Abstract

Small molecules targeting kinases involved in B cell receptor signaling are showing encouraging clinical activity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients. Fostamatinib (R406) and entospletinib (GS-9973) are ATP-competitive inhibitors designed to target spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) that have shown clinical activity with acceptable toxicity in trials with CLL patients. Preclinical studies with these inhibitors in CLL have focused on their effect in patient-derived leukemic B cells. In this work we show that clinically relevant doses of R406 and GS-9973 impaired the activation and proliferation of T cells from CLL patients. This effect could not be ascribed to Syk-inhibition given that we show that T cells from CLL patients do not express Syk protein. Interestingly, ζ-chain-associated protein kinase (ZAP)-70 phosphorylation was diminished by both inhibitors upon TCR stimulation on T cells. In addition, we found that both agents reduced macrophage-mediated phagocytosis of rituximab-coated CLL cells. Overall, these results suggest that in CLL patients treated with R406 or GS-9973 T cell functions, as well as macrophage-mediated anti-tumor activity of rituximab, might be impaired. The potential consequences for CLL-treated patients are discussed.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-016-1946-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia, GS-9973, R406, Syk inhibitors, BCR-associated kinase inhibitors

Introduction

Leukemic B cells from CLL patients proliferate in lymphoid tissues in particular areas termed proliferation centers where they are in close contact with stroma, monocyte-derived nurse-like cells and activated T cells [1, 2]. Signals derived from these accessory cells provide a supportive microenvironment which not only promotes CLL cell survival and proliferation but also protects leukemic cells from cytotoxic therapies favoring the relapse of the disease [3]. T cells seem to play a key role in this microenvironment. Bagnara et al. [4] showed in a murine adoptive transfer model of CLL that the presence of activated autologous T CD4+ cells was necessary for human leukemic cell engraftment, survival and proliferation. Moreover, microscopy analysis of lymph nodes from CLL patients showed that CD3+ cells are present in high numbers and mainly localized within proliferation centers [5–7], and also that proliferating leukemic cells expressing Ki67 are found preferentially next to activated CD4+ T cells [5, 8]. In line with this, in vitro experiments showed that activated T CD4+ lymphocytes can promote CLL cell proliferation and survival through the secretion of anti-apoptotic cytokines, such as IL-4 [9] or IFN-γ [10], and the expression of the molecule CD40 ligand (CD40L) which interacts with CLL cells through CD40 [6, 8]. Also, CD8+ T cells from CLL patients were shown to inhibit specifically leukemic B cell apoptosis in vitro mediated in part by soluble factors [11].

In the last few years, several small molecules targeting kinases involved in B cell receptor (BCR) signaling have been developed and tested in clinical trials with CLL patients. R406 is an ATP-competitive kinase inhibitor relatively selective to Syk and in a lesser degree to other kinases including Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (Flt3) and lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase (Lck) [12]. In vitro studies showed that R406 can induce CLL cell apoptosis by disrupting BCR signaling and other microenvironmental interactions [13, 14]. Fostamatinib disodium (R788; FosD) is the prodrug of R406 available in an oral formulation which was initially developed for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis [12]. The therapeutic effect of fostamatinib in CLL has been successfully tested in the mouse model of CLL Eμ-TCL1 [15] and in a phase I/II study showing both safety and efficacy in patients with B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and CLL [16]. More recently entospletinib (GS-9973), another ATP-competitive inhibitor of Syk, with higher selectivity than R406 has been developed [17] and tested in a clinical trial with CLL patients showing clinical activity and good tolerance in relapsed or refractory patients [18]. At the present, GS-9973 is being tested in clinical trials with patients with different hematological disorders including CLL.

Besides their effects on leukemic cells, kinase inhibitors also affect other cell populations from the immune system. For example, the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk) inhibitor, ibrutinib, modulates T cell activation in CLL patients, favoring the differentiation toward the T helper (Th) type 1 profile, while it inhibits Th2 activation [19]. Moreover, we [20] and others [21] have recently described that ibrutinib impairs macrophage-mediated phagocytosis of leukemic cells opsonized with rituximab, which is a central mechanism of the anti-CD20 therapy [22, 23]. R406 was also shown to inhibit graft versus host disease in a mouse model by impairing murine T cell activation directly [24] or by targeting antigen presenting cells [25].

Considering the key role of T cells and macrophages in CLL pathogenesis and therapy, the goal of this work was to study the effect of R406 and GS-9973 on these cells.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

RPMI 1640 was purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA), and FCS, penicillin and streptomycin were obtained from GIBCO Laboratories (Grand Island, NY, USA). The human recombinant chemokines CXCL12/SDF-1, CCL19 and CCL21 were purchased from PeproTech (DF, Mexico). BSA was obtained from Wiener Laboratorios (Santa Fé, Argentina).

FITC-, PE- or PerCP-Cy™5.5-conjugated mAbs specific for CD69 (clone FN50), CD40L (clone TRAP-1), CCR7 (clone 3D12) and for CXCR4 (clone 12G5) were purchased from BD Bioscience, Pharmingen (CA, USA). FITC-, PE- or PerCP-Cy5-conjugated mAbs specific for CD3 (clone HIT3a), CD4 (clone OKT4), CD8 (clone HIT8a), CD14 (clone HCD14) and CD25 (clone M-A251) and antibodies with irrelevant specificity (isotype controls) were obtained from Biolegend (CA, USA). PE-conjugated mAbs specific for CD56 (clone HLDA6) and CD19 (clone J3-119) were obtained from Beckman Coulter (CA, USA). Annexin-V FITC was obtained from Immunotools (Friesoythe, Germany).

For western blot, the mAb specific for Syk (clone 4D10.1) was obtained from Upstate Biotechnology (NY, USA). Polyclonal antibodies (pAb) specific for phospho-ZAP-70 (Tyr319) and mAb for β-actin (8H10D10) were obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA). The HRP-conjugated mAb for mouse IgG was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and the HRP-conjugated mAb for rabbit IgG from Jackson ImmunoResearch, Inc (West Grove, PA, USA).

For ELISA assays, human IFN-γ kit was obtained from BD Bioscience, human IL-10 kit from Biolegend and human IL-4 kit was purchased from eBioscience (CA, USA). Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) was purchased from Invitrogen Argentina Ltd (Bs. As. Argentine), Monensin (BD GolgiStop™) from BD Biosciences and DMSO from Sigma-Aldrich. IL-15 and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) were obtained from BioLegend. Rituximab was obtained from Roche Diagnostics GmbH (Mannheim, Germany).

Fostamatinib (R406) was provided by Rigel Pharmaceuticals, and entospletinib (GS-9973) was purchased from Medkoo Biosciences (North Carolina, USA).

CLL patient and healthy donor samples

Peripheral blood samples were obtained from CLL patients and age-matched healthy donors. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with Institutional Review Board approval from the National Academy of Medicine, Buenos Aires. CLL was diagnosed according to standard clinical and laboratory criteria. At the time of the analysis, all patients were free from clinically relevant infectious complications and were either untreated or had not received treatment for a period of at least 6 months before investigation. Clinical characteristics of CLL patients included in this study are depicted in Supplementary Table 1.

Cell separation procedures and culture

PBMC were isolated from fresh blood samples by centrifugation over a Ficoll-Triyosom layer (Lymphoprep, Nycomed Pharma, Oslo, Norway), washed twice with saline and resuspended in complete medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin).

T cells from CLL patients and healthy donors were purified by positive selection using CD3 MicroBeads according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany, % purity >97) for western blot analysis of Syk in freshly isolated T cells. Negative selection of T cells was performed for functional assays to avoid CD3 downregulation, using a BD FACS Aria II Cell sorter cytometer after incubating peripheral blood cells with mAbs specific for CD19, CD14 and CD56 (% purity >97).

Evaluation of activation markers on TCR-stimulated T cells

PBMC or purified T cells from CLL patients were pretreated with DMSO, R406 or GS-9973 (0.1 or 1 µM) for 30 min and then transferred to a 48-well culture plate with immobilized anti-CD3 mAb or isotype control (0.15 µg/mL). After 24 h of culture, the expression of CD25 and CD69 was evaluated on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

CD40L (CD154) expression on CD4+ T cells was measured by adding FITC-conjugated anti-CD154 mAb and monensin (2 µM) to the culture during the stimulation, as described previously [26]. CD40L expression was analyzed by flow cytometry on CD4+ T cells after 24 h of culture.

Assessment of T cell proliferation

T cell proliferation was evaluated by flow cytometry using the CFSE dilution assay. PBMC or purified T cells from CLL patients were labeled with CFSE 1 µM according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Afterward, cells were pretreated with DMSO, R406 or GS-9973 (0.1 or 1 µM) for 30 min and then transferred to a 48-well culture plate with immobilized anti-CD3 mAb or isotype control (0.3 µg/mL) or IL-15 (20 ng/ml). After 5 days of culture, cells were collected and stained with mAbs specific for CD4 (PerCP-Cy5) and for CD8 (PE). The number of cells that had proliferated was determined by gating on the CFSElow CD4+ or CD8+ subset of the viable cells, gated according to FSC and SSC parameters criteria.

Chemotaxis assay and chemokine receptor evaluation

PBMC were resuspended in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1% FCS and treated with DMSO, R406 or GS-9973 (1 or 5 µM) for 30 min. Then, cells were used to evaluate CCR7 and CXCR4 by flow cytometry and to evaluate chemotaxis response toward CCL19, CCL21 and CXCL12. Chemotaxis assay was performed by using the Transwell System in 96-well Transwell plate with pore size 5 µm and polycarbonate membranes (Costar, Corning Incorporated, NY, USA). 70 µL of medium containing 0.5 × 106 cells was placed in the upper chamber, and 200 µL of medium alone (control) or medium with CCL19, CCL21 or CXCL12 was placed in the lower chamber. Each condition was performed in duplicate. After 2 h of culture at 37 °C, migrating cells in the lower chamber were counted by flow cytometry as the number of cells acquired in 30 s under a defined flow rate. Migration index was calculated by determining the ratio of migrated T cells (CD3+ CD4+ or CD3+ CD8+) in response to the chemokine versus spontaneous migrated T cells (control well with medium alone), taking the spontaneous migration in control wells as 100%. The spontaneous migration in control wells was always close to 1% of CD3+ cells placed in the upper compartment. CXCL12, CCL19 and CCL21 concentration used for the assays was 1 µg/mL [27].

Western blot

Whole-cell lysates were obtained from 3 × 106 purified T or B cells from CLL patients and healthy donors using 60 µL of loading buffer 1 × 5% β-mercaptoethanol. Lysates were boiled at 99 °C for 5 min, and 30 µL of the protein extracts were separated on a standard 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Membranes were then blotted with antibodies against Syk followed by HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. Specific bands were developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) method. The same membrane was blotted with mAb anti-β-actin followed by HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG to compare the total amount of protein in each sample.

For phospho-ZAP-70 evaluation, T cells from CLL patients and age-matched healthy donors were purified by negative selection and then pretreated with DMSO, R406 or GS-9973 (1 µM) for 30 min in RPMI 1640 1% FCS. Then, cells were stimulated with mouse mAb anti-CD3 (6 µg/mL)/anti-CD28 (1 µg/mL) and anti-IgG mouse pAb (15 µg/mL) or the anti-IgG mouse alone (control). After 5 min of stimulation, cells were washed with cold PBS, then protein extracts were obtained as described before, separated on a standard 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane. Membranes were then blotted with antibodies against phospho-ZAP-70 and β-actin, followed by HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG or anti-mouse IgG, respectively. Specific bands were developed by ECL.

Phagocytosis assay

Macrophages were differentiated from healthy donors’ or chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients’ monocytes by culturing them for 5 days in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS and M-CSF (50 ng/mL). For the phagocytosis assay, macrophages were treated for 30 min with R406, GS-9973 or DMSO and then CLL cells, that were previously labeled with CFSE (1 μM) and coated or not with rituximab (50 μg/mL), were added to the culture. After 2 h, macrophages were trypsinized and the phagocytosis was evaluated by flow cytometry. Macrophages were determined by morphology in the FSC-H and SSC-H dot plot. The expression of CD20 was evaluated in CLL cells by flow cytometry after 48 h of treatment with DMSO, R406 or GS-9973. Phagocytosis was also evaluated by confocal microscopy. To this aim, after the phagocytosis assay, macrophages were trypsinized, stained with anti-CD14-PE mAb and then centrifuged onto cytospin slides and coverslips were mounted using Fluoromount-G (Sigma). Immunofluorescence images were acquired with a FluoView FV1000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Tokio, Japan) using a Plapon 60 × 1.42 NA oil immersion objective, and images were analyzed using the Olympus FV10-ASW software.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined using the nonparametric tests: Friedman test followed by the Dunn's post test. In all cases, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism software version 6.01.

Results

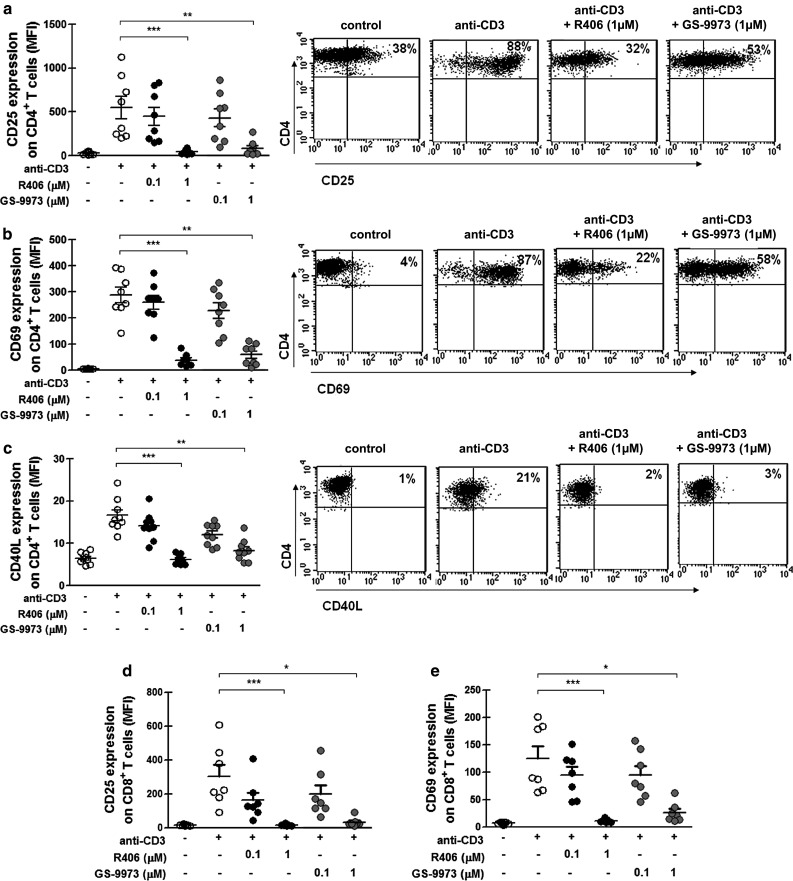

R406 and GS-9973 impair the expression of activation markers and cytokine-secretion in response to TCR/CD3 stimulation on T cells from CLL patients

To evaluate if the kinase inhibitors R406 and GS-9973 affect the activation of T cells, PBMC from CLL patients were cultured with immobilized anti-CD3 mAb in the presence of each inhibitor or vehicle (DMSO). The expression of the activation markers CD25, CD69 and CD40L was evaluated on T cell populations at 24 h by flow cytometry. Results from Fig. 1 show that the up-regulation of these markers induced by polyclonal activation of T cells was impaired by R406 or GS-9973 at 1 µM, which is a clinically relevant concentration for both drugs [16, 18], both in CD4+ (Fig. 1a–c) and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1d–e).

Fig. 1.

R406 and GS-9973 impair the expression of CD25, CD69 and CD40L on CD3-stimulated T cells from CLL patients. PBMC from CLL patients were pretreated with R406, GS-9973 or DMSO (vehicle) for 30 min and then transferred to a well with immobilized anti-CD3 mAb (0.15 µg/mL) or the corresponding isotype control antibody. After 24 h of culture, CD25, CD69 and CD40L expression on T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. a–c The figures show the values of the MFI of CD25, CD69 and CD40L on CD4+ T cells. Representative dot plots are shown. d–e The figures show the values of the MFI of CD25 and CD69 on CD8+ T cells. White circles correspond to DMSO-treated cells, black circles to R406-treated cells and gray circles to GS-9973-treated cells. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, Friedman test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison post test

Similar results were obtained when purified T cells instead of PBMC were used (Supplementary Fig. 1). Importantly, this inhibition was not due to a decrease in cell viability as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

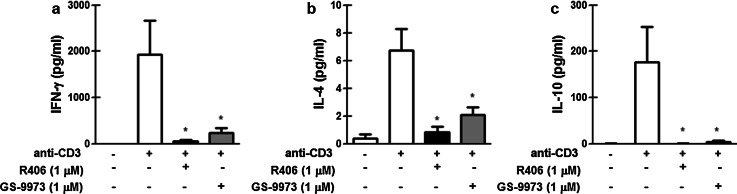

The secretion of cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-10) by anti-CD3-activated T cells from CLL patients was also impaired by R406 and GS-9973 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

R406 and GS-9973 impair INF-γ, IL-4 and IL-10 production by T cells from CLL patients. Purified T cells from CLL patients were pretreated with R406, GS-9973 or DMSO (vehicle) for 30 min and then transferred to a well with immobilized anti-CD3 mAb (0.15 µg/mL) or the corresponding isotype control antibody. After 24 h of culture, INF-γ (a), IL-4 (b) and IL-10 (c) were measured in culture supernatants by ELISA. Results are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), n = 8. *p < 0.05, significance was determined using Friedman test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison post test

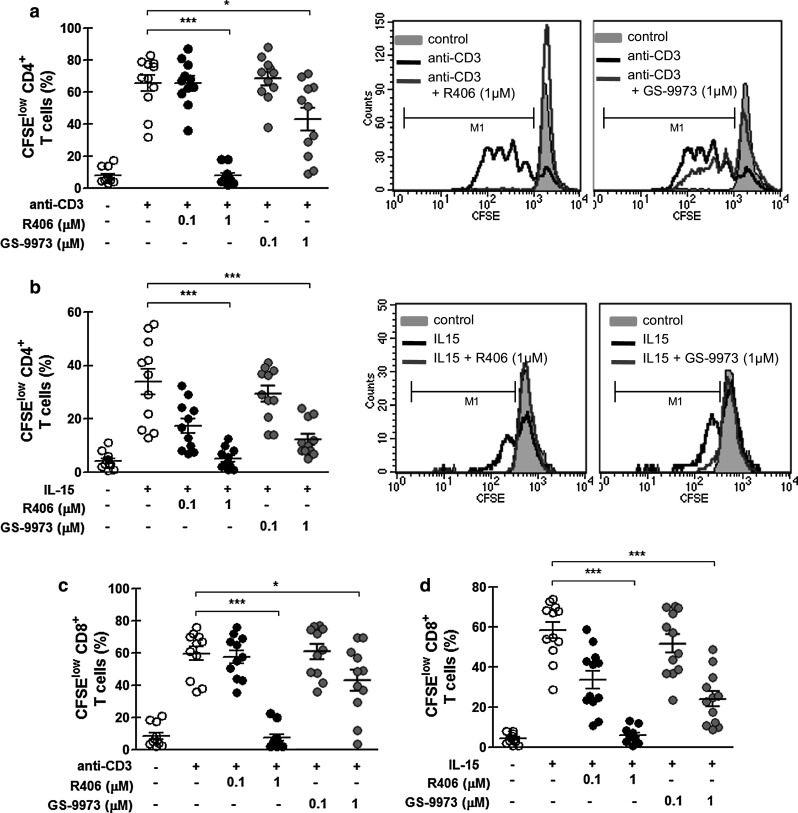

R406 and GS-9973 impair T cell proliferation in response to TCR/CD3 and IL-15 stimulation

To determine if R406 and GS-9973 were also able to inhibit T cell proliferation, PBMC from CLL patients were labeled with CSFE before activation on immobilized anti-CD3 as described above. As shown in Fig. 3a, c, both inhibitors impaired CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proliferation after 5 days in culture, without significant induction of apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. 3). Similar results were obtained when purified T cells instead of PBMC were used (Supplementary Fig. 4). Moreover, inhibition of both activation and proliferation was observed in CD3-stimulated T cells from age-matched healthy donors (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

R406 and GS-9973 impair the proliferation of T cells from CLL patients in response to TCR or IL-15 stimulation. PBMC from CLL patients were labeled with CFSE and then pretreated with R406, GS-9973 or DMSO (vehicle) for 30 min. Then, cells were transferred to a well with immobilized anti-CD3 mAb (0.3 µg/mL) or to a well containing IL-15 (20 ng/mL). After 5 days of culture, cells were collected, stained with specific mAb for CD4 (PeCy-5) or CD8 (PE) and then analyzed by flow cytometry. a–b The figures show the percentage of CFSElow CD4+ T cells from the total CD4+ viable lymphocytes, stimulated with anti-CD3 (a) or with IL-15 (b), histograms from representative experiments are shown. c–d The figures show the percentage of CFSElow CD8+ T cells from the total CD8+ viable lymphocytes, stimulated with anti-CD3 (c) or with IL-15 (d). White circles correspond to DMSO-treated cells, black circles to R406-treated cells and gray circles to GS-9973 treated cells. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, Friedman test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison post test

Also, R406 and GS-9973 inhibited T cell proliferation induced by IL-15 (Fig. 3b, d), a cytokine involved in the homeostatic proliferation of memory T cells [28, 29], indicating that the effect of these inhibitors on T lymphocytes is not restricted to TCR signaling.

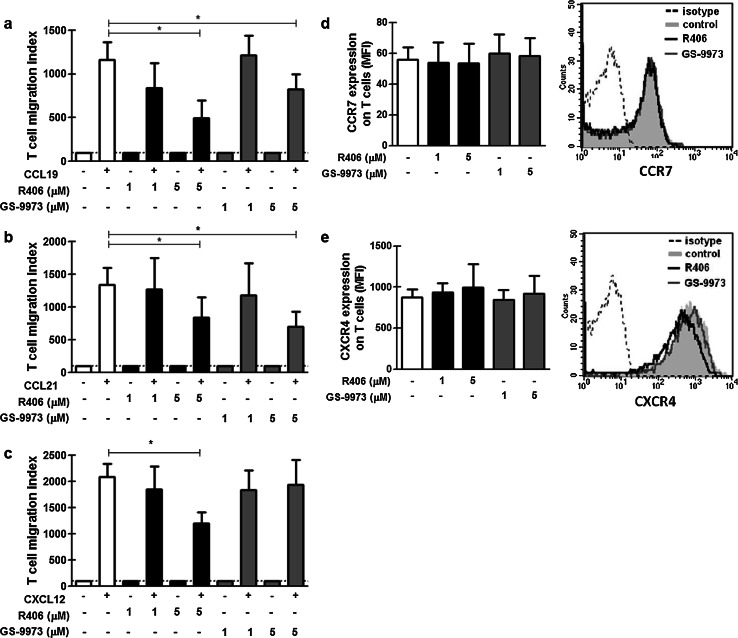

High doses of R406 and GS-9973 impair T cell migration in response to CCL21, CCL19 and CXCL12

Then we asked if R406 and GS-9973 could modify T cell response to chemokines that regulate their homing to lymphoid organs. To this aim, Transwell chemotaxis assays were performed as previously described [27] in the presence of different concentrations of R406, GS-9973 or the vehicle of the drugs. The chemotactic response of T cells (CD3+), expressed as T cell migration index, is depicted in Fig. 4. The concentrations of the chemokines used in this experiment were the optimal concentrations for the Transwell migration assay for T cells determined in previous studies [27]. We found that migration toward CCL19, CCL21 and CXCL12 was significantly reduced by 5 µM of R406, while GS-9973 5 µM only reduced the migration toward CCL19 and CCL21 (Fig. 4a–c). The inhibition was similar both in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (not shown). This effect was not due to a decrease in the expression of the chemokine receptors CCR7 and CXCR4 (Fig. 4d, e).

Fig. 4.

Effects of R406 and GS-9973 on T cell migration and on the expression of chemokine receptors. PBMC from CLL patients were pretreated with R406, GS-9973 or DMSO (vehicle) for 30 min. After, the migratory response toward CCL19 (a), CCL21 (b), CXCL12 (c) (1 µg/mL in RPMI 1640 1% FCS) was evaluated using the Transwell system assay. The figures show the percentage of T cell migration, calculated as the number of T cells that migrated in response to the chemokine over the number of T cells that migrated spontaneously. The expression of CCR7 (d) and CXCR4 (e) in T cells was evaluated by flow cytometry. Representative histograms are shown. Results are shown as the mean ± SEM, n = 10. *p < 0.05, Friedman test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison post test

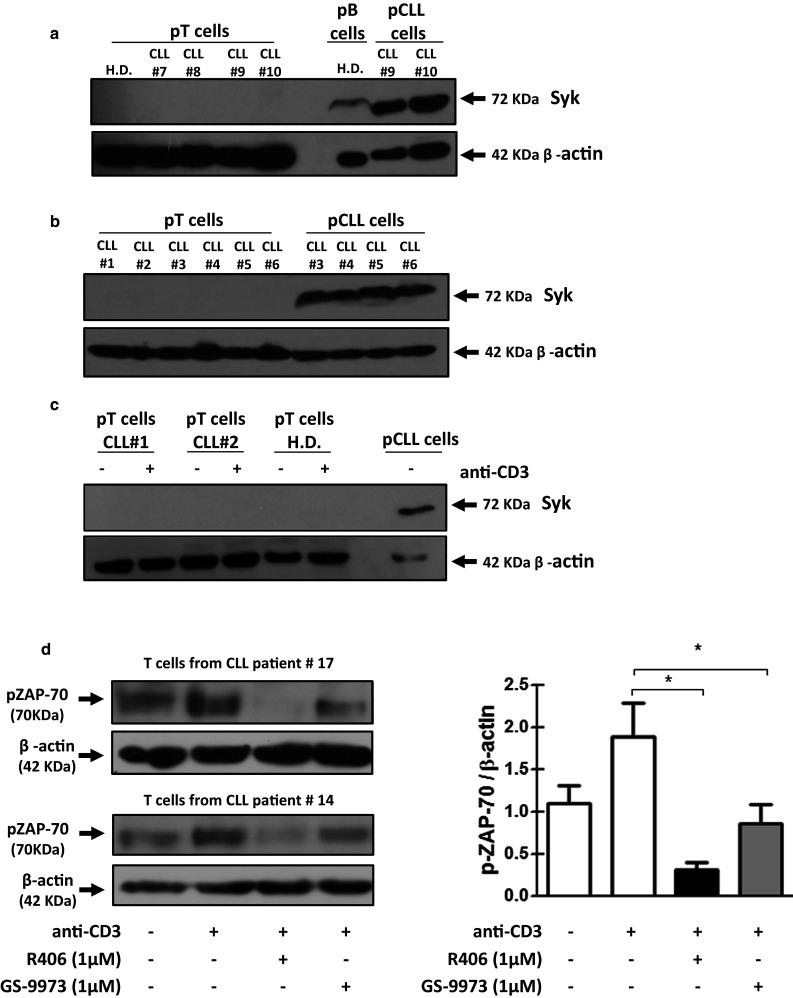

Syk is not expressed in T cells from CLL patients, and ZAP-70 phosphorylation is impaired by R406 and GS-9973 after TCR stimulation

Mature T cells from peripheral blood do not normally express Syk [30–32]. Nevertheless, Syk is expressed in T cells during ontogeny in the thymus [30] and also in mature T cells from systemic lupus erythematosus patients [33], T cell lymphomas [31] and patients with deficiencies in ZAP-70 [32, 34]. In those patients, Syk actively participates in the signal transduction through the TCR [33]. Given that R406 and GS-9973 are mainly selective for Syk, we evaluated the expression of this kinase in purified T cells from CLL patients by western blot. As shown in Fig. 5a we found, as previously described [35], high levels of Syk in B cells from CLL patients. On the contrary, Syk expression was not detected in either freshly isolated (Fig. 5a, b) or anti-CD3-activated (Fig. 5c) T cells from CLL patients. These results indicate that the effect of both R406 and GS-9973 inhibitors on T cell activation, proliferation and migration is due to the inhibition of kinase/s other than Syk. A previous report showed that concentrations of R406 between 0.4 and 2 µM were sufficient to inhibit ZAP-70 phosphorylation, a kinase involved in TCR signaling [12]. So, we evaluated the effect of R406 and GS-9973 on ZAP-70 phosphorylation after TCR stimulation in purified T cells from CLL patients and age-matched healthy donors. We found that both R406 and GS-9973 at 1 µM impaired ZAP-70 phosphorylation in TCR-stimulated T cells from CLL patients and healthy donors (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

CLL T cells do not express Syk by western blot, and ZAP-70 phosphorylation is diminished by R406 and GS-9973. a–b T cells from CLL patients and age-matched healthy donors were purified by positive selection using MACS, Miltenyi, MicroBeads kit (>97%). Purified T lymphocytes were used to obtain protein extracts, and subsequently the expression of Syk was evaluated by western blot. c T cells were purified by negative selection using a BD FACS Aria II Cell sorter cytometer (>97%) from PBMC from CLL patients and age-matched healthy donors and then cultured with plate-bound anti-CD3 mAb (0.3 µg/mL). After 5 days of culture, Syk expression was evaluated by western blot. Purified CLL cells were used as positive control and β-actin as charge control. d T cells from CLL patients were purified by negative selection using a BD FACS Aria II Cell sorter cytometer (>97%). Then, T cells were pretreated for 30 min with DMSO, R406 or GS-9973 (1 µM) and then stimulated for 5 min with soluble anti-CD3/anti-CD28 mAbs. Then, phospho-ZAP-70 expression was evaluated by western blot. Specific bands were developed by ECL. Western blots results from patients #17 and 14 are shown. Bands on the immunoblots were quantified using the ImageJ software (NIH Image). H.D.: healthy donors. Results are shown as the mean ± SEM of the ratio pZAP-70/β-actin, n = 5. *p < 0.05, Friedman test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison post test

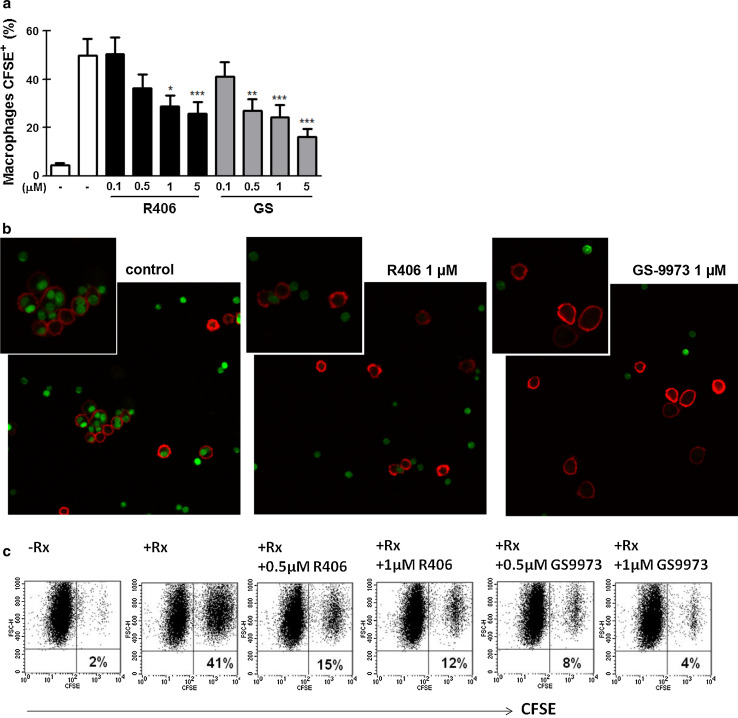

R406 and GS-9973 impair macrophage-mediated phagocytosis of rituximab-coated CLL cells

Anti-CD20 mAb are part of the current standard therapy for CLL patients [36]. The chemoimmunotherapy including fludarabine (a purine analog), cyclophosphamide (an alkylating agent) and rituximab (an anti-CD20 mAb) is the standard first-line treatment for patients with good physical condition. A combination with an anti-CD20 mAb together with chlorambucil (an alkylating agent) is usually applied to non-fit patients given its lower toxicity [36]. Thus, considering that Syk participates in the signaling through Fcγ receptors in myeloid cells [37], we tested the ability of R406 and GS-9973 to impair macrophage-mediated phagocytosis of rituximab-coated CLL cells, which is known to be a central mechanism in the anti-tumor activity of anti-CD20 antibodies [22, 23]. To this aim, human macrophages were differentiated from healthy donors’ monocytes by incubation with M-CSF (50 ng/mL) for 5 days. Then, the phagocytosis assay of CFSE-labeled rituximab-coated CLL cells was performed as previously described [20] in the presence or absence of R406 or GS-9973. Uptake of CFSE-CLL cells was evaluated by flow cytometry and confocal microscopy. As shown in Fig. 6a, b, both R406 and GS-9973, at clinically relevant concentrations, impaired macrophage phagocytosis of rituximab-coated CLL cells. This inhibitory effect was also observed on macrophages differentiated from CLL samples (n = 8, p < 0.05 for 1 and 0.5 µM for R406 and GS-9973, respectively, Friedman test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison post test). Dot plots from a representative experiment are shown in Fig. 6c.

Fig. 6.

R406 and GS-9973 impair rituximab (Rx)-coated CLL cells phagocytosis by human macrophages. a Human macrophages were obtained by culturing monocytes from healthy donor’s peripheral blood for 5 days in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS and M-CSF (50 ng/mL) in a 48 well-plate. At day five, human macrophages were treated for 30 min with R406, GS-9973 or DMSO (vehicle) and then CLL cells, that were previously labeled with CFSE (1 µM) and coated or not with Rx (50 µg/mL), were added to the culture. After 2 h, macrophages were trypsinized and evaluated by flow cytometry and phagocytosis was calculated as the percentage of CFSE+ macrophages. Results are shown as the mean ± SEM, n = 10. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, Friedman test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison post test. b Macrophages were stained with anti-CD14-PE mAb, and preparations were analyzed by confocal microscopy. 3 × magnification from the original images is shown in the insert. Representative images of the experiment are shown. c The same phagocytosis experiment was performed using macrophages differentiated from CLL patients’ monocytes. Representative dot plots are shown

In addition, we found that R406 induced a slight downregulation of CD20 expression on CLL cells, confirming a previous report [38], while GS-9973 had no effect (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Discussion

In the last few years, small-molecule inhibitors of kinases involved in BCR signaling have been developed and tested for the treatment of patients with B cell malignancies [39]. Among them, the Btk inhibitor ibrutinib and the PI3Kδ inhibitor idelalisib were approved for the treatment of CLL patients in 2014, the first as monotherapy and the second in combination with rituximab, and have generated great expectation for these and other kinase inhibitors due to the manageable toxicity profile and encouraging clinical effectiveness observed with these agents [39].

Although most of preclinical studies of BCR-associated kinases inhibitors in CLL have focused on their effects on patient’s malignant B cells, it is now becoming evident that these inhibitors also affect other immune cells in CLL patients. Thus, ibrutinib affects functions on T cells [19], NK cells [40] and macrophages [20, 21] by targeting other kinase/s different from Btk. Also, idelalisib alters cytokine production by T and NK cells [41] and phagocytosis by myeloid cells [21].

In this study we found that the kinase inhibitors R406 and GS-9973 significantly impair the activation and proliferation of T cells from CLL patients in response to TCR stimulation or IL-15. Likewise, both inhibitors markedly decrease the expression of CD40L and the secretion of IL-4 and IFN-γ, key molecules for CLL-B cell survival and growth. Given the relevance of activated T cells to support CLL progression, our results suggest that R406 and GS-9973 may be successful in the treatment of CLL patients because of their effect not only on the malignant B cell clone but also on T cells from the supportive microenvironment.

Although R406 and GS-9973 have been developed as Syk inhibitors, their effects on T cells described in the present report could not be ascribed to Syk. Indeed, we found that neither freshly isolated nor activated T cells from CLL patients express Syk. Although we do not know the specific target/s of these inhibitors on T cells, it has been reported that concentrations of R406 between 0.4 and 2 µM are sufficient to inhibit other kinases such as Lck, which is responsible for ZAP-70 phosphorylation on T cells in response to TCR stimulation [12]. GS-9973, although it was described to be a more selective inhibitor for Syk than R406, can also inhibit Lck and ZAP-70 at higher concentrations [17]. In this work we found that ZAP-70 phosphorylation was impaired by 1 µM of R406 and GS-9973 on T cells from CLL patients and healthy donors upon TCR stimulation, suggesting that Lck activity might be impaired at that concentration of the drugs. Importantly, patients treated with these agents achieve a peak plasma concentration of 1.6 µM for R406 [16] and 3.6 µM for GS-9973 [18], so it is possible that multiple kinases might be affected during therapy.

The strong impairment in T cell functions induced by R406 and GS-9973 described here might be particularly detrimental in CLL patients given their known susceptibility to infections and the requirement for long-term therapy with kinase inhibitors [42]. At the moment, there is no clear evidence showing that these drugs enhance the susceptibility to infections in CLL patients. However, it is possible that long-term effects on T cell functions are not evident in the published trials’ results with R406 and GS-9973 in CLL patients given their short time of follow-up [16, 18]. Nevertheless, during a Phase II study of R406 in rheumatoid arthritis patients, an increased incidence of upper respiratory tract infections, not associated with neutropenia, was reported [43]. Remarkably, a Phase II trial combining GS-9973 and idelalisib was halted due to a high incidence of pneumonitis [44]. The immune defect responsible for this observation was not determined yet. And, although pneumonitis was already described in patients treated with idelalisib and inhibition of regulatory T cells by this drug seems to be involved [45], it is possible that an immune defect caused by the decrease in T cell function due to GS-9973 could also be responsible for the high incidence of pneumonitis observed in the combinatory treatment. Results from the ongoing trials with GS-9973 in CLL patients with longer periods of follow-up will probably help to clarify this point.

Finally, it is well known that Syk participates in Fc receptor signaling as demonstrated by the fact that murine macrophages deficient for Syk are unable to phagocyte IgG-coated particles [46]. Accordingly, we observed that R406 and GS-9973 impaired macrophage phagocytosis of rituximab-coated CLL cells, suggesting that Syk inhibitors should not be administrated concomitant with mAb targeting CLL cells to preserve their efficacy.

Overall, in this work we have shown that R406 and GS-9973 have strong effects on T cell and macrophage functions and that this must be considered in long-term therapies with these drugs and in combinatory treatment with mAbs.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from Fondo para la Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (PICT 1074/2013 and PICT 1310/2012), Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, Argentina. We are indebted to Beatriz Loria, María Tejeda and Federico Fuentes for their technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- BCR

B cell receptor

- Btk

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase

- CD40L

CD40 ligand

- CFSE

Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester

- CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- ECL

Enhanced chemiluminescence

- Flt3

Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3

- Lck

Lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase

- M-CSF

Macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- Rx

Rituximab

- pAb

Polyclonal antibodies

- PVDF

Polyvinylidene difluoride

- SEM

Standard error of the mean

- Syk

Spleen tyrosine kinase

- Th

T helper

- ZAP-70

ζ-chain-associated protein kinase-70

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Romina Gamberale had received compensation as speaker for Janssen and Bristol-Myers Squibb, as speaker and consultant for Roche, and as a member of the advisory board of AbbVie. Raimundo Fernando Bezares had received compensation as speaker from Novartis, Varifarma and Roche. All the other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- 1.Soma LA, Craig FE, Swerdlow SH. The proliferation center microenvironment and prognostic markers in chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(2):152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosati S, Kluin PM. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a review of the immuno-architecture. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;294:91–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Audrito V, Vaisitti T, Serra S, Bologna C, Brusa D, Malavasi F, Deaglio S. Targeting the microenvironment in chronic lymphocytic leukemia offers novel therapeutic options. Cancer Lett. 2013;328(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagnara D, Kaufman MS, Calissano C, Marsilio S, Patten PE, Simone R, Chum P, Yan XJ, Allen SL, Kolitz JE, Baskar S, Rader C, Mellstedt H, Rabbani H, Lee A, Gregersen PK, Rai KR, Chiorazzi N. A novel adoptive transfer model of chronic lymphocytic leukemia suggests a key role for T lymphocytes in the disease. Blood. 2011;117(20):5463–5472. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-324210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghia P, Strola G, Granziero L, Geuna M, Guida G, Sallusto F, Ruffing N, Montagna L, Piccoli P, Chilosi M, Caligaris-Cappio F. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells are endowed with the capacity to attract CD4+, CD40L+ T cells by producing CCL22. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32(5):1403–1413. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200205)32:5<1403::AID-IMMU1403>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Granziero L, Ghia P, Circosta P, Gottardi D, Strola G, Geuna M, Montagna L, Piccoli P, Chilosi M, Caligaris-Cappio F. Survivin is expressed on CD40 stimulation and interfaces proliferation and apoptosis in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2001;97(9):2777–2783. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.9.2777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmid C, Isaacson PG. Proliferation centres in B-cell malignant lymphoma, lymphocytic (B-CLL): an immunophenotypic study. Histopathology. 1994;24(5):445–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1994.tb00553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patten PE, Buggins AG, Richards J, Wotherspoon A, Salisbury J, Mufti GJ, Hamblin TJ, Devereux S. CD38 expression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia is regulated by the tumor microenvironment. Blood. 2008;111(10):5173–5181. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-108605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crawford DH, Catovsky D. In vitro activation of leukaemic B cells by interleukin-4 and antibodies to CD40. Immunology. 1993;80(1):40–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buschle M, Campana D, Carding SR, Richard C, Hoffbrand AV, Brenner MK. Interferon gamma inhibits apoptotic cell death in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Exp Med. 1993;177(1):213–218. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.1.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiaii S, Kokhaei P, Mozaffari F, Rossmann E, Pak F, Moshfegh A, Palma M, Hansson L, Mashayekhi K, Hojjat-Farsangi M, Österborg A, Choudhury A, Mellstedt H. T cells from indolent CLL patients prevent apoptosis of leukemic B cells in vitro and have altered gene expression profile. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62(1):51–63. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1300-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braselmann S, Taylor V, Zhao H, Wang S, Sylvain C, Baluom M, Qu K, Herlaar E, Lau A, Young C, Wong BR, Lovell S, Sun T, Park G, Argade A, Jurcevic S, Pine P, Singh R, Grossbard EB, Payan DG, Masuda ES. R406, an orally available spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor blocks fc receptor signaling and reduces immune complex-mediated inflammation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319(3):998–1008. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.109058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gobessi S, Laurenti L, Longo PG, Carsetti L, Berno V, Sica S, Leone G, Efremov DG. Inhibition of constitutive and BCR-induced Syk activation downregulates Mcl-1 and induces apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Leukemia. 2009;23(4):686–697. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchner M, Baer C, Prinz G, Dierks C, Burger M, Zenz T, Stilgenbauer S, Jumaa H, Veelken H, Zirlik K. Spleen tyrosine kinase inhibition prevents chemokine- and integrin-mediated stromal protective effects in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115(22):4497–4506. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-233692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suljagic M, Longo PG, Bennardo S, Perlas E, Leone G, Laurenti L, Efremov DG. The Syk inhibitor fostamatinib disodium (R788) inhibits tumor growth in the Emu-TCL1 transgenic mouse model of CLL by blocking antigen-dependent B-cell receptor signaling. Blood. 2010;116(23):4894–4905. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-275180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedberg JW, Sharman J, Sweetenham J, Johnston PB, Vose JM, Lacasce A, Schaefer-Cutillo J, De Vos S, Sinha R, Leonard JP, Cripe LD, Gregory SA, Sterba MP, Lowe AM, Levy R, Shipp MA. Inhibition of Syk with fostamatinib disodium has significant clinical activity in non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115(13):2578–2585. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-236471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Currie KS, Kropf JE, Lee T, Blomgren P, Xu J, Zhao Z, Gallion S, Whitney JA, Maclin D, Lansdon EB, Maciejewski P, Rossi AM, Rong H, Macaluso J, Barbosa J, Di Paolo JA, Mitchell SA. Discovery of GS-9973, a selective and orally efficacious inhibitor of spleen tyrosine kinase. J Med Chem. 2014;57(9):3856–3873. doi: 10.1021/jm500228a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharman J, Hawkins M, Kolibaba K, Boxer M, Klein L, Wu M, Hu J, Abella S, Yasenchak C. An open-label phase 2 trial of entospletinib (GS-9973), a selective spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2015;125(15):2336–2343. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-595934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubovsky JA, Beckwith KA, Natarajan G, Woyach JA, Jaglowski S, Zhong Y, Hessler JD, Liu TM, Chang BY, Larkin KM, Stefanovski MR, Chappell DL, Frissora FW, Smith LL, Smucker KA, Flynn JM, Jones JA, Andritsos LA, Maddocks K, Lehman AM, Furman R, Sharman J, Mishra A, Caligiuri MA, Satoskar AR, Buggy JJ, Muthusamy N, Johnson AJ, Byrd JC. Ibrutinib is an irreversible molecular inhibitor of ITK driving a Th1-selective pressure in T lymphocytes. Blood. 2013;122(15):2539–2549. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-507947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borge M, Belen Almejun M, Podaza E, Colado A, Fernandez Grecco H, Cabrejo M, Bezares RF, Giordano M, Gamberale R. Ibrutinib impairs the phagocytosis of rituximab-coated leukemic cells from chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients by human macrophages. Haematologica. 2015;100(4):e140–e142. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.119669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Da Roit F, Engelberts PJ, Taylor RP, Breij EC, Gritti G, Rambaldi A, Introna M, Parren PW, Beurskens FJ, Golay J. Ibrutinib interferes with the cell-mediated anti-tumour activities of therapeutic CD20 antibodies: implications for combination therapy. Haematologica. 2014;100(1):77–86. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.107011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montalvao F, Garcia Z, Celli S, Breart B, Deguine J, Van Rooijen N, Bousso P. The mechanism of anti-CD20-mediated B cell depletion revealed by intravital imaging. J Clin Investig. 2013;123(12):5098–5103. doi: 10.1172/JCI70972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uchida J, Hamaguchi Y, Oliver JA, Ravetch JV, Poe JC, Haas KM, Tedder TF. The innate mononuclear phagocyte network depletes B lymphocytes through Fc receptor-dependent mechanisms during anti-CD20 antibody immunotherapy. J Exp Med. 2004;199(12):1659–1669. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leonhardt F, Zirlik K, Buchner M, Prinz G, Hechinger AK, Gerlach UV, Fisch P, Schmitt-Graff A, Reichardt W, Zeiser R. Spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) is a potent target for GvHD prevention at different cellular levels. Leukemia. 2012;26(7):1617–1629. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Platt AM, Benson RA, McQueenie R, Butcher JP, Braddock M, Brewer JM, McInnes IB, Garside P. The active metabolite of spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor fostamatinib abrogates the CD4(+) T cell-priming capacity of dendritic cells. Rheumatology. 2015;54(1):169–177. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chattopadhyay PK, Yu J, Roederer M. Live-cell assay to detect antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell responses by CD154 expression. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(1):1–6. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borge M, Nannini PR, Galletti JG, Morande PE, Avalos JS, Bezares RF, Giordano M, Gamberale R. CXCL12-induced chemotaxis is impaired in T cells from patients with ZAP-70-negative chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2010;95(5):768–775. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.013995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geginat J, Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Cytokine-driven proliferation and differentiation of human naive, central memory and effector memory CD4+ T cells. Pathol Biol. 2003;51(2):64–66. doi: 10.1016/S0369-8114(03)00098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geginat J, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Proliferation and differentiation potential of human CD8 + memory T-cell subsets in response to antigen or homeostatic cytokines. Blood. 2003;101(11):4260–4266. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palacios EH, Weiss A. Distinct roles for Syk and ZAP-70 during early thymocyte development. J Exp Med. 2007;204(7):1703–1715. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feldman AL, Sun DX, Law ME, Novak AJ, Attygalle AD, Thorland EC, Fink SR, Vrana JA, Caron BL, Morice WG, Remstein ED, Grogg KL, Kurtin PJ, Macon WR, Dogan A. Overexpression of Syk tyrosine kinase in peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Leukemia. 2008;22(6):1139–1143. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noraz N, Schwarz K, Steinberg M, Dardalhon V, Rebouissou C, Hipskind R, Friedrich W, Yssel H, Bacon K, Taylor N. Alternative antigen receptor (TCR) signaling in T cells derived from ZAP-70-deficient patients expressing high levels of Syk. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(21):15832–15838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M908568199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krishnan S, Juang YT, Chowdhury B, Magilavy A, Fisher CU, Nguyen H, Nambiar MP, Kyttaris V, Weinstein A, Bahjat R, Pine P, Rus V, Tsokos GC. Differential expression and molecular associations of Syk in systemic lupus erythematosus T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181(11):8145–8152. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.8145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hauck F, Blumenthal B, Fuchs S, Lenoir C, Martin E, Speckmann C, Vraetz T, Mannhardt-Laakmann W, Lambert N, Gil M, Borte S, Audrain M, Schwarz K, Lim A, Schamel WW, Fischer A, Ehl S, Rensing-Ehl A, Picard C, Latour S. SYK expression endows human ZAP70-deficient CD8 T cells with residual TCR signaling. Clin Immunol. 2015;161(2):103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buchner M, Fuchs S, Prinz G, Pfeifer D, Bartholome K, Burger M, Chevalier N, Vallat L, Timmer J, Gribben JG, Jumaa H, Veelken H, Dierks C, Zirlik K. Spleen tyrosine kinase is overexpressed and represents a potential therapeutic target in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2009;69(13):5424–5432. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hallek M. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 2015 Update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(5):446–460. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mocsai A, Ruland J, Tybulewicz VL. The SYK tyrosine kinase: a crucial player in diverse biological functions. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(6):387–402. doi: 10.1038/nri2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bojarczuk K, Siernicka M, Dwojak M, Bobrowicz M, Pyrzynska B, Gaj P, Karp M, Giannopoulos K, Efremov DG, Fauriat C, Golab J, Winiarska M. B-cell receptor pathway inhibitors affect CD20 levels and impair antitumor activity of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies. Leukemia. 2014;28(5):1163–1167. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jain N, O’Brien S. Targeted therapies for CLL: practical issues with the changing treatment paradigm. Blood Rev. 2015;30(3):233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kohrt HE, Sagiv-Barfi I, Rafiq S, Herman SE, Butchar JP, Cheney C, Zhang X, Buggy JJ, Muthusamy N, Levy R, Johnson AJ, Byrd JC. Ibrutinib antagonizes rituximab-dependent NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Blood. 2014;123(12):1957–1960. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-547869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herman SE, Gordon AL, Wagner AJ, Heerema NA, Zhao W, Flynn JM, Jones J, Andritsos L, Puri KD, Lannutti BJ, Giese NA, Zhang X, Wei L, Byrd JC, Johnson AJ. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-delta inhibitor CAL-101 shows promising preclinical activity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia by antagonizing intrinsic and extrinsic cellular survival signals. Blood. 2010;116(12):2078–2088. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-271171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ravandi F, O’Brien S. Immune defects in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55(2):197–209. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0015-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weinblatt ME, Kavanaugh A, Genovese MC, Musser TK, Grossbard EB, Magilavy DB. An oral spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) inhibitor for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(14):1303–1312. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barr PM, Saylors GB, Spurgeon SE, Cheson BD, Greenwald DR, O’Brien SM, Liem AK, Mclntyre RE, Joshi A, Abella-Dominicis E, Hawkins MJ, Reddy A, Di Paolo J, Lee H, He J, Hu J, Dreiling LK, Friedberg JW. Phase 2 study of idelalisib and entospletinib: pneumonitis limits combination therapy in relapsed refractory CLL and NHL. Blood. 2016;127(20):2411–2415. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-12-683516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okkenhaug K, Burger JA. PI3 K Signaling in Normal B Cells and Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2016;393:123–142. doi: 10.1007/82_2015_484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiefer F, Brumell J, Al-Alawi N, Latour S, Cheng A, Veillette A, Grinstein S, Pawson T. The Syk protein tyrosine kinase is essential for Fc gamma receptor signaling in macrophages and neutrophils. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(7):4209–4220. doi: 10.1128/MCB.18.7.4209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.