Abstract

Neuroblastoma, a childhood tumour of neuroectodermal origin, accounts for 15 % of paediatric cancer deaths, which is often metastatic at diagnosis and despite aggressive therapies, it has poor long-term prognosis with high risk of recurrence. Monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy targeting GD2, a disialoganglioside expressed on neuroblastoma, has shown promise in recent trials with natural killer cell (NK)-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) thought to be central to efficacy, although other immune effectors may be important. To further enhance therapy, immunomonitoring of patients is essential to elucidate the in vivo mechanisms of action and provides surrogate end points of efficacy for future clinical trials. Our aim was to establish a ‘real-time’ ex vivo whole-blood (WB) immunomonitoring strategy to perform within the logistical constraints such as limited sample volumes, anticoagulant effects, sample stability and shipping time. A fluorescent dye release assay measuring target cell lysis was coupled with flow cytometry to monitor specific effector response. Significant target cell lysis with anti-GD2 antibody (p < 0.05) was abrogated following NK depletion. NK up-regulation of CD107a and CD69 positively correlated with target cell lysis (r > 0.6). The ADCC activity of WB correlated with peripheral blood mononuclear cells (r > 0.95), although WB showed overall greater target cell lysis attributed to the combination of NK-mediated ADCC, CD16+ granulocyte degranulation and complement-dependent cytotoxicity. Response was maintained in heparinised samples stored for 24 h at room temperature, but not 4 °C. Critically, the assay showed good reproducibility (mean % CV < 6.4) and was successfully applied to primary neuroblastoma samples. As such, WB provides a resourceful analysis of multiple mechanisms for efficient end point monitoring to correlate immune modulation with clinical outcome.

Keywords: Immunotherapy, Immunomonitoring, Neuroblastoma, ADCC, NK cells

Introduction

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) directed against tumour cells bind to their specific target antigen via their F(ab) regions, allowing the Fc portion to engage immune effector systems such as complement or Fc receptor (FcR)-bearing cells such as natural killer (NK) cells that express the activatory Fc gamma receptor (FcγR) IIIa (CD16A) [1]. This Fc–FcγR interaction can trigger the release of cytolytic vesicles from the effector cells, whose contents can mediate direct apoptotic cell death of the targets. It is this mechanism, known as antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) that is thought to be primarily involved in the therapy elicited by the anti-GD2 mAb, used to treat neuroblastoma and provides an ideal working model for assay development and for extending our understanding of passive targeted antibody immunotherapy [2].

Neuroblastoma is one of the most common extracranial solid tumours of children and accounts for 15 % of paediatric cancer deaths [3]. It is frequently metastatic or ‘high risk’ at diagnosis, resulting in poor long-term survival (5-year EFS < 50 %) despite an exhaustive, highly toxic, combination of conventional therapies including intensive chemotherapy, surgery, radiotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue and finally treatment with 13-cis retinoic acid [4]. Neuroblastoma cells, derived from neuroectodermal origin, ubiquitously express the GD2 disialoganglioside abundantly on their surface, whereas other neuroectodermal tissues such as peripheral nerves have more limited expression [5]. For this reason, GD2 has become a promising target for mAb immunotherapy in these patients. In 2010, the US Children’s Oncology Group (COG) reported a large randomised trial, demonstrating survival benefit (66 vs. 46 % 2 year EFS) in high-risk neuroblastoma patients who in addition to the above standard therapy received an anti-GD2 chimeric mAb combined with the cytokines GM-CSF and IL-2 [6]. However, the study design was such that it was not possible to ascertain the role played by each component of the treatment. Furthermore, anti-GD2 therapy causes considerable toxicity and pain, and not all children are cured with a large proportion still relapsing and dying from their disease. Improving the efficacy of anti-GD2 therapy by enhancing the mechanisms by which the antibody interacts with the immune system to kill neuroblastoma cells combined with the ability to identify responders and non-responders is a key way in which the clinical outcome for these children may be improved.

Although ADCC is proposed as one important process involved in targeted mAb therapy [7], a more detailed and definitive understanding of immune effector mechanisms through immunomonitoring of patients is essential to improve and enhance therapies [8]. Current ADCC methodology requires large numbers of effector cells but only small blood volumes are available from paediatric patients, leaving little room for detailed immunological assays. In addition, real-time analysis of fresh samples is required, which is challenging when relatively small numbers of patients are treated at multiple geographically disparate sites. It is therefore of particular importance to develop robust immunological assays using minimal blood volumes, to allow multiple time-point sampling for detailed monitoring during the course of therapy. Furthermore, it is essential to ensure the stability of such assays during typical transit times.

To address this need, we have developed a method to monitor the anti-GD2 effector mechanisms using peripheral whole-blood samples and compared this to current methodology using PBMC and serum to monitor ADCC and CDC responses, respectively [9]. By using this fluorescent dye method as opposed to radioactive labelling of the target cells [10], we have been able to combine flow cytometry to simultaneously analyse key effector populations, CD56+ NK cells, CD16+ granulocytes and CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL), to correlate cell-specific activity with target cell lysis. As part of establishing a WB small-volume sample monitoring strategy, we also address logistical issues facing multisite studies including the time and temperature of sample storage and the effect of anticoagulant on the functional stability. Sample handling is often a barrier for functional assays due to the transit turnaround time, especially where multisite studies are the only possible route to recruiting sufficient paediatric numbers. Our technique provides an alternative approach allowing direct unmanipulated immunomonitoring at the cellular level and is an efficient and practical means to measure specific effector cell responses for correlation to clinical outcome. Moreover, we have shown the practical applicability of this approach with a neuroblastoma case study before and during anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody immunotherapy.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

Eagle’s minimal essential medium (EMEM) (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) and Ham’s F12 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK) were supplemented with 10 % foetal calf serum (FCS) (Lonza, UK), 2 mM glutamine (Invitrogen) and 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids (NEAA) (Invitrogen) and used for culturing Lan-1 cells. The GD2-positive human neuroblastoma cell lines Lan-1 (European Collection of Cell Cultures, ECACC, Salisbury, UK) were cultured in a 50:50 mix of supplemented EMEM and Hams F12 media at 37 °C, 10 % CO2 and used at 80 % confluence. The ADCC assays were performed using RPMI medium supplemented with 10 % FCS, 2 mM glutamine and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen). The anti-GD2 antibody, 14G2a, was produced from a secreting hybridoma kindly provided by Prof Holger Lode (Greifswald, Germany). The anti-GD2 antibody, 14.18m2a, and the anti-CD20 antibody, ritm2a [11], were produced in-house, using patented published sequences and antibody-secreting hybridomas. The chimeric anti-GD2 antibody, ch14.18/CHO mAb, was kindly provided by Apeiron Biologics (Vienna, Austria).

Samples

Fully anonymised Trima leucocyte reduction system (LRS) cones from healthy adult subjects were obtained from the National Blood Transfusion Service, Southampton, UK. Anticoagulated whole-blood samples were collected from healthy donors in sodium heparin or ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) vacutainer tubes. Samples were collected following informed consent and used under ethical approval (National Research Ethics Service, UK) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. PBMC from either LRS cones (diluted 1:2 with RPMI media) or from anticoagulated whole blood were isolated using Lymphoprep© (Axis-Shield, UK). LRS cones, diluted 1:2, were used as a surrogate source of ‘ex vivo’ whole blood, to optimise the methodology, before applying to anticoagulated whole-blood samples.

ADCC assay

Lan-1 cells were labelled with the membrane permeable molecule, calcein acetoxymethyl ester (calcein-AM) (Sigma-Aldrich) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Calcein-AM passively diffuses across the target cell membrane into the cell cytoplasm where hydrolysis by intracellular esterases converts it to a fluorescent dye, calcein. Calcein is unable to diffuse back across the membrane and is retained in the cytoplasm until cell lysis occurs. The amount of calcein released is proportional to the level of cell lysis. Labelled Lan-1 target cells were seeded at 5 × 103 cells in 50 μl RPMI media/well in a 96-well plate. About 50 μl of antibody at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml was added to opsonise the target cells, and the plates were incubated for 30 min in the dark at 37 °C, 5 % CO2. Effectors, either PBMC or whole blood, were added in 100 μl volumes at varying concentrations to give the required effector/target ratio as detailed in the results section. To the wells without antibody, or effectors, RPMI media was added to ensure all wells had a final 200 μl volume. For maximum lysis, 100 μl of lysis buffer (4 % Triton X-100 (Sigma) in RPMI media) was added. All conditions were plated in triplicate. The plates were centrifuged at 100g for 1 min and then incubated in the dark at 37 °C, 5 % CO2 for 4 h. Plates were centrifuged at 200g for 3 min, and 75 μl of supernatant from each well was transferred to a 96-well white-walled plate and fluorescence measured using the Varioskan Flash plate reader (Thermoscientific, UK).

The percentage target cell lysis was calculated as:

where RFU = relative fluorescence units.

For antibody-independent cellular cytotoxicity (AICC), test RFU = targets + effectors.

For ADCC, test RFU = targets + antibody + effectors.

Flow cytometry

The following antibodies from BD Biosciences (Oxford, UK) were used for flow cytometry: anti-CD107a V450, anti-CD56 phycoerythrin (PE), anti-CD8 allophycocyanin-Cy7 (APC-Cy7) and anti-CD69 allophycocyanin (APC). For experiments combining flow cytometry with the ADCC assay, anti-CD107a V450 antibody was added to the wells of the ADCC assay at the start of the 4-h incubation period. Following the removal of supernatant, the cells remaining in the wells were transferred to Facs tubes, kept on ice and labelled with anti-CD56 PE, anti-CD8 PE Cy7 and CD69 APC. Cells were incubated for 1 h in the dark at 4 °C. For whole-blood samples, red blood cell lysis was performed using BD lysis buffer according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The cells were washed three times in Facs buffer and analysed immediately on a Facs Canto II flow cytometer using FacsDiva software (BD Bioscience). CD69 and CD107a expression was determined as the percentage positive within either the CD56+ NK or CD8+ CTL populations.

Case study

Analysis was performed on samples from a high-risk neuroblastoma patient treated with anti-GD2 antibody following informed consent under ethical approval from the UK National Research Ethics Service. The patient received five cycles of anti-GD2 (ch14.18) therapy, delivered as 5 × 8 h infusions, on five consecutive days of each 28 day cycle. EDTA, heparinised or clotted blood samples were taken prior to infusion of the ch14.18 mAb therapy (baseline) and on Day 4 of treatment.

The ADCC and flow cytometry assay were performed as above. CDC was also assessed by adding 100 μl of serum diluted 1:2 in place of the effector cells. Heat-inactivated serum (56 °C for 30 min) was used to determine background RFU values.

Statistical analysis

Differences between AICC and ADCC were assessed for statistical significance using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test. Differences were considered significant when p < 0.05. (In the figures, *0.01 < p < 0.05; **0.001 < p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; non-significant (ns) p > 0.05) The nonparametric Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r) was used to determine correlation with r > 0.5 considered as a positive correlation. Error bars show standard error of the mean. Variation was calculated using the coefficient of variance (CV) expressed as a percentage.

Results

Specificity and Sensitivity

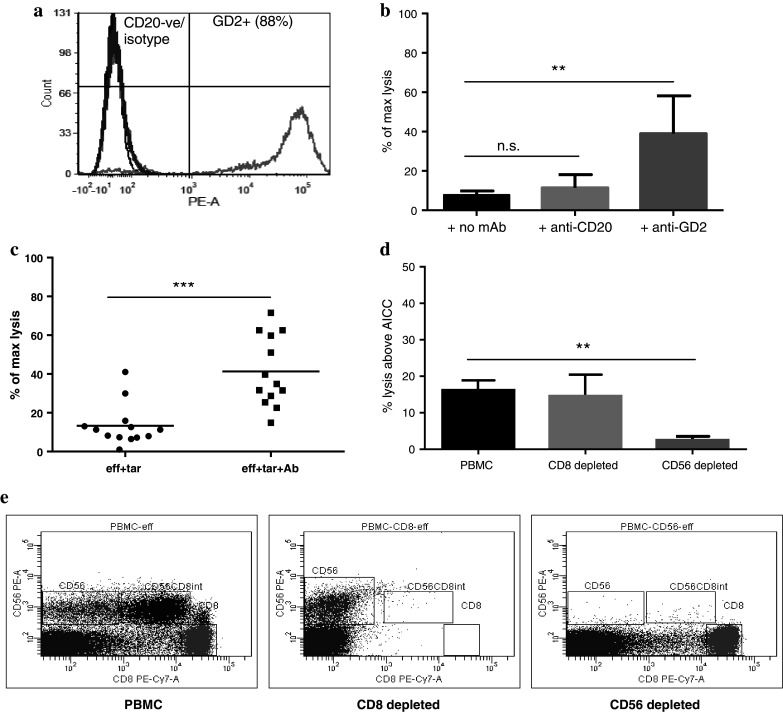

GD2 expression on the human neuroblastoma cell line, Lan-1, was confirmed by flow cytometry (Fig. 1a). Lan-1 was negative for CD20 expression, allowing anti-CD20 antibody to be used as a negative control. Specificity of the ADCC response was assessed using PBMC samples from five healthy donor LRS cones with Lan-1 target cells pre-incubated with anti-GD2 antibody (14.18m2a) or anti-CD20 antibody (Ritm2a), with antibody-independent cell cytotoxicity (AICC) being assessed in the absence of antibody. There was significant ADCC target cell lysis above AICC, when the targets were pre-incubated with 14.18m2a antibody (p = 0.008), but negligible cell lysis with ritm2a (Fig. 1b), confirming that the response was antibody-target-specific. To determine the sensitivity and inter-donor variability of the assay, PBMC samples from 20 healthy donor LRS cones were incubated with Lan-1 target cells ± 14.18m2a (Fig. 1c). There was some inter-donor variability of the AICC response but all individuals produced a subsequent increase in cell lysis in the presence of anti-GD2 antibody demonstrating the assay’s sensitivity to assess donor-variable ADCC responses. There is a trend for samples with a higher AICC to also have a higher corresponding ADCC, with the overall ADCC response being significantly greater than the AICC response (p < 0.0005). To confirm that the ADCC cell lysis was specifically NK cell-mediated, the effect of either CD8+ or CD56+ cell depletion was assessed. Total CD56+ NK cell depletion resulted in almost complete abrogation of the ADCC response confirming their role in ADCC-mediated cell lysis (Fig. 1d). Depleting CD8+ cells resulted in a partial but non-significant reduction in ADCC response, which we attributed to the loss of the CD56+ CD8+ subset of NK cells rather than the loss of CD8+ CTL (Fig. 1e).

Fig. 1.

a Histograms show the typical level of GD2 and CD20 expression on the surface of Lan-1 cells. b The graph shows the level of target cell lysis as a percentage of maximum lysis using PBMC from 5 healthy donor LRS cones incubated with Lan-1 target cells ± antibody (mAb). There is significant lysis with the anti-GD2 antibody, 14.18m2a, compared to the anti-CD20 antibody, rtxm2a. c The range of response using PBMC from 20 healthy donor LRS cones with Lan-1 target cells ± anti-GD2 antibody is shown and demonstrates that the assay can distinguish the variable ADCC responses between individuals. d The ADCC response from 5 individuals following CD8 and CD56 depletion was compared to that of the non-depleted PBMC. CD8 depletion showed no change in response; however, CD56 depletion resulted in a significant loss in ADCC response. e Cell depletion was assessed using flow cytometry and shows two distinct CD56 populations (CD8+ and CD8−). CD8 depletion results in the loss of CD56+ CD8+ cells, with the CD56+ CD8 cells remaining to respond. CD56 depletion results in the loss of both CD56+ subsets, with the CD8+ T cells remaining, which do not cause target cell lysis, confirming the ADCC response is specific to NK cells (*0.01 < p < 0.05; **0.001 < p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns non-significant p > 0.05)

Combined flow cytometry

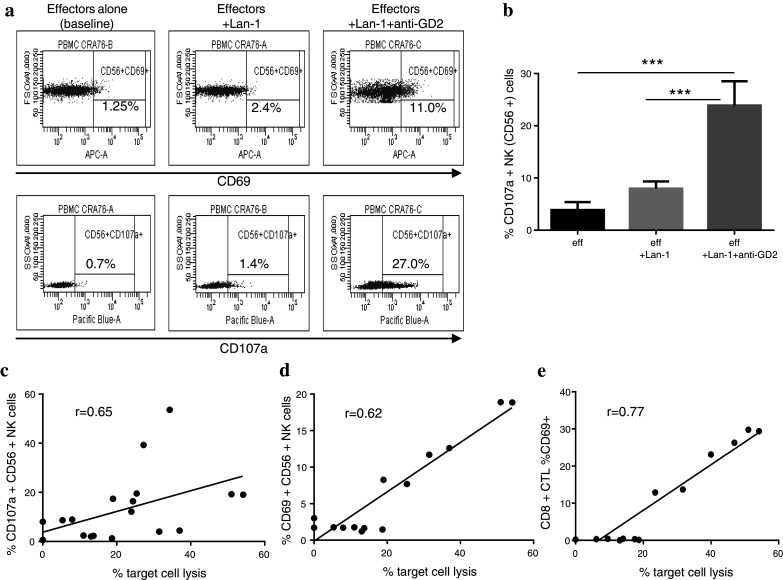

CD56+ NK cells and CD8+ CTL recovered from the ADCC assay were also analysed for changes in activation status. The cells were labelled with fluorescently conjugated antibodies against CD56, CD8, CD69 and CD107a. CD69 expression was used as an early activation marker and CD107a as a marker of degranulation (Fig. 2a). Baseline expression was determined using ‘effectors alone’. CD107a was significantly (p < 0.0001) up-regulated on CD56+ NK cells with anti-GD2 opsonised Lan-1 target cells (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, there was a small increase in CD69 and CD107a expression even in the absence of antibody. There was a strong positive correlation between the level of target cell lysis and NK cell expression of CD107a (r = 0.65; Fig. 2c) and CD69 (r = 0.62; Fig. 2d) confirming the relationship between NK activation with target cell lysis. Interestingly, although with low-level ADCC activity there was no apparent CD69 or CD107a expression on CD8+ CTL, there was an up-regulation of CD69 on these cells with increasing ADCC response (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2.

a Representative dot plot showing the shift in CD107a and CD69 on CD56+ NK cells following incubation with Lan-1 target cells and anti-GD2 antibody. b CD107a was significantly up-regulated on CD56+ NK cells recovered from the condition eff+ Lan-1+ anti-GD2 antibody compared to eff or eff+ Lan-1 (n = 10). Expression of CD107a (c) and CD69 (d) on CD56+ NK cells showed a positive correlation with % target cell lysis (r = Spearman’s correlation coefficient). e There was also a good correlation between the up-regulation of CD69 on CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) with increasing level of cell lysis. (***p < 0.001)

Reproducibility using whole blood compared to peripheral blood mononuclear cells

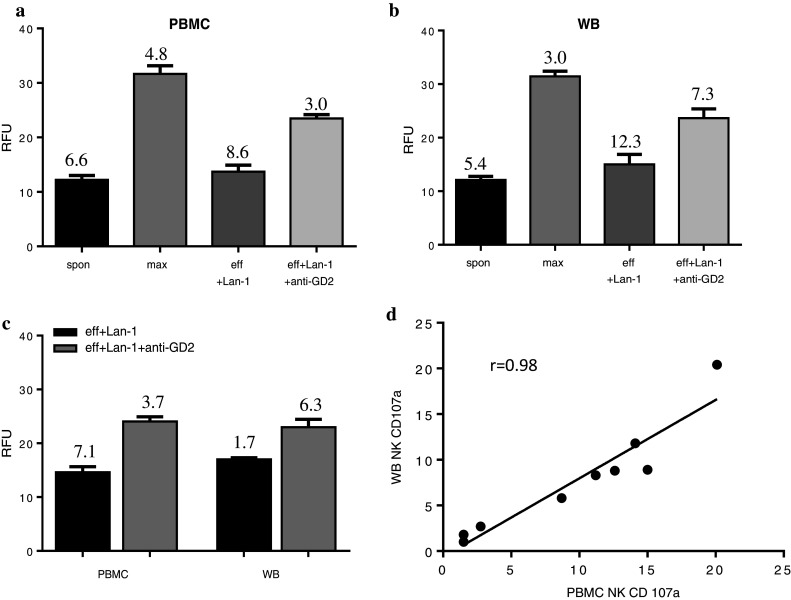

The assay was assessed for reproducibility using matched PBMC and unprocessed ‘whole blood’ from LRS cones with Lan-1 target cells ± anti-GD2 antibody. Intra- and inter-assay variability was assessed for both PBMC and whole blood. There was low intra-assay variability for PBMC (Fig. 3a) and whole blood (Fig. 3b) with a mean coefficient of variance (CV) <6.4 % assessed with 24 replicate wells for each condition The inter-assay variability was also low with a mean CV <4.7 % assessed using three replicate runs of the same sample on three separate plates demonstrating good reproducibility (Fig. 3c). These results also demonstrated high comparability between the unprocessed surrogate ‘whole-blood’ samples and PBMC responses (r > 0.7). Furthermore, PBMC and ‘whole blood’ had the equivalent increase in CD107a expression on CD56+ NK cells following incubation with anti-GD2 opsonised Lan-1 cells (Fig. 3d), indicating that whole blood is a viable alternative to PBMC for monitoring ADCC responses.

Fig. 3.

Graphs show the mean relative fluorescence units (RFU) measured in 24 replicate wells for each condition using either whole blood (wb) (a) or matched PBMC (b). Intra-assay variation was low with all replicates having a mean coefficient of variance (CV) < 6.4 % (actual % CV values shown on graphs). c The graph shows the mean RFU from three repeat runs using the same wb and matched PBMC. The inter-assay variation was assessed as having a mean CV < 4.7 %. The ADCC response showed good correlation between matched wb and PBMC samples for all three ADCC graphs (r > 0.7). d CD107a expression on CD56+ NK cells showed good correlation between wb and matched PBMC. (Correlation was assessed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient where r > 0.5 was considered as a good positive correlation)

Heparinised versus EDTA

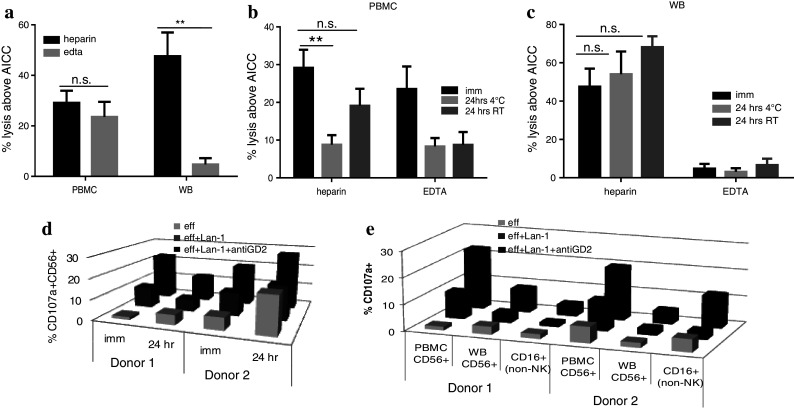

Having developed and validated the methodology using LRS cones, we subsequently assessed whole-blood samples from healthy donors to optimise logistics for sample collection. Blood samples collected in either heparin or EDTA vacutainer tubes were analysed either immediately or at 24-h post-draw, stored at RT or at 4 °C. There was no difference in the ADCC response using PBMC from either heparin or EDTA samples. However, using whole blood, there was a significant loss of response with EDTA but not with heparinised samples (Fig. 4a). Looking at stability, PBMC isolated from EDTA blood lost their initial ability to produce an ADCC response after 24-h storage at both 4 °C and RT, whilst PBMC from heparinised samples were still able to mount a response if kept at RT but not at 4 °C (Fig. 4b). Heparinised whole blood was still able to produce an ADCC response when kept at both RT and 4 °C, with EDTA-isolated whole blood still proving unresponsive (Fig. 4c). These results indicate heparinised samples stored for up to 24 h at RT are suitable for monitoring ADCC responses.

Fig. 4.

a The graph shows the ADCC response using heparin and EDTA samples used as whole blood (WB) or processed for use as PBMC. The ADCC response in WB is significantly reduced when samples are collected in EDTA with only a small, non-significant reduction using PBMC from EDTA samples (n = 3). b PBMC from heparinised samples were still able to mount a response if kept at room temperature (RT) but not at 4 °C, whilst PBMC from EDTA blood lost their initial ability to respond after 24-h storage at both 4 °C and RT. c For whole blood, heparinised samples retained their ADCC responsiveness at 24 h both at 4 °C and RT storage, with EDTA samples remaining unresponsive. d The percentage of CD107a+ NK cells was assessed on cells recovered from the ADCC assays (data shown for two healthy donors D1 and D2). After 24 h, CD107a up-regulation was still measurable in line with the ADCC response. e The % CD107a+ CD56+ NK cells were higher in the PBMC assays than WB assays. However, the CD16+ (non-NK cells) present in the whole-blood assays also showed up-regulation of CD107a with Lan-1+ anti-GD2 antibody. (**0.001 < p < 0.01; ns non-significant; p > 0.05)

From these results, it is clear that when performing an ADCC functional assay, whole blood or PBMC collected in heparinised tubes is preferable to EDTA samples and ideally should be analysed on the day of draw with storage at ambient temperature as opposed to 4 °C. However, for multisite studies, a 24-h shipping time at ambient temperature prior to analysis would still be acceptable to determine ADCC activity.

The up-regulation of CD107a on CD56+ NK cells from the recovered PBMC effectors was comparable between immediate and 24-h heparinised samples at RT (Fig. 4d). However, this up-regulation was not evident in samples at 4 °C or in EDTA samples. This confirms that the loss of ADCC response is due to the loss of cell function and not loss of the necessary cell population. Interestingly, heparinised whole blood revealed an unexpected lower % increase in CD107a+ CD56+ NK cells. On further analysis, it was evident that CD16+ non-NK granulocytic cells present in unmanipulated blood had also up-regulated CD107a, suggesting that this population was contributing to the ADCC effect (Fig. 4e).

Case study

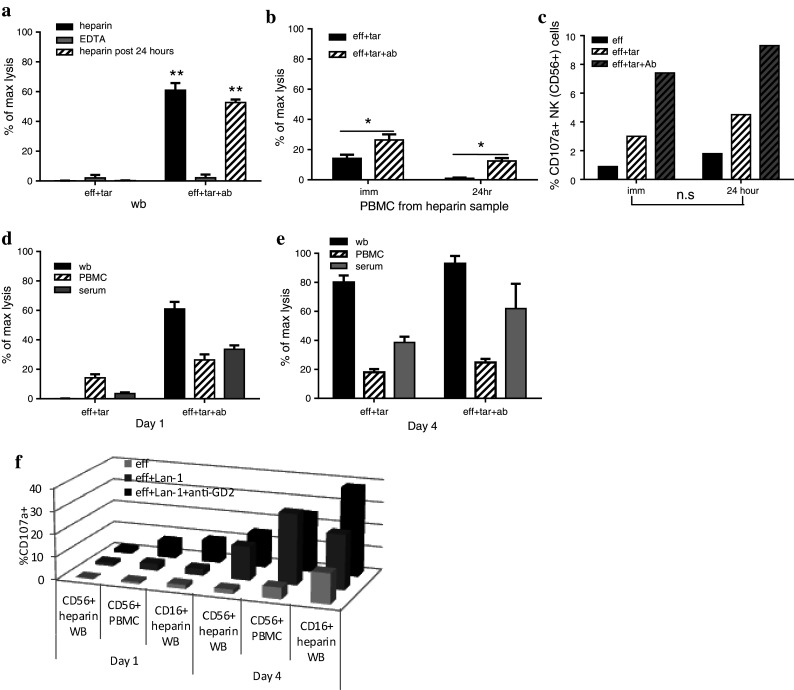

The anticoagulant effect (EDTA and heparin) and sample stability were next assessed using samples from a high-risk neuroblastoma patient. As with the healthy donor assays, only heparinised and not EDTA WB produced a significant ADCC response with samples still being responsive 24-h post-draw when stored at RT (Fig. 5a). PBMC processed 24-h post-draw from heparinised samples were also sufficiently stable to produce a significant ADCC response (Fig. 5b). The level of CD107a expressed on NK cells recovered from the ADCC assays was equivalent for samples used immediately or after storage for 24 h (Fig. 5c). These results confirm heparin as the preferred anticoagulant, with a window of 24 h at room temperature post-draw for assessing ADCC functional activity.

Fig. 5.

Anticoagulant effect (EDTA vs. heparin) and 24-h sample stability were assessed using samples from a high-risk neuroblastoma patient. a Heparinised whole blood produced a significant ADCC response, which was maintained 24-h post-sample collection. EDTA samples were unresponsive. b Stability of the PBMC ADCC response was maintained using heparin samples stored at room temperature (RT) 24-h post-draw. c PBMC recovered from the ADCC assay showed an increase in the % CD107a+ CD56+ NK cells for heparin samples used immediately and 24-h post-draw. The PBMC and WB ADCC response was monitored on Day 1 pre-treatment (d) and on Day 4 (e) of anti-GD2 antibody therapy. Day 1 shows increased cell lysis with Lan-1+ anti-GD2 for PBMC, WB and serum. There is no response in the absence of antibody (eff+ Lan-1). On Day 4, there is an equivalent response using Lan-1 with or without anti-GD2 for PBMC, WB and serum. WB responses on both Day 1 and Day 4 are equivalent to the combined PBMC ADCC and serum CDC responses. f On Day 1, effectors+ Lan-1+ anti-GD2 show an increase in the % CD107a+ CD56+ NK cells in PBMC samples, with only a small increase in WB CD56+ NK cells. However, WB shows an increase in CD107a+ CD16+ (non-NK) cells. On Day 4, effectors alone (baseline) have a higher % CD107a+ cells than Day 1. In the presence of Lan-1, the % CD107a+ CD56+ NK and CD16+ (non-NK) cells is further increased, with CD16+ non-NK cells in WB having an additional increase with Lan-1+ anti-GD2. (*0.01 < p < 0.05; **0.001 < p < 0.01; ns non-significant; p > 0.05)

To assess the feasibility of monitoring ADCC during anti-GD2 therapy, heparinised samples were taken pre-ch14.18mAb therapy (Day 1) and on Day 4 of therapy from patient. On Day 1, there was a minimal AICC response and a significant ADCC response with anti-GD2 opsonised Lan-1 cells for both PBMC and WB (Fig. 5d). A complement-mediated response was also measured using serum with anti-GD2 opsonised Lan-1 cells. On Day 4, all effectors (PBMC, WB and serum) produced a response whether the Lan-1 had been pre-opsonised with the anti-GD2 antibody or not. This suggests that during therapy, there is no sufficient anti-GD2 antibody in the peripheral blood to produce an ADCC response, and therefore monitoring a longitudinal response in this way will allow correlation with pharmacokinetics. The results also demonstrate that the level of cell lysis with whole blood was broadly equivalent to the combined ADCC and CDC response measured independently with matched PBMC and serum, respectively.

Results for CD107a expression showed an increase in the percentage of CD107a+ CD56+ NK cells on Day 1 when effectors were incubated with Lan-1+ anti-GD2 antibody, although this increase was smaller in whole-blood assays. However, as with the healthy donors, the percentage of CD107a+ non-NK CD16+ granulocytes also increased. On Day 4, effectors alone already had an increased percentage of CD107a+ CD56+ NK cells and CD16+ non-NK cells, suggesting that anti-GD2 therapy is activating effector cells in vivo. In the assay with Lan-1 target cells, the percentage of CD107a+ effector cells is further increased. In the whole-blood assays, but not those with PBMC, CD107a mobilisation was also demonstrated on CD16+ non-NK cells with an additional increase with Lan-1+ anti-GD2.

Discussion

Despite the impact anti-GD2 antibody therapy has made on survival outcomes in high-risk neuroblastoma patients, prognosis is still relatively poor, and the exact in vivo mechanisms of action are not fully understood, but appear to include a complex interplay of 3 innate components: NK, granulocytic cells (neutrophil/macrophage) and complement. Elucidating the relative importance of the different immune effector mechanisms is central to understanding why therapy is not successful in all patients and to rationally design more effective antibody therapies.

To date, much of our understanding of targeted therapy is based on murine models and in vitro studies. This provides an invaluable platform to build on, but if NK cell ADCC activity is the ultimate arbiter of outcome, it is necessary to reassess these mechanisms in a clinical setting, due to the considerable interspecies differences in these immune cells and the possibility of non-comparability [12]. In addition, inherent variations of NK response between patients are likely to be influenced by NK subset enumeration and FcγR single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP). A study involving lymphoma patients receiving rituximab demonstrated the importance of the FcγRIIIa 158 V/F SNP, with the V/V phenotype having a higher affinity for the IgG1 isotype compared to the F/F phenotype and correlated to a better clinical outcome following antibody therapy [13]. Although most studies have focussed specifically on NK-mediated ADCC, some studies have investigated how different immune factors may be influencing the ADCC response, including contradictory reports on serum complement components either being detrimental by blocking the mAb from binding CD16 on NK cells [14] or complimentary to ADCC activity dependent on antigen expression on target cells [15]. More recently, FcγR-bearing neutrophils have also been shown to have a significant role in mAb therapy in melanoma and breast cancer murine models of tumour regression [16]. In a neuroblastoma clinical study investigating a murine IgG3 anti-GD2 antibody, 3F8, patients having the FcγRIIa R/R genotype responded better than those with the H/R or H/H phenotype and was correlated to a better antibody-mediated phagocytic response [17]. As the FcyRIIa receptor is expressed by myeloid cells and not by lymphocytes, the study suggests an important role for non-NK FcR-bearing cells. The response measures of CDC, NK-mediated ADCC and activity of other FcγR-bearing myeloid cells such as neutrophils could all be monitored simultaneously within our whole-blood assays.

In addition to innate immune responses, the ultimate aim of immunotherapy would be to establish a longer-term adaptive immune memory response, particularly important in cancers such as neuroblastoma where patients often harbour difficult to detect minimal residual disease. We would hypothesise that the active innate immune environment following immune therapy creates an environment for recruitment and stimulation of the adaptive immune system. In particular, we see early activation of CD8 cytotoxic T lymphocytes, a key arm of the adaptive immune response, suggesting that this may provide an opportunity for further immune modulation to develop a secondary anti-tumour response via stimulatory antibodies or peptide vaccination [18].

Multisite immunomonitoring raises many logistical issues that must be overcome and coordinated to establish a central immunomonitoring programme [19]. The primary aim of this study was to address several of these issues to demonstrate that multisite paediatric immunomonitoring is a realistic option. Firstly, cost, distance and timing make it difficult to have samples shipped on the same day to a central analysis site. We have shown that for functional ADCC assays, samples in heparinised but not EDTA collection tubes are necessary, with whole blood rather than PBMC giving an optimal response and with a more stable response at 24 h. We have also shown that such a shipment would be preferable at ambient temperature as opposed to 4 °C. This would provide a 24-h window for sample shipment from multiple sites without the requirement of sample processing. We would recommend however that all samples from a single patient are analysed using the same timeframe to allow comparable longitudinal monitoring of change in response for an individual.

In this study, we have shown that whole blood provides a more holistic analysis of the immune response, mimicking the multi-faceted coordinated response within a patient, each of which may impact on the balance of another component and hence the overall response and clinical outcome. In addition, it would be more probable that sufficient samples could be collected as opposed to the unattainable large volumes required for PBMC assays often the hindering factor for comprehensive immunomonitoring, and the impact of variability introduced by site-to-site sample processing would be mitigated. We anticipate that ‘real-time’ monitoring of patients’ whole blood will allow more comprehensive analysis of multiple mechanisms to be linked to clinical outcomes. It is also feasible to consider that a patient’s pre-therapy immune status will have a bearing on clinical outcome, and this knowledge could inform stratification of immune therapies.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- ADCC

Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity

- AICC

Antibody-independent cellular cytotoxicity

- CDC

Complement-dependent cytotoxicity

- CTL

CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes

- CV

Coefficient of variance

- EFS

Event-free survival

- FcγR

Fc gamma receptor

- LRS

Leucocyte reduction system

- mAb

Monoclonal antibody

- NK

Natural killer cell

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- RT

Room temperature

- WB

Whole blood

References

- 1.Anegón I, Cuturi MC, Trinchieri G, Perussia B. Interaction of Fc receptor (CD16) ligands induces transcription of interleukin 2 receptor (CD25) and lymphokine genes and expression of their products in human natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 1988;167(2):452–472. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.2.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alderson KL, Sondel PM. Clinical cancer therapy by NK cells via antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:379123. doi: 10.1155/2011/379123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maris JM. Recent advances in neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2202–2211. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthay KK, Reynolds CP, Seeger RC, Shimada H, Adkins ES, Haas-Kogan D, Gerbing RB, London WB, Villablanca JG. Long-term results for children with high-risk neuroblastoma treated on a randomized trial of myeloablative therapy followed by 13-cis-retinoic acid: a children’s oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(7):1007–1013. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.8925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kramer K, Gerald WL, Kushner BH, Larson SM, Hameed M, Cheung NK. Disialoganglioside G(D2) loss following monoclonal antibody therapy is rare in neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:2135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu AL, Gilman AL, Ozkaynak MF, London WB, Kreissman SG, Chen HX, Smith M, Anderson B, Villablanca JG, Matthay KK. Anti-GD2 antibody with GM-CSF, interleukin-2, and isotretinoin for neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(14):1324–1334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeng Y, Fest S, Kunert R, Katinger H, Pistoia V, Michon J, Lewis G, Landenstein R, Lode HN. Anti-neuroblastoma effect of ch14.18 antibody produced in CHO cells is mediated by NK-cells in mice. Mol Immunol. 2005;42(11):1311–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma P, Wagner K, Wolchok JD, Allison JP. Novel cancer immunotherapy agents with survival benefit: recent successes and next steps. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(11):805–812. doi: 10.1038/nrc3153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Staff C, Magnusson CG, Hojjat-Farsangi M, Mosolits S, Liljefors M, Frödin JE, Wahrén B, Mellstedt H, Ullenhag GJ. Induction of IgM, IgA and IgE antibodies in colorectal cancer patients vaccinated with a recombinant CEA protein. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32(4):855–865. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9662-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neri S, Mariani E, Meneghetti A, Cattini L, Facchini A. Calcein-acetyoxymethyl cytotoxicity assay: standardization of a method allowing additional analyses on recovered effector cells and supernatants. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8(6):1131–1135. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.6.1131-1135.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beers SA, Chan CH, James S, French RR, Attfield KE, Brennan CM, Ahuja A, Shlomchik MJ, Cragg MS, Glennie MJ. Type II (tositumomab) anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody out performs type I (rituximab-like) reagents in B-cell depletion regardless of complement activation. Blood. 2008;112:4170–4177. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-149161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mestas J, Hughes CC. Of mice and not men: differences between mouse and human immunology. J Immunol. 2004;172(5):2731–2738. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheung NK, Sowers R, Vickers AJ, Cheung IY, Kushner BH, Gorlick R. FCGR2A polymorphism is correlated with clinical outcome after immunotherapy of neuroblastoma with anti-GD2 antibody and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18):2885–2890. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.6011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang SY, Racila E, Taylor RP, Weiner GJ. NK-cell activation and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity induced by rituximab-coated target cells is inhibited by the C3b component of complement. Blood. 2008;111(3):1456–1463. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-074716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Meerten T, van Rijn RS, Hol S, Hagenbeek A, Ebeling SB. Complement-induced cell death by rituximab depends on CD20 expression level and acts complementary to antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(13):4027–4035. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albanesi M, Mancardi DA, Jönsson F, Iannascoli B, Fiette L, Di Santo JP, Lowell CA, Bruhns P. Neutrophils mediate antibody-induced anti-tumor effects in mice. Blood. 2013;122(18):3160–3164. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-497446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veeramani S, Wang SY, Dahle C, Blackwell S, Jacobus L, Knutson T, Button A, Link BK, Weiner GJ. Rituximab infusion induces NK activation in lymphoma patients with the high-affinity CD16 polymorphism. Blood. 2011;118(12):3347–3349. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-351411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams EL, Dunn SN, James S, Johnson PW, Cragg MS, Glennie MJ, Gray JC. Immunomodulatory monoclonal antibodies combined with peptide vaccination provide potent immunotherapy in an aggressive murine neuroblastoma model. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(13):3545–3555. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chowdhury F, Williams AP. From research to regulated: challenges in transferring methods. Bioanalysis. 2009;1(2):285–291. doi: 10.4155/bio.09.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]