Abstract

Gamma delta T cells (GDTc) comprise a small subset of cytolytic T cells shown to kill malignant cells in vitro and in vivo. We have developed a novel protocol to expand GDTc from human blood whereby GDTc were initially expanded in the presence of alpha beta T cells (ABTc) that were then depleted prior to use. We achieved clinically relevant expansions of up to 18,485-fold total GDTc, with 18,849-fold expansion of the Vδ1 GDTc subset over 21 days. ABTc depletion yielded 88.1 ± 4.2 % GDTc purity, and GDTc continued to expand after separation. Immunophenotyping revealed that expanded GDTc were mostly CD27-CD45RA- and CD27-CD45RA+ effector memory cells. GDTc cytotoxicity against PC-3M prostate cancer, U87 glioblastoma and EM-2 leukemia cells was confirmed. Both expanded Vδ1 and Vδ2 GDTc were cytotoxic to PC-3M in a T cell antigen receptor- and CD18-dependent manner. We are the first to label GDTc with ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) nanoparticles for cellular MRI. Using protamine sulfate and magnetofection, we achieved up to 40 % labeling with clinically approved Feraheme (Ferumoxytol), as determined by enumeration of Perls’ Prussian blue-stained cytospins. Electron microscopy at 2,800× magnification verified the presence of internalized clusters of iron oxide; however, high iron uptake correlated negatively with cell viability. We found improved USPIO uptake later in culture. MRI of GDTc in agarose phantoms was performed at 3 Tesla. The signal-to-noise ratios for unlabeled and labeled cells were 56 and 21, respectively. Thus, Feraheme-labeled GDTc could be readily detected in vitro via MRI.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-012-1353-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Gamma delta T cell expansion, Gamma delta T cell cytotoxicity, Iron labeling, Preclinical cellular immunotherapy

Introduction

Gamma delta T cells (GDTc) are immunosurveillance cells, recognizing a broad range of peptide and non-peptide antigens derived from foreign microorganisms or endogenous cellular products induced by infection or cellular transformation [1]. GDTc constitute 2–5 % of circulating lymphocytes [2] and are promising candidates for adoptive immunotherapy as they elicit cytolytic responses against a variety of allogeneic and autologous tumors in vitro and in vivo [2–7]. The majority of circulating GDTc in North Americans and Europeans are of the Vγ9 Vδ2 (Vδ2) subset activated by a number of hematologic malignancies [8–11], while Vδ1 comprises a minor subset in blood.

We recently showed that expanded purified human GDTc isolated from peripheral blood exhibit cytotoxicity against human leukemia cell lines [12, 13]. Here, we demonstrate even greater expansion capacity of GDTc, including that of the Vδ1 subset, for use in cytotoxicity, cell tracking and therapy studies. Furthermore, we explore the immunophenotype of expanded cells. Gioia et al. [14] demonstrated that the loss of CD27 expression on Vδ2 corresponded to increased secretion of the potent immunostimulatory cytokine IFN-γ [13]. Dieli et al. [15] demonstrated immediate effector functions for memory CD45RA-CD27- and terminally differentiated CD45RA+CD27− human GDTc.

Vδ2 GDTc have been reported cytotoxic to PC-3 prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo [16, 17]; however, Vδ1 cytotoxicity against these cells has not yet been explored. Additionally, in vivo expansion of GDTc in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer has been deemed safe [17]. Since GDTc are also known to kill glioblastoma [18–20] reviewed in [21], and Ph+ leukemia cells [10, 12, 13], we selected an example of each as targets to further validate GDTc cytotoxicity.

While adoptive immunotherapy using GDTc is currently under investigation in clinical trials and preliminary results are promising [22–25], it is largely unknown whether infused GDTc migrate or “home” to their targets. Only Nicol et al. [26] have described localization of GDTc in humans post-infusion by Indium111 oxine labeling and subsequent detection via full-body gamma camera imaging. While GDTc migrated to lungs, liver and spleens of patients, encouragingly, they were also found in metastatic tumor sites in some individuals [26].

Cellular MRI is a newly emerging field of imaging research that uses magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) along with cellular imaging probes (typically iron particles) to monitor the fate of cells in vivo. MRI is ideally suited for tracking cells because it does not use ionizing radiation, allowing repeated longitudinal imaging and because it produces images with superior contrast and spatial resolution compared to PET or SPECT. We have successfully labeled and imaged a wide range of cell types, including natural killer cells [27], dendritic cells [28, 29], mesenchymal stromal cells [30], islets [31], macrophages [32, 33], glioma [34], melanoma [35] and breast cancer [36–38].

There are currently no reports of GDTc labeling with iron particles and only a handful documenting successful labeling of primary conventional CD4+ or CD8+ human alpha beta T cells (ABTc) [39–43]. Varying degrees of iron oxide uptake have been reported for these cells using agents such as protamine sulfate [42, 43], lipofectamine [40] or by using derivatized HIV-tat-USPIO conjugates [39, 44]. Most recently, Liu et al. [45] have reported over 90 % labeling efficiency of rat primary T cells and the human ABTc line, Jurkat. While these results are promising, the IOPC-NH2 contrast agent is not clinically approved.

Labeling primary human GDTc poses several challenges, including inter-donor variability, non-adherence to plastic, growth in colonies with a necessity for cell–cell contact as well as limited lifespan and the propensity to undergo activation-induced cell death. We have successfully labeled primary human GDTc with the clinically approved ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) Feraheme and detected these cells by cellular MRI, constituting the first step toward a clinical protocol.

Results

GDTc expansion

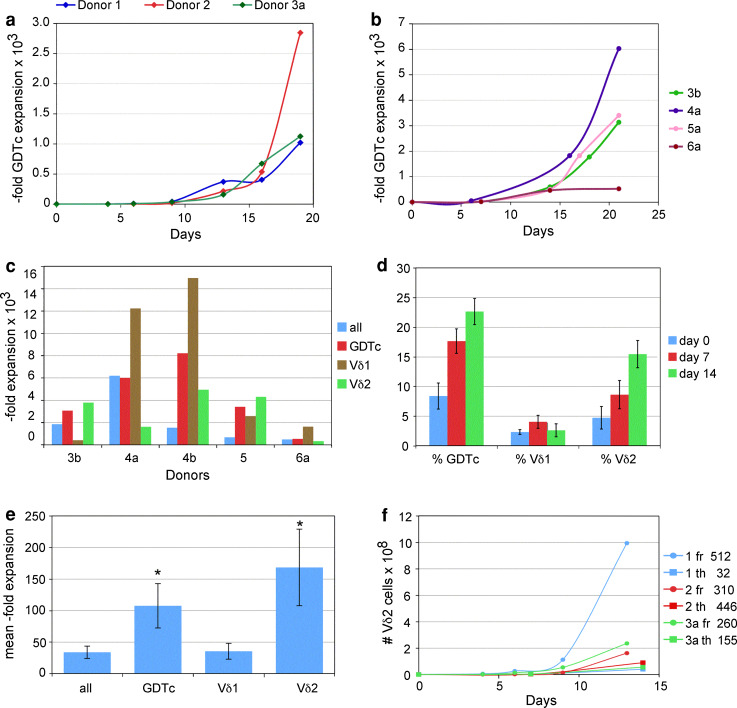

We recently demonstrated the role of the T cell mitogen Concanavalin A (ConA) in expanding isolated and purified human GDTc from the peripheral blood of healthy donors [12, 13]. Here, we attempted to achieve GDTc expansion in the presence of ABTc prior to purification. In initial GDTc cultures derived from three healthy donors, we obtained overall GDTc expansions up to 2,846-fold (Fig. 1a, donor 2) after 19 days of culture. Even greater Vδ1 and Vδ2 subset expansions could be achieved, depending on the donor (Table 1). For example, after 21 days, donor culture 4e expanded Vδ1 cells 24,384-fold. While donors 4 and 6 expanded the Vδ1 subset preferentially, this did not necessarily translate into Vδ1 prevalence in culture, since %Vδ1 on d0 was typically extremely low; d0 %Vδ1 for donor 4 averaged 0.21 ± 0.03 % (n = 4, Table 1). While expansion of Vδ1 was 15,526-fold and Vδ2 only 6,630-fold, on day 21, there were 7.4 × 109 Vδ2 compared to 2.2 × 109 Vδ1 for donor culture 6, by virtue of a much higher starting number of Vδ2 cells (1.1 × 106 Vδ2 compared to 1.4 × 105 Vδ1). In all cases, GDTc expansion was much greater than bulk cell expansion. When we compared GDTc expansion protocols in parallel, we found much greater expansions in the context of mixed T-cell cultures than those obtained from our previous protocol, with GDTc positively selected on day 0 (Supplementary Table S1). In our next experiments, after expanding GDTc from fresh blood samples for 6–13 days, we depleted ABTc using phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-alpha beta TCR antibody followed by anti-PE beads to achieve GDTc purities of 88.1 ± 4.2 % (n = 6, ±standard deviation). Non-GDTc were mainly ABTc that had not bound to the magnetic column. By day 21, cultures were mainly CD3+ T cells, the majority of which were GDTc (data not shown and Supplementary Figure S1). Depletion could be achieved as early as day 6 and GDTc continued to proliferate well (Fig. 1b). Vδ1 expansions of up to 14,962-fold could be obtained using this novel approach (Fig. 1c). We typically use IL-2 and IL-4 in our culture medium. When we cultured GDTc without cytokines, after 72 h, we observed decreased viability (82 % compared to 94 % via Trypan blue exclusion) but higher cell density (3.2 × 106/ml compared to 2.3 × 106/ml) compared to cytokine-treated cells; however, in another experiment, after five days, the reverse was true (data not shown). CD69 expression was greatly increased from 10.7 to 65.9 % of total GDTc in the presence of IL-2 and IL-4 (representative of three experiments, Supplementary Figure S2). While fresh cultures supported Vδ1 expansions, culturing GDTc from frozen PBMC using ConA preferentially expanded Vδ2 over time (Fig. 1d, n = 6 different donors), suggesting that Vδ1 cells did not recover from freezing and thawing. Differences in fold expansions between the two subsets neared significance (p = 0.073). While both GDTc and Vδ2 fold expansions were significantly higher than expansion of the bulk cell population, Vδ2 expansions from frozen samples appeared lower than those from fresh PBMCs, averaging only 168.5 ± 60.6 (mean ± standard error, Fig. 1e, n = 6), roughly half of that obtained from fresh cultures from donors 1–3 over 13 days at 360.6 ± 59.6 (Fig. 1f); however, the exponential growth phase in fresh cultures typically occurred after 14 days (please see Figure 1a, b). Comparing Vδ2 growth curves from fresh and thawed PBMCs from donors 1, 2 and 3a over 13–14 days, we observed greater yields from fresh cultures with up to 995 million Vδ2 in donor culture 1, yet respectable expansions of Vδ2 were obtained from thawed cultures, yielding up to 90.2 million donor 2 cells (Fig. 1f). Since this particular culture initially comprised only 0.2 million Vδ2 on day 0, expansion was 446-fold; fold expansions are indicated beside the curves.

Fig. 1.

A novel expansion protocol for human gamma delta T cells. a Gamma delta T cells expand in mixed T-cell culture. From total cell counts and flow cytometric measurement of Vδ1 and Vδ2 T-cell percentages, gamma delta T-cell numbers were calculated (here GDTc = Vδ1 + Vδ2) and fold expansions plotted. b Gamma delta T cells derived from mixed T-cell cultures depleted of ABTc can be further propagated. Fold expansions were calculated as in a. ABTc were depleted on days 6 (4a) or 7 (3b, 5a, 6a) post-culture initiation. Here, initial gamma delta T-cell numbers were normalized to 1 million. c GDTc subsets derived from mixed cultures depleted of ABTc can be further propagated. Fold expansions were calculated from cell counts and percentages of GDTc, Vδ1 and Vδ2 T cells measured via flow cytometry on days 0 and 21. ABTc were depleted as described in 1b; 4b underwent depletion on day 8. d Vδ2 cultures can be expanded from frozen peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Cells were thawed and maintained for 14 days (n = 6 different donors). On the indicated days, aliquots were removed and cells were stained for Vδ1, Vδ2 and pan-gamma delta T-cell antigen receptors and subject to flow cytometry. e Vδ2 cells expand preferentially from frozen peripheral blood mononuclear cell cultures. Average fold expansions were determined as described above. GDTc = gamma delta T cells; error bars are standard error, n = 6; *p < 0.05 compared to “all”. f Greater Vδ2 expansion from fresh compared to thawed peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Vδ2 cell numbers and expansions (indicated at right) were calculated as above to day 13 (fresh samples “fr”, circles) or day 14 (thawed samples “th”, squares). Cultures were initiated with 1.9, 0.5 and 0.9 million fresh and 1.3, 0.2 and 0.4 million thawed Vδ2 cells for donors 1, 2 and 3, respectively

Table 1.

Mixed T-cell culture supports robust GDTc expansions over 21 days

| Donor # | All exp | GDTc exp | #Vd1d21 | #Vd1d0 | Vd1 exp | #Vd2d21 | #Vd2d0 | Vd2 exp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3c | 277 | 1,573 | 24.9 | 0.08 | 312 | 499.0 | 0.27 | 1,848 |

| 4a | 1,020 | 4,551 | 1,111.5 | 0.13 | 8,550 | 367.1 | 0.21 | 1,748 |

| 4c | 460 | 4,262 | 511.0 | 0.09 | 5,678 | 626.1 | 0.17 | 3,683 |

| 4d | 2,732 | 18,485 | 1,884.9 | 0.10 | 18,849 | 2,813.7 | 0.20 | 14,069 |

| 4e | 1,773 | 13,260 | 2,926.1 | 0.12 | 24,384 | 1,507.4 | 0.24 | 6,281 |

| 6a | 2,619 | 8,119 | 2,173.7 | 0.14 | 15,526 | 7,359.2 | 1.11 | 6,630 |

| 7 | 109 | 487 | 5.4 | 0.04 | 136 | 132.8 | 0.09 | 1,476 |

Cells were counted at each feeding to determine cell numbers (#, ×106) and—fold expansions (exp) of bulk cultures (All exp). Percentages of gamma delta T cells (GDTc), Vδ1 and Vδ2 T cells were measured by flow cytometry on days 0 and day 21; from these values,fold expansions for gamma delta as well as Vδ1 and Vδ2 cells were calculated. Results from the seven cultures depicted in Fig. 1b are shown. Cultures were initiated with 10 × 106 peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Expanded GDTc are mainly effector memory cells

It was important to determine the subset prevalence and maturation status of expanded GDTc. Thus, at culture initiation (day 0) and endpoint, usually day 21, we subjected GDTc cultures to extensive immunophenotyping. Shown in Fig. 2 is an example of an expanded GDTc culture on day 21. Cells were stained with antibodies against human CD3, alpha beta TCR, Vδ1, Vδ2 and NKG2D (Fig. 2a). In this representative example from donor 6a, 93.1 % of live cells stained positively for CD3 and negatively for alpha beta TCR (Fig. 2a, top left). 31.8 % of these gated GDTc were Vδ1 and 54.8 % Vδ2 (Fig. 2a, top middle). NKG2D expression was high on expanded GDTc (Fig. 2a, top right). Using a second antibody mix and gating on GDTc-positive cells, in this example comprising 91.0 % of live cells (Fig. 2a, bottom panel, left), expression of CD27 and CD45RA classified GDTc into naïve (CD27+CD45RA+), central memory (CD27+CD45RA−), effector memory (CD27−CD45RA−) and RA+ effector memory (CD27-CD45RA+) cells (Fig. 2a, bottom middle panel). Gates were set based on FMO controls (Supplementary Fig S2). Overall percentages of GDTc in each of these categories were calculated from quadrant statistics (Fig. 2a, Table bottom right). As was true for this example at 48.1 and 46.0 %, respectively, donor cultures produced predominantly CD27-CD45RA- and CD27-CD45RA+ effector memory GDTc (Fig. 2b, brown and pink bars).

Fig. 2.

Expanded gamma delta T cells are mainly effector memory cells. a On day 21 of culture, aliquots of cultures were harvested and stained with antibodies against the indicated cell surface markers, fixed and then later acquired on an LSRII flow cytometer. A representative example from donor 6 culture a is shown here. Top left, middle Gates for alpha beta T cell antigen receptor (AB TCR), CD3, Vdelta1 (Vd1) and Vdelta2 (Vd2) were set based on unstained controls. Top right Overlaid histograms for expression of NKG2D on unstained and gated gamma delta T cells are shown; red unstained, blue gamma delta T cells. Fluorescence minus one controls were used to set gates for CD27, and CD45RA (bottom center panel and Supplementary Fig. S3). Bottom panel left The gamma delta T cell positive population was gated (as indicated). Bottom panel center based on CD27 and CD45RA expression, gamma delta T cells were classified as naïve, central memory (CM), RA+ effector memory (EMRA) and effector memory (EM). Bottom right the inset table shows percentages of expanded gamma delta T cells of each immunophenotype. b Gamma delta T-cell maturation. Percentages of naïve, central memory (CM), RA+ effector memory (EMRA) and effector memory (EM) gamma delta T cells for six 21-day donor cultures were determined as described in a. Average values for these six cultures are depicted in the final column; error bars are standard deviation

Expanded GDTc are cytotoxic to PC-3M cells in a TCR-dependent manner

Using the Calcein AM cytotoxicity assay [46], we confirmed the cytotoxicity of expanded GDTc to the metastatic variant of PC-3, PC-3M (Fig. 3a), for which we have established a prostate cancer model for MRI [47]. These cells were also cytotoxic to the glioblastoma cell line U87 and the Ph+ leukemia line EM-2 (Fig. 3a). In a 4-hour assay using day 21 donor culture 6a, comprising 51 % Vδ2 and 30 % Vδ1 cells, we detected 67.6 ± 8.1 % (mean ± standard deviation) lysis of PC-3M and 59.7 ± 4.7 % lysis of EM-2 at a 20:1 effector:target ratio. Cytotoxicity of GDTc against U87 was 56.4 ± 20.1 % at 10:1. Similar to the study by Liu et al. [16], we found both significant TCR dependence and involvement of CD18 in killing of PC-3M (Fig. 3b); preliminary data points to involvement of CD54 as well (data not shown). Mouse IgG was used as a negative control for blocking experiments. Both pan anti-gamma delta TCR antibodies blocked killing of PC-3M by nearly 50 %; Immu 510 decreased killing from 20.0 ± 2.6 to 11.3 ± 1.4, p = 0.007 and B1.1 reduced killing to 11.1 ± 2.9, p = 0.017. The most dramatic effect was seen when CD18 was blocked, resulting in a greater than twofold drop in lysis compared to the IgG control, from 20.0 ± 2.6 to 7.4 ± 3.5, p = 0.007. In contrast, the NKG2D antibody did not reduce killing (p = 0.863), suggesting no involvement of this receptor in GDTc cytotoxicity against PC-3M. Since this day 16 GDTc culture from donor 5a mainly comprised Vδ2 GDTc, blocking the Vδ2 TCR resulted in somewhat more attenuation than blocking Vδ1, although these were not significantly different (p = 0.128 for Vδ1 and p = 0.163 for Vδ2 compared to IgG). In contrast, in donor culture 4a with a high percentage of Vδ1 cells (85.1 % GDTc; of these 64.7 % Vδ1), blocking the Vδ1 TCR with antibody decreased GDTc killing of PC-3M at 10:1 by almost 50 % compared to IgG (Fig. 3c, 75.2 ± 12.4 % to 40.3 ± 6.1 %, p = 0.012), indicating that Vδ1 also kill PC-3M.

Fig. 3.

Expanded GDTc are cytotoxic to cancer cell lines. a GDTc kill prostate cancer, glioblastoma and leukemia cells. Target cells were labeled with Calcein AM, co-incubated with GDTcs for 4 h at 37 °C and then supernatants were harvested. Fluorescence release was measured and percent lysis calculated as described in “Materials and Methods”. GDTc cytotoxicity from day 21 culture 6a (30 % Vδ1, 51 % Vδ2) was tested in triplicate against prostate cancer (PC-3M), glioblastoma (U87) and leukemia (EM-2) cell lines at the indicated effector:target ratios. Error bars are standard deviation. This is representative of the following independent experiments: PC-3M (8×, 3 donors), U87 (3×, 2 donors), and EM-2 (2×, 1 donor). b GDTc cytotoxicity to PC-3M is T-cell antigen receptor- and CD18-dependent. PC-3M cells were labeled as above and pre-incubated with 1 μg anti-human CD18 antibody (clone TS1/18) or mouse IgG for 44 min at 37 °C before adding GDTcs at 20:1. Day 16 culture 5a GDTcs (14.2 % Vδ1, 77.4 % Vδ2) were incubated with 1 μg of the indicated antibodies for 48 min at 37 °C before addition of targets at 20:1. Incubation, harvesting, measurement and calculation of percent lysis were performed as in 3a. Im510 = Immu510; error bars are standard deviation for triplicates; *p < 0.05 compared to IgG. c GDTc cytotoxicity to PC-3M mediated by the Vδ1 T-cell antigen receptor. PC-3M cells were labeled as in Fig. 1a. Day 21 culture 4a GDTcs (55.1 % Vδ1, 11.7 % Vδ2) were incubated with 1 μg of the indicated antibodies for 90 min at 37 °C before addition of targets at 10:1. Incubation, harvesting, measurement and calculation of percent lysis were performed as in a. Error bars are standard deviation; *p < 0.05 compared to IgG

Labeling GDTc with iron oxide nanoparticles

In order to track GDTc with MRI, it is necessary to label them with a contrast agent. The most commonly used are iron oxide nanoparticles. With the aim of rapid translation to the clinic, we focused on GDTc labeling with the FDA-approved agent, USPIO Feraheme. While labeling transformed cells is routine, GDTc labeling proved challenging. Mere co-incubation resulted in no uptake (data not shown). Our best results were obtained with protamine sulfate combined with magnetofection, resulting in uptake efficiencies up to 40 % (Fig. 4a, donor 5a, day 17). We quickly discovered that in the presence of serum, GDTc would not take up iron (data not shown and Fig S4). This had an unfortunate impact on the viability of labeled GDTc, as they were subjected to extended periods without serum. Cells were plated in serum-free medium one day prior to labeling and were harvested a minimum of 17-h post-labeling. Shorter incubation times did not allow for sufficient iron uptake (data not shown). Notably, the culture vessel used did not seem to play a role in uptake, as labeling efficiency was unchanged whether GDTc were labeled in 24- or 6-well plates or T25 flasks (Fig S5, donor 6a). Labeling efficiencies improved when labeling was performed later in culture; day 10 cultures did not take up significant amounts of iron, ranging 3.6–14.5 % uptake, whereas labeling after day 12 resulted in improved uptake efficiency, up to 40.4 % (Fig. 4b). Higher iron load had a detrimental effect on GDTc, however, as evidenced by decreasing viabilities with increased iron uptake (Fig. 4c). For example, donor 3b cells, of which only 14.5 % were labeled with iron, were 74 % viable, yet 32.5 % of the same culture labeled five days later suffered a corresponding drop in viability to 60 %. This was not due to poorer viability in cultures over time, as these cells were 93 and 95 % viable when plated one day prior to labeling on days 10 and 15, respectively. Electron microscopy confirmed the presence of iron in the cytoplasm of labeled day 17 donor 5a cells depicted in 4a (Fig. 4d, i–iii), as well as the cytotoxic effect of an overload of iron on GDTc (Fig. 4d, iv). This corroborates the lower viabilities of GDTc cultures exhibiting greater iron uptake.

Fig. 4.

Primary human gamma delta T cells can be labeled with the clinically approved USPIO Feraheme. a Representative example of day 17 gamma delta T cells from donor culture 5a labeled with Feraheme via protamine sulfate and magnetofection. Cells were stained with Perls’ Prussian blue and eosin (blue iron, pink cytoplasm). Labeling efficiency was 40 % (average of 7 FOV at 40× magnification). The right panel is a higher magnification of the left panel. Scale bars are indicated. b Feraheme uptake efficiencies improve later in culture. Gamma delta T cells from the indicated donor cultures were labeled with Feraheme via protamine sulfate and magnetofection. Mean uptake efficiencies were determined as in a and plotted against the culture day on which the cells were labeled. Error bars are standard deviation. c Viability is inversely correlated with USPIO uptake. Culture viabilities post-labeling were determined by Trypan blue exclusion and plotted against percentage Feraheme uptake as determined in a and b. Error bars are standard deviation. The time frame during which donor cultures were labeled is indicated at the top of the graph. d i. Electron microscopy of two Feraheme-labeled gamma delta T cells from the experiment described in a at 1,650× magnification. Internalized iron particles can be seen in vesicles surrounding the nucleus; ii. 2,800× magnification of boxed cell in i; iii. 10,400× magnification of region boxed in ii; iv. 2,800× magnification of a dead gamma delta T cell with high iron load

USPIO-labeled GDTc can be visualized via cellular MRI at 3T

We then wanted to see whether iron-labeled donor 5a GDTc (depicted in Fig. 4a, d) could be visualized by MRI. We prepared agarose phantoms with unlabeled and labeled GDTc, which were scanned at 3 Tesla using a bSSFP sequence. On the MR images, we observed dark voids corresponding to USPIO-labeled cells that elicited a decrease in SNR compared with unlabeled cells (Fig. 5). The SNR of unlabeled GDTc (Fig. 5a) was 56, whereas the SNR of labeled cells was greatly reduced to 21(Fig. 5b). These data are proof of principle that iron-labeled GDTc are sufficiently labeled for detection by MRI.

Fig. 5.

Feraheme-labeled primary gamma delta T cells can be visualized via MRI at 3T. 9 × 105 day 17 gamma delta T cells from donor culture 5a unlabeled (left panel) or labeled (right panel) with Feraheme via protamine sulfate and magnetofection were harvested, fixed and then mixed with agarose and poured into 5-mm-diameter glass NMR tubes. Phantoms were scanned at 3 Tesla and signal-to-noise (SNR) ratios calculated. SNR values were 56 for unlabeled and 21 for labeled cells. This decrease in SNR corresponds to signal voids generated by internalized iron particles within the Feraheme-labeled gamma delta T cells

Discussion

We have herein described clinically relevant human GDTc expansions; in many cases, this includes dramatic Vδ1 yields, such that this subset becomes predominant or expands alongside Vδ2. Indeed, the extensive expansion of Vδ1 under these conditions further supports the previously observed preferential expansion of Vδ1 over Vδ2 with prolonged exposure to ConA attributed to increased apoptosis of Vδ2 cells early in the culture period [12].

Other groups have published expansion protocols that generate Vδ1 cells [48–55]; however, our protocol offers significant advantages. Straightforward and relatively inexpensive, GDTc require only an initial stimulation with ConA then continuous culturing in IL-2 and IL-4, in contrast to some other more complex protocols requiring antibody-coated plates [48, 53] and restimulation [53]. IL-2 and IL-4 enhanced viability and increased CD69 expression, suggesting that these cytokines activate GDTc to proliferate (Fig S1); however, IL-2 is a known T-cell mitogen that induces apoptosis of GDTc after T-cell antigen receptor stimulation [56]. Perhaps IL-4 plays a protective role in our system, similar to the anti-apoptotic role of anti-CD2 and IL-12 described by Lopez that allowed positive selection of GDTc after two weeks of mixed T-cell culture [16, 57].

In contrast to expansions using phosphoantigens or aminobisphosphonates that stimulate only Vδ2 proliferation, but to which not all respond [25, 58–60], every donor culture tested responded to our protocol (n = 10 different donors, 19 cultures, Fig. 1 and data not shown), although subset prevalence was unpredictable. Unfortunately, most groups have not directly reported the fold expansions achieved [49–52, 55]. Our total GDTc expansions in mixed T-cell culture ranged from 487- to 18,485-fold (Table 1, mean 7,248-fold, n = 7), with Vδ1 expansions as high as 24,384-fold (Table 1, mean 10,491-fold, n = 7); admittedly, GDTc expansions from ABTc-depleted cultures were not quite as high, yet still impressive (mean ± SD from data in Fig. 1c, GDTc 5,871 ± 2,407, Vδ1 9,925 ± 6,512, Vδ2 3,614 ± 1,765). Reported expansions from other protocols range from 12-fold total GDTc using PHA [54], 500- to 900-fold using the anti-CD3 antibody OKT3 [53] to 800- to 1,200-fold, in the presence of leukemic blasts [48]. Importantly, our protocol does not require the use of feeder cells in contrast to several others [48, 49, 51, 52, 55]. Feeder cells are often a combination of allogeneic PBMCs and EBV-transformed lymphoblastic cell lines (LCLs). The use of transformed cell lines poses a potential risk to patients. Thus, it is critical to ensure that LCLs are removed prior to clinical administration. Feeder-cell-free expansion of any cell type is advantageous, as it simplifies the culturing procedure. Feeder cells must be cultivated in parallel and irradiated before use; if irradiation is insufficient, feeder cells might overgrow GDTc cultures, contaminating the cell preparation. Also, less handling lowers the risk of contamination introduced during cultivation. Thus, the generation of clinically relevant numbers of GDTc without the use of feeders is much more cost-effective as well as safer.

While Vδ2 do not necessarily always undergo the same fold expansions as Vδ1, their greater initial presence in cultures explains their prevalence in several donor cultures. An additional advantage to our protocol is the availability of ABTc for use as experimental controls. One disadvantage is the necessity to remove significant numbers of ABTc prior to use in experiments. The earlier this is done, the lower the associated costs accrued for antibodies, beads and columns; the trade-off is the lesser expansion potential of GDTc as mentioned above (compare donor expansions in Table 1 where GDTc are grown in the context of ABTc throughout culture to Fig. 1c where ABTc are depleted early on in culture). The superior expansion of GDTc in the presence of ABTc is not surprising, since it has been shown that GDTc development and function are impaired in mice deficient of ABTc [61]. Alternatively, the different media and corresponding sera used in our previous and current protocols may also contribute to the observed differences in expansion potential. Positive selection of GDTc from mixed cultures is not recommended, since we found minimal further expansion of GDTc, as well as the onset of activation-induced cell death when subjected to any further stimulus (data not shown).

Importantly, Vδ2 GDTc could be expanded from frozen PBMCs with our method; unfortunately, this appears not to be the case with the Vδ1 subset. All six thawed cultures derived from different donors expanded only Vδ2 (Fig. 1d, e), despite Vδ1 predominance in one corresponding culture expanded from fresh donor 4a PBMC (Table 1 and Fig. 1c).

A further advantage of this protocol is the expansion of predominantly effector memory and RA+ effector memory GDTc, which are known to be highly cytotoxic [15, 62]. We readily confirmed the cytotoxicity of these expanded GDTc against PC-3M prostate cancer cells. Interestingly, using a GDTc culture with a high percentage of Vδ1 GDTc, we discovered that blocking the Vδ1 gamma delta TCR significantly impaired the ability of these cells to kill PC-3M (Fig. 3c). This result corroborates Vδ1 activation by epithelial tumors expressing MICA/B tumor antigens [63]. Although we have not yet tested for expression of MICA/B on PC-3M cells, this would be a logical next step in elucidating GDTc cytotoxicity mechanisms. We confirmed the results of Liu and Lopez concerning involvement of the TCR and the beta-2 integrin CD18 in GDTc killing of prostate cancer cells [16].

Here, we report the first successful labeling of GDTc with USPIO. There were a number of significant challenges to labeling GDTc, including the considerable variability among donors, non-adherence to plastic, their tendency to grow in colonies, the necessity for serum-free conditions for iron uptake and GDTc sensitivity to iron. Removal of serum before labeling resulted in semi-adherence to culture dishes and may have increased overall uptake as cells entered starvation mode. While most report that USPIO labeling of human cell lines does not compromise cell viability, a recent study showed adverse effects of iron oxide nanoparticles on human bone marrow cells [64]. It should be noted, however, that this group exposed human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells to label for a full 72 h, three times the standard incubation time of 24 h. Our labeling times varied from 17 to 24 h; however, even this relatively short time still induced a decrease in viability from mid-90s prior to plating for labeling to 45–70 % post-harvest (Fig. 4c, S4). While there is little published about the iron sensitivity of GDTc, Brekelmans et al. [65] observed that, unlike ABTc, GDTc do not depend on iron uptake for proliferation and maturation, leading us to speculate that GDTc may simply not be equipped to handle larger quantities of iron. Since viability was best in T25 flasks (Fig S2), we recommend their use for labeling large numbers of cells (at 10–15 million/flask) as minimal handling is required for harvesting. The optimal time to label cells appeared to be after day 12 (Fig. 4b), at which time most cell cultures had recovered from ABTc depletion and begun to enter an exponential growth phase (Fig. 1b). Indeed, it is plausible that high percentages of activated GDTc take up iron initially, but that it is quickly diluted out due to rapid proliferation. Additionally, it would be of interest to explore whether one of the subsets, Vδ1 or Vδ2, preferentially takes up iron. This could explain some of the differences observed in uptake efficiencies among donor cultures. Our GDTc labeling efficiency of 40 %, while not ideal, does not preclude the use of these cells in vivo, as they may be magnetically sorted prior to use to ensure a population of 100 % iron-positive cells, a strategy we use routinely for dendritic cell labeling prior to MRI [28].

We felt it important to demonstrate proof of principle that less than 1 million iron-labeled GDTc can be easily detected in vitro via MRI, yet the necessity to overcome issues with cell viability post-labeling cannot be overstated. It is crucial to minimize loss of iron that could be taken up by resident phagocytic cells in vivo leading to false-positive results. Once this hurdle is overcome, the next steps are functional validation in vitro followed by injection of iron-labeled GDTc into murine preclinical cancer models. This will allow us to investigate whether GDTc can be tracked to tumors and enable use of in vivo MRI to optimize dosing and route of injection for future clinical translation.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement Human blood samples were collected from healthy adult donors after obtaining written informed consent; our protocol (review number 17708E) was approved by the Office of Research Ethics at Western University.

Primary GDTc

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were recovered using density gradient separation (Ficoll-Paque, GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and plated at 1 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI complete medium containing 1 μg/ml Concanavalin A (Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON). Complete medium: RPMI 1640 with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1 × MEM NEAA, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate (all Gibco/Invitrogen, Burlington, ON). In addition, 10 ng/ml each recombinant human IL-2 (rIL-2, Proleukin, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Canada) and IL-4 (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON) were added. Cell enumeration and viability were assessed by use of a hemocytometer and Trypan blue exclusion. Every 3–4 days, cells were counted and densities adjusted to 1 × 106 cells/ml by addition of fresh medium and cytokines (for each 1 ml fresh medium, 1 μl each IL-2 and IL-4 were added). Conditioned medium was not removed. Cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C with 5 % CO2. Within 1 week, cultures consisted of a mixture of ABTc and GDTc.

Cytokine experiments GDTc that had been in cytokine-containing media were plated into 24-well plates (BD Falcon) at 1 × 106 cells/ml in complete medium without cytokines or 10 ng/ml fresh IL-2 and IL-4 were added. After 72 h, cells were counted and viability assessed via Trypan blue exclusion. Gamma delta T-cell antigen receptor and CD69 expression were determined via flow cytometry.

Thawing GDTc 10–30 million frozen PBMCs were thawed into complete RPMI medium (described above) containing 1μg/ml Concanavalin A. Culture media color was monitored, and cells were counted and fed as required. Aliquots were removed for staining with fluorophore-conjugated antibodies and flow cytometry on days 0, 7 and 14.

Alpha beta T-cell depletion

Mixed ABTc and GDTc cultures were harvested, counted, resuspended in MACS Buffer (PBS containing 0.5 % BSA and 2 mM EDTA) and incubated at 4 °C with PE-conjugated anti-human αβ T-cell antigen receptor antibodies (10 μl/107 cells, BioLegend), washed and then incubated for 15 min at 4 °C with anti-PE microbeads (10–20 μl/107 cells, Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Following cell labeling, cells were run through a 50-μm Cell Trics filter (Partec, Görlitz, Germany) onto an LD depletion column (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn CA) and washed twice as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells in the flow-through were then enumerated and plated in RPMI complete medium (as above) and cultured at 37 °C with 5 % CO2.

Cell Lines PC-3M cells were obtained from the National Cancer Institute Biorepository (Frederick, MD, USA) and cultured in RPMI 1640 plus 10 % FBS. Cells in log phase were harvested by trypsinization and then labeled with Calcein AM as detailed below. U87 cells were kindly provided by Gelareh Zadeh. The Ph+ myeloid leukemia cell line, EM-2, was derived from a patient with CML relapsing with a Ph+ myeloid blast crisis after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation [66].

Flow cytometry Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) was performed on a FACS Calibur (Becton–Dickinson, Mississauga, ON) or LSRII (Becton–Dickinson, Mississauga, ON), calibrated with CaliBRITE beads (Becton Dickenson, Mississauga, ON). LSRII specifications The sorter was equipped with a 50 mW Coherent Cube 402-nm violet diode laser and a 20 mW Coherent Sapphire solid-state 488-nm blue laser to detect FITC (530/30 bandpass (bp) and 505 longpass (lp) filters) and PerCP (685/35 bp, 675 lp); a 50 mW Coherent Compass 561-nm solid-state yellow–green laser for PE (582/15 bp) and PE-Cy7 (780/60 bp and 755 lp); and a 40 mW Coherent Cube 640-nm red diode laser, used to detect APC (670/30 bp), Alexa Fluor 700 (730/45 bp, 710 lp) and APCCy7 (780/60 bp, 755 lp). Live cells were gated based on forward and side-scatter properties. Fluorescence gating was based on negative controls and fluorescence minus one (FMO) controls where necessary. Analysis was performed using FlowJo© software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA, versions 8.8.6 and 6.4.7). On the basis of CD45RA and CD27 markers, GDTc were classified as naïve (CD27+CD45RA+),central memory (CM, CD27+CD45RA−), effector memory (EM, CD27−CD45RA−) and RA+ effector memory (EMRA, CD27-CD45RA+).

Antibodies The following anti-human antibodies were diluted in FACS buffer (PBS+ 1 % FBS+ 2 mM EDTA) as indicated and used for GDTc immunophenotyping: anti-CD3 Alexa 700 (Clone UCHT1, 1:100, BD Biosciences), anti-CD27 APC (Clone M-T271, 1:100, BD Biosciences), anti-CD45RA FITC (Clone H1 100, 1:10, PharMingen), anti-NKG2D APC (Clone 149810, 1:50, BD Biosciences), anti-TCRαβPE (Clone IP26, 1:20, BioLegend), anti-TCRγδPE (Clone B1, 1:10, BioLegend), anti-TCRγδAPC (Clone B1.1, 1:5, BD Biosciences), anti-Vdelta1FITC (Clone TS8.2, 1:20, Thermo Scientific Pierce) and anti-Vdelta2PerCP (Clone B6, 1:100, BioLegend). Activation was assessed via staining with antihuman CD69 Alexa Fluor 700 (Clone FN50, 1:20, BD Biosciences). For blocking, 1 μg/well of the following antibodies was used: mouse IgG (Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON), anti-NKG2D (Clone 1D11, BioLegend), anti-TCRγδ (Clone Immu 510, Meridian Life Science, Saco, ME, USA), anti-TCRγδAPC (Clone B1.1, BD Biosciences), anti-Vδ1 (Clone TS8.2, Thermo Scientific Pierce), anti-Vdelta2 (Clone B6, BioLegend) and anti-CD18 (TS1/18, BioLegend). Blocking was performed at 37 °C for the times indicated.

Calcein AM cytotoxicity assay

Calcein AM cytotoxicity assays were performed as described [46]. Data are presented as mean % lysis of triplicate samples (±SD). In brief, target cells were plated out in fresh medium one day prior to the cytotoxicity assay. After harvesting, cells were washed twice in media, counted and then adjusted to a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml in media in a 15-ml tube. Cells were stained with 20 μM Calcein AM (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON) as follows. Cells were mixed with 8 μl stock solution/ml cell suspension and then incubated 30 min at 37 °C with periodic inversion. 6 ml complete medium was added, cells were centrifuged, re-suspended at 3–4 × 105 cells/ml in medium and plated in triplicate in 96-well round-bottom plates. Effector cells were added at the appropriate densities to achieve the indicated effector:target ratios. Maximum release wells were prepared by addition of Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON) to 0.5 % (v/v). Co-cultures were incubated 4 h at 37 °C with 5 % CO2 and then centrifuged, and 75 μL supernatant was transferred to a 96-well flat-bottom plate. Fluorescence at 485/548 nm was detected on a Fluoroskan Ascent FL fluorimeter running Ascent software version 2.6 (Thermo Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland). Percent lysis was calculated by the following formula: [(test-spontaneous release)/(maximum-spontaneous release)] × 100 %. Standard deviations were calculated and statistical analysis performed with Excel software.

Cell labeling

GDTc were plated overnight in serum-free medium at 1 × 106 cells/ml in 24-well plates. 800 μl media was removed, and 100 μg/ml Feraheme (Ferumoxytol, AMAG Pharmaceuticals) and 6 μg/ml protamine sulfate were added and cells incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. 800 μl media per well were added back and cells incubated for 18–24 h at 37 °C on a Super Magnetic Plate (OZ Biosciences, Marseilles, France). After harvesting, cells were counted, viability was assessed using Trypan blue, and aliquots were subject to cytospin and Perls’ Prussian blue (PPB) staining, fixation for electron microscopy or preparation of agarose phantoms.

Serum experiment

The following were used at 10 % (v/v): FBS (Gibco/Invitrogen, Burlington, ON); human AB serum (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA); ES cell knockout serum replacement (Gibco/Invitrogen, Burlington, ON). For isolation of autologous serum, blood was collected in red top blood collection tubes (containing no anticoagulant, BD Vacutainer, BD Franklin Lakes, NJ) and allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 min, after which the sample was centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min and serum removed.

Histology

Perls’ Prussian blue (PPB) staining

To detect iron, GDTc were stained with PPB. Typically, 2.5–5 × 105 cells were suspended in 300μL PBS and centrifuged onto slides at 500 rpm for 5 min with a ThermoFisher Cytospin 4. Cells were fixed for 5 min in methanol acetic acid solution (3:1) then stained for 30 min in 2 % potassium ferrocyanide in 2 % hydrochloric acid. After rinsing with dH2O, cells were counterstained for 5 min with 0.5 % eosin solution (Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON) to identify the cytoplasm. After further rinsing in dH2O, cells were sequentially dehydrated by dipping twice in each of a series of alcohol solutions (75, 90 and 100 %). Slides were finally incubated for 1 min in xylenes before cover-slipping. Images were obtained with a Zeiss AXIO Imager A1 microscope and QImaging RETIGA EXi camera at 40× and 100× magnification.

Electron microscopy

After overnight fixation in 2.5 % glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (SCB) at 4 °C, cells were washed in 0.1 M SCB and then post-fixed for 1 h in 1 % osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M SCB. After washing in SCB, cells were enrobed in noble agar. After washing with distilled water, cells were stained for 2 h in 2 % uranyl acetate, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanols and then cleared in propylene oxide followed by embedding in Epon 812 resin. 60–90-nm sections were mounted on 300 mesh formvar–carbon-coated copper grids, then stained first with 2 % uranyl acetate and then with lead citrate. Sections were examined on a Philips 410 transmission electron microscope.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Preparation of Phantoms 9 × 105 cells were fixed with 4 % PFA for 20 min at room temperature and then mixed with 1 % agarose in PBS and placed in 5-mm-diameter NMR glass tubes.

Image Acquisition MRI was performed on a 3T whole-body clinical MR scanner using a custom-built gradient coil (inner diameter = 12 cm; maximum gradient strength = 600mT/m; peak slew rate = 2,000T/m/s). Cell samples were imaged using a custom-built solenoidal radiofrequency coil (inner diameter = 6 mm). The 3D balanced steady state free precession (bSSFP) sequence was performed with the following parameters: repetition time/echo time = 26/13 Ms; flip angle = 35°; receiver bandwidth = ±21 kHz; resolution = 100 × 100 × 200 μm; phase cycles = 4; averages = 2; acquisition time = 34 min 42 s. For analysis, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for each phantom was measured.

Statistics Means, standard deviations, standard error and P-values (Student’s t tests) were calculated using Microsoft®Excel® for Mac version 11.6.6.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend a heartfelt thank you to our healthy donors, without whom this work would not have been possible. Thanks to Catherine McFadden for advice on cell labeling as well as Gelareh Zadeh and Kelly Burrell for the U87 glioblastoma cells. Additionally, we thank Martin Rutter at Miltenyi Biotec for timely assistance and the Haeryfar laboratory at Western University for lending us the MACS Midi magnet for our depletions. We thank Judith Sholdice for EM imaging. A.K. holds the Gloria and Seymour Epstein Chair in Cell Therapy and Transplantation at University Health Network and the University of Toronto. P.F. was funded by the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, One Millimeter Cancer Challenge Program.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hayday AC. [gamma][delta] cells: a right time and a right place for a conserved third way of protection. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:975–1026. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kabelitz D, Wesch D, He W. Perspectives of gammadelta T cells in tumor immunology. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamb LS, Jr, Lopez RD. gammadelta T cells: a new frontier for immunotherapy? Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ensslin AS, Formby B. Comparison of cytolytic and proliferative activities of human gamma delta and alpha beta T cells from peripheral blood against various human tumor cell lines. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:1564–1569. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.21.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng BJ, Chan KW, Im S, Chua D, Sham JS, et al. Anti-tumor effects of human peripheral gammadelta T cells in a mouse tumor model. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:421–425. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viey E, Lucas C, Romagne F, Escudier B, Chouaib S, et al. Chemokine receptors expression and migration potential of tumor-infiltrating and peripheral-expanded Vgamma9Vdelta2 T cells from renal cell carcinoma patients. J Immunother. 2008;31:313–323. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181609988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knight A, Mackinnon S, Lowdell MW. Human Vdelta1 gamma-delta T cells exert potent specific cytotoxicity against primary multiple myeloma cells. Cytotherapy. 2012;14:1110–1118. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2012.700766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright A, Lee JE, Link MP, Smith SD, Carroll W, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for self tumor immunoglobulin express T cell receptor delta chain. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1557–1564. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.5.1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedman MS, D’Souza S, Antel JP. gamma delta T-cell-human glial cell interactions. I. In vitro induction of gammadelta T-cell expansion by human glial cells. J Neuroimmunol. 1997;74:135–142. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5728(96)00217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vollenweider I, Vrbka E, Fierz W, Groscurth P. Heterogeneous binding and killing behaviour of human gamma/delta-TCR+ lymphokine-activated killer cells against K562 and Daudi cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1993;36:331–336. doi: 10.1007/BF01741172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kunzmann V, Bauer E, Feurle J, Weissinger F, Tony HP, et al. Stimulation of gammadelta T cells by aminobisphosphonates and induction of antiplasma cell activity in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2000;96:384–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegers GM, Dhamko H, Wang XH, Mathieson AM, Kosaka Y, et al. Human Vdelta1 gammadelta T cells expanded from peripheral blood exhibit specific cytotoxicity against B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia-derived cells. Cytotherapy. 2011;13:753–764. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2011.553595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siegers GM, Felizardo TC, Mathieson AM, Kosaka Y, Wang XH, et al. Anti-leukemia activity of in vitro-expanded human gamma delta T cells in a xenogeneic Ph+ leukemia model. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16700. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gioia C, Agrati C, Casetti R, Cairo C, Borsellino G, et al. Lack of CD27-CD45RA-V gamma 9V delta 2+ T cell effectors in immunocompromised hosts and during active pulmonary tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2002;168:1484–1489. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dieli F, Poccia F, Lipp M, Sireci G, Caccamo N, et al. Differentiation of effector/memory Vdelta2 T cells and migratory routes in lymph nodes or inflammatory sites. J Exp Med. 2003;198:391–397. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Z, Guo BL, Gehrs BC, Nan L, Lopez RD. Ex vivo expanded human Vgamma9Vdelta2+ gammadelta-T cells mediate innate antitumor activity against human prostate cancer cells in vitro. J Urol. 2005;173:1552–1556. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154355.45816.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dieli F, Vermijlen D, Fulfaro F, Caccamo N, Meraviglia S, et al. Targeting human {gamma}delta} T cells with zoledronate and interleukin-2 for immunotherapy of hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7450–7457. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamaguchi T, Fujimiya Y, Suzuki Y, Katakura R, Ebina T. A simple method for the propagation and purification of gamma delta T cells from the peripheral blood of glioblastoma patients using solid-phase anti-CD3 antibody and soluble IL-2. J Immunol Methods. 1997;205:19–28. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(97)00062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamaguchi T, Suzuki Y, Katakura R, Ebina T, Yokoyama J, et al. Interleukin-15 effectively potentiates the in vitro tumor-specific activity and proliferation of peripheral blood gammadeltaT cells isolated from glioblastoma patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1998;47:97–103. doi: 10.1007/s002620050509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujimiya Y, Suzuki Y, Katakura R, Miyagi T, Yamaguchi T, et al. In vitro interleukin 12 activation of peripheral blood CD3(+)CD56(+) and CD3(+)CD56(-) gammadelta T cells from glioblastoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:633–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamb LS., Jr Gammadelta T cells as immune effectors against high-grade gliomas. Immunol Res. 2009;45:85–95. doi: 10.1007/s12026-009-8114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi H, Tanaka Y, Yagi J, Osaka Y, Nakazawa H, et al. Safety profile and anti-tumor effects of adoptive immunotherapy using gamma-delta T cells against advanced renal cell carcinoma: a pilot study. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:469–476. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0199-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi H, Tanaka Y, Shimmura H, Minato N, Tanabe K. Complete remission of lung metastasis following adoptive immunotherapy using activated autologous gammadelta T-cells in a patient with renal cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:575–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakajima J, Murakawa T, Fukami T, Goto S, Kaneko T, et al. A phase I study of adoptive immunotherapy for recurrent non-small-cell lung cancer patients with autologous gammadelta T cells. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37:1191–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennouna J, Bompas E, Neidhardt EM, Rolland F, Philip I, et al. Phase-I study of Innacell gammadelta, an autologous cell-therapy product highly enriched in gamma9delta2 T lymphocytes, in combination with IL-2, in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57:1599–1609. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0491-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicol AJ, Tokuyama H, Mattarollo SR, Hagi T, Suzuki K, et al. Clinical evaluation of autologous gamma delta T cell-based immunotherapy for metastatic solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:778–786. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mallett CL, McFadden C, Chen Y, Foster PJ. Migration of iron-labeled KHYG-1 natural killer cells to subcutaneous tumors in nude mice, as detected by magnetic resonance imaging. Cytotherapy. 2012;14:743–751. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2012.667874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Chickera S, Willert C, Mallet C, Foley R, Foster P, et al. Cellular MRI as a suitable, sensitive non-invasive modality for correlating in vivo migratory efficiencies of different dendritic cell populations with subsequent immunological outcomes. Int Immunol. 2012;24:29–41. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxr095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang X, de Chickera SN, Willert C, Economopoulos V, Noad J, et al. Cellular magnetic resonance imaging of monocyte-derived dendritic cell migration from healthy donors and cancer patients as assessed in a scid mouse model. Cytotherapy. 2011;13:1234–1248. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2011.605349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonzalez-Lara LE, Xu X, Hofstetrova K, Pniak A, Chen Y et al (2010) The use of cellular magnetic resonance imaging to track the fate of iron-labeled multipotent stromal cells after direct transplantation in a mouse model of spinal cord injury. Mol Imaging Biol [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Jirak D, Kriz J, Strzelecki M, Yang J, Hasilo C, et al. Monitoring the survival of islet transplants by MRI using a novel technique for their automated detection and quantification. MAGMA. 2009;22:257–265. doi: 10.1007/s10334-009-0172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heyn C, Ronald JA, Mackenzie LT, MacDonald IC, Chambers AF, et al. In vivo magnetic resonance imaging of single cells in mouse brain with optical validation. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:23–29. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oweida AJ, Dunn EA, Karlik SJ, Dekaban GA, Foster PJ. Iron-oxide labeling of hematogenous macrophages in a model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and the contribution to signal loss in fast imaging employing steady state acquisition (FIESTA) images. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26:144–151. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernas LM, Foster PJ, Rutt BK. Imaging iron-loaded mouse glioma tumors with bSSFP at 3 T. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64:23–31. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foster PJ, Dunn EA, Karl KE, Snir JA, Nycz CM, et al. Cellular magnetic resonance imaging: in vivo imaging of melanoma cells in lymph nodes of mice. Neoplasia. 2008;10:207–216. doi: 10.1593/neo.07937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perera M, Ribot EJ, Percy DB, McFadden C, Simedrea C, et al. In vivo magnetic resonance imaging for investigating the development and distribution of experimental brain metastases due to breast cancer. Trans Oncol. 2012;5:217–225. doi: 10.1593/tlo.12109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heyn C, Ronald JA, Ramadan SS, Snir JA, Barry AM, et al. In vivo MRI of cancer cell fate at the single-cell level in a mouse model of breast cancer metastasis to the brain. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:1001–1010. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ribot EJ, Foster PJ (2012) In vivo MRI discrimination between live and lysed iron-labeled cells using balanced steady state free precession. Eur Radiol (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Garden OA, Reynolds PR, Yates J, Larkman DJ, Marelli-Berg FM, et al. A rapid method for labelling CD4+ T cells with ultrasmall paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for magnetic resonance imaging that preserves proliferative, regulatory and migratory behaviour in vitro. J Immunol Methods. 2006;314:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beer AJ, Holzapfel K, Neudorfer J, Piontek G, Settles M, et al. Visualization of antigen-specific human cytotoxic T lymphocytes labeled with superparamagnetic iron-oxide particles. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:1087–1095. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-0874-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iida H, Takayanagi K, Nakanishi T, Kume A, Muramatsu K, et al. Preparation of human immune effector T cells containing iron-oxide nanoparticles. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008;101:1123–1128. doi: 10.1002/bit.21992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Janic B, Rad AM, Jordan EK, Iskander AS, Ali MM, et al. Optimization and validation of FePro cell labeling method. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arbab AS, Janic B, Jafari-Khouzani K, Iskander AS, Kumar S, et al. Differentiation of glioma and radiation injury in rats using in vitro produce magnetically labeled cytotoxic T-cells and MRI. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9365. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lewin M, Carlesso N, Tung CH, Tang XW, Cory D, et al. Tat peptide-derivatized magnetic nanoparticles allow in vivo tracking and recovery of progenitor cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:410–414. doi: 10.1038/74464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu L, Ye Q, Wu Y, Hsieh WY, Chen CL et al (2012) Tracking T-cells in vivo with a new nano-sized MRI contrast agent. Nanomedicine [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Neri S, Mariani E, Meneghetti A, Cattini L, Facchini A. Calcein-acetyoxymethyl cytotoxicity assay: standardization of a method allowing additional analyses on recovered effector cells and supernatants. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8:1131–1135. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.6.1131-1135.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mallett CL, Foster PJ. Optimization of the balanced steady state free precession (bSSFP) pulse sequence for magnetic resonance imaging of the mouse prostate at 3T. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e18361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lamb LS, Jr, Musk P, Ye Z, van Rhee F, Geier SS, et al. Human gammadelta(+) T lymphocytes have in vitro graft vs leukemia activity in the absence of an allogeneic response. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;27:601–606. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Halary F, Pitard V, Dlubek D, Krzysiek R, de la Salle H, et al. Shared reactivity of V{delta}2(neg) {gamma}{delta} T cells against cytomegalovirus-infected cells and tumor intestinal epithelial cells. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1567–1578. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schilbach K, Frommer K, Meier S, Handgretinger R, Eyrich M. Immune response of human propagated gammadelta-T-cells to neuroblastoma recommend the Vdelta1+ subset for gammadelta-T-cell-based immunotherapy. J Immunother. 2008;31:896–905. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31818955ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Couzi L, Pitard V, Sicard X, Garrigue I, Hawchar O, et al. Antibody-dependent anti-cytomegalovirus activity of human gammadelta T cells expressing CD16 (FcgammaRIIIa) Blood. 2012;119:1418–1427. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-363655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Knight A, Madrigal AJ, Grace S, Sivakumaran J, Kottaridis P, et al. The role of Vdelta2-negative gammadelta T cells during cytomegalovirus reactivation in recipients of allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2010;116:2164–2172. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-255166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dokouhaki P, Han M, Joe B, Li M, Johnston MR, et al. Adoptive immunotherapy of cancer using ex vivo expanded human gammadelta T cells: a new approach. Cancer Lett. 2010;297:126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Correia DV, Fogli M, Hudspeth K, da Silva MG, Mavilio D, et al. Differentiation of human peripheral blood Vdelta1+ T cells expressing the natural cytotoxicity receptor NKp30 for recognition of lymphoid leukemia cells. Blood. 2011;118:992–1001. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-339135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poggi A, Zocchi MR, Carosio R, Ferrero E, Angelini DF, et al. Transendothelial migratory pathways of V delta 1+ TCR gamma delta+ and V delta 2+ TCR gamma delta+ T lymphocytes from healthy donors and multiple sclerosis patients: involvement of phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase and calcium calmodulin-dependent kinase II. J Immunol. 2002;168:6071–6077. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Janssen O, Wesselborg S, Heckl-Ostreicher B, Pechhold K, Bender A, et al. T cell receptor/CD3-signaling induces death by apoptosis in human T cell receptor gamma delta+ T cells. J Immunol. 1991;146:35–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lopez RD, Xu S, Guo B, Negrin RS, Waller EK. CD2-mediated IL-12-dependent signals render human gamma delta-T cells resistant to mitogen-induced apoptosis, permitting the large-scale ex vivo expansion of functionally distinct lymphocytes: implications for the development of adoptive immunotherapy strategies. Blood. 2000;96:3827–3837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Viey E, Laplace C, Escudier B. Peripheral gammadelta T-lymphocytes as an innovative tool in immunotherapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2005;5:973–986. doi: 10.1586/14737140.5.6.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kondo M, Sakuta K, Noguchi A, Ariyoshi N, Sato K, et al. Zoledronate facilitates large-scale ex vivo expansion of functional gammadelta T cells from cancer patients for use in adoptive immunotherapy. Cytotherapy. 2008;10:842–856. doi: 10.1080/14653240802419328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilhelm M, Kunzmann V, Eckstein S, Reimer P, Weissinger F, et al. Gammadelta T cells for immune therapy of patients with lymphoid malignancies. Blood. 2003;102:200–206. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pennington DJ, Silva-Santos B, Shires J, Theodoridis E, Pollitt C, et al. The inter-relatedness and interdependence of mouse T cell receptor gammadelta+ and alphabeta+ cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:991–998. doi: 10.1038/ni979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Caccamo N, Meraviglia S, Ferlazzo V, Angelini D, Borsellino G, et al. Differential requirements for antigen or homeostatic cytokines for proliferation and differentiation of human Vgamma9Vdelta2 naive, memory and effector T cell subsets. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1764–1772. doi: 10.1002/eji.200525983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Groh V, Rhinehart R, Secrist H, Bauer S, Grabstein KH, et al. Broad tumor-associated expression and recognition by tumor-derived gamma delta T cells of MICA and MICB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6879–6884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Novotna B, Jendelova P, Kapcalova M, Rossner P, Jr, Turnovcova K, et al. Oxidative damage to biological macromolecules in human bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells labeled with various types of iron oxide nanoparticles. Toxicol Lett. 2012;210:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brekelmans P, van Soest P, Voerman J, Platenburg PP, Leenen PJ, et al. Transferrin receptor expression as a marker of immature cycling thymocytes in the mouse. Cell Immunol. 1994;159:331–339. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Keating A, Bernstein ID, Papayannopoulou T, Raskind W, Singer JW (1983) EM-2 and EM-3: two new Ph’+ myeloid cell lines. In: PA GDM (ed) Symposia on molecular and cellular biology, new series; UCLA. Alan R. Liss, New York, pp 513–520

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.