Abstract

Systemic immunotherapy with PD-1 inhibitors is established in the treatment of metastatic melanoma. However, up to 60% of patients do not show long-term benefit from a PD-1 inhibitor monotherapy. Intralesional treatments with immunomodulatory agents such as the oncolytic herpes virus Talimogene Laherparepvec and interleukin-2 (IL-2) have been successfully used in patients with injectable metastases. Combination therapy of systemic and local immunotherapies is a promising treatment option in melanoma patients. We describe a case series of nine patients with metastatic melanoma and injectable lesions who developed progressive disease under a PD-1 inhibitor monotherapy. At the time of progressive disease, patients received intratumoral IL-2 treatment in addition to PD-1 inhibitor therapy. Three patients showed complete, three patients partial response and three patients progressive disease upon this combination therapy. IHC stainings were performed from metastases available at baseline (start of PD-1 inhibitor) and under combination therapy with IL-2. IHC results revealed a significant increase of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and a higher PD-1 expression in the inflammatory infiltrate of the tumor microenvironment in metastases from patients with subsequent treatment response. All responding patients further showed a profound increase of the absolute eosinophil count (AEC) in the blood. Our case series supports the concept that patients with initial resistance to PD-1 inhibitor therapy and injectable lesions can profit from an additional intralesional IL-2 therapy which was well tolerated. Response to this therapy is accompanied by increase in AEC and a strong T cell-based inflammatory infiltrate.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00262-019-02377-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Metastatic melanoma, Interleukin-2, Intralesional, Combination therapy, PD-1 inhibitor

Introduction

In the treatment of advanced metastatic melanoma systemic immunotherapies like PD-1 inhibitors are widely distributed and established [2]. These drugs show impressive response rates and long-term benefit for up to 40% of patients [2]. However, a larger proportion of patients (accounting for up to 60%) show a primary insufficient response or primary therapeutic resistance to systemic PD-1 inhibitors [3]. Within this group of non-responders, a subset presents with locoregionary or distant cutaneous and subcutaneous metastases and is therefore eligible for additional intralesional treatment options. These include, among others, intratumoral application of an oncolytic herpes simplex virus [Talimogene Laherparepvec (TVEC)] as well as Interleukin-2 (IL-2) [4, 5]. The combination therapy of systemic and local immuno-oncological agents has shown heterogeneous response rates. While the combination of intralesional TVEC and a systemic PD-1 inhibitor lead to a high overall response rate of 62% in a phase Ib clinical trial [6], a recently published phase II study using combined treatment with ipilimumab and intratumoral IL-2 in pretreated patients showed no significantly higher response rate compared to ipilimumab treatment alone [7]. In this case series we describe clinical response rates to an additional intratumoral IL-2 treatment in patients with primary therapeutic resistance to systemic monotherapy with PD-1 inhibitors.

Materials and methods

Patients

All patients had histologically confirmed stage IV or unresectable stage III melanoma. The selection of patients was based on progressive disease (PD) under PD-1 inhibitor monotherapy and the existence of at least one injectable metastasis. Tumor assessments were done clinically and using ultrasound at every patients’ visit and radiologically every 3 months as per institute‘s standards according to RECIST version 1.1 [8]. iRECIST (immune Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) evaluation was not applicable since imaging intervals according to local standard of care differed from intervals required for iRECIST [9].

Routine laboratory examinations were performed at the start of PD-1 inhibitor and combination therapy and subsequently at every patients’ visit.

Interleukin-2 treatment

At the day of intralesional treatment IL-2 (PROLEUKIN® S, Novartis Pharma, Basel, Switzerland) was freshly prepared at the central hospital pharmacy of the Medical Center, University of Freiburg. In brief, IL-2 was diluted in 5% glucose solution to a final concentration of 3 MIU IL-2 per ml under sterile conditions. Depending on the size and number of metastases, a maximum of 9 MIU (3 ml) per patient was applied in one treatment session.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Serial sections were prepared from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded skin biopsies. Standard hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed for diagnostic purposes. For IHC staining sections were deparaffinized and subjected to heat-induced antigen retrieval using EDTA pH9 or citrate pH6 retrieval buffer, respectively (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA 95051, USA). For PD-L1, staining sections were incubated with a rabbit monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; clone: E1L3N; dilution of 1:100) and for PD-1 staining with a polyclonal goat antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN 55413, USA; dilution 1:100). Incubation was performed at 4 °C overnight, respectively. Additional Ab for IHC included: anti-S100 Ab (Agilent; dilution 1:1000), anti-CD68 Ab (Agilent; clone: PGM1, dilution 1:50), anti-CD4 Ab (Zytomed, 14163 Berlin, Germany; clone: SP35, undiluted), anti-HMB45 (Agilent; clone: HMB-45, dilution 1:10) and anti-CD8 Ab (Agilent; clone: C8/144B, dilution 1:50). Sections incubated with secondary antibody only served as staining controls. Visualization was performed using the Dako REAL detection system, Alkaline Phosphatase/RED, Rabbit/Mouse (Agilent). Photographs of stainings were taken using a Zeiss microscope (Axioscope) and were visualized with the program AxioVision (Zeiss, 07745 Jena, Germany; SE64 release 4.9).

Histology score (H-Score) was calculated for IHC markers PD-1 and PD-L1 as a semiquantitative approach using the following formula: H-Score = [1 × (% cells 1 +) + 2 × (% cells 2 +) + 3 × (% cells 3 +)]. Membrane staining intensity was defined as 0 = no staining, 1 + = weak staining, 2 + = moderate staining, or 3 + = strong staining [10]. Absolute cell numbers per mm2 of CD4+, CD8+ and CD68+ cells were measured using the imaging software QuPath [11]. Average cell numbers of at least three different tumor sites (magnification 10 ×) were calculated using the positive cell detection and counting tool.

Vector graphics and statistical analysis were generated using GraphPad Prism version 5.03 for Windows (Graphpad Software Inc, San Diego, CA 92108, USA; http://www.graphpad.com). The two-tailed, non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was used to compare groups. Statistical significance was noted as p < 0.05.

Results

We report results form a cohort of nine patients with unresectable metastatic melanoma who displayed at least one injectable cutaneous or subcutaneous metastasis and received first-line systemic therapy with a PD-1 inhibitor. All patients have shown PD under PD-1 inhibitor treatment alone and subsequently underwent an additional intralesional IL-2 treatment of injectable (sub-)cutaneous metastases as an individual treatment decision. Biopsies (n = 22) of skin metastases from all nine patients were available from baseline, i.e., before start of systemic immunotherapy with PD-1 inhibitors and during combination therapy with IL-2 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Patients (median age 66 years, range 52–85; female:male 4:5) showed advanced tumor disease [7 patients stage IV, 2 patients unresectable stage III (according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system 2017, [12])]. For detailed patients’ characteristics see Table 1. Best response to PD-1 inhibitor treatment alone was PD in all patients except for Patient 4 who temporally showed a stable disease (SD). Patient 2 had a prior radiotherapy of skin metastases on the chest wall which showed no response. Patient 5 had symptomatic disease due to multiple brain metastases that were treated twice with stereotactic radiotherapy. Skin metastases were located on the trunk, the upper and lower extremities and one patient displayed metastasis on the scalp. The median number of skin metastases per patient prior to start of IL-2 therapy was 8 (range 2–100) and maximum diameters per metastasis ranged from 4 to 320 mm. Patients received 3–9 MIU IL-2 per treatment depending on size and number of injected lesions. The median cumulative dose administered was 42 MIU IL-2 and the median number of intralesional IL-2 applications was 7 (range 3–21). Combination therapy was generally well tolerated. Most frequent side effects were low grade and transient (chills, aching limbs and fever) (Table 1) and were well controlled with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). One patient suffered from peripheral polyneuropathy (PNP) with dysesthesia [Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 4.0 [13] grade 3] as well as a reversible neutropenia (CTCAE grade 2) which lead to a temporary discontinuation of IL-2 treatment.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

| P | A | S | Cancer stage (AJCC 2017)/TNM | ECOG | Best response to | AEs | IL-2 therapy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD-1i monotherapy | PD-1i + IL-2 | |||||||||

| Cutaneous | Visceral | |||||||||

| Injected | Non-injected | |||||||||

| 1 | 69 | F | IV/T3a N1c M1c (0) | 0 | PD | CR | CR | NAa | Chills, aching limbs | Terminatedc |

| 2 | 70 | M | IV/T4a N3c M1c (1) | 0 | PD | CR | CR | CR | None | Terminatedc |

| 3 | 75 | M | IIID/T3b N3c M0 (0) | 1 | PD | PR | PD | NAb | Chills, eczema | Terminatedd |

| 4 | 60 | F | IV/T3b N1c M1a (0) | 0 | SD | CR | CR | CR | PNP, neutropenia, muscle cramps | Terminatedc |

| 5 | 65 | M | IV/T4b N3b M1c (0) | 0 | PD | CR | CR | PD | None | Terminatedc |

| 6 | 52 | F | IV/T4b N2c M1c (1) | 1 | PD | PR | PR | PR | Nausea, erysipelas | Ongoinge |

| 7 | 61 | M | IIIB/T2a N1c M0 (0) | 0 | PD | PR | PR | NAb | Fever, asthma | Ongoinge |

| 8 | 66 | M | IV/T3b N3c M1c (0) | 0 | PD | PR | PD | PD | Fever, chills, vomiting | Terminatedd |

| 9 | 85 | F | IV/T4b N1c M1c (0) | 0 | PD | CR | CR | PR | Fever | Terminatedc |

P patient number, A age, S sex, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, (0) normal (LDH), (1) elevated (LDH), AJCC 2017 American Joint Committee on Cancer, Melanoma of the Skin Staging, 8th edition, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status, CR complete response, PR partial response, PD progressive disease, SD stable disease, NA not applicable, AEs adverse events, PNP peripheral neuropathy, IL-2 interleukin-2, PD-1i PD-1 inhibitor

aStatus post single successfully irradiated bone metastasis

bNo distant metastases present

cTerminated due to CR of cutaneous metastases

dTerminated due to PD of cutaneous and/or visceral metastases

eStatus as of April 2019

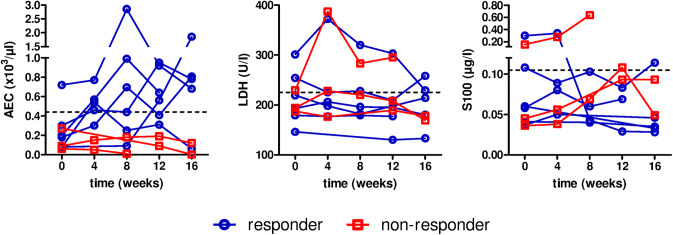

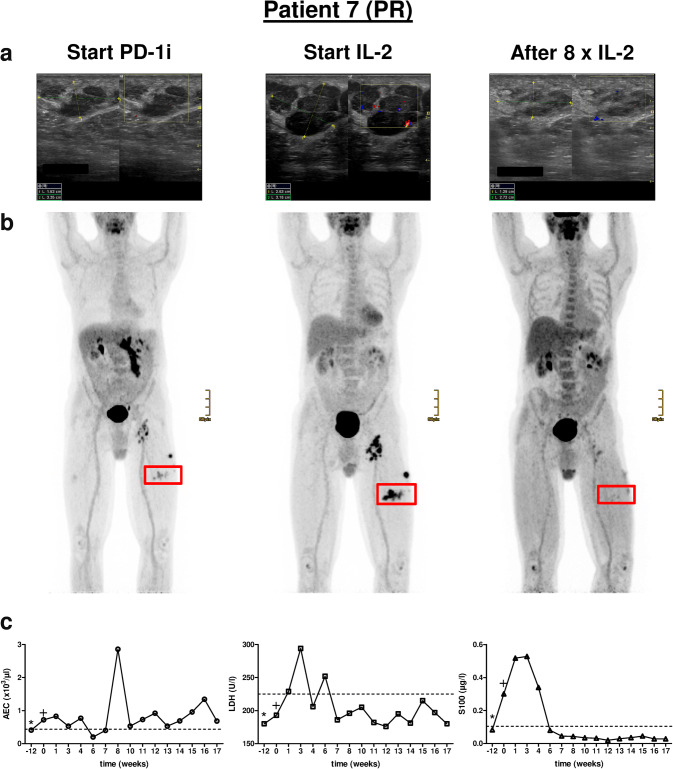

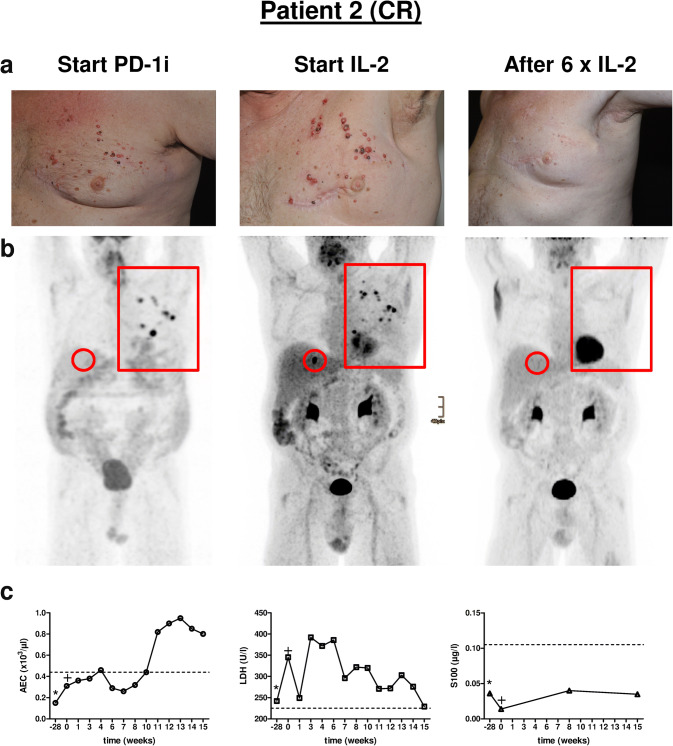

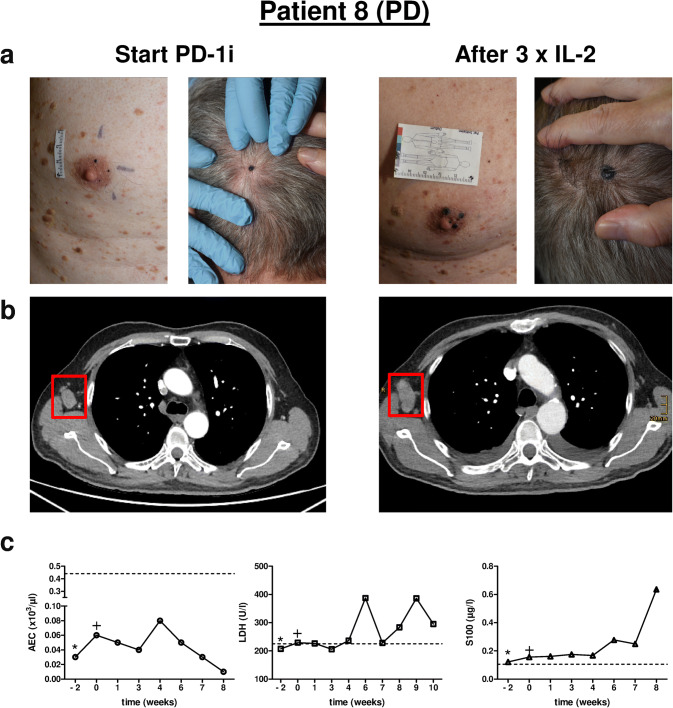

All patients showing ongoing cutaneous and/or visceral tumor reduction [complete response (CR) and partial response (PR)] under combination therapy were considered as responders. Non-responders were defined as having SD or PD. All responders displayed a marked increase in absolute eosinophil count (AEC) in the blood during combination therapy whereas in non-responding patients no eosinophilia or even a reduction of the AEC was evident (Figs. 1, 2c, 3c, 4c and Supplementary Fig. 2c). Serological markers LDH and S100-protein (S100) could not differentiate between responders and non-responders except for one patient (Patient 7) whose clinical response was accompanied by a decrease in LDH and S100 levels after initiation of combination therapy (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 1.

Blood biomarkers of treated patients. Biomarkers were taken during combination therapy with PD-1 inhibitor and IL-2. Time point 0 marks the start of combination therapy. Patients responding to combination therapy are displayed in blue, non-responding patients are shown in red. AEC absolute eosinophil count, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, MIU million international units. Dashed line marks upper limit normal (ULN)

Fig. 2.

Clinical course of Patient 7. a Representative ultrasound images of a cutaneous metastasis of the left upper leg at three different time points, i.e., start of PD-1i, start of IL-2 treatment and after eight injections of IL-2. b PET–CT scans of the according time points showing locoregionary metastases of the left upper leg and groin. Red rectangle marks cutaneous metastasis that was monitored by ultrasound in a. c Individual monitoring of blood biomarkers AEC, LDH and S100 before (− 12), at the start (0) and during combination therapy. *, start of PD-1i monotherapy; +, start of additional IL-2 treatment. PD-1i PD-1 inhibitor, AEC absolute eosinophil count, LDH lactate dehydrogenase. Dashed line in c marks upper limit normal (ULN), PR partial response

Fig. 3.

Clinical course of Patient 2. a Representative clinical pictures of cutaneous metastases of the left chest wall at three different time points, i.e., start of PD-1i, start of IL-2 treatment and after six injections of IL-2. b PET–CT scans of the according time points showing locoregionary metastases of the left chest wall (red rectangle) and a single liver metastasis (red circle). c Individual monitoring of blood biomarkers AEC, LDH and S100 before (− 28), at the start (0) and during combination therapy with IL-2. *, start PD-1i monotherapy; +, start additional IL-2 treatment. PD-1i PD-1 inhibitor, AEC absolute eosinophil count, LDH lactate dehydrogenase. Dashed line in c marks upper limit normal (ULN). CR complete response

Fig. 4.

Clinical course of Patient 8. a Representative clinical pictures of cutaneous metastases of the head and right chest wall at two different time points, i.e., start of PD-1i and after three injections of IL-2. b Chest CT scans (transverse section) of the according time points showing a lymph node metastasis of the right axilla (red rectangle). c Individual monitoring of blood biomarkers AEC, LDH and S100 before (− 2), at the start (0) and during combination therapy with IL-2. *, start PD-1i monotherapy; +, start additional IL-2 treatment. PD-1i PD-1 inhibitor, AEC absolute eosinophil count, LDH lactate dehydrogenase. Dashed line in c marks upper limit normal (ULN). PD progressive disease

All patients initially showed at least a PR of injected lesions (Table 1). In five patients a CR of cutaneous metastases including non-injected lesions was achieved (Table 1). Patients 6 and 7 are still under combination therapy with an ongoing PR of cutaneous metastases. Patient 7 had a marked response of his cutaneous metastases as shown by reduction in size and hypoechogenic areas, documented by ultrasound (Fig. 2a). Patient 5, although developing a CR of his cutaneous lesions developed new intestinal metastases during the course of treatment. Patients 3 and 8 have progressed under therapy and were subjected to different therapy regimens (Table 1). In particular, Patient 8 developed multiple new and growing skin and lymph node metastases (Fig. 4a, b). Interestingly, besides local tumor control of cutaneous lesions four patients displayed a CR (2/4) or PR (2/4) of distant metastases as exemplified for Patients 2 and 9 (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 2a).

Figure 5a shows representative IHC images of metastases from three patients with different clinical response patterns (CR, PR and PD) to combination therapy. Patients 7 (PR) and 2 (CR) showed a marked increase of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating T cells whereas Patient 8 (PD) showed only a moderate CD8+ infiltrate at baseline and under combination therapy (Fig. 5a). In addition, one metastasis available from Patient 7 under combination therapy revealed a dramatic increase in PD-L1 expression of tumor cells and PD-1-positive tumor-infiltrating cells (Fig. 5a). As examined by IHC staining of IL-2 injected metastases, for the entire cohort 86% (6/7) and 71% (5/7) of biopsies from responding patients revealed a significant increase of total tumor-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cell numbers, respectively. In contrast, the majority of metastases from non-responding patients [75% (3/4)] displayed a reduction or no significant change of total CD4+ and CD8+ T cell numbers (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 3a). Interestingly, higher baseline numbers for CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were associated with a worse treatment response (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 3b). PD-1 expression by cells of the inflammatory infiltrate significantly increased under therapy in the responding group, whereas biopsies from non-responders showed an inverse pattern [86% (6/7) vs. 0% (0/3)] (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 3a). In addition, PD-L1 expression by tumor cells was generally low and changes in PD-L1 expression did not show a clear trend between responders and non-responders. However, two biopsies from responding patients showed a dramatic increase of PD-L1 expression on melanoma cells under combination therapy (Fig. 5b). Finally, changes in the infiltration of CD68+ antigen presenting cells (APCs) like tissue macrophages showed no clear tendency favoring one of the two groups (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Of note, in both tumor sections from the responder group that showed no increase of total CD8+ and CD68+ cell numbers, a complete pathological response was evident (i.e., vital tumor tissue was absent).

Fig. 5.

Immunohistochemistry stainings of melanoma metastases. a Representative stainings of melanoma metastases of three patients with different clinical response patterns to combination therapy. Biopsies were taken before start of PD-1 inhibitor (baseline) and under combination therapy with IL-2 (under IL-2). Scale bar indicates 100 µm distance. CR complete response, PR partial response, PD progressive disease. b Graphical summary displaying the characterization of the inflammatory tumor infiltrate showing absolute numbers per mm2 of CD4-, CD8- and CD68-positive cells in all excised biopsies (n = 22 taken biopsies). Staining intensities of PD-1 and PD-L1 were quantified using the H-Score. Patients responding to combination therapy are displayed in blue, non-responding patients are shown in red. H-Score histology score (for detailed calculation see “Materials and methods” section)

In summary, within our cohort treatment response was accompanied by an increase in AEC in the blood and elevated total numbers of tumor-infiltrating T cells expressing PD-1.

Discussion

Applying local or intralesional immunological agents to accessible metastases in melanoma patients in combination with a systemic backbone immunotherapy is an emerging field of basic and clinical research and shows promising results [6, 14]. This is further emphasized by an ongoing phase Ib trial investigating the effect of the intralesional toll-like receptor 9 agonist CMP-001 in combination with pembrolizumab in patients refractory to PD-1 inhibition alone [14]. In this latter study, the objective response rate across all dose cohorts was 23% and regression of non-injected tumors was observed in cutaneous, nodal, hepatic, and splenic metastases [14].

Higher response rates of therapeutic systemic and intralesional combination strategies are usually not accompanied by elevated adverse event rates as shown for the combination of TVEC or CMP-001 with a PD-1 inhibitor [6, 14]. Accordingly, in our treatment approach, the combination therapy of PD-1 inhibitor and intralesional IL-2 was generally well tolerated and in only one patient, therapy had to be temporarily discontinued due to severe adverse events. This makes these treatment options highly attractive for patients and physicians.

Treatment of melanoma patients with IL-2 has been long established and was the first effective immunotherapy in cancer [15–19]. However, high dose systemic IL-2 treatment alone achieved only a moderate overall response rate of 16–18% in metastatic melanoma [15, 20] and side effects are common, may be severe and can be life threatening [15, 18, 20]. Intralesional IL-2 therapy has been proven to be an effective therapy with complete local response rates of 60–70% and low rate of side effects [5, 19]. In patients with locoregional metastases alone or without visceral metastases response rates were even higher [5]. However, patients with greater size of especially subcutaneous lesions seem to show lower response rates to intratumoral IL-2 treatment [5, 21]. Meanwhile, a new therapeutic generation using an IL-2 backbone has been developed [22]. These products are recombinant antibody-cytokine fusion proteins consisting of the cytokines IL-2 and/or TNF fused to the monoclonal antibody L19, which is specific to the alternatively spliced extra-domain B of fibronectin, a marker of tumor angiogenesis [23]. These immunocytokines (‘armed antibodies’) deliver the immunomodulatory payload to the site of disease and have been thoroughly investigated in vitro and in vivo and in different forms of application (systemic vs. local/intralesional) [23–28]. Results of a phase II trial with intralesional treatment of L19-IL2/L19-TNF in patients with unresectable stage IIIc/IVM1a melanoma are available showing an objective response rate of 55% of treated lesions and the disease control rate of treated lesions was 80% [29].

In our study all patients (9/9) initially showed at least a PR of the IL-2 injected lesions. 56% (5/9) of patients even developed a CR of injected and non-injected cutaneous lesions in the course of combination therapy. However, one of these patients (Patient 5) developed new distant metastases during the follow-up and was subjected to a different systemic therapy regime. Two patients (22%) are still under combination therapy and have displayed a PR of all their cutaneous metastases so far. In our study, four out of nine patients (44%) with distant metastases showed a partial (2/4) or complete (2/4) response of their distant non-injected visceral metastases which highlights a beneficial systemic effect by combining local and systemic immunotherapies in this group of patients. This abscopal effect of IL-2 on non-injected and visceral metastases has already been reported for intralesional IL-2 treatment alone [5]. However, in the study of Weide et al. the presence of visceral metastases that could not be injected was also associated with a low local response rate of the injected metastases (CR: 16.7% of metastases; PR: 1.2% of metastases) [5]. Interestingly, the systemic (abscopal) anticancer activity on non-injected cutaneous and visceral lesions of intralesional L19-IL2/L19-TNF treatment [29] exceeded the reported abscopal effect of conventional intralesional IL-2 therapy [5, 21]. On the basis of this observation these L19-IL-2-based intralesional treatment approaches are probably more promising combination partners for systemic PD-1 therapy than conventional IL-2 preparations.

We found that response to combination therapy was accompanied by increased AEC in the blood, increase of total CD4+ and CD8+ T cell numbers in the tumor infiltrate and elevated PD-1 expression of infiltrating inflammatory cells. Comparable immunological effects of IL-2-injected melanoma metastases have been reported by Radny et al. for conventional IL-2 treatment [19] and by Danielli et al. for the immunocytokine treatment with L19-IL2/L19-IFN [29]. Increase of CD8+ T cells and PD-1 expression in the tumor microenvironment was also a hallmark of treatment response in studies combining intralesional TVEC or CMP-001 with a PD-1 inhibitor backbone therapy [6, 14] or under sequential CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade [30]. Higher baseline numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were associated with a poorer treatment response in our cohort. This is in contrast to previous findings that either showed response to systemic and intralesional combination therapy appeared independent of baseline CD8+ infiltration [6], or, higher CD8+ T cell numbers in tumor biopsies predicted better response to PD-1 inhibitor monotherapy [31]. Nonetheless, proliferation of intratumoral CD8+ T cells correlated with reduction in tumor size [31] which is in line with our findings.

On this basis, and as shown recently by others [32, 33], it seems that dynamic changes in number and composition of infiltrating T-cell clusters better predict response to treatment rather than baseline numbers of infiltrating T cells. Certain exhausted CD8+ T cells expressing the immunosuppressive Adenosine triphosphate ecto-nucleotidase CD39 have been shown to exhibit impaired production of IL-2, interferon-γ, Tumor necrosis factor and high expression of co-inhibitory receptors, which is associated with an unfavorable treatment response to immunotherapy of melanoma [32, 33]. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that intralesional IL-2 treatment of melanoma metastases might change the effector T-cell states within the tumor microenvironment from exhausted into tumor killing, therefore leading to better treatment response.

All responding patients in our cohort showed a marked increase of the AEC shortly after the initiation of IL-2 therapy whereas non-responding patients lacked this effect. Association of increased AEC and treatment response to immunotherapies like Ipilimumab have been shown in the past [34]. Thus, the link between response and peripheral eosinophilia underscores the systemic and valuable effect of adding local IL-2 to a systemic PD-1 antibody backbone.

Ribas et al. reported elevated PD-L1 protein expression on melanoma cells under combination therapy with TVEC and PD-1 inhibitor [6]. PD-L1 expression was generally weak in our cohort and did not show a clear tendency concerning treatment response. This could be due to the low number of patients and the fact that, in general, up to 25% of patients present with PD-L1 negative tumors [35].

It is still a matter of debate how IL-2 exactly influences the tumor microenvironment mechanistically. In a mouse tumor model with spontaneously arising insulinomas autocrine IL-2 in the tumor environment has been shown to promote the expansion of high-affinity CD8+ T cells with increased tumor eradication ability which was further promoted by the presence of CD4+ T cells [36]. However, systemic IL-2 has been shown to promote the expansion of regulatory T cells which may aggravate immunosuppression and lead to limited clinical efficacy [37, 38].

Due to the small number of patients there are limitations of this retrospective, uncontrolled case series. Most of the patients presented with a low ECOG status, rather low tumor burden and only one patient with brain metastasis was included which may influence the good outcome of the majority of patients. There was no control group of patients who did not receive additional local IL-2 treatment and continued PD-1 inhibitor alone, or, who had their systemic therapy changed. Since there were no intermediate biopsies available under PD-1 inhibitor therapy alone, potential impact of PD-1 inhibitor treatment on the influx of T cells into the tumor sites could not be evaluated in this study. However, since most of the patients showed a significant benefit from an additional local IL-2 treatment after failure of systemic immunotherapy alone, we consider that this case series supports the concept of combination immunotherapy for this particular group of patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion our case series supports the concept that patients showing primary resistance to and progressive disease under PD-1 inhibitor monotherapy can benefit from an additional intralesional IL-2 therapy. Recently, the successful combination of systemic immune checkpoint inhibition and intralesional IL-2 has been demonstrated in two melanoma patients underlining the potential benefit of this combination treatment [39]. To note, these patients received a PD-1 inhibitor and intralesional IL-2 as a first-line regimen making it difficult to discriminate the therapeutic effect of either component [39]. In contrast to upfront combination strategies, our concept of initiating additional intralesional therapy only in cases with therapeutic resistance might prevent patients from over-treatment and potential additional side effects.

Our observation also fits with the concept of ‘cold tumors’ with limited or absent immune cell infiltration not responding to checkpoint inhibitors that can be transformed into ‘hot tumors’, e.g., by intratumoral injection of immunomodulatory drugs like IL-2 leading to an influx of tumor-killing T cells and finally treatment response [40, 41]. Further large-scale prospective and controlled trials are needed to address this issue more precisely.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kaethe Thoma for excellent technical assistance, Mareike Maler for scientific advice and Gillian Marsden for language editing.

Abbreviations

- AEC

Absolute eosinophil count

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- CR

Complete response

- CT

Computed tomography

- CTCAE

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status

- H-Score

Histology score

- IL-2

Interleukin-2

- iRECIST

Immune Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- NSAIDs

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- PD

Progressive disease

- PD-1i

Programmed death 1 receptor inhibitor

- PET

Positron-emission tomography

- PR

Partial response

- S100

S100-protein

- SD

Stable disease

- TVEC

Talimogene Laherparepvec

- ULN

Upper limit normal

Author contributions

DR-S helped to develop the concept, treated patients, designed experiments, performed experiments, analyzed the data and wrote main parts of the manuscript. SL treated patients and critically reviewed the manuscript and contributed to the final version. DvB has critically reviewed the manuscript and contributed to the final version. FM developed the overall concept, supervised the experiments, discussed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

David Rafei-Shamsabadi was supported by the clinician scientists program Excellent Clinician Scientists in Freiburg—Education for Leadership (EXCEL at the Medical Center—University of Freiburg, Faculty of Medicine, University of Freiburg, Germany), funded by the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Frank Meiss received honoraria for talks from BMS (Bristol-Myers Squibb), Novartis, Pierre Fabre and was participating in advisory boards of BMS, Novartis, Pierre Fabre and Roche. All other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval and ethical standards

This study was approved by the local ethics committee of the University of Freiburg (approval vote: 478/18). Guidelines from the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975 were followed.

Informed consent

All patients received detailed information about risks, benefits and possible side effects of combination therapy with PD-1 inhibitor and interleukin-2. All patients gave written informed consent to this individual treatment decision. Furthermore, all patients gave written informed consent to the use of their tumor specimens and clinical data for research and publication. This included the use of immunohistochemical staining of tumor biopsies, radiologic (CT and PET–CT scans), ultrasound as well as clinical images.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rafei-Shamsabadi D, von Bubnoff D, Meiss F. Kombinationstherapie aus systemischer Checkpoint-Blockade und lokaler Interleukin-2-Injektion bei primärer Therapieresistenz. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:27. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshall HT, Djamgoz MBA. Immuno-oncology: emerging targets and combination therapies. Front Oncol. 2018;8:315. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, et al. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:134–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andtbacka RHI, Kaufman HL, Collichio F, et al. Talimogene laherparepvec improves durable response rate in patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2780–2788. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weide B, Derhovanessian E, Pflugfelder A, et al. High response rate after intratumoral treatment with interleukin-2. Cancer. 2010;116:4139–4146. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ribas A, Dummer R, Puzanov I, et al. Oncolytic virotherapy promotes intratumoral T cell infiltration and improves anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;170:1109–1119.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weide B, Martens A, Wistuba-Hamprecht K, et al. Combined treatment with ipilimumab and intratumoral interleukin-2 in pretreated patients with stage IV melanoma—safety and efficacy in a phase II study. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:441–449. doi: 10.1007/s00262-016-1944-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seymour L, Bogaerts J, Perrone A, et al. iRECIST: guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e143–e152. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30074-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, Bunn PA, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor in non-small-cell lung carcinomas: correlation between gene copy number and protein expression and impact on prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3798–3807. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bankhead P, Loughrey MB, Fernández JA, et al. QuPath: open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:16878. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17204-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma staging: evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer Eighth Edition Cancer Staging Manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:472–492. doi: 10.3322/caac.21409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CTCAE Files. https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/About.html. Accessed 22 Apr 2019

- 14.Milhem M, Gonzales R, Medina T, et al. Intratumoral toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) agonist, CMP-001, in combination with pembrolizumab can reverse resistance to PD-1 inhibition in a phase Ib trial in subjects with advanced melanoma [abstract] Cancer Res. 2018;78:CT144. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2018-CT144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atkins MB, Lotze MT, Dutcher JP, et al. High-dose recombinant interleukin 2 therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: analysis of 270 patients treated between 1985 and 1993. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2105. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang T, Zhou C, Ren S. Role of IL-2 in cancer immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2016 doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1163462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg SA. IL-2: the first effective immunotherapy for human cancer. J Immunol. 2014;192:5451–5458. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1490019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeiser R, Schnitzler M, Andrlová H, Meiss TH, Robert F (2012) Immunotherapy for malignant melanoma. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. http://www.eurekaselect.com/97724/article. Accessed 9 Nov 2018 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Radny P, Caroli UM, Bauer J, et al. Phase II trial of intralesional therapy with interleukin-2 in soft-tissue melanoma metastases. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1620–1626. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davar D, Ding F, Saul M, et al. High-dose interleukin-2 (HD IL-2) for advanced melanoma: a single center experience from the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute. J Immunother Cancer. 2017 doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weide B, Eigentler TK, Elia G, et al. Limited efficacy of intratumoral IL-2 applied to large melanoma metastases. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63:1231–1232. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1584-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danielli R, Patuzzo R, Ruffini PA, et al. Armed antibodies for cancer treatment: a promising tool in a changing era. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2015;64:113–121. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1621-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carnemolla B, Borsi L, Balza E, et al. Enhancement of the antitumor properties of interleukin-2 by its targeted delivery to the tumor blood vessel extracellular matrix. Blood. 2002;99:1659–1665. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.5.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weide B, Neri D, Elia G. Intralesional treatment of metastatic melanoma: a review of therapeutic options. Cancer Immunol Immunother CII. 2017;66:647–656. doi: 10.1007/s00262-016-1952-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weide B, Eigentler TK, Pflugfelder A, et al. Intralesional treatment of stage III metastatic melanoma patients with L19-IL2 results in sustained clinical and systemic immunologic responses. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014 doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eigentler TK, Weide B, de Braud F, et al. A dose-escalation and signal-generating study of the immunocytokine L19-IL2 in combination with dacarbazine for the therapy of patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pretto F, Elia G, Castioni N, Neri D. Preclinical evaluation of IL2-based immunocytokines supports their use in combination with dacarbazine, paclitaxel and TNF-based immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63:901–910. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1562-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwager K, Hemmerle T, Aebischer D, Neri D. The immunocytokine L19-IL2 eradicates cancer when used in combination with CTLA-4 blockade or with L19-TNF. J Investig Dermatol. 2013;133:751–758. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danielli R, Patuzzo R, Di Giacomo AM, et al. Intralesional administration of L19-IL2/L19-TNF in stage III or stage IVM1a melanoma patients: results of a phase II study. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2015;64:999–1009. doi: 10.1007/s00262-015-1704-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen P-L, Roh W, Reuben A, et al. Analysis of immune signatures in longitudinal tumor samples yields insight into biomarkers of response and mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:827–837. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH, et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature. 2014;515:568–571. doi: 10.1038/nature13954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Canale FP, Ramello MC, Núñez N, et al. CD39 expression defines cell exhaustion in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells. Cancer Res. 2018;78:115–128. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sade-Feldman M, Yizhak K, Bjorgaard SL, et al. Defining T cell states associated with response to checkpoint immunotherapy in melanoma. Cell. 2018;175:998–1013.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Umansky V, Utikal J, Gebhardt C. Predictive immune markers in advanced melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Oncoimmunology. 2016 doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1158901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Daud AI, Wolchok JD, Robert C, et al. Programmed death-ligand 1 expression and response to the anti-programmed death 1 antibody pembrolizumab in melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:4102–4109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bos R, Marquardt KL, Cheung J, Sherman LA. Functional differences between low- and high-affinity CD8+ T cells in the tumor environment. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:1239–1247. doi: 10.4161/onci.21285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beyer M. Interleukin-2 treatment of tumor patients can expand regulatory T cells. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:1181–1182. doi: 10.4161/onci.20639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mooradian MJ, Reuben A, Prieto PA, et al. A phase II study of combined therapy with a BRAF inhibitor (vemurafenib) and interleukin-2 (aldesleukin) in patients with metastatic melanoma. OncoImmunology. 2018;7:e1423172. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1423172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langan EA, Kümpers C, Graetz V, et al. Intralesional interleukin-2: a novel option to maximize response to systemic immune checkpoint therapy in loco-regional metastatic melanoma. Dermatol Ther. 2019 doi: 10.1111/dth.12901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haanen JBAG. Converting cold into hot tumors by combining immunotherapies. Cell. 2017;170:1055–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker PR. Let there be oxygen and T cells. J Clin Investig. 2018;128:4761–4763. doi: 10.1172/JCI124305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.