Abstract

4-1BB ligation co-stimulates T cell activation, and agonistic antibodies have entered clinical trials. Natural killer (NK) cells also express 4-1BB following activation and are implicated in the anti-tumour efficacy of 4-1BB stimulation in mice; however, the response of human NK cells to 4-1BB stimulation is not clearly defined. Stimulation of non-adherent PBMC with OVCAR-3 cells expressing 4-1BB ligand (4-1BBL) or IL-12 resulted in preferential expansion of the NK cell population, while the combination 4-1BBL + IL-12 was superior for the activation and proliferation of functional NK cells from healthy donors and patients with renal cell or ovarian carcinoma, supporting long-term (21 day) NK cell proliferation. The expanded NK cells are predominantly CD56bright, and we show that isolated CD56dimCD16+ NK cells can switch to a CD56brightCD16− phenotype and proliferate in response to 4-1BBL + IL-12. Whereas 4-1BB upregulation on NK cells in response to 4-1BBL required ‘help’ from other PBMC, it could be induced on isolated NK cells by IL-12, but only in the presence of target (OVCAR-3) cells. Following primary stimulation with OVCAR-3 cells expressing 4-1BBL + IL-12 and subsequent resting until day 21, NK cells remained predominantly CD56bright and retained both high cytotoxic capability against K562 targets and enhanced ability to produce IFNγ relative to NK cells in PBMC. These data support the concept that NK cells could contribute to anti-tumour activity of 4-1BB agonists in humans and suggest that combining 4-1BB-stimulation with IL-12 could be beneficial for ex vivo or in vivo expansion and activation of NK cells for cancer immunotherapy.

Keywords: NK cells, 4-1BB (CD137), 4-1BBL (CD137L), IL-12, Ovarian cancer, Renal cell carcinoma

Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells are defined as a population of CD3−CD56+ cells that contribute about 10% of total circulating lymphocytes. Initially named for their intrinsic ability to lyse tumour cells, NK cells have gained attention as potential effectors for cancer immunotherapy, particularly in the setting of adoptive transfer [1–3].

Human NK cells can be subdivided into CD56bright and CD56dim subsets, which have differential distribution, gene expression and functions [4–7]. Most circulating NK cells are of the CD56dim subset, which are further defined by the expression of CD16 (FcRγIII); intrinsic cytotoxicity is mainly associated with this subset. Conversely, CD56bright NK cells are enriched in secondary lymphoid tissues and are superior producers of immunoregulatory cytokines including IFNγ, TNFα and GM-CSF. The consensus has emerged that the CD56dim subset represents a more mature population derived from CD56bright NK cells [4, 8–10]. However, the relationship between these subsets is not fully understood, and further diversity of phenotype and function has been reported, particularly among the CD56dim population [11–13].

The TNF receptor family member 4-1BB (CD137) was first identified on activated T cells, where its engagement by 4-1BB ligand (4-1BBL) inhibits activation-induced cell death and co-stimulates their continued activation and proliferation [14–16]. Stimulation via 4-1BB showed immunotherapeutic activity against murine tumours [17, 18], leading to recent human clinical trials of agonistic antibody in cancer patients [19]. NK cells were also found to express 4-1BB [20] and to be required for the anti-tumour efficacy of 4-1BB stimulation in murine models [20–23]. Furthermore, several studies reported that IL-12 could enhance the anti-tumour efficacy of 4-1BB co-stimulation [21–24]. 4-1BB is also expressed by human NK cells in response to activation [3, 25]; however, few studies have addressed the effects of 4-1BBL stimulation on human NK cells, and these are somewhat contradictory, demonstrating either activation [2] or impairment of human NK cell responses [3]. Further studies are required to resolve these differences and expand our understanding of the effects of 4-1BB ligation, and the combination with IL-12, on human NK cells.

In Europe, renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the seventh most common cancer in men and the twelfth in women, while ovarian cancer ranks fifth in prevalence in women [26]. Prognosis of both cancers is generally poor, indicating an unmet clinical need that could be addressed by novel immunotherapies. Indeed, immunotherapy with systemic IFNα or IL-2 are first line therapies for metastatic RCC following surgery, producing objective response rates between 10 and 20% [27, 28].

In the present study, we investigate the response of human NK cells to carcinoma cells transduced to express 4-1BBL or IL-12 alone and in combination. We show 4-1BBL + IL-12 stimulates superior long-term proliferation, preferentially expanding NK cells of the CD56bright subset and inducing CD56dimCD16+ NK cells to become CD56brightCD16− and proliferate. NK cells from patients with renal or ovarian cancer exhibit a similar proliferative response to 4-1BBL + IL-12. We demonstrate the functionality of the expanded NK cells, both after 7 days stimulation and following a further 2-week rest. These data extend our understanding of the response of human NK cells to 4-1BBL and predict an advantage for the use of IL-12 in addition to a 4-1BB agonist for cancer immunotherapy.

Materials and methods

Blood samples and cell lines

Fresh heparinised blood samples were obtained, with ethical committee approval and informed consent, from healthy volunteers and RCC patients at the time of first treatment (nephrectomy). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by Ficoll Hypaque density gradient centrifugation (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and adherent cells were depleted by plastic adhesion for 2 h prior to use. Ascitic fluid samples were obtained from ovarian cancer patients, tumour-associated lymphocytes (TAL) were obtained by centrifugation (540×g for 15 min), and adherent cells were depleted by plastic adhesion overnight prior to use. PBMC, TAL and all cell lines were routinely cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin (Sigma).

mAbs and flow cytometric analysis

The following fluorophore-labelled mouse anti-human mAbs, and isotype controls, were purchased from BD Pharmingen: anti-CD56-APC/PE, anti-CD3-FITC/Pacific blue, anti-CD137-PE, anti-CD16-FITC/PE-Cy7, anti-CD62L-APC, anti-CCR7-PE-Cy7, anti-CD137(4-1BB)-PE, anti-CD107a(LAMP-1)-FITC, anti-NKG2D-APC, anti-CD158a-FITC and anti-IFNγ-PE. Anti-CXCR3 (BD) was detected using anti-mouse IgG-PE (Sigma). Anti-CD158e-biotin (Biolegend) was detected using Qdot655 (Invitrogen). Stained cells were analysed using a LSRII™ flow cytometer employing FACSDiva Software (BD Biosciences), and data analysed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc). Graphpad Prism software was used for statistical analysis.

Infection with adenoviral vectors

The E1,E3-deleted, replication-defective adenoviruses expressing human 4-1BBL and enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) were reported previously [16]. DNA sequences encoding the p35 and p40 subunits of IL-12 were amplified by RT-PCR from PMA-stimulated human PBMC and cloned downstream of the CMV promoter separated by the poliovirus internal ribosome entry site (IRES) in the order CMV-p35-IRES-p40, and sequenced to confirm the absence of mutations (R. Doshi and P. Searle, unpublished). This expression-cassette was introduced into E1,E3-deleted, replication-defective adenovirus essentially as described [16].

Forty-eight hours prior to stimulation of PBMC/NK cells, OVCAR-3 cells (ATCC, Number HTB-161™) were harvested and re-suspended at 1 × 106 cell/ml. Cells were infected using Ad-4-1BBL or Ad-GFP at 3,000 virus particles/cell; Ad-IL-12 was used at 600 virus particles/cell. The virus–cell mixture was incubated at 37°C for 90 min with frequent gentle mixing, before distributing 1 × 105 cells/well in a 48-well tissue culture plate, in 500 μl/well DMEM supplemented with 2% FCS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin.

OVCAR-3 co-cultures for the stimulation of NK cells

For the stimulation of PBMC, medium was removed from OVCAR-3 cells (previously infected with the appropriate adenovirus vector) and 0.5 × 106 PBMC in 1 ml of complete RPMI added to each well. For culture beyond 7 days with re-stimulation, cells were redistributed to fresh wells of a 48-well plate containing 1 ml of complete RPMI supplemented with IL-2 (20 U/ml). Re-stimulation of cultures with (pre-infected) OVCAR-3 cells was performed at day 14, with the continued presence of 20 U/ml IL-2. Cultures were counted by haemocytometer at day 7, 14 and 21 of culture, and the proportions of NK, T and NKT cells were determined by flow cytometry to ascertain the actual NK cell number; expansion was then calculated relative to the starting population.

Whole NK cell population and CD56dimCD16+ NK cell subset isolation

For some experiments, total purified NK cells were negatively isolated from PBMC using a Miltenyi Biotec CD56+CD16+ NK Cell isolation kit and, when specified, further selected for CD16+ cells. In other experiments, CD3−CD56dimCD16+ cells were isolated from the total purified NK cells using a MoFlo cell sorter (Beckman Coulter). In each case, the isolated NK cells were plated at 0.5 × 105 cells/well in 48-well plates containing pre-infected stimulator cells as required. To permit tracking of cell divisions in some experiments, isolated NK populations were stained with 2.5 μM carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) in PBS for 15 min at 37°C, then diluted and washed three times in culture medium before plating with the stimulator cells.

Intracellular IFNγ staining

3 × 105 cells were re-suspended in complete RPMI containing 20 U/ml IL-2, 10 μg/ml Brefeldin A for 4 h at 37°C. Intracellular staining was then performed using a Fix & Perm kit (An Der Grub, Austria) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cytokine ELISA assays

IFNγ production

After 7 days stimulation, lymphocyte cultures were re-suspended at 0.5 × 106 cells/ml in fresh complete RPMI and plated into 96-well plates. Following overnight culture, plates were centrifuged at 355×g for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatant collected and stored at −20°C until assayed.

IL-12 production by Ad-IL-12 infection of OVCAR-3 cells

OVCAR-3 cells were infected and plated in a 48-well plate as described. Following 48 h incubation, the medium was replaced with 1 ml of fresh medium. After a further 24 h incubation, supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C until assayed.

ELISA assays

Maxisorp 96-well plates (Nunc) were coated with 50 μl/well coating buffer (0.1 M Na2HPO4, pH 9) containing either 0.75 μg/ml anti-human-IFNγ antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, clone 2G1) or 4 μg/ml anti-IL-12p35 (eBioscience, clone B-T21) by overnight incubation at 4°C. The unbound antibody was washed off using three washes with PBS + 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20. The plate was then blocked with 200 μl/well PBS + 1% (w/v) BSA + 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature (RT). The plate was washed 5 times and 50 μl of sample added to each well in triplicate. Culture supernatants were serially diluted 1:10–1:1,000 and IFNγ (Sigma) or IL-12 (Peprotech) standard solutions were serially diluted 1:2 (range 2,000–31.5 pg/ml). Plates were incubated at RT for 3 h and then washed five times with PBS + 0.1% Tween 20. Fifty microlitres of Biotinylated anti-IFNγ (Thermo Fisher Scientific, clone B133.5) or anti-IL-12p40/p70 (eBioscience, clone C8.6), diluted in blocking buffer to 0.37 or 0.5 μg/ml, respectively, was added to each well. Plates were incubated at RT for 1 h and again washed five times. Extravidin-peroxidase (Sigma) was diluted in blocking buffer (1:1,000) and 50 μl added to each well. After 30 min incubation at RT and nine final washes, 100 μl TMB chromogen (Tebu-Bio) was added to each well. The reaction was stopped with 100 μl of 1 M hydrochloric acid and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Wallac Victor2 1420 Multilabel Counter (PerkinElmer, Monza, Italy).

Chromium release assay

Cytotoxicity was analysed by standard chromium release assay. K562 target cells were labelled with Na512CrO4 (Amersham, Germany) for 90 min at 37°C and washed three times. 5 × 103 target cells were plated per well of a 96-well V-bottom plate. Effector cells were added at appropriate effector:target (E:T) ratios. Maximum release was determined from target cells lysed with 1% (w/v) SDS in RPMI. Percentage specific lysis was calculated as follows: 100 × (experimental release–spontaneous release)/(maximum release–spontaneous release).

Syto 16 cell viability staining

Following a modified protocol as described by Sparrow and Tippett [29], cultured cells were stained with Syto 16. Briefly, cells were removed from culture and washed with cold saline, centrifuging at 540×g for 10 min at 4°C. The cell pellet was then resuspended in 500 μl saline + 10 nM Syto 16 supplemented with 0.5% BSA + 30 μM Verapamil (Sigma) and incubated at 37°C for 45 min. Cells were then washed in PBS(pH7.2) + 0.5%BSA + 2 mM EDTA, subsequently antibody staining was performed with the required antibodies. Propidium iodide (40 μg/ml) was added prior to analysis by flow cytometry.

Response of rested NK cells to restimulation with targets

Following initial stimulation for 7 days with 4-1BBL + IL-12 expressing OVCAR-3, stimulated lymphocytes were counted by haemocytometer, resuspended in complete RPMI at 0.5 × 106 cells/ml and redistributed into fresh tissue culture plates. Cultures were fed and passaged as required. No IL-2 was added until the point of restimulation with targets at which time all cultures were supplemented with 20 U/ml IL-2. At 21 days of culture, previously stimulated cells or rested, autologous PBMC (cryopreserved at the time of initial stimulation) were mixed with K562 or OVCAR-3 cells at a ratio of 2:1, or without additional cells (mock) in V-bottom, 96-well plates and centrifuged at 355g × 3 min. To detect degranulation by mobilisation of CD107a, monensin was added to a final concentration of 0.25 μg/ml, along with either 5 μl of anti-CD107a or isotype control antibody, prior to pelleting of cells. In order to detect IFNγ production, 10 μg/ml Brefeldin A was added following a 1 h incubation at 37°C, cells were cultured for a further 5 h. IFNγ production was then determined by intracellular staining.

Results

4-1BBL + IL-12 stimulates superior NK cell proliferation

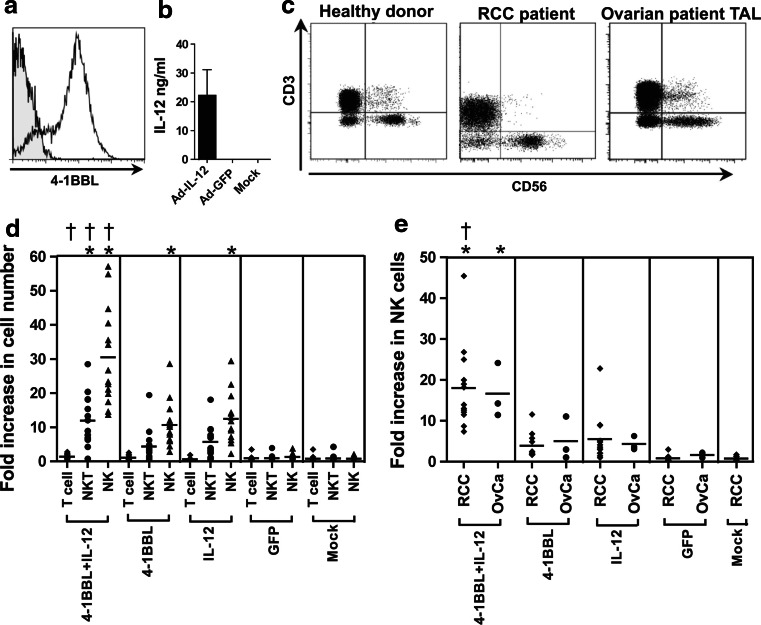

Figure 1a, b shows typical levels of 4-1BBL or IL-12 expression obtained 48–72 h following infection of OVCAR-3 ovarian carcinoma cells with Ad-4-1BBL or Ad-IL-12, as described in “Materials and methods”. Typical profiles for the expression of CD3 and CD56 on freshly isolated, non-adherent PBMC from healthy donors or RCC patients and for freshly isolated TAL from ovarian cancer patients are shown in Fig. 1c. PBMC from 15 healthy donors were co-cultured for 7 days with OVCAR-3 cells that had been pre-infected with adenovirus vectors expressing 4-1BBL, IL-12, GFP or mock-infected. There was negligible expansion of the T cell (CD3+CD56−) population in any of these conditions (Fig. 1d). While NKT (CD3+CD56+) cells showed modest expansion in response to 4-1BBL or IL-12, they remained a minor population in the cultures (due to the low starting population). However, NK (CD3−CD56+) cells showed the greatest expansion and formed the largest cell population following stimulation with 4-1BBL and/or IL-12. Neither the mock-infected cells nor those expressing GFP stimulated significant NK cell proliferation. In contrast, stimulation with either 4-1BBL or IL-12 induced proliferation of NK cells [10.6 ± 6.5- and 11.8 ± 7.5-fold expansion, respectively (mean ± SD)]. The combination of 4-1BBL + IL-12 significantly increased NK cell proliferation (29.7 ± 14.2-fold expansion), compared with either single stimulation.

Fig. 1.

Proliferation of NK cells in response to stimulation with OVCAR-3 cells expressing 4-1BBL and IL-12. a Flow cytometric confirmation of 4-1BBL expression by OVCAR-3 cells 48 h after infection with Ad-4-1BBL (open histogram), versus uninfected OVCAR-3 cells (shaded). b Level of IL-12 secreted in 1 ml medium between 48 and 72 h post-infection by 1 × 105 OVCAR-3 cells infected with Ad-IL-12 as described, Ad-GFP-infected or uninfected cells as controls, measured by ELISA. c Fresh PBMC from healthy donors or RCC patients, or TAL from patients with ovarian carcinoma, were stained with anti-CD3 and anti-CD56, and analysed by flow cytometry; typical results are shown. d Non-adherent PBMC from 15 healthy donors were co-cultured with OVCAR-3 cells pre-infected with adenovirus vectors expressing GFP, IL-12, 4-1BBL, or 4-1BBL + IL12, or mock-infected. After 7 days, viable lymphocytes were counted by haemocytometer and characterised by flow cytometry to identify T cells (CD3+CD56−), NKT cells (CD3+CD56+) or NK cells (CD3−CD56+), enabling calculation of their expansion relative to the starting populations. e Expansion of NK cells from PBMC of 13 RCC patients (RCC) or TAL from 3 ovarian cancer patients (OvCa) when stimulated and analysed as in d. Results for each cell type were analysed by one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison post-test; *P < 0.05 for comparison with GFP control; † P < 0.05 for comparison of 4-1BBL + IL-12 with IL-12 alone

We also investigated NK cell responses using PBMC from 13 RCC patients and TAL from 3 ovarian cancer patients. The combination of 4-1BBL + IL-12 stimulation enhanced the expansion of NK cells from RCC patients (18.0 ± 10.1-fold) and ovarian cancer patients (16.6 ± 6.7-fold) compared with either 4-1BBL (4.0 ± 3.0 and 5.1 ± 5.3-fold) or IL-12 (5.5 ± 5.8 and 4.4 ± 1.7-fold) stimulation alone (Fig. 1e). This pattern is similar to that seen with healthy donors, although average expansions were ~30% lower.

Phenotypic analysis of expanded NK cells

Whereas NK cells in freshly isolated PBMC are predominantly CD56dim (Figs. 1c, 2a), we observed that stimulation with 4-1BBL and/or IL-12 caused a marked increase in the ratio of CD56bright:CD56dim NK cells (Fig. 2a–c). While the proportion of CD56bright NK cells following 7 days co-culture with mock-infected OVCAR-3 cells averaged 13%, similar to the level in fresh PBMCs, this typically increased to 70–90% after 7 days stimulation with 4-1BBL and/or IL-12. Conversely, CD16 expression (a defining marker of the CD56dim NK cell subset) decreased significantly compared with control cultures following stimulation with 4-1BBL and/or IL-12 (from 69.7 ± 8.0% CD16+ for mock to 15.7 ± 8.1% CD16+ for 4-1BBL + IL-12; Fig. 2d). These data suggest that 4-1BBL and IL-12 preferentially expanded a population of NK cells of the CD56bright phenotype.

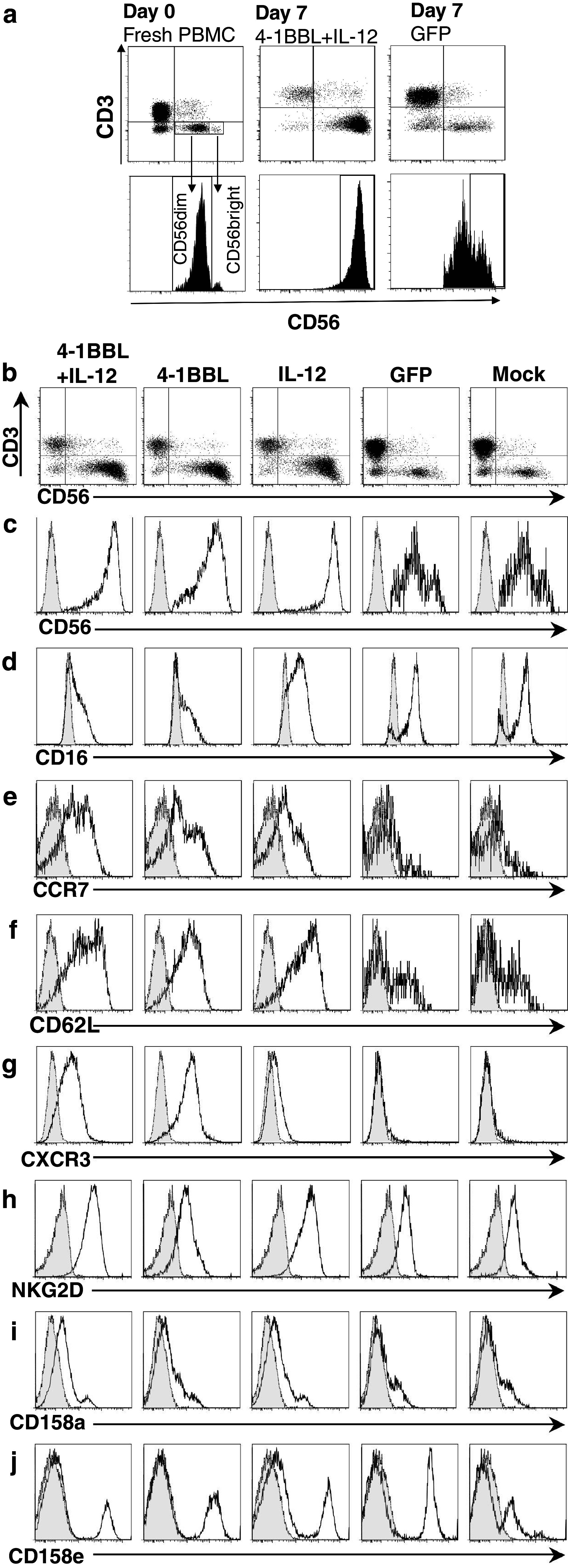

Fig. 2.

Phenotype of expanded NK cells. PBMC from healthy donors, stimulated for 7 days as in Fig. 1, were stained for CD3 and CD56 to identify NK cells, and with additional antibodies as indicated. a Scatter and histogram plots illustrating gating of CD56dim and CD56bright NK cells, and the change from predominantly CD56dim cells at day 0, to CD56bright after 7 days stimulation with 4-1BBL + IL-12. b Scatter plots of CD3 versus CD56 for all stimulation conditions; c–j histogram plots gated on CD3−CD56+ NK cells, showing expression of CD56, CD16, CCR7, CD62L, CXCR3, NKG2D, CD158a (KIR2DL1/S1) and CD158e (KIR3DL1) as indicated (heavy line, open; thin line, shaded isotype controls)

The CD56bright subset of NK cells typically have high levels of the chemokine receptor CCR7 (absent from CD56dim cells [4]) and CD62L (present on only a sub-population of CD56dim NK cells [11]). Analysis of these differentially expressed markers showed that all three active stimulatory conditions increased the proportions of NK cells expressing CCR7+ (Fig. 2e) and CD62L (Fig. 2f).

The chemokine receptor CXCR3 (associated with tumour homing [30]) is characteristically absent or minimally expressed on CD56dim NK cells, but upregulated on CD56bright cells [4]. IL-12 stimulated marginal increase in CXCR3 expression relative to control cultures in the NK cell population (Fig. 2g). In contrast, 4-1BBL stimulation markedly increased the expression of CXCR3, either when combined with IL-12 or more strongly alone. The elevated levels of these homing markers on NK cells expanded by 4-1BBL + IL-12 further support their identification as typical of the CD56bright subset.

We also examined the expression of the NK cell receptors NKG2D (receptor for the cell stress-associated ligands MICA, MICB and ULBPs expressed by many cancers [31]) and killer immunoglobulin-like receptors CD158a (KIR2DL1/KIR2DS1) and CD158e (KIR3DL1). The majority of NK cells in PBMC expressed NKG2D (79.0 ± 7.3%); the proportion was marginally higher, and mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of NKG2D positive cells increased significantly in cultures with IL-12 (±4-1BBL), compared with day 0 or GFP control. There was no significant overall change in the proportion of CD158a+ or CD158e+ cells, and considering the overall increase in NK cell numbers, both positive and negative cells for either KIR from all donors must have proliferated in response to the individual and combined stimuli.

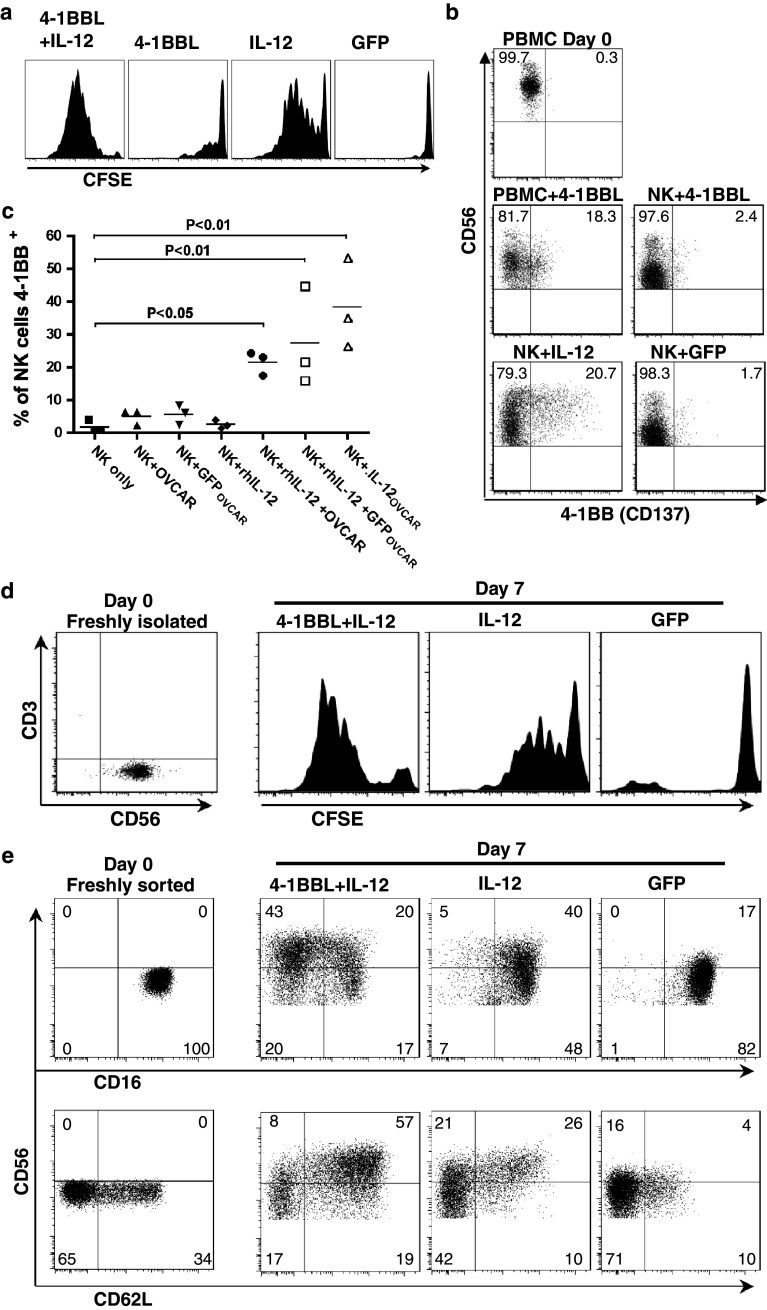

Response of isolated NK cells: multiple signal requirement to induce 4-1BB expression

To investigate the autonomy of NK cell response to 4-1BBL and IL-12, we purified total NK cells by negative isolation and stimulated them as above, after labelling with the vital dye CFSE to track cell divisions [32]; typical data are shown in Fig. 3a. After 7 days, on average 35.3% (± 26.9%) of cells in cultures stimulated with OVCAR-3 cells expressing IL-12 alone remained undivided, the remainder had undergone up to 10 or more divisions (mode—5 divisions). Cultures stimulated with both 4-1BBL + IL-12 showed significantly greater proliferation, with a mean of 10.7% (±13.1%) of NK cells remaining undivided, and a modal number of 7 divisions. In contrast, relatively little proliferation was observed in cultures stimulated with OVCAR-3 cells expressing 4-1BBL alone (mean 66.3 ± 13.1% undivided); we therefore investigated the expression of its receptor, 4-1BB, by NK cells in the different conditions.

Fig. 3.

Proliferation, induction of 4-1BB expression and phenotypic conversion of isolated NK cells. a Negatively isolated NK cells were labelled with CFSE then co-cultured for 7 days with OVCAR-3 cells expressing GFP (as control), 4-1BBL, IL-12 or 4-1BBL + IL-12, prior to flow cytometric analysis (gated on CD56+ cells; results are typical of 3 donors). b Negatively isolated NK cells or adherent cell-depleted PBMC were stimulated with OVCAR-3 cells expressing 4-1BBL, IL-12 or GFP (as indicated) for 3 days, before 4-1BB expression on NK cells (CD3−CD56+) was determined by flow cytometry; 4-1BB expression on NK cells in freshly isolated PBMC (day 0) is shown for comparison. Gated on CD3−CD56+ cells; results are typical of 4 donors. c Negatively isolated NK cells were cultured for 3 days alone or in the presence or absence of recombinant human IL-12 (rhIL-12, 20 ng/ml) and OVCAR-3 cells pre-infected with adenovirus expressing GFP (GFPOVCAR) or IL-12 (IL-12OVCAR), or mock-infected (OVCAR). Expression of 4-1BB by the NK cells was then determined by flow cytometry (ANOVA, Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test vs. NK only control). d Negatively isolated CD56+ NK cells were magnetically selected for CD16+ cells; the resulting CD56dim CD16+ population was analysed immediately for CD3 and CD56 expression, or stained with CFSE prior to stimulation with OVCAR-3 cells pre-infected with Ad-4-1BBL + Ad-IL-12, Ad-IL-12 or Ad-GFP vectors as indicated for 7 days, and CFSE dilution in CD56+ cells analysed by flow cytometry; results typical of 2 donors. e CD56dim CD16+ NK cells were isolated by fluorescence activated cell sorting, then analysed immediately (Day 0) or co-cultured with OVCAR-3 cells expressing 4-1BBL + IL-12, IL-12 or GFP as control, for 7 days. Expression of CD56, CD16 and CD62L were determined by flow cytometry, gated on CD3− lymphocytes. Results are typical of 4 donors

Few unstimulated NK cells express 4-1BB, and as shown for a representative donor in Fig. 3b, negatively isolated NK cells showed minimal upregulation of 4-1BB in response to targets expressing 4-1BBL. However, it was significantly upregulated by day 3 of stimulation (which precedes the onset of proliferation) in cultures using total non-adherent PBMC, suggesting that some form of “help” (perhaps cytokine secretion) from another, 4-1BBL-responsive, cell type present in PBMC is required.

In contrast, isolated NK cells were induced to express 4-1BB (20.7% 4-1BB+) by OVCAR-3 cells expressing IL-12 (Fig. 3b), so we asked whether IL-12 alone would induce 4-1BB or whether target cell recognition was also required. Neither uninfected OVCAR-3 cells nor those infected with control adenovirus induced isolated NK cells to express 4-1BB. Significantly, NK cells also failed to upregulate 4-1BB in response to rhIL-12 in the absence of OVCAR-3 cells (Fig. 3c). However, the combination of uninfected or GFP-expressing OVCAR-3 cells and rhIL-12 induced 4-1BB expression to levels approaching those induced by OVCAR-3 cells infected with the IL-12-expressing adenovirus.

CD56dimCD16+ NK cells differentiate to a CD56bright phenotype in response to 4-1BBL + IL-12

CD56bright NK cells only comprise ~10% of NK cells in blood, yet the expanded NK cells were predominantly CD56bright. It was therefore of interest to determine whether only the CD56bright population responded or whether CD56dim cells were also activated and converted to a CD56bright phenotype. To test this, first, magnetically enriched CD3−CD56dimCD16+ NK cells were labelled with CFSE and stimulated for 7 days with OVCAR-3 cells expressing either 4-1BBL + IL-12 or IL-12 alone (or GFP as control; 4-1BBL alone was not used as the purified NK cells required IL-12 to induce 4-1BB). As shown in Fig. 3d, there was a clear proliferative response to IL-12 alone, and a markedly stronger response to the combined 4-1BBL + IL-12 stimulation, indicating that many isolated CD56dimCD16+ cells could proliferate in response to these stimuli, to an extent comparable with the response of total NK cells (Fig. 3a).

To investigate concommitant phenotypic change, CD3−CD56dimCD16+ NK cells were sorted by FACS and stimulated as above (Fig. 3e). NK cells in control cultures (with GFP-expressing OVCAR-3 cells) retained CD16 and CD56 expression at similar levels to freshly sorted cells. In contrast, a population of IL-12-stimulated cells increased CD56 expression, but the majority remained CD16+. Interestingly, the majority of CD62L+ NK cells became CD56bright in response to IL-12. Most strikingly, however, the combination of 4-1BBL + IL-12 produced a predominant population of CD56brightCD16− NK cells, which also express CD62L, from the initial CD56dimCD16+ NK cell population. This shows that upon stimulation with 4-1BBL and IL-12, many CD56dimCD16+ NK cells can both proliferate and switch to become CD56brightCD16−.

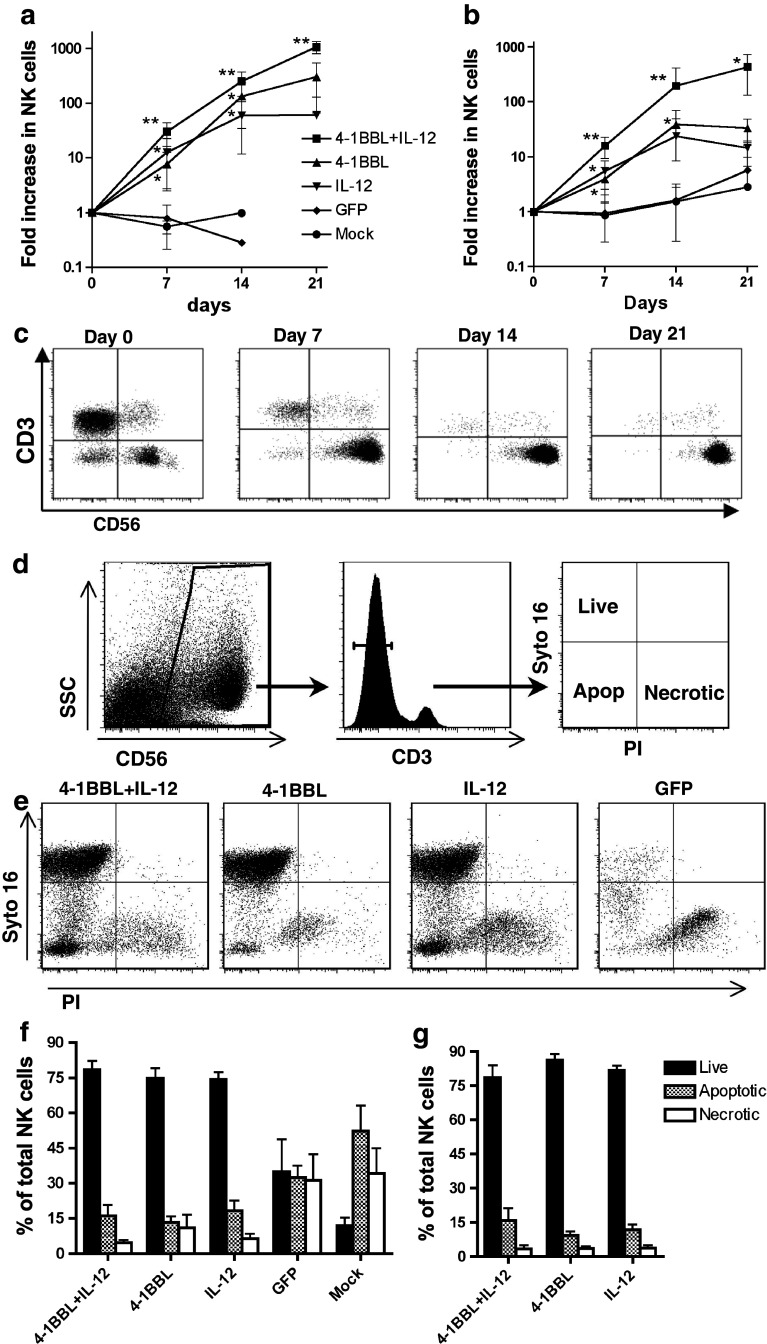

4-1BBL + IL-12 stimulates enhanced long-term NK cell expansion

As 4-1BB stimulation is known to promote extended proliferation and survival of T cells [15, 16], it was of considerable interest to investigate whether the use of 4-1BBL alone or in combination with IL-12 would also support long-term expansion of NK cells. The proliferative response of NK cells over 3 weeks of culture, with re-stimulation at day 14, is shown in Fig. 4a (healthy donors) and 4b (RCC patients).

Fig. 4.

Long-term proliferation and viability of NK cells in response to stimulation. Non-adherent PBMC from 6 healthy donors (a) and 6 RCC patients (b) were cultured for 7 days with OVCAR-3 cells expressing 4-1BBL + IL-12, 4-1BBL, IL-12, GFP or mock-infected, and expansion of the NK cell population was determined. Cultures were then redistributed and IL-2 added to a final concentration of 20U/ml. NK cell number was determined again at day 14 of culture, and cultures re-stimulated with OVCAR-3 pre-infected with the same adenoviral vectors, in the continued presence of IL-2. NK cell number was determined again at day 21 of culture. Symbols indicate mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, paired t test compared with previous time-point. c Analysis of CD3 and CD56 in a representative 4-1BBL + IL-12 stimulated culture, at each time-point. d Gating strategy to determine the viability of NK cells via Syto-16 and PI staining. Cells were first identified using side scatter and CD56 staining and subsequently gated on the CD3− population. NK cells staining Syto16+PI− were deemed live, double negative cells were considered to be apoptotic and Syto16−PI+ cells scored as necrotic. e Representative data for day 7 of culture. Results from 6 healthy donors at day 7 (f) and 14 (g) of culture (mean ± SD)

Most control cultures from healthy donors died out by day 14, and none could be maintained for 3 weeks, although 3/6 control cultures from RCC patients persisted and showed slight expansion of NK cells after 3 weeks. In contrast, NK cells from either healthy donors or RCC patients that were stimulated with 4-1BBL or IL-12 individually at day 0 showed continued proliferation between days 7 and 14. While the 4-1BBL-stimulated cultures lagged behind those stimulated with IL-12 at day 7, they surpassed the IL-12-stimulated cultures by day 14. However, re-stimulation with either 4-1BBL or IL-12 alone at day 14 resulted in no further significant change in NK cell number by day 21. In contrast, NK cells in cultures from either healthy donors or RCC patients stimulated at day 0 with both 4-1BBL + IL-12 not only continued to proliferate between days 7 and 14, but also (following re-stimulation at day 14) showed significant further expansion by day 21.

One mechanism by which 4-1BBL promotes the long-term expansion and maintenance of T cells is via NFκB-mediated upregulation of the anti-apoptotic genes bcl-xL and bfl-1 [33]. We therefore investigated whether 4-1BBL was facilitating the long-term expansion of NK cells through a reduction in cell death, using Syto-16 and PI staining to quantitate live, apoptotic and necrotic NK cells (Fig. 4d). Analysis at day 7 revealed a stark reduction in the viability of control cultures compared with those stimulated with 4-1BBL and/or IL-12, which were all actively proliferating at this stage. However, there was no significant difference between the proportions of live, necrotic and apoptotic NK cells in cultures stimulated with IL-12 alone and those stimulated with 4-1BBL or 4-1BBL + IL-12, either on day 7 (Fig. 4e, f), day 10 (data not shown) or day 14 (Fig. 4g). Thus, the differences in expansion of the NK cell population induced by 4-1BBL, IL-12 or the combination appear to be attributable to differential rates of proliferation, rather than differential cell survival.

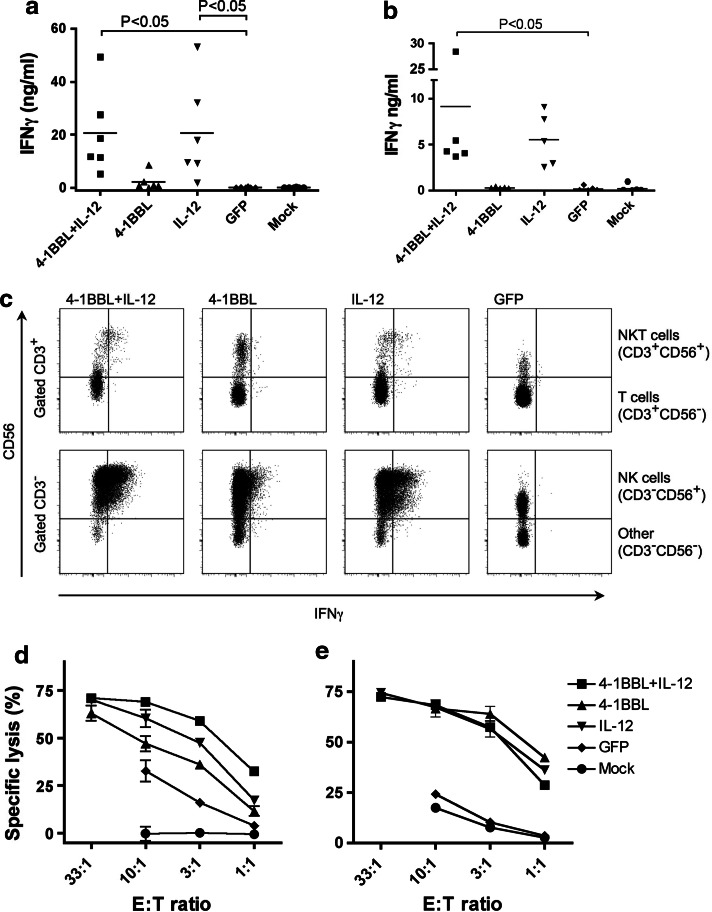

Expanded NK cells produce IFNγ and are cytotoxic

To assess functionality of the expanded NK cells, we examined the production of IFNγ by ELISA. Healthy donor cultures stimulated with 4-1BBL alone showed a small increase in IFNγ production compared with control cultures after 7 days stimulation (Fig. 5a). In contrast, IL-12 alone or with 4-1BBL stimulated far higher levels of IFNγ production. The pattern of IFNγ production was matched by RCC patient-derived cultures, albeit at lower levels than most healthy donors (Fig. 5b). Intracellular IFNγ staining confirmed NK cells to be the main source of IFNγ (Fig. 5c). These data contrast with the recent report of a negative influence of 4-1BBL stimulation on human NK cells [3].

Fig. 5.

Functionality of NK cells in cultures stimulated with 4-1BBL, IL-12 or both. PBMC from healthy donors or RCC patients were stimulated for 7 days with OVCAR-3 cells pre-infected with adenovirus vectors expressing 4-1BBL, IL-12 or GFP as indicated or mock-infected. Cultured lymphocytes from healthy donors (a) or RCC patients (b) were then replated with 1 × 105 cells in 0.2 ml fresh medium and cultured overnight. Production of IFNγ was measured by ELISA (data points indicate different donors). a, b analysed by ANOVA, Dunnett’s multiple comparisons (with the GFP control). c Alternatively, after the 7 days stimulation, cells from healthy donors were cultured for 5 h in the presence of 10 μg/ml brefeldin A, and IFNγ assessed by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. Typical plots are shown, demonstrating IFNγ staining of the lymphocyte population gated as indicated to show T cells (CD3+CD56−), NKT cells (CD3+CD56+) and NK cells (CD3−CD56+). Cytotoxic function was assessed in a standard 5 h chromium release assay with cultured cells from healthy donors (d) and RCC patients (e) as effectors against K562 targets (means ± SD of triplicate wells); data are typical of at least 3 donors

Cytotoxicity of cultures was also tested using the NK-sensitive cell line K562 as a target; representative data from a healthy donor and a RCC patient are shown in Fig. 5d, e, respectively. Cultures stimulated with mock-infected OVCAR-3 cells showed little or no cytotoxicity at any effector:target ratio, although cultures stimulated with Ad-GFP-infected OVCAR-3 cells showed modestly increased target lysis (up to 33%) for some donors. However, cultures from all donors stimulated with 4-1BBL and/or IL-12 showed significantly increased cytotoxicity at all effector:target (E:T) ratios, confirming the cytotoxic capability of the expanded NK cells.

NK cells stimulated with 4-1BBL + IL-12 show enhanced secondary response

Several recent reports have demonstrated increased secondary responses of NK cells following prior activation [34–36]. Continued enhanced NK cell responses to targets, without a requirement for further activation, may be of significant benefit during cancer immunotherapy utilising ex vivo or in vivo NK cell stimulation. We therefore asked whether quiescent NK cells previously stimulated with 4-1BBL + IL-12 would show an enhanced response to unmodified targets, compared with unstimulated NK cells. Non-adherent PBMC from healthy donors were initially stimulated at day 0 with OVCAR-3 cells expressing 4-1BBL + IL-12, as in previous experiments. However, following passage on day 7, no further stimulation or exogenous cytokines were added. At day 21 following initial stimulation, proliferation had ceased, and the expanded NK cells were challenged with either OVCAR-3 or K562 cells, or incubated with no target cells. Intracellular staining for IFNγ, or surface staining for the degranulation marker CD107a, was used to assess the response of NK cells.

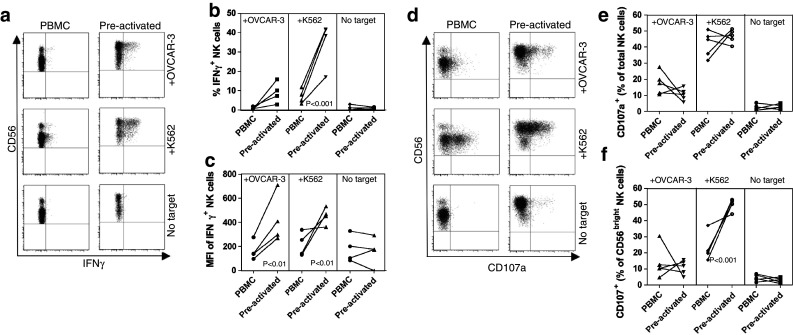

As shown in representative FACS plots in Fig. 6a, and summarised in Fig. 6b, neither fresh NK cells nor those previously activated produced IFNγ in the absence of targets cells. While only 0.9% (±0.7%) of the previously un-stimulated NK cells in PBMC produced IFNγ in response to OVCAR-3, this increased to 9.0% (±5.4%) for NK cells that had previously been stimulated with 4-1BBL + IL-12-expressing OVCAR-3 cells. Un-stimulated NK cells responded more effectively to K562 cells (mean 7.0 ± 3.7% IFNγ+) than to OVCAR-3 cells; however, the proportion induced to produce IFNγ increased significantly (mean 34.6 ± 11.8%) if the NK cells had been previously activated with OVCAR-3 cells expressing 4-1BBL + IL-12. The NK cells that responded to either OVCAR-3 or K562 targets exhibited significantly greater MFI for IFNγ if they had been pre-activated (Fig. 6c). Thus, prior stimulation with 4-1BBL + IL-12 not only increased the proportion of NK cells capable of secreting IFNγ, but also resulted in increased efficiency of IFNγ production upon secondary encounter with target cells.

Fig. 6.

Enhanced secondary response to targets of NK cells previously stimulated with 4-1BBL + IL-12. PBMC from healthy donors were co-cultured for 7 days with OVCAR-3 cells pre-infected with adenovirus vectors expressing 4-1BBL + IL-12. The lymphocyte populations were then passaged and maintained for a further 14 days without further stimulation. These pre-stimulated cultures containing an expanded population of NK cells or unstimulated PBMC from the same donors (which had been cryopreserved) were then stimulated with either (uninfected) OVCAR-3 or K562 cells or with no target cells as indicated, for 6 h. a Shows representative plots of intracellular IFNγ staining versus CD56 gated on CD3−CD56+ lymphocytes. Data from all 4 donors are summarised showing the proportion (b) and mean fluorescent intensity (c) of NK (CD3−CD56+) cells expressing IFNγ, following incubation with the indicated targets. As an indicator of cytotoxicity, degranulation of the NK cells was monitored via CD107a staining; d shows representative plots of CD107a versus CD56 (gated on CD3−CD56+ cells); e, f show data from all 5 donors, indicating CD107a+ cells as a per cent of total NK (CD3−CD56+) cells (e), and as a per cent of CD56bright NK cells (f). Data analysed by ANOVA, Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test

As seen in Fig. 6a, d, the majority of pre-activated NK cells remained CD56bright after resting. Since CD56bright NK cells are characteristically less cytotoxic than CD56dim NK cells, we also evaluated the cytotoxic potential of the pre-activated cells by monitoring CD107a (LAMP-1) mobilisation, to indicate degranulation in response to target cells. When considering the entire NK cell population (CD3−CD56+), there was no significant change between non-stimulated cells in PBMC, and the pre-activated population, in the proportion of NK cells degranulating in response to targets (17.5 ± 6.9% vs. 10.5 ± 3.8% in response to OVCAR-3, 42.0 ± 7.9% vs. 46.7 ± 4.2% in response to K562; Fig. 6d, e). However, pre-activated CD56bright cells (Fig. 6f) showed a significantly higher rate of response to K562 targets (50.0 ± 3.6%), compared with CD56bright cells in PBMC (22.9 ± 8.2%).

Discussion

These experiments are the first to study the responses of human NK cells to a combination of 4-1BBL and IL-12 and add to the limited data available regarding the response of human NK cells to 4-1BB stimulation. Whereas 4-1BBL or IL-12 alone could stimulate some short-term proliferation, the combination induced significantly greater proliferation, and only the combination could extend proliferation beyond 2 weeks with repeated stimulation. The strong response to 4-1BBL + IL-12 was seen with isolated NK cells, and importantly, the benefit of the combination was seen with PBMC from both healthy donors and cancer patients.

Within 7 days, the majority of NK cells expanded in response to 4-1BBL + IL-12 in our study were CD56bright, and remained so after 3 weeks, whether restimulated (Fig. 4c) or rested (Fig. 6a and d). The majority of NK cells in PBMC are CD56dim, a subset which as a whole is considered poorly proliferative [4, 6], although greater proliferative potential of the CD56dimCD62L+ subpopulation was recently described [11]. We therefore investigated the response of isolated CD56dim NK cells to OVCAR-3 cells expressing 4-1BBL + IL-12 and found (Fig. 3d) that isolated CD56dimCD16+ NK cells proliferated to an extent comparable to total NK cells (Fig. 3a). Simultaneously, CD56 was upregulated and CD16 downregulated, so that the majority became CD56brightCD16− (Fig. 3e). The expanded NK cell population also displayed further key phenotypic characteristics of the CD56bright subset (including upregulated CCR7, CD62L and CXCR3, Fig. 2d–g), and they were efficient producers of IFNγ (Figs. 5c, 6a). The clear separation of phenotypic populations evident, e.g., in Fig. 3e, and the stability of the change over at least 2 weeks in the absence of stimulation (Fig. 6), suggest this to be a stable switch in phenotype rather than a transient, activation-induced upregulation of CD56. This observation that CD56dim NK cells can convert to a CD56bright phenotype (Fig. 3e) challenges the widely held view of a linear, unidirectional differentiation pathway from CD56bright NK cells to the more mature CD56dim subset [4, 9, 10]. However, since the pre-activated CD56bright NK cells showed significantly greater cytotoxicity against target K562 cells than those in untreated PBMC, at a level more characteristic of CD56dim NK cells, they do not appear to have reverted to a state identical to the majority of CD56bright NK cells in PBMC. Furthermore, KIR expression is characteristic of the CD56dim subset, but we observed no reduction in KIR expression (Fig. 2i, j) coincident with the shift to a predominantly CD56bright population. Expression of CD62L was recently reported to identify a subpopulation of CD56dim cells with relatively high proliferation and the ability both to secrete cytokines and exhibit cytotoxicity in response to target cells [11]. Our data suggest there may similarly be subpopulations of CD56bright cells with different histories and functions, and a proportion of CD56bright NK cells in vivo could represent a population that has experienced activation via 4-1BBL, perhaps constituting a “NK memory” population. Thus, CD56bright and CD56dim NK cells should not be regarded exclusively as sequential stages of a linear differentiation pathway; we have identified a combination of stimuli that enable some CD56dim cells to proliferate and re-acquire many characteristics of the CD56bright subset. Further investigation of the roles and interconversions of NK cell subpopulations is of significant fundamental and practical importance for the understanding of NK cell biology and their therapeutic exploitation.

In contrast to murine NK cells, human NK cells do not express 4-1BB in response to IL-2 stimulation without further activation signals [2, 25]; one stimulus previously demonstrated to induce 4-1BB expression on NK cells was ligation of CD16 by immobilised Fc fragments (but not by non-immobilised antibody)[25]. Here, we have shown that IL-12 can induce 4-1BB expression on isolated NK cells, but only in the presence of target cells (Fig. 3c). These data suggest 4-1BB expression by NK cells requires initial activation and concomitant extraneous signals. Unsurprisingly, 4-1BBL-expressing OVCAR-3 cells could not directly induce 4-1BB expression on isolated NK cells, but they could do so in the presence of other non-adherent PBMC, indicating a role for “help” (possibly secretion of IL-12 or other cytokines) from another, directly 4-1BBL-responsive cell type. Physiologically, 4-1BBL expression is predominantly restricted to highly activated APC including B cells, dendritic cells and macrophages [37], which also secrete inflammatory cytokines including IL-12, providing a physiological context in which NK cells could encounter the combination of signals studied here. A 4-1BBL-mediated role for γδT cells in activation of anti-tumour function of NK cells has also recently been demonstrated [38].

The NK cells expanded in co-cultures with carcinoma cells expressing 4-1BBL and/or IL-12 demonstrated cytolytic activity towards K562 targets and IFNγ production. While our results agree with those of Campana’s group [2, 39] in indicating a potent ability of 4-1BBL to stimulate proliferation and functional activation of human NK cells, they contrast with the recent paper of Baessler et al. [3], who reported that 4-1BBL expression on target cells was inhibitory for IFNγ production or cytotoxicity of human NK cells (although activatory for murine NK cells). To reconcile these contrasting findings, we suggest that while 4-1BBL can promote expansion of human NK cells, ultimately increasing their capability to respond to targets with IFNγ-production or cytotoxicity as demonstrated here, our results do not exclude an immediate inhibitory effect on triggering of effector functions. An immediate inhibitory effect of 4-1BB engagement might downregulate effector functions on NK cells during their initial expansion phase and physiologically might help to protect activated, 4-1BBL-expressing APCs from NK-mediated cytotoxicity.

The capacity to mount an enhanced or more rapid “memory” response after the initial response has waned has only recently been associated with NK cells [34–36]. The data reported here show human NK cells previously activated with 4-1BBL + IL-12 display enhanced IFNγ-production in response to target cells, relative to naïve NK cells. The pre-activated CD56bright NK cells also showed enhanced cytotoxic function, relative to the CD56bright population in PBMC. This is the first demonstration that 4-1BBL + IL-12 can promote enhanced secondary NK cell responses and is among the first reports of an enhanced secondary response by human NK cells. The increased proportion of NK cells that secrete IFNγ or degranulate during the secondary response may be due to a preferential expansion of NK cells with appropriate combinations of activatory and inhibitory receptors for target recognition and consequent activation [40], although analysis of KIR2DL1/KIR2DS1 (CD158a) and KIR3DL1 (CD158e) showed no major or consistent change in frequency among the expanded NK population. However, NKG2D (which is implicated in tumour recognition) was increased ~2-fold following initial stimulation (Fig. 2h) and remained 1.5-fold elevated after resting (data not shown) relative to unstimulated NK cells in PBMC (P ≤ 0.05, paired t test). Further studies will be required to address the receptor usage and target selectivity (i.e. normal vs. cancer cells) of NK cells activated by carcinoma cells expressing 4-1BBL + IL-12. Although CD56bright NK cells are classically less cytotoxic than CD56dim NK cells, the predominantly CD56bright NK cells resulting from prior stimulation with 4-1BBL + IL-12 showed similar cytotoxic potential to the predominantly CD56dim NK cells from PBMC (Fig. 6d, e). Hence, the phenotypic switch to, and preferential expansion of CD56bright NK cells with enhanced cytokine production has not come at the expense of cytotoxicity; indeed, for K562 although not OVCAR-3 targets, it was apparent that the relative cytotoxic potential of CD56bright NK cells was increased.

These results support the concept of treating cancer patients by adoptive transfer of NK cells expanded ex vivo using allogeneic cancer cell lines expressing 4-1BBL + IL-12. Alternatively, the viral vectors used in this study might also be applicable for delivery into inoperable tumours in patients, with potential to activate both NK and T cells in situ. It is encouraging that NK cells from patients with renal or ovarian cancer could also be activated and expanded by these signals, indicating a potential for therapeutic application. Clinical trials of agonistic anti-4-1BB antibodies have commenced; initial results from a phase I clinical trial have been promising [19], and results from a phase II trial in patients with melanoma (http://clinicaltrials.gov, trial identifier NCT00612664) are eagerly awaited. The data presented here clearly support the clinical potential for NK cell stimulation via 4-1BB and suggests that the combination of 4-1BBL + IL-12 warrants further investigation as an immunotherapeutic strategy.

Acknowledgments

ACD was supported by a University of Birmingham Medical School PhD studentship. We thank Professor D. Luesley for supply of ascitic fluid from ovarian carcinoma patients.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Urbani E, Perruccio K, Shlomchik WD, Tosti A, Posati S, Rogaia D, Frassoni F, Aversa F, Martelli MF, Velardi A. Effectiveness of donor natural killer cell alloreactivity in mismatched hematopoietic transplants. Science. 2002;295:2097–2100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Imai C, Iwamoto S, Campana D. Genetic modification of primary natural killer cells overcomes inhibitory signals and induces specific killing of leukemic cells. Blood. 2005;106:376–383. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baessler T, Charton JE, Schmiedel BJ, Grunebach F, Krusch M, Wacker A, Rammensee HG, Salih HR. CD137 ligand mediates opposite effects in human and mouse NK cells and impairs NK-cell reactivity against human acute myeloid leukemia cells. Blood. 2010;115:3058–3069. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-227934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Caligiuri MA. The biology of human natural killer-cell subsets. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:633–640. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(01)02060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wendt K, Wilk E, Buyny S, Buer J, Schmidt RE, Jacobs R. Gene and protein characteristics reflect functional diversity of CD56dim and CD56bright NK cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:1529–1541. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vivier E, Tomasello E, Baratin M, Walzer T, Ugolini S. Functions of natural killer cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:503–510. doi: 10.1038/ni1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poli A, Michel T, Theresine M, Andres E, Hentges F, Zimmer J. CD56bright natural killer (NK) cells: an important NK cell subset. Immunology. 2009;126:458–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.03027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagler A, Lanier LL, Cwirla S, Phillips JH. Comparative studies of human FcRIII-positive and negative natural killer cells. J Immunol. 1989;143:3183–3191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan A, Hong DL, Atzberger A, Kollnberger S, Filer AD, Buckley CD, McMichael A, Enver T, Bowness P. CD56bright human NK cells differentiate into CD56dim cells: role of contact with peripheral fibroblasts. J Immunol. 2007;179:89–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beziat V, Descours B, Parizot C, Debre P, Vieillard V. NK cell terminal differentiation: correlated stepwise decrease of NKG2A and acquisition of KIRs. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Juelke K, Killig M, Luetke-Eversloh M, Parente E, Gruen J, Morandi B, Ferlazzo G, Thiel A, Schmitt-Knosalla I, Romagnani C. CD62L expression identifies a unique subset of polyfunctional CD56dim NK cells. Blood. 2010;116:1299–1307. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-253286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez-Verges S, Milush JM, Pandey S, York VA, Arakawa-Hoyt J, Pircher H, Norris PJ, Nixon DF, Lanier LL. CD57 defines a functionally distinct population of mature NK cells in the human CD56dimCD16 + NK-cell subset. Blood. 2010;116:3865–3874. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-282301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu J, Mao HC, Wei M, Hughes T, Zhang J, Park IK, Liu S, McClory S, Marcucci G, Trotta R, Caligiuri MA. CD94 surface density identifies a functional intermediary between the CD56bright and CD56dim human NK-cell subsets. Blood. 2010;115:274–281. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-215491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alderson MR, Smith CA, Tough TW, Davis-Smith T, Armitage RJ, Falk B, Roux E, Baker E, Sutherland GR, Din WS. Molecular and biological characterization of human 4-1BB and its ligand. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:2219–2227. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cannons JL, Lau P, Ghumman B, DeBenedette MA, Yagita H, Okumura K, Watts TH. 4-1BB ligand induces cell division, sustains survival, and enhances effector function of CD4 and CD8 T Cells with similar efficacy. J Immunol. 2001;167:1313–1324. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Habib-Agahi M, Phan TT, Searle PF. Co-stimulation with 4-1BB ligand allows extended T-cell proliferation, synergizes with CD80/CD86 and can reactivate anergic T cells. Int Immunol. 2007;19:1383–1394. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melero I, Shuford WW, Newby SA, Aruffo A, Ledbetter JA, Hellstrom KE, Mittler RS, Chen L. Monoclonal antibodies against the 4-1BB T-cell activation molecule eradicate established tumors. Nat Med. 1997;3:682–685. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melero I, Bach N, Hellstrom KE, Aruffo A, Mittler RS, Chen L. Amplification of tumor immunity by gene transfer of the co-stimulatory 4-1BB ligand: synergy with the CD28 co-stimulatory pathway. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1116–1121. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199803)28:03<1116::AID-IMMU1116>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sznol M, Hodi FS, Margolin K, McDermott DF, Emstoff M, Kirkwood J, Wojtaszek C, Feltquate D, Logan T (2008) Phase I study of BMS-663513, a fully human anti-CD137 agonist monoclonal antibody, in patients (pts) with advanced cancer (CA). J Clin Oncol 26(suppl) (abstr 3007). http://www.asco.org/ascov2/Meetings/Abstracts?&vmview=abst_detail_view&confID=55&abstractID=35273

- 20.Melero I, Johnston JV, Shufford WW, Mittler RS, Chen L. NK1.1 cells express 4-1BB (CDw137) costimulatory molecule and are required for tumor immunity elicited by anti-4-1BB monoclonal antibodies. Cell Immunol. 1998;190:167–172. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen SH, Pham-Nguyen KB, Martinet O, Huang Y, Yang W, Thung SN, Chen L, Mittler R, Woo SL. Rejection of disseminated metastases of colon carcinoma by synergism of IL-12 gene therapy and 4-1BB costimulation. Mol Ther. 2000;2:39–46. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinet O, Ermekova V, Qiao JQ, Sauter B, Mandeli J, Chen L, Chen SH. Immunomodulatory gene therapy with interleukin 12 and 4-1BB ligand: long- term remission of liver metastases in a mouse model. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:931–936. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.11.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu D, Gu P, Pan PY, Li Q, Sato AI, Chen SH. NK and CD8 + T cell-mediated eradication of poorly immunogenic B16-F10 melanoma by the combined action of IL-12 gene therapy and 4-1BB costimulation. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:499–506. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang JH, Zhang SN, Choi KJ, Choi IK, Kim JH, Lee MG, Kim H, Yun CO. Therapeutic and tumor-specific immunity induced by combination of dendritic cells and oncolytic adenovirus expressing IL-12 and 4-1BBL. Mol Ther. 2010;18:264–274. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin W, Voskens CJ, Zhang X, Schindler DG, Wood A, Burch E, Wei Y, Chen L, Tian G, Tamada K, Wang LX, Schulze DH, Mann D, Strome SE. Fc-dependent expression of CD137 on human NK cells: insights into “agonistic” effects of anti-CD137 monoclonal antibodies. Blood. 2008;112:699–707. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-122465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferlay J, Parkin DM, Steliarova-Foucher E. Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2008. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:765–781. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reeves DJ, Liu CY. Treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;64:11–25. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-0983-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rini BI. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma: many treatment options, one patient. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3225–3234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.9836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sparrow RL, Tippett E. Discrimination of live and early apoptotic mononuclear cells by the fluorescent SYTO 16 vital dye. J Immunol Methods. 2005;305:173–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wendel M, Galani IE, Suri-Payer E, Cerwenka A. Natural killer cell accumulation in tumors is dependent on IFN-gamma and CXCR3 ligands. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8437–8445. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li K, Mandai M, Hamanishi J, Matsumura N, Suzuki A, Yagi H, Yamaguchi K, Baba T, Fujii S, Konishi I. Clinical significance of the NKG2D ligands, MICA/B and ULBP2 in ovarian cancer: high expression of ULBP2 is an indicator of poor prognosis. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:641–652. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0585-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyons AB. Analysing cell division in vivo and in vitro using flow cytometric measurement of CFSE dye dilution. J Immunol Methods. 2000;243:147–154. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(00)00231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee H-W, Park S-J, Choi BK, Kim HH, Nam K-O, Kwon BS. 4-1BB promotes the survival of CD8 + T lymphocytes by increasing expression of Bcl-xL and Bfl-1. J Immunol. 2002;169:4882–4888. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper MA, Elliott JM, Keyel PA, Yang L, Carrero JA, Yokoyama WM. Cytokine-induced memory-like natural killer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:1915–1919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813192106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun JC, Beilke JN, Lanier LL. Adaptive immune features of natural killer cells. Nature. 2009;457:557–561. doi: 10.1038/nature07665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horowitz A, Behrens RH, Okell L, Fooks AR, Riley EM. NK cells as effectors of acquired immune responses: effector CD4 + T cell-dependent activation of NK cells following vaccination. J Immunol. 2010;185:2808–2818. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Croft M. Co-stimulatory members of the TNFR family: keys to effective T-cell immunity? Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:609–620. doi: 10.1038/nri1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maniar A, Zhang X, Lin W, Gastman BR, Pauza CD, Strome SE, Chapoval AI. Human gammadelta T lymphocytes induce robust NK cell-mediated antitumor cytotoxicity through CD137 engagement. Blood. 2010;116:1726–1733. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-234211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujisaki H, Kakuda H, Shimasaki N, Imai C, Ma J, Lockey T, Eldridge P, Leung WH, Campana D. Expansion of highly cytotoxic human natural killer cells for cancer cell therapy. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4010–4017. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yawata M, Yawata N, Draghi M, Partheniou F, Little AM, Parham P. MHC class I-specific inhibitory receptors and their ligands structure diverse human NK-cell repertoires toward a balance of missing self-response. Blood. 2008;112:2369–2380. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]