Abstract

Several chemotherapeutic drugs have immune-modulating effects. For example, cyclophosphamide (CP) and gemcitabine (GEM) diminish immunosuppression by regulatory T cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), respectively. Here, we show that intermittent (metronomic) chemotherapy with low-dose CP plus GEM can induce anti-tumor T cell immunity in CT26 colon carcinoma-bearing mice. Although no significant growth suppression was observed by injections of CP (100 mg/kg) at 8-day intervals or those of CP (50 mg/kg) at 4-day intervals, CP injection (100 mg/kg) increased the frequency of tumor peptide-specific T lymphocytes in draining lymph nodes, which was abolished by two injections of CP (50 mg/kg) at a 4-day interval. Alternatively, injection of GEM (50 mg/kg) was superior to that of GEM (100 mg/kg) in suppressing tumor growth in vivo, despite the smaller dose. When CT26-bearing mice were treated with low-dose (50 mg/kg) CP plus (50 mg/kg) GEM at 8-day intervals, tumor growth was suppressed without impairing T cell function; the effect was mainly T cell dependent. The metronomic combination chemotherapy cured one-third of CT26-bearing mice that acquired tumor-specific T cell immunity. The combination therapy decreased Foxp3 and arginase-1 mRNA levels but increased IFN-γ mRNA expression in tumor tissues. The percentages of tumor-infiltrating CD45+ cells, especially Gr-1high CD11b+ MDSCs, were decreased. These results indicate that metronomic chemotherapy with low-dose CP plus GEM is a promising protocol to mitigate totally Treg- and MDSC-mediated immunosuppression and elicit anti-tumor T cell immunity in vivo.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-012-1343-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cyclophosphamide, Gemcitabine, T cell immunity, MDSC, Treg

Introduction

Recent advances in tumor immunology have identified immunosuppressive cells that inhibit anti-tumor immune responses in tumor-bearing hosts; these include CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) [1, 2]. Tregs can act as suppressive cells in anti-cancer immunotherapy, and their presence at local tumor sites correlates with an unfavorable prognosis [3, 4]. MDSC numbers also increase in cancer-bearing hosts, and can inhibit T cell responses in cancer patients [5, 6]. For successful anti-cancer immunotherapy, immunosuppression mediated by these cells must be overcome, and several methods have been proposed. Treg-mediated immunosuppression can be relieved by antibodies [7–9] and several reagents are available which can reduce MDSC function [10–12].

Given the tenet in chemotherapy that the maximum tolerated dose should be administered, conventional chemotherapy is inevitably associated with a risk of deterioration in immunological competence. However, new aspects to anti-cancer chemotherapy have been proposed recently. Some anti-cancer drugs, such as anthracyclines, can stimulate and promote dendritic cells (DCs) to take up dying tumor cells and process tumor antigens [13–15]. This immunogenic tumor cell death is crucial for treatment-associated prognosis and for the survival of tumor-bearing hosts [16]. Alternatively, some chemotherapeutic drugs, including cyclophosphamide (CP) and gemcitabine (GEM), can modulate immune responses; CP can mitigate Treg-mediated immunosuppression when administered at low doses [17–21], while low-dose GEM selectively decreases MDSCs in cancer-bearing hosts [22]. Additionally, a unique protocol called metronomic chemotherapy [23], which involves intermittent administration of low-dose chemotherapeutic drugs, has been proposed. Mechanistically, metronomic chemotherapy using low-dose CP is thought to reduce tumor angiogenesis by up-regulating the endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor, thrombospondin-1, in tumor and perivascular cells [24]. Moreover, metronomic chemotherapy with low-dose CP can relieve Treg-mediated immunosuppression in rodents and cancer patients [25, 26]. In addition, metronomic chemotherapy with low-dose GEM can cause anti-tumor effects [27].

In this study, we determined whether metronomic chemotherapy with low-dose CP plus GEM could mitigate Treg- and MDSC-mediated immunosuppression concurrently using CT26 colon carcinoma-bearing mice as a model. Our findings indicate that this chemotherapy does not impair T cell function, but rather efficiently elicits anti-tumor T cell immunity in vivo. These results indicate that metronomic chemotherapy with low-dose CP plus GEM is a promising protocol to mitigate totally Treg- and MDSC-mediated immunosuppression and elicit anti-tumor T cell immunity in tumor-bearing hosts.

Materials and methods

Mice and tumor cell lines

BALB/c and BALB/c nu/nu female mice (H-2d: 6–7 weeks old) were purchased from CLEA Japan, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) and Japan SLC, Inc. (Hamamatsu, Japan), respectively. Mice were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions. Experiments were performed according to the ethical guidelines for animal experiments of the Shimane University Faculty of Medicine. CT26 and RENCA are colon and renal cell carcinoma cell lines of BALB/c mouse origin, respectively. They were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum.

Therapy protocol

BALB/c mice were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) into the right flank with 5 × 105 CT26 cells. On the indicated days, the mice received an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of CP (Shionogi Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and/or GEM (Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX, USA) at the indicated doses. In some experiments, CP and/or GEM were administered i.p. with either a 4- or 8-day interval between administrations. Following tumor inoculation, tumor size (mm2) was measured twice weekly.

In vitro culture of tumor-draining lymph node (LN) cells and ELISA

To test for specific T cell responses against a tumor antigen, an H-2Ld-binding peptide (SPSYVYHQF) derived from the envelope protein (gp70) of an endogenous murine leukemia virus was used. This specific peptide is referred to as a CT26-associated tumor-derived peptide [28], and is designated AH1. Measles virus hemagglutinin (SPGRSFSYF) was used as an H-2Ld-binding control peptide. All peptides showed >80 % purity and were purchased from Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA. For ELISA, tumor-draining LNs were harvested, pooled, and stimulated in vitro with the indicated peptides for 3 days, with 5 × 105 cells/well in 96-well flat plates. An ELISA MAX™ Set Deluxe (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to determine IFN-γ levels in the culture supernatants.

Flow cytometry

The spleen cells of BALB/c mice that had been injected i.p. with 50 mg/kg CP and/or GEM were harvested and their subsets were determined by flow cytometry using the following monoclonal antibodies (mAbs): PE-conjugated anti-CD4 mAb (AbD Serotec, Oxford, UK), FITC-conjugated anti-CD8 mAb (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA), FITC-conjugated anti-B220 mAb (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), and PE-conjugated anti-CD11b mAb (BioLegend). In some experiments, tumor-infiltrating immune cells were analyzed. Ten days after tumor inoculation, CP and/or GEM were injected i.p. Two days after the CP and/or GEM injection, tumor tissues were harvested. The tumors were minced using slide glasses, passed through gauze mesh, and stained with the following mAbs: APC-conjugated anti-CD45 mAb (BioLegend), FITC-conjugated anti-Gr-1 mAb (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), and PE-conjugated anti-CD11b mAb. The stained cells were analyzed by FACScaliber flow cytometry (Becton–Dickinson, Fullerton, CA, USA).

In vitro stimulation with anti-CD3 mAb

Spleen cells from BALB/c mice that were injected i.p. with 50 mg/kg CP and GEM were harvested and cultured for 2 days in 96-well plates pre-coated with an anti-CD3 mAb (clone 145-2C11; BioLegend) with 5 × 105 cells/well. Thereafter, the IFN-γ level in the supernatant was determined by ELISA.

In vitro mixed culture with tumor cells

Spleen cells (5 × 105/well) from naïve mice or mice that were cured CT26 by the metronomic combination therapy were cultured with inactivated CT26 or RENCA cells (5 × 104/well) for 3 days. CT26 and RENCA cells were inactivated by culturing in the presence of 100 μg/ml mitomycin-C (MMC; Kyowa Hakko Co. Ltd., Japan) for 2 h. The IFN-γ level in the supernatant was then determined by ELISA.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen Corp.), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNA was generated using the Superscript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) and random primers, and amplified using Platinum Tag DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) with EXPRESS SYBR GreenER qPCR SuperMixes (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was carried out in duplicate using the ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System. Thermal cycling included an initial denaturation step of 2 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. mRNA levels relative to that of β-actin were calculated. The following primers (sense and anti-sense, respectively) were used for IFN-γ: 5′-TCAAGTGGCATAGATGTGGAAGAA-3′ and 5′-TGGCTCTGCAGGATTTTCATG-3′; for Foxp3: 5′-TGCAGGGCAGCTAGGTACTTGTA-3′ and 5′-TCTCGGAGATCCCCTTTGTCT-3′; for arginase-1: 5′-CAGAAGAATGGAAGAGTCAG-3′ and 5′-CAGATATGCAGGGAGTCACC-3′; and for β-actin: 5′-AGAGGGAAATCGTGCGTGAC-3′ and 5′-CAATAGTGATGACCTGGCCGT-3′.

Protective models

To test for protective immunity against CT26, CT26-cured mice after metronomic combination therapy were injected s.c. with 2 × 105 CT26 cells 60 days after the initial tumor inoculation.

Statistics

Data were evaluated using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test or ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

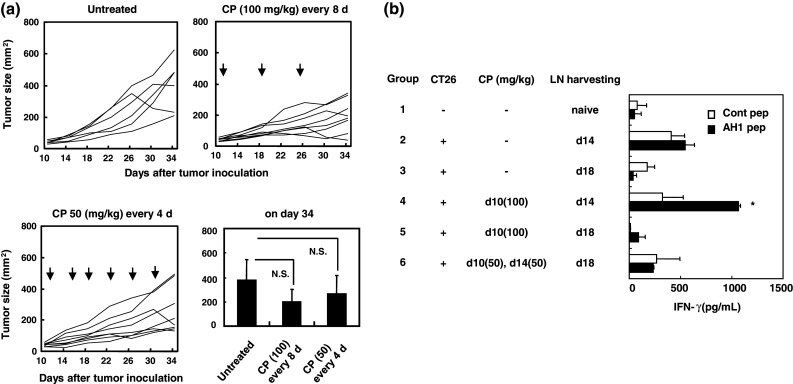

Anti-tumor effects induced by intermittent injections of CP

We first compared the anti-tumor effects induced by i.p. injection of CP administered at either 8-day (100 mg/kg) or 4-day (50 mg/kg) intervals against established CT26 tumor cells (Fig. 1a). Although the tumor size in mice that were treated with CP (100 mg/kg) at 8-day intervals was smaller than those of untreated mice and of mice that were treated with CP (50 mg/kg) at 4-day intervals, no significant difference was observed. We next tested the reactivity of tumor peptide-specific T cells from the draining LNs of mice that had been treated using several protocols. We tested the response to an H-2Ld-binding AH1 peptide derived from the envelope protein (gp70) of an endogenous murine leukemia virus [27]. Tumor-draining LNs from groups of mice were pooled and cultured in vitro with each of the indicated peptides (Fig. 1b). In the draining LN cells from mice that were treated with CP (100 mg/kg) 4 days before (group-4), AH1 peptide-specific IFN-γ production was observed, whereas reactivity was not observed when the draining LNs were harvested 8 days after the injection of CP (100 mg/kg) (group-5). Interestingly, the draining LN cells that were harvested 4 days after the second injection of CP (50 mg/kg) exhibited no reactivity to the AH1 peptide (group-6). Taken together, these results indicate that injections with 8-day intervals are superior in eliciting tumor peptide-specific T cell immunity in vivo over those with 4-day intervals between injections.

Fig. 1.

Anti-tumor effects induced by intermittent injections of low-dose CP. a BALB/c mice were injected s.c. with 5 × 105 CT26 cells into the right flank. On day 10, mice were injected i.p. with either CP (100 mg/kg) with an 8-day interval or CP (50 mg/kg) with a 4-day interval between injections. Arrows indicate the CP injection. Tumor size (mm2) was measured twice weekly. Each group consisted of six or eight mice, and lines represent tumor growth. The mean ± SD of the results on day 34 after tumor inoculation are shown. Similar results were obtained in three experiments. NS, not significant by ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test. b BALB/c mice were injected s.c. with 5 × 105 CT26 cells into the right flank. On the indicated days, mice were injected i.p. with CP (50 or 100 mg/kg) and draining LNs were harvested, pooled, and stimulated in vitro with the AH1 or the control peptide. After 3 days, IFN-γ levels in the supernatant were determined by ELISA. Each group consisted of three mice. *P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance by Student’s t test

Anti-tumor effects induced by the injection of low-dose GEM against established CT26 tumor cells

Next, we examined the anti-tumor effects induced by i.p. injection of GEM at a dose of either 50 or 100 mg/kg (Fig. 2). Injection of GEM (50 mg/kg) suppressed tumor growth significantly when the tumor size was evaluated on day 30 after tumor inoculation. Although the tumor size decreased to almost half of the untreated control following injection of GEM (100 mg/kg), the difference was not significant. These results indicate that despite the smaller dose, GEM at 50 mg/kg is therapeutically superior to GEM at 100 mg/kg in suppressing tumor growth in vivo.

Fig. 2.

Injection of low-dose GEM suppresses tumor growth in vivo. BALB/c mice were injected s.c. with 5 × 105 CT26 cells into the right flank. On day 10, mice were injected i.p. with GEM (50 or 100 mg/kg). Arrows indicate the injection of GEM. Tumor size (mm2) was measured twice weekly. Each group consisted of five or six mice, and lines represent tumor growth in each mouse. The mean ± SD of the results on day 30 after tumor inoculation are also shown. Similar results were obtained in two experiments. *P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance by ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test. NS, not significant

Anti-tumor effects of metronomic chemotherapy with low-dose CP plus GEM

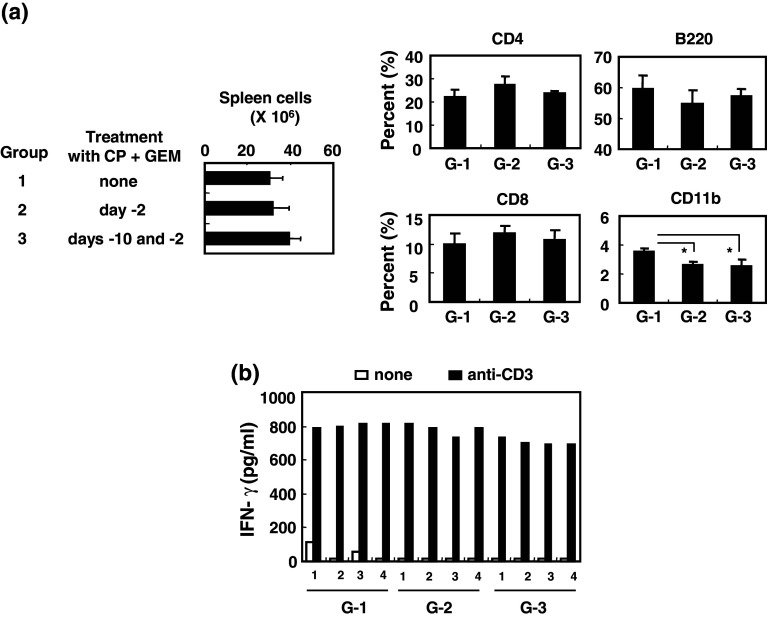

Before testing the anti-tumor effects of low-dose CP plus GEM, we examined how this therapy affects immune cells. The number of spleen cells from mice that had been injected i.p. with low-dose CP and GEM 2 days before (once) or 10 days and 2 days before (twice) spleen harvesting showed a slight increase, but not significant (Fig. 3a). The combination therapy significantly decreased the percentage of CD11b+ monocytes in the spleen but did not alter CD4+ T cell, CD8+ T cell, or B220+ B cell numbers. Additionally, one or two injections of low-dose CP plus GEM did not interfere with the ability of splenic T cells to produce IFN-γ (Fig. 3b), suggesting that the combination of CP plus GEM chemotherapy at a dose of 50 mg/kg did not suppress T cell function.

Fig. 3.

No suppressive effect of the combination chemotherapy with low-dose CP plus GEM on splenic T cell function. a Naïve BALB/c mice were injected i.p. with CP (50 mg/kg) and GEM (50 mg/kg) on the indicated days. Spleen cells were harvested, counted, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Each group consisted of four mice. *P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance by Student’s t test. b Spleen cells from individual mice were cultured in anti-CD3 mAb-coated wells for 2 days, and IFN-γ levels in supernatants were determined by ELISA. Numbers represent individual mice

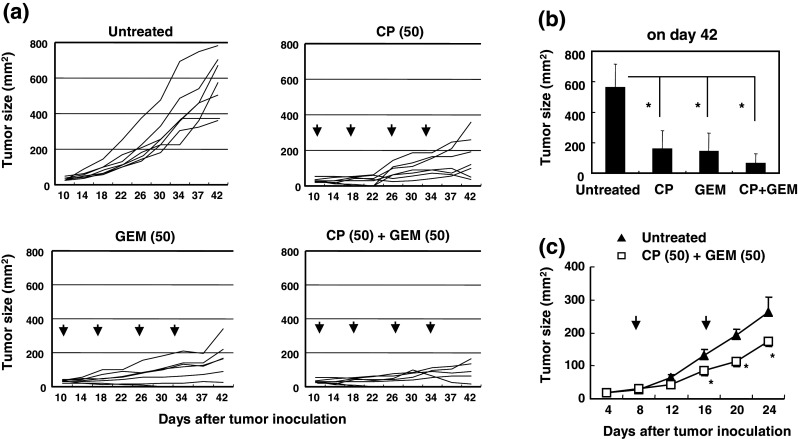

Next, we examined the anti-tumor effects of low-dose (50 mg/kg) CP and/or GEM administered with 8-day intervals between injections. Although either CP or GEM alone suppressed tumor growth significantly, metronomic chemotherapy with CP plus GEM further suppressed tumor size to close to half that resulting from a single therapy (Fig. 4a, b). As shown in Fig. 4c, two injections of CP and GEM at an 8-day interval delayed tumor growth significantly in nude mice. However, the ‘plateau’ of growth suppression seen with wild-type BALB/c mice was not observed in nude mice, suggesting that T cells mediate the continuous growth suppression of CT26 in BALB/c mice seen after the metronomic combination chemotherapy.

Fig. 4.

Injections of low-dose CP and GEM with an 8-day interval suppress tumor growth. a BALB/c mice were injected s.c. with 5 × 105 CT26 cells into the right flank. Ten days later, these mice were injected i.p. with CP (50 mg/kg) and/or GEM (50 mg/kg) with an 8-day interval between injections. Arrows represent the injections. Tumor size (mm2) was measured twice weekly. Each group consisted of six or seven mice, and lines represent tumor growth. b The mean ± SD of the results on day 42 after tumor inoculation are shown. *P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance by ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test. Similar results were obtained in three experiments. c BALB/c nude mice were injected s.c. with 5 × 105 CT26 cells into the right flank. On days 8 and 16, these mice were injected i.p. with CP (50 mg/kg) and GEM (50 mg/kg). Arrows indicate the injections of CP and GEM. Each group consisted of five mice. *P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance by Student’s t test

We next tested the response of tumor peptide-specific T cells in CT26-carrying mice that had received different treatment protocols (supplementary Fig. 1). LN cells from mice treated with CP alone or CP plus GEM 4 days before LN harvesting produced AH1 peptide-specific IFN-γ (group-5 and -6). However, the draining LN cells from mice treated with GEM alone 4 days before LN harvesting failed to show AH1 peptide-specific reactivity (group-2). These results suggest that CP is more potent than GEM in inducing tumor peptide-specific and class I-restricted T cells in draining LNs in vivo.

Tumor-specific T cell immunity in CT26-cured mice after metronomic low-dose CP plus GEM chemotherapy

We next determined whether protective immunity was induced in CT26-cured mice after metronomic chemotherapy. As shown in Fig. 5a, when 24 CT26-bearing mice were treated with metronomic chemotherapy with low-dose CP plus GEM three times, CT26 tumors were cured in eight. Furthermore, when six of these mice were challenged with CT26 60 days after the initial tumor inoculation, all mice rejected the tumor. Spleen cells from two mice that cured the CT26 tumor were cultured with inactivated CT26 or RENCA cells, as controls, and their IFN-γ production was examined (Fig. 5b). IFN-γ production by the spleen cells from CT26-cured mice decreased upon addition of RENCA cells, but was restored significantly by addition of CT26 cells. In contrast, IFN-γ production by spleen cells from naïve mice decreased due to the addition of either CT26 or RENCA cells at similar levels. Given the non-specific suppressive effects of the inactivated tumor cells, these results suggest that CT26-cured mice have CT26-specific T cells capable of conferring protective immunity following metronomic chemotherapy.

Fig. 5.

Tumor-specific T cell immunity in CT26-cured mice after metronomic combination chemotherapy. a BALB/c mice were injected s.c. with 5 × 105 CT26 cells into the right flank. On days 10, 18, and 26, these mice (n = 24) were injected i.p. with CP (50 mg/kg) and GEM (50 mg/kg). Arrows indicate the injections. Tumor size (mm2) was measured twice weekly. Lines represent tumor growth. Six mice that cured of CT26 were inoculated s.c. with 2 × 105 CT26 cells 60 days after the initial tumor inoculation. Inset shows the tumor growth in naïve BALB/c mice that were inoculated s.c. with 2 × 105 CT26 cells. b Spleen cells from naïve or CT26-cured mice were cultured with MMC-treated CT26 or RENCA cells for 3 days, and IFN-γ levels in supernatants were determined by ELISA. Numbers represent individual mice. *P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance by Student’s t test

Mitigation of immunosuppression in tumor sites after the combination therapy

We finally determined the effects of therapy with low-dose CP and/or GEM on the tumor microenvironment (Fig. 6a). Tregs and MDSCs in tumor tissues were evaluated by examining levels of Foxp3 and arginase-1 mRNA, respectively. As expected, injection of CP with or without GEM decreased Foxp3 mRNA expression, and injection of GEM with or without CP decreased arginase-1 mRNA expression. Although GEM alone increased mRNA expression of IFN-γ considerably, but not significantly, CP either with or without GEM significantly increased IFN-γ mRNA, suggesting that CP is superior to GEM in restoring T cell immunity.

Fig. 6.

Effects of the combination therapy of CP and GEM on tumor-infiltrating immune cells. a BALB/c mice were injected s.c. with 5 × 105 CT-26 cells into the right flank. On day 10, mice were injected i.p. with CP and/or GEM at a dose of 50 mg/kg. Two days later, tumor tissues were collected and mRNA expression was evaluated by real-time PCR. Each group consisted of five mice. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 indicate statistical significance by Student’s t test. b Tumor tissue cell suspensions were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-Gr-1 mAb, PE-conjugated anti-CD11b mAb, and APC-conjugated anti-CD45 mAb, and the percentage of tumor-infiltrating immune cells was determined (upper, left). CD45+ cells were sub-divided (upper, right) into Gr-1low CD11b+ or Gr-1high CD11b+ cells. Each group consisted of four mice. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 indicate statistical significance by Student’s t test

We also examined tumor-infiltrating immune cells after the combination therapy by gating on CD45+ cells (Fig. 6b). The percentage of CD45+ immune cells in tumor tissues decreased after injection of either therapy, but the combination therapy decreased the percentage most efficiently. Given that the combination therapy did not have a suppressive effect on spleen cell numbers (Fig. 3a), the CP and GEM combination therapy preferentially decreased the tumor-infiltrating immune cells. When CD11b+ cells were divided into Gr-1low and Gr-1high cells, the combination therapy increased the relative percentage of Gr-1low CD11b+ cells in tumor-infiltrating CD45+ cells. In contrast, although the combination therapy failed to change the percentage of Gr-1high CD11b+ cells among the tumor-infiltrating CD45+ cells, injection of GEM significantly decreased the percentage of Gr-1high CD11b+ cells in tumor tissues.

Discussion

In this study, we determined the effects of metronomic combination chemotherapy with low-dose CP plus GEM in mitigating Treg- and MDSC-mediated immunosuppression using CT26 colon carcinoma-bearing mice. Although no significant difference in the tumor size was observed between two protocols, intermittent injections of CP (100 mg/kg) at 8-day intervals and those of CP (50 mg/kg) at 4-day intervals (Fig. 1a), the former protocol induced tumor peptide-specific T cells in draining LNs of CT26-bearing mice more efficiently than did the latter protocol (Fig. 1b). CP (50 mg/kg) administered at 4-day intervals may deplete tumor peptide-specific T cells after the second injection. Potentially, the first CP injection may destroy part of the tumor and mitigate Treg-mediated immunosuppression, resulting in efficient priming and vigorous proliferation of tumor peptide-specific T cells. Then, these T cells may be depleted by the second injection of CP. In support of this hypothesis, antigen-stimulated and proliferating T cells can be preferentially destroyed by an injection of CP [29, 30]. On the other hand, no tumor peptide-specific T cell responses were observed in draining LNs of tumor-bearing mice 8 days after the CP injection, suggesting that the Tregs re-emerged 8 days after the first CP injection. These results suggest that intermittent injections of low-dose CP, with an 8-day interval, could continuously mitigate Treg-mediated immunosuppression in CT26-bearing mice. We also compared the anti-tumor effects induced when GEM was administered at a dose of either 50 or 100 mg/kg (Fig. 2), and found that the lower dose (50 mg/kg) GEM was superior. This result indicates that GEM at 50 mg/kg is therapeutically superior to higher doses in suppressing tumor growth in vivo without impairing immunological competence.

The main purpose of this study was to determine the anti-tumor effects of metronomic combination chemotherapy with low-dose CP and GEM. To this end, we first confirmed that the combination therapy of CP (50 mg/kg) and GEM (50 mg/kg) once or twice with an 8-day interval showed no immunosuppressive effect on T cell function in vivo (Fig. 3). Although the metronomic chemotherapy with either low-dose CP or GEM alone suppressed tumor growth significantly, the tumor size was almost half of them when mice were treated with the metronomic combination chemotherapy with low-dose CP plus GEM (Fig. 4a, b). Moreover, no ‘plateau’ of suppression of tumor growth was observed when CT26-bearing nude mice were treated with the metronomic combination chemotherapy (Fig. 4c). Furthermore, one-third of CT26-bearing mice were cured after the metronomic combination chemotherapy, and they acquired protective immunity against CT26 cells (Fig. 5a), by inducing anti-CT26 specific T cells (Fig. 5b). Thus, T cells play a crucial role in the in vivo anti-tumor effects induced by the metronomic combination chemotherapy with low-dose CP plus GEM.

We examined the effects of the combined chemotherapy with low-dose CP plus GEM on the tumor microenvironment using real-time PCR (Fig. 6a). Injection of CP or GEM decreased Foxp3 and arginase-1 mRNA expression, respectively, but the combined chemotherapy with both drugs decreased arginase-1 mRNA expression most profoundly. Although MDSCs have the potential to develop tumor-induced Tregs [31, 32], injection of GEM had no definite effect on Foxp3 mRNA expression in tumor tissues. The increased expression of IFN-γ mRNA seemed dependent on CP. We also examined tumor-infiltrating immune cells, focusing on MDSCs (Fig. 6b), because there have already been many reports showing that low-dose CP can decrease Tregs in tumor-bearing hosts [17–21]. Injection of either low-dose CP and/or GEM decreased the percentage of tumor-infiltrating immune cells significantly. When MDSCs were divided into monocytic Gr-1low CD11b+ cells and granulocytic Gr-1high CD11b+ cells [33, 34], the relative percentage of Gr-1low CD11b+ monocytic MDSCs in tumor-infiltrating CD45+ immune cells increased after therapy with CP and GEM. In contrast, chemotherapy with GEM, with or without CP, significantly decreased the relative percentage of Gr-1high CD11b+ granulocytic MDSCs. These lines of evidence indicate that low-dose CP, but not GEM, restores the ability of T cells to produce IFN-γ by mitigating Treg-mediated immunosuppression, and that GEM decreased granulocytic Gr-1high CD11b+ MDSCs in the tumor microenvironment.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that metronomic chemotherapy with low-dose CP plus GEM can mitigate Treg- and MDSC-mediated immunosuppression concurrently, resulting in the in vivo induction of anti-tumor T cell immunity. Since both drugs have been widely used as anti-cancer drugs against various types of malignancies, this type of chemotherapy could be safely applied clinically with or without current anti-cancer immunotherapies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Tamami Moritani for her technical assistance. This study was supported in part by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sport, Culture, and Technology of Japan (no. 24501331 to M. H. and no. 23701074 to N. H.) and from the Shimane University Medical Education and Research Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Yamaguchi T, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells in immune surveillance and treatment of cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: linking inflammation and cancer. J Immunol. 2009;182:4499–4506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942–949. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato E, Olson SH, Ahn J, et al. Intraepithelial CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and a high CD8+/regulatory T cell ratio are associated with favorable prognosis in ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18538–18543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509182102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young MR, Wright MA, Pandit R. Myeloid differentiation treatment to diminish the presence of immune-suppressive CD34+ cells within human head and neck suqamous cell carcinomas. J Immunol. 1997;159:990–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almand B, Clark JI, Nikitina E, van Beynen J, English NR, Knight SC, Carbone DP, Gabrilovich DI. Increased production of immature myeloid cells in cancer patients: a mechanism of immunosuppression in cancer. J Immunol. 2001;166:678–689. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Onizuka S, Tawara I, Shimizu J, Sakaguchi S, Fujita T, Nakayama E. Tumor rejection by in vivo administration of anti-CD25 (interleukin-2 receptor α) monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3128–3133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ko K, Yamazaki S, Nakamura K, Nishioka T, Hirota K, Yamaguchi T, Shimizu J, Nomura T, Chiba T, Sakaguchi S. Treatment of advanced tumors with agonistic anti-GITR mAb and tits effects on tumor-infiltrating Foxp3+CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202:885–891. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishikawa H, Kato T, Hirayama M, Orita Y, Sato E, Harada N, Gnjatic S, Old LJ, Shiku H. Regulatory T cell-resistant CD8+ T cells induced by glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor signaling. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5948–5954. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serafini P, Meckel K, Kelso M, Noonan K, Califano J, Koch W, Dolcetti L, Bronte V, Borrello I. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition augments endogenous antitumor immunity by reducing myeloid-derived suppressor cell function. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2691–2702. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veltman JD, Lambers EH, Van Nimwegen M, Hendriks RW, Hoogstenden HC, Aerts JG, Hegmans JP. COX2-inhibition improves immunotherapy and is associated with decreased numbers of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in mesothelioma. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:464. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shirota Y, Shirota H, Klinman DM. Intratumoral injection of CpG oligonucleotides induces the differentiation and reduces the immunosuppressive activity of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Immunol. 2012;188:1592–1599. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obeid M, Tesniere A, Ghiringhelli F, et al. Calreticulin exposure dictates the immunogenicity of cancer cell death. Nat Med. 2007;13:54–61. doi: 10.1038/nm1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Tesniere A, et al. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nat Med. 2007;13:1050–1059. doi: 10.1038/nm1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghiringhelli F, Apetoh L, Tesniere A, et al. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in dendritic cells induces IL-1β-dependent adaptive immunity against tumors. Nat Med. 2009;15:1170–1178. doi: 10.1038/nm.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tesniere A, Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Joza N, Panaretakis T, Kepp O, Schlemmer F, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Immunogenic cancer cell death: a key-lock paradigm. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:504–511. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loeffler M, Kruger JA, Reisfeld RA. Immunostimulatory effects of low dose cyclophosphamide are controlled by inducible nitric oxide synthase. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5027–5030. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu JY, Wu Y, Zhang XS, et al. Single administration of low dose cyclophosphamide augments the antitumor effects of dendritic cell vaccine. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:1597–1604. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0305-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wada S, Yoshimura K, Hipkiss EL, et al. Cyclophosphamide augments antitumor immunity: studies in an autochthonous prostate cancer model. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4309–4318. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghiringhelli F, Larmonier N, Schmitt E, Parcellier A, Cathelin D, Garrido C, Chauffert B, Solary E, Bonnotte B, Martin F. CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress tumor immunity but are sensitive to cyclophosphamide which allows immunotherapy of established tumors to be curative. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:336–344. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roux S, Apetoh L, Chalmin F, et al. CD4+ CD25+ Tregs control the TRAIL-dependent cytotoxicity of tumor-infiltrating DCs in rodent models of colon cancer. J Clin Invest. 2008;11:3751–3761. doi: 10.1172/JCI35890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki E, Kapoor V, Jassar AS, Kaiser LR, Albelda SM. Gemcitabine selectively eliminate splenic Gr-1+/CD11b+ myeloid suppressor cells in tumor-bearing animals and enhance antitumor immune activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6713–6721. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanahan D, Bergers G, Bergsland E. Less is more, regularly: metronomic dosing of cytotoxic drugs can target tumor angiogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1045–1047. doi: 10.1172/JCI9872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamada Y, Sugimoto H, Soubasakos MA, Kieran M, Olsen BR, Lawler J, Sudhakar A, Kalluri R. Thrombospondin-1 associated with tumor microenvironment contributes to low-dose cyclophosphamide-mediated endothelial cell apoptosis and tumor growth suppression. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1570–1574. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghiringhelli F, Menard C, Puig PE, Ladoire S, Roux S, Martin F, Solary E, Le Cesne A, Zitvogel L, Chauffert B. Metronomic cyclophosphamide regimen selectively depletes CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells and restores T and NK effector functions in end stage cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:641–648. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0225-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Man S, Bocci G, Francia G, Green SK, Jothy S, Hanahan D, Bohlen P, Hicklin DJ, Bergers G, Kerbel RS. Antitumor effects in mice of low-dose (metronomic) cyclophosphamide administered continuously through the draining water. Cancer Res. 2002;15:2731–2735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Francia G, Shaked Y, Hashimoto K, et al. Low-dose metronomic oral dosing of a prodrug of gemcitabine (LY2334737) causes antitumor effects in the absence of inhibition of systemic vasculogenesis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:680–689. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang AY, Gulden PH, Woods AS, et al. The immunodominant major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted antigen of a murine colon tumor derives from an endogenous retroviral gene product. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9730–9735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eto M, Mayumi H, Tomita Y, Yoshikai Y, Nomoto K. Intrathymic clonal deletion of Vβ6+ T cells in cyclophosphamide-induced tolerance to H-2-compatible, Mls-disperate antigens. J Exp Med. 1990;171:97–113. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eto M, Mayumi H, Tomita Y, Yoshikai Y, Nisimura Y, Maeda T, Ando T, Nomoto K. Specific destruction of host-reactive mature T cells of donor origin prevents graft-versus-host disease in cyclophosphamide-induced tolerance mice. J Immunol. 1991;146:1402–1409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang B, Pan PY, Li Q, Sato AI, Levy DE, Bromberg J, Divino CM, Chen SH. Gr-1+CD115+ immature myleoid suppressor cells mediate the development of tumor-induced T regulatory cells and T-cell anergy in tumor-bearing host. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1123–1131. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Serafini P, Mgebroff S, Noonan K, Borrello I. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote cross-tolerance in B-cell lymphoma by expanding regulatory T cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5439–5449. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Youn JI, Nagaraj S, Colloazo M, Gabrilovich DI. Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol. 2008;181:5791–5802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Movahedi K, Guilliams M, Van den Bossche J, Van den Bergh R, Gysemans C, Beschin A, De Baetselier P, Van Ginderachter JA. Identification of discrete tumor-induced myleoid-derived suppressor cell subpopulations with distinct T cell-suppressive activity. Blood. 2008;111:4233–4244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.