Abstract

Although the antimyeloma effect of lenalidomide is associated with activation of the immune system, the exact in vivo immunomodulatory mechanisms of lenalidomide combined with low-dose dexamethasone (Len-dex) in refractory/relapsed multiple myeloma (RRMM) patients remain unclear. In this study, we analyzed the association between immune cell populations and clinical outcomes in patients receiving Len-dex for the treatment of RRMM. Peripheral blood samples from 90 RRMM patients were taken on day 1 of cycles 1 (baseline), 2, 3, and 4 of Len-dex therapy. Peripheral blood CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ cell frequencies were significantly decreased by 3 cycles of therapy, whereas NK cell frequency was significantly increased after the 3rd cycle. For the myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC) subset, the frequency of granulocytic MDSCs transiently increased after the 1st cycle, whereas there was an increase in monocytic MDSC (M-MDSC) frequency after the 1st and 3rd cycles. Among 81 evaluable patients, failure to achieve a response of VGPR or greater was associated with a decrease in CD8+ cell frequency and increase in M-MDSC frequency after 3 cycles of Len-dex treatment. A high proportion of natural killer T (NKT)-like cells (CD3+/CD56+) prior to Len-dex treatment might predict a longer time to progression. In addition, patients with a smaller decrease in the frequency of both CD3+ cells and CD8+ cells by 3 cycles exhibited a longer time to the next treatment. These results demonstrated that early changes in immune cell subsets are useful immunologic indicators of the efficacy of Len-dex treatment in RRMM.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-016-1861-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Multiple myeloma, Lenalidomide, Low-dose dexamethasone, Natural killer T-like cells, Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM), a plasma cell neoplasm, accounts for approximately 10 % of all hematologic malignancies [1, 2]. Although advances in the management of MM have allowed patients to achieve improvements in high-quality response rates and sustained response durations, most MM patients will nonetheless ultimately relapse or become refractory to their current treatment [3]. Proper therapeutic options are subsequently required in the relapsed or refractory setting. The therapeutic landscape for patients with relapsed-refractory MM (RRMM) has changed dramatically in the last decade with the introduction of biologic small molecules (proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulatory drugs [IMiDs] and HDAC inhibitors). In particular, the combination of lenalidomide and high-dose dexamethasone (Len-Dex) has demonstrated efficacy and safety in patients with relapsed/refractory MM in 2 large, well-designed pivotal clinical trials [4, 5]. It is well known that the efficacy of Len-Dex can be preserved with reduced toxicity by using a lower dexamethasone dose. Thus, lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone (Len-dex) is associated with better short-term overall survival and lower toxicity than Len-Dex in patients with newly diagnosed MM [6]. At present, Len-dex therapy remains standard care in patients with RRMM because patients whose dexamethasone dose was reduced due to toxicity had a better outcome than those who continued on high-dose dexamethasone.

The IMiDs (thalidomide, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide) in particular have not only shown great promise in the clinic as tumoricidal agents but also have immune skewing functions that may contribute to their antimyeloma effect [7]. Thus far, studies investigating lenalidomide-induced immunoactivation have individually focused on T-cell proliferation and function, natural killer (NK) cell activity, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) using in vitro assays [8, 9]. Although the co-stimulatory effects on T cells and NK cells have been heralded as a unique and important property of IMiDs that enhances anti-MM immune activity, these in vitro effects have yet to be firmly corroborated in vivo. Because the impact of Len-dex treatment on tumor-induced immune cell regulation in clinical practice remains unclear, its immunomodulatory effect on the patient’s immune system should be defined in a clinically applicable manner. To look for predictive and pharmacodynamic immunomodulatory biomarkers that may help to clarify treatment efficacy, we performed multicolor flow cytometric analysis of fresh blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from RRMM patients at the time of Len-dex initiation (baseline sample) and after completion of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd cycles. In the context of measuring immunomodulatory effects of lenalidomide, we sought to determine which immune cell subtypes of PBMCs are associated with the antitumor effect after Len-dex treatment in patients with RRMM. In addition, we investigated potential changes in the immune cell frequency in RRMM compared to newly diagnosed MM (NDMM).

Patients and methods

Patients and treatment procedures

RRMM patients who received salvage treatment with Len-dex were eligible for this study. The therapy regimen consisted of lenalidomide 25 mg once daily orally on days 1–21 of each 28-day cycle plus low-dose dexamethasone 40 mg per day weekly, and dose modification was performed according to the recommendations [2, 10]. Thrombosis prophylaxis with low-dose aspirin was used in all patients. Treatment responses were assessed according to the criteria from the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) [11]. To include immune cell populations in addition to baseline biological characteristics as variables affecting the achievement of response, blood samples were collected at baseline prior to the Len-dex treatment and at every cycle through the 3rd cycle (1 cycle = 28 days). Considering the time to first response in prior clinical trials, sample time points were decided [4, 5]. All clinical data were prospectively collected at the time of Len-dex initiation except for cytogenetic and international staging system findings, which were taken from the data established at the time of diagnosis. Cytogenetic risk was available in 81 patients (90 %). Patients with a hypodiploidy or deletion of chromosome 13 determined by conventional cytogenetic study, or t(4;14), t(14;16), and -17p status established by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) of bone marrow (BM) samples at diagnosis were stratified as high risk [11]. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before participation in this study. This study was approved by the institutional review board of each participating institution and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Blood sample collection and isolation of mononuclear cells

Blood samples for the analyses of immune cell population were taken at 4 time points. Briefly, sampling was performed at the time of Len-dex initiation (baseline sample) and after completion of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd cycles. PBMCs were isolated from whole blood (30 mL) collected in EDTA-coated tubes by centrifugation in Ficoll-Paque and were processed immediately.

Flow cytometric analysis

Forward scatter (FSC)/Sideward scatter (SSC) on a linear scale was used for gating live cell population. CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells (CD16+/CD56+), and NKT-like cells (CD3+/CD56+) were analyzed by flow cytometry. NKT cells marking Vβ11+CD3+ were analyzed in some patients (Supplementary Figure 1). Anti-CD3-allophycocyanin (APC), anti-CD4-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), anti-CD8-phycoerythrin (PE), anti-CD16-FITC, and anti-CD56-PE monoclonal antibodies (mAb) were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). MDSCs were divided into two categories of granulocytic (G-MDSC) and monocytic (M-MDSC). For G-MDSC, cells labeled with anti-HLA-DR-PerCP (BD BioSciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and anti-Lineage Cocktail 1 (Lin1)-FITC (BD BioSciences) were gated and then were identified with rat anti-mouse CD11b-APC-Cy™7 (BD BioSciences) and mouse anti-human CD33-V450 (BD BioSciences) antibodies. The frequency of G-MDSC immunophenotyped as the HLA-DR−Lin−CD11b+CD33+ population was quantitated as a percentage of PBMC. For M-MDSC, cells labeled with anti-HLA-DR-PerCP (BD BioSciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and anti-human CD14-APC antibodies (eBioscience) were gated. The frequency of M-MDSC immunophenotyped as the HLA-DR−CD14+ population was quantitated as a percentage of PBMC. Flow cytometry was performed using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences).

Cytokine assays

Serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interferon-gamma (INF-γ), IL-17, IL-3, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) were measured using a commercially available ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Each sample was tested in duplicate, and the average is reported as picograms per milliliter. Soluble IL-2 receptor (sIL-2R) was measured using Human sIL-2R Instant ELISA (eBioscience), and the average of duplicate tests is reported as nanograms per milliliter. The level of IL-10 was tested using a commercially available Cytometric Bead Array (BD Biosciences). Each sample was tested in duplicate, and the average is reported as picograms per milliliter. The sensitivity of detection for IL-10 ranged from 0 to 2500 pg/mL.

Statistical analysis

The study objectives were to identify immunologic predictive factors for achievement of very good partial response (VGPR) or greater and to evaluate the clinical significance for the outcomes listed below. The Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used to test the correlation of categorical variables. The 2-tailed Student’s t test was used to analyze continuous variables, and one-way ANOVA was used to compare continuous variables among three groups. The predictive value of different immune cell populations for achievement of VGPR or greater was assessed using logistic regression in a cohort, including patients who received more than 4 cycles of Len-dex. Covariates with a P value less than 0.1 in univariate analyses were added to the multivariate analysis model.

Time to progression (TTP) was calculated from the start of Len-dex treatment to the date of disease progression, with deaths due to causes other than disease progression censored. Time to next treatment (TTNT) was calculated from the start of Len-dex treatment until the start of the next therapy. Patients who were lost to follow-up were censored at the date of last contact. Survival curves were plotted according to the Kaplan and Meier method, and the log-rank test was used to assess potential prognostic factors. Cox proportional hazard regression model was used for multivariate analysis for TTNT and TTP. Prognostic factors with a P value less than 0.1 in univariate analysis for TTNT or TTP were entered into multivariate analysis. All P values were two sided, and 5 % was chosen as the level of statistical significance.

Results

Patients and treatment response to Len-dex

A total of 90 patients were analyzed in this study (Table 1): 48 males and 42 females with a median age of 61 years (range, 29–84). Median time from diagnosis to Len-dex treatment was 3.2 years (0.5–9.5), and all of the patients were previously exposed to bortezomib, with 54 (60 %) patients receiving both bortezomib and thalidomide. Fifty-four percent of the patients had undergone prior autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). Blood counts at baseline were as follows: WBC 4.8 × 106 cells/mL (range, 0.2–13.0 × 106), Hb 11.0 g/dL (range, 6.8–15.3), and platelets 163 × 106 cells/mL (range, 27–355).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients and response to Len-dex

| Characteristics | All patients (N = 90) (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years; median (range) | 61 (29–84) |

| Sex (M/F) | 48 (53)/42 (47) |

| Serum M-protein | |

| IgG | 47 (52) |

| IgA | 22 (24) |

| Light chain, kappa/lambda | 7 (8)/11 (12) |

| Others | 3 (3) |

| Durie–Salmon stage | |

| I/II/III | 7 (8)/5 (5)/78 (87) |

| ISS stage | |

| I/II/ | 21 (23)/27 (30)/ |

| III/NA | 29 (32)/13 (14) |

| Cytogeneticsa | |

| Standard risk/high risk/NA | 61 (68)/20 (22)/9 (10) |

| Myeloma bone disease on plain radiographs, yes/no | 74 (82)/16 (18) |

| Time since diagnosis, years; median (range) | 3.2 (0.5–9.5) |

| Previous number of therapiesb, median (range) | 2 (1–7) |

| ≤2/>2 | 53 (59)/37 (41) |

| Previous ASCT | 49 (54) |

| Previous therapy before Len-dex | |

| Bortezomib-based regimens | 36 (40) |

| Both Bortezomib- and thalidomide-based regimens | 54 (60) |

| Laboratory data | |

| Serum M-proteinc, g/dL, median (range) | 2.36 (1.02–6.06) |

| Difference between serum iFLC and uninvolved FLC, median (range) | 237.1 (5.2–34151.9) |

| Hb, g/dL, median (range) | 11.0 (6.8–15.3) |

| Ca, mg/dL, median (range) | 9.0 (7.2–12.1) |

| LDH, U/L, median (range) | 395.5 (153–1078) |

| Treatment status d | |

| Still on treatment | 48 (53) |

| Discontinued treatment | |

| Failure to achieve ≥ PR after 4 cycles | 2 (2) |

| Progression | 28 (31) |

| Drug-related adverse event | 6 (7) |

| Death | 4 (4) |

| Follow-up loss | 1 (1) |

| ASCT | 1 (1) |

| Response to Len-dex | |

| Overall response | 68 (76) |

| VGPR or greater | 37 (41) |

| CR/VGPR/PR | 23 (26)/14 (16)/31 (34) |

| SD/PD/NA | 19 (21)/1 (1)/2 (2) |

ASCT autologous stem cell transplantation; Ca calcium; CR complete response; F female; Hb hemoglobin; iFLC involved free light chain; Len-dex lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone; LDH lactate dehydrogenase; M male; NA not available; PD progressive disease; PR partial response; SD stable disease; VGPR very good partial response

aHigh-risk cytogenetics is defined as hypodiploidy or deletion of chr13 on conventional cytogenetics or presence of t(4;14), t(14;16), -17p on fluorescent in situ hybridization and/or conventional cytogenetics. All other cytogenetic abnormalities were considered standard risk

bInduction + ASCT was considered as one therapeutic line

cPatients with measurable serum M protein of at least 1 g per 100 mL were included

dAdministered cycles, median (range): 8 cycles (1–15)

A median of eight cycles (1–15) were administered; the overall response rate was 76 % and response of VGPR or greater was observed in 37 of 90 patients (Table 1). Two patients were not evaluable; one was lost to follow-up and one discontinued Len-dex because of adverse events before evaluation. Median time to progression was 10.8 months (95 % confidence interval [CI] 7.7–13.8). The most common cause of discontinuation of treatment was disease progression (31 %), followed by adverse events (7 %).

Immune cell population of MM patients

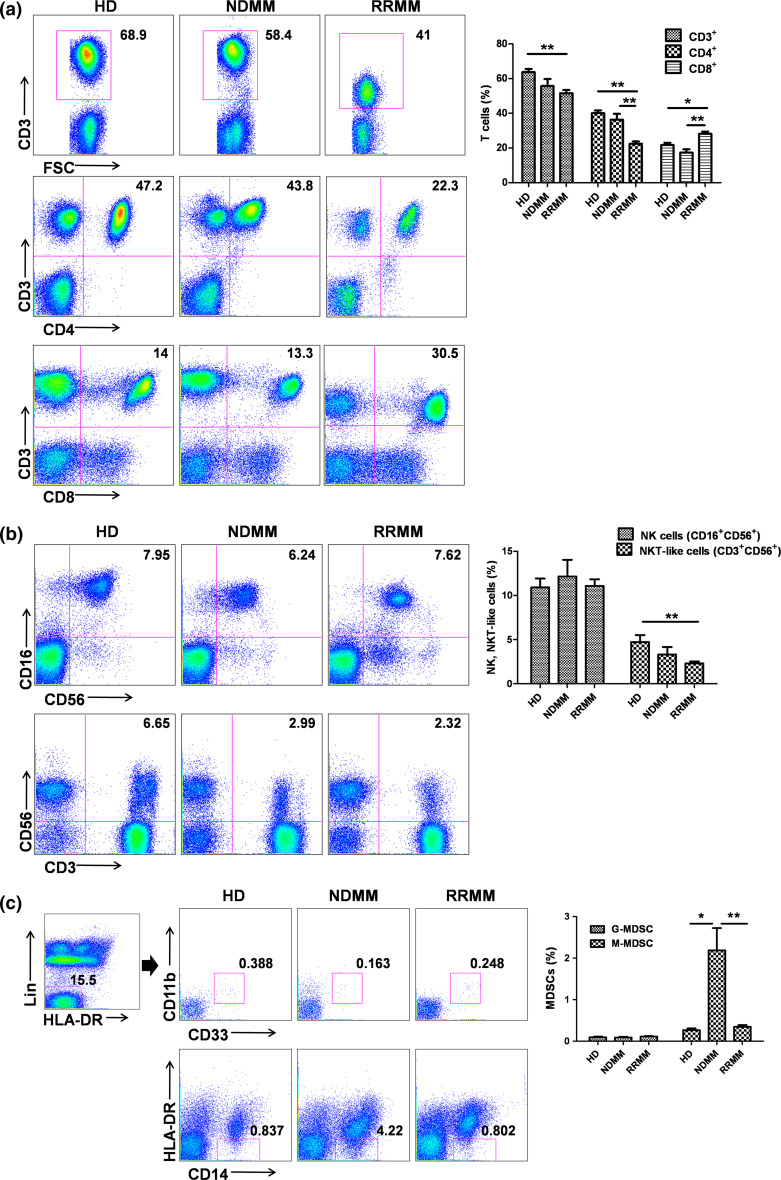

The frequencies of various immune cell populations in the peripheral blood of RRMM patients prior to Len-dex treatment (n = 90) were compared with those of age-matched healthy donors (n = 38) and newly diagnosed MM patients (NDMM) (n = 25, Supplementary Table 1) (Supplementary Table 2) (Fig. 1). RRMM patients had a decreased frequency of CD4+ cells and an increased frequency of CD8+ cells compared with healthy donors and NDMM patients. The NK cell frequency was not significantly different among the three groups, whereas the NKT-like cell frequency in the RRMM patients was significantly decreased compared with that of healthy donors. For the MDSC subset, the frequency of G-MDSCs was not significantly different among the three groups, whereas that of M-MDSCs was significantly higher in the NDMM patients compared with healthy individuals and RRMM patients. Serum levels of myeloma protein (M protein) in NDMM and RRMM patients with measurable values were also compared. Mean serum M protein level was higher in the NDMM patients than in RRMM patients (3.15 ± 0.39 g/dL vs. 1.77 ± 0.52 g/dL, P = 0.010), suggesting an increased frequency of M-MDSCs in patients with high tumor burden.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of immune cell populations between healthy donors (HD), newly diagnosed MM (NDMM), and relapsed-refractory MM (RRMM). FACS plots show representative cell fractions in one healthy donor, one NDMM patient, and one RRMM patient. Blood samples for RRMM were taken before administration of Len-dex. The frequency of CD3+, CD4+, CD8+ T cells (a), natural killer (NK) cells (CD16+CD56+), NKT-like cells (CD3+CD56+) (b), and MDSCs (G-MDSC and M-MDSC) (c) was compared between HD, NDMM, and RRMM. Data (right panel) are presented as mean ± SEM. ANOVA was applied to determine whether there were significant differences between the groups and the Scheffé test was used to analyze groups that showed differences. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01

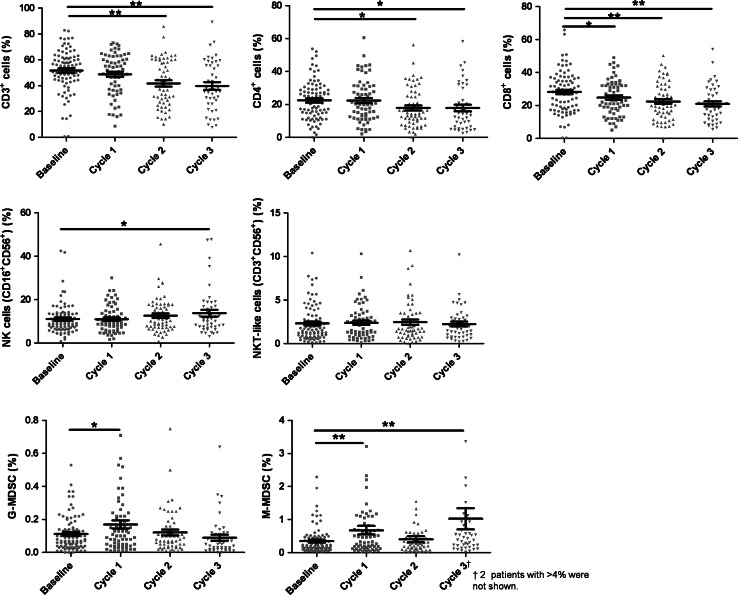

Changes in immune cell population according to Len-dex therapy

Figure 2 shows serial changes in immune cell populations during Len-dex therapy. At baseline, the peripheral blood CD3+ cell frequency was 51.65 ± 1.79 %, which significantly decreased to 41.67 ± 2.44 % (P = 0.001) and 39.72 ± 2.90 % (P < 0.001) after the 2nd and 3rd cycles of therapy, respectively. The frequency of both CD4+ cells and CD8+ cells was also significantly decreased after 3 cycles of therapy; from 22.49 ± 1.29 % at baseline to 17.86 ± 2.00 % after 3 cycles (P < 0.05) for CD4+ cells, and from 28.16 ± 1.35 % at baseline to 20.99 ± 1.61 % after 3 cycles (P < 0.01) for CD8+ cells. In contrast, the NK cell frequency was significantly increased after Len-dex treatment (11.07 ± 0.76 % at baseline to 13.76 ± 1.57 % after 3 cycles, P < 0.05). For the MDSC subsets, the frequency of G-MDSCs was transiently increased after the 1st cycle (P < 0.05), whereas there was an increase in M-MDSC frequency after the 1st and 3rd cycles (P < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

Serial changes in immune cell populations according to Len-dex therapy. The frequency of each cell population at the time of Len-dex initiation (baseline, n = 85) and after completion of 1st, 2nd, and 3rd cycles of administration (n = 64, 59, and 45, respectively) was analyzed. CD3+, CD4+, CD8+ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells (CD16+CD56+), NKT-like cells (CD3+CD56+), and MDSCs (G-MDSC and M-MDSC) showed different changes. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and t tests were used to compare the continuous variables (baseline vs. each time point). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01

Predictive factors for achievement of VGPR or greater

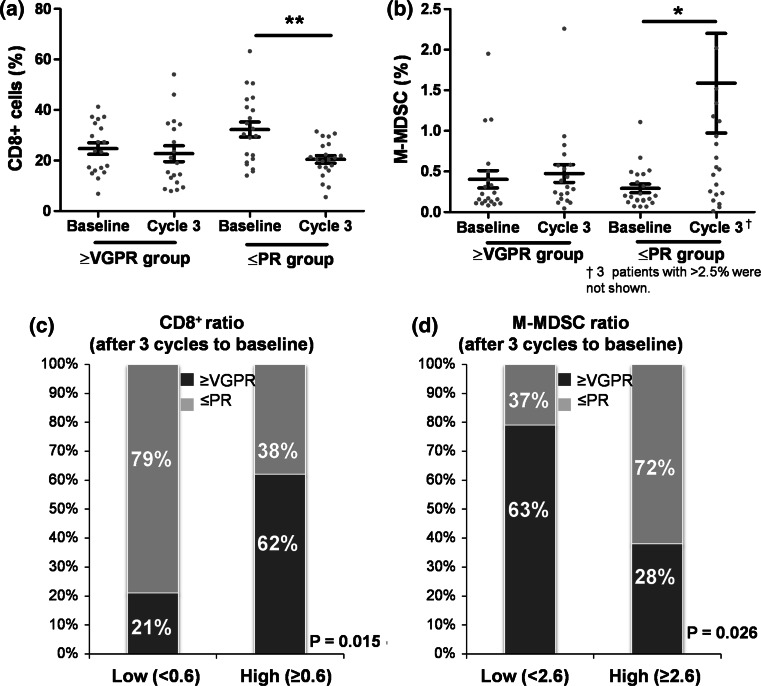

Harousseau et al. showed that patients who achieved VGPR or greater had an overall survival advantage over patients whose response was limited to a PR [12]. Among 81 evaluable patients who received more than 4 cycles of Len-dex, 36 patients obtained VGPR or greater and 45 showed PR or lower. The results of univariate analysis for the potential predictive value of immune cell populations for achievement of VGPR or greater are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Age and Hb level, platelet count, and serum Ca concentration were also associated with achievement of VGPR or greater (Supplementary Table 4). In this study, the change in CD3+ cell frequency after 3 cycles, which was expressed as the ratio of CD3+ cell frequency after 3 cycles to that at baseline (), correlated with the change in CD8+ cell frequency after 3 cycles (r s = 0.931, P < 0.001). Therefore, considering this close relationship, these factors were entered into separate multivariate models.

The changes in CD8+ T cells and M-MDSCs during 3 cycles, which were potential predictors on univariate analysis, were analyzed according to the response to Len-dex (Fig. 3a, b). Next, the patients with continuous value were divided into two groups (low vs. high levels) by a ROC curve analysis, which showed that groups with a high ratio of and a low ratio of M-MDSCafter 3 cycles/baseline were associated with achievement of VGPR or greater (Fig. 3c, d). Ultimately, multivariate analyses revealed that failure to achieve a response of VGPR or greater was associated with a decrease in CD8+ cell frequency (P = 0.043) and an increase in M-MDSC frequency (P = 0.033) after 3 cycles of Len-dex treatment (Table 2). In this study, achieving VGPR or greater correlated with superior TTNT (86.1 % vs. 20.6 %, P < 0.001) and TTP (46.3 % vs. 30.5 %, P = 0.021).

Fig. 3.

Predictive factors for achievement of VGPR or greater. Of 81 patients receiving more than 4 cycles of Len-dex, 45 had paired data (baseline and after 3 cycles). a and b demonstrate changes in CD8+ T cells and M-MDSCs according to the depth of response (VGPR or greater vs. PR or less). Data are presented as mean ± SEM, and paired t tests were utilized to compare the continuous variables (baseline vs. each time point). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. To explore the predictive role of the frequency and ratio (after 3 cycles to baseline) of cell populations for achievement of VGPR or greater, the patients were divided into two groups (low vs. high) by a ROC curve analysis. A high ratio of (≥0.6) had a significant predictive role for achievement of VGPR or greater (c). In contrast, a low ratio of M-MDSCafter 3 cycles/baseline (<2.6) was an independent factor for achievement of VGPR or greater (d)

Table 2.

Multivariate analyses of predictive factors for response (≥VGPR), time to next treatment, and time to progression

| Multivariate variablesa | Response (≥VGPR) (Model I*) | Response (≥VGPR) (Model II*) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95 % CI) | P | Hazard ratio (95 % CI) | P | |

| CD3+ ratiob | ||||

| <0.7 | 1 | – | – | |

| ≥0.7 | 3.07 (0.62–15.21) | 0.171 | – | – |

| CD8+ ratio | ||||

| <0.6 | – | – | 1 | |

| ≥0.6 | – | – | 7.73 (1.06–56.08) | 0.043 |

| NKT-like ratio | ||||

| <1.75 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥1.75 | 6.33 (0.73–54.78) | 0.094 | 6.10 (0.73–50.93) | 0.095 |

| M-MDSC ratio | ||||

| <2.6 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥2.6 | 0.16 (0.02–1.14) | 0.067 | 0.10 (0.01–0.83) | 0.033 |

| Age (years), continuous | 1.03 (0.94–1.13) | 0.547 | 1.03 (0.93–1.13) | 0.597 |

| Hb (g/dL), continuous | 0.97 (0.58–1.63) | 0.905 | 0.88 (0.52–1.51) | 0.648 |

| Platelet (× 109/L), continuous | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.302 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.246 |

| Ca (mg/dL), continuous | 3.55 (0.49–25.54) | 0.209 | 2.84 (0.47–17.19) | 0.257 |

| Multivariate variablesa | TTNT (Model I*) | TTNT (Model II*) | TTP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95 % CI) | P | Hazard ratio (95 % CI) | P | Hazard ratio (95 % CI) | P | |

| Frequency of NKT-like cell, baseline (%) | ||||||

| <1.26 | – | – | – | – | 1 | |

| ≥1.26 | – | – | – | – | 0.40 (0.20–0.81) | 0.011 |

| Frequency of G-MDSC, baseline (%) | ||||||

| <0.2 | 1 | 1 | – | – | ||

| ≥0.2 | 2.04 (0.71–5.81) | 0.183 | 2.43 (0.85–6.94) | 0.098 | – | – |

| CD3+ ratio | ||||||

| <0.8 | 1 | – | – | – | – | |

| ≥0.8 | 0.24 (0.07–0.83) | 0.024 | – | – | – | – |

| CD8+ ratio | ||||||

| <0.6 | – | – | 1 | – | – | |

| ≥0.6 | – | – | 0.33(0.12–0.97) | 0.044 | – | – |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Female | 2.99 (1.01–8.83) | 0.047 | 4.04 (0.85–19.23) | 0.289 | 1.75 (0.87–3.52) | 0.119 |

| Hb (g/dL), continuous | 1.04 (0.71–1.52) | 0.860 | 1.01 (0.69–1.48) | 0.806 | 0.97 (0.79–1.21) | 0.804 |

| Albumin (mg/dL), continuous | 0.64 (0.13–3.02) | 0.568 | 0.70 (0.14–3.45) | 0.446 | 0.60 (0.30–1.19) | 0.144 |

Ca calcium; CI confidence interval; Hb hemoglobin; TTNT time to next treatment; TTP time to progression; VGPR very good partial response

* In this study, CD3+ ratio correlated with CD8+ ratio (r s = 0.931, P < 0.001). Therefore, considering this close relationship, these factors were entered into separate multivariate models

aFrequency and ratio (after 3 cycles to baseline) of cell population were divided into 2 groups by a ROC curve analysis

b“Ratio” indicates after 3 cycles/baseline

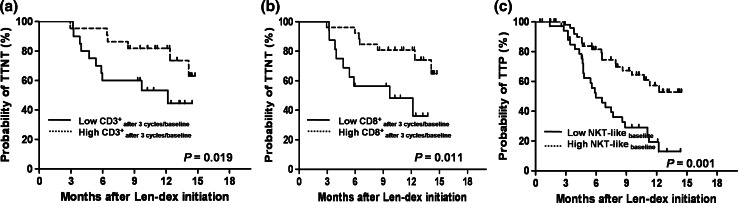

Prognostic factors affecting time to next treatment and time to progression

To evaluate the prognostic value of immune cell populations, we analyzed their effect on TTNT and TTP. In univariate analyses (Supplementary Table 3), a low frequency of G-MDSCs at baseline and after 3 cycles was associated with a longer TTNT, and a smaller decrease in CD3+ cells and CD8+ cells after 3 cycles of Len-dex treatment also showed a longer TTNT. A high frequency of NKT-like cells at baseline was potential predictor of a longer TTP. The patients with continuous data were divided into 2 groups (low vs. high) by a ROC curve analysis. As shown in Fig. 4a, b, patients with a high ratio of (≥0.8) and (≥0.6) had a significantly longer TTNT than those with a low ratio of and (67.7 % vs. 45.2 %, P = 0.019 and 64.8 % vs. 36.2 %, P = 0.011, respectively). A high frequency of NKT-like cells at baseline (≥1.26 %) correlated with superior TTP (49.7 % vs. 13.0 %, P = 0.001) (Fig. 4c). Ultimately, multivariate analyses revealed that a high frequency of NKT-like cells prior to Len-dex treatment might predict a longer time to progression (P = 0.011). In addition, patients with a smaller decrease in frequency of both CD3+ cells and CD8+ cells showed a longer time to next treatment (P = 0.024 and P = 0.044, respectively) (Table 2).

Fig. 4.

Prognostic factors for time to next treatment and time to progression. To explore the prognostic role of the frequency and ratio (after 3 cycles to baseline) of cell populations for TTNT and TTP, the patients with continuous data were divided into two groups (low vs. high) by a ROC curve analysis. High ratio of (≥0.8) (a) and (≥0.6) (b) was associated with a longer TTNT. High frequency of NKT-like cells at baseline (≥1.26 %) was an independent factor for TTP (c)

Changes in serum concentrations of cytokines according to Len-dex therapy

In all patients with available serum samples at baseline (N = 34) and after 3 cycles of therapy (N = 39), we compared the changes in serum concentrations of cytokines using 2-tailed Student’s t test. There was no significant change in cytokine levels after 3 cycles of Len-dex therapy. Next, we analyzed the change in each cytokine level according to the response to Len-dex therapy. No significant changes in any parameter (VEGF, IL-6, INF-γ, IL-10, IL-17, IL-3, IL-1β, TNF-α, and sIL-2R) were observed in the VGPR or greater group or the PR or lower group (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Discussion

The immunostimulatory mode of action underlying the robust antineoplastic activity of lenalidomide has been intensively investigated. In particular, lenalidomide has been shown to stimulate the cytotoxic functions of T lymphocytes and NK cells, to limit the immunosuppressive effect of regulatory T (Treg) cells, and to modulate the secretion of a wide range of cytokines [13]. The use of lenalidomide and dexamethasone in combination is synergistic and results in substantial rates of clinical response in RRMM patients [14, 15]; however, the profound and pleiotropic immunomodulatory activity exerted by Len-dex in patients with RRMM has not been examined in a clinically relevant manner. Although the Len-dex combination synergistically upregulates tumor suppressor genes and caspases, resulting in increased cell cycle arrest and a higher rate of MM cell apoptosis, it has been shown that dexamethasone antagonizes the immunostimulatory capacity of lenalidomide in both NK and T cells in vitro and in vivo [8, 16]. Therefore, the impact of Len-dex on immune function of patients in clinical practice should be examined in a large number of patients in the setting of salvage therapy for RRMM. In the present study, we focused on immune cell subsets in association with the response to Len-dex and treatment outcomes in order to evaluate their emerging potential as cell biomarkers. We showed that the frequency of T cells was decreased after 3 cycles of Len-dex treatment, whereas the NK cell frequency was increased. A temporary increase in G-MDSC frequency and a relatively constant increase in M-MDSC frequency were observed. Achievement of a high-quality response (VGPR or greater) was associated with a smaller decrease in CD8+ cell frequency and a smaller increase in M-MDSC frequency. A high level of NKT-like cells prior to Len-dex treatment predicted a longer TTP and patients with a smaller decrease in both CD3+ and CD8+ cell populations early after Len-dex treatment had a longer TTNT.

Here, we present a phenotypic analysis of the immune cells in patients with NDMM and RRMM. First of all, an opposite frequency of CD4+ and CD8+ cells was observed between NDMM and RRMM, suggesting that CD4+ T-cell immunity is seen more commonly in patients with NDMM, whereas the CD8+ T-cell immune response is present mainly in patients with RRMM. In both MM and its precursor conditions, there is a decrease in the peripheral blood (PB) CD4+/CD8+ T-cell ratio [17, 18]. In line with our results, the PB CD4+/CD8+ T-cell ratio has been shown to decrease upon progression of the disease, with the decrease in CD4+ T cells correlating with advanced disease and increased tumor burden, and serving as an independent sign of poor prognosis [19]. NK cell frequency was not significantly different among NDMM and RRMM patients and normal individuals, whereas NKT-like cell frequency in both NDMM and RRMM was decreased compared with that in healthy donors. Studies of NK cell counts in the PB of MM patients show discordant findings, with some studies showing an increase in NK cells [20, 21], whereas others report no changes [22, 23] or even a decrease [24] compared with healthy controls.

Lenalidomide acts at different levels in the immune system by modifying cytokine production, improving T-cell activity, regulating T-cell co-stimulation, and augmenting the NKT and NK cell cytotoxicity. First of all, the anti-MM effects of lenalidomide may depend on adaptive immunity against malignant plasma cells. IMiDs have been shown to stimulate both cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and helper CD4+ T cells [25], and when nude mice lacking T cells were exposed to IMiDs and tumor cells during the priming phase, they did not demonstrate protection from the tumor, demonstrating that T cells are needed for tumor immunity. Lenalidomide enhances the cytolytic activity of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, which appears to be mediated by IL-2 induced expansion of antigen-specific memory effector CD8+ T cells [26]. In this study, however, Len-dex treatment decreased polyclonal T-cell subset frequencies during the first 3 cycles, and a profound reduction in CD8+ T-cell proliferation was associated with unfavorable outcomes over the course of Len-dex therapy. Lenalidomide increases normal T-cell activity, but this can be abrogated by dexamethasone in vitro [16]. Our findings suggest that any ongoing disease control mediated by the enhancement of adaptive immunity by lenalidomide might be abrogated by the concurrent use of dexamethasone. It has been shown that the enhancement of NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity and CD4+ T-cell production of IL-2 by lenalidomide is severely blunted by dexamethasone [8]. In view of these findings, lower doses of the immunosuppressant dexamethasone could lead to less antagonism of the immunomodulatory effects of lenalidomide, in turn resulting in better disease control.

It is of interest that a favorable outcome in this study correlated with the presence of pre-existing NK T-like cells and further studies are needed to confirm this intriguing but preliminary correlation suggesting a role for pre-existing innate T-cell immunity in the efficacy of Len-dex therapy. CD56+ T cells are not classical iNKT cells but are a broader group of T cells coexpressing NK cell markers [27, 28]. Although we tested Vβ11+CD3+ as a marker for NKT cells in some patients, we found that individual patients had similar trends in the frequency of Vβ11+CD3+ and CD3+CD56+ cells (See Supplementary Fig. 1), providing a possibility that the NKT-like cells (CD3+/CD56+) overlapped NKT cells. A progressive decrease in PB invariant NKT (iNKT) cells according to the evolution in MM disease status remains controversial [29–31]. Functional abnormalities of PB iNKT cells were also reported in MM patients [30], and changes in the MM immune environment may thus render iNKT cells less effective at curbing disease progression. In this study, patients with a higher frequency of NKT-like cells had a prolonged TTP, suggesting that one role of Len-dex in immunostimulation might be to rescue or potentiate the antitumor activities of NKT-like cells. These results are supported by recent studies showing that lenalidomide provided co-stimulation of human iNKT cells [32, 33].

MDSCs are another important immunoregulatory cell population that is also present in cancer patients and suppresses antitumor immunity [34, 35]. Based on previous phenotypic profiles of MDSCs in solid tumors [36], we identified MDSCs with 2 phenotypes, G-MDSCs and M-MDSCs, in MM PB. To date, only a few publications have reported this cell type in MM patients; one describes an increased frequency of human leukocyte antigen D-related (HLA-DR)low monocytes in patients with MM at various stages of their disease and the other reports G-MDSCs in the PB and bone marrow of MM patients [37]. We assessed the presence of each MDSC subtype in MM patients compared with healthy donors and their associations with disease statuses and responses to Len-dex therapy. Interestingly, we found that the frequency of M-MDSCs, but not G-MDSCs, was increased in a cohort of NDMM patients. We also found that the frequency of M-MDSCs in PB correlated with the amount of serum M protein, which is produced by malignant plasma cells. The concentration of M protein was higher in NDMM patients compared with RRMM patients, and M-MDSC frequency was increased in the patients who did not achieve VGPR and had a higher M protein, suggesting that M-MDSCs could be considered as pharmacodynamic biomarkers for the treatment efficacy of Len-dex [38]. Recently, it has been shown that poor clinical response to the therapy was associated with elevated amounts of circulating M-MDSCs in patients with melanoma undergoing ipilimumab treatment [39]. A recent in vitro study demonstrated that lenalidomide with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade inhibits MDSC-mediated immune suppression in MM, suggesting that M-MDSC as a novel predictive marker for lenalidomide combined with immune checkpoint modulator [40]. In this study, however, there was no significant difference in MDSC frequency between RRMM patients and healthy controls. It is possible that there may be some difference in biologic characteristics between tumor-induced and naturally occurring M-MDSCs. Functional analyses are required to investigate the MM-associated immunosuppressive niche and the strict interplay between MM cells and each MDSC subset in terms of the antitumor response induced by Len-dex therapy.

In this study we did not evaluate the proportion of dendritic cells (DCs) and CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells that are affected in patients with MM, which would underline the fact that the immune system is dysregulated as a consequence of the disease [41]. However, for patients with MM in particular, contradictory results have been obtained regarding the level of DCs and Treg cells, making it unclear how Len-dex treatment influences these immune subtypes [42–45]. In addition, intrinsic T-cell or M-MDSC dysfunction following Len-dex treatment was not examined and changes in these functional immune cell subtypes are worth investigating.

In conclusion, in the present study, we observed the change of immune cell populations after Len-dex therapy in a clinically relevant manner and suggested immune subtypes of PBMCs as predictive and pharmacodynamic biomarkers for clinical outcomes. Importantly, the change in the proportion of CD8+ T cells and M-MDSCs early after Len-dex therapy correlated with response to treatment. Baseline NKT-like cell frequency and changes in CD3+ and CD8+ T-cell frequency early after treatment predicted a sustainable antimyeloma effect of Len-dex therapy. These results suggest that early changes in immune cell subsets in the PB at week 12 of Len-dex treatment are useful immunologic indicators of the efficacy of Len-dex treatment in RRMM. Further studies are needed to analyze the functional features of each subtype and characterize the effects of individual drugs on tumor-induced immune cell regulation.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all members at the Catholic Blood and Marrow Transplantation Center, particularly the house staff, for their excellent care of the patients. This study was supported by the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health& Welfare, Republic of Korea (A120175).

Abbreviations

- ASCT

Autologous stem cell transplantation

- BM

Bone marrow

- CI

Confidence interval

- CR

Complete response

- DC

Dendritic cell

- FISH

In situ hybridization

- G-MDSC

Granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- IMiDs

Immunomodulatory drugs

- IMWG

International Myeloma Working Group

- INF-γ

Interferon-gamma

- iNKT

Invariant natural killer T

- Len-Dex

Lenalidomide and high-dose dexamethasone

- Len-dex

Lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone

- MDSC

Myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- MM

Multiple myeloma

- M-MDSC

Monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- NDMM

Newly diagnosed multiple myeloma

- NK

Natural killer

- NKT

Natural killer T

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- RRMM

Refractory/relapsed multiple myeloma

- sIL-2R

Soluble IL-2 receptor

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- Treg

Regulatory T

- TTNT

Time to next treatment

- TTP

Time to progression

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- VGPR

Very good partial response

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Abstract, 57th ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition, December 5–8, 2015, Orlando, FL, USA.

References

- 1.Raab MS, Podar K, Breitkreutz I, Richardson PG, Anderson KC. Multiple myeloma. Lancet. 2009;374:324–339. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60221-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park HJ, Park EH, Jung KW, et al. Statistics of hematologic malignancies in Korea: incidence, prevalence and survival rates from 1999 to 2008. Korean J Hematol. 2012;47:28–38. doi: 10.5045/kjh.2012.47.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larocca A, Cavallo F, Mina R, Boccadoro M, Palumbo A. Current treatment strategies with lenalidomide in multiple myeloma and future perspectives. Future Oncol. 2012;8:1223–1238. doi: 10.2217/fon.12.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weber DM, Chen C, Niesvizky R, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma in North America. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2133–2142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimopoulos M, Spencer A, Attal M, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2123–2132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajkumar SV, Jacobus S, Callander NS, et al. Lenalidomide plus high-dose dexamethasone versus lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone as initial therapy for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:29–37. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70284-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quach H, Ritchie D, Stewart AK, et al. Mechanism of action of immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDS) in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2010;24:22–32. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu AK, Quach H, Tai T, et al. The immunostimulatory effect of lenalidomide on NK-cell function is profoundly inhibited by concurrent dexamethasone therapy. Blood. 2011;117:1605–1613. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-278432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galustian C, Labarthe MC, Bartlett JB, Dalgleish AG. Thalidomide-derived immunomodulatory drugs as therapeutic agents. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4:1963–1970. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.12.1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, Attal M, et al. Optimizing the use of lenalidomide in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: consensus statement. Leukemia. 2011;25:749–760. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Criteria for diagnosis, staging, risk stratification and response assessment of multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2009;23:3–9. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harousseau JL, Dimopoulos MA, Wang M, et al. Better quality of response to lenalidomide plus dexamethasone is associated with improved clinical outcomes in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2010;95:1738–1744. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.015917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotla V, Goel S, Nischal S, et al. Mechanism of action of lenalidomide in hematological malignancies. J Hematol Oncol. 2009;2:36. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-2-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richardson P, Jagannath S, Hussein M, et al. Safety and efficacy of single-agent lenalidomide in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2009;114:772–778. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-196238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kastritis E, Palumbo A, Dimopoulos MA. Treatment of relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Semin Hematol. 2009;46:143–157. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gandhi AK, Kang J, Capone L, et al. Dexamethasone synergizes with lenalidomide to inhibit multiple myeloma tumor growth, but reduces lenalidomide-induced immunomodulation of T and NK cell function. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2010;10:155–167. doi: 10.2174/156800910791054239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raitakari M, Brown RD, Sze D, et al. T-cell expansions in patients with multiple myeloma have a phenotype of cytotoxic T cells. Br J Haematol. 2000;110:203–209. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koike M, Sekigawa I, Okada M, et al. Relationship between CD4(+)/CD8(+) T cell ratio and T cell activation in multiple myeloma: reference to IL-16. Leuk Res. 2002;26:705–711. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(01)00192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kay NE, Leong TL, Bone N, et al. Blood levels of immune cells predict survival in myeloma patients: results of an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group phase 3 trial for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients. Blood. 2001;98:23–28. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez M, San Miguel JF, Gascon A, et al. Increased expression of natural-killer-associated and activation antigens in multiple myeloma. Am J Hematol. 1992;39:84–89. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830390203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van den Hove LE, Meeus P, Derom A, et al. Lymphocyte profiles in multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: flow-cytometric characterization and analysis in a two-dimensional correlation biplot. Ann Hematol. 1998;76:249–256. doi: 10.1007/s002770050397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King MA, Radicchi-Mastroianni MA. Natural killer cells and CD56 + T cells in the blood of multiple myeloma patients: analysis by 4-colour flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1996;26:121–124. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0320(19960615)26:2<121::AID-CYTO4>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Omede P, Boccadoro M, Gallone G, et al. Multiple myeloma: increased circulating lymphocytes carrying plasma cell-associated antigens as an indicator of poor survival. Blood. 1990;76:1375–1379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schutt P, Brandhorst D, Stellberg W, Poser M, Ebeling P, Muller S, et al. Immune parameters in multiple myeloma patients: influence of treatment and correlation with opportunistic infections. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:1570–1582. doi: 10.1080/10428190500472503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stirling D. Thalidomide: a novel template for anticancer drugs. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:602–606. doi: 10.1016/S0093-7754(01)90032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haslett PA, Hanekom WA, Muller G, Kaplan G. Thalidomide and a thalidomide analogue drug costimulate virus-specific CD8 + T cells in vitro. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:946–955. doi: 10.1086/368126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghalamfarsa G, Hadinia A, Yousefi M, Jadidi-Niaragh F. The role of natural killer T cells in B cell malignancies. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:1349–1360. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0743-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Golden-Mason L, Castelblanco N, O’Farrelly C, Rosen HR. Phenotypic and functional changes of cytotoxic CD56pos natural T cells determine outcome of acute hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2007;81:9292–9298. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00834-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nur H, Fostier K, Aspeslagh S, et al. Preclinical evaluation of invariant natural killer T cells in the 5T33 multiple myeloma model. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e65075. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dhodapkar MV, Geller MD, Chang DH, et al. A reversible defect in natural killer T cell function characterizes the progression of premalignant to malignant multiple myeloma. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1667–1676. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan AC, Neeson P, Leeansyah E, et al. Natural killer T cell defects in multiple myeloma and the impact of lenalidomide therapy. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;175:49–58. doi: 10.1111/cei.12196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richter J, Neparidze N, Zhang L, et al. Clinical regressions and broad immune activation following combination therapy targeting human NKT cells in myeloma. Blood. 2013;121:423–430. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-435503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Acebes-Huerta A, Huergo-Zapico L, Gonzalez-Rodriguez AP, et al. Lenalidomide induces immunomodulation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and enhances antitumor immune responses mediated by NK and CD4 T cells. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:265840. doi: 10.1155/2014/265840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montero AJ, Diaz-Montero CM, Kyriakopoulos CE, Bronte V, Mandruzzato S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer patients: a clinical perspective. J Immunother. 2012;35:107–115. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318242169f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagaraj S, Schrum AG, Cho HI, Celis E, Gabrilovich DI. Mechanism of T cell tolerance induced by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:3106–3116. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lechner MG, Megiel C, Russell SM, et al. Functional characterization of human Cd33 + and Cd11b + myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets induced from peripheral blood mononuclear cells co-cultured with a diverse set of human tumor cell lines. J Transl Med. 2011;9:90. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Botta C, Gulla A, Correale P, Tagliaferri P, Tassone P. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in multiple myeloma: pre-clinical research and translational opportunities. Front Oncol. 2014;4:348. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Z, Zhang L, Wang H, et al. Tumor-induced CD14 + HLA-DR (-/low) myeloid-derived suppressor cells correlate with tumor progression and outcome of therapy in multiple myeloma patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2015;64:389–399. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1646-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gebhardt C, Sevko A, Jiang H, et al. Myeloid cells and related chronic inflammatory factors as novel predictive markers in melanoma treatment with ipilimumab. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:5453–5459. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gorgun G, Samur MK, Cowens KB, et al. Lenalidomide enhances immune checkpoint blockade-induced immune response in multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:4607–4618. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brimnes MK, Vangsted AJ, Knudsen LM, et al. Increased level of both CD4 + FOXP3 + regulatory T cells and CD14 + HLA-DR(-)/low myeloid-derived suppressor cells and decreased level of dendritic cells in patients with multiple myeloma. Scand J Immunol. 2010;72:540–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2010.02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chauhan D, Singh AV, Brahmandam M, et al. Functional interaction of plasmacytoid dendritic cells with multiple myeloma cells: a therapeutic target. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brimnes MK, Svane IM, Johnsen HE. Impaired functionality and phenotypic profile of dendritic cells from patients with multiple myeloma. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;144:76–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03037.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beyer M, Kochanek M, Giese T, et al. In vivo peripheral expansion of naive CD4 + CD25high FoxP3 + regulatory T cells in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;107:3940–3949. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prabhala RH, Neri P, Bae JE, et al. Dysfunctional T regulatory cells in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;107:301–304. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.