Abstract

Treatment of metastatic melanoma remains challenging, despite a variety of new and promising immunotherapeutic and targeted approaches to therapy. New treatment options are still needed to improve long-term tumour control. We present a case series of seven patients with metastatic melanoma who were treated individually with the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab between July 2014 and July 2015. Two of the patients were treated in an adjuvant setting. All patients had already received a variety of treatments. During an induction phase, the administration of four cycles of weekly rituximab 375 mg/m2 body surface area was planned. After imaging, patients with stable disease continued therapy with rituximab 375 mg/m2 body surface area every 4 weeks up to a maximum of 24 weeks. Two patients experienced grade 2 infusion reactions during the first infusion. Otherwise, treatment was well tolerated and there were no grade 3 or 4 side effects. Staging after the induction phase showed stable disease in five patients, and two patients had progressive disease. Median progression-free survival was 6.3 months (95% CI 4.97–7.53), median overall survival was 14.7 months (95% CI 4.52–24.94), and one patient was still alive in December 2016. In conclusion, rituximab might be a therapeutic option for metastatic melanoma. However, further studies on rituximab among larger patient cohorts are warranted. Evaluation of therapy in an adjuvant setting or in combination with other systemic treatment might, therefore, be of particular interest.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00262-018-2145-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Melanoma, Immunotherapy, Anti-CD 20 antibody, Rituximab

Introduction

The incidence of melanoma has increased in recent decades [1], and treatment of metastatic disease remains challenging. Immunotherapy and targeted therapy are promising treatments [2], but long-term disease control is still not achieved for most patients. The need for new therapeutic approaches or combination therapy therefore remains.

Immunotargeting of specific tumour subpopulations has become of special interest [3]. CD20 has been identified as one of the genes that affect the aggressiveness of malignant melanoma [4]. A subpopulation of melanoma cells with stem cell properties expressing CD20 has been described [5]. The antigen CD20 is also a B cell surface marker. It has been observed that B cells are of major importance in humoral response in melanoma [6]. Improved clinical outcome along with greater numbers of tumour-associated B cells in primary melanomas has been reported [7, 8]. B cells in melanoma may promote pro- and anti-tumour functions [6, 9]. B cells secreting immunosuppressive IL-10 have been widely discussed as potentially regulatory B cells [10–12]. Moreover, tumour-infiltrating B cells may contribute to resistance to therapy, for example, to B-Raf proto-oncogene (BRAF) and mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitors, by producing insulin-like growth factor 1 [13].

In mice, complete and ongoing eradication of melanoma was achieved by targeting the small subgroup of CD20+ melanoma cells [14]. In a pre-clinical xenograft model, the growth of human melanoma cells was completely inhibited by administration of autologous T cells, which express an anti-CD20 chimeric antigen CD3z receptor that specifically targets CD20+ cells [3, 15].

In humans, intravenous rituximab combined with subcutaneous Il-2 did not increase response in the treatment of metastatic melanoma, but the number of circulating B cells was reduced [16]. In a chemotherapy-refractory patient, however, successful therapy with intralesional injections of rituximab combined with concomitant dacarbazine has been reported [17]. Moreover, adjuvant therapy with rituximab has been evaluated in a small cohort of stage IV melanoma patients, and good clinical outcomes in this patient group have been observed [18]. In a recent pilot study, clinical activity of the CD20 antibody ofatumumab was demonstrated in the treatment-resistant advanced melanoma [13].

At our centre, patients with advanced metastatic melanoma were offered individual treatment with rituximab.

Materials and methods

Before the start of treatment, all patients received detailed information about the benefits and risks of their individual therapy with rituximab. They were informed about possible side effects, such as allergic infusion reactions and an increased risk of infections. Therapy took place in the outpatient clinic of the National Center for Tumor Diseases at the University Hospital of Heidelberg between July 2014 and July 2015. Treatment was divided into two parts: an initial induction phase, which included four cycles of weekly rituximab 375 mg/m2, and a subsequent maintenance phase, when rituximab 375 mg/m2 was given every 4 weeks for a maximum of 24 weeks. Side effects were documented according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. Tumours were assessed before initiation of therapy, after the induction phase (four cycles of weekly rituximab followed by imaging approximately 4 weeks later) and regularly during the maintenance period. Imaging included brain MRI and computed tomography scans of the neck, thorax and abdomen. Routine laboratory measurements including blood count and C-reactive protein values were taken before each therapy cycle and S100 was determined intermittently. Peripheral blood FACS analyses were performed to examine the number of circulating B cells (CD19). Tissue samples for immunohistochemical assessment were acquired before and during therapy with rituximab.

Clinical data were obtained from patients’ clinical records. Analyses were conducted using suitable statistical methods, for example, frequency tables. IBM SPSS Statistics 22 was used. Median PFS and OS and the accompanying 95% confidence interval were estimated by use of the Kaplan–Meier method.

Results

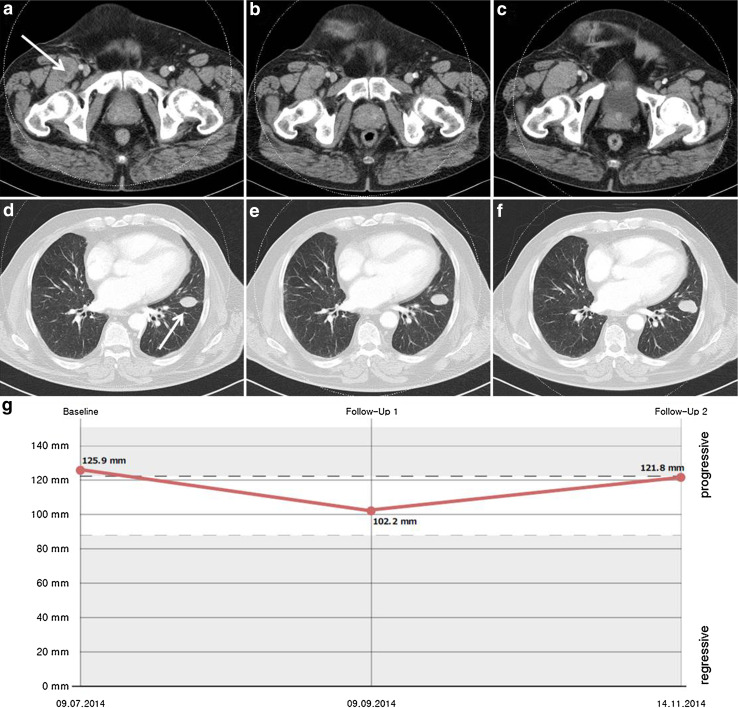

All seven patients (median age 63 years, range 36–69; five males, two females) had stage IV M1c disease based on the 2009 American Joint Committee on Cancer classification. Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. Five patients had measurable disease when therapy was initiated, and two patients were treated in an adjuvant setting. Before therapy with rituximab, all patients had received several previous treatments. All had received ipilimumab. In addition, five patients had previously been treated with an anti-PD1 antibody, and one of the three patients with a BRAF V600 mutated tumour had already received pretreatment with a BRAF inhibitor. All patients completed the induction phase. Six patients received four cycles of weekly rituximab during the induction phase, and the first patient received eight cycles. First staging 8 weeks after the start of treatment revealed stable disease in five patients and progressive disease in two as best response to treatment. The most favourable course of the disease during the induction phase, an 18.8% decrease in tumour burden, was observed for the patient who received eight cycles of rituximab during the induction phase (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics, information on further therapy, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS)

| Patient no. | Age | Gender | Mutation | Pretreatment | Stage AJCC 2009 | Site of metastases | Adjuvant setting | Rituximab doses during induction phase | Rituximab doses during maintenance phase | Best response | PFS (months) | Site of progression | Treatment following progression | OS (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 69 | M | BRAF, NRAS, c-kit wt | Polychemotherapy, ipilimumab, nivolumab (NCT01721746), radiotherapy (brain) | IV—M1c | Cerebral, pulmonary, lymph node, hepatic | No | 8 | 4 | SD | 8.0 | Cerebral, pulmonary, subcutaneous, spleen, inguinal lymph node | Pembrolizumab, ipilimumab/nivolumab | 18.9 |

| 2 | 36 | M | BRAF V600E | Ipilimumab, radiotherapy (brain), surgery | IV—M1c | Subcutaneous, cerebral, osseous | Yes | 4 | 6 | SD | 10.9 | Cerebral | Surgery (brain), radiotherapy (brain), pembrolizumab, BRAFi/MEKi, polychemotherapy | 18.4 |

| 3 | 49 | M | BRAF V600R | Interferon, surgery, ipilimumab (NCT01216696), nivolumab (NCT01721746), radiotherapy (brain) | IV—M1c | Cerebral, pulmonary, spleen, hepatic, lymph node, adrenal, osseous | No | 4 | 3 | SD | 5.8 | Soft tissue (gluteal) | Surgery (brain), radiotherapy (gluteal), BRAFi/MEKi, radiotherapy (osseous, brain) | 10.8 |

| 4 | 64 | F | BRAF V600E | Vemurafenib, ipilimumab, surgery | IV—M1c | Lymph node | Yes | 4 | 4 | SD | 12.4 | Cerebral | Radiotherapy (brain), pembrolizumab, ipilimumab/ pembrolizumab | > 23.0 |

| 5 | 63 | M | BRAF, c-kit wt | Interferon, surgery, monochemotherapy, ipilimumab, pembrolizumab, radiotherapy (brain) | IV—M1c | Cerebral, lymph node | No | 4 | 0 | PD | 1.0 | Cerebral, lymph node | Resection (brain), polychemotherapy, ipilimumab/nivolumab, radiotherapy (amongst others brain) | 7.0 |

| 6 | 63 | M | BRAF, NRAS, c-kit wt | Surgery, ipilimumab, radiotherapy, pembrolizumab, radiotherapy (brain) | IV—M1c | Pulmonary, mediastinal, pancreatic, osseous, cerebral | No | 4 | 0 | PD | 1.3 | Cerebral, spinal, pulmonary, mediastinal | Radiation to the spine | 3.1 |

| 7 | 59 | F | BRAF, NRAS, c-kit wt | Interferon i.v., ipilimumab/nivolumab (NCT01844505), IL-2 s.c., radiotherapy (brain) | IV—M1c | Cerebral, hepatic, lymph node, pulmonary | No | 4 | 4 | SD | 6.2 | Cerebral | Surgery (brain), radiotherapy (brain), polychemotherapy, radiotherapy (spinal) | 14.7 |

M male, F female, wt wild type, SD stable disease, PD progressive disease, BRAF serine/threonine protein kinase B-raf, NRAS neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homologue, C-kit cellular homologue of the feline sarcoma viral oncogene v-kit

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography scans of thorax and abdomen showing an exemplary target lesion in the left lung and a right inguinal lesion before therapy with rituximab (a, d), after the induction phase (b, e), and after three more cycles of maintenance therapy (c, f). The corresponding diagram shows the sum of target lesions (g)

Patients whose disease was stable after the induction phase continued the therapy. One patient received three additional cycles of rituximab, two patients received four more cycles and one patient received six additional cycles of rituximab until disease progression. One patient also underwent two surgical resections of subcutaneous metastases followed by adjuvant radiotherapy during the maintenance period. Median PFS was 6.3 months (95% CI 4.97–7.53). The patients who were treated in an adjuvant setting achieved the longest PFS (10.9 and 12.4 months). At the time of disease progression, progressive brain metastases were found in six patients. Consecutive therapies included resection of cerebral metastases, adjuvant whole brain radiation, stereotactic brain radiotherapy and radiotherapy for spinal metastases. Three patients received an anti-PD-1 antibody as a consecutive treatment, two patients received polychemotherapy and one patient was started on a BRAF inhibitor. One patient experienced progression of a gluteal metastasis and underwent radiotherapy. One patient’s disease progressed rapidly and further therapy was not feasible. Six patients have since died, and one patient was still receiving immunotherapy with an anti-PD-1 antibody in December 2016. Median OS (including subsequent therapy) was 14.7 months (95% CI 4.52–24.94).

Treatment-related side effects were mild. During the first infusion, two patients had grade 2 infusion-related reactions. One of these received antihistamine medication intravenously. There were no grade 3 or 4 side effects during therapy.

Laboratory values including leucocyte and lymphocyte counts as well as CRP values were documented (Supplementary Table 1). Increasing LDH and S100 values were measured along with disease progression (patient no. 3) (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). FACS analyses performed during the maintenance period revealed complete or almost complete B cell depletion even several weeks after the preceding infusion (Table 2). Tissue analysis showed numerous CD20+ cells within tissue from a lung metastasis before the start of therapy with rituximab (Fig. 2a). Depletion of CD20+ cells was evident after the induction phase (Fig. 2b). The CD20+ cells were localised at the tumour margin and co-localised with PAX5 (Fig. 2c, d, Supplementary Fig. 1). On the basis of localization and morphology, it is likely the cells are B cells and not CD20+ tumour cells.

Table 2.

FACS analyses performed during therapy with rituximab

| Patient no. | Number of previous cycles | Days from last cycle | Lymphocyte count (%) | T cells (%) | CD4+/CD8+ | B cells (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11 | 20 | 20 | 89 | 0.96 | 0 |

| 1 | 12 | 97 | 16 | 89 | 0.89 | 0.15 |

| 2 | 8 | 30 | 17 | – | – | 0 |

| 2 | 10 | 27 | 19 | – | – | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | – | 8 | 63 | 1.2 | 4 |

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical analysis of CD20 (a, b), PAX5 (c, d), CD3 (e, f), CD4 (g, h), and CD8 (i, j) expression on formalin-fixed tissue in a lung metastasis before therapy (a, c, e, g, i), and in a subcutaneous metastasis after the induction phase (b, d, f, h, j), (patient no. 2). Asterisks mark metastases. White arrows mark CD20+ cells. Black arrows mark T lymphocytes. Original magnification ×100, all panels

Discussion

We present a case series of seven patients who received individual treatment with rituximab for metastatic melanoma. Although it is difficult to calculate therapeutic value from such a small cohort of patients, we observed some good clinical results with rituximab in advanced and pre-treated patients with metastasised melanoma. All patients had stage IV M1c melanoma with limited tumour burden and LDH values within normal range. Two patients received treatment in an adjuvant setting with no detectable metastases in the preceding staging. Among patients with measurable metastases, one patient’s tumour burden decreased significantly after the induction phase; for two others, fast disease progression with several new tumour lesions was observed during treatment with rituximab. Patients who received adjuvant treatment achieved the longest PFS. One of these is still receiving immunotherapy with an anti-PD-1 antibody. In a previous case series, Pinc et al. reported on nine patients who received adjuvant treatment with weekly rituximab for 4 weeks, followed by maintenance therapy every 8 weeks for up to 2 years [18]. After 42 months, relapse-free and overall survival was not achieved. Six patients were still alive and five were recurrence-free. Adjuvant therapy may, therefore, be a reasonable approach, because criteria for selection of suitable patients are still unclear. It has, for example, previously been reported that not all patients harbour CD20+ melanoma cells [15]. However, it is not clear if the CD20+ stem cell-like melanoma cells or tumour-infiltrating B cells are the target of the CD20 antibody responsible for its clinical effect. We have observed post-treatment depletion of CD20+ cells in melanoma. These cells were mainly found at the tumour margin, co-localised with cells expressing the B cell marker PAX-5, and on the basis of histological morphology, were not tumour cells. Whether these were immunosuppressive B cells is unproved [6]. Further investigations of the different B cell subsets and tumour cells in sequential biopsies of patients are required to answer this question.

Because of its beneficial safety profile and its potential to overcome tumour resistance mechanisms, targeting CD20+ cells might be a good option for combination treatment [13]. There are studies on the combination of rituxan and abraxane and on CD20 antibody-conjugated immunoliposomes [NCT02142325, 19]. We have reported on a patient whose tumour lesions decreased significantly during rituximab therapy after receiving an anti-PD-1 antibody. It remains to be evaluated whether immune checkpoint inhibitors may, under specific conditions, promote response to rituximab. In treatment of lymphoma, combination of the PD-1-antibody pidilizumab with rituximab has been very well tolerated [20]. A similar approach in metastatic melanoma might increase response to an anti-PD-1 antibody with a better toxicity profile than in combination with ipilimumab.

In summary, we suggest that treatment with rituximab might be a therapeutic option for patients with advanced metastatic melanoma. The beneficial toxicity profile suggests that combining rituximab with other systemic treatments, e.g. PD-1 antibodies, might increase therapeutic efficacy and should be further investigated in clinical trials. Despite heterogeneity, our study may be helpful when initiating a thoroughly designed phase I trial.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Hazel Davis for English revision.

Abbreviations

- BRAF

B-Raf proto-oncogene

- PFS

Progression-free survival

Author contributions

JKW analyzed clinical data and prepared the manuscript. MS and CB contributed to data acquisition and revised the manuscript. AHE was involved in manuscript proof-reading and finalization. JCH designed and coordinated the project, performed the immunohistochemical analyses and revised the manuscript. All authors had full access to all reported data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors take responsibility for the preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

No relevant funding.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The institutional review board of the Medical Faculty of the University Hospital of Heidelberg (S-454/2015) approved the retrospective institutional patient data analysis. Guidelines from the Declaration of Helsinki were followed.

Informed consent

All patients gave written informed consent to individual treatment with rituximab. They were informed that therapy with rituximab is experimental and has not been approved for melanoma treatment.

Footnotes

Julia K. Winkler and Matthias Schiller contributed equally.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grossmann KF, Margolin K. Long-term survival as a treatment benchmark in melanoma: latest results and clinical implications. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2015;7:181–191. doi: 10.1177/1758834015572284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maurer M, Somasundaram R, Herlyn M, Wagner SN. Immunotargeting of tumor subpopulations in melanoma patients: A paradigm shift in therapy approaches. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:1454–1456. doi: 10.4161/onci.21357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bittner M, Meltzer P, Chen Y, et al. Molecular classification of cutaneous malignant melanoma by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;406:536–540. doi: 10.1038/35020115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang D, Nguyen TK, Leishear K, et al. A tumorigenic subpopulation with stem cell properties in melanomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9328–9337. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiaruttini G, Mele S, Opzoomer J, Crescioli S, Ilieva KM, Lacy KE, Karagiannis SN. B cells and the humoral response in melanoma: The overlooked players of the tumor microenvironment. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1294296. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1294296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ladanyi A, Kiss J, Mohos A, et al. Prognostic impact of B-cell density in cutaneous melanoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60:1729–1738. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1071-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garg K, Maurer M, Griss J, Bruggen MC, Wolf IH, Wagner C, Willi N, Mertz KD, Wagner SN. Tumor-associated B cells in cutaneous primary melanoma and improved clinical outcome. Hum Pathol. 2016;54:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2016.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saul L, Ilieva KM, Bax HJ, et al. IgG subclass switching and clonal expansion in cutaneous melanoma and normal skin. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29736. doi: 10.1038/srep29736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perricone MA, Smith KA, Claussen KA, Plog MS, Hempel DM, Roberts BL, St George JA, Kaplan JM. Enhanced efficacy of melanoma vaccines in the absence of B lymphocytes. J Immunother. 2004;27:273–281. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200407000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz M, Zhang Y, Rosenblatt JD. B cell regulation of the anti-tumor response and role in carcinogenesis. Immunother Cancer. 2016;4:40. doi: 10.1186/s40425-016-0145-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egbuniwe IU, Mohamad MH, Karagiannis SN, Nestle FO, Lacy KE. Interleukin-10-producing B-cell subpopulations in melanoma. British society for investigative dermatology meeting, Exeter. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:e15–e40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10903.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Somasundaram R, Zhang G, Fukunaga-Kalabis M, et al. Tumor-associated B-cells induce tumor heterogeneity and therapy resistance. Nat Commun. 2017;8:607. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00452-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt P, Abken H. The beating heart of melanomas: a minor subset of cancer cells sustains tumor growth. Oncotarget. 2011;2:313–320. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt P, Kopecky C, Hombach A, Zigrino P, Mauch C, Abken H. Eradication of melanomas by targeted elimination of a minor subset of tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2474–2479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009069108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aklilu M, Stadler WM, Markiewicz M, Vogelzang NJ, Mahowald M, Johnson M, Gajewski TF. Depletion of normal B cells with rituximab as an adjunct to IL-2 therapy for renal cell carcinoma and melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1109–1114. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schlaak M, Schmidt P, Bangard C, Kurschat P, Mauch C, Abken H. Regression of metastatic melanoma in a patient by antibody targeting of cancer stem cells. Oncotarget. 2012;3:22–30. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinc A, Somasundaram R, Wagner C, et al. Targeting CD20 in melanoma patients at high risk of disease recurrence. Mol Ther. 2012;20:1056–1062. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song H, Su X, Yang K, et al. CD20 antibody-conjugated immunoliposomes for targeted chemotherapy of melanoma cancer initiating cells. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2015;11:1927–1946. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2015.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Westin JR, Chu F, Zhang M, et al. Safety and activity of PD1 blockade by pidilizumab in combination with rituximab in patients with relapsed follicular lymphoma: a single group, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:69–77. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70551-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.