Abstract

The anti-tumor efficacy of TCR-engineered T cells in vivo depends largely on less-differentiated subsets such as T cells with naïve-like T cell (TN) phenotypes with greater expansion and long-term persistence. To increase these subsets, we compared the generation of New York esophageal squamous cell carcinoma-1 (NY-ESO-1)-specific T cells under supplementation with either IL-2 or IL-7/IL-15. PBMCs were transduced with MS3II-NY-ESO-1-siTCR retroviral vector. T cell generation was adapted from a CD19-specific CART cell production protocol. Comparable results in viability, expansion and transduction efficiency of T cells under stimulation with either IL-2 or IL-7/IL-15 were observed. IL-7/IL-15 led to an increase of CD4+ T cells and a decrease of CD8+ T cells, enriched the amount of TN among CD4+ T cells but not among CD8+ T cells. In a 51Cr release assay, similar specific lysis of NY-ESO-1-positive SW982 sarcoma cells was achieved. However, intracellular cytokine staining revealed a significantly increased production of IFN-γ and TNF-α in T cells generated by IL-2 stimulation. To validate these unexpected findings, NY-ESO-1-specific T cell production was evaluated in another protocol originally established for TCR-engineered T cells. IL-7/IL-15 increased the proportion of TN. However, the absolute number of TN did not increase due to a significantly slower expansion of T cells with IL-7/IL-15. In conclusion, IL-7/IL-15 does not seem to be superior to IL-2 for the generation of NY-ESO-1-specific T cells. This is in sharp contrast to the observations in CD19-specific CART cells. Changes of cytokine cocktails should be carefully evaluated for individual vector systems.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00262-019-02354-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Adoptive T cell transfer, T cell receptor, NY-ESO-1, Interleukin

Introduction

Adoptive cell therapy (ACT) using TCR-engineered T cells that bind to cancer-specific antigens is emerging as a potentially curative treatment strategy for cancer [1]. The clinical workflow of ACT with TCR-engineered T cells consists of three parts: acquisition of autologous immune cells, ex vivo expansion and manipulation of T cells including TCR gene transfer, and re-infusion of T cells back to the patient with the appropriate tumor-specific antigen and HLA restriction [2].

The cancer-testis antigen NY-ESO-1 is expressed on a variety of tumor entities including melanoma [3, 4], soft-tissue sarcoma [5, 6] and multiple myeloma [7, 8]. Restricted expression of NY-ESO-1 in adult germ tissue that lacks MHC molecules offers an appropriate target for T cells with reduced on-target toxicity [9]. Clinical trials using NY-ESO-1-specific T cells have demonstrated significant tumor regression in a variety of cancer entities including melanoma [10, 11], synovial sarcoma [12] and multiple myeloma [13]. In addition, several trials combining NY-ESO-1-specific T cells with other immunotherapeutic strategies including vaccines and checkpoint inhibitors are ongoing [14].

Despite encouraging response rates in clinical trials, treatment failure is common, mostly achieving only transient tumor regression in the majority of patients [11]. Intra- and inter-tumor heterogeneity of NY-ESO-1 expression accounts at least in part for this observation [15]. Therefore, TCR-engineered T cell optimization is ongoing addressing several aspects: Demethylating agents can increase NY-ESO-1 expression and may enhance NY-ESO-1 ACT in poorly immunogenic tumors [14]. The inhibition of endogenous TCR expression can prevent TCR mispairing, resulting in higher surface expression of tumor-specific TCRs and a reduction of off-target toxicity [16, 17]. An enhancement of TCR αβ affinity can improve target recognition [18], and coupling TCR genes with co-stimulatory molecules may enhance T cell activation [19].

Another important aspect for successful cellular immunotherapy is the composition of T cell subsets within the cell product. Several studies have suggested that less-differentiated T cells such as naïve-like T cells (TN) or stem cell memory T cells (TSCM) comprising the capacity of greater expansion and longer in vivo persistence convey superior anti-tumor efficacy when compared to more differentiated effector T cells [20–22]. The composition of the cytokine cocktail used for T cell generation has an important impact on ex vivo T cell expansion and immunophenotype. In the past, the use of IL-2 was established as a gold standard for T cell culture. More recently, with a better understanding of in vivo T cell homeostasis, IL-7 and IL-15 have emerged as important cytokines for the maintenance of a naïve- or memory-like T cell phenotype [23–25]. A previous study demonstrated that IL-7 and IL-15, rather than IL-2, could efficiently enrich TSCM [26]. The optimal culture condition for TCR-engineered T cells is not yet defined.

In this study, we compared the production of NY-ESO-1-specific T cells under supplementation of the culture medium with either IL-2 or IL-7/IL-15 using two different manufacturing protocols. The focus was to determine the effects of different cytokine cocktails on viability, expansion, and T cell subsets as well as on effector function in NY-ESO-1-specific T cells.

Materials and methods

Primary cells

Peripheral blood samples from healthy donors (HDs) were obtained at the Heidelberg University Hospital. Mononuclear cells were purified by Ficoll density gradient (Linaris, Dossenheim, Germany) and cryopreserved.

Cell lines

The soft-tissue sarcoma cell lines SW982 (HLA-A2-positive NY-ESO-1-positive) and SYO-1 (HLA-A2-negative NY-ESO-1-negative) were expanded in DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), while Fuji (HLA-A2-positive NY-ESO-1-negative) and MLS-1765-92 (HLA-A2-negative NY-ESO-1-positive) were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), both supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific), at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

NY-ESO-1-specific T cell generation and expansion

Cryopreserved human PBMCs from HDs were thawed and activated according to two different protocols. Protocol 1 was based on our previous publications on CD19-specific CART cell generation [27–29] and protocol 2 was adapted from the NY-ESO-1 generation protocol that was used for a clinical trial in Japan (NCT02869217). Major differences of the two protocols are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Culture conditions and main procedures of two different protocols for the generation of NY-ESO-1-specific T cells. Major differences are displayed for culture conditions (a) and time schedule (b) according to protocol 1 and protocol 2. P1 protocol 1, P2 protocol 2, CM culture medium

For protocol 1, the culture medium consisted of 45% RPMI 1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 45% Click’s Medium (EHAA) (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA, USA), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 2 mM l-glutamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Activation of PBMCs was performed for 3 days in non-tissue culture-treated 24-well plates (Corning, NY, USA) after coating overnight with 0.5 ml of 1 µg/ml anti-CD3 (OKT3; Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA) and 1 µg/ml anti-CD28 (Biolegend). On day 2, two different cytokine cocktails were added: 4400 U/ml IL-7 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and 100 U/ml IL-15 (R&D Systems) vs 100 U/ml IL-2 (Novartis, Nuremberg, Germany). On day 3, 5 × 105 activated T cells in 2 ml culture medium per well were transduced with MS3II-NY-ESO-1-siTCR retroviral vector (Prof. H. Shiku, Mie University, Tsu, Japan) in 24-well non-tissue culture-treated plates (Corning) previously coated with 7 µg/ml retronectin (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) dissolved in Dulbecco’s PBS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

For protocol 2, the culture medium consisted of GT-T551 (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan), 2% human serum albumin (US biological, Massachusetts, USA), 0.6% human serum (ZenBio, NC, USA) supplemented with either 4400 U/ml IL-7 (R&D Systems) and 100 U/ml IL-15 (R&D Systems) or 600 U/ml IL-2 (Novartis). Activation of PBMCs was performed for 4 days in non-tissue culture-treated 12-well plates (Corning) previously coated overnight with 0.4 ml of 5 µg/ml anti-CD3 (OKT3; Biolegend) and 25 µg/ml retronectin (Takara Bio) diluted in anticoagulant citrate dextrose solution (ACD-A; Terumo, Tokyo, Japan). On day 4, 3.8 × 105 activated T cells suspended in 0.95 ml culture medium per well were transduced with the MS3II-NY-ESO-1-siTCR retroviral vector in 24-well non-tissue culture-treated plates (Corning) coated with 20 µg/ml retronectin (Takara) in ACD-A (Terumo).

For both protocols, culture medium change with fresh addition of cytokines was performed on days 7, 10 and 14. T cells were cultivated in 6-well tissue culture plates (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) and transferred to T25 or T75 tissue culture flasks (Sarstedt) depending on the total cell number.

Flow cytometry

The LIVE/DEAD® Fixable Near-IR Dead Cell Stain Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to exclude dead cells. The PE-conjugated A0201 NY-ESO-1-tetramer (Prof. H. Shiku, Mie University, Tsu, Japan) was used to identify NY-ESO-1-specific TCR expression. The following fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies were used for immunophenotyping of the surface markers: anti-CD3-V510 (AmCyan), anti-CD8-PerCP, anti-CD45RA-APC, anti-PD-1-Alexa Fluor 488, anti-TIM-3-Brilliant Violet 421, anti-CXCR3-Alexa Fluor 488 (all from Biolegend), anti-CD4-Alexa Fluor 700, anti-CCR7-PE-Cy7, anti-CD62L-eFluor 450 and anti-CD3-eFlour 610 (all from eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA). For intracellular cytokine staining, T cells were co-cultured with HLA-A2-positive NY-ESO-1-positive SW982 cells or HLA-A2-negative NY-ESO-1-negative SYO-1 cells for 6 h in 96-well U-bottom microplates (Greiner BioOne, Frickenhausen, Germany). Intracellular cytokine retention, fixation, permeabilization, intracellular IFN-γ and TNF-α staining and data acquisition were performed as described previously [28]. Gating strategies and representative dot plots are displayed in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity of the NY-ESO-1-specific T cells was assessed by a 12-h chromium-51 (51Cr) release assay. HLA-A2-positive NY-ESO-1-positive SW982 cells were used as target cells, whereas HLA-A2-negative NY-ESO-1-negative SYO-1 cells, HLA-A2-positive NY-ESO-1-negative Fuji cells and HLA-A2-negative NY-ESO-1-positive MLS-1765-92 cells served as negative controls. All cell lines were labeled with 51Cr (Hartmann Analytic, Braunschweig, Germany) and co-incubated in triplicate with T cells (effector cells) in 96-well U-bottom microplates (Greiner Bio-One) at E:T ratios of 10:1, 5:1, 2.5:1, and 1:1 at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Maximum and background 51Cr release of target cells were assessed by adding 1% Triton X-100 solution (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) or culture medium without T cells, respectively. Radioactivity was measured on a 1414 WinSpectral liquid scintillation counter (PerkinElmer). Specific lysis was calculated according to the following formula: % specific lysis = (51Cr release in the test well − background 51Cr release)/(maximum 51Cr release − background 51Cr release) × 100.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). The parametric two-way t test was used for data comparison. A p value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Graphs and tables were designed using Excel (Microsoft) and Prism 6 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). If not otherwise mentioned, results are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Results

Influence of IL-2 and IL-7/IL-15 on viability, expansion and transduction efficiency using protocol 1

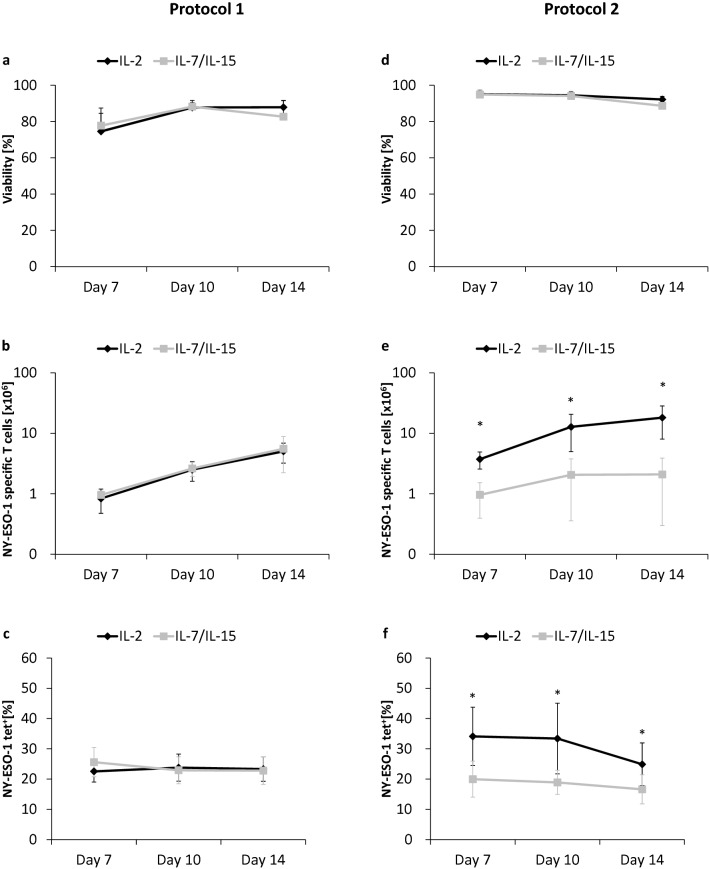

Viability, expansion and transduction efficiency of T cells were assessed longitudinally during the generation of NY-ESO-1-specific T cells with PBMCs from seven HDs. Similar viability (Fig. 2a), expansion (Fig. 2b) and transduction efficiency (Fig. 2c) were observed for NY-ESO-1-specific T cells generated in media supplemented with either IL-2 or IL-7/IL-15. Gating and analyzing strategies are displayed in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Viability, expansion, and transduction efficiency. The figure shows results for protocol 1 (a–c; n = 7) and for protocol 2 (d–f; n = 7) with either IL-2 (black lines) or IL-7/IL-15 (gray lines). Viability (a, d), cell expansion (b, e) and transduction efficiency (c, f) were assessed on days 7, 10, and 14 of T cell culture. Mean values were calculated for each group. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Statistical significance was calculated using a paired two-way student t test. Significance (p values < 0.05) is indicated by an asterisk (*)

Influence of IL-2 and IL-7/IL-15 on viability, expansion and transduction efficiency using protocol 2

Viability, expansion and transduction efficiency of T cells were assessed longitudinally during NY-ESO-1-specific T cell culture with PBMCs from seven HDs. Viability (Fig. 2d) of NY-ESO-1-specific T cells cultured in media supplemented with either IL-2 or IL-7/IL-15 was equal, while a significantly higher expansion rate was observed for IL-2-based production (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 3.73 ± 1.17 vs 0.96 ± 0.57 × 106 cells, p < 0.001, day 7; 12.78 ± 7.82 vs 2.06 ± 1.70 × 106 cells, p = 0.005, day 10; 18.16 ± 10.15 vs 2.09 ± 1.79 × 106 cells, p = 0.003, day 14; Fig. 2e). Moreover, in the presence of IL-2, transduction efficiency was significantly higher when compared to IL-7/IL-15-supplemented media (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 34 ± 10% vs 20 ± 6%, p < 0.001, day 7; 33 ± 12% vs 19 ± 4%, p = 0.004, day 10; 25 ± 7% vs 17 ± 5%, p = 0.002, day 14; Fig. 2f).

Distribution of different NY-ESO-1-specific T cell subsets using protocol 1

The supplemented cytokines had a significant impact on the distribution of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and CD4+ T helper (Th) cells in the cell product: culture in the presence of IL-2 generated significantly more CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and less CD4+ Th cells (CD8+ T cells on day 14, IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 51 ± 5% vs 31 ± 10%; p < 0.001; Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

Distribution of different NY-ESO-1-specific T cell subsets. Evolution of CD3+/CD4+ (solid lines) and CD3+/CD8+ (dashed lines) NY-ESO-1-specific T cells (n = 7) was assessed on days 7, 10, and 14 of T cell culture following protocol 1 and 2 (a, c). NY-ESO-1-specific T cell subsets were defined by CCR7 and CD45RA expression (n = 7). TN were defined as CD45RA+CCR7+, TCM as CD45RA−CCR7+, TEM as CD45RA−CCR7−, and TE as CD45RA+CCR7− T cells. Differences in the proportion of TN (dark black block), TCM (light gray block), TEM (dark gray block) and TE (light black block) were compared between IL-2 and IL-7/IL-15-based T cell culture using protocol 1 and 2 (b, d). Mean values were calculated for each group. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Statistical significance was calculated using a paired two-way student t test. Significance (p values < 0.05) is indicated by an asterisk (*)

T cell subsets were defined by CCR7 and CD45RA expression into TN (CD45RA+CCR7+), central memory-like T cells (TCM: CD45RA−CCR7+), effector memory-like T cells (TEM: CD45RA−CCR7−), and terminally differentiated effector-like T cells (TE: CD45RA+CCR7−). After in vitro activation of T cells, nearly all T cells expressed CD95. Therefore, T cells classified as TN can be considered as TSCM-like cells [21, 28]. Figure 3b shows the distribution of different T cell subsets generated in media containing IL-2 or IL-7/IL-15 according to protocol 1. IL-2 mediated significantly higher frequencies of TCM on days 7, 10, and 14 (p = 0.03, p < 0.001, p = 0.003) as well as of TEM on days 10 and 14 (p = 0.001, p = 0.004). In contrast, IL-7/IL-15 led to significantly higher frequencies of TE on days 7 and 10 (p = 0.009, p = 0.003) as well as of TN on day 14 (p = 0.005).

Distribution of different NY-ESO-1-specific T cell subsets using protocol 2

In contrast to protocol 1 (Fig. 3a), cell culture using protocol 2 with IL-7/IL-15 yielded significantly more CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and less CD4+ Th cells on day 14 compared to IL-2-based T cell culture (CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 62 ± 14% vs 72 ± 12%; p < 0.001; Fig. 3c). IL-2 mediated significantly higher percentages of TE on days 10 and 14 (p = 0.002, p < 0.001), of TEM on days 10 and 14 (p = 0.01, p = 0.001) as well as of TCM on day 10 (p = 0.001). In contrast, IL-7/IL-15 led to a significantly higher percentage of TN on days 10 and 14 (p < 0.001, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3d).

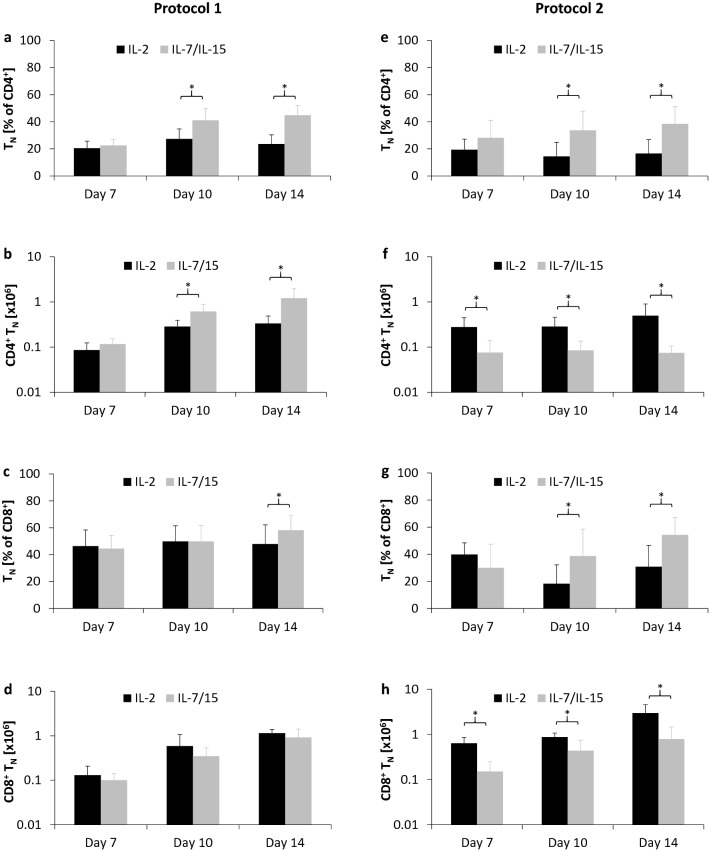

Relative distribution and absolute number of NY-ESO-1-specific TN applying protocol 1

The cytokine-cocktail had a significant impact on the distribution of CD4+ Th cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells: compared to IL-2, IL-7/IL-15 resulted in a significantly higher percentage of TN (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 27 ± 7% vs 41 ± 9%, p = 0.004, day 10; 24 ± 7% vs 45 ± 7%, p < 0.001, day 14; Fig. 4a) as well as increased the absolute number of TN (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 0.28 ± 0.11 vs 0.61 ± 0.27 × 106 cells, p = 0.006, day 10; 0.33 ± 0.15 vs 1.21 ± 0.75 × 106 cells, p = 0.01, day 14; Fig. 4b) among CD4+ T cells on days 10 and 14. The percentage of CD8+ TN on day 14 was significantly higher when T cells were cultured under supplementation with IL-7/IL-15 (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 48 ± 14% vs 58 ± 11%, p = 0.04; Fig. 4c). However, in contrast to CD4+ T cells, the absolute number of TN within CD8+ T cells did not differ between IL-2 and IL-7/IL-15-based culture (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4.

Relative distribution and absolute number of TN. Differences in the amount of NY-ESO-1-specific TN (n = 7) were compared for different culture conditions containing IL-2 (black bars) or IL-7/IL-15 (gray bars) for CD3+/CD4+ (%, a, e; absolute number, b, f) and CD3+/CD8+ (%, c, g; absolute number, d, h) T cells. Mean values were calculated for each group. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Statistical significance was calculated using a paired two-way student t test. Significance (p values < 0.05) is indicated by an asterisk (*)

Relative distribution and absolute number of NY-ESO-1-specific TN applying protocol 2

When compared to IL-2, IL-7/IL-15 significantly increased the percentage of TN in CD4+ T cells on days 10 and 14 of T cell culture (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 14 ± 10% vs 34 ± 14%, p < 0.001, day 10; 17 ± 10% vs 38 ± 13%, p < 0.001, day 14; Fig. 4e). However, the absolute number of CD4+ TN was significant higher in the cell product using IL-2 when compared to IL-7/IL-15 (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 0.28 ± 0.17 vs 0.08 ± 0.07 × 106 cells, p = 0.02, day 7; 0.29 ± 0.17 vs 0.08 ± 0.05 × 106 cells, p = 0.03, day 10; 0.50 ± 0.40 vs 0.07 ± 0.03 × 106 cells, p = 0.03, day 14; Fig. 4f). This is mainly attributed to the higher expansion rate achieved with protocol 2 employing IL-2 (Fig. 2e). In this context, CD8+ TN shared similar features with CD4+ TN. IL-7/IL-15 led to a significantly higher percentage of TN (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 18 ± 14% vs 39 ± 20%, p = 0.003, day 10; 31 ± 16% vs 54 ± 13%, p < 0.001, day 14; Fig. 4g) among CD8+ T cells whereas a higher absolute number of CD8+ TN (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 0.64 ± 0.22 vs 0.15 ± 0.10 × 106 cells, p < 0.001, day 7; 0.88 ± 0.20 vs 0.44 ± 0.31 × 106 cells, p = 0.01, day 10; 2.97 ± 1.58 vs 0.79 ± 0.67 × 106 cells, p = 0.004, day 14; Fig. 4h) was obtained using IL-2.

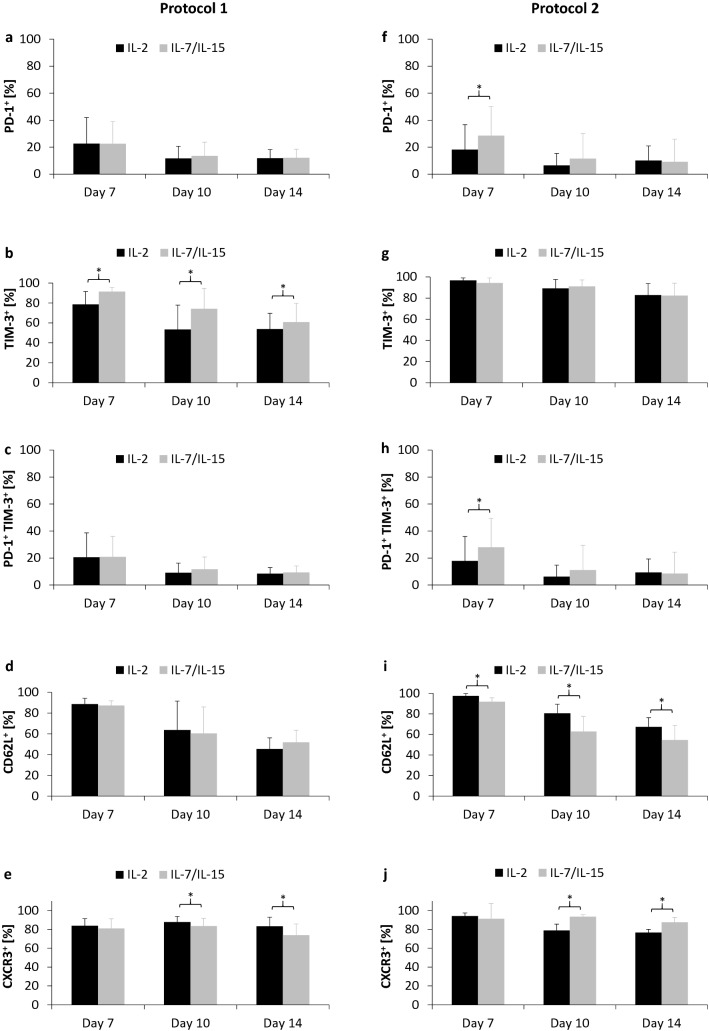

Analysis of exhaustion and homing markers using protocol 1

To assess exhaustion status and homing markers induced by different cytokines, the expression of exhaustion markers PD-1 and TIM-3, as well as of homing markers CD62L and CXCR3 was evaluated by flow cytometry. PD-1 expression (Fig. 5a) was similar between NY-ESO-1-specific T cells cultured under supplementation with either IL-2 or IL-7/IL-15, whereas IL-2 led to a significantly lower expression of TIM-3 on days 7, 10, and 14 (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 79 ± 13% vs 91 ± 4%, p = 0.02, day 7; 53 ± 24% vs 74 ± 20%, p < 0.001, day 10; 54 ± 16% vs 61 ± 19%, p = 0.01, day 14; Fig. 5b). Co-expression of PD-1 and TIM-3 was further assessed and an equal distribution of double-positive cells was observed irrespective of the cytokine cocktail used (Fig. 5c). CD62L levels (Fig. 5d) did not show any significant differences. In contrast, CXCR3 levels were significantly higher on days 10 and 14 when IL-2 was supplemented into the culture medium (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 88 ± 6% vs 84 ± 8%, p = 0.01, day 10; 83 ± 10% vs 74 ± 12%, p < 0.001, day 14; Fig. 5e).

Fig. 5.

Exhaustion and homing markers of NY-ESO-1-specific T cells. NY-ESO-1-specific T cells (n = 7) cultured in media supplemented with either IL-2 (black bars) or IL-7/IL-15 (gray bars) were compared for expression of exhaustion and homing markers. The exhaustion markers PD-1 (a, f) and TIM-3 (b, g), co-expression of PD-1 and TIM-3 (c, h) as well as expression of the homing markers CD62L (d, i) and CXCR3 (e, j) were assessed on days 7, 10, and 14. Mean values were calculated for each group. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Statistical significance was calculated using a paired two-way student t test. Significance (p values < 0.05) is indicated by an asterisk (*)

Analysis of exhaustion and homing markers using protocol 2

On day 7, PD-1 expression was significantly higher in T cell production under supplementation with IL-7/IL-15 (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 18 ± 19% vs 29 ± 22%, p = 0.003; Fig. 5f). TIM-3 levels were similar using both cytokine cocktails (Fig. 5g). Moreover, IL-7/IL-15 resulted in a significantly higher percentage of PD-1/TIM-3 co-expressing T cells on day 7 (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 18 ± 18% vs 28 ± 21%, p = 0.004, Fig. 5h). CD62L levels were significantly lower on days 7, 10, and 14 using IL-7/IL-15 (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 98 ± 2% vs 92 ± 4%, p = 0.004, day 7; 81 ± 9% vs 63 ± 15%, p = 0.002, day 10; 67 ± 9% vs 55 ± 14%, p = 0.02, day 14; Fig. 5i). CXCR3 levels were significantly higher on days 10 and 14 when IL-7/IL-15 was added to the culture medium (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 79 ± 7% vs 93 ± 2%, p = 0.001, day 10; 77 ± 3% vs 88 ± 5%, p < 0.001, day 14; Fig. 5j).

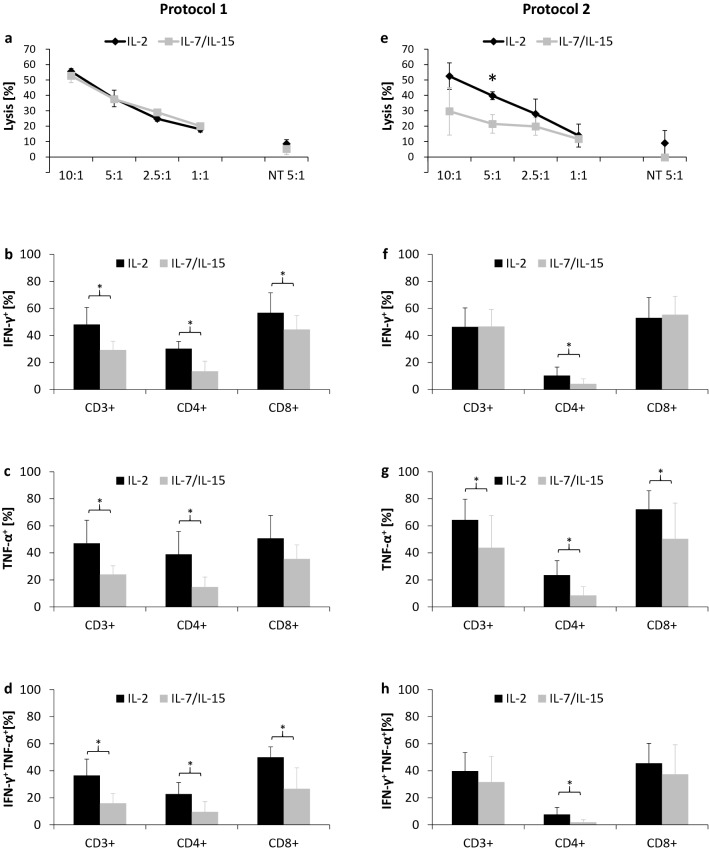

Functional evaluation of NY-ESO-1-specific T cells generated according to protocol 1

51Cr release assay was performed on day 14 and intracellular cytokine staining on day 15 of T cell culture. HLA-A2-positive and NY-ESO-1-positive SW982 cells were used as target cells. In 51Cr release assay, the lytic activity between NY-ESO-1-specific T cells generated under either IL-2 or IL-7/IL-15 condition was comparable at E:T ratios ranging from 10:1 to 1:1 (Fig. 6a). NY-ESO-1-specific T cells could selectively lyse NY-ESO-1-positive cells and did not exhibit significant lysis of SYO-1 (HLA-A2-negative NY-ESO-1-negative), Fuji (HLA-A2-positive NY-ESO-1-negative) and MLS-1765-92 cells (HLA-A2-negative NY-ESO-1-positive) (Supplementary Fig. 2a).

Fig. 6.

Functional evaluation of NY-ESO-1-specific T cells. Cytotoxicity of NY-ESO-1-specific T cells (n = 3) was evaluated by 51Cr release assay after co-culture with SW982 target cells (HLA-A2-positive NY-ESO-1-positive) for 12 h. Average lysis was assessed at different effector (NY-ESO-1-specific T cells) to target (SW982 cells) ratios (10:1, 5:1, 2.5:1, and 1:1). Non-transduced T cells and SW982 cells at a ratio of 5:1 were used as control. Each experiment was performed in triplicate (a, e). Intracellular production of IFN-γ and TNF-α (protocol 1: n = 4, protocol 2: n = 7) was measured after stimulation with SW982 cells for 6 h. Overall IFN-γ (b, f) and TNF-α production (c, g) as well as multifunctional NY-ESO-1-specific T cells producing both TNF-α and IFN-γ (d, h) were determined in CD3+, CD3+/CD4+, and CD3+/CD8+ cells. Mean values were calculated for each group. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Statistical significance was calculated using a paired two-way student t test. Significance (p values < 0.05) is indicated by an asterisk (*). NT non-transduced T cells

For intracellular cytokine staining of IFN-γ and TNF-α, T cells were incubated for 6 h with SW982 cells. Intracellular IFN-γ levels were significantly higher under the IL-2-based production in all CD3+ T cells (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 48 ± 13% vs 29 ± 6%, p = 0.03; Fig. 6b) as well as CD4+ Th cells (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 30 ± 5% vs 14 ± 7%, p = 0.005; Fig. 6b) and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 57 ± 15% vs 45 ± 10%, p = 0.03; Fig. 6b). In addition, IL-2 achieved significantly higher TNF-α levels in all CD3+ T cells (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 47 ± 17% vs 24 ± 13%, p = 0.02; Fig. 6c) as well as CD4+ T cells (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 39 ± 17% vs 15 ± 12%, p = 0.04; Fig. 6c). In CD8+ T cells, only a trend towards higher TNF-α levels was observed under the IL-2-based production without reaching statistical significance (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 51 ± 17% vs 36 ± 20%, p = 0.13; Fig. 6c). Furthermore, the multifunctionality of NY-ESO-1-specific T cells producing both cytokines, TNF-α and IFN-γ, was evaluated. NY-ESO-1-specific T cells generated by IL-2 stimulation had a significantly higher proportion of multifunctional T cells (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: CD3+, 37 ± 12% vs 16 ± 7%, p = 0.01; CD3+/CD4+, 23 ± 9% vs 10 ± 8%, p = 0.02; CD3+/CD8+, 50 ± 8% vs 27 ± 16%, p = 0.046; Fig. 6d). Baseline cytokine production after 6 h incubation with SYO-1 cells (HLA-A2-negative NY-ESO-1-negative) or without any cell stimulation is displayed in Supplementary Fig. 2b, c.

Functional evaluation of NY-ESO-1-specific T cells generated according to protocol 2

In 51Cr release assay, NY-ESO-1-specific T cells generated under IL-2 condition showed stronger lytic activity at high E:T ratios, reaching significance at 5:1 when compared to T cells generated in the presence of IL-7/IL-15 (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 52 ± 9% vs 30 ± 15%, p = 0.09, 10:1; 40 ± 3% vs 22 ± 6%, p = 0.01, 5:1; Fig. 6e).

NY-ESO-1-specific T cells were incubated for 6 h with SW982 cells on day 15 before intracellular cytokine staining. CD8+ T cells under supplementation with either IL-2 or IL-7/IL-15 generated similar amounts of IFN-γ (Fig. 6f), whereas CD4+ T cells yielded higher level of IFN-γ under supplementation with IL-2 (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: CD3+/CD4+, 10 ± 6% vs 4 ± 4%, p = 0.03; Fig. 6f). TNF-α production was significantly higher in all CD3+ (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 64 ± 15% vs 44 ± 24%, p = 0.01; Fig. 6g), CD4+ (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 24 ± 11% vs 9 ± 6%, p = 0.003; Fig. 6g) and CD8+ T cells (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 72 ± 14% vs 50 ± 26%, p = 0.02; Fig. 6g) generated by IL-2 stimulation. However, irrespective of the cytokine cocktail, the amount of multifunctional NY-ESO-1-specific CD3+ T cells producing both TNF-α and IFN-γ was comparable (Fig. 6h).

CD19-specific CART cells generated according to protocol 1

CD19-specific CART cells were generated in the presence of either IL-2 or IL-7/IL-15 according to protocol 1. PBMCs from five HDs were used. The evolution of CD19-specific CART cells was determined on days 10 and 14 of T cell production. Comparable results on viability (Supplementary Fig. 3a), transduction efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 3b) and absolute number of CD19-specific CART cells (Supplementary Fig. 3c) were observed in the presence of either IL-2 or IL-7/IL-15. T cell culture with IL-2 had a trend towards a higher proportion of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and less CD4+ Th cells without reaching significance on day 14 (CD8+ T cells: IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 44 ± 16% vs 36 ± 18%, p = 0.25; Supplementary Fig. 3d). IL-7/IL-15 significantly increased the percentages of TN in CD4+ T cells on day 10 (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 4 ± 4% vs 11 ± 6%, p = 0.03; Supplementary Fig. 3e) and CD8+ T cells on day 14 (IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15: 14 ± 13% vs 32 ± 23%, p = 0.03; Supplementary Fig. 3f). However, cell culture with IL-7/IL-15 showed only a trend towards a higher absolute number of CD4+ TN (Supplementary Fig. 3g) or CD8+ TN (Supplementary Fig. 3h) when compared to IL-2. For functional characterization of T cells generated in the presence of either IL-2 or IL-7/IL-15, CD19-specific CART cells were incubated for 6 h with CD19-positive Daudi cells. Intracellular cytokine staining was performed for IFN-γ and TNF-α. Similar production of these cytokines in CD4+ (Supplementary Fig. 3i) and CD8+ (Supplementary Fig. 3j) CD19-specific CART cells generated with either IL-2 or IL-7/IL-15-based production were detected.

Discussion

ACT with TCR-engineered T cells constitutes a promising treatment option for both solid tumors and hematological malignancies. Besides an optimal vector design, the T cell production process is of crucial importance in ACT. Culture conditions including type of culture media, activation condition, number of activated T cells and retronectin concentration for transduction, time schedule and cytokine cocktails are factors that need to be taken into consideration for the production process. The cytokine cocktail is an essential element of tumor-specific T cell manufacturing with a major impact on the final cell product and thereby therapeutic success. By comparing T cell culture employing either IL-2 or IL-7/IL-15 in two different manufacturing protocols separately (Fig. 1), this study aims to identify the optimal cytokines for NY-ESO-1-specific T cell generation providing sufficient cell expansion and an optimal phenotype for long-term in vivo T cell persistence.

Using both evaluated production protocols, the viability of NY-ESO-1-specific T cells cultured in the presence of either IL-2 or IL-7/IL-15 was similar. Applying protocol 1, comparable cell expansion and transduction efficiency were observed. However, when using protocol 2, a significantly higher cell expansion and higher transduction efficiency could be observed when IL-2 was supplemented. The higher proliferation can be probably attributed to higher levels of IL-2 under the condition of protocol 2 when compared to protocol 1 (600 U/ml vs 100 U/ml), as higher levels of IL-2 are known to induce T cell proliferation [30]. Since cell division is mandatory for retroviral integration, the higher proliferation rate might have contributed to the higher transduction efficiency. In contrast, the use of IL-7/IL-15 under the conditions of protocol 2 resulted in limited cell proliferation and did not yield sufficient cells for cellular therapies.

IL-7/IL-15 enriched CD4+ T cells and decreased the number of CD8+ T cells in comparison to IL-2 following protocol 1. This is in line with a previous study [31] and our previous report in CD19-specific CART cells [27]. However, it was unexpected that IL-7/IL-15-based T cell generation showed enrichment of CD8+ T cells when applying protocol 2. It has been reported that retronectin-based T cell activation enriches CD8+ T cells ex vivo [28, 32, 33] whereas anti-CD28 used for T cell activation additionally increases CD4+ T cells even in the context of retronectin-based T cell activation [28]. Therefore, a higher frequency of CD4+ T cells and a lower frequency of CD8+ T cells observed under culture in the presence of IL-7/IL-15 may be reversed through the presence of retronectin and absence of anti-CD28 for T cell activation using protocol 2.

Recently, IL-2, the gold standard growth factor for T cell culture, has been challenged by common γ-chain cytokines such as IL-7, IL-15, IL-21 and the non-γ-chain cytokine IL-12. Accumulating studies have shown their superiority over IL-2. IL-12 together with IL-7 or IL-21 yielded CD62Lhigh CD28high CD127high CD27high CCR7high TCR engineered CD8+ T cells which engrafted significantly better than cells grown in the presence of IL-2 in mouse models [34]. IL-12 maintained high levels of CD62L on T cells, resulting in a superior anti-tumor activity [35]. IL-7 and IL-15 promoted less-differentiated cells, CD27 and CD28 expression ex vivo, while IL-15 and IL-21 exposed T cells showed the longest persistence and best tumor eradication in a mouse model [36]. In our previous study we demonstrated that after in vitro activation, nearly all T cells expressed CD95 [28]. Therefore, the CCR7+CD45RA+ TN subset which we are referring to as the less-differentiated T cell subset in this study can be considered as TSCM subset. CART cells with a TSCM phenotype were reported to harbor a higher capacity for in vivo expansion as well as for longer persistence. TSCM can be enriched ex vivo through the addition of IL-7/IL-15 instead of IL-2 for T cell culture [25]. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to evaluate the combination of IL-7 and IL-15 to enrich this less-differentiated T cell subset. Consistent in both protocols, IL-7/IL-15 augmented a subset of less-differentiated NY-ESO-1-specific T cells. However, the enrichment of TN when applying protocol 1 occurred mainly in the CD4+ T cells. Addition of IL-2 yielded a significantly higher number of CD8+ T cells. Therefore, a similar absolute number of CD8+ TN was observed when using protocol 1. This selective enrichment of CD4+ TN was not observed in CD19-specific CART cell production under supplementation with IL-7/IL-15. The role of CD4+ T cells in the setting of TCR-engineered T cells is not clearly defined yet. In our functional assays, we also observed cytokine production of CD4+ NY-ESO-1-specific T cells. CD4+ T cells may additionally boost antitumor activity. Protocols for specific enrichment of NY-ESO-1-specific CD4+ T cells have been reported [37]. However, CD8+ NY-ESO-1-specific T cells will probably provide the main anti-tumor activity due to the presentation of the NY-ESO-1 antigen by HLA class I molecules that depend on CD8+ T cells for specific target recognition. In the presence of IL-7/IL-15 using protocol 2, an enrichment of TN occurred in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell compartments. The expansion of T cells was limited with IL-7/IL-15. Therefore, the absolute number of TN was lower when compared to cells obtained in the IL-2-based production. Overall, the benefit of the enrichment of TN does not seem to be sufficient to recommend IL-7/IL-15 instead of IL-2 for the generation of NY-ESO-1-specific T cells.

T cell exhaustion is a major factor which might limit an anti-tumor response. Exhausted T cells have only a limited capacity to proliferate or to release cytokines, and express high levels of inhibitory receptors such as PD-1 and TIM-3 [38]. PD-1 is additionally a T cell activation marker and the expression decreases gradually after transduction. Under the conditions of protocol 1, NY-ESO-1-specific T cells generated with IL-2 or IL-7/IL-15 expressed similar levels of PD-1, which were significantly higher under supplementation with IL-7/IL-15 following protocol 2 on day 7. This prolonged positivity for PD-1 may be at least in part responsible for the decreased expansion of T cells using IL-7/IL-15. TIM-3 levels were significantly higher when using IL-7/IL-15 under the conditions of protocol 1. In contrast, NY-ESO-1-specific T cells expressed comparable levels of TIM-3 between IL-2 and IL-7/IL-15-based generation using protocol 2. T cell exhaustion is often not defined as a sole expression of one exhaustion marker but the combined positivity of several markers. Previous studies have shown that PD-1+/TIM3+ T cells in patients and also in mouse models of solid tumors or hematologic malignancies were dysfunctional and correlated with poor outcome. Co-blockade of TIM-3/Gal-9 and PD-1/PD-L1 pathways restored T cell function to a larger extent when compared to single blockade of either TIM-3/Gal-9 or PD-1/PD-L1 [38–41]. The amount of PD-1+/TIM-3+ cells was comparable in both IL-2 and IL-7/IL-15-based cell productions following protocol 1, whereas IL-7/IL-15 induced higher amounts of PD-1+/TIM-3+ T cells on day 7 following protocol 2 in our study. Further evaluation is required to define the impact of PD-1 and TIM-3 expression on the clinical outcome of patients receiving ACT.

As for homing markers, a preclinical mouse model of ACT demonstrated that expression of CXCR3 by CD8+ T cells is indispensable for tumor control and survival [42, 43]. Another study suggested that CXCR3 plays an essential, non-redundant, cell-autonomous role in mediating CD8+ T cell infiltration into tumors thus leading to antitumor immunity [44]. Moreover, CD62L has been reported to be a critical component for homing of T cells into the lymph node during initial homeostatic proliferation [45]. In our study following protocol 1, we observed similar CD62L expression in both IL-2 and IL-7/IL-15-based T cell cultures while CXCR3 levels were significantly higher in the presence of IL-2 on days 10 and 14. On the other hand, a significantly higher CD62L level and a lower CXCR3 expression were detected in the presence of IL-2 applying protocol 2. Therefore, applying protocol 1, NY-ESO-1-specific T cells generated in the presence of IL-2 might be more likely to migrate into tumor tissue and be more beneficial towards an anti-tumor response. In contrast, NY-ESO-1-specific T cells generated in the presence of IL-2 following protocol 2 might be more likely to migrate into the lymph nodes.

In the current study, the lytic capacity of NY-ESO-1-specific T cells was similar in both IL-2 and IL-7/IL-15-based T cell cultures following protocol 1. This stands in clear contrast to our previous findings with CD19-specific CART cells [27]: CART cells generated under supplementation of the culture medium with IL-2 achieved significantly higher lysis of tumor cells when compared to IL-7/IL-15-based CART cell cultures. However, similar results to CD19-specific CART cells were obtained in our study applying protocol 2: NY-ESO-1-specific T cells from IL-2-based production displayed a significantly stronger lytic activity when compared to cells generated in IL-7/IL-15 containing media. The higher lysis was probably induced by the higher enrichment of TEM and TE cells through IL-2 stimulation when compared to IL-7/IL-15 employing protocol 2. This effect was less prominent for the generation of NY-ESO-1-specific T cells using protocol 1. The distribution of T cell subsets within CD4+ and CD8+ T cells could not explain this discrepancy (Supplementary Fig. 4). On the other hand, GD2-specific CART cells generated in media supplemented with IL-7/IL-15 have been reported to have a higher lytic capacity in a 51Cr release assay when compared to IL-2-based T cell production [32]. Overall, the vector construct may have an important impact on tumor lysis of tumor-specific T cells. In addition, it is difficult to judge the in vivo efficacy of genetically modified T cells with a short-time 51Cr release killing assay.

Cytokine production was significantly higher in T cells generated in the presence of IL-2 using protocol 1. This included IFN-γ and TNF-α as well as multifunctional T cells producing both cytokines. Applying protocol 2, IL-2 mediated higher levels of TNF-α. These findings stand in sharp contrast to our current and previous experience with CD19-specific CART cells as well as data from GD2-specific CART cells [32] where no relevant differences in cytokine secretion between IL-2 vs IL-7/IL-15-based CART cell production were observed. The lower capacity of cytokine production might be at least partially explained by the higher proportion of TN among all T cells generated in media supplemented with IL-7/IL-15. TN are known to have a lower capacity to produce IFN-γ and TNF-α [46, 47]. Moreover, IL-2 led to a less “exhausted” T cell phenotype with lower expression of TIM-3 and PD-1. This may have provided a higher capacity to produce cytokines when compared to T cells generated in media supplemented with IL-7/IL-15. Overall, cytokine production seems to differ majorly between TCR-engineered T cells and CART cells when generated in media supplemented with either IL-2 or IL-7/IL-15.

Cellular therapies, especially therapies with genetically modified cells, are extremely cost intensive. Therefore, cost-effectiveness is a key issue for T cell generation. For IL-2, a clinically approved product (Proleukin®) is available on the market. Therefore, costs are relatively low for ex vivo purposes. In contrast, T cell generation under supplementation with IL-7/IL-15 can be 10–100 × more expensive when compared to IL-2. Considering the relatively low benefits of TN-enrichment in the generation of NY-ESO-1-specific T cells, there is little evidence favoring IL-7/IL-15 over IL-2 in this context.

In conclusion, IL-7/IL-15 does not seem to be superior when compared to a IL-2-based T cell production protocol for the generation of NY-ESO-1-specific T cells. This was in sharp contrast to our and others’ observations in CART cell manufacturing. Changes in cytokine cocktails should be therefore carefully evaluated with distinct vector system and optimized for individual purpose.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- 51Cr

Chromium-51

- ACD-A

Anticoagulant citrate dextrose solution

- ACT

Adoptive cell therapy

- HDs

Healthy donors

- NY-ESO-1

New York esophageal squamous cell carcinoma-1

- TCM

Central memory-like T cell(s)

- TE

Effector-like T cell(s)

- TEM

Effector memory-like T cell(s)

- Th cells

T helper cells

- TN

Naïve-like T cell(s)

- TSCM

Stem cell memory T cell(s)

Author contributions

WG and LS designed the study; WG, JMH and YL performed experiments; WG and LS analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; MS edited the manuscript; MS, LW, MLS, WG, SS, BN, AHK, UG and AS discussed the experimental design; CMT and HS read the manuscript and gave comments; HS provided essential materials; all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded in part by the Government of Baden-Württemberg (Anschubfinanzierung zur Etablierung eines Netzwerks “Brückeninstitutionen für die Regenerative Medizin in Baden-Württemberg”, Kapitel 1403 Tit.Gr. 74), by the DKTK (Deutsches Konsortium für Translationale Krebsforschung) and by the NCT-HD-CAR-1 Grant from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ). Leopold Sellner was supported by the “Physician Scientist-Programm” of the Medical Faculty of Heidelberg, the NCT Heidelberg School of Oncology (HSO) and the “Clinician Scientist Programm” of the German Society of Internal Medicine (DGIM).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and ethical standards

The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Heidelberg (S-254/2016). All studies involving human participants were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Written informed consent for the use of their blood for research purposes was obtained from all healthy donors by the Blood Bank Heidelberg.

Cell line authentication

The soft-tissue sarcoma cell lines SW982 (HLA-A2-positive NY-ESO-1-positive), SYO-1 (HLA-A2-negative NY-ESO-1-negative), Fuji (HLA-A2-positive NY-ESO-1-negative) and MLS-1765-92 (HLA-A2-negative NY-ESO-1-positive) were provided by Prof. H. Shiku (Mie University, Tsu, Japan). All cell lines were authenticated at DSMZ (German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures, Braunschweig, Germany).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Adoptive cell transfer as personalized immunotherapy for human cancer. Science. 2015;348(6230):62–68. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kunert A, Straetemans T, Govers C, Lamers C, Mathijssen R, Sleijfer S, Debets R. TCR-engineered T cells meet new challenges to treat solid tumors: choice of antigen, T cell fitness, and sensitization of tumor milieu. Front Immunol. 2013;4:363. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park TS, Groh EM, Patel K, Kerkar SP, Lee CC, Rosenberg SA. Expression of MAGE-A and NY-ESO-1 in primary and metastatic cancers. J Immunother. 2016;39(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrow C, Browning J, MacGregor D, Davis ID, Sturrock S, Jungbluth AA, Cebon J. Tumor antigen expression in melanoma varies according to antigen and stage. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(3 Pt 1):764–771. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Endo M, de Graaff MA, Ingram DR, Lim S, Lev DC, Briaire-de Bruijn IH, Somaiah N, Bovee JV, Lazar AJ, Nielsen TO. NY-ESO-1 (CTAG1B) expression in mesenchymal tumors. Mod Pathol. 2015;28(4):587–595. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lai JP, Robbins PF, Raffeld M, Aung PP, Tsokos M, Rosenberg SA, Miettinen MM, Lee CC. NY-ESO-1 expression in synovial sarcoma and other mesenchymal tumors: significance for NY-ESO-1-based targeted therapy and differential diagnosis. Mod Pathol. 2012;25(6):854–858. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmitt M, Huckelhoven AG, Hundemer M, Schmitt A, Lipp S, Emde M, Salwender H, Hanel M, Weisel K, Bertsch U, Durig J, Ho AD, Blau IW, Goldschmidt H, Seckinger A, Hose D. Frequency of expression and generation of T-cell responses against antigens on multiple myeloma cells in patients included in the GMMG-MM5 trial. Oncotarget. 2017;8(49):84847–84862. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Rhee F, Szmania SM, Zhan F, Gupta SK, Pomtree M, Lin P, Batchu RB, Moreno A, Spagnoli G, Shaughnessy J, Tricot G. NY-ESO-1 is highly expressed in poor-prognosis multiple myeloma and induces spontaneous humoral and cellular immune responses. Blood. 2005;105(10):3939–3944. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robbins PF, Morgan RA, Feldman SA, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Nahvi AV, Helman LJ, Mackall CL. Tumor regression in patients with metastatic synovial cell sarcoma and melanoma using genetically engineered lymphocytes reactive with NY-ESO-1. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(7):917. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Hughes MS, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Royal RE, Topalian SL, Kammula US, Restifo NP, Zheng Z, Nahvi A, de Vries CR, Rogers-Freezer LJ, Mavroukakis SA, Rosenberg SA. Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes. Science. 2006;314(5796):126–129. doi: 10.1126/science.1129003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robbins PF, Kassim SH, Tran TL, Crystal JS, Morgan RA, Feldman SA, Yang JC, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Sherry RM, Kammula US, Hughes MS, Restifo NP, Raffeld M, Lee CC, Li YF, El-Gamil M, Rosenberg SA. A pilot trial using lymphocytes genetically engineered with an NY-ESO-1-reactive T-cell receptor: long-term follow-up and correlates with response. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(5):1019–1027. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Angelo SP, Melchiori L, Merchant MS, Bernstein D, Glod J, Kaplan R, Grupp S, Tap WD, Chagin K, Binder GK, Basu S, Lowther DE, Wang R, Bath N, Tipping A, Betts G, Ramachandran I, Navenot JM, Zhang H, Wells DK, Van Winkle E, Kari G, Trivedi T, Holdich T, Pandite L, Amado R, Mackall CL. Antitumor activity associated with prolonged persistence of adoptively transferred NY-ESO-1 (c259)T cells in synovial sarcoma. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(8):944–957. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rapoport AP, Stadtmauer EA, Binder-Scholl GK, Goloubeva O, Vogl DT, Lacey SF, Badros AZ, Garfall A, Weiss B, Finklestein J, Kulikovskaya I, Sinha SK, Kronsberg S, Gupta M, Bond S, Melchiori L, Brewer JE, Bennett AD, Gerry AB, Pumphrey NJ, Williams D, Tayton-Martin HK, Ribeiro L, Holdich T, Yanovich S, Hardy N, Yared J, Kerr N, Philip S, Westphal S, Siegel DL, Levine BL, Jakobsen BK, Kalos M, June CH. NY-ESO-1-specific TCR-engineered T cells mediate sustained antigen-specific antitumor effects in myeloma. Nat Med. 2015;21(8):914–921. doi: 10.1038/nm.3910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas R, Al-Khadairi G, Roelands J, Hendrickx W, Dermime S, Bedognetti D, Decock J. NY-ESO-1 based immunotherapy of cancer: current perspectives. Front Immunol. 2018;9:947. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woloszynska-Read A, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Yu J, Odunsi K, Karpf AR. Intertumor and intratumor NY-ESO-1 expression heterogeneity is associated with promoter-specific and global DNA methylation status in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(11):3283–3290. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ochi T, Fujiwara H, Okamoto S, An J, Nagai K, Shirakata T, Mineno J, Kuzushima K, Shiku H, Yasukawa M. Novel adoptive T-cell immunotherapy using a WT1-specific TCR vector encoding silencers for endogenous TCRs shows marked antileukemia reactivity and safety. Blood. 2011;118(6):1495–1503. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-337089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Provasi E, Genovese P, Lombardo A, Magnani Z, Liu PQ, Reik A, Chu V, Paschon DE, Zhang L, Kuball J, Camisa B, Bondanza A, Casorati G, Ponzoni M, Ciceri F, Bordignon C, Greenberg PD, Holmes MC, Gregory PD, Naldini L, Bonini C. Editing T cell specificity towards leukemia by zinc finger nucleases and lentiviral gene transfer. Nat Med. 2012;18(5):807–815. doi: 10.1038/nm.2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmid DA, Irving MB, Posevitz V, Hebeisen M, Posevitz-Fejfar A, Sarria JC, Gomez-Eerland R, Thome M, Schumacher TN, Romero P, Speiser DE, Zoete V, Michielin O, Rufer N. Evidence for a TCR affinity threshold delimiting maximal CD8 T cell function. J Immunol. 2010;184(9):4936–4946. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Govers C, Sebestyen Z, Roszik J, van Brakel M, Berrevoets C, Szoor A, Panoutsopoulou K, Broertjes M, Van T, Vereb G, Szollosi J, Debets R. TCRs genetically linked to CD28 and CD3epsilon do not mispair with endogenous TCR chains and mediate enhanced T cell persistence and anti-melanoma activity. J Immunol. 2014;193(10):5315–5326. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hinrichs CS, Borman ZA, Cassard L, Gattinoni L, Spolski R, Yu Z, Sanchez-Perez L, Muranski P, Kern SJ, Logun C, Palmer DC, Ji Y, Reger RN, Leonard WJ, Danner RL, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Adoptively transferred effector cells derived from naive rather than central memory CD8+ T cells mediate superior antitumor immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(41):17469–17474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907448106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gattinoni L, Lugli E, Ji Y, Pos Z, Paulos CM, Quigley MF, Almeida JR, Gostick E, Yu Z, Carpenito C. A human memory T cell subset with stem cell-like properties. Nat Med. 2011;17(10):1290. doi: 10.1038/nm.2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klebanoff CA, Scott CD, Leonardi AJ, Yamamoto TN, Cruz AC, Ouyang C, Ramaswamy M, Roychoudhuri R, Ji Y, Eil RL, Sukumar M, Crompton JG, Palmer DC, Borman ZA, Clever D, Thomas SK, Patel S, Yu Z, Muranski P, Liu H, Wang E, Marincola FM, Gros A, Gattinoni L, Rosenberg SA, Siegel RM, Restifo NP. Memory T cell-driven differentiation of naive cells impairs adoptive immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(1):318–334. doi: 10.1172/JCI81217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui G, Staron MM, Gray SM, Ho PC, Amezquita RA, Wu J, Kaech SM. IL-7-induced glycerol transport and TAG synthesis promotes memory CD8+ T cell longevity. Cell. 2015;161(4):750–761. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cieri N, Camisa B, Cocchiarella F, Forcato M, Oliveira G, Provasi E, Bondanza A, Bordignon C, Peccatori J, Ciceri F, Lupo-Stanghellini MT, Mavilio F, Mondino A, Bicciato S, Recchia A, Bonini C. IL-7 and IL-15 instruct the generation of human memory stem T cells from naive precursors. Blood. 2013;121(4):573–584. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-431718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu Y, Zhang M, Ramos CA, Durett A, Liu E, Dakhova O, Liu H, Creighton CJ, Gee AP, Heslop HE, Rooney CM, Savoldo B, Dotti G. Closely related T-memory stem cells correlate with in vivo expansion of CAR.CD19-T cells and are preserved by IL-7 and IL-15. Blood. 2014;123(24):3750–3759. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-552174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kondo T, Imura Y, Chikuma S, Hibino S, Omata-Mise S, Ando M, Akanuma T, Iizuka M, Sakai R, Morita R, Yoshimura A. Generation and application of human induced-stem cell memory T cells for adoptive immunotherapy. Cancer Sci. 2018;109(7):2130–2140. doi: 10.1111/cas.13648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffmann J-M, Schubert M-L, Wang L, Hückelhoven A, Sellner L, Stock S, Schmitt A, Kleist C, Gern U, Loskog A. Differences in expansion potential of naive chimeric antigen receptor T cells from healthy donors and untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia Patients. Front Immunol. 2018;8:1956. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stock S, Hoffmann J-M, Schubert M-L, Wang L, Wang S, Gong W, Neuber B, Gern U, Schmitt A, Müller-Tidow C. Influence of retronectin-mediated T-cell activation on expansion and phenotype of CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Hum Gene Ther. 2018;29(10):1167–1182. doi: 10.1089/hum.2017.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stock S, Ubelhart R, Schubert ML, Fan F, He B, Hoffmann JM, Wang L, Wang S, Gong W, Neuber B, Huckelhoven-Krauss A, Gern U, Christ C, Hexel M, Schmitt A, Schmidt P, Krauss J, Jager D, Muller-Tidow C, Dreger P, Schmitt M, Sellner L. Idelalisib for optimized CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor T cells in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients. Int J Cancer. 2019 doi: 10.1002/ijc.32201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaartinen T, Luostarinen A, Maliniemi P, Keto J, Arvas M, Belt H, Koponen J, Loskog A, Mustjoki S, Porkka K. Low interleukin-2 concentration favors generation of early memory T cells over effector phenotypes during chimeric antigen receptor T-cell expansion. Cytotherapy. 2017;19(6):689–702. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2017.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mercier-Letondal P, Montcuquet N, Sauce D, Certoux JM, Jeanningros S, Ferrand C, Bonyhadi M, Tiberghien P, Robinet E. Alloreactivity of ex vivo-expanded T cells is correlated with expansion and CD4/CD8 ratio. Cytotherapy. 2008;10(3):275–288. doi: 10.1080/14653240801927032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gargett T, Brown MP. Different cytokine and stimulation conditions influence the expansion and immune phenotype of third-generation chimeric antigen receptor T cells specific for tumor antigen GD2. Cytotherapy. 2015;17(4):487–495. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu S, Nukaya I, Enoki T, Chatani E, Kato A, Goto Y, Dan K, Sasaki M, Tomita K, Tanabe M. In vivo persistence of genetically modified T cells generated ex vivo using the fibronectin CH296 stimulation method. Cancer Gene Ther. 2008;15(8):508–516. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2008.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang S, Ji Y, Gattinoni L, Zhang L, Yu Z, Restifo NP, Rosenberg SA, Morgan RA. Modulating the differentiation status of ex vivo-cultured anti-tumor T cells using cytokine cocktails. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62(4):727–736. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1378-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang S, Archer GE, Flores CE, Mitchell DA, Sampson JH. A cytokine cocktail directly modulates the phenotype of DC-enriched anti-tumor T cells to convey potent anti-tumor activities in a murine model. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62(11):1649–1662. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1464-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu XJ, Song DG, Poussin M, Ye Q, Sharma P, Rodríguez-García A, Tang Y-M, Powell DJ. Multiparameter comparative analysis reveals differential impacts of various cytokines on CART cell phenotype and function ex vivo and in vivo. Oncotarget. 2016;7(50):82354–82368. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kayser S, Bobeta C, Feucht J, Witte KE, Scheu A, Bulow HJ, Joachim S, Stevanovic S, Schumm M, Rittig SM, Lang P, Rocken M, Handgretinger R, Feuchtinger T. Rapid generation of NY-ESO-1-specific CD4(+) THELPER1 cells for adoptive T-cell therapy. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4(5):e1002723. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2014.1002723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakuishi K, Apetoh L, Sullivan JM, Blazar BR, Kuchroo VK, Anderson AC. Targeting Tim-3 and PD-1 pathways to reverse T cell exhaustion and restore anti-tumor immunity. J Exp Med. 2010;207(10):2187–2194. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fourcade J, Sun Z, Benallaoua M, Guillaume P, Luescher IF, Sander C, Kirkwood JM, Kuchroo V, Zarour HM. Upregulation of Tim-3 and PD-1 expression is associated with tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cell dysfunction in melanoma patients. J Exp Med. 2010;207(10):2175–2186. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang ZZ, Grote DM, Ziesmer SC, Niki T, Hirashima M, Novak AJ, Witzig TE, Ansell SM. IL-12 upregulates TIM-3 expression and induces T cell exhaustion in patients with follicular B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(4):1271–1282. doi: 10.1172/JCI59806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou Q, Munger ME, Veenstra RG, Weigel BJ, Hirashima M, Munn DH, Murphy WJ, Azuma M, Anderson AC, Kuchroo VK, Blazar BR. Coexpression of Tim-3 and PD-1 identifies a CD8+ T-cell exhaustion phenotype in mice with disseminated acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2011;117(17):4501–4510. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-310425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mikucki ME, Skitzki JJ, Frelinger JG, Odunsi K, Gajewski TF, Luster AD, Evans SS. Unlocking tumor vascular barriers with CXCR42: implications for cancer immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5(5):e1116675. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1116675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mikucki ME, Fisher DT, Matsuzaki J, Skitzki JJ, Gaulin NB, Muhitch JB, Ku AW, Frelinger JG, Odunsi K, Gajewski TF, Luster AD, Evans SS. Non-redundant requirement for CXCR43 signalling during tumoricidal T-cell trafficking across tumour vascular checkpoints. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7458. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chheda ZS, Sharma RK, Jala VR, Luster AD, Haribabu B. Chemoattractant receptors BLT1 and CXCR44 regulate antitumor immunity by facilitating CD8+ T cell migration into tumors. J Immunol. 2016;197(5):2016–2026. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schuster K, Gadiot J, Andreesen R, Mackensen A, Gajewski TF, Blank C. Homeostatic proliferation of naive CD8+ T cells depends on CD62L/L-selectin-mediated homing to peripheral LN. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(11):2981–2990. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gattinoni L, Klebanoff CA, Restifo NP. Paths to stemness: building the ultimate antitumour T cell. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(10):671–684. doi: 10.1038/nrc3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farber DL, Yudanin NA, Restifo NP. Human memory T cells: generation, compartmentalization and homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(1):24–35. doi: 10.1038/nri3567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.