Abstract

Adoptive infusion of natural killer (NK) cells is being increasingly explored as a therapy in patients with cancer, although clinical responses are thus far limited to patients with hematological malignancies. Inadequate homing of infused NK cells to the tumor site represents a key factor that may explain the poor anti-tumor effect of NK cell therapy against solid tumors. One of the major players in the regulation of lymphocyte chemotaxis is the chemokine receptor chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 3 (CXCR3) which is expressed on activated NK cells and induces NK cell migration toward gradients of the chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL9, 10 and 11). Here, we show that ex vivo expansion of human NK cells results in a tenfold increased expression of the CXCR3 receptor compared with resting NK cells (p = 0.04). Consequently, these NK cells displayed an improved migratory capacity toward solid tumors, which was dependent on tumor-derived CXCL10. In xenograft models, adoptively transferred NK cells showed increased migration toward CXCL10-transfected melanoma tumors compared with CXCL10-negative wild-type tumors, resulting in significantly reduced tumor burden and increased survival (median survival 41 vs. 32 days, p = 0.03). Furthermore, administration of interferon-gamma locally in the tumor stimulated the production of CXCL10 in subcutaneous melanoma tumors resulting in increased infiltration of adoptively transferred CXCR3-positive expanded NK cells. Our findings demonstrate the importance of CXCL10-induced chemoattraction in the anti-tumor response of adoptively transferred expanded NK cells against solid melanoma tumors.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-014-1629-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Adoptive cell therapy, Natural killer cells, Migration, CXCL10, CXCR3

Introduction

In recent years, adoptive infusion of natural killer (NK) cells has gained an increased attention as immunotherapy against cancer. Efforts to improve the use of NK cells against cancer include augmentation of cytotoxicity, resistance to suppression as well as maintenance of NK cell persistence in vivo. [1–3]. One of the key issues to be resolved is to whether NK cells need to be expanded or short-term activated with growth factors prior to infusion. Activation of NK cells with cytokines has been proposed to increase the probability of achieving longer in vivo persistence of transferred NK cells, while the total numbers of cells for infusion remain relatively small. In contrast, by expanding the NK cells with irradiated feeder cells such as peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), Epstein–Barr virus–lymphoblastoid cell line (EBV-LCL) or gene-modified K562 cells, a higher ex vivo proliferation rate as well as increased cytotoxic potential of the NK cells can be achieved at the expense of potentially over-activating and exhausting the NK cells before infusion [4–6]. Several reports have demonstrated that intratumoral infiltration of NK cells correlates with a good prognosis in a variety of cancers [7–10]. Moreover, alloreactive donor NK cells can mediate anti-tumoral effects in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) that undergo haploidentical hematopoietic cell transplantation [11]. However, the clinical success of adoptive NK cell transfer is limited for patients with solid tumors compared with patients with leukemia and other blood-borne cancers [12–15]. The clinical responses observed with NK cell therapy in patients with AML cannot be explained by high expression of activating NK cell ligands or low expression of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I. On the contrary, the expression level of UL16-binding proteins (ULBPs) as well as ligands for the natural cytotoxicity receptors (NCRs) is low on leukemic blasts [16] and loss of HLA class I is less frequent in AML than in solid tumors such as melanoma [17]. Instead, a potential explanation for why patients with AML but not solid tumors respond to adoptive NK cell infusion may be due to insufficient homing to solid tumors. In rats bearing liver or lung metastases, it has been described that adoptively transferred NK cells in combination with interleukin (IL)-2 infusions lead to an accumulation of NK cells at the tumor sites [18, 19]. In humans, trafficking studies of infused NK cells have not been performed. Yet, infiltration of lymphocytes in tumors is low as illustrated by Fisher et al. [20] showing that only a minority (0.016 % of infused cells) of adoptively transferred 111In-labeled lymphocytes were present in tumors of melanoma patients without prior preconditioning.

Chemokines are classified as inflammatory and constitutive cytokines that govern the migratory pattern of leukocytes. In peripheral blood non-activated NK cells, the expression of constitutive chemokine receptors such as C-X-C motif receptor (CXCR)-4 and C-C chemokine receptor (CCR)-7 allows them to home to lymph nodes (LNs), while the receptors CCR4, CCR6 and CXCR6 expressed on CD56bright rather than on CD56dim NK cells facilitate their migration to the skin. However, under inflammatory conditions as well as in cancer, the expression of inflammatory chemokine receptors such as CCR1, CCR2, CXCR2 and CXCR3 facilitates the migration toward gradients of inflammatory chemokines released from inflamed tissues or from the tumor [21–23]. Efforts have been made to augment the migratory capacity of lymphocytes to various tumor sites by altering their chemokine receptor expression [24, 25]. Recent reports have shown that high expression of the interferon (IFN)-γ-inducible chemokines C-X-C motif ligand (CXCL)-9 (monokine induced by gamma interferon, MIG) and CXCL10 (IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10, IP-10) at the tumor site is a predictive factor for both intratumoral infiltration of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) as well as a favorable prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer [26–28]. These chemokines as well as CXCL11 (interferon-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant, I-TAC) attract cells expressing the CXCR3 chemokine receptor [29], and secretion of CXCR3 ligands is associated with recruitment and infiltration of CXCR3-positive CTLs in several malignancies including renal cell carcinoma and melanoma [30–33].

In the present study, we show that ex vivo expansion significantly upregulates the expression of CXCR3 on NK cells resulting in increased migratory capacity toward CXCL10-producing tumor cells in vitro. Furthermore, increased intratumoral infiltration of adoptively infused human expanded NK cells resulted in reduced tumor burden in mice bearing CXCL10-producing tumors compared with mice bearing CXCL10-negative tumors. Taken together, these data define CXCL10 as an important chemokine that attracts ex vivo expanded adoptively infused NK cells in melanoma bearing hosts.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

The renal cell carcinoma (RCC) cell lines, JOHW, ORT, SNY, COL, MAR and BEN, were established from surgically resected tumor specimens. The melanoma cell lines 526MEL, 624 and STEW were kindly provided by Dr. M. Dudley (Surgery Branch, NCI, NIH). The anaplastic thyroid cancer cell lines LUTC-1 and LUTC-10 were kindly provided by Dr. J. Wennerberg (Lund University, Sweden). The melanoma cell lines EST112 and EST149 were obtained from the ESTDAB repository (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ipd/estdab/directory.html). All cell lines were maintained in RPMI1640 or DMEM (Cellgro, Herndon, VA), supplemented with 10 % fetal calf serum (FCS) (HyClone, Logan, UT). Verification of the cell line EST112 was performed using the AuthentiFiler Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplification kit (Life technologies, Stockholm, Sweden).

The melanoma cell lines 526MEL and EST112 were transduced with luciferase by lentiviral transduction at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 in presence of 8 μg/ml polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Transduced tumor cells were cloned by limiting dilution, and single-cell clones were screened for the expression of luciferase in presence of 150 µg/ml luciferin by Xenogen IVIS Spectrum camera (Caliper life sciences, Hopkinton, MA). Luciferase-transduced 526MEL cells were subsequently transduced with either CXCL10 or mock by lentiviral transduction at an MOI of 10 in presence of 8 μg/ml polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich). Lentivirus-transduced 526MEL cells produced 70-fold higher levels of CXCL10 compared with mock-transduced 526MEL cells (3,802 ± 36 vs. 55 ± 36 pg/ml).

Isolation and expansion of NK cells

NK cells were isolated from PBMCs by negative selection using immunomagnetic beads (NK cell isolation kit, Miltenyi, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). EBV-LCLs were irradiated (100 Gy) and used as feeder cells at a 1:20 cell ratio (NK:EBV-LCL) in X-VIVO 20 media (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), supplemented with 10 % heat-inactivated human AB serum (Karolinska Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden) and 1,000 U/ml interleukin-2 (IL-2) (Novartis Pharma, Nurnberg, Germany). IL-2 (500 U/ml) was added to cultures on days 5, 8 and 11 after isolation, and the cytotoxic activity of NK cells was assessed on day 11–14 by chromium release assay.

Chromium release assay

Target cell lines were labeled with 45 µCi of 51Cr (PerkinElmer, Groningen, The Netherlands) for 1 h at 37 °C. NK cells were seeded in triplicates in a 96-well plate together with 5,000–10,000 51Cr-labeled target cells at a 1:1 effector-to-target (E:T) ratio. After 18-h incubation at 37 °C in 5 % CO2, supernatant was harvested from each well, transferred to Luma plates (PerkinElmer) and analyzed using a Microbeta scintillation counter (Wallac, PerkinElmer). Where indicated, tumor cells were treated with IFN-γ (500–1,000 U/ml) and/or doxorubicin (DOX) (200 ng/ml) 24 h prior analysis in cytotoxicity assays.

Chemokine production assays

The production of CXCL10 by tumor cell lines was analyzed by ELISA (RnD systems, Abingdon, UK) or multiplex chemokine protein array (RayBiotech, Norcross, GA) according to the manufacturers’ instructions before and after treatment with IFN-γ (24 h, 500–1,000 U/ml).

Flow cytometry

Untreated and IFN-γ-treated (24 h, 500–1,000 U/ml) tumor cells were stained with anti-human HLA-ABC (Beckman Coulter, San Diego, CA). NK cell phenotype was analyzed by gating on viable 7-AAD-negative (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) CD3−CD56+ cells and the expression of surface ligands using antibodies against CD16, CXCR2, CXCR3, CCR2, CCR3, CCR5, leukocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1) and very late antigen-4 (VLA-4) (BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Stained cells were acquired on an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and all flow cytometry data were analyzed using the FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Transwell assay

Tumor cells were cultured in 24-well plates to 80 % confluency and then treated with IFN-γ (500–1,000 U/ml) and/or doxorubicin (200 ng/ml) for 24 h. Thereafter, tumor supernatant (600 µl) was harvested and transferred to 24-well plates. Alternatively, serum-free media containing recombinant CXCL9, 10 or 11 (Peprotech, London, UK) was added to 24-well plates (600 µl/well) at 0.1–10 nM. Transwell inserts with polycarbonate membranes (5 or 8 µm pore size, Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA) were placed in the wells containing tumor cells, tumor cell supernatant or recombinant chemokines. NK cells (2.5 × 105) were added in 100 µl medium to the inserts and incubated for 2–6 h at 37 °C. Following incubation, the inserts were washed and migrated cells were quantified using the CytoSelect 24-well cell migration assay (Cell Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Alternatively, inserts were transferred to a new plate and membranes were washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 min and stained with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Histolab Products AB, Gothenburg, Sweden). Membranes were washed in PBS, and images were acquired using an Olympus CKX41 microscope and analyzed using the CellsenseEntry software (Olympus, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan). Membranes were blinded, and the number of stained cells was enumerated using the Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Xenograft models

All experiments were approved by the NHLBI NIH animal care and use committee (Protocol H-0111-R1) and the Ethical review board at Karolinska Institutet (Ethical approval # N42/10 and # 603/12). 526MEL cells were injected subcutaneously (S.C) (1–2 × 106/mouse) into C.B-17 SCID/beige mice (Taconic, Rockville, MD). For migration experiments, CXCL10-transduced and mock-transduced tumor cells were injected (S.C, 1–2 × 106/mouse) in each flank of the same mouse. For tumor progression and survival analysis, CXCL10-transduced and mock-transduced 526 MEL cells were injected (S.C, 1–2 × 106/mouse) in individual mice. Five days following tumor inoculation, expanded human NK cells were injected at 1–15 × 106/mouse intravenously (I.V). To maintain NK cell longevity in vivo, all mice received an intraperitoneal (I.P) injection of 100,000 U IL-2 on the day of NK cell infusions and twice daily for 5 days. Mice were imaged using bioluminescence imaging (BLI) every three to 5 days following injection with NK cells.

In a second model, NOD/SCID/Gamma−/− mice (bred and maintained at the Microbiology and Tumor Biology Center, Karolinska Institutet) were injected S.C with 5 × 105 luciferase-transduced EST112 melanoma cells in the left flank. Six days after tumor inoculation, when tumors were palpable, IFN-γ was administered peritumorally (P.T) with 25 μl recombinant human IFN-γ (0.1 mg/kg) followed by I.V injections of expanded human NK cells (3–5 × 106 cells/mouse). All mice were pretreated with low-dose doxorubicin (I.V, 1 mg/kg) 24 h prior to NK cell injection to sensitize the tumors to NK cell-mediated killing. Three treatment cycles were performed weekly for each experiment. Mice not injected with NK cells received I.V injections of 100 µl PBS.

For in vivo fluorescence imaging, NK cells were labeled for 20–30 min with 3.5 µg/ml of DiR near infrared dye, [1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindotricarbocyanine iodide (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA)] prior to injection. The fluorescent signal was acquired with a 750-nm emission filter every 24 h up to 5 days after infusion. For BLI imaging of inoculated tumor cells, mice were injected I.P with 2 mg/mouse of D-luciferin salt (Caliper Life Sciences) and imaged every 6–24 h using the IVIS Xenogen system (Caliper Life Sciences).

Statistics

Student’s t test or log-rank test was used to calculate statistically significant differences between groups. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Ex vivo expansion increases the expression of CXCR3 and improves migratory capacity of human NK cells toward CXCL9-11 in vitro

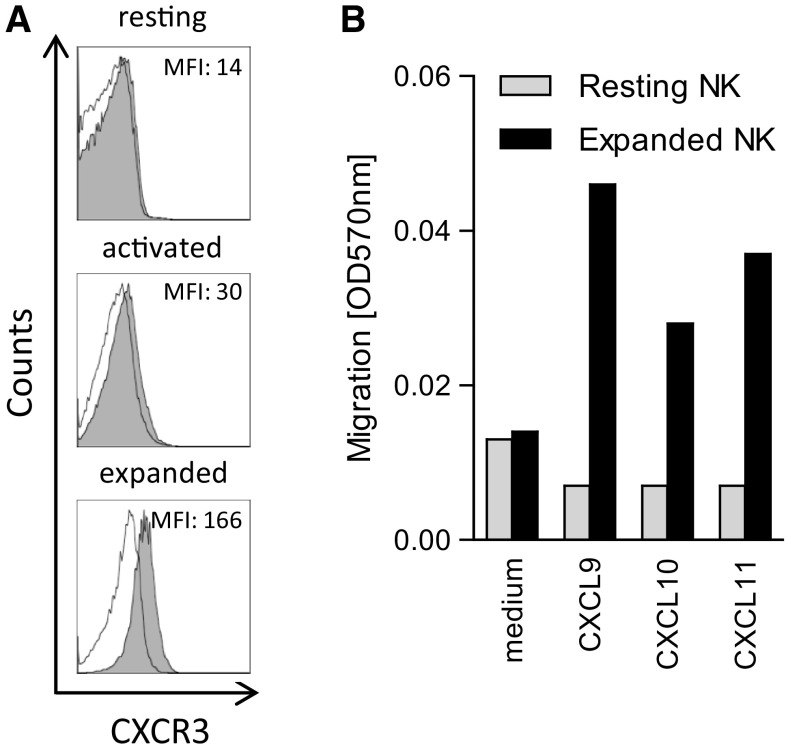

We sought to elucidate whether ex vivo expansion of human NK cells with irradiated LCL feeder cells would alter the phenotype of NK cells with regards to CXCR3 expression. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CXCR3 expression increased on average from 22.3 ± 13.11 to 218 ± 77.5 (n = 3, p = 0.04) in 11-day expanded NK cells compared with resting NK cells, corresponding to an average tenfold increase in CXCR3 (Fig. 1a). Although the expression of CXCR3 was upregulated on overnight IL-2-activated NK cells, the MFI of CXCR3 expression was increased on average 1.82 ± 0.39-fold (n = 3, p = 0.34) compared with resting NK cells. A similar induction of CXCR3 expression was observed on NK cells expanded in the presence of IL-15 compared with NK cells expanded in the presence of IL-2 (data not shown). No significant change in expression of other chemokine receptors or adhesion molecules including LFA-1, VLA-4, CCR5, CCR2 and CCR3 was observed in expanded NK cells (data not shown). Along with the increased expression of CXCR3, expanded NK cells displayed a threefold to sixfold increased migratory capacity toward the recombinant chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXCL11 in vitro compared with resting NK cells (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

a Surface expression of CXCR3 on human CD3−CD56+ NK cells isolated from healthy peripheral blood, either directly after isolation (resting), after 24-h activation with IL-2 (activated) or after 11 days of expansion (expanded). Gray histogram represents NK cells stained with PE-conjugated anti-CXCR3 antibody. Empty histograms represent NK cells stained with IgG1-PE isotype control antibody. MFI of CXCR3 (isotype ctrl MFI) is indicated in histogram captions. One of the three representative experiments is shown. b Transwell migration assay of resting and expanded NK cells toward serum-free medium containing CXCR3 ligands, 8-µm pore size filter, 6-h incubation. Recombinant CXCL9, 10 and 11 were added to separate wells in a 24-well plate at 1 nM. One of the two representative experiments is shown

IFN-γ triggers tumor cells to produce CXCL10 which attracts expanded NK cells in vitro

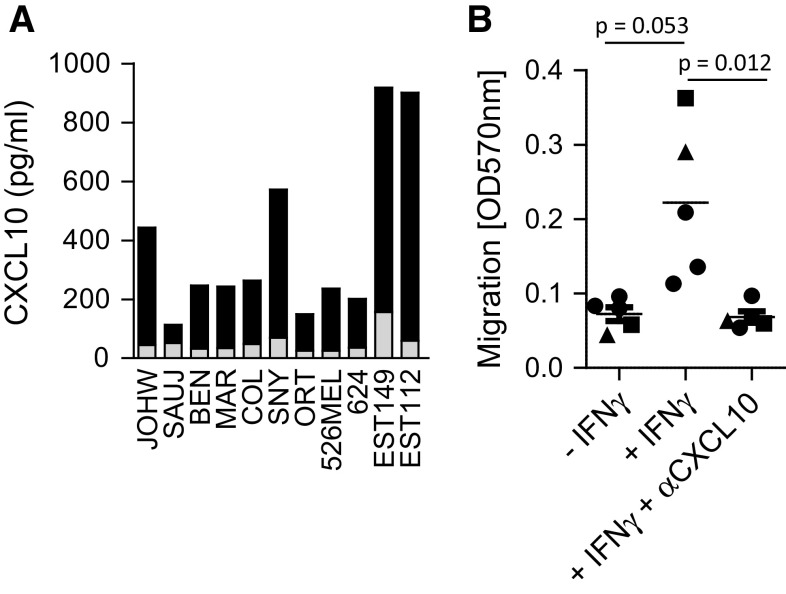

To analyze the ability of tumor cells to attract human expanded NK cells, tumor cell lines of various origins were assessed for production of CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXCL11 before and after stimulation with IFN-γ. CXCL10 was produced at low levels in all untreated tumors (range 25–156 pg/ml, average concentration 53 ± 37 pg/ml), while a significant increase in CXCL10 production was observed in ten of eleven cell lines after stimulation with 1,000 U/ml IFN-γ for 24 h (63–841 pg/ml, average concentration 337 ± 260 pg/ml (p < 0.001, Fig. 2a). Similarly, stimulation of tumor cell lines with the combination of IFN-α and poly-inositol–cytidine (poly-I:C) increased their CXCL10 production, albeit to a lesser extent (data not shown). In contrast, no significant changes in the production of CXCL9 and 11 were observed after treatment with IFN-γ (data not shown). The augmented CXCL10 production after treatment with IFN-γ was sufficient to attract expanded NK cells in a transwell chemotaxis assay. Migration of expanded NK cells toward IFN-γ-treated tumor cells increased threefold compared with untreated tumor cells (p = 0.053). The migration of NK cells toward IFN-γ-treated tumor cells was significantly reduced in presence of neutralizing antibodies against CXCL10 compared with IFN-γ-treated tumor cells in the absence of neutralizing antibodies against CXCL10 (p = 0.012) (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

a Eleven different tumor cell lines (JOHW, SAUJ, BEN, MAR, COL, SNY, ORT, 526MEL, 624, EST149, EST112) were treated with 1,000 U/ml IFN-γ for 24 h and analyzed for production of CXCL10 by ELISA. The gray bar indicates base-line production of CXCL10, and black bars indicate CXCL10 production of each cell line after treatment with IFN-γ. The experiment was performed at least twice for cell lines; JOHW, 562MEL, SNY, 624 and EST112 and once for cell lines; SAUJ, BEN, MAR, COL, ORT and EST149. b Transwell assay measuring migration of expanded NK cells against 526MEL (circles), SNY (squares) and JOHW (triangles) cells plated at 100.000 cells/well in a 24 well plate and treated with 1,000 U/ml IFN-γ for 24 h (n = 5 experiments). Expanded NK cells were added at 0.5 × 106 per transwell insert and incubated for 6 h. ELISA was performed to confirm that CXCL10 production was blocked in presence of CXCL10-neutralizing antibodies (data not shown)

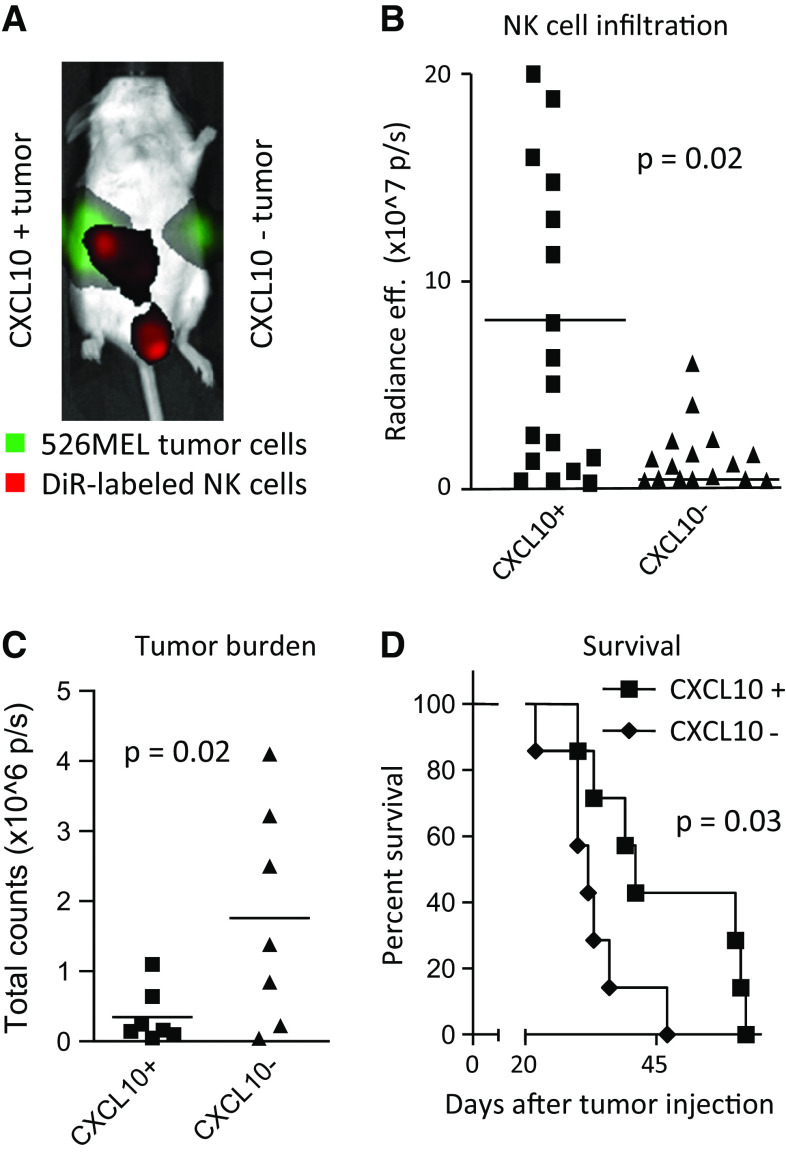

Increased intratumoral NK cell infiltration, reduced tumor burden and prolonged survival in mice bearing CXCL10-positive tumors treated with adoptively transferred ex vivo expanded human NK cells

Given the increased migratory capacity of expanded NK cells toward CXCL10 secreting tumors in vitro, we next investigated whether expanded CXCR3-positive NK cells would migrate toward CXCL10-positive tumors in vivo. C.B-17 SCID/beige mice were inoculated with both CXCL10-transduced and mock-transduced 526MEL cells S.C on separate flanks and thereafter I.V injected with DiR-labeled expanded human NK cells. Fluorescent imaging of mice and resected tumors showed a significantly increased infiltration of NK cells in the CXCL10-transduced tumors compared with mock-transduced tumors (p = 0.02, Fig. 3a, b). To assess the capacity of expanded NK cells to delay tumor progression and improve survival, individual C.B-17 SCID/beige mice were inoculated S.C. with either CXCL10-transduced or mock-transduced 526MEL tumors and infused with NK cells. Bioluminescence imaging of the mice revealed a significantly reduced tumor burden in mice bearing CXCL10-transduced 526MEL compared with mice bearing mock-transduced 526MEL (p = 0.02, Fig. 3c). Furthermore, following adoptive transfer of ex vivo expanded human NK cells, mice bearing CXCL10-transduced tumors had a significantly prolonged survival compared with mice bearing mock-transduced tumors (p = 0.03, Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

C.B-17 SCID/beige mice were inoculated S.C with 2 × 106 CXCL10-positive or CXCL10-negative 526MEL cells on both flanks in the same mouse (a, b) or in individual mice (c, d). a Example of in vivo imaging of a mouse inoculated with CXCL10-positive (right flank) or CXCL10-negative 526MEL tumor cells (left flank) after a single I.V. injection of DiR-labeled NK cells. b DiR fluorescence from resected CXCL10-positive and CXCL10-negative tumors (5 days following NK cell injection). Each symbol represents one individual mouse. c Tumor burden in mice bearing either CXCL10-positive or CXCL10-negative tumors measured by bioluminescent imaging (p/s = photons/second) 13 days after tumor inoculation. d Survival of mice bearing either CXCL10-positive or CXCL10-negative 526MEL tumors after NK cell injection (I.V, 1–15 × 106). NK cells injections started 5 days following tumor inoculation. A total of three infusions of NK cells were administered every 5 days. All mice also received IL-2 (I.P, 100.000 U)

Concomitant treatment with IFN-γ and doxorubicin results in decreased tumor burden through increased NK cell migration to tumors in vivo

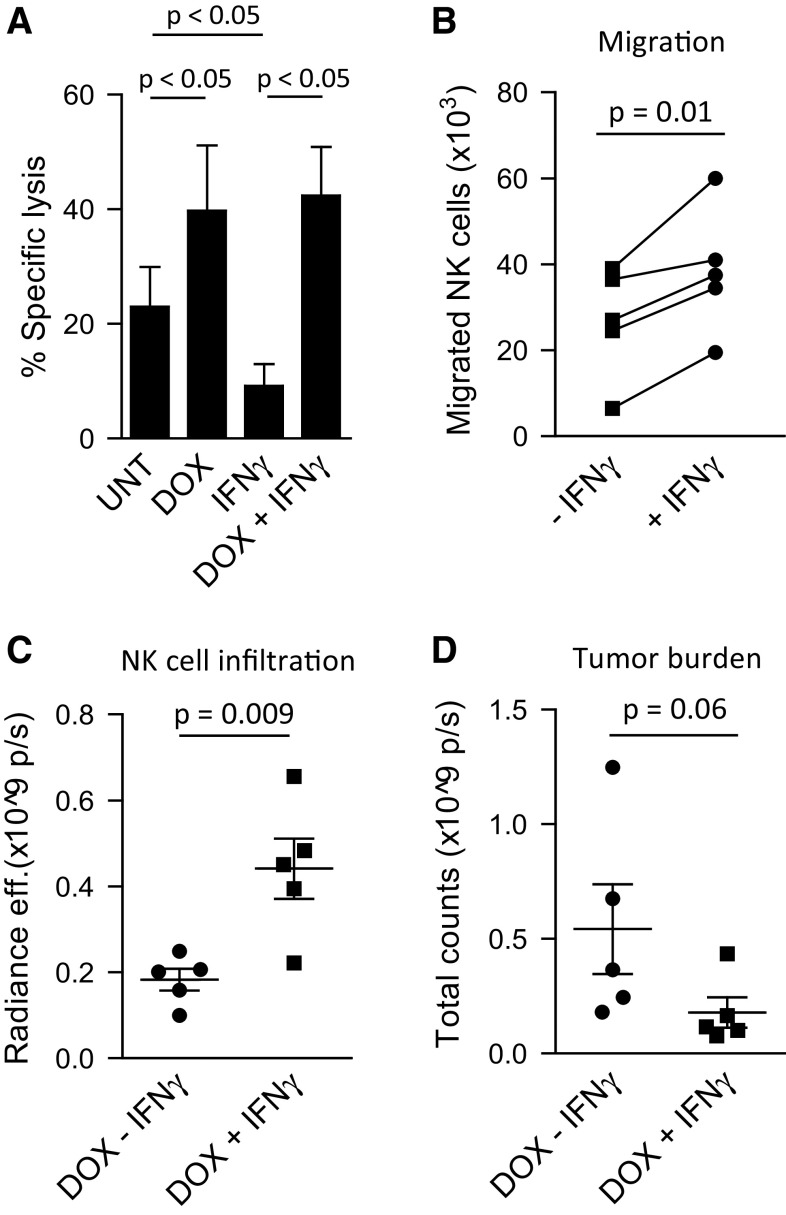

Since increased CXCL10 production by tumor cells in vitro was only observed after treatment with IFN-γ, we next investigated whether treatment with IFN-γ would augment the production of CXCL10 by tumors in vivo leading to a concomitant increased influx of adoptively transferred NK cells in tumor-bearing mice. Similar to the observations from our panel of cell lines, production of CXCL10 by EST112 melanoma tumors significantly increased after treatment with IFN-γ in vitro (p = 0.001, Supplementary Fig. 1A) and in vivo (Supplementary Fig. 1B). However, along with increased CXCL10 production, an upregulated surface expression of tumor HLA class I was observed (Supplementary Fig. 1C) resulting in decreased tumor sensitivity to NK cell lysis in vitro (Fig. 4a). To offset the resistance to NK cell-mediated killing induced by exposure to IFN-γ, tumor cells were pretreated with sub-apoptotic doses of doxorubicin to enhance their susceptibility to NK cell-mediated apoptosis. In vitro, when treated with doxorubicin prior to IFN-γ stimulation, the EST112 cells remained sensitive to NK cell killing at a similar level as after treatment with doxorubicin alone. Furthermore, expanded NK cells had a significantly improved ability to migrate toward supernatant derived from EST112 tumor cells treated with IFN-γ compared with supernatant from untreated EST112 tumor cells (p = 0.01, Fig. 4b). No difference in CXCL10 production was observed between tumors treated with IFN-γ alone or a combination of doxorubicin and IFN-γ (data not shown). In vivo, upon infusion of expanded NK cells, mice treated with doxorubicin and IFN-γ had a higher infiltration of NK cells compared with mice treated with IFN-γ alone (p = 0.009, Fig. 4c, Supplementary Fig. 1D). Although not significant, a decrease in the bioluminescent signal from tumors treated with IFN-γ at 12, 24 and 48 h after NK cell transfer was observed (p = 0.06, Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig. 1E). However, no significant difference in survival was observed between the NK cell-infused mice treated with doxorubicin and IFN-γ and doxorubicin alone (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

a NK cell-mediated lysis of untreated (UNT), doxorubicin-treated (DOX, 200 ng/ml), IFN-γ-treated (500 U/ml), or DOX + IFN-γ-treated EST112 melanoma cells. Effector:target ratio = 1:1, 18 h 51Cr-assay (n = 5). b Transwell migration assay of expanded NK cells toward supernatant from DOX-treated EST112 melanoma cells with or without 24 h treatment with 500 U/ml of IFN-γ. c Infiltration of DiR-labeled NK cells in EST112 tumors 24 h after the second round of NK cell infusions (I.V, 3–5 × 106 cells/mouse) measured by fluorescence radiance efficiency of the tumor area. d Bioluminescence imaging of subcutaneous tumors 48 h after the second round of NK cell infusions. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. p/s photons/second

Discussion

Here, we show that expansion of human NK cells results in upregulation of the CXCR3 receptor. Expanded NK cells migrated toward CXCL10-producing tumors in vitro and in vivo. Infusion of expanded NK cells in mice bearing CXCL10-producing tumors resulted in reduced tumor burden and improved survival. Despite evidence for efficacy in the treatment of hematological malignancies, adoptive NK cell therapy has yet to demonstrate beneficial clinical responses in patients with solid tumors. We recently developed a protocol where NK cells expand nearly 500-fold over 21 days [5]. In an ongoing clinical phase I trial, infusion of such expanded autologous NK cells proved safe at doses of 100 million NK cells/kg recipient body weight. Patients also received two daily administrations of 2 × 106 IU/m2 IL-2 for 7 days resulting in a peak in NK cell numbers 1 week after NK cell infusion. Adverse events were manageable, including fever, renal insufficiency and hypotension. Although preliminary results from this trial showed 7/14 patients with advanced solid tumors had stable disease or a minor response, partial and complete responses have yet to be observed [15]. One potential rate-limiting factor that can influence the clinical outcome of NK cell infusion in patients with solid tumors is the inability of NK cells to migrate to the tumor site.

In the present study, we show that ex vivo expansion of NK cells leads to changes in their chemokine receptor repertoire. Expression of CCR2, CCR3 and CCR5, which are implicated in lymphocyte migration toward solid tumors [34–36], did not change significantly by ex vivo expansion (data not shown). There are conflicting reports regarding the expression of CCR2 and CCR3 on human NK cells. The expression of CCR2 and CCR3 has been shown to increase after activation with IL-2 [37]. Though in this study, NK cells were cultured in presence of T cells, which can potentially explain the differences in results. Hodge et al. [38] showed that the expression of CCR2 was absent on human NK cells regardless of activation with IL-2, IL-12 or IL-18. We found that the expression of CXCR3 was significantly upregulated following ex vivo expansion of NK cells. CXCR3 has been shown to be preferentially expressed on CD16− NK cells [39], which was also observed in our study (data not shown). Modulation of CXCR3 expression on NK cells has been demonstrated in several studies where NK cells display increased expression of CXCR3 as well as improved migration toward CXCL10 and CXCL11 after treatment with IL-2 [40–42]. In contrast, Hodge et al. [38] observed a downregulation of CXCR3 expression on primary NK cells after short-term stimulation with IL-2. Furthermore, there are conflicting reports regarding the acquisition of CXCR3 upon ex vivo expansion of human NK cells. Lim et al. [43] recently showed that the expression of CXCR3 did not change, whereas Alici et al. [44] observed an increased expression of CXCR3 upon expansion. Although these authors used a similar expansion protocol, it appears that longer culture periods may be necessary to enhance the expression of CXCR3. In our study, there was a higher expression of CXCR3 on day-11 expanded NK cells compared with NK cells that were only expanded for 6 days. Evidently, depending on the duration of NK cell culture and cytokine exposure, the expression of chemokine receptors is highly variable. Hence, it is important to expand NK cells in contrast to a short-term activation in order to achieve sufficient CXCR3 expression and improved NK cell migration.

Along with an increased expression of CXCR3, we found that expanded NK cells were more responsive to chemoattraction by CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXCL11 compared with resting NK cells. Furthermore, migration of expanded NK cells toward melanoma was found to be dependent on tumor-derived CXCL10 in vivo, with infusion of expanded NK cells resulting in significantly prolonged survival in mice bearing CXCL10-positive melanoma tumors compared with mice bearing CXCL10-negative melanoma tumors. CXCR3 ligands can be secreted from a variety of different cell types including fibroblasts and endothelial cells, and they have been reported to be naturally expressed in ovarian carcinomas [45, 46]. Also, the presence of CXCL10 in the tumor microenvironment has been shown to correlate with recruitment of CD8+ T cells in colorectal carcinoma [26]. Yet, the role of CXCL10 in recruitment of human NK cells toward solid tumors has not been studied. In our experiments, the production of CXCL10 by a variety of tumor cell lines was observed after treatment with IFN-γ, with migration toward IFN-γ-treated tumor cells in vitro being dependent on CXCL10 production, as evidenced by the loss of this effect when CXCL10 was neutralized. Muthuswamy et al. [47] recently showed that the combination of IFN-α and poly-I:C induced CXCL10 expression in explanted tumor tissues from colon cancer patients, an effect that could be potentiated by indomethacin. Although to a lower extent compared with IFN-γ treatment, we found that exposure to IFN-α and poly-I:C resulted in an increased CXCL10 secretion in tumor cell lines. Thus, systemic treatment with IFN-α and poly-I:C could potentially be exploited.

Although IFN-γ treatment triggered the release of CXCL10 from tumor cells, a concomitant upregulation of HLA class I expression was observed resulting in increased resistance to NK cell lysis. We recently reported that doxorubicin can sensitize tumors to NK cell-mediated lysis despite high levels of HLA class I expression on tumor cells [48]. In the present study, we found that treatment of tumor-bearing mice with doxorubicin and IFN-γ significantly increased the intratumoral infiltration of adoptively infused NK cells (p < 0.01) and reduced tumor burden compared with mice receiving doxorubicin and NK cells (p = 0.061). Our results concur with and extend the findings of Wendel et al. that demonstrated that local IFN-γ treatment induces intratumoral infiltration of CXCR3-positive murine NK cells, which delays tumor progression in immunocompetent mice [49].

Although we did not investigate by what mechanism NK cells target the tumor cells in vivo, several adhesion molecules and ligands for activating and costimulatory receptors are involved in NK cell recognition of melanoma cells. These include the natural killer group 2 membrane D (NKG2D) ligands major histocompatibility complex class I-related chains A and B (MICA/B), the DNAX accessory molecule-1 (DNAM-1) ligands Nectin-2 and poliovirus receptor (PVR) [50]. Also, melanoma tumors can be killed by NK cells expressing the natural cytotoxicity receptors (NCRs) NKp30, NKp44 and NKp46 [51]. In addition, melanoma tumors can be targeted through the triggering of the death receptors tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) and Fas [48, 52]. Conversely, melanoma tumors can upregulate the expression of several receptors and inhibitory factors including programmed death (ligand)-1 (PD-L1) and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO). Tolerogenic cytokines produced by melanoma cells, including interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, can further enhance the immunosuppressive environment in tumors. We recently showed that the inhibition of melanoma-derived prostaglandin-E2 (PGE2) blocks the induction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and recovers NK cell activity [53].

In the present study, infusion of expanded human NK cells resulted in significantly prolonged survival in the 526MEL model, but not in the IFN-γ treatment EST112 melanoma model. Several differences between these two models might explain this discrepancy. First, the ectopic expression of CXCL10 in transduced 526MEL allows for a sustained production of CXCL10, whereas the secretion of CXCL10 from EST112 cells was only transiently increased following IFN-γ treatment. In supernatant from EST112 cells treated with IFN-γ, the level of CXCL10 was reduced by 56 % (from 1,648 to 726 pg/ml) after 4 days of in vitro culture, while CXCL10 levels in supernatant from 526MEL cells remained constant (from 1,824 to 1,877 pg/ml) during the same incubation period. Second, EST112 and 526MEL tumors may differ in their sensitivity to NK cell lysis in vivo. In vitro, the EST112 cell line is more resistant to lysis than the 526 MEL cell line (data not shown).

In summary, we demonstrate that adoptive transfer of human CXCR3-positive expanded human NK cells results in decreased tumor burden and prolonged survival in mice bearing CXCL10-positive human melanoma tumors. These findings highlight the importance of the CXCR3/CXCL10 axis in directing the migration of human expanded NK cells toward solid tumors. Efforts to prime the tumor microenvironment to secrete CXCL10 to attract CXCR3 are warranted in an effort to enhance the efficacy of NK cell-based therapy against solid tumors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the staff at the animal facility at the Department of Microbiology, Tumor and Cell Biology, Karolinska Institutet. Dhifaf Sarhan and Rolf Kiessling at the Department of Oncology-Pathology, Karolinska Institutet for intellectual input. This work was supported by funding from The Swedish Research Council (#522-208-2377), The Swedish Cancer Society (#CAN 2012/474), FP7 Marie Curie re-integration Grant (#246759), The Cancer Society in Stockholm (#121132), the Swedish Society of Medicine (#325751), Karolinska Institutet, Jeanssons Stiftelser, Åke Wibergs Stiftelse, Magnus Bergvalls Stiftelse, Fredrik och Ingrid Thurings Stiftelse, Stiftelsen Clas Groschinskys Minnesfond, and the Division of Intramural Research at the Hematology Branch of the National Heart Blood and Lung Institute.

Conflict of interest

None.

Abbreviations

- AML

Acute myeloid leukemia

- BLI

Bioluminescence imaging

- CCR

C-C chemokine receptor

- Cr

Chromium

- CTL

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- CXCL

C-X-C motif ligand

- CXCR

C-X-C motif receptor

- DiR

1,1′-Dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindotricarbocyanine iodide

- DNAM-1

DNAX accessory molecule-1

- DOX

Doxorubicin

- E:T

Effector-to-target ratio

- EBV

Epstein–Barr virus

- FCS

Fetal calf serum

- Gy

Gray

- HLA

Human leukocyte antigen

- I.P

Intraperitoneally

- I.V

Intravenous

- IDO

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase

- IFN

Interferon

- IL

Interleukin

- IP-10

IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10

- I-TAC

Interferon-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant

- LCL

Lymphoblastoid cell line

- LFA-1

Leukocyte function-associated antigen 1

- LNs

Lymph nodes

- MFI

Mean fluorescence imaging

- MICA/B

Major histocompatibility complex class I-related chains A and B

- MIG

Monokine induced by gamma interferon

- MOI

Multiplicity of infection

- NCRs

Natural cytotoxicity receptors

- NK

Natural killer

- NKG2D

Natural killer group 2 membrane D

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- PD-L1

Programmed death-ligand 1

- PGE2

Prostaglandin E2

- poly-I:C

Poly-inositol–cytidine

- PVR

Poliovirus receptor

- RCC

Renal cell carcinoma

- S.C

Subcutaneous

- TGF

Transforming growth factor

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- TRAIL

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

- ULBPs

UL16-binding proteins

- VLA-4

Very late antigen-4

Footnotes

Parts of the work have been published at the Cold Spring Harbor Asia Conference—Tumor Immunology and Immunotherapy, Oct 28th–Nov 1st 2013, Suzhou, China.

References

- 1.Sarhan D, D’Arcy P, Wennerberg E, Liden M, Hu J, Winqvist O, Rolny C, Lundqvist A. Activated monocytes augment TRAIL-mediated cytotoxicity by human NK cells through release of IFN-gamma. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43(1):249–257. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson DM, Jr, Bakan CE, Zhang S, Collins SM, Liang J, Srivastava S, Hofmeister CC, Efebera Y, Andre P, Romagne F, Blery M, Bonnafous C, Zhang J, Clever D, Caligiuri MA, Farag SS. IPH2101, a novel anti-inhibitory KIR antibody, and lenalidomide combine to enhance the natural killer cell versus multiple myeloma effect. Blood. 2011;118(24):6387–6391. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-360255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salagianni M, Lekka E, Moustaki A, Iliopoulou EG, Baxevanis CN, Papamichail M, Perez SA. NK cell adoptive transfer combined with Ontak-mediated regulatory T cell elimination induces effective adaptive antitumor immune responses. J Immunol. 2011;186(6):3327–3335. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim EK, Ahn YO, Kim S, Kim TM, Keam B, Heo DS (2013) Ex vivo activation and expansion of natural killer cells from patients with advanced cancer with feeder cells from healthy volunteers. Cytotherapy 15(2):231–241.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jcyt.2012.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Berg M, Lundqvist A, McCoy P, Jr, Samsel L, Fan Y, Tawab A, Childs R. Clinical-grade ex vivo-expanded human natural killer cells up-regulate activating receptors and death receptor ligands and have enhanced cytolytic activity against tumor cells. Cytotherapy. 2009;11(3):341–355. doi: 10.1080/14653240902807034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imai C, Iwamoto S, Campana D. Genetic modification of primary natural killer cells overcomes inhibitory signals and induces specific killing of leukemic cells. Blood. 2005;106(1):376–383. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takanami I, Takeuchi K, Giga M. The prognostic value of natural killer cell infiltration in resected pulmonary adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;121(6):1058–1063. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.113026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishigami S, Natsugoe S, Tokuda K, Nakajo A, Che X, Iwashige H, Aridome K, Hokita S, Aikou T. Prognostic value of intratumoral natural killer cells in gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;88(3):577–583. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000201)88:3<577::AID-CNCR13>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villegas FR, Coca S, Villarrubia VG, Jimenez R, Chillon MJ, Jareno J, Zuil M, Callol L. Prognostic significance of tumor infiltrating natural killer cells subset CD57 in patients with squamous cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2002;35(1):23–28. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5002(01)00292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coca S, Perez-Piqueras J, Martinez D, Colmenarejo A, Saez MA, Vallejo C, Martos JA, Moreno M. The prognostic significance of intratumoral natural killer cells in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;79(12):2320–2328. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19970615)79:12<2320::AID-CNCR5>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Urbani E, Perruccio K, Shlomchik WD, Tosti A, Posati S, Rogaia D, Frassoni F, Aversa F, Martelli MF, Velardi A. Effectiveness of donor natural killer cell alloreactivity in mismatched hematopoietic transplants. Science. 2002;295(5562):2097–2100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller JS, Soignier Y, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, McNearney SA, Yun GH, Fautsch SK, McKenna D, Le C, Defor TE, Burns LJ, Orchard PJ, Blazar BR, Wagner JE, Slungaard A, Weisdorf DJ, Okazaki IJ, McGlave PB. Successful adoptive transfer and in vivo expansion of human haploidentical NK cells in patients with cancer. Blood. 2005;105(8):3051–3057. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parkhurst MR, Riley JP, Dudley ME, Rosenberg SA. Adoptive transfer of autologous natural killer cells leads to high levels of circulating natural killer cells but does not mediate tumor regression. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(19):6287–6297. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curti A, Ruggeri L, D’Addio A, Bontadini A, Dan E, Motta MR, Trabanelli S, Giudice V, Urbani E, Martinelli G, Paolini S, Fruet F, Isidori A, Parisi S, Bandini G, Baccarani M, Velardi A, Lemoli RM. Successful transfer of alloreactive haploidentical KIR ligand-mismatched natural killer cells after infusion in elderly high risk acute myeloid leukemia patients. Blood. 2011;118(12):3273–3279. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-329508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lundqvist A, Berg M, Smith A, Childs RW. Bortezomib treatment to potentiate the anti-tumor immunity of ex vivo expanded adoptively infused autologous natural killer cells. J Cancer. 2011;2:383–385. doi: 10.7150/jca.2.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nowbakht P, Ionescu MC, Rohner A, Kalberer CP, Rossy E, Mori L, Cosman D, De Libero G, Wodnar-Filipowicz A. Ligands for natural killer cell-activating receptors are expressed upon the maturation of normal myelomonocytic cells but at low levels in acute myeloid leukemias. Blood. 2005;105(9):3615–3622. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanchez-Correa B, Morgado S, Gayoso I, Bergua JM, Casado JG, Arcos MJ, Bengochea ML, Duran E, Solana R, Tarazona R. Human NK cells in acute myeloid leukaemia patients: analysis of NK cell-activating receptors and their ligands. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60(8):1195–1205. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1050-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Q, Hokland ME, Bryant JL, Zhang Y, Nannmark U, Watkins SC, Goldfarb RH, Herberman RB, Basse PH. Tumor-localization by adoptively transferred, interleukin-2-activated NK cells leads to destruction of well-established lung metastases. Int J Cancer. 2003;105(4):512–519. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hagenaars M, Zwaveling S, Kuppen PJ, Ensink NG, Eggermont AM, Hokland ME, Basse PH, van de Velde CJ, Fleuren GJ, Nannmark U. Characteristics of tumor infiltration by adoptively transferred and endogenous natural-killer cells in a syngeneic rat model: implications for the mechanism behind anti-tumor responses. Int J Cancer. 1998;78(6):783–789. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19981209)78:6<783::AID-IJC17>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher B, Packard BS, Read EJ, Carrasquillo JA, Carter CS, Topalian SL, Yang JC, Yolles P, Larson SM, Rosenberg SA. Tumor localization of adoptively transferred indium-111 labeled tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7(2):250–261. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maghazachi AA. Role of chemokines in the biology of natural killer cells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2010;341:37–58. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groom JR, Luster AD. CXCR3 ligands: redundant, collaborative and antagonistic functions. Immunol Cell Biol. 2011;89(2):207–215. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Mackay CR, Lanzavecchia A. Flexible programs of chemokine receptor expression on human polarized T helper 1 and 2 lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1998;187(6):875–883. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.6.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Somanchi SS, Somanchi A, Cooper LJ, Lee DA. Engineering lymph node homing of ex vivo expanded human natural killer cells via trogocytosis of the chemokine receptor CCR7. Blood. 2012;119(22):5164–5172. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-389924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng W, Ye Y, Rabinovich BA, Liu C, Lou Y, Zhang M, Whittington M, Yang Y, Overwijk WW, Lizee G, Hwu P. Transduction of tumor-specific T cells with CXCR2 chemokine receptor improves migration to tumor and antitumor immune responses. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(22):5458–5468. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, Charoentong P, Kirilovsky A, Bindea G, Berger A, Camus M, Gillard M, Bruneval P, Fridman WH, Pages F, Trajanoski Z, Galon J. Biomolecular network reconstruction identifies T-cell homing factors associated with survival in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(4):1429–1440. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Berger A, Bindea G, Meatchi T, Bruneval P, Trajanoski Z, Fridman WH, Pages F, Galon J. Histopathologic-based prognostic factors of colorectal cancers are associated with the state of the local immune reaction. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(6):610–618. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pages F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Asslaber M, Tosolini M, Bindea G, Lagorce C, Wind P, Marliot F, Bruneval P, Zatloukal K, Trajanoski Z, Berger A, Fridman WH, Galon J. In situ cytotoxic and memory T cells predict outcome in patients with early-stage colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(35):5944–5951. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luster AD, Unkeless JC, Ravetch JV. Gamma-interferon transcriptionally regulates an early-response gene containing homology to platelet proteins. Nature. 1985;315(6021):672–676. doi: 10.1038/315672a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harlin H, Meng Y, Peterson AC, Zha Y, Tretiakova M, Slingluff C, McKee M, Gajewski TF. Chemokine expression in melanoma metastases associated with CD8 + T-cell recruitment. Cancer Res. 2009;69(7):3077–3085. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kondo T, Nakazawa H, Ito F, Hashimoto Y, Osaka Y, Futatsuyama K, Toma H, Tanabe K. Favorable prognosis of renal cell carcinoma with increased expression of chemokines associated with a Th1-type immune response. Cancer Sci. 2006;97(8):780–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zipin-Roitman A, Meshel T, Sagi-Assif O, Shalmon B, Avivi C, Pfeffer RM, Witz IP, Ben-Baruch A. CXCL10 promotes invasion-related properties in human colorectal carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67(7):3396–3405. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Lagorce-Pages C, Tosolini M, Camus M, Berger A, Wind P, Zinzindohoue F, Bruneval P, Cugnenc PH, Trajanoski Z, Fridman WH, Pages F. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313(5795):1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Metelitsa LS, Wu HW, Wang H, Yang Y, Warsi Z, Asgharzadeh S, Groshen S, Wilson SB, Seeger RC. Natural killer T cells infiltrate neuroblastomas expressing the chemokine CCL2. J Exp Med. 2004;199(9):1213–1221. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adler EP, Lemken CA, Katchen NS, Kurt RA. A dual role for tumor-derived chemokine RANTES (CCL5) Immunol Lett. 2003;90(2–3):187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Erreni M, Bianchi P, Laghi L, Mirolo M, Fabbri M, Locati M, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Expression of chemokines and chemokine receptors in human colon cancer. Methods Enzymol. 2009;460:105–121. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)05205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inngjerdingen M, Damaj B, Maghazachi AA. Expression and regulation of chemokine receptors in human natural killer cells. Blood. 2001;97(2):367–375. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.2.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hodge DL, Schill WB, Wang JM, Blanca I, Reynolds DA, Ortaldo JR, Young HA. IL-2 and IL-12 alter NK cell responsiveness to IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10 by down-regulating CXCR3 expression. J Immunol. 2002;168(12):6090–6098. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanna J, Wald O, Goldman-Wohl D, Prus D, Markel G, Gazit R, Katz G, Haimov-Kochman R, Fujii N, Yagel S, Peled A, Mandelboim O. CXCL12 expression by invasive trophoblasts induces the specific migration of CD16-human natural killer cells. Blood. 2003;102(5):1569–1577. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beider K, Nagler A, Wald O, Franitza S, Dagan-Berger M, Wald H, Giladi H, Brocke S, Hanna J, Mandelboim O, Darash-Yahana M, Galun E, Peled A. Involvement of CXCR4 and IL-2 in the homing and retention of human NK and NK T cells to the bone marrow and spleen of NOD/SCID mice. Blood. 2003;102(6):1951–1958. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evans JH, Horowitz A, Mehrabi M, Wise EL, Pease JE, Riley EM, Davis DM. A distinct subset of human NK cells expressing HLA-DR expand in response to IL-2 and can aid immune responses to BCG. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41(7):1924–1933. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kajitani K, Tanaka Y, Arihiro K, Kataoka T, Ohdan H. Mechanistic analysis of the antitumor efficacy of human natural killer cells against breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(1):139–155. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1944-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lim O, Lee Y, Chung H, Her JH, Kang SM, Jung MY, Min B, Shin H, Kim TM, Heo DS, Hwang YK, Shin EC. GMP-compliant, large-scale expanded allogeneic natural killer cells have potent cytolytic activity against cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e53611. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sutlu T, Stellan B, Gilljam M, Quezada HC, Nahi H, Gahrton G, Alici E. Clinical-grade, large-scale, feeder-free expansion of highly active human natural killer cells for adoptive immunotherapy using an automated bioreactor. Cytotherapy. 2010;12(8):1044–1055. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2010.504770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loos T, Dekeyzer L, Struyf S, Schutyser E, Gijsbers K, Gouwy M, Fraeyman A, Put W, Ronsse I, Grillet B, Opdenakker G, Van Damme J, Proost P. TLR ligands and cytokines induce CXCR3 ligands in endothelial cells: enhanced CXCL9 in autoimmune arthritis. Lab Invest. 2006;86(9):902–916. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Furuya M, Suyama T, Usui H, Kasuya Y, Nishiyama M, Tanaka N, Ishiwata I, Nagai Y, Shozu M, Kimura S. Up-regulation of CXC chemokines and their receptors: implications for proinflammatory microenvironments of ovarian carcinomas and endometriosis. Hum Pathol. 2007;38(11):1676–1687. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muthuswamy R, Berk E, Junecko BF, Zeh HJ, Zureikat AH, Normolle D, Luong TM, Reinhart TA, Bartlett DL, Kalinski P. NF-kappaB hyperactivation in tumor tissues allows tumor-selective reprogramming of the chemokine microenvironment to enhance the recruitment of cytolytic T effector cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72(15):3735–3743. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-4136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wennerberg E, Sarhan D, Carlsten M, Kaminskyy VO, D’Arcy P, Zhivotovsky B, Childs R, Lundqvist A. Doxorubicin sensitizes human tumor cells to NK cell- and T-cell-mediated killing by augmented TRAIL receptor signaling. Int J Cancer. 2013;133(7):1643–1652. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wendel M, Galani IE, Suri-Payer E, Cerwenka A. Natural killer cell accumulation in tumors is dependent on IFN-gamma and CXCR3 ligands. Cancer Res. 2008;68(20):8437–8445. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Casado JG, Pawelec G, Morgado S, Sanchez-Correa B, Delgado E, Gayoso I, Duran E, Solana R, Tarazona R. Expression of adhesion molecules and ligands for activating and costimulatory receptors involved in cell-mediated cytotoxicity in a large panel of human melanoma cell lines. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58(9):1517–1526. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0682-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lakshmikanth T, Burke S, Ali TH, Kimpfler S, Ursini F, Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Umansky V, Paschen A, Sucker A, Pende D, Groh V, Biassoni R, Hoglund P, Kato M, Shibuya K, Schadendorf D, Anichini A, Ferrone S, Velardi A, Karre K, Shibuya A, Carbone E, Colucci F. NCRs and DNAM-1 mediate NK cell recognition and lysis of human and mouse melanoma cell lines in vitro and in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(5):1251–1263. doi: 10.1172/JCI36022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee JH, Park S, Cheon S, Lee JH, Kim S, Hur DY, Kim TS, Yoon SR, Yang Y, Bang SI, Park H, Lee HT, Cho D. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) enhances NK susceptibility of human melanoma cells via Hsp60-mediated FAS expression. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41(10):2937–2946. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mao Y, Sarhan D, Steven A, Seliger B, Kiessling R, Lundqvist A. Inhibition of tumor-derived prostaglandin-e2 blocks the induction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and recovers natural killer cell activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(15):4096–4106. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.