Abstract

Vaccines that elicit targeted tumor antigen-specific T-cell responses have the potential to be used as adjuvant therapy in patients with high risk of relapse. However, the responses induced by vaccines in cancer patients have generally been disappointing. To improve vaccine function, we investigated the possibility of exploiting the immunostimulatory capacity of type 1 Natural killer T (NKT) cells, a cell type enriched in lymphoid tissues that can trigger improved antigen-presenting function in dendritic cells (DCs). In this phase I dose escalation study, we treated eight patients with high-risk surgically resected stage II–IV melanoma with intravenous autologous monocyte-derived DCs loaded with the NKT cell agonist α-GalCer and peptides derived from the cancer testis antigen NY-ESO-1. Two synthetic long peptides spanning defined immunogenic regions of the NY-ESO-1 sequence were used. This therapy proved to be safe and immunologically effective, inducing increases in circulating NY-ESO-1-specific T cells that could be detected directly ex vivo in seven out of eight patients. These responses were achieved using as few as 5 × 105 peptide-loaded cells per dose. Analysis after in vitro restimulation showed increases in polyfunctional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that were capable of manufacturing two or more cytokines simultaneously. Evidence of NKT cell proliferation and/or NKT cell-associated cytokine secretion was seen in most patients. In light of these strong responses, the concept of including NKT cell agonists in vaccine design requires further investigation.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00262-017-2085-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Melanoma, Dendritic cell, NKT cell, α-Galactosylceramide, NY-ESO-1

Introduction

Surgical treatment is effective for early stage melanoma, but patients with resected advanced disease have a high risk of relapse. Until recently, the only drug with demonstrated efficacy as adjuvant therapy for this group of patients was interferon-α [1], a compound with broad immunostimulatory function, but substantial associated toxicity [2]. The clinical success of checkpoint blockade in melanoma patients with unresectable or metastatic disease has validated the concept of mobilising the adaptive immune system, particularly T cells, to provide a significant clinical benefit [3–6]. A recent clinical trial of checkpoint blockade with anti-CTLA-4 (ipilimumab) in the adjuvant setting has shown a significant reduction of the relative risk of death [7], opening new avenues for this patient group. Nonetheless, checkpoint blockade can also be associated with toxic side effects due to the broad T-cell response induced, which can include stimulation of autoreactive T cells [8, 9]. New targeted T-cell-mediated immunotherapies with improved toxicity profiles should, therefore, be considered in this clinical setting.

Treatment with antigen-loaded DC-based vaccines has a good safety profile, but issues remain about the potency and general utility of this approach [10]. To improve potency, there has been considerable interest in increasing the stimulatory function of DCs by exposing them to pro-inflammatory cytokines, or triggering activation programmes through pattern recognition receptors. A less explored approach is to provoke specific interactions with stimulatory cells in the local lymphoid environment once the DCs have been injected back into the host. In animal models, it has been shown that type 1 Natural killer T cells (NKT cells) can be exploited to provide a ready source of stimulatory signals to DCs by virtue of their high frequency and semi-activated phenotype [11–14]. These cells show limited T-cell receptor (TCR) variability, with an invariant TCR Vα-chain combined with a restricted Vβ chain repertoire [15–17], and express many features of innate activity typically seen in NK cells. They respond to glycolipids of microbial or endogenous origin in the context of the MHC-like molecule, CD1d [18–20]. The first ligand identified for NKT cells, α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) [21, 22], was found to have anti-tumor effects in mice [23–25], and remains one of the most potent activators of NKT cells yet described.

Injection of α-GalCer rapidly activates NKT cells, which in turn provokes activation of DCs characterized by increased expression of MHC molecules, adhesion molecules and co-stimulatory molecules, and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [26, 27]. If these same DCs present antigenic peptides, strong T-cell responses can be induced [11, 12]. In mice, the anti-tumor activity of DC-based vaccines can be improved by loading α-GalCer together with tumor antigens onto the DCs before injection [28]. While clinical trials have been conducted with DCs loaded with α-GalCer alone, which have provided evidence that NKT cells can be activated in patients with advanced cancer [29–32], no trial has yet explored the possibility of combining α-GalCer with tumor antigens to enhance tumor-specific T-cell responses.

Here, we evaluated such a vaccine design in patients with fully resected melanoma, with the ultimate aim of developing a vaccine that could be used as an adjuvant therapy in this high-risk patient group. To this end, we loaded autologous monocyte-derived DCs with α-GalCer and synthetic long peptides derived from NY-ESO-1, an antigen that is commonly expressed in melanoma [33, 34]. The use of long peptides encompassing the most immunogenic regions of NY-ESO-1 protein obviated the need to preselect patients on the basis of HLA-typing, and also enhanced the chances of stimulating both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [35]. The primary objective was to determine a safe dose level for a planned phase II study evaluating the immune adjuvant properties of α-GalCer by comparing vaccines with and without α-GalCer. We also undertook an analysis of immunological responses, including assessment of NKT cell activation and enumeration of frequencies of peptide-specific T cells in blood before and after vaccination.

Materials and methods

Patient population

This was a single-arm open-label dose escalation study in patients with histologically confirmed, fully resected American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Stage II, III, or IV malignant cutaneous melanoma who were: ≥ 18 years old; no more than 12 months from surgery; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 0–2; and had normal full blood counts and renal and liver function biochemistry. Exclusion criteria were the presence of mucosal or ocular melanoma, prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy within 6 weeks of recruitment, prior immunotherapy, other malignancy in the past 3 years (except non-melanoma skin cancer or in situ cancer of the cervix), active infection, active autoimmune disease, the previous use of long-term immunosuppressive therapy within 6 months, concurrent major organ dysfunction, or unstable medical condition.

Study outline

The study schema is shown in Fig. 1. Eligible patients underwent leukapheresis within 12 weeks of receiving study treatment, during which time the vaccine was prepared. Patients were to receive two cycles of DC vaccine (DCV) with an interval of 28 days ± 48 h. Clinical assessments were undertaken at screening and with each vaccine visit until the end of study (28 days after the 2nd vaccination). Adverse events were recorded from the date of consent until end of the study treatment according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0 (CTCAE v4.0). Blood was collected for analysis of serum cytokines 2 days before treatment was initiated, immediately before each vaccination, and 6 and 24 h after vaccination. For analysis of NKT cells and T cells, blood was collected 2 days before treatment was initiated, immediately before each vaccination, 24 h after vaccination, and 2 and 4 weeks after vaccination. Blood samples were enriched for PBMCs within 6 h of collection, and immediately cryopreserved for later analysis.

Fig. 1.

Study schema. Arrows indicate times when blood samples were collected for serum or PBMCs. Sample collections’ time-point is indicated in days (d) and hours (h)

Treatment

Antigenic peptides and α-GalCer

The DCs were pulsed with two long peptides from NY-ESO-1 (NY-ESO-179–116, GARGPESRLLEFYLAMPFATPMEAELARRSLAQDAPPL and NY-ESO-1118–143, VPGVLLKEFTVSGNILTIRLTAADHR) that include the most immunogenic regions of the protein based on prior clinical studies. Short MHC class I-binding peptides from influenza proteins were included to increase the chances of detecting vaccine-induced T-cell responses. These were peptides from influenza polymerase basic protein 1 (PB-1489–497, TFEFTSFFY), influenza virus matrix 1(M158–66, GILGFVFTL), and influenza virus nucleoprotein (NP265–273, ILRGSVAHK), which bind HLA-A1, -A2, or -A3, respectively; these MHC class I alleles were expected to be common in the population studied. The peptides and α-GalCer were synthesized according to good manufacturing practice (GMP), and authorized by the New Zealand medicines and medical devices safety authority.

Vaccine production

The generation of monocyte-derived DCs and antigen pulsing was conducted under GMP. A Lymphoprep density gradient (Axis Shield, Oslo, Norway) was used to enrich PBMCs from leukapheresis product, followed by a 20% sucrose gradient (Calbiochem, Billerica, MA), and then monocytes were enriched by adherence for 1 h in culture medium consisting of RPMI-1640 (Gibco, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 2% autologous plasma. The non-adherent fraction was removed, the medium replenished, and then the cultures were given fresh medium 24 h later supplemented with 1000 U/ml rhGM-CSF (Genzyme, Lynnwood, Australia) and 1000 U/ml rhIL-4 (Gibco CTS, Life Technologies). The cytokines were added again to the same final concentration in additional medium on day 3. On day 5, the immature DCs generated were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in fresh medium containing a maturation cytokine cocktail of 1000 U/mL interleukin (IL)-1β (CellGenix, Freiberg, Germany), 1000 U/mL IL-6 (Gibco CTS), 1000 U/mL TNF-α (Gibco CTS), and 1 μg/mL PGE2 (Cayman Pharma, Neratovice, Czech Republic). The cell suspension was also supplemented with 100 ng/mL α-GalCer and then immediately split for peptide pulsing. To avoid the possibility of immunodominance of influenza specific responses over those for the tumor antigen, one half of the cells were incubated with 10 µM of the NY-ESO-1 peptides and the other half with 10 µM of the influenza peptides. On day 6, the separate cultures were washed to remove excess antigens, and combined at a ratio of 50:50 to give the final DCV. Sterility was confirmed by negative bacterial cultures and endotoxin < 0.5 EU/mL on the final overnight culture medium. The DCVs were cryopreserved in 90% autologous plasma and 10% DMSO (OriGen Biomedical, Austin, TX) in 2 mL CellSeal closed-system cryogenic vials (Cook General BioTechnology, Indianapolis, IN) using a controlled rate freezer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Released products contained > 70% CD83+ HLA-DR+ cells, and were > 70% viable as determined by flow cytometry on a thawed sample.

Vaccine administration

The cryopreserved vaccine was transported in a dry shipper and thawed using a drybath at 37 °C at the bedside. Prior to intravenous vaccine administration, intradermal test doses were administered consisting of 1 × 105 autologous DCV, and the autologous cryopreservation medium alone as control, to ensure that there was no evidence of an immediate antigen-related wheal and flare reaction (monitored over 15 min). Intravenous administration of vaccine was then via a cannula over 1 min. Patients were kept in the ward for 6 h to be monitored for vital signs and symptoms/adverse events, and then attended for further assessment at 24 h.

Dose escalation

The dose escalation design required two groups of three patients, enrolled sequentially: the first group with a dose of 1 × 106 cells and the second with a dose of 3.4 × 106 cells. Progression to the higher dose would only take place if there were no dose-limiting toxicities. If there was one dose-limiting toxicity in the first group, the second group would receive the first dose level. Two or more dose-limiting toxicities in the first group would trigger discussion with the DMC regarding study termination.

Outcome measures

Safety

The primary safety measure was the occurrence of toxicity (graded according to CTCAE v4.0) which required withdrawal of treatment. The maximum allowable delay in vaccination was 3 weeks. The secondary measures were safety (i) between leukapheresis and vaccine treatment, and (ii) during vaccine treatment phase, with all adverse events coded according to CTCAE v4.0.

Analysis of NKT cells by flow cytometry

Numbers of NKT cells in PBMC were determined by flow cytometry on each sample in duplicate. Antibody staining was in PBS supplemented with 2% fetal calf serum and 0.6 mg/mL human normal immunoglobulin (Intragam P, CSL Behring Pty Ltd, Australia). Staining with antibodies to the CDR3 region of the invariant Vα24-JαQ TCR chain (clone 6B11; BioLegend, San Diego, CA) and CD3 (clone UCHT1; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) was used to identify NKT cells, with Live/Dead fixable blue stain used as a viability dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Analysis was performed on a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and data analyzed using the FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

Analysis of cytokines

Based on the previous studies [29, 36–39], tests for increases in production of 11 cytokines IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, TNF, IL-12p70, IFN-γ, MCP-1, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES, and IP-10 were specified a priori. Additional cytokines measured were IL-1β, IL-1RA, IL-2, IL-5, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-12p40, IL-13, IL-15, IL-17A, Eotaxin, FGF2, G-CSF, GM-CSF, VEGF, PDGF-BB, TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and TGF-β3. Serum samples in triplicate were analyzed by multiplex immunoassays (Bio-Plex Pro Human Cytokine 27-plex, TGF-β 3-plex, and IL-12p40 single-plex) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BioRad, Hercules, CA).

IFN-γ ELISpot assay for peptide-specific T cells and NKT cells

For the detection of IFN-γ-producing T cells and NKT cells in blood, cryopreserved PBMC from all collection time-points were thawed and assessed together. The cells were treated with universal nuclease (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) and rested for at least 2 h in AIM-V medium (Gibco). They were then washed and resuspended in fresh AIM-V, and then, 1–2 × 105 live cells were cultured overnight in the presence of either 10 μM of the individual peptides and 0.5 ng/mL rhIL-7 to quantify antigen-specific T cells by IFN-γ ELISpot as previously described [40], or with 100 ng/mL α-GalCer to quantify NKT cells by IFN-γ ELISpot. The ELISpot plates were pre-coated in-house with anti-IFN-γ antibody (Mabtech, Nacka Strand, Sweden). Analyses were conducted in triplicate, including medium only negative controls. Stimulation of PBMC with 5 μg/mL phytohemagglutinin (PHA; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used as positive control. The ELISpot plates were developed according to the manufacturer’s instructions and read on an AID reader (Autoimmun Diagnostika GmbH, Strassberg, Germany).

Intracellular cytokine staining and detection

Cryopreserved PBMC were thawed and incubated in triplicate with 10 μM of each individual antigenic peptide for 10 days in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% AB serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 50 U/mL IL-2. The cells were then restimulated overnight with the same peptide in the presence of CD28/CD49d (BD Biosciences), 0.3 μg/mL monensin, and 0.5 μg/mL brefeldin A (both Sigma-Aldrich). On the following day, cell cultures were stained with Live/Dead fixable blue dead cell staining reagent and then with anti-CD3-BUV737 (clone UCHT1; BD Biosciences), anti-CD4-BV510 (OKT4), anti-CD8-PerCP-Cy5.5 (HIT8a), anti-CCR7-BV605 (G043H7), and anti-CD45RA-FITC (HI100), all from BioLegend. The cells were then fixed and permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences) and stained with anti-IFN-γ-PE-Cy7 (B27), anti-TNF-BV650 (MAb11), and anti-IL-2-Alexa647 (MQ1-17H12), all from BioLegend.

HLA-A typing

Only patients positive for HLA-A1, -A2, or -A3 were considered for analysis of influenza peptide-specific T-cell responses. HLA types were determined by sequence-based typing on DNA extracted from stored frozen PBMC (New Zealand Blood Service, Auckland, New Zealand).

Statistical analyses

Response to the vaccine was determined for each patient using a permutation test of the difference between the follow-up and baseline means [41]. For each set of comparisons, one-sided family wise error rate (FWER) adjusted p < 0.05 were considered evidence of a response. For NKT cell counts measured by flow cytometry, the mean cell count for cycle 1 and cycle 2 was compared to the mean pre-vaccination cell count. For the IFN-γ ELISPOT analyses, values were adjusted by the mean background count; the mean for each post-vaccination time-point was compared to the mean of the pre-vaccination measures with the FWER adjustment over all time-points. For cytokine analyses, the means of the log values for each post-vaccination time-point were compared to the mean of the log pre-vaccination measures with FWER adjustment across time-points and the 11 pre-specified cytokines. The analysis was repeated for the complete set of 21 measured cytokines, with FWER across all 21. All analyses were carried out in R [42].

Results

Patient characteristics and treatment

Eight patients with histologically proven stage II, III, or IV malignant cutaneous melanoma were enrolled. Full patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. Patients 1-001, 1-002, and 1-003 received the planned two cycles of the level 1 dose of the DCV (1 × 106 cells) with an interval of 4 weeks. Patient 1-004 received the planned two cycles of the level 2 dose of 3.4 × 106 cells. However, patients 1-005 and 1-006 received only one cycle of the level 2 dose due to a temporary unscheduled closure of the manufacturing facility. A further two patients, 1-007 and 1-008, were therefore enrolled and treated with two cycles of the level 2 dose.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Patient ID | Age | Sex | Type of melanoma | Cancer stage at study entry | Previous therapy | ECOG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-001 | 48 | M | Cutaneous | IIIB | Surgery, radiotherapy | 0 |

| 1-002 | 60 | M | Cutaneous | IV | Surgery | 0 |

| 1-003 | 62 | M | Cutaneous | IIIB | Surgery | 0 |

| 1-004 | 55 | M | Cutaneous | IIIB | Surgery, radiotherapy | 0 |

| 1-005 | 64 | M | Cutaneous | IIIC | Surgery, radiotherapy | 0 |

| 1-006 | 46 | M | Cutaneous | IIB | Surgery | 0 |

| 1-007 | 40 | M | Cutaneous | IV | Surgery, radiotherapy | 0 |

| 1-008 | 67 | F | Cutaneous | IIIA | Surgery | 0 |

Toxicity

The vaccine treatment was well tolerated across the whole patient cohort (Table 2), with no dose-limiting toxicities observed. One patient experienced grade 2 flu-like symptoms and two other patients developed melanoma-unrelated skin diseases (solar keratosis and squamous cell carcinoma). Two patients on dose level 2 experienced various symptoms of nausea, headache, and fatigue (grade 1).

Table 2.

Adverse events recorded between the start of treatment and the end of study

| Patient ID | DCV dose level | Time of adverse event (AE) | AE category | AE grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-001 | 1 | No AEs | ||

| 1-002 | 1 |

Cycle 1, day 3 Cycle 1, day 3 Cycle 1, day 3 Cycle 2, day 3 |

Flu-like symptoms Headache Insomnia Flu-like symptoms |

1 1 1 2 |

| 1-003 | 1 |

End of study End of study End of study |

Toothache Tooth infection Solar keratosis |

1 1 2 |

| 1-004 | 2 | Cycle 2, day − 2 | Common cold | 1 |

| 1-005 | 2 | No AEs | ||

| 1-006 | 2 |

Cycle 2, day − 2 Cycle 2, day − 3 |

Nasal congestion Sore throat |

1 1 |

| 1-007 | 2 |

Cycle 1, day 2 Cycle 1, day 2 Cycle 2, day − 2 Cycle 2, day 2 |

Nausea Headache Lethargy Headache |

1 1 1 1 |

| 1-008 | 2 |

Cycle 1, day 1 Cycle 1, day 2 Cycle 2, day − 2 Cycle 2, day − 2 Cycle 2, day 1 Cycle 2, day 1 Cycle 2, day 1 |

Dysgeusia Fatigue Nasal congestion Squamous cell carcinoma (lip) Dizziness Nausea Dysgeusia |

1 1 1 2 1 1 1 |

NKT cell frequency and function

Blood samples were collected for flow cytometric analysis of NKT cells 2 days before treatment was initiated, and then for each cycle approximately 2 h before injection on the day of vaccination (day 1), and on days 2, 15, and 29 after vaccination (schema in Fig. 1). Example plots are shown in Supplementary Figure 1. Frequencies fluctuated throughout the observation period in most patients (Fig. 2a). Using statistical tests that included adjustment for FWER, significant increases in peripheral NKT cell numbers over baseline were observed in patients 1-001 (both cycles) 1-004 (both cycles), and 1-005 (for the one cycle received). Such increases in the days to weeks after administration of α-GalCer-loaded DCs are consistent with the previous reports, although the changes seen here were minor [29–32]. In addition, changes in the functional status of NKT cells were assessed using IFN-γ ELISpot after 18 h of restimulation with α-GalCer in vitro (examples are shown in Supplementary Figure 2). Numbers of IFN-γ-secreting cells increased post-vaccination in the three patients with increased frequency, and also in patient 1-002 (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of immunologic responses to vaccination. a Analysis of NKT cell frequency in patients over the course of the study. Points shown (open symbols) are the percentage of NKT cells in each of the duplicate samples at each sampled time-point, with mean values (closed symbols) shown as line graphs. Lines V1 and V2 indicate the two vaccination times. Statistically significant increases between post-vaccination measures and baseline (days − 2 and 0) are indicated by * for FWER corrected p < 0.05. b Analysis of NKT cell frequency in PBMCs ex vivo by IFN-γ ELISpot in response to α-GalCer. Points (open symbols) are numbers of IFN-γ spot forming units (SFC) in triplicate samples at each time-point, with mean values (closed symbols) plotted as line graphs. Statistically significant differences between post-vaccination time-points and baseline are indicated by * for FWER corrected p < 0.05. c Analysis of serum cytokines. Heat map indicates serum values in post-vaccination samples that were greater than two standard deviations above (pink) or below (blue) baselines levels. Upper panels show pre-specified cytokines that were above level of detection; lower panel show post hoc analysis of cytokines that were above level of detection. Statistically significant increases between post-vaccination measures and baseline are indicated by * for FWER corrected p < 0.05. Cytokines where this was greater than two standard deviations are marked red. d Upper panels show analysis of frequency of NY-ESO-1118–143-specific cells in PBMCs by ex vivo IFN-γ ELISpot. Points (open symbols) are numbers of SFC in triplicate samples at each time-point, with mean values (closed symbols) plotted as line graphs. Statistically significant increases between post-vaccination measures and baseline are indicated by * for FWER corrected p < 0.05. Middle and lower panels show flow cytometric analysis of IFN-γ+ cells after 10 days of restimulation with NY-ESO-1118–143 long peptide, with gating on CD4+ T cells (middle) or CD8+ T cells (lower). Points (open symbols) are percentages of IFN-γ+ cells in triplicate PBMC samples, with mean values (closed symbols) plotted as line graphs. Statistically significant increases between background-subtracted post-vaccination measures and baseline are indicated by * for FWER corrected p < 0.05. e As in d, except showing analysis of responses to NY-ESO-179–116 long peptide. f Flow cytometric analysis of IFN-γ+, TNF+ or IL-2+ cells after 10 days of restimulation on indicated long peptides, with gating on CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. Heat map indicates frequencies in post-vaccination samples that were greater than three standard deviations above pre-vaccination (pre) baselines levels. Statistically significant increases between post-vaccination measures and baseline are indicated by * for FWER corrected p < 0.05. Cytokines where this was greater than three standard deviations are marked red

The in vivo activation of NKT cells with α-GalCer has previously been associated with the release of measurable quantities of cytokines into the circulation [29, 31, 32], occurring within hours of administration. We therefore tested for increases in a pre-specified set of cytokines based on these earlier studies (IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, TNF, IL-12p70, IFN-γ, MCP-1, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES, and IP-10). Changes in cytokine levels that were greater than two standards deviations from baseline were evident in all patients (Fig. 2c). Two of the pre-specified cytokines, IL-4 and IL-10, were undetectable in all patients. The largest changes observed were increased levels, mostly occurring within 24 h of vaccine administration. Using statistical tests that included adjustment for FWER, significant increases in at least one cytokine were observed in patients 1-002, 1-003, 1-004, 1-006, and 1-008 (indicated with asterisk in Fig. 2c). The number of cytokines involved varied among patients, with patient 1-003 displaying the greatest range with increased levels of 9 out of the 11 pre-specified cytokines. Because these cytokines were measured with commercial multiplex kits, data were generated for a further 20 cytokines. Post hoc analyses were therefore conducted across all of the cytokines measured, and showed statistically significant increases in five additional cytokines for patient 1-003 (IL-1RA, IL-8, IL-17A, G-CSF, and VEGF). Overall, the most commonly increased cytokines were IP-10, a known IFN-γ-induced protein, the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6, and the chemokines MCP-1 and MIP-1β that regulate migration and infiltration of immune cells such as monocytes/macrophages and NK cells. Profiles of cytokine release for these four cytokines for each of the patients are shown in Supplementary Figure 3.

Peptide-specific T-cell responses

The induction of peptide-specific T-cell responses was assessed in PBMC directly ex vivo by IFN-γ-ELISpot analysis. Statistically significant increases in cells producing IFN-γ in response to peptide NY-ESO-1118–143 were observed in at least one post-vaccination sample in seven of the eight patients (1-002, 1-003, 1-004, 1-005, 1-006, 1-007, and 1-008) (Fig. 2d). Patients 1-003 and 1-006 had NY-ESO-1118–143-responsive cells at baseline, suggesting pre-existing immune responses to NY-ESO-1 protein, with frequencies increasing further after the first round of vaccination. However, for patient 1-003, the frequency then dropped to below pre-vaccination levels by day 29, but rebounded again after the second vaccine; patient 1-006 was not re-vaccinated. No statistically significant responses to the second NY-ESO-1 peptide were detected in any patients by this ex vivo assay (Fig. 2e).

The T-cell response was also investigated following restimulation on peptides for 10 days, with flow cytometry used to determine whether peptide-stimulated cytokine-secreting cells were CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. Three cytokines were assessed, IFN-γ, TNF, or IL-2. Of these, IFN-γ was generally expressed in a higher percentage of peptide-reactive cells, so statistical tests with adjustment for FWER were conducted only on IFN-γ-producing T cells. Like the ELISpot data, this analysis showed increases in peptide-reactive cells after vaccination in the majority of patients, with some clear overlap between the data sets. For peptide NY-ESO-1118–143, significant increases IFN-γ-producing cells were seen in patients 1-002, 1-006, 1-007, and 1-008; all had been responders to this peptide by the ELISpot analysis. Interestingly, all the cytokine-secreting cells detected were CD4+ T cells. For patients 1-003 and 1-004, where responses had also been identified by ELISpot, small increases in cytokine-secreting CD4+ T cells were observed after restimulation that did not reach statistical significance. In patient 1-001, where a non-significant increase of NY-ESO-1118-143-reactive cells had previously been observed by ELISpot, restimulation did reveal peptide-reactive cells, which may reflect the enhanced sensitivity of the restimulation assay. Again, the reactive cells were all CD4+ T cells. One notable difference from the ELISpot data for this peptide was the failure to detect peptide-reactive cells after restimulation in patient 1-005, although the response detected by ELISpot in this patient had been very weak.

Notably, cells reactive to the second peptide, NY-ESO-179–116, were detected in post-vaccination samples after restimulation in patients 1-002, 1-004, and 1-006 (Fig. 2e). Again, this may reflect vaccine-induced responses of low cell frequency in these individuals. The reactive cells were all CD4+ T cells.

To capture trends revealed by analysis of release of all three cytokines, we also conducted tests where a vaccine-induced response was defined as an increase in cytokine-producing cells (involving two or more cytokines) in at least one post-vaccine sample that was more than three standard deviations above the baseline mean for each person; the cytokine response also had to involve ≥ 1% of all CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, respectively, at each time-point. By these criteria, plotted as a heat map in Fig. 2f, patients 1-001, 1-002, 1-004, 1-007, and 1-008 all had CD4+ T-cell responses to NY-ESO-1118-143, while patients 1-002, 1-003, 1-004, 1-006, and 1-008 had CD4+ T-cell responses to NY-ESO-179–116. Of note, CD8+ T-cell responses to NY-ESO-179–116 were also detected by this analysis in patients 1-003 and 1-004. Some increases in cytokine-producing cells CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were seen in samples taken only one day after injection, suggesting either the presence of low-level pre-existing response, or that the vaccine had already initiated changes in restimulatory capacity. Overall, only patient 1-005 failed to respond to NY-ESO-1 in this analysis.

Retrospective HLA-typing showed that four patients expressed HLA*A02:01 (1-002, 1-003, 1-004 and 1-008), two patients expressed HLA*A01:01 (1-005 and 1-007), while none expressed HLA*A03:01. Theoretically, these alleles should permit CD8+ T-cell responses to the short influenza peptides that were also included in the vaccines, enabling further evaluation of vaccine activity. However, none of these patients had influenza peptide-reactive CD8+ T cells at baseline, measured by any of the tests above; nor were de novo CD8+ T-cell responses seen after vaccination.

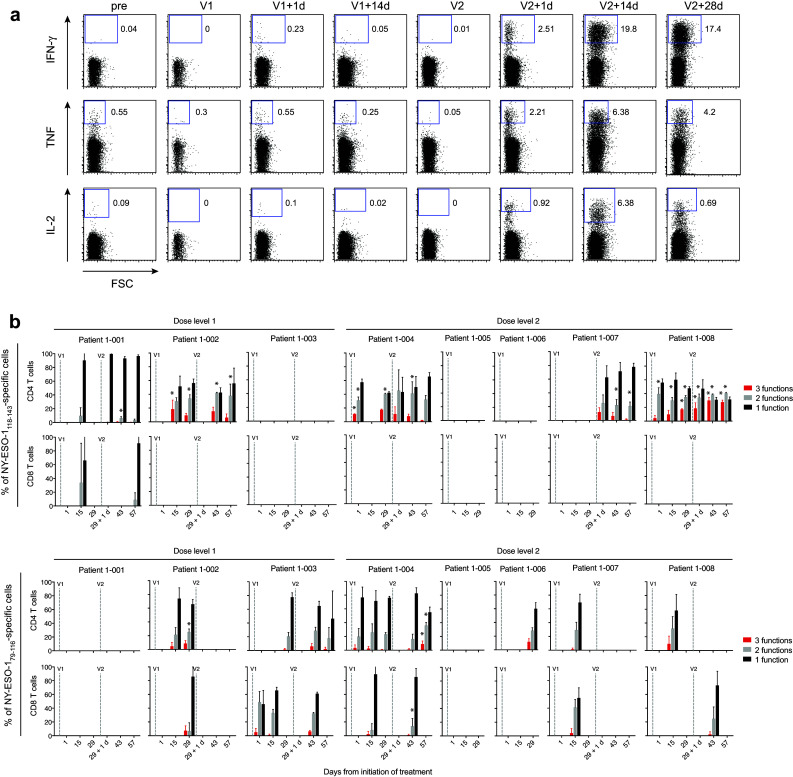

Assessment of polyfunctionality in induced T-cell responses

The flow cytometry data were analyzed for evidence of polyfunctionality, defined here as a population of cells secreting IFN-γ and at least one other cytokine simultaneously (Fig. 3). The initial analysis was conducted only on post-vaccination time-points where the frequency of IFN-γ+ NY-ESO-1-specific T cells was higher than pre-vaccine levels by at least three standard deviations, which included all patients except 1-005. Polyfunctional CD4+ T cells were observed in 34 out of 35 time-points tested, and polyfunctional CD8+ T cells were observed in 10 out of 10 time-points tested. Applying statistical analysis with correction for multiple comparisons, 5 out of 8 patients had statistically significant increases in polyfunctional NY-ESO-1-specific T cells over baseline as a result of vaccination (patients 1-001, 1-002, 1-004, 1-007, and 1-008; indicated with asterisk in Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Polyfunctionality analysis of NY-ESO-1-specific T cells after 10 day restimulation with NY-ESO-1 peptides. a Representative flow cytometry plots of NY-ESO-1118–143-reactive CD4+ T cells secreting IFN-γ, TNF and IL-2 from patient 1-007. b Percentages of cells expressing 1, 2, or 3 cytokines (functions) at once at the indicated time-points. Mean values ± SEM (standard error of the mean) for triplicates samples are shown for the indicated peptide-reactive cells. Statistically significant increases of bi- or tri-functional T-cell responses between post-vaccination measures and baseline are indicated by * for FWER corrected p < 0.05

Discussion

At the outset of this phase I trial, there had been no previous clinical studies where antigenic peptides and the immune-modulating agent α-GalCer had been incorporated into the same cellular vaccine. Here, we included α-GalCer along with long peptide sequences from the tumor antigen NY-ESO-1, as well as short HLA-A-binding peptide sequences from influenza virus antigens. In doing so, we considered the possibility that we might observe some immune-related toxicity due to the mobilization of many immune effector cells, including the sizeable NKT cell population itself. For this reason, we undertook a dose escalation safety study, starting at relatively low cell doses compared to more recent studies of DC vaccines. We report no significant toxicities after injections of 1 × 106 cells, or 3.4 × 106 cells. A further increase in dose, to 10 × 106 cells, has now been completed with no dose-limiting toxicities in a second phase to this study, not reported here, where vaccines with or without α-GalCer are currently being compared in a randomized trial. We also report here that vaccines incorporating α-GalCer can induce NKT cell activation, and that peptide-specific T-cell responses can be induced, most predominantly CD4+ T-cell responses (and to a lesser extent CD8+ T-cell responses) to NY-ESO-1.

In a strategy to limit immunodominance, which may have led to an undesirable scenario in which a therapeutically desirable anti-tumor response was nullified, we loaded the peptides from the viral and tumor antigens onto separate α-GalCer-loaded DCs before combining them to form the final vaccine. Therefore, while the effective doses for α-GalCer-loaded cells at the different levels were indeed 1 × 106 cells and 3.4 × 106 cells, respectively, for each of the antigens used the effective doses were reduced by one half. It is therefore significant that we were able to detect increases in T cells specific for a tumor antigen after injecting as few as 5 × 105 peptide-loaded DCs.

Significant increases in peripheral NKT cells were observed after vaccination in three patients, and these same patients showed increased post-vaccination frequencies of IFN-γ+ cells after PBMC were restimulated with α-GalCer. An additional patient showed increased counts of IFN-γ+ α-GalCer-reactive cells, but without significant changes to frequency in blood. The release of cytokines into serum was examined as another indirect measure of NKT cell activation. Five out of the eight patients showed significant increases in at least 1 of 11 pre-specified cytokines chosen on the basis of the previous studies of α-GalCer in patients, either injected as a free agent, or loaded onto DCs [29, 31]. Like these studies, we found no strong association between vaccination and release of any one cytokine, although increases in IP-10, a known IFN-γ-induced protein, the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6, and the chemokines MCP-1 and MIP-1β were more commonly observed. A notable feature was a tendency to release multiple cytokines, indicative of a strong immune event, although this was not seen after both rounds of vaccination in any one patient, and nor was this preferentially associated with any vaccination round. The patients in which release of multiple cytokines was observed (1-002, 1-003, and 1-004, and to a lesser extent, 1-006 and 1-008) were mostly distinct from the patients with post-vaccination increases in IFN-γ+ α-GalCer-reactive cell counts (1-001, 1-002, 1-004, and 1-005). Without a correlation between these readouts, it is not possible to attribute release of cytokines to NKT cell activation with any confidence, although we are not aware of such significant cytokine release after DC vaccination without inclusion of an adjuvant. This discordance between changes in α-GalCer reactivity and cytokine release might reflect inter-individual functional diversity in NKT cells, which can be altered further in cancer patients [29], or the low vaccine doses inducing NKT cell activation at the lower limit of detection. The previous clinical studies have typically shown sharp decreases in NKT cell frequency within 24 h of exposure to α-GalCer (whether as a free agent or loaded on DCs), with the frequency then rebounding to commonly reach higher than pre-treatment levels over the following days to weeks. We did not see any such a dip in frequency in the post-vaccination period in any patient, perhaps again suggesting only low levels of NKT cell activation were achieved at the doses used, with the previous studies using at least 5 × 106 α-GalCer-loaded DC per cycle [29, 43], or using immature DCs [30–32]. In addition, the strategies used to detect NKT cell frequency in blood by flow cytometry have not been consistent between clinical studies. We used the 6B11 antibody clone, which detects the CDR3 region of TCR Vα24-JαQ chain that is a common feature of the TCR of human type I NKT cells [44], whereas others have used anti-TcR-Vα24 and anti-TcR-Vβ11 monoclonal antibodies, or α-GalCer-loaded CD1d tetramers. It is possible that NKT cells without the canonical TCR rearrangement respond to α-GalCer in some patients, which could mean analyses with 6B11 under-represent the extent of NKT cell expansion induced. Notwithstanding these limitations in detecting NKT cell activation, we could find no association between the presence or quality of NKT cell responses and either baseline NKT cell frequency or DC vaccine dose. Nonetheless, the data do suggest that some NKT cell activation had taken place in response to vaccination, with only patient 1-007 not exhibiting a significant response by any method.

Increases in frequency of peripheral T cells to the long NY-ESO-1 peptides were detected directly ex vivo by IFN-γ ELISpot in seven out of the eight patients treated, with most responding to the NY-ESO-1118–143 peptide. There are only a few other reports [45, 46] where NY-ESO-1-specific T-cell responses have been similarly detected without requiring several days of in vitro restimulation on antigen. When we did restimulate for 10 days on peptide, an even broader response to vaccination was evident, with increases in cytokine-producing cells now observed to the second NY-ESO-1 peptide (NY-ESO-179–116) in some patients. Interestingly, the significant responses against NY-ESO-11118–143 were predominantly CD4+ T-cell-mediated, which is consistent with a recent study of responses to an NY-ESO-1 protein vaccine, where CD4+ T-cell responses were also seen to this region of the protein. In this same study, CD8+ T-cell responses were largely limited to a range including amino acids 79–116 [47]. We also observed CD8+ T cells reactive to this peptide region after vaccination in two patients, with increases above three standard deviations of baseline levels seen after restimulation (although not significant by more rigorous analysis with adjustment for FWER). It remains unclear why increases in CD8+ T cells were only seen in these two patients; analysis with peptide binding prediction tools did not reveal any epitopes with exceptional HLA class I-binding characteristics that were unique to these patients (data not shown).

Perhaps surprisingly, responses to the influenza virus-derived peptide antigens, which we anticipated would be CD8+ T-cell responses restricted to HLA-A1, -A2, or -A3, were not detected. This is particularly intriguing for the peptide M158–66, which has been shown to be immunogenic in healthy subjects when loaded onto mature DC [48]. It is possible that the nature of the antigen loading had a bearing on the strength of immune responses induced. The longer NY-ESO-1 peptides need processing with DCs before being presented via MHC molecules to T cells, and may therefore have to transit via intracellular pathways that facilitate prolonged antigen-presentation [49]. In contrast, short MHC-binding influenza peptides may be more rapidly lost after the cells were injected.

Overall, the large majority of our patients had both detectable NKT cell activity (change of frequency and/or release of multiple cytokines into the serum) as well as demonstrable peptide-specific T-cell responses after vaccination. Only patient 1-007 showed evidence of a T-cell response with a little evidence of NKT cell activation, although this T-cell response could only be detected after restimulation. Interestingly, five out of eight patients had statistically significant increases in polyfunctional NY-ESO-1-specific T cells that secrete IFN-γ in combination with TNF and/or IL-2 [50]. Polyfunctional T-cell responses have been associated with immune control of persistent viral infections, and there is now interest in determining whether they play a protective role in cancer [51] with anti-tumor T-cell responses now commonly characterized for more than simply the secretion of IFN-γ [47, 51–54].

To summarize, we have shown the safety and significant immunogenicity of DC vaccines loaded with the immune adjuvant α-GalCer and antigenic peptides, most notably polyfunctional T-cell responses to long peptides from the tumor antigen NY-ESO-1. The specific contribution of α-GalCer to the size and quality of T-cell responses will be addressed in a randomized two-arm phase II study, now recruiting.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Hugh Green Cytometry Core for flow cytometry support.

Abbreviations

- α-GalCer

α-Galactosylceramide

- AE

Adverse event

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- CDR3

Complementary determining region 3

- CTCAE

Common terminology criteria for adverse events

- DCV

Dendritic cell vaccine

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status

- FGF2

Fibroblast growth factor 2

- FWER

Family wise error rate

- IP-10

IFN-γ-inducible protein-10

- M1

Influenza virus matrix protein 1

- MCP-1

Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- MIP

Macrophage inflammatory protein

- NKT cell

Natural killer T cell

- NP

Influenza virus nucleoprotein

- NY-ESO-1

New York esophageal squamous cell carcinoma-1

- PB-1

Influenza virus protein basic-1

- PDGF-BB

Platelet-derived growth factor BB

- PGE2

Prostaglandin E2

- RANTES

Regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted

Author contributions

Olivier Gasser developed the cellular methodology and performed the immunogenicity analyses. Katrina J. Sharples prepared the statistical plan and performed the analysis. Catherine Barrow chaired the trial management committee, oversaw patient recruitment and treated patients. Geoffrey M. Williams, P. Rod Dunbar, and Margaret A. Brimble developed the synthetic methodology and manufactured GMP grade peptides. Evelyn Bauer and Brigitta Mester developed the methodology and manufactured the cellular vaccine to GMP standards. Graham Caygill, Jeremy Jones, Colin M. Hayman, and Gavin F. Painter developed the synthetic methodology and manufactured α-GalCer to GMP standards. Catherine E. Wood, Marina Dzhelali, and Robert Weinkove provided local clinical support. Victoria A. Hinder, Jerome Macapagal, Monica McCusker, Catherine E. Wood, Marina Dzhelali, Catherine Barrow, Katrina J. Sharples, and Michael P. Findlay undertook clinical project development, management, analysis and reporting. Olivier Gasser, Katrina J. Sharples, P. Rod Dunbar, and Ian F. Hermans analyzed the immunological data and wrote the manuscript, with input from the other authors. Catherine Barrow, Katrina J. Sharples, Michael P. Findlay, P. Rod Dunbar, and Ian F. Hermans conceived and designed the study.

Funding

This work was funded by Health Research Council programme Grant 10/667 and the Health Research Council of New Zealand IROF fund 14/1003.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval and ethical standards

The study was approved by the Northern B Health and Disability Ethics Committee (Ref 13/NTB/5) and registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12612001101875). The study was monitored by an independent Data Monitoring Committee appointed by the Health Research Council of New Zealand.

Informed consent

All patients gave written informed consent.

Footnotes

Olivier Gasser, Katrina J. Sharples, and Catherine Barrow have contributed equally to this study.

References

- 1.Kirkwood JM, Strawderman MH, Ernstoff MS, Smith TJ, Borden EC, Blum RH. Interferon alfa-2b adjuvant therapy of high-risk resected cutaneous melanoma: the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial EST 1684. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(1):7–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lens MB, Dawes M. Interferon alfa therapy for malignant melanoma: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(7):1818–1825. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC, Akerley W, van den Eertwegh AJ, Lutzky J, Lorigan P, Vaubel JM, Linette GP, Hogg D, Ottensmeier CH, Lebbe C, Peschel C, Quirt I, Clark JI, Wolchok JD, Weber JS, Tian J, Yellin MJ, Nichol GM, Hoos A, Urba WJ. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD, Schadendorf D, Dummer R, Smylie M, Rutkowski P, Ferrucci PF, Hill A, Wagstaff J, Carlino MS, Haanen JB, Maio M, Marquez-Rodas I, McArthur GA, Ascierto PA, Long GV, Callahan MK, Postow MA, Grossmann K, Sznol M, Dreno B, Bastholt L, Yang A, Rollin LM, Horak C, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(1):23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, Dutriaux C, Maio M, Mortier L, Hassel JC, Rutkowski P, McNeil C, Kalinka-Warzocha E, Savage KJ, Hernberg MM, Lebbe C, Charles J, Mihalcioiu C, Chiarion-Sileni V, Mauch C, Cognetti F, Arance A, Schmidt H, Schadendorf D, Gogas H, Lundgren-Eriksson L, Horak C, Sharkey B, Waxman IM, Atkinson V, Ascierto PA. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):320–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, O’Day S, Weber J, Garbe C, Lebbe C, Baurain JF, Testori A, Grob JJ, Davidson N, Richards J, Maio M, Hauschild A, Miller WH, Jr, Gascon P, Lotem M, Harmankaya K, Ibrahim R, Francis S, Chen TT, Humphrey R, Hoos A, Wolchok JD. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2517–2526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eggermont AM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob JJ, Dummer R, Wolchok JD, Schmidt H, Hamid O, Robert C, Ascierto PA, Richards JM, Lebbe C, Ferraresi V, Smylie M, Weber JS, Maio M, Bastholt L, Mortier L, Thomas L, Tahir S, Hauschild A, Hassel JC, Hodi FS, Taitt C, de Pril V, de Schaetzen G, Suciu S, Testori A. Prolonged survival in stage III melanoma with ipilimumab adjuvant therapy. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1845–1855. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, Connell LC, Schindler K, Lacouture ME, Postow MA, Wolchok JD. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(12):2375–2391. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weber JS, Kahler KC, Hauschild A. Management of immune-related adverse events and kinetics of response with ipilimumab. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2691–2697. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coffman RL, Sher A, Seder RA. Vaccine adjuvants: putting innate immunity to work. Immunity. 2010;33(4):492–503. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujii S, Shimizu K, Smith C, Bonifaz L, Steinman RM. Activation of natural killer T cells by alpha-galactosylceramide rapidly induces the full maturation of dendritic cells in vivo and thereby acts as an adjuvant for combined CD4 and CD8 T cell immunity to a coadministered protein. J Exp Med. 2003;198(2):267–279. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hermans IF, Silk JD, Gileadi U, Salio M, Mathew B, Ritter G, Schmidt R, Harris AL, Old L, Cerundolo V. NKT cells enhance CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses to soluble antigen in vivo through direct interaction with dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2003;171(10):5140–5147. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leslie DS, Vincent MS, Spada FM, Das H, Sugita M, Morita CT, Brenner MB. CD1-mediated gamma/delta T cell maturation of dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;196(12):1575–1584. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vincent MS, Leslie DS, Gumperz JE, Xiong X, Grant EP, Brenner MB. CD1-dependent dendritic cell instruction. Nat Immunol. 2002;3(12):1163–1168. doi: 10.1038/ni851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lantz O, Bendelac A. An invariant T cell receptor alpha chain is used by a unique subset of major histocompatibility complex class I-specific CD4+ and CD4−8− T cells in mice and humans. J Exp Med. 1994;180(3):1097–1106. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masuda K, Makino Y, Cui J, Ito T, Tokuhisa T, Takahama Y, Koseki H, Tsuchida K, Koike T, Moriya H, Amano M, Taniguchi M. Phenotypes and invariant alpha beta TCR expression of peripheral V alpha 14 + NK T cells. J Immunol. 1997;158(5):2076–2082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prussin C, Foster B. TCR V alpha 24 and V beta 11 coexpression defines a human NK1 T cell analog containing a unique Th0 subpopulation. J Immunol. 1997;159(12):5862–5870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattner J, Debord KL, Ismail N, Goff RD, Cantu C, 3rd, Zhou D, Saint-Mezard P, Wang V, Gao Y, Yin N, Hoebe K, Schneewind O, Walker D, Beutler B, Teyton L, Savage PB, Bendelac A. Exogenous and endogenous glycolipid antigens activate NKT cells during microbial infections. Nature. 2005;434(7032):525–529. doi: 10.1038/nature03408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu D, Xing GW, Poles MA, Horowitz A, Kinjo Y, Sullivan B, Bodmer-Narkevitch V, Plettenburg O, Kronenberg M, Tsuji M, Ho DD, Wong CH. Bacterial glycolipids and analogs as antigens for CD1d-restricted NKT cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(5):1351–1356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408696102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou D, Mattner J, Cantu C, 3rd, Schrantz N, Yin N, Gao Y, Sagiv Y, Hudspeth K, Wu YP, Yamashita T, Teneberg S, Wang D, Proia RL, Levery SB, Savage PB, Teyton L, Bendelac A. Lysosomal glycosphingolipid recognition by NKT cells. Science. 2004;306(5702):1786–1789. doi: 10.1126/science.1103440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akimoto K, Natori T, Morita M. Synthesis and stereochemistry of agelasphin-9b. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:5593–5596. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)73890-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Natori T, Koezuka Y, Higa T. Agelasphins, novel alpha-galactosylceramides from the marine sponge agelas mauritianus. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:5591–5592. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)73889-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi E, Motoki K, Uchida T, Fukushima H, Koezuka Y. KRN7000, a novel immunomodulator, and its antitumor activities. Oncol Res. 1995;7(10–11):529–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morita M, Motoki K, Akimoto K, Natori T, Sakai T, Sawa E, Yamaji K, Koezuka Y, Kobayashi E, Fukushima H. Structure-activity relationship of alpha-galactosylceramides against B16-bearing mice. J Med Chem. 1995;38(12):2176–2187. doi: 10.1021/jm00012a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaguchi Y, Motoki K, Ueno H, Maeda K, Kobayashi E, Inoue H, Fukushima H, Koezuka Y. Enhancing effects of (2S,3S,4R)-1-O-(alpha-d-galactopyranosyl)-2-(N-hexacosanoylamino)-1,3,4-octadecanetriol (KRN7000) on antigen-presenting function of antigen-presenting cells and antimetastatic activity of KRN7000-pretreated antigen-presenting cells. Oncol Res. 1996;8(10–11):399–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitamura H, Iwakabe K, Yahata T, Nishimura S, Ohta A, Ohmi Y, Sato M, Takeda K, Okumura K, Van Kaer L, Kawano T, Taniguchi M, Nishimura T. The natural killer T (NKT) cell ligand alpha-galactosylceramide demonstrates its immunopotentiating effect by inducing interleukin (IL)-12 production by dendritic cells and IL-12 receptor expression on NKT cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189(7):1121–1128. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.7.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomura M, Yu WG, Ahn HJ, Yamashita M, Yang YF, Ono S, Hamaoka T, Kawano T, Taniguchi M, Koezuka Y, Fujiwara H. A novel function of Valpha14+CD4+NKT cells: stimulation of IL-12 production by antigen-presenting cells in the innate immune system. J Immunol. 1999;163(1):93–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petersen TR, Sika-Paotonu D, Knight DA, Dickgreber N, Farrand KJ, Ronchese F, Hermans IF. Potent anti-tumor responses to immunization with dendritic cells loaded with tumor tissue and an NKT cell ligand. Immunol Cell Biol. 2010;88(5):596–604. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang DH, Osman K, Connolly J, Kukreja A, Krasovsky J, Pack M, Hutchinson A, Geller M, Liu N, Annable R, Shay J, Kirchhoff K, Nishi N, Ando Y, Hayashi K, Hassoun H, Steinman RM, Dhodapkar MV. Sustained expansion of NKT cells and antigen-specific T cells after injection of alpha-galactosyl-ceramide loaded mature dendritic cells in cancer patients. J Exp Med. 2005;201(9):1503–1517. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishikawa A, Motohashi S, Ishikawa E, Fuchida H, Higashino K, Otsuji M, Iizasa T, Nakayama T, Taniguchi M, Fujisawa T. A phase I study of alpha-galactosylceramide (KRN7000)-pulsed dendritic cells in patients with advanced and recurrent non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(5):1910–1917. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicol AJ, Tazbirkova A, Nieda M. Comparison of clinical and immunological effects of intravenous and intradermal administration of alpha-galactosylceramide (KRN7000)-pulsed dendritic cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(15):5140–5151. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nieda M, Okai M, Tazbirkova A, Lin H, Yamaura A, Ide K, Abraham R, Juji T, Macfarlane DJ, Nicol AJ. Therapeutic activation of Valpha24+Vbeta11+NKT cells in human subjects results in highly coordinated secondary activation of acquired and innate immunity. Blood. 2004;103(2):383–389. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jager E, Nagata Y, Gnjatic S, Wada H, Stockert E, Karbach J, Dunbar PR, Lee SY, Jungbluth A, Jager D, Arand M, Ritter G, Cerundolo V, Dupont B, Chen YT, Old LJ, Knuth A. Monitoring CD8 T cell responses to NY-ESO-1: correlation of humoral and cellular immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(9):4760–4765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robbins PF, Morgan RA, Feldman SA, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Nahvi AV, Helman LJ, Mackall CL, Kammula US, Hughes MS, Restifo NP, Raffeld M, Lee CC, Levy CL, Li YF, El-Gamil M, Schwarz SL, Laurencot C, Rosenberg SA. Tumor regression in patients with metastatic synovial cell sarcoma and melanoma using genetically engineered lymphocytes reactive with NY-ESO-1. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(7):917–924. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Melief CJ, van der Burg SH. Immunotherapy of established (pre)malignant disease by synthetic long peptide vaccines. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(5):351–360. doi: 10.1038/nrc2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fujii S, Shimizu K, Kronenberg M, Steinman RM. Prolonged IFN-gamma-producing NKT response induced with alpha-galactosylceramide-loaded DCs. Nat Immunol. 2002;3(9):867–874. doi: 10.1038/ni827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giaccone G, Punt CJ, Ando Y, Ruijter R, Nishi N, Peters M, von Blomberg BM, Scheper RJ, van der Vliet HJ, van den Eertwegh AJ, Roelvink M, Beijnen J, Zwierzina H, Pinedo HM. A phase I study of the natural killer T-cell ligand alpha-galactosylceramide (KRN7000) in patients with solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(12):3702–3709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McEwen-Smith RM, Salio M, Cerundolo V. The regulatory role of invariant NKT cells in tumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3(5):425–435. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snyder-Cappione JE, Tincati C, Eccles-James IG, Cappione AJ, Ndhlovu LC, Koth LL, Nixon DF. A comprehensive ex vivo functional analysis of human NKT cells reveals production of MIP1-alpha and MIP1-beta, a lack of IL-17, and a Th1-bias in males. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(11):e15412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martinuzzi E, Scotto M, Enee E, Brezar V, Ribeil JA, van Endert P, Mallone R. Serum-free culture medium and IL-7 costimulation increase the sensitivity of ELISpot detection. J Immunol Methods. 2008;333(1–2):61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moodie Z, Huang Y, Gu L, Hural J, Self SG. Statistical positivity criteria for the analysis of ELISpot assay data in HIV-1 vaccine trials. J Immunol Methods. 2006;315(1–2):121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.R Core Team (2015) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.r-project.org. Accessed 1 Mar 2016

- 43.Richter J, Neparidze N, Zhang L, Nair S, Monesmith T, Sundaram R, Miesowicz F, Dhodapkar KM, Dhodapkar MV. Clinical regressions and broad immune activation following combination therapy targeting human NKT cells in myeloma. Blood. 2013;121(3):423–430. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-435503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Exley MA, Hou R, Shaulov A, Tonti E, Dellabona P, Casorati G, Akbari O, Akman HO, Greenfield EA, Gumperz JE, Boyson JE, Balk SP, Wilson SB. Selective activation, expansion, and monitoring of human iNKT cells with a monoclonal antibody specific for the TCR alpha-chain CDR3 loop. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38(6):1756–1766. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gibney GT, Kudchadkar RR, DeConti RC, Thebeau MS, Czupryn MP, Tetteh L, Eysmans C, Richards A, Schell MJ, Fisher KJ, Horak CE, Inzunza HD, Yu B, Martinez AJ, Younos I, Weber JS. Safety, correlative markers, and clinical results of adjuvant nivolumab in combination with vaccine in resected high-risk metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(4):712–720. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krishnadas DK, Shusterman S, Bai F, Diller L, Sullivan JE, Cheerva AC, George RE, Lucas KG. A phase I trial combining decitabine/dendritic cell vaccine targeting MAGE-A1, MAGE-A3 and NY-ESO-1 for children with relapsed or therapy-refractory neuroblastoma and sarcoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2015;64(10):1251–1260. doi: 10.1007/s00262-015-1731-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen JL, Dawoodji A, Tarlton A, Gnjatic S, Tajar A, Karydis I, Browning J, Pratap S, Verfaille C, Venhaus RR, Pan L, Altman DG, Cebon JS, Old LL, Nathan P, Ottensmeier C, Middleton M, Cerundolo V. NY-ESO-1 specific antibody and cellular responses in melanoma patients primed with NY-ESO-1 protein in ISCOMATRIX and boosted with recombinant NY-ESO-1 fowlpox virus. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(6):E590–E601. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dhodapkar MV, Steinman RM, Sapp M, Desai H, Fossella C, Krasovsky J, Donahoe SM, Dunbar PR, Cerundolo V, Nixon DF, Bhardwaj N. Rapid generation of broad T-cell immunity in humans after a single injection of mature dendritic cells. J Clin Invest. 1999;104(2):173–180. doi: 10.1172/JCI6909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bijker MS, van den Eeden SJ, Franken KL, Melief CJ, van der Burg SH, Offringa R. Superior induction of anti-tumor CTL immunity by extended peptide vaccines involves prolonged, DC-focused antigen presentation. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38(4):1033–1042. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seder RA, Darrah PA, Roederer M. T-cell quality in memory and protection: implications for vaccine design. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(4):247–258. doi: 10.1038/nri2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yuan J, Gnjatic S, Li H, Powel S, Gallardo HF, Ritter E, Ku GY, Jungbluth AA, Segal NH, Rasalan TS, Manukian G, Xu Y, Roman RA, Terzulli SL, Heywood M, Pogoriler E, Ritter G, Old LJ, Allison JP, Wolchok JD. CTLA-4 blockade enhances polyfunctional NY-ESO-1 specific T cell responses in metastatic melanoma patients with clinical benefit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(51):20410–20415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810114105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berinstein NL, Karkada M, Oza AM, Odunsi K, Villella JA, Nemunaitis JJ, Morse MA, Pejovic T, Bentley J, Buyse M, Nigam R, Weir GM, MacDonald LD, Quinton T, Rajagopalan R, Sharp K, Penwell A, Sammatur L, Burzykowski T, Stanford MM, Mansour M. Survivin-targeted immunotherapy drives robust polyfunctional T cell generation and differentiation in advanced ovarian cancer patients. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4(8):e1026529. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1026529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin Y, Gallardo HF, Ku GY, Li H, Manukian G, Rasalan TS, Xu Y, Terzulli SL, Old LJ, Allison JP, Houghton AN, Wolchok JD, Yuan J. Optimization and validation of a robust human T-cell culture method for monitoring phenotypic and polyfunctional antigen-specific CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses. Cytotherapy. 2009;11(7):912–922. doi: 10.3109/14653240903136987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sabado RL, Pavlick A, Gnjatic S, Cruz CM, Vengco I, Hasan F, Spadaccia M, Darvishian F, Chiriboga L, Holman RM, Escalon J, Muren C, Escano C, Yepes E, Sharpe D, Vasilakos JP, Rolnitzsky L, Goldberg JD, Mandeli J, Adams S, Jungbluth A, Pan L, Venhaus R, Ott PA, Bhardwaj N. Resiquimod as an immunologic adjuvant for NY-ESO-1 protein vaccination in patients with high-risk melanoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3(3):278–287. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.