Abstract

Tumor-derived exosomes (TEX) can induce a specific antitumor immune response and have been developed as a promising tumor vaccine. Despite promising preclinical data, TEX exhibit relatively low efficacy and limited clinical benefit in clinical trials. In the present study, we investigated whether exosomes from the TGF-β1 silenced L1210 cells (LEXTGF-β1si) can enhance the efficacy of DC-based vaccines. We silenced TGF-β1 in L1210 cells with a lentiviral shRNA vector and prepared the LEXTGF-β1si. It was shown that LEXTGF-β1si can significantly decrease TGF-β1 expression of dendritic cells (DC) and effectively promote their maturation and immune function. In addition, DC pulsed with LEXTGF-β1si (DCLEX-TGF-β1si) more effectively promoted CD4+ T cell proliferation in vitro and Th1 cytokine secretion and induced tumor-specific CTL response. This response was higher in potency compared to that noted by the other two formulations. Moreover, DCLEX-TGF-β1si inhibited tumor growth more efficiently than other formulations did as the preventive or therapeutic tumor vaccine. Accordingly, these findings revealed that DCLEX-TGF-β1si induced a more potent antigen-specific anti-leukemic immunity than DC pulsed with exosomes from non-manipulated L1210 cells. This indicated that the targeting of DC by LEXTGF-β1si may be used as a promising approach for leukemia immunotherapy.

Keywords: TGF-β1, Leukemia, Exosomes, Dendritic cells, Immunotherapy

Introduction

Minimal residual leukemia cells (MRLs) constitute a major threat to leukemia patients [1]. The traditional strategies for the eradication of MRLs include high-dose chemotherapy and hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT). However, the therapeutic efficacy of the aforementioned treatments has been less effective, due to the insufficiency of the eradication of MRLs. Besides, this may cause serious adverse effects, such as myelosuppression and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Consequently, a more efficient and safe approach to eliminate MRLs is required for the prevention of the relapse of leukemia. Currently, several clinical studies have demonstrated that antitumor vaccines are effective in eliminating MRLs and may be a promising strategy to prevent leukemia relapse and improve leukemia-free survival [2, 3].

Recent studies on exosome-based vaccines have provided substantial evidences with regard to the development of an ideal tumor vaccine [4, 5]. Exosomes comprise a group of micro-vesicles with a diameter of 40–100 nm, which contain a series of cellular proteins inherited from parental cells [6, 7]. Tumor-derived exosomes (TEX) contain an array of tumor-associated antigens (TAA) and can transfer TAA to DC, in order to trigger a tumor-specific CTL response [4, 8]. Thus, exosomes are considered candidates for the development of cancer vaccines with promising therapeutic efficacy [9–12]. However, certain studies have shown that TEX alone, in the absence of manipulation, are less efficient in promoting T cell activation, and may enhance tumor progression and promote immune escape [13, 14]. Therefore, it is imperative to develop an optimized TEX-based vaccine in order to achieve a satisfactory efficacy. Notably, a number of studies have shown that the genetic modification of original tumor cells could be a feasible and effective approach to improve the immunogenicity of TEX [15–19]. Exosomes derived from Rab27a-overexpressing cancer cells induced potent maturation of DC and elicited an antitumor immunity with higher efficacy compared with non-manipulated TEX [15]. Exosomes derived from Interleukin (IL)-2 gene-modified tumor cells triggered a highly efficient CTL response and exerted a significant inhibitory effect on tumor growth [16]. In addition, similar effects were observed by modification of IL-18 expression in parental cancer cells [17]. With the exception of gene modification, the use of exosome-pulsed DC is an additional optimized strategy. It has been demonstrated that TEX can be internalized, processed, and presented by DC [4, 5, 20]. TEX-pulsed DC induce a CTL response of greater efficacy that results in potent antitumor immunity than TEX alone, since DC can be activated in vitro in the absence of the interference of the immunosuppressive environment in vivo [4]. Therefore, the vaccination with TEX-pulsed DC can be considered as an alternative strategy with high efficacy for the enhancement of the immunogenicity of TEX-based vaccines.

Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) is one of the most potent immunosuppressive cytokines that is present in certain types of TEX [14, 21]. TGF-β1 plays a crucial role on the TEX-mediated immunosuppression effect, via the impairment of the maturation and function of DC [22], the decrease in the cytotoxicity of natural killer (NK) cells [23], the induction of regulatory T cells [13], and the inhibition of effective CTL response. In the present study, the expression of TGF-β1 in L1210 leukemia cells was silenced by the use of a lentiviral vector that included TGF-β1 small hairpin RNA (shRNA). The resulting TGF-β1-silenced LEX (LEXTGF-β1si) facilitated the maturation and function of DC. Importantly, immunization with DC pulsed with LEXTGF-β1si (DCLEX-TGF-β1si) promoted efficient CD4+ T-cell proliferation, stimulated Type I cytokine secretion, and induced an antigen-specific CTL response that resulted in significant inhibition of tumor growth in mouse models. The data suggested that the stimulation of anti-leukemic immunity by DC pulsed with LEXTGF-β1si was greater compared with that noted by DC pulsed with non-modified exosomes. TGF-β1 silenced exosome-based vaccines may be considered as a promising strategy for the development of exosome-based immunotherapy of cancer.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and animals

The L1210 cell, an acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell line from DBA/2 mice, was purchased from the Shanghai Institute for Biological Science (Shanghai, China). L1210 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 100 μ/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in an incubator containing 5% CO2. The cells that were used as the source of exosomes were pre-transferred to petri dishes containing serum-free culture medium (AIMV) in order to prevent contamination with serum exosomes. 6- to 8-week-old DBA/2 female mice were purchased from the Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center (Shanghai, China) and were housed under standard environmental conditions. All animal experiments were conducted according to the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Xinhua Hospital Affiliated to the Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China.

Lentiviral TGF-β1 shRNA vector construction and lentivirus production

A total of three self-complementary oligonucleotide pairs carrying shRNA sequences that target mouse TGF-β 1 were designed and synthesized (Shanghai Hanbio Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China). A scrambled shRNA sequence was used as a negative control. Scrambled shRNA oligonucleotides and TGF-β1 shRNA-incorporated oligonucleotides were ligated into lentiviral frame plasmids. The recombinant plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli (E. coli), and positive recombinant clones were selected by PCR. 293T cells were co-transfected with the recombinant lentiviral vector (10 μg), pSPAX2 vector (10 μg), and the pMD2G vector (10 μg) in order to produce a lentivirus. Following 72 h of transfection, the supernatants containing lentiviral particles were harvested, filtered through a 0.45-μm membrane, and concentrated via ultracentrifugation. The lentiviral vectors expressed the green fluorescence protein (GFP). The intensity of fluorescence ensured the titration and measurement of the lentiviral infection efficiency. TGF-β1 interference efficiency was assayed by RT-PCR and flow cytometric analysis. The shRNA3 with the highest interference efficiency for TGF-β1 mRNA and protein expression determined the selection of the lentiviral vector that was used in the experiments.

The shRNA1 sequence used was as follows: top strand: GATCCGCGAAGCGGACTACTATGCTAATTCAAGAGATTAGCATAGTAGTCCGCTTCGTTTTTTC; bottom strand: AATTGAAAAAACGAAGCGGACTACTATGCTAATCTCTTGAATTAGCATAGTAGTCCGC TTCGCG. The shRNA2 sequence utilized was as follows: top strand: GATCCGAGCAACATGTGGAAC TCTACCAGATTCAAGAGATCTGGTAGAGTTCCACATGTTGCTCTTTTTTC; bottom strand: AATTGAAA AAAGAGCAACATGTGGAA CTCTACCAGATCTCTTGAATCTGGTA GAGTTCCACATGTTGCTCG. The shRNA3 sequence was the following: top strand: GATCCGCGGAGAGCCCTGGATACCAACTATTTT CAAGAGAAATAGTTGGTATCCAGGGCTCTCCGTTTTTTC; bottom strand: AATTGAAAAAACGGAGA GCCCTGGATACCAACTATTTCTCTTGAAAATAGTTGGTATCCAGGGCTCTCCGCG.

Isolation of exosomes

Exosomes were isolated as described previously [20]. The exosomes from non-manipulated L1210 cells were assigned as LEX, whereas the exosomes obtained from the TGF-β1 silenced L1210 cells and exosomes from L1210 cells transfected with a control shRNA sequence were named as LEXTGF-β1si and LEXGFP, respectively.

Generation of bone marrow-derived DC and flow cytometric analysis of DC

DC were generated from bone marrow-derived precursors of DBA/2 mice and cultured as previously described [4]. Following cell culture for 6 days, BMDC were pulsed with LEX, LEXGFP, and LEXTGF-β1si, at a density of 1 × 106 cells/mL, in serum-free AIM-V medium for 24 h. The cultured DC were harvested for further use. DC that was pulsed with LEX, LEXGFP, and LEXTGF-β1si were assigned as DCLEX, DCLEX-GFP, and DCLEX-TGF-β1si, respectively.

Electron microscopy

Exosome preparations were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and loaded onto the electron microscopy grids that were coated with formvar/carbon. The preparations were subjected to intensity contrast with 2% phosphotungstic acid and were observed under a Philips CM12 transmission electron microscope operating at 80 kV.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The levels of TGF-β1, IL-12p70, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α that were secreted by exosome-pulsed DC, and the levels of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and IL-2 that were released from CD4+ T-cells were detected by ELISA kits following the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of each sample was determined based on a standard curve.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analyses of the exosomal indicators, CD9, CD63, and heat shock protein (HSP) 70, were conducted as described previously [15]. The immuno-reactive protein bands on the membrane were visualized using a chemiluminescence kit and analyzed by Image Lab software.

Proliferation assay

Splenocytes from the immunized mice were harvested and depleted of red blood cells. Consequently, CD4+ T-cells were isolated using a EasySep™ mouse CD4+ T-cell isolation kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). CD4+ T-cell (2 × 105 cells/well), were labeled with 5 μM of CFSE for 10 min at room temperature, and co-cultured with irradiated L1210 cells (2 × 104 cells) or p388 cells (2 × 104 cells) for a 7-day period. The cells were harvested and the proliferation of CD4+ T-cells was evaluated by flow cytometry.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxic responses were evaluated according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). Briefly, splenic CD8+ T-cells were isolated from immunized mice using EasySep™ mouse CD8+ T Cell Isolation Kit (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) and cultured at a density of 5 × 105 cells/mL. The cells were treated with the following formulations: PBS (control), irradiated (4000 rads) non-pulsed DC (0.5 × 105/mL), irradiated (4000 rads) DCLEX (0.5 × 105/mL), irradiated (4000 rads) DCLEX-GFP (0.5 × 105/mL), and irradiated (4000 rads) DCLEX-TGF-β1si (0.5 × 105/mL). The treatments were conducted at 37 °C in complete medium in the presence of recombinant mouse IL-2 (100 μg/mL). Following 7 days of treatment, the activated T cells were harvested as effector cells. L1210 cells were used as target cells, whereas p388 cells served as control target cells. The corresponding target cells (1 × 104/mL) were mixed at different ratios with effector cells for 4 h at 37 °C. The spontaneous/maximal release ratio was lower than 20% (<20%) in all experiments. The specific lysis (%) was calculated as follows: (experimental LDH release − effector cells − target spontaneous LDH release)/(target maximum LDH release) × 100.

Animal study

To investigate the protective immunity of LEX-based vaccines against leukemia, DBA/2 mice DBA/2 mice were immunized by subcutaneous (s.c.) injection to the inner side of the thighs with PBS (control), non-pulsed DC (1 × 106 cells/mouse), DCLEX (1 × 106 cells/mouse), DCLEX-GFP (1 × 106 cells/mouse), and DCLEX-TGF-β1si (1 × 106 cells/mouse), respectively. The injected mice were boosted twice with the LEX-based vaccine formulations for a 3-day interval. Following 7 days of the last immunization, the mice were s.c. injected with L1210 cells (0.5 × 106 cells/mouse) to the outer side of the same thighs that were used for the immunization, and the tumor growth was monitored daily.

DBA/2 mice were subcutaneously injected with L1210 cells (0.5 × 106 cells/mouse) to the outer side of their thighs in order to examine the therapeutic effect on the established tumors. Following 5 days of inoculation, the tumors became palpable (approximately 3.5 mm in diameter) and an injection of the aforementioned vaccines was administered to the inner side of the thighs of the inoculated mice. Animal mortality, tumor growth, and tumor regression were monitored daily using a caliper for a total period of 10 weeks.

Flow cytometry

For phenotype analysis of DC, the cells were washed with PBS twice and then incubated with fluorescent-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAb) against CD80, CD86, and MHC II for 30 min at room temperature. PBMCs derived from immunized tumor-bearing mice were further pre-stimulated with PMA (25 ng/ml) and ionomycin (0.5 µg/ml) in the presence of brefeldin A (5 µg/ml) for 4 h. The cells were subsequently incubated with a panel of FITC-conjugated antibodies against CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD25 for 30 min. The expression of IFN-γ, Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and Foxp3 was investigated by flow cytometry following fixation, permeabilization, and incubation with fluorescent-conjugated antibodies against IFN-γ, TNF-α, and Foxp3. The experiments were conducted in triplicate and repeated at least three times independently.

Statistical analysis

Statistical differences between each group were analyzed by the Student’s t test. The data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. A p value of less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Two asterisks (**) denote p < 0.01 and one asterisk (*) denotes p < 0.05.

Results

Properties of the exosomes derived from TGF-β1-silenced L1210 cells

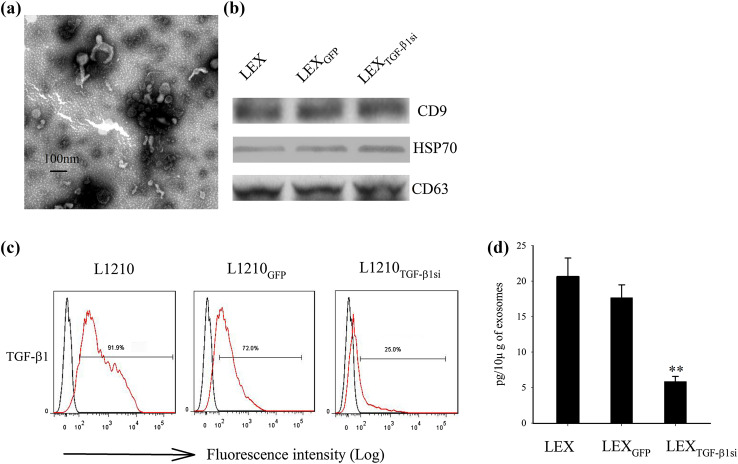

L1210 cells were transduced with a mock or TGF-β1 shRNA-incorporated lentivirus, and the exosomes derived from LEXTGF-β1si were determined by electron microscopy and Western blot analysis. LEXTGF-β1si ranged from 40 to 100 nm in diameter and exhibited the dimpled, cup-shaped characteristic morphology (Fig. 1a). Western blot analysis indicated that Hsp70, CD9, and CD63, that are considered as typical exosomal proteins, were abundant in all types of exosomes derived from L1210 cells (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, the flow cytometry and ELISA assays were used to examine whether the TGF-β1 shRNA-containing lentivirus transfection could influence the expression pattern of TGF-β1 at both the cellular and exosomal levels. TGF-β1 expression in L1210 cells was markedly decreased by lentivirus-mediated TGF-β1 shRNA (Fig. 1c) infection. In addition, the amount of TGF-β1 in LEX was 16.9 ± 2.1 pg/10 μg, which indicated that TGF-β1 was present in LEX (Fig. 1d). In addition, the amount of TGF-β1 in LEXTGF-β1si (5.82 ± 0.7 pg/10 μg) was significantly lower compared to that noted in the control groups (p < 0.01). This finding indicated that the downregulation of TGF-β1 in LEX was via the silencing of the TGF-β1 gene in the parental leukemia cells.

Fig. 1.

Phenotypic analysis of LEXTGF-β1si. a Transmission electron micrograph image of an exosome derived from L1210 cells transduced with TGF-β1 shRNA-incorporated lentivirus; b Western blot analysis demonstrating the presence of typical exosomal protein markers, CD9, CD63, and HSP70. c Analysis of TGF-β1 expression by flow cytometry in L1210 cells in the absence of gene modification. L1210 cells were transduced with null vector, and/or TGF-β1 shRNA-incorporated lentivirus; d TGF-β1 levels in exosome preparations (pg/10 μg of exosomes) were analyzed by ELISA assay. Experiments were performed in triplicate. One representative experiment is shown

TGF-β1-silenced LEX efficiently promoted the maturation of dendritic cells and downregulated TGF-β1 production from DC

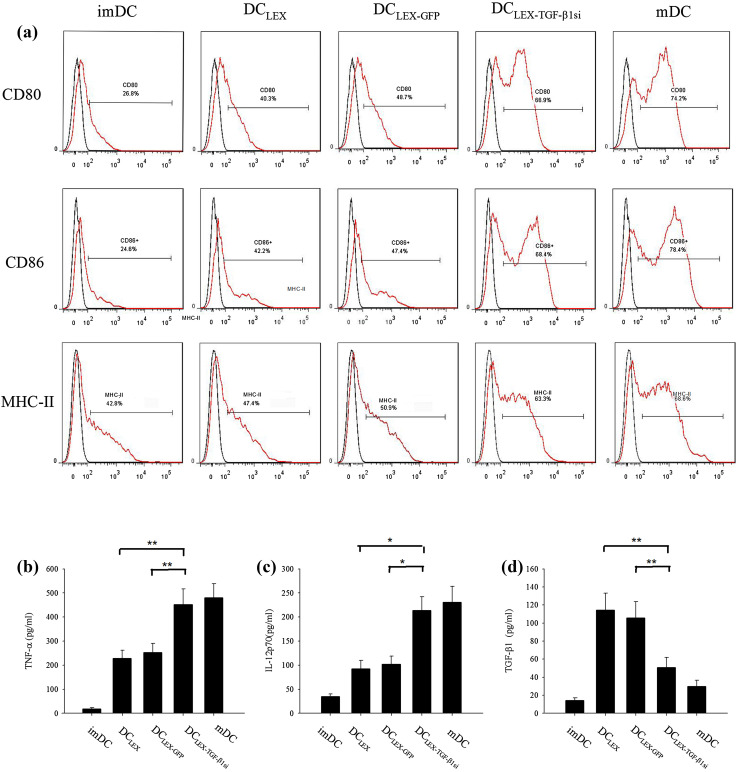

Previous studies have demonstrated that exosomes can be consumed by DC, while the exosomal molecules including tumor antigen can be transferred to DC [4, 20, 24]. Based on these observations, the effects of LEXTGF-β1si on the biological properties of DC were examined. Following incubation with three types of exosomes (10 µg/ml) for 24 h, the expressions of CD80, CD86, and MHC-II in DC were markedly increased compared with those noted in immature DC. Stimulation with LEXTGF-β1si exhibited the highest increase in the expression of aforementioned markers compared with the stimulation with other two exosomes. The increase noted was comparable with the effect noted by lipopolysaccharide (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, the secretion of IL-12p70 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) from DC in the LEXTGF-β1si group was significantly increased compared to LEX and LEXGFP groups (Fig. 2b, c, p < 0.05). Interestingly, the TGF-β1 level in the DC culture was significantly increased following LEX stimulation. Since TGF-β1 in the LEX was less than the TGF-β1 amount increased in DC culture, this finding indicated that the increased expression of TGF-β1 was secreted by DC in response to exosome stimulation. Notably, it was observed that TGF-β1 production from LEXTGF-β1si pulsed DC were significantly decreased compared with that from LEX and/or LEXGFP pulsed DC groups (Fig. 2d, p < 0.01). Taken together, the results indicated that LEXTGF-β1si caused a significant downregulation of TGF-β1 secretion from DC and efficiently facilitated the maturation and immune activities of DC.

Fig. 2.

Effect of LEX TGF-β1si on the maturation and activation of DC. Immature DC were incubated for 24 h with 10 µg/mL of LEX, LEXGFP, or LEX TGF-β1si, respectively. Immature DC in the absence of stimulation and mature DC were used as the controls. Flow cytometry analysis of CD80, CD86, and MHC II expression on the surface of DC (a). The levels of TNF-α (b), IL-12p70 (c), and TGF-β1 (d) level in supernatants of DC were measured by ELISA. imDC immature dendritic cell, mDC mature dendritic cells. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 denote statistically significant differences. Data are representative of three independent experiments and expressed as the mean ± SEM

DCLEX-TGF-β1si promoted CD4+ T cell proliferation and induced efficient antigen-specific anti-leukemic CTL response

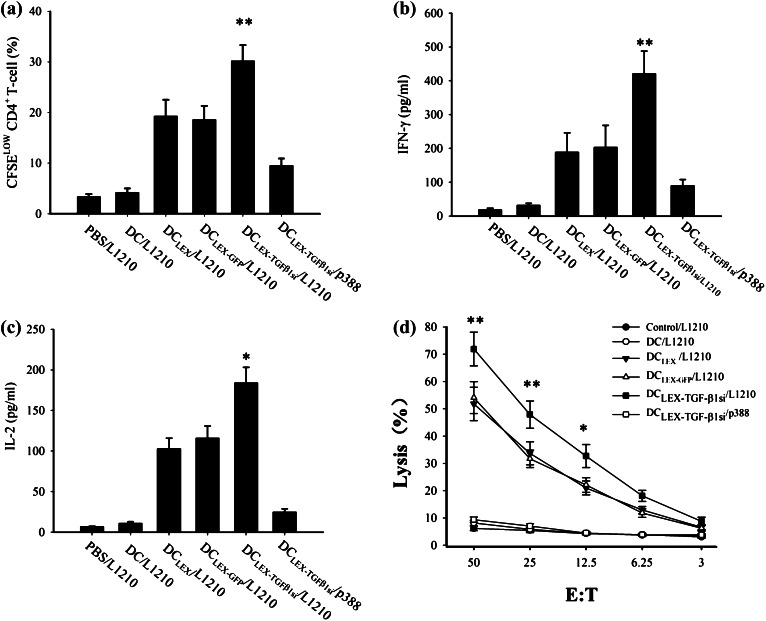

To investigate whether DCLEX-TGF-β1si immunization can elicit specific CD4+ T-cells immunity with greater potency compared with DCLEX and DCLEX-GFP immunization, the proliferation of CD4+ T-cells from the mice that were immunized with PBS, non-pulsed DC, DCLEX, DCLEX-GFP, and DCLEX-TGF-β1si was evaluated. The secretion levels of Type I cytokine, IL-2, and IFN-γ from CD4+ T cells in each group were further measured. Immunization with DCLEX-TGF-β1si resulted in a higher level of CD4+ T cell proliferation compared with that noted in the remaining groups (Fig. 3a, p < 0.01). In addition, the levels of IL-2 and IFN-γ from the CD4+ T-cell supernatants were increased markedly in the DCLEX, DCLEX-GFP, and DCLEX-TGF-β1si groups compared with those noted in the non-pulsed DC and PBS groups. The CD4+ T-cells derived from DCLEX-TGF-β1si-immunized mice secreted the highest levels of IL-2 and IFN-γ among all groups (Fig. 3b, c, p < 0.05). Taken together, the results indicated that immunization with DCLEX-TGF-β1si induced a more potent antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell immunity compared with DCLEX.

Fig. 3.

Immunization with DCLEX-TGFβ1si induced a potent CD4+ T cell proliferation, type I cytokine secretion, and CTL response. The splenic CD4+ T cells were separated from DBA/2 mice that were i.v. immunized with PBS, non-pulsed DC, DCLEX, DCLEX-GFP, and DCLEX-TGF-β1s, respectively. Consequently, CD4+ T cells were incubated with irradiated L1210 cells for a 7-day period. T cell proliferation was evaluated by the CFSE labeling assay. The secretions of IFN-γ and IL-2 in the culture supernatants were determined by ELISA. a T cell proliferation. b, c IFN-γ and IL-2 secretion by T cells. d The splenic cells from immunized mice were stimulated with irradiated L1210 cells in the presence of mIL-2 in vitro for a 7-day period. Following stimulation the CD8+ T cells were separated and referred as effector cells. L1210 or p388 cells served as target cells and were mixed with effector cells at different ratios. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 denote statistically significant differences. Data are representative of three independent experiments

Based on the aforementioned findings, a cytotoxicity assay was conducted to evaluate the potential activity of DCLEX-TGF-β1si on priming of CD8+ T-cells. CD8+ T-cells that were separated from the DCLEX-TGF-β1si-immunized mice displayed the highest cytotoxic activity versus L1210 cells (71.5% killing; E:T ratio, 50:1), compared with that noted for DCLEX and/or DCLEX-GFP-immunized mice (52.3 and 51.8%, respectively; E:T ratio, 50:1, p < 0.01, Fig. 3d). No cytotoxic activity was observed in the non-pulsed DC and the PBS groups. Besides, the cytotoxic effect versus the p388 cells was undetectable, indicating that DCLEX-TGF-β1si exhibited the greatest potency regarding the antigen-specific CTL response. Taken together, the results indicate that DCLEX-TGF-β1si enhances the potency of the antigen-specific anti-leukemic CTL response.

DCLEX-TGF-β1si enhanced the protective immunity and therapeutic efficacy towards leukemia cells

Next, we investigated whether DCLEX-TGF-β1si can induce protective immunity against the attack of leukemia cells. DBA/2 mice were immunized with PBS, non-pulsed DC, and DC pulsed with each type of the exosomes (LEX, LEXGFP, and LEXTGF-β1si). Seven days after the last vaccination, all the mice were subcutaneously challenged with L1210 cells. Tumor growth was monitored daily during a 24-day observation period. As shown in Table 1, Tumor growth was present in all the mice injected with PBS and non-pulsed DC groups, whereas 57 ± 7% of the mice injected with DCLEX-GFP and 63 ± 7% of those injected with DCLEX had tumor growth within 24 days, indicating that LEX-targeted DC could induce protective immunity against leukemia cells. Interestingly, 73 ± 7% of the DCLEX-TGF-β1si-immunized mice were in tumor-free state during 24 days, revealing that LEX-pulsed DC induced stronger anti-leukemic immunity than LEX or LEXGFP-targeted DC.

Table 1.

DCLEX-TGF-β1si vaccine protects against tumor growth

| Vaccines | Tumor cell challenge | Incidence of tumor growth |

|---|---|---|

| PBS | L1210 | 100 ± 0% |

| DC | L1210 | 100 ± 0% |

| DCLEX | L1210 | 63 ± 7% |

| DCLEX-GFP | L1210 | 57 ± 7% |

| DCLEX-TGF-β1si | L1210 | 23 ± 7% |

DCLEX-TGF-β1si immunization induced specific anti-leukemia protective immunity against L1210 cells. DBA/2 mice (n = 10 per group) were subcutaneously pre-injected with PBS, non-pulsed DC (1 × 106/mice), DCLEX (1 × 106/mice), DCLEX-GFP (1 × 106/mice), and DCLEX-TGF-β1si (1 × 106/mice), respectively, for three times each with 3-day interval. On day 7 after last immunization, all mice were challenged with L1210 cells (3 × 105/mice). Tumor growth was monitored daily for up to 24 days. One representative experiment of three is shown

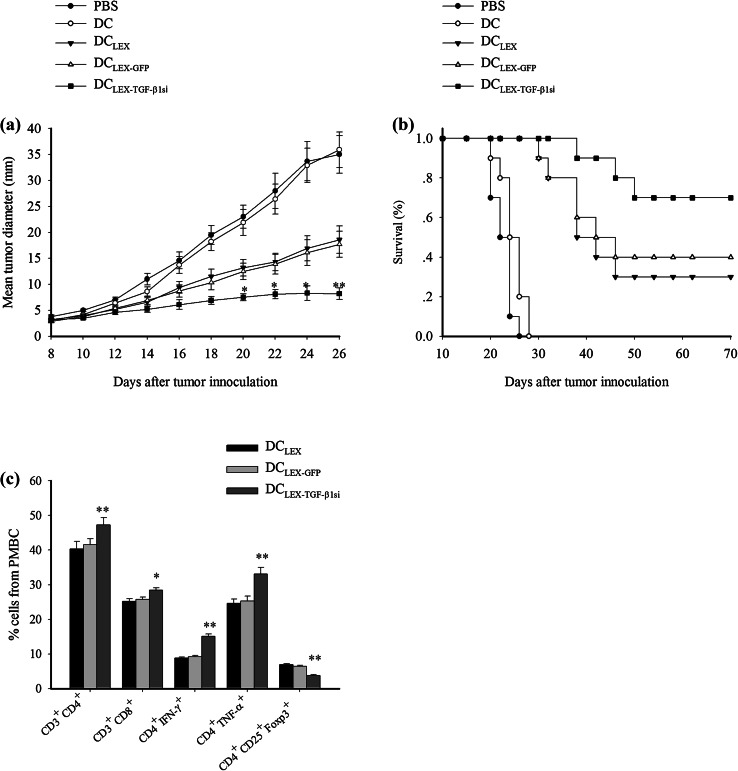

To further investigate whether DCLEX-TGF-β1si can work therapeutically on established tumors as a vaccine approach, we compared the rates of tumor growth and survival of the tumor-bearing mice. As shown in Fig. 4a, compared to effect of PBS or non-pulsed DC injection, DCLEX and DCLEX-GFP vaccination contributed to achieving an improved survival. It is noteworthy that the mice that received DCLEX-TGF-β1si revealed a significant improvement in survival compared with the mice in the control and the remaining DC groups. Meanwhile, the tumor growth was markedly inhibited by exosome-pulsed DC groups compared to the PBS and non-pulsed DC group. Moreover, DCLEX-TGF-β1si immunization exerted the most significant inhibitory effect on tumor growth (Fig. 4b, p < 0.05). Taken together, the data indicated that DCLEX-TGF-β1si induced protective and therapeutic anti-leukemic immunity with higher efficacy compared with the DCLEX and DCLEX-GFP formulations.

Fig. 4.

DCLEX-TGF-β1si immunization induced anti-leukemic therapeutic immunity. DBA/2 mice (n = 10 were inoculated with L1210 leukemia cells (3 × 105/mice) subcutaneously. Following a 7-day period, the tumor became palpable (approximately 3.5 mm in diameter) and the mice received s.c injections of PBS, non-pulsed DC, DCLEX, DCLEX-GFP, and DCLEX-TGF-β1si, respectively, at a density of 1 × 106 cells/mice for three times each at a 3-day interval. The mortality of the mice and the tumor growth or regression were monitored; a survival of pre-immunized DBA/2 mice following tumor inoculation; b tumor growth in pre-immunized mice following tumor inoculation. Tumor size was measured with a caliper every 2 days. c 7 days following immunization, the frequency of T-cell subtype in PBMC was analyzed and results were presented as the mean ± SD

The effect of DCLEX-TGF-β1si on the frequency of T-cell subtypes derived from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in tumor bearing mice following 7 days of vaccination was evaluated. The experiments aimed to further address the superiority of the DCLEX-TGF-β1si vaccination compared with the DCLEX or DCLEX-GFP groups in vivo. As shown in Fig. 4c, mice treated with DCLEX-TGF-β1si exhibited a higher percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells along with fewer regulatory T cells (Tregs) expressing CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+. Moreover, it has been shown that there was a significantly increased frequency of IFN-γ and TNF-α expressing CD4+ T-cells in the mice immunized with DCLEX-TGF-β1si compared with those with DCLEX and DCLEX-GFP, indicating that DCLEX-TGF-β1si can more potently trigger Th1 immune response than DCLEX and DCLEX-GFP in vivo.

Discussion

Tumor-derived exosomes comprise a series of TAA and innate stimulatory molecules that can induce specific antitumor immunity [25]. This property renders TEX as a promising source of tumor vaccines. However, the therapeutic efficacy of TEX-based immunotherapy has not been satisfactory for clinical applications. The majority of the patients who received TEX vaccine achieved no clinical benefit [26]. Therefore, studies should focus on the improvement of the efficacy of the TEX-based vaccine. In the present study, TGF-β1, the most crucial immune-suppressive molecules in TEX, was downregulated in leukemia cell-derived exosomes via a gene modification approach in the parental cells [27, 28]. The results demonstrated that LEXTGF-β1si significantly facilitated the maturation of pulsed DC and downregulated the TGF-β1 secretion from pulsed DC compared with LEXs. Importantly, immunization with DCLEX-TGF-β1si induced a potent specific immunity against leukemic cells with higher efficacy compared with the DCLEX and DCLEX-GFP.

In the current study, silencing TGF-β1 expression of L1210 cells via lentiviral vector-mediated shRNA resulted in effective downregulation of TGF-β1 level on L1210-produced exosomes. This suggested that it was feasible to regulate the protein composition of exosomes via gene modification on parent cells. Previous studies have demonstrated that downregulation of TGF-β1 in the tumor vaccine systems can successfully improve the immunogenicity of vaccines as a result of the effect of TGF-β1 on tumor immunity [29, 30]. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that silencing of TGF-β1 in the TEX-based vaccine may partially block the immunosuppressive effects of TEX on the immune system and enhance the efficacy of the vaccine. Given that TGF-β family plays an important role on the regulation of normal cellular processes, the immunization with LEX-based vaccines combined with an anti-TGF-β antibody which can block the binding of all isoforms of the TGF-β family may influence normal biological processes, causing serious systemic toxicities. Consequently, the strategy for the specific depletion of TGF-β1 in TEX-based vaccines via gene modification in parental cells may be a more appropriate approach.

One of the advantages of DC vaccines is that DC can be activated in vitro distant from the immune-tolerant tumor microenvironment. However, TGF-β1 from TEX may compromise the efficacy of the DC vaccine. A recent study reported that exosomal TGF-β1 induced the suppression of an exosome-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity response in vivo by the downregulation of the expression of MHC class II molecules and the CD86 in DC [22]. In the present study, we found that LEX cannot efficiently induce DC maturation. However, LEXTGF-β1si significantly increased the expression of co-stimulatory factors, MHC-II, IL-12p70, and TNF-α in DC which are required for direct induction of the adaptive immunity, implying that LEXTGF-β1si could partially counteract the inhibitory effect of exosomal TGF-β1 on the maturation of DC. TEX has been reported to predispose DC to acquire a potentially tolerogenic phenotype via the induction of TGF-β1 secretion from DC [22]. Notably, we found that LEXTGF-β1si can effectively inhibit TGF-β1 production in exosome-conditioned DC, suggesting that the immune tolerogenic phenotype of LEX-pulsed DC may be efficiently reversed by downregulation of TGF-β1 at the exosomal level. However, we have not gained a clear idea of how LEXTGF-β1si regulated TGF-β1 secretion from DC and influenced DC’s maturation. Therefore, an in-depth investigation for the exact mechanism is needed in the future. Taken together, silencing of TGF-β1 in LEX has been documented to be an effective approach for facilitating the maturation and immune function of the exosome-pulsed DC. Since DC are proposed to be the professional antigen-presenting cell for the initiation of immune response [31], the differences between LEXTGF-β1si pulsed DC and LEX- and LEX-GFP-pulsed DC may account for the different efficacies with regard to the priming of the tumor-specific T-cell activation.

Internalized TEX in DC were processed partially in MIIC and the exosomal antigens can be presented to CD4+ T-cells, thus resulting in priming of T cells [5, 24]. As a result, during the process of TEX-carried antigen processing and presentation, TGF-β1 in TEX may not only influence the function of DC, but also other immune cells like CD4+ T-cells, CD8+ T-cells, and NK cells. In the present study, we have shown that DCLEX-TGF-β1si effectively facilitated CD4+ T-cell proliferation and enhanced the secretion of Type I cytokines that are crucial for the activation of macrophages and CTL. This observation suggested that the downregulation of TGF-β1 in LEX can successfully induce a specific CD4+ response of greater potency compared with non-manipulated LEX formulations [32]. Furthermore, DCLEX-TGF-β1si induced an antigen-specific CTL response more potently than the other groups examined. The potency of the enhanced CTL activity induced by DCLEX-TGF-β1si may be an indirect result of increased Type I cytokine production. The superiority of DCLEX-TGF-β1si in inducing anti-tumor immunity was further evaluated in DBA/2 mice. Our data demonstrated that DCLEX-TGF-β1si significantly reinforced antitumor efficacy and resulted in the greatest prolongation of the survival time of immunized mice as well as the most effective retardation of tumor growth in both preventive and therapeutic models. The retardation of tumor growth in vivo may be associated with the expansion of the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, the decreased frequency of the Treg cells, and the highly potent tumor-specific Th1 response.

In summary, the present study provides evidence that DC pulsed with LEXTGF-β1si induced an anti-leukemic immunity of greater potency compared with DC pulsed with LEX. It is speculated that the immunogenicity of TEX-based vaccines may be further improved by the downregulation of other immunosuppressive molecules, such as Fas ligand and IL-10 and the upregulation of immune-stimulatory factors including CD80 and CD86. However, additional studies with regard to the retardation of tumor growth in animals are required in order to achieve a satisfactory therapeutic effect against tumors in patients. Consequently, considerable efforts should be made to optimize TEX-based vaccines in future clinical trials.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81470314).

Abbreviations

- CTL

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes

- DC

Dendritic cells

- DCLEX

Dendritic cells pulsed with exosomes from non-manipulated L1210 cells

- DCLEX-GFP

Dendritic cells pulsed with exosomes from L1210 cells transfected with a control shRNA

- DCLEX-TGF-β1si

Dendritic cells pulsed with exosomes from the TGF-β1 silenced L1210 cells

- HSP

Heat shock protein

- IFN-γ

Interferon-γ

- IL

Interleukin

- LEX

Exosomes from non-manipulated L1210 cells

- LEXGFP

Exosomes from L1210 cells transfected with a control shRNA sequence

- LEXTGF-β1si

Exosomes from the TGF-β1-silenced L1210 cells

- MRLs

Minimal residual leukemia cells

- NK

Natural killer

- TAA

Tumor-associated antigens

- TEX

Tumor-derived exosome(s)

- TGF-β1

Transforming growth factor-β1

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-α

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Fang Huang and Jiangbo Wan have contributed equally.

References

- 1.Chen X, Xie H, Wood BL, Walter RB, Pagel JM, Becker PS, Sandhu VK, Abkowitz JL, Appelbaum FR, Estey EH. Relation of clinical response and minimal residual disease and their prognostic impact on outcome in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(11):1258–1264. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibbins JD, Ancelet LR, Weinkove R, Compton BJ, Painter GF, Petersen TR, Hermans IF. An autologous leukemia cell vaccine prevents murine acute leukemia relapse after cytarabine treatment. Blood. 2014;124(19):2953–2963. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-568956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maeda T, Hosen N, Fukushima K, Tsuboi A, Morimoto S, Matsui T, Sata H, Fujita J, Hasegawa K, Nishida S, Nakata J, Nakae Y, Takashima S, Nakajima H, Fujiki F, Tatsumi N, Kondo T, Hino M, Oji Y, Oka Y, Kanakura Y, Kumanogoh A, Sugiyama H. Maintenance of complete remission after allogeneic stem cell transplantation in leukemia patients treated with Wilms tumor 1 peptide vaccine. Blood Cancer J. 2013;3:e130. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2013.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao Y, Wang C, Wei W, Shen C, Deng X, Chen L, Ma L, Hao S. Dendritic cells pulsed with leukemia cell-derived exosomes more efficiently induce antileukemic immunities. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e91463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gu X, Erb U, Buchler MW, Zoller M. Improved vaccine efficacy of tumor exosome compared to tumor lysate loaded dendritic cells in mice. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(4):E74–E84. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arscott WT, Camphausen KA. Exosome characterization from ascitic fluid holds promise for identifying markers of colorectal cancer. Biomark Med. 2011;5(6):821–822. doi: 10.2217/bmm.11.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petersen KE, Manangon E, Hood JL, Wickline SA, Fernandez DP, Johnson WP, Gale BK. A review of exosome separation techniques and characterization of B16-F10 mouse melanoma exosomes with AF4-UV-MALS-DLS-TEM. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2014;406(30):7855–7866. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-8040-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zech D, Rana S, Buchler MW, Zoller M. Tumor-exosomes and leukocyte activation: an ambivalent crosstalk. Cell Commun Signal. 2012;10(1):37. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-10-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rountree RB, Mandl SJ, Nachtwey JM, Dalpozzo K, Do L, Lombardo JR, Schoonmaker PL, Brinkmann K, Dirmeier U, Laus R, Delcayre A. Exosome targeting of tumor antigens expressed by cancer vaccines can improve antigen immunogenicity and therapeutic efficacy. Cancer Res. 2011;71(15):5235–5244. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andre F, Schartz NE, Chaput N, Flament C, Raposo G, Amigorena S, Angevin E, Zitvogel L. Tumor-derived exosomes: a new source of tumor rejection antigens. Vaccine. 2002;20(Suppl 4):A28–A31. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nanjundappa RH, Wang R, Xie Y, Umeshappa CS, Chibbar R, Wei Y, Liu Q, Xiang J. GP120-specific exosome-targeted T cell-based vaccine capable of stimulating DC-and CD4(+) T-independent CTL responses. Vaccine. 2011;29(19):3538–3547. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rao Q, Zuo B, Lu Z, Gao X, You A, Wu C, Du Z, Yin H. Tumor-derived exosomes elicit tumor suppression in murine hepatocellular carcinoma models and humans in vitro. Hepatology. 2016;64(2):456–472. doi: 10.1002/hep.28549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wieckowski EU, Visus C, Szajnik M, Szczepanski MJ, Storkus WJ, Whiteside TL. Tumor-derived microvesicles promote regulatory T cell expansion and induce apoptosis in tumor-reactive activated CD8+ T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2009;183(6):3720–3730. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamada N, Kuranaga Y, Kumazaki M, Shinohara H, Taniguchi K, Akao Y. Colorectal cancer cell-derived extracellular vesicles induce phenotypic alteration of T cells into tumor-growth supporting cells with transforming growth factor-beta1-mediated suppression. Oncotarget. 2016;7(19):27033–27043. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li W, Mu D, Tian F, Hu Y, Jiang T, Han Y, Chen J, Han G, Li X. Exosomes derived from Rab27a-overexpressing tumor cells elicit efficient induction of antitumor immunity. Mol Med Rep. 2013;8(6):1876–1882. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y, Xiu F, Cai Z, Wang J, Wang Q, Fu Y, Cao X. Increased induction of antitumor response by exosomes derived from interleukin-2 gene-modified tumor cells. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2007;133(6):389–399. doi: 10.1007/s00432-006-0184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dai S, Zhou X, Wang B, Wang Q, Fu Y, Chen T, Wan T, Yu Y, Cao X. Enhanced induction of dendritic cell maturation and HLA-A*0201-restricted CEA-specific CD8(+) CTL response by exosomes derived from IL-18 gene-modified CEA-positive tumor cells. J Mol Med (Berl) 2006;84(12):1067–1076. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0102-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J, Wang L, Lin Z, Tao L, Chen M. More efficient induction of antitumor T cell immunity by exosomes from CD40L gene-modified lung tumor cells. Mol Med Rep. 2014;9(1):125–131. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan W, Tian XD, Huang E, Zhang JJ. Exosomes from CIITA-transfected CT26 cells enhance anti- tumor effects. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(2):987–991. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.2.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hao S, Bai O, Li F, Yuan J, Laferte S, Xiang J. Mature dendritic cells pulsed with exosomes stimulate efficient cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses and antitumour immunity. Immunology. 2007;120(1):90–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02483.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong CS, Muller L, Whiteside TL, Boyiadzis M. Plasma exosomes as markers of therapeutic response in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Front Immunol. 2014;5:160. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang C, Kim SH, Bianco NR, Robbins PD. Tumor-derived exosomes confer antigen-specific immunosuppression in a murine delayed-type hypersensitivity model. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e22517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lv LH, Wan YL, Lin Y, Zhang W, Yang M, Li GL, Lin HM, Shang CZ, Chen YJ, Min J. Anticancer drugs cause release of exosomes with heat shock proteins from human hepatocellular carcinoma cells that elicit effective natural killer cell antitumor responses in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(19):15874–15885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.340588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morelli AE, Larregina AT, Shufesky WJ, Sullivan ML, Stolz DB, Papworth GD, Zahorchak AF, Logar AJ, Wang Z, Watkins SC, Falo LD, Jr, Thomson AW. Endocytosis, intracellular sorting, and processing of exosomes by dendritic cells. Blood. 2004;104(10):3257–3266. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kunigelis KE, Graner MW. The dichotomy of tumor exosomes (TEX) in cancer immunity: is it all in the ConTEXt? Vaccines (Basel) 2015;3(4):1019–1051. doi: 10.3390/vaccines3041019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dai S, Wei D, Wu Z, Zhou X, Wei X, Huang H, Li G. Phase I clinical trial of autologous ascites-derived exosomes combined with GM-CSF for colorectal cancer. Mol Ther. 2008;16(4):782–790. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rong L, Li R, Li S, Luo R. Immunosuppression of breast cancer cells mediated by transforming growth factor-beta in exosomes from cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2016;11(1):500–504. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raimondo S, Saieva L, Corrado C, Fontana S, Flugy A, Rizzo A, De Leo G, Alessandro R. Chronic myeloid leukemia-derived exosomes promote tumor growth through an autocrine mechanism. Cell Commun Signal. 2015;13:8. doi: 10.1186/s12964-015-0086-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soares KC, Rucki AA, Kim V, Foley K, Solt S, Wolfgang CL, Jaffee EM, Zheng L. TGF-beta blockade depletes T regulatory cells from metastatic pancreatic tumors in a vaccine dependent manner. Oncotarget. 2015;6(40):43005–43015. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conroy H, Galvin KC, Higgins SC, Mills KH. Gene silencing of TGF-beta1 enhances antitumor immunity induced with a dendritic cell vaccine by reducing tumor-associated regulatory T cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61(3):425–431. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1188-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Volovitz I, Melzer S, Amar S, Bocsi J, Bloch M, Efroni S, Ram Z, Tarnok A. Dendritic cells in the context of human tumors: biology and experimental tools. Int Rev Immunol. 2016;35(2):116–135. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2015.1096935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lucey DR, Clerici M, Shearer GM. Type 1 and type 2 cytokine dysregulation in human infectious, neoplastic, and inflammatory diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9(4):532–562. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.4.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]