Abstract

Monoclonal antibodies have been extensively used to treat malignancy along with routine chemotherapeutic drugs. Chemotherapy for metastatic cancer has not been successful in securing long-term remission of disease. This is in part due to the resistance of cancer cells to drugs. One aspect of the drug resistance is the inability of conventional drugs to eliminate cancer stem cells (CSCs) which often constitute less than 1–2% of the whole tumor. In some tumor types, it is possible to identify these cells using surface markers. Monoclonal antibodies targeting these CSCs are an attractive option for a new therapeutic approach. Although administering antibodies has not been effective, when combined with chemotherapy they have proved synergistic. This review highlights the potential of improving treatment efficacy using functional antibodies against CSCs, which could be combined with chemotherapy in the future.

Keywords: Monoclonal antibodies, Cancer stem cells, Targeted therapy, Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity

Introduction

It has been increasingly apparent in the past two decades that targeting cancer using antibodies in combination with chemotherapy is a clinically and commercially useful approach to provide long-term cure [1, 2]. Emerging evidence proving the relevance of the cancer stem cell theory has helped in developing novel approaches that can specifically target cancer stem cells (CSCs) or tumor-initiating cells, hence preventing recurrence and metastasis. Intense research is being performed to identify and target CSCs, as they represent a small subpopulation of cells responsible for driving tumorigenesis. Using antibodies to target this subpopulation of cells represents a promising approach.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs)

Over the past decade, the CSC hypothesis has become increasingly evident, suggesting the presence of a small population of quiescent or slowly dividing cells that contributes to the initiation and recurrence of cancer. It was shown convincingly in leukemia that a small population of CD34+/CD38− cells drives the disease [3]. Similarly in colon, brain, breast and pancreatic cancer, CSCs express a particular set of markers which helps in the identification of this rare population of cells [4–7]. Recent reports also suggest that the origin of CSC may be from a normal stem cell or dedifferentiation of a non-committed progenitor cell. Non-CSCs can switch to a stem cell state, depending on the activity of zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox1 (ZEB1) promoter [8]. A caveat is that, many of the surface markers are probably expressed developmentally and not exclusive to CSCs.

The specificity of these surface markers used for identifying CSCs is still being debated. For example, CD133 negative cells from glioma are tumorigenic in immunocompromised mice [9]. Thus, it may be relevant to consider a group of markers rather than a single one that can distinguish CSCs from the remaining heterogeneous mass of malignant cells. This is analogous to diagnostic immunophenotyping of leukemia, where the holy grail of identifying specific markers has finally led only to a panel to subtype leukemia. All such CD antigens are present in normal hematopoietic cells at different stages. Therefore, identifying these cells based on one or two surface antigens may not be the right strategy as cancer stemness is a property which can have variable expression rather than a strictly demarcated and committed state with mandatory expression of defined markers. Despite the ongoing debate on the existence of CSCs and their identification, there is sufficient evidence in some tumor types to explore the approach of targeting surface markers.

Stem cells possess certain intrinsic properties which distinguish them from the rest of the differentiated cells in the tumor. Self-renewal helps in maintaining the stem cell number and supports the growth of tumors. Single cell colony assay and spheroid formation suggest the presence of CSCs in melanoma cell lines [10]. Functional assays, such as those that detect side population cells or aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDEFLUORTM) can prove to be better techniques [11–18]. Functional assays together with the expression of surface markers may be a more successful approach in identifying CSCs. Further, it has been shown recently that it is possible to identify CSCs using reporter constructs that detect expression of stem cell transcription factors [19].

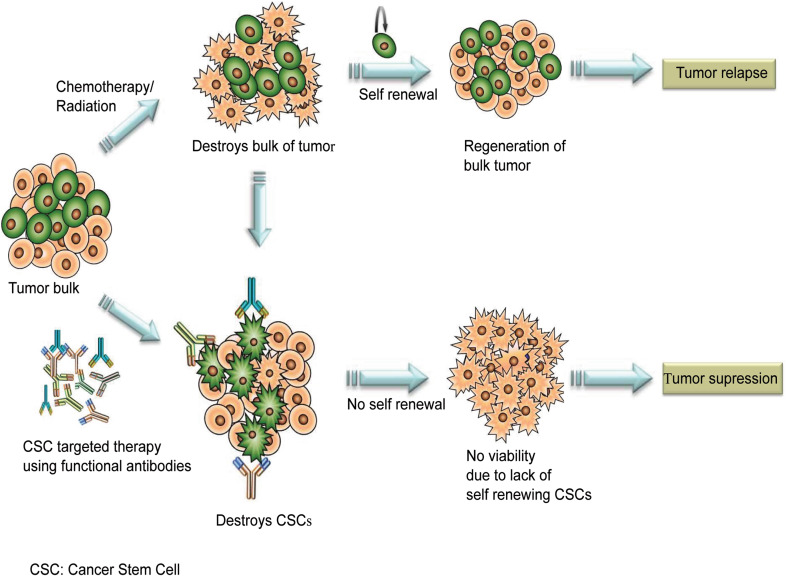

Monoclonal antibodies have been increasingly used to target malignant cells in many cancers. However, most of these antibodies are not necessarily curative, when used alone. This is largely due to: (1) the heterogeneous nature of the tumor mass; (2) the evasion of CSCs from the treatment strategies employed; and (3) insufficient therapeutic delivery, which contribute to treatment failure and relapse. Hence, the major shortcoming of this approach is that most of these mAbs therapies are unlikely to target CSCs. So the question is, “Are we hitting the right targets?” (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Targeting cancer stem cells using antibodies. Treatment of cancer with standard chemotherapeutic drugs or radiation eliminates the bulk of tumor leaving behind cancer stem cells. These cells are responsible for tumor recurrence. Combining monoclonal antibodies with chemotherapy could improve the outcome of cancer therapy

CSCs could be an alternative target for antibody-based approaches. Therefore, an mAb-based strategy targeting CSCs, along with other chemotherapeutic drugs for the bulk of tumor cells, might be the best possible way to improve the outcome. Nevertheless, this approach is limited by factors such as small number of CSCs and variability in surface markers expressed by these cells, which can also be shared along with other normal and non-cancerous stem cells [1]. The potential presence of CSCs residing in hypoxic compartments distant from existing blood vascular networks is also likely to diminish the efficacy of selective mAbs [20]. Further, a better understanding of the key factors and pathways that maintain CSCs are also essential.

Recently, it has been shown that gene expression of CSCs correlated with the clinical outcome of the disease. In leukemia, the shared expression of stem cell-specific genes like MECOM, ME1S1, HOXB3 and ERG between hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) and leukemia stem cell (LSC) correlated with poor prognosis. This firm relation in transcriptional signatures of HSCs and LSCs not only reaffirms the hierarchical arrangement of AML explained by the CSC model but also allows us to explore the possibility of achieving a better survival outcome by targeting clinically significant LSCs [21]. Similarly, in colorectal cancer (CRC), an intestinal stem cell (ISC) signature with high expression of EphB2 was found to correlate strongly with recurrence and long-term survival. An ISC-like gene program expressed in colorectal cancer was directly related to the outcome of patients. This program defined a cancer stem cell niche in CRC, responsible for relapse [22].

Monoclonal antibodies

The past two decades have witnessed a huge amount of research in mAb-based treatment strategy for solid tumors and hematological malignancies (Fig. 1). Initially, this mode of therapy was given to a patient suffering from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Serotherapy of a patient with mAb Ab89 against the human lymphoma-associated antigen reacted only with the lymphoma cells through complement-mediated lysis and macrophage adherence [23].

Efficacy and outcome of a potent mAb are essentially based on the selection of target antigen, which should portray certain basic characteristics like abundancy, accessibility, the consistent homogenous expression on the cell surface and minimal secretion [24]. The development of specific antibodies has improved considerably since their original discovery. It is now possible to produce single-chain (sFv), divalent and single-domain antibodies (dAB) which are smaller and effective [25–27]

Chimeric and humanized antibodies

Human Immunoglobulin G (IgG) stitched with murine variable domains reinforces the concept of therapeutic antibodies [28]. As the variable domains of the antibody, heavy chain and light chain are responsible for the specificity and binding of the antibody, chimeric antibodies, being 70% human are less immunogenic and more effective. Furthermore, complementarity determining region (CDR) grafting has made it also possible to fuse the hypervariable loops of the murine antibody with fully human IgG, paving the way for 90% humanized antibodies with increased efficacy [29]. The drawback of this method is that it is technically challenging than ordinary fusion antibodies and the affinity of the parental murine antibody has to be verified by methodologies like side-directed mutagenesis. Techniques like phage display and ribosome display have made it possible for antibodies to bind targets with affinities nearer to sub-picomolar levels [30] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mode of action of monoclonal antibodies. Monoclonal antibodies specifically target CSCs by binding to the surface antigens expressed on CSCs and further destroy the cell through antibody-mediated cellular cytotoxicity, complement-mediated cytotoxicity and apoptosis. They can also prevent the receptor from binding to the ligand and prevent dimerization. The non-stem tumor cells will be eliminated by the standard chemotherapeutic drug treatment or radiation therapy

Developing ‘humanized’ mice is an alternative approach which provides fully human in vivo matured antibodies, as the entire IgG repertoire of the mouse is replaced with human. But problems like inability to use a toxic immunogen or immunogen having a striking similarity to its mouse ortholog limited the popularity of this technique [31] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Origin of cancer stem cells and the evolution of monoclonal antibodies. A cancer stem cell can originate from a stem, progenitor or a differentiated cell. Fully human and humanized antibodies have a reduced possibility for generating immune response compared to murine and chimeric antibodies

Functional antibodies

These antibodies by themselves have a lethal effect on cancer cells. Rather than being conjugated to a toxoid or radioactive element, these antibodies act by neutralizing the target or inhibiting the function of the target. An overexpressed proto-oncogene, for example, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) in breast cancer has paved the way for the development of specific humanized monoclonal antibody trastuzumab (trade name Herceptin) (Rhu-mAb-HER2), effective in treating metastatic breast cancer [32, 33]. Together with other treatment modalities like chemotherapy, administration of trastuzumab has been shown to improve the response rate, the median duration of response and time to progression when compared to chemotherapy alone [33]. Similarly, follicular, relapsed or refractory low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) is being treated with the anti-CD20 antibody (Rituximab), which has proved to have potential anti-tumor activity. These antibodies generally act through mechanisms such as complement-mediated toxicity (CDC), antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) or by enhanced apoptosis (Fig. 2). However, it is unclear if the antibody is intervening with a functional attribute of CD20 surface antigen by regulating/blocking calcium efflux or giving rise to a cell death signal by phosphorylating a tyrosine residue of Src family tyrosine kinases tightly associated with CD20 [34, 35]. All these antibodies are most effective when used in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs.

Antibody cocktails and bispecific mAbs

Antibody cocktails contain a mixture of antibodies that can act synergistically with optimal efficacy incorporating the technological advances that have come up in the field of antibody engineering [36]. Such a combination of antibodies could increase the number of mechanisms as well as its complexity in recruiting the effector functions. Targeting a single growth-factor receptor on a cell using a specific mAb could lead to an off target compensatory increase in another growth-factor receptor, whereas dual blocking of both might be a better alternative. Moreover, by targeting a group of surface markers or molecules that are exclusively present on CSCs using antibody cocktails, it would be possible to leave the non CSCs unharmed, thus enhancing the functional specificity of antibody therapy [36]. In addition, bispecific antibodies that can simultaneously bind to two molecular targets are an equally attractive concept.

Monoclonal antibody targeting of CSCs

A distinct set of markers that can absolutely define CSCs can allow specific targeting of these cells thereby eliminating them exclusively and protecting the normal healthy cells. The optimal target antigen for a mAb would be a surface molecule highly expressed on cancer stem cells but absent or present at a lower level in normal non-cancerous cells. Several studies have prospectively isolated CSCs by analyzing for the presence of surface markers that are thought to be stem cell specific. However, none of these cell surface antigens are exclusively present on CSCs and there is lineage infidelity. Despite this drawback, antibodies offer a new approach to target CSC [37, 38] (Table 1). Surface antigens that have been found to mark CSCs consistently in various tumors are potential targets and are discussed below. Two such cell surface antigens are CD44 and CD133. Although these antigens are expressed at low levels in normal tissues and are not exclusively expressed on CSCs within a tumor yet antibodies are being developed to target them. CD44 has been defined as a CSC marker in many tumors and has biological functions that may be of value to CSCs.

Table 1.

Summary of functional monoclonal antibodies

| S. no. | Surface marker/target | Functional MAb | Cancer | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CD44 | H90 | AML | Reduction of leukemic burden in NOD-SCID mice transplanted with primary AML cells | [39] |

| A3D8 + H90 | AML | Abrogates proliferation of AML cell lines | [40, 41] | ||

| IM-7* | AML | Impairs adhesion and migration capabilities of LSCs | [42] | ||

| RG7356 | CLL | Induces malignant cells to go through caspase-dependent apoptosis | [43] | ||

| P245 | Breast | Anti-proliferative effect due to the release of cytokines (IL-1, TGF-1, OSM and TGF-) | [44] | ||

| H4C4* | Pancreas | Reduces tumor growth, metastasis and recurrence along with inhibiting the self-renewing capability of pancreatic CSCs | [45] | ||

| GV5* | Exclusively eliminates the stem cell compartment | [46] | |||

| A3D8* | Ovarian | Attenuate formation of spheroids | [47] | ||

| R05429083 | Head and neck cancer | Inhibition of tumor growth in vivo | [48] | ||

| GKW.A3 | Melanoma | Completely inhibits the binding of hyaluronic acid to tumor cells | [49] | ||

| 2 | CD133 | 6B6 | Colorectal | Inhibits the proliferation of colorectal cell line | [55] |

| 3 | CD24 | Colorectal | Reduces tumor burden | [61] | |

| 4 | CD9 | ALB6 | Gastric | Reduces tumor volume and tumor micro vessel density | [69] |

| AR40A746.2.3* | Breast, Pancreas and AML | Inhibits growth of tumor and AML stem cells | [71] | ||

| 5 | CD326/EpCAM | EdrecolomAb | Colon | Approved for use as adjuvant monotherapy due to its ability to improve overall, disease-free survival | [76] |

| ING-1 (hemAb) | Colon, Prostate | Suppression of tumor growth | [77] | ||

| 6 | CD123 | 7G3* | AML | Inhibits homing of AML-LSCS | [82, 83] |

| CSL362 + TKI (tyrosine kinase inhibitors) | Eliminates selectively the progenitor cells over normal stem cell compartment | [84] | |||

| 7 | CD47 | AML, ALL | Causes engulfment of LSCS by macrophages | [93, 94] | |

| B6H12* | Multiple myeloma, Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and solid tumors | Phagocytosis of malignant cells with growth inhibition | [13, 92, 96] | ||

| Leiomyosarcoma | Eliminates metastatic disease | [97] |

* Proven stem cell specificity

CD44 (Indian blood group antigen)

The use of functional antibodies was first demonstrated in leukemia when antibodies against CD44 were used to selectively induce differentiation or inhibit proliferation to eradicate LSCs [39]. CD44 is a cell surface protein believed to play a decisive role in adhesion and migration. Manipulation of CD44 function with mAb H90 showed a marked reduction of leukemic burden in NOD-SCID mice transplanted with primary AML cells. The mode of action of mAb H90 was defined by the alteration of leukemic stem cell fate and abrogation of AML LSC homing [39]. Thus, it was possible to target AML leukemic stem cells focusing on stem cell properties rather than proliferation. Similarly, H90, when given along with another CD44-specific mAb A3D8, showed inhibition of proliferation of all AML cell lines studied (THP-1, HL60, and NB4), induced terminal differentiation and caused cell death by apoptosis [40, 41]. Thus, the block in differentiation of leukemia could be reversed and provides a new basis for differentiation therapy. Targeted therapy of CML-LSCs by mAb IM-7 against CD44 resulted in the blockage of adhesion and migration capabilities of LSCs in vitro. Studies such as MTT assay and transendothelial migration assay were performed, but there was no evidence provided in vivo [42]. In CLL, antiCD44 antibody (RG7356) eliminated ZAP-70pos cancer cells by inhibiting their growth/survival signaling and inducing them to go through caspase-dependent apoptosis. R7356 further caused internalization of CD44-ZAP70 complex reducing B cell receptor (BCR) signaling [43].

In breast cancer, tumor growth inhibition and reduced recurrence following chemotherapy were observed after treatment with an antiCD44 antibody P245 [44]. Failure of exogenously administered hyaluronan (HA) in significantly decreasing recurrence proved that P245 MAb does not prevent binding of CD44 to its ligand. The anti-proliferative effect was mainly due to the release of cytokines (IL-1 , TGF-1, OSM and TGF-α), as a result of P245 treatment. CD44, an independent poor prognostic factor for survival in pancreatic cancer, was targeted using antihuman mouse IgG1 anti hyaluronate receptor antibody, H4C4. Treatment with the antibody significantly reduced tumor growth, metastasis and recurrence following radiation. In addition, to the bulk proliferating tumor mass, the action of the antibody was found to be specifically inhibiting the self-renewing capability of pancreatic CSCs [45]. In an attempt to target only CSCs, a fully human CD44 antibody (GV5) was prepared, specific to the splice variant protein CD44v (CD44R1), which exclusively eliminated the stem cell compartment by inhibiting tumor formation and growth of cancer cells in athymic mice [46]. In ovarian cancer, mAb A3D8, along with cisplatin, has shown to target CSCs as it could attenuate formation of spheroids from cells obtained from malignant ascites samples. The treatment increased levels of caspase-3 while downregulating CDK7, cyclin A and Bcl2 genes [47]. A functional antibody R05429083 targeting CD44 also demonstrated significant inhibition of tumor growth in HNSCC cell line (CAL 27) xenografts in nude mice, compared to cisplatin. This effect was attributed to decreased EGFR signaling and expansion of NK cells [48]. The role of CD44 in tumor and metastasis studied in melanoma cell lines (SMMU-1, SMMU-2) disclosed the significance of its function when blocked with a mAb GKW.A3 (Mouse IgG2a) that completely inhibited the binding of hyaluronic acid to SMMU-2 tumor cells in vitro [49]. Growth and metastatic potential of SMMU-2 tumor cells were inhibited after administration of GKW.A3. When the mAb was administered a week later after tumor injection, it prolonged animal survival and prevented the formation of metastatic tumors, although the development of local tumors could not be inhibited. In cynomolgus monkeys, CD44 positive adenocarcinomas were observed to be inhibited by administration of mAb huARH460 with no limiting toxicity at therapeutically applicable doses. Thus, CD44 promises to be an excellent target for the development of antibodies. However, there are different splice variants of CD44 and their individual role is still not completely understood [50]. This will prove to be a challenge when developing antibodies to target CSCs.

CD133 (Prominin 1)

CD133 is a well-known CSC biomarker coding a five span transmembrane protein of 120KDa [51]. Although CD133 is mainly associated with CD34 positive hematopoietic cells, it is also a potent CSC marker in different tumors. Initially in lung cancer, CD133 positive cells were shown to have a long-term tumorigenic potential, producing secondary tumors on serial xenotransplantation, in contrast to the negative population [52]. Similarly in glioma multiforme, CD133 positive cells were identified as brain tumor-initiating cells [5]. CD133 is considered as one of the most potent markers to identify and characterize colon cancer stem cells. While CD133 was shown to be a prognostic marker coincidental with poor survival in colorectal cancer, CSCs with CD133 CXCR4− phenotype were also shown to be related to metastasis [53, 54]. CD133 positive cell line Y79 was injected into balb/c mice to generate a functional anti-human murine mAb (clone 6B6), which inhibited the growth of a colorectal cell line Caco-2, detected by decreased cell number and MTT assay [55]. Flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry and immunophenotyping identified the surface expression of CD133 on several cell lines with mAb 6B6 along with tumor samples from 11 patients with CRC. But no in vivo experiments have been performed to prove the efficacy of this antibody in functionally blocking CD133. A deimmunized bispecific targeted toxin against two CSC markers CD133 and EpCAM (dEpCAMCD133KDEL) regressed tumor in an in vivo mouse model of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) while inhibiting spheroid formation, protein translation and cellular proliferation in vitro in other cancers [56]. Furthermore, in glioblastoma, a bispecific antibody targeting CD133 and EGFRvIII selectively eliminated CSCs. Further, the antibody significantly reduced tumourigenicity and increased survival of mice [57]. However, as an alternative to combining two CSC-specific markers, a component of cellular immunity could be armed with an antibody against a known marker. This type of bispecific antibody-cytokine- induced killer (BsAb-CIK) cell has been shown to selectively inhibit CSCs and prevent tumor growth in vivo [1].

CD24 (small-cell lung carcinoma cluster 4 antigen)

CD24, a potent oncogene overexpressed in various human malignancies codes for a 31 amino acid highly glycosylated protein anchored by glycosylphosphtidylinositol. Its expression in cancer is correlated with poor prognosis. This membrane-attached heat stable antigen plays a major role in selection and maturation during hematopoiesis as well as in cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions [58]. In cancers, CD24 overexpression is associated with cell adhesion and metastasis, leading to progression of the tumor. Functionally, being an alternative ligand for p-selectin, it helps in the metastatic shedding of tumor cells in the bloodstream [59]. This property of promoting metastasis enhances the possibility of CD24 as a potential CSC marker and its expression in tumors as a prognostic factor for outcome. In pancreatic cancer, CD24 has been identified as a potent CSC marker along with CD44 and epithelial specific antigen (ESA) as the population expressing all the three markers was found to be highly tumorigenic and retained the stem cell property of self-renewal [7]. Moreover, in ovarian cancer CD24+ cells were shown to be tumorigenic compared to the CD24− population and were also enriched in stemness-related genes like Nestin, Bmi-1, Beta catenin, Oct3/4, notch1, notch4 [60]. In colorectal cancers, where CD24 is expressed in 90% of cases, it was shown that down-regulation of the gene can decrease cancer cell tumourigenicity. Down regulation was done by two different approaches, i.e., blocking its expression using small interfering RNA (SiRNA) and a specific mAb (SWA11). Both methodologies augmented growth inhibition and lead to a less severe malignant phenotype. Both approaches were proven to be equally effective in decreasing tumor burden in vivo when human cancer cell lines were injected into athymic nude mice. Gene expression studies revealed that both approaches that inhibited CD24 targeted the same set of genes and pathways including genes of the Bcl-2 pathway, p21and CD27 [61].

CD9 (motility-related protein-1)

CD9, a 24-KDa member of the tetraspanin superfamily, is a putative CSC marker as well as a known marker of myeloblasts and myeloid cells [62]. It plays a vital role in regulating cellular activities like cell motility, adhesion, proliferation and fusion. While an enduring ambiguity exists with regard to the role played by CD9 in tumorigenesis, it represents a putative CSC-specific therapeutic target in various cancers including gastric, pancreatic, breast, colon and ovarian carcinomas [63–67] CD9 expression is found to be high in gastrointestinal carcinomas and is correlated with metastasis [68]. In gastric cancers, antiproliferative, proapoptotic and antiangiogenetic effects were observed when treated with an anti-CD9 antibody [69]. Tumor volume was found to be significantly reduced in the treatment group administered with ALB6 mAb as compared to normal IgG when human gastric cell line MKN-28 was injected subcutaneously into the dorsal region of SCID mouse. The antibody-treated group also revealed a significant reduction in tumor microvessel density indicating the effect of ALB6 on modulation of vascular epidermal growth factor (VEGF-A) as previously reported [70].

The ARIUS Function First anti-cancer antibody discovery platform has come up with a novel anti-CD9 antibody AR40A746.2.3, which inhibits tumor growth in human pancreatic and breast cancer. Reduction in tumor growth (70–100%) was observed in both prophylactic and an established BxPC-3 model of pancreatic cancer. The antibody also recognized CD9 expression on CD34+ CD38− leukemic cancer stem cells and inhibited growth of AML stem cells (CD44+ CD38− CD9+) in primary and secondary xenotransplantation assays [71].

CD326/EpCAM (epithelial cell adhesion molecule)

Although discovered 30 years back as a dominant antigen on colon cancer cells, EpCAM is recently known as a highly expressed surface antigen on CSCs. While sequestered in tight junctions on normal epithelia, it is found widely distributed on cancer cells thereby allowing the binding of specific antibodies. A 26-amino acid intracellular domain of EpCAM, EpIC, provides wnt-like signals in normal cells as well as CSCs, thereby helping them to maintain their vital property of stemness via self-renewal [72]. In hepatocellular carcinoma, EpCAM positive cell population isolated by flow cytometry was found to have stem cell specific properties like self-renewal and pluripotency and proved to be tumorigenic when injected into non-obese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD-SCID) mice [73]. High levels of EpCAM expression was also found in various other carcinomas including retinoblastoma (Rb) and colon cancer [74, 75]. A chimeric murine anti-EpCAM antibody, EdrecolomAb, approved and used in Germany as adjuvant monotherapy for colon cancer showed improvement in overall, disease-free survival and minimal residual disease [76]. A human-engineered monoclonal antibody ING-1 (hemAb) when given intravenously twice a week for three weeks to nude mice, showed significant suppression of growth for human HT-29 colon and PC-3 prostate cells in a dose-dependent manner [77]. AdecatumumAb (MT201), a fully human, recombinant anti-EpCAM mAb, was found to be highly effective against EpCAM positive ovarian cancers [78, 79]. All these antibodies inhibited cell growth using mechanisms like ADCC/CDC unlike abrogating a functional attribute.

CD123 (interleukin-3 receptor, alpha)

Alpha subunit of IL-3R, CD123 (IL-3Rα) receptor is expressed abundantly on the cell surface of CD34+ CD38− LSCs, AML blasts and CD34+ leukemic progenitors, but not on HSCs. When bound to IL3, IL3-R drives cell proliferation and survival [80, 81]. IL-3 neutralizing antibody, 7G3 impaired homing of AML-LSCs and also improved survival in mice [82, 83]. Administration of 7G3 antibody resulted in reduced AML tumor engraftment compared with normal HSCs. Further, marked impairment in repopulation of secondary recipients was observed. 7G3 worked as an antibody with dual effects of blocking as well as mediating ADCC by effector cells. The Fc portion was found to be critical for the activity of the antibody. But the efficacy of the antibody was observed to be decreased when given at a later stage where the leukemic burden was high [82]. Humanized anti-CD123 mAb CSL362 induced ADCC-mediated lysis of leukemic stem cells and inhibited tumor growth in vivo. Combining tyrosine kinase inhibitors with CSL362 selectively eliminated the progenitor cells over normal stem cell compartment. The antibody effectively targeted LSCs by NK-stimulated lysis of the CD34+/CD38− population, while neutralizing IL-3 mediated rescue of the cytocidal effect of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (Nilotinib) [84].

CD47 (integrin associated protein)

CD47, a widely expressed transmembrane protein, is reported as one of the markers which is differentially expressed on LSCs when compared to normal HSCs on the basis of microarray gene expression studies [85, 86]. Phagocytic cells like macrophages and dendritic cells express a protein known as signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) which is recognized by CD47. This leads to the activation of CD47 which then initiates a signal transduction pathway that prevents phagocytosis [86–90]. It was initially observed that on mobilization, the expression of CD47 increases on mouse HSCs which helps in engraftment after transplantation. It was then observed that the increased expression of CD47 on LSCs supported these cells in evading phagocytosis thereby influencing pathogenesis and clinical outcome [91, 92]. MAbs directed against CD47 inhibited the binding of CD47 with SRPα causing the LSCs to be eaten up by macrophages. This was possible due to the selective overexpression of CD47 on LSCs than HSCs. This engulfment of LSCs by macrophages was not a result of the apoptotic death of LSCs, as annexin V staining was found to be negative when the cells were incubated with mAbs in vitro. When injected in newborn NOG mice, LSCs treated with CD47 mAb showed no visible tumor formation after 2 weeks compared to the IgG control, which revealed the disruption of ‘do not eat me’ signal by LSCs. A significant decrease in leukemic burden was also observed when the cells were injected prior to antibody treatment. Similar effects were observed in solid tumors, when a blocking mAb (anti-hCD47 B6H12) was used to perturb the interaction between CD47 and SIRPα. This resulted in enabling phagocytosis of malignant cells in vitro and reduction of tumor growth and metastasis in vivo [93, 94]. Comparable results were obtained in human multiple myeloma cells by blocking CD47–SIRPα interaction. Treating myeloma cells (RPMI8226) with anti-CD47 mAb (B6H12) resulted in increased phagocytosis together with growth inhibition and reduced osteoclastogenesis in xenotransplantation [95]. Apart from prevention of phagocytosis, CD47 antigen was shown to play a vital role in the dissemination of cancer cells in two in vivo models of human Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (DLBCL and Burkitt lymphoma). In both of these models, anti-CD47 antibody (B6H12.2) prevented the extranodal dissemination of tumor cells to several secondary sites albeit having a marginal effect on the site of origin [92]. In osteosarcoma and gastric cancer, CD47 was found to be highly expressed and correlated inversely with patient survival. Blockade of CD47 using antibody (B6H12) resulted in increased phagocytosis of tumor cells by macrophages. Treatment with antibody also caused a reduction in invasion and spontaneous metastasis of cells [13, 96]. In leiomyosarcoma (LMS), as an attempt to imitate neoadjuvant therapy in patients, anti-CD47 therapy was initiated after allowing the primary tumor to establish for 7 days in a xenotransplanted model of LMS. The treatment efficiently inhibited lung metastasis compared to the IgG-treated groups. This observation showed that antiCD47 mAb can be used in conjunction with radiation therapy to eliminate metastatic disease [97]. Besides phagocytosis, blockade of tumor cells with anti-CD47 mAb also led to a cytotoxic CD8 T cell immune response against the tumor. Thus, the mechanism of action of antibody involved both innate and adaptive immune response in eliminating tumor cells [98].

In addition to the above mentioned CSC-specific surface markers, there are promising molecules that could be alternative potential targets. Although definitive evidence that they are CSC specific does not exist, they can be targeted.

5T4 (trophoblast glycoprotein-TPBG)

Oncofoetal antigen 5T4 is a transmembrane glycoprotein found to be expressed at a higher level in solid carcinomas, primarily CSCs from head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), ovarian and gastric carcinomas [99]. Expression of 5T4 is correlated with poor clinical outcome or advanced disease. Humanised Anti-5T4-ADC (A1mcMMAF) linked to the tubulin inhibitor monomethylauristatin F (MMAF) was used to therapeutically target CSCs [99]. Treatment with A1mcMMAF resulted in persistent tumor regression of 37622A1 tumor xenograft, indicating a decrease in CSC population [99]. Similarly, an antibody drug conjugate (MEDI0641) having a DNA damaging “payload” (pyrrolobenzodiazepine) treatment in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) cell lines (UM-SSC-11B and UM-SSC-22B) caused significant reduction of CSCs in vitro and sustained tumor regression of established PDX HNSCC tumors in vivo [100, 101]. Nevertheless, none of these antibodies have any functional effect on the targeted CSCs.

Interleukins (IL-22, IL-8, IL-6)

Tumor microenvironment plays a vital role in helping CSCs to evade conventional therapies and maintain their activity due to the presence of inbuilt complex cytokine networks. In breast cancer, there is evidence that C-X-C chemokine receptor 1 (CXCR1) and C-X-C chemokine receptor 2 (CXCR2) signaling aids in enhancing metastasis, drug resistance and the invasive property of CSCs [102]. IL-8 signaling has been reported to promote stemness and epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) in primary invasive and metastatic breast cancer cells [103]. IL-22 has shown to be related to cancer stem cell phenotype, recurrence and clinical outcome [104]. Induction of methyl transferase DOT1L and activation of STAT 3 are mechanisms through which IL-22 + CD4 + T cells enhance stemness of CSCs [105]. Multifunctional cytokine IL-6 is a known regulator of CSC self- renewal [106]. Similarly IL-6 signaling pathway helps in the formation of CSCs, development of chemo-resistance and maintenance of self-renewing ability by regulating and altering several downstream pathways. In glioma stem cells, IL-6, IL-6R, GP130 and STAT3 are differentially expressed at a higher level in comparison to the non-cancer stem cells [107]. Several targeted mAbs against IL-6 (CNTO 328, B-E8, Tocilizumab) are presently under clinical trials [107]. However, the ability of these antibodies to target only CSCs and their functionalities has not been proven conclusively till date. In addition to cytokines, another important component of the tumor microenvironment is myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). These cells have the capability of improving sphere formation, metastasis and stemness gene expression in CSCs [108]. MDSCs target stem cell-specific genes through the expression of miRNA101 and suppression of c-terminal binding protein-1 (CtBP2) which ultimately relates to poor patient survival. In azoxymethane and dextran sodium sulphate (AOM-DSS) treated mice, anti-glycan antibodies (mAbGB3.1) against MDSCs showed marked decrease in tumor formation with impaired levels of TNF-α and IL-6 cytokines [109]. In leukemia, myeloid differentiation antigen, CD33, was targeted using a humanized IgG4 anti-CD33 antibody hP67.6 conjugated with calichecimin derivative which significantly repressed colony-forming cells and xenografts in athymic mice [110].

Her-2 (Erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase)

Recently it has been shown that Her2, a transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase, amplified in 20% of breast cancers, is also selectively expressed on CSCs from luminal estrogen receptor positive breast cancers (irrespective of Her2 gene amplification) [111, 112]. Trastuzumab treatment could successfully target CSCs in luminal breast cancer cell lines MCF7 and ZR75-1A by significantly abrogating mammosphere formation. It also reduced cells expressing CSC-specific markers like ALDH and CD44+ CD24−. There was growth reduction in xenograft models when Herceptin was administered immediately after cell inoculation [111, 113]. An antibody–drug conjugate transtuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) has displayed promising effects in targeting CSCs from Her2 positive breast cancers. Incubation of SKBR3 and BT-474 cells with T-DM1 reduced the colony-forming ability of sorted CD44+ CD24− cells unlike trastuzumab alone. These sorted putative CSCs also preferentially internalized the antibody conjugate which could be reversed by autophagy inhibitors like chloroquine, 3′-methyl adenine or artesuante [111].

CAR T cell therapy

In contrast to antibodies targeting CSCs specifically, an alternative immunological approach seems promising. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) redirected T cells are rapidly evolving as a potent and powerful therapy in cancer therapeutics, especially against aggressive hematological malignancies. Specific binding domain of the tumor targeting antibody (Fab) is combined with the T cell signaling domain to form a genetically engineered CAR that is expressed in a T cell. This leads to the specific antibody redirected activation of the T cell. After infusion, CAR T cells can proliferate and impart persistent immunity [114]. Although CAR T cell therapy has opened up a new field with CD19 CAR T cells in leukemia, the efficacy, safety and specificity of this technology remain limited to hematological malignancies. A combinatorial treatment of CAR T cells with specific small molecule inhibitors, cytokines, chemokines or immunomodulatory agents might turn out to be a more effective strategy to target solid malignancies which are intrinsically heterogeneous, have a suppressive microenvironment and lacks tumor specific antigens [115, 116]. With promising preclinical data from CD33/CD3 bi-specific T-cell engager (BiTE), a CD33-directed CAR T cell therapy could possibly be a better alternative compared to the anti-CD33 drug conjugate GO (gemtuzumab ozogamicin- mylotarg) [117]. Similarly, there are encouraging preliminary preclinical data with CD123- and CD44v6-directed CAR in AML and myeloma. Thus, CAR T marks the emergence of a new personalized therapeutic strategy with targeted specifications [117].

Disadvantages of CSC targeting strategies

CSC targeting techniques including the use of functional antibodies have been quite reassuring, except that some of them might not be really specific due to the presence of antigen in normal stem cells. Moreover, these slow dividing or quiescent cells may reside in a niche devoid of proper oxygen and nutrient supply, thereby limiting the ability of antibodies or other targeting agents to reach them. Another approach is to induce differentiation of CSCs and overcome their neoplastic self-renewing ability. A screen of libraries of small compounds that are capable of inducing differentiation was performed using a discovery platform that utilized the difference between a CSC and a normal pluripotent stem cell. Thioridazine, an anti-psychotic drug, was found to be highly selective against CSCs sparing the normal stem cell compartment by antagonizing the dopamine receptors on their surface [118].

Future clinical uses

It is apparent from various studies that CSCs exist in human cancer [3–6]. Although not yet conclusively proven to mark dormant cells and demonstrate their role in recurrence, they offer a different target to develop new drugs. In addition to small molecules that are being developed to target these cells, monoclonal antibodies are equally promising. However, there are several issues that need to be addressed with respect to antibodies. Antibodies that do not merely recognize the surface antigen but have a functional effect on CSCs are probably required. Further, accessibility of the antibody to malignant cells may be compromised by tumor hypoxia and vascularity. Heterogeneity in tumor and even within CSCs is a problem in ensuring the specific effect of any antibody. This is further complicated in some instances of non-stem like malignant cells within a tumor acquiring properties of CSCs. It is perhaps for all the above reasons that CSC-specific antibodies may be more effective when the bulk of the tumor has been removed by surgery or chemotherapy. Definitive trials have to be conducted to prove that they can eliminate a small fraction of cells after initial treatment by surgery, chemotherapy and/or radiation. There is some evidence that this approach as maintenance treatment may work. In follicular lymphoma, after the initial treatment, Rituximab is given as maintenance and prolongs survival [119]. Similarly, there is evidence for Trastuzumab in c-ErbB2 positive breast tumors [120, 121]. Ideally, maintenance therapy with antibodies targeting cancer stem cells when the residual tumor bulk is minimal is the way forward in the long term.

Acknowledgements

Supported by University Grants Commission (UGC), Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR). Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Govt. of India.

Smarakan Sneha is a University Grants Commission Senior Research Fellow (UGC-SRF) awardee. Syama Krishna Priya and Rohit Pravin Nagare are Indian Council for Medical Research Senior Research fellows (ICMR –SRF) and Chirukandath Sidhanth is supported by Department of Biotechnology (DBT).

Abbreviations

- ABCG2

ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 2

- ADCC

Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity

- AML

Acute myeloid leukemia

- CAR

Chimeric antigen receptor

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- CSC

Cancer stem cell

- HNSCC

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- HSC

Hematopoietic stem cell

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- ISC

Intestinal stem cell

- LSC

Leukemia stem cell

- NOD-SCID

Non-obese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency

- SIRPα

Signal regulatory protein alpha

Author contribution

SS conceived, wrote and RPN, SKP, CS, KP edited the manuscript. TSG conceived, reviewed and edited all versions of the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Deonarain MP, Kousparou CA, Epenetos AA. Antibodies targeting cancer stem cells: a new paradigm in immunotherapy? MAbs. 2009;1:12–25. doi: 10.4161/mabs.1.1.7347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naujokat C. Monoclonal antibodies against human cancer stem cells. Immunotherapy. 2014;6:290–308. doi: 10.2217/imt.14.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3:730–737. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, Squire JA, Bayani J, Hide T, Henkelman RM, Cusimano MD, Dirks PB. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004;432:396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, Dick JE. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 2007;445:106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature05372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li C, Heidt DG, Dalerba P, Burant CF, Zhang L, Adsay V, Wicha M, Clarke MF, Simeone DM. Identification of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1030–1037. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaffer CL, Marjanovic ND, Lee T, Bell G, Kleer CG, Reinhardt F, D’Alessio AC, Young RA, Weinberg RA. Poised chromatin at the ZEB1 promoter enables breast cancer cell plasticity and enhances tumorigenicity. Cell. 2013;154:61–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang J, Sakariassen PO, Tsinkalovsky O, Immervoll H, Boe SO, Svendsen A, Prestegarden L, Rosland G, Thorsen F, Stuhr L, Molven A, Bjerkvig R, Enger PO. CD133 negative glioma cells form tumors in nude rats and give rise to CD133 positive cells. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:761–768. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang D, Nguyen TK, Leishear K, Finko R, Kulp AN, Hotz S, Van Belle PA, Xu X, Elder DE, Herlyn M. A tumorigenic subpopulation with stem cell properties in melanomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9328–9337. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao Q, Geng L, Kvalheim G, Gaudernack G, Suo Z. Identification of cancer stem-like side population cells in ovarian cancer cell line OVCAR-3. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2009;33:175–181. doi: 10.3109/01913120903086072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szotek PP, Pieretti-Vanmarcke R, Masiakos PT, Dinulescu DM, Connolly D, Foster R, Dombkowski D, Preffer F, Maclaughlin DT, Donahoe PK. Ovarian cancer side population defines cells with stem cell-like characteristics and mullerian inhibiting substance responsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11154–11159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603672103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu JF, Pan XH, Zhang SJ, Zhao C, Qiu BS, Gu HF, Hong JF, Cao L, Chen Y, Xia B, Bi Q, Wang YP. CD47 blockade inhibits tumor progression human osteosarcoma in xenograft models. Oncotarget. 2015;6:23662–23670. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmadi H, Baharvand H, Ashtiani SK, Soleimani M, Sadeghian H, Ardekani JM, Mehrjerdi NZ, Kouhkan A, Namiri M, Madani-Civi M, Fattahi F, Shahverdi A, Dizaji AV. Safety analysis and improved cardiac function following local autologous transplantation of CD133(+) enriched bone marrow cells after myocardial infarction. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2007;4:153–160. doi: 10.2174/156720207781387141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith PJ, Wiltshire M, Chappell SC, Cosentino L, Burns PA, Pors K, Errington RJ. Kinetic analysis of intracellular Hoechst 33342–DNA interactions by flow cytometry: misinterpretation of side population status? Cytometry A. 2013;83:161–169. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pors K, Moreb JS. Aldehyde dehydrogenases in cancer: an opportunity for biomarker and drug development? Drug Discov Today. 2014;19:1953–1963. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagare RP, Sneha S, Priya SK, Ganesan TS. Cancer stem cells—are surface markers alone sufficient? Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;12:37–44. doi: 10.2174/1574888X11666160607211436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krishna Priya S, Nagare RP, Sneha VS, Sidhanth C, Bindhya S, Manasa P, Ganesan TS. Tumour angiogenesis—origin of blood vessels. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:729–735. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thiagarajan PS, Hitomi M, Hale JS, Alvarado AG, Otvos B, Sinyuk M, Stoltz K, Wiechert A, Mulkearns-Hubert E, Jarrar AM, Zheng Q, Thomas D, Egelhoff TT, Rich JN, Liu H, Lathia JD, Reizes O. Development of a fluorescent reporter system to delineate cancer stem cells in triple-negative breast cancer. Stem Cells. 2015;33:2114–2125. doi: 10.1002/stem.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ye J, Wu D, Wu P, Chen Z, Huang J. The cancer stem cell niche: cross talk between cancer stem cells and their microenvironment. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:3945–3951. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1561-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eppert K, Takenaka K, Lechman ER, Waldron L, Nilsson B, van Galen P, Metzeler KH, Poeppl A, Ling V, Beyene J, Canty AJ, Danska JS, Bohlander SK, Buske C, Minden MD, Golub TR, Jurisica I, Ebert BL, Dick JE. Stem cell gene expression programs influence clinical outcome in human leukemia. Nat Med. 2011;17:1086–1093. doi: 10.1038/nm.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merlos-Suarez A, Barriga FM, Jung P, Iglesias M, Cespedes MV, Rossell D, Sevillano M, Hernando-Momblona X, da Silva-Diz V, Munoz P, Clevers H, Sancho E, Mangues R, Batlle E. The intestinal stem cell signature identifies colorectal cancer stem cells and predicts disease relapse. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:511–524. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nadler LM, Stashenko P, Hardy R, Kaplan WD, Button LN, Kufe DW, Antman KH, Schlossman SF. Serotherapy of a patient with a monoclonal antibody directed against a human lymphoma-associated antigen. Cancer Res. 1980;40:3147–3154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott AM, Wolchok JD, Old LJ. Antibody therapy of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:278–287. doi: 10.1038/nrc3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Gast GC, van de Winkel JG, Bast BE. Clinical perspectives of bispecific antibodies in cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1997;45:121–123. doi: 10.1007/s002620050412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tai MS, Mudgett-Hunter M, Levinson D, Wu GM, Haber E, Oppermann H, Huston JS. A bifunctional fusion protein containing Fc-binding fragment B of staphylococcal protein A amino terminal to antidigoxin single-chain Fv. Biochemistry. 1990;29:8024–8030. doi: 10.1021/bi00487a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanha J, Dubuc G, Hirama T, Narang SA, MacKenzie CR. Selection by phage display of llama conventional V(H) fragments with heavy chain antibody V(H)H properties. J Immunol Methods. 2002;263:97–109. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(02)00027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reichert JM, Rosensweig CJ, Faden LB, Dewitz MC. Monoclonal antibody successes in the clinic. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1073–1078. doi: 10.1038/nbt0905-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones PT, Dear PH, Foote J, Neuberger MS, Winter G. Replacing the complementarity-determining regions in a human antibody with those from a mouse. Nature. 1986;321:522–525. doi: 10.1038/321522a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luginbuhl B, Kanyo Z, Jones RM, Fletterick RJ, Prusiner SB, Cohen FE, Williamson RA, Burton DR, Pluckthun A. Directed evolution of an anti-prion protein scFv fragment to an affinity of 1 pM and its structural interpretation. J Mol Biol. 2006;363:75–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lonberg N. Human monoclonal antibodies from transgenic mice. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;181:69–97. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-73259-4_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McNeil C. Herceptin raises its sights beyond advanced breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:882–883. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.12.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beuzeboc P, Scholl S, Garau XS, Vincent-Salomon A, Cremoux PD, Couturier J, Palangie T, Pouillart P. Herceptin, a monoclonal humanized antibody anti-HER2: a major therapeutic progress in breast cancers overexpressing this oncogene? Bull Cancer. 1999;86:544–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Zoobi L, Salti S, Colavecchio A, Jundi M, Nadiri A, Hassan GS, El-Gabalawy H, Mourad W. Enhancement of Rituximab-induced cell death by the physical association of CD20 with CD40 molecules on the cell surface. Int Immunol. 2014;26:451–465. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxu046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamashita M, Katakura Y, Shirahata S. Recent advances in the generation of human monoclonal antibody. Cytotechnology. 2007;55:55–60. doi: 10.1007/s10616-007-9072-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Logtenberg T. Antibody cocktails: next-generation biopharmaceuticals with improved potency. Trends Biotechnol. 2007;25:390–394. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maccalli C, De Maria R. Cancer stem cells: perspectives for therapeutic targeting. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2015;64:91–97. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1592-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunning NL, Laversin SA, Miles AK, Rees RC. Immunotherapy of prostate cancer: should we be targeting stem cells and EMT? Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60:1181–1193. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1065-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jin L, Hope KJ, Zhai Q, Smadja-Joffe F, Dick JE. Targeting of CD44 eradicates human acute myeloid leukemic stem cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:1167–1174. doi: 10.1038/nm1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Charrad RS, Gadhoum Z, Qi J, Glachant A, Allouche M, Jasmin C, Chomienne C, Smadja-Joffe F. Effects of anti-CD44 monoclonal antibodies on differentiation and apoptosis of human myeloid leukemia cell lines. Blood. 2002;99:290–299. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.1.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gadhoum Z, Delaunay J, Maquarre E, Durand L, Lancereaux V, Qi J, Robert-Lezenes J, Chomienne C, Smadja-Joffe F. The effect of anti-CD44 monoclonal antibodies on differentiation and proliferation of human acute myeloid leukemia cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:1501–1510. doi: 10.1080/1042819042000206687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang LZ, Ding X, Li XY, Cen JN, Chen ZX. In vitro effects of anti-CD44 monoclonal antibody on the adhesion and migration of chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2010;31:398–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang S, Wu CC, Fecteau JF, Cui B, Chen L, Zhang L, Wu R, Rassenti L, Lao F, Weigand S, Kipps TJ. Targeting chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells with a humanized monoclonal antibody specific for CD44. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:6127–6132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221841110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marangoni E, Lecomte N, Durand L, de Pinieux G, Decaudin D, Chomienne C, Smadja-Joffe F, Poupon MF. CD44 targeting reduces tumour growth and prevents post-chemotherapy relapse of human breast cancers xenografts. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:918–922. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Molejon MI, Tellechea JI, Moutardier V, Gasmi M, Ouaissi M, Turrini O, Delpero JR, Dusetti N, Iovanna J. Targeting CD44 as a novel therapeutic approach for treating pancreatic cancer recurrence. Oncoscience. 2015;2:572–575. doi: 10.18632/oncoscience.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Masuko K, Okazaki S, Satoh M, Tanaka G, Ikeda T, Torii R, Ueda E, Nakano T, Danbayashi M, Tsuruoka T, Ohno Y, Yagi H, Yabe N, Yoshida H, Tahara T, Kataoka S, Oshino T, Shindo T, Niwa S, Ishimoto T, Baba H, Hashimoto Y, Saya H, Masuko T. Anti-tumor effect against human cancer xenografts by a fully human monoclonal antibody to a variant 8-epitope of CD44R1 expressed on cancer stem cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Du YR, Chen Y, Gao Y, Niu XL, Li YJ, Deng WM. Effects and mechanisms of anti-CD44 monoclonal antibody A3D8 on proliferation and apoptosis of sphere-forming cells with stemness from human ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23:1367–1375. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e3182a1d023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perez A, Neskey DM, Wen J, Goodwin JW, Slingerland J, Pereira L, Weigand S, Franzmann EJ. Abstract 2521: targeting CD44 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) with a new humanized antibody RO5429083. Can Res. 2012;72:2521. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2012-2521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo YJ, Ma J, Wong JH, Lin SC, Chang HC, Bigby M, Sy MS. Monoclonal anti-CD44 antibody acts in synergy with anti-CD2 but inhibits anti-CD3 or T cell receptor-mediated signaling in murine T cell hybridomas. Cell Immunol. 1993;152:186–199. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1993.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heider KH, Kuthan H, Stehle G, Munzert G. CD44v6: a target for antibody-based cancer therapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:567–579. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0494-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kryczek I, Liu S, Roh M, Vatan L, Szeliga W, Wei S, Banerjee M, Mao Y, Kotarski J, Wicha MS, Liu R, Zou W. Expression of aldehyde dehydrogenase and CD133 defines ovarian cancer stem cells. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:29–39. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu Q, Nguyen DH, Dong Q, Shitaku P, Chung K, Liu OY, Tso JL, Liu JY, Konkankit V, Cloughesy TF, Mischel PS, Lane TF, Liau LM, Nelson SF, Tso CL. Molecular properties of CD133 + glioblastoma stem cells derived from treatment-refractory recurrent brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 2009;94:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9919-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Horst D, Kriegl L, Engel J, Jung A, Kirchner T. CD133 and nuclear beta-catenin: the marker combination to detect high risk cases of low stage colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:2034–2040. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hermann PC, Huber SL, Herrler T, Aicher A, Ellwart JW, Guba M, Bruns CJ, Heeschen C. Distinct populations of cancer stem cells determine tumor growth and metastatic activity in human pancreatic cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen W, Li F, Xue ZM, Wu HR. Anti-human CD133 monoclonal antibody that could inhibit the proliferation of colorectal cancer cells. Hybridoma (Larchmt) 2010;29:305–310. doi: 10.1089/hyb.2010.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Waldron NN, Barsky SH, Dougherty PR, Vallera DA. A bispecific EpCAM/CD133-targeted toxin is effective against carcinoma. Target Oncol. 2014;9:239–249. doi: 10.1007/s11523-013-0290-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Emlet DR, Gupta P, Holgado-Madruga M, Del Vecchio CA, Mitra SS, Han SY, Li G, Jensen KC, Vogel H, Xu LW, Skirboll SS, Wong AJ. Targeting a glioblastoma cancer stem-cell population defined by EGF receptor variant III. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1238–1249. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kristiansen G, Sammar M, Altevogt P. Tumour biological aspects of CD24, a mucin-like adhesion molecule. J Mol Histol. 2004;35:255–262. doi: 10.1023/B:HIJO.0000032357.16261.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sammar M, Aigner S, Hubbe M, Schirrmacher V, Schachner M, Vestweber D, Altevogt P. Heat-stable antigen (CD24) as ligand for mouse P-selectin. Int Immunol. 1994;6:1027–1036. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.7.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gao MQ, Choi YP, Kang S, Youn JH, Cho NH. CD24+ cells from hierarchically organized ovarian cancer are enriched in cancer stem cells. Oncogene. 2010;29:2672–2680. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sagiv E, Starr A, Rozovski U, Khosravi R, Altevogt P, Wang T, Arber N. Targeting CD24 for treatment of colorectal and pancreatic cancer by monoclonal antibodies or small interfering RNA. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2803–2812. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hemler ME. Tetraspanin functions and associated microdomains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:801–811. doi: 10.1038/nrm1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Higashiyama M, Taki T, Ieki Y, Adachi M, Huang CL, Koh T, Kodama K, Doi O, Miyake M. Reduced motility related protein-1 (MRP-1/CD9) gene expression as a factor of poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 1995;55:6040–6044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huang CI, Kohno N, Ogawa E, Adachi M, Taki T, Miyake M. Correlation of reduction in MRP-1/CD9 and KAI1/CD82 expression with recurrences in breast cancer patients. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:973–983. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65639-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mori M, Mimori K, Shiraishi T, Haraguchi M, Ueo H, Barnard GF, Akiyoshi T. Motility related protein 1 (MRP1/CD9) expression in colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:1507–1510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sho M, Adachi M, Taki T, Hashida H, Konishi T, Huang CL, Ikeda N, Nakajima Y, Kanehiro H, Hisanaga M, Nakano H, Miyake M. Transmembrane 4 superfamily as a prognostic factor in pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer. 1998;79:509–516. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19981023)79:5<509::AID-IJC11>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Houle CD, Ding XY, Foley JF, Afshari CA, Barrett JC, Davis BJ. Loss of expression and altered localization of KAI1 and CD9 protein are associated with epithelial ovarian cancer progression. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;86:69–78. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hori H, Yano S, Koufuji K, Takeda J, Shirouzu K. CD9 expression in gastric cancer and its significance. J Surg Res. 2004;117:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nakamoto T, Murayama Y, Oritani K, Boucheix C, Rubinstein E, Nishida M, Katsube F, Watabe K, Kiso S, Tsutsui S, Tamura S, Shinomura Y, Hayashi N. A novel therapeutic strategy with anti-CD9 antibody in gastric cancers. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:889–896. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang CL, Liu D, Masuya D, Kameyama K, Nakashima T, Yokomise H, Ueno M, Miyake M. MRP-1/CD9 gene transduction downregulates Wnt signal pathways. Oncogene. 2004;23:7475–7483. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Menendez J, Jin L, Poeppl A, Sayegh D, Reilly K, Ceric N, Vyas T, Gupta A, Hahn S, Young D, Dick J, Pereira D. Anti-CD9 antibody, AR40A746.2.3, inhibits tumor growth in pancreatic and breast cancer models and recognizes CD9 on CD34+ CD38− leukemic cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2014;68(9 Supplement):3993. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yamashita T, Ji J, Budhu A, Forgues M, Yang W, Wang HY, Jia H, Ye Q, Qin LX, Wauthier E, Reid LM, Minato H, Honda M, Kaneko S, Tang ZY, Wang XW. EpCAM-positive hepatocellular carcinoma cells are tumor-initiating cells with stem/progenitor cell features. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1012–1024. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yamashita T, Budhu A, Forgues M, Wang XW. Activation of hepatic stem cell marker EpCAM by Wnt-beta-catenin signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10831–10839. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Cancer stem cells in solid tumours: accumulating evidence and unresolved questions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:755–768. doi: 10.1038/nrc2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gires O, Klein CA, Baeuerle PA. On the abundance of EpCAM on cancer stem cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:143. doi: 10.1038/nrc2499-c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Riethmuller G, Holz E, Schlimok G, Schmiegel W, Raab R, Hoffken K, Gruber R, Funke I, Pichlmaier H, Hirche H, Buggisch P, Witte J, Pichlmayr R. Monoclonal antibody therapy for resected Dukes’ C colorectal cancer: seven-year outcome of a multicenter randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(5):1788–1794. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.5.1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ammons WS, Bauer RJ, Horwitz AH, Chen ZJ, Bautista E, Ruan HH, Abramova M, Scott KR, Dedrick RL. In vitro and in vivo pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of a human engineered monoclonal antibody to epithelial cell adhesion molecule. Neoplasia. 2003;5:146–154. doi: 10.1016/S1476-5586(03)80006-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Richter CE, Cocco E, Bellone S, Silasi DA, Ruttinger D, Azodi M, Schwartz PE, Rutherford TJ, Pecorelli S, Santin AD. High-grade, chemotherapy-resistant ovarian carcinomas overexpress epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) and are highly sensitive to immunotherapy with MT201, a fully human monoclonal anti-EpCAM antibody. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:582.e1–582.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Naundorf S, Preithner S, Mayer P, Lippold S, Wolf A, Hanakam F, Fichtner I, Kufer P, Raum T, Riethmuller G, Baeuerle PA, Dreier T. In vitro and in vivo activity of MT201, a fully human monoclonal antibody for pancarcinoma treatment. Int J Cancer. 2002;100:101–110. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bagley CJ, Woodcock JM, Stomski FC, Lopez AF. The structural and functional basis of cytokine receptor activation: lessons from the common beta subunit of the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, interleukin-3 (IL-3), and IL-5 receptors. Blood. 1997;89:1471–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Miyajima A, Mui AL, Ogorochi T, Sakamaki K. Receptors for granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, interleukin-3, and interleukin-5. Blood. 1993;82:1960–1974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jin L, Lee EM, Ramshaw HS, Busfield SJ, Peoppl AG, Wilkinson L, Guthridge MA, Thomas D, Barry EF, Boyd A, Gearing DP, Vairo G, Lopez AF, Dick JE, Lock RB. Monoclonal antibody-mediated targeting of CD123, IL-3 receptor alpha chain, eliminates human acute myeloid leukemic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sun Q, Woodcock JM, Rapoport A, Stomski FC, Korpelainen EI, Bagley CJ, Goodall GJ, Smith WB, Gamble JR, Vadas MA, Lopez AF. Monoclonal antibody 7G3 recognizes the N-terminal domain of the human interleukin-3 (IL-3) receptor alpha-chain and functions as a specific IL-3 receptor antagonist. Blood. 1996;87:83–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nievergall E, Ramshaw HS, Yong AS, Biondo M, Busfield SJ, Vairo G, Lopez AF, Hughes TP, White DL, Hiwase DK. Monoclonal antibody targeting of IL-3 receptor alpha with CSL362 effectively depletes CML progenitor and stem cells. Blood. 2014;123:1218–1228. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-475194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Majeti R, Becker MW, Tian Q, Lee TL, Yan X, Liu R, Chiang JH, Hood L, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Dysregulated gene expression networks in human acute myelogenous leukemia stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3396–3401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900089106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Okazawa H, Motegi S, Ohyama N, Ohnishi H, Tomizawa T, Kaneko Y, Oldenborg PA, Ishikawa O, Matozaki T. Negative regulation of phagocytosis in macrophages by the CD47-SHPS-1 system. J Immunol. 2005;174:2004–2011. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Blazar BR, Lindberg FP, Ingulli E, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Oldenborg PA, Iizuka K, Yokoyama WM, Taylor PA. CD47 (integrin-associated protein) engagement of dendritic cell and macrophage counterreceptors is required to prevent the clearance of donor lymphohematopoietic cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194:541–549. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Barclay AN, Brown MH. The SIRP family of receptors and immune regulation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:457–464. doi: 10.1038/nri1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Oldenborg PA, Gresham HD, Lindberg FP. CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPalpha) regulates Fcgamma and complement receptor-mediated phagocytosis. J Exp Med. 2001;193:855–862. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.7.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Oldenborg PA, Zheleznyak A, Fang YF, Lagenaur CF, Gresham HD, Lindberg FP. Role of CD47 as a marker of self on red blood cells. Science. 2000;288:2051–2054. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5473.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jaiswal S, Jamieson CH, Pang WW, Park CY, Chao MP, Majeti R, Traver D, van Rooijen N, Weissman IL. CD47 is upregulated on circulating hematopoietic stem cells and leukemia cells to avoid phagocytosis. Cell. 2009;138:271–285. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chao MP, Alizadeh AA, Tang C, Jan M, Weissman-Tsukamoto R, Zhao F, Park CY, Weissman IL, Majeti R. Therapeutic antibody targeting of CD47 eliminates human acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1374–1384. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Willingham SB, Volkmer JP, Gentles AJ, Sahoo D, Dalerba P, Mitra SS, Wang J, Contreras-Trujillo H, Martin R, Cohen JD, Lovelace P, Scheeren FA, Chao MP, Weiskopf K, Tang C, Volkmer AK, Naik TJ, Storm TA, Mosley AR, Edris B, Schmid SM, Sun CK, Chua MS, Murillo O, Rajendran P, Cha AC, Chin RK, Kim D, Adorno M, Raveh T, Tseng D, Jaiswal S, Enger PO, Steinberg GK, Li G, So SK, Majeti R, Harsh GR, van de Rijn M, Teng NN, Sunwoo JB, Alizadeh AA, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. The CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPa) interaction is a therapeutic target for human solid tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:6662–6667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121623109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chan KS, Espinosa I, Chao M, Wong D, Ailles L, Diehn M, Gill H, Presti J, Jr, Chang HY, van de Rijn M, Shortliffe L, Weissman IL. Identification, molecular characterization, clinical prognosis, and therapeutic targeting of human bladder tumor-initiating cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14016–14021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906549106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kim D, Wang J, Willingham SB, Martin R, Wernig G, Weissman IL. Anti-CD47 antibodies promote phagocytosis and inhibit the growth of human myeloma cells. Leukemia. 2012;26:2538–2545. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yoshida K, Tsujimoto H, Matsumura K, Kinoshita M, Takahata R, Matsumoto Y, Hiraki S, Ono S, Seki S, Yamamoto J, Hase K. CD47 is an adverse prognostic factor and a therapeutic target in gastric cancer. Cancer Med. 2015;4:1322–1333. doi: 10.1002/cam4.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Edris B, Weiskopf K, Volkmer AK, Volkmer JP, Willingham SB, Contreras-Trujillo H, Liu J, Majeti R, West RB, Fletcher JA, Beck AH, Weissman IL, van de Rijn M. Antibody therapy targeting the CD47 protein is effective in a model of aggressive metastatic leiomyosarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:6656–6661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121629109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tseng D, Volkmer JP, Willingham SB, Contreras-Trujillo H, Fathman JW, Fernhoff NB, Seita J, Inlay MA, Weiskopf K, Miyanishi M, Weissman IL. Anti-CD47 antibody-mediated phagocytosis of cancer by macrophages primes an effective antitumor T-cell response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:11103–11108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305569110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sapra P, Damelin M, Dijoseph J, Marquette K, Geles KG, Golas J, Dougher M, Narayanan B, Giannakou A, Khandke K, Dushin R, Ernstoff E, Lucas J, Leal M, Hu G, O’Donnell CJ, Tchistiakova L, Abraham RT, Gerber HP. Long-term tumor regression induced by an antibody-drug conjugate that targets 5T4, an oncofetal antigen expressed on tumor-initiating cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:38–47. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Damelin M, Geles KG, Follettie MT, Yuan P, Baxter M, Golas J, DiJoseph JF, Karnoub M, Huang S, Diesl V, Behrens C, Choe SE, Rios C, Gruzas J, Sridharan L, Dougher M, Kunz A, Hamann PR, Evans D, Armellino D, Khandke K, Marquette K, Tchistiakova L, Boghaert ER, Abraham RT, Wistuba II, Zhou BB. Delineation of a cellular hierarchy in lung cancer reveals an oncofetal antigen expressed on tumor-initiating cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4236–4246. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kerk S, Finkel K, Pearson AT, Warner K, Zhang Z, Nor F, Wagner VP, Vargas PA, Wicha MS, Hurt EM, Hollingsworth RE, Tice DA, Nor JE. 5T4-targeted therapy ablates cancer stem cells and prevents recurrence of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:2516–2527. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Singh JK, Simoes BM, Howell SJ, Farnie G, Clarke RB. Recent advances reveal IL-8 signaling as a potential key to targeting breast cancer stem cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:210. doi: 10.1186/bcr3436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Singh JK, Farnie G, Bundred NJ, Simoes BM, Shergill A, Landberg G, Howell SJ, Clarke RB. Targeting CXCR1/2 significantly reduces breast cancer stem cell activity and increases the efficacy of inhibiting HER2 via HER2-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:643–656. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zou W, Wicha MS. Chemokines and cellular plasticity of ovarian cancer stem cells. Oncoscience. 2015;2:615–616. doi: 10.18632/oncoscience.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kryczek I, Lin Y, Nagarsheth N, Peng D, Zhao L, Zhao E, Vatan L, Szeliga W, Dou Y, Owens S, Zgodzinski W, Majewski M, Wallner G, Fang J, Huang E, Zou W. IL-22(+)CD4(+) T cells promote colorectal cancer stemness via STAT3 transcription factor activation and induction of the methyltransferase DOT1L. Immunity. 2014;40:772–784. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Guo Y, Xu F, Lu T, Duan Z, Zhang Z. Interleukin-6 signaling pathway in targeted therapy for cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:904–910. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bharti R, Dey G, Mandal M. Cancer development, chemoresistance, epithelial to mesenchymal transition and stem cells: a snapshot of IL-6 mediated involvement. Cancer Lett. 2016;375:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cui TX, Kryczek I, Zhao L, Zhao E, Kuick R, Roh MH, Vatan L, Szeliga W, Mao Y, Thomas DG, Kotarski J, Tarkowski R, Wicha M, Cho K, Giordano T, Liu R, Zou W. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells enhance stemness of cancer cells by inducing microRNA101 and suppressing the corepressor CtBP2. Immunity. 2013;39:611–621. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wesolowski R, Markowitz J, Carson WE., 3rd Myeloid derived suppressor cells—a new therapeutic target in the treatment of cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2013;1:10. doi: 10.1186/2051-1426-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Walter RB, Appelbaum FR, Estey EH, Bernstein ID. Acute myeloid leukemia stem cells and CD33-targeted immunotherapy. Blood. 2012;119:6198–6208. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-325050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Diessner J, Bruttel V, Stein RG, Horn E, Hausler SF, Dietl J, Honig A, Wischhusen J. Targeting of preexisting and induced breast cancer stem cells with trastuzumab and trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1149. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bruttel VS, Wischhusen J. Cancer stem cell immunology: key to understanding tumorigenesis and tumor immune escape? Front Immunol. 2014;5:360. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ithimakin S, Day KC, Malik F, Zen Q, Dawsey SJ, Bersano-Begey TF, Quraishi AA, Ignatoski KW, Daignault S, Davis A, Hall CL, Palanisamy N, Heath AN, Tawakkol N, Luther TK, Clouthier SG, Chadwick WA, Day ML, Kleer CG, Thomas DG, Hayes DF, Korkaya H, Wicha MS. HER2 drives luminal breast cancer stem cells in the absence of HER2 amplification: implications for efficacy of adjuvant trastuzumab. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1635–1646. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Dai H, Wang Y, Lu X, Han W. Chimeric antigen receptors modified T-cells for cancer therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Almåsbak H, Aarvak T, Vemuri MC. CAR T cell therapy: a game changer in cancer treatment. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:5474602. doi: 10.1155/2016/5474602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zhang H, Ye ZL, Yuan ZG, Luo ZQ, Jin HJ, Qian QJ. New Strategies for the Treatment of Solid Tumors with CAR-T Cells. Int J Biol Sci. 2016;12:718–729. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.14405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Maus MV, Grupp SA, Porter DL, June CH. Antibody-modified T cells: CARs take the front seat for hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2014;123:2625–2635. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-492231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sachlos E, Risueno RM, Laronde S, Shapovalova Z, Lee JH, Russell J, Malig M, McNicol JD, Fiebig-Comyn A, Graham M, Levadoux-Martin M, Lee JB, Giacomelli AO, Hassell JA, Fischer-Russell D, Trus MR, Foley R, Leber B, Xenocostas A, Brown ED, Collins TJ, Bhatia M. Identification of drugs including a dopamine receptor antagonist that selectively target cancer stem cells. Cell. 2012;149:1284–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Salles G, Seymour JF, Offner F, Lopez-Guillermo A, Belada D, Xerri L, Feugier P, Bouabdallah R, Catalano JV, Brice P, Caballero D, Haioun C, Pedersen LM, Delmer A, Simpson D, Leppa S, Soubeyran P, Hagenbeek A, Casasnovas O, Intragumtornchai T, Ferme C, da Silva MG, Sebban C, Lister A, Estell JA, Milone G, Sonet A, Mendila M, Coiffier B, Tilly H. Rituximab maintenance for 2 years in patients with high tumour burden follicular lymphoma responding to rituximab plus chemotherapy (PRIMA): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:42–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]