Abstract

Background

The tumor-expressed CD73 ectonucleotidase generates immune tolerance and promotes invasiveness via adenosine production from degradation of AMP. While anti-CD73 blockade treatment is a promising tool in cancer immunotherapy, a characterization of CD73 expression in human hepatobiliopancreatic system is lacking.

Patients and methods

CD73 expression was investigated by immunohistochemistry in a variety of non-neoplastic and neoplastic conditions of the liver, pancreas, and biliary tract.

Results

CD73 was expressed in normal hepatobiliopancreatic tissues with subcellular-specific patterns of staining: canalicular in hepatocytes, and apical in cholangiocytes and pancreatic ducts. CD73 was present in all hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), in all pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), and in the majority of intra and extrahepatic cholangiocellular carcinomas, whereas it was detected only in a subset of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms and almost absent in acinar cell carcinoma. In addition to the canonical pattern of staining, an aberrant membranous and/or cytoplasmic expression was observed in invasive lesions, especially in HCC and PDAC. These two entities were also characterized by a higher extent and intensity of staining as compared to other hepatobiliopancreatic neoplasms. In PDAC, aberrant CD73 expression was inversely correlated with differentiation (p < 0.01) and was helpful to identify isolated discohesive tumor cells. In addition, increased CD73 expression was associated with reduced overall survival (HR 1.013) and loss of E-Cadherin.

Conclusions

Consistent CD73 expression supports the rationale for testing anti-CD73 therapies in patients with hepatobiliopancreatic malignancies. Specific patterns of expression could also be of help in the routine diagnostic workup.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00262-018-2290-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: CD73, Cholangiocarcinoma, Ecto-5′-nucleotidase, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Immunohistochemistry, Pancreatic carcinoma

Introduction

CD73, encoded by NT5E gene, is an ectoenzyme with a 5′-nucleotidase activity, converting extracellular ATP-derived AMP to adenosine [2]. Expression of this enzyme was initially described in endothelial cells, and subsequent human transcriptome and proteome analyses have shown that it is present in most normal tissues [3–6].

In physiological conditions, adenosine is present in the extracellular space at low levels, while under hypoxia or inflammation, extracellular adenosine levels can increase [7, 8]. In these circumstances, adenosine attenuates the inflammatory and immune responses, prevents collateral tissue damage, stimulates angiogenesis, and promotes cell–matrix interactions and cell migration [7–10].

In tumors, the role of CD73 was investigated with animal models of solid neoplasms, including tumor xenografts (ectopic and orthotopic), and with murine and human tumor cell lines. Collectively, these studies showed that CD73 can influence the tumor microenvironment through enzymatic and non-enzymatic functions, by sustaining cell proliferation, angiogenesis, reducing cell–cell adhesion, promoting epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and generating immune tolerance [11–13]. Several studies have identified CD73 expression in human malignant neoplasms, such as glioma, melanoma, breast, colon, pancreas, kidney, bladder, prostate, and ovarian cancers. In these studies, various materials have been examined (cell lines, tumor tissues), and different methods were used to assess CD73 mRNA or protein levels, by flow cytometry, western blot, or IHC [3, 4, 7, 10, 14–24].

The mechanisms underpinning the deregulation of CD73 expression in tumors are not completely characterized, but may involve endocrine modulation by oestrogens or thyroid hormones, hypoxia (via the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, HIF1 α), and pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-α and IFN-β (upregulation) or IFN-γ, lipopolysaccharides, and glutamic acid (downregulation) [25]. Other authors demonstrated in human melanoma cell lines that NT5E is subject to CpG methylation-dependent transcriptional silencing. In the same study, on clinical cases, it was shown that metastases developed more commonly from primary melanomas lacking NT5E promoter methylation [26]. A potentially adverse prognostic role of CD73 has also been highlighted in a pooled meta-analysis of gene expression analysis and IHC data from studies including ovarian, renal, gastrointestinal, breast, and prostate cancer cases and in a study on human malignant melanoma from our group [27, 28].

Data generated from public data sets accessible from cBioPortal show consistent CD73 mRNA expression in all investigated tumor types, at variable levels (Fig. S1) [29, 30]. Notably, potentially interesting results could be expected from the evaluation of CD73 protein expression in hepatobiliopancreatic tumors, because high CD73 mRNA levels are found in liver and pancreatic cancer [29, 30]. Moreover, integrative analysis of TCGA RNA samples of pancreatic cancer suggests an unfavorable prognostic value of higher CD73 mRNA levels [6]. However, to date, no study has characterized CD73 expression in the hepatobiliopancreatic system (normal and pathological), or in tumor-infiltrating mononuclear cells in neoplasms occurring in these sites.

The aims of this study were to examine the expression of CD73 in normal, inflammatory, and neoplastic specimens of human liver, extrahepatic biliary tract and pancreas, to define baseline and tumor-related expression of this molecule, to assess the potential use of CD73 IHC as a complementary diagnostic tool in histopathology, and to explore future perspectives for CD73 targeted therapies in hepatobiliopancreatic malignancies.

Materials and methods

Cases under study

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples from 202 surgical specimens, representative of various hepatobiliopancreatic non-neoplastic and neoplastic conditions, were retrieved from the archival files of the Institute of Pathology of the Lausanne University Hospital (1996–2017). In addition, 19 cases of acinar cell carcinoma (ACC), published in a previous study, were obtained from the Ospedale di Circolo, Varese, Italy [31]. For neoplastic samples, the baseline clinico-pathological features extracted from medical and pathological records are summarized in Supp. Table 1, and overall survival data were recorded. When necessary, the TNM staging classification was reviewed and updated to be consistent with the 2017 edition [32].

Immunohistochemistry

IHC was performed using a CD73-specific (D7F9A, rabbit monoclonal, #13160, Cell Signaling) and an E-Cadherin- specific (NCH-38, mouse monoclonal, #M3612, Agilent Dako) antibodies using the Ventana BenchMark automated stainer. Briefly, for CD73, deparaffinized slides were pre-treated with CC1 for 60 min and incubated for 60 min at 37 °C (dilution 1:100), while for E-Cadherin, they were pre-treated with CC1 for 30 min and incubated for 32 min at 37 °C (dilution 1:50). The Ultraview DAB detection kit (ref. 760 − 500) was used in both cases. In most representative cases (n = 10), an additional double staining for CD73 and E-Cadherin was also performed (same antibodies and dilution, Ventana DISCOVERY yellow and purple detection kits respectively). For CD73, an external control (reactive tonsil) was stained in each batch and positive stain in dendritic and mantle cell was verified, as previously reported [28, 33].

An adjacent section was stained with Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) (Ventana HE 600 system) for morphological reappraisal and to assist IHC interpretation.

Pathological analysis

H&E staining recuts were examined to confirm the original diagnoses and for evaluation of the density of tumor infiltrating mononuclear cells (TIMC). TIMC density was evaluated within and at the periphery of the invasive tumors and scored as follows: 1—TIMC scattered; 2—TIMC easy to find; and 3—TIMC extension similar to that of tumor cells (TC) (Fig. S2A–C), following recommendations previously reported [34].

For IHC, in non-neoplastic specimens, we recorded: the type of cells showing CD73 expression; the subcellular staining pattern and distribution; and the intensity of staining, scored as follows: 1—mild, 2—moderate, and 3—strong. In neoplastic specimens, we recorded: the percentage of CD73 + TC (and used a 5% cut off to consider a positive case) and the subcellular staining pattern, distribution, and intensity, scored as 1–3 as for the normal counterparts (Fig. S2D–F). Endothelial and stromal staining was used as internal control. Since staining intensity was frequently heterogeneous, when areas representing > 10% of the lesion stained differently, an average value was used. We also evaluated the number of cases with at least 5% of TC with intensity = 3 and the percentage of CD73 + TIMC. E-Cadherin staining was recorded as preserved or reduced/loss. Slides were evaluated independently by two junior pathologists (A. Sciarra and I. Monteiro) and consensus review for harmonization of results was performed with two senior pathologists (C. Sempoux and L. de Leval).

Statistical analysis

All variables were reported as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables were summarized as median with range, and categorical variables as frequency and percentage. Comparisons between groups of quantitative variables were performed using the Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis test. Comparisons among groups of qualitative variables were performed using χ2 and Fisher exact tests. Survival analyses included univariate and multivariate cox regression model and log-rank test. All tests were two-sided and used a significance level of 0.05. All analyses were performed with SPSS 22.0 (®2013 SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Liver

In normal liver (n = 5), and in viral and alcoholic chronic liver disease with cirrhosis (n = 5), CD73 was consistently expressed in all hepatocytes with a canalicular pattern of staining and with moderate intensity (score = 2) (Fig. S3A). In portal tracts, bile duct epithelium showed a variable fraction of cells with a mild apical pattern of staining (Fig. S3B). The endothelium of sinusoids, portal venules and arteries, and the perineurium was consistently CD73 positive (intensity score 2). A few lymphoid cells displayed mild-to-moderate expressions. Structural connective tissue and fibrous septa were unstained, both in normal and fibrotic livers.

HCC (n = 24)

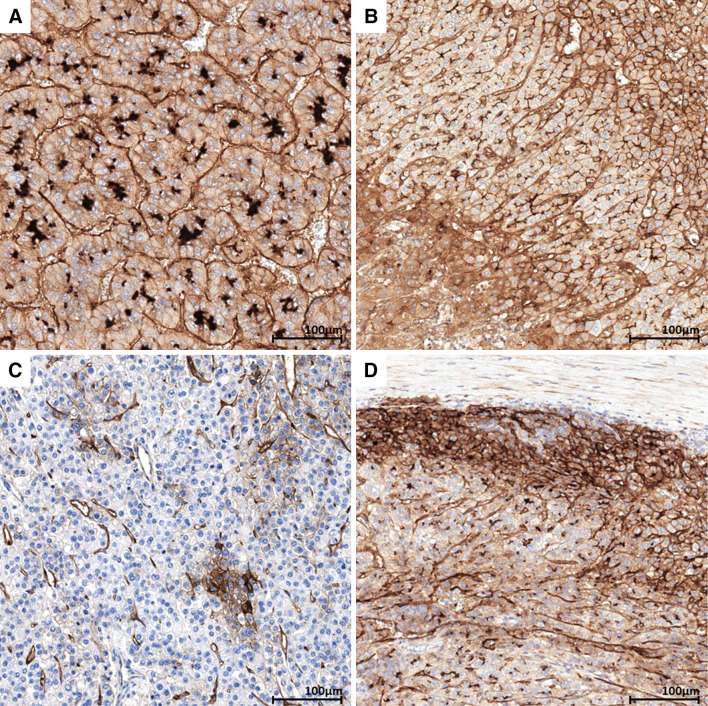

All cases of HCC featured CD73 expression in at least a fraction of TC (10–95%, median 80%) (Table 1). As compared to the normal liver, neoplastic hepatocytes systematically showed an aberrant pattern of CD73 staining (Fig. 1a): beside the preserved canalicular expression, an extension to other parts of the membrane and a cytoplasmic staining were present (Fig. 1b). Occasionally, CD73-negative areas were observed (Fig. 1c). Intensity of staining was stronger than in non-neoplastic liver, often increased in TC at the interface with fibrosis (Fig. 1d). TC with intensity = 3 were noted in 15/24 (63%) cases. High-(G3) vs low-grade (G1–G2) HCC significantly showed a higher number of CD73 + TC (p = 0.013).

Table 1.

CD73 expression in hepatobiliopancreatic neoplastic lesions

| Lesion | Staining pattern in normal counterpart | Staining pattern in lesion | CD73 + cases N/tot (%) |

CD73 + TC% median (range) |

CD73 intensity median (range) | CD73 + intensity = 3 N/tot (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | ||||||

| HCC | Canalicular (hepatocyte) | Canalicular/membranous/cytoplasmic | 24/24 (100) | 80 (10–95) | 2 (1–3) | 15/24 (63) |

| ICC | Apical (cholangiocyte) | Apical/ focally membranous or cytoplasmic | 20/24 (83) | 45 (5–95) | 1.5 (1–2) | 9/24 (38) |

| Extrahepatic bile duct | ||||||

| BilIN | Apical (cholangiocyte) | Apical | 5/9 (56) | 5 (5–30) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Carcinoma | Apical (cholangiocyte) | Apical/ focally membranous or cytoplasmic | 25/25 (100) | 40 (10–95) | 1.5 (1–2.5) | 8/25 (32) |

| Pancreas | ||||||

| PDAC | Apical (pancreatic duct cell) | Apical/membranous/cytoplasmic | 42/42 (100) | 80 (5–95) | 2 (1–3) | 26/42 (62) |

| MCA | Apical (pancreatic duct cell) | Apical | 1/5 (20) | 80 (80) | 1.5 (1.5) | 0 |

| IPMN | Apical (pancreatic duct cell) | Apical | 10/13 (77) | 30 (5–90) | 1 (0.5–1) | 0 |

| PanNET/PanNEC | Negative (endocrine islets cell) | Membranous/cytoplasmic | 8/23 (35) | 27.5 (10–95) | 1.75 (1–2) | 1/23 (4) |

| ACC | Negative (acinic cell) | Membranous/cytoplasmic | 2/19 (10) | 7.5 (5–10) | 2.25 (2–2.5) | 1/19 (5) |

ACC acinar cell carcinoma, BilIN biliary intraductal neoplasia, ICC cholangiocellular carcinoma, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, IPMN intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, MCA mucinous cystadenoma, NA not applicable, PDAC pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, PanNET/PanNEC pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor/ pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma, TC tumor cells

Fig. 1.

CD73 in hepatocellular carcinoma. a Hepatocellular carcinoma showing strong canalicular and moderate membranous and cytoplasmic staining. b Hepatocellular carcinoma comprising areas showing heterogeneous CD73 expression ranging from cytoplasmic, canalicular, and membranous expression (lower left to upper right). c Hepatocellular carcinoma mostly negative for CD73 with a cluster of CD73-positive tumor cells. d Periphery of a hepatocellular carcinoma showing strongly positive tumor cells at the interface with peritumoral fibrosis

Intrahepatic cholangiocellular carcinoma (ICC) (n = 24)

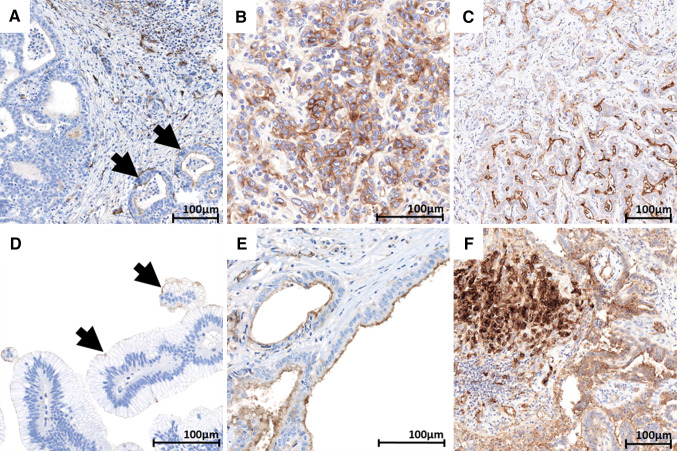

CD73 was expressed in 14/18 (78%) ICC, in 10–95% of TC (median 70%) (Table 1). Malignant cholangiocytes showed an apical staining pattern, similar to that seen in their non-neoplastic counterparts (Fig. 2a). Extension of the staining to other parts of the membrane or to the cytoplasm was observed less frequently (8/14 cases, 57%) as compared to HCC cases (Fig. 2b). Intensity of staining was heterogeneous (Fig. 2c), slightly stronger than on normal bile ducts (median intensity 1.5 vs 1), and TC with intensity = 3 were only focally observed, without a specific topographic distribution. CD73 expression was unrelated to tumor grade. High (G3) vs low grade (G1–G2) ICC significantly showed a higher number of CD73 + TC per case (p = 0.03) and comprised a larger proportion of cases with TC strongly positive for CD73 (p = 0.047).

Fig. 2.

CD73 in intrahepatic cholangiocellular carcinoma, BilIN, and extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma. a Cholangiocellular carcinoma showing positive neoplastic glands (arrows), showing a mild apical staining admixed with CD73 negative glands. b Cholangiocellular carcinoma showing moderate intensity homogeneous membranous staining. c Cholangiocellular carcinoma showing diffuse CD73 staining ranging from mild to strong in intensity. d BilIN showing very focal apical staining in dysplastic cells (arrows). e Bile duct carcinoma showing mild to moderate apical staining. f Bile duct carcinoma comprising an area with strong, membranous and cytoplasmic CD73 staining

Extrahepatic biliary tract

In normal extrahepatic biliary tract (n = 7) and gallbladder (n = 7), a variable fraction of cholangiocytes showed a mild apical, CD73 staining (Fig. S3C and S3D).

Extrahepatic bile duct intraepithelial neoplasia (BilIN) and carcinoma (n = 25)

BilIN lesions adjacent to invasive carcinoma were present in 9 cases, with 5 of them showing a focal apical CD73 staining (Fig. 2d) (Table 1).

By contrast, all invasive bile duct carcinomas showed CD73 staining, involving 15–95% of the tumor cells (median 50%) (Table 1). Malignant cholangiocytes presented a staining pattern similar to that of normal cholangiocytes (Fig. 2e), with aberrant extension to other parts of the membrane or cytoplasm in 7/15 (47%) cases (Fig. 2f). Intensity was mild to moderate (score 1 or 2) with a median value of 1.5 (1–2.5). TC with intensity = 3 were noted in 6/15 (40%) cases. High (G3) vs low-grade (G1–G2) bile duct carcinomas comprised a larger proportion of cases with TC strongly positive for CD73 (p = 0.031).

Pancreas

In normal pancreas (n = 6), and in chronic pancreatitis (n = 4), intralobular and extralobular pancreatic ducts, including the Wirsung canal, featured a variable proportion of CD73 + epithelial cells with an apical pattern of staining, similar to that observed in biliary ducts (Fig. S3E). Acinar cells and Langerhans islet cells were consistently CD73-negative (Fig. S3F). A meshwork of CD73 positive capillaries and supporting stroma was seen in the background. In chronic pancreatitis, the collagen stroma intervening between lobules showed a mild-to-moderate CD73 staining.

Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN), pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) (n = 42), and PDAC metastases (n = 12)

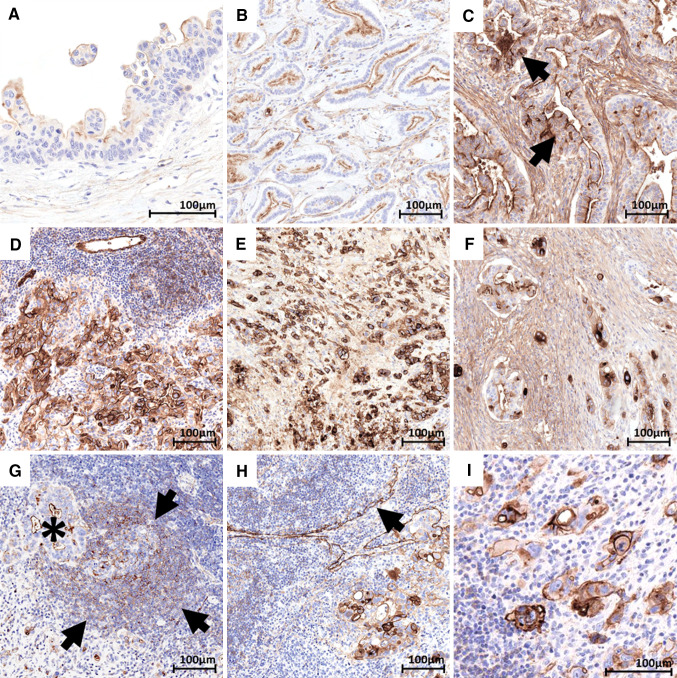

PanIN lesions adjacent to invasive carcinoma were present in 14/42 cases. CD73 was mildly expressed in 12 of them, in a fraction of the dysplastic cells (10–95%), with an apical staining pattern (intensity score = 1) (Fig. 3a) (Table 2). No variation in CD73 staining was noted according to the degree of dysplasia.

Fig. 3.

CD73 in PanIN, primary and metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. a PanIN 2 and 3 showing mild apical staining in dysplastic cells. b G1–G2 pancreatic adenocarcinoma showing mild-to-moderate apical staining in neoplastic glands. c G1–G2 primary pancreatic adenocarcinoma showing diffuse apical positivity and focally extended membranous and cytoplasmic strong staining (arrows). d G3 primary pancreatic adenocarcinoma showing membranous and cytoplasmic strong staining in neoplastic cells. e G3 primary pancreatic adenocarcinoma discohesive tumoral cells showing strong membranous and cytoplasmic staining. f Primary pancreatic adenocarcinoma showing admixed discohesive tumoral cells with strong cytoplasmic staining and neoplastic glands with mostly apical moderate staining. g G2 pancreatic adenocarcinoma nodal metastasis with apical mild staining (asterisk). The adjacent lymphoid follicles show the expected staining of germinal centre (dendritic pattern) and of mantle lymphocytes. (arrows). h G3 pancreatic adenocarcinoma nodal metastasis with moderate to strong membranous and cytoplasmic staining. Please note the positive internal control staining of nodal sinuses (arrow). i G3 pancreatic adenocarcinoma nodal metastasis with discohesive tumoral cells with strong membranous and moderate cytoplasmic staining

Table 2.

CD73 expression in PanIN, G1–G2 and G3 primary and metastatic PDAC areas

| Tumor area | CD73+ N/tot (%) |

CD73 + TC% median (range) |

CD73 intensity median (range) |

CD73 + TC% intensity = 3 N/tot (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PanIN | 12/14 (86) | 30 (10–95) | 1 (1–1.5) | 0 |

| Primary G1–G2 | 37/37 (100) | 70 (5–95) | 1 (1–2) | 15/37 (41) |

| Primary G3 | 25/25 (100) | 95 (75–95) | 3 (1.5–3) | 25/25 (100) |

| Metastasis G1–G2 | 8/8 (100) | 17 (10–90) | 1 (1–1.5) | 0 |

| Metastasis G3 | 4/4 (100) | 95 (90–95) | 2.3 (2–2.5) | 4/4 (100) |

PanIN pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia, PDAC pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, TC tumor cells

By contrast, CD73 was expressed in all cases of invasive PDAC, with a median value of 80% of positive TC (5–95%) and a median intensity of 2 (1–3). TC with intensity = 3 were noted in most of cases (26/42, 62%) (Table 1).

Strikingly, differences in staining pattern were observed according to tumor architecture, prompting a separate analysis of CD73, based on tumor grade. Among the 42 PDAC cases, 17 showed a pure well differentiated (G1–G2) histology, 5 a pure poorly differentiated (G3) histology, and 20 comprised both G1–G2 and G3 areas that were analysed separately (Fig. S4). All 37 G1–G2 PDAC areas were CD73 positive with an apical staining similar to that of pancreatic ducts (Fig. 3b) in 23/37 (62%) cases, and a staining extended to the membrane and/or to the cytoplasm in the remaining cases (Fig. 3c). Conversely, the aberrant CD73 expression was present in all G3 PDAC areas (n = 25) (Fig. 3d), at variance with G1–G2 areas (p < 0.001) (Table 2). Distinctively, poorly differentiated discohesive TC had strong cytoplasmic CD73 staining (Fig. 3E). In that respect, CD73 IHC was useful to highlight isolated discohesive TC in otherwise better differentiated areas (Fig. 3f). Moreover, in G3 PDAC areas, both extent and intensity of staining were higher than in G1–G2 areas: 40–95% vs 5–95%, (p < 0.001) and 1.5–3 vs 1–2.5, (p < 0.001), respectively. All G3 PDAC showed intensity = 3 areas, vs 41% of G1–G2 PDAC (p < 0.001).

We also examined ten nodal metastases and two peritoneal metastases, obtained from the same patients. These specimens showed pure G1–G2 or G3 differentiation (Fig. S4), and the same correlation between expression pattern of CD73 and grade as in primary lesions was observed (Table 2 and Supp. Table 2): apical staining in all eight G1–G2 and aberrant in all four G3 metastatic deposits (Fig. 3g, h). Again, isolated TC were easily identified by CD73 staining (Fig. 3i).

Mucinous pancreatic neoplasms (n = 18)

Focal and apical mild to moderate CD73 staining was observed in 1/5 (20%) mucinous cystadenomas (MCA, Fig. S5A) and in 10/13 (77%) intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN), independently of the degree of dysplasia (Fig. S5B and Table 1).

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor and carcinoma (PanNET/PanNEC) (n = 20/3)

Heterogeneous CD73 expression was seen in 7/20 (35%) PanNET (1/7 G1, 5/12 G2, 1/1 G3) and 1/3 (33%) PanNEC, with a membranous and cytoplasmic pattern of mild or moderate intensity (score 1 or 2), with no peculiar topographic distribution (Fig.S5C) and in a variable fraction of cells (10–95%), with few TC with intensity = 3 in only one PanNET G2 case (Table 1). No relationship was found with grade in PanNET group of cases.

ACC (n = 19)

Most ACCs (17/19) were completely negative for CD73 expression in the presence of adequate internal controls (Fig. S5D). Only two cases exhibited a focal (≤ 10% of TC) CD73 expression, with a membranous and cytoplasmic mild to moderate staining pattern, mainly localized at the interface with peritumoral stroma (Table 1).

TIMC

Results for TIMC are detailed in Table 3. Overall, low TIMC infiltration (quantity score = 1) was observed in 114/157 (73%) specimens of invasive tumors. In particular, this feature was observed in almost all cases of extrahepatic biliary tract carcinoma, PanNET/PanNEC and ACC. Score 3 TIMC infiltrates were only present in four HCC and three PDAC cases. These were characterized by large sheets of mononuclear infiltrating cells within and at the border of tumor, without other specific morphological or clinical characteristics. In all cases, the percentage of CD73 positive TIMC was low (≤ 20%), and median values were ≤ 5% for all histotypes, even in score 3 TIMC cases.

Table 3.

CD73 expression in TIMC

| Lesion | TIMC quantity (1/2/3) | CD73 + TIMC % median (range) |

|---|---|---|

| Liver | ||

| HCC | 16/4/4 | 1 (1–20) |

| ICC | 17/7/0 | 2 (1–10) |

| Extrahepatic bile duct | ||

| Bile duct carcinoma | 21/2/0 | 5 (1–10) |

| Pancreas | ||

| PDAC | 19/20/3 | 3 (1–20) |

| PanNET/PanNEC | 22/1/0 | 1 (1–5) |

| ACC | 19/19 | 1 (1) |

ACC acinar cell carcinoma, ICC cholangiocellular carcinoma, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, PDAC pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, PanNET/PanNEC pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor/pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma, TIMC tumor infiltrating mononuclear cells

Prognostic value of CD73 expression in hepatobiliopancreatic malignancies

Overall survival (OS) data were available for 145 patients (24 HCC, 24 ICC, 19 bile duct carcinoma, 38 PDAC, 21 PanNET/PanNEC, and 19 ACC), with a median follow-up of 17 (0.2–107) months. In univariate analysis, a reduced OS for hepatobiliopancreatic malignancies was significantly associated with a pT3-T4 TNM stage (HR = 2.242, p = 0.016), nodal invasion (HR = 4.283, p < 0.001), microvascular invasion (HR = 2.760, p = 0.009), G2-G3 histology (HR = 2.463, p = 0.013), as well as an increased percentage of CD73 + TC% (HR = 1.010, p = 0.032), CD73 intensity (HR = 1.489, p = 0.063) and CD73 + TC% intensity = 3 (HR = 1.026 p = 0.006) (Supp. Table 3). Multivariate analysis identified nodal invasion [HR = 4.423 (96% CI 1.937–10.1), p < 0.001], G2–G3 histology [HR = 2.381 (95% CI 1.153–4.917), p = 0.019], and an increased percentage of CD73 + TC% [HR = 1.013 (95% CI 1.001–1.025), p = 0.032] as independent factors affecting the OS. A 50% CD73 + TC cutoff separated cases with longer (< 50% CD73 + TC) and reduced (≥ 50% CD73 + TC) OS (p = 0.041, long-rank test) (Fig.S6). Cox univariate subgroup analyses for individual hepatobiliopancreatic malignancy are indicated in Supp. Table 4. Specifically, a significant association of OS and CD73 + TC% was observed in HCC and PDAC subgroups.

Putative EMT phenotype (loss of E-Cadherin expression) in CD73 + PDAC

E-Cadherin expression was analysed in the 42 PDAC cases. Areas showing ductal morphology (G1–G2) were characterized by a preserved membranous E-Cadherin staining in all cases. In areas displaying poorly differentiated morphology (G3), a consistent fraction of CD73 positive discohesive single cells, were also characterized by a complete or near complete loss of the canonical membranous E-Cadherin expression, consistent with an EMT phenotype (Fig.S7).

Discussion

Recent discovery of CD73 immunosuppressive and pro-angiogenic functions promoting onset and progression of cancer has raised significant hope in the future development of targeted anti-CD73 treatments [7, 35]. However, to achieve this aim, many technical, preclinical, and clinical obstacles have still to be overcome, including the precise characterization of CD73 expression in different normal and neoplastic human tissues.

In this study, we focused on the hepatobiliopancreatic system, selecting a large series of different neoplasms, and corresponding normal tissues and preneoplastic conditions and used IHC. We demonstrated CD73 protein expression in normal liver, biliary tract, and pancreas, in accordance with data generated in human transcriptome and proteome analyses [5, 6]. More specifically, in addition to the ubiquitous endothelial staining, we found a restriction to different cell types, with distinct subcellular patterns of staining. In hepatocytes, bile and pancreatic ducts, CD73 was expressed with a polarized, apical pattern, corresponding to the canalicular pole of hepatocytes or the luminal pole of ductal cells. This “baseline” expression pattern was maintained in inflammatory conditions (cirrhosis and pancreatitis), and in non-invasive lesions (BilIN, mucinous pancreatic neoplasms, and PanIN). In invasive lesions, different patterns of CD73 IHC were observed, in general encompassing an increase in both the extent and intensity of staining that we defined as an “aberrant pattern”.

HCC and PDAC were the two entities exemplifying this feature. In these tumors, the normal CD73 polarized distribution (canalicular for the liver and apical for pancreatic ducts) shifted to a more diffuse distribution, with extended membrane staining and a cytoplasmic accumulation.

A cytoplasmic presence of 5′ nucleotidase was first documented with immunoelectron analyses of rat liver and kidney, colocalized in multivesicular endosomes, lipoprotein particles, and Golgi membrane [36]. According to the human protein atlas, a cytosolic expression of CD73 has been identified by immunofluorescence microscopy in human adherent myoblast, epidermoid carcinoma, and glioblastoma cell lines, with lower levels as compared to those in the plasma membrane [5]. Therefore, the absence of a cytoplasmic IHC staining in normal tissues could reflect intracellular CD73 levels below the limit of detection, while the cytoplasmic accumulation of CD73 in tumors cells coupled with an extended membranous staining, may be due to a strongly increased transcriptional activity of NT5E in these entities. For PDAC, this phenomenon is similar to that observed for MUC1 expression, previously reported as a useful marker to distinguish invasive PDAC from reactive alterations [37]. Accordingly, CD73 pattern of staining could be eventually tested as a diagnostic tool, knowing that intense and diffuse membranous/cytoplasmic staining was observed only in neoplastic cases (specificity = 100%). We also found CD73 staining very useful to highlight isolated, discohesive PDAC TC dispersed in desmoplastic stroma or in lymph nodes, that could be missed on standard analysis on H&E sections. As such, in the routine diagnostic workup of a pancreatic specimen, a pre-operative biopsy or a surgical sample, an aberrant CD73 pattern of staining might favour the diagnosis of PDAC over reactive ductal atypia in the context of chronic pancreatitis. However, it should be stressed that CD73 IHC can be less helpful in highlighting G1–G2 tumors, as these showed in most of cases an apical pattern of staining similar to normal pancreatic ducts. HCC and PDAC were also characterized by the highest proportion of CD73 + TC and the strongest intensity of staining. Clusters of cells with intense staining were observed in > 50% of HCC and PDAC cases, suggesting that CD73 is deregulated and potentially targetable in these two entities. Blockade of CD73 activity in these two neoplasms could be of particular interest, as both HCC and PDAC are considered to be recalcitrant to conventional treatments and their responsiveness to immunotherapy with PD-L1 inhibitors is debated [38–41].

The immune suppressive effect of CD73 is mediated by the extracellular concentration of adenosine, which interacts with signals to immune cells via its ligation to adenosine receptor (AR) and, particularly, to A2AR [42]. Accordingly, it has been demonstrated in in vitro models that A2AR stimulation inhibits a large spectrum of inflammatory activities including the proliferation, cytokine production, and cytotoxicity of T cells [43, 44]. The restoration of T-cell proliferation and activity could be an important endpoint in HCC and PDAC, as these entities have been consistently reported as characterized by an impaired T-cell infiltrate, via increased TGF-beta levels and switching from Th1- to Th2-type cytokine secretion [45, 46]. Moreover, a therapeutic CD73 blockade may prevent its non-enzymatic direct effects on tumor cells leading to reduced cell adhesion and interaction with extracellular matrix [10]. Thus, CD73 blockade could be particularly helpful in these entities if eventually incorporated in combined immunotherapy strategies [47].

Refining the results from a previous study, which suggested increased CD73 expression in neoplastic vs normal human pancreas using functional proteomic analysis and IHC, we observed that CD73 expression increased in parallel with morphological tumor grade and that an aberrant pattern was typically observed in poorly differentiated discohesive PDAC cells, suggesting that this molecule is also a marker of biological aggressiveness [48]. Notably, this was the only significant correlation that we observed between CD73 IHC and other clinico-pathological variables. One explanation could be found in the tumoral microenvironment of poorly differentiated tumors. In these conditions, TC suffer from hypoxic stress and adaptively express protective molecules such as HIF-1, which is known to positively regulate CD73 expression [7, 49, 50]. As the amount of released adenosine also depends on the extent and severity of ischemia/necrosis, we sought to assess if CD73 expression was increased at the interface with necrotic areas. However, in our specimens, necrosis was focal and the relationship between ischemia/necrosis and CD73 expression was not evaluable [51].

One additional possible explanation of the CD73 protein overexpression could be found in EMT. Indeed, increased CD73 levels were detected in cell lines of breast carcinoma undergoing EMT-induced by TGF-β [52, 53]. While EMT is a hallmark of a more aggressive phenotype and is also induced by HIF-1, TGF-β is secreted by tumors and has an immunosuppressive role similar to that of CD73 [54–56]. Interestingly, EMT has been associated with a shift from the apical-basolateral polarity of epithelial cells towards the anterior-posterior (front-rear) polarity of motile cells, a feature similar to the switch from basal to aberrant extended CD73 membranous staining we observed [57]. A potential link between CD73 and EMT-like phenotype has been recently presented in a mouse model of melanoma showing that, in relapsed melanomas with a mesenchymal-like phenotype, CD73 transcription was induced through the cooperation of released pro-inflammatory cytokines and activating MAPK mutations through the c-Jun/AP-1 transcription factor complex [58]. In accordance with these data, a fraction of CD73 strongly positive isolated tumor cells showed a loss of E-Cadherin, one of the most frequently investigated putative EMT biomarker in pancreatic cancer, suggesting that CD73 expression could be, at least partially, associated with an EMT phenotype.

Deregulated, aberrant CD73 expression was less frequently observed in tumors derived from bile ducts (intra and extrahepatic), where the main pattern was still apical and the proportion and intensity of CD73 + TC were lower. Accordingly, TCGA network derived data show lower CD73 mRNA expression in these entities than in HCC and PDAC [29, 30]. We also observed that most of ACC (89%) and PanNET/PanNEC (57%) did not express CD73, this feature epitomizing the negative basal pattern of normal pancreatic acinar and endocrine cells. Our data regarding PanNET/PanNEC are in accordance with those from a recent report indicating that > 70% of gastrointestinal NETs and 40% of NECs are CD73 negative [59]. As pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms are considered a heterogeneous entity, with PanNEC being molecularly more similar to PDAC than to PanNET, CD73 should be investigated in more cases to better understand if the CD73 expression is different in PanNET vs PanNEC [60].

Interestingly, a recent pooled meta-analysis has also suggested the prognostic role of CD73 in many tumors, including some gastrointestinal malignancies [27]. In accordance with these results, in our series, an increased CD73 expression—in terms of percentage of positive cells—was also associated with a reduced overall survival, even if with a very limited impact (HR 1.013). Because CD73 was early identified as an immunoregulatory molecule expressed by lymphocytes, we also evaluated CD73 expression in TIMC. In this series, TIMC quantity was generally low, in accordance with the notion that hepatobiliopancreatic tumors are not strongly immunogenic, except in rare morphological variants [61, 62]. The fraction of CD73 positive TIMC was also consistently low, independently of the extent of the inflammatory infiltrate, tumor histotype, and pathological variables. This result supports the notion that the neoplastic cells represent the main source of CD73 in these tumors [7].

In conclusion, CD73 is consistently expressed in the majority of hepatobiliopancreatic malignancies, with histotype-specific pattern of staining. Strongest and aberrant expression in poorly differentiated tumors, and, particularly, in HCC and PDAC, make these lesions most suitable for a targeted treatment.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the FP7 European TumAdoR project (Grant 602200), that aims at bringing anti-CD73 mAbs candidates to clinical trial; Prof. Fausto Sessa (Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Insubria, Varese, Italy) for providing acinar cell carcinoma specimens; Dr. Jerome Pasquier (Institute for Social and Preventive Medicine, Lausanne University Hospital), Dr. sc. Nathalie Piazzon, Dr. sc. Susana Leuba and Mr. Jean-Daniel Roman (Institute of Pathology, Lausanne University Hospital) for their operational support.

Abbreviations

- ACC

Acinar cell carcinoma

- BilIN

Bile duct intraepithelial neoplasia

- EMT

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- HIF1

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1

- ICC

Intrahepatic cholangiocellular carcinoma

- IPMN

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms

- MCA

Mucinous cystadenoma

- PDAC

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PanIN

Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia

- PanNET

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor

- PanNEC

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor and carcinoma

- TC

Tumor cells

- TIMC

Tumor infiltrating mononuclear cells

Author contributions

AS, IM, BG, NH, and SLR data collection. AS, IM, CS, and LL data analysis. AS, IM, CMC, CC, SLR, PR, CS, and LL drafting. CMC, CC, CS, and LL study design.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007–2013) (under Grant agreement 602200).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Vaud cantonal ethics commission on human research (protocol 17/15). All samples were used in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Patients’ written informed consent was obtained for recent cases (2014–2018). In older cases, the presence of an explicit refusal for the specimen use for research purposes represented an exclusion criterion.

Contributor Information

Christine Sempoux, Email: christine.sempoux@chuv.ch.

Laurence de Leval, Email: laurence.deleval@chuv.ch.

References

- 1.Sciarra A, Monteiro I, Ménétrier-Caux C, Caux C, La Rosa S, Romero P, Sempoux C, de Leval L. CD73 in hepatobiliopancreatic system: a potential target for immunotherapy and additional tool for the pathological diagnosis. Virchows Arch. 2018;473(Suppl. 1):S124. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmermann H, Zebisch M, Strater N. Cellular function and molecular structure of ecto-nucleotidases. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8(3):437–502. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9309-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomson L, Ruedi J, Glass A, Moldenhauer G, Moller P, Low M, Klemens M, Massaia M, Lucas A. Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies to the glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-anchored lymphocyte differentiation antigen ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) HLA. 1990;35(1):9–19. doi: 10.1086/185739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu C, Jin X, Tsueng G, Afrasiabi C, Su AI. BioGPS: building your own mash-up of gene annotations and expression profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D313–D316. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su AI, Wiltshire T, Batalov S, Lapp H, Ching KA, Block D, Zhang J, Soden R, Hayakawa M, Kreiman G, et al. A gene atlas of the mouse and human protein-encoding transcriptomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(16):6062–6067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400782101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uhlen M, Fagerberg L, Hallstrom BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson A, Kampf C, Sjostedt E, Asplund A, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347(6220):1260419. doi: 10.1126/science.1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antonioli L, Yegutkin GG, Pacher P, Blandizzi C, Haskó G. Anti-CD73 in cancer immunotherapy: awakening new opportunities. Trends Cancer. 2016;2(2):95–109. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colgan SP, Eltzschig HK, Eckle T, Thompson LF. Physiological roles for ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) Purinergic Signal. 2006;2(2):351–360. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-5302-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haskó G, Linden J, Cronstein B, Pacher P. Adenosine receptors: therapeutic aspects for inflammatory and immune diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(9):759–770. doi: 10.1038/nrd2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadej R, Skladanowski AC. Dual, enzymatic and non-enzymatic, function of ecto-5′-nucleotidase (eN, CD73) in migration and invasion of A375 melanoma cells. Acta Biochim Pol. 2012;59(4):647–652. doi: 10.18388/abp.2012_2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao ZW, Wang HP, Lin F, Wang X, Long M, Zhang HZ, Dong K. CD73 promotes proliferation and migration of human cervical cancer cells independent of its enzyme activity. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):135. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3128-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L, Fan J, Thompson LF, Zhang Y, Shin T, Curiel TJ, Zhang B. CD73 has distinct roles in nonhematopoietic and hematopoietic cells to promote tumor growth in mice. J Clin Investig. 2011;121(6):2371–2382. doi: 10.1172/JCI45559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antonioli L, Pacher P, Vizi ES, Hasko G. CD39 and CD73 in immunity and inflammation. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19(6):355–367. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bono MR, Fernández D, Flores-Santibáñez F, Rosemblatt M, Sauma D. CD73 and CD39 ectonucleotidases in T cell differentiation: beyond immunosuppression. FEBS Lett. 2015;589(22):3454–3460. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang B, Song B, Wang X, Chang XS, Pang T, Zhang X, Yin K, Fang GE. The expression and clinical significance of CD73 molecule in human rectal adenocarcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(7):5459–5466. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhi X, Wang Y, Yu J, Yu J, Zhang L, Yin L, Zhou P. Potential prognostic biomarker CD73 regulates epidermal growth factor receptor expression in human breast cancer. IUBMB Life. 2012;64(11):911–920. doi: 10.1002/iub.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu XR, He XS, Chen YF, Yuan RX, Zeng Y, Lian L, Zou YF, Lan N, Wu XJ, Lan P. High expression of CD73 as a poor prognostic biomarker in human colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106(2):130–137. doi: 10.1002/jso.23056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu S, Shao QQ, Sun JT, Yang N, Xie Q, Wang DH, Huang QB, Huang B, Wang XY, Li XG, et al. Synergy between the ectoenzymes CD39 and CD73 contributes to adenosinergic immunosuppression in human malignant gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(9):1160–1172. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kondo T, Nakazawa T, Murata SI, Katoh R. Expression of CD73 and its ecto-5′-nucleotidase activity are elevated in papillary thyroid carcinomas. Histopathology. 2006;48(5):612–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stella J, Bavaresco L, Braganhol E, Rockenbach L, Farias PF, Wink MR, Azambuja AA, Barrios CH, Morrone FB, Oliveira Battastini AM. Differential ectonucleotidase expression in human bladder cancer cell lines. Urol Oncol. 2010;28(3):260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh HK, Sin JI, Choi J, Park SH, Lee TS, Choi YS. Overexpression of CD73 in epithelial ovarian carcinoma is associated with better prognosis, lower stage, better differentiation and lower regulatory T cell infiltration. J Gynecol Oncol. 2012;23(4):274–281. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2012.23.4.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Q, Du J, Zu L. Overexpression of CD73 in prostate cancer is associated with lymph node metastasis. Pathol Oncol Res. 2013;19(4):811–814. doi: 10.1007/s12253-013-9648-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turcotte M, Spring K, Pommey S, Chouinard G, Cousineau I, George J, Chen GM, Gendoo DM, Haibe-Kains B, Karn T, et al. CD73 is associated with poor prognosis in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75(21):4494–4503. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leclerc BG, Charlebois R, Chouinard G, Allard B, Pommey S, Saad F, Stagg J. CD73 expression is an independent prognostic factor in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(1):158–166. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao ZW, Dong K, Zhang HZ. The roles of CD73 in cancer. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014:460654. doi: 10.1155/2014/460654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H, Lee S, Nigro CL, Lattanzio L, Merlano M, Monteverde M, Matin R, Purdie K, Mladkova N, Bergamaschi D, et al. NT5E (CD73) is epigenetically regulated in malignant melanoma and associated with metastatic site specificity. Br J Cancer. 2012;106(8):1446–1452. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang R, Zhang Y, Lin X, Gao Y, Zhu Y. Prognositic value of CD73-adenosinergic pathway in solid tumor: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Oncotarget. 2017;8(34):57327–57336. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monteiro I, Vigano S, Faouzi M, Treilleux I, Michielin O, Menetrier-Caux C, Caux C, Romero P, de Leval L. CD73 expression and clinical significance in human metastatic melanoma. Oncotarget. 2018;9(42):26659–26669. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(5):401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6(269):pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.La Rosa S, Adsay V, Albarello L, Asioli S, Casnedi S, Franzi F, Marando A, Notohara K, Sessa F, Vanoli A, et al. Clinicopathologic study of 62 acinar cell carcinomas of the pancreas: insights into the morphology and immunophenotype and search for prognostic markers. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(12):1782–1795. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318263209d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brierley JDGM, Wittekind C. TNM classification of malignant tumours. 8. New york: Wiley; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Airas L. CD73 and adhesion of B-cells to follicular dendritic cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 1998;29(1–2):37–47. doi: 10.3109/10428199809058380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salgado R, Denkert C, Demaria S, Sirtaine N, Klauschen F, Pruneri G, Wienert S, Van den Eynden G, Baehner FL, Penault-Llorca F, et al. The evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer: recommendations by an International TILs Working Group 2014. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(2):259–271. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allard D, Allard B, Gaudreau PO, Chrobak P, Stagg J. CD73-adenosine: a next-generation target in immuno-oncology. Immunotherapy. 2016;8(2):145–163. doi: 10.2217/imt.15.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zimmermann H. 5′-Nucleotidase: molecular structure and functional aspects. Biochem J. 1992;285(Pt 2):345–365. doi: 10.1042/bj2850345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Monges GM, Mathoulin-Portier MP, Acres RB, Houvenaeghel GF, Giovannini MF, Seitz JF, Bardou VJ, Payan MJ, Olive D. Differential MUC 1 expression in normal and neoplastic human pancreatic tissue. An immunohistochemical study of 60 samples. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;112(5):635–640. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/112.5.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knudsen ES, Vail P, Balaji U, Ngo H, Botros IW, Makarov V, Riaz N, Balachandran V, Leach S, Thompson DM, et al. Stratification of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: combinatorial genetic, stromal, and immunologic markers. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(15):4429–4440. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inarrairaegui M, Melero I, Sangro B. Immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma: facts and hopes. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(7):1518–1524. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao HL, Liu L, Qi ZH, Xu HX, Wang WQ, Wu CT, Zhang SR, Xu JZ, Ni QX, Yu XJ. The clinicopathological and prognostic significance of PD-L1 expression in pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2018;17(2):95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.hbpd.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calderaro J, Rousseau B, Amaddeo G, Mercey M, Charpy C, Costentin C, Luciani A, Zafrani ES, Laurent A, Azoulay D, et al. Programmed death ligand 1 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma: relationship with clinical and pathological features. Hepatology. 2016;64(6):2038–2046. doi: 10.1002/hep.28710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohta A. A metabolic immune checkpoint: adenosine in tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2016;7:109. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sitkovsky MV, Lukashev D, Apasov S, Kojima H, Koshiba M, Caldwell C, Ohta A, Thiel M. Physiological control of immune response and inflammatory tissue damage by hypoxia-inducible factors and adenosine A2A receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:657–682. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allard B, Pommey S, Smyth MJ, Stagg J. Targeting CD73 enhances the antitumor activity of anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 mAbs. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(20):5626–5635. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shirabe K, Motomura T, Muto J, Toshima T, Matono R, Mano Y, Takeishi K, Ijichi H, Harada N, Uchiyama H, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and hepatocellular carcinoma: pathology and clinical management. Int J Clin Oncol. 2010;15(6):552–558. doi: 10.1007/s10147-010-0131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang JH, Jiang Y, Pillarisetty VG. Role of immune cells in pancreatic cancer from bench to clinical application: an updated review. Medicine (Baltim) 2016;95(49):e5541. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leone RD, Emens LA. Targeting adenosine for cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0360-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haun RS, Quick CM, Siegel ER, Raju I, Mackintosh SG, Tackett AJ. Bioorthogonal labeling cell-surface proteins expressed in pancreatic cancer cells to identify potential diagnostic/therapeutic biomarkers. Cancer Biol Ther. 2015;16(10):1557–1565. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2015.1071740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Synnestvedt K, Furuta GT, Comerford KM, Louis N, Karhausen J, Eltzschig HK, Hansen KR, Thompson LF, Colgan SP. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) regulation by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates permeability changes in intestinal epithelia. J Clin Investig. 2002;110(7):993–1002. doi: 10.1172/JCI0215337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim Y, Lin Q, Glazer PM, Yun Z. Hypoxic tumor microenvironment and cancer cell differentiation. Curr Mol Med. 2009;9(4):425–434. doi: 10.2174/156652409788167113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang B. CD73: a novel target for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2010;70(16):6407–6411. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu J, Liao X, Li L, Lv L, Zhi X, Yu J, Zhou P. A preliminary study of the role of extracellular—5′-nucleotidase in breast cancer stem cells and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. In vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2017;53(2):132–140. doi: 10.1007/s11626-016-0089-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Valcourt U, Carthy J, Okita Y, Alcaraz L, Kato M, Thuault S, Bartholin L, Moustakas A. Analysis of epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by transforming growth factor beta. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1344:147–181. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2966-5_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang L, Huang G, Li X, Zhang Y, Jiang Y, Shen J, Liu J, Wang Q, Zhu J, Feng X, et al. Hypoxia induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition via activation of SNAI1 by hypoxia-inducible factor—1alpha in hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:108. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoshimura A, Muto G. TGF-beta function in immune suppression. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2011;350:127–147. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xiong L, Wen Y, Miao X, Yang Z. NT5E and FcGBP as key regulators of TGF-1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) are associated with tumor progression and survival of patients with gallbladder cancer. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;355(2):365–374. doi: 10.1007/s00441-013-1752-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maier HJ, Wirth T, Beug H. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic carcinoma. Cancers. 2010;2(4):2058–2083. doi: 10.3390/cancers2042058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reinhardt J, Landsberg J, Schmid-Burgk JL, Ramis BB, Bald T, Glodde N, Lopez-Ramos D, Young A, Ngiow SF, Nettersheim D, et al. MAPK signaling and inflammation link melanoma phenotype switching to induction of CD73 during immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2017;77(17):4697–4709. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ono K, Shiozawa E, Ohike N, Fujii T, Shibata H, Kitajima T, Fujimasa K, Okamoto N, Kawaguchi Y, Nagumo T, et al. Immunohistochemical CD73 expression status in gastrointestinal neuroendocrine neoplasms: a retrospective study of 136 patients. Oncol Lett. 2018;15(2):2123–2130. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hackeng WM, Hruban RH, Offerhaus GJ, Brosens LA. Surgical and molecular pathology of pancreatic neoplasms. Diagn Pathol. 2016;11(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s13000-016-0497-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lutz ER, Kinkead H, Jaffee EM, Zheng L. Priming the pancreatic cancer tumor microenvironment for checkpoint-inhibitor immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3(11):e962401. doi: 10.4161/21624011.2014.962401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kasper HU, Drebber U, Stippel DL, Dienes HP, Gillessen A. Liver tumor infiltrating lymphocytes: comparison of hepatocellular and cholangiolar carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(40):5053–5057. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.