Abstract

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a leading cause of cancer death worldwide. Lack of symptoms results in late detection and increased mortality. Inflammation, including complement activation, plays an important role in tumorigenesis.

Experimental design

The concentrations of nine proteins of the lectin pathway of the complement system were determined using time-resolved immunofluorometric assays. The first cohort investigated comprised a matched case–control study of 95 patients with CRC, 48 patients with adenomas and 48 individuals without neoplastic findings. Based on the results, Collectin-liver 1 (CL-L1), M-ficolin and MAp44 were determined as the most promising biomarkers and were subsequently evaluated in a case–control study of 99 CRC patients, 196 patients with adenomas and 696 individuals without neoplastic bowel lesions.

Results

Using logistic regression, we found that CL-L1, M-ficolin and MAp44 levels could significantly distinguish between patients with CRC, patients with adenomas and individuals without neoplastic bowel lesions. Higher levels of CL-L1 or MAp44 were associated with lower odds of CRC (OR 0.42 (0.25–0.70) p = 0.0003 and OR 0.39 (0.23–0.65) p = 0.0003, respectively), whereas higher levels of M-ficolin were associated with higher odds of CRC compared to individuals without CRC (OR 1.94 (1.46–2.59) p < 0.0001). The combination of CL-L1, M-ficolin and MAp44 in a test of CRC versus individuals without CRC resulted in 36 % sensitivity at 83 % specificity.

Conclusion

CL-L1, M-ficolin and MAp44 in combination discriminate between CRC and patients without cancer. The markers did not have sufficient discriminatory value for CRC detection, but may prove useful for screening when combined with other markers.

Keywords: Cancer, Complement system, Lectin pathway, Biomarkers

Introduction

Every year, more than 1.2 million patients are diagnosed with colorectal cancer (CRC) worldwide, and CRC is the second leading cause of death from cancer in developed countries [1]. Often there is a lack of symptoms in the early stages of CRC. A biomarker or combinations of biomarkers for CRC and adenomas (premalignant lesions) would be beneficial in detection of the disease at an early stage and thus improve survival [2]. A sensitive blood-based biomarker could overcome compliance issues, but no soluble biomarker has yet been found effective for population screening [3].

One important function of the immune system is to generate inflammation as a means of defending the body against foreign structures as found on pathogens or on altered self (cancer or apoptotic cells) [4]. However, an increasing number of studies report an ambiguous role of inflammation in tumorigenesis [4–7]. This report focuses on proteins of the complement system, which is a strong inflammation-generating system of the innate immune system [8]. This is a part of the innate defense system that may respond directly to pathogens via activation of an enzymatic cascade leading to destruction of microorganisms. Three different pathways initiate complement activation: the classical, the alternative and the lectin pathway [9]. The present paper focuses on the lectin pathway, which is initiated by six different pattern recognition molecules (PRMs): mannan-binding lectin (MBL), H-ficolin, L-ficolin or M-ficolin (also termed ficolin-3, ficolin-2 and ficolin-1, respectively), as well as the two recently identified collectins, CL-L1 and CL-K1, also termed CL-10 and CL-11 [10, 11]. Most CL-K1 and CL-L1 seem to be found in a complex of the two proteins [12]. All these PRMs are humoral proteins circulating in complexes with MBL-associated serine proteases (MASP-1, MASP-2 and MASP-3) and small, non-enzymatic MBL-associated proteins (MAps), MAp19 and MAp44 (also termed sMAP and MAP-1, respectively) [9]. The MASPs become activated when the PRMs bind their targets, e.g., pathogen-associated molecular patterns. First, MASP-1 is activated. Then, it transactivates MASP-2, which further cleaves the complement factors C4 and C2, hence forming a C3 convertase. The C3 convertase cleaves C3 to C3b, which is deposited on nearby surfaces. C3b functions as an opsonin, facilitating phagocytosis of opsonized pathogens by macrophages and neutrophils, and is also a component of the C5 convertase that is formed. C3a and C5a are small fragments, generated when C3 and C5 are cleaved, and they are potent inflammatory mediators. C5b assembles with C6–C9 and creates a pore, a membrane attack complex, in the cell membrane of the pathogen, which induces cell lysis.

The role of various parts of the immune system in cancer has been extensively studied [7, 13]. However, little is known about the role of complement in inhibition or promotion of cancer growth. Markiewski and colleagues [14] studied the impact of complement in a mouse model of cervical cancer and found that blockade of C5a resulted in efficient reduction of tumor growth, as was also observed in mice deficient in the C5a-receptor. Regarding the lectin pathway, the roles of MBL and MASP-2 in cancer have been studied the most. The lectin pathway activity and levels of MBL and MASP-2 were reported significantly increased in patients with CRC as compared to blood donors [15, 16]. MBL levels were significantly higher among pediatric patients with solid tumors compared to age- and sex-matched controls, and MASP-2 levels were significantly higher among children diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and CNS tumors [17]. Poor survival and recurrence of CRC were associated with high levels of MASP-2 [16]. In contrast, high MASP-2 levels were associated with increased event-free survival in pediatric patients with hematologic cancers [18]. Studies of ficolins and cancer are limited. H-ficolin was suggested as a candidate biomarker for ovarian cancer [19], and transcription of the FCN3 gene (encoding H-ficolin) was found decreased in hepatocellular and squamous lung cell carcinomas [20, 21]. Increased concentrations of H-ficolin were found in pediatric patients with acute leukemia compared to children with other malignancies [22]. Szala et al. [23] reported significantly higher levels of H- and L-ficolin in patients with ovarian cancer compared to controls. One study found median M-ficolin concentrations among pediatric cancer patients to be similar to the concentrations in age-matched controls [24].

The present study evaluates the associations of CL-L1, H-ficolin, M-ficolin, MBL, MAp19, MAp44, MASP-1, MASP-2 and MASP-3 concentrations with CRC. The aim of the present study was to identify proteins from the lectin pathway of complement as blood-based biological markers in the screening for CRC.

Patients and methods

Study 1

A pilot, matched case–control study including 191 patients consisted of 47 patients with recurrent CRC, 48 patients without recurrence 36 months after operation for the primary malignant bowel lesion, 48 patients with adenomas and 48 healthy individuals. All patients and healthy individuals were matched by age and gender. Serum samples from the CRC patients originated from a monitoring study [25] with patients scheduled for elective resection. Blood samples included in this pilot study were collected just before the operation and 3–36 months after operation, dependent on the time of recurrence. The serum samples from patients with adenomas and the samples from individuals deemed healthy after examination were collected prior to large bowel endoscopy [26]. The individuals included had symptoms associated with CRC and were referred to sigmoidoscopy and/or colonoscopy at one of six participating Danish hospitals (i.e., the hospitals in Bispebjerg, Hvidovre, Glostrup, Odense, Aarhus and Randers). The healthy individuals had no findings by endoscopy and did not suffer from diabetes, rheumatic disease, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, alcoholic liver disease, cirrhosis, chronic obstructive lung disease, asthma or chronic bronchitis. We performed analyses of nine proteins of the lectin pathway of the complement system, as described below.

Study 2

Following the results obtained in study 1, we carried out a case–control study of 991 patients. Of these, 99 were CRC patients, 196 had adenomas and 696 individuals had no neoplastic finding (including patients with comorbidities and other findings in colon). The serum samples were selected from a large, prospective study of 4,770 individuals, who were referred to first-time colonoscopy at one of the seven participating Danish hospitals (Bispebjerg, Hvidovre, Hilleroed, Horsens, Aarhus, Randers and Herning). Inclusion criteria were age over 18 years, symptoms associated with CRC, and none of the individuals had previously undergone colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy. Exclusion criteria were a previous CRC diagnosis, adenomas or any genetic dispositions for hereditary non-polyposis CRC or familial adenomatous polyposis. Patients with other prior cancer diagnoses were also excluded; however, in the dataset out of the 991 individuals, there was one patient with prior malignant melanoma and one with multiple myeloma. Patients were also excluded if they did not comply with the protocol outlines. The individuals were only included in the study after having signed an informed consent form. The study was performed according to the Helsinki II declaration and was approved by The Ethics Committee of the Capital Region of Denmark (H-3-2009-110) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (2008-41-2252).

A blood sample comprising 44 ml was collected from a peripheral vein into endotoxin-free tubes (Becton–Dickinson, UK) prior to colonoscopy: 20 ml was drawn into EDTA tubes (cat. #367525), 9 ml into citrate vials (cat. #367704) and 15 ml into tubes with coagulation enhancer (cat. #367896). The latter was incubated at ambient temperature for one hour before centrifugation. After centrifugation at 3,000 g for 10 min at room temperature, the supernatants were pipetted into CM-Lab endotoxin-free cryotubes (Almeco A/S, Denmark cat. #01-2000p). The blood samples were labeled with barcodes and stored at −80 °C with 24/7 surveillance. For the present study, only the serum samples were used. Blinded to sample identity, analyses were carried out for the three complement proteins: CL-L1, M-ficolin and MAp44, selected on the basis of the results of the pilot study (study 1).

Assays for proteins of the lectin pathway

All the samples from study 1 were analyzed for CL-L1 [11], H-ficolin [27], M-ficolin [28], MAp19 [29], MAp44 [30], MASP-1 [31], MASP-2 [32], MASP-3 [30] and MBL [33], while the samples in study 2 were tested only for CL-L1, M-ficolin and MAp44. Detailed descriptions of the assays are found in the reference given for each protein. The determinations were not influenced by repeated freezing and thawing of the sample. In brief, all protein concentrations were measured by time-resolved immunofluorometric assays (TRIFMAs). The samples were thawed at 4 °C overnight and pre-diluted 1/4 in Tris-buffered saline (10 mM Tris, 145 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) (TBS). Freeze–thaw cycles were thereafter kept at a minimum. Dilutions of the samples, standard plasma and quality controls (see below) were done using a PerkinElmer MultiProbe II robotic liquid handling system. Diluted samples were transferred in duplicate to microtitre plates by the robot as well. The TRIFMAs proceed as traditional sandwich immunoassays with the primary antibody coated onto microtitre wells and the antigen caught during incubation of the diluted sample. The bound antigen was subsequently detected by biotin-labeled antibody followed by europium-labeled streptavidin. Following the addition of enhancement solution, the fluorescence of the europium was measured by time-resolved fluorometry using a Victor3 (PerkinElmer) for study 1 and Victor X5 (PerkinElmer) for study 2. All samples were analyzed in duplicate, and analysis was repeated if the coefficient of variation (%CV) was more than 20 % between the two wells. The plate was repeated if the quality controls varied with %CV > 15 as compared to a collection of previously measured values. If the concentration of the samples exceeded the highest value of the standard curve, the assays were repeated at higher dilution. The determinations were performed at Department of Biomedicine, Aarhus University, Denmark.

Statistics

Associations between the variables were evaluated by the Spearman rank correlation. CRC patients with recurrence were compared to those without using a two-sample t test with equal variances. Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare basic characteristics between the groups in study 2. Logistic regression analysis was used in both studies modeling the probability for CRC. Conditional logistic regression analysis was used for study 1. Marker levels were log-transformed using log base 2, implying that odds ratios (OR) are for twofold differences in marker levels. Sensitivities and specificities were calculated based on the multivariate logistic regression for study 2. Goodness of fit was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All calculations have been done with SAS (v9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, N.C., USA).

Results

Study 1

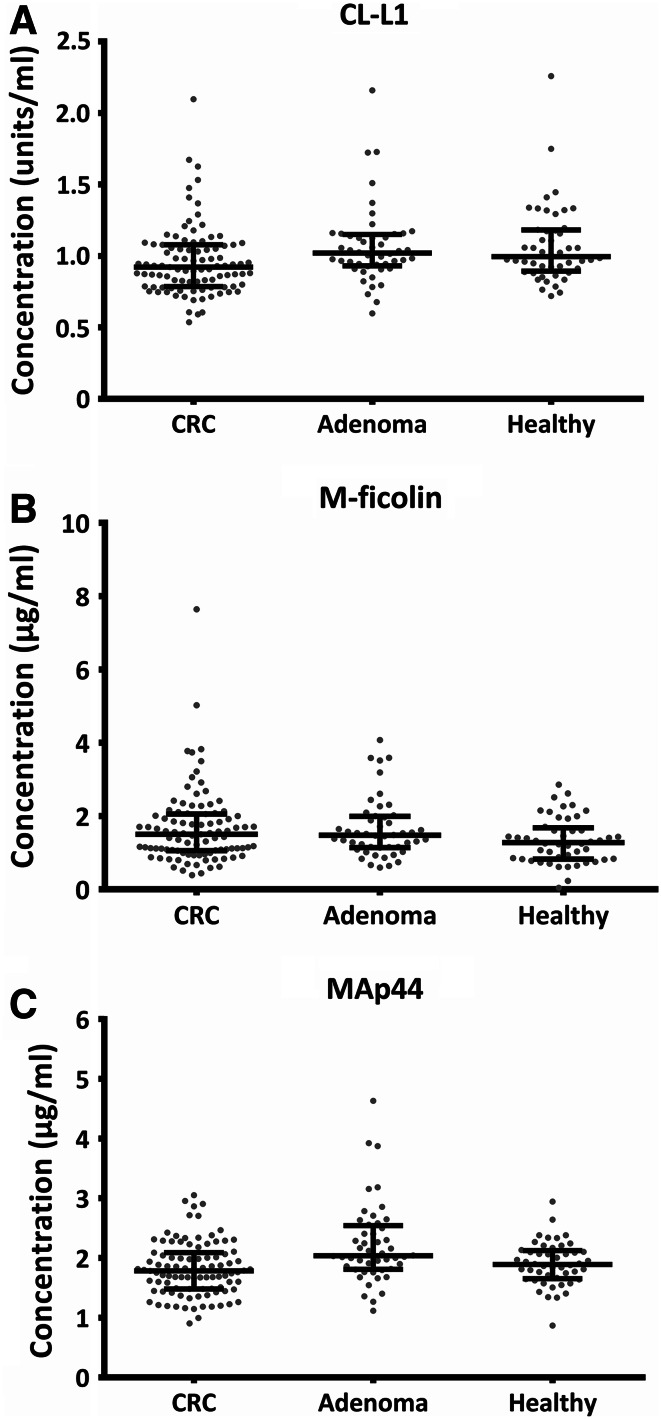

The concentration of nine different proteins of the lectin pathway in patients with CRC, patients with adenoma and healthy individuals was measured. Using logistic regression, we found that the concentrations of several of the proteins differed significantly between CRC and non-CRC, i.e., adenomas and healthy individuals. The distribution of the concentrations of CL-L1, M-ficolin and MAp44 for CRC patients, patients with adenomas and healthy individuals is shown in Fig. 1. Higher levels of CL-L1 were associated with significantly lower odds of CRC when comparing CRC to both non-CRC (OR 0.22 (0.09–0.57) p = 0.002), healthy individuals (OR 0.23 (0.08–0.70) p = 0.009) and adenomas (OR 0.25 (0.09–0.75) p = 0.013) (Table 1). Higher levels of MAp44 were associated with significantly lower odds of CRC with respect to both non-CRC (OR 0.24 (0.10–0.57) p = 0.001) and adenomas (OR 0.14 (0.05–0.39) p = 0.0002), while higher levels of MAp44 were associated with higher odds of adenomas compared to healthy individuals (OR 5.29 (1.42–19.64) p = 0.013). On the other hand, higher levels of M-ficolin were significantly associated with both higher odds of CRC (OR 1.64 (1.05–2.57) p = 0.03) and higher odds of adenomas when compared to healthy individuals (OR 1.64 (1.05–2.57) p = 0.03). Logistic regression analyses of the six other lectin pathway proteins, H-ficolin, MBL, MAp19, MASP-1, MASP-2 and MASP-3, were also conducted in study 1 and are presented in Table 1. Only marginal significance for any comparisons was seen for H-ficolin, MAp19 and MASP-1 (Table 1). We found no significant difference of the tested protein concentrations between CRC patients with or without recurrence (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

The concentration of CL-L1 (a), M-ficolin (b) and MAp44 (c) in serum of individuals in study 1. Scatter plots of the concentrations divided into separate groups of CRC patients (n = 95), patients with adenomas (n = 48) and healthy individuals (n = 48). Lines indicate mean and interquartile range (25th–75th percentiles). Each dot represents an individual

Table 1.

Univariate logistic analysis of all 9 markers of study 1: CL-L1, M-ficolin and MAp44 (which were selected for study 2), H-ficolin, MBL, MAp19, MASP-1, MASP-2 and MASP-3

| Variable | CRC versus non-CRC | CRC versus healthy | CRC versus adenoma | Adenoma versus healthy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95 % CI) | P | OR (95 % CI) | P | OR (95 % CI) | P | OR (95 % CI) | P | |

| CL-L1 | 0.22 (0.09–0.57) | 0.002 | 0.23 (0.08–0.70) | 0.009 | 0.25 (0.09–0.75) | 0.013 | 0.93 (0.27–3.21) | 0.91 |

| M-ficolin | 1.28 (0.89–1.83) | 0.19 | 1.64 (1.05–2.57) | 0.030 | 0.93 (0.58–1.50) | 0.77 | 1.64 (1.05–2.57) | 0.030 |

| MAp44 | 0.24 (0.10–0.57) | 0.001 | 0.47 (0.17–1.36) | 0.16 | 0.14 (0.05–0.39) | 0.0002 | 5.29 (1.42–19.64) | 0.013 |

| H-ficolin | 0.53 (0.28–1.01) | 0.05 | 0.72 (0.30–1.71) | 0.46 | 0.30 (0.12–0.76) | 0.01 | 1.78 (0.80–3.98) | 0.16 |

| MBL | 1.06 (0.94–1.20) | 0.32 | 1.09 (0.95–1.26) | 0.22 | 1.03 (0.89–1.19) | 0.70 | 1.07 (0.90–1.26) | 0.46 |

| MAp19 | 0.60 (0.37–0.97) | 0.04 | 0.72 (0.41–1.27) | 0.26 | 0.50 (0.27–0.92) | 0.03 | 1.51 (0.72–3.14) | 0.27 |

| MASP-1 | 0.57 (0.33–0.99) | 0.04 | 0.55 (0.27–1.12) | 0.10 | 0.54 (0.27–1.08) | 0.08 | 1.05 (0.53–2.09) | 0.89 |

| MASP-2 | 1.31 (0.82–2.07) | 0.26 | 1.25 (0.71–2.19) | 0.43 | 1.34 (0.78–2.33) | 0.29 | 0.91 (0.47–1.77) | 0.79 |

| MASP-3 | 0.65 (0.34–1.26) | 0.20 | 0.71 (0.32–1.59) | 0.41 | 0.60 (0.27–1.33) | 0.21 | 1.20 (0.47–3.06) | 0.69 |

The probability of CRC is modelled in the first three columns; the probability of adenomas is modelled in the last column. All markers were log-transformed base 2

CRC colorectal cancer, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

Significant p values are marked in bold

Study 2

The characteristics of the patients in study 2 are shown in Table 2. A highly significant age difference (p < 0.0001) was found between CRC patients and individuals without neoplastic finding (i.e., without CRC or adenomas). The male percentage in the groups was significantly different (CRC versus individuals without neoplastic findings; p = 0.004, patients with adenomas versus individuals without neoplastic findings; p = 0.019).

Table 2.

Basic patient characteristics of study 2

| CRC (n = 99) | Adenoma (n = 196) | No neoplastic finding (n = 696) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 69 (62–79) | 65 (57–72) | 62 (52–72) |

| Male gender (%) | 58 | 54 | 42 |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 24 (22–28) | 25 (23–29) | 25 (22–28) |

| Current smokers (%) | 23 | 29 | 24 |

IQR interquartile range

Determination of CL-L1 was selected because in the first study it stood out for its discriminating power: It significantly discriminated several comparisons (CRC versus non-CRC, CRC versus healthy individuals and CRC versus patients with adenomas). MAp44 levels also significantly discriminated three out of four comparisons and could distinguish patients with adenomas from healthy individuals (Table 1). Other proteins had significant ORs (although not highly significant; Table 1), but due to logistics and economy, a maximum of three markers could be selected for validation in the much larger study 2, and M-ficolin was chosen as a third promising marker. Using Spearman rank correlations, we found that none of the chosen markers were highly correlated in study 2, although statistically significant (Table 3).

Table 3.

Spearman rank correlations between MAp44, CL-L1, M-ficolin and age (Spearman’s ρ:r, p value, number of observations)

| CL-L1 | M-ficolin | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAp44 | 0.23 | −0.06 | −0.16 |

| <0.0001 | 0.0601 | 0.0067 | |

| 991 | 991 | 299 | |

| CL-L1 | −0.001 | −0.25 | |

| 0.9630 | <0.0001 | ||

| 991 | 299 | ||

| M-ficolin | 0.18 | ||

| 0.0021 | |||

| 299 |

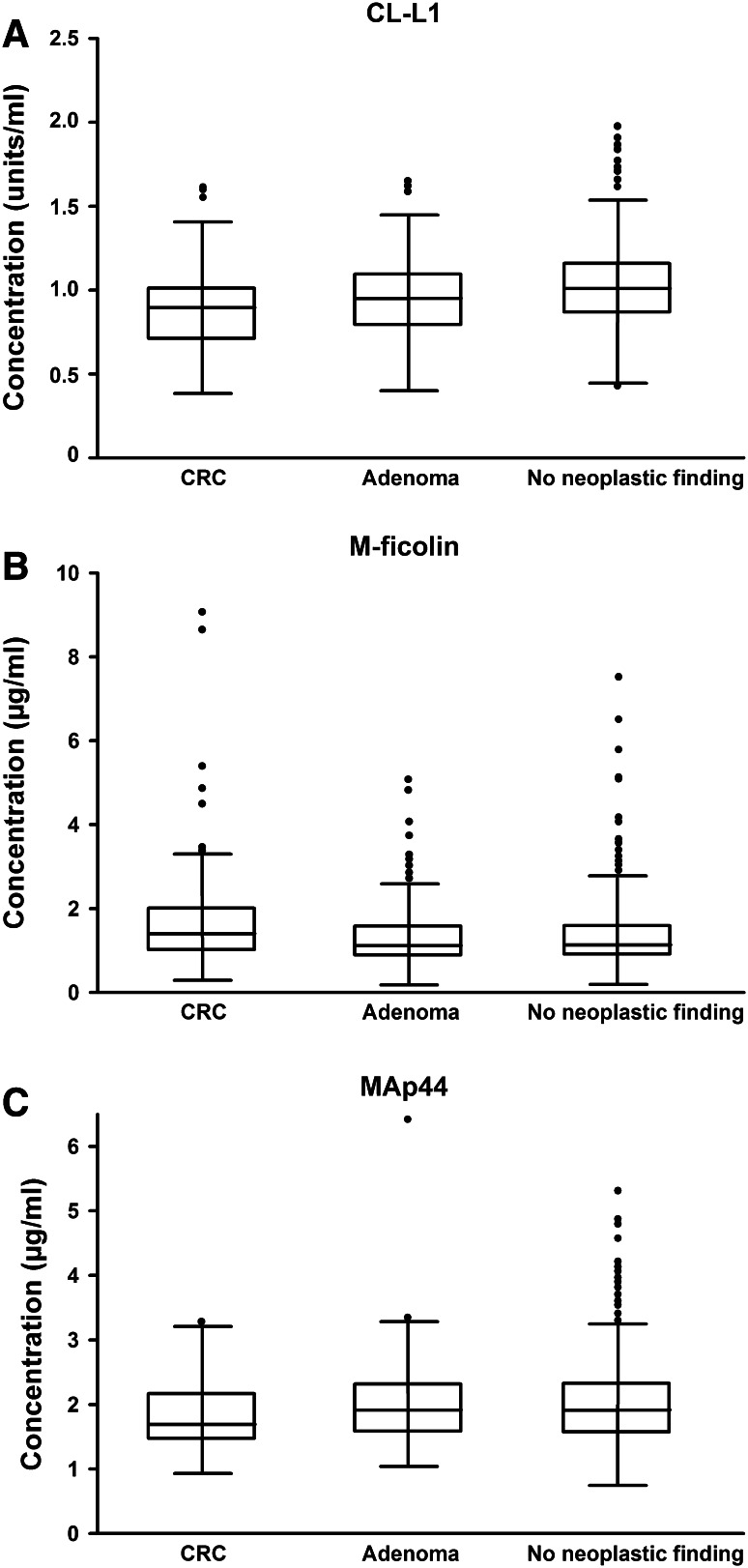

The distributions of CL-L1, M-ficolin and MAp44 in patients with CRC, patients with adenomas and individuals without neoplastic finding are shown in Fig. 2. The results of study 1 on CL-L1, M-ficolin and MAp44 concentrations were nearly all validated in study 2 (see below). Higher levels of CL-L1 or MAp44 were associated with lower odds of CRC compared to both non-CRC (OR 0.42 (0.25–0.70) p = 0.0009 and OR 0.39 (0.23–0.65) p = 0.0003, respectively) and individuals without neoplastic finding (OR 0.39 (0.23–0.65) p = 0.0003 and OR 0.39 (0.23–0.65) p = 0.0003, respectively) (Table 4). Furthermore, higher levels of CL-L1 were associated with lower odds of adenomas compared to no neoplastic finding (OR 0.61 (0.41–0.93) p = 0.022). However, when adjusting the analysis for age and sex, the CL-L1 level no longer significantly discriminated CRC patients from patients without CRC or patients with adenomas from individuals without neoplastic findings (Table 4). When plotting the data, there was no apparent association between CL-L1 level and age (data not shown). Despite this, the Spearman rank correlation was −0.25 (Table 3), implying a decrease in CL-L1 levels with age. This has not been examined previously. Although CL-L1 is no longer significant when included in a multivariate model with the two other markers and age and gender, the p value to include CL-L1 is 0.057, i.e., almost significant. Therefore, the difference is small, and removing CL-L1 from the model results in almost the same sensitivity and specificity.

Fig. 2.

The concentration of CL-L1 (a), M-ficolin (b) and MAp44 (c) in serum of individuals in study 2. Scatter plots of the concentrations divided into separate groups of CRC patients (n = 99), patients with adenomas (n = 196) and individuals without neoplastic findings (n = 696). Lines indicate mean and interquartile range (25th–75th percentiles). Boxes display interquartile range (25th–75th percentiles) and the median. The whiskers display the upper and lower values within 1.5 times the interquartile range. Outliers are shown

Table 4.

The univariate results of the logistic regression (log base 2) are shown by the OR with 95 % CI and AUC for the preselected proteins CL-L1, M-ficolin and MAp44

| Variable | CRC vs non-CRC | CRC versus no neoplastic finding | CRC versus adenoma | Adenoma vs no neoplastic finding | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95 % CI) | P AUC | OR (95 % CI) | P AUC | OR (95 % CI) | P AUC | OR (95 % CI) | P AUC | |

| CL-L1 | 0.42 (0.25–0.70) | 0.0009 | 0.39 (0.23–0.65) | 0.0003 | 0.58 (0.31–1.09) | 0.09 | 0.61 (0.41–0.93) | 0.022 |

| 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.57 | |||||

| Adjusteda | 0.59 (0.34–1.02) | 0.06 | 0.56 (0.32–0.97) | 0.04 | 0.74 (0.37–1.45) | 0.37 | 0.70 (0.45–1.07) | 0.10 |

| M-ficolin | 1.94 (1.46–2.59) | <0.0001 | 1.97 (1.47–2.65) | <0.0001 | 1.84 (1.30–2.60) | 0.0006 | 1.97 (1.47–2.65) | <0.0001 |

| 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.62 | |||||

| Adjusteda | 1.87 (1.38–2.53) | <0.0001 | 1.89 (1.38–2.58) | <0.0001 | 1.79 (1.25–2.57) | 0.0016 | 1.08 (0.85–1.36) | 0.55 |

| MAp44 | 0.39 (0.23–0.65) | 0.0003 | 0.39 (0.23–0.65) | 0.0003 | 0.42 (0.22–0.78) | 0.006 | 0.86 (0.58–1.26) | 0.43 |

| 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 0.51 | |||||

| Adjusteda | 0.56 (0.33–0.95) | 0.03 | 0.55 (0.32–0.94) | 0.03 | 0.61 (0.32–1.17) | 0.14 | 0.98 (0.66–1.45) | 0.90 |

Probability of CRC is modeled in the first three columns; and probability of adenomas is modeled in the last column

CRC colorectal cancer, OR Odds ratio, CI confidence interval, AUC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

Significant p values are marked in bold

aAdjusted for sex and age. Adjusting for BMI, tobacco and alcohol consumption made no difference

The MAp44 level was not able to distinguish patients with adenomas from individuals without neoplastic findings as was seen in study 1. The result was similar when excluding patients with comorbidities and patients with other findings in colon or rectum (data not shown). M-ficolin level could significantly distinguish all four comparisons. Indeed, higher levels of M-ficolin were associated with higher odds of CRC compared to both individuals without CRC (OR 1.94 (1.46–2.59) p < 0.0001), patients with adenomas (OR 1.84 (1.30–2.60) p = 0.0006) and patients without neoplastic finding (OR 1.97 (1.47–2.65) p < 0.0001). When we compare patients with adenomas to individuals without neoplastic finding, higher levels of M-ficolin were associated with higher odds of adenomas (OR 1.97 (1.47–2.65) p < 0.0001). After adjusting for age and sex, this association became insignificant (p = 0.55). Weak rank correlations between age and CL-L1, M-ficolin and MAp44, respectively, were shown. Although statistically significant, only a weak correlation between MAp44 and CL-L1 was found (Table 3). There were no significant correlations between disease stage and levels of CL-L1, MAp44 or M-ficolin in study 2 (data not shown).

The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) in Table 4 describes the ability of a marker to discriminate individuals with and without CRC. The univariate analysis of CRC patients and individuals without neoplastic findings resulted in AUCs of 0.61 (for MAp44) and 0.62 (for CL-L1 and M-ficolin). Combined in the multivariate analysis, AUC was 0.68. The combination of CL-L1, M-ficolin and MAp44 in a test of CRC versus non-CRC resulted in 36 % sensitivity at 83 % specificity (Table 5).

Table 5.

Sensitivity and specificity detecting CRC or adenoma when combining CL-L1, M-ficolin and MAp44 from study 2

| CRC versus non-CRC (%) | CRC versus no neoplastic finding (%) | CRC versus adenoma (%) | Adenoma versus no neoplastic finding (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity (if sensitivity level) | 49 (70) | 50 (82) | 35 (82) | 33 (79) |

| Sensitivity (if specificity level) | 36 (83) | 53 (80) | 38 (82) | 30 (79) |

Discussion

The interaction of cancer with the complement system and inflammation is complex, and inflammation can both be anti- and pro-tumorigenic. In the present study, we investigated if proteins of the lectin pathway of the complement system may be useful for identifying patients with CRC and premalignant lesions.

Study 1 identified CL-L1, M-ficolin and MAp44 as the most promising among the nine proteins analyzed, and study 2 validated that the levels of these three proteins differed significantly between CRC patients and patients with adenomas and individuals without neoplastic findings. Higher levels of CL-L1 and MAp44 were associated with lower odds of CRC, whereas higher levels of M-ficolin were associated with higher odds of CRC (Table 1 and 4). The difference in the levels of MAp44 between patients with adenomas and individuals without neoplastic finding in study 1 was not validated in study 2.

The differences in the biomarker concentration between the groups of patients with CRC, patients with adenomas and individuals without neoplastic findings were too small to be of value directly for identifying CRC patients. Thus, the AUCs were equal to or less than 0.62. Higher AUC values may possibly be reached by combining several independent markers. This was the case in the multivariate analyses of study 2 and suggested that the three markers were independently associated with CRC. Nevertheless, the sensitivity and specificity for detecting CRC versus no neoplastic findings using a combination of CL-L1, M-ficolin and MAp44 were low (Table 5) and would result in many false results if used for screening. Combined with other markers, one may possibly reach a useful discriminatory level. The value of data fusion has been demonstrated in several studies [34, 35]. As an example, the first blood-based biomarker for CRC detection, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) [26], is not useful for screening alone. However, when combined with the levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1), an AUC of 0.77 was reached [36].

The tendency we find for increased levels of M-ficolin and lower levels of MAp44 among CRC patients compared to individuals without neoplastic findings could suggest an activation of the complement system and subsequent inflammation. MAp44 can inhibit the lectin pathway by competition with the MASP [37, 38]; hence, lower levels of MAp44 might result in more inflammation. On the other hand, an increase in M-ficolin level may be an indicator of ongoing inflammation. It is produced by monocytes and neutrophils and is released upon stimulation [39]. Certainly, the higher levels of M-ficolin among CRC patients could have other explanations. M-ficolin could be stimulating malignant growth, the tumor could stimulate M-ficolin synthesis, or M-ficolin levels could increase due to an immune response to the CRC. However, we did not observe differences between preoperative and postoperative levels of M-ficolin or other of the lectin pathway proteins. If the synthesis of M-ficolin in CRC patients was tumor stimulated, one would expect the concentration to decrease after operation.

A strength of the present study was the stability of the proteins we measured. CL-L1 is stable at −20 and 4 °C and only starts to degrade when kept at room temperature or 37 °C (samples observed for 54 days) [11]. Concentrations of CL-L1, M-ficolin and MAp44 have been examined in sera collected until 25–40 days after CRC operation [11, 28, 30], and none of the proteins showed fluctuations compared to baseline concentration before operation. Regarding the measurement of CL-L1 levels, the recent finding of circulating complexes between CL-L1 and CL-K1 [12] may introduce a layer of uncertainty. Quantification of CL-L1 might be influenced by such complex formation by the nature of the CL-L1/CL-K1 complex, and we do not know whether there is an inter-individual variation in the composition of such complexes. Study 2 was a multicenter setting with patient inclusion distributed across the country, and the researchers were blinded to sample identity.

Importantly, the case–control studies were carried out among individuals with symptoms of CRC. Other studies examining possible biomarkers for CRC have used blood donors as healthy controls. This approach introduces a risk of selection bias as the blood donors are not necessarily representative of a CRC-related background population. Blood donors are significantly younger (median age 47 (IQR 39–55)); they present a lower proportion of males (62 %) and differ in background and milieu from the patients. The individuals with CRC symptoms often have concurrent diseases, which the biomarkers must be able to distinguish from CRC [40]. Further, one cannot know whether some of the blood donors have an undiagnosed CRC. In the current study, all serum samples were collected prior to colonoscopy for suspected CRC but late in the cancer progress when the patients had developed symptoms.

M-ficolin is a pattern recognition molecule, and the plasma level increases by inflammatory stimuli, as noted above. The increased levels of M-ficolin among CRC patients could hypothetically predispose to CRC. Higher levels of M-ficolin might stimulate tumor growth via increased activation of the complement system and thus generation of complement factor C5a, which has been shown to enhance tumor growth in a mouse model of cervical cancer [14]. The migration of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) into the tumor is C5a-receptor dependent. MDSCs inhibit the cytotoxic T cell response to the tumor cells and thus create an immunosuppressed microenvironment around the tumor [8]. CL-L1, M-ficolin and MAp44 are quite recently described proteins, and their biological role or roles are unknown. The association between the biomarkers and CRC could also be a result of an underlying common mechanism. To elucidate the mechanism responsible for our findings, further research is necessary.

In conclusion, CL-L1, M-ficolin and MAp44 were identified as biological markers that vary significantly between CRC patients and patients with adenomas and individuals without neoplastic findings in the bowel. However, when adjusting for age and sex, only MAp44 and M-ficolin remained significant. The discriminatory value of the protein levels, as judged by AUC, sensitivity and specificity, was insufficient with regard to use as screening markers. However, analyses for the proteins may improve the value of existing or future screening assays.

Acknowledgments

Line Storm was funded by Danish Council for Independent Research, Medical Sciences. The Research Nurses, Technicians and Secretaries at the participating hospitals are thanked for the skillful work with recruiting patients, collecting and handling blood samples and recording data. The clinical part of the study was sponsored by grants from The Kornerup Fund, The Aase and Ejnar Danielsen Fund, The Aage and Johanne Louis-Hansen Fund, The Kathrine and Vigo Skovgaard Fund, The Vissing Fond, The Henrik Henriksen Fund, The Obel Foundation, The Hede-Nielsen Family Fund, The Midtjyske Bladfond, The Jochum Foundation, The Bjarne Jensen Fund, The Inger Bonnén Fund, The Arvid Nilsson Fund, The Erna Hamilton Fund, The Dagmar Marshall Fund, The Oda and Hans Svenningsen Fund, The Walter and O. Kristiane Christensen Fund, The Knud Højgaard Fund, The Spar Nord Fund, The Axel Muusfeldt Fund, The Einar Willumsen Fund, The Frimodt-Heineke Fund, The H.C. Bechgaard Fund, The KID Fund, The Leif Rasmussen Fund, The Sophus and Astrid Jacobsen Fund, The Thora and Viggo Grove Fund, The Torben and Alice Frimodt Fund and Hvidovre Hospital.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- CL-L1

Collectin-liver 1

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- MAp44

MBL-associated protein 44

- MASP

MBL-associated serine protease

- MBL

Mannan-binding lectin

Appendix

The co-authors of the Danish Study Group on Early Detection of Colorectal Cancer include:

Lars Nannestad Jørgensen, Department of Surgical Gastroenterology, Bispebjerg Hospital

Mogens Rørbæk-Madsen, Department of Surgery, Herning Hospital

Jesper Vilandt, Department of Surgery, Hilleroed Hospital

Thore Hillig, Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Hilleroed Hospital

Michael Klaerke, Department of Surgery, Horsens Hospital

Knud T. Nielsen, Department of Surgery, Randers Hospital

Søren Laurberg, Department of Surgical Gastroenterology, Aarhus Hospital

Nils Brünner, Institute of Veterinary Pathobiology, University of Copenhagen

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iversen LH, Pedersen L, Riis A, Friis S, Laurberg S, Sorensen HT. Population-based study of short- and long-term survival from colorectal cancer in Denmark, 1977–1999. Br J Surg. 2005;92(7):873–880. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garborg K, Holme O, Loberg M, Kalager M, Adami HO, Bretthauer M. Current status of screening for colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(8):1963–1972. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pio R, Ajona D, Lambris JD. Complement inhibition in cancer therapy. Semin Immunol. 2013;25(1):54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140(6):883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trinchieri G. Cancer and inflammation: an old intuition with rapidly evolving new concepts. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:677–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ricklin D, Hajishengallis G, Yang K, Lambris JD. Complement: a key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(9):785–797. doi: 10.1038/ni.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Degn SE, Thiel S. Humoral pattern recognition and the complement system. Scand J Immunol. 2013;78(2):181–193. doi: 10.1111/sji.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen S, Selman L, Palaniyar N, Ziegler K, Brandt J, Kliem A, Jonasson M, Skjoedt MO, Nielsen O, Hartshorn K, Jorgensen TJ, Skjodt K, Holmskov U. Collectin 11 (CL-11, CL-K1) is a MASP-1/3-associated plasma collectin with microbial-binding activity. J Immunol. 2010;185(10):6096–6104. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Axelgaard E, Jensen L, Dyrlund TF, Nielsen HJ, Enghild JJ, Thiel S, Jensenius JC. Investigations on collectin liver 1. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(32):23407–23420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.492603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henriksen ML, Brandt J, Andrieu JP, Nielsen C, Jensen PH, Holmskov U, Jorgensen TJ, Palarasah Y, Thielens NM, Hansen S. Heteromeric complexes of native collectin kidney 1 and collectin liver 1 are found in the circulation with MASPs and activate the complement system. J Immunol. 2013;191(12):6117–6127. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finn OJ (2012) Immuno-oncology: understanding the function and dysfunction of the immune system in cancer. Ann Oncol 23 Suppl 8:viii6-9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Markiewski MM, DeAngelis RA, Benencia F, Ricklin-Lichtsteiner SK, Koutoulaki A, Gerard C, Coukos G, Lambris JD. Modulation of the antitumor immune response by complement. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(11):1225–1235. doi: 10.1038/ni.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ytting H, Jensenius JC, Christensen IJ, Thiel S, Nielsen HJ. Increased activity of the mannan-binding lectin complement activation pathway in patients with colorectal cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39(7):674–679. doi: 10.1080/00365520410005603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ytting H, Christensen IJ, Thiel S, Jensenius JC, Nielsen HJ. Serum mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease 2 levels in colorectal cancer: relation to recurrence and mortality. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(4):1441–1446. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisch U, Zehnder A, Hirt A, Niggli F, Simon A, Ozsahin H, Schlapbach L, Ammann R. Mannan-binding lectin (MBL) and MBL-associated serine protease-2 in children with cancer. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141:w13191. doi: 10.4414/smw.2011.13191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zehnder A, Fisch U, Hirt A, Niggli FK, Simon A, Ozsahin H, Schlapbach LJ, Ammann RA. Prognosis in pediatric hematologic malignancies is associated with serum concentration of mannose-binding lectin-associated serine protease-2 (MASP-2) Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53(1):53–57. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andersen JD, Boylan KL, Xue FS, Anderson LB, Witthuhn BA, Markowski TW, Higgins L, Skubitz AP. Identification of candidate biomarkers in ovarian cancer serum by depletion of highly abundant proteins and differential in-gel electrophoresis. Electrophoresis. 2010;31(4):599–610. doi: 10.1002/elps.200900441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo JH, Ren B, Keryanov S, Tseng GC, Rao UN, Monga SP, Strom S, Demetris AJ, Nalesnik M, Yu YP, Ranganathan S, Michalopoulos GK. Transcriptomic and genomic analysis of human hepatocellular carcinomas and hepatoblastomas. Hepatology. 2006;44(4):1012–1024. doi: 10.1002/hep.21328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi I, Hashemi Sadraei N, Duan ZH, Shi T. Aberrant signaling pathways in squamous cell lung carcinoma. Cancer Inf. 2011;10:273–285. doi: 10.4137/CIN.S8283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlapbach LJ, Aebi C, Hansen AG, Hirt A, Jensenius JC, Ammann RA. H-ficolin serum concentration and susceptibility to fever and neutropenia in paediatric cancer patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;157(1):83–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03957.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szala A, Sawicki S, Swierzko AS, Szemraj J, Sniadecki M, Michalski M, Kaluzynski A, Lukasiewicz J, Maciejewska A, Wydra D, Kilpatrick DC, Matsushita M, Cedzynski M. Ficolin-2 and ficolin-3 in women with malignant and benign ovarian tumours. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62(8):1411–1419. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1445-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schlapbach LJ, Thiel S, Aebi C, Hirt A, Leibundgut K, Jensenius JC, Ammann RA. M-ficolin in children with cancer. Immunobiology. 2011;216(5):633–638. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nielsen HJ, Jess P, Aldulaymi BH, Jorgensen LN, Laurberg S, Nielsen KT, Madsen MR, Brunner N, Christensen IJ. Early detection of recurrence after curative resection for colorectal cancer: obstacles when using soluble biomarkers? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48(3):326–333. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.758774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nielsen HJ, Brunner N, Frederiksen C, Lomholt AF, King D, Jorgensen LN, Olsen J, Rahr HB, Thygesen K, Hoyer U, Laurberg S, Christensen IJ, Danish-Australian Endoscopy Study Group On Colorectal Cancer D, Danish Colorectal Cancer Cooperative G (2008) Plasma tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1): a novel biological marker in the detection of primary colorectal cancer. Protocol outlines of the Danish-Australian endoscopy study group on colorectal cancer detection. Scand J Gastroenterol 43 (2):242–248. doi: 10.1080/00365520701523439 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Krarup A, Sorensen UB, Matsushita M, Jensenius JC, Thiel S. Effect of capsulation of opportunistic pathogenic bacteria on binding of the pattern recognition molecules mannan-binding lectin, L-ficolin, and H-ficolin. Infect Immun. 2005;73(2):1052–1060. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.1052-1060.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wittenborn T, Thiel S, Jensen L, Nielsen HJ, Jensenius JC. Characteristics and biological variations of M-ficolin, a pattern recognition molecule, in plasma. J Innate Immun. 2010;2(2):167–180. doi: 10.1159/000218324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Degn SE, Thiel S, Nielsen O, Hansen AG, Steffensen R, Jensenius JC. MAp19, the alternative splice product of the MASP2 gene. J Immunol Methods. 2011;373(1–2):89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Degn SE, Jensen L, Gal P, Dobo J, Holmvad SH, Jensenius JC, Thiel S. Biological variations of MASP-3 and MAp44, two splice products of the MASP1 gene involved in regulation of the complement system. J Immunol Methods. 2010;361(1–2):37–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thiel S, Jensen L, Degn SE, Nielsen HJ, Gal P, Dobo J, Jensenius JC. Mannan-binding lectin (MBL)-associated serine protease-1 (MASP-1), a serine protease associated with humoral pattern-recognition molecules: normal and acute-phase levels in serum and stoichiometry of lectin pathway components. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;169(1):38–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2012.04584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moller-Kristensen M, Jensenius JC, Jensen L, Thielens N, Rossi V, Arlaud G, Thiel S. Levels of mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease-2 in healthy individuals. J Immunol Methods. 2003;282(1–2):159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thiel S, Moller-Kristensen M, Jensen L, Jensenius JC. Assays for the functional activity of the mannan-binding lectin pathway of complement activation. Immunobiology. 2002;205(4–5):446–454. doi: 10.1078/0171-2985-00145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bro R, Nielsen HJ, Savorani F, Kjeldahl K, Christensen IJ, Brunner N, Lawaetz AJ. Data fusion in metabolomic cancer diagnostics. Metabolomics. 2013;9(1):3–8. doi: 10.1007/s11306-012-0446-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thorsen SB, Lundberg M, Villablanca A, Christensen SL, Belling KC, Nielsen BS, Knowles M, Gee N, Nielsen HJ, Brunner N, Christensen IJ, Fredriksson S, Stenvang J, Assarsson E. Detection of serological biomarkers by proximity extension assay for detection of colorectal neoplasias in symptomatic individuals. J Transl Med. 2013;11:253. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nielsen HJ, Brunner N, Jorgensen LN, Olsen J, Rahr HB, Thygesen K, Hoyer U, Laurberg S, Stieber P, Blankenstein MA, Davis G, Dowell BL, Christensen IJ, Danish Endoscopy Study Group on Colorectal Cancer D, Danish Colorectal Cancer Cooperative G (2011) Plasma TIMP-1 and CEA in detection of primary colorectal cancer: a prospective, population based study of 4509 high-risk individuals. Scand J Gastroenterol 46 (1):60–69. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.513060 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Degn SE, Hansen AG, Steffensen R, Jacobsen C, Jensenius JC, Thiel S. MAp44, a human protein associated with pattern recognition molecules of the complement system and regulating the lectin pathway of complement activation. J Immunol. 2009;183(11):7371–7378. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skjoedt MO, Roversi P, Hummelshoj T, Palarasah Y, Rosbjerg A, Johnson S, Lea SM, Garred P. Crystal structure and functional characterization of the complement regulator mannose-binding lectin (MBL)/ficolin-associated protein-1 (MAP-1) J Biol Chem. 2012;287(39):32913–32921. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.386680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kjaer TR, Thiel S, Andersen GR. Toward a structure-based comprehension of the lectin pathway of complement. Mol Immunol. 2013;56(4):413–422. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nielsen HJ, Jakobsen KV, Christensen IJ, Brunner N, Danish Study Group on Early Detection of Colorectal C (2011) Screening for colorectal cancer: possible improvements by risk assessment evaluation? Scand J Gastroenterol 46 (11):1283–1294. doi:10.3109/00365521.2011.610002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]