Abstract

Walleye dermal sarcoma (WDS) and walleye epidermal hyperplasia (WEH) are skin diseases of walleye fish that appear and regress on a seasonal basis. We report here that the complex retroviruses etiologically associated with WDS (WDS virus [WDSV]) and WEH (WEH viruses 1 and 2 [WEHV1 and WEHV2, respectively]) encode D-type cyclin homologs. The retroviral cyclins (rv-cyclins) are distantly related to one another and to known cyclins and are not closely related to any walleye cellular gene based on low-stringency Southern blotting. Since aberrant expression of D-type cyclins occurs in many human tumors, we suggest that expression of the rv-cyclins may contribute to the development of WDS or WEH. In support of this hypothesis, we show that rv-cyclin transcripts are made in developing WDS and WEH and that the rv-cyclin of WDSV induces cell cycle progression in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). WEHV1, WEHV2, and WDSV are the first examples of retroviruses that encode cyclin homologs. WEH and WDS and their associated retroviruses represent a novel paradigm of retroviral tumor induction and, importantly, tumor regression.

Studies of tumor induction by avian and murine simple retroviruses have led to key advances in the understanding of cell proliferation and oncogenesis (reviewed in references 47 and 49). Tumor induction by these oncoviruses occurs by the activation of proto-oncogenes resulting from proviral insertion (non-acutely transforming viruses) and by the transduction of oncogenes (acutely transforming viruses). The discovery that viral oncogenes were derived from cellular proto-oncogenes has provided important clues about the roles of proto-oncogenes in normal cell proliferation and in tumor induction (56). Several classes of oncogenes have been identified by retroviral transduction and/or proviral insertion, including those encoding nonreceptor and receptor protein tyrosine kinases (src and erbB, respectively), G proteins (ras), serine-threonine kinases (raf), growth factors (sis), and transcription factors (myc) (49). In addition, numerous genes that encode proteins with yet unknown function have been identified in various tumors resulting from proviral insertional mutagenesis (49).

Tumor induction by complex retroviruses, i.e., members of the human T-cell leukemia virus (HTLV)-bovine leukemia virus (BLV) group, is less well understood. These viruses lack identifiable cell-derived oncogenes and are not known to activate cellular proto-oncogenes by proviral insertion (49). HTLV and BLV contain two accessory genes at the 3′ end of their genomes, tax and rex, that control viral gene expression (12). Tax also activates the expression of many cellular genes, including those that stimulate T-cell growth (e.g., interleukin 2), and considerable attention has focused on its role in cell transformation (50, 63). Tax of HTLV-1 has been shown to induce mesenchymal tumors in transgenic mice (43) and is essential for transformation of human T lymphocytes in cell culture (51). Although Tax is likely to be important for transformation, in vitro studies and analysis of transgenic mice show that Tax alone is not sufficient for maintenance of the transformed phenotype (49). Rather, Tax may stimulate abnormal replication early in the disease process, thereby leading to the transformation of infected T cells.

Retroviruses have also been implicated in several neoplastic diseases of lower vertebrate animals, such as fish, amphibians, and reptiles (45). The best characterized of these viruses are walleye dermal sarcoma virus (WDSV) and, more recently, walleye epidermal hyperplasia virus types 1 and 2 (WEHV1 and WEHV2, respectively) (25, 32, 38, 60). These related, large complex retroviruses are etiologically associated with neoplastic and hyperproliferative skin diseases of walleye fish, walleye dermal sarcoma (WDS) and walleye epidermal hyperplasia (WEH), respectively (7, 10, 38, 39). Most interestingly, these diseases are among several neoplastic and proliferative diseases of poikilotherms that are seasonal in nature, presenting an opportunity to study both tumorigenesis and tumor regression (1, 8, 45). WDS and WEH have been observed on 10 to 30% of walleyes in a given year from late autumn until early spring, when they completely regress (8, 9). These diseases have not been observed to progress to invasive or metastatic tumors on adult feral fish, but injection of cell-free filtrates of WDS into walleye fingerlings less than 12 weeks of age can cause invasive tumors in 12 to 16 weeks, suggesting that WDSV has oncogenic potential (19, 40).

The mechanisms by which WDSV and WEHV1 and WEHV2 induce WDS and WEH are not known. These viruses contain three open reading frames in addition to gag, pol, and env (25). orfA and orfB are located between env and the 3′ long terminal repeat (LTR), and orfC is located between the 5′ LTR and gag. We report here that the orfA genes of these viruses encode cyclin D homologs. Cellular cyclins associate with and activate cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks) to promote cell cycle progression (54, 55). D-type cyclin-Cdk complexes regulate the cell-cycle G1-to-S transition and have been proposed to induce cell proliferation by phosphorylating and thereby inactivating the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein (Rb) (18, 20, 30). Aberrant expression of human cyclin D1 has been demonstrated in various human tumors, including parathyroid adenomas (41), breast and squamous cell carcinomas (31), and esophageal carcinomas (28). Cyclin genes have not been previously identified as oncogenes in acutely transforming viruses, but integration of murine leukemia virus (MLV) into the cyclin D1 (Fis1) and cyclin D2 (Vin1) loci results in T-cell lymphomas (42, 59). WDSV, WEHV1, and WEHV2 are the first examples of retroviruses to encode cyclin homologs, and the possible roles of retroviral cyclins (rv-cyclins) in tumor induction and viral replication are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA sequencing, DNA analysis, and amino acid alignments.

Double-stranded DNA sequencing was done with Sequenase 2.0 (Pharmacia). Database searches were done with the BlastX algorithm. Amino acid alignments were done with Megalign (DNAstar) and Geneworks (IntelliGenetics, Inc.). The amino acid substitutions allowed for determination of sequence similarities are as follows: F=Y=W, M=L=V=I, S=A, S=T, D=E, and R=K=H.

PCR amplification of a walleye kinase gene.

The primers 5′-TTACACTCTGTACTGTCACTC-3′ and 5′-ATTACCTTCTGATGGATGCA-3′ were used to amplify a 530-bp segment of a walleye kinase gene that has sequence similarity to the human A6 kinase gene (5). One hundred picograms of lambda DNA containing the walleye kinase gene adjacent to a WEHV2 provirus was amplified with Taq polymerase (Gibco-BRL). The sample was denatured at 96°C for 5 min and amplified as follows: 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min for 35 cycles, and the PCR fragment was gel purified with the Qiaex II gel extraction kit (Qiagen).

Southern and Northern blotting.

Southern blotting and Northern blotting were done by standard methods (53). Probes were labeled with 32P by a random-primed DNA-labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim). Approximately 40 μg of DNA isolated from dermal sarcomas or epidermal hyperplasias or 80 μg of walleye sperm DNA was digested with Bsu36I (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s directions and were equally divided for Southern hybridization with orfA probes or the walleye A6 kinase probe. Hybridization was done in the presence of 50% formamide at 37°C. The blots were washed under low-stringency conditions (2× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate] at 37°C) and exposed to XAR-5 film (Kodak) for 5 to 10 days. Poly(A)+-enriched RNA was isolated with a Promega poly(A)+ Tract IV kit. Northern blotting was done with approximately 1 μg of poly(A)+-enriched RNA from fall lesions and approximately 10 μg of total RNA from spring lesions. Blots containing RNA isolated from the fall and spring were exposed to film for 4 days and 24 h, respectively.

Cloning of a walleye D-type cyclin.

The walleye cell lines WF2 and WL12 and walleye primary cell cultures were grown to 80% confluence in minimal essential medium with Hanks salts, containing 25 mM HEPES, 2 mM glutamine, antibiotics, and 10% fetal bovine serum at 15°C in T25 flasks. The cells were starved for 48 h (as described above without serum). Serum was added, the cells were grown for 24 to 48 h, and total RNA was isolated with RNAzol B (Tel-Test, Inc.). The RNA samples were treated with RNase-free DNase, and reverse transcription-PCR was done with a modified 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) protocol (Gibco-BRL). Briefly, cDNA was prepared with 1 μg of RNA, the oligo(dT) adapter primer, and 4 U of MLV-reverse transcriptase (New England Biolabs) according to manufacturer’s directions. Two microliters of the cDNA reaction mixture was amplified by PCR with a degenerate 5′ primer derived from the amino acid sequence WMLEVCEEQ (5′-ctcggatccTGGATGYTNGARGTNTGYGARGARCA-3′) found in cellular D-type cyclins and the universal anchor primer (Gibco-BRL) (lowercase letters represent additional bases that include restriction sites). The sample was denatured at 96°C for 5 min and amplified as follows: 94°C for 30 s, 44 to 37°C (two cycles in 1° intervals) for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s, followed by 26 cycles of amplification at 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. The PCR product was diluted 1:20, and 1 μl was amplified with the same 5′ primer and a nested degenerate 3′ primer derived from the amino acid sequence CQEQIE (5′-ctcactagtYTCDATYTGYTCYTGRCA-3′, where D = A, T, or G) also found in cellular D-type cyclins. The second round of PCR was done like the first round, except that the annealing steps ranged from 54 to 47°C in 1° intervals. The PCR products were digested with BamHI and SpeI and cloned into pBluescript SKII− (Stratagene). Twenty recombinant plasmids, identified by random screening or by low-stringency colony hybridization with a PRAD1 probe, were analyzed by DNA sequencing (Sequenase kit 2.0; Pharmacia).

Yeast complementation assay.

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain BY613 (cln1Δ cln2Δ cln3Δ his2 trp1 leu2 ura3 pGALCLN3-URA3) and the plasmid pMET-TRP1, containing a polylinker downstream of the yeast MET3 promoter region (constructed by Michael Donoviel), were provided by Brenda Andrews. All manipulations, including transformations, DNA isolations, and 5-fluoroorotic acid counterselection against pGAL::CLN3, were done by standard methods (3, 15, 52).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The GenBank accession numbers for the genes described herein are as follows: WEHV1 cyclin, AF037568; WEHV2 cyclin, AF037569; walleye cyclin D2, AF037570; walleye A6 kinase probe, AF037571.

RESULTS

WDSV, WEHV1, and WEHV2 encode cyclin homologs.

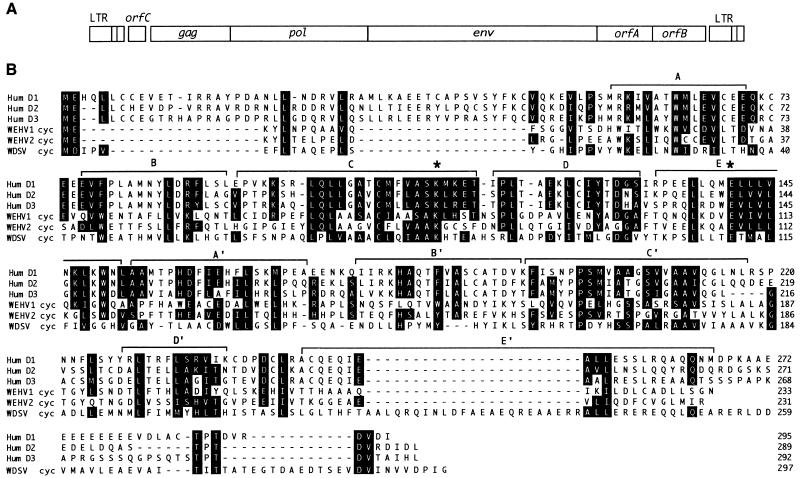

The genomic organization of WDSV, WEHV1, and WEHV2 is shown in Fig. 1A (25). Database searches with the WDSV orfA gene and all three orfB and orfC genes by using the BlastX algorithm did not identify proteins with obvious homology. However, BlastX searches with the WEHV1 and WEHV2 orf-As suggested a distant relationship to D-type cyclins. Visual alignment of the WDSV, WEHV1, and WEHV2 OrfA proteins (297, 233, and 231 amino acid residues, respectively) with an array of cellular cyclins showed that each was a cyclin D homolog, with the WDSV cyclin being the most distantly related (Fig. 1B). The similarity of the retroviral cyclins (rv-cyclins) and D cyclins is limited to the conserved 10-α-helical (A to E′) cyclin box motif (4, 44), with the greatest similarity being in the α-helices C and E, which form the cyclin surface that interacts with cell division kinases (Cdks) (11, 27). Additionally, the lysine and glutamate residues in these regions necessary for Cdk binding are conserved in the rv-cyclins (Fig. 1B) (27). The WEHV1 and WEHV2 rv-cyclins have about 20% amino acid identity with D-type cyclins and about 12% amino acid identity with human cyclin A or E (Table 1). The WEHV1 rv-cyclin has the greatest similarity (35%) to human cyclin D3 and Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV) cyclin (13, 14), whereas the WEHV2 and WDSV rv-cyclins are most similar to human D1 (35 and 29% amino acid similarity, respectively). The WDSV rv-cyclin is the most divergent from cellular cyclins, having 19% amino acid identity to human D1 and about 16% amino acid identity to other D-type cyclins. In general, the rv-cyclins are no more similar to the fish D-type cyclins, zebrafish cyclin D1 and walleye cyclin D2 (see below), than they are to human cyclin D1 (Table 1). The WEHV1 and WEHV2 rv-cyclins are more closely related to one another (37% amino acid identity) than to WDSV rv-cyclin (28 and 21% amino acid identity, respectively).

FIG. 1.

(A) Genomic organization of WDSV, WEHV1, and WEHV2. (B) Amino acid sequence alignment of the rv-cyclins encoded by WDSV, WEHV1, and WEHV2 with human (Hum) cyclins D1, D2, and D3. Identical and similar amino acids are shaded. The 10 α-helices that comprise the cyclin box are bracketed (A to E′), and conserved lysine and glutamate residues in helices C and E are marked by asterisks.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of rv-cyclin amino acid sequences with those of D-type cyclins within the cyclin boxa

| Cyclin type | % Identity/similarityb

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WEHV1 | WEHV2 | WDSV | Human D1 | Zebrafish D1 | Human D2 | Walleye D2 | Human D3 | KSHV | |

| WEHV1 | 100 | 37/48 | 28/47 | 17/32 | 18/31 | 19/33 | 19/30 | 20/35 | 20/35 |

| WEHV2 | 100 | 21/33 | 22/35 | 20/33 | 19/32 | 20/34 | 21/25 | 17/27 | |

| WDSV | 100 | 19/29 | 16/27 | 16/26 | 17/30 | 16/25 | 13/24 | ||

| Human D1 | 100 | 79 | 65 | 65 | 56 | 28/41 | |||

| Zebrafish D1 | 100 | 65 | 69 | 59 | NDc | ||||

| Human D2 | 100 | 85 | 66 | 30/40 | |||||

| Walleye D2 | 100 | 68 | ND | ||||||

| Human D3 | 100 | 30/43 | |||||||

| KSHV | 100 | ||||||||

Alignments were done with Megalign and Geneworks software.

Values represent percent identity/percent similarity when two numbers are shown or percent identity when one number is shown.

ND, not done.

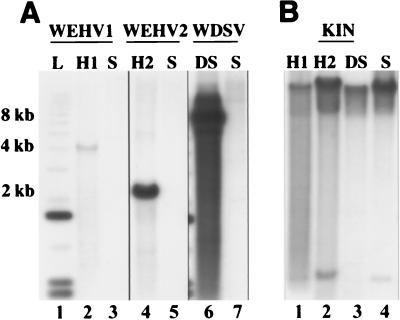

The rv-cyclins are not closely related to walleye cellular cyclins.

Since walleye cellular cyclin sequences were not available for comparison with the rv-cyclins, we used degenerate primer pairs and reverse transcription-PCR to amplify D-type cyclin box sequences from walleye cell lines WF2 and W12 and primary cells. These experiments yielded a cellular cyclin that is most similar to human cyclin D2 having 85% amino acid identity in the cyclin box (Table 1). These data are consistent with earlier studies showing that cyclin subfamily proteins are highly conserved across species; e.g., human cyclin D1 is 79% identical to zebrafish cyclin D1 in the cyclin box. We infer from these data that a putative walleye cyclin D1 protein would be more closely related to human cyclin D1 than to the rv-cyclins. Additionally, while it seems reasonable to speculate that the rv-cyclins are divergent from walleye cellular cyclins based on these sequence comparisons, they could be related to an unknown walleye cyclin homolog. To investigate this possibility, we used WEHV1, WEHV2, and WDSV cyclin gene probes to examine walleye genomic DNA for related genes by low-stringency Southern blotting (Fig. 2). DNA samples isolated from WEH and WDS spring lesions were used as positive controls. The predicted viral restriction fragments encompassing orfA for WEHV1 (4 kb), WEHV2 (2 kb), and WDSV (8 kb) were easily detected in control DNA (Fig. 2A, lanes 2, 4, and 6, respectively). The strength of the hybridization signal suggests that less than one copy of WEHV1 DNA per cell was present in the hyperplasia DNA sample (Fig. 2A, lane 2). The low signal is best explained by the fact that hyperplasia samples, not all of which necessarily harbored WEHV1 (32), were pooled to obtain sufficient DNA for the experiment. By comparison, approximately three to five copies of WEHV2 per cell are present in lesions (Fig. 2A, lane 4). In agreement with earlier reports, there are approximately 50 copies of WDSV DNA per cell in spring tumors (Fig. 2A, lane 6). Importantly, only very weak hybridization was detected with the walleye sperm DNA samples with the WDSV cyclin probe (Fig. 2A, lane 7), and no hybridization was detectable with the WEHV1 and WEHV2 probes (Fig. 2A, lanes 3 and 5). As a control for genomic DNA quality, the walleye kinase gene probe (KIN) hybridizes strongly to its cognate sequence at approximately 12 kb and to a related 500-bp restriction fragment in WEH and WDS DNA samples and walleye sperm DNA (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 to 4). These data demonstrate that unlike the oncogenes transduced by simple retroviruses, the walleye retroviral cyclins are divergent from the cellular sequences from which they are presumably derived.

FIG. 2.

Hybridization of walleye genomic DNA with rv-cyclin probes. (A) Panel of three Southern blots hybridized with a WEHV1, WEHV2, or WDSV rv-cyclin probe, respectively. Lanes: 1, 1-kb DNA ladder (L); 2 and 4, DNA isolated from a pool of hyperplasias containing WEHV1 (H1) and WEHV2 (H2); 6, DNA isolated from a dermal sarcoma (DS); 3, 5, and 7, walleye sperm DNA (S) used a negative control. (B) Southern blot hybridized with walleye cellular kinase probe (KIN). The lane designations are the same as in panel A.

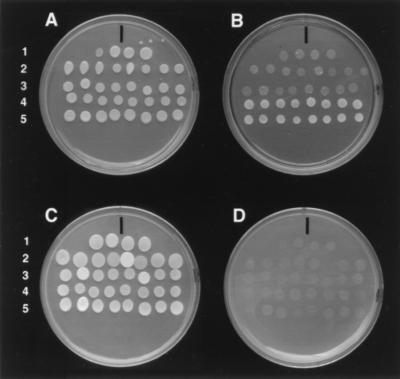

The WDSV rv-cyclin complements cyclin deficiency in yeast.

To assess the ability of rv-cyclins to induce cell cycle progression, we chose to use a standard yeast complementation assay (34). The ability of a putative cyclin to induce cell-cycle progression is indicated by its ability to rescue yeast (S. cerevisiae), which are conditionally deficient in G1 cyclins (Cln genes), from growth arrest. This assay has been used to identify cyclins from diverse organisms, including plants (Arabidopsis), insects (Drosophila), and humans (17, 33, 34). We expressed each rv-cyclin in a yeast strain (BY613) that is deficient for the synthesis of Cln1, -2, and -3 but grows in the presence of galactose because it contains a plasmid that expresses Cln3 from a galactose-inducible promoter (pGAL::CLN3). BY613 does not grow in the presence of glucose, because the galactose promoter is inactive and Cln3 is not produced. We transfected tryptophan-selectable plasmids containing the WDSV, WEHV1, or WEHV2 cyclin gene under the control of the MET2 promoter into BY613 and plated cells on minimal galactose medium lacking tryptophan. Eight individual transformants from each were plated onto minimal glucose medium lacking tryptophan (Fig. 3). All of the transformants grew well on galactose minimal medium (Fig. 3A). Those expressing the WDSV cyclin grew well on the glucose minimal medium (Fig. 3B, rows 4 and 5), whereas expression of the WEHV1 and WEHV2 cyclins did not support growth (Fig. 3B, rows 2 and 3). Immunoprecipitations and Western blots of crude protein extracts showed that the WEHV1 and WEHV2 cyclins were present in transformants (data not shown) but were unable to complement the cyclin deficiency. The experiment was repeated three times at temperatures ranging from 16 to 33°C to test if the interaction of the WEHV1 and WEHV2 rv-cyclins with CDC28p could be sufficiently active at higher or lower temperatures to support yeast growth, with the same result.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of rv-cyclin activity in yeast. (A) BY613 transformants grown on galactose minimal medium. Rows: 1, transformants containing the MET3 promoter plasmid backbone; 2, transformants expressing the WEHV1 rv-cyclin; 3, transformants expressing the WEHV2 rv-cyclin; 4 and 5, transformants containing independently derived plasmids expressing the WDSV rv-cyclin. (B) Glucose minimal medium replica plate of transformants from panel A. (C) Galactose-supplemented rich medium replica plate of transformants from panel A. (D) Glucose-supplemented rich medium replica plate of transformants from panel A.

Importantly, the growth of yeast expressing the WDSV rv-cyclin was linked to the input plasmid; transformants did not grow in the presence of glucose (Fig. 3D, rows 4 and 5) on rich plates that contain sufficient methionine to repress the MET3 promoter directing expression of the WDSV rv-cyclin. To test the ability of the WDSV rv-cyclin to support yeast growth in the absence of pGAL::CLN3, we plated transformants on plates containing FOA and uracil (52). Since FOA kills cells capable of synthesizing uracil, only yeast cells lacking pGAL::CLN3 are able to grow. Yeast clones lacking pGAL::CLN3, but expressing the WDSV rv-cyclin, grew well, confirming that the rv-cyclin will support growth. Subsequently, the WDSV rv-cyclin plasmids were isolated from these segregants and sequenced. The sequences were unaltered (data not shown), showing that the native WDSV OrfA protein can function as a cyclin.

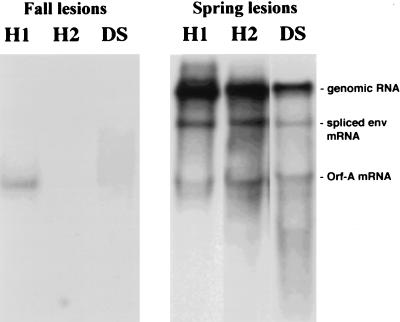

rv-cyclin mRNA is present in fall and spring lesions.

To assess the role of the rv-cyclins in tumor induction and regression, we characterized viral RNA expression patterns in developing (fall) and regressing (spring) lesions. The Northern blot in Fig. 4 showed that the rv-cyclin probes detect genomic RNA (∼13 kb), spliced env mRNA (∼7.5 kb), and spliced orfA mRNA (rv-cyclin mRNA) (∼2.6 to 2.8 kb) in hyperplasias and dermal sarcomas collected in the spring. As with earlier studies of WDSV RNA expression (10, 46), the expression of viral transcripts was low in fall lesions, requiring isolation of poly(A)+ RNA for analysis. While the levels of viral gene expression in fall lesions were low, the most abundant WEHV1 and WDSV mRNAs were consistent with those predicted to encode the rv-cyclins (Fig. 4, lanes 1 and 3; WEHV2 mRNA was not detected in these samples [lane 2]). Upon long film exposure times, genomic WDSV RNA and spliced env mRNA can be observed (data not shown). Additionally, spliced orfB transcripts have been previously observed with LTR probes in fall dermal sarcomas (46), but have not been observed with LTR probes in fall hyperplasias (data not shown). The presence of rv-cyclin transcripts in fall lesions suggests that the rv-cyclin proteins may play an important role in tumor induction. These data emphasize that there is differential expression of viral genes at different stages of disease, i.e., only a relatively low level of the rv-cyclin transcripts (and orfB transcripts for WDSV) is detected in developing fall lesions, whereas abundant levels of many viral transcripts are detected in regressing spring lesions. This phenomenon has been previously reported for WDS (10, 46), but not for WEH.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of rv-cyclin expression. One microgram of poly(A)-enriched RNA from fall lesions (left panel) or 10 μg of total RNA from spring lesions (right panel) was hybridized to cognate rv-cyclin probes. H1, RNA isolated from hyperplasias hybridized to the WEHV1 rv-cyclin probe; H2, RNA from hyperplasias hybridized with the WEHV2 rv-cyclin probe; DS, RNA from dermal sarcomas hybridized with WDSV rv-cyclin probe. The fall blots were exposed to film for 4 days, while the spring blots were exposed to film for 24 h.

DISCUSSION

Sequence analysis of the WEHV1, WEHV2, and WDSV orfAs shows that they encode cyclin D homologs. The homology of the rv-cyclins to D-type cyclins suggests that an ancestral retrovirus acquired a cellular cyclin gene, possibly in a process similar to the transduction of oncogenes by avian and murine simple retroviruses (57), and the virus subsequently evolved into WEHV1, WEHV2, and WDSV. Unlike the oncogenes acquired by the simple oncoviruses, which have substantial homology with their respective proto-oncogenes, the rv-cyclins share only limited homology with known cellular cyclins. WEHV1, WEHV2, and WDSV may represent a new class of oncogenic retroviruses; they are the first examples of retroviruses to encode cyclin homologs and are the only complex retroviruses that encode a protein with homology to a cellular proto-oncogene.

Divergent cyclin D homologs have previously been identified in two oncogenic herpesviruses, the KSHV and herpesvirus saimiri (HVS) (13, 14, 29). These viral cyclins have biochemical properties that differ from those of human D-type cyclins. For example, unlike human cyclin D1-activated Cdk6, HVS and KSHV cyclin-activated Cdk6 phosphorylates histone H1 in addition to Rb in vitro, suggesting that these cyclins alter the substrate preference of Cdk6 (23, 29). In addition, it was recently shown that the KSHV cyclin-Cdk6 complex is resistant to a number of proteins that function to negatively regulate cyclin-Cdk complexes (p16Ink4a, p21Cip1, and p27Kip1) (58). The resistance of the KSHV cyclin-Cdk6 complex to these inhibitors suggests that these viruses may use a novel mechanism for deregulating the cell cycle. Interestingly, the herpesvirus cyclins (and rv-cyclins) lack the canonical Rb binding domain (LXCXE) (18), suggesting that a different domain is used for binding to Rb or a different mechanism is used by these proteins to bind Rb. By analogy with the herpesvirus cyclins, the divergent rv-cyclins may have unique biochemical and functional properties from known cyclins.

Analogous to cellular cyclins, we suggest that the rv-cyclins may promote cell cycle progression by activating Cdks to initiate the protein phosphorylation cascade that culminates in cell division (54, 55). This is supported by our experiments showing that WDSV rv-cyclin rescues yeast deficient in G1/S cyclins from growth arrest. These results indicate that WDSV cyclin can activate the yeast kinase, CDC28p, and therefore has the potential to stimulate the growth of walleye cells. While the WEHV rv-cyclins did not complement the cyclin deficiency in yeast, it has previously been observed that cyclins differ in their ability to complement cyclin deficiency in this experimental system, e.g., human cyclins A, B, C, and E work well in this assay, whereas, cyclin D1 works poorly (34). Therefore, we infer from their similarities to the human cyclin D and WDSV rv-cyclin that the WEHV1 and WEHV2 rv-cyclins may affect cell cycle progression in their homologous system. The hypothesis that the rv-cyclins may play a role in the induction of WDS and WEH is supported by (i) our observation that rv-cyclin transcripts are present in developing lesions, (ii) studies demonstrating that expression of human cyclin D1 from tissue-specific promoters in transgenic mice results in cell hyperproliferation in cognate tissues (48, 61), and (iii) the general observation that cyclin overexpression is associated with many types of human tumors (2).

Since most retroviruses require dividing cells for replication, the induction of cell proliferation by the rv-cyclins may be necessary for viral replication. However, other observations suggest the possibility that the rv-cyclins may have other roles in the viral life cycle. The pattern of a low level of viral gene expression that appears limited to orfA (and orfB in WDSV) mRNA in developing WDS and WEH is reminiscent of complex retrovirus accessory gene expression early after infection of tissue culture cells (16, 46). Similarly, the expression of accessory and structural genes observed in regressing WDS and WEH may be analogous to the pattern of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) gene expression observed in the late stages of cell culture infection (16, 46). While a specific regulatory role for the rv-cyclins in viral gene expression cannot be assigned, it is noteworthy that cyclins and cyclin homologs play important roles in the assembly of transcription complexes. A yeast cyclin-like protein, SRB11, forms a novel complex with a Cdk (SRB10) that is part of the yeast RNA polymerase II holoenzyme (35). Analogously, the Cdk-activating kinase (CAK)-cyclin H complex is a subunit of the basal transcription factor TFIIH in higher eukaryotes (36). There is also precedent for cyclin involvement in regulating viral transcription. A cellular kinase complex has been identified whose activity is modulated by Tat to activate HIV transcription by increasing the elongation properties of RNA polymerase II (24, 37, 64). Recently, Wei et al. (62) identified a novel Cdk9-associated C-type cyclin (cyclin T) as a component of the Tat-associated kinase complex, and they provide evidence to suggest that cyclin T is a TAR RNA-binding cellular cofactor for Tat. This is interesting because the 5′ end of WDSV mRNAs is predicted to fold into a stem-loop that is reminiscent of the TAR stem-loop. Additionally, human cyclin D1, independent of Cdk4, interacts directly with the estrogen receptor or the estrogen-estrogen receptor complex to stimulate transcription of cellular genes, thereby enabling estrogen-independent growth of breast tumor cells that overexpress cyclin D1 (65). The latter finding may be particularly relevant, because the development and regression of WDS and WEH and the changes in walleye retrovirus gene expression occur at different stages of the walleye reproductive cycle.

The walleye tumor model.

It is most likely that walleyes are infected by WEHV1, WEHV2, and/or WDSV when fish congregate in the spring of the year to spawn. Following initial infection, we presume that viral accessory gene protein expression (the rv-cyclins and possibly the OrfB proteins) induces some cells to proliferate abnormally, resulting in visible WDS or WEH by autumn. Lesions grow in size in the cold months, but as spring approaches, the pattern and level of viral gene expression change to include high levels of all viral transcripts, and tumors begin to regress (10, 46). Tumor regression culminates in the spring, when WDS and WEH lesions are shed. These spring lesions contain an abundance of virions, which provide the inoculum to initiate another infectious cycle (9, 10).

In nature, neither WDS nor WEH has been found to develop into invasive or metastatic tumors, suggesting that WDSV, WEHV1, and WEHV2 are only weakly oncogenic. However, the observation that invasive tumors occur in experimentally inoculated walleye fingerlings indicates that WDSV does harbor a potent oncogene, possibly the rv-cyclin. Therefore, we suggest that in nature, tumor regression occurs before events responsible for cellular transformation and metastasis take place. While the mechanism of regression is not known, preliminary investigations of spring tumors showed numerous apoptotic cells in regressing tumors (6). Interestingly, high levels of human cyclin D are observed in tissue culture cells undergoing apoptosis (21, 22, 26). Since high levels of cyclin transcripts are observed in spring tumors, it is possible that the rv-cyclins play a role in tumor regression by inducing apoptosis.

In summary, investigation into the processes of tumor induction and regression in this unique retroviral system will identify the viral, host, and environmental factors whose interplay drives these events.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank V. Vogt and T. Fox and members of their laboratories for generous advice and use of their facilities. We especially thank B. Andrews for providing yeast strains, plasmids, and experimental advice. We thank A. Arnold for the Prad1 plasmid, B. Calnek and D. Martineau for the walleye cell lines WF2 and WL12, and P. Bowser for tumor samples.

This work was supported by grants from the American Cancer Society and the USDA. L.A.L. was supported by an NIH training grant (CA09682).

REFERENCES

- 1.Anders K, Yoshimizu M. Role of viruses in the induction of skin tumours and tumour-like proliferations of fish. Dis Aquat Org. 1994;19:215–232. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold A. The cyclin D1-PRAD1 oncogene in human neoplasia. J Investig Med. 1995;43:543–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel F M, Brent B, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Smith J A, Seidman J G, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bazan J F. Helical fold prediction for the cyclin box. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1996;24:1–17. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(199601)24:1<1::AID-PROT1>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beeler J F, LarOchelle W J, Chedid M, Tronick S R, Aaronson S A. Prokaryotic expression cloning of a novel human tyrosine kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:982–988. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloom, S., and D. L. Holzschu. Unpublished data.

- 7.Bowser, P. R., K. Earnest-Koons, G. A. Wooster, L. A. LaPierre, D. L. Holzschu, and J. W. Casey. Experimental transmission of discrete epidermal hyperplasia in walleyes. J. Aquat. Anim. Health, in press.

- 8.Bowser P R, Wolfe M J, Forney J L, Wooster G A. Seasonal prevalence of skin tumors from walleye (Stizostedion vitreum) from Oneida Lake, New York. J Wildlife Dis. 1988;24:292–298. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-24.2.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowser P R, Wooster G A. Regression of dermal sarcoma in adult walleyes (Stizostedion vitreum) J Aquat Anim Health. 1991;3:147–150. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowser P R, Wooster G A, Quackenbush S L, Casey R N, Casey J W. Comparison of fall and spring tumors as inocula for experimental transmission of walleye dermal sarcoma. J Aquat Anim Health. 1996;8:78–81. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown N R, Noble M E, Endicott J A, Garman E F, Wakatsuki S, Mitchell E, Rasmussen B, Hunt T, Johnson L N. The crystal structure of cyclin A. Structure. 1995;3:1235–1247. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cann A J, Chen I S Y. Human T-cell leukemia virus type I and type II. In: Fields B N, et al., editors. Fields virology. New York, N.Y: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 1849–1880. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cesarman E, Nador R G, Bai F, Bohenzky R A, Russo J J, Moore P S, Chang Y, Knowles D M. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus contains G protein-coupled receptor and cyclin D homologs which are expressed in Kaposi’s sarcoma and malignant lymphoma. J Virol. 1996;70:8218–8223. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8218-8223.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang Y, Moore P S, Talbot S J, Boshoff C H, Zarkowska T, Godden H, Paterson H, Weiss R A, Mittnacht S. Cyclin encoded by KS herpesvirus. Nature. 1996;382:410–411. doi: 10.1038/382410a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen D-Z, Yang B-C, Kuo T-T. One-step transformation of yeast in stationary phase. Curr Genet. 1992;21:83–83. doi: 10.1007/BF00318659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cullen B R. Mechanism of action of regulatory proteins encoded by complex retroviruses. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:375–394. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.3.375-394.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Day I S, Reddy A S N, Golovkin M. Isolation of a new mitotic-like cyclin from Arabidopsis: complementation of a yeast cyclin mutant with a plant cyclin. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;30:565–575. doi: 10.1007/BF00049332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dowdy S F, Hinds P W, Louie K, Reed S I, Arnold A, Weinberg R A. Physical interactions of the retinoblastoma protein with human D cyclins. Cell. 1993;73:499–511. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90137-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Earnest-Koons K, Wooster G A, Bowser P A. Invasive walleye dermal sarcoma in laboratory-maintained walleyes Stizostedion vitreum. Dis Aquat Org. 1996;24:227–232. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ewen M E, Sluss H K, Sherr C J, Matsushime H, Kato J-Y, Livingston D M. Functional interactions of the retinoblastoma protein with mammalian D-type cyclins. Cell. 1993;73:487–497. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90136-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman R S, Estus S, Johnson E M., Jr Analysis of cell cycle-related gene expression in post-mitotic neurons: selective induction of cyclin D1 during programmed cell death. Neuron. 1994;12:343–355. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukami J, Anno K, Ueda K, Takahashi T, Ide T. Enhanced expression of cyclin D-1 in senescent human fibroblasts. Mech Ageing Dev. 1995;81:139–157. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(95)93703-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Godden-Kent D, Talbot S J, Boshoff C, Chang Y, Moore P, Weiss R A, Mittnacht S. The cyclin encoded by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus stimulates cdk6 to phosphorylate the retinoblastoma protein and histone H1. J Virol. 1997;71:4193–4198. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4193-4198.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hermann C H, Rice A P. Lentivirus Tat proteins specifically associate with a cellular protein kinase, TAK, that hyperphosphorylates the carboxyl-terminal domain of the large subunit of RNA polymerase II: candidate for a Tat cofactor. J Virol. 1995;69:1612–1620. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1612-1620.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holzschu D L, Martineau D, Fodor S K, Vogt V M, Bowser P R, Casey J W. Nucleotide sequence and protein analysis of a complex piscine retrovirus, walleye dermal sarcoma virus. J Virol. 1995;69:5320–5331. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5320-5331.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jänicke R U, Lin X Y, Lee F H H, Porter A G. Cyclin D3 sensitizes tumor cells to tumor necrosis factor-induced, c-Myc-dependent apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5245–5253. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeffrey P D, Russo A A, Poluak K, Gibbs E, Hurwitz J, Massague J, Pavletich N. Mechanisms of CDK activation revealed by the structure of a cyclin A-CDK2 complex. Nature. 1995;376:313–320. doi: 10.1038/376313a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang W, Kahan S, Tomita N, Zhang Y, Lu S, Weinstein B. Amplification and overexpression of the human cyclin D gene in esophageal cancer. Cancer Res. 1992;52:2980–2983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung J U, Stäger M, Desrosiers R C. Virus-encoded cyclin. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7235–7244. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kato J Y, Matsushime H, Hiebert S W, Ewen M E, Sherr C J. Direct binding of cyclin D to the retinoblastoma gene product Prb and Prb phosphorylation by the cyclin D-dependent kinase Cdk4. Genes Dev. 1993;7:331–342. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lammie G, Fantl V, Smith R, Schuuring E, Brookes S, Michalides R, Dickson C, Arnold A, Peters G. D11S287, a putative oncogene on chromosome 11q13, is amplified and expressed in squamous cell and mammary carcinomas and linked to BCL-1. Oncogene. 1991;6:439–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LaPierre L A, Holzschu D L, Wooster G A, Bowser P R, Casey J W. Two closely related but distinct retroviruses are associated with walleye discrete epidermal hyperplasia. J Virol. 1998;72:3484–3490. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3484-3490.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lepold P, O’Farrell P H. An evolutionarily conserved cyclin homolog from drosophila rescues yeast deficient in G1 cyclins. Cell. 1991;66:1207–1216. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90043-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lew D J, Dulic V, Reed S I. Isolation of three novel human cyclins by rescue of G1 cyclin Cln function in yeast. Cell. 1991;66:1197–1206. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90042-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liao S M, Zhang J, Jeffrey D A, Koleske A J, Thompson C M, Chao D M, Viijoen M, Vuuren H J J V, Young R A. A kinase-cyclin pair in the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Nature. 1995;374:193–196. doi: 10.1038/374193a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makela T P, Parvin J D, Kim J, Huber L J, Sharp P A, Weinberg R A. A kinase-deficient transcription factor TFIIH is functional in basal and activated transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5174–5178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mancebo H, Lee G, Flygare J, Tomassini J, Luu P, Zhu Y, Blau C, Hazuda D, Price D, Flores O. P-TEFb kinase is required for HIV Tat transcriptional activation in vivo and in vitro. Genes Dev. 1997;2:2633–2644. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martineau D, Bowser P R, Renshaw R R, Casey J W. Molecular characterization of a unique retrovirus associated with a fish tumor. J Virol. 1992;66:596–599. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.596-599.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martineau D, Bowser P R, Wooster G A, Armstrong G A. Experimental transmission of a dermal sarcoma in fingerling walleyes (Stizostedion vitreum vitreum) Vet Pathol. 1990;27:230–234. doi: 10.1177/030098589002700403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martineau D, Bowser P R, Wooster G A, Forney J L. Histologic and ultrastructural studies of dermal sarcoma of walleye (Pisces: Stizostedion vitreum) Vet Pathol. 1990;27:340–346. doi: 10.1177/030098589002700506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Motokura T, Bloom T, Kim H G, Juppner H, Ruderman J V, Kronenberg H M, Arnold A. A novel cyclin encoded by a bcl-linked candidate oncogene. Nature. 1991;350:512–515. doi: 10.1038/350512a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mucenski M L, Gilbert D J, Taylor B A, Jenkins N A, Copeland N G. Common sites of viral integration in lymphomas arising in AKXD recombinant inbred mouse strains. Oncogene Res. 1987;2:33–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nerenberg M I, Hinrichs S H, Reynolds R K, Khoury G, Jay G. The tax gene of human T-lymphotrophic virus type 1 induces mesenchymal tumors in transgenic mice. Science. 1987;237:1324–1329. doi: 10.1126/science.2888190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nugent J H A, Alfa C E, Young T, Hyams J S. Conserved structural motifs in cyclins identified by sequence analysis. J Cell Sci. 1991;99:669–674. doi: 10.1242/jcs.99.3.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poulet F M, Bowser P R, Casey J W. Retroviruses of fish, reptiles, and molluscs. In: Levy J A, editor. The Retroviridae. Vol. 3. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quackenbush S L, Holzschu D L, Bowser P R, Casey J W. Transcriptional analysis of walleye dermal sarcoma virus (WDSV) Virology. 1997;237:107–112. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rasheed S. Retroviruses and oncogenes. In: Levy J A, editor. The Retroviridae. Vol. 4. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 293–408. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robles A I, Larcher F, Whalin R B, Murillas R, Richie E, Gimenez Conti I B, Jorcano J L, Conti C J. Expression of cyclin D1 in epithelial tissues of transgenic mice results in epidermal hyperproliferation and severe thymic hyperplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenberg N, Jolicoeur P. Retroviral pathogenesis. In: Coffin J M, Hughes S H, Varmus H E, editors. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 475–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosenblatt J D, Miles S, Gasson J C, Prager D. Transactivation of cellular genes by human retroviruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;193:25–49. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78929-8_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ross T M, Pettiford S M, Green P L. The tax gene of human T-cell leukemia virus type 2 is essential for transformation of human T lymphocytes. J Virol. 1996;70:5194–5202. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5194-5202.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rothstein R. Targeting, disruption, replacement and allele rescue: integrative DNA transformation in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:281–301. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sherr C J. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274:1672–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sherr C J. D-type cyclins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:187–190. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stehelin D, Varmus H E, Bishop J M, Vogt P K. DNA related to the transforming gene(s) of avian sarcoma viruses is present in normal avian DNA. Nature. 1976;260:170–173. doi: 10.1038/260170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Swain A, Coffin J F. Mechanism of transduction by retroviruses. Science. 1992;255:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1371365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swanton C, Mann D J, Fleckenstein B, Neipel F, Peters G, Jones N. Herpes viral cyclin/Cdk6 complexes evade inhibition by CDK inhibitor proteins. Nature. 1997;390:184–187. doi: 10.1038/36606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tremblay P J, Kozak C A, Jolicoeur P. Identification of a novel gene, Vin1, in murine leukemia virus-induced T-cell leukemias by provirus insertional mutagenesis. J Virol. 1992;66:1344–1353. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1344-1353.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Walker R. Virus associated with epidermal hyperplasia in fish. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1969;31:195–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang T C, Cardiff R D, Zukerberg L, Lees E, Arnold A, Schmidt E V. Mammary hyperplasia and carcinoma in MMTV-cyclin D1 transgenic mice. Nature. 1994;369:669–671. doi: 10.1038/369669a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wei P, Garber M E, Fang S, Fischer W H, Jones K A. A novel CDK9-associated C-type cyclin interacts directly with HIV-1 tat and mediates its high-affinity, loop specific binding to TAR RNA. Cell. 1998;92:451–462. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80939-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yoshida M, Suzuki T, Fujisawa J, Hirai H. HTLV-1 oncoprotein tax and cellular transcription factors. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;193:79–89. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78929-8_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu Y, Pe’Ery T, Peng J, Ramanathan Y, Marshall N, Marshall T, Amendt B, Mathews M B, Price D H. Transcription elongation factor P-TEFb is required for Tat transactivation in vitro. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2622–2632. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zwijsen R M L, Wientjens E, Klompmaker R, Van Der Sman J, Bernards R, Michalides R J A M. CDK-independent activation of estrogen receptor by cyclin D1. Cell. 1997;88:405–415. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81879-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]