Abstract

Background

Adnexal carcinomas are rare and heterogeneous skin tumors, for which no standard treatments exist for locally advanced or metastatic tumors.

Aim of the study

To evaluate the expression of PD-L1 and CD8 in adnexal carcinomas, and to study the association between PD-L1 expression, intra-tumoral T cell CD8+ infiltrate, and metastatic evolution.

Materials and methods

Eighty-three adnexal carcinomas were included. Immunohistochemistry using anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies (E1L3N and 22C3) and CD8 was performed. PD-L1 expression in tumor and immune cells, and CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) density were analyzed semi-quantitatively.

Results

Among the 60 sweat gland, 18 sebaceous and 5 trichoblastic carcinomas, 11% expressed PD-L1 in ≥ 1% tumor cells, more frequently sweat gland carcinomas (13%, 8/60) including apocrine carcinoma (40%, 2/5) and invasive extramammary Paget disease (57%, 4/7). Immune cells expressed significantly more PD-L1 than tumor cells (p < 0.01). Dense CD8+ TILs were present in 60% trichoblastic, 43% sweat gland, and 39% sebaceous carcinomas. CD8+ TILs were associated with PD-L1 expression by tumor cells (p < 0.01). Thirteen patients out of 47 developed metastases (27%) with a median follow-up of 30.5 months (range 7–36). Expression of PD-L1 by tumor cells was associated with the development of metastasis in univariate analysis (HR 4.0, 95% CI 1.1–15, p = 0.0377) but not in multivariate analysis (HR 4.1, 95% CI 0.6–29, p = 0.15).

Conclusion

PD-L1 expression is highly heterogeneous among adnexal carcinoma subtypes, higher in apocrine carcinoma and invasive extramammary Paget disease, and associated with CD8+ TILs. Our data suggest the interest of evaluating anti-PD1 immunotherapy in advanced or metastatic cutaneous adnexal carcinoma.

Keywords: Cutaneous adnexal carcinoma, Programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), CD8

Introduction

Cutaneous adnexal carcinomas are a large and diverse group of tumors, deriving from different types of adnexal epithelium present in normal skin (sebaceous glands, apocrine glands, eccrine glands, and hair follicles) [1, 2]. Their exact prevalence is unknown but these lesions are rare in comparison to other skin cancers [3]. Some of the malignant adnexal tumors have high rates of local recurrence and distant metastases [4]: 20–25% of porocarcinomas and as much as 50% digital papillary adenocarcinomas may recur or metastasize [5–8]. In cutaneous adnexal carcinomas, surgery is the only curative treatment, and there is a lack of therapy for unresectable or metastatic tumors: radiotherapy may be proposed for locally advanced tumors [9], whereas no consensus exists regarding management of metastatic cases, which remain an area of high unmet clinical need [10, 11].

Programmed death-1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) constitute an important immune checkpoint [12], playing a major role in evasion of malignant tumor cells from the immune system [13]. The prognostic value of PD-L1 expression by tumor cells remains controversial. In some studies, it was reported as a marker of poor prognosis [14]. On the contrary, in melanoma patients, PD-L1 expression may be associated with better prognosis [15]. The predictive value of PDL-1 expression by tumor cells for response to anti-PD1/PD-L1 agents has been largely studied and reported. In melanoma as in lung carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma and urothelial carcinoma, increased response rates, improved progression-free survival and overall survival are observed in patients with higher PD-L1 tumor expression [16].

To our knowledge, there is no report examining PD-L1 expression in cutaneous adnexal carcinomas. In the context of the potential use of anti-PD1/PD-L1 therapy in cutaneous adnexal carcinomas, we aimed here to determine the expression pattern of PD-L1 in tumor cells and microenvironment immune cells in cutaneous adnexal carcinomas, and to analyze its association with the level of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) and with metastatic evolution.

Materials and methods

Patients

Eighty three patients with cutaneous adnexal carcinoma from a single University hospital (Hôpital Saint Louis) diagnosed between 2002 and 2018 were included in the study. Diagnoses were performed according to the latest World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for skin cancers, and validated in the French CARADERM (CAncers RAres DERMatologiques—rare skin cancers) Network (National Institute of Cancer). For all patients, there was enough formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tumor material remaining after the diagnosis had been established to qualify the samples for additional immunohistochemical studies. All surgical samples of included patients were taken at diagnosis, before any medical treatment of the disease. Clinical data at diagnosis and follow-up data were collected from clinical files. Tumors were staged using the eighth TNM version of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) (2017), according to the recommendation of the WHO 2018 classification of skin tumors.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed according to the following protocol: 3 μm paraffin sections were placed on Superfrost plus® glass slides. PD-L1 expression was performed using a BenchMark Ultra® automated immunostainer (Roche-Ventana, Basel, Switzerland) and monoclonal antibodies against PD-L1, E1L3N [1:200 dilution (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA)] and 22C3 [1:50 dilution (Dako, Hamburg, Germany)]. CD8 immunostaining was performed using anti-CD8 4B11 clone [1:50 dilution (Dako, Hamburg, Germany)].

Microscopic evaluation

Immunostaining was assessed by two pathologists (M. Battistella and L. Duverger) independently, blindly from follow-up data, when available.

The immunohistochemical expression of PD-L1 was quantified semi-quantitatively. Adnexal carcinomas were divided as previously described into 4 groups according to the percentage of PD-L1 positive tumor cells: < 1% (TC0), 1–4% (TC1), 5–49% (TC2) and > 50% (TC3), and into four groups according to the percentage of PD-L1 positive immune cells: < 1% (IC0), 1–4% (IC1), 5–10% (IC2) and > 10% (IC3) [17].

For subsequent analyses, tumors were considered to be PD-L1 (+) when ≥ 1% of tumor cells demonstrated membranous staining.

To evaluate CD8+ TIL, we used a semi-quantitative visual score: none (0), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3). The degree of CD8+ TIL infiltration was evaluated into the tumor and in its stroma. Stromal TIL evaluation, which is more reproducible, was further used for the association analysis with PD-L1 tumor cell expression [18, 19].

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were described as medians (25th; 75th interquartile range) and dichotomous data as percentages. Differences in frequencies of quantitative variables were compared using the χ2 test with Pearson’s correction or a Fisher’s exact test when sample sizes were too small (expected values below 5). Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the proportion of samples with CD8+ TIL in PD-L1(+) and PD-L1(−) samples. As we had missing data for PD-L1 using 22C3 clone, we used preferentially E1L3N antibody results for all the statistical tests of the study.

We evaluated the agreement between the PD-L1 results with the two antibodies (E1L3N and 22C3 clones) using Cohen’s weighted kappa (κ) statistic interpreted as follows: κ < 0.20, poor strength; κ = 0.21–0.40, fair; κ = 0.41–0.60, moderate; κ = 0.61–0.80, good; κ = 0.81–1.00, very good. Missing data for 22C3 were excluded of this analysis.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of factors associated with metastatic evolution were performed with a Cox proportional-hazard model, including in the multivariate analysis all covariates with p < 0.10 in univariate analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (v19.0 for Windows 2010, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), GraphPad Prism® (v7 for Windows, Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) and R (v3.5.2, R project). p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 83 cutaneous adnexal carcinomas from 83 patients were included (Table 1). There were 60 sweat gland carcinomas, 18 sebaceous carcinomas, and 5 trichoblastic carcinomas. Among sweat gland carcinomas, the most frequent types included 14 porocarcinomas, 11 hidradenocarcinomas and 10 ductal adenocarcinomas with no other specification (NOS).

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 51 (62) |

| Female | 32 (38) |

| Age in years, median (range) | 68 (26; 95) |

| Tumor type | |

| Sweat gland carcinoma | 60 (72) |

| Porocarcinoma | 14 (17) |

| Hidradenocarcinoma | 11 (13) |

| Ductal adenocarcinoma NOS | 10 (12) |

| Microcystic adnexal carcinoma | 5 (6) |

| Syringoid eccrine carcinoma | 5 (6) |

| Apocrine carcinoma | 5 (6) |

| Invasive extramammary Paget disease | 7 (8) |

| Digital papillary adenocarcinoma | 2 (3) |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 1 (1) |

| Sebaceous carcinoma | 18 (21) |

| Trichoblastic carcinoma | 5 (7) |

Continuous variables are described as median (25th; 75th interquartile range) and dichotomous data as percentage

NOS no other specification

PD-L1 expression in cutaneous adnexal carcinomas

The results obtained with the 22C3 clone and the E1L3N clone for PD-L1 expression showed a very good agreement, both for TC and IC evaluation (κ > 0.8, Table 2).

Table 2.

PD-L1 expression using immunohistochemistry with 22C3 and E1L3N clones

| TC0 | TC1 | TC2 | TC3 | κ | IC0 | IC1 | IC2 | IC3 | κ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1L3N | 68 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.831 | 60 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 0.818 |

| 22C3 | 69 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 60 | 11 | 3 | 0 |

PD-L1 positive tumor cells: < 1% (TC0), 1–4% (TC1), 5–49% (TC2) and > 50% (TC3)

PD-L1 positive immune cells: < 1% (IC0), 1–4% (IC1), 5–10% (IC2) and > 10% (IC3)

In the whole cohort, 11% of adnexal carcinomas had positive PD-L1 expression in the tumor cells (TC) (cut-off ≥ 1%) and 24% had positive PD-L1 expression in the microenvironment immune cells (IC) (cut-off ≥ 1%) (Table 3). Most cases had focal PD-L1 expression (TC1 or IC1) whereas strong PD-L1 expression (TC2 or more; IC2 or more) was seen in a minority of cases (2 cases TC2–3; 3 cases IC2–3).

Table 3.

PDL-1 expression in cutaneous adnexal carcinomas

| n | PD-L1 tumor cells | PD-L1 immune cells | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positivea (%) | Negative (%) | Positiveb (%) | Negative (%) | ||

| Sweat gland carcinoma | 60 | 8 (13) | 52 (87) | 11 (18) | 49 (82) |

| Porocarcinoma | 14 | 1 (7) | 13 (93) | 3 (21) | 11 (79) |

| Hidradenocarcinoma | 11 | 1 (9) | 10 (91) | 2 (18) | 9 (82) |

| Ductal adenocarcinoma NOS | 10 | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | 1 (10) | 9 (90) |

| Microcystic adnexal carcinoma | 5 | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 0 (0) | 5 (100) |

| Syringoid eccrine carcinoma | 5 | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 0 (0) | 5 (100) |

| Apocrine carcinoma | 5 | 2 (40) | 3 (60) | 1 (20) | 4 (86) |

| Invasive EMPD | 7 | 4 (57) | 3 (43) | 4 (57) | 1 (43) |

| Digital papillary adenocarcinoma | 2 | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 1 | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) |

| Sebaceous carcinoma | 18 | 1 (6) | 17 (94) | 5 (28) | 13 (72) |

| Trichoblastic carcinoma | 5 | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 4 (80) | 1 (20) |

| Total | 83 | 9 (11) | 74 (89) | 20 (24) | 63 (76) |

NOS no other specification, EMPD extramammary Paget disease

aPD-L1 is considered positive (+) applying a cut-off of ≥ 1% of tumor cells (TC1–3)

bPD-L1 is considered positive (+) applying a cut-off of ≥ 1% of immune cells (IC1–3)

PD-L1 expression was highly variable depending on the histological subtype (Fig. 1). Sweat gland carcinomas tended to have a higher PD-L1 tumor cell expression (13%, 8/60) compared to other adnexal carcinomas. Among sweat gland carcinomas, PD-L1 was particularly expressed in apocrine carcinomas (40%, 2/5) and in invasive extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) (57%, 4/7). Expression of PD-L1 by tumor cells was found in porocarcinoma (7%, 1/14) and hidradenocarcinoma (9%, 1/11) and was absent in the other types of sweat gland carcinomas. PD-L1 tumor cell expression was observed in one sebaceous carcinoma (6%, 1/18) but was absent in trichoblastic carcinomas.

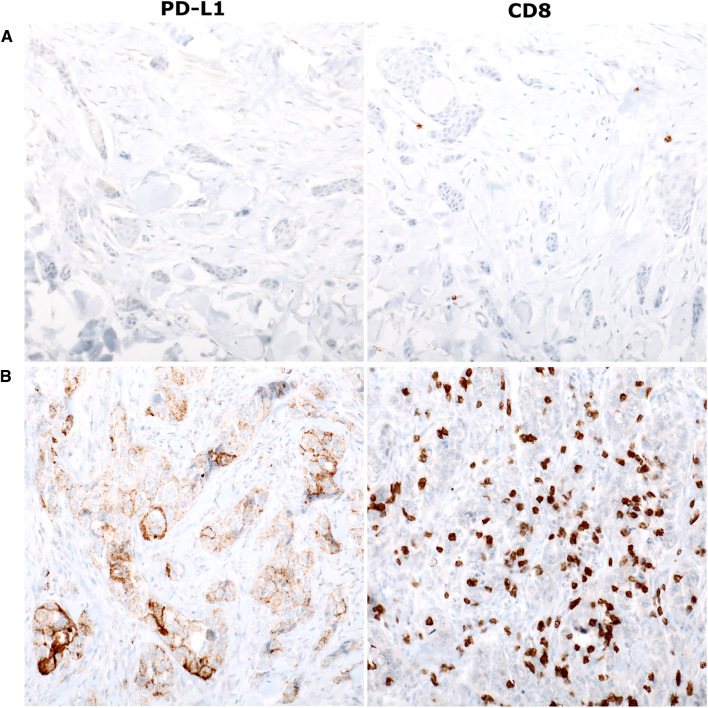

Fig. 1.

Programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression (left panels) and CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) (right panels) (× 200 magnification). a Microcystic adnexal carcinoma with no PD-L1 expression (TC0; IC0) and low infiltrate of CD8+ TIL; b apocrine carcinoma with high PD-L1 expression (IC3), and with high CD8+ TIL

The expression of PD-L1 in the immune cells was significantly more frequent than in tumor cells (p < 0.001). Immune cells with PD-L1 expression (IC1–3) were found in 18% (11/60) of sweat gland carcinomas, 28% (5/18) of sebaceous carcinomas and 80% (4/5) of trichoblastic carcinomas.

In the sweat gland carcinomas, PD-L1 was particularly expressed in the immune environment of invasive EMPD (57%, 4/7) and apocrine carcinomas (20%, 1/5). Expression of PD-L1 by immune cells was found in porocarcinoma (21%, 3/14), hidradenocarcinoma (18%, 2/11) and in one ductal adenocarcinoma NOS (10%, 1/10) and absent in the other types of sweat gland carcinomas.

PD-L1 tumor cell and immune cell expression is associated to stromal CD8+ TIL

We first assessed the frequency of CD8+ TIL in adnexal carcinoma subtypes, both in the tumor and in its stroma (Table 4).

Table 4.

CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in cutaneous adnexal carcinomas

| Intratumoral CD8+ TIL | Stromal CD8+ TIL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higha (%) | Lowb (%) | High (%) | Low (%) | |

| Sweat gland carcinoma | 12 (20) | 48 (80) | 26 (43) | 34 (57) |

| Porocarcinoma | 5 (36) | 9 (64) | 9 (64) | 5 (36) |

| Hidradenocarcinoma | 3 (27) | 8 (73) | 4 (36) | 7 (64) |

| Ductular adenocarcinoma NOS | 1 (10) | 9 (90) | 1 (10) | 9 (90) |

| Microcystic adnexal carcinoma | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 3 (60) | 2 (40) |

| Syringoid eccrine carcinoma | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 1 (20) | 4 (80) |

| Apocrine carcinoma | 1 (20) | 4 (80) | 3 (40) | 2 (60) |

| Invasive EMPD | 2 (28) | 5 (72) | 5 (72) | 2 (28) |

| Digital papillary adenocarcinoma | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) |

| Sebaceous carcinoma | 1 (6) | 17 (94) | 7 (39) | 11 (61) |

| Trichoblastic carcinoma | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 3 (60) | 2 (40) |

| Total | 13 (16) | 70 (84) | 36 (43) | 47 (57) |

aHigh is defined as any with score of “moderate” or “abundant” infiltrates

bLow is defined as those scores of “absent” or “mild”infiltrates as described in the “Materials and methods”

High intratumoral CD8+ TIL were seen in 20% of sweat gland carcinomas, one sebaceous carcinoma (6%) and no trichoblastic carcinoma. Sweat gland carcinomas subtypes with most abundant intratumoral CD8+ TIL were porocarcinoma (36%, 5/14) and hidradenocarcinoma (27%, 3/11). Only one ductal adenocarcinoma NOS, one apocrine carcinoma and two invasive EMPD showed abundant intratumoral CD8+ TIL.

Overall, CD8+ TIL were more abundant in the stroma than in the tumor. High stromal CD8+ TIL were found in 43% of sweat gland carcinomas, 39% of sebaceous carcinomas and 60% of trichoblastic carcinomas. Here again, highest frequencies of high stromal CD8+ TIL were seen in a majority of sweat gland carcinomas: invasive EMPD (72%, 5/7), porocarcinoma (64%, 9/14), microcystic adnexal carcinoma (60%, 3/5), apocrine carcinoma (40%, 3/5), hidradenocarcinoma (36%, 4/11), syringoid eccrine carcinoma (20%, 1/5) and ductal adenocarcinoma NOS (10%, 1/10). Stromal CD8+ TIL were low in digital papillary adenocarcinoma and in adenoid cystic carcinoma.

We then analyzed whether PD-L1 expression by tumor cells (TC) or by immune cells (IC) was associated with high stromal CD8+ TIL (Table 5). Interestingly, in the whole cohort, PD-L1 expression by TC was significantly associated with high stromal CD8+ TILs (p < 0.05). This was particularly the case for sweat gland carcinomas, where all PD-L1 (+) tumors had high stromal CD8+ TIL (p < 0.01). In addition, in the whole cohort, high stromal CD8+ TIL tended to be associated with high expression of PD-L1 by IC (p = 0.072). In sweat gland carcinomas, this association was significant (p < 0.01).

Table 5.

PD-L1 tumor cell and immune cell expression is associated to the importance of stromal CD8+ TIL

| n | PD-L1 TC (+)a | PD-L1 TC (−) | p c | PD-L1 IC (+)a | PD-L1 IC (−) | p c | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD8+ TIL highb | CD8+ TIL lowb | CD8+ TIL highb | CD8+ TIL lowb | CD8+ TIL highb | CD8+ TIL lowb | CD8+ TIL highb | CD8+ TIL lowb | ||||

| Adnexal carcinoma (total) | 83 | 7 | 2 | 29 | 45 | 0.032 | 12 | 8 | 24 | 39 | 0.072 |

| Sweat gland carcinoma | 60 | 7 | 1 | 19 | 33 | 0.009 | 9 | 2 | 17 | 32 | 0.006 |

| Sebaceous carcinoma | 18 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 10 | 0.611 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 0.32 |

| Trichoblastic carcinoma | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | n.a. | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0.60 |

Bold values indicate statistically significant findings

aPD-L1 (+) is defined as > 1% of tumor cells or immune cells demonstrating membranous expression

bStromal CD8+ TILs: high TIL is defined as any with score of “moderate” or “abundant” infiltrates and low TIL is defined as those scores of “absent” or “mild” infiltrates as described in the Methods

cp value by Fisher’s Exact text

PD-L1 expression and metastatic evolution of cutaneous adnexal carcinomas

Follow-up data were available in 47 patients, with a median follow-up time of 30.5 month (range 7–36). Thirteen of the 47 patients developed regional or distant metastatic disease: 2 (2/3, 65%) invasive EMPD, 3 (3/5, 60%) apocrine carcinomas, 2 (2/10, 20%) ductal adenocarcinomas NOS, 3 (3/11, 27%) hidradenocarcinoma, 1 (1/14, 7%) porocarcinoma, 1 (1/5, 20%) trichoblastic carcinoma, and 1 (1/18, 5%) sebaceous carcinoma.

In univariate analysis, factors significantly associated with metastatic evolution were PD-L1 expression by tumor cells (p = 0.0377), the presence of vascular emboli (p = 0.0026), and more advanced T-stage (T2 vs. T1: p = 0.054; T3 vs. T1: p = 0.00275). In multivariate analysis, only T-stage was associated with metastatic evolution (T2 vs. T1: p = 0.044; T3 vs. T1: p = 0.009) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Cox multivariable analysis of factors associated with disease progression (nodal or visceral metastasis) in skin adnexal carcinomas

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable analysis | |||

| PDL1 on tumor cells | 4.0 | 1.1–15 | 0.0377 |

| PDL1 on immune cells | 0.8 | 0.2–3 | 0.75 |

| CD8+ T-cell infiltrate | 0.8 | 0.2–2.5 | 0.65 |

| Age | 1.005 | 0.97–1.04 | 0.78 |

| T2 vs. T1 | 5.4 | 0.96–30 | 0.054 |

| T3 vs. T1 | 11.3 | 2.3–55 | 0.00275 |

| Vascular emboles | 10.3 | 2.3–47 | 0.0026 |

| Multivariable analysis | |||

| PDL1 on tumor cells | 4.1 | 0.6–29 | 0.15 |

| T2 vs. T1 | 6.7 | 1.1–43 | 0.044 |

| T3 vs. T1 | 10.0 | 1.8–57 | 0.009 |

| Vascular emboles | 1.9 | 0.2–15 | 0.55 |

Bold values indicate statistically significant findings

Discussion

Adnexal carcinomas are rare tumors associated with a poor prognosis when they metastasize. There are no consensus recommendations on the management of malignant adnexal tumors and PD-L1 expression has never been reported in these cancers. Many studies have investigated the clinical implications of PD-L1 expression and the immune infiltration in various cancer types [20–24]. Here, we describe for the first time the expression of PD-L1 in a cohort of skin adnexal carcinoma, showing 11% of adnexal carcinoma with PD-L1 expression in more than 1% of tumor cells, 24% of adnexal carcinomas with PD-L1 expression in more than 1% of immune cells of the tumor microenvironment, and a highly variable expression among histological subtypes. PD-L1 expression by tumor cells was more frequent in sweat gland adnexal carcinoma (13%), particularly in apocrine carcinomas (40%) and in invasive extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) (57%). PD-L1 expression by immune cells was more frequent in trichoblastic carcinomas (80%), invasive EMPD (57%), sebaceous carcinomas (28%) and apocrine carcinomas (20%).

In other skin tumors, namely melanoma and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC), PD-L1 expression is also heterogeneous, but seems more frequent than in skin adnexal carcinomas. A heterogeneous expression of PD-L1 has been reported in cutaneous melanomas, within the same tumor, between a primary tumor and its metastasis in the same patient [25], and according to melanoma subtype [17, 26, 27]. Overall, primary cutaneous melanoma expressed PD-L1 in 36–80% cases [17, 27, 28]. In primary cSCC, Schaper et al. recently showed that when applying a cut-off of ≥ 1%, 26.5% of cSCC expressed PD-L1 in the tumour and 60.3% in TILs [29]. Only one study reported the frequent PD-L1 expression in tumor cells (89.9%) and in immune cells (93.9%) in basal cell carcinoma (BCC) [30]. Expression of PD-L1 was heterogeneous between treated BCC and treatment-naive tumor, significantly higher in tumor cells (32% vs. 7%, p = 0.003) and TILs (47% vs. 18%, p = 0.008) of treated BCC. Altogether, our results in adnexal carcinomas show a frequency of PD-L1 tumor cell or immune cell expression close to untreated BCC.

Both cSCC and cutaneous melanoma are partly induced by ultraviolet (UV) radiations, serving as the dominant mutagen. In these tumors, the tumor mutation burden (TMB) is known to be among the highest in human cancers [31, 32]. PD-L1 expression and TMB have been associated in cancer [33], and TMB is now proposed as a biomarker of response to anti-PD1 treatment in cancer [34–36]. Data are lacking in the literature regarding TMB in skin adnexal carcinomas, and regarding the involvement of UV radiation in skin adnexal tumors carcinogenesis. As described in melanoma subtypes, where increased TMB is found in sun-exposed vs. sun-protected areas [37], and where non-sun-induced melanomas (acral, mucosal, uveal) express fewer PD-L1 [26], the heterogeneous PD-L1 expression in skin adnexal carcinoma subtypes may be related to different TMB and different UV radiation involvement.

Sweat gland tumors are morphologically and phenotypically close to mammary tumors [38] and adnexal carcinomas may be mistaken for metastatic adenocarcinoma, mimicking breast or salivary gland cancers [39, 40]. Breast cancers express little PD-L1, with 6.4% of expression in a cohort of 440 invasive ductal carcinomas, while normal breast tissue do not express PD-L1 [41]. In inflammatory breast cancers, PD-L1 expressing TIL were more frequent (66%) [42]. In our cohort, PD-L1 expression, especially in immune cells, seemed higher than the one described in breast cancers.

Recently, no PD-L1 expression was found in 22 intraepithelial extramammary Paget disease using 22C3 clone (as in our study) [43], while we found PD-L1 expression in 4 out of 7 invasive extramammary Paget disease. These findings suggest that tumor cells of extramammary Paget disease may acquire PD-L1 expression together with invasive properties.

A second part of our work focused on CD8+ TIL and PD-L1 expression by immune cells in the tumor microenvironment of skin adnexal carcinomas. All adnexal carcinomas in our cohort had CD8+ TIL, which were more commonly observed in the stroma than in the epithelial elements. PD-L1 expression by tumor cells and by immune cells was significantly associated with the CD8+ TIL density in the cohort, especially in sweat gland carcinomas.

Expression of PD-L1 in tumor cells is thought to be regulated by the tumor microenvironment. Thus, PD-L1 expression is mostly seen at the site of immune infiltration in various cancers [26, 44]. An association between PD-L1 expression in tumors cells and the presence of TIL has been reported in melanoma, lung, breast cancer, cSCC and Merkel cell carcinoma [45–49]. In our study, we showed the same type of association, since PD-L1 expression was significantly more present when the CD8+ T-cell infiltrate was stronger.

T-cell infiltration has been shown to correlate with better prognosis in breast cancer, ovarian cancer, Merkel cell carcinoma, and colorectal adenocarcinoma [50–53]. Regarding melanoma, prognostic value of TIL in primary tumor has also been demonstrated [54, 55]. In AJCC stage III or IV melanomas, CD3+ T-cell or CD8+ T-cell density, and expression of PD-L1 and immune-related genes, appear as putative prognostic biomarkers [15, 56–58].

In our cohort of skin adnexal carcinomas, with the limitations of a retrospective design and of limited number of patients to evaluate prognostic markers in multivariate analysis, PD-L1 expression by tumor cells was associated with the development of metastases during follow-up in univariate analysis but not in multivariate analysis. PD-L1 tumor expression has been reported as a factor of poor prognosis in gastric, breast, renal, and pancreatic cancers [59–62]. On the contrary it was associated with a better prognosis in metastatic melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, HPV-associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, colorectal cancer (in colorectal cancer mismatch repair proficient) and small cell lung cancer [52, 57, 63–65].

There are no guidelines on the management of adnexal tumors, especially for metastatic disease. Available information was described mostly in case reports or short series. Radiotherapy is one of the main therapeutic options, and adnexal carcinomas are considered relatively chemoresistant, although the association of two or three chemotherapeutic agents has led to some response [66–68]. De Iuliis et al. reported 28 therapeutic strategies for metastatic porocarcinoma described in the literature [69]. Furthermore, some successful targeted therapy are described: one eccrine carcinoma responded to tamoxifen [70], two cases were controlled by sunitinib [71] and one apocrine carcinoma was successfully treated by lapatinib [72]. There is currently no published data on anti-PD1 immunotherapy in adnexal carcinomas.

Overall, we showed in a cohort of 83 skin adnexal carcinomas, that 11% had PD-L1 expression in tumor cells and 24% in immune cells of the tumor microenvironment. PD-L1 expression was heterogeneous among subtypes, higher in apocrine carcinomas and in invasive extramammary Paget disease for tumor cell expression, and higher in trichoblastic carcinomas, sebaceous carcinomas, invasive extramammary Paget disease, and apocrine carcinomas for immune cell expression. As PD-L1 expression may be predictive of response to anti-PD1 treatments, our data suggest that PD-1 inhibition therapy is worth investigating in at least some subtypes of skin adnexal carcinomas.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Tumorothèque of Saint Louis hospital for providing tissue material.

Abbreviations

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- APHP

Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris

- BCC

Basal cell carcinoma

- CHRU

Centre hospitalier régional universitaire

- cSCC

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma

- EMPD

Extramammary Paget disease

- IC

Immune cells

- NOS

No other specification

- TC

Tumor cells

- TMB

Tumor mutation burden

- UMR

Unité mixte de recherche

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

LD designed the study, acquired and analyzed data, drafted the work and revised it. AO acquired data and revised the work for important intellectual content. BC analyzed data and revised the work for important intellectual content. LM analyzed data and revised the work for important intellectual content. ADM acquired and analyzed data, did the statistical analysis, and revised the work for important intellectual content. NB-S acquired clinical data and revised the work for important intellectual content. CL acquired clinical data and revised the work for important intellectual content. MB designed the study, acquired and analyzed data, drafted the work, and revised the work for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript version.

Funding

No relevant funding.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

All patients were informed that part of the remaining tissue material could be used for research, and gave their consent according to the Helsinki declaration. Samples were obtained from the Tumorothèque of Saint-Louis Hospital (Tumor bank registration number DC2009.929, Ministry of Health, France).

Ethical standards

According to the bioethics French law of August 6th 2004, applicable at the time of the study, in the context of a retrospective monocentric non-interventional study, additional ethical committee approval was not necessary.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Crowson AN, Magro CM, Mihm MC. Malignant adnexal neoplasms. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(Suppl 2):S93–S126. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardoso JC, Calonje E. Malignant sweat gland tumours: an update. Histopathology. 2015;67(5):589–606. doi: 10.1111/his.12767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez SR, Barr KL, Canter RJ. Rare tumors through the looking glass: an examination of malignant cutaneous adnexal tumors. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(9):1058–1062. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danialan R, Mutyambizi K, Aung P, et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of cutaneous adnexal tumours. J Clin Pathol. 2015;68(12):992–1002. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suchak R, Wang WL, Prieto VG, et al. Cutaneous digital papillary adenocarcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 31 cases of a rare neoplasm with new observations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(12):1883–1891. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31826320ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho VH, Ross MI, Prieto VG, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for sebaceous cell carcinoma and melanoma of the ocular adnexa. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133(8):820–826. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.8.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snow SN, Reizner GT. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the face. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(2 Pt 2):306–311. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70187-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maeda T, Mori H, Matsuo T, et al. Malignant eccrine poroma with multiple visceral metastases: report of a case with autopsy findings. J Cutan Pathol. 1996;23(6):566–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1996.tb01451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waqas O, Faisal M, Haider I, et al. Retrospective study of rare cutaneous malignant adnexal tumors of the head and neck in a tertiary care cancer hospital: a case series. J Med Case Rep. 2017;11(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s13256-017-1212-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hibler BP, Barker CA, Hollmann TJ, et al. Metastatic cutaneous apocrine carcinoma: multidisciplinary approach achieving complete response with adjuvant chemoradiation. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3(3):259–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernardez C, Requena L. Treatment of malignant cutaneous adnexal neoplasms. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109(1):6–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishida Y, Agata Y, Shibahara K, et al. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. EMBO J. 1992;11(11):3887–3895. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, et al. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med. 2002;8(8):793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu P, Wu D, Li L, et al. PD-L1 and survival in solid tumors: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0131403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madore J, Strbenac D, Vilain R, et al. PD-L1 negative status is associated with lower mutation burden, differential expression of immune-related genes, and worse survival in stage III melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(15):3915–3923. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gadiot J, Hooijkaas AI, Kaiser AD, et al. Overall survival and PD-L1 expression in metastasized malignant melanoma. Cancer. 2011;117(10):2192–2201. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M, et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature. 2014;515(7528):563–567. doi: 10.1038/nature14011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dieci MV, Radosevic-Robin N, Fineberg S, et al. Update on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer, including recommendations to assess TILs in residual disease after neoadjuvant therapy and in carcinoma in situ: a report of the International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group on Breast Cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2018;52:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hendry S, Salgado R, Gevaert T, et al. Assessing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in solid tumors: a practical review for pathologists and proposal for a standardized method from the International Immuno-Oncology Biomarkers Working Group: Part 2: TILs in melanoma, gastrointestinal tract carcinomas, non-small cell lung carcinoma and mesothelioma, endometrial and ovarian carcinomas, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, genitourinary carcinomas, and primary brain tumors. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24(6):311–335. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon MJ, Rho YS, Nam ES, et al. Clinical implication of programmed death-ligand 1 expression in tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma in association with intratumoral heterogeneity, human papillomavirus, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Hum Pathol. 2018;80:28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2018.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J, Kim S, Lee HS, et al. Prognostic implication of programmed cell death 1 protein and its ligand expressions in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;149(2):381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee KS, Kwak Y, Ahn S, et al. Prognostic implication of CD274 (PD-L1) protein expression in tumor-infiltrating immune cells for microsatellite unstable and stable colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66(7):927–939. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-1999-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mori S, Motoi N, Ninomiya H, et al. High expression of programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 in lung adenocarcinoma is a poor prognostic factor particularly in smokers and wild-type epidermal growth-factor receptor cases. Pathol Int. 2017;67(1):37–44. doi: 10.1111/pin.12489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim C, Kim EK, Jung H, et al. Prognostic implications of PD-L1 expression in patients with soft tissue sarcoma. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:434. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2451-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madore J, Vilain RE, Menzies AM, et al. PD-L1 expression in melanoma shows marked heterogeneity within and between patients: implications for anti-PD-1/PD-L1 clinical trials. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2015;28(3):245–253. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaunitz GJ, Cottrell TR, Lilo M, et al. Melanoma subtypes demonstrate distinct PD-L1 expression profiles. Lab Investig. 2017;97(9):1063–1071. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2017.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2521–2532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):320–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schaper K, Kother B, Hesse K, et al. The pattern and clinicopathological correlates of programmed death-ligand 1 expression in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(5):1354–1356. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang J, Zhu GA, Cheung C, et al. Association between programmed death ligand 1 expression in patients with basal cell carcinomas and the number of treatment modalities. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(4):285–290. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.5062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reddy BY, Miller DM, Tsao H. Somatic driver mutations in melanoma. Cancer. 2017;123(S11):2104–2117. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harwood CA, Proby CM, Inman GJ, et al. The promise of genomics and the development of targeted therapies for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96(1):3–16. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ng PK, Li J, Jeong KJ, et al. Systematic functional annotation of somatic mutations in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;33(3):450–462 e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357(6349):409–413. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yarchoan M, Hopkins A, Jaffee EM. Tumor mutational burden and response rate to PD-1 inhibition. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(25):2500–2501. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1713444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morrison C, Pabla S, Conroy JM, et al. Predicting response to checkpoint inhibitors in melanoma beyond PD-L1 and mutational burden. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0344-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Besaratinia A, Pfeifer GP. Sunlight ultraviolet irradiation and BRAF V600 mutagenesis in human melanoma. Hum Mutat. 2008;29(8):983–991. doi: 10.1002/humu.20802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piris A, Peng Y, Boussahmain C, et al. Cutaneous and mammary apocrine carcinomas have different immunoprofiles. Hum Pathol. 2014;45(2):320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahalingam M, Nguyen LP, Richards JE, et al. The diagnostic utility of immunohistochemistry in distinguishing primary skin adnexal carcinomas from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin: an immunohistochemical reappraisal using cytokeratin 15, nestin, p63, D2-40, and calretinin. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(5):713–719. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wick MR, Ockner DM, Mills SE, et al. Homologous carcinomas of the breasts, skin, and salivary glands. A histologic and immunohistochemical comparison of ductal mammary carcinoma, ductal sweat gland carcinoma, and salivary duct carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;109(1):75–84. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/109.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Polonia A, Pinto R, Cameselle-Teijeiro JF, et al. Prognostic value of stromal tumour infiltrating lymphocytes and programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in breast cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70(10):860–867. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2016-203990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arias-Pulido H, Cimino-Mathews A, Chaher N, et al. The combined presence of CD20+ B cells and PD-L1+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in inflammatory breast cancer is prognostic of improved patient outcome. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;171(2):273–282. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4834-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karpathiou G, Chaleur C, Hathroubi S, Habougit C, Peoc’h M. Expression of CD3, PD-L1 and CTLA-4 in mammary and extramammary Paget disease. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2018;67:1297–1303. doi: 10.1007/s00262-018-2189-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lyford-Pike S, Peng S, Young GD, et al. Evidence for a role of the PD-1:PD-L1 pathway in immune resistance of HPV-associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2013;73(6):1733–1741. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knol AC, Nguyen JM, Pandolfino MC, et al. PD-L1 expression by tumor cell lines: a predictive marker in melanoma. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27(6):647–655. doi: 10.1111/exd.13526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim H, Kwon HJ, Park SY, et al. Clinicopathological analysis and prognostic significance of programmed cell death-ligand 1 protein and mRNA expression in non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0198634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li X, Li M, Lian Z, et al. Prognostic role of programmed death ligand-1 expression in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Target Oncol. 2016;11(6):753–761. doi: 10.1007/s11523-016-0451-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garcia-Diez I, Hernandez-Ruiz E, Andrades E, et al. PD-L1 expression is increased in metastasizing squamous cell carcinomas and their metastases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:647–654. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000001164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lipson EJ, Vincent JG, Loyo M, et al. PD-L1 expression in the Merkel cell carcinoma microenvironment: association with inflammation, Merkel cell polyomavirus and overall survival. Cancer Immunol Res. 2013;1(1):54–63. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stanton SE, Adams S, Disis ML. Variation in the incidence and magnitude of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer subtypes: a systematic review. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(10):1354–1360. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santoiemma PP, Powell DJ., Jr Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in ovarian cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2015;16(6):807–820. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2015.1040960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Behr DS, Peitsch WK, Hametner C, et al. Prognostic value of immune cell infiltration, tertiary lymphoid structures and PD-L1 expression in Merkel cell carcinomas. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7(11):7610–7621. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.El Sissy C, Marliot F, Haicheur N, et al. Focus on the Immunoscore and its potential clinical implications. Ann Pathol. 2017;37(1):29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.annpat.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Azimi F, Scolyer RA, Rumcheva P, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte grade is an independent predictor of sentinel lymph node status and survival in patients with cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2678–2683. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.8539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomas NE, Busam KJ, From L, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte grade in primary melanomas is independently associated with melanoma-specific survival in the population-based genes, environment and melanoma study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(33):4252–4259. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kakavand H, Vilain RE, Wilmott JS, et al. Tumor PD-L1 expression, immune cell correlates and PD-1+ lymphocytes in sentinel lymph node melanoma metastases. Mod Pathol. 2015;28(12):1535–1544. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2015.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Obeid JM, Erdag G, Smolkin ME, et al. PD-L1, PD-L2 and PD-1 expression in metastatic melanoma: correlation with tumor-infiltrating immune cells and clinical outcome. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5(11):e1235107. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1235107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kluger HM, Zito CR, Barr ML, et al. Characterization of PD-L1 expression and associated T-cell infiltrates in metastatic melanoma samples from variable anatomic sites. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(13):3052–3060. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu F, Feng G, Zhao H, et al. Clinicopathologic significance and prognostic value of B7 homolog 1 in gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94(43):e1911. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guo Y, Yu P, Liu Z, et al. Prognostic and clinicopathological value of programmed death ligand-1 in breast cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0156323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu F, Xu L, Wang Q, et al. Clinicopathological and prognostic value of programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) in renal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(9):14595–14603. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gao HL, Liu L, Qi ZH, et al. The clinicopathological and prognostic significance of PD-L1 expression in pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2018;17(2):95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.hbpd.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Badoual C, Hans S, Merillon N, et al. PD-1-expressing tumor-infiltrating T cells are a favorable prognostic biomarker in HPV-associated head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73(1):128–138. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Droeser RA, Hirt C, Viehl CT, et al. Clinical impact of programmed cell death ligand 1 expression in colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(9):2233–2242. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Toyokawa G, Takada K, Haratake N, et al. Favorable disease-free survival associated with programmed death ligand 1 expression in patients with surgically resected small-cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2016;36(8):4329–4336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gutermuth J, Audring H, Voit C, et al. Antitumour activity of paclitaxel and interferon-alpha in a case of metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18(4):477–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mezger J, Remberger K, Schalhorn A, et al. Treatment of metastatic sweat gland carcinoma by a four drug combination chemotherapy: response in two cases. Med Oncol Tumor Pharmacother. 1986;3(1):29–34. doi: 10.1007/BF02934573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.el-Domeiri AA, Brasfield RD, Huvos AG, et al. Sweat gland carcinoma: a clinico-pathologic study of 83 patients. Ann Surg. 1971;173(2):270–274. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197102000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.De Iuliis F, Amoroso L, Taglieri L, et al. Chemotherapy of rare skin adnexal tumors: a review of literature. Anticancer Res. 2014;34(10):5263–5268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sridhar KS, Benedetto P, Otrakji CL, et al. Response of eccrine adenocarcinoma to tamoxifen. Cancer. 1989;64(2):366–370. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890715)64:2<366::AID-CNCR2820640204>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Battistella M, Mateus C, Lassau N, et al. Sunitinib efficacy in the treatment of metastatic skin adnexal carcinomas: report of two patients with hidradenocarcinoma and trichoblastic carcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(2):199–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hidaka T, Fujimura T, Watabe A, et al. Successful treatment of HER-2-positive metastatic apocrine carcinoma of the skin with lapatinib and capecitabine. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92(6):654–655. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]