Abstract

Background

Usual type vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (uVIN) is caused by HPV, predominantly type 16. Several forms of HPV immunotherapy have been studied, however, clinical results could be improved. A novel intradermal administration route, termed DNA tattooing, is superior in animal models, and was tested for the first time in humans with a HPV16 E7 DNA vaccine (TTFC-E7SH).

Methods

The trial was designed to test safety, immunogenicity, and clinical response of TTFC-E7SH in twelve HPV16+ uVIN patients. Patients received six vaccinations via DNA tattooing. The first six patients received 0.2 mg TTFC-E7SH and the next six 2 mg TTFC-E7SH. Vaccine-specific T-cell immunity was evaluated by IFNγ-ELISPOT and multiparametric flow cytometry.

Results

Only grade I-II adverse events were observed upon TTFC-E7SH vaccination. The ELISPOT analysis showed in 4/12 patients a response to the peptide pool containing shuffled E7 peptides. Multiparametric flow cytometry showed low CD4+ and/or CD8+ T-cell responses as measured by increased expression of PD-1 (4/12 in both), CTLA-4 (2/12 and 3/12), CD107a (5/12 and 4/12), or the production of IFNγ (2/12 and 1/12), IL-2 (3/12 and 4/12), TNFα (2/12 and 1/12), and MIP1β (3/12 and 6/12). At 3 months follow-up, no clinical response was observed in any of the twelve vaccinated patients.

Conclusion

DNA tattoo vaccination was shown to be safe. A low vaccine-induced immune response and no clinical response were observed in uVIN patients after TTFC-E7SH DNA tattoo vaccination. Therefore, a new phase I/II trial with an improved DNA vaccine format is currently in development for patients with uVIN.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-017-2006-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: VIN, HPV, Immunotherapy, DNA vaccine, Immunogenicity, Safety

Introduction

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is a premalignant chronic skin disorder of the vulva epithelium. VIN lesions were reclassified in 2004 by the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease as usual type VIN (uVIN), formerly called VIN2 and VIN3, and differentiated VIN (dVIN) [1]. uVIN is caused by a persistent infection of high-risk types of HPV, in particular by HPV type 16, which is present in approximately 70% of the patients [2–6]. Known risk factors are smoking, a history of genital herpes, condylomata, and an immunocompromised state [7, 8]. Spontaneous regression of uVIN lesions occurs in less than 1–2%, and vulvar cancer develops in 3–9% of patients with uVIN [9, 10]. Unfortunately, current treatment strategies (i.e., primary surgery, laser therapy, and topical salve treatment) have high relapse rates; therefore, there is an unmet need for novel therapeutic strategies to improve the treatment and prognosis of patients with uVIN [11–13].

Several HPV-vaccine approaches have been studied in both animal models and humans, and have resulted in different vaccine platforms with encouraging clinical responses in premalignant lesions. A phase II clinical trial of the topical immunomodulator, imiquimod, followed by three doses of a therapeutic HPV vaccination (TA-CIN, fusion protein HPV16 E6E7L2) showed an uVIN lesion response in 63% of patients [14]. A synthetic long peptide (SLP) vaccination study showed in 45% of women with uVIN clinical responses and in all patients’ vaccine-induced HPV16-specific T-cell responses [15–17]. In a randomized controlled trial, patients with VIN or vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VaIN) were vaccinated with a SLP (ISA101) with or without application of imiquimod at the vaccine site. Imiquimod did not improve the outcomes of vaccination; however, vaccine-induced clinical responses were observed in 52% of the patients [16]. Recently, VGX-3100, a therapeutic synthetic DNA vaccine encoding HPV16 and 18 E6 and E7, showed 48% histological regression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2/3, with only 30% of histological regression in the placebo group [18].

Although these clinical outcomes are encouraging, there is room for improvement to reach benefit for all vaccinated patients. Also the adjuvant MONTANIDE ISA51 used in the SLP vaccine resulted in adverse side effects in almost all patients, which can be overcome by administration of a vaccine via a different route [15, 16]. Therefore, the biggest opportunity lies in the optimization of the route of administration and improving the immunogenicity of the vaccine [19]. We have developed a novel administration strategy, in which DNA is delivered via a tattoo, using a permanent make-up device (MT. Derm GmbH, Berlin, Germany). This strategy was shown to lead to a more rapid induction of cellular immunity as compared to conventional application methods of DNA vaccination in mice [20]. Furthermore, DNA tattooing outperforms classical intramuscular DNA vaccination by 10- to 100-fold when tested in non-human primates [21] and was optimized in an ex vivo human skin model [22].

Next to this novel administration strategy, we have successfully developed an HPV16-directed DNA vaccine named TTFC-E7SH (encoding the fusion protein of Tetanus Toxin Fragment C and a shuffled variant of HPV16 E7) with good immunogenicity and safety profiles, by combining strategies to “detoxify” and improve DNA vaccine-encoded antigens [23]. Safety of the shuffled DNA vaccine format has also been established in in vitro transformation assays using human keratinocytes [24]. Furthermore, when evaluated in a head-to-head comparison in mice, TTFC-E7SH strongly outperformed a DNA vaccine encoding a fusion of E7 and mycobacterial heat shock protein that was tested in humans and resulted in promising therapeutic responses [18, 25].

In the present study, we conducted a phase I clinical trial to evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of the TTFC-E7SH vaccine, applied via DNA tattooing, for the treatment of patients with HPV16-positive uVIN lesions.

Patients and methods

Patients

Twelve patients with histologically proven HPV16-positive uVIN were eligible for the study (see Table 1 for patient baseline characteristics). Additional criteria for eligibility include no indication of an active infectious disease (HIV, Hepatitis B, and Hepatitis C negative), no history of auto-immune disease, normal pretreatment laboratory blood values (White blood cell count (WBC) >3.0/nL, platelets >100/nL), renal function (creatinine clearance >40 mL/min), and liver function (bilirubin <1.5 × Upper limit of normal (ULN), normal blood coagulation), no prior treatment with anti-HPV agents, no use of immunosuppressive drugs, and no treatment for uVIN lesions within 6 weeks prior to enrollment.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all 12 patients

| Patient no. | Age at diagnosis | Type of neoplasia | Symptoms | Smoking status | Cohort |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 62 | Multifocal | Mild | Smoker | 1 |

| 2 | 39 | Multifocal | Severe | Smoker | 1 |

| 3 | 55 | Unifocal | Mild | Former smoker | 1 |

| 4 | 45 | Multifocal | None | Smoker | 1 |

| 5 | 41 | Multifocal | None | Former smoker | 1 |

| 6 | 55 | Unifocal | None | Former smoker | 1 |

| 7 | 50 | Unifocal | None | Smoker | 2 |

| 8 | 47 | Multifocal | Mild | Smoker | 2 |

| 9 | 63 | Multifocal | Mild | Smoker | 2 |

| 10 | 58 | Unifocal | Mild | Smoker | 2 |

| 11 | 46 | Unifocal | None | Former smoker | 2 |

| 12 | 50 | Unifocal | None | Smoker | 2 |

The study was approved by the Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subject (In Dutch: Centrale Commissie Mensgebonden Onderzoek; CCMO) in The Hague, the Netherlands (Number NL46637.000.13) and registered at trialregister.nl (NTR4607). All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Composition of the vaccine

We constructed TTFC-E7SH, which is a minimal E.coli-derived plasmid backbone (pVAX1) containing a pUC Ori Origin of Replication, a Kanamycin resistance gene, and CMV early promoter that drives the gene of interest encoding the fusion protein of domain 1 of Tetanus toxin fragment C (TTFC) and the shuffled version of the HPV16 E7 oncoprotein. For the manufacture of TTFC-E7SH, a standard Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) production process was followed as described earlier [26–28]. TTFC-E7SH was formulated as a lyophilized powder. The final product contained 2 mg pDNA and 40 mg sucrose as cryoprotector and was dissolved in water for injection to 5 mg/ml pDNA before intradermal injection.

The phase I trial

An open-label, single-center phase I study was designed to determine the safety, immunological activity, and the clinical response of TTFC-E7SH. Twelve patients were vaccinated with a fixed dose of TTFC-E7SH on days 0, 3, and 6 and received a boost vaccination scheduled at week 4 (days 28, 31, and 34). The TTFC-E7SH was administered using a novel intradermal application strategy using a permanent make-up device (MT. Derm GmbH, Berlin, Germany). This DNA tattooing technique was previously optimized in ex vivo human skin models [22].

Prior to vaccination, the targeted skin area was treated with VEET® hair removal cream for sensitive skin, to remove skin hair non-traumatically. The TTFC-E7SH was injected over the skin surface area of the lower limbs, close to the inguinal lymph nodes.

Patients were assigned to a cohort in order of study entry. In cohort 1 (n = 6), the dose level was 0.2 mg injected over a skin surface of 2 cm2 in 1 min. In cohort 2 (n = 6), the dose level was 2 mg injected over a skin surface of 16 cm2 in 10 min. In both cohorts, the needle depth was 1.0–1.5 mm. The decision to start enrollment at dose level 2 was made by assessing the safety after all the patients received all six vaccinations in dose level 1.

If no toxicity occurred during priming vaccination, the patient continued the treatment with the boost vaccination. In case of toxicity during the priming vaccination, then once these toxicities had resolved to ≤grade 1 or baseline value, the patient received the subsequent booster treatment. If a patient required a delay in the vaccination scheme greater than 21 days from the intended day of the booster vaccination, the patient was discontinued from the study.

Safety and tolerability

Safety assessments included evaluation of adverse events, regular monitoring of laboratory parameters (basic chemistry and hematology), and physical examination, including vital signs up to 3 months after the last vaccination. Adverse events were graded according to version 4.03 of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), which grades events on a scale of 1 to 5, with higher grades indicating greater severity. All patients who received at least one vaccination with TTFC-E7SH were included in the safety analyses.

Assessment of clinical responses

Evaluation variables of clinical responses were symptoms, lesion size, and histologic features. All lesions were monitored by digital photography and were described in detail. A complete response is defined as a complete disappearance of the lesion. A partial response is defined as a disappearance of at least 50% of the total lesion area. No response is defined as a disappearance of less than 50% of the total lesion.

Immune monitoring

In order to study the HPV16-specific T-cell immunity, peripheral blood samples were taken prior to DNA vaccination and at different time points thereafter (days 14, 28, 42, and 56). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from fresh heparinized blood samples by Ficoll density-gradient centrifugation and cryopreserved until further experiments.

For studying the HPV16-specific T-cell responses, the cryopreserved PBMCs were subjected to two complementary assays. The validated 4-day IFNγ-ELISPOT and multiparametric flow cytometry were performed according to standard operating procedure protocols with predefined criteria for positive- and vaccine-induced responses.

For intracellular cytokine and surface staining by multiparametric flow cytometry, PBMCs were thawed and were stimulated with three in-house generated, different peptide pools; pool 1 consisting of non-shuffled HPV16 E7 peptides and 4 shuffled peptides, and pool 2 and 3 consisting of overlapping TTFC peptides covering the vaccine construct. For an overview of the peptide pools see Supplementary Table 1. The shuffled epitopes in pool 1 are considered clinically irrelevant, as they will not be expressed in the patient’s HPV-infected cells. However, responses against these epitopes should not exist at baseline and can therefore be regarded as truly vaccine-enhanced HPV-specific T-cell responses. These overlapping peptides were loaded on autologous monocytes to ensure proper processing and presentation of the epitopes. In addition to the HPV antigens, as a positive control, viral recall antigens consisting of a pool of peptides of Influenza A virus (Flu), Cytomegalovirus (CMV), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) epitopes were included to assess immune competence of the patients.

Subsequently, surface staining (for CD3, CD4, CD8, CD14, CD16, CD19, PD-1, and CD107a), intracellular staining (for IFNγ, IL-2, TNFα, MIP1β and CTLA-4), and acquisition of the cells were performed using LSR II (BD Biosciences). Analysis was done using Kaluza software (Beckman coulter). Immunological responses, measured by intracellular cytokine production and/or the expression of co-inhibitory molecules, were considered positive when the percentage of peptide stimulated T cells was at least twice the percentage detected in the baseline samples (time point 0), and if the responding cells were visible as a clearly distinguishable population in the analysis dot plot. A vaccine-induced response was defined as a 2-fold increase in the T-cell response compared to baseline. Percentages were noted as percentage of HPV-stimulated condition minus percentage of unstimulated condition.

For the validated IFNγ-ELISPOT, PBMCs prior to-, during-, and post vaccination were thawed at the same time. PBMCs were stimulated with three different HPV pools, E7.1 peptide pool (HPV16 E7 amino acid 1–22; 11–32; 21–42; 31–52), E7.2 (HPV16 E7 amino acid 41–62; 51–72; 61–82; 71–92; 77–98), and the pool of E7 peptides that also include the shuffled E7 peptides (pool 1, see Supplementary Table 1) for 4 days as described previously [16]. Memory Response Mix (MRM) containing tetanus toxoid, Mycobacterium tuberculosis sonicate, and Candida albicans peptides, was used as a positive control, while the cells cultured for 4 days in medium only were used as a negative control. IFNγ-positive spots were counted with a fully automated computer-assisted-video-imaging analysis system (BioSys 5000). Specific spots per 100,000 PBMCs were calculated by subtracting the mean number of spots plus two times the standard deviation of the medium-only control from the mean number of spots in experimental wells. Positive responses were defined as 10 or more specific spots per 100,000 PBMCs. A vaccine-induced response was defined as at least a 3-fold increase in the response after vaccination when compared to the baseline sample [15, 16].

Statistical analysis

No power calculation was performed, since this was a phase I study. For both IFNγ-ELISPOT and multiparametric flow cytometry, a positive response was predefined and described above. Statistical analysis was conducted in SPSS (version 22 for Windows; SPSS, Inc). The Mann–Whitney test and the Fisher’s exact test were used to evaluate the differences in patient characteristics.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between May 2014 and January 2015, seventeen patients were screened for the trial at the Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (AvL) hospital, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Three patients withdrew, and the uVIN lesions from two patients were not HPV16-positive. The remaining twelve patients with histologically confirmed HPV16-positive uVIN were included in this study. All twelve patients received all six vaccinations. The median age was 50.0 years (range 39–63 years). The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1, no clinical–pathological differences between the two cohorts were observed (not shown).

Safety and tolerability

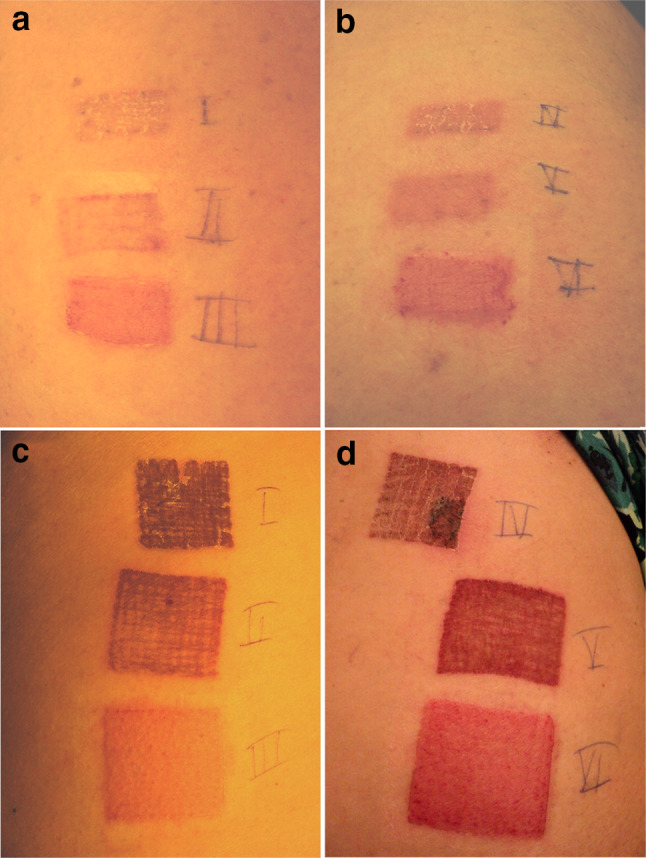

Administration of TTFC-E7SH via DNA tattooing was well tolerated by all patients. In Fig. 1, representative vaccination spots are shown, for both cohorts 1 and 2. All related adverse events, stratified by cohort, are depicted in Table 2. No related serious adverse events were reported, except mild toxicity grade 1–2 according to CTCAE version 4.03. The most common adverse events were injection site reactions, which occurred in 16.7% of patients in cohort 1 and in 100% in cohort 2. All injection site reactions were resolved during three months follow-up. Other common adverse events included fatigue (33.3% in both cohorts) and headache (66.7 and 33.3% in cohort 1 and 2, respectively). There was no difference in tolerability in the two cohorts. In Supplementary Table 2, the adverse events per patient are shown. Hematological values assessed in the blood drawn before, during, and after vaccination did not show significant changes (not shown).

Fig. 1.

Vaccination spots in both dose cohorts. a, b Vaccination spots of patient #3 in cohort 1, dose 0.2 mg in 2 cm2. c, d Vaccination spots of patient #12 in cohort 2, dose 2 mg in 16 cm2

Table 2.

Local and systemic adverse events in 12 patients

| Event | CTCAE grade | Related | TTFC-E7SH 0.2 mg (n = 6) | TTFC-E7SH 2 mg (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local | ||||

| Injection site reaction | 1 | Definitely | 1 (16.7%) | 6 (100%) |

| Pruritus (vaccination site) | 1 | Probable | 1 (16.7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Systemic | ||||

| Diarrhea | 1 | Possible | 0 (0%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Dyspnea | 1 | Possible | 0 (0%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Fatigue | 1/2 | Possible | 2 (33.3%) | 2 (33.3%) |

| Fever | 1 | Possible | 0 (0%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Flu-like symptoms | 1 | Possible | 2 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Headache | 1/2 | Possible | 4 (66.7%) | 2 (33.3%) |

| Malaise | 1 | Possible | 0 (0%) | 2 (33.3%) |

| Myalgia | 1 | Probable | 2 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Pruritus (vulva/anus) | 1 | Probable | 3 (50%) | 0 (0%) |

| Vaginal pain | 1 | Probable | 0 (0%) | 2 (33.3%) |

Data are shown as number of patients (and percentages); CTCAE grade version 4.03, common terminology criteria for adverse events

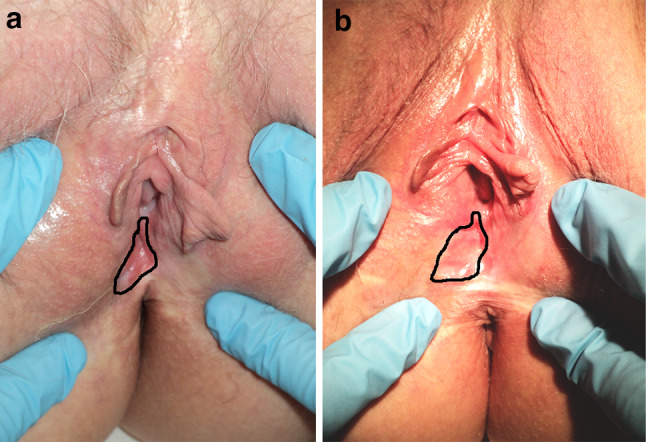

Clinical response

The uVIN lesions were identified, measured, and photographed before and 3 months after vaccination. Furthermore, prior to and 3 months after the vaccinations, biopsies of the VIN lesion were taken. At three months follow-up, no clinical or histological response was observed, which is exemplified in Fig. 2 for patient #3.

Fig. 2.

No clinical response to vaccination in a patient with uVIN. a Shows a typical lesion in patient #10 before the start of treatment, and b shows no regression of the lesion 3 months after 6 vaccinations with TTFC-E7SH

In the study protocol, only three months follow-up was disclosed, but all patients were followed according to standard clinical practice. One year after the last vaccination, three patients underwent a local excision of the VIN lesion of which in two patients micro-invasive vulvar cancer was detected. Five patients underwent laser therapy, one patient was treated with imiquimod, and three patients stayed in the standard care follow-up without any treatment.

Immunological responses

Blood samples were taken prior to vaccination (T1 = week 0), after the first three vaccinations (T2 = week 2), prior to the boost vaccinations (T3 = week 4) and two times after the last vaccination (T4 = week 6 and T5 = week 8).

In order to investigate the effect of the vaccination with TTFC-E7SH on the activation status of T cells in the blood samples, we studied changes in cytokine production (IFNγ, IL-2, TNFα, MIP1β), the expression of degranulation marker CD107a, co-inhibitory molecules PD-1 and CTLA-4 after stimulation with 22-mers overlapping peptide pools 1 to 3. Gating strategies are shown in Supplementary Figure 1. Figures 3 and 4 show the immunological effect on all patients after stimulation with peptide pool 1. We found low responses and minor fluctuations in percentages of stimulated T cells positive for co-inhibitory molecules (less than 2% of T cells) and intracellular cytokines (less than 4% of T cells). The co-inhibitory molecule PD-1 on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was increased in 4/12 patients. CTLA-4 was increased in 2/12 and 3/12 patients in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, respectively. Interestingly, for both PD-1 and CTLA-4, these responses were observed at week 2, 4, and 6, but were no longer present at week 8. We also observed an increase in expression of CD107a for CD4+ T cells (5/12) and CD8+ T cells (4/12). Furthermore, we observed, only in patients in cohort 1, an increase in IFNγ producing CD4+ (2/12 patient) and CD8+ (1/12 patients) T cells. The frequency of IL-2 producing CD4+ T cells increased in 3 out of 12 patients, and for the CD8+ T cells this increase was observed in 4 patients. For TNFα, an increase was observed in 2/12 and 1/12 patients for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, respectively. Furthermore MIP1β increased in 3 out of 12 patients and in 6 out of 12 patients in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Phenotypical changes of CD4+ T cells upon treatment after stimulation of peptide pool 1 (HPV16 E7 shuffled and unshuffled peptides). The immune cell composition was measured by flow cytometry at baseline (week 0), after the first 3 vaccinations (week 2), before the boost vaccinations (week 4), and after treatment (week 6 and 8). Depicted are the following subsets: a % PD-1+ cells within CD4+ T cells (cohort 1 upper panel, cohort 2 lower panel). b % CTLA-4+ cells within CD4+ T cells (cohort 1 upper panel, cohort 2 lower panel). c % IFNγ+ cells within CD4+ T cells (cohort 1 upper panel, cohort 2 lower panel). d % IL-2+ cells within CD4+ T cells (cohort 1 upper panel, cohort 2 lower panel). e % TNFα+ cells within CD4+ T cells (cohort 1 upper panel, cohort 2 lower panel). f % CD107a+ cells within CD4+ T cells (cohort 1 upper panel, cohort 2 lower panel). g % MIP1β+ cells within CD4+ T cells (cohort 1 upper panel, cohort 2 lower panel). *Depicts the true responses

Fig. 4.

Phenotypical changes of CD8+ T cells upon treatment after stimulation of peptide pool 1 (HPV16 E7 shuffled and unshuffled peptides). The immune cell composition was measured by flow cytometry at baseline (week 0), after the first 3 vaccinations (week 2), before the boost vaccinations (week 4), and after treatment (week 6 and 8). Depicted are the following subsets: a % PD-1+ cells within CD8+ T cells (cohort 1 upper panel, cohort 2 lower panel). b % CTLA-4+ cells within CD8+ T cells (cohort 1 upper panel, cohort 2 lower panel). c % IFNγ+ cells within CD8+ T cells (cohort 1 upper panel, cohort 2 lower panel). d % IL-2+ cells within CD8+ T cells (cohort 1 upper panel, cohort 2 lower panel). e % TNFα+ cells within CD8+ T cells (cohort 1 upper panel, cohort 2 lower panel). f % CD107a+ cells within CD8+ T cells (cohort 1 upper panel, cohort 2 lower panel). g % MIP1β+ cells within CD8+ T cells (cohort 1 upper panel, cohort 2 lower panel). *Depicts the true responses

When we plotted the percentages of double-positive cells in the CD4 and CD8 population, the low cell numbers precluded a proper analysis. Moreover, we found low responses to peptide pools 2 and 3, which comprised peptides of the TTFC part of the vaccine construct. In cohort 2 (2 mg TTFC-E7SH), more patients showed an immunological effect after stimulation with peptide pools 2 and 3 compared to the patients in cohort 1 (0.2 mg TTFC-E7SH) (see Supplementary Figures 2–5).

In addition, functional cellular immune responses to the TTFC-E7SH vaccine were assessed by a validated 4-days IFNγ-ELISPOT assay (see Supplementary Figure 6). At baseline, none of the patients showed a T-cell response to E7.1 or E7.2 peptide pool. One patient (#3) had a modest response to the E7.2 peptide pool after the first 3 vaccinations (T = week 2; spots at week 0 were 1/100,000 cells and were 12/100,000 cells at week 2), which was diminished at week 4 (8/100,000 cells), finally disappeared at week 6 (<1/100,000 cells), and was displayed again at T = week 8 (17/100,000 cells). None of the patients showed a response to the E7.1 peptide pool. In each dose group, 0.2 and 2 mg, 2 out of 6 patients showed a response to the peptide pool. So, in total, 4 out of the 12 patients showed a response to the peptide pool containing also the E7 shuffled peptides. The recall antigen (MRM)-specific T-cell responses did not show an increase in all 12 treated patients, indicating that the general immune response remained the same.

Discussion

The novel DNA tattoo vaccination technique used in this study was well tolerated in all treated patients. Moreover, the tattoo-induced skin damage was completely reversible. Vaccine-induced T-cell responses were found in 4 out of 12 patients when analyzed by IFNγ-ELISPOT, and with multiparametric flow cytometry all patients had low but detectable T-cell responses. Thus, TTFC-E7SH DNA tattooing is able to trigger an immune response in 33.3% of the patients and suggests that this application, tested for the first time in humans, shows good potential as a route of administration for DNA vaccination.

However, in the analysis by multiparametric flow cytometry, only low HPV16 E7-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses could be observed in the patients. Low immunogenicity was also observed in a previous trial from Trimble et al., where they vaccinated HPV16+ CIN patients with an E7 HPV DNA vaccine [25]. In a recently published trial in patients with CIN lesions, in whom the DNA vaccine VGX-3100 (containing plasmid encoding for both HPV16 E6 and E7) was administered intramuscularly followed by intradermal electroporation, a robust vaccine-induced T-cell response and histological regression was induced [19]. In previous peptide vaccination trials, it was shown that the E6 oncoprotein is more immunogenic than E7. Moreover, in most cases, an E7 response is only observed in combination with an E6 response [15, 29]. Hence, it seems that the E7 protein by itself has only low stimulatory capacity in humans. Therefore, in a new phase I/II trial we will use an improved DNA vaccine format, targeting not only E7 but also E6. We have produced two novel clinical DNA vaccines (sig-HELP-E6SH-kdel and sig-HELP-E7SH-kdel). These encode the fusion protein of the carrier sequence sig-HELP-kdel and the shuffled version of the HPV16 E6 oncoprotein and E7 oncoprotein, respectively. The sig element provides Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) targeting of the produced fusion protein. The HELP element provides three universal CD4+ helper epitopes. The kdel elements provide retention in the ER. The sig-HELP-kdel carrier sequences make these vaccines very immunogenic in animal models, and to our knowledge, the sig-HELP-kdel fusions are the most immunogenic DNA vaccines ever described in mice [30]. Furthermore, we have tested a new vaccination schedule (day 0, 14, 28, and 42 days) that is more patient friendly and equally immunogenic in mice as the vaccination schedule used in this study (data not published). The new phase I/II DNA vaccination trial, which is currently enrolling patients, targets both E6 and E7, a superior carrier molecule and improved vaccination schedule.

Next to a potential problem of the potency of the currently tested DNA vaccine TTFC-E7SH, it may also be that the DNA tattoo administration is not effective enough in humans. In fact, we have shown in a human skin model that DNA tattoo administration is rather inefficient [23]. Furthermore, the ability to translate DNA tattoo administration to human application is difficult to predict from animal models since the structure of animal and human skin is very different. Ongoing DNA vaccination experiments in a porcine model, which has similar structure as human skin, should teach us if it is possible to induce systemic vaccine directed T-cell responses in a larger animal model with a similar skin morphology as humans.

We observed a small and transient increase in expression levels of the co-inhibitory molecules PD-1 and CTLA-4 (33.3% of patients and 16.7–25%, respectively), on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. These responses were only observed at week 2, 4, and 6, and were no longer detected at week 8. This suggests a temporary T-cell response, and no memory response, probably due to insufficient induction. The PD-1 pathway plays an important role in tumor-induced immunosuppression in a variety of tumors since PD-L1 can bind to PD-1 on T cells thereby disrupting T-cell activity. However, in melanoma patients, PD-1+ T cells are indicative of the presence of patient-specific antitumor T-cell responses [31, 32]. We hypothesize that the observed increased expression of PD-1 in our study suggests the presence of vaccine-induced HPV-specific T cells. Further study is needed to confirm this. The rise of PD-1 levels and the subsequent decline following activation were also observed in a study with macaques; however, in contrast to our results they observed a concomitant increase in IFNγ expression [33]. Unfortunately, due to the low cell numbers we were not able to check for T-cell polyfunctionality, therefore, we cannot state if these PD-1+ T cells are just activated T cells or exhausted T cells with impaired cytokine production [34].

Next to the increase in PD-1+ T cells, we observed an increase in CTLA-4 expression in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Whether this is indicative for regulatory T cells is unknown, as we have not included FOXP3 as an additional marker to determine whether these cells are showing activation status or are indeed regulatory T cells induced by the vaccine or disease [35]. Furthermore, a robust gating strategy for regulatory T-cell flow cytometry analysis is needed [36], and will be used in the improved DNA vaccine trial.

In conclusion, DNA tattoo vaccination was shown to be safe. Limited CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell vaccine-induced immune responses and absence of clinical responses were observed in uVIN patients after TTFC-E7SH DNA tattoo vaccination. Therefore, an improved DNA vaccine format will be studied in a new phase I/II trial in patients with uVIN.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Freek Groenman of the Netherlands Cancer Institute – Antoni van Leeuwenhoek hospital (NKI-AVL, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) for including patients. We also like to thank the Rational molecular Assessment Innovative Drug selection (RAIDs) consortium (http://www.raids-fp7.eu). This trial is part of the RAIDs project and received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Program for Research, Technological Development, and Demonstration (Grant No. 304810).

Abbreviations

- CTCAE

Common terminology criteria for adverse events

- sig-HELP-E6SH-kdel

Vaccine encoding the fusion protein of the carrier sequence sig-HELP-kdel and the shuffled version of the HPV16 E6 oncoprotein

- sig-HELP-E7SH-kdel

Vaccine encoding the fusion protein of the carrier sequence sig-HELP-kdel and the shuffled version of the HPV16 E7 oncoprotein

- SLP

Synthetic long peptide

- TTFC

Tetanus toxin fragment C

- TTFC-E7SH

Vaccine encoding the fusion protein of TTFC and a shuffled variant of HPV16 E7

- uVIN

Usual type vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia

- VIN

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Sideri M, Jones RW, Wilkinson EJ, Preti M, Heller DS, Scurry J, Haefner H, Neill S. Squamous vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: 2004 modified terminology, ISSVD Vulvar Oncology Subcommittee. J Reprod Med. 2005;50(11):807–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buscema J, Naghashfar Z, Sawada E, Daniel R, Woodruff JD, Shah K. The predominance of human papillomavirus type 16 in vulvar neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71(4):601–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hording U, Junge J, Poulsen H, Lundvall F. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia III: a viral disease of undetermined progressive potential. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;56(2):276–279. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1995.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serrano B, de Sanjose S, Tous S, Quiros B, Munoz N, Bosch X, Alemany L. Human papillomavirus genotype attribution for HPVs 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58 in female anogenital lesions. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(13):1732–1741. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JS, Backes DM, Hoots BE, Kurman RJ, Pimenta JM. Human papillomavirus type-distribution in vulvar and vaginal cancers and their associated precursors. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(4):917–924. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31819bd6e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Beurden M, ten Kate FJ, Smits HL, Berkhout RJ, de Craen AJ, van der Vange N, Lammes FB, ter Schegget J. Multifocal vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia grade III and multicentric lower genital tract neoplasia is associated with transcriptionally active human papillomavirus. Cancer. 1995;75(12):2879–2884. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950615)75:12<2879::AID-CNCR2820751214>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuhn L, Sun XW, Wright TC., Jr Human immunodeficiency virus infection and female lower genital tract malignancy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1999;11(1):35–39. doi: 10.1097/00001703-199901000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van de Nieuwenhof HP, van der Avoort IA, de Hullu JA. Review of squamous premalignant vulvar lesions. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;68(2):131–156. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones RW, Rowan DM, Stewart AW. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: aspects of the natural history and outcome in 405 women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(6):1319–1326. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000187301.76283.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Seters M, van Beurden M, de Craen AJ. Is the assumed natural history of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia III based on enough evidence? A systematic review of 3322 published patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97(2):645–651. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andreasson B, Bock JE. Intraepithelial neoplasia in the vulvar region. Gynecol Oncol. 1985;21(3):300–305. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(85)90267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rettenmaier MA, Berman ML, DiSaia PJ. Skinning vulvectomy for the treatment of multifocal vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;69(2):247–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sykes P, Smith N, McCormick P, Frizelle FA. High-grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN 3): a retrospective analysis of patient characteristics, management, outcome and relationship to squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva 1989–1999. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;42(1):69–74. doi: 10.1111/j.0004-8666.2002.00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daayana S, Elkord E, Winters U, Pawlita M, Roden R, Stern PL, Kitchener HC. Phase II trial of imiquimod and HPV therapeutic vaccination in patients with vulval intraepithelial neoplasia. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(7):1129–1136. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenter GG, Welters MJ, Valentijn AR, Lowik MJ, Berends-van der Meer DM, Vloon AP, Essahsah F, Fathers LM, Offringa R, Drijfhout JW, Wafelman AR, Oostendorp J, Fleuren GJ, van der Burg SH, Melief CJ. Vaccination against HPV-16 oncoproteins for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(19):1838–1847. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Poelgeest MI, Welters MJ, Vermeij R, Stynenbosch LF, Loof NM, Berends-van der Meer DM, Lowik MJ, Hamming IL, van Esch EM, Hellebrekers BW, van Beurden M, Schreuder HW, Kagie MJ, Trimbos JB, Fathers LM, Daemen T, Hollema H, Valentijn AR, Oostendorp J, Oude Elberink JH, Fleuren GJ, Bosse T, Kenter GG, Stijnen T, Nijman HW, Melief CJ, van der Burg SH. Vaccination against Oncoproteins of HPV16 for noninvasive vulvar/vaginal lesions: lesion clearance is related to the strength of the T-cell response. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(10):2342–2350. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welters MJ, Kenter GG, de Vos van Steenwijk PJ, Lowik MJ, Berends-van der Meer DM, Essahsah F, Stynenbosch LF, Vloon AP, Ramwadhdoebe TH, Piersma SJ, van der Hulst JM, Valentijn AR, Fathers LM, Drijfhout JW, Franken KL, Oostendorp J, Fleuren GJ, Melief CJ, van der Burg SH (2010) Success or failure of vaccination for HPV16-positive vulvar lesions correlates with kinetics and phenotype of induced T-cell responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107 (26):11895–11899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Trimble CL, Morrow MP, Kraynyak KA, Shen X, Dallas M, Yan J, Edwards L, Parker RL, Denny L, Giffear M, Brown AS, Marcozzi-Pierce K, Shah D, Slager AM, Sylvester AJ, Khan A, Broderick KE, Juba RJ, Herring TA, Boyer J, Lee J, Sardesai NY, Weiner DB, Bagarazzi ML. Safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity of VGX-3100, a therapeutic synthetic DNA vaccine targeting human papillomavirus 16 and 18 E6 and E7 proteins for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2015;386(10008):2078–2088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00239-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rice J, Ottensmeier CH, Stevenson FK. DNA vaccines: precision tools for activating effective immunity against cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(2):108–120. doi: 10.1038/nrc2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bins AD, Jorritsma A, Wolkers MC, Hung CF, Wu TC, Schumacher TN, Haanen JB. A rapid and potent DNA vaccination strategy defined by in vivo monitoring of antigen expression. Nat Med. 2005;11(8):899–904. doi: 10.1038/nm1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verstrepen BE, Bins AD, Rollier CS, Mooij P, Koopman G, Sheppard NC, Sattentau Q, Wagner R, Wolf H, Schumacher TN, Heeney JL, Haanen JB. Improved HIV-1 specific T-cell responses by short-interval DNA tattooing as compared to intramuscular immunization in non-human primates. Vaccine. 2008;26(26):3346–3351. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.03.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van den Berg JH, Nujien B, Beijnen JH, Vincent A, van Tinteren H, Kluge J, Woerdeman LA, Hennink WE, Storm G, Schumacher TN, Haanen JB. Optimization of intradermal vaccination by DNA tattooing in human skin. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20(3):181–189. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oosterhuis K, Ohlschlager P, van den Berg JH, Toebes M, Gomez R, Schumacher TN, Haanen JB. Preclinical development of highly effective and safe DNA vaccines directed against HPV 16 E6 and E7. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(2):397–406. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henken FE, Oosterhuis K, Ohlschlager P, Bosch L, Hooijberg E, Haanen JB, Steenbergen RD. Preclinical safety evaluation of DNA vaccines encoding modified HPV16 E6 and E7. Vaccine. 2012;30(28):4259–4266. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trimble CL, Peng S, Kos F, Gravitt P, Viscidi R, Sugar E, Pardoll D, Wu TC. A phase I trial of a human papillomavirus DNA vaccine for HPV16+ cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(1):361–367. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Przybylowski M, Bartido S, Borquez-Ojeda O, Sadelain M, Riviere I. Production of clinical-grade plasmid DNA for human Phase I clinical trials and large animal clinical studies. Vaccine. 2007;25(27):5013–5024. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.04.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quaak SG, van den Berg JH, Toebes M, Schumacher TN, Haanen JB, Beijnen JH, Nuijen B. GMP production of pDERMATT for vaccination against melanoma in a phase I clinical trial. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008;70(2):429–438. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urthaler J, Buchinger W, Necina R. Improved downstream process for the production of plasmid DNA for gene therapy. Acta Biochim Pol. 2005;52(3):703–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Poelgeest MI, Welters MJ, van Esch EM, Stynenbosch LF, Kerpershoek G, van Persijn van Meerten EL, van den Hende M, Lowik MJ, Berends-van der Meer DM, Fathers LM, Valentijn AR, Oostendorp J, Fleuren GJ, Melief CJ, Kenter GG, van der Burg SH (2013) HPV16 synthetic long peptide (HPV16-SLP) vaccination therapy of patients with advanced or recurrent HPV16-induced gynecological carcinoma, a phase II trial. J Transl Med 11:88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Oosterhuis K, Aleyd E, Vrijland K, Schumacher TN, Haanen JB. Rational design of DNA vaccines for the induction of human papillomavirus type 16 E6- and E7-specific cytotoxic T-cell responses. Hum Gene Ther. 2012;23(12):1301–1312. doi: 10.1089/hum.2012.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gros A, Parkhurst MR, Tran E, Pasetto A, Robbins PF, Ilyas S, Prickett TD, Gartner JJ, Crystal JS, Roberts IM, Trebska-McGowan K, Wunderlich JR, Yang JC, Rosenberg SA. Prospective identification of neoantigen-specific lymphocytes in the peripheral blood of melanoma patients. Nat Med. 2016;22(4):433–438. doi: 10.1038/nm.4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmadzadeh M, Johnson LA, Heemskerk B, Wunderlich JR, Dudley ME, White DE, Rosenberg SA. Tumor antigen-specific CD8 T cells infiltrating the tumor express high levels of PD-1 and are functionally impaired. Blood. 2009;114(8):1537–1544. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hokey DA, Johnson FB, Smith J, Weber JL, Yan J, Hirao L, Boyer JD, Lewis MG, Makedonas G, Betts MR, Weiner DB. Activation drives PD-1 expression during vaccine-specific proliferation and following lentiviral infection in macaques. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38(5):1435–1445. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fourcade J, Sun Z, Benallaoua M, Guillaume P, Luescher IF, Sander C, Kirkwood JM, Kuchroo V, Zarour HM. Upregulation of Tim-3 and PD-1 expression is associated with tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cell dysfunction in melanoma patients. J Exp Med. 2010;207(10):2175–2186. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Burg SH, Piersma SJ, de Jong A, van der Hulst JM, Kwappenberg KM, van den Hende M, Welters MJ, Van Rood JJ, Fleuren GJ, Melief CJ, Kenter GG, Offringa R. Association of cervical cancer with the presence of CD4+ regulatory T cells specific for human papillomavirus antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(29):12087–12092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704672104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santegoets SJ, Dijkgraaf EM, Battaglia A, Beckhove P, Britten CM, Gallimore A, Godkin A, Gouttefangeas C, de Gruijl TD, Koenen HJ, Scheffold A, Shevach EM, Staats J, Tasken K, Whiteside TL, Kroep JR, Welters MJ, van der Burg SH. Monitoring regulatory T cells in clinical samples: consensus on an essential marker set and gating strategy for regulatory T cell analysis by flow cytometry. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2015;64(10):1271–1286. doi: 10.1007/s00262-015-1729-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.