Abstract

Background

Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) has been shown to be a prognosis indicator in different types of cancer. We aimed to investigate the association between NLR and therapy response, progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients treated with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy.

Methods

Patients who were hospitalized between January 2007 and December 2010 were enrolled and eliminated according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The NLR was defined as the absolute neutrophil count divided by the absolute lymphocyte count. Logistic regression analysis was applied for response rate and Cox regression analysis was adopted for PFS and OS. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

A total of 182 patients were enrolled in the current study. The median PFS was 164.5 days and median OS was 439.5 days. The statistical analysis data indicated that low pretreatment NLR (≤ 2.63) (OR = 2.043, P = 0.043), decreased posttreatment NLR (OR = 2.368, P = 0.013), well and moderate differentiation (OR = 2.773, P = 0.021) and normal CEA level (≤ 9.6 ng/ml) (OR = 2.090, P = 0.046) were associated with response to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. A high pretreatment NLR (HR = 1.807, P = 0.018 for PFS, HR = 1.761, P = 0.020 for OS) and distant metastasis (HR = 2.118, P = 0.008 for PFS, HR = 2.753, P = 0.000 for OS) were independent prognostic factors for PFS and OS.

Conclusion

Elevated pretreatment NLR might be a potential biomarker of worse response to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy and shorter PFS and OS for advanced NSCLC patients. To confirm these findings, larger, prospective and randomized studies are needed.

Keywords: Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, Prognostic factor, Tumor-related inflammation, Non-small cell lung cancer

Introduction

Lung cancer is the one of the leading causes of cancer-associated death in the world and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) compromises the majority of lung cancer [1]. Despite the marked progress in etiology and pharmacotherapy research, the five-year survival rate in most NSCLC patients still leaves much to be desired [1, 2]. The major NSCLC patients are diagnosed at a relatively late stage, and the recurrence is common even after surgical resection [3]. Platinum-based first-line chemotherapy is prescribed as a part of standard treatment for advanced NSCLC patients, consisted of platinum with third-generation chemotherapy agent such as docetaxel, pemetrexed and gemcitabine. Although various factors for prognosis of lung cancer and different predictive factors for response to different agents are identified in previous studies [2, 3], there is still no promising predictive factor that can be simply detected and closely linked to clinical treatment response and survival for advanced NSCLC patients [4].

Tumor inflammation and immunology are recently identified as enabling cancer characteristics and play important roles in tumor progression and metastasis [5]. Neutrophils, as well as T and B lymphocytes are suggested to play a prominent role in the tumor inflammation and immunology [6, 7]. Recently, elevated preoperative or pretreatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) detected in peripheral blood was identified as an independent prognostic factor associated with poor survival in various cancers, including colon cancer, esophageal cancer, gastric cancer and breast cancer [8–14]. The pretreatment NLR was also found to be a biomarker for survival in patients treated with systematic chemotherapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer and gastric cancer [11, 15–17]. In early NSCLC patients, Sarraf et al. and Tomita et al. [18, 19] proved that high level of NLR indicated high recurrence after complete or curative resection. As a marker of inflammation and immunology, NLR is highly repeatable, inexpensive and widely available. However, there is still no evidence determining whether NLR is associated with survival and efficiency of chemotherapy of advanced NSCLC patients.

The aim of the present study was to study the association between the pretreatment NLR and the response to treatment, and survival of patients with advanced NSCLC.

Patients and methods

Patient eligibility

This study was conducted at the department of respiratory medicine, Jinling Hospital (Nanjing, Jiangsu, China). The research proposal has been approved by chairman of the ethics committee. Patients who were hospitalized between January 2007 and December 2010 were enrolled. The inclusion criteria are: (1) all included patients were hospitalized for the primary diagnosis, therapy naïve; (2) patients were histologically or cytologically diagnosed as primary NSCLC and staged according to the tumor–node–metastasis (TNM) criteria (AJCC criteria 2009); (3) patients were in stage IIIB and IV, including those in stage IIIA but was not suitable for surgery; (4) patients took at least two cycles of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy and a response evaluation after treatment; (5) all the clinical data of patients should be available. Patients were excluded if they (1) were SCLC or not primary lung cancer patients; (2) cannot provide detailed and needed clinical data; (3) had clinical evidence of infection, other inflammation, hematology disease or used hematology influenced drugs within one month; (4) had radiation therapy, surgery, pulmonary embolism (PE), acute myocardial infarction (AMI) or cerebrovascular accident (CVA) within one month; (5) were in stage I, stage II and stage IIIA which could be resected; (6) took single agent chemotherapy or targeted therapy or none treatment; (7) did not have a response evaluation; (7) lost contact during the follow-up time.

Clinical and laboratory data collection

Age, gender, smoking status, histology, stage, differentiation and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status Scale (ECOG PS) were recorded for all NSCLC patients. First-line platinum-based chemotherapy was administered intravenously consisted of platinum with third-generation chemotherapy agent such as docetaxel, pemetrexed and gemcitabine on day 1 or day 1 and day 5. After a 21-day interval, the same regimens were repeated. A therapy response evaluation by whole body tumor scans was taken after two courses. Treatment was continued until evidence of disease progression on scans, unacceptable adverse events or death.

Follow-up time was defined as the time from chemotherapy initiation to 31st October 2011. The Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 was applied for the evaluation of response [20]. The responses were assessed by independent radiologists and treating physicians, and reviewed by the investigator Yanwen YAO. Progression free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from the chemotherapy initiation until disease progressed or death of any cause. If the patients were dead during the follow-up time, overall survival (OS) was defined as the interval between the date of diagnosis and the date of death. Otherwise, OS time was defined as the interval time between the date of diagnosis and 31st October 2011.

For all study subjects, differential leukocyte counts were recorded before diagnosis or 1 day prior to chemotherapy. Blood samples were collected in 5 ml EDTA-K2 preservative tubes, stored at room temperature and processed within 48 h. The data were provided from the differential white cell count output from a hematology analyzer, XE-2100 (SySmex, Kobe, Japan). The NLR was defined as the absolute neutrophil count divided by the absolute lymphocyte count.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software program version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were summarized with the number of subjects and the mean or median value. A receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve was constructed to estimate the optimal cut-off value of pretreatment NLR and other variables. Chi-squared test was performed to compare baseline clinical characteristics between patients in different groups. Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis H test was used to compare categorical end points and two-sample t test was used to compare continuous variables after data transformation.

Univariate analysis was performed to determine the significance of variables using logistic regression model for response rate and Cox regression model for PFS and OS. Survival curve was estimated by Kaplan–Meier analysis and the log-rank test was utilized to examine the significance of the differences of survival distributions between groups. Subsequently, the variables with P ≤ 0.05 enter into multivariate analysis. Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to determine the independent prognostic factors. Generally, a P value of ≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

Baseline patient characteristics

According to the inclusion criteria, 196 NSCLC patients who were at stage III and IV took at least two cycles of first-line platinum-based combination chemotherapy, and a response evaluation after treatment were left in the current study. One hundred and eighty-two patients were finally enrolled into the study by further referring to the exclusion criteria, excluding 6 patients who had the clinical evidence of pneumonia, 2 patients had anemia, 2 patients took glucocorticoid and 2 patients who were injected granulocyte colony stimulating factor (GCSF) within 1 month before the first cycle of treatment. None of the patients took the radiation therapy and surgery or had PE, AMI or CVA before the first two cycles of chemotherapy. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean age was 58.9 years for all the patients, and 119 patients were males (65.4 %). The number of patients in stage III and IV was 58 and 124, respectively. In patients at stage IV, the most common metastatic site was bone (51, 35.4 %), followed by pleura (27, 18.7 %), brain (26, 18.0 %), intrapulmonary metastasis (24, 16.7 %), adrenal gland (8, 5.6 %) and other sites (8, 5.6 %). Eighteen patients had more than 2 metastasis sites.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and therapy responses of all 182 advanced NSCLC patients

| Characteristic | Data |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 182 |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean ± SD (range; median) | 58.9 ± 10.8 (28–79; 61) |

| Gender | |

| Female/male | 63 (34.6 %)/119 (65.4 %) |

| Smoke status | |

| Non-smoker/smoker | 91 (50 %)/91 (50 %) |

| Histology | |

| AC/SCC/other | 128 (70.3 %)/48 (26.4 %)/6 (3.3 %) |

| Differentiation | |

| Well/moderate/poor | 28 (15.4 %)/20 (11.0 %)/134 (73.6 %) |

| Tumor stage | |

| T1/T2/T3/T4 | 26 (14.3 %)/63 (34.6 %)/10 (5.5 %)/83 (45.6 %) |

| Node stage | |

| N0/N1/N2/N3 | 30 (16.5 %)/14 (7.7 %)/90 (49.5 %)/48 (26.3 %) |

| Metastasis stage | |

| M0/M1a/M1b | 58 (31.9 %)/50 (27.5 %)/74 (40.7 %) |

| Metastasis sites | |

| Intra-lung/pleura/bones/brain/adrenal gland/liver/other | 24 (16.7 %)/27 (18.7 %)/51 (35.4 %)/26 (18.0 %)/8 (5.6 %)/4 (2.8 %)/4 (2.8 %) |

| TNM stage | |

| III/IV | 58 (31.9 %)/124 (68.1 %) |

| ECOG PS | |

| 0–1/>1 | 162 (89.0 %)/20 (11.0 %) |

| WBC count (×109/L) | 6.91 ± 1.89 |

| Neutrophil count (×109/L) | 4.61 ± 1.72 |

| Lymphocyte count (×109/L) | 1.57 ± 0.58 |

| Monocyte count (×109/L) | 0.46 ± 0.18 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 14.92 ± 23.45 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 41.74 ± 11.3 |

| Chemotherapy | |

| DP/AP/GP | 124 (68.1 %)/20 (11.0 %)/38 (20.9 %) |

| Clinical response | |

| CR/PR/SD/PD | 2 (1.1 %)/45 (24.7 %)/77 (42.3 %)/58 (31.9 %) |

| PFS (days) median/mean ± SD | 164.5/253.6 ± 242.4 |

| OS (days) median/mean ± SD | 439.5/542.7 ± 352.1 |

NSCLC non-small cell lung cancer, AC adenocarcinoma, SCC squamous carcinoma, TNM tumor–node–metastasis, ECOG PS Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, WBC white blood cell, CRP C-reactive protein, CEA carcinoma embryonic antigen, DP docetaxel combined with platinum, AP pemetrexed combined with platinum, GP gemcitabine combined with platinum, CR complete response, PR partial response, SD stable disease, PD progressive disease

A total of 182 patients received platinum-based chemotherapy according to the tumor histology, including 124 patients received docetaxel combined with platinum therapy, 20 patients received pemetrexed combined with platinum therapy and left 38 patients received gemcitabine combined with platinum therapy. After two courses of 21-day treatment interval, patients took whole body tumor scan and clinical response was evaluated. Among these patients, 2 (1.1 %) patients got complete response (CR), 45 (24.7 %) patients had partial response (PR), 58 (31.9 %) patients had progressive disease (PD) and 77 (42.3 %) patients had stable disease (SD). Ninety-one (50.0 %) patients survived till 31st October 2011. The median PFS of all 182 patients was 164.5 days and the median OS was 439.5 days.

NLR analysis

According to the ROC curve, the best cut-off value of NLR was 2.63, with a sensitivity of 62.2 % and a specificity of 59.3 %. One hundred and one patients (55.5 %) had an elevated pretreatment NLR (>2.63) identified as high NLR group and eighty-one patients (45.5 %) was identified as low NLR group. The distribution of clinical characteristics for NLR subgroup is presented in Table 2. Patients with pretreatment NLR >2.63 had high ECOG PS (P = 0.019), low response rate to treatment (P = 0.029), a higher prevalence of poor differentiation and were males (P = 0.056 and 0.062, respectively). Median PFS in patients with pretreatment NLR ≤2.63 was 238.0 days (mean ± SD, 291.1 ± 238.1) compared with 164.0 days (2,240.4 ± 192.7) in patients with NLR > 2.63 (P = 0.040). Median OS in NLR ≤2.63 group and NLR >2.63 group was 537.0 days (584.1 ± 305.7) and 435.0 days (490.0 ± 310.1), respectively (P = 0.008).

Table 2.

Distribution of clinical characteristics stratified by pretreatment NLR

| Characteristic | NLR ≤2.63 (N = 81) |

NLR >2.63 (N = 101) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 57.9 ± 11.2 | 59.6 ± 10.5 | 0.372 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 34 (42.0 %) | 29 (28.7 %) | 0.062 |

| Male | 47 (58.0 %) | 72 (71.3 %) | |

| Smoke status | |||

| Non-smoker | 46 (56.8 %) | 45 (44.6 %) | 0.101 |

| Smoker | 35 (43.2 %) | 56 (55.4 %) | |

| Histology | |||

| AC | 60 (74.1 %) | 68 (67.3 %) | 0.322 |

| SCC and others | 21 (25.9 %) | 33 (32.7 %) | |

| Differentiation | |||

| Well/moderate | 27 (33.3 %) | 21 (20.8 %) | 0.056 |

| Poor | 54 (66.7 %) | 80 (79.2 %) | |

| Tumor stage | |||

|

T1/T2/ T3/T4 |

12 (14.8 %)/33 (40.7 %)/ 3 (3.7 %)/33 (40.7 %) |

14 (13.9 %)/30 (29.7 %)/ 7 (6.9 %)/50 (49.5 %) |

0.359 |

| Node stage | |||

|

N0/N1/ N2/N3 |

17 (21.3 %)/9 (11.3 %)/ 37 (46.3 %)/17 (21.3 %) |

13 (12.7 %)/5 (4.9 %)/ 53 (52.0 %)/31 (304 %) |

0.086 |

| Metastasis stage | |||

| M0 | 22 (27.2 %) | 36 (35.6 %) | 0.430 |

| M1a | 25 (30.9 %) | 25 (24.8 %) | |

| M1b | 34 (42.0 %) | 40 (39.6 %) | |

| Tumor stage | |||

| III | 21 (25.9 %) | 37 (36.6 %) | 0.123 |

| IV | 60 (74.1 %) | 64 (63.4 %) | |

| ECOG PS | |||

| 0–1 | 77 (95.1 %) | 85 (84.2 %) | 0.019 |

| >1 | 4 (4.9 %) | 16 (15.8 %) | |

| Clinical response | |||

| CR/PR/SD | 62 (76.5 %) | 62 (61.4 %) | 0.029 |

| PD | 19 (23.5 %) | 39 (38.6 %) | |

| PFS (days) | |||

| Median/mean ± SD | 238.0/291.1 ± 238.1 | 164.0/220.4 ± 192.7 | 0.040 |

| OS (days) | |||

| Median/mean ± SD | 537.0/584.1 ± 305.7 | 435.0/490.0 ± 310.1 | 0.008 |

AC adenocarcinoma, SCC squamous carcinoma, TNM tumor–node–metastasis, ECOG PS Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, CR complete response, PR partial response, SD stable disease, PD progressive disease, PFS progression free survival, OS overall survival

Other hematology factors analysis

Other hematology index such as white blood cell (WBC) count, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, monocyte count, inflammation factor C-reactive protein (CRP) and tumor biomarker carcinoma embryonic antigen (CEA) were also analyzed. ROC curves for these continuous variables showed that only monocyte count and CRP had significant P value. The best cut-off value for monocyte count and CRP was 0.44 × 109/mL and 3.65 μg/L, respectively.

Patients with pretreatment monocyte count >0.44 × 109/L had a higher prevalence of males (P = 0.000), smokers (P = 0.000), high ECOG PS (P = 0.007) and advanced tumor stage (P = 0.049), while patients with pretreatment CRP >3.65 mg/L only had more advanced tumor stage and node stage (P = 0.021 and 0.025, respectively).

Univariate response rate and survival analysis

Low pretreatment NLR ≤2.63 (odd ratio (OR) = 2.053, 95 % confidence interval, CI 1.070–3.938, P = 0.031), well and moderate differentiation (OR = 2.498, 95 %CI 1.116–5.590, P = 0.026) and normal CEA level (≤9.6 ng/ml) (OR = 2.547, 95 %CI 1.067–6.081, P = 0.035) were associated with response to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy (CR, PR, SD vs. PD) at first evaluation. Posttreatment NLR was recorded after two treatment cycles and decreased NLR was also associated with treatment response (OR = 2.195, 95 %CI 1.154–4.174, P = 0.017).

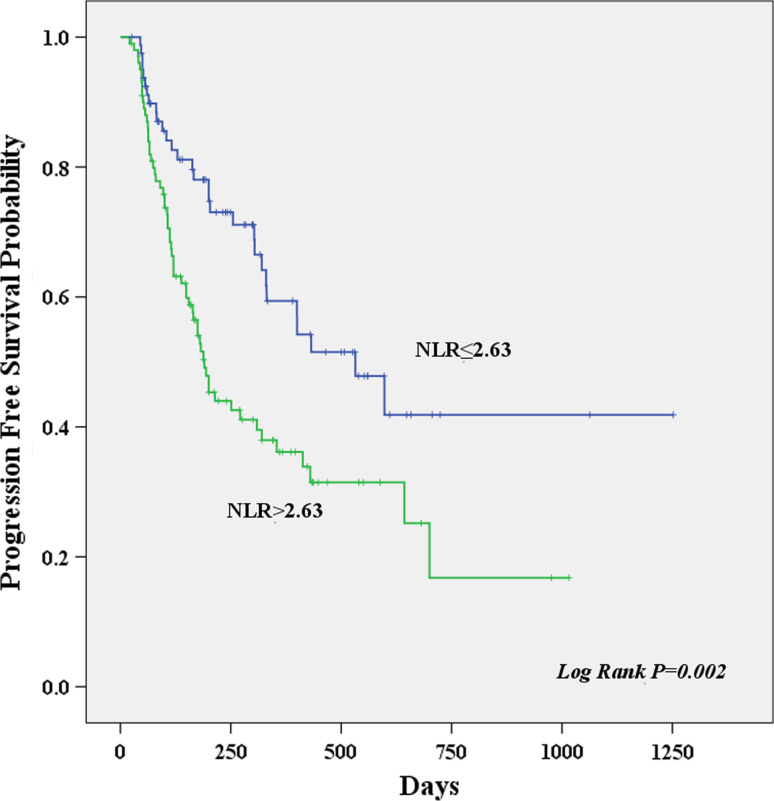

Result of univariate survival analysis demonstrated that NLR was a prognostic predictor. A high pretreatment NLR >2.63 was associated with worse PFS (hazard ratio (HR) = 2.004, P = 0.002). Other PFS prognostic variables presented in Table 3 were node stage 3 (HR = 3.065, P = 0.003), distant metastasis (HR = 2.186, P = 0.003), advanced stage (HR = 1.651, P = 0.041) high CRP >3.65 (HR = 2.135, P = 0.004) and monocyte count (HR = 1.708 P = 0.012). A high pretreatment NLR >2.63 (HR = 2.036, P = 0.001), male (HR = 1.652, P = 0.030), smoker (HR = 1.568, P = 0.036), poor differentiation (HR = 1.719, P = 0.044), node stage 3 (HR = 3.552, P = 0.001), distant metastasis (HR = 2.217, P = 0.003), high CRP > 3.65 (HR = 2.119, P = 0.004) and monocyte count (HR = 1.776, P = 0.007) were associated with worse OS. The Kaplan–Meier curves of PFS and OS stratified by pretreatment NLR are shown in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 3.

Result of univariate analysis and regarding PFS and OS in 182 advanced NSCLC patients

| Variables | PFS | OS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95 % CI | P value | HR | 95 % CI | P value | |

| NLR | ||||||

| ≤2.63 (n = 81) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| >2.63 (n = 101) | 2.004 | 1.292–3.109 | 0.002 | 2.036 | 1.314–3.156 | 0.001 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female (n = 63) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Male (n = 119) | 1.306 | 0.832–2.048 | 0.245 | 1.652 | 1.050–2.599 | 0.030 |

| Smoke status | ||||||

| Non-smoker (n = 91) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Smoker (n = 91) | 1.118 | 0.739–1.691 | 0.597 | 1.568 | 1.029–2.389 | 0.036 |

| ECOG PS | ||||||

| 0–1 (n = 162) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| >1 (n = 20) | 1.487 | 0.840–2.630 | 0.173 | 1.366 | 0.768–2.431 | 0.289 |

| Histology | ||||||

| AC (n = 128) | 1 | |||||

| SCC/others (n = 54) | 0.847 | 0.539–1.329 | 0.470 | 0.944 | 0.602–1.482 | 0.803 |

| Differentiation | ||||||

| Well/moderate (n = 48) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Poor (n = 134) | 1.606 | 0.947–2.724 | 0.079 | 1.719 | 1.014–2.916 | 0.044 |

| Tumor stage | ||||||

| T1 (n = 26) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| T2 (n = 63) | 0.778 | 0.387–1.564 | 0.480 | 1.030 | 0.515–2.059 | 0.934 |

| T3 (n = 10) | 0.789 | 0.251–2.482 | 0.686 | 1.037 | 0.329–3.262 | 0.951 |

| T4 (n = 83) | 1.413 | 0.732–2.729 | 0.303 | 1.416 | 0.733–2.735 | 0.301 |

| Node stage | ||||||

| N0 (n = 30) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| N1 (n = 14) | 2.305 | 0.857–6.023 | 0.098 | 2.189 | 0.809–5.918 | 0.123 |

| N2 (n = 90) | 1.546 | 0.753–3.175 | 0.235 | 1.952 | 0.950–4.011 | 0.069 |

| N3 (n = 48) | 3.065 | 1.454–6.460 | 0.003 | 3.552 | 1.677–7.523 | 0.001 |

| Metastasis stage | ||||||

| M0 (n = 58) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| M1 (n = 50) | 1.388 | 0.766–2.513 | 0.280 | 1.165 | 0.644–2.109 | 0.614 |

| M2 (n = 74) | 2.186 | 1.302–3.669 | 0.003 | 2.217 | 1.323–3.717 | 0.003 |

| TNM stage | ||||||

| III (n = 58) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| IV (n = 124) | 1.651 | 1.020–2.670 | 0.041 | 1.560 | 0.965–2.523 | 0.070 |

| CRP (mg/L) | ||||||

| ≤3.65 (n = 124) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| >3.65 (n = 58) | 2.135 | 1.286–3.546 | 0.004 | 2.119 | 1.274–3.522 | 0.004 |

| Monocyte (× 109/L) | ||||||

| ≤0.44 (n = 97) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| >0.44 (n = 85) | 1.708 | 1.124–2.594 | 0.012 | 1.776 | 1.170–2.695 | 0.007 |

Univariate analysis was performed by the Cox regression model

NLR neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, NSCLC non-small cell lung cancer, AC adenocarcinoma, SCC squamous carcinoma, TNM tumor–node–metastasis, ECOG PS Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, PFS progression free survival, OS overall survival, CRP C-reactive protein, CEA carcinoma embryonic antigen, WBC white blood cell

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves showing progression free survival, stratified by the pretreatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves showing overall survival, stratified by the pretreatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio

Multivariate response rate and survival analysis

The significant factors in univariate response rate and survival analysis were enrolled into a multivariate logistic regression and a multivariate Cox proportional regression for the test of independent factors. The statistical analysis data indicated that low pretreatment NLR ≤2.63 (OR = 2.043, P = 0.043), decreased posttreatment NLR (OR = 2.368, P = 0.013), well and moderate differentiation (OR = 2.773, P = 0.021) and normal CEA level (≤9.6 ng/ml) (OR = 2.090, P = 0.046) were associated with response to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy (CR, PR, SD vs. PD) at first evaluation independently.

A high pretreatment NLR >2.63 (HR = 1.807, P = 0.018) and distant metastasis (HR = 2.118, P = 0.008) were independent prognostic factors for PFS and these two factors were also associated with OS independently, with HR = 1.761, P = 0.020 and HR = 2.753, P = 0.000, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Result of multivariate analysis regarding PFS and OS in 184 advanced NSCLC patients

| Variables | PFS | OS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95 %CI | P value | HR | 95 %CI | P value | |

| NLR | ||||||

| ≤2.63 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| >2.63 | 1.807 | 1.106–2.952 | 0.018 | 1.761 | 1.095-–2.832 | 0.020 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Male | 1.150 | 0.594–2.228 | 0.679 | 1.479 | 0.776–2.817 | 0.234 |

| Smoke | ||||||

| Non-smoker | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Smoker | 0.870 | 0.475–1.591 | 0.651 | 1.095 | 0.602–1.993 | 0.766 |

| Differentiation | ||||||

| Well/moderate | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Poor | 1.418 | 0.790–2.544 | 0.242 | 1.545 | 0.875–2.727 | 0.134 |

| Node stage | ||||||

| N0 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| N1 | 1.804 | 0.632–5.148 | 0.270 | 1.485 | 0.531–4.154 | 0.451 |

| N2 | 1.174 | 0.546–2.527 | 0.681 | 1.453 | 0.681–3.100 | 0.333 |

| N3 | 1.959 | 0.865–4.435 | 0.107 | 2.513 | 1.116–5.660 | 0.026 |

| Metastasis stage | ||||||

| M0 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| M1 | 1.695 | 0.913–3.146 | 0.095 | 1.819 | 0.965–3.429 | 0.064 |

| M2 | 2.118 | 1.217–3.686 | 0.008 | 2.753 | 1.574–4.815 | 0.000 |

| CRP (mg/L) | ||||||

| ≤3.65 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| >3.65 | 1.397 | 0.798–2.445 | 0.242 | 1.252 | 0.712–2.201 | 0.436 |

| Monocyte (×109/L) | ||||||

| ≤0.44 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| >0.44 | 1.445 | 0.898–2.325 | 0.130 | 1.468 | 0.909–2.369 | 0.116 |

Multivariate analysis was performed by the Cox proportional hazard model using an enter procedure

NLR neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, NSCLC non-small cell lung cancer, PFS progression free survival, OS overall survival, CRP C-reactive protein

Discussion

In the present study, NLR was demonstrated to be associated with treatment response, PFS and OS for first-line platinum-based chemotherapy-treated advanced NSCLC patients for the first time. Patients with low pretreatment NLR ≤2.63 had a better platinum-based chemotherapy response and longer PFS and OS. In multivariate survival analysis, after adjusting to the gender, smoke status, pathologic stage, CRP and monocyte count, NLR remained to be an independent factor associated with treatment response, PFS and OS. Furthermore, patients with decreased posttreatment NLR, well and moderate differentiation and normal CEA level had better response to the chemotherapy. Besides NLR, distant metastasis was also proven to be an independent prognostic factor for worse survival in the present study.

Recent clinical studies revealed that NLR was associated with prognosis in many cancers, such as breast cancer, metastasis renal carcinoma and colorectal cancer [9, 13, 16]. Research on the inflammatory tumor microenvironment supported that chronic inflammation contributed to cancer initiation, promotion, progression and invasion [7, 21]. Preclinical studies also indicated that neutrophils may act as tumor promoting leukocytes through TGF-β induced signal pathway [22]. On the other hand, lymphocytes, usually CD3 + T cells and NK cells possessed potent anti-cancer activities that could affect growth and/or metastasis in several cancers [6, 26]. All together, these evidence supported to explain the mechanism that patients with high level of NLR would have poor survival [7]. Neutrophil count or lymphocyte count alone may have limited reflection on the inflammation or immune in tumor progression, thus was not associated with survival prognosis, which was also shown in the present study [16]. NLR, taken these two factors together, played a strong predictive role in survival.

The association between NLR and clinical response to therapy was previously reported in several cancers. These studies all revealed that elevated pretreatment NLR was a predictive factor for worse therapy response [16, 23, 24]. Our observation also indicated that low NLR and decreased posttreatment NLR were independent factors for predicting better response to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy.

Previous clinical data suggested that another inflammation marker CRP was associated with prognosis of lung cancer [25]. In the present study, CRP was also proven to be a prognostic factor for PFS and OS, but not an independent one. The unknown influence of other clinicopathologic factors and NLR might be one of the reasons. Distant metastasis such as bone, brain and liver metastasis was revealed to be a strong prognostic factor for NSCLC [26]. The median survival time in patients with distant metastasis was lower than that in patients with intrapulmonary and pleura metastasis [27]. The present study again revealed that distant metastasis was an independent prognostic factor for advanced NSCLC patients.

Since it was a single-institution, retrospective study with limited number of included patients and neutrophil count or lymphocyte count can be influenced by many reasons, although we tried to reduce the influence to be small, these factors could be the limitations of this study. But our study first established a connection between NLR and advanced NSCLC patients, suggesting that NLR was an independent prognostic factor and could be the biomarker for chemotherapy response and prognosis. The clinical utility of NLR still needs to be confirmed with prospective analysis.

Conclusion

Taken together, our study first indicate that pretreatment NLR is an independent prognostic factor for advanced NSCLC patients treated with first-line platinum-based combination chemotherapy, and elevated pretreatment NLR may be a potential biomarker for worse response of chemotherapy and higher risk of death in lung cancer patients. Pretreatment evaluations based on the NLR may be easily detected and applied in routine clinical practice. Although this study was a single-institution, retrospective study, it indicates the potential role of a new biomarker for advanced NSCLC patients. To confirm these findings, we are looking forward to larger, prospective, randomized studies.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Natural Science Fund of Jiangsu Province (BK2011658) to Yong Song.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gu X, Ma C, Yuan D, et al. Circulating soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in lung cancer: a systematic review. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2012;1:36–44. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.08.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanner NT, Sherman CA, Silvestri GA. Biomarkers in the selection of maintenance therapy in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2012;1:96–98. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2012.03.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donnem T, Bremnes RM, Busund LT, et al. Gene expression assays as prognostic and predictive markers in early stage non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2012;4:212–213. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.03.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin X, Li W, Lai J, et al. Five-year update on the mouse model of orthotopic lung transplantation: scientific uses, tricks of the trade, and tips for success. J Thorac Dis. 2012;4:247–258. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.06.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 2011;331:1565–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.1203486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thavaramara T, Phaloprakarn C, Tangjitgamol S, et al. Role of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic indicator for epithelial ovarian cancer. J Med Assoc Thai. 2011;94:871–877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azab B, Bhatt VR, Phookan J, et al. Usefulness of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in predicting short- and long-term mortality in breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:217–224. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1814-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rashid F, Waraich N, Bhatti I, et al. A pre-operative elevated neutrophil: lymphocyte ratio does not predict survival from oesophageal cancer resection. World J Surg Oncol. 2010;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.An X, Ding PR, Li YH, et al. Elevated neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in advanced pancreatic cancer. Biomarkers. 2010;15:516–522. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2010.491557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gwak MS, Choi SJ, Kim JA, et al. Effects of gender on white blood cell populations and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio following gastrectomy in patients with stomach cancer. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22(Suppl):S104–S108. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.S.S104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh SR, Cook EJ, Goulder F, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2005;91:181–184. doi: 10.1002/jso.20329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharaiha RZ, Halazun KJ, Mirza F, et al. Elevated preoperative neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of postoperative disease recurrence in esophageal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:3362–3369. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1754-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho H, Hur HW, Kim SW, et al. Pre-treatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio is elevated in epithelial ovarian cancer and predicts survival after treatment. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:15–23. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0516-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keizman D, Ish-Shalom M, Huang P, et al. The association of pre-treatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio with response rate, progression free survival and overall survival of patients treated with sunitinib for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamanaka T, Matsumoto S, Teramukai S, et al. The baseline ratio of neutrophils to lymphocytes is associated with patient prognosis in advanced gastric cancer. Oncology. 2007;73:215–220. doi: 10.1159/000127412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomita M, Shimizu T, Ayabe T, et al. Preoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic predictor after curative resection for non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:2995–2998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarraf KM, Belcher E, Raevsky E, et al. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and its association with survival after complete resection in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:425–428. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki K, Kachala SS, Kadota K, et al. Prognostic immune markers in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5247–5256. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato H, Tsubosa Y, Kawano T. Correlation between the pretherapeutic neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and the pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with advanced esophageal cancer. World J Surg. 2012;36:617–622. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaneko M, Nozawa H, Sasaki K, et al. Elevated neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts poor prognosis in advanced colorectal cancer patients receiving oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy. Oncology. 2012;82:261–268. doi: 10.1159/000337228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koch A, Fohlin H, Sorenson S. Prognostic significance of C-reactive protein and smoking in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with first-line palliative chemotherapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:326–332. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31819578c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohashi R, Takahashi K, Miura K, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer–an analysis of long-term survival patients. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2006;33:1595–1602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albain KS, Crowley JJ, LeBlanc M, et al. Survival determinants in extensive-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: the Southwest Oncology Group experience. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:1618–1626. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.9.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]