Abstract

Antigen cross-presentation by dendritic cells (DCs) is thought to play a critical role in driving a polyclonal and durable T cell response against cancer. It follows, therefore, that the capacity of emerging immunotherapeutic agents to orchestrate tumour eradication may depend on their ability to induce antigen cross-presentation. ImmTACs [immune-mobilising monoclonal TCRs (T cell receptors) against cancer] are a new class of soluble bi-specific anti-cancer agents that combine pico-molar affinity TCR-based antigen recognition with T cell activation via a CD3-specific antibody fragment. ImmTACs specifically recognise human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-restricted tumour-associated antigens, presented by cancer cells, leading to T cell redirection and a potent anti-tumour response. Using an ImmTAC specific for a HLA-A*02-restricted peptide derived from the melanoma antigen gp100 (termed IMCgp100), we here observe that ImmTAC-driven melanoma-cell death leads to cross-presentation of melanoma antigens by DCs. These, in turn, can activate both melanoma-specific T cells and polyclonal T cells redirected by IMCgp100. Moreover, activation of melanoma-specific T cells by cross-presenting DCs is enhanced in the presence of IMCgp100; a feature that serves to increase the prospect of breaking tolerance in the tumour microenvironment. The mechanism of DC cross-presentation occurs via ‘cross-dressing’ which involves the rapid and direct capture by DCs of membrane fragments from dying tumour cells. DC cross-presentation of gp100-peptide-HLA complexes was visualised and quantified using a fluorescently labelled soluble TCR. These data demonstrate how ImmTACs engage with the innate and adaptive components of the immune system enhancing the prospect of mediating an effective and durable anti-tumour response in patients.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-014-1525-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: ImmTAC, T cell receptor, Cross-presentation, Cross-dressing, Dendritic cell, Cancer immunotherapy

Introduction

There is increasing evidence to suggest that an effective anti-tumour response in cancer patients requires the coordinated action of the innate and adaptive immune systems [1, 2]. In the adaptive immune response, studies in in vivo models and, more recently in cancer patients, have shown that CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) are the key effectors involved in the killing of tumour cells [3, 4]. Within the innate immune system, dendritic cells (DCs) are pivotal to anti-tumour immunity. DCs can detect dying cancer cells, become activated, and display tumour antigens on their cell surface, leading to the potent activation of T cells. This process, referred to as antigen cross-presentation, can occur locally at the tumour site or in draining lymph nodes, resulting in the activation of naive T cells. There are several lines of evidence that support the role of DCs in anti-tumour immunity [5]. First, compared to other hematopoietic cells, DCs are particularly well endowed with co-stimulatory molecules to cross-present antigens to CD8+ T cells. Second, tumour-infiltrating DCs purified from tumour samples have the capacity to cross-present tumour antigens in vitro. Third, mice that are deficient in DCs fail to generate an anti-tumour T cell response [6–8]. It is therefore considered that the capacity for immunotherapeutic strategies to elicit effective anti-tumour responses in patients depends on the degree of engagement with both the adaptive and innate immune systems.

The development of targeted immunotherapeutics based on CD8+ T cells, and in particular the T cell receptor (TCR), has been the focus of intense investigation in recent years (reviewed in [9]). Unlike antibodies, TCRs recognise antigens derived from intracellular proteins which first have been processed, then presented on the cell surface as peptide fragments in association with human leucocyte antigen (HLA) molecules. Since the vast majority of tumour-associated antigens is derived from intracellular proteins, TCR-based therapeutics offer immense scope as novel anti-cancer agents. However, there are major challenges associated with the use of naturally occurring TCRs. First, their inherent low affinity for antigen (typically in the low μM range), which in the context of TAAs is usually particularly low [10–12], and second, the poor stability of TCRs in a soluble form. The development of strategies to overcome these issues is now opening up the possibilities of TCR-based therapies. TCRs possessing enhanced affinity for antigen can be created by directed molecular evolution of the antigen binding regions [13–15]. For example, increases in TCR antigen affinity in excess of one million-fold have been achieved using phage display [15]. Producing TCR molecules which are both stable and soluble can be achieved by omitting the transmembrane domain and introducing a non-native disulphide bond, resulting in ‘monoclonal’ or ‘mTCRs’ [16]. These innovations have led us to develop a platform of novel bi-specific therapeutic agents, termed ImmTACs, which combine a high-affinity mTCR domain with a T cell activating anti-CD3 domain and are capable of generating a potent anti-tumour response in vitro and in vivo [17, 18].

The potential for ImmTACs to engage with and enhance the host’s immune response through antigen cross-presentation by dendritic cells is investigated here. In this study, we utilised an ImmTAC, known as IMCgp100, which specifically recognises a HLA-A*02-restricted peptide derived from the melanocyte differentiation antigen gp100 (gp100280–288) [19], and currently undergoing evaluation in a phase I clinical trial (NCT01211262). The data reported here show that IMCgp100-driven killing of melanoma cells induces cross-presentation of TAAs on DCs, leading to (1) activation of melanoma-specific T cells, which is potentiated in the presence of IMCgp100 and (2) activation of polyclonal T cells redirected by IMCgp100. In addition, using a fluorescently labelled mTCR specific for the gp100-peptide-HLA complex, cross-presented gp100 is directly visualised on the DC cell surface, enabling a quantitative assessment of cross-presentation. Finally, the data reveal that ImmTAC-driven cross-presentation may exploit a mechanism of antigen uptake termed ‘DC cross-dressing’.

Materials and Methods

ImmTAC engineering

IMCgp100, a gp100-specific ImmTAC, was prepared as previously described [17]. Briefly, a high-affinity TCR was generated from a wild-type gp100 TCR using directed molecular evolution and phage display selection [15]. The resulting high-affinity TCR beta chain was fused to a humanised CD3-specific scFv via a flexible linker and the alpha and beta chains of the resulting ImmTAC expressed in E. coli as inclusion bodies. ImmTACs were then refolded and purified as previously described [16].

Human T cell clones and cell lines

MEL187.c5 and EBV176.c4.1 CD8+ T cell clones, specific for Melan A/MART-126–35 and EBV BRLF1259–267, respectively, were generated and maintained in-house as described previously [20]. Mel624 melanoma cells (HLA-A*0201+; Melan A+ and gp100+) were obtained from Thymed; SK-Mel-24 (HLA-A*0201+; gp100− and Melan A−) and SK-Mel-28 (HLA-A*0201−; gp100+ and Melan A+) melanoma cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The HLA-A*0201 status of the cell lines was determined by flow cytometry, following staining with mouse anti-human HLA-A*0201 PE-conjugated antibody (Serotec) 7 days after transduction. Intracellular staining with mouse anti-gp100 (NK1/beteb; Hycult Biotech) and mouse anti-Mar1 (Ab-1; Calbiochem) antibodies was used to confirm the expression of gp100 and Melan A.

Generation of human DCs, autologous CD8+ and CD4+ T cells

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were prepared from healthy donors by Ficoll-Hypaque (Robbins Scientific) density gradient centrifugation. CD14+ monocyte cells isolated by positive selection with magnetic micro beads (Miltenyi) were differentiated for 7 days in culture in the presence of 800 U/ml GM-CSF and 1,000 U/ml IL-4. Mature DCs (mDC) were generated by treatment with 100 ng/ml LPS for 24 h and 0.5 μg/ml soluble CD40L (Enzo Life Science) for a further 24 h. The purity and activation state of DCs were determined by staining with mouse anti-human CD80 PE-Cy7, CD83 APC, CD86 PE, HLA-DR PerCP-Cy5.5 and CD14 APC-Cy7 antibodies (BD BioSciences). Samples were acquired with FACSAriaII flow cytometer (BD BioSciences) and analysed with FlowJo software (TreeStar Inc.). Magnetic bead immunodepletion was used to enrich CD8+ and CD4+ T cells from freshly prepared peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) by negative selection according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi).

Preparation of apoptotic cells and DC phagocytosis

Apoptotic Mel624 cells were generated either by incubating the target cells with 0.1 nM IMCgp100 and a viral T cell clone (EBV176.c4.1) for 24 h or by treating the target cells with an apoptotic cocktail (5 μM staurosporine, 40 μg/ml anisomycin and 5 μM etoposide) for 5 h. The percentage of target killing or apoptotic rate was determined by pre-labelling targets with DiO (Life Technology) and determining the percentage of DiO+ cells that have become positive for annexin-V PE-conjugated and 7-AAD reagents (Guava Nexin Reagent; Millipore). In all cases, 100 % of target cells were determined to be apoptotic. When the apoptotic melanoma cells were generated by IMCgp100-redirected killing, EBV176.c4.1 T cells were eliminated by positive selection with anti-CD2 microbeads (Miltenyi). Immature DCs were incubated with apoptotic cells at 1:1 ratio for 24 h, washed with PBS and incubated for further 24 h in complete medium. The phagocytosis rate of apoptotic/necrotic cells by DCs was determine by labelling DCs with DiO dye and apoptotic cells with DiI dye (Life Technology) and detecting by FACS the percentage of DiO+ DC cells that became DiI+.

Cellular assays

CytoTox 96® non-radioactive cytotoxicity assay (Promega) was used to determine LDH release from dying target cells in the presence of increasing concentrations of IMCgp100. CD8+ T cells, obtained from a healthy donor, were used at 100,000 cells per well at an effector target ratio of 10:1. Experiments were performed as described previously [17]. Briefly, target and effector cells were plated in a 96-round-well plate in triplicate, and IMCgp100 was added at the concentrations indicated in Fig. 1b. The plate was incubated for 24 h at 37 °C/5 % CO2, and the detection of LDH release from the target cells was measured in the supernatants according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To calculate the percentage lysis, the LDH signal derived from culture medium values alone was subtracted from all wells and volume correction control values were subtracted from target maximum release wells. Subsequently, the percentage lysis was calculated as (experimental LDH release − effector spontaneous LDH release − target spontaneous LDH release)/(target maximum LDH release − target spontaneous LDH release) × 100.

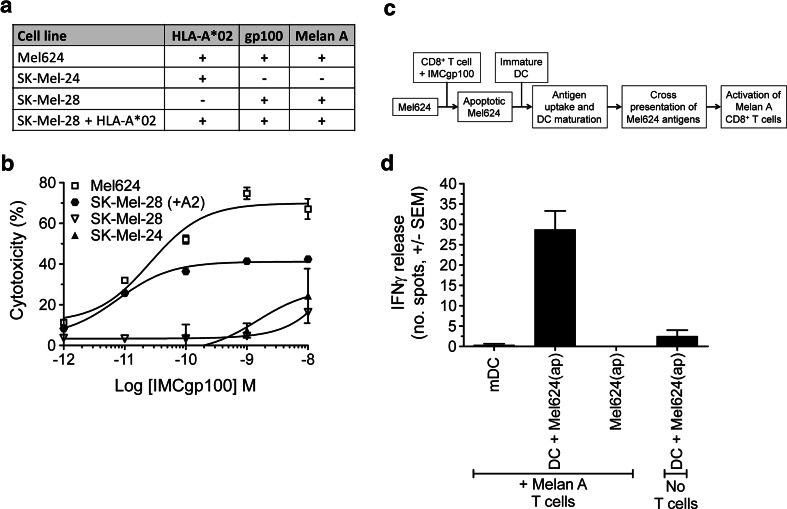

Fig. 1.

IMCgp100-driven killing of melanoma cell lines leads to antigen cross-presentation by dendritic cells. a Details of the cell lines used in this study. b IMCgp100 dose–response curve showing redirected T cell cytotoxicity against the cell lines detailed in (a). Cytotoxicity was determined by LDH release after 24 h. Polyclonal CD8+ T cells, obtained from a healthy donor, were used at 100,000 cells per well at an effector target ratio of 10:1. Data shown represent the average of three independent measurements ± SEM. c Flow diagram summarising the experimental approach used to monitor IMCgp100-driven cross-presentation. d Apoptotic Mel624 cells [denoted Mel624(ap)] were produced by IMCgp100-redirected CD8+ T cell killing and subsequently incubated with immature DCs for 48 h to allow antigen uptake. IMCgp100 was used at a concentration of 0.1 nM. The resulting mature DCs were assessed for their ability to induce IFNγ release from Melan-A-specific CD8+ T cells. A further sample was prepared using LPS-matured DCs (mDC) only. Data shown represent the average of three independent measurements ± SEM. Additional control samples were prepared in a similar manner but in the absence of either DCs or Melan A T cells. These control measurements were performed in duplicate and are shown as average ± SEM

IFNγ ELISpot assays were carried out in triplicate according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BD BioSciences). Each well contained 2.5x104 DCs and 1x104 effector T cells (CD4+, CD8+) or 3 × 103 MEL187.c5 T cell clone cells. Plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C/5 % CO2 and quantified after development using an automated ELISpot reader (Immunospot Series 5 Analyzer, Cellular Technology Ltd.).

Data were analysed using Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software)

T cell proliferation

T cell proliferation was measured by CFSE labelling and the percentage of dividing cells determined. Briefly, autologous CD8+ T cells were resuspended at 1 × 106 cells/ml, in pre-warmed (37 °C) sterile PBS, supplemented with 0.1 % BSA. T cells were labelled with 2 μM CFSE (Life Technologies) for 10 min at 37 °C and quenched by addition of ice-cold RPMI with 10 % FCS for 5 min. 4 × 104 DCs HLA-A*0201+ and HLA-A*0201− that have been co-cultured for 48 h with chemically induced apoptotic melanoma cells were plated in the presence of 2 × 105 autologous CD8+ T cells (5:1 effector to target ratio) in 200 μl R10. IMCgp100 was added at 1 nM final concentration. Cells were incubated at 37 °C/5 % CO2 for 7 days. 10,000 CFSE+ events were acquired on a FC500 flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter), and the files analysed with FlowJo version 7.6 (TreeStar Inc.).

Cytokine analysis

Polyclonal CD8+ T cells were incubated with DCs in the presence of 0.1 nM IMCgp100 for 3 days at 37 °C. 5 h before the end point, the co-culture was incubated with 1 μg/ml brefeldin A (GolgiPlug, BD BioSciences), 0.7 μl/ml monensin (GolgiStop, BD BioSciences) and mouse anti-human CD107 APC antibody (BD BioSciences) for 5 h. The cells were washed in PBS, stained with mouse anti-human CD8 APC-Cy7 antibody (BD BioScences) for 20 min on ice. After washing, cells were fixed and permeabilised using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD BioSciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After permeabilisation, the cells were washed twice in the supplied buffer, and then stained with directly conjugated mouse anti-human IFNγ FITC, TNFα PE and IL-2 PE-Cy7 antibodies (BD BioSciences) and mouse anti-human MIP-1β PerCP (R&D Systems) for 1 h. The data were acquired on FACS AriaII flow cytometer (BD BioSciences) and analysed by FloJo version 7.6 (TreeStar Inc.)

Microscopy

Soluble high-affinity mTCRs were produced as previously described [15, 16]. Phase-contrast and PE-fluorescence images were acquired as previously described using a Zeiss 200 M/Universal Imaging system [21]. Z-stack fluorescent images were taken (21 individual planes, 0.7 μm apart) to cover the entire 3D surface of the cell. Counting the number of fluorescent spots on individual cells was undertaken manually using the 2D images. The number of cells counted for each sample is detailed in the legend to Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Cross-presented gp100-HLA-A*0201 complex is visualised and quantified on the DC cell surface. a A high-affinity biotinylated mTCR specific for the gp100-HLA-A*0201 complex was used to detect pHLA complexes on DCs after antigen uptake from chemically induced apoptotic Mel624 cells. An mTCR with alternative specificity was used as a control. Representative phase-contrast and fluorescence images are shown. The scale bar represents 20 μm. b The number of fluorescent spots on individual DCs was quantified manually from 2D Z-stack images. Additional control measurements were made using LPS-matured DCs, in the absence of apoptotic Mel624 cells. From left to right, the number of cells counted was 15, 54, 10 and 78. Statistical significance was evaluated using an unpaired t test. P values were determined at the 95 % confidence interval. c and d The same experiments analysis was performed using HLA-A*0201− DCs. From left to right, the number of cells counted was 9, 60, 6 and 22

Lentivirus manufacture and SK-Mel-28 cell transductions

A T150 flask of semi-confluent HEK293T cells were transfected with 15 μg of lentivector encoding the human HLA-A*0201 antigen, along with a total of 43 μg of three packaging plasmids [22], using Express-In transfection reagent (Open Biosystems). Supernatants collected at 24 h and 48 h were concentrated by centrifugation at 10,000×g for 16 h at 4 °C. Melanoma SK-Mel-28 cells were plated at 3 × 106 cells/well in a six well plate and transduced by addition of 1 ml crude lentiviral supernatant. HLA-A*0201 transduction efficiency was determined by flow cytometry, following staining with mouse anti-human HLA-A*0201 PE-conjugated antibody (Serotec) 7 days after transduction.

Results

IMCgp100-driven tumour cell killing results in antigen cross-presentation by dendritic cells

The ability of IMCgp100 to redirect T cells to specifically target HLA-A*0201 cells expressing gp100 was examined by monitoring dose-dependent cytolysis of three melanoma cell lines (Fig. 1a). Cell lysis was determined by release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). In line with a previous study [17], IMCgp100 produced a potent redirected CD8+ T cell response against Mel624 cells (gp100+/HLA-A*0201+) (Fig. 1b). The specificity of the response was verified using cell lines which either do not express gp100 (SK-Mel-24) or express an alternative HLA type (SK-Mel-28). These data demonstrate that IMCgp100 retains specificity when used at concentrations of 10−9 M and below. Further experiments showed that insertion of the HLA-A*0201 gene into SK-Mel-28 cells led to IMCgp100-driven lysis of these cells. The difference in the level of cytotoxicity observed between Mel624 and SK-Mel-28 (with HLA-A*0201) may be explained by the higher levels of HLA displayed on Mel624 cells, the level of gp100 expression between the two cells lines is comparable (see supplementary Figure 1).

It was then examined whether IMCgp100-driven killing of Mel624 cells could promote the cross-presentation of melanoma antigens on DCs. IMCgp100-redirected viral-specific (i.e. irrelevant) CD8+ cytotoxic T cells were used to induce killing of Mel624 targets. Apoptosis was confirmed as described in the methods, and the viral T cells were removed by positive selection for CD2. The resulting apoptotic Mel624 cells were then incubated with an equivalent number of immature HLA-A*0201 DCs for 48 h, allowing antigen uptake to occur. A functional assay was then used to determine whether the resulting DCs were cross-presenting the Melan-A-melanoma antigen. This was done by incubating them with CD8+ T cells specific for the HLA-A*02-restricted Melan A26–35 peptide (see Fig. 1c for an outline of the experimental approach). Activation of Melan A T cells, determined by IFNγ release, was observed with DCs exposed to apoptotic Mel624 cells (Fig. 1d), whereas with LPS-matured DCs (i.e. prepared in the absence of apoptotic Mel624), no activation was observed. To confirm that the response was mediated by DCs, rather than by apoptotic Mel624 cells directly, or as a result of contaminating IFNγ produced by IMCgp100-redirected viral T cells, additional samples were prepared in the same manner as described above, but in the absence of either immature DCs or Melan A T cells (Fig. 1d). Apoptotic Mel624 cells were not able to produce a T cell response in the absence of DCs, as expected, since they can only present antigen to CD8+ T cells in a 6–24 h window after induction of apoptosis, well outside the 48 h used here [23]. Furthermore, the lack of IFNγ in either of these control samples indicates that any residual IFNγ is effectively removed during the experiment. These data indicate that IMCgp100-driven tumour cell killing can induce cross-presentation of TAAs by dendritic cells.

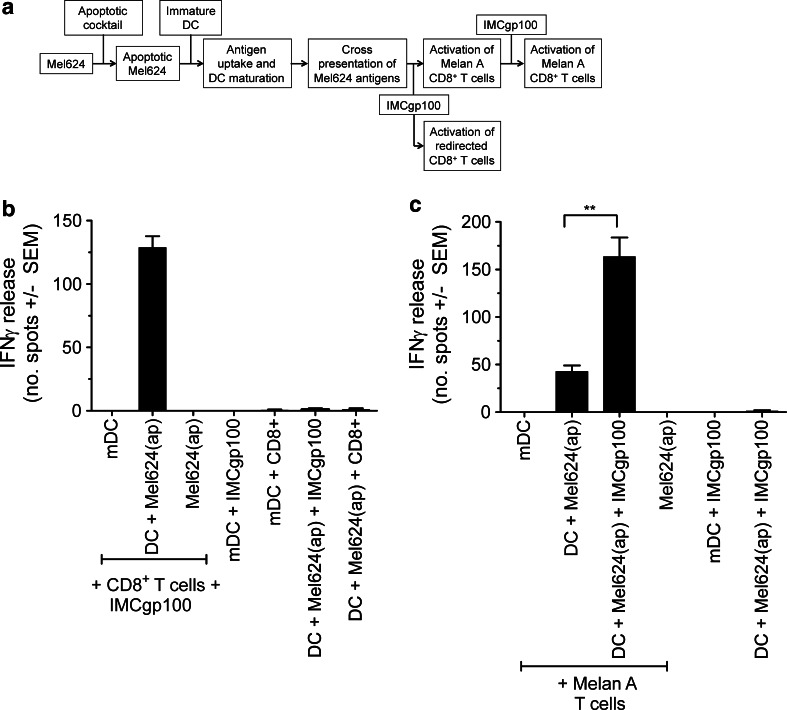

Cross-presentation in the presence of IMCgp100 enhances activation of TAA-specific T cells

To investigate the potential of IMCgp100 to respond to cross-presented gp100 a similar experimental strategy was followed to that used above, except that, for technical ease, apoptotic melanoma cells were prepared by chemically induced apoptosis (see Fig. 2a for an outline of the experimental approach). The data show that autologous polyclonal CD8+ T cells were activated in response to cross-presenting DCs in the presence of IMCgp100 (Fig. 2b). No activation was apparent in the absence of IMCgp100. We then sought to establish the effect of IMCgp100 on DC-mediated activation of TAA-specific T cells. Comparable to the data shown in Fig. 1d, Melan A T cells were activated by cross-presenting DCs (Fig. 2c). However, in the presence of IMCgp100, activation of Melan A T cells increased significantly (p < 0.05), indicating that IMCgp100 can enhance activation of TAA-specific T cells and may therefore contribute to overcoming T cell tolerance in vivo.

Fig. 2.

IMCgp100 redirects T cells in response to cross-presented antigen and enhances activation of TAA-specific T cells. a Flow diagram summarising the experimental approach used. b Apoptotic Mel624 cells [denoted Mel624(ap)] were prepared by chemically induced apoptosis and subsequently incubated with immature DCs for 48 h to allow antigen uptake. The resulting mature DCs were assessed for their ability to induce IFNγ release from IMCgp100-redirected autologous polyclonal CD8+ T cells. c The same approach was used to monitor activation of Melan-A-specific CD8+ T cells in the presence or absence of 0.1 nM IMCgp100. In each case, a further sample was prepared using LPS-matured DCs (mDC) only. Data shown represent the average of three independent measurements ± SEM. Additional control samples were prepared in a similar manner in the absence of various components as indicated on the graph. Control measurements were performed in duplicate and are shown as average ± SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated using an unpaired t test. p values were determined at the 95 % confidence interval

IMCgp100 elicits multiple effector functions

To provide a broader appreciation of the immune responses induced by IMCgp100-recognition of cross-presented antigens on DCs, it was first demonstrated that IMCgp100 was able to redirect both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells to target melanoma tumour cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3a, b). The potency of the CD8+ T cell response was comparable to that shown in Fig. 1b, suggesting that IMCgp100 recognised cross-presented antigen in a similar manner to antigens displayed directly on tumour cells. Although, the potency of CD4+ T cell activation was lower than that of CD8+ T cells, activation of both T cell subsets indicates the potential for a co-ordinated immune response in vivo. Next, to further analyse the activation of IMCgp100-redirected CD8+ T cells against cross-presented antigen, intracellular production of inflammatory cytokines IFNγ, IL-2, TNFα and MIP-1β as well as secretion of lytic granules (determined by CD107a expression) was confirmed (Fig. 3c). No cytokine production was observed in the absence of ImmTACs.

Fig. 3.

IMCgp100 elicits multiple effector functions. Experiments were performed using the approach shown in Fig. 2a. a and b DC-mediated activation of autologous polyclonal CD8+ (a) or CD4+ (b) T cell populations by IMCgp100 at concentrations between 10−13 and 10−8 M. A further sample prepared using LPS-matured DCs and ImmTAC-redirected T cells was measured concurrently. Data shown represent the average of three independent measurements ± SEM. Additional control experiments were carried out in the absence of IMCgp100, polyclonal T cells, DCs or apoptotic Mel624 cells, where necessary IMCgp100 was used at a fixed concentration of 1nM. c Poly-cytokine release from IMCgp100-redirected CD8+ T cells after incubation with DCs for 24 h. Intracellular accumulation of IFNγ, IL-2, TNF-α and MIP-1β, as well as the expression of lysosomal associated protein CD107a was detected by antibodies as described in the methods and analysed by Flow cytometry. Cells were first sorted by IFNγ production. A control measurement was made in the absence of IMCgp100

Cross-presented pHLA complexes can be directly visualised on individual DCs

To provide a direct assessment of antigen cross-presentation by DCs individual peptide-HLA (pHLA), complexes were observed on the DC cell surface. Quantification of pHLA complexes can be technically challenging, particularly when this involves detecting relatively low numbers of complexes. Furthermore, the vast majority of techniques only generate population average data. Here, we used a fluorescently labelled version of the same soluble T cell receptor (mTCR) used in IMCgp100 to visualise gp100-pHLA on the DC surface at the single cell level. This mTCR possesses extremely high affinity for gp100-HLA-A*02 complex (low picomolar range). Cross-presenting DCs were prepared by incubation with chemically induced apoptotic Mel624 cells. An mTCR with similarly high affinity for an alternative HLA-A*02 restricted peptide, not expressed by Mel624 cells, was used as a control. A low level of non-specific background was observed in the control sample. Representative images are illustrated in Fig. 4a with data for all cells shown graphically in Fig. 4b. Quantification of gp100-HLA complexes indicated that, on average, DCs presented a relatively low number of complexes, comparable to the level typically observed on tumour cells (10–50) [21, 24], while individual DCs present from zero to in excess of 100 copies of per cell (Fig. 4b). When the same experiment was repeated with HLA-A*0201− DCs, again HLA-A*02+ gp100 complexes were detected on the DC surface, suggesting that antigen cross-presentation was independent of HLA restriction in this system (Fig. 4c, d).

T cell activation in response to antigen cross-presentation is independent of DC HLA restriction

According to the classical view of cross-presentation, exogenous antigens are endocytosed and subsequently processed, re-routed to the site of HLA loading in the endoplasmic reticulum and trafficked to the cell surface [25]. In such a model, the DC HLA restriction is critical for antigen recognition. Since HLA-A*02+ gp100 complexes were detected on the surface of HLA-A*0201− DCs, the CD8+ T cell response to HLA-A*0201+ and HLA-A*0201− DCs was compared. Both IMCgp100-redirected polycloncal CD8+ T cells and Melan A T cells responded in a similar manner regardless of DC HLA restriction (Fig. 5a, b). To further confirm that T cell activation was independent of HLA restriction, T cell proliferation was monitored as an additional indicator of T cell activation, and again a similar result was observed (Fig. 5c, d). Given that neither IMCgp100-redirected polycloncal CD8+ T cells nor Melan-A-specific T cells responded to antigens presented by HLA-A*0201− cell lines (as shown for SK-Mel-28 in Fig. 1), these data suggest that gp100 and Melan A antigens were captured by DCs from membrane fragments of apoptotic Mel624 cells, in intact complexes with HLA-A*0201.

Fig. 5.

T cell activation by DCs cross-presenting gp100 and Melan A is independent of the DC HLA restriction. DCs previously exposed to chemically induced apoptotic Mel624 cells [denoted Mel624(ap)] were assessed for their ability to induce IFNγ release from IMCgp100-redirected autologous polyclonal CD8+ T cells and Melan-A-specific CD8+ T cells (as described in Fig. 2a). IMCgp100 was used at a concentration of 1 nM. In this case, experiments were carried out using both HLA-A*0201+ (a) and HLA-A*0201− cross-presenting DCs (b). Further samples were prepared using LPS-matured DCs (mDC) only and in the absence of DCs. Data shown represent the average of three independent measurements ± SEM. The proliferation of IMCgp100-redirected CD8+ T cells was measured in response to HLA-A*0201+ (c) and HLA-A*0201− (d) cross-presenting DCs by CFSE labelling. The percentage of cells undergoing proliferation is indicated

DC antigen uptake occurs via cross-dressing

To further examine the molecular mechanism of antigen uptake, HLA-A*0201+ DCs were exposed to each of the melanoma cell lines detailed in Fig. 1a after chemically induced apoptosis. The response of both IMCgp100-redirected polyclonal CD8+ T cells and Melan A-specific T cells to cross-presenting DCs was assessed. According to the classical model for cross-presentation, gp100 and Melan A antigens captured by HLA-A*0201+ DCs from apoptotic Mel624 and SK-Mel-28 cells should be processed and presented in the context of HLA-A*0201, irrespective of the HLA restriction of the melanoma cell. However, T cell activation was only observed with HLA-A*0201+ DCs that had been exposed to HLA-A*0201+ melanoma cell lines (Fig. 6). No T cell response was observed with SK-Mel-28 despite expression of gp100 and Melan A antigens, implying that HLA-A*0201+ DCs were unable to process and present these antigens, at sufficient levels to support T cell activation via their own HLA molecules. The rate of antigen uptake from Mel624 and SK-Mel-28 cells by DCs was similar (see supplementary Fig. 2). When SK-Mel-28 cells were induced to express HLA-A*0201, T cell activation was observed. The lower level of activation observed with HLA-A*0201 transfected SK-Mel-28 compared to Mel624 is most likely due to differences in the level of HLA molecules as discussed above (supplementary Fig. 1). Taken together, these data suggest that cross-presentation of gp100 and Melan A involves the direct transfer of intact pHLA-A*0201 complexes from the apoptotic melanoma cell to the DC surface.

Fig. 6.

Intact peptide-HLA complexes are acquired by DCs from apoptotic tumour cells. Immature HLA-A*0201+ DCs were exposed to chemically induced apoptotic melanoma cell lines, SK-Mel-28 (gp100+/Melan A+/HLA-A*0201−), SK-Mel-24 (gp100−/Melan A−/HLA-A*0201+), Mel624 (gp100+/Melan A+/HLA-A*0201+) or SK-Mel-28 cells transduced with HLA-A*0201 (SK-Mel-28 A2+). The resulting DCs were assessed for their ability to induce IFNγ release from IMCgp100-redirected CD8+ polyclonal T cells and Melan-A-specific CD8+ T cells. IMCgp100 was used at a concentration of 1 nM. A control measurement was made using LPS-matured DCs (mDC), in the absence of apoptotic Mel624 cells. Data shown represent the average of three independent measurements ± SEM

Discussion

ImmTACs, including IMCgp100, have been shown to drive targeted redirected T cell killing of tumour cells in vitro and in vivo [17, 18]. Using IMCgp100, we provide in vitro evidence that ImmTACs can induce and potentiate DC cross-presentation, which could contribute to the generation of a highly efficacious and durable ImmTAC-driven anti-tumour response in the clinic.

The critical processes involved in mounting an effective and durable immune response to cancer are (1) initial cancer killing, (2) DC activation and cross-presentation of TAAs, (3) DC priming of naive T cells in draining lymph nodes and (4) trafficking of activated T cells into the tumour microenvironment [26]. Tumour-infiltrating immune cells have been described, particularly in melanoma lesions and include CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, B cells, plasma cells, macrophages and dendritic cells [27]. However, as a consequence of central and peripheral tolerance mechanisms, tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are typically ineffective, having, at best, weak affinity (micomolar) for their cognate HLA-restricted tumour antigen. The engineered high-affinity recognition mediated by TAA-specific ImmTACs such as IMCgp100, combined with antibody-mediated recognition of CD3 complexes, enables ImmTACs to effectively recruit and activate CD3+ T cells, including ineffective TILs. Here, we provide evidence that ImmTAC-driven killing can induce and potentiate antigen cross-presentation, specifically by DCs, but also potentially other specialised antigen presenting cells, such as macrophages [28] which represent a higher proportion of the tumour-infiltrating immune cells in melanoma metastases compared to that of DCs [27] ). Of particular note is evidence that IMCgp100 is able to enhance the activation of Melan-A-specific T cells when exposed to cross-presenting DCs, in agreement with our previous observations of a similar effect on direct tumour cell killing [17]. This indicates that ImmTACs may play a role in breaking T cell tolerance by facilitating the full engagement of sub-optimal, partially activated TILs and peripheral T cells with tumour specific TCRs. Cross-presenting DCs may be effective at both the tumour site, where potent DC (or potentially macrophage) cross-presentation to TILs such as Melan A [29] may serve to relieve T cell anergy, and draining lymph nodes, where DCs cross-prime naïve [30] and central memory CD8+ T cells [31]. Cross-primed T cells are believed to acquire a specific homing phenotype that then enables them to preferentially recirculate back to the tumour site [32, 33]. In addition, the data demonstrate that ImmTAC recognition of cross-presented antigen can drive a broad immune response. This includes activation of both CD8+ and CD4+ T cell subsets, as well as secretion of various immune activating cytokines including IFNγ and TNF-α, which may serve to alleviate local tumour-induced suppression and promote further DC maturation (reviewed in [34, 35] ).

Despite evidence for the anti-tumour effects of DCs, it is worth bearing in mind that the mechanistic details of how DCs are able to mediate effective tumour regression remain to be fully defined. A further aspect to consider is the potential risk that cross-presenting DCs may themselves become targets for ImmTAC-redirected T cell killing. However, there is evidence to suggest that DCs may be resistant to apoptosis through the stimulation of CD40 (engagement of CD40 by its ligand, CD154, inhibits tumour-induced apoptosis in dendritic cells) and that some T cell subtypes, including central memory cells, protect DCs from dying, via secretion of TNF-α and promoting their maturation [36]. Furthermore, in an ongoing phase I trial using IMCgp100, there has been no indication of significant DC killing.

An additional aim of this work was to examine the cross-presentation process in more detail, first, by direct quantification of cross-presented antigen at the individual DC level. These investigations relied on the same technology that enables the production of high-affinity ImmTACs and provides extremely sensitive detection of peptide-HLA complexes on the cell surface. To our knowledge, we present here the first direct quantification of tumour-associated pHLA complexes cross-presented by DCs, made possible by the availability of engineered high-affinity monoclonal TCRs. Although the average number of pHLA complexes observed on individual DCs was similar to the number reportedly expressed on tumour cells [21, 24] (Mel624 cells express on average 34 gp100-HLA complexes per cell [24] ), the data reveal a large range in the number of cross-presented antigens on each DC, from none or very few, to in excess of 100. It is not clear whether this is a consequence of our experimental conditions, whether DC antigen uptake is mediated by a limited number of DCs within a population or whether a positive feedback mechanism promotes uptake of further antigens. Presumably, only those DCs which present a threshold number of antigens are able to effectively activate T cells.

The second approach was to investigate the mechanism of antigen acquisition by DCs. The classical route is via phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and/or endocytosis of released antigens, but antigens can also be acquired through ‘nibbling’ of live cells [37, 38], and, more recently, evidence has been reported for antigen transfer via direct cell contact mediated by gap junctions [39]. In our experiments, T cell recognition of cross-presented antigens was dependent upon the HLA restriction of the tumour cell from which the antigen was obtained, but not the HLA restriction of the DC. This suggests that entire pHLA complexes are transferred directly to DCs, presumably via ‘trogocytosis’ [40]. Such a transfer mechanism has been reported in the literature and has been termed ‘cross-dressing’ [41, 42]. Since no intracellular processing is required, cross-dressing is likely to be a rapid way of presenting antigens to T cells. Wakim and Bevan recently showed that cross-dressed DCs activate the memory T cell population in particular [42]. Therefore, it seems likely that ImmTAC-driven cross-presentation may exploit the capacity of DCs to cross-dress for an immediate amplification of the immune response, possibly in the order of hours. Such rapid cross-presentation has been observed previously with both DCs and marcophages [28]. Cross-dressing is also proposed to activate DCs that have not been efficiently activated by cross-priming [41], although this may depend on the specific DC subset [43].

Although we still do not have a complete understanding of the intricacies of DC involvement in the anti-tumour response, the evidence for ImmTAC-driven cross-presentation gives a strong indication of the potential of these reagents to orchestrate a broad, efficacious and self-sustaining anti-tumour immune response in vivo.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by Immunocore Ltd.

Conflict of interest

All authors are employees of Immunocore Ltd. Soluble monoclonal TCRs and ImmTACs, including IMCgp100, were produced by Immunocore Ltd.

References

- 1.Borghesi L, Milcarek C. Innate versus adaptive immunity: a paradigm past its prime? Cancer Res. 2007;67(9):3989–3993. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ikeda H, Chamoto K, Tsuji T, Suzuki Y, Wakita D, Takeshima T, Nishimura T. The critical role of type-1 innate and acquired immunity in tumor immunotherapy. Cancer Sci. 2004;95(9):697–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Celluzzi CM, Mayordomo JI, Storkus WJ, Lotze MT, Falo LD., Jr Peptide-pulsed dendritic cells induce antigen-specific CTL-mediated protective tumor immunity. J Exp Med. 1996;183(1):283–287. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackensen A, Meidenbauer N, Vogl S, Laumer M, Berger J, Andreesen R. Phase I study of adoptive T-cell therapy using antigen-specific CD8+ T cells for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(31):5060–5069. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spel L, Boelens J, Nierkens S, Boes M. Antitumor immune responses mediated by dendritic cells: how signals derived from dying cancer cells drive antigen cross-presentation. OncoImmunology. 2013;2:e26403. doi: 10.4161/onci.26403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuertes MB, Kacha AK, Kline J, Woo SR, Kranz DM, Murphy KM, Gajewski TF. Host type I IFN signals are required for antitumor CD8+ T cell responses through CD8α+ dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208(10):2005–2016. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hildner K, Edelson BT, Purtha WE, Diamond M, Matsushita H, Kohyama M, Calderon B, Schraml BU, Unanue ER, Diamond MS, Schreiber RD, Murphy TL, Murphy KM. Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8α+ dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science. 2008;322(5904):1097–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1164206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung S, Unutmaz D, Wong P, Sano G, De los Santos K, Sparwasser T, Wu S, Vuthoori S, Ko K, Zavala F, Pamer EG, Littman DR, Lang RA. In vivo depletion of CD11c+ dendritic cells abrogates priming of CD8+ T cells by exogenous cell-associated antigens. Immunity. 2002;17(2):211–220. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00365-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalos M. Muscle CARs and TcRs: turbo-charged technologies for the (T cell) masses. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61(1):127–135. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1173-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aleksic M, Liddy N, Molloy PE, Pumphrey N, Vuidepot A, Chang KM, Jakobsen BK. Different affinity windows for virus and cancer-specific T-cell receptors: implications for therapeutic strategies. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42(12):3174–3179. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bridgeman JS, Sewell AK, Miles JJ, Price DA, Cole DK. Structural and biophysical determinants of αβ T-cell antigen recognition. Immunology. 2012;135(1):9–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03515.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole DK, Pumphrey NJ, Boulter JM, Sami M, Bell JI, Gostick E, Price DA, Gao GF, Sewell AK, Jakobsen BK. Human TCR-binding affinity is governed by MHC class restriction. J Immunol. 2007;178(9):5727–5734. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robbins PF, Li YF, El-Gamil M, Zhao Y, Wargo JA, Zheng Z, Xu H, Morgan RA, Feldman SA, Johnson LA, Bennett AD, Dunn SM, Mahon TM, Jakobsen BK, Rosenberg SA. Single and dual amino acid substitutions in TCR CDRs can enhance antigen-specific T cell functions. J Immunol. 2008;180(9):6116–6131. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chlewicki LK, Holler PD, Monti BC, Clutter MR, Kranz DM. High-affinity, peptide-specific T cell receptors can be generated by mutations in CDR1, CDR2 or CDR3. J Mol Biol. 2005;346(1):223–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, Moysey R, Molloy PE, Vuidepot AL, Mahon T, Baston E, Dunn S, Liddy N, Jacob J, Jakobsen BK, Boulter JM. Directed evolution of human T-cell receptors with picomolar affinities by phage display. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(3):349–354. doi: 10.1038/nbt1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boulter JM, Glick M, Todorov PT, Baston E, Sami M, Rizkallah P, Jakobsen BK. Stable, soluble T-cell receptor molecules for crystallization and therapeutics. Protein Eng. 2003;16(9):707–711. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzg087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liddy N, Bossi G, Adams KJ, Lissina A, Mahon TM, Hassan NJ, Gavarret J, Bianchi FC, Pumphrey NJ, Ladell K, Gostick E, Sewell AK, Lissin NM, Harwood NE, Molloy PE, Li Y, Cameron BJ, Sami M, Baston EE, Todorov PT, Paston SJ, Dennis RE, Harper JV, Dunn SM, Ashfield R, Johnson A, McGrath Y, Plesa G, June CH, Kalos M, Price DA, Vuidepot A, Williams DD, Sutton DH, Jakobsen BK. Monoclonal TCR-redirected tumor cell killing. Nat Med. 2012;18:980–987. doi: 10.1038/nm.2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCormack E, Adams KJ, Hassan NJ, Kotian A, Lissin NM, Sami M, Mujic M, Osdal T, Gjertsen BT, Baker D, Powlesland AS, Aleksic M, Vuidepot A, Morteau O, Sutton DH, June CH, Kalos M, Ashfield R, Jakobsen BK. Bi-specific TCR-anti CD3 redirected T-cell targeting of NY-ESO-1- and LAGE-1-positive tumors. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62(4):773–785. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adema GJ, de Boer AJ, van’t Hullenaar R, Denijn M, Ruiter DJ, Vogel AM, Figdor CG. Melanocyte lineage-specific antigens recognized by monoclonal antibodies NKI-beteb, HMB-50, and HMB-45 are encoded by a single cDNA. Am J Pathol. 1993;143(6):1579–1585. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cole DK, Yuan F, Rizkallah PJ, Miles JJ, Gostick E, Price DA, Gao GF, Jakobsen BK, Sewell AK. Germ line-governed recognition of a cancer epitope by an immunodominant human T-cell receptor. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(40):27281–27289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.022509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Purbhoo MA, Sutton DH, Brewer JE, Mullings RE, Hill ME, Mahon TM, Karbach J, Jager E, Cameron BJ, Lissin N, Vyas P, Chen JL, Cerundolo V, Jakobsen BK. Quantifying and imaging NY-ESO-1/LAGE-1-derived epitopes on tumor cells using high affinity T cell receptors. J Immunol. 2006;176(12):7308–7316. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dull T, Zufferey R, Kelly M, Mandel RJ, Nguyen M, Trono D, Naldini L. A third-generation lentivirus vector with a conditional packaging system. J Virol. 1998;72(11):8463–8471. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8463-8471.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Euw EM, Barrio MM, Furman D, Bianchini M, Levy EM, Yee C, Li Y, Wainstok R, Mordoh J. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells loaded with a mixture of apoptotic/necrotic melanoma cells efficiently cross-present gp100 and MART-1 antigens to specific CD8(+) T lymphocytes. J Transl Med. 2007;5:19. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bossi G, Gerry AB, Paston SJ, Sutton DH, Hassan NJ, Jakobsen BK. Examining the presentation of tumor-associated antigens on peptide-pulsed T2 cells. OncoImmunology. 2013;2:e26840. doi: 10.4161/onci.26840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen L, Rock KL. Priming of T cells by exogenous antigen cross-presented on MHC class I molecules. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18(1):85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gajewski TF, Woo SR, Zha Y, Spaapen R, Zheng Y, Corrales L, Spranger S. Cancer immunotherapy strategies based on overcoming barriers within the tumor microenvironment. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25(2):268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erdag G, Schaefer JT, Smolkin ME, Deacon DH, Shea SM, Dengel LT, Patterson JW, Slingluff CL., Jr Immunotype and immunohistologic characteristics of tumor-infiltrating immune cells are associated with clinical outcome in metastatic melanoma. Cancer Res. 2012;72(5):1070–1080. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barrio MM, Abes R, Colombo M, Pizzurro G, Boix C, Roberti MP, Gelize E, Rodriguez-Zubieta M, Mordoh J, Teillaud JL. Human macrophages and dendritic cells can equally present MART-1 antigen to CD8(+) T cells after phagocytosis of gamma-irradiated melanoma cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e40311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mandruzzato S, Rossi E, Bernardi F, Tosello V, Macino B, Basso G, Chiarion-Sileni V, Rossi CR, Montesco C, Zanovello P. Large and dissimilar repertoire of Melan-A/MART-1-specific CTL in metastatic lesions and blood of a melanoma patient. J Immunol. 2002;169(7):4017–4024. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berard F, Blanco P, Davoust J, Neidhart-Berard EM, Nouri-Shirazi M, Taquet N, Rimoldi D, Cerottini JC, Banchereau J, Palucka AK. Cross-priming of naive CD8 T cells against melanoma antigens using dendritic cells loaded with killed allogeneic melanoma cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192(11):1535–1544. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Mierlo GJ, Boonman ZF, Dumortier HM, den Boer AT, Fransen MF, Nouta J, van der Voort EI, Offringa R, Toes RE, Melief CJ. Activation of dendritic cells that cross-present tumor-derived antigen licenses CD8+ CTL to cause tumor eradication. J Immunol. 2004;173(11):6753–6759. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dudda JC, Simon JC, Martin S. Dendritic cell immunization route determines CD8+ T cell trafficking to inflamed skin: role for tissue microenvironment and dendritic cells in establishment of T cell-homing subsets. J Immunol. 2004;172(2):857–863. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calzascia T, Masson F, Di Berardino-Besson W, Contassot E, Wilmotte R, Aurrand-Lions M, Ruegg C, Dietrich PY, Walker PR. Homing phenotypes of tumor-specific CD8 T cells are predetermined at the tumor site by cross presenting APCs. Immunity. 2005;22(2):175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDonnell AM, Robinson BW, Currie AJ. Tumor antigen cross-presentation and the dendritic cell: where it all begins? Clin Dev Immunol. 2010;2010:539519. doi: 10.1155/2010/539519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pinzon-Charry A, Maxwell T, Lopez JA. Dendritic cell dysfunction in cancer: a mechanism for immunosuppression. Immunol Cell Biol. 2005;83(5):451–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watchmaker PB, Urban JA, Berk E, Nakamura Y, Mailliard RB, Watkins SC, van Ham SM, Kalinski P. Memory CD8+ T cells protect dendritic cells from CTL killing. J Immunol. 2008;180(6):3857–3865. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harshyne LA, Watkins SC, Gambotto A, Barratt-Boyes SM. Dendritic cells acquire antigens from live cells for cross-presentation to CTL. J Immunol. 2001;166(6):3717–3723. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harshyne LA, Zimmer MI, Watkins SC, Barratt-Boyes SM. A role for class A scavenger receptor in dendritic cell nibbling from live cells. J Immunol. 2003;170(5):2302–2309. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saccheri F, Pozzi C, Avogadri F, Barozzi S, Faretta M, Fusi P, Rescigno M. Bacteria-induced gap junctions in tumors favor antigen cross-presentation and antitumor immunity. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(44):44ra57. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Joly E, Hudrisier D. What is trogocytosis and what is its purpose? Nat Immunol. 2003;4(9):815. doi: 10.1038/ni0903-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dolan BP, Gibbs KD, Jr, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Dendritic cells cross-dressed with peptide MHC class I complexes prime CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177(9):6018–6024. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wakim LM, Bevan MJ. Cross-dressed dendritic cells drive memory CD8+ T-cell activation after viral infection. Nature. 2011;471(7340):629–632. doi: 10.1038/nature09863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smyth LA, Harker N, Turnbull W, El-Doueik H, Klavinskis L, Kioussis D, Lombardi G, Lechler R. The relative efficiency of acquisition of MHC: peptide complexes and cross-presentation depends on dendritic cell type. J Immunol. 2008;181(5):3212–3220. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.