Abstract

The programmed death-1 (PD-1) molecule is mainly expressed on functionally “exhausted” CD8+ T cells, dampening the host antitumor immune response. We evaluated the ratio between effective and regulatory T cells (Tregs) and PD-1 expression as a prognostic factor for operable breast cancer patients. A series of 218 newly diagnosed invasive breast cancer patients who had undergone primary surgery at Ruijin Hospital were identified. The influence of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes, FOXP3+ (Treg cell marker), and PD-1+ immune cell counts on prognosis was analyzed utilizing immunohistochemistry. Both PD-1+ immune cells and FOXP3+ Tregs counts were significantly associated with unfavorable prognostic factors. In bivariate, but not multivariate analysis, high tumor infiltrating PD-1+ cell counts correlated with significantly shorter patient survival. Our results suggest a prognostic value of the PD-1+ immune cell population in such breast cancer patients. Targeting the PD-1 pathway may be a feasible approach to treating patients with breast cancer.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-014-1519-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Breast cancer, PD-1, Regulatory T cells, Immune evasion, Cancer immunotherapy

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in women worldwide, and traditionally not viewed as an immunogenic disease. However, a large body of evidence has shown the existence of immune defects in breast cancer patients, with heavy tumor infiltration of immune cells being frequently observed [1, 2]. These immune cells are mainly tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and are considered to represent a local tumor immune host response. The type, density, and location of TILs within the tumor have shown to be predictors of patients survival in addition to histopathological methods currently used to classify early stage breast cancer [3–5].

The majority of TILs are CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), which are a major effector cell type, and prominent CTLs infiltration has been linked to a better prognosis in breast cancer [3, 6]. Various other suppressor immune cells are also recruited and infiltrated into the tumor microenvironment, probably playing an important role in antitumor immune response and tumor progression [5, 7, 8]. It has been demonstrated that, as a major immune suppressive element, regulatory T cells (Tregs) infiltrate tumors and impede the tumor immune response. FOXP3, a forkhead family transcription factor, has been considered the most specific marker to identify Treg cells [9]. Furthermore, these effector cells may become tolerant or their function “exhausted” through such mechanisms as inappropriate stimulation or chronic antigen exposure. Ample evidence exists that the coinhibitory checkpoint receptor, programmed death-1 (PD-1), represents an exhausted status of T cells [10, 11]. PD-1 is expressed on chronically activated T cells, inhibiting their cytokine production through interaction with its ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2. This interaction also facilitates Treg-induced suppression of T effector cells, further dampening the antitumor immune response [7, 12, 13].

Encouraging early clinical results using blocking agents against components of the PD-1 pathway have validated its importance as a target for cancer immunotherapy [14, 15]. Notably, objective and durable responses were achieved in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which is notoriously resistant to immunotherapy [11, 14, 16]. Of note, 36 % of NSCLC patients whose tumors expressed PD-L1 (defined as >5 %) demonstrated an objective response while none whose tumors did not express PD-L1 responded [14, 17]. Thus, PD-L1 expression has been proposed as a biomarker for selecting candidate patients for PD-1 axis inhibition [18]. Accordingly, it would be of interest to evaluate the potential of linking the expression level of PD-1 to the response to immunotherapeutic strategies in the clinical settings.

PD-1-positive T lymphocytes and Tregs have been shown to co-infiltrate tumors of high-risk breast cancer patients [19]. An inverse correlation between the expression levels of PD-1 and prognosis has been reported in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [20], while the predictive value of PD-1 expression in other malignancies, including breast cancer, has rarely been investigated.

Therefore, our aim in this study was to analyze the influence of CTLs, Tregs, and PD-1+ immune cell density on breast cancer patient prognosis and determine which of the immunosuppression mechanisms seem most important [21]. Relationships between immune cells infiltrated in the microenvironment of breast cancer and patient outcome were retrospectively investigated. Both tumor-associated immune cell PD-1 expression and the ratio of CD8+ to PD-1+ cells were shown in this study to be significant prognostic indicators.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

A series of 218 patients who had been diagnosed with and undergone primary surgery for unilateral invasive breast cancer at Ruijin Hospital (Shanghai, People’s Republic of China) between 2004 and 2008 were identified. Patients were selected based on availability of suitable formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue and complete clinicopathologic and follow-up data. None had distant metastatic disease at diagnosis or had received prior anticancer therapy. Written informed consent for research was obtained from all patients with the approval of the Ethics Committee of Ruijin Hospital.

Clinical and pathological features

The original pathological diagnosis was confirmed by breast pathologists. Pathologic features were collected by review of patient files. Clinicopathologic features including age, tumor size, histologic grade, histologic subtype, lymph node status, pathological TNM staging, ER, PR, and HER2 status were investigated. Only those showed 3+ for HER2 by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining were considered HER2-positive. Histologic grading was carried out using the modified Bloom and Richardson grading system [22].

Treatment and follow-up

All patients received standard surgical treatment of either mastectomy or wide local excision followed by radiotherapy. Standard adjuvant systemic therapies were administrated. Patients were followed up at 3-month intervals initially, then every 6 months or annually.

Overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) data were obtained for each patient. OS was defined as time from date of surgery until death or last follow-up. DFS was defined as time elapsed from date of surgery to date of the first event (locoregional recurrence and/or distant recurrence, whichever came first). Follow-up was completed on October 15, 2012, and duration of follow-up was calculated from date of surgery to date of cancer recurrence, last follow-up, or death.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining for CD8, FOXP3, and PD-1

Archived FFPE tissues were used. All cases were histologically reviewed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. A single representative paraffin tumor block for each patient was chosen; 10 patients without available sequential sections including both tumor and tissue surrounding the tumor were thus excluded.

Sequential 5 μm specimens were collected on super defrosted slides, then baked at 60 °C for 1 h before IHC staining. IHC staining was performed by standard ABC method using the Vectastain Elite ABC kit from Vector Laboratory (cat. PK-6102).

Tissue sections were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated through graded ethanol to distilled water. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched by 0.3 % hydrogen peroxidase for 15 min. Antigen retrieval was performed by heating slides in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) (Dako, S1699) with a regular cooking steamer for 30 min.

After serial blocking with 10 % normal horse serum, sections were incubated with primary monoclonal mouse antihuman antibody against CD8 (Dako, clone C8/144B, M7103), FOXP3 (Abcam, ab20034, clone 236A/E7), or PD-1 (Abcam, ab52587, clone NAT) overnight at 4 °C.

Biotinylated horse anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Vectastain Elite ABC kit, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) were added the following day, incubated for 30 min at room temperature, and tertiary reagent applied according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Antigen detection was performed by color reaction with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Dako, K3468).

Finally, slides were counterstained in hematoxylin, dehydrated through ascending alcohols to xylene, and mounted.

Positive and negative controls were carried out on FFPE lymph node tissues using corresponding monoclonal antibody and mouse isotope IgG.

Evaluation of immune cell infiltration

Two breast pathologists (Xiaochun Fei and Fei Yuan) examined the H&E- and IHC-stained slides and counted the number of lymphoid infiltrates. Both were blinded as to the clinicopathologic characteristics and patient outcome.

Mononuclear immune cells infiltration was evaluated on H&E-stained sections. A standard grading system for semiquantitative scoring of lymphocytic infiltration was used to evaluate these H&E-stained sections [23]. Infiltration intensity was graded as absent (0), mild (score of 1, a few scattered lymphocytes), moderate (2, focal infiltrating immune cells), or marked (3, diffuse infiltration mimicking a lymphoid organ).

At least five independent high-powered microscopic fields (400× HPF), representing the densest lymphocytic infiltrates, were selected for each IHC-stained sample. The numbers of positively stained cells present within tumor nests and immediately adjacent stroma (in direct contact with tumor cells) were manually counted. Positive cells in distant stroma not touching tumor cells (defined as distance between positive cells and tumor nests being more than the size of one tumor cell) were disregarded. Cases in which scores differed between the two pathologists were reexamined and a consensus reached.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 16.0 statistical software (SPSS, Chicago, IL). The relationship among immunoreactive markers and the association between (high or low) numbers of tumor-infiltrating cells and clinicopathologic characteristics were analyzed by chi-square tests, Spearman’s rank correlation or Mann–Whitney U test where appropriate. T test was used to compare FOXP3+ cells numbers in PD-1 expression high and low groups. The log-rank test was used for univariate analyses, and cumulative survival curves were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method. The influence of PD-1+ immune cells on survival was evaluated in multivariate analyses by Cox proportional hazards regression model. Two-sided p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical profiles of patients

Clinicopathologic characteristics are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. The average patient age was 57.6 years [range 31–85; standard deviation (SD) 12.3 years), and mean tumor size was 2.4 cm (range 0.8–6.0; SD 0.9 cm). The 208 patients were categorized into two groups for further analysis, using median value of age (56 years) and tumor size (2.1 cm) as cutoffs, respectively. There were 76 patients (36.5 %) with stage I, 101 (48.6 %) with stage II, and 31 (14.9 %) with stage III disease. Histological subtypes were 184 with invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), 16 with invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC), and 8 with others.

Clinical outcome

Patients were followed for 0.67–8.52 years, with a median of 6 years. Mean follow-up was 5.63 years, during which 32 (15.4 %) patients had local, regional-, and/or distant recurrences, of whom 6 were alive at the end of the study.

At last follow-up, 32 patients (15.4 %) had died, including 26 (12.5 %) from breast cancer at a median of 2.98 years following surgery (range 0.67–5.61). Among the 176 (84.6 %) patients still alive at last follow-up, median duration of follow-up was 6.71 years (range 4.29–8.52).

OS and DFS rates [standard error (SE), patient number still at risk) of patients at 3, 5, and 7 years following surgery are shown in Supplemental Table 2.

Immunohistochemical characteristics

A total of 208 tumors were examined after exclusion of uninformative slides. Of these, mononuclear immune cell tumor infiltration was absent in 10 (4.8 %) specimens, focally present in 62 (29.8 %), moderately in 104 (50.0 %), and markedly in 32 (15.4 %). Lymphocytes infiltrating within tumor beds presented in a diffuse pattern, while those in surrounding tissues were significantly more abundant and tended to form lymphoid aggregates.

Infiltration pattern, frequency, and localization of CD8+, PD-1+ and FOXP3+ cells

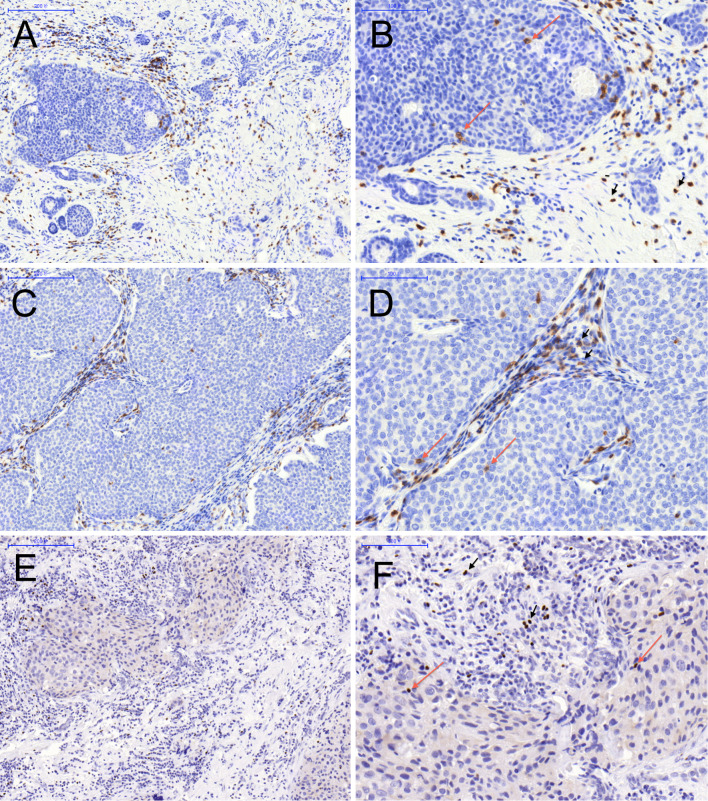

There were more IHC-stained cells in peritumoral areas when compared to those within tumor nests (Fig. 1). Ratios of CD8+, PD-1+, and FOXP3+ cells varied substantially among tumor samples.

Fig. 1.

Representative tumor tissue infiltrated by CD8+, PD-1+, and FOXP3+ cells depicting the localization pattern: intratumoral (red arrow), adjacent, and distant stromal (black arrow head). CD8+ (a, b) and PD-1+ (c, d) cells displayed membranous staining pattern, FOXP3+ (e, f) lymphocytes exhibited distinct nuclear staining, a, c, e ×100 and b, d, f ×200

CD8+ and PD-1+ lymphocytes displayed a membranous staining pattern, while FOXP3+ cells exhibited distinct nuclear staining, consistent with its expected transcription function (Fig. 1). No tumor cell expression of FOXP3 was demonstrated. Expression levels of CD8, PD-1, and FOXP3 in tumor-associated immune cells ranged from weak to intense.

Results were expressed as mean, median, and interquartile numbers of positive cells for one computerized 400× microscopic field (0.0768 mm2/field). Representative images (Fig. 1) and statistics of IHC variables are shown (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of IHC variables

| Variable | Mean | Lower IQ | Median | Higher IQ | Rangea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD8+ | 13.98 | 4.40 | 7.80 | 15.35 | 0–173 |

| FOXP3+ | 5.56 | 0.73 | 2.70 | 6.28 | 0–71 |

| PD-1+ | 7.59 | 0.45 | 2.10 | 7.00 | 0–118 |

a Cell count per field (cells/0.0768 mm2) IQ interquartile

Correlation between number of CD8+ CTLs, FOXP3+ Tregs, and PD-1+ immune cells

Next investigated was the correlation between CD8+ TIL, PD-1+ immune cells, and FOXP3+ Tregs infiltration in tumors, and vise versa. Highly significant correlations were shown between expressions of PD-1 in tumor-associated immune cells and FOXP3+ Tregs and CD8+ CTLs (r 2, 0.385 and 0.385, respectively, both p < 0.001) as shown by Spearman’s rank correlation.

Notably, the majority of patients within the high PD-1 expression group (72/104, 69.2 %) also possessed more FOXP3+ cells (mean ± SD: 8.79 ± 12.13 vs 2.32 ± 2.99, p < 0.001). In addition, there was a significant correlation between FOXP3+ Tregs infiltration and CD8 expression in TIL (r 2 = 0.154; p = 0.027).

Correlation of PD-1, CD8, and FOXP3 expressions in TIL with clinicopathologic features

Infiltrating densities of CTLs, Tregs, and PD-1+ cells were categorized as high or low in relation to their medians. Comparison of clinical and pathologic features by FOXP3 and PD-1 expression for the 208 patients is shown in Table 2. Both PD-1+ cells and FOXP3+ Tregs correlated positively with high histologic grade and later pathologic stage (both p < 0.001 and p = 0.006, respectively). Tumor-associated FOXP3+ Tregs were found also to be associated with progesterone receptor (PR) status and ER/PR/HER2 (triple)-negativity, although this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.061 and 0.081, respectively) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation of Foxp3+ Treg and PD-1+ immune cells with the clinicopathologic parameters

| Variable | Foxp3 | PD-1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (%) | High (%) | p | Low (%) | High (%) | p | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| ≤55 | 53 (51.0) | 51 (49.0) | 0.890 | 48 (46.2) | 56 (53.8) | 0.332 |

| >55 | 51 (49.0) | 53 (51.0) | 56 (53.8) | 48 (46.2) | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||||

| ≤2 | 51 (49.0) | 53 (51.0) | 0.890 | 53 (51.0) | 51 (49.0) | 0.890 |

| >2 | 53 (51.0) | 51 (49.0) | 51 (49.0) | 53 (51.0) | ||

| Histological grade | ||||||

| I, II | 96 (61.5) | 60 (38.5) | <0.001 | 94(81.9) | 62 (50.0) | <0.001 |

| III | 8 (15.4) | 44 (84.6) | 10 (18.1) | 42 (50.0) | ||

| TNM stage | ||||||

| I, II | 96 (54.2) | 81 (45.8) | 0.006 | 96 (54.2) | 81 (45.8) | 0.006 |

| III | 8 (25.8) | 23 (74.2) | 8 (25.8) | 23 (74.2) | ||

| Lymph node status | ||||||

| Negative | 75 (52.1) | 69 (47.9) | 0.453 | 81 (56.2) | 63 (43.8) | 0.010 |

| Positive | 29 (45.3) | 35 (54.7) | 23 (35.9) | 41 (64.1) | ||

| ER status | ||||||

| Negative | 19 (40.4) | 28 (59.6) | 0.184 | 13 (27.7) | 34 (72.3) | <0.001 |

| Positive | 85 (52.8) | 76 (47.2) | 91 (56.5) | 70 (43.5) | ||

| PR status | ||||||

| Negative | 31 (40.8) | 45 (59.2) | 0.061 | 23 (30.3) | 53 (69.7) | <0.001 |

| Positive | 73 (55.3) | 59 (44.7) | 81 (61.4) | 51 (38.6) | ||

| HER2 status | ||||||

| Negative | 97 (51.6) | 91 (48.4) | 0.239 | 98 (52.1) | 90 (47.9) | 0.098 |

| Positive | 7 (35.0) | 13 (65.0) | 6 (30.0) | 14 (70.0) | ||

| TNBC | ||||||

| No | 89 (53.3) | 78 (46.7) | 0.081 | 95 (56.9) | 72 (43.1) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 15 (36.6) | 26 (63.4) | 9 (22.0) | 32 (78.0) | ||

| TIL grade | ||||||

| Low (0–1) | 52 (72.2) | 20 (27.8) | <0.001 | 54 (75.0) | 18 (25.0) | <0.001 |

| High (2–3) | 52 (38.2) | 84 (61.8) | 50 (36.8) | 86 (63.2) | ||

Pearson’s chi square-test

Bold values are statistically significant (p <0.05)

Italic values are p values between 0.05 and 0.1, indicating a trend, though not reaching statistical significance

ER estrogen receptor, PR progesterone receptor, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor-2, TNBC triple-negative breast cancer, TIL tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

On the other hand, numbers of PD-1+ cells were significantly inversely correlated with both ER and PR status (p < 0.001). In addition, higher density infiltration of PD-1+ immune cells also correlated significantly with triple-negative disease (p < 0.001). Furthermore, there was a moderately positive correlation between number of PD-1+ cells and lymph node status (p = 0.010). Finally, patients with greater infiltrating PD-1+ immune cells seemed more likely to have HER2-positive tumors (p = 0.098) (Table 2).

No significant associations were identified between PD-1+ immune cells or FOXP3+ Treg infiltration and patient age or tumor size. Also, CTLs did not associate with clinicopathologic features except for a negative correlation with patient age (p = 0.008) (Supplemental Table 3).

Survival analysis

Association with patient outcome by univariate assessment

On univariate analysis, age, tumor size, histologic grade, lymph node involvement, and ER, PR, HER2 status showed prognostic significance for OS; age, tumor size, histologic grade, and lymph node involvement were also negatively associated with DFS. Increased pathological stage was associated with decline in OS and DFS, but this did not reach significance (p = 0.055 and 0.054, respectively) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate analyses of factors associated with survival and recurrence

| Variable | OS | DFS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95 % CI | p | HR | 95 % CI | p | |

| Age, years (>55 vs ≤55) | 2.49 | 1.18–5.26 | 0.017 | 3.37 | 1.51–7.50 | 0.003 |

| Tumor size, cm (>2 vs ≤2) | 4.97 | 2.05–12.10 | <0.001 | 3.42 | 1.56–7.76 | 0.002 |

| Histological grade (III vs I–II) | 3.69 | 1.84–7.38 | <0.001 | 2.81 | 1.40–5.66 | 0.004 |

| TNM stage (III vs I–II) | 2.19 | 0.98–4.88 | 0.055 | 2.20 | 0.99–4.89 | 0.054 |

| LN involvement (yes vs no) | 5.95 | 2.81–12.58 | <0.001 | 6.15 | 2.90–13.04 | <0.001 |

| ER status (pos vs neg) | 0.42 | 0.20–0.85 | 0.016 | 0.58 | 0.28–1.23 | 0.159 |

| PR status (pos vs neg) | 0.49 | 0.25–0.99 | 0.046 | 0.63 | 0.31–1.27 | 0.193 |

| HER2/neu status (pos vs neg) | 2.71 | 1.11–6.61 | 0.028 | 1.69 | 0.59–4.84 | 0.326 |

| CD8+ CTL (high vs low) | 0.97 | 0.48–1.94 | 0.925 | 0.71 | 0.35–1.42 | 0.329 |

| FOXP3+ Treg (high vs low) | 1.74 | 0.85–3.56 | 0.130 | 1.76 | 0.86–3.61 | 0.121 |

| PD-1+ cells (high vs low) | 3.29 | 1.48–7.32 | 0.002 | 2.29 | 1.08–4.84 | 0.024 |

Cox proportional hazards regression model

Bold values are statistically significant (p <0.05)

OS overall surviva, DFS disease free survival, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interva, neg negative, pos positive

Prognostic significance of PD-1 immune cells, CTLs, and Tregs infiltration

Patients with fewer tumor-associated PD-1+ immune cells had longer OS (median 70 months) and DFS (median 69 months) than those with abundant PD-1+ immune cells (median 51 and 34 months, respectively). High tumor infiltrating PD-1+ cell counts were associated with significantly shorter OS (p = 0.002, log rank = 9.55, Fig. 2a), with a hazard ratio (HR) of 3.29 (95 % CI 1.48–7.32) (Table 3). Furthermore, there was significant difference in DFS between patients with high and low PD-1+ cell numbers (p = 0.024, log rank = 5.13, Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of overall survival and disease-free survival for tumor-infiltrating PD-1+ immune cells (a, b), tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) (c, d) and balance between tumor-infiltrating CD8+ cytotoxic cells (CTLs) and PD-1+ immune cells (e, f). High PD-1+ immune cells infiltration associated with both shortened survival and increased recurrence

Extent of lymphocytic infiltration correlated with OS but not for DFS (Supplemental Fig. 1A and 1B). Neither CD8+ TILs nor FOXP3+ Tregs were significantly associated with patient survival (Supplemental Fig. 1C and 1D, Fig. 2C and 2D, respectively).

Combined influence of ratio between CTLs and Tregs or PD-1+ immune cells

On the basis of low and high expression groups for each IHC characteristic, patients were further classified into 4 groups to reflect CD8+/FOXP3+ and CD8+/PD-1+ ratios. CD8+/FOXP3+ ratio was not significantly associated with patient outcome in the univariate Cox model (Supplemental Fig. 1E and 1F).

Interestingly, patients with a high CD8+/PD-1+ ratio had relatively longer OS, and this was statistically significant in univariate analysis (HR 0.46; 95 % CI 0.25–0.84; p = 0.012). Furthermore, patients with CD8+ low/PD-1+ high infiltration showed a significantly poorer outcome compared with other groups in both OS and DFS (Fig. 2e, F).

PD-1 expression not an independent prognostic factor for overall survival

Well-recognized clinical variables, including tumor size, histological grade, and lymph node involvement, were selected as covariates for Cox proportional hazards analyses. Multivariate analysis showed that higher PD-1+ cell counts were not independently associated with shorter OS (HR = 2.06; 95 % CI 0.89–4.77; p = 0.091, Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate analyses of factors associated with overall survival

| Variable | HR | 95 % CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor size, cm | |||

| ≤2 | 1 | ||

| >2 | 3.92 | 1.61–9.58 | 0.003 |

| Histological grade | |||

| I–II | 1 | ||

| III | 2.73 | 1.33–5.64 | 0.007 |

| LN involvement | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 4.48 | 2.10–9.57 | <0.001 |

| PD-1+ cell numbers | |||

| Low | 1 | ||

| High | 2.06 | 0.89–4.77 | 0.091 |

Bold values are statistically significant (p <0.05)

HR hazard ratio, C confidence interval

Discussion

The immune system is envisaged to have a homeostatic role in preventing cancer development through immune surveillance. However, immunologic clearance of macroscopic tumors is rare, although it has been well established that all cancer cells express specific antigens which are derived from genetic alterations and epigenetic dysregulation and are potentially recognizable by T immune cells. The recently refined concept of “cancer immunoediting” integrates the immune system’s dual host-protective and tumor-promoting roles [7]. Tumors may escape the host immune attack by a variety of complementary mechanisms of immunosuppression. The ability to evade destruction by the host immune system, also called immune escape from the immunosurveillance, is now viewed as one of the emerging “hallmarks” of cancer [24]. This is felt to occur through cancer cells “hijacking” multiple mechanisms of immunosuppression, which have evolved to control the stimulation of “immunity to self” [25]. The functional profile of so-called “effector” T cells, which may lead to the death of target cells, is dramatically impacted in cancer by both cellular and molecular mediators [5, 21].

Various immunosuppressive cells are recruited to the tumor microenvironment by suppressive cytokines secreted by cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), among other cells. Of these immunosuppressive cells, Treg cells are crucial mediators in cancer. They inhibit activation and function of effector T cells through immediate cell–cell contact and paracrine production of cytokines such as TGF- and IL-10 [26].

In addition, tumor cells may upregulate surface ligands, including B7 homolog 1 (B7-H1, PD-L1) [27, 28] and other ligands [29–31], which mediate resistance to CTL-induced tumor cell apoptosis by methylation of suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1) [32, 33]. Inducing PD-1 expression on infiltrated immune cells, mainly CD8+ TILs, leading to their “exhausted” state, may explain one way in which tumor cells adapt to escape from immune surveillance [31, 34, 35]. It has recently been suggested that PD-1 may also contribute to anergy of TILs merely by its expression, independent of interaction with its ligands [36]. Hence, heavy infiltration of both FOXP3+ Tregs and PD-1+ anergic immune cells reflects the induced dysfunctional status of the adaptive immune system in the tumor microenvironment. The intratumoral balance between functional effector T cells and regulatory T cells reflects the host’s anticancer ability and thus may be an independent prognostic indicator [37].

In this study, tumor cell-associated immune cells (CD8+ CTLs, FOXP3+ Tregs, and PD-1+ cells) including their density and types were retrospectively investigated, with the aim of determining a correlation with patient outcome. These analyses were performed by IHC staining using sequential tumor sections.

PD-1+ cell infiltration was observed in most of the breast tumors. Similar to previous studies investigating TILs, the median value was chosen as the cutoff in order to compare the role of high numbers of PD-1+ immune cells. In data from RCC patients [20], where 29.2 % (78/267) of patients demonstrated moderate to marked infiltration of mononuclear immune cells, 28.8 % (77/267) of tumors presented PD-1+ cells [20]. In a recent similar study in breast cancer [38], the ratio (15.8 %, 104/660) was much less than the percent of patients with PD-1+ cells (91.3 %, 190/208) in our study. Of note, we used whole sections, which could provide more information than tissue microarray, and high-powered microscopic fields representing the densest lymphocytic infiltrates were selected and counted. Thus, we obtained far more positive PD-1+ cells than Muenst et al. [38].

In accordance with a previous breast cancer report [19], both PD-1+ cells and FOXP3+ Tregs were significantly associated with poor tumor differentiation, more advanced stage and other unfavorable prognostic factors. Significantly, more PD-1+ immune cell infiltration was observed in tumors with unfavorable molecular features, including negative ER/PR expression and triple negativity. Furthermore, patients with HER-2 positive tumors and lymph node involvement were prone (p = 0.098 and 0.010, respectively) to have more infiltrating PD-1+ cells (Table 2).

No correlation between CD8+ cells and clinicopathologic factors except for patient age was found (Supplemental Table 3). Furthermore, CTLs (CD8+ cells), which are primarily responsible for cancer control through the adaptive immune system and reported to be prognostic in various cancer types [3, 4, 37, 39], did not correlate with improved OS or DFS. Notably, in our study, we attempted to distinguish between stromal lymphocytes and TILs. Only those lymphocytes in direct contact with tumor cells were considered to represent an in situ host antitumor immune response and thus counted. This criterion was based on recent studies in this field [3, 4, 40]. The present results are consistent with the findings that CD8+ TILs in remote stroma, rather than tumor cell-associated CD8+ T cells, seem to predict breast cancer survival [3, 4].

FOXP3+ Tregs infiltration also did not demonstrate an association with the patient survival, consistent with previously published breast cancer data [40], suggesting that it is not possible to predict clinical outcome using Tregs alone. In that study, intratumoural and tumor-adjacent stromal FOXP3+ cells were associated with a worse prognosis with long-term follow-up. However, in multivariate analysis, number of FOXP3+ cells was not found to be an independent prognostic factor. It was thus concluded that FOXP3+ infiltrating cells did not have a dominant role in prognosis [40].

By univariate analysis, we observed a positive association between high tumor infiltrating PD-1 counts and shorter OS (p = 0.002, log rank = 9.55, Fig. 2a). HR was 3.29 (95 % CI 1.48–7.32), compared to the HR, 2.24, of PD-1 expression in RCC patients [20]. Thus, it could be that induction of PD-1 expression on infiltrating immune cells allows tumor cells to escape immune surveillance [28].

While absolute numbers of TILs reflect general activation of the host immune system, the ratio between effector and regulatory T cells (Tregs) may serve as a better independent prognostic factor for breast cancer survival [4, 9]. In one breast cancer study, the peritumoral CTL/Treg ratio was shown to be an independent prognostic factor [4]. However, the CD8+/FOXP3+ effect on OS and PFS was not found in our study to be significant, possibly because of the small patient number. However, the high CD8+/PD-1+ ratio seemingly improved survival (Fig. 2e, f), suggesting its fundamental role in reflecting the functional immune host status, thereby predicting outcome.

In contrast to the study by Muenst et al. [38], high PD-1 expression was not an independent prognostic factor in multivariate analysis when adjusted for well-recognized clinical variables. This may be a result of low statistical power of this study due to the relatively small patient number. However, multiple layers of immune suppression mechanisms in tumor evasion [41] and the complexity of the tumor microenvironment [26] could also explain this. Other suppressive immune cells besides Tregs such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) [42] might also promote indirect immune escape [21]. Clearly, there are other co-stimulatory checkpoints expressed on immune cells besides PD-1, including 2B4 (CD244), BTLA, CTLA-4, CD160, LAG-3, and Tim-3, each of which may play a part in the immune response [8, 10, 43].

The predictive values of Tregs and CTLs in breast cancer remain fairly controversial. FOXP3+ infiltrating cells have been found inconsistently to be an independent prognostic factor in patients with ER-positive-only tumors [44], both ER-positive and ER-negative groups [45], or neither of them [40]. Surprisingly, one study found that high numbers of FOXP3 TIL were associated with a favorable prognosis in ER-negative patients [46]. Similarly, CD8+ cells were a favorable independent prognostic value only in ER-negative [47] or in basal-like breast cancers, but not in other intrinsic molecular subtypes [48]. Thus, it seems likely that different immune mechanisms are operational in different types of breast cancer [6]. Due to the relatively small number of patients, 111 in all, we made no attempt to determine the predictive value of the lymphocytic variables in various molecular subtypes. Further studies are warranted to verify these findings and further explore the underlying mechanisms.

Passive transfer of the monoclonal antibody, trastuzumab, has been well-established HER2+ breast cancer treatment [49]. Although not always considered as ‘immunotherapy’, its success reflects the ability of inducing an immediate immune reaction against the non-immunogenic cancer [5]. At this time, strategies for inducing antitumor immune responses by the patients’ own immune system to undermine the cancer-induced immunosuppressive mechanisms are actively under investigation.

Molecular and cellular mediators of cancer-induced immunosuppression, such as CTLA-4, PD-1, and Treg cells, have been studied in breast cancer [32, 35, 50], as well as the best-known escape mechanisms such as loss of tumor antigen expression [5, 7]. One of the generally accepted reasons for which the immune system has a low anticancer efficacy is that TILs are dysfunctional through expression of inhibitory receptors, like PD-1 [12, 50, 51]. Dissecting the functional role of different subsets of TILs in the tumor suppressive microenvironment is thus important.

Treatment for cancer patients by restoration of effective antitumor immune responses may require approaches aimed at protecting antitumor immune cells from the effects of regulatory cells and/or prolonging survival and function of effector cells by inhibiting negative stimulation and metabolic constraints [25]. Interestingly, the PD-L1/PD-1 axis has been reported to be involved in the development of induced Treg cells [33]. Therefore, targeting this signaling pathway may also reduce Treg development and function [52].

Cancer immunotherapy seems finally to have come of age after decades of failure and disappointment [5, 8]. Following the success of ipilimumab (anti-CTLA4) in metastatic melanoma, several groups have conducted trials aiming at subverting other immune checkpoints [11]. Blocking the PD-1 pathway has achieved objective responses and durable remissions of several late stage solid malignancies, including the poorly immunogenic NSCLC, with an 18 % overall response rate [14]. These preliminary results may shed light on a curative treatment for breast cancer, as well, although only 4 patients were recruited in the anti-PD-L1 trial, with no responses observed [15]. Still, this approach needs to be further explored in breast cancer [11, 15, 53]. As suggested, such immunotherapeutic strategies may be more rationally applied as adjuvant therapy in the early stage, low-volume settings [21].

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results provide some evidence of the prognostic importance of the PD-1+ immune cell population in breast cancer. Tumor progression was associated with increased Tregs and the immune check point PD-1 expression on CTLs and other immune cells at the tumor site [51]. Expression of PD-1 is associated with anergy and an inactive or apoptotic status of activated tumor infiltrating effector cells [54], thus weakening the host immune response and promoting tumor cell growth, ultimately affecting the outcome. Targeting T cell dysfunctional mechanisms thus seems to be a promising approach to treating breast cancer patients.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Research supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81202087; 81172520; 81202088), Leading Academic Discipline Project of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (Grant No. J50208), and Foundation of Shanghai Science and Technology Commission (Grant No. 12140901503).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- PD-1

Programmed death-1

- Treg

Regulatory T cell

- CTL

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- OS

Overall survival

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- BCSS

Breast cancer-specific survival

- TIL

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte

- PD-L1

Programmed death-ligand 1

- IHC

Immunohistochemical

- FFPE

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- H&E

Hematoxylin and eosin

- HPF

High-powered field

- SD

Standard deviation

- IDC

Invasive ductal carcinoma

- ILC

Invasive lobular carcinoma

- SE

Standard error

- ER

Estrogen receptor

- PR

Progesterone receptor

- HER2

Human epidermal growth factor receptor-2

- TNBC

Triple-negative breast cancer

- CAF

Cancer-associated fibroblast

- SOCS1

Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1

- RCC

Renal cell carcinoma

- HR

Hazard ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- MDSC

Myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- TAM

Tumor-associated macrophage

- ORR

Overall response rate

Footnotes

Shenyou Sun and Xiaochun Fei have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Caras I, Grigorescu A, Stavaru C, Radu D, Mogos I, Szegli G, Salageanu A. Evidence for immune defects in breast and lung cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:1146–1152. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0556-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andre F, Dieci MV, Dubsky P, Sotiriou C, Curigliano G, Denkert C, Loi S. Molecular pathways: involvement of immune pathways in the therapeutic response and outcome in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:28–33. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahmoud SM, Paish EC, Powe DG, Macmillan RD, Grainge MJ, Lee AH, Ellis IO, Green AR. Tumor-infiltrating CD8+ lymphocytes predict clinical outcome in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1949–1955. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.5037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu F, Lang R, Zhao J, Zhang X, Pringle GA, Fan Y, Yin D, Gu F, Yao Z, Fu L. CD8(+) cytotoxic T cell and FOXP3(+) regulatory T cell infiltration in relation to breast cancer survival and molecular subtypes. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130:645–655. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1647-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mellman I, Coukos G, Dranoff G. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature. 2011;480:480–489. doi: 10.1038/nature10673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahmoud S, Lee A, Ellis I, Green A. CD8+ T lymphocytes infiltrating breast cancer: a promising new prognostic marker? Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:364–365. doi: 10.4161/onci.18614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 2011;331:1565–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.1203486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Topalian SL, Weiner GJ, Pardoll DM. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4828–4836. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.deLeeuw RJ, Kost SE, Kakal JA, Nelson BH. The prognostic value of FoxP3+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in cancer: a critical review of the literature. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:3022–3029. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:252–264. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Targeting PD-1/PD-L1 interactions for cancer immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:1223–1225. doi: 10.4161/onci.21335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, Tamura H, Hirano F, Flies DB, Roche PC, Lu J, Zhu G, Tamada K, Lennon VA, Celis E, Chen L. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med. 2002;8:793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm0902-1039c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monaghan SF, Thakkar RK, Tran ML, Huang X, Cioffi WG, Ayala A, Heffernan DS. Programmed death 1 expression as a marker for immune and physiological dysfunction in the critically ill surgical patient. Shock. 2012;38:117–122. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31825de6a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Atkins MB, Leming PD, Spigel DR, Antonia SJ, Horn L, Drake CG, Pardoll DM, Chen L, Sharfman WH, Anders RA, Taube JM, McMiller TL, Xu H, Korman AJ, Jure-Kunkel M, Agrawal S, McDonald D, Kollia GD, Gupta A, Wigginton JM, Sznol M. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, Drake CG, Camacho LH, Kauh J, Odunsi K, Pitot HC, Hamid O, Bhatia S, Martins R, Eaton K, Chen S, Salay TM, Alaparthy S, Grosso JF, Korman AJ, Parker SM, Agrawal S, Goldberg SM, Pardoll DM, Gupta A, Wigginton JM. Safety and activity of anti–PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flemming A. Cancer: PD1 makes waves in anticancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:601. doi: 10.1038/nrd3806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janakiram M, Abadi YM, Sparano JA, Zang X. T cell coinhibition and immunotherapy in human breast cancer. Discov Med. 2012;14(77):229–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ribas A. Tumor immunotherapy directed at PD-1. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2517–2519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1205943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghebeh H, Barhoush E, Tulbah A, Elkum N, Al-Tweigeri T, Dermime S. FOXP3+ Tregs and B7-H1+/PD-1+ T lymphocytes co-infiltrate the tumor tissues of high-risk breast cancer patients: implication for immunotherapy. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson RH, Dong H, Lohse CM, Leibovich BC, Blute ML, Cheville JC, Kwon ED. PD-1 is expressed by tumor-infiltrating immune cells and is associated with poor outcome for patients with renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1757–1761. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hensel JA, Flaig TW, Theodorescu D. Clinical opportunities and challenges in targeting tumour dormancy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;10:41–51. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elston C, Ellis I. Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. I. The value of histological grade in breast cancer: experience from a large study with long-term follow-up. Histopathology. 2002;41(3A):154–161. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.14691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Black M, Speer F, Opler S. Structural representations of tumor-host relationships in mammary carcinoma; biologic and prognostic significance. Am J Clin Pathol. 1956;26:250. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/26.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stewart TJ, Smyth MJ. Improving cancer immunotherapy by targeting tumor-induced immune suppression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2011;30:125–140. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fridman WH, Pages F, Sautes-Fridman C, Galon J. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nrc3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghebeh H, Mohammed S, Al-Omair A, Qattan A, Lehe C, Al-Qudaihi G, Elkum N, Alshabanah M, Bin Amer S, Tulbah A, Ajarim D, Al-Tweigeri T, Dermime S. The B7-H1 (PD-L1) T lymphocyte-inhibitory molecule is expressed in breast cancer patients with infiltrating ductal carcinoma: correlation with important high-risk prognostic factors. Neoplasia. 2006;8:190–198. doi: 10.1593/neo.05733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taube JM, Anders RA, Young GD, Xu H, Sharma R, McMiller TL, Chen S, Klein AP, Pardoll DM, Topalian SL, Chen L. Colocalization of inflammatory response with B7-h1 expression in human melanocytic lesions supports an adaptive resistance mechanism of immune escape. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:127–137. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rozali EN, Hato SV, Robinson BW, Lake RA, Lesterhuis WJ. Programmed death ligand 2 in cancer-induced immune suppression. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:656340. doi: 10.1155/2012/656340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hasan A, Ghebeh H, Lehe C, Ahmad R, Dermime S. Therapeutic targeting of B7-H1 in breast cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2011;15:1211–1225. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.613826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poschke I, De Boniface J, Mao Y, Kiessling R. Tumor-induced changes in the phenotype of blood-derived and tumor-associated T cells of early stage breast cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(7):1611–1620. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen DS, Irving BA, Hodi FS. Molecular pathways: next-generation immunotherapy—inhibiting programmed death-ligand 1 and programmed death-1. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:6580–6587. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Francisco LM, Salinas VH, Brown KE, Vanguri VK, Freeman GJ, Kuchroo VK, Sharpe AH. PD-L1 regulates the development, maintenance, and function of induced regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:3015–3029. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM. Targeting the PD-1/B7-H1(PD-L1) pathway to activate anti-tumor immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi F, Shi M, Zeng Z, Qi RZ, Liu ZW, Zhang JY, Yang YP, Tien P, Wang FS. PD-1 and PD-L1 upregulation promotes CD8(+) T-cell apoptosis and postoperative recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:887–896. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang SF, Fouquet S, Chapon M, Salmon H, Regnier F, Labroquère K, Badoual C, Damotte D, Validire P, Maubec E, Delongchamps NB, Cazes A, Gibault L, Garcette M, Dieu-Nosjean MC, Zerbib M, Avril MF, Prévost-Blondel A, Randriamampita C, Trautmann A, Bercovici N. Early T cell signalling is reversibly altered in PD-1+ T lymphocytes infiltrating human tumors. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao Q, Qiu SJ, Fan J, Zhou J, Wang XY, Xiao YS, Xu Y, Li YW, Tang ZY. Intratumoral balance of regulatory and cytotoxic T cells is associated with prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma after resection. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2586–2593. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.4565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muenst S, Soysal S, Gao F, Obermann E, Oertli D, Gillanders W. The presence of programmed death 1 (PD-1)-positive tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes is associated with poor prognosis in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;139:667–676. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2581-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamanishi J, Mandai M, Iwasaki M, Okazaki T, Tanaka Y, Yamaguchi K, Higuchi T, Yagi H, Takakura K, Minato N, Honjo T, Fujii S. Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 and tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes are prognostic factors of human ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3360–3365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611533104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahmoud SM, Paish EC, Powe DG, Macmillan RD, Lee AH, Ellis IO, Green AR. An evaluation of the clinical significance of FOXP3+ infiltrating cells in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127:99–108. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0987-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Topfer K, Kempe S, Muller N, Schmitz M, Bachmann M, Cartellieri M, Schackert G, Temme A. Tumor evasion from T cell surveillance. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:918471. doi: 10.1155/2011/918471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heys SD, Stewart KN, McKenzie EJ, Miller ID, Wong SY, Sellar G, Rees AJ. Characterisation of tumour-infiltrating macrophages: impact on response and survival in patients receiving primary chemotherapy for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;135:539–548. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pardoll D, Drake C. Immunotherapy earns its spot in the ranks of cancer therapy. J Exp Med. 2012;209:201–209. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bates GJ, Fox SB, Han C, Leek RD, Garcia JF, Harris AL, Banham AH. Quantification of regulatory T cells enables the identification of high-risk breast cancer patients and those at risk of late relapse. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5373–5380. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.9584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu H, Zhang T, Ye J, Li H, Huang J, Li X, Wu B, Huang X, Hou J. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes predict response to chemotherapy in patients with advance non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61:1849–1856. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1231-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.West NR, Kost SE, Martin SD, Milne K, Deleeuw RJ, Nelson BH, Watson PH. Tumour-infiltrating FOXP3(+) lymphocytes are associated with cytotoxic immune responses and good clinical outcome in oestrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:155–162. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baker K, Lachapelle J, Zlobec I, Bismar TA, Terracciano L, Foulkes WD. Prognostic significance of CD8+ T lymphocytes in breast cancer depends upon both oestrogen receptor status and histological grade. Histopathology. 2011;58:1107–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu S, Lachapelle J, Leung S, Gao D, Foulkes WD, Nielsen TO. CD8+ lymphocyte infiltration is an independent favorable prognostic indicator in basal-like breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R48. doi: 10.1186/bcr3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohd Sharial MS, Crown J, Hennessy BT. Overcoming resistance and restoring sensitivity to HER2-targeted therapies in breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:3007–3016. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ahmadzadeh M, Johnson LA, Heemskerk B, Wunderlich JR, Dudley ME, White DE, Rosenberg SA. Tumor antigen—specific CD8 T cells infiltrating the tumor express high levels of PD-1 and are functionally impaired. Blood. 2009;114:1537–1544. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou Q, Munger ME, Highfill SL, Tolar J, Weigel BJ, Riddle M, Sharpe AH, Vallera DA, Azuma M, Levine BL, June CH, Murphy WJ, Munn DH, Blazar BR. Program death-1 signaling and regulatory T cells collaborate to resist the function of adoptively transferred cytotoxic T lymphocytes in advanced acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2010;116:2484–2493. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-275446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peng DJ, Liu R, Zou W. Regulatory T cells in human ovarian cancer. J Oncol. 2012;2012:345164. doi: 10.1155/2012/345164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Flemming A. Cancer: PD1 makes waves in anticancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:601–605. doi: 10.1038/nrd3806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:677–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.