Abstract

Background

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), in addition to being pro-angiogenic, is an immunomodulatory cytokine systemically and in the tumor microenvironment. We previously reported the immunomodulatory effects of radiation and temozolomide (TMZ) in newly diagnosed glioblastoma. This study aimed to assess changes in peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) populations, plasma cytokines, and growth factor concentrations following treatment with radiation, TMZ, and bevacizumab (BEV).

Methods

Eleven patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma were treated with radiation, TMZ, and BEV, following surgery. We measured immune-related PBMC subsets using multi-parameter flow cytometry and plasma cytokine and growth factor concentrations using electrochemiluminescence-based multiplex analysis at baseline and after 6 weeks of treatment.

Results

The absolute number of peripheral blood regulatory T cells (Tregs) decreased significantly following treatment. The lower number of peripheral Tregs was associated with a CD4+ lymphopenia, and thus, the ratio of Tregs to PBMCs was unchanged. The addition of bevacizumab to standard radiation and temozolomide led to the decrease in the number of circulating Tregs when compared with our prior study. There was a significant decrease in CD8+ cytotoxic and CD4+ recent thymic emigrant T cells, but no change in the number of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Significant increases in plasma VEGF and placental growth factor (PlGF) concentrations were observed.

Conclusions

Treatment with radiation, TMZ, and BEV decreased the number but not the proportion of peripheral Tregs and increased the concentration of circulating VEGF. This shift in the peripheral immune cell profile may modulate the tumor environment and have implications for combining immunotherapy with anti-angiogenic therapy.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-016-1941-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Glioblastoma, Immune modulation, Tregs, Bevacizumab, VEGF

Introduction

Glioblastoma, the most frequent and most malignant of all brain tumors, is associated with an immunosuppressed state, which supports the hypothesis that reversing tumor-specific immune suppression may lead to therapeutic benefit. The encouraging results from early clinical trials using immune enhancing therapy have led to large phase III studies that are currently underway (NCT02017717, NCT01480479, NCT00045968). Thus, understanding the effects of treatment on the immune environment in patients with glioblastoma is critical in designing studies combining different treatment modalities. We and others have demonstrated that concurrent radiation therapy (RT) and TMZ can worsen immune suppression [1]. In our prior study, we found that RT and TMZ did not change the absolute number of circulating regulatory T cells (Tregs), but did increase the proportion of functional CD4+ Tregs [1], suggesting that Tregs are less susceptible to chemoradiation than other immune cells. In addition, standard RT and TMZ therapy significantly depleted effector cell populations (CD3−CD56+ and CD8+CD56+ cell subsets). In this study, we expand our observations to the immunological effects of adding anti-VEGF therapy with bevacizumab (BEV) to standard RT and TMZ in patients with glioblastoma.

Glioblastomas are highly vascular tumors that demonstrate high systemic concentrations of VEGF [2] as a consequence of hypoxia and increased concentrations of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) [3]. In addition to its pro-angiogenic function, VEGF contributes to immunosuppression through several potential mechanisms [4, 5] including impaired function, maturation, and differentiation of dendritic cells (DCs) [6], induction of CD4+ Treg differentiation and proliferation, and promotion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) leading to defective antitumor immunity [7]. Another proposed mechanism of immunosuppression based on observations in animal models is VEGF-induced thymic atrophy, resulting in decreased T cell production by the thymus [8] and higher proportions of Tregs compared with effector T cells in the circulation.

Bevacizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody with high binding affinity for the soluble isoform VEGF-A. Administration of BEV to cancer patients has been associated with a decreased number of circulating immature DCs and Tregs, and a trend to increased numbers of CD3+ and CD4+ lymphocytes [9]. In a breast cancer xenograft, concurrent administration of low-dose VEGFR2 antibody with a cancer vaccine potentiated tumor cell killing and prolonged animal survival [10], effects which were not seen with high dose antibody. This observation raises questions about the optimal dosing of BEV that could be used in human trials to enhance immune therapy.

We hypothesized that adding BEV to standard treatment for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma could reverse the peripheral blood immune suppressive profile which we reported to be associated with standard TMZ and RT [1]. We studied changes in peripheral blood immune cell subsets and concentrations of plasma cytokines and growth factors in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma pre- and post-treatment with combined RT, TMZ, and BEV. We also compared changes in major cell subsets and Tregs in this group of patients to our prior group of glioblastoma patients treated with standard chemoradiation (RT+TMZ) alone.

Materials and methods

Study patients

In this open-label single institution study, we enrolled patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma confirmed by central pathology review at our institution. Along with standard RT and TMZ chemotherapy, this group of study patients was treated with BEV. The study protocol was approved by the local Institutional Review Board. All patients gave written informed consent prior to the performance of any study procedures. Patients were enrolled in the study after their first surgery for tumor resection. Patients who underwent brain tumor biopsy only were excluded. Plasma samples collected from 9 patients enrolled in a concurrently run study (NCT01849952) who received standard RT and TMZ for their newly diagnosed glioblastomas were used as controls to compare cytokine results to our study group.

Study design

Patients underwent surgery for tumor resection and had a postoperative MRI within 48 h of surgery to determine the extent of resection. Four to six weeks postoperatively, patients were treated with 30 fractions of conformal external beam RT with concomitant oral TMZ 75 mg/m2/day for 6 weeks. BEV (10 mg/kg) was started after the first week of RT and administered every 14 days for up to 3 doses. Following the standard 6-week course of this combination, adjuvant TMZ and BEV were continued in 28-day cycles with oral TMZ (150–200 mg/m2/day) for the first 5 days of each 28-day cycle and BEV (10 mg/kg) given intravenously on days 1 and 15. Venous blood samples were obtained at two time points: “pre-treatment,” which was after surgery and before beginning RT/TMZ/BEV; and “post-treatment” on cycle 1 day 1 of maintenance adjuvant TMZ and BEV. Blood samples were analyzed for immune cell subsets, plasma cytokines, and growth factors. Patients were followed clinically at appropriate time intervals, and treatment-related adverse events were recorded and graded based on NCI CTEP CTCAE version 4.0 criteria.

Major immune subsets results were compared with those obtained from patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma who were treated with surgery followed by standard radiochemotherapy in our previously published study [1]. Blood samples were drawn on the same schedule as the current experimental group.

Venous blood sample processing for PBMCs and T cell subsets

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from sodium heparinized whole blood by Ficoll (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) density gradient centrifugation, washed and frozen. PBMCs from each time point were stored in aliquots at −140 °C in freeze media made up of 90% pooled human AB serum (Gemini Bioproducts, West Sacremento, CA) and 10% dimethylsulfoxide (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). At each time point, plasma was isolated from venous blood collected in ACD (acid, citrate, dextrose) tubes, as well as from sodium heparinized tubes. Tubes were centrifuged at 1000×g for 15 min, and then, aliquots of plasma were frozen and stored at −80 °C.

Immune cell subsets

PBMCs obtained at both time points for each patient were thawed, washed, and stained concurrently with combinations of fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies for surface staining to define the immune subsets of interest. Prior to surface staining, PBMCs were labeled with a 1:10,000 dilution of L/D (live/dead) violet viability dye (Invitrogen, Grand Isle, NY), to exclude dead cells at the time of analysis. To identify the activating and suppressive cell subsets (Supplemental Table 2), the following antibodies were used: From Beckman Coulter (Brea, CA): CD8-FITC clone B9.11, CD19-FITC clone J3-119, CD31-FITC clone 5.6E, CD56-PE clone N901, CD45RA-PE clone ALB11, CD45RO-PE clone UCHL1, CD123-PE clone SSDCLY107D2, CD33-PE clone D3HL60.251, CD24-PE clone ALB9, CD8-PECy7 clone SFCl121Thy2D3, HLA-DR-PECy7 clone Immu-357, CD38-PECy7 clone LS198-4.3, CD11b-APC clone Bear1, CD14-APC clone RM052, and CD4-APC Alexa750 clone 1388.2; from Biolegend (San Diego, CA): CD107a-FITC clone H4A3, CD152-PE (αCTLA4) clone L3D10, CD25-PECy7 clone BC96, CD127-APC clone A019D5; from Becton–Dickinson (San Jose, CA): Lineage-FITC (includes FITC labeled CD3 clone SK7, CD14 clone MØP9, CD16 clone 3G8, CD19 clone SJ25C1, CD20 clone L27, and CD56 clone NCAM16.2), CD3-PerCPCy5.5 clone UCHT1, CD11c-APC clone B-ly6, CD28-APC clone CD28.2; from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN): CD197-APC (αCCR7) clone 150503.

L/D violet labeled cells were stained from 45 to 60 min at 4 °C in the presence of 3 mg/mL human IgG block (Sigma), then washed and fixed in 1X PBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT) containing 0.1% methanol-free paraformaldehyde (Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA), and stored at 4 °C until acquisition. Fixed cells were acquired on a MacsQuant10 (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA), with 400,000 to 700,000 events collected per sample. Miltenyi MACS Comp mouse IgK Reagent (cat. #130-094-548) was used according to manufacturer instructions, to allow for cell-based compensation. Cells were acquired uncompensated, and compensation was set using FlowJo software (Treestar, Ashland, OR). Cell subset proportions were then analyzed on compensated cells using FlowJo, pre-gating on viable cells based on exclusion of L/D violet-positive dead cells.

Absolute numbers of cells per µL or mL of blood were calculated based on results of a complete blood count (CBC) done at the time of venous blood sample procurement for the isolation of PBMCs. Lymphocyte and/or monocyte counts/µL from the CBC were multiplied by successive proportions of cell subsets quantified by flow cytometry based on the gating strategy for the cell population of interest.

We defined Tregs as CD3+CD4+CD25+ high in our historical controls [1]. For the current study with the additional BEV treatment, the staining panel included CD127, so Tregs were further designated as CD3+CD4+CD25+CD127− lymphocytes. Supplemental Figure 1 (online only) illustrates the flow cytometry gating of Tregs for each of the two patient groups.

Plasma concentrations of soluble cytokines and growth factors

Plasma concentrations of cytokines and growth factors were quantified using electrochemiluminescence multiplex assay kits from MESO Scale Discovery (MSD, Rockville, MD). The following all-inclusive kits were used and each run according to the manufacturer’s instructions: Human Cytokine Panel I custom 4-plex kit for granulocyte–monocyte colony-stimulating factor (GMCSF), interleukin 12p40 (IL-12p40), IL-15, IL-17a; Human Pro-Inflammatory I custom 6-plex kit for interferon gamma (IFN-ƴ), IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13; Human Pro-Inflammatory II 4-plex ultra-sensitive kit for IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα); Human Growth Factor panel I 4-plex kit for beta-fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt-1), PlGF, VEGF; and Human custom prototype single-plex kit for stromal cell-derived factor 1-alpha (SDF-1α). Standard curves for each analyte were prepared and run according to kit instructions in duplicate, along with duplicate wells of each patient plasma sample. Using the same MESO Scale Discovery assay kits, VEGF, PlGF, and IL-12p40 concentrations were determined for 9 control patients from a concurrently run study, who were treated with standard RT and TMZ only. Plasma was isolated from venous blood drawn at time points comparable to our study group.

Plasma isolated from ACD tubes was used for all assays with the exception of the SDF-1α kit, for which plasma isolated from both the ACD and sodium heparinized tubes was tested. We were unable to report on SDF-1α concentration, because we learned, after the samples had been processed and run using a prototype kit, that specially prepared platelet poor plasma was required for its accurate quantitation. To determine the plasma concentration of cytokines and growth factors, the assay plates were run on the MSD Sector Imager 2400, and the acquired electrochemiluminescence signal data for each soluble protein cytokine and growth factor were analyzed and quantified using instrument specific software for curve fitting and determination of the concentration in pg/mL for each patient sample, based on the upper and lower limits of detection for each analyte. There were several plasma cytokines measured that were uninformative because the majority of values were below the lower limit of detection of the assays: These included IL-1β, GMCSF, IL-17a, IL-2, and IL-4.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism 6. We used paired t tests, one sample t test, the Wilcoxon matched signed-rank tests, and the Mann–Whitney test to establish the significance of treatment effects in patients using p ≤ 0.05 as our target alpha error. We assumed for sample size calculation based on our prior study [1] that if the mean shift in Treg cell fraction is no more than 0.5%, with 11 patients, we have 80% power to reject the null hypothesis that Treg cell fraction treatment-related change is equal to or more than 3%.

Results

Patients and clinical outcomes

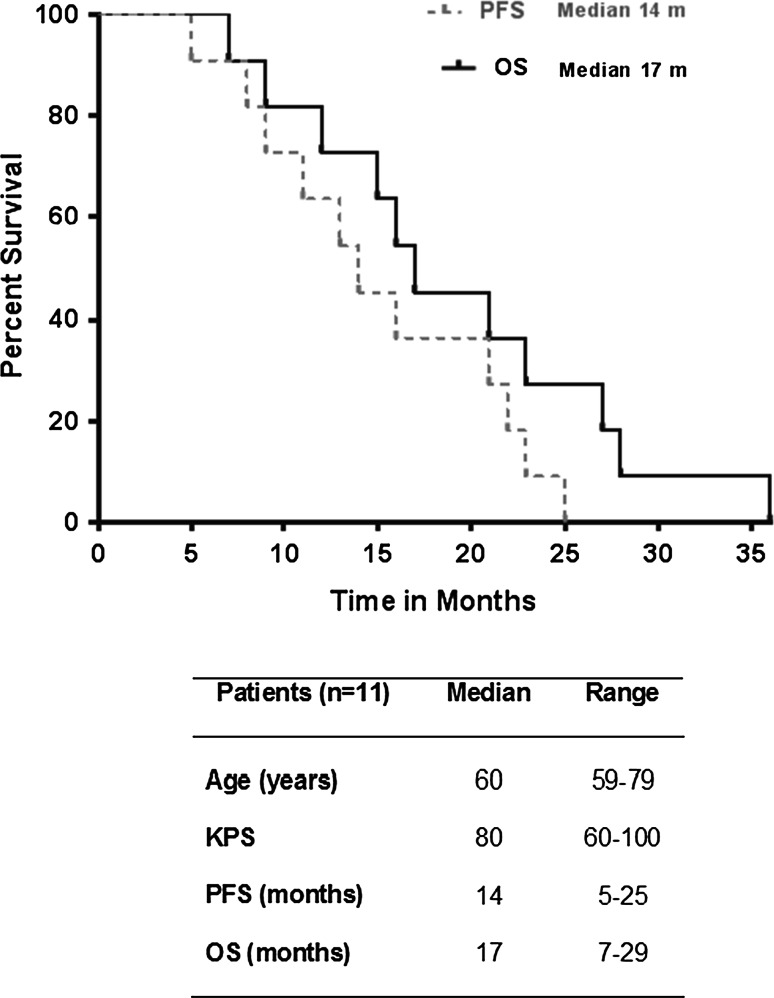

Eleven patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma were enrolled in the current study. Ten patients were not receiving corticosteroids at the start of RT, while one patient was receiving 4 mg of oral dexamethasone per day. Two patients (18%) had a gross total resection prior to starting therapy, while the remaining 82% underwent subtotal resection. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 14 months (range 5–25 months), and the median overall survival (OS) was 17 months (range 7–29 months) (Fig. 1). All patients completed 6 weeks of concurrent RT, TMZ, and BEV and at least 1 cycle of adjuvant TMZ and BEV. The time interval between the previous BEV treatment and the post-treatment blood draw was 14 days for 9 patients and 19 and 20 days, respectively, for the remaining two patients. The side effect profile of the study treatment and corresponding toxicity grades are summarized in Supplemental Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve and patient demographics. KPS Karnofsky performance scale at study entry

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell profile

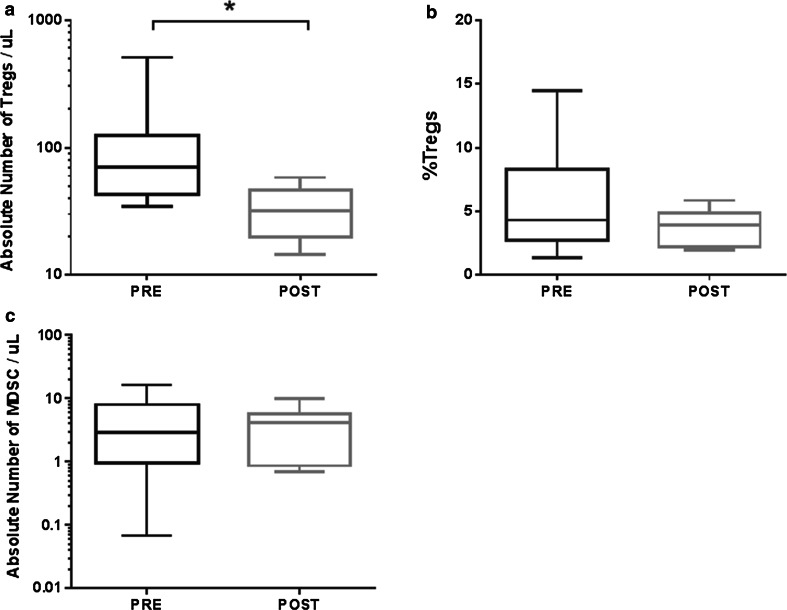

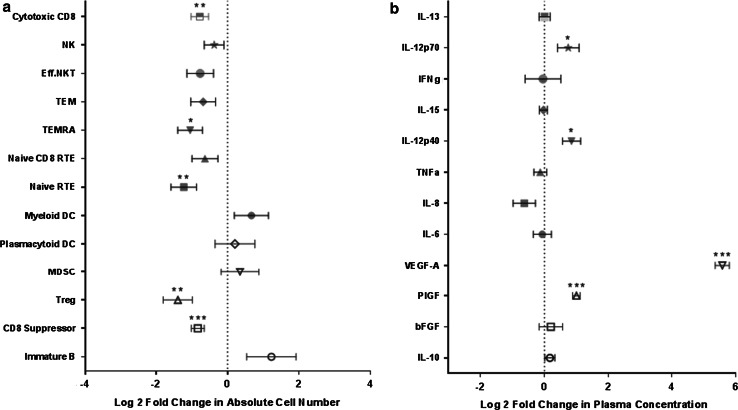

Treatment with BEV in addition to standard therapy with RT and TMZ followed by concurrent TMZ and BEV significantly decreased the absolute numbers of Tregs in peripheral blood (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 0.02; Fig. 2a). Before treatment, circulating Treg counts in peripheral blood were a median of 70 cells/μL (range 34–506 cells/µL), which decreased to 32 cells/μL (range 14–58 cells/µL) after treatment. Although there was a significant decrease in the absolute number of Tregs, there was no significant change in the proportion of PBMCs that were Tregs (CD3+CD4+CD25+CD127−, p = 0.16; Fig. 2b). Furthermore, we found no significant change in the ratio of CD8+T cells to Tregs, the number of immature DCs (Lin−HLADR−) (data not shown), nor in the number of MDSCs (Lin−HLADR−CD11b+CD33+) following treatment with BEV (p = 0.92; Fig. 2c). There was a significant decrease in the absolute number of several other cell subsets measured: CD8 cytotoxic (CD8+CD107a+), CD8 effector memory (CD3+CD8+CD45RA+CCR7−), CD4 naïve recent thymic emigrant (CD3+CD4+CD45RA+CD31+), and CD8 suppressor (CD3+CD8+CD28−CTLA4+) cells. Treatment-related changes in the absolute number of these and other activating and suppressive immune cell subsets are summarized in Fig. 3a. Flow cytometry gating definitions of subsets represented in Fig. 3a can be found in Supplemental Table 2.

Fig. 2.

Box and whisker plots of the changes in cell populations after treatment with BEV, as measured by flow cytometry. a The absolute number of Tregs (CD3+CD4+CD25+CD127−) in peripheral blood decreased significantly (p = 0.02, Wilcoxon signed-rank test) from the pre-treatment time point (PRE) to the cycle 1 day 1 time point (POST), n = 9 patients. b The percent of PBMCs that are Tregs did not change significantly (p = 0.16, Wilcoxon signed-rank test) following treatment with BEV, n = 9 patients. c The absolute number of MDSCs pre- and post-treatment, n = 10 patients

Fig. 3.

Comprehensive pre- and post-treatment-related (PRE-POST) changes in selected peripheral blood immune cell subsets and plasma concentrations of cytokines and growth factors. a Log2 fold changes in the absolute numbers of measured circulating immune activating (solid) and suppressive (open) cell subsets (mean ± SE, n = 9 to 11 pts/subset). b Log2 fold changes in the plasma concentration of measured immune activating (solid) and suppressive (open) soluble cytokines/growth factors (mean ± SE, n = 11 pts). Level of significance is indicated by asterisks; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005; ***p < 0.0005 in a one sample “t” test with the null hypothesis that the mean treatment effect was 0

Plasma cytokine/growth factor profiles

We measured the concentrations of circulating cytokines and growth factors in plasma, including VEGF, PlGF, IL12p40, IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, IL-15, IFNγ, IL-12p70, IL-13, IL-10, and bFGF (Fig. 3b). There was a significant increase in plasma VEGF concentrations following treatment with RT, TMZ, and BEV from a mean pre-treatment value of 51 pg/mL to a mean post-treatment value of 2422 pg/mL (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 0.001; Fig. 4a). The magnitude of this increase in plasma VEGF was not observed in the glioblastoma population treated only with standard RT and TMZ (mean pre-treatment 83.8 pg/mL, mean post-treatment 142 pg/mL, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 0.977; Fig. 4b). We also observed a significant treatment-related increase in PlGF from 15 to 30 pg/mL (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 0.001; Fig. 4c), which was not observed in concurrent controls treated with standard of care (mean pre-treatment PlGF 18 pg/mL, post-treatment 19 pg/mL, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 0.074; Fig. 4d). We observed an increase in IL-12p40 after treatment with either RT, TMZ, and BEV (Pre: 71 pg/mL to Post: 115 pg/mL, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 0.014), or in patients treated with standard RT and TMZ (Pre: 112 pg/mL to Post: 213 pg/mL, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 0.055), suggesting that this was not a BEV-specific effect. With the exception of IL-12, we found that plasma cytokines with immune-activating function (IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, IL-12p40, IL-15, IFNγ, IL-12p70, and IL-13) decreased or were unchanged following treatment with BEV (Fig. 3b; Supplemental Table 3).

Fig. 4.

Mean plasma cytokine/growth factor concentrations pre- and post-treatment with RT and TMZ for study patients treated with BEV (a, c) or for concurrent control group without BEV (b, d). Plasma samples were drawn prior to start of radiochemotherapy and after completion of 6 weeks of RT with TMZ ± BEV, but prior to start of cycle 1 of adjuvant TMZ. a Significant increase in VEGF concentration after treatment with RT, TMZ, and BEV (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 0.001). PRE: 51 pg/mL, POST: 2423 pg/mL. b No significant change in VEGF concentration after treatment with standard RT and TMZ (PRE: 84 pg/mL, POST: 142 pg/mL, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 0.98). c Significant increase in PlGF concentration after treatment with BEV (PRE: 15 pg/mL, POST: 30 pg/mL, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 0.001). d. No significant change in PlGF concentration after standard RT and TMZ (PRE: 18 pg/mL, POST: 19 pg/mL, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 0.07)

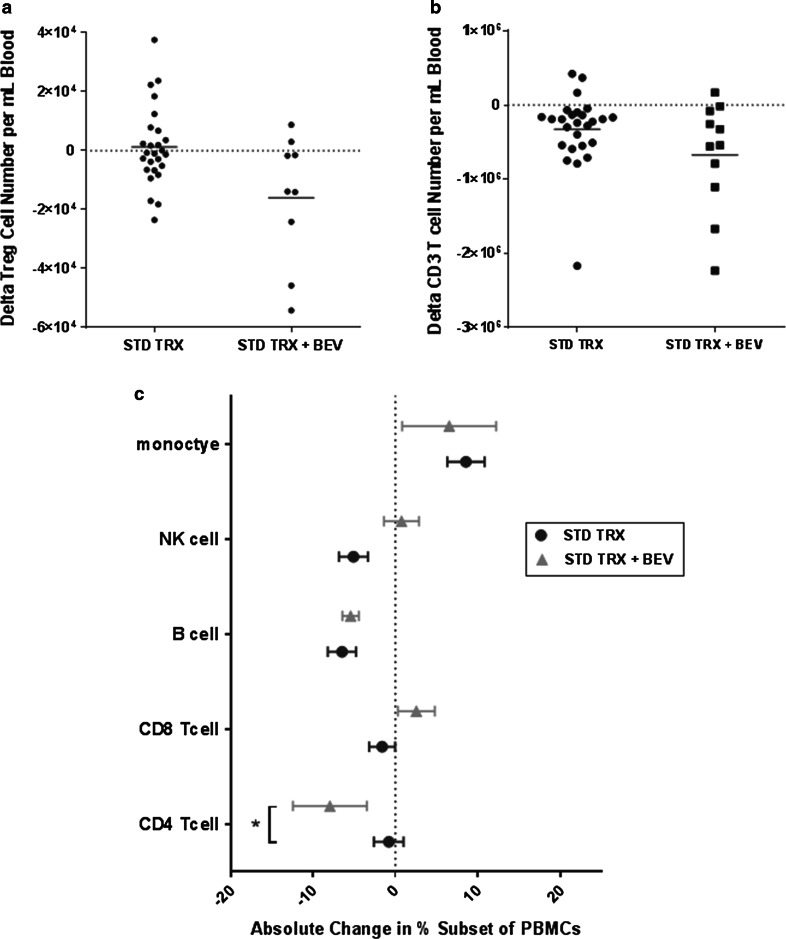

Effects of RT+TMZ+BEV compared to RT+TMZ on Tregs and major cell subsets

We previously published data on changes in Treg, CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+T cell profiles in 26 patients with glioblastoma treated with standard RT and TMZ [1]. We used this data set as a historical control. Standard chemoradiation did not significantly alter the number of circulating Tregs (CD3+CD4+CD25high), while RT and TMZ with BEV significantly decreased Tregs numbers (p = 0.02, Fig. 2a), but the difference in the treatment effect on Tregs for the experimental group and the historical control group was not significant (p = 0.059, Fig. 5a). A treatment-related decrease in the absolute number of CD3+T cells was observed for both treatment groups with no difference found between groups (p = 0.183; Fig. 5b). We then compared the treatment-related changes in the proportion of major PBMC cell subsets for these two groups of patients and observed a significant decrease in CD4+T cells in the RT+TMZ+BEV-treated group that was not seen with standard-of-care treatment (p = 0.05; Fig. 5c). We also noted a decrease in the percentage of B cells following RT+TMZ and RT+TMZ+BEV (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

a Change in the absolute number of circulating Tregs (CD3+CD4+CD25high) following 6 weeks of concurrent RT and TMZ (n = 26, data previously published) versus 6 weeks of concurrent RT, TMZ, and BEV (n = 10). There was a trend toward a difference in the treatment effect between the two groups (p = 0.059, Mann–Whitney test). b Change in the absolute number of circulating CD3+T cells following 6 weeks of concurrent RT and TMZ (n = 26, data previously published) versus 6 weeks of concurrent RT, TMZ, and BEV (n = 10). No significant difference between the two treatment groups (p = 0.183, Mann–Whitney test). c Mean ± standard error treatment-related changes in the proportion of major PBMC cell subsets for similar treatment time points for the two groups. A comparison of changes for the previously published group of patients (n = 26) treated with standard chemoradiation and the current study group (n = 11), treated with chemoradiation and BEV; CD4+T cells (p = 0.05), CD8+T cells (p = 0.25), B cells (p = 0.79), NK cells (p = 0.11), and monocytes (p = 0.58)

Discussion

In this report, we extend our observations of the treatment effects on the peripheral blood immune environment of patients with glioblastoma receiving standard chemoradiation, to treatment effects when BEV is added to this regimen. Others have demonstrated that, in addition to its well-defined anti-angiogenic properties, BEV may modulate the tumor immune milieu, and potentially enhance the immune response in patients with cancer [5, 11, 12]. The data from this study show that treatment with RT, TMZ, and BEV in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma significantly decreased the number of peripheral Tregs in the setting of CD4+ lymphopenia, and simultaneously increased the plasma concentrations of VEGF-A, PIGF and IL-12 p40. Gliomas have a paucity of immune cellular infiltrate, suggesting that immune cells from the periphery may have less effect on the tumor microenvironment than in other tumor types. On the other hand, cytokines pass into the CSF readily and thus may have a more profound effect on the local glioma immune microenvironment [13]. BEV has been used as an adjuvant to immunotherapy in recent clinical trials (NCT01814813, NCT01498328, NCT02337491). Our study highlights the immunomodulatory effects of BEV on circulating cytokines and peripheral blood immune subsets.

The influence of anti-angiogenic therapy on the immune system is controversial. Consistent with our results, a decrease in Tregs following anti-angiogenic therapy has been reported in humans [11, 12, 14], suggesting that this treatment may lessen this form of immune suppression. The mechanism of Treg suppression from VEGF blockade is unclear. The increase in Tregs in proliferating tumors may be due either to conversion of conventional T cells to Tregs, or to proliferation of existing Tregs. Consistent with this hypothesis, sunitinib, a VEGFR-avid tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has been shown to decrease the proportion of Tregs in a mouse model of colorectal cancer [12]. Sunitinib inhibits phosphorylation of STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) in melanoma-bearing mice [15], and as such, VEGF blockade may inhibit the conversion of CD4+/FOXP3− T cells to CD4+/FOXP3+Tregs through STAT3 inhibition. Another potential mechanism is that tumor-derived VEGF-A directly stimulates proliferation of Tregs, and VEGF/VEGFR-targeted therapy inhibits this activation [12]. BEV has been shown to decrease the proportion of Tregs in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer [12]. However, we also show that BEV induces significant CD4+ lymphopenia, which has been correlated with reduced survival in patients with glioblastoma [16] and may inhibit immune response.

In our study, VEGF blockade did not decrease circulating suppressive MDSCs (Lineage-HLADR-CD11b+CD33+), which is similar to what was observed in patients with renal cell carcinoma treated with BEV [17]. We also measured changes in myeloid- and plasmacytoid-derived dendritic cells and immature dendritic cells, but did not find any significant changes after treatment. BEV treatment induced a significant decrease in the absolute number of immune cells with effector function; cytotoxic CD8 T cells (CD8+CD107a+) [18], and cells that reflect thymic competence, CD4+ CD31+recent thymic emigrant T cells [19]. The overall mononuclear cell-profile shifts in peripheral blood of patients with glioblastoma treated with VEGF blockade may favor systemic immune suppression.

We and others have found a seemingly counter-intuitive increase in the circulating concentration of soluble VEGF-A following treatment with BEV [20–24]. In a study of patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma treated with cediranib, a VEGFR2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor, plasma VEGF and PlGF concentrations were found to rise during treatment [25, 26], similar to our results. Some have proposed that increases in VEGF after BEV may reflect both free and antibody-bound protein [21, 24], but this would not explain the increases in circulating VEGF following treatment with anti-angiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibitors [20, 26]. Additionally, in a control experiment using the same assay methodology we utilized, Willett and colleagues added varying concentrations of BEV to plasma, demonstrating that saturation with BEV produced a near-complete loss of detectable VEGF [27]. This provides evidence that VEGF bound to BEV is not detected by this assay system and only free VEGF is quantified. The mechanism for the increase in circulating VEGF has not been elucidated, though it has been consistently recognized. A systems biology study created a pharmacokinetic model to provide insight into the mechanism of action of anti-VEGF agents [28]. The model suggested that intravenous BEV could extravasate and bind to interstitial VEGF. When the VEGF-BEV complex then intravastated, it could dissociate, thereby releasing VEGF and increasing circulating VEGF concentrations. Others have suggested that a decrease in VEGF degradation by proteases of up to threefold in the presence of BEV may contribute to the increase in plasma concentrations [29]. Additionally, platelets may independently release VEGF in the presence of BEV, further driving the increase in circulating VEGF concentrations [30].

In addition to increased VEGF, we saw a significant rise in plasma concentrations of PlGF and IL-12p40. Similar to VEGF, PlGF is a pro-angiogenic growth factor that can modulate the intratumoral immune microenvironment, by binding to VEGFR, which blocks the activation of NF-κB and thereby inhibits DC maturation [5]. Through this mechanism, PlGF has an immunosuppressive effect. Our results confirm that the increases in circulating VEGF and PlGF that we observed are specific to treatment with BEV, since we did not see these growth factors increase following treatment with only standard RT and TMZ. On the contrary, a treatment-related increase in IL-12p40 was seen in both the BEV-treated cohort and the control group. These data suggest that the addition of BEV induces a more immune suppressive cytokine/growth factor profile.

The high doses of anti-angiogenic therapy used in glioblastoma may account for its immune effects [10]. Standard doses in glioblastoma (BEV 10 mg/kg q 2 weeks) are high compared with other anticancer regimens. A recent retrospective study using BEV to treat patients with recurrent glioblastoma suggested that lower doses than the FDA approved dose may be associated with improved survival [31]. It remains to be determined whether low and high doses of BEV will have a differential effect on the immune system and whether a dose can be identified that does not suppress but may enhance the effect of immunotherapy in glioblastoma.

Our study has several limitations. When we began this study, phase III clinical trials of BEV for newly diagnosed glioblastoma were underway. These studies did not show an overall survival benefit [32, 33], and thus, the clinical use of BEV is largely limited to the recurrence setting, which was not examined here. In this study, we examined the effect of BEV in combination with 2 treatments (radiation and chemotherapy) that each exerts an immunosuppressive effect. Our sample size was calculated to study the effect of BEV on Tregs, and therefore, it is possible that there are BEV-induced changes in the immune system of significance for immunotherapy that could not be detected in our 11 patients. Finally, our study examines immune changes in peripheral blood, which may not accurately reflect the tumor microenvironment.

Conclusions

In conclusion, treatment of patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma with RT, TMZ, and BEV resulted in an increase in key immunosuppressive cytokines and prompted a shift in peripheral blood immune cell subsets toward a more immune suppressive profile. The overall effect of anti-angiogenic therapies on the peripheral blood immune environment and the tumor microenvironment in patients with glioblastoma needs further exploration in parallel with studies of ongoing immunotherapy. Optimization of combination therapy must minimize immune suppression to ultimately translate into improved outcomes for patients with glioblastoma.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank DartLab: Immunoassay and Flow Cytometry Shared Resource at The Norris Cotton Cancer Center and Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, for the use of the MacsQuant10 flow cytometer and the MSD Sector Imager 2400 instrument. The DartLab is supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (NCI, 5 P30 CA023108-36) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS, 8 P30 GM103415-14) Grants awarded to the Norris Cotton Cancer Center. This work was supported by grants to Camilo Fadul from Genentech and the Norris Cotton Cancer Center Brain Tumor Research Fund. Lionel Lewis was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (NCI, 5 P30 CA023108-36) and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS, U10 CA151662-03) through the National Institutes of Health. Thomas Hampton was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH, RO1 HL074175).

Abbreviations

- ACD

Acid, citrate, dextrose

- BEV

Bevacizumab

- bFGF

Beta-fibroblast growth factor

- CBC

Complete blood count

- CD

Cluster of differentiation

- CTCAE

Common terminology criteria for adverse events

- CTEP

Cancer therapy evaluation program

- DC

Dendritic cell

- FDA

Federal Drug Administration

- FOXP3

Forkhead box P3

- GMCSF

Granulocyte–monocyte colony-stimulating factor

- HIF

Hypoxia-inducible factor

- HLA

Human leukocyte antigen

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- IL

Interleukin

- KPS

Karnofsky performance scale

- L/D

Live/dead

- MDSC

Myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- MSD

MESO Scale Discovery

- NCI

National Cancer Institute

- OS

Overall survival

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- PlGF

Placental growth factor

- RT

Radiation therapy

- SDF-1α

Stromal cell-derived factor 1-alpha

- sFlt-1

Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1

- STAT3

Signal transducer and activator of transcription

- TMZ

Temozolomide

- TNFα

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- Tregs

Regulatory T cells

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFR

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Fadul CE, Fisher JL, Gui J, Hampton TH, Cote AL, Ernstoff MS. Immune modulation effects of concomitant temozolomide and radiation therapy on peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13(4):393–400. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt NO, Westphal M, Hagel C, Ergun S, Stavrou D, Rosen EM, Lamszus K. Levels of vascular endothelial growth factor, hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor and basic fibroblast growth factor in human gliomas and their relation to angiogenesis. Int J Cancer. 1999;84(1):10–18. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990219)84:1<10::AID-IJC3>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi S. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), VEGF receptors and their inhibitors for antiangiogenic tumor therapy. Biol Pharm Bull. 2011;34(12):1785–1788. doi: 10.1248/bpb.34.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voron T, Colussi O, Marcheteau E, Pernot S, Nizard M, Pointet AL, Latreche S, Bergaya S, Benhamouda N, Tanchot C, Stockmann C, Combe P, Berger A, Zinzindohoue F, Yagita H, Tartour E, Taieb J, Terme M. VEGF-A modulates expression of inhibitory checkpoints on CD8+T cells in tumors. J Exp Med. 2015;212(2):139–148. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voron T, Marcheteau E, Pernot S, Colussi O, Tartour E, Taieb J, Terme M. Control of the immune response by pro-angiogenic factors. Front Oncol. 2014;4:70. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alfaro C, Suarez N, Gonzalez A, Solano S, Erro L, Dubrot J, Palazon A, Hervas-Stubbs S, Gurpide A, Lopez-Picazo JM, Grande-Pulido E, Melero I, Perez-Gracia JL. Influence of bevacizumab, sunitinib and sorafenib as single agents or in combination on the inhibitory effects of VEGF on human dendritic cell differentiation from monocytes. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(7):1111–1119. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kusmartsev S, Gabrilovich DI. Immature myeloid cells and cancer-associated immune suppression. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2002;51(6):293–298. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0280-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohm JE, Gabrilovich DI, Sempowski GD, Kisseleva E, Parman KS, Nadaf S, Carbone DP. VEGF inhibits T-cell development and may contribute to tumor-induced immune suppression. Blood. 2003;101(12):4878–4886. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osada T, Chong G, Tansik R, Hong T, Spector N, Kumar R, Hurwitz HI, Dev I, Nixon AB, Lyerly HK, Clay T, Morse MA. The effect of anti-VEGF therapy on immature myeloid cell and dendritic cells in cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57(8):1115–1124. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0441-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang Y, Yuan J, Righi E, Kamoun WS, Ancukiewicz M, Nezivar J, Santosuosso M, Martin JD, Martin MR, Vianello F, Leblanc P, Munn LL, Huang P, Duda DG, Fukumura D, Jain RK, Poznansky MC. Vascular normalizing doses of antiangiogenic treatment reprogram the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and enhance immunotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(43):17561–17566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215397109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terme M, Pernot S, Marcheteau E, Sandoval F, Benhamouda N, Colussi O, Dubreuil O, Carpentier AF, Tartour E, Taieb J. VEGFA–VEGFR pathway blockade inhibits tumor-induced regulatory T-cell proliferation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73(2):539–549. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terme M, Tartour E, Taieb J. VEGFA/VEGFR2-targeted therapies prevent the VEGFA-induced proliferation of regulatory T cells in cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(8):e25156. doi: 10.4161/onci.25156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarthy KF, Connor TJ, McCrory C. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of vascular endothelial growth factor correlate with reported pain and are reduced by spinal cord stimulation in patients with failed back surgery syndrome. Neuromodulation. 2013;16(6):519–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1403.2012.00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adotevi O, Pere H, Ravel P, Haicheur N, Badoual C, Merillon N, Medioni J, Peyrard S, Roncelin S, Verkarre V, Mejean A, Fridman WH, Oudard S, Tartour E. A decrease of regulatory T cells correlates with overall survival after sunitinib-based antiangiogenic therapy in metastatic renal cancer patients. J Immunother. 2010;33(9):991–998. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181f4c208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kujawski M, Zhang C, Herrmann A, Reckamp K, Scuto A, Jensen M, Deng J, Forman S, Figlin R, Yu H. Targeting STAT3 in adoptively transferred T cells promotes their in vivo expansion and antitumor effects. Cancer Res. 2010;70(23):9599–9610. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grossman SA, Ye X, Lesser G, Sloan A, Carraway H, Desideri S, Piantadosi S. Immunosuppression in patients with high-grade gliomas treated with radiation and temozolomide. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(16):5473–5480. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez PC, Ernstoff MS, Hernandez C, Atkins M, Zabaleta J, Sierra R, Ochoa AC. Arginase I-producing myeloid-derived suppressor cells in renal cell carcinoma are a subpopulation of activated granulocytes. Cancer Res. 2009;69(4):1553–1560. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Betts MR, Brenchley JM, Price DA, De Rosa SC, Douek DC, Roederer M, Koup RA. Sensitive and viable identification of antigen-specific CD8+T cells by a flow cytometric assay for degranulation. J Immunol Methods. 2003;281(1–2):65–78. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(03)00265-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohler S, Thiel A. Life after the thymus: CD31+ and CD31− human naive CD4+T-cell subsets. Blood. 2009;113(4):769–774. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-139154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain RK, Duda DG, Willett CG, Sahani DV, Zhu AX, Loeffler JS, Batchelor TT, Sorensen AG. Biomarkers of response and resistance to antiangiogenic therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6(6):327–338. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Segerstrom L, Fuchs D, Backman U, Holmquist K, Christofferson R, Azarbayjani F. The anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab potently reduces the growth rate of high-risk neuroblastoma xenografts. Pediatr Res. 2006;60(5):576–581. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000242494.94000.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramcharan KS, Lip GY, Stonelake PS, Blann AD. Effect of standard chemotherapy and antiangiogenic therapy on plasma markers and endothelial cells in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(9):1742–1749. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willett CG, Boucher Y, Duda DG, di Tomaso E, Munn LL, Tong RT, Kozin SV, Petit L, Jain RK, Chung DC, Sahani DV, Kalva SP, Cohen KS, Scadden DT, Fischman AJ, Clark JW, Ryan DP, Zhu AX, Blaszkowsky LS, Shellito PC, Mino-Kenudson M, Lauwers GY. Surrogate markers for antiangiogenic therapy and dose-limiting toxicities for bevacizumab with radiation and chemotherapy: continued experience of a phase I trial in rectal cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):8136–8139. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.5635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang JC, Haworth L, Sherry RM, Hwu P, Schwartzentruber DJ, Topalian SL, Steinberg SM, Chen HX, Rosenberg SA. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(5):427–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Batchelor TT, Mulholland P, Neyns B, Nabors LB, Campone M, Wick A, Mason W, Mikkelsen T, Phuphanich S, Ashby LS, Degroot J, Gattamaneni R, Cher L, Rosenthal M, Payer F, Jurgensmeier JM, Jain RK, Sorensen AG, Xu J, Liu Q, van den Bent M. Phase III randomized trial comparing the efficacy of cediranib as monotherapy, and in combination with lomustine, versus lomustine alone in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(26):3212–3218. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.2464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Batchelor TT, Gerstner ER, Emblem KE, Duda DG, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Snuderl M, Ancukiewicz M, Polaskova P, Pinho MC, Jennings D, Plotkin SR, Chi AS, Eichler AF, Dietrich J, Hochberg FH, Lu-Emerson C, Iafrate AJ, Ivy SP, Rosen BR, Loeffler JS, Wen PY, Sorensen AG, Jain RK. Improved tumor oxygenation and survival in glioblastoma patients who show increased blood perfusion after cediranib and chemoradiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(47):19059–19064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318022110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willett CG, Duda DG, di Tomaso E, Boucher Y, Ancukiewicz M, Sahani DV, Lahdenranta J, Chung DC, Fischman AJ, Lauwers GY, Shellito P, Czito BG, Wong TZ, Paulson E, Poleski M, Vujaskovic Z, Bentley R, Chen HX, Clark JW, Jain RK. Efficacy, safety, and biomarkers of neoadjuvant bevacizumab, radiation therapy, and fluorouracil in rectal cancer: a multidisciplinary phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(18):3020–3026. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stefanini MO, Wu FT, Mac Gabhann F, Popel AS. Increase of plasma VEGF after intravenous administration of bevacizumab is predicted by a pharmacokinetic model. Cancer Res. 2010;70(23):9886–9894. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsei V, Deguzman GG, Nixon A, Gaudreault J. Complexation of VEGF with bevacizumab decreases VEGF clearance in rats. Pharm Res. 2002;19(11):1753–1756. doi: 10.1023/A:1020778001267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klement GL, Yip TT, Cassiola F, Kikuchi L, Cervi D, Podust V, Italiano JE, Wheatley E, Abou-Slaybi A, Bender E, Almog N, Kieran MW, Folkman J. Platelets actively sequester angiogenesis regulators. Blood. 2009;113(12):2835–2842. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-159541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levin VA, Mendelssohn ND, Chan J, Stovall MC, Peak SJ, Yee JL, Hui RL, Chen DM. Impact of bevacizumab administered dose on overall survival of patients with progressive glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2015;122(1):145–150. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1693-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chinot OL, Wick W, Mason W, Henriksson R, Saran F, Nishikawa R, Carpentier AF, Hoang-Xuan K, Kavan P, Cernea D, Brandes AA, Hilton M, Abrey L, Cloughesy T. Bevacizumab plus radiotherapy-temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):709–722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilbert MR, Dignam JJ, Armstrong TS, Wefel JS, Blumenthal DT, Vogelbaum MA, Colman H, Chakravarti A, Pugh S, Won M, Jeraj R, Brown PD, Jaeckle KA, Schiff D, Stieber VW, Brachman DG, Werner-Wasik M, Tremont-Lukats IW, Sulman EP, Aldape KD, Curran WJ, Jr, Mehta MP. A randomized trial of bevacizumab for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):699–708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.