Abstract

The anti-PD-1 agent, nivolumab, has been approved both as monotherapy and in combination with ipilimumab for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic melanoma in the USA and European Union. Here we present the case of a patient with treatment-naive, metastatic mucosal melanoma and baseline LDH approximately seven times the upper limit of normal. The patient was enrolled in a clinical trial (CheckMate 066) and achieved a partial response, followed by a durable complete response with nivolumab treatment. The patient’s LDH levels were documented in each cycle and dropped markedly within 2 months, when partial response to treatment was already evident. LDH levels remained low for the rest of follow-up, consistent with the ongoing complete response to treatment. The patient experienced only mild immune-related adverse events (grade 1–2), which included vitiligo and rash. This exceptional response suggests that patients with high LDH levels at baseline should be considered for nivolumab treatment. LDH levels, however, should not serve as a predictive marker of response to nivolumab. Moreover, this case suggests the need to identify patients who will achieve the greatest benefit from nivolumab monotherapy.

Keywords: Nivolumab, PD-1, Melanoma, Lactate dehydrogenase, CheckMate-066

Introduction

Prognosis for metastatic melanoma has historically been poor with high yearly mortality rates [1]. The advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors has delivered new and effective treatment options with proven clinical benefits for these patients. Nivolumab, a PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, has been approved in the USA and European Union for both first-line and previously treated patients with advanced melanoma, regardless of their BRAF mutation status as a monotherapy or in combination with ipilimumab. Monotherapy approval was based on data from two phase III studies (CheckMate 066, 037) [2, 3] that investigated nivolumab across treatment lines and BRAF mutational status; combination approval was based on data from the phase II CheckMate 069 and phase III CheckMate 067 studies [4, 5]. As a novel agent and a new treatment modality, most clinical experience with nivolumab is derived from clinical trials that evaluated its efficacy and safety, as well as demonstrated the effectiveness of managing adverse events using established treatment guidelines.

Previous and ongoing clinical trials have extensively investigated patient characteristics for their potential to predict disease course [6–8]. In addition to other factors including active brain metastases and high M stage, elevated LDH has been associated with poor survival in patients with melanoma [9]. In a recent retrospective study, LDH levels above the upper limit of normal (ULN) at baseline prior to treatment initiation with anti-PD-1 therapy (nivolumab and pembrolizumab) were associated with significantly shortened survival [10]. The same study found that changes in LDH levels during the first weeks of anti-PD-1 therapy (and prior to the first scan) were predictive of early response to therapy or disease progression in melanoma patients [10]. In line with these results, a recent biomarker study concluded that low baseline LDH (≤2.5 × ULN) levels, as well as high baseline relative eosinophil (≥1.5 %) and lymphocyte count (≥17.5 %), were associated with favorable OS [11]. Additionally, retrospective data indicated that long-term benefit from ipilimumab treatment was unlikely for patients with baseline serum LDH greater than twice the ULN [12].

Mucosal melanoma accounts for a small fraction of all melanomas and is usually highly aggressive [13]. While some progress is being made, it is still challenging to evaluate the effect of immunotherapies on this and other relatively rare, but aggressive, subtypes, including uveal melanoma, since a low number of these patients have been included thus far in prospective clinical trials that have evaluated immunotherapies in cancer patients [14, 15]. Indeed, in phase III clinical trials that have studied nivolumab monotherapy (CheckMate 066, 037, 067), mucosal melanoma patients made up approximately 10 % of the trials’ population [16].

Here we report a case of a treatment-naive patient with mucosal melanoma with high baseline LDH treated with nivolumab as part of the phase III, randomized, double-blind CheckMate 066 study. The study evaluated nivolumab (n = 210) or dacarbazine (n = 208) in patients with treatment-naive, BRAF wild-type advanced melanoma [2]. Unlike many previous studies evaluating treatment for advanced melanoma, CheckMate 066 did allow inclusion of patients with the mucosal subtype. The study met its primary endpoint of improved OS with nivolumab compared with dacarbazine.

Patient case

Presentation

A 66-year-old woman presented with several episodes of recurrent epistaxis over 5 months. Magnetic resonance imaging of the face showed a nodular lesion, approximately 1.5 cm, in the right nasal cavity with bone erosion. A biopsy was performed with a histological finding of a neuroectodermal tumor that was considered to be most likely malignant melanoma. On excision of the lesion, findings confirmed the presence of a primary mucosal malignant melanoma, with neoplastic infiltration of the perpendicular plate of ethmoid. A whole-body computed tomography scan was performed, revealing multiple secondary lesions: evidence of solid and infiltrating tissue borne on the right ethmoid, sphenoid sinuses, right maxillary sinus, and frontal sinus. Systemic dissemination included multiple pulmonary bilateral parenchymal nodules, pleural and hilar lymph nodes, peritoneal carcinomatosis, infiltration of the upper splenic pole, and secondary focal bilateral adrenal and liver nodules. A biopsy was performed on ischium bone metastases, and the formal diagnosis was metastatic BRAF wild-type melanoma. The sample was not evaluable for PD-L1, as the bone biopsy sample underwent decalcification, and this process has not been validated for PD-L1 stains with the DAKO PharmDX kit. The patient’s baseline relative lymphocyte count was 25.6 % (2.8 × 103 µL), and her relative eosinophil count was 0.9 % (0.1 × 103 µL).

Treatment and efficacy

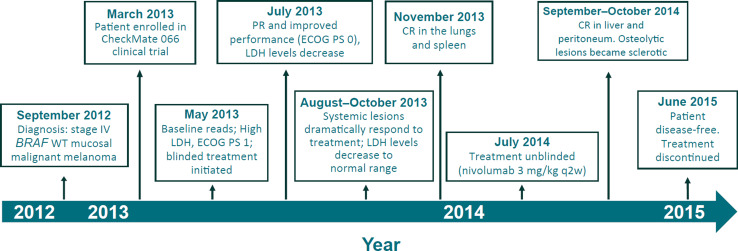

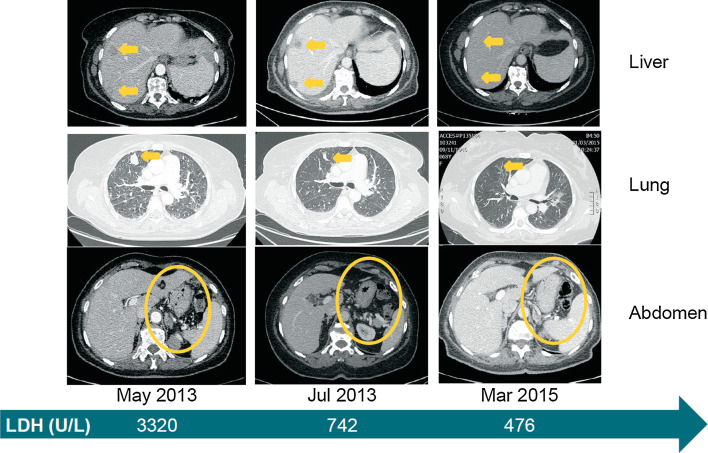

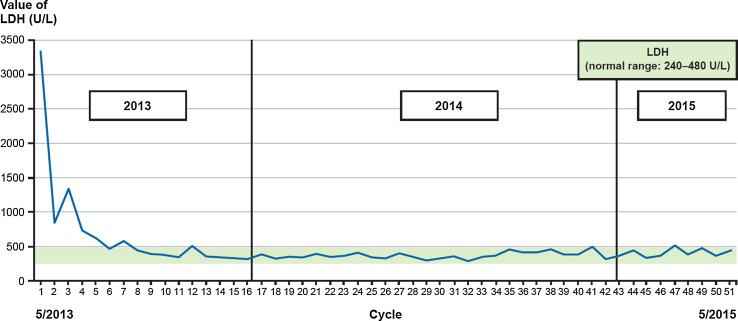

The patient was enrolled in the CheckMate 066 clinical trial in March 2013 and initiated first-line treatment in May 2013, 8 months after her initial diagnosis (Fig. 1). At baseline, her Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status was 1, and LDH levels were particularly high, with a maximum value of 3320 U/L (7 × ULN). At the first assessment in July 2013, a partial response (PR) was documented, which was also associated with a marked improvement in performance status (ECOG 0). LDH levels were markedly reduced to 742 U/L (Fig. 2). A month later, adrenal lesions were no longer detectable, and LDH levels continued to decrease and were maintained within normal limit throughout treatment (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Presentation and efficacy milestones. CR complete response, ECOG PS Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, PR partial response, WT wild type

Fig. 2.

Systemic clinical response to nivolumab treatment. Computed tomography images from baseline (May 2013), 2 months into treatment and approximately 2 years later. Yellow arrows or circles indicate metastatic foci and their complete disappearance by March 2015. The green arrow depicts the level of LDH at the selected time points. LDH lactate dehydrogenase

Fig. 3.

LDH levels over trial period. LDH levels as measured per each treatment cycle throughout the trial period. The green line represents normal levels range for LDH. Normal levels were reached at approximately cycle 6 and remained normal for the rest of follow-up. LDH lactate dehydrogenase

In October 2013, hilar lymph nodes were no longer appreciable. Pneumatization of the paranasal cavities was largely reintegrated with mild mucosal residue thickening. A scan performed in November 2013 demonstrated complete response in the lungs, and no appreciable secondary lesion of the spleen. Unblinding of the study treatment in July 2014 revealed the patient was treated with nivolumab (per protocol: 3 mg/kg intravenously every 2 weeks). In September 2014, a complete response in the liver was documented. Eight weeks later (late October 2014), the patient experienced complete remission of peritoneal metastasis, and osteolytic lesions became sclerotic, a sign of an effective response to the therapy.

Safety

Throughout treatment, the patient experienced mild immune-related adverse events (irAEs) of the skin and hepatic systems. Grade 1 rash occurred on several occasions, was treated with oral prednisone (25 mg bid), and typically resolved within several weeks. Grade 2, whole-body vitiligo, which remains ongoing, and grade 1 alopecia, which eventually resolved after 13 months, were untreated. The patient also experienced an increase in liver enzymes including alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and was diagnosed with grade 2 cholecystitis. The condition was treated with Fluimucil (acetylcysteine) and ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) and resolved, as determined by normalization on blood examinations, after 4 weeks. No treatment interruptions were required (Table 1).

Table 1.

Adverse events experienced by the patient during treatment

| AE | Grade | Onset | Resolution | Time to resolution | Treatment/management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitiligo (trunk and face) | 2 | 9/2013 | Ongoing | N/A | No treatment |

| Vitiligo (total body) | 10/2013 | Ongoing | N/A | No treatment | |

| Alopecia | 1 | 10/2013 | 11/2013 | 1 month | No treatment |

| Increased liver enzymes, cholecystitis | 2 | 6/2014 | 7/2014 | 4 weeks | Fluimucil (acetylcysteine) 600 mg and UDCA 450 mg bid × 12 days |

| Rash | 1 | 9/2014 | 9/2014 | 5 days | Prednisone 25 mg × 5 days |

| 1 | 1/2015 | 1/2015 | 10 days | Prednisone 25 mg bid × 5 days, then 25 mg × 5 days | |

| 1 | 2/2015 | 3/2015 | 1.5 months | Prednisone 25 mg × 15 days |

N/A not applicable, UDCA ursodeoxycholic acid

Follow-up

Two years after treatment initiation, the patient is disease-free and in good general clinical condition, per planned protocol tumor assessments. On June 2015, after 2 years of nivolumab treatment, we considered her to have reached the maximum clinical benefit. Treatment was stopped, and patient follow-up continued thereafter (Figs. 1, 2).

Discussion

In this case report, the patient achieved a rapid and durable complete response to nivolumab monotherapy, which was concomitant with a marked reduction in baseline LDH levels. The patient’s complete response was remarkable given that she had widely metastatic disease involving multiple organs, arising from primary mucosal melanoma, and elevated LDH levels at baseline—all considered poor prognosis markers in melanoma. Interestingly, although she had high baseline LDH, her decreased LDH level served as an excellent surrogate marker of response to therapy from very early on in treatment, an observation supported by Diem et al. [10] who showed that LDH levels during treatment can predict outcome. Regarding laboratory values, the patient’s relative lymphocyte count was consistent with that predicted for a favorable OS, but her relative eosinophil count was not [11].

The patient experienced low-grade irAEs across several organ classes that were consistent with the safety profile observed in CheckMate 066 and managed according to established guidelines without treatment interruption. In clinical studies, the majority of irAEs resolved following the use of these guidelines; however, it is important to identify and treat patients as early as possible, and closely follow up [2, 3].

In CheckMate 066, 10 % of patients had baseline LDH greater than twice the ULN, and 61 % had M1c stage of disease [2]. Despite the relatively high percentage of patients with harder-to-treat disease characteristics, increased clinical benefit overall, including significantly higher 2-year OS rates compared with dacarbazine (57.7 vs 26.7 %, respectively, p < 0.001), was observed with nivolumab [17]. Although subgroup analyses were performed, including patients with LDH ≤ULN and >ULN, no formal statistical comparisons were made between subgroups or within treatments. Therefore, conclusions cannot be drawn about the differences in efficacy between patients with normal and elevated LDH within this trial. In fact, to date, the predictive value of LDH has been evaluated in only one trial with an anti-PD-1 agent (pembrolizumab in KEYNOTE-002), but no differences were observed between these two groups [18]. Conversely, several expanded access program (EAP) studies with ipilimumab have demonstrated lower disease control rates and decreased survival in patients stratified according to normal baseline LDH compared with those with LDH twice the ULN [13, 19].

Despite the association between high baseline LDH and poor outcome, recent data, supported by this case report, show promise for immunotherapy compared with other treatments in this hard-to-treat patient population: Consistent survival benefit in patients with elevated LDH was previously reported for those who received ipilimumab compared with gp100, despite elevated LDH levels in more than 36 % of patients [9]. A similar clinical benefit with ipilimumab was also observed in the Italian EAP, where 38 % of the population had elevated LDH [19]. Moreover, results were found in a recent retrospective analysis that reported PR (32 %) or stable disease (9 %) in patients with elevated baseline LDH treated with nivolumab or pembrolizumab [10].

Mucosal melanoma is a rare and particularly aggressive subtype, associated with a poor 5-year survival compared with cutaneous and ocular melanomas [21, 22]. Much of the available data describing the efficacy of immunotherapy in mucosal melanoma have come from retrospective analyses or case studies [9, 13, 20, 23–25]. In general, although the efficacy of immunotherapy is lower than that observed in cutaneous melanoma, there is a demonstrated activity with these agents. Indeed, in a recent pooled analysis that represents the largest report of efficacy and safety outcomes for patients of mucosal melanoma to date, patients treated with nivolumab alone (n = 86) or in combination with ipilimumab (n = 35) showed consistent improvement in outcome versus ipilimumab monotherapy [16]. The safety profile of both the combination and nivolumab monotherapy observed in this pooled analysis was similar between mucosal and cutaneous subtypes. In agreement with those promising results, our case report represents supportive evidence on the efficacy and safety of nivolumab in mucosal melanoma for which effective therapies are needed.

Although the patient could not be evaluated for PD-L1, based on clinical trial experience, responses in nivolumab alone and in combination with ipilimumab occur regardless of PD-L1 status [2, 4, 5]. These data have suggested that PD-L1 expression may not be useful as a predictive biomarker and should not play a role in selecting patients for therapy [26].

With several efficacious treatments available, determining the optimal use of these agents is essential. Patients may benefit from the identification and prospective testing of predictive markers of response. The case presented here highlights the potential effectiveness of nivolumab monotherapy in a patient with primary mucosal, metastatic melanoma, with high LDH levels at baseline, all of which typically have portended a poor prognosis. The response to nivolumab in this case is promising and warrants additional investigation of nivolumab in patients with similar characteristics.

Acknowledgments

Professional medical writing assistance was provided by Dan Rigotti, PhD, at StemScientific, an Ashfield Company, and was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Funding

The parent clinical trial (CheckMate 066) was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Abbreviations

- ALP

Alkaline phosphatase

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- CR

Complete response

- EAP

Expanded access program

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- GGT

Gamma-glutamyltransferase

- irAEs

Immune-related adverse events

- N/A

Not applicable

- PR

Partial response

- PS

Performance status

- UDCA

Ursodeoxycholic acid

- ULN

Upper limit of normal

- WT

Wild type

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Paolo A. Ascierto has/had a consultant/advisory role for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche-Genentech, MSD, Novartis, Ventana, Amgen, Array. He received also research funds from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche-Genentech, Ventana. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Forsea AM, Del Marmol V, de Vries E, Bailey EE, Geller AC. Melanoma incidence and mortality in Europe: new estimates, persistent disparities. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(5):1124–1130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):320–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber JS, D’Angelo SP, Minor D, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(4):375–384. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Postow MA, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2006–2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ascierto PA, Capone M, Urba WJ, Bifulco CB, Botti G, Lugli A, et al. The additional facet of immunoscore: immunoprofiling as a possible predictive tool for cancer treatment. J Transl Med. 2013;11:54. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD et al (2015) Efficacy and safety in key patient subgroups of nivolumab alone or combined with ipilimumab versus ipilimumab alone in treatment-naïve patients with advanced melanoma (CheckMate 067). European Society for Medical Oncology 2015 Congress. Presented September 28, 2015

- 8.Mahoney KM, Freeman GJ, McDermott DF. The next immune-checkpoint inhibitors: PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in melanoma. Clin Ther. 2015;37(4):764–782. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diem S, Kasenda B, Spain L, Martin-Liberal J, Marconcini R, Gore M, et al. Serum lactate dehydrogenase as an early marker for outcome in patients treated with anti-PD-1 therapy in metastatic melanoma. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(3):256–261. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weide B, Martens A, Hassel JC, Berking C, Postow MA, Bisschop K, et al. Baseline biomarkers for outcome of melanoma patients treated with pembrolizumab. Clin Cancer Res. 2016 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelderman S, Heemskerk B, van Tinteren H, van den Brom RR, Hospers GA, van den Eertwegh AJ, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase as a selection criterion for ipilimumab treatment in metastatic melanoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63(5):449–458. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1528-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Del Vecchio M, Di Guardo L, Ascierto PA, Grimaldi AM, Sileni VC, Pigozzo J, et al. Efficacy and safety of ipilimumab 3 mg/kg in patients with pretreated, metastatic, mucosal melanoma. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(1):121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Del Prete V, Chaloupka K, Holzmann D, Fink D, Levesque M, Dummer R, Goldinger SM. Noncutaneous melanomas: a single-center analysis. Dermatology. 2016;232(1):22–29. doi: 10.1159/000441444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zimmer L, Eigentler TK, Kiecker F, Simon J, Utikal J, Mohr P, et al. Open-label, multicenter, single-arm phase II DeCOG-study of ipilimumab in pretreated patients with different subtypes of metastatic melanoma. J Transl Med. 2015;13:351. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0716-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larkin J, D’Angelo SP, Sosman JA, Lebbe C, Brady B, Neyens B et al (2015) Efficacy and safety of nivolumab alone or in combination with ipilimumab in the treatment of advanced mucosal melanoma. Society for Melanoma Research 2015 Congress. Presented November 20, 2015

- 17.Atkinson V, Ascierto PA, Long GV, Brady B, Dutriaux C, Maio M et al (2015) Two-year survival and safety update in patients with treatment-naïve advanced melanoma (MEL) receiving nivolumab or dacarbazine in CheckMate 066. Presented at Society for Melanoma Research (SMR) 2015 International Congress, November 18–21, San Francisco, California, USA

- 18.Ribas A, Puzanov I, Dummer R, Schadendorf D, Hamid O, Robert C, et al. Pembrolizumab versus investigator-choice chemotherapy for ipilimumab-refractory melanoma (KEYNOTE-002): a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(8):908–918. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelderman S, Heemskerk B, van Tinteren H, van den Brom RR, Hospers GA, van den Eertwegh AJ, Kapiteijn EW, de Groot JW, Soetekouw P, Jansen RL, Fiets E, Furness AJ, Renn A, Krzystanek M, Szallasi Z, Lorigan P, Gore ME, Schumacher TN, Haanen JB, Larkin JM, Blank CU. Lactate dehydrogenase as a selection criterion for ipilimumab treatment in metastatic melanoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63(5):449–458. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1528-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ascierto PA, Simeone E, Sileni VC, Pigozzo J, Maio M, Altomonte M, et al. Clinical experience with ipilimumab 3 mg/kg: real-world efficacy and safety data from an expanded access programme cohort. J Transl Med. 2014;12:116. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-12-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mihajlovic M, Vlajkovic S, Jovanovic P, Stefanovic V. Primary mucosal melanomas: a comprehensive review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5:739–753. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X, Si L, Guo J. Treatment algorithm of metastatic mucosal melanoma. Chin Clin Oncol. 2014;3:38. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3865.2014.08.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alexander M, Mellor JD, McArthur G, Kee D. Ipilimumab in pretreated patients with unresectable or metastatic cutaneous, uveal and mucosal melanoma. Med J Aust. 2014;201:49–53. doi: 10.5694/mja13.10448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Postow MA, Luke JJ, Bluth MJ, et al. Ipilimumab for patients with advanced mucosal melanoma. Oncologist. 2013;18:726–732. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Min L, Hodi FS. Anti-PD1 following ipilimumab for mucosal melanoma: durable tumor response associated with severe hypothyroidism and rhabdomyolysis. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:15–18. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Festino L, Botti G, Lorigan P, et al. Cancer treatment with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 agents: is PD-L1 expression a biomarker for patient selection? Drugs. 2016;76:925–945. doi: 10.1007/s40265-016-0588-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]