Abstract

Human tumor cells express antigens that serve as targets for the host cellular immune system. This phase 1 dose-escalating study was conducted to assess safety and tolerability of G305, a recombinant NY-ESO-1 protein vaccine mixed with glucopyranosyl lipid A (GLA), a synthetic TLR4 agonist adjuvant, in a stable emulsion (SE). Twelve patients with solid tumors expressing NY-ESO-1 were treated using a 3 + 3 design. The NY-ESO-1 dose was fixed at 250 µg, while GLA-SE was increased from 2 to 10 µg. Safety, immunogenicity, and clinical responses were assessed prior to, during, and at the end of therapy. G305 was safe and immunogenic at all doses. All related AEs were Grade 1 or 2, with injection site soreness as the most commonly reported event (100%). Overall, 75% of patients developed antibody response to NY-ESO-1, including six patients with increased antibody titer ( ≥ 4-fold rise) and three patients with seroconversion from negative (titer < 100) to positive (titer ≥ 100). CD4 T-cell responses were observed in 44.4% of patients; 33.3% were new responses and 1 was boosted ( ≥ 2-fold rise). Following treatment, 8 of 12 patients had stable disease for 3 months or more; at the end of 1 year, three patients had stable disease and nine patients were alive. G305 is a potent immunotherapeutic agent that can stimulate NY-ESO-1-specific antibody and T-cell responses. The vaccine was safe at all doses of GLA-SE (2–10 µg) and showed potential clinical benefit in this population of patients.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00262-019-02331-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: NY-ESO-1, Solid tumors, Vaccine, Glucopyranosyl lipid A, Clinical trial

Introduction

Harnessing the cellular immune system to kill tumor cells holds promise for treating a variety of human malignancies [2, 3]. Tumor cells express tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) that differentiate them from normal cells. These TAAs provide accessible targets that the host’s immune system can use to destroy tumors. New York Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma 1 (NY-ESO-1), which is expressed in melanoma, certain sarcomas, and in ovarian, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and other types of carcinoma, is one such TAA [4–6]. As a cancer-testis antigen, it is an ideal target for cancer immunotherapy because the only anatomical sites where NY-ESO-1 is expressed under physiological condition are testes and placenta, which are immunologically privileged [7], and, in addition, spermatogonia are devoid of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-class I molecules and are thus not able to present antigens to T cells. In patients with various NY-ESO-1-positive solid tumors, the presence of spontaneous or induced anti-NY-ESO-1 antibodies in association with NY-ESO-1-specific CD8 or CD4 T-cell responses has been shown to correlate with clinical benefit in subsets of patients after immunotherapy [8–14]. Although NY-ESO-1 recombinant protein alone can induce a CD4 T-cell response in many patients following vaccination, administration of the protein together with an adjuvant, such as imiquimod or Bacillus Calmette–Guerin (BCG) and granulocyte–macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), resulted in the generation of stronger NY-ESO-1-specific antibody and CD4 T-cell responses and can also induce CD8 T cells, when compared with unadjuvanted NY-ESO-1 protein [8, 14].

Glucopyranosyl lipid A (GLA) is a synthetic, detoxified derivative of the lipid A moiety of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which is the prototypic activator of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) [15]. In TLR4-expressing antigen presenting cells, such as macrophages and dendritic cells, GLA in stable oil-in-water emulsion (GLA-SE) induces Th1-type proinflammatory cytokines via myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88)/NF-kB signaling, type-1 interferons via the TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF) pathway, and activation markers CD40, CD83, CD86, CCR7, and HLA-DR [15–17]. In addition, it was recently shown that GLA-SE also activates the NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, which results in the secretion of the potent innate immune activators IL-18 and IL-1β [18, 19]. The authors speculated that engagement of both TLR and inflammasome pathways to promote strong and durable adaptive immune responses is a universal feature of effective adjuvants. GLA, particularly in a stable oil-in-water emulsion (GLA-SE), can potently activate the innate and adaptive immune system in several preclinical models as a vaccine adjuvant [20–24]. Importantly, the stimulatory effect of GLA-SE on both Th1-type antibody and CD4 T-cell responses resulted in increased titers and breadth of protection, which has been shown both preclinically and clinically in Phase 1 and 2 trials with different vaccine antigens [25–27]. In addition, we have shown preclinically that GLA-SE can also prime cytotoxic CD8 T cells that can be recalled and are protective in a viral challenge model [28]. Over 2000 patients have been injected with vaccines containing GLA-SE as an adjuvant in doses ranging from 0.5 to 20 μg, with an excellent safety record [25–27].

G305, Immune Design’s novel immunotherapy agent, is composed of bacterially expressed full-length NY-ESO-1 protein adjuvanted with GLA-SE. NY-ESO-1 has been previously studied in over 20 vaccine trials using different adjuvants, including cytosine phosphate–guanine (CpG) [29], montanide, iscomatrix [30, 31], polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid–poly-l-lysine–carboxymethylcellulose (poly-ICLC) [32], BCG which activates both TLR2 and TLR4 [14], and OK-432 which is a streptococcal preparation that activates TLR4 [33]. However, the combination of NY-ESO-1 with GLA, a novel TLR4 agonist as an adjuvant has not been reported in the human setting.

This first-in-human phase 1 study evaluated the clinical safety and immunogenicity of repeat injections of G305 in patients with advanced NY-ESO-1-expressing malignancies. The cancer types chosen for study (melanoma, ovarian cancer, synovial sarcoma, NSCLC, and breast cancer) included not only those known to express NY-ESO-1 at a reasonably high frequency, but also those with a history of responsiveness to NY-ESO-1 immune-based approaches [9, 34].

Patients and methods

Study design

It was planned to enroll up to 18 evaluable patients with unresectable, relapsed, or metastatic cancer expressing the NY-ESO-1 cancer antigen in this phase 1, open-label, multicenter, dose-escalating trial at three centers in the United States. The sample size was chosen to provide preliminary data for subsequent clinical studies rather than to assure a given level of statistical power. Doses of NY-ESO-1 and GLA-SE were determined based on results of prior published vaccine studies. Patients were assigned to treatment in a 3 + 3 sequential dose-escalation design. G305, comprising GLA-SE doses of 2, 5, or 10 µg and a fixed dose of 250 µg NY-ESO-1, was administered intramuscularly (IM) on Days 0, 21, and 42. It was planned to enroll a minimum of 12 patients, with a minimum of 6 patients in the final cohort. One subject in each cohort received the first G305 injection, then at least 24 h later, the next two patients in each cohort could be dosed. Dose escalation was contingent upon assessment of safety data. A dosing cohort was to be expanded to six patients if any 1 of the first 3 enrolled patients in a given cohort experienced a dose-limiting toxicity (DLT). If two or more patients in a dose-level cohort developed an AE that was considered a DLT, then the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) would have been exceeded and further administration at that dose level was discontinued. The dose was increased to the next level when less than one-third of patients in a cohort experienced a DLT and the Safety Monitoring Committee (SMC) concurred with escalation.

Patients were monitored for AEs and serious adverse events (SAEs) every 7 days, either during a clinic visit or by telephone follow-up. Disease status was assessed on day 70 with computed tomography (CT) imaging or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Patients with ovarian cancer were also assessed using CA-125 measurements at baseline and on days 0, 21, 42, and 70. Follow-up was continued every 12 weeks for 1 year after enrollment to assess survival, AEs, disease status, and current cancer treatments.

Selection of study population

Inclusion criteria included having a projected life span of 6 months or more and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status of 0 or 1. All patients had a confirmed histologic or cytologic diagnosis of melanoma, ovarian cancer, synovial sarcoma, bladder cancer, breast cancer, or NSCLC with demonstration of NY-ESO-1 positivity in at least 1% of the cells using a qualified immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay (Mosaic Laboratories, Lake Forest, CA, USA) in a previous biopsy. The cancers had to be unresectable, relapsed, and/or metastatic with minimal- or low-disease burden and not rapidly progressive. Patients could be enrolled if they had histories of inadequate response, relapse, and/or unacceptable toxicity with one or more prior systemic, surgical, or radiation cancer therapies. Women of child-bearing age were tested for pregnancy before enrollment and before administration of each vaccine; G305 was not administered until a negative pregnancy test was confirmed. Both female patients of child-bearing age and male patients with female sexual partners of child-bearing age had to agree to use a highly effective form of contraception during the study and for at least 3 months after the study. In patients with melanoma, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels had to be less than or equal to the upper limit of normal (ULN) of the local laboratory.

Exclusion criteria included age under 18 years, currently pregnant, previous NY-ESO-1 therapy, cancer chemotherapy within 3 weeks prior to start of G305 dosing, or immunosuppressive treatments within 4 weeks of starting. Patients with severe psychiatric disorders were excluded, as were patients with severe autoimmune disease or heart disease, abnormal hematologic parameters, clinically significant infections, or evidence of metabolic dysfunction, including significant kidney disease or liver disease. Other exclusionary criteria included a history of another cancer within 3 years (except early-stage non-melanoma skin cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia). Patients with uveal melanoma or unstable brain metastases were not included in the study.

Vaccine administration

The investigational drug products included recombinant NY-ESO-1 antigen, a full-length, purified, 180-amino acid-native protein with a 12-amino acid 5′ His6-tag region, whose cDNA was cloned in Escherichia coli (Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, New York, NY, USA), and GLA-SE, a stable oil-in-water squalene-based emulsion formulation containing GLA made by high-pressure microfluidization (provided by the manufacturing group of Immune Design, Seattle, WA, USA). The components were mixed and then administered as a 1-mL IM injection in the deltoid region on days 0, 21, and 42 using alternating arms for each dose. Each injection consisted of 250 µg NY-ESO-1 antigen mixed with 2 µg, 5 µg, or 10 µg GLA in 2% SE, depending on the cohort.

Safety measures and adverse events

All patients were evaluated at screening, baseline, and at regular intervals throughout the study. Safety assessments included symptoms, physical examination findings, vital signs, AEs, electrocardiograms (ECGs) (as applicable), and clinical laboratory evaluations (hematology, blood chemistry, and urinalysis). AEs were classified using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) Version 16.0 and their severities classified using the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.03.

The DLT assessment period was 28 days from vaccine administration and was defined as an AE considered Grade 3 or higher that was possibly, probably, or definitely related to G305. Exceptions were made for diarrhea ≥ Grade 3, provided the symptoms responded to treatment; elevated bilirubin levels in patients with Gilbert’s disease, provided bilirubin elevation was ≤ 3 × the baseline value and lasted less than 5 days; fatigue Grade < 4; and systemic reactions, including fever, malaise, headache, and nausea, that returned to baseline or Grade 1 within 3 days of vaccination. Before enrollment of both the second and third cohorts, the SMC reviewed data from the previous cohort to assess the occurrence of DLTs.

Immunogenicity measurements

Blood was collected on days 7, 0, 21, 28, 42, and 70 for the isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and plasma to measure cellular and humoral immune response to the vaccine. Cellular immunogenicity was measured by enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) in all patients and by intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) in a subset of patients. T-cell subset-specific cultured ELISPOT provided the primary immunogenicity assessment. While it is less sensitive, ICS complemented these measurements in selected patients to show the production and accumulation of cytokines in PBMCs and to assess in vitro NY-ESO-1-specific peripheral blood T-cell cytokine release. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) measurement of antibody response to NY-ESO-1 was performed in all patients.

CD4 and CD8 T-cell ELISPOT

ELISPOT was used to detect levels of NY-ESO-1-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells after in vitro stimulation of T cells [13, 30]. Briefly, CD4 and CD8 cells were sequentially positively selected from PBMC using magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). The remaining T-cell-depleted cells containing autologous target cells were pulsed overnight with a pool of overlapping 20mer peptides (1 µM, Multiple Peptide Systems, San Diego, CA, USA) that covered the entire NY-ESO-1 sequence or a control irrelevant target, influenza nucleoprotein (NP). The peptide pulsed cells were irradiated, mixed with isolated CD4 or CD8 T cells and placed in culture (50,000 T cells/well) with interleukin 2 (IL-2) (Roche) and interleukin-7 (IL-7) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) until testing by IFN-γ ELISPOT. In vitro culture of CD8 T cells was performed for 10 days prior to ELISPOT; culture of CD4 T cells was performed for three weeks prior to ELISPOT. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and influenza nucleoprotein (NP) peptide pools were used as negative and positive controls, respectively, along with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)/ionomycin. Responses were counted as positive if at least 50 spots/50,000 seeded cells were present and were greater than 2 × above the irrelevant control. Responses were considered increased if they were more than twofold over baseline.

Intracellular cytokine staining

PBMC were seeded in 96-well plates at 1.5 million cells per well and treated with medium alone, NY-ESO-1 overlapping 15mer peptides (2.5 µg/mL, from JPT Peptide Technologies, Berlin, Germany), or the positive control, Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin type B (SEB). After 1 h of stimulation, a Golgi plug was added to prevent cytokine secretion. The cells were cultured for another 16 h before they were stained for intracellular cytokines [IFN-γ, IL-2, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα)] and surface markers. The panel of antibodies included CD3-BV786 (clone SP34-2, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), CD4-PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone RPA-T4, BD Biosciences), CD8a-BV650 (clone RPA-T8, BD Biosciences), CD27-BV605 (clone O323, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), CD45RA-APC-Cy7 (clone HI100, BioLegend), IL2-Alexa 700 (clone MQ1-17-H12, BioLegend), TNF-α-APC (clone 6401.1111, BD Biosciences), IFNγ-FITC (clone B27, BD Biosciences), CD154-BV421 (clone TRAP1, BioLegend), CD107a-PE (clone H4A3, BD Biosciences), CD56-BV711 (clone HCD56, BioLegend), Granzyme B-PE-CF594 (clone GB11, BD Biosciences). A live/dead dye (V500, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) was also included. The stained samples were analyzed on a 14-color flow cytometer and the list mode files were analyzed in FlowJo (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA).

ELISA

Humoral immunogenicity was measured as reciprocal titers of serum anti-NY-ESO-1 immunoglobulin G (IgG) in ELISA testing. Briefly, sera from each time point were tested in 2–6 replicates in each patient using serial 4 × dilutions from 1/100 to 1/100,000 for reactivity to full-length NY-ESO-1 recombinant protein (1 µg/mL, different source from vaccine protein), NY-ESO-1 overlapping peptide pools (1 µmol/L), and negative control antigens (p53 and SSX2) as described [14]. Titers were extrapolated based on a cutoff established from a pool of healthy donor sera, and assays were validated using positive control sera for each antigen present on each plate. Results were considered significant if titers were ≥ 100, and changes were considered significant if increased from baseline by at least a fourfold or a new-positive geometric mean titer (GMT) ≥ 1:100.

Efficacy assessment

Tumor staging was performed at baseline and at the day 70 visit by physical examination and imaging (CT or MRI). Investigators also assessed patients as indicated, as part of ongoing care. Tumor response was assessed according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) v1.1. Peripheral blood CA-125 levels were serially measured in patients with ovarian cancer on days 0, 21, 42, and 70.

Statistical methods

The design of this study did not include hypothesis testing. In general, categorical variables were summarized as the number and percentage of patients in each category. Continuous variables were summarized using the mean, range, and standard deviation (SD). Safety analyses were performed using data from all patients receiving at least 1 dose of G305. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were summarized within each dose-level cohort. Abnormal hematology and clinical chemistry values obtained during the study were assigned CTCAE grades, and shifts in the CTCAE grade from baseline grade to the post-baseline grade were summarized as counts and percentages.

Results

Patient disposition, demographics, and baseline characteristics of the safety population

Thirteen patients who had melanoma, ovarian cancer, synovial sarcoma, or urothelial carcinoma were enrolled in the study starting in February 2014. One patient with ovarian cancer withdrew from the study without receiving treatment at her physician’s discretion and was excluded from subsequent analysis. The majority of patients were female (75%) and white (100%) with a mean age (SD) of 60.8 (17.1) years (range 19–78 years); tumor types and disease status were approximately evenly distributed among the dose-escalation cohorts with a total of seven (58.3%) patients with ovarian cancer, three (25.0%) patients with synovial sarcoma, one (8.3%) patient with melanoma, and one (8.3%) patient with advanced urothelial carcinoma (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics in the safety population

| Cohort 1:2 µg GLA-SE(N = 3) | Cohort 2:5 µg GLA-SE(N = 3) | Cohort 3:10 µg GLA-SE(N = 6) | Total(N =12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolleda, n (%) | 3 (100) | 3 (100) | 6 (100) | 13 (100) |

| Safety populationb, n (%) | 3 (100) | 3 (100) | 6 (100) | 12 (92.3) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 61.7 (13.0) | 50.0 (27.4) | 65.8 (13.2) | 60.8 (17.1) |

| Median | 61.0 | 60.0 | 67.5 | 62.0 |

| Range | 49–75 | 19–71 | 43–78 | 19–78 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 3 (100) | 2 (66.7) | 4 (66.7) | 9 (75.0) |

| Male | 0 (0.0) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (25.0) |

| Tumor type, n (%) | ||||

| Melanoma | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (8.3) |

| Ovarian | 2 (66.7) | 2 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) | 7 (58.3) |

| Synovial sarcoma | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (25.0) |

| Urothelial carcinoma | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (8.3) |

| Stage, n (%) | ||||

| Stage III | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (33.3) |

| Stage IV | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 5 (83.3) | 8 (66.7) |

| NY-ESO-1 (% positive cells) | ||||

| Mean | 71.0 | 73.0 | 48.7 | 60.3 |

| Completed day 70, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 3 (100.0%) | 3 (100.0%) | 6 (100.0%) | 12 (100.0%) |

aOne patient was enrolled, but was not treated and discontinued due to physician decision

bSafety population included those all enrolled patients who receive at least 1 dose study drug. All patients in the safety population received the three planned doses of the study drug

At screening, no subject had an ECOG performance status higher than 1. The average amount of NY-ESO-1 expression in tumors was lowest in Cohort 3. All patients had undergone prior cancer-related surgeries and all but 1 patient, who had urothelial carcinoma, had also received radiation, immunotherapy, or chemotherapy.

Safety

All patients (100%) reported at least one TEAE. No deaths occurred during the treatment period, no patient was withdrawn from the study because of a TEAE, no DLTs occurred, and no TEAE was considered an AE of special interest (AESI). No patient stopped treatment with the study drug or had a modified dose of the study drug administered because of a TEAE. SAEs were reported in two patients (16.7%), both patients were in Cohort 3 (10 µg GLA-SE) and both events required hospitalization. One subject experienced abdominal pain (Grade 3, unrelated to study drug) and the other patient had a pleural effusion (Grade 2, unrelated to study drug). The most common TEAE was injection site pain, which was reported by 12 (100%) patients. Other TEAEs reported in more than 10% of patients overall included fatigue and nausea [each reported by 4 (33.3%) patients], vomiting [3 (25.0%) patients], and pain, diarrhea, and hyperkalemia [each reported by 2 (16.7%) patients] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Treatment-emergent adverse events in > 10% of patients

| System organ class Preferred term |

Cohort 1 N = 3 |

Cohort 2 N = 3 |

Cohort 3 N = 6 |

All patients N = 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| General disorders and administration | ||||

| Injection site pain | 3 (100) | 3 (100) | 6 (100) | 12 (100) |

| Fatigue | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (33.3) |

| Pain | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 2 (16.7) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | ||||

|

Nausea Vomiting Diarrhea |

1 (33.3) 0 0 |

1 (33.3) 1 (33.3) 1 (33.3) |

2 (33.3) 2 (33.3) 1 (16.7) |

4 (33.3) 3 (25.0) 2 (16.7) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | ||||

| Hyperkalemia | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 2 (16.7) |

TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event

Multiple occurrences of the same TEAE in one individual are counted only once

No Grade 4 or 5 TEAEs were reported. One (8.3%) patient reported a Grade 3 TEAE (abdominal pain), which was also considered an SAE and was unrelated to the study drug. Grade 2 events were reported by 4 (41.7%) patients and Grade 1 events were reported by 6 (50.0%) patients. Of the total 97 TEAEs reported, most [88/97 (90.7%)] were assessed as Grade 1. Of the eight events assessed as Grade 2, six events occurred in patients in Cohort 3 and involved the respiratory, nervous, or gastrointestinal systems, were infections, or were the result of an investigation. Of all TEAEs reported, a total of 32/97 (33.0%) were classified as injection site reactions and included events with the preferred terms of injection site pain, myalgia, injection site reaction, and fatigue; all of these events were considered Grade 1.

All TEAEs that were considered related (possibly, probably, or definitely) to the study drug were Grade 1 or 2 in severity; no Grade 3, 4, or 5 treatment-related TEAEs occurred. TEAEs that were considered related to the study drug and that were reported by 2 or more patients overall included injection site pain [12 (100%) patients] and fatigue, pain, and nausea [each reported in 2 (16.7%) patients]. The incidence rates of related TEAEs were similar across cohorts; no correlation between TEAEs and the dose of GLA-SE was noted. No TEAEs were reported after the day 70 visit.

Hemoglobin and white blood cell counts dropped slightly with treatment, but no consistent or clinically significant changes were noted. Although some changes from baseline were noted for several blood chemistry parameters, including transient decreases in potassium, LDH, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), sodium, and amylase, and transient increases in ALP, the findings were not considered to be clinically significant and no differences were noted among cohorts. Some significant laboratory findings, such as elevated glucose levels, were assessed as unrelated to study treatment.

Three deaths occurred during the follow-up period; all were due to disease progression. A 60-year-old female with ovarian cancer in Cohort 2 (5 µg) died 226 days after the first dose, a 77-year-old female with ovarian cancer in Cohort 3 (10 µg) died 296 days after the first dose, and a 62-year-old male with melanoma in Cohort 3 (10 µg) died 84 days after the first dose.

Immunogenicity and efficacy of G305 treatment

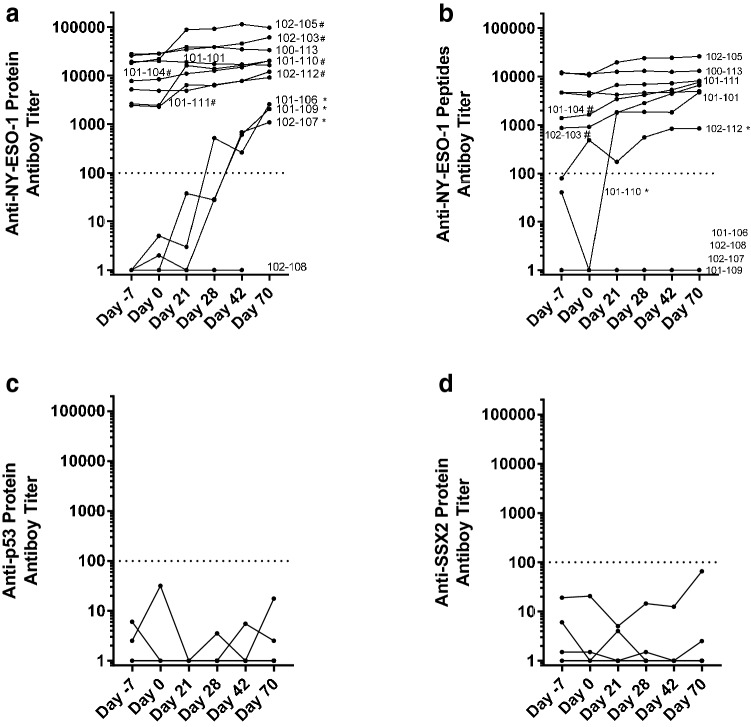

One or two baseline samples and up to four samples collected during treatment (days -7, 0, 21, 28, 42, 70) were tested. While antibody data were available from all patients, T-cell data were only available from 9/12 (75%) patients. The kinetics of antibody response to NY-ESO-1 protein and peptide pools and two control proteins, p53 and SSX2, from all patients are shown in Fig. 1. As shown in Fig. 1a, b, 9 of 12 (75%) patients developed antibody responses to NY-ESO-1 (protein or peptide pool), including 6 patients with a ≥ 4-fold rise in titers and 3 patients who were negative at baseline that became antibody positive after treatment; only 1 patient who had no anti-NY-ESO-1 antibodies prior to treatment failed to mount an antibody response following treatment (Fig. 1a and Table 3). Antibody responses to p53 and SSX2 showed no increase over time, indicating G305-induced antibody response was specific to NY-ESO-1 (Fig. 1c, d).

Fig. 1.

Antibody responses to NY-ESO-1 (protein and peptides), p53, and SSX2 protein in patients vaccinated with G305. a The kinetics of antibody response to NY-ESO-1 protein in all 12 patients. Each line represents the antibody response from an individual patient at the given time points (days -7, 0, 21, 28, 42, 70). Y-axis (log scale) shows the end-point titers of anti-NY-ESO-1 total IgG in plasma as measured by ELISA. X-axis shows the time points. b The kinetics of antibody response to NY-ESO-1 peptide pool in all patients. Patients with significantly increased antibody responses are labeled in the graphs. The “*” after patient ID indicates seroconversion, from seronegative (titer < 100) to positive (titer ≥ 100); “#” after patient ID indicates ≥ 4 fold increase in titer in response to NY-ESO-1 protein or peptide pool. c The kinetics of antibody response to p53 protein in all patients. d The kinetics of antibody response to SSX2 protein in all patients

Table 3.

Tumor characteristics, antibody responses, cellular immunogenicity, and clinical outcome

| Patient | Tumor | NY-ESO-1 (%) | Antibody | CD4 | CD8 | Clinical follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Pre | Response | Pre | Response | Pre | Response | |||

| 102–101 | Synovial | 100 | + | = | + | = | – | – | PD d162 |

| 102–103 | Ovarian | 100 | + | ++ | + | = | – | – | PD d307 |

| 101–104 | Ovarian | 15 | + | ++ | N/E | N/E | N/E | N/E | SD d432+ |

| 102–105 | Ovarian | 99 | + | ++ | + | ++ | – | ++ | PD d161 |

| 101–106 | Synovial | 95 | – | ++ | N/Ea | (++) | – | – | SD d377+ |

| 102–107 | Ovarian | 25 | – | ++ | – | ++ | – | – | PD d70 (239) |

| 102–108 | Ovarian | 12 | – | – | – | – | – | – | PD d85 (113) |

| 101–109 | Melanoma | 60 | – | ++ | N/Ea | (++) | – | – | PD d50 (295) |

| 101–110 | Synovial | 70 | + | ++ | + | = | – | ++ | PD d70 |

| 101–111 | Ovarian | 60 | + | ++ | – | ++ | – | ++ | PD d100 |

| 100–113 | Ovarian | 70 | + | = | + | = | – | ++ | PD d195 |

| 102–112 | Urothelial | 20 | + | ++ | + | ++ | – | – | SD d367+ |

Patients are listed in order of enrollment and divided by dosage group. Pretreatment NY-ESO-1 expression in tumor samples is shown in the first data column, followed by immunogenicity findings and clinical outcome

A “+” in the “Pre” column indicates a pre-existing measurable immune response.

A “++” in the “Response” indicates for antibody: 4-fold rise or newly positive response; T cell: ELISPOT > 50 spots and a > 2-fold rise

An “=“ indicates a pre-existing response that did not boost. N/E not evaluable

Follow-up: PD progressive disease, SD stable disease. A ‘+’ indicates stable disease as of last contact and parenthetical numbers show days of survival in the patients who died during follow-up

aBaseline T-cell data not available. These patients did not have pre-existing antibody responses but developed them during treatment, which suggests absence of CD4 T cells at baseline

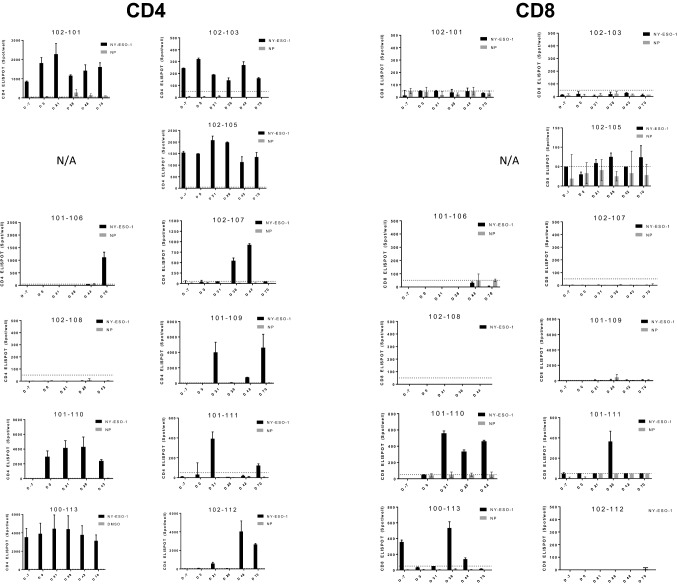

The CD4 and CD8 T-cell ELISPOT data from all patients with available PBMC is shown in Fig. 2. The presence or absence of baseline CD4/CD8 T-cell response and vaccine-induced increase ( ≥ 2-fold induction) is summarized in Table 3. Overall, CD4 T-cell increases were observed with vaccination in 4 of 9 (44.4%) evaluable patients. Two additional patients had no pre-existing antibodies and they seroconverted; their CD4 T-cell responses were not evaluable at baseline but they had CD4 T-cell responses after vaccination, implying they responded as well, suggesting that a total of 6 of 11 patients (54.5%) may have developed CD4 T-cell responses with vaccination (Table 3). CD8 T-cell responses were boosted in 4 of 11 (36.4%) patients following injections (Table 3). No correlation between dose of GLA-SE and immune response induction was observed and there was no association between induction of immune response and clinical benefit in this small cohort of patients.

Fig. 2.

CD4 and CD8 T cell response to NY-ESO-1 and control antigen in patients vaccinated with G305. Shown are CD4 and CD8 ELISPOT data for all patients with available samples. CD4 and CD8 T cells were isolated from PBMC and stimulated in vitro with NY-ESO-1 peptide or control irrelevant antigen (nucleoprotein, NP) before the analysis by IFNγ ELISPOT. The black bars represent the number of spots per well (with 50,000 CD4 or CD8 T cells) in T cells stimulated with NY-ESO-1. The gray bars represent the number of spots per well in T cells stimulated with NP. The error bar indicates standard deviation (SD). The dotted line indicates the cutoff for baseline (50 spots per well). Patient 3 had no PBMC collected. Patients 7 and 8 had no CD8 NP data

Pre-treatment and post-treatment leukapheresis samples on day 70 were also collected from some patients and used for ICS evaluation. As shown in Supplemental Fig. 1A, antigen-specific CD4 T-cell responses, as measured by CD40L expression, were increased in three out of the five patients who were tested. Further evaluation showed that the expanded CD4 T cells after vaccination with G305 were multi-functional, secreting IL-2, TNFα, and IFN-γ, in addition to increased CD40L expression (Supplemental Fig. 1B and 1C). Enhanced CD8 T-cell response to IFN-γ was also augmented in this patient (Supplemental Fig. 1C).

Overall, 8 of 12 (67%) patients were stable for 3 months or more, including all patients in Cohort 1, 2 of 3 patients in Cohort 2, and 3 of 6 patients in Cohort 3. At the end of 1 year, 3 of 8 (38%) patients remained stable, which included 1 patient in each cohort. One patient had a CA-125 response on Day 70 based on Gynecological Cancer Intergroup criteria.

Discussion

In this first-in-human Phase 1 study in 12 patients with unresectable metastatic solid tumors expressing NY-ESO-1, G305 was shown to be safe and immunogenic at all doses of GLA-SE studied. The most common AEs were mild (Grade 1) and were typical for GLA-containing vaccines, based on prior experience with other antigens, and included fever, fatigue, chills, myalgia, and injection site reactions. Except for injection site reactions, most AEs were considered unrelated to study treatment. Preclinical studies have shown that GLA-SE induces inflammatory cytokine and chemokine genes at injection sites [16] and not surprisingly, the most common AE in this study, which was reported in all patients, was injection site reaction. Three deaths and two SAEs occurred, all of which were unrelated to study treatment. There were no DLTs or AEOSIs in the study, and the maximum planned dose of 10-µg GLA-SE was attained; the MTD of G305 was not reached in this study. Furthermore, there were no significant findings in any safety laboratory measurements.

As with preclinical studies and other clinical trials with GLA-adjuvants, immunogenicity results demonstrated that G305 acts to augment the immune response, primarily in the humoral and CD4 T-cell responses, with a few patients developing a detectable CD8 T-cell response. ELISPOT (after in vitro stimulation) was the primary readout as it was more sensitive than ICS. However, ICS can evaluate multiple cytokine secretion from the same cells and the phenotype of the antigen-specific T cells. Out of the subset of patients with both ICS and ELISPOT data, the results were not always consistent between ELISPOT and ICS, as some low-level responses detected in ELISPOT was not measurable in ICS. On the contrary, augmentation of immune response in one patient (102–105), which was clearly significant in ICS (Supplemental Fig. 1), was not detected in CD4 ELISPOT as the response was probably too high at baseline and saturated the signal.

There was no identifiable trend with regard to disease stability or progression and percentage of NY-ESO-1 expression at study entry, disease stage, or time from diagnosis date; however, these may be explored in future studies to target the subjects with this immunotherapeutic who would most benefit. Eight of 12 (67%) patients had stable disease at 3 months after administration of the first dose of the study drug. Overall, patients had a median progression-free survival of 5.3 months and 75% of patients were alive at 1 year after enrollment, which may represent clinical benefit from G305 in this group of patients with advanced solid tumors.

The efficacy of vaccines for cancer has been generally disappointing to date [35]. On the one hand, it has been difficult to identify tumor-specific target antigens that are unique to cancer cells and on the other, the availability of modern adjuvants for clinical use that can induce potent antibody and T-cell responses is very limited [36–38]. Cancer-testis antigens are selectively expressed in tumors and, therefore, regarded as ideal target for immunotherapy, with NY-ESO-1 standing out in terms of its immunogenicity [5]. Previously, NY-ESO-1 protein-based vaccines have been adjuvanted with different adjuvant including CpG (TLR9 agonist), poly-ICLC (TLR3 agonist), Montanide (water-in-oil emulsion) and Iscomatrix (saponin) and shown to induce CD4 T-cell and antibody responses, as well as CD8 T-cell responses [5, 14, 29–31]. In these and other studies, NY-ESO-1-specific antibodies were induced in the majority of patients, whereas induction of CD4 T cells was observed in 15–100% of patients, and induction of CD8 T cells in 0–50%. Overall the induction rate of antibody (75%) and T-cell responses (44% CD4 and 54% CD8) by G305 is non-inferior to published vaccine trials targeting NY-ESO-1. However, it should be recognized that in most studies, PBMC were sensitized ex vivo for several days for up to 2 weeks before performing ELISPOT. Doses of recombinant NY-ESO-1 protein varied from 100 to 400 μg and patients were given up to six injections. Given the variability in antigen content and dosing between the different vaccine studies, the generally small patient numbers, and the observation that induction of immune responses is influenced by disease state and pre-existing immunity, a direct comparison of the immunogenicity and efficacy of the different NY-ESO-1 vaccines is not very meaningful. However, the level of G305-induced antibody and T cell responses together with the excellent safety profile warrants further clinical testing of this vaccine candidate. To this end, G305 will be incorporated into a novel immunotherapy, whereby CD8 T cells are first primed with a dendritic cell targeting NY-ESO-1-expressing vector (LV305) and the immune response is then boosted with G305 in a heterologous prime-boost approach. This regimen consists of several cycles designed to generate high levels of Th1-type CD4 T cells that can provide support to the development, activation, and expansion of CD8 T lymphocytes. This is critical, as immediate dysfunction of vaccine-elicited CD8+ T cells primed in the absence of CD4+ T cells has been shown [39]. The combination product, CMB305, is under investigation in separate phase 1 (NCT02387125) and phase 2 (NCT02609984) clinical trials, evaluating dosing regimens in various solid tumors and coadministration with atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1) in patients with advanced synovial sarcomas or liposarcomas expressing the NY-ESO-1 cancer-testis antigen [40].

Conclusions

This first-in-human phase 1 study of G305 demonstrates its safety and ability to generate antibody and CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses in patients with NY-ESO-1-positive tumors. The favorable safety profile and potential for clinical benefit observed in this study warrant further exploration of G305 in combination with other vaccine modalities and immunomodulating agents.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and staff at each clinical site, Kevin Tuballes for technical help as part of the Human Immune Monitoring Center at Mount Sinai, and Karen Rappaport for assistance with drafting the manuscript as part of the team at Immune Design.

Abbreviations

- AE

Adverse event

- AESI

Adverse event of special interest

- ALP

Alkaline phosphatase

- BCG

Bacillus Calmette–Guerin

- CpG

Cytosine phosphate–guanine

- CT

Computed tomography

- CTCAE

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

- DLT

Dose-limiting toxicity

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- ELISPOT

Enzyme-linked immunospot assay

- GLA

Glucopyranosyl lipid A

- GLA-SE

Glucopyranosyl lipid A in stable emulsion

- GM-CSF

Granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- GMT

Geometric mean titers

- HLA

Human leukocyte antigen

- ICS

Intracellular cytokine staining

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- IM

Intramuscularly

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- MedDRA

Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities

- MTD

Maximum tolerated dose

- MyD88

Myeloid differentiation primary response 88

- NCI

National Cancer Institute USA

- NF-kB

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- NLRP3

NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- NY-ESO-1

New York esophageal squamous cell carcinoma 1

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- Poly-ICLC

Polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid–poly-l-lysine carboxymethylcellulose

- RECIST

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- SAE

Serious adverse events

- SD

Standard deviation

- SE

Stable emulsion

- SEB

Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin type B

- SMC

Safety Monitoring Committee

- TAA

Tumor-associated antigens

- TEAE

Treatment emergent adverse events

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- TRIF

TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β

- ULN

Upper limit of normal

Author contributions

Trial conception and design: AM, SE, RK, KO. Acquisition of data: AM, SE, SG, SK-S, HL, RK, KO. Analysis and interpretation of data: AM, SE, SG, HL, JM, RK, KO. Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: AM, RK, JM. Study supervision: AM, SE, RK, KO.

Funding

This research was funded by Immune Design Corp.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Hailing Lu, Richard Kenney, and Jan ter Meulen are full-time employees and shareholders of Immune Design Corp. Sacha Gnjatic has received research support from Immune Design Corp. The authors declare that there are no other conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and ethical standards

This trial is registered in the USA under the ClinicalTrials.gov identifier (NCT number): NCT02015416. Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) reviewed and approved the protocol, all protocol amendments, informed consent documents, and written study materials before their use.

Institutional approvals

Roswell Park Cancer Institute (sponsor protocol #IDC-G305-2013-001 and RPCI protocol # PH 244813); Scottsdale Healthcare (WIRB Protocol Number: 20131768; WIRB Study Number: 1142287); Karmanos Cancer Institute (WIRB Protocol Number: 20131768; WIRB Study Number: 1143287); H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Ctr & Research Inst, Inc. (sponsor protocol #IDC-G305-2013-001–MCC 17622). The Karmanos Cancer Institute did not identify suitable patients to enroll on the trial.

Human/animal rights statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

All patients provided informed consent prior to study enrollment at the screening visit. Patients also agreed on the use of patient data for research and publication.

Footnotes

Note on previous publication: Preliminary data of this study was presented at the 2015 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) meeting, Chicago, IL, USA, Abstract # 152974 [1].

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mahipal A, Odunsi K, Gnjatic S, Kim-Schulze S, Kenney RT, Ejadi S. A first-in-human phase 1 dose-escalating trial of G305 in patients with solid tumors expressing NY-ESO-1. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3073. doi: 10.1200/jco.2015.33.15_suppl.3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mellman I, Coukos G, Dranoff G. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature. 2011;480:480–489. doi: 10.1038/nature10673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melief CJ, van Hall T, Arens R, Ossendorp F, van der Burg SH. Therapeutic cancer vaccines. J Clin Investig. 2015;125:3401–3412. doi: 10.1172/JCI80009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gnjatic S, Nishikawa H, Jungbluth AA, Gure AO, Ritter G, Jager E, Knuth A, Chen YT, Old LJ. NY-ESO-1: review of an immunogenic tumor antigen. Adv Cancer Res. 2006;95:1–30. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(06)95001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas R, Al-Khadairi G, Roelands J, Hendrickx W, Dermime S, Bedognetti D, Decock J. NY-ESO-1 based immunotherapy of cancer: current perspectives. Front Immunol. 2018;9:947. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park TS, Groh EM, Patel K, Kerkar SP, Lee CC, Rosenberg SA. Expression of MAGE-A and NY-ESO-1 in primary and metastatic cancers. J Immunother. 2016;39:1–7. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gjerstorff MF, Andersen MH, Ditzel HJ. Oncogenic cancer/testis antigens: prime candidates for immunotherapy. Oncotarget. 2015;6:15772–15787. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sabado RL, Pavlick A, Gnjatic S, et al. Resiquimod as an immunologic adjuvant for NY-ESO-1 protein vaccination in patients with high-risk melanoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:278–287. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Odunsi K, Matsuzaki J, Karbach J, et al. Efficacy of vaccination with recombinant vaccinia and fowlpox vectors expressing NY-ESO-1 antigen in ovarian cancer and melanoma patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:5797–5802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117208109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fonteneau JF, Brilot F, Munz C, Gannage M. The tumor antigen NY-ESO-1 mediates direct recognition of melanoma cells by CD4+ T cells after intercellular antigen transfer. J Immunol. 2016;196:64–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jager E, Chen YT, Drijfhout JW, et al. Simultaneous humoral and cellular immune response against cancer-testis antigen NY-ESO-1: definition of human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A2-binding peptide epitopes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:265–270. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.2.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jager E, Nagata Y, Gnjatic S, et al. Monitoring CD8 T cell responses to NY-ESO-1: correlation of humoral and cellular immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4760–4765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuan J, Adamow M, Ginsberg BA, et al. Integrated NY-ESO-1 antibody and CD8+ T-cell responses correlate with clinical benefit in advanced melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16723–16728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110814108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma P, Bajorin DF, Jungbluth AA, Herr H, Old LJ, Gnjatic S. Immune responses detected in urothelial carcinoma patients after vaccination with NY-ESO-1 protein plus BCG and GM-CSF. J Immunother. 2008;31:849–857. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181891574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coler RN, Bertholet S, Moutaftsi M, et al. Development and characterization of synthetic glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant system as a vaccine adjuvant. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambert SL, Yang CF, Liu Z, Sweetwood R, Zhao J, Cheng L, Jin H, Woo J. Molecular and cellular response profiles induced by the TLR4 agonist-based adjuvant glucopyranosyl lipid A. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e51618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orr MT, Duthie MS, Windish HP, et al. MyD88 and TRIF synergistic interaction is required for TH1-cell polarization with a synthetic TLR4 agonist adjuvant. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:2398–2408. doi: 10.1002/eji.201243124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desbien AL, Reed SJ, Bailor HR, et al. Squalene emulsion potentiates the adjuvant activity of the TLR4 agonist, GLA, via inflammatory caspases, IL-18, and IFN-gamma. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:407–417. doi: 10.1002/eji.201444543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seydoux E, Liang H, Dubois Cauwelaert N, Archer M, Rintala ND, Kramer R, Carter D, Fox CB, Orr MT. Effective combination adjuvants engage both TLR and inflammasome pathways to promote potent adaptive immune responses. J Immunol. 2018;201:98–112. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duthie MS, Coler RN, Laurance JD, et al. Protection against Mycobacterium leprae infection by the ID83/GLA-SE and ID93/GLA-SE vaccines developed for tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2014;82:3979–3985. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02145-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lambert SL, Aslam S, Stillman E, et al. A novel respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) F subunit vaccine adjuvanted with GLA-SE elicits robust protective TH1-type humoral and cellular immunity in rodent models. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0119509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clegg CH, Roque R, Van Hoeven N, Perrone L, Baldwin SL, Rininger JA, Bowen RA, Reed SG. Adjuvant solution for pandemic influenza vaccine production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:17585–17590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207308109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baldwin SL, Bertholet S, Reese VA, Ching LK, Reed SG, Coler RN. The importance of adjuvant formulation in the development of a tuberculosis vaccine. J Immunol. 2012;188:2189–2197. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson RF, Kurup D, Hagen KR, et al. An inactivated rabies virus-based Ebola vaccine, FILORAB1, adjuvanted with glucopyranosyl lipid A in stable emulsion confers complete protection in nonhuman primate challenge models. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:S342–S354. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pillet S, Aubin E, Trepanier S, Poulin JF, Yassine-Diab B, Ter Meulen J, Ward BJ, Landry N. Humoral and cell-mediated immune responses to H5N1 plant-made virus-like particle vaccine are differentially impacted by alum and GLA-SE adjuvants in a phase 2 clinical trial. NPJ Vaccines. 2018;3:3. doi: 10.1038/s41541-017-0043-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Falloon J, Yu J, Esser MT, Villafana T, Yu L, Dubovsky F, Takas T, Levin MJ, Falsey AR. An adjuvanted, postfusion F protein-based vaccine did not prevent respiratory syncytial virus illness in older adults. J Infect Dis. 2017;216:1362–1370. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Treanor JJ, Essink B, Hull S, Reed S, Izikson R, Patriarca P, Goldenthal KL, Kohberger R, Dunkle LM. Evaluation of safety and immunogenicity of recombinant influenza hemagglutinin (H5/Indonesia/05/2005) formulated with and without a stable oil-in-water emulsion containing glucopyranosyl-lipid A (SE+GLA) adjuvant. Vaccine. 2013;31:5760–5765. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Odegard JM, Flynn PA, Campbell DJ, Robbins SH, Dong L, Wang K, Ter Meulen J, Cohen JI, Koelle DM. A novel HSV-2 subunit vaccine induces GLA-dependent CD4 and CD8 T cell responses and protective immunity in mice and guinea pigs. Vaccine. 2016;34:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.10.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valmori D, Souleimanian NE, Tosello V, et al. Vaccination with NY-ESO-1 protein and CpG in Montanide induces integrated antibody/Th1 responses and CD8 T cells through cross-priming. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:8947–8952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703395104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein O, Davis ID, McArthur GA, et al. Low-dose cyclophosphamide enhances antigen-specific CD4(+) T cell responses to NY-ESO-1/ISCOMATRIX vaccine in patients with advanced melanoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2015;64:507–518. doi: 10.1007/s00262-015-1656-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen JL, Dawoodji A, Tarlton A, et al. NY-ESO-1 specific antibody and cellular responses in melanoma patients primed with NY-ESO-1 protein in ISCOMATRIX and boosted with recombinant NY-ESO-1 fowlpox virus. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E590–601. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabbatini P, Tsuji T, Ferran L, et al. Phase I trial of overlapping long peptides from a tumor self-antigen and poly-ICLC shows rapid induction of integrated immune response in ovarian cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:6497–6508. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wada H, Isobe M, Kakimi K, et al. Vaccination with NY-ESO-1 overlapping peptides mixed with Picibanil OK-432 and montanide ISA-51 in patients with cancers expressing the NY-ESO-1 antigen. J Immunother. 2014;37:84–92. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robbins PF, Morgan RA, Feldman SA, et al. Tumor regression in patients with metastatic synovial cell sarcoma and melanoma using genetically engineered lymphocytes reactive with NY-ESO-1. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:917–924. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Melero I, Gaudernack G, Gerritsen W, et al. Therapeutic vaccines for cancer: an overview of clinical trials. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11:509–524. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheever MA, Allison JP, Ferris AS, et al. The prioritization of cancer antigens: a national cancer institute pilot project for the acceleration of translational research. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5323–5337. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tagliamonte M, Petrizzo A, Tornesello ML, Buonaguro FM, Buonaguro L. Antigen-specific vaccines for cancer treatment. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10:3332–3346. doi: 10.4161/21645515.2014.973317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gouttefangeas C, Rammensee HG. Personalized cancer vaccines: adjuvants are important, too. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2018;67:1911–1918. doi: 10.1007/s00262-018-2158-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Provine NM, Larocca RA, Aid M, et al. Immediate dysfunction of vaccine-elicited CD8+ T cells primed in the absence of CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2016;197:1809–1822. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pollack SM. The potential of the CMB305 vaccine regimen to target NY-ESO-1 and improve outcomes for synovial sarcoma and myxoid/round cell liposarcoma patients. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2018;17:107–114. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2018.1419068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.