Abstract

The ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73 degrade immune stimulatory ATP to adenosine that inhibits T and NK cell responses via the A2A adenosine receptor (ADORA2A). This mechanism is used by regulatory T cells (Treg) that are associated with increased mortality in OvCA. Immunohistochemical staining of human OvCA tissue specimens revealed further aberrant expression of CD39 in 29/36 OvCA samples, whereas only 1/9 benign ovaries showed weak stromal CD39 expression. CD73 could be detected on 31/34 OvCA samples. While 8/9 benign ovaries also showed CD73 immunoreactivity, expression levels were lower than in tumour specimens. Infiltration by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was enhanced in tumour specimens and significantly correlated with CD39 and CD73 levels on stromal, but not on tumour cells. In vitro, human OvCA cell lines SK-OV-3 and OaW42 as well as 11/15 ascites-derived primary OvCA cell cultures expressed both functional CD39 and CD73 leading to more efficient depletion of extracellular ATP and enhanced generation of adenosine as compared to activated Treg. Functional assays using siRNAs against CD39 and CD73 or pharmacological inhibitors of CD39, CD73 and ADORA2A revealed that tumour-derived adenosine inhibits the proliferation of allogeneic human CD4+ T cells in co-culture with OvCA cells as well as cytotoxic T cell priming and NK cell cytotoxicity against SK-OV3 or OAW42 cells. Thus, both the ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73 and ADORA2A appear as possible targets for novel treatments in OvCA, which may not only affect the function of Treg but also relieve intrinsic immunosuppressive properties of tumour and stromal cells.

Keywords: Ovarian cancer, Immune escape, Adenosine, CD39, CD73

Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OvCA) is burdened with the most unfavourable prognosis of all gynaecological malignancies [1]. Although the introduction of platinum-based chemotherapy yielded a moderate benefit, the 5-year survival rate still does not exceed 20–40% [2]. Therefore, new potential targets for novel therapeutic approaches have to be identified for this tumour entity. Recent findings suggest that tumour immune escape is clinically relevant in OvCA [3]. Thus, an increased number of intratumoural regulatory T cells (Treg), which are able to suppress the host’s immune response to tumour antigens, are associated with a significantly higher mortality [3].

Elevated adenosine concentrations have also been reported in the microenvironment of some tumours [4]. A recent study has shown that adenosine mediates immunosuppressive effects via the A2A adenosine receptor (ADORA2A) [5] on immune cells, which acts by stimulating adenylate cyclase activity [6]. Recently, several independent groups demonstrated that CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg express CD39/ENTPD1 and CD73/ecto-5′-nucleotidase [7, 8]. CD39 hydrolyses extracellular adenosine tri- and diphosphate (ATP/ADP) to adenosine monophosphate (AMP) [8], which is in turn dephosphorylated by CD73 [9]. The resulting adenosine acts to suppress, among others, TH1, TH2 [10], CTL, and NK cells [8]. Moreover, ATP, which has been shown to attract antigen-presenting cells [11] and to promote the priming of anticancer immune responses [12], is depleted. In the tumour context, aberrant expression of CD39 has already been described for pancreatic cancer [13], melanoma [14] and small cell lung carcinoma [15], but its functional role in these malignancies is still poorly understood. In gliomas, where the role of ATP-degrading ectoenzymes has been studied in some detail, tumour growth was inhibited by co-injection of apyrase during tumour inoculation, most likely due to an inhibitory effect on vascularisation [16]. Stable overexpression of NTPDase2 in C6 glioma cells, however, increased tumour growth and malignant characteristics in vivo dramatically, even though it showed no tumour cell-intrinsic effects in vitro [17]. CD73 and extracellular adenosine can, in contrast, stimulate tumour cell proliferation [18], adhesion, chemotaxis and metastasis [19, 20], mostly via ADORA2B on cancer cells. Nevertheless, recent data [19] which show that CD73 on murine breast cancer cells exerts strong tumour-promoting effects in immunocompetent, but not in severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice suggest that ADORA2A-dependent immunomodulatory effects predominate in vivo [21].

These findings prompted us to investigate the expression and putative immunosuppressive function of CD39 and CD73 in human OvCA specimens ex vivo and cell lines in vitro.

Materials and methods

Immunohistochemical staining

All tissue specimens were provided by the tumour bank of the University Hospital Würzburg (Würzburg, Germany). Samples had been evaluated by at least two pathologists in routine diagnostics as serous papillary OvCA or benign ovaries. Histological criteria used for the morphological identification of serous papillary carcinomas included cellular atypias (e.g. altered nucleus–cytoplasm ratio or prominent nucleoli), (micro) papillary ‘lacy’ patterns consisting of almost uniform cells partly with cystic spaces (depending on the grading) and stromal infiltration. Paraffin-embedded tissue samples were cut at 2 μm, deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated in a descending alcohol sequence. Antigens were unmasked in TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 9.0) in a steamer. Endogenous peroxidases were left to react with 3% H2O2 in methanol for 10 min. After washing with PBS, slides were incubated for 1 h with antibody in diluent (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Rabbit anti-human CD73 HPA017357 (Atlas, Uppsala, Sweden) was used at 1:1000. The monoclonal mouse anti-human IgG antibodies used were ab49580 anti-CD39 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, 1:200), 4B12 anti-CD4 (Novocastra, Newcastle, UK, 1:250), C8/144B anti-CD8 (Dako, 1:400), eBio7979 anti-FoxP3 (eBioscience, San Diego, USA, 1:100). Biotinylated anti-mouse immunoglobulins and HRP-conjugated streptavidin (both from Dako) were used according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Cryosections (4 μm) were fixed with acetone, rehydrated with TBS buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5), blocked with 10% goat serum, treated with 3% H2O2 and incubated for 3 h with mouse anti-human CD73 (sc-32299, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, USA) diluted in commercial Antibody diluent (Dako). Following a secondary biotinylated anti-mouse IgG (81-6540, Zymed, San Francisco, USA), HRP-conjugated streptavidin (Lsa 1007, Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, USA) was used.

Staining were developed for 15 min with diaminobenzidine (Dako). Nuclei were counterstained with haematoxylin. After dehydration, sections were embedded in Harleco Aquatex Mounting Media (Voigt, Lawrence, USA).

For immunohistochemical double staining, anti-CD39 and anti-CD73 immunoreactivity were detected using Alexa555-labelled anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG (as appropriate, both from Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany), while the biotinylated mouse anti-human CD326 (EpCAM) BLD-324216 was applied at 1:40 and visualised with Dylight™488-conjugated Streptavidin (both from Biolegend, San Diego, USA). Confocal pictures were recorded with the Olympus FluoViewTM FV1000 confocal microscope with three channel detectors.

Cell culture

The OvCA cell lines SK-OV-3 and OAW42 were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FCS, 0.02% sodium pyruvate, penicillin (100 IU/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (all from PAA, Pasching, Austria). Cell line identity was confirmed via the single tandem repeat fingerprint system performed by the Deutsche Sammlung für Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (Braunschweig, Germany). Expression of adenosine receptors on these cells was characterised using radioactive ligand binding and adenylate cyclase assays as described in [22]. Primary OvCA cells (named A1-15) were isolated from ascites from 15 different OvCA patients using the CD326/EpCAM-specific Tumour Cell Enrichment and Detection Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Ascitic fluid punctures were performed for medical needs. Investigation into the obtained tumour material was approved by the local ethics committee.

For RNA interference, 10 nmol/l of either CD39 siRNA (target sequence: 5′-GGGCAAAUUCAGUCAGAAA-3′), CD73 siRNA (target sequence 5′-GCCACUAGCAUCUCAAAUA-3′) or an irrelevant control (all from Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA) were transfected using Lipofectamine(tm) RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA). Stable pSUPERpuro shRNA constructs targeting the same sequences were cloned and transfected as previously described [23].

Flow cytometric analysis

OvCA cells (106/sample) were detached with Accutase (PAA), blocked and stained with A1 anti-human CD39-PE/Cy7 [24] or AD2 anti-human CD73-APC antibody (both from BioLegend, San Diego, USA) [25].

Density gradient centrifugation (Biocoll, Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) was used to isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from healthy volunteers. PBMC were stained with polyclonal rabbit anti-human adenosine 2a (A2a)-receptor (ADORA2A) antiserum (ab3461, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) [26] and visualised with FITC-labelled goat anti-rabbit IgG (4030-2, SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, USA). Cell types were identified by co-staining with anti-CD3-PE/Cy5 (clone MEM-57), anti-human CD4-PE (MEM-241), CD8-PE (MEM-31) and CD56-PE (MEM-188, all ImmunoTools, Friesoythe, Germany) and analysed on a FACScan flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, USA). Specific fluorescence indices (SFI) indicate the ratio of signal intensities obtained with specific and irrelevant isotype-matched control antibody.

ATP degradation and adenosine production via CD39 and CD73

ATP concentrations in supernatant were determined using the firefly luciferin-luciferase system [27]. Briefly, 104 cells/well were seeded. After adherence overnight, the medium was replaced with 100 μl fresh RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS and the indicated concentration of inhibitors and ATP. Twenty-four hour later, 50 μl of supernatant were collected and measured by addition of 50 μl ATP assay buffer (pH 7.8) containing 300 μM D-Luciferin, 5 μg/ml Firefly Luciferase, 75 μM Dithiothreitol, 25 mM HEPES, 6,25 mM MgCl2, 0.63 mM EDTA and 1 mg/ml BSA. Adenosine generation was quantified as described in [28]. ADORA2A-overexpressing HEK-293 cells were transiently transfected with the luciferase-encoding RIP1-CRE.luc+ cAMP-reporter plasmid. Transfection efficiency was normalised by co-transfer of pRL-CMV (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Binding of paracrine adenosine to ADORA2A activates adenylate cyclase and thus the inducible firefly luciferase signal. About 104 cells of interest were co-incubated with equal numbers of RIP1-CRE.luc- and pRL-CMV-transfected HEK-293 ADORA2A+/− cells for 4 h. Cells were lysed in passive lysis buffer (Promega), and the biophotonic signals were quantified in an Orion II Microplate Luminometer (Berthold Detection Systems, Pforzheim, Germany), using a non-commercial dual luciferase assay [29]. All values were measured in triplicate and controlled for specificity by addition of the specific inhibitors ARL67156 [30] for CD39 (100 μM) (Tocris, Bristol, UK) and α,β-methyleneadenosine-5′-diphosphate (APCP) [31] (100 μM) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). The corresponding adenosine or ATP concentrations were calculated using a co-determined standard curve ranging from 20 nM to 40 μM adenosine or 0.1 nM to 10 μM ATP.

Proliferation of CD4+ T cells in co-culture with adenosine-generating cells

CD4+, CD4+ CD25high and CD4+ CD25− T cells were isolated from PBMC using the CD4+ T cell isolation kit II or the CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cell isolation kit (both from Miltenyi Biotec). T cells were labelled with 2.5 μM 5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFDA-SE, Invitrogen) or Cell Proliferation Dye (CPD) eFluor® 670 (eBioscience). Anti-human CD3 (clone UCHT-1) and anti-human CD28 (clone 15E8, both ImmunoTools) antibodies were immobilized on 96-well Maxisorp-plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) by overnight incubation in PBS (antibodies used at 1 μg/ml). In each well, 2 × 106 T cells were co-incubated with 5x105 SK-OV-3 or OAW42 cells in the absence or presence of the specific inhibitors ARL67156 for CD39 (100 μM), αβ-methyleneadenosine-5′-diphosphate (APCP 100 μM) for CD73 or the ADORA2A antagonist SCH58261 [32] (100 nM, Tocris), respectively. The metabolically stable adenosine receptor agonist adenosine-5′-N-ethylcarboxamide (NECA, Tocris) was used at 10 μM. DMSO was included as solvent control. Proliferation was measured using a FACScan flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) on day 7.

NK cell preparation and cytotoxicity assays

Polyclonal NK cell cultures yielding 70–90% pure CD3−CD56+ cells were obtained by co-culturing human peripheral blood lymphocytes with irradiated (30 Gy) RPMI 8866 feeder cells [23]. NK cells were labelled with PKH-26 (Sigma–Aldrich). The lytic activity against CFDA-SE+ (2.5 μM, Invitrogen) target cells (50.000 target cells/well) was determined in modified 4 h FATAL assays [23]. To block CD39, CD73 or ADORA2A, inhibitors were used as described above. Flow cytometry was used to quantify tumour cell lysis at different effector to target cell (E:T) ratios; within the PKH-26 negative cell population, CFDA-SEdim cells were considered to be lysed. To control for spontaneous leakage of CFDA-SE, stained cells were incubated with medium only.

T cell response to recall antigens

Alloreactive CD8+ T cells were primed by co-culturing PBMC with irradiated (10 Gy) SK-OV-3 OvCA cells at a ratio of 40:1. To block ectonucleotidase activity during priming, ARL67156 or APCP, respectively, were added at 100 μM. SCH58261 (100 nM) was used to inhibit ADORA2A. After 10 days, primed PBMC were harvested and their cytotoxicity was assessed against SK-OV-3 cells expressing a firefly luciferase plasmid kindly provided by Dr. M. Jensen (City of Hope National Medical Centre and Beckman Research Institute, Duarte, CA) [33]. Different E:T ratios were investigated in 96-well plates (104/well) in triplicates. After 4 h, cell-permeant D-luciferin (PJK) was added at 0.14 mg/ml and luminescence (from viable target cells only) was measured using the Orion II luminometer (Berthold). To assess cytotoxicity against siRNA-transfected cells, a modified FATAL assay was used [23].

Statistics

Data were evaluated using Summit v4.1 (DakoCytomation, Fort Collins, USA) and Microsoft Office Excel 2007 (Microsoft, Redmond, USA). In flow cytometric assays with at least 50,000 events, two samples were considered to be significantly different (*) when they were separated by at least twice the sum of the standard deviations for the respective regions. A difference exceeding four times the sum of the respective standard deviations was considered as highly significant (**). Immune cell infiltration in vivo was statistically assessed by Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Results

Expression of CD39 and CD73 in human OvCA specimens and cell lines

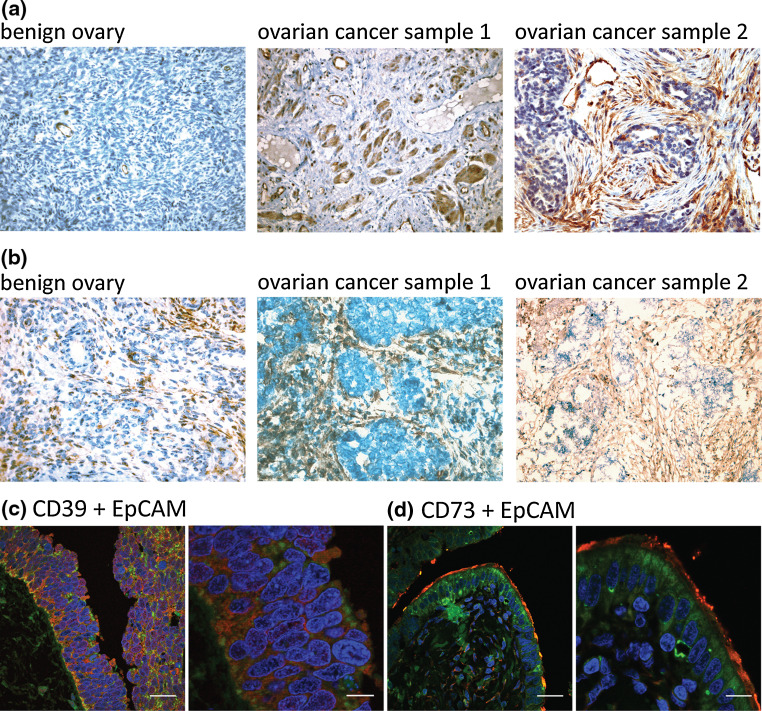

Expression of the ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73 was evaluated in paraffin-embedded (n = 36 for CD39 and n = 27 for CD73) or frozen (n = 9 for CD73 only) human OvCA specimens and benign ovarian tissue samples (n = 9). All malignant samples belonged to the most common serous papillary subtype. Staining with CD39- or CD73-specific antibodies showed that in benign ovaries CD39 expression is restricted to endothelial vessels that served as internal positive control. In OvCA, however, 29 of 36 samples displayed expression of CD39 (Fig. 1a) on tumour (26/36) and/or stromal (27/36) cells. CD73, in contrast, was detected in 8 of 9 examined normal ovaries and in 33 of 36 OvCA samples (Fig. 1b). Tumour cells stained positive in 31/36, stromal cells in 22/36 specimens. Epithelial tumour and stromal cells were identified by their characteristic morphologies as described above. In addition, confocal double staining was performed to show co-localisation of CD39 and CD73 with EpCAM/CD326 (Fig. 1c, d).

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemical analysis of CD39 and CD73 expression in OvCa tissue. a Immunohistochemical staining of 36 serous papillary epithelial OvCAs showed moderate to strong expression of CD39 in 29 of 36 samples. Representative samples are shown in the middle and the right panel. In contrast, 8 out of 9 tissue samples from benign ovaries were negative for CD39 with exception of vascular endothelial cells providing an internal control (left). b CD73 immunoreactivity was detected in 8/9 benign ovaries (a representative staining is shown in the left panel) and in 31/34 epithelial OvCAs of the serous papillary subtype (see middle and right panel). c, d To examine the expression of CD39 (c) and CD73 (d) on tumour and stromal cells, immunofluorescent double staining were performed for EpCAM/CD326 (green) and either CD39 or, respectively, CD73 (red) and. Shown is one representative sample where both ectonucleotidases are mainly expressed on tumour cells. Size bars correspond to 30 μm in the overview pictures (on the left) and to 10 μm when a higher magnification was applied (on the right)

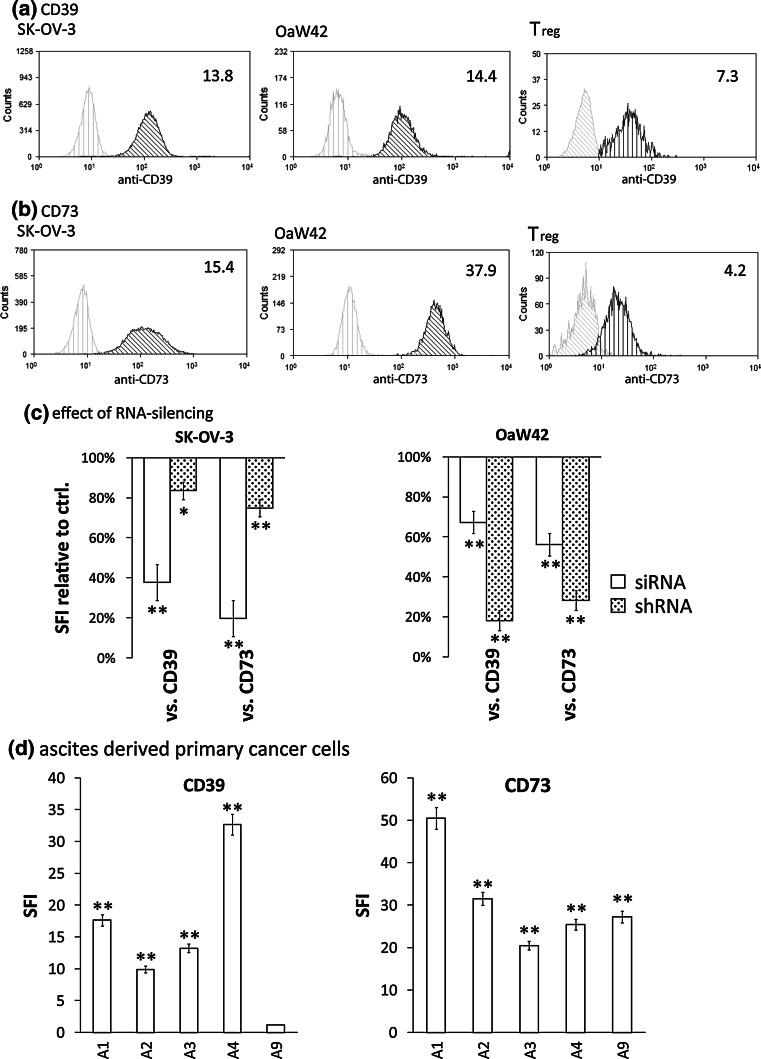

Corresponding to these in vivo data, CD73 could be detected on 14/15, CD39 on 12/15 freshly isolated ascites-derived ovarian carcinoma cultures. Strong expression of both CD39 and CD73 was found on 11/15 primary samples and the human OvCA cell lines SK-OV-3 and OAW42 (Fig. 2a, b, d). In contrast, CD4+CD25− and CD8+ T cells showed no detectable, NK cells and CD4+CD25+ Treg a much weaker expression of CD39. Likewise, CD73 expression was much higher on OvCA cells than on Treg and (rare) CD73-positive CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2a, b and data not shown). Reduction of CD39 and CD73 expression could be achieved using both transient siRNA and stable shRNA transfection, with siRNA being more efficient in SK-OV-3 and shRNA showing a superior effect in OAW42 cells (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of CD39 and CD73 surface levels on primary OvCA cells, OvCA cell lines and Treg. (a, b) SK-OV-3, OAW42 OvCA and freshly isolated human regulatory T cells (Treg) cells were stained for expression of CD39 (a) or CD73 (b) and analysed by flow cytometry. Representative histograms are shown. The indicated specific fluorescence indices (SFI values) were calculated by dividing the mean fluorescence obtained with the specific antibody (black profile) by the fluorescence intensity obtained with the corresponding) isotype control (grey curve) (n = 3). c SK-OV-3 and OAW42 OvCA were transfected with either siRNAs against CD39 or CD73 (siCD39, siCD73, open bars) or with pSUPERpuro plasmids encoding short hairpin RNAs which target the same sequence (shaded bars). CD39 and CD73 surface expression were assessed either 3 days after transient transfection with siRNA or after selection of stable clones expressing pSUPERpuroCD39 (shCD39) or pSUPERpuroCD73 (shCD73), respectively. FACS analysis and evaluation were performed as in (a). d Magnetic beads were used to purify EpCAM-positive OvCa cells from ascites (n = 15). SFI values for CD39 and CD73 expression were determined as described above and are shown for five representative primary tumour cell cultures

SK-OV-3 and OAW42 OvCA cells degrade ATP and generate adenosine via CD39 and CD73

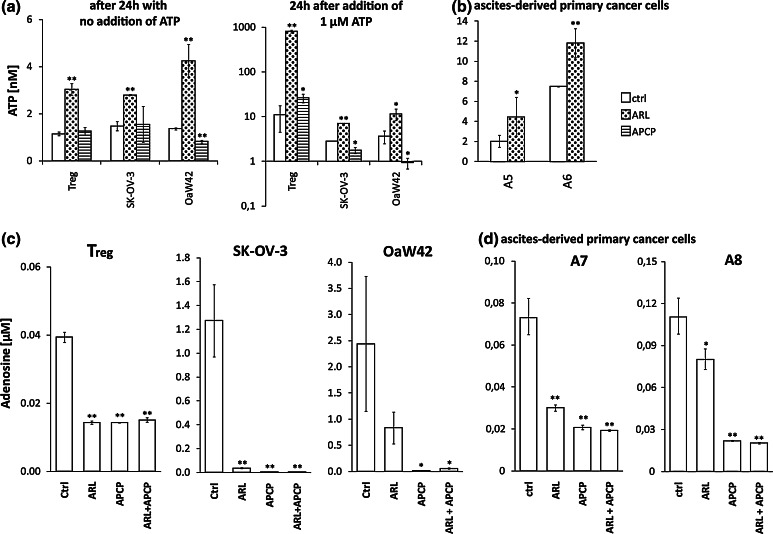

In order to test the functional activity of CD39 and CD73 on OvCA cells, both the consumption of extracellular ATP and the generation of adenosine were assessed in the absence or presence of small molecule inhibitors. Luminescence-based ATP measurements showed that remaining ATP levels in the medium were greatly increased when Treg or OvCA cells were cultured in the presence of the CD39-specific inhibitor ARL67156, while the CD73 inhibitor APCP obviously could not rescue extracellular ATP levels (Fig. 3a)—both with and without addition of exogenous ATP. However, after addition of 1 μM ATP, ARL67156 virtually prevented ATP degradation in the presence of Treg, while the blockade was incomplete with SK-OV-3 or OAW42 cells. Importantly, ARL67156 also increased ATP levels in the presence of primary OvCA cells (Fig. 3b). Free extracellular adenosine can be detected with high sensitivity using RIP1-CRE-luc+ pRL-CMV ADORA2A+ HEK-293 ‘sensor’ cells [28]. Measured adenosine concentrations were 1.3 μM for SK-OV-3, 2.4 μM for OAW42 and ~100 nM for two randomly selected EpCAM+ cultures established from primary patient-derived material (Fig. 3c, d). Using RNA interference, adenosine generation by OAW42 cells was reduced by 57% ± 1% when CD39 was targeted and by 57% ± 7% when a siRNA against CD73 was transfected. Co-expression of CD39- and CD73-specific shRNA constructs resulted in 67% ± 16% less adenosine production. In SK-OV-3 cells, adenosine production went down by 79% ± 7% with the CD39-specific siRNA and by 68% ± 6% when an siRNA against CD73 was applied. In this cell line, the co-expressed CD39 and CD73 shRNAs yielded a 57% ± 1% reduction in adenosine levels. No significant downregulations were observed with scrambled control siRNA or shRNA. When ARL67156 or APCP were added to block CD39 or CD73, respectively, the measured adenosine concentrations decreased to almost background values (Fig. 3c, d)—which confirmed that the chosen, still non-toxic inhibitor concentrations were appropriate for functional experiments. As adenosine levels generated by Treg did not exceed 0.04 μM (Fig. 3c), we conclude that OvCA cells generate far more immunosuppressive adenosine than activated Treg from healthy donors.

Fig. 3.

Quantification of CD39- and CD73-dependent ATP degradation and adenosine generation by Treg and OvCA cells. a 104 cells/well were cultured in 100 μl complete RPMI 1640 medium with or without addition of 1 μM ATP and/or 100 μM of either ARL67156 or APCP or solvent control. After 24 h, free extracellular ATP was measured via addition of recombinant firefly luciferase and d-Luciferin (in excess). A standard curve ranging from 0.1 nM to 10 μM ATP confirmed that the bioluminescent signal obtained under these conditions was directly proportional to the level of available ATP (r = 0.99). b Primary OvCA cells were cultured with and without addition of ARL67156 before ATP levels from supernatant were determined as in (a). As primary cells were limited in number, the APCP control had to be omitted. c, d Adenosine generation from Treg, OvCA cell lines (c) and ascites-derived OvCA cells (d) was quantified using a reporter gene assay based on RIP1-CRE-luc+ pRL-CMV+ ADORA2A+ HEK-293 reporter cells that are co-incubated with the cells of interest at a 1:1 ratio (104 cells/well from each cell type). Adenosine in the cellular microenvironment binds to the ectopically expressed ADORA2A on HEK-293 cells, which leads to increased cAMP levels in the ‘sensor’ cells and thus enhanced activity of the cAMP responsive RIP1-Cre-luc reporter. Firefly luciferase activity was measured after 4 h co-incubation, normalised for co-transfected pRL-CMV activity and related to extracellular adenosine concentrations via a co-determined standard curve. Where indicated, the specific inhibitors of CD39 and CD73, ARL67156 and APCP were added (100 μM) (n = 3). Please note the different scales

Correlation between CD39 and CD73 expression in human OvCA specimens and immune cell infiltration

While we could not detect functionally relevant adenosine receptor expression by OvCA cells (data not shown), the immune inhibitory A2A adenosine receptor (ADORA2A) is known to be expressed by T and NK cells [5, 34] and could also be stained with a polyclonal anti-ADORA2A antiserum on these cell types [26] (data not shown). Consequently, we investigated whether the expression of adenosine-generating enzymes correlated with immune cell infiltration in vivo (Table 1). This revealed that carcinoma tissues (n = 25) showed significantly more infiltration with CD4+ (P = 0.0009), CD8+ (P = 0.002) and Foxp3+ (P = 0.0074) cells than healthy ovaries (n = 8). While those OvCA with the highest CD39 expression on tumour cells (n = 3) showed the least CD4+ and CD8+ T cell infiltration, differences were not significant (P = 0.56 for CD4+ and P = 0.32 for CD8+ T cells), according to Wilcoxon log-rank test—even though unpaired Student’s t test yielded P values <0.05 for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. At the other end of the spectrum, tumours altogether lacking CD39 (n = 8) also showed low CD4+ T cell infiltration (P = 0.17) suggesting that other immunosuppressive mechanisms might be predominant here. In tumours displaying low (n = 7) or intermediate (n = 7) levels of CD39, CD4+ T cell, infiltration was increased (P = 0.09) and very similar (P = 0.78 for CD39intermediate vs. CD39low), while the proportion of Foxp3+ T cells rose with CD39 expression (P = 0.11). Taken together, there were some observable tendencies, but no significant correlation between CD39 expression on tumour cells and immune cell infiltration. Likewise, no significant correlations were observed for CD73 on tumour cells. Looking at stromal cells, however, high expression of CD39 was significantly correlated with low CD4+ T cell infiltration (P = 0.02 for CD39high vs. CD39intermediate). However, in specimens with lower CD39 expression, enhanced infiltration by CD4+ T cells went along with increasing levels of CD39 until intermediate CD39 expression was reached (P = 0.009 for CD39intermediate vs. CD39null and P = 0.008 for CD39intermediate vs. CD39low). Likewise, CD73 expression on stromal cells accompanied increased CD8+ T cell infiltration (P = 0.04 for low vs. no expression, P = 0.01 for intermediate vs. no expression and P = 0.11 for high vs. absent expression). This raises the question whether both CD39 and CD73 expression on stromal cells could be triggered by infiltrating immune cells. Of note, all tumours infiltrated by ≥10 Treg per high power field showed intermediate to high expression of both CD39 and CD73 on tumour and stromal cells.

Table 1.

Correlation between CD39 and CD73 expression in human OvCA specimens and immune cell infiltration

| Tissue specimen | CD39 gradinga epithelial ovarian/OvCa cells | CD39 grading parenchymal/stromal cells | CD73 grading epithelial ovarian/OvCA cells | CD73 grading parenchymal/stromal cells | CD4+ cells per HPF | CD8+ cells per HPF | FoxP3+ cellsper HPF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Ov 1 | − | − | − | + | 0.2 | 0 | 0 |

| Healthy Ov 2 | − | + | − | ++ | 0.2 | 2.1 | 0 |

| Healthy Ov 3 | − | − | + | +++ | 2.2 | 2.8 | 0.1 |

| Healthy Ov 4 | − | − | − | ++ | 0.1 | 1.7 | 0 |

| Healthy Ov 5 | − | − | + | ++ | 0.2 | 0 | 0 |

| Healthy Ov 6 | − | − | − | + | 0.4 | 2.3 | 0 |

| To establish the staining protocols, 3 additional healthy ovaries were stained for expression of CD39 (0/3 positive) and CD73 (2/3 positive) | |||||||

| OvCA 1 | ++ | +++ | ++ | + | 9.7 | 13.9 | 0.7 |

| OvCA 2 | + | ++ | + | − | 30.8 | 3.6 | 1.1 |

| OvCA 3 | + | ++ | + | − | 16.8 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| OvCA 4 | − | +++ | ++ | +++ | 4.2 | 7.9 | 0.25 |

| OvCA 5 | − | − | − | ++ | 1.3 | 24.7 | 2.4 |

| OvCA 6 | + | ++ | +++ | + | 44.4 | 17.4 | 4 |

| OvCA 7 | − | − | +++ | + | 1.3 | 6.2 | 0 |

| OvCA 8 | − | ++ | ++ | +++ | 5.3 | 3.6 | 12.2 |

| OvCA 9 | ++ | ++ | +++ | + | 15.3 | 28.2 | 21.7 |

| OvCA 10 | + | +++ | ++ | ++++ | 5.7 | 23.9 | 0.2 |

| OvCA 11 | ++ | +++ | + | ++ | 0.8 | 85 | 9.8 |

| OvCA 12 | + | +++ | + | − | 16.4 | 0.1 | 2.2 |

| OvCA 13 | − | − | +++ | − | 26.5 | 5.5 | 2.2 |

| OvCA 14 | +++ | − | ++ | − | 1.3 | 13 | 0.9 |

| OvCA 15 | +++ | +++ | ++ | − | 7.6 | 2.3 | 0.1 |

| OvCA 16 | + | +++ | ++ | +++ | 10.2 | 88.8 | 1.1 |

| OvCA 17 | ++ | + | +++ | − | 3.6 | 1.7 | 0.4 |

| OvCA 18 | − | − | ++ | +++ | 11 | 13.9 | 0 |

| OvCA 19 | − | + | − | +++ | 0 | 8.6 | 0 |

| OvCA 20 | +++ | − | +++ | − | 5.1 | 5.3 | 1 |

| OvCA 21 | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | 62.6 | 68 | 13.5 |

| OvCA 22 | − | − | +++ | − | 1 | 21 | 2 |

| OvCA 23 | ++ | ++ | + | + | 36.5 | 12 | 1.8 |

| OvCA 24 | + | + | +++ | − | 0 | 0.7 | 0.2 |

| OvCA 25 | ++ | + | ++ | − | 0.2 | 15.2 | 0.9 |

| OvCA 26 | + | ++ | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| OvCA 27 | + | +++ | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| To establish the staining protocols, 9 OvCA tissue specimens were stained for expression of CD39 (7/9 positive) and CD73 (6/9 positive) | |||||||

HPF high power field

aCD39 and CD73 expression were graded according to the following scheme: (−) signifies absence of detectable staining, (+) corresponds to few positive cells in a focal or diffuse pattern, (++) indicates up to 20% of positive cells, (+++) means 20–50% of clearly stained cells and (++++) was given for >50% of positive cells

Blockade of CD39, CD73 or ADORA2A increases proliferation of CD4+ T cells in co-culture with OvCA cells

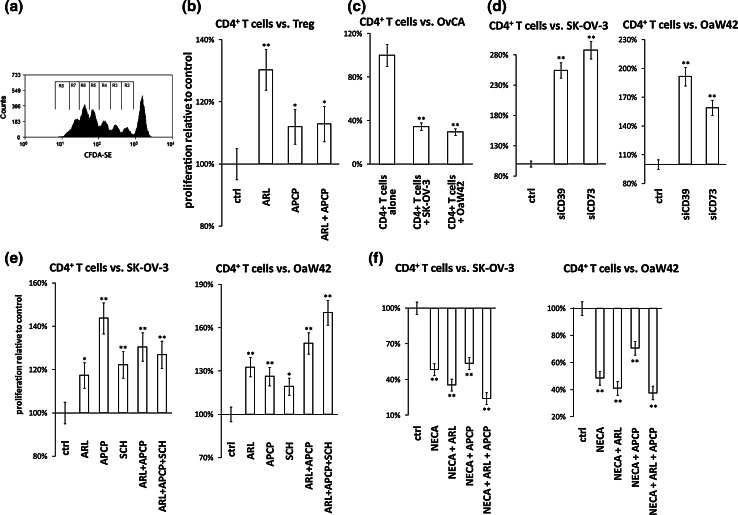

To examine a possible suppression of CD4+ T cell proliferation by OvCA-derived adenosine, CFDA-SE- or CPD eFluor670-labelled CD4+ T cells were first activated with plate-bound antibodies against CD3 and CD28 and then co-incubated with proliferation-inhibited (i.e. irradiated) siRNA-transfected or control SK-OV-3 or OAW42 cells in the absence or presence of specific inhibitors for the ectonucleotidases and ADORA2A. The number of cell divisions was determined as outlined in Fig. 4a. Tests using Treg as adenosine-generating cells [8] showed that ADORA2A-dependent proliferation inhibition can be assessed in this experimental system (Fig. 4b). Further preliminary experiments revealed that both OvCA cell lines reduced T cell proliferation by ~65% (Fig. 4c). In co-culture with SK-OV-3 and OAW42 cells, inhibition of CD39 or CD73 by siRNA now significantly increased the proliferation of CFDA-SE+ CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4d). Slightly weaker, but similar effects were observed with small molecule inhibitors (Fig. 4e). Effects of T cell-derived CD39 or CD73 could be excluded since ARL67156 or APCP or SCH58261 alone had no effect on T cell proliferation (data not shown). As expected, the effects of ARL67156 and APCP could be overruled by exogenous addition of 100 μM adenosine (data not shown) or by adenosine-5′-N-ethylcarboxamide (NECA), a metabolically stable adenosine receptor agonist (Fig. 4f).

Fig. 4.

Effect of CD39, CD73 or A2A adenosine receptor inhibition on the suppressive capacity of OvCA cells against proliferating activated CD4+ T cells. a–f Treg and OvCA cells were co-cultured with CD4+ T cells that had been stained with CFDA-SE (a–e) or Cell Proliferation Dye eFluor® 670 (f) and stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. To inhibit ectonucleotidases, CD39 or CD73 inhibitors ARL67156 (ARL) and APCP were added as indicated (100 μM each). ADORA2A was blocked using 100 nM SCH58261. To activate adenosine receptors, 10 μM adenosine-5′-N-ethylcarboxamide (NECA) was used. a During each cell division, CFDA-SE is distributed equally between the daughter cells, which enables the assessment of a cell’s proliferation history by flow cytometry. In order to determine the total number of cell divisions, the number of counts in each region was divided by 2n (n = number of peak, from right to left, beginning with 0) to determine the number of cells ‘x’ which originally divided into the cytometrically assessed cells of the peak.  gives the total number of cell division per peak n. b–f Representative and independent experiments are shown (n = 3) for the co-culture of CD4+ T cells with Treg (b), SK-OV-3 and OAW42 cells only (c), with siRNA-transfected SK-OV-3 and OAW42 cells (d), with SK-OV-3 and OAW42 cells in the presence or absence of the inhibitors ARL67156, APCP or SCH58261, which block CD39, CD73 or ADORA2A, respectively, (e) and with SK-OV-3 and OAW42 cells in the presence of NECA ± ARL67156 or APCP or both (f)

gives the total number of cell division per peak n. b–f Representative and independent experiments are shown (n = 3) for the co-culture of CD4+ T cells with Treg (b), SK-OV-3 and OAW42 cells only (c), with siRNA-transfected SK-OV-3 and OAW42 cells (d), with SK-OV-3 and OAW42 cells in the presence or absence of the inhibitors ARL67156, APCP or SCH58261, which block CD39, CD73 or ADORA2A, respectively, (e) and with SK-OV-3 and OAW42 cells in the presence of NECA ± ARL67156 or APCP or both (f)

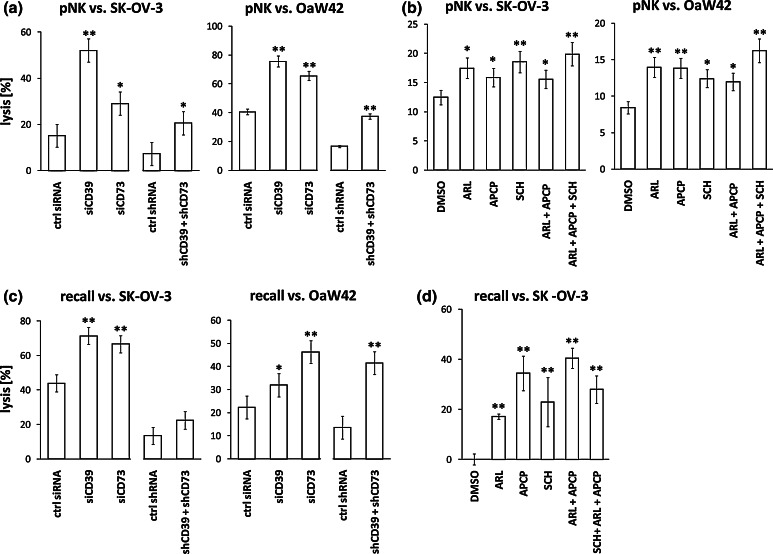

Lytic activity of NK cells against OvCA cells is increased by blockade of CD39, CD73 or ADORA2A

To assess suppression of NK cell-mediated lysis of OvCA cell lines, polyclonal NK cell cultures were obtained from healthy volunteers [23]. PKH-26 labelled polyclonal NK cells were incubated at different E:T ratios with freshly detached CFDA-SE-stained SK-OV-3 and OAW42 cells (control/siCD39/siCD73/shCD39 + shCD73). During the modified 4 h FATAL assays [23], CD39 or CD73 were blocked by the specific inhibitors ARL67156 or APCP as indicated. ADORA2A was inhibited by application of SCH58261. After 4 h, the percentage of PKH-26− CFDA-SEdim OvCa cells was determined by flow cytometry. Inhibition of CD39, CD73 or ADORA2A by siRNA, shRNA or inhibitors resulted in significantly improved lytic activity of polyclonal NK cells against SK-OV-3 (Fig. 5a, b, left) and OAW42 (Fig. 5a, b, right) cells as compared to untreated controls.

Fig. 5.

Effect of CD39, CD73 or A2a adenosine receptor inhibition on the lytic activity of cytotoxic effector cells against OvCA cells. a, b Polyclonal NK cells (pNK) were stained with PKH-26 and co-incubated for 4 h with CFDA-SE labelled OvCa cell lines SK-OV-3 or OAW42 at different effector to target cell (E:T) ratios [45]. Ectonucleotidase activity was either downregulated by transient transfection with siRNA or stable plasmid-based shRNA expression (a) or blocked by addition of ARL67156 or APCP as indicated (both used at 100 μM) (b). SCH58261 (SCH) was used at 100 nM to inhibit ADORA2A. Target cell lysis was determined in modified FATAL assays. Depicted are exemplarily the E:T ratios 10:1 for SK-OV-3 (left) and 5:1 for OAW42 (right). Lower E:T ratios that resulted in reduced target cell lysis showed a similar trend (data not shown). c Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were co-incubated with siRNA- or shRNA-transfected SK-OV-3 or OAW42 cells. On day 10, recall lysis by primed PBMC was evaluated by modified FATAL assays. d PBMC were co-cultured for 10 days with SK-OV-3 OvCA cells in the absence or presence of CD39 and CD73 inhibitors ARL67156 or APCP (used at 100 μM each). ADORA2A signalling was blocked with SCH58261 (100 nM). The lytic activity of the PBMC was then evaluated in a luciferase-based cytotoxicity assay against fresh SK-OV-3 cells that were stably transfected with a firefly luciferase plasmid. As we were unable to obtain suitable luciferase-expressing OAW42 targets, this cell line was not included in the assay. Representative and independent experiments are shown (n = 3)

T cell response to recall antigens from SK-OV-3 cells is increased by inhibition of CD39, CD73 or ADORA2A

To examine the role of CD39, CD73 and ADORA2A with respect to the priming of T cell response against recall antigens, PBMC were isolated from healthy volunteers and co-cultured with irradiated SK-OV-3 or OAW42 cells. When stimulator cells with transient siRNA- or stable shRNA-mediated downregulation of CD39 or CD73 were used, PBMC showed significantly increased lytic activity against fresh CFDA-SE labelled OvCA targets (Fig. 5c). In line with the achieved levels of suppression, siRNA had a considerably greater effect than shRNA for SK-OV-3 cells, while shRNA was slightly superior in OAW42. Likewise, improved T cell priming was achieved when ARL67156, APCP, SCH58261 or combinations thereof were present during the 10 days of co-culture. This was demonstrated by increased lytic activity against luciferase-expressing SK-OV-3 cells (Fig. 5d). From OAW42 OvCA cells, no firefly luciferase-expressing subline could be obtained (data not shown), which precluded their use in this assay. Importantly, no lytic activity against autologous lymphoblasts was observed under these conditions (data not shown).

Discussion

Adenosine, which is known to inhibit the function of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as well as the lytic activity of NK cells [6, 34], is found at high concentrations in some tumour entities [4]. It is thought to be generated from ATP due to recurrent hypoxia in the tumour tissue [35]. Thus, mice deficient for ADORA2A exhibited improved CD8+ T cell-mediated anti-tumour responses and reduced growth of experimental tumours as compared to wild-type controls [5]. Additionally, it has recently been described that Treg generate adenosine via the membrane-bound ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73, revealing thus a novel immunosuppressive mechanism of Treg [8].

In the present study, we demonstrate that OvCA cells express both CD39 and CD73 in vitro (Fig. 2) and in vivo (Fig. 1), which enables them to mimic the paracrine secretion of adenosine previously described for Treg [8]. In contrast, benign ovarian tissues express only CD73 but rarely CD39 (Fig. 1). Within the cancer group, however, ectonucleotidase expression did not correlate with progression-free or overall survival. Considering the various confounding factors (grading, molecular heterogeneity), the limited number of samples and the short observational period for recently resected tumours, such a relationship could not realistically be expected. Nevertheless, while (non-regulatory) T cell infiltration is a favourable prognostic factor in OvCA [36], co-staining of infiltrating immune cells revealed that tumours with the highest stromal CD39 and CD73 expression showed the least infiltration by T cells. Moreover, all tumours containing high numbers of Treg (which indicate poor prognosis [3]) expressed intermediate to high levels of both CD39 and CD73 on tumour and stromal cells. While sample numbers were too low to reliably assess correlations between ectonucleotidase expression and immune cell infiltration, our observations nevertheless give rise to two hypotheses; While high levels of CD39 and CD73 might repell infiltrating lymphocytes, low to moderate levels of CD39 and CD73 on stromal cells might actually be induced by intratumoural T cells. Considering that CD39 is required to hydrolyse extracellular adenosine tri- and diphosphate (ATP/ADP) to adenosine monophosphate (AMP) [8], which is in turn dephosphorylated to adenosine by CD73 [9], the presence of both ectonucleotidases is a prerequisite for the efficient enzymatic conversion of extracellular ATP to adenosine. In fact, ATP levels in supernatant could be saved from degradation by inhibition of CD39, but not by targeting of CD73 (Fig. 3a). While enzymatic conversion of ATP may lead to high adenosine concentrations at the sites of production/conversion (i.e. in the tumour microenvironment or in cell culture), the resulting adenosine is rapidly degraded by adenosine deaminases [37] or internalised via nucleoside carriers [38]. Thus, global adenosine concentrations in the cell culture supernatant may be low and could not be detected via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) endpoint measurements (not even in serum-free medium, data not shown). However, a reporter gene assay employing ADORA2A-transfected HEK-293 ‘sensor’ cells that indicate the presence of adenosine by activation of a downstream luciferase plasmid [28] revealed that OvCA cells generate far greater amounts of adenosine than resting or activated Treg (Fig. 3c, d). The observed low levels of Treg-derived adenosine may not only be species-dependent (human vs. mouse) or related to suboptimal activation of Treg, they could also be biologically meaningful; Since Treg act in a strictly controlled, localised manner, low levels of adenosine might be functionally sufficient. Tumour cells, in contrast, induce a wide-ranging immunosuppressive microenvironment and inhibit immune responses even systemically. Accordingly, tumours could benefit from higher levels of adenosine. On a functional level, we could show that siRNA against or small molecule inhibitors of CD39 and CD73 enhance CD4+ T cell proliferation (Fig. 4d, e), NK cell-mediated lysis (Fig. 5a, b) and cytotoxic T cell priming against recall antigens (Fig. 5c, d) in co-culture with SK-OV-3 and OAW42 OvCA cells. Similar results were obtained by blockade of ADORA2A. Inhibition of CD39 or CD73 was, however, insufficient to overcome the anti-proliferative effect of the adenosine receptor agonist NECA (Fig. 4f). Thus, these model in vitro assays confirm that human OvCA cells inhibit immune responses by a mechanism that depends on CD39, CD73 and ADORA2A.

A critical aspect in these assays is the inclusion of serum that contains adenosine deaminase that will rapidly degrade adenosine. However, as adenosine deaminase is also ubiquitous in vivo—and immune cells are in contact with serum during most of their life—we deliberately did not increase the half-life of adenosine artificially to obtain more pronounced effects. (A rather slight difference in that direction was observed when we used XVivo 15 medium, data not shown). Signals derived from free adenosine will also be short-lived in vivo—but they are, nevertheless, sufficient to exert a strong immunomodulatory effect.

Our findings are fully compatible with recent publications from Mark Smyth’s and Bin Zhang’s laboratories [19, 21]: Using an immune-competent breast cancer model, Stagg et al. [19] have performed a very elegant series of in vivo experiments to demonstrate that the targeting of CD73 is a promising immunotherapeutic strategy for breast cancer. Immunological depletion experiments showed that the observed effects were essentially dependent on the induction of adaptive anti-tumour immune responses. NK cells, in contrast, had an anti-metastatic effect, but did not affect primary tumour growth. Jin et al. [21] tested the functional relevance of CD73 for adoptive immunotherapy; Strikingly, they found that adoptive transfer of OT-1 specific T cells into tumour-bearing C57BL/6 hosts was only curative when the mice had been inoculated with ID8-OVA CD73-knockdown OvCA cells, while control ID8-OVA tumours could not be cleared. This study not only confirms the importance of CD73 in an immune-competent mouse model for OvCA, but also shows that the functional significance of CD39 and CD73 on human OvCA cells cannot be assessed in immune-deficient xenograft models. Thus, it is reassuring that our study confirms the effect of CD73 for human OvCA cells at least in vitro—using both siRNA and pharmacological inhibitors, which may be clinically applicable. Moreover, as CD39 appears to be expressed in an even more tumour-specific pattern than CD73 (Fig. 1) [39, 40], the targeting of CD39 or both ectonucleotidases might be advantageous. (While no cumulative effect was observed when more than one component of this cascade was blocked in vitro, we cannot exclude that additive effects were masked by a certain toxicity of an inhibitor ‘cocktail’.) Inhibiting CD39, which catalyses the first step in the conversion of ATP to adenosine, is also likely to protect free ATP from degradation. This, in turn, may act as an important immunological danger signal that recruits antigen-presenting cells [11] and induces the maturation of dendritic cells. Anti-tumoural immune responses could thus be substantially improved by inhibition of CD39—especially since hypoxia in the tumour microenvironment [12] will both lead to ATP release from necrotic cells [35] and induce CD39 and CD73 expression [41]. As our in vitro assays could not capture the consequences of CD39-dependent ATP depletion in the tumour microenvironment or autocrine tumour-promoting effects mediated by ADORA2B on many cancer cells (but not SK-OV-3 or OAW42), the in vivo impact of targeting CD39 either alone or in combination with CD73 could by far exceed the immune stimulatory effects caused by inhibition of the CD39-CD73-ADORA2A axis in vitro.

From a translational perspective, it is important to note that small molecule inhibitors are available and have already been used in vivo to block CD39 [42], CD73 [43] and ADORA2A [5]. Moreover, small molecule inhibitors of ADORA2A have already been clinically tested in neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson’s disease [44]. Thus, there should be no major obstacles to their application for OvCA patients provided that they can show their efficacy in further OvCA models in vivo, either alone or in combination with other immune therapies.

Taken together, the data obtained in our in vitro model system and from primary tumour tissues strongly suggests that OvCA cells suppress various immune cell populations via adenosine that is generated locally in the tumour microenvironment by the ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73. Consequently, both of these molecules emerge as possible targets for novel immunomodulatory approaches in this tumour entity.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Drs. George G. Holz and Oleg Chepurny (Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY) for providing the RIP1-CRE-luc reporter gene construct used for adenosine measurement.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- CFDA-SE

Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester

- ENTPD1

Ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1

- FITC

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- NK

Natural killer (cells)

- OvCA

Ovarian cancer

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- shRNA

Short hairpin RNA

- siRNA

Short interfering RNA

References

- 1.Pectasides D, Pectasides E. Maintenance or consolidation therapy in advanced ovarian cancer. Oncology. 2006;70(5):315–324. doi: 10.1159/000097943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sugiyama T, Konishi I. Emerging drugs for ovarian cancer. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2008;13(3):523–536. doi: 10.1517/14728214.13.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, Alvarez X, Cheng P, Mottram P, Evdemon-Hogan M, Conejo-Garcia JR, Zhang L, Burow M, Zhu Y, Wei S, Kryczek I, Daniel B, Gordon A, Myers L, Lackner A, Disis ML, Knutson KL, Chen L, Zou W. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10(9):942–949. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blay J, White TD, Hoskin DW. The extracellular fluid of solid carcinomas contains immunosuppressive concentrations of adenosine. Cancer Res. 1997;57(13):2602–2605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohta A, Gorelik E, Prasad SJ, Ronchese F, Lukashev D, Wong MK, Huang X, Caldwell S, Liu K, Smith P, Chen JF, Jackson EK, Apasov S, Abrams S, Sitkovsky M. A2A adenosine receptor protects tumors from antitumor T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(35):13132–13137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605251103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasko G, Cronstein BN. Adenosine: an endogenous regulator of innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2004;25(1):33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borsellino G, Kleinewietfeld M, Di Mitri D, Sternjak A, Diamantini A, Giometto R, Hopner S, Centonze D, Bernardi G, Dell’Acqua ML, Rossini PM, Battistini L, Rötzschke O, Falk K. Expression of ectonucleotidase CD39 by Foxp3+ Treg cells: hydrolysis of extracellular ATP and immune suppression. Blood. 2007;110(4):1225–1232. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-064527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deaglio S, Dwyer KM, Gao W, Friedman D, Usheva A, Erat A, Chen JF, Enjyoji K, Linden J, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK, Strom TB, Robson SC. Adenosine generation catalyzed by CD39 and CD73 expressed on regulatory T cells mediates immune suppression. J Exp Med. 2007;204(6):1257–1265. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Resta R, Yamashita Y, Thompson LF. Ecto-enzyme and signaling functions of lymphocyte CD73. Immunol Rev. 1998;161:95–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1998.tb01574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Csoka B, Himer L, Selmeczy Z, Vizi ES, Pacher P, Ledent C, Deitch EA, Spolarics Z, Nemeth ZH, Hasko G. Adenosine A2A receptor activation inhibits T helper 1 and T helper 2 cell development and effector function. FASEB J. 2008;22(10):3491–3499. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-107458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elliott MR, Chekeni FB, Trampont PC, Lazarowski ER, Kadl A, Walk SF, Park D, Woodson RI, Ostankovich M, Sharma P, Lysiak JJ, Harden TK, Leitinger N, Ravichandran KS. Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance. Nature. 2009;461(7261):282–286. doi: 10.1038/nature08296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aymeric L, Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Tesniere A, Martins I, Kroemer G, Smyth MJ, Zitvogel L. Tumor cell death and ATP release prime dendritic cells and efficient anticancer immunity. Cancer Res. 2010;70(3):855–858. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Künzli BM, Berberat PO, Giese T, Csizmadia E, Kaczmarek E, Baker C, Halaceli I, Büchler MW, Friess H, Robson SC. Upregulation of CD39/NTPDases and P2 receptors in human pancreatic disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292(1):G223–G230. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00259.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dzhandzhugazyan KN, Kirkin AF, Thor Straten P, Zeuthen J. Ecto-ATP diphosphohydrolase/CD39 is overexpressed in differentiated human melanomas. FEBS Lett. 1998;430(3):227–230. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00603-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi XJ, Knowles AF. Prevalence of the mercurial-sensitive EctoATPase in human small cell lung carcinoma: characterization and partial purification. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;315(1):177–184. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morrone FB, Oliveira DL, Gamermann P, Stella J, Wofchuk S, Wink MR, Meurer L, Edelweiss MI, Lenz G, Battastini AM. In vivo glioblastoma growth is reduced by apyrase activity in a rat glioma model. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:226. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braganhol E, Morrone FB, Bernardi A, Huppes D, Meurer L, Edelweiss MI, Lenz G, Wink MR, Robson SC, Battastini AM. Selective NTPDase2 expression modulates in vivo rat glioma growth. Cancer Sci. 2009;100(8):1434–1442. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou X, Zhi X, Zhou P, Chen S, Zhao F, Shao Z, Ou Z, Yin L. Effects of ecto-5′-nucleotidase on human breast cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Oncol Rep. 2007;17(6):1341–1346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stagg J, Divisekera U, McLaughlin N, Sharkey J, Pommey S, Denoyer D, Dwyer KM, Smyth MJ. Anti-CD73 antibody therapy inhibits breast tumor growth and metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1547;107(4):1547–1552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908801107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L, Zhou X, Zhou T, Ma D, Chen S, Zhi X, Yin L, Shao Z, Ou Z, Zhou P. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase promotes invasion, migration and adhesion of human breast cancer cells. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134(3):365–372. doi: 10.1007/s00432-007-0292-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin D, Fan J, Wang L, Thompson LF, Liu A, Daniel BJ, Shin T, Curiel TJ, Zhang B. CD73 on tumor cells impairs antitumor T-Cell responses: a novel mechanism of tumor-induced immune suppression. Cancer Res. 2010;70(6):2245–2255. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Panjehpour M, Castro M, Klotz KN. Human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 expresses endogenous A2B adenosine receptors mediating a Ca2+ signal. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;145(2):211–218. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krockenberger M, Dombrowski Y, Weidler C, Ossadnik M, Honig A, Häusler S, Voigt H, Becker JC, Leng L, Steinle A, Weller M, Bucala R, Dietl J, Wischhusen J. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor contributes to the immune escape of ovarian cancer by down-regulating NKG2D. J Immunol. 2008;180(11):7338–7348. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aversa GG, Suranyi MG, Waugh JA, Bishop AG, Hall BM. Detection of a late lymphocyte activation marker by A1, a new monoclonal antibody. Transplant Proc. 1988;20(1):49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dörken B, Möller P, Pezzuto A, Schwartz-Albiez R, Moldenhauer G, et al. Part I: B-cell antigens. In: Knapp W, Dörken B, Gilks WR, et al., editors. Leukocyte typing IV: white cell differentiation antigens. New York: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buira SP, Albasanz JL, Dentesano G, Moreno J, Martin M, Ferrer I, Barrachina M. DNA methylation regulates adenosine A(2A) receptor cell surface expression levels. J Neurochem. 2010;112(5):1273–1285. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neufeld HA, Towner RD, Pace J. A rapid method for determining ATP by the firefly luciferin-luciferase system. Experientia. 1975;31(3):391–392. doi: 10.1007/BF01922604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Häusler SF, Ossadnik M, Horn E, Heuer S, Dietl J, Wischhusen J. A cell-based luciferase-dependent assay for the quantitative determination of free extracellular adenosine with paracrine signaling activity. J Immunol Methods. 2010;361(1–2):51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dyer BW, Ferrer FA, Klinedinst DK, Rodriguez R. A noncommercial dual luciferase enzyme assay system for reporter gene analysis. Anal Biochem. 2000;282(1):158–161. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crack BE, Pollard CE, Beukers MW, Roberts SM, Hunt SF, Ingall AH, McKechnie KC, Ijzerman AP, Leff P. Pharmacological and biochemical analysis of FPL 67156, a novel, selective inhibitor of ecto-ATPase. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;114(2):475–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13251.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krug F, Parikh I, Illiano G, Cuatrecasas P. α,β-methylene-adenosine 5′-triphosphate. A competitive inhibitor of adenylate cyclase in fat and liver cell membranes. J Biol Chem. 1973;248(4):1203–1206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ongini E, Dionisotti S, Gessi S, Irenius E, Fredholm BB. Comparison of CGS 15943, ZM 241385 and SCH 58261 as antagonists at human adenosine receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1999;359(1):7–10. doi: 10.1007/PL00005326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown CE, Wright CL, Naranjo A, Vishwanath RP, Chang WC, Olivares S, Wagner JR, Bruins L, Raubitschek A, Cooper LJ, Jensen MC. Biophotonic cytotoxicity assay for high-throughput screening of cytolytic killing. J Immunol Methods. 2005;297(1–2):39–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoskin DW, Mader JS, Furlong SJ, Conrad DM, Blay J. Inhibition of T cell and natural killer cell function by adenosine and its contribution to immune evasion by tumor cells (review) Int J Oncol. 2008;32(3):527–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi J, Wan Y, Di W. Effect of hypoxia and re-oxygenation on cell invasion and adhesion in human ovarian carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2008;20(4):803–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang L, Conejo-Garcia JR, Katsaros D, Gimotty PA, Massobrio M, Regnani G, Makrigiannakis A, Gray H, Schlienger K, Liebman MN, Rubin SC, Coukos G. Intratumoral T cells, recurrence, and survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(3):203–213. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Havre PA, Abe M, Urasaki Y, Ohnuma K, Morimoto C, Dang NH. The role of CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV in cancer. Front Biosci. 2008;13:1634–1645. doi: 10.2741/2787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eltzschig HK, Abdulla P, Hoffman E, Hamilton KE, Daniels D, Schönfeld C, Löffler M, Reyes G, Duszenko M, Karhausen J, Robinson A, Westerman KA, Coe IR, Colgan SP. HIF-1-dependent repression of equilibrative nucleoside transporter (ENT) in hypoxia. J Exp Med. 2005;202(11):1493–1505. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mandapathil M, Hilldorfer B, Szczepanski MJ, Czystowska M, Szajnik M, Ren J, Lang S, Jackson EK, Gorelik E, Whiteside TL. Generation and accumulation of immunosuppressive adenosine by human CD4+CD25highFOXP3+ regulatory T cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(10):7176–7186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.047423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mandapathil M, Szczepanski MJ, Szajnik M, Ren J, Lenzner DE, Jackson EK, Gorelik E, Lang S, Johnson JT, Whiteside TL. Increased ectonucleotidase expression and activity in regulatory T cells of patients with head and neck cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(20):6348–6357. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eltzschig HK, Ibla JC, Furuta GT, Leonard MO, Jacobson KA, Enjyoji K, Robson SC, Colgan SP. Coordinated adenine nucleotide phosphohydrolysis and nucleoside signaling in posthypoxic endothelium: role of ectonucleotidases and adenosine A2B receptors. J Exp Med. 2003;198(5):783–796. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Enjyoji K, Kotani K, Thukral C, Blumel B, Sun X, Wu Y, Imai M, Friedman D, Csizmadia E, Bleibel W, Kahn BB, Robson SC. Deletion of CD39/ENTPD1 results in hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2008;57(9):2311–2320. doi: 10.2337/db07-1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Synnestvedt K, Furuta GT, Comerford KM, Louis N, Karhausen J, Eltzschig HK, Hansen KR, Thompson LF, Colgan SP. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) regulation by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates permeability changes in intestinal epithelia. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(7):993–1002. doi: 10.1172/JCI15337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanganelli S, Sandager Nielsen K, Ferraro L, Antonelli T, Kehr J, Franco R, Ferre S, Agnati LF, Fuxe K, Scheel-Krüger J. Striatal plasticity at the network level. Focus on adenosine A2A and D2 interactions in models of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2004;10(5):273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sheehy ME, McDermott AB, Furlan SN, Klenerman P, Nixon DF. A novel technique for the fluorometric assessment of T lymphocyte antigen specific lysis. J Immunol Methods. 2001;249(1–2):99–110. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(00)00329-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]