Abstract

In this study, a xenogeneic DNA vaccine encoding for human vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (hVEGFR-2) was evaluated in two murine tumor models, the B16-F10 melanoma and the EO771 breast carcinoma model. The vaccine was administered by intradermal injection followed by electroporation. The immunogenicity and the biological efficacy of the vaccine were tested in (1) a prophylactic setting, (2) a therapeutic setting, and (3) a therapeutic setting combined with surgical removal of the primary tumor. The tumor growth, survival, and development of an immune response were followed. The cellular immune response was measured by a bioluminescence-based cytotoxicity assay with vascular endothelial growth factor-2 (VEGFR-2)-expressing target cells. Humoral immune responses were quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Ex vivo bioluminescence imaging and immunohistological observation of organs were used to detect (micro)metastases. A cellular and humoral immune response was present in prophylactically and therapeutically vaccinated mice, in both tumor models. Nevertheless, survival in prophylactically vaccinated mice was only moderately increased, and no beneficial effect on survival in therapeutically vaccinated mice could be demonstrated. An influx of CD3+ cells and a slight decrease in VEGFR-2 were noticed in the tumors of vaccinated mice. Unexpectedly, the vaccine caused an increased quantity of early micrometastases in the liver. Lung metastases were not increased by the vaccine. These early liver micrometastases did however not grow into macroscopic metastases in either control or vaccinated mice when allowed to develop further after surgical removal of the primary tumor.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-017-2046-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Breast cancer, DNA vaccination, Melanoma, Metastasis, VEGFR-2

Introduction

It is well known that the immune system is capable of recognizing tumor cells and establishing a specific long-term antitumor response [1]. Therefore, vaccination against tumor antigens holds great promise in the treatment for cancer. However, it has been difficult to translate the theoretical potential of tumor vaccines in clinical efficacy due to the capacity of tumor cells to create an immunosuppressive environment and to downregulate the expression of tumor antigens [2]. Therefore, VEGFR-2 as a vaccine target has some important advantages. Instead of the tumor cells, which are sculptured by the selective pressure of the immune system, VEGFR-2 vaccines target tumor-associated endothelial cells, which have not acquired immune evasion strategies and are not prone to the development of escape mutants [1, 3]. Secondly, an effective VEGFR-2 vaccine would be applicable to many different tumor types. Additionally, it is known that certain tumor cells also express VEGFR-2. Therefore, the antiangiogenic effect of VEGFR-2-based vaccines can be complemented by a direct antitumor action in these tumors [4]. Moreover, certain tumor-associated regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells express VEGFR-2, possibly enabling a self-enforcing mechanism of VEGFR-2-based vaccines, as depletion of these cells improves the efficacy of cancer vaccine [1, 5–7].

VEGF/VEGFR-2 targeting has been explored extensively with different treatment modalities, with some of them approved for clinical use [3]. In preclinical studies, vaccination against VEGFR-2 has also been explored [8]. In these studies, dendritic cells, DNA, or protein-based VEGFR-2 vaccines have been tested. The advantage of DNA vaccines for tumor vaccination is that the antigens are synthesized intracellularly, leading to a robust cellular immune response [9]. The majority of studies with VEGFR-2 DNA vaccines used viral, bacterial, or chemical carriers [10–19]. However, reproducible large-scale production is difficult with chemical and biological carriers, making clinical use outside a research context challenging [20, 21]. Moreover, biological carriers also raise safety concerns [22]. Vaccination with naked (i.e., unformulated) plasmid DNA (pDNA) encoding VEGFR-2 has been evaluated in a few publications [23–25]. However, the transfection efficiency of naked pDNA is very low, making this approach far from optimal. Using physical delivery methods, e.g., electroporation, it is possible to combine the manufacturing advantages of unformulated DNA vaccines with high transfection efficiency [26]. Moreover, physical delivery methods do not also have carrier-related toxicity issues. Therefore, in this study, we evaluated for the first time the vaccination efficacy after electroporation of a naked pDNA vaccine encoding human VEGFR-2 (hVEGFR-2). Human and not murine VEGFR-2 is used as antigen, because xenogeneic vaccination can help to overcome immune tolerance [27]. In this work, we also evaluate whether the VEGFR-2 DNA vaccine causes an influx of CD3+ immune cells and a drop of VEGFR-2 expression in the primary tumor. Additionally, cellular and humoral immune response as well as the development of metastases in different organs is monitored by bioluminescence imaging of excised organs, which allows the detection of micrometastases. This is necessary as it has been demonstrated, in a preclinical and clinical setting, that targeting VEGFR-2, by monoclonal antibodies as well as receptor inhibitors, can induce metastases [28–30]. In experiments with VEGFR-2 vaccines, the effect of VEGFR-2 vaccination on metastases has been insufficiently examined.

Materials and methods

Tumor cell lines, VEGFR-2 plasmid, and mice

The B16-F10 [31] and the EO771 [32] tumor cell lines were generously provided by, respectively, Johan Grooten (Department of Biomedical Molecular Biology, Ghent University, Belgium) and Jo Van Ginderachter (Cellular and Molecular Immunology, VIB, Free University of Brussels). Both cell lines were transduced with luciferase as described earlier [33]. Briefly, retroviruses were produced in human embryonic kidney (HEK293T) cells by calcium phosphate transfection, harvested after 48 and 72 h, filtered, and concentrated by ultracentrifugation. Transduction was performed in the presence of 8 µg/ml polybrene and efficiency was evaluated by bioluminescence. Both cell lines were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 1 mmol/ml l-glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). For tumor inoculation, the cells were harvested by trypsinization and washed twice with calcium- and magnesium-free Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Invitrogen). Human VEGFR-2 plasmid (cat: pblast-hflk1) was purchased from Invivogen (Toulouse, France). This pDNA contained 456 CpG motifs. The enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP)-expressing pDNA (pEGFP-N1) was a kind gift of Prof. Katrien Remaut (Ghent University) and contained 646 CpG motifs. Purification of the plasmids was done with the EndoFree Giga kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). For all experiments, C57BL/6JRj mice of 8 weeks of age were used (Janvier Breeding Center, Le Genest St. Isle, France).

Study design

The experiments were approved by the ethical committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine (Ghent University; EC-DI 2014-45). Supplementary Table 1 shows all experimental groups included in this study.

For prophylactic vaccination (supplementary Fig. 1), 56 mice were randomly allocated to four groups with each comprising 14 mice. The first and third groups (groups 1 and 3) were challenged with, respectively, B16-F10 and EO771 cells without prior vaccination. The second and fourth groups (groups 2 and 4) were vaccinated and subsequently challenged with, respectively, B16-F10 and EO771 cells. The vaccination schedule consisted of three intradermal injections (near the tail base) of 25 µg human VEGFR-2 pDNA in calcium- and magnesium-free PBS followed by electroporation with the BTX AgilePulse device (Harvard apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA) using 4-mm-gap needle electrodes. The following electroporation protocol was used: 2 pulses of 450 V with a pulse duration of 0.05 ms and a 300-ms interval, followed by 8 pulses of 100 V with a pulse duration of 10 ms and a 300-ms interval. The interval between the vaccinations was 2 weeks. One week after the final vaccination, the mice from groups 1 and 3 were subcutaneously inoculated in the right flank with 2 × 105 B16-F10 cells, while the mice from groups 2 and 4 were inoculated with 5 × 105 EO771 cells. Once weekly, tumor volume was measured with a digital caliper (formula: 1/2(length × width)2). Additionally, the bioluminescent signal of the primary tumor was also measured 10 min after intraperitoneal injection of 100 µl of d-luciferin (15 mg/ml, Goldbio Technology, St. Louis, USA) with an IVIS lumina II (Perkin-Elmer, Zaventem, Belgium). Four mice from each group were randomly selected to be sacrificed 3 weeks after tumor inoculation to isolate blood and immune cells from the spleen and to detect (micro)metastases in the excised livers and lungs via ex vivo bioluminescence imaging. The remaining mice (10 per group) were followed for tumor growth and survival and were euthanized when humane endpoints were reached. These humane endpoints included tumor size (>1 cm3), weight loss (>20%), or self-mutilation.

For therapeutic vaccination (supplementary Fig. 2), 28 mice were inoculated in the flank with 2 × 105 B16-F10 cells and another group of 28 mice with 5 × 105 E0771 cells. As soon as tumors became palpable (circa 15 mm3), mice were randomly allocated to serve as non-vaccinated control (n = 14, groups 5 and 7) or to receive the vaccination schedule (n = 14, groups 6 and 8) described above. Due to rapid tumor growth, vaccination interval was adjusted to 1 week. Tumor volume and bioluminescent signal of the primary tumor were measured weekly as described above. Four mice from each group were sacrificed 1 week after the last vaccination to measure immune responses and to screen for (micro)metastases in the livers and lungs via ex vivo bioluminescence imaging. However, because most mice in the control and vaccinated groups reached humane endpoints before this time, the mice that were sacrificed were not randomly selected as initially planned, but were instead the mice that were still alive at that time. Tumor growth and survival were analyzed for all 14 mice until the time of sacrifice, with mice sacrificed for the biological read-out censored.

In vivo electroporation of pDNA can induce the secretion of several cytokines that can affect the tumor growth. Therefore, we included a mock vaccinated control group (n = 4) in this study. For that purpose, we used a therapeutic vaccination schedule and a pDNA encoding eGFP. Eight mice were inoculated in the flank with 2 × 105 B16-F10 cells. One, two, and three weeks after inoculation, four mice were mock vaccinated. The other four mice served as non-vaccinated (untreated) control. The vaccination schedule consisted of three intradermal injections (near the tail base) of 25 μg eGFP pDNA in 40 µl sterile PBS, followed by electroporation with the BTX Agile pulse device (Harvard apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA) using 4-mm-gap needle electrodes. Tumor volume and bioluminescent signal of the primary tumor were measured weekly. Survival was analyzed for all mice until the time of sacrifice.

To study over a longer time period the effect of VEGFR-2 DNA vaccination on metastasis, we surgically removed the tumor (supplementary Fig. 3). In more detail, 20 mice were inoculated with either B16-F10 or E0771 cells as described above. When tumors became palpable, mice were randomly allocated to serve as surgery-only control (n = 10, groups 9 and 11) or surgery–vaccination group (n = 10, groups 10 and 12). At this time point, vaccination was started in the latter group and consisted of three intradermal vaccinations with a time interval of 1 week (see above). Three weeks after inoculation, primary tumors (600–1000 mm3) were surgically removed. Three weeks later, mice were sacrificed for the detection of macrometastases (visual inspection) via ex vivo bioluminescent imaging of organs (liver, spleen, and lungs).

Histology and immunohistochemistry

At the moment of euthanasia, excised tumors and lung and liver samples were fixed in 4% phosphate buffered formaldehyde, processed by standard methods, and embedded in paraffin for light microscopy. Three 5-μm serial sections were cut. The first section was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). After deparaffinization and rehydration of the remaining sections, heat-induced antigen retrieval was performed in citrate buffer (pH = 6.0). In order to block endogenous peroxidase activity and non-specific reactions, the sections were incubated for 5 min with a peroxidase blocking reagent (Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). For the identification of T lymphocytes, CD3 antigens were stained on section two using a polyclonal rabbit anti-CD3 antibody (1/100, Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). On the third section, VEGFR-2 staining was performed using a rabbit polyclonal anti-VEGFR-2 antibody (1/400; Abcam Ltd, Cambridge, UK). Those sections were further processed with Envision + System-HPR (DAB) (Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) for use with rabbit primary antibodies. During each immunohistochemical staining protocol, appropriate washing steps were included. Incubation with the CD3 and VEGFR-2 antibodies was performed at room temperature for 30 and 45 min, respectively. Visualization was performed using a Leica DM-LB2 imaging system and Leica Application Suite (LAS) 4.0.0 software.

Characterization of the immune response

In a previous study, we already characterized the immune response after vaccination of healthy mice and dogs with hVEGFR-2 pDNA [34]. In this study, the immune responses of tumor-bearing mice after vaccination with hVEGFR-2 pDNA were studied. Splenocytes were isolated after the mice were sacrificed. To assess cytotoxic response to cells expressing the target (i.e., VEGFR-2), splenocytes were coincubated with bioluminescent B16-F10 cells that had been in vitro electroporated with the VEGFR-2 pDNA (BTX ECM 830 electroporator, Harvard apparatus, Holliston, USA; 2 pulses of 140 V with a pulse duration of 5 ms and a 100-ms interval). As a control for specificity to the hVEGFR-2 target, B16-F10 melanoma cells that were mock electroporated were also included. Absence of the natural VEGFR-2 expression in the bioluminescent B16-F10 cells and induction of expression after electroporation were assessed by flow cytometry with an anti-VEGFR-2 antibody combined with an Alexa Fluor-688-conjugated secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). A cytotoxicity assay was performed by incubating 2 × 105 splenocytes with 1 × 104 B16-F10 cells [35]. After 24 h, the bioluminescent signal, which is related to the number of living cells, was measured with an IVIS lumina II (Perkin-Elmer, Zaventem, Belgium).

To assess the humoral responses, when mice were sacrificed, blood was taken by cardiac puncture under terminal anesthesia. After centrifugation of the blood, serum was collected and stored at −80 °C until analysis. To determine anti-VEGFR-2 antibodies, microtiter plates were coated with 1 µg murine VEGFR-2 protein, blocked with a blocking buffer, and loaded with serial dilutions of serum (Bio-Connect, Te Huissen, The Netherlands). After washing, a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody was added, followed by development with tetramethylbenzidine substrate and measuring the absorbance with a microplate reader at 450 nm (ImTec Diagnostics, Antwerp, Belgium). The titer was determined as the limited dilution with a signal exceeding mean plus two times the standard deviation of the signal from control samples (non-vaccinated mice).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with the SPSS software version 19 (IBM, Brussels, Belgium). The effect of vaccination on the cytotoxicity of murine splenocytes was analyzed with Student’s t test. The effect of vaccination on antibody titers was analyzed with an exact linear-by-linear association test. For post hoc tests, correction for multiple comparisons was performed with the Tukey’s test. Survival between treatment groups was compared using Kaplan–Meier analysis. Bioluminescence data were compared with one-way ANOVA after log transformation.

Results

Immune response

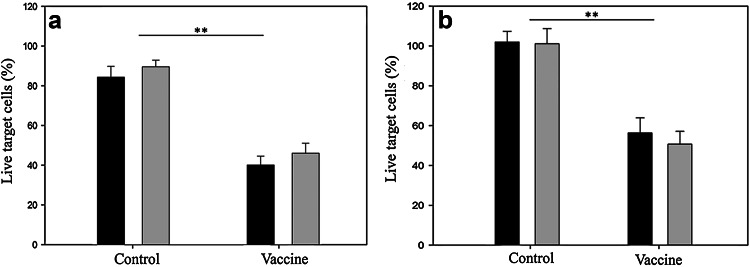

There was a significant (p = 0.001) cytotoxic T lymphocyte response in prophylactically vaccinated mice (groups 2 and 4) compared to control mice (groups 1 and 3). In more detail, 4 weeks after the last vaccination (i.e., 3 weeks after tumor inoculation) lymphocytes from the B16-F10- and EO771-challenged mice killed, on average, 44% more VEGFR-2-positive target cells than those from non-vaccinated mice (Fig. 1a). Additionally, vaccinated mice also developed a significant humoral response, with antibody titers in the vaccinated groups ranging from 1:400 to 1:1600, whereas in the control groups no antibody response could be detected (p < 0.001, supplementary Table 2).

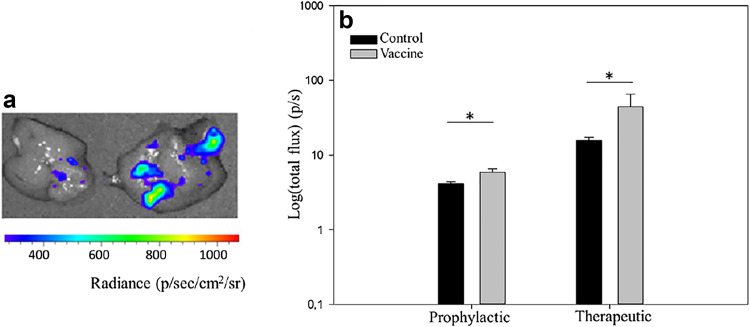

Fig. 1.

Splenocytes of control mice and prophylactically (a) or therapeutically (b) vaccinated mice were coincubated with VEGFR-2-expressing target cells. After 24 h, a significant cytotoxic response of splenocytes from vaccinated mice is evident (black B16-F10-bearing mice, gray EO771-bearing mice) (**p < 0.01). Bars represent the average (n = 3) of the percentage live target cells set along with the standard error of the mean (SEM)

A similar systemic immune response was present in the therapeutically vaccinated mice. One week after the last vaccination (i.e., 4 weeks after tumor inoculation), splenocytes from the B16-F10- and EO771-bearing mice (groups 6 and 8) killed, on average, 40% more VEGFR-2-positive targets than lymphocytes from non-vaccinated mice (groups 5 and 7, Fig. 1b). Antibody responses in the therapeutically vaccinated mice were also higher than in control mice, in which no detectable antibodies could be found (p < 0.001, supplementary Table 2). No difference in immune response between tumor models or between vaccination schedules (prophylactic/therapeutic) was evident.

Effect of prophylactic VEGFR-2 vaccination on tumor growth and survival

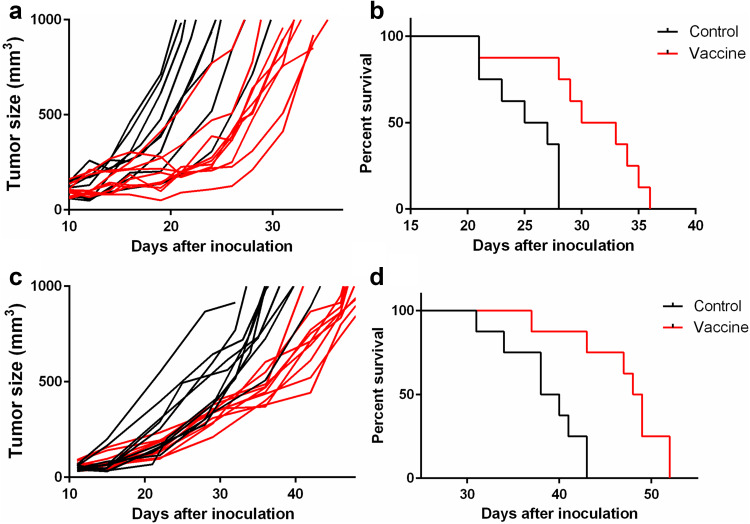

The VEGFR-2 DNA vaccine was able to slow down the growth of B16-F10 and EO771 tumors when mice were vaccinated before they were inoculated with the tumor cells (Fig. 2). The bioluminescent signal of the tumor followed a similar trend as the tumor volume (data not shown). This decrease in tumor growth led to a modest increase in survival of the vaccinated mice (Fig. 2). In detail, vaccination was able to significantly increase the median survival of B16-F10-challenged mice from 25 days to 30 days, and that of EO771-challenged mice from 38 days to 48 days (p = 0.004 and p = 0.002, respectively). However, prophylactic vaccination was not protective as all vaccinated mice developed a tumor.

Fig. 2.

Individual tumor growth curves (a, c) and survival curves (b, d) for prophylactically vaccinated and control mice inoculated with B16-F10 (a, b) and EO771 (c, d). Each group consisted of 14 mice

Effect of therapeutic VEGFR-2 vaccination on tumor growth and survival

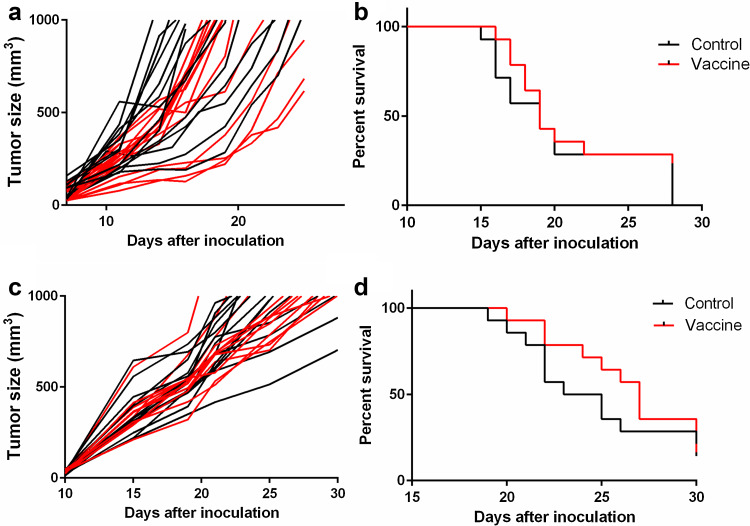

The VEGFR-2 DNA vaccine was subsequently tested in mice that already had a tumor. The volumes of the B16-F10 and EO771 tumors did not significantly decrease after vaccination with the VEGFR-2 DNA vaccine and survival was not affected by vaccination (Fig. 3). Only a proportion of mice survived long enough to receive the complete rounds of vaccinations.

Fig. 3.

Individual tumor growth curves (a, c) and survival curves (b, d) for therapeutically vaccinated and control mice inoculated with B16-F10 (a, b) and EO771 (c, d). Each group consisted of 14 mice

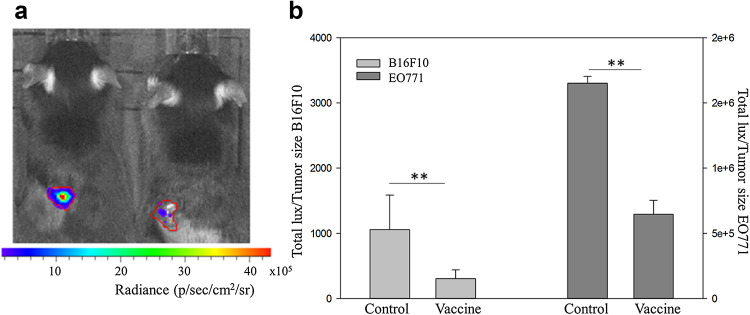

At day 27, i.e., 6 days after the last vaccination, clear differences between the bioluminescence patterns of the tumors of vaccinated and non-vaccinated were noticed (Fig. 4). Indeed, the ratio of tumor bioluminescence to tumor volume was significantly lower for vaccinated than control mice, suggesting less viable tumor mass in the vaccinated mice (p = 0.01, Fig. 4). It is important to note that these measurements are not from randomly selected mice per group, but only from mice in each group that survived up until this time point (4 control mice and 5 vaccinated mice for B16-F10 and 4 control mice and 8 vaccinated mice for EO771). At earlier time points, there was no difference in bioluminescent signal between vaccinated and non-vaccinated mice (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Average bioluminescent signals of the tumors of the therapeutically vaccinated mice, set along with the standard error of the mean (SEM). a Representative in vivo bioluminescence image of a control (left) and a vaccinated (right) B16-F10 tumor mouse, 4 weeks after tumor inoculation (i.e., 1 week after the last vaccination). b Bar chart of the ratio of tumor bioluminescence to tumor volume 1 week after the third therapeutic vaccination (n = 14 in each group, **p < 0.01; p/s/cm 2 /sr photons/second/cm2/steradian)

Effect of mock vaccination on tumor growth, survival, and influx of immune cells

In vivo electroporation of pDNA can induce the secretion of several cytokines that can affect the tumor growth. Therefore, to exclude such non-specific antitumor effects we studied in the B16-F10 model the effect of mock vaccination. For these experiments, a therapeutic vaccination treatment schedule was used as the highest effect of eventually secreted cytokines following intradermal electroporation of pDNA is expected when the tumor is already established. Our data illustrate that mock vaccination does not affect tumor growth and survival, compared to non-vaccinated (untreated) control mice (supplementary Fig. 4a, b). Furthermore, H&E staining and CD3 staining of primary tumor samples of mock vaccinated mice were compared with the corresponding samples of non-vaccinated and vaccinated mice. Immunohistochemical analysis confirmed that no differences in immune influx in primary tumors were observed between non-vaccinated mice and mock vaccinated mice (supplementary Fig. 5—panel c, d), while an influx of CD3+ immune cells was observed on H&E and CD3 staining of primary tumor samples of VEGFR-2-vaccinated mice (supplementary Fig. 5—panel a, b).

Metastases

Development of metastases in B16-F10 tumor mice

Prophylactic and therapeutic vaccination had the same effect on the development of metastases. Four weeks after the last prophylactic vaccination (i.e., 3 weeks after tumor inoculation), microscopic metastases were detected in the liver of both vaccinated and non-vaccinated control mice (Fig. 5). The metastases were visible as multiple bioluminescent spots. Remarkably, the total bioluminescent signal of these spots was significantly higher in the vaccinated than in the non-vaccinated mice (Fig. 5). Similarly, mice with established tumors before vaccination (i.e., therapeutic vaccination) had only microscopic metastases in the liver 1 week after the last vaccination (i.e., 4 weeks after tumor inoculation). Interestingly, the bioluminescent signal of the metastases in these therapeutically vaccinated mice was again significantly higher than the bioluminescent signal of the metastases of the control mice (Fig. 5). No metastases in the lungs could be detected. Histological staining and bioluminescence imaging of sentinel lymph nodes demonstrated the presence of metastatic tumor cells a few days before bioluminescent signals can be picked up in the liver (supplementary Fig. 6). This is an indication for a lymphogenic spreading of the B16-F10 tumor cells.

Fig. 5.

B16-F10 liver metastases in control, prophylactic, and therapeutic vaccinated mice. a Representative bioluminescence image of the liver of a control (left) and a vaccinated (right) mouse. b Bar chart showing the average bioluminescent signal in the livers of control mice and prophylactic and therapeutic vaccinated mice, set along with the SEM (each group contained 4 mice, *p < 0.05; p/s photons/second; p/s/cm 2 /sr photons/second/cm2/steradian)

Development of metastases in EO771 tumor mice

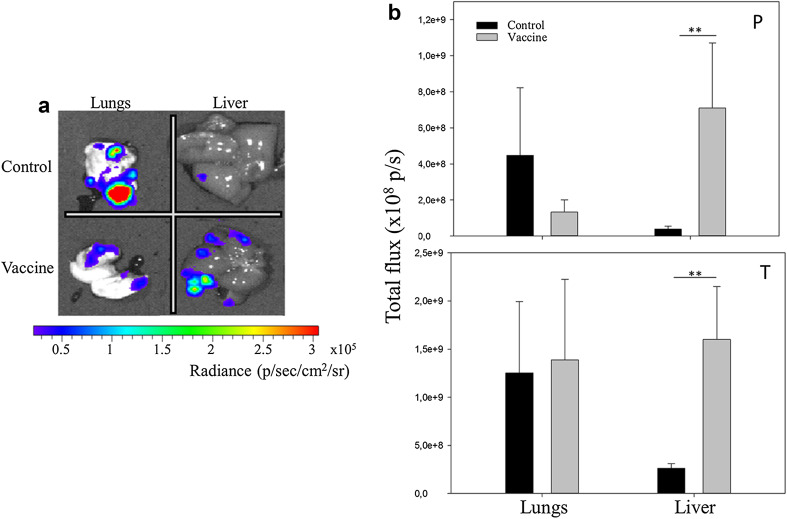

Four weeks after the last prophylactic vaccination (i.e., 3 weeks after tumor inoculation), micrometastases were detected in the liver and lung of prophylactic vaccinated and control mice. The metastases were visible as bioluminescent spots. In the prophylactically vaccinated mice, the bioluminescent signal of the lung metastases was lower in the vaccinated mice (Fig. 6a, b, P panel). In contrast, the average total bioluminescent signal of liver metastases was again significantly higher in the vaccinated than in the non-vaccinated mice (Fig. 6b, P panel). Likewise, therapeutic vaccinated mice had microscopic metastases in the liver and lung 1 week after the last vaccination (i.e., 4 weeks after tumor inoculation), and also in this tumor model the bioluminescent signal of these metastases in the liver of vaccinated mice was significantly higher than the bioluminescent signal of the liver metastases of the control mice (Fig. 6b, T panel). On the other hand, the bioluminescent signal of the lung metastases in the therapeutically vaccinated mice was not significantly different from the bioluminescent signal of the lung metastases in the control mice (Fig. 6b, T panel).

Fig. 6.

EO771 lung and liver metastases in control, prophylactic, and therapeutic vaccinated mice. a Representative bioluminescence image of the lung and liver of a control (upper row) and a vaccinated (lower row) mouse. b Bar chart showing the average bioluminescent signal in the lungs and livers of control mice and prophylactically (P panel) and therapeutically (T panel) vaccinated mice, set along with the SEM (each group contained 4 mice, **p < 0.01; p/s photons/second; p/sec/cm 2 /sr photons/second/cm2/steradian)

Long-term effect of vaccination on metastases

When metastases were allowed to develop further for 3 weeks after surgical removal of the primary tumor (6 weeks after inoculation), we found in both tumor models small macroscopic metastatic nodules in the lungs of therapeutic vaccinated mice as well as control mice. On visual inspection as well as bioluminescence measurements, there was no difference between control mice and vaccinated mice (data not shown). In the liver, the metastases remained microscopic in both tumor models. In control mice, the total bioluminescent signal of these liver metastases (6 weeks after inoculation) was increased in comparison with earlier time points (3 and 4 weeks after inoculation). In vaccinated mice, there was no further increase in bioluminescent signal of the liver micrometastases compared to earlier time points. As a consequence, the bioluminescent signals of the metastases in the livers and lungs were not significantly different between vaccinated and control mice 3 weeks after the removal of the primary tumor. This was true for both tumor models.

Effect of vaccination on VEGFR-2 expression

VEGFR-2 staining occurred on fixed samples of primary B16-F10 tumors. A slightly less intense VEGFR-2 expression in the blood vessels of B16-F10 tumors of prophylactic vaccinated mice was noticed (supplementary Fig. 7). Consequently, this may indicate that VEGFR-2 vaccination slightly reduces the amount of VEGFR-2 in tumor blood vessels.

Discussion

In this study, VEGFR-2 vaccination was evaluated in three different settings in two tumor models (B16-F10 and EO771). The three settings we tested were (1) prophylactic vaccination, (2) therapeutic vaccination, and (3) therapeutic vaccination in combination with surgery. In a prophylactic setting, survival of vaccinated mice was modestly increased. In a therapeutic setting, only a small proportion of mice survived long enough to receive the complete rounds of vaccinations, as both B16-F10 and EO771 are very aggressive tumor models. The time necessary to develop an antitumor immune response and associated clinical benefit is also an issue in clinical immunotherapy [2]. Although tumor size was comparable between control and vaccinated animals after therapeutic vaccination, the ratio of bioluminescent signal to tumor volume was significantly different. This confirms that classical volumetric tumor measurements are not ideal to detect a treatment effect of anti-VEGF/VEGFR-2 agents [36]. Histology of primary B16-F10 tumors showed small necrotic zones in the tumors of vaccinated mice (supplementary Fig. 8). In necrotic cells, the bioluminescent signal will be reduced or vanished because dead cells do not produce ATP which is needed for the conversion of D-luciferin by luciferase. Therefore, these necrotic zones might explain the lower bioluminescent signal of the primary tumor in the therapeutically vaccinated mice, but this needs to be confirmed in future experiments. Our finding corresponds with other reports of loss of viable tumor mass without significant alterations in tumor size measurements after treatment with anti-VEGF/VEGFR agents [36]. Although it is difficult to compare between studies, as often tumor type and vaccination scheme are different, our effect on primary tumor growth and survival seems less than that for other VEGFR-2 vaccine formulations. This coincides with a more limited humoral immune response in our study compared with others, whereas cellular immune responses are comparable. This link between humoral immune response and clinical efficacy of VEGFR-2 vaccination is confirmed by the study of Xu [23]. In this study, mice were also vaccinated with naked plasmid, but without electroporation, and they observed a low humoral response associated with only a limited effect on tumor growth. After conjugation with the C3d molecular adjuvant, humoral responses were markedly increased and this corresponded with a much more pronounced effect on tumor growth. Limited humoral immune responses after DNA vaccination are due to the fact that only very small amounts of proteins are secreted [37]. Improving humoral immunity of our vaccine, without losing the advantage of a safe and easy-to-manufacture formulation, could be attempted by increasing DNA dose, including a secretion signal, combining it with a protein vaccine or incorporating molecular adjuvants [24, 38, 39]. Wentink et al. showed that correctly folded peptides are able to induce antibodies that neutralize VEGF and inhibit tumor angiogenesis [40]. In our study, the vaccination with a DNA encoding human VEGFR-2 also induced antibodies and it is likely that these also blocked the VEGF–VEGFR2 signaling like in the work of Wentink et al. At an early time point (i.e., 3–4 weeks after tumor inoculation), liver micrometastases were, compared to non-vaccinated controls, significantly higher in both tumor models after prophylactic and therapeutic vaccination. In contrast, the micrometastases in the lungs of EO771 mice were not significantly different between prophylactic/therapeutic vaccinated and non-vaccinated mice. Based on these observations, it seems that the seeding of circulating tumor cell (CTC) in the liver is easier in vaccinated mice than in control mice. Probably, CTCs of VEGFR-2-vaccinated mice are more adapted to a hypoxic environment than the CTCs of non-vaccinated mice, and this allows them to proliferate sooner after dissemination in the liver, which is known to be a relatively hypoxic organ [41]. On the other hand, the lungs have high basal levels of oxygen perfusion. In such an oxygen-rich environment, CTCs of vaccinated mice, which are adapted to a hypoxic milieu, do not have an advantage over CTC of non-vaccinated mice for colonization [41]. This may explain the differential effect of VEGFR-2 vaccination on lung and liver metastases. It has been demonstrated in the past that hypoxia in the primary tumor caused by antiangiogenic treatment can influence multiple crucial steps in the metastatic process [36, 42]. Additionally, an association between hypoxic markers in the primary tumor and liver metastases has been demonstrated earlier [43]. Our observation is also in line with the work of Pàez-Ribes and others and Ebos and others who reported that antiangiogenic therapies increase local invasion and distant metastasis [28, 44].

We report, to our knowledge, for the first time that VEGFR-2 vaccination promotes early liver metastases. In the past, the effect of VEGFR-2 vaccination on spontaneously arising metastases has been investigated in three studies. However, only metastases in the lungs and not the livers were examined in these studies [11, 15, 45]. The other studies that investigated the effect of VEGFR-2 vaccination on metastasis used an experimental metastasis model that consisted of the injection of tumor cells in the tail vein [10, 12, 13, 16, 18, 46, 47]. With such metastatic models, it is not possible to evaluate the effect of treatments that modulate the metastatic capacity of CTC originating from a primary tumor.

When metastases were allowed to develop further after surgical removal of the primary tumor, both EO711 and B16-F10 tumor-bearing mice developed macroscopic lung metastases, while the liver metastases stayed microscopic. Interestingly, the micrometastases in the liver of control animals increased to the same level as those in vaccinated mice, whose metastases had not increased compared to earlier time points. This indicates that for B16-F10 and EO771 cells the liver is not an adequate metastatic site for the development of macroscopic metastases, which is in agreement with the previous findings [48, 49]. The higher metastatic capacity of tumor cells from VEGFR-2-vaccinated mice thus only applies for initial colonization of the liver, but not for macroscopic tumor growth. Indeed, formation of micrometastases is a result of the capacity to survive in the foreign environment of the distant organ, whereas the formation of macroscopic metastases is another process depending on many other factors [50]. So in the long term no overall increase in liver metastases between VEGFR-2-vaccinated and control mice was observed. Furthermore, no difference in the development of lung metastases between control and vaccinated animals was observed, in contrast to previous studies that found decreased lung metastases in VEGFR-2-vaccinated mice [11, 15, 45]. Next to different tumor types used in the other studies compared to ours, another possible explanation is the time of read-out. Metastatic tumor nodules in our experiment were considerably smaller than those reported in other studies. It is possible that the effect of VEGFR-2 vaccination on metastases becomes more pronounced with increasing metastatic tumor size, as the dependence on neovascularization will increase accordingly.

In summary, the VEGFR-2 DNA vaccine resulted in a limited effect on primary tumor growth, which may be enhanced by adjusting the vaccine or vaccination schedule to induce a more potent humoral immune response. Interestingly, for the first time, we have shown VEGFR-2 vaccination to affect metastatic behavior, in two different tumor models. This consisted of the accelerated occurrence of liver micrometastases. As for both tumor models the liver is not an adequate site for the development of macrometastases, the clinical consequences of this phenomenon cannot be evaluated. Therefore, it would be highly interesting to investigate this in tumor models with the liver as the preferential site of metastasis. Moreover, further research regarding the mechanisms behind this process could identify antimetastatic complementary treatments, which may significantly improve the efficacy of VEGFR-2 vaccination as well as other antiangiogenic treatment.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant of Ghent University and by grants from the Fonds Wetenschappelijk onderzoek (G.0235.11N and G.0621.10N). The technical assistance of Sarah Loomans was greatly appreciated (Department of Pathology, Bacteriology and Avian Diseases, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ghent University).

Abbreviations

- CTC

Circulating tumor cells

- eGFP

Enhanced green fluorescent protein

- hVEGFR-2

Human vascular endothelial growth factor-2

- IVIS

In vivo imaging system

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- pDNA

Plasmid DNA

- VEGFR-2

Vascular endothelial growth factor-2

Authors’ contributions

SD and NNS conceived and designed the experiments. SD performed the experiments and together with NNS drafted the initial submission. BL managed the revision of the paper and together with NNS drafted the revised manuscript. HH and JDT assisted with the immunizations and the follow-up of the mice during the revision. SMC produced the pDNA vaccine and inoculated the mice during the revision. LC was involved in the immunizations of the initial submission. FC and MS assisted with the histology and immunohistochemistry.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All experiments involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution or practice at which the studies were conducted. The experiments were approved by the ethical committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine (Ghent University, Belgium; EC-DI 2014-45).

Informed consent

No patients were involved in this study.

Footnotes

Sofie Denies and Bregje Leyman contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Swann JB, Smyth MJ. Review series Immune surveillance of tumors. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1137–1146. doi: 10.1172/JCI31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lesterhuis WJ, Haanen JB, Punt CJ. Cancer immunotherapy—revisited. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:591–600. doi: 10.1038/nrd3500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wentink MQ, Huijbers EJ, de Gruijl TD, Verheul HM, Olsson AK, Griffioen AW. Vaccination approach to anti-angiogenic treatment of cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1855:155–171. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goel HL, Mercurio AM. VEGF targets the tumour cell. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:871–882. doi: 10.1038/nrc3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang L, DeBusk LM, Fukuda K, Fingleton B, Green-Jarvis B, Shyr Y, Matrisian LM, Carbone DP, Lin PC. Expansion of myeloid immune suppressor Gr+ CD11b+ cells in tumor-bearing host directly promotes tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki H, Onishi H, Wada J, Yamasaki A, Tanaka H, Nakano K, Morisaki T, Katano M. VEGFR2 is selectively expressed by FOXP3high CD4+ Treg. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:197–203. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terme M, Pernot S, Marcheteau E, Sandoval F, Benhamouda N, Colussi O, Dubreuil O, Carpentier AF, Tartour E, Taieb J. VEGFA-VEGFR pathway blockade inhibits tumor-induced regulatory T-cell proliferation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:539–549. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matejuk A, Leng Q, Chou ST, Mixson AJ. Vaccines targeting the neovasculature of tumors. Vasc Cell. 2011;3:7. doi: 10.1186/2045-824X-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris LF, Ribas A. Therapeutic cancer vaccines. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2007;16:819–831. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong J, Yang J, Chen MQ, Wang XC, Wu ZP, Chen Y, Wang ZQ, Li M. A comparative study of gene vaccines encoding different extracellular domains of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 in the mouse model of colon adenocarcinoma CT-26. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:502–509. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.4.5477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie K, Bai RZ, Wu Y, Liu Q, Liu K, Wei YQ. Anti-tumor effects of a human VEGFR-2-based DNA vaccine in mouse models. Genet Vaccines Ther. 2009;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1479-0556-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, Wang Y, Wu Y, Ding ZY, Luo XM, Zhong WN, Liu J, Xia XY, Deng GH, Deng YT, Wei YQ, Jiang Y. Mannan-modified adenovirus encoding VEGFR-2 as a vaccine to induce anti-tumor immunity. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140:701–712. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1606-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jellbauer S, Panthel K, Hetrodt JH, Rüssmann H. CD8 T-cell induction against vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 by Salmonella for vaccination purposes against a murine melanoma. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34214. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu XL, Jiang XB, Liu RE, Zhang SM. The enhanced anti-angiogenic and antitumor effects of combining flk1-based DNA vaccine and IP-10. Vaccine. 2008;26:5352–5357. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niethammer AG, Xiang R, Becker JC, Wodrich H, Pertl U, Karsten G, Eliceiri BP, Reisfeld RA. A DNA vaccine against VEGF receptor 2 prevents effective angiogenesis and inhibits tumor growth. Nat Med. 2002;8:1369–1375. doi: 10.1038/nm1202-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seavey MM, Maciag PC, Al-Rawi N, Sewell D, Paterson Y. An anti-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2/fetal liver kinase-1 Listeria monocytogenes anti-angiogenesis cancer vaccine for the treatment of primary and metastatic Her-2/neu+ breast tumors in a mouse model. J Immunol. 2009;182:5537–5546. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang YS, Wang GQ, Wen YJ, Wang L, Chen XC, Chen P, Kan B, Li J, Huang C, Lu Y, Zhou Q, Xu N, Li D, Fan LY, Yi T, Wu HB, Wei YQ. Immunity against tumor angiogenesis induced by a fusion vaccine with murine beta-defensin 2 and mFlk-1. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6779–6787. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou H, Luo Y, Mizutani M, Mizutani N, Reisfeld RA, Xiang R. T cell-mediated suppression of angiogenesis results in tumor protective immunity. Blood. 2005;106:2026–2032. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-0969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan J, Jia R, Song H, Liu Y, Zhang L, Zhang W, Wang Y, Zhu Y, Yu J. A promising new approach of VEGFR2-based DNA vaccine for tumor immunotherapy. Immunol Lett. 2009;126:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niidome T, Huang L. Gene therapy progress and prospects: nonviral vectors. Gene Ther. 2002;9:1647–1652. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu L, Anchordoquy T. Drug delivery trends in clinical trials and translational medicine: challenges and opportunities in the delivery of nucleic acid-based therapeutics. J Pharm Sci. 2011;100:38–52. doi: 10.1002/jps.22243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baban CK, Cronin M, O’Hanlon D, O’Sullivan GC, Tangney M. Bacteria as vectors for gene therapy of cancer. Bioeng Bugs. 2010;1:385–394. doi: 10.4161/bbug.1.6.13146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang PH, Zhang KQ, Xu GL, Li YF, Wang LF, Nie ZL, Ye J, Wu G, Ge CG, Jin FS. Construction of a DNA vaccine encoding Flk-1 extracellular domain and C3d fusion gene and investigation of its suppressing effect on tumor growth. CII. 2010;59:93–101. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0727-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu GL, Zhang KQ, Guo B, Zhao TT, Yang F, Jiang M, Wang QH, Shang YH, Wu YZ. Induction of protective and therapeutic antitumor immunity by a DNA vaccine with C3d as a molecular adjuvant. Vaccine. 2010;28:7221–7227. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKinney KA, Al-Rawi N, Maciag PC, Banyard DA, Sewell DA. Effect of a novel DNA vaccine on angiogenesis and tumor growth in vivo. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136:859–864. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wells DJ. Gene therapy progress and prospects: electroporation and other physical methods. Gene Ther. 2004;11:1363–1369. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strioga MM, Darinskas A, Pasukoniene V, Mlynska A, Ostapenko V, Schijns V. Xenogeneic therapeutic cancer vaccines as breakers of immune tolerance for clinical application: to use or not to use? Vaccine. 2014;32:4015–4024. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pàez-Ribes M, Allen E, Hudock J, Takeda T, Okuyama H, Viñals F, Inoue M, Bergers G, Hanahan D, Casanovas O. Antiangiogenic therapy elicits malignant progression of tumors to increased local invasion and distant metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:220–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plimack ER, Tannir N, Lin E, Bekele BN, Jonasch E. Patterns of disease progression in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients treated with antivascular agents and interferon: impact of therapy on recurrence patterns and outcome measures. Cancer. 2009;115:1859–1866. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zuniga RM, Torcuator R, Jain R, Anderson J, Doyle T, Ellika S, Schultz L, Mikkelsen T. Efficacy, safety and patterns of response and recurrence in patients with recurrent high-grade gliomas treated with bevacizumab plus irinotecan. J Neurooncol. 2009;91:329–336. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9718-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Overwijk WW, Restifo NP. B16 as a mouse model for human melanoma. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2001 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im2001s39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnstone CN, Smith YE, Cao Y, Burrows AD, Cross RS, Ling X, Redvers RP, Doherty JP, Eckhardt BL, Natoli AL, Restall CM, Lucas E, Pearson HB, Deb S, Britt KL, Rizzitelli A, Li J, Harmey JH, Pouliot N, Anderson RL. Functional and molecular characterisation of EO771.LMB tumours, a new C57BL/6-mouse-derived model of spontaneously metastatic mammary cancer. Dis Model Mech. 2015;8:237–251. doi: 10.1242/dmm.017830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Denies S, Cicchelero L, Van Audenhove I, Sanders NN. Combination of interleukin-12 gene therapy, metronomic cyclophosphamide and DNA cancer vaccination directs all arms of the immune system towards tumor eradication. J Control Release. 2014;187:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Denies S, Cicchelero L, Polis I, Sanders NN. Immunogenicity and safety of xenogeneic vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 DNA vaccination in mice and dogs. Oncotarget. 2016;7(10):10905–10916. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karimi MA, Lee E, Bachmann MH, Salicioni AM, Behrens EM, Kambayashi T, Baldwin CL. Measuring cytotoxicity by bioluminescence imaging outperforms the standard chromium-51 release assay. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moserle L, Casanovas O. Anti-angiogenesis and metastasis: a tumour and stromal cell alliance. J Intern Med. 2013;273:128–137. doi: 10.1111/joim.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Otten GR, Doe B, Schaefer M, Chen M, Selby MJ, Goldbeck C, Hong M, Xu F, Ulmer JB. Relative potency of cellular and humoral immune responses induced by DNA vaccination. Intervirology. 2000;43:227–232. doi: 10.1159/000053990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deck RR, DeWitt CM, Donnelly JJ, Liu MA, Ulmer JB. Characterization of humoral immune responses induced by an influenza hemagglutinin DNA vaccine. Vaccine. 1997;15:71–78. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(96)00101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J, Valentin A, Kulkarni V, Rosati M, Beach RK, Alicea C, Hannaman D, Reed SG, Felber BK, Pavlakis GN. HIV/SIV DNA vaccine combined with protein in a co-immunization protocol elicits highest humoral responses to envelope in mice and macaques. Vaccine. 2013;31:3747–3755. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wentink MQ, Hackeng TM, Tabruyn SP, Puijk WC, Schwamborn K, Altschuh D, Meloen RH, Schuurman T, Griffioen AW, Timmerman P. Targeted vaccination against the bevacizumab binding site on VEGF using 3D-structured peptides elicits efficient antitumor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:12532–12537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1610258113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sullivan WJ, Christofk HR. The metabolic milieu of metastases. Cell. 2015;160:363–364. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu X, Kang Y. Hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factors: master regulators of metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5928–5935. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uemura M, Yamamoto H, Takemasa I, Mimori K, Mizushima T, Ikeda M, Sekimoto M, Doki Y, Mori M. Hypoxia-inducible adrenomedullin in colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:507–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ebos JM, Lee CR, Cruz-Munoz W, Bjarnason GA, Christensen JG, Kerbel RS. Accelerated metastasis after short-term treatment with a potent inhibitor of tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y, Wang M-N, Li H, King KD, Bassi R, Sun H, Santiago A, Hooper AT, Bohlen P, Hicklin DJ. Active immunization against the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor flk1 inhibits tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1575–1584. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu JY, Wei YQ, Yang L, Zhao X, Tian L, Hou JM, Niu T, Liu F, Jiang Y, Hu B, Wu Y, Su JM, Lou YY, He QM, Wen YJ, Yang JL, Kan B, Mao YQ, Luo F, Peng F. Immunotherapy of tumors with vaccine based on quail homologous vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2. Blood. 2003;102:1815–1823. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zuo SG, Chen Y, Wu ZP, Liu X, Liu C, Zhou YC, Wu CL, Jin CG, Gu YL, Li J, Chen XQ, Li Y, Wei HP, Li LH, Wang XC. Orally administered DNA vaccine delivery by attenuated Salmonella typhimurium targeting fetal liver kinase 1 inhibits murine Lewis lung carcinoma growth and metastasis. Biol Pharm Bull. 2010;33:174–182. doi: 10.1248/bpb.33.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ewens A, Mihich E, Ehrke MJ. Distant metastasis from subcutaneously grown E0771 medullary breast adenocarcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:3905–3915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Winkelmann CT, Figueroa SD, Rold TL, Volkert WA, Hoffman TJ. Microimaging characterization of a B16-F10 melanoma metastasis mouse model. Mol Imaging. 2006;5:105–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valastyan S, Weinberg RA. Tumor metastasis: molecular insights and evolving paradigms. Cell. 2011;147:275–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.