251 |

| CD8 | 23.1 ± 8.1 | 28.4 ± 11.2 | 0.007 | 31.1 ± 14.3 | 0.083 |

| CD4 T lymphocytes (%) | |||||

| Th1 | 24.2 ± 6.2 | 22.4 ± 10.0 | 0.447 | 19.9 ± 7.8 | 0.345 |

| Th17 | 11.9 ± 5.2 | 14.1 ± 9.5 | 0.299 | 10.2 ± 3.3 | 0.395 |

| Th22 | 3.6 ± 2.2 | 7.0 ± 5.2 | 0.004 | 5.5 ± 3.5 | 0.143 |

| Treg | 6.3 ± 1.7 | 7.1 ± 3.1 | 0.190 | 8.8 ± 4.2 | 0.058 |

| CD4+ CD39+ | 3.3 ± 2.2 | 5.3 ± 4.0 | 0.273 | 7.5 ± 4.1 | 0.010 |

| CD8 T lymphocytes | |||||

| CD8+ CD39+(%) | 1.3 ± 1.2 | 4.8 ± 8.5 | 0.006 | 3.3 ± 2.9 | 0.022 |

| Ratio T cells | |||||

| CD4/CD8 | 2.2 ± 1.2 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 0.001 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 0.025 |

| CD8/Treg | 4.3 ± 1.9 | 4.7 ± 3.5 | 0.747 | 6.4 ± 7.1 | 0.698 |

| Th1/Th17 | 2.5 ± 1.6 | 2.6 ± 2.0 | 0.334 | 2.3 ± 1.6 | 0.620 |

| Th1/Treg | 4.2 ± 1.3 | 4.3 ± 3.2 | 0.884 | 4.7 ± 6.5 | 0.124 |

| NK cells (%) | |||||

| CD56Bright | 3.0 ± 3.0 | 8.3 ± 10.0 | 0.0001* | 10.9 ± 10.7 | 0.006 |

| CD56+CD16+ | 80.9 ± 9.1 | 73.3 ± 18.5 | 0.023 | 70.9 ± 17.3 | 0.111 |

| CD56+CD16− | 3.4 ± 2.0 | 8.7 ± 13.6 | 0.043* | 5.6 ± 7.0 | 0.781 |

| CD56−CD16+ | 12.3 ± 7.7 | 8.7 ± 7.5 | 0.035 | 12.4 ± 7.7 | 0.489 |

| CD56+ NK cells (%) | |||||

| NKG2D | 79.02 ± 9.9 | 61.9 ± 21.0 | 0.002 | 55.5 ± 16.3 | 0.001 |

| NKp46 | 80.7 ± 13.6 | 71.02 ± 19.9 | 0.013 | 75.8 ± 19.8 | 0.520 |

| CD161 | 77.9 ± 14.2 | 68.2 ± 23.1 | 0.025 | 60.4 ± 12.5 | 0.010 |

| MDSCs (%) | |||||

| PMN-MDSCs | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.1 | 0.001 | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 0.0001 |

| Mo-MDSCs | 6.6 ± 6.5 | 14.2 ± 21.8 | 0.483* | 30.4 ± 32.6 | 0.003 |

| CD34+ cells (%) | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 1.6 ± 3.6 | 0.009 | 27.4 ± 11.7 | 0.0001 |

| PD-L1 (%) | ND | 30.5 ± 26.2 | NA | 3.1 ± 3.9 | NA |

| HLA-I (MFI) | 35765 ± 18576 | 14837 ± 9356 | 0.002 | 16933 ± 19929 | 0.025 |

P values indicated in bold are statistically significant

P1 value: stadistic comparison between MDS and the control goup. P2 value: stadistic comparison between sAML and the control group. Student’s t test are displayed

MDS myelodysplastic syndrome, sAML acute myeloid leukemia secondary to MDS, PMN-MDSCs polymorphonuclear-myeloid derived suppressor cells, Mo-MDSCs monocytic-myeloid derived suppressor cells, HLA-I HLA class I, MFI mean fluorescence intensity, ND not done, NA not applicable

*Statistical analysis was evaluated by Mann–Whitney U test

Significantly lower absolute B lymphocyte (P = 0.045) and absolute NK (P =0.004) counts were also recorded in MDS patients than in controls (Fig. 1b; Table 2).

PB leukocyte subpopulations evolve to an immunosuppressive microenvironment from low to high-risk MDS

Immunophenotypic characterization of the functional populations of T cells, NK cells, and other cell populations of the innate immune system (e.g., MDSCs) was carried out in PB from 69 MDS and 11 sAML patients.

Treg, Th1, and Th17 cell frequencies were similar between MDS patients and controls, as were Th1/Th17, Treg/Th17, and CD8/Treg ratios (P > 0.05). However, we found a higher frequency of Th22 cells (subset of Th17 cells) in MDS patients than in controls (P = 0.004) and a higher frequency of CD4+CD39+ T cells in sAML patients (P = 0.01) and of CD8+ CD39+ T cells in both sAML (P = 0.022) and MDS patients (P = 0.006) than in controls (Table 2).

We found major phenotypic changes in the PB immune microenvironment of NK cells, with a significantly higher frequency of NK CD56bright cells in MDS patients (P = 0.0001) and sAML patients (P = 0.006) than in controls (Fig. 1d). MDS patients also showed a higher frequency of NK cells with CD56+ CD16− phenotype (P = 0.043) and a lower frequency of mature cytotoxic effector NK cells (CD56dimCD16bright) (P = 0.023) and CD56−CD16+ NK cells (P = 0.035) in MDS patients than in controls (Table 2).

A marked reduction was observed in NK activating receptors on CD56+ expressing NK cells (CD56bright and CD56dim) such as NKG2D, NKp46, and CD161. The expression in PB of all these activating receptors was lower in MDS patients than in controls (NKG2D, P = 0.002; NKp46, P = 0.013; CD161, P = 0.025). In addition, the expression of NKG2D (P = 0.001) and CD161 (P = 0.01) receptors was lower in sAML patients than in healthy controls (Fig. 1e, f; Table 2). NKG2D expression was significantly lower in MDS patients with excess of blasts I/II, who were at higher risk to progression to sAML than in MDS patients with a lower risk profile (no excess of blasts) (P = 0.007). Additionally, NKG2D expression was higher in the low-risk versus high-risk groups as classified by IPSS score (high risk vs. low risk, P = 0.009). Finally, the percentage of NKG2D receptors was higher in the favorable cytogenetic group than in those with poor karyotypes (P = 0.025).

Analysis of the expression of killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs), both those with activating (KIR2DS1, KIR2DS2) and inhibitory (KIR2DL1, KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL3) activity on CD56+ NK cells, showed no significant differences between MDS and sAML patients or between these two patient groups and controls (P > 0.05).

Finally, immunophenotypic study of the suppressive myeloid subset of polymorphonuclear and monocytic lineage in PB revealed a higher PMN-MDSCs frequency in MDS (P = 0.001) and sAML patients than in healthy controls (P = 0.0001) and a higher Mo-MDSCs frequency in sAML patients (P = 0.003) but not in MDS patients (P > 0.05) with respect to controls (Fig. 1c; Table 2).

Significantly higher PMN-MDSCs (P = 0.011) and Mo-MDSCs (P = 0.002) frequencies were observed in patients with excess blasts according to the WHO classification than in those without. A positive correlation was observed between the percentage of Mo-MDSCs and percentage of blasts in the PB of MDS patients (Spearman R = 0.564, P = 0.00001). The frequency of MDSCs also differed according to IPSS/IPSS-R and cytogenetic risk categories. Higher percentages of PMN-MDSCs (P = 0.015) and Mo-MDSCs (P = 0.004) were found in high-risk versus low-risk groups as classified by IPSS-R, and higher percentages of Mo-MDSCs were observed in the intermediate versus favorable cytogenetic risk group (P = 0.05). Similar results to those obtained with IPSS-R were obtained in the comparison of IPSS groups (data not shown).

Changes in the BM immune microenvironment reproduce those in the PB of MDS patients

The study of changes in lymphocyte subpopulations in MDS patients (BM = 61, PB = 69) and sAML patients (BM = 12, PB = 11) also included the simultaneous analysis of six paired BM and PB samples from MDS patients.

The microenvironment of both PB and BM largely comprised CD3+ T cells, with a higher frequency of CD8+ T lymphocytes and an inversion of the CD4:CD8 ratio. The same results were obtained in the study of the BM and PB microenvironment in the paired samples group.

Likewise, analysis of the functional composition of T lymphocyte subpopulations (Th1, Th17, Th22, Treg) and their ratio (Th1/Treg, Th1/Th17 and CD8/Treg) showed no significant differences between BM and PB samples (P > 0.05).

Finally, we observed an increase in the frequency of markers associated with suppression and/or exhausted T cells (CD39) in the immune microenvironment of BM than in that of PB (CD4+CD39+, P = 0.004; CD8+CD39, P = 0.00002). We also found differences in relation to the NK component, observing a higher frequency of the non-cytotoxic phenotype (CD56Bright) (P = 0.036) and a higher frequency of the activating receptor NKG2D in BM than in PB (P = 0.004).

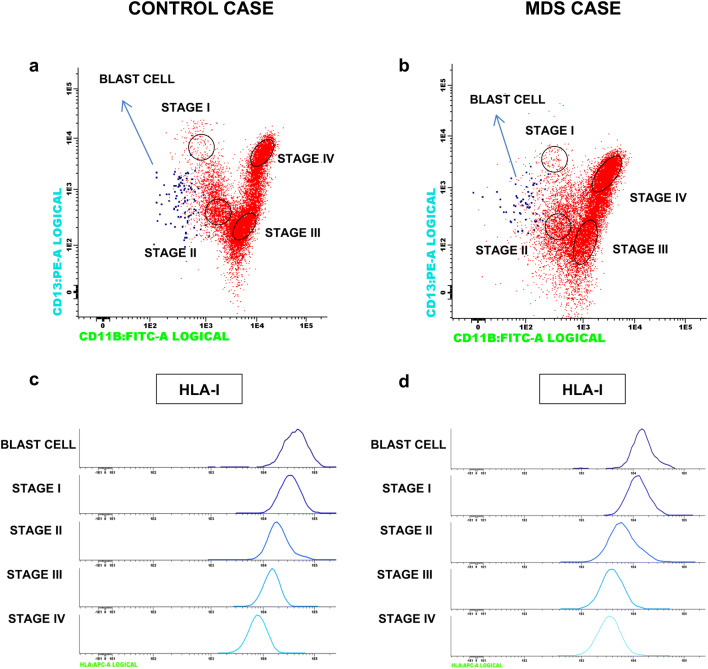

HLA and PD-L1 expression in MDS patients

Loss of tumor HLA and positive PD-L1 expression are natural adaptive immune evasion mechanisms that may contribute to resistance to anti-tumor immunity [18, 22, 23]. We analyzed HLA Class I (HLA-I) expression on CD34+ blasts and during myeloid-cell maturation in 45 BM samples from MDS (n = 32) and sAML (n = 13) patients, finding no asynchronous or aberrant expression. In fact, the gradual downregulation of these molecules during myeloid maturation was identical to that observed in control samples (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Histograms with examples of HLA expression on CD34 cells and during the myelopoiesis process in healthy control (left column) and MDS patient (right column). Blast cells (blue dots) and granulocytes are gated based on CD11b and CD13 markers, and their immunophenotype is shown in a multiparameter histogram plot in a healthy control and b MDS patient. We have established four stages of granulocyte differentiation: stage I, II, III and IV, based on the gradual increase in CD11b and dynamic CD13 expression and corresponding to a predominance of promyelocytic (CD13brigt CD11b−), myelocytic (CD13+/− CD11b−), metamyelocytic (CD13+/− CD11b+/−), and mature neutrophils (CD13brigt CD11bbrigt), respectively. Histograms representing HLA expression patterns during myeloid differentiation in healthy control (c) and MDS patient (d)

No patient in the study showed total loss of HLA-I expression on CD34+ cells. However, the mean HLA-I expression on dysplastic CD34+ cells was significantly lower in MDS and AMLs patents than in controls (SMD vs. Control, P = 0.003; sAML vs. Control, P = 0.025). No significant differences in HLA-I expression on CD34+ were found between MDS and sAML patients (P > 0.05) (Table 2). We also investigate the possibility of the disruption of antigen presentation through LOH HLA at 6p21 locus. We detected acquired copy neutral-loss of heterozygosity (CN-LOH) at 6p21 HLA locus in only 2 out of 36 cases analyzed (data not shown). In another three patients, we observed LOH outside the 6p21 locus in a proportion of tumor cells (SNP distribution was shifted away from the heterozygous line in the BAF plot) (Supplementary Figure 1). Interestingly, both cases with LOH at chromosome 6 were homozygous for the HLA-C group (HLA-C1 or HLA-C2) (Supplementary Table 1). There were no cases of copy number alteration in chromosome 6 in heterozygous HLA-C1/C2 patients.

PD-L1 expression on CD34+ cells was higher in MDS patients than in sAML patients (P = 0.0001) (Table 2) but did not significantly differ between early and advanced stages of MDS (P > 0.05).

Relationship between tumor microenvironment and somatic mutations in MDS patients

The mutational study was performed in 50 MDS patients with flow cytometry results available on their tumor composition microenvironment. The classification obtained was early-stage disease in 33 patients [MDS-SLD in 1, MDS-MLD in 22, MDS del(5q) in 8, and MDS-RS in 2] and advanced-stage disease in 17 patients (MDS EB-1 in 11, and MDS EB-2 in 6).

Somatic mutations in the studied genes were observed in 40 out of the 50 patients studied (80%), with no mutations detected in the remaining 10 patients (20%) (Supplementary Table 2).

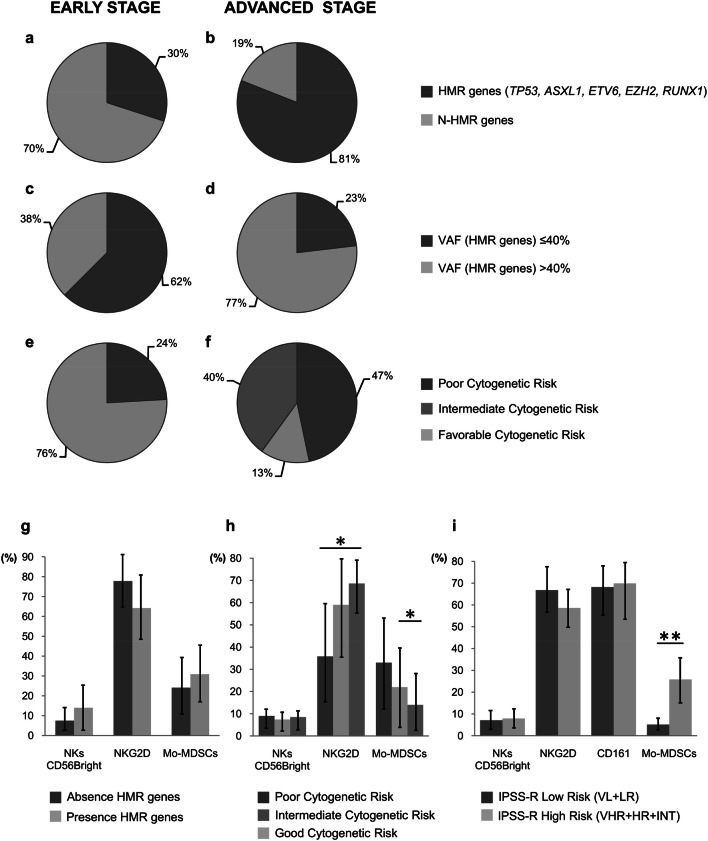

Somatic mutations in these genes were observed in 23 out of 29 patients (79.3%) in the early-stage MDS group. Mutations in non-high molecular risk (N-HMR) genes, mainly those involved in DNA methylation (TET2, DNMT3A, IDH1/2) and RNA splicing (SF3B1, ZRSR2, U2AF1, SRSF2), were observed in 16 out of 23 patients in this group (69.6%). In contrast, a N-HMR mutational profile was found in only 3 out of 16 patients in the advanced-stage group (18.7%).

Somatic mutations in these genes were observed in 16 out of 20 patients (80%) in the advanced-stage group. A much higher proportion of patients had somatic mutations in HMR genes (TP53, ETV6, ASXL1, RUNX1, EZH2) in this group (13/16, 81%) than in the early stage-MDS group (7/23, 30.4%) (Fig. 3a, b). Mutations in TP53 were especially frequent among patients in the advanced-stage group with HMR gene mutations (9/13 patients), and 8 of these 9 patients showed no other alterations in the genes under study.

Fig. 3.

Distribution of 50 MDS patients previously classified according to the progression of the disease (early vs. advanced stages) as a function of mutational profile characteristics. a, b Presence/absence of high molecular risk (HMR) mutations; c, d < 40%/≥ 40% of the variant allele frequency (VAF) in HMR genes. e, f Karyotype risk (poor, intermediate, good). g–i Graphs representing different cell populations in the microenvironment as a function of mutational profile characteristics. g Presence/absence of HMR mutations, h poor, intermediate, or good karyotype risk; i IPSS-R score (high risk vs. low risk). No significant differences were observed in any of the statistical analyses performed

In addition, the allele frequency of HMR gene mutations differed between the early-stage and advanced-stage MDS patients, observing that VAFs in HMR genes were > 40% in the advanced-stage group (10/13 patients) and < 40% in 5 out of 8 patients in the early stage-MDS group (Fig. 3c, d). We also found an increase in poor karyotypes in the advanced-stage group, whereas none were observed in the early-stage group (Fig. 3e, f).

The composition of the tumor microenvironment was evaluated according to the total number of mutations (≤ 2 or > 3 mutations), allele frequency (VAF ≤ 30% or > 30%), and the absence/presence of mutations in HMR genes.

We compared cellular populations between MDS patients divided as follows: 38 MDS patients with ≤ 2 total mutations and 12 patients with > 3 total mutations; 18 MDS patients with VAFs ≤ 30% and 22 patients with VAFs > 30%. Our results did not reveal any significant differences in the composition of immune populations in the tumor microenvironment based on the mutational allele burden (P > 0.05).

We analyzed the possible relationship between the presence of HMR mutations affecting TP53, RUNX1, ASXL1, EZH2, and ETV6 genes and the cellular tumor microenvironment in both BM and PB samples. For this purpose, MDS patients were divided into two groups: high risk (presence of at least one mutation in any of HMR genes) (n = 32) and low risk (absence of mutations in HMR genes) (n = 18). A higher percentage of blast cells were observed in BM samples from the high-risk versus low-risk groups (7% vs. 2.9%, P = 0.029). No significant differences between these groups were found in other components of the microenvironment (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3g).

Discussion

MDS are characterized by major genetic heterogeneity in somatic mutations, chromosomal alterations, and epigenetic changes, which can participate as drivers of the development and progression of this disease [8, 9]. On the other hand, the role of the immune response is complex and can even be ambiguous or contradictory, as demonstrated by the proposal of both immunosuppressive and immunostimulatory approaches in these cases [24]. In this study, we simultaneously analyzed the immune microenvironment, immunogenic characteristics, and genetic profile of the malignant blast in MDS patients.

In general, we observed a dysregulation of the immune response, which was maintained until advanced stages of the disease, creating an immune environment that enhances and promotes immunoevasion and transformation to AML. In MDS, the CD4 cell count was markedly reduced, CD8-T cells showed markers related to T-cell exhaustion, NK cells exhibited altered functional phenotypes associated with reduced cytotoxic capacity, and the immune microenvironment was enriched in MDSCs.

Our analysis of Th subpopulations found no significant differences between their proportions in MDS patients and in healthy controls with the exception of Th22 cells, inflammatory CD4+ T cells that secrete IL-22 but do not express IL-17 or interferon-gamma (IFN-γ). The percentage of Th22 cells in PB was higher in the patients, as observed in other hematological malignancies such as AML or ALL [25, 26]. We also highlight the greater presence of T cells, mainly CD8, that express the CD39 marker, associated with T-cell exhaustion. CD39-expressing T cells may contribute to an inhibitory immune microenvironment in sAML patients by inhibiting the activation of T cells, as observed in solid tumors and chronic lymphocytic leukemia [27, 28].

The main study findings are related to NK cells and MDSCs. We observed a major reduction in the expression of NK activating receptors and an increase in NK cells with a non-cytotoxic phenotype (CD56bright), which play an immunomodulatory role [29] during both early and advanced stages of the disease and appear to be a characteristic of other hematological malignancies [30]. These changes have also been observed in melanomas, in which NK cells displayed a marked downregulation of NKp30, NKp44 and NKG2D activating receptors, with an important reduction in cytolytic granule content and NK cytotoxicity [31]. By contrast, no major changes were observed in the family of activating or inhibitory killer-cell immunoglobulin receptors. MDSC analysis revealed an increase in MDS patients with a high risk of progression. These results are consistent with previous reports associating MDSCs with advanced stages and a poor prognosis [21, 32].

Analysis of the mutational profile of MDS patients found somatic mutations in the genes of interest in 80% of the patients [8, 9]. Specifically, mutations in HMR genes were more frequently observed in patients in more advanced stages of the disease (in 81.3% of patients in pre-leukemic-MDS group vs 30.4% of those in early-stage MDS group). However, neither the number of mutations, their category (low or high molecular risk) nor the allelic frequencies were associated with relevant changes in the composition of the immune microenvironment, indicating that somatic mutations per se may have independent prognostic value [9].

With regard to the immunogenic characteristics of the tumor cell blast, we analyzed PDL-1 and HLA cell surface expression. PD-L1 is expressed by solid tumors and hematological neoplasms [17, 18] and appears to play an active role in immunosurveillance evasion in MDS. Our results confirm the higher PD-L1 expression on CD34+ stem cells in MDS patients than in sAML patients [33].

Finally, we explored the possible role of HLA cell surface alterations in immunoediting and evasion in MDS patients. Most investigations of HLA expression have been performed in solid tumors [34–36], finding a higher frequency of HLA loss in comparison to hematological neoplasms [37, 38]. No case in the present series showed total loss of HLA expression. Our results indicate that mutations in β2-microglobuline gene (β2m) or in other components of the antigenic presentation machinery that produce the absence of cell surface HLA expression are not positively selected by the malignant clone of MDS. Few studies have reported HLA alterations in acute leukemias and only mutations that affect alleles have been described [39]. Paradoxically, however, data have been published supporting the relevance of β2m mutations in the pathogenesis of DLBCL and other lymphomas [40]. It is likely that HLA-negative cells are present in lymphomas, as in some solid tumors [35, 41]. We speculate that the total absence of HLA antigen expression and the presence of β2m gene mutations are not permissive in myeloblastic or lymphoblastic leukemia because of the direct contact and control of NK cells. We also detected loss of heterozygosity involving the whole HLA region. This genomic loss of HLA alleles affects the clinical outcome in low-risk myelodysplastic syndrome patients, allowing subclonal expansions to evade cytotoxic-T and NK cell attack [19]. However, the present findings demonstrate that this gene alteration is infrequent (2/36 cases) in MDS in comparison to other neoplasms [34, 35]. There are also likely to be restrictions in some hematological malignancies against the generation of LOH HLA, which probably occur preferentially in homozygous HLA-C patients [19, 42]. In fact, LOH HLA was not observed in the present HLA-C1/C2 individuals, probably because blast cells with haplotype loss would be targeted by NK cells (Supplemental Table 1). Furthermore, the mechanism of LOH HLA must be a CN-LOH [19, 42]; if not, LOH at 6p21 would lead to lesser inhibition and greater NK recognition and clearance of the tumor cell. This would explain the finding of LOH in chromosome 6 but outside the HLA region in three cases (Supplemental Figure 1). Finally, LOH HLA appears to be more frequent in lymphomas than in other hematological malignancies [43, 44], and the explanation would be the same as for β2 m gene mutations: the exclusion and homing difficulties of NK cells, preventing their direct contact with the tumor cell [34, 41, 45].

Conclusions

MDS progression appears to be associated with changes in the immune microenvironment that inhibit effective anti-tumor responses. Immunoevasion can be produced by the functional impairment of T and NK cells and by the presence of myeloid suppressor cells rather than by an immunoediting effect on antigenic recognition of the blast cells, which is limited to very specific cases. Finally, somatic mutations represent driving events that can themselves independently provide selective survival and proliferative advantages in the tumor microenvironment of MDS patients.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Victoria Calvo and María Corzo for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- HLA-I

HLA Class I

- HMR

High molecular risk

- IPSS

International prognostic scoring system

- IPSS-R

International prognostic scoring system revised

- LOH HLA

Loss of heterozygosity in the HLA region

- LOH

Loss of heterozygosity

- MDS del(5q)

MDS with isolated del(5q)

- MDS EB

MDS with excess blasts

- MDS

Myelodysplastic syndromes

- MDSCs

Myeloid derived suppressor cells

- MDS-MLD

MDS with multilineage dysplasia

- MDS-RS

MLD and ring sideroblasts

- MDS-SLD

MDS with single lineage dysplasia

- MoAbs

Monoclonal antibodies

- NGS

Next-generation sequencing

- PB

Peripheral blood

- sAML

Secondary acute myeloid leukemia

Author contributions

PM and LNC contributed to the immunophenotypic analysis of the tumor microenvironment. PM and MB contributed to sequencing and data analysis. FH and PG contributed to the diagnosis and classification of patients based on their clinical and hematological characteristics. ARG-R carried out the statistical analyses. PM, MB, PJ, MJ, FG, and FR-C were involved with all aspects of the study’s design and contributed to the manuscript preparation.

Funding

This work was supported by Grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III co-financed by FEDER funds (European Union) (PI 16/00752, PI 17/00197) and Junta de Andalucía in Spain (Group CTS-143, PI09/0382). This study is part of the doctoral thesis of Paola Montes, whose pre-doctoral fellowship was partially financed by Abbott, Becton–Dickinson, Beckman Coulter, and the Spanish MDS group.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval and ethical standards

The procedures with human samples were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the ethical standards of the Research Ethics Committee of Virgen de las Nieves Hospital in Granada, Spain, which approved the project on June 28 2016 (PEIBA code 0713-N-16 and PROYECTO code 555).

Informed consent

Written informed consent was provided by all patients at the time of their diagnosis and by healthy donors at routine analyses during the first few months of the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Germing U, Kobbe G, Haas R, Gattermann N. Myelodysplastic syndromes: diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110:783–790. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neukirchen J, Schoonen WM, Strupp C, Gattermann N, Aul C, Haas R, Germing U. Incidence and prevalence of myelodysplastic syndromes: data from the Düsseldorf MDS-registry. Leuk Res. 2011;35:1591–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett JM. Changes in the updated 2016: WHO Classification of the myelodysplastic syndromes and related myeloid neoplasms. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2016;16:607–609. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenberg P, Cox C, LeBeau MM, Fenaux P, Morel P, Sanz G, Sanz M, Vallespi T, Hamblin T, Oscier D, Ohyashiki K, Toyama K, Aul C, Mufti G, Bennett J. International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 1997;89:2079–2088. doi: 10.1182/blood.V89.6.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg PL, Tuechler H, Schanz J, Sanz G, Garcia-Manero G, Solé F, Bennett JM, Bowen D, Fenaux P, Dreyfus F, Kantarjian H, Kuendgen A, Levis A, Malcovati L, Cazzola M, Cermak J, Fonatsch C, Le Beau MM, Slovak ML, Krieger O, Luebbert M, Maciejewski J, Magalhaes SM, Miyazaki Y, Pfeilstöcker M, Sekeres M, Sperr WR, Stauder R, Tauro S, Valent P, Vallespi T, van de Loosdrecht AA, Germing U, Haase D. Revised international prognostic scoring system for myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2012;120:2454–2465. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-420489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wall M. Recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities in myelodysplastic syndromes. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1541:209–222. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6703-2_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pellagatti A, Boultwood J. The molecular pathogenesis of the myelodysplastic syndromes. Eur J Haematol. 2015;95:3–15. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Malcovati L, Tauro S, Gundem G, Van Loo P, Yoon CJ, Ellis P, Wedge DC, Pellagatti A, Shlien A, Groves MJ, Forbes SA, Raine K, Hinton J, Mudie LJ, McLaren S, Hardy C, Latimer C, Della Porta MG, O’Meara S, Ambaglio I, Galli A, Butler AP, Walldin G, Teague JW, Quek L, Sternberg A, Gambacorti-Passerini C, Cross NC, Green AR, Boultwood J, Vyas P, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, Bowen D, Cazzola M, Stratton MR, Campbell PJ. Clinical and biological implications of driver mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2013;122:3616–3627. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-08-518886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bejar R, Steensma DP. Recent developments in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2014;124:2793–2803. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-522136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C, Yang Y, Gao S, Chen J, Yu J, Zhang H, Li M, Zhan X, Li W. Immune dysregulation in myelodysplastic syndrome: clinical features, pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;122:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivy KS, Brent Ferrell P., Jr Disordered immune regulation and its therapeutic targeting in myelodysplastic syndromes. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2018;13:244–255. doi: 10.1007/s11899-018-0463-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolach O, Stone R. Autoimmunity and inflammation in myelodysplastic syndromes. Acta Haematol. 2016;136:108–117. doi: 10.1159/000446062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kook H, Zeng W, Guibin C, Kirby M, Young NS, Maciejewski JP. Increased cytotoxic T cells with effector phenotype in aplastic anemia and myelodysplasia. Exp Hematol. 2001;29:1270–1277. doi: 10.1016/S0301-472X(01)00736-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouchliou I, Miltiades P, Nakou E, Spanoudakis E, Goutzouvelidis A, Vakalopoulou S, Garypidou V, Kotoula V, Bourikas G, Tsatalas C, Kotsianidis I. Th17 and Foxp3(+) T regulatory cell dynamics and distribution in myelodysplastic syndromes. Clin Immunol. 2011;139:350–359. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aggarwal S, van de Loosdrecht AA, Alhan C, Ossenkoppele GJ, Westers TM, Bontkes HJ. Role of immune responses in the pathogenesis of low-risk MDS and high-risk MDS: implications for immunotherapy. Br J Haematol. 2011;153:568–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08683x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epling-Burnette PK, Bai F, Painter JS, Rollison DE, Salih HR, Krusch M, Zou J, Ku E, Zhong B, Boulware D, Moscinski L, Wei S, Djeu JY, List AF. Reduced natural killer (NK) function associated with high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and reduced expression of activating NK receptors. Blood. 2007;109:4816–4824. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-035519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu H, Boyle TA, Zhou C, Rimm DL, Hirsch FR. PD-L1 expression in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:964–975. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jelinek T, Mihalyova J, Kascak M, Duras J, Hajek R. PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in haematological malignancies: update 2017. Immunology. 2017;152:357–371. doi: 10.1111/imm.12788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montes P, Kerick M, Bernal M, Hernández F, Jiménez P, Garrido P, Márquez A, Jurado M, Martin J, Garrido F, Ruiz-Cabello F. Genomic loss of HLA alleles may affect the clinical outcome in low-risk myelodysplastic syndrome patients. Oncotarget. 2018;9:36929–36944. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Del Mar Valenzuela-Membrives M, Perea-García F, Sanchez-Palencia A, Ruiz-Cabello F, Gómez-Morales M, Miranda-León MT, Galindo-Angel I, Fárez-Vidal ME. Progressive changes in composition of lymphocytes in lung tissues from patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:71608–71619. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kittang AO, Kordasti S, Sand KE, Costantini B, Kramer AM, Perezabellan P, Seidl T, Rye KP, Hagen KM, Kulasekararaj A, Bruserud Ø, Mufti GJ. Expansion of myeloid derived suppressor cells correlates with number of T regulatory cells and disease progression in myelodysplastic syndrome. Oncoimmunology. 2015;5:e1062208. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1062208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garrido F, Ruiz-Cabello F, Cabrera T, Pérez-Villar JJ, López-Botet M, Duggan-Keen M, Stern PL. Implications for immunosurveillance of altered HLA Class I phenotypes in human tumours. Immunol Today. 1997;18:89–95. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(96)10075-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seliger B, Cabrera T, Garrido F, Ferrone S. HLA Class I antigen abnormalities and immune escape by malignant cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:3–13. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2001.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glenthøj A, Ørskov AD, Hansen JW, Hadrup SR, O’Connell C, Grønbæk K. Immune mechanisms in myelodysplastic syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 doi: 10.3390/ijms17060944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu S, Liu C, Zhang L, Shan B, Tian T, Hu Y, Shao L, Sun Y, Ji C, Ma D. Elevated Th22 cells correlated with Th17 cells in peripheral blood of patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:1927–1945. doi: 10.3390/ijms15021927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tian T, Sun Y, Li M, He N, Yuan C, Yu S, Wang M, Ji C, Ma D. Increased Th22 cells as well as Th17 cells in patients with adult T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;426:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canale FP, Ramello MC, Núñez N, Araujo Furlan CL, Bossio SN, Gorosito Serrán M, Tosello Boari J, Del Castillo A, Ledesma M, Sedlik C, Piaggio E, Gruppi A, Acosta Rodríguez EA, Montes CL. CD39 expression defines cell exhaustion in tumor-infiltrating CD8(+) T cells. Cancer Res. 2018;78:115–128. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-16-2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perry C, Hazan-Halevy I, Kay S, Cipok M, Grisaru D, Deutsch V, Polliack A, Naparstek E, Herishanu Y. Increased CD39 expression on CD4(+) T lymphocytes has clinical and prognostic significance in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:1271–1279. doi: 10.1007/s00277-012-1425-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cichocki F, Schlums H, Theorell J, Tesi B, Miller JS, Ljunggren HG, Bryceson YT. Diversification and functional specialization of human NK cell subsets. Curr Top Microbiol. 2016;395:63–93. doi: 10.1007/82_2015_487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costello RT, Fauriat C, Sivori S, Marcenaro E, Olive D. NK cells: innate immunity against hematological malignancies? Trends Immunol. 2004;25:328–333. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pietra G, Vitale M, Moretta L, Mingari MC. How melanoma cells inactivate NK cells. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:974–975. doi: 10.4161/onci.20405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu J, Zhou Y, Huang Q, Qiu L. CD14(+) HLA-DR (low/−) expression: a novel prognostic factor in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Oncol Lett. 2014;9:1167–1172. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang H, Bueso-Ramos C, DiNardo C, Estecio MR, Davanlou M, Geng QR, Fang Z, Nguyen M, Pierce S, Wei Y, Parmar S, Cortes J, Kantarjian H, Garcia-Manero G. Expression of PD-L1, PD-L2, PD-1 and CTLA4 in myelodysplastic syndromes is enhanced by treatment with hypomethylating agents. Leukemia. 2014;28:1280–1288. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perea F, Bernal M, Sánchez-Palencia A, Carretero J, Torres C, Bayarri C, Gómez-Morales M, Garrido F, Ruiz-Cabello F. The absence of HLA Class I expression in non-small cell lung cancer correlates with the tumor tissue structure and the pattern of T cell infiltration. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:888–899. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGranahan N, Rosenthal R, Hiley CT, Rowan AJ, Watkins TBK, Wilson GA, Birkbak NJ, Veeriah S, Van Loo P, Herrero J, Swanton C. Allele-specific HLA loss and immune escape in lung cancer evolution. Cell. 2017;171:1259–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carretero R, Romero JM, Ruiz-Cabello F, Maleno I, Rodriguez F, Camacho FM, Real LM, Garrido F, Cabrera T. Analysis of HLA Class I expression in progressing and regressing metastatic melanoma lesions after immunotherapy. Immunogenetics. 2008;60:439–447. doi: 10.1007/s00251-008-0303-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brouwer RE, van der Heiden P, Schreuder GM, Mulder A, Datema G, Anholts JD, Willemze R, Claas FH, Falkenburg JH. Loss or downregulation of HLA Class I expression at the allelic level in acute leukemia is infrequent but functionally relevant and can be restored by interferon. Hum Immunol. 2002;63:200–210. doi: 10.1016/S0198-8859(01)00381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wetzler M, Baer MR, Stewart SJ, Donohue K, Ford L, Stewart CC, Repasky EA, Ferrone S. HLA Class I antigen cell surface expression is preserved on acute myeloid leukemia blasts at diagnosis and at relapse. Leukemia. 2001;15:128–133. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abushok DV, Duke JL, Xie HM, Stanley N, Atienza J, Perdigones N, Nicholas P, Ferriola D, Li Y, Huang H, Ye W, Morrissette JJD, Kearns J, Porter DL, Podsakoff GM, Eisenlohr LC, Biegel JA, Chou ST, Monos DS, Bessler M, Olson TS. Somatic HLA mutations expose the role of class I-mediated autoimmunity in aplastic anemia and its clonal complications. Blood Adv. 2017;1:1900–1910. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017010918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jordanova ES, Riemersma SA, Philippo K, Schuuring E, Kluin PM. Beta2-microglobulin aberrations in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the testis and the central nervous system. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:393–398. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perea F, Sánchez-Palencia A, Gómez-Morales M, Bernal M, Concha Á, García MM, González-Ramírez AR, Kerick M, Martin J, Garrido F, Ruiz-Cabello F, Aptsiauri N. HLA class I loss and PD-L1 expression in lung cancer: impact on T-cell infiltration and immune escape. Oncotarget. 2017;9:4120–4133. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenthal R, Cadieux EL, Salgado R, Bakir MA, Moore DA, Hiley CT, Lund T, Tanić M, Reading JL, Joshi K, Henry JY, Ghorani E, Wilson GA, Birkbak NJ, Jamal-Hanjani M, Veeriah S, Szallasi Z, Loi S, Hellmann MD, Feber A, Chain B, Herrero J, Quezada SA, Demeulemeester J, Van Loo P, Beck S, McGranahan N, Swanton C. Neoantigen-directed immune escape in lung cancer evolution. Nature. 2019;567:479–485. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1032-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jordanova ES, Riemersma SA, Philippo K, Giphart-Gassler M, Schuuring E, Kluin PM. Hemizygous deletions in the HLA region account for loss of heterozygosity in the majority of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of the testis and the central nervous system. Genes Chromosom Cancer. 2002;35:38–48. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sebastián E, Alcoceba M, Martín-García D, Blanco Ó, Sanchez-Barba M, Balanzategui A, Marín L, Montes-Moreno S, González-Barca E, Pardal E, Jiménez C, García-Álvarez M, Clot G, Carracedo Á, Gutiérrez NC, Sarasquete ME, Chillón C, Corral R, Prieto-Conde MI, Caballero MD, Salaverria I, García-Sanz R, González M. High-resolution copy number analysis of paired normal-tumor samples from diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:253–262. doi: 10.1007/s00277-015-2552-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Albertsson PA, Basse PH, Hokland M, Goldfarb RH, Nagelkerke JF, Nannmark U, Kuppen PJ. NK cells and the tumour microenvironment: implications for NK-cell function and anti-tumour activity. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:603–609. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.