Abstract

Cross-linked actin networks (CLANs) in trabecular meshwork (TM) cells may contribute to increased IOP by altering TM cell function and stiffness. However, there is a lack of direct evidence. Here, we developed transformed TM cells that form spontaneous fluorescently labeled CLANs. The stable cells were constructed by transducing transformed glaucomatous TM (GTM3) cells with the pLenti-LifeAct-EGFP-BlastR lentiviral vector and selection with blastcidin. The stiffness of the GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells were studied using atomic force microscopy. Elastic moduli of CLANs in primary human TM cells treated with/without dexamethasone/TGFβ2 were also measured to validate findings in GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells. Live-cell imaging was performed on GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells treated with 1μM latrunculin B or pHrodo bioparticles to determine actin stability and phagocytosis, respectively. The GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells formed spontaneous CLANs without the induction of TGFβ2 or dexamethasone. The CLAN containing cells showed elevated cell stiffness, resistance to latrunculin B-induced actin depolymerization, as well as compromised phagocytosis, compared to the cells without CLANs. Primary human TM cells with dexamethasone or TGFβ2-induced CLANs were also stiffer and less phagocytic. The GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells are a novel tool for studying the mechanobiology and pathology of CLANs in the TM. Initial characterization of these cells showed that CLANs contribute to at least some glaucomatous phenotypes of TM cells.

Keywords: Glaucoma, trabecular meshwork, cross-linked actin networks, stiffness, actin, latrunculin, phagocytosis

1. Introduction

Glaucoma is a leading cause of blindness worldwide. This optic neuropathy is characterized by the loss of retinal ganglion cells and the concentric loss of visual fields. Many studies show that elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) is the most important risk factor and modifiable factor for the development and progression of glaucoma (2000). More importantly, lowering IOP to a safe level is currently the only clinically proven method in managing glaucoma and preserving patients’ visual function.

Glaucomatous ocular hypertension (OHT) is due to pathological changes in the trabecular meshwork (TM) tissue which is the primary site for aqueous humor outflow resistance. The TM is located at the anterior chamber angle consisting of TM cells and beams. The pathological findings in the TM include loss of TM cells, compromised TM functionality, excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition, as well as increased TM tissue stiffness (Stamer and Clark, 2017).

Besides the changes described above, the actin cytoskeleton in glaucomatous TM cells and tissues may form specialized geodesic structures called cross-linked actin networks (CLANs), which were first reported by Clark and colleagues (Clark et al., 1995a; Clark et al., 1994; Hoare et al., 2009b; Wilson et al., 1993). Increased CLAN formation has been reported in glaucomatous TM tissues as well as in human, mouse, bovine, and porcine TM cells treated with glucocorticoids or TGFβ2 (Clark et al., 1995a; Clark et al., 1994; Mao et al., 2013; O'Reilly et al., 2011; Wilson et al., 1993). Notably, both glucocorticoids and TGFβ2 are glaucoma-associated factors that are able to induce glaucomatous changes in the TM and OHT in experimental models including cell culture, anterior segment organ perfusion culture, as well as in vivo mouse eyes (Clark et al., 1995b; Clark and Wordinger, 2009; Montecchi-Palmer et al., 2017a; Patel et al., 2017; Shepard et al., 2010; Sugali et al., 2021; Wordinger et al., 2014). CLANs are three dimensional dome-like structures around the nucleus or at the periphery of the TM cell. CLANs consist of numerous adjacent triangles formed by F-actin (Bermudez et al., 2017; Clark et al., 1994). The sides of these triangles are usually called spokes and the vertices are called hubs (Bermudez et al., 2017; Clark et al., 1994).

Although CLANs were discovered over twenty years ago and have been characterized for their morphology and actin binding proteins (Bermudez JY, 2016; Filla et al., 2006), little is known about its assembly/disassembly or its functional implication in TM cells. While CLANs are believed to increase TM cell stiffness and contribute to the pathophysiology of the TM (Bermudez et al., 2017), no direct evidence has been provided. Whether CLAN formation affects cell functions (such as phagocytosis, ECM remodeling, cell migration etc.) is also unknown. While almost all CLAN related research has been done using primary TM cells, no CLAN formation has been reported thus far in any transformed TM cells such as GTM3 or HTM5 lines. All these gaps in knowledge are primarily due to the difficulties in the induction and visualization of CLANs in appropriate cell types.

Due to the low formation rate of CLANs in naïve primary TM cells, TGFβ2 and/or glucocorticoids are frequently used as glaucomatous insults to induce CLANs. However, these treatments will also change TM cell morphology, biology, and their associated ECM proteins due to the activation/inhibition of various signaling pathways. Also, because of donor variability and heterogeneity of isolated TM cells, the induction rate of CLANs varies significantly from batch to batch and from one cell strain to another. Finally, since primary human TM (pHTM) cells have very limited passage numbers, a new transduction experiment and cell strain will have to be initiated each time which further increases the difficulty and decreases the reproducibility of CLAN research. Besides these pathologic stimulus-based approaches, Fujimoto and colleagues used an insect virus to overexpress actin-GFP fusion protein in primary porcine TM cells treated with dexamethasone (Fujimoto et al., 2016). Though success in CLAN formation was observed 72h after transfection, its stability and reproducibility in pHTM cells are unclear. Keller and colleagues used SiR-actin to stain actin in live TM cells and studied actin changes, extracellular vesicles, and phagocytosis (Keller and Kopczynski, 2020). However, CLAN formation was not studied or reported.

Therefore, there is a critical need for the development of new cell models which can facilitate the study of CLAN biomechanics, formation & disassembly, dynamics, and their implication in cell homeostasis. Here, we reported the establishment of stably transduced transformed human TM cells based on the widely used GTM3 cell line. Our new transgenic cells, GTM3-LifeAct-GFP (LifeAct is a small peptide that binds to F-actin) (Riedl et al., 2008), form CLANs without glucocorticoid or TGFβ2 induction.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Lentiviral particle preparation

The pLenti-Lifeact-EGFP-BlastR vector was a kind gift from Dr. Ghassan Mouneimne (Addgene plasmid # 84383; http://n2t.net/addgene:84383; RRID: Addgene_84383) (Padilla-Rodriguez et al., 2018). The provirus was transduced into LentiX-293T cells (Takara Bio USA, Mountain View, CA) using the Lenti-X packaging single shot kit (Takara Bio USA) to produce lentiviral particles. Conditioned medium was collected according to manufacturer’s instructions. After cell debris removal, the supernatant was ultracentrifuged at 40000g at 4°C for 4 hours to concentrate viral particles. Viral titer was measured using the Lenti-X™ qRT-PCR Titration Kit (Takara Bio USA).

2.2. Construction of the GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells

The transformed glaucomatous human trabecular meshwork cells (GTM3) (a kind gift from Alcon Research Laboratory, Fort Worth, TX) (Pang et al., 1994) were cultured in 60mm dishes in Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. At approximately 60% confluence, 20μl of lentivirus (1.5 x 105 copies/μl) was used to transduce the GTM3 cells. After 24 hour-transduction, medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 10μg/ml blasticidin S hydrochloride (Catalog #15205; Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) for selection. Cell death was monitored using light microscopy, and LifeAct-GFP fusion protein expression was monitored using epifluorescent microscopy. Approximately 75% cells were dead after 48 hours of treatment with 10μg/ml blasticidin. Then, blasticidin was reduced to 2.5μg/ml. Cell selection was continued until only several cell colonies with strong GFP signal remained. Medium containing 2.5μg/ml blasticidin was changed every 3 days until the cells became confluent. These cells were preserved in liquid nitrogen for long-term storage.

2.3. Live imaging of actin depolymerization in GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells

GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells were seeded at 5 x 103 cells/well in the 96-well plate with 1.5H (170±5um in thickness) glass bottom (CellVis, Mountain View, CA), and cultured with Opti-MEM supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum, 1% glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were monitored daily for spontaneous CLAN formation under epifluorescent microscopy. Once CLANs were present, culture medium was gently removed and replaced with fresh medium containing 1μM latrunculin B (Catalog#: sc-203318; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX). Time lapse images were captured at 60X using the Nikon Eclipse Ti2 microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY), scheduled every 1 minute. The cells were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 using a stage top incubator (Tokai, Shizuoka-ken, Japan) during live cell imaging. After treatment, the medium containing latrunculin B was removed. The cells were washed twice with PBS and replaced with fresh medium. Time lapse images of actin repolymerization was captured under the same conditions described previously.

2.4. Primary human TM cell culture

Primary human TM cells were isolated from non-glaucomatous donor corneoscleral rims (SavingSight Eye Bank, St. Louis, MO) as described previously (Morgan et al., 2014). For characterization of pHTM cells, all cell strains were subjected to dexamethasone (DEX)-induced expression of myocilin as recommended (Keller et al., 2018), only DEX-responsive cell strains (cells that formed CLANs after DEX treatment) were used in our study. For all experiments, pHTM cells were used between passages two and six. To induce CLAN formation, pHTM cells plated on a 50 mm diameter glass bottom FluoroDish (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) were treated with 100 nM DEX or 5 ng/ml TGFβ2 for 5 days in growth media (DMEM:F12) containing 1% fetal bovine serum, 1% glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Some pHTM cells were cultured in 96-well glass bottom plates (Cellvis) with Opti-MEM with supplements and treated with 5ng/ml TGFβ2 for 14 days to induce CLANs.

2.5. Atomic force microscopy

GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells:

GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells were plated in Opti-MEM supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum, 1% glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, on a 50 mm diameter glass bottom FluoroDish (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL), cultured for 5 days in the presence of 2.5 μg/ml blasticidin, and observed daily for the generation of stable CLANs.

Primary human TM (pHTM) cells:

One hour prior to mechanical characterization, pHTM cells were incubated with 1 μM SiR-actin and 5 μM verapamil (Cytoskeleton Inc., Denver, CO) in the cell culture incubator. After the incubation period, media was replaced with fresh growth medium containing with or without 100 nM DEX or 5ng/ml TGFβ2.

Both cells:

Following this, cells were visualized by a Leica DMi8 inverted fluorescence microscope (using the GFP channel for GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells and Cy5 channel for SiR-actin labelled pHTM cells) coupled with a Bruker BioScope Resolve atomic force microscope (Bruker, CA). Cells with or without CLANs were identified and their mechanical properties characterized using a PeakForce™ QNM™ live-cell cantilever (Bruker probes, CA) with a nominal tip radius of 70 nm and spring constant (κ) of 0.1 N/m. Force-distance curves were obtained from 5-10 cells, with 3 force curves per cell, per experiment. Three independent experiments were performed for these measurements. Elastic moduli were determined by using a cone-sphere model (Briscoe et al., 1994) (eq.1-3, supplementary figure 1A). Also, to understand if changes in elastic modulus (if any) were due to viscous or elastic components in cells, a measure of change in the viscoelastic behavior (hysteresis) was also measured (supplementary figure 1B) from the force distance curves(Jiang et al., 2018) without any additional hold/time-dependent experiments.

| Equation 1 |

where, , , is Poisson’s ratio (0.5), , , (15°), and the contact radius, a, is derived from (eq.2)

| Equation 2 |

and, spherical contact radius, is derived from (eq.3)

| Equation 3 |

2.6. Phagocytosis Assay

Approximately 5x103 GTM3-LifeAct-GFP or pHTM cells were seeded into individual wells in the 96 well plate with 1.5H glass bottom (CellVis). The GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells were cultured with OptiMEM containing 1% fetal bovine serum, 1% glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin for about 6-8 days until CLANs were detected using the Nikon Eclipse Ti2 microscope. Primary HTM cells were cultured with 5ng/ml TGFβ2 for 14 days for CLAN induction.

Prior to phagocytosis assays, 2ml Opti-MEM medium was added to each vial of pHrodo Red S. aureus bioparticles (Catalog#: A10010; Thermo fisher scientific) and vortexed to make a stock solution at 1mg/ml. The stock solution was then diluted at 1:10 with Opti-MEM and sonicated in glass vials at 37°C for 8-10 minutes to prepare the working solution. After removal of culture medium from individual wells, 100μl sonicated working solution (resuspended pHrodo bioparticles) was added to the wells and incubated at 37°C overnight before live imaging using the Nikon Eclipse Ti2 microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY). For pHTM cells, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, stained with DAPI, phalloidin-Alex-488 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and imaged using the Zeiss LSM700 confocal microscope (Zeiss, San Diego, CA).

2.7. CLAN induction assay

GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells were seeded in the 96 well plate with 1.5H glass bottom (CellVis). The cells were treated with or without 5ng/ml TGFβ2 (R&D Systems) or 0.1% ethanol (EtOH) or 100nM dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in EtOH for 7 days. Some cells were incubated with Hoechst (Thermo Fisher Scientific), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and used for CLANs and cell number counting. The other cells were first counted in living imaging mode for CLAN+ cells, followed by fixation, DAPI staining, and were then counted for nuclei. For nuclear number counting, the Image J software was used (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/download.html). The percentage of CLAN+ cells vs. nuclear numbers were calculated and analyzed using Student’s t-test. One-way ANOVA was not used since there was no cross-group comparison (control vs. TGFβ2; EtOH vs. DEX).

3. Results

3.1. Spontaneous CLAN formation was visualized in transgenic GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells

GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells were constructed by transducing GTM3 cells with the pLenti-LifeAct-EGFP-BlastR lentiviral vector and blasticidin selection. LifeAct is a 17 amino acid peptide that binds F-actin (Riedl et al., 2008). Due to its small size, LifeAct is believed to have less interference with actin dynamics (Riedl et al., 2008). The expression of the LifeAct-GFP fusion protein enabled us to visualize actin microfilaments in live cells.

Spontaneously formed CLANs were observed in a small population (CLAN+ cells vs. DAPI+ cells; 153/426,527= 0.036%) of the GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells without any CLAN inducing agents such as TGFβ2 or DEX. CLANs were defined using published standard (Wade et al., 2009). These CLANs could be visualized as early as 4 days after seeding. In this study, we used the published definition of CLANs (actin polygons containing at least two adjacent triangles) (O'Reilly et al., 2011) to determine their occurrence in transduced cells. Although the CLAN formation rate was low, we noted that the CLANs were consistent and reproducible among different passage numbers (from P55-P65; GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells were established at P55), after freeze-thaw cycles, in two different labs (Indiana University School of Medicine and University of Houston).

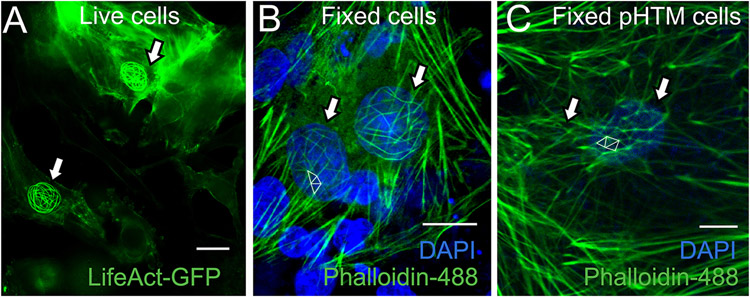

In published studies, CLANs can be found in the perinuclear region and in the periphery of the TM cell (Clark et al., 1995a; Clark et al., 1994; Filla et al., 2006; Montecchi-Palmer et al., 2017b). In GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells, majority of the CLANs were located in the perinuclear region (Figure 1). Compared to the CLANs in primary HTM cells (Figure 1C), these CLANs are more spherical-like with a smooth contour around the nucleus (Figure 1A and 1B). The CLANs in live cells consistently demonstrated much brighter fluorescent signals (Figures 1A and 4; Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1. Spontaneous CLAN formation in GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells.

A) Live imaging of the GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells. Arrows: CLANs. B) The cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde and stained with Phalloidin-488 (Green, for F-actin) and DAPI (Blue). C) Morphology of CLANs in fixed primary human trabecular meshwork (pHTM) cells. Arrows: CLANs. White triangles: definition of CLANs. Scale bars: 20μm.

3.2. CLANs increased the stiffness of GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells and pHTM cells

Although increases in cell stiffness are believed to result from cytoskeletal remodeling and possibly CLANs, there is no direct evidence showing CLANs affect the mechanical property of TM cells. Thus, we used AFM to compare the stiffness of GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells with or without spontaneously formed CLANs. Using these cells to study cell stiffness is advantageous because: 1) CLANs could be visualized without additional labeling, avoiding phototoxicity/bleaching; 2) There was no interference due to glucocorticoid or TGFβ2 treatment related biological changes; and 3) combining live cell imaging and AFM allowed us to distinguish CLAN+ and CLAN− cells within the same culture, which minimizes variations.

Using AFM, we first found that the elastic modulus of GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells was consistent between experiments (at least 5-7 cells per experiment per condition are reported here). This is particularly important considering large variability observed between primary cells from different donors. More importantly, we found that the CLAN+ cells were significantly stiffer than CLAN− cells (Figure 2A). We also found a significant decrease in the factor of viscosity () in CLAN+ cells compared with CLAN− cells, and we hypothesize that the dominance of elastic factors (e.g. cytoskeleton) may restrict the movement of organelles and proteins within these cells (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. CLANs increased GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cell stiffness and lowered cell viscosity.

CLAN+/− GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells were identified using epifluorescent microscopy coupled to the AFM and characterized biomechanically. (A) Elastic modulus (stiffness) and (B) the factor of viscosity (ratio of viscous energy to sum of viscous and elastic energy) were determined. CLAN+ GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells showed significantly higher elastic modulus and lower factor of viscosity compared to CLAN− GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells or naïve GTM3 cells. CLAN− GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells and naïve GTM3 cells were similar (P>0.05). N=3 independent experiments. In each experiment, 5 CLAN+, 7 CLAN−, and 7 naïve cells were studied. The different color represents each replicate. One-way ANOVA and Tukey posthoc tests were used. **: p<0.01, ****: p<0.0001.

To determine the impact of the LifeAct-GFP protein on cell stiffness and factor of viscosity, we measured the two parameters in naïve GTM3 cells. We found that 1) naïve GTM3 cells had similar stiffness and viscosity to GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells without CLANs; and 2) they were less stiff but more viscous than GTM-LifeAct-GFP cells with CLANs (Figure 2). Therefore, incorporation of LifeAct-GFP into the actin microfilament does not affect cell stiffness or viscosity.

Since the biology of transformed TM cells may be different from pHTM cells, we determined the stiffness of CLAN+ and CLAN− pHTM cells using AFM . Live pHTM cells were labelled with SiR-actin to enable visualization and identification of actin structures and CLANs for AFM.

We found that both DEX and TGFβ2 treatment induced CLAN formation in pHTM cells (Figure 3A). Prior to performing indentation over the nuclear region of cells, imaging of cells (at least 5-7 cells per experiment per condition) using the AFM demonstrated the occurrence of CLANs and that this was distinct from occurrence of stress fibers (Figure 3B). The modulus of CLAN+ pHTM cells was significantly higher than CLAN− or control pHTM cells regardless of the method used to induce CLANs (Figure 3C). Therefore, CLANs increase the stiffness of both transformed HTM and pHTM cells.

Figure 3. DEX or TGFβ2 treatment increased pHTM cell stiffness via CLAN formation.

(A) Untreated pHTM cells and those treated with 100 nM DEX or 5 ng/ml TGFβ2 were labelled with SiR-actin and the presence or absence of CLANs were visualized in live cells. White arrows: CLAN− cells. Yellow arrows: CLANs. Inserts (lower right corner): detailed views of CLANs. (B) Presence of CLANs above the nuclear region were confirmed by imaging in peak force tapping mode with AFM. (C) Elastic modulus of CLAN +/− cells were determined from three independent donor strains (N=3; biological repeats/experiments). In each experiment, 5 CLAN+, 7 CLAN−, and 7 naïve cells were used. Data are represented as a cello plot. The different color represents each replicate. One-Way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison were used. *: p<0.05.

3.3. CLANs were resistant to actin depolymerization

CLANs are made of F-actin whose formation is controlled by a balance between G-actin polymerization and depolymerization. Since F-actin and CLANs in GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells could be directly visualized, we determined whether CLANs are resistant to the actin depolymerization agent, latrunculin B. Latrunculin B sequesters G-actin proteins and prevents them from being incorporated into F-actin. Studies showed that Latrunculin B relaxes TM cytoskeleton (Murphy et al., 2014; Sabanay et al., 2006).

GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells (with and without CLANs in the same culture dish) were treated with 1μM latrunculin B and monitored using epifluorescent microscopy (Figure 4A). We found that latrunculin B treatment caused actin stress fibers to disassemble in about 1 minute (Figure 4B). Since LifeAct-GFP binds to F-actin, GFP signal faded along with the disassembly of actin stress fibers (Figure 4B-D). The cells without CLANs became round and some cells detached during prolonged treatment. In contrast, CLANs were still visible until up to 1.5 hours of latrunculin B treatment (Figure 4C). We then washed out latrunculin B with PBS and added old conditioned medium collected before adding latrunculin B to keep the extracellular environment consistent. After a further incubation of 18.5 hours (20 hours after initial latrunculin B treatment), we found the CLANs reformed in the same TM cells. Videos files of additional cells (composed by stacking time-lapsed images) are included in Supplementary Videos 1 and 2.

Figure 4. CLANs in GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells were resistant to latrunculin B.

GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells with or without CLANs were treated with 1μM latrunculin B and live imaged. (A) Before treatment. (B) 1 min after treatment. (C) 90 min after treatment but right before latrunculin B washout. (D) 20 hr from the adding of latrunculin B/18.5 hr after latrunculin B washout. Green: LifeAct-GFP, which binds to F-actin. Arrows: the CLAN+ cell. Triangles: stress fibers (Due to focal plane differences, images were focused on CLANs, not stress fibers). Multiple cells were studied in at least 3 different experiments, and a representative image series is shown. Please see supplemental videos 1 and 2 for more information. Scale bar: 20μm.

3.4. CLAN containing GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells were less phagocytic

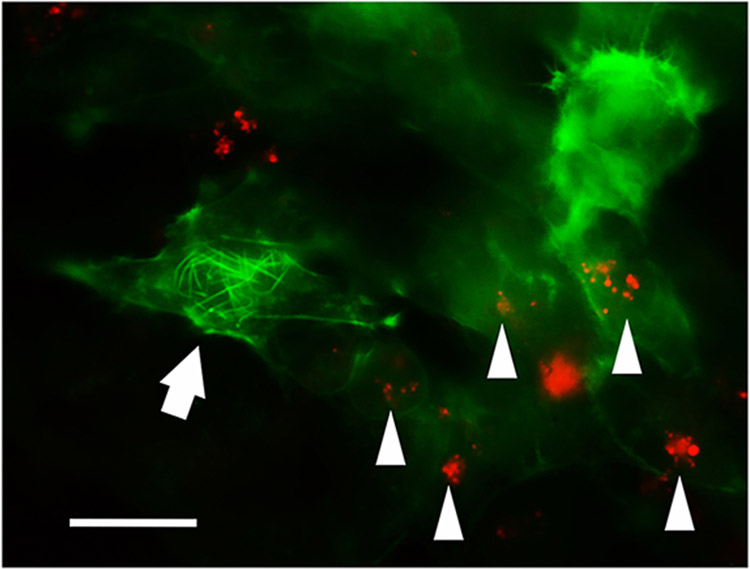

Since 1) phagocytosis is an important function of TM cells (Stamer and Clark, 2017); 2) phagocytosis can be inhibited by glucocorticoid treatment (Zhang et al., 2007); and 3) glucocorticoid induces CLANs (Clark et al., 1994), we determined whether CLANs would affect TM cell phagocytosis. We used the pH sensitive pHrodo Red bioparticles because they send out fluorescent signal only when they are in the low pH environment such as in the phagosome. We found that CLAN+ cells did not phagocytose bioparticles while CLAN− cells did (Figure 5 and Supplemental Figure 1). At least 3 different experiments were conducted and at least

Figure 5. CLANs decreased GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cell phagocytosis.

GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells (Green) were incubated with pHrodo Red bioparticles (red dots). Arrow: a CLAN+ cell; triangles: CLAN− cells. Multiple cells were studied in at least 3 different experiments , and a representative image is shown. Please see supplemental Figure 1 for more information. Scale bar: 20μm.

We also determined if CLANs affect pHTM cell phagocytosis. We treated HTM21-0368 cells (a pHTM cell strain) with 5ng/ml TGFβ2 for 14 days to induce CLAN formation. Then, the cells were treated with the same pHrodo Red bioparticles overnight, fixed, and stained with DAPI and phalloidin for imaging. We found that CLAN+ cells engulfed less bioparticles compared with CLAN− cells (Figure 6).

Figure 6. CLANs decreased pHTM cell phagocytosis.

Primary HTM cells were treated with 5ng/ml TGFβ2 for 14 days to induce CLAN formation. The cells were treated with pHrodo bioparticles (red; B and F). After incubation with bioparticles overnight, the cells were fixed and stained with DAPI (blue; A and E) and phalloidin (green; C and G). (D) and (H): color merged images of (A-C) and (E-G), respectively. (I): enlarged view of circled region in (H). A representative image is shown. Please see supplemental Figure 2 for more information. Scale bar: 20μm.

3.5. TGFβ2 or DEX did not induce more CLAN formation in GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells.

Since TGFβ2 and DEX induce CLAN formation in pHTM cells, we determined if they also induce CLANs in GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells. The cells were treated with 5ng/ml TGFβ2 or 100nM DEX or their controls (no treatment or 0.1% EtOH, respectively) for 7 days. At the end of treatment, the cells were live stained with Hoechst and then fixed for counting. Some cells were counted in living imaging mode for CLANs followed by fixed, DAPI staining, and counting for nuclei.

We found that TGFβ2 did not increase CLAN+ cell ratio (Student’s t-test: p>0.05, N=24) (Figure 7). Surprisingly, DEX decreased CLAN+ cell ratio (Student’s t-test: p<0.01, N=24) (Figure 7).

Figure 7. TGFβ2 or DEX did not induce CLAN formation in GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells.

GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells were seeded onto 96-well glass bottom plates, treated with or without 5ng/ml TGFβ2, 0.1%EtOH, or 100nM DEX for 7 days. CLAN+ cells and nuclei (stained with DAPI or Hoechst) were counted and the percentage of CLAN+ cells over nuclear numbers were compared using Student’s t-test. N=24. NS: not significant. **: p<0.01.

4. Discussion

The transgenic TM cells, GTM3-LifeAct-GFP, enabled us to monitor the actin cytoskeleton in live cells. To our best knowledge, these transformed TM cells are the first that has shown spontaneous CLAN formation and has allowed us to visualize CLANs and observe their dynamics in real time. Using these cells and pHTM cells, we provided direct evidence that CLANs increase TM cell stiffness, contribute to increased actin stability and reduced sensitivity to actin depolymerization drugs, and inhibit TM cell phagocytosis.

Transformed HTM cells are biologically different from pHTM cells. The gross morphology of CLANs found in GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells and pHTM cells/HTM tissues (Hoare et al., 2009a) differ slightly. The CLANs in our cells appear to be more spherical while those in pHTM cells are more web-like. We speculate that this difference is due to the differences in nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio and cell morphology. Specifically, since GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells have a large nucleus, relatively less cytoplasm, and a more round shape, CLANs developed in these cells are likely to be more spherical, compared to CLANs in pHTM cells. Additional studies related to actin modifier proteins involved comparing CLAN formation in primary vs. GTM-LifeAct-GFP cells are required.

Also, the incidence of spontaneous CLAN formation in our cells was low, compared to that of DEX or TGFβ2-induced CLANs in pHTM cells. The DEX-induced CLANs formation rate in pHTM cells were about 20-60% (Clark et al., 1994). In another study, we found that TGFβ2-induced CLAN formation rate was about 20-30% in pHTM cells (Montecchi-Palmer et al., 2017b). In contrast, the spontaneous formation of CLANs in our cells is about 0.036% (153CLAN+ cells in a total of 426527 cells). We would like to emphasize that the actual CLAN formation rate varies from culture to culture, and it is very likely to be different from 0.036% due to passage numbers and culture conditions.

However, these spontaneous CLAN forming cells are an invaluable tool for ongoing and future CLAN research. Primary HTM cells have limited passage numbers and their CLANs vary in number, location, and morphology, making it difficult to generate consistently reproducible data across research groups/treatments/donors. In contrast, the GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells formed consistent perinuclear CLANs across various passages and after freeze-thaw cycles.

We also think that there are several key questions of CLANs that need further investigations.

1. The Etiology of CLANs

We believe that these CLANs could be due to:

A). LifeAct-GFP.

LifeAct is a small 17 amino acid peptide (Riedl et al., 2008). Studies showed that LifeAct has less impact on actin dynamics compared to actin-GFP (Riedl et al., 2008). However, it may still interfere with actin cytoskeleton and therefore promote CLAN formation. We believe that LifeAct-GFP induction of CLANs is less likely. Since these cells were selected by antibiotics, almost all cells expressed LifeAct-GFP. If LifeAct-GFP were the cause of CLANs, we would have observed a much higher rate of CLAN positive cells in our cultures instead of in <0.1% of the cells. Also, our AFM data showed that LifeAct-GFP did not affect cell stiffness.

B). Lentiviral insertion.

Lentiviruses are retroviruses that insert their genome into the host genome. The insertional sites are not entirely random: lentiviruses prefer to insert at open chromatin regions of the genome such as the promoters. Studies including clinical trials using lentiviral vectors as therapeutic approaches showed insertional events could lead to gene expression changes or even unexpected tumors (Cavazzana-Calvo et al., 2010; Fraietta et al., 2018; Wu and Dunbar, 2011). We hence hypothesize that only a certain insertion pattern will lead to CLAN formation.

It is important to note that our cells were constructed by pooling all antibiotic resistant cells, these TM cells are a mixture of different clones. The CLAN forming cells could be 1) a mixture of several monoclonal CLAN forming cells; 2) a single monoclonal cell population mixed with other non-CLAN forming cells; or 3) a combination of 1) and 2). Identifying the lineage responsible for forming CLANs is beyond the scope of this study. Furthermore, it is possible that CLAN+ cells may exhibit suppressed cell proliferation. If our hypothesis is true, then CLAN− cells grow much faster than CLAN+ cells, which will in turn result in disproportionately fewer CLAN+ cells.

Also, we found that TGFβ2 an DEX did not induce CLAN formation in these cells, which is very different from pHTM cells. In contrast, DEX decreased CLAN formation in these cells. These findings indicate that the formation of CLANs in these cells is likely genetically driven (see discussion previously).

Our future studies will focus on the enrichment of CLAN forming cells and comparing the lentiviral insertional sites of CLAN+ cells to those of CLAN− cells. This comparison may reveal a panel of genes that play a key role in CLAN formation. Such a controlled study would help to identify genomic insertion sites that regulate actin restructuring that may further be studied using primary cells or ex vivo models.

2. Mechanical characterization of CLAN+ cells

Our elastic modulus data showed for the first time that CLANs make TM cells stiffer. Interestingly, the factor of viscosity in CLAN+ cells was significantly decreased suggesting a shift in the balance of intracellular elastic and viscous components. This decrease in hysteresis was surprising since the CLANs formed by reconstitution in vitro are thought to exhibit more viscoelastic behavior than elastic due to their interconnectivity (Schmoller et al., 2009; Unterberger et al., 2013a; Unterberger et al., 2013b). A recent study demonstrated that cellular control of cytosolic viscosity is partially effected through production of polysaccharides (glycogen) and sugar (trehalose) in response to extracellular stressors (Persson et al., 2020). Glycogenin (a primer for glycogen synthesis) and glycogen synthase have been shown to bind to actin and/or translocate to the cellular cortex, both of which could in turn influence indentation outcomes (Baqué et al., 1997; Fernández-Novell et al., 1997) . Whether the changes observed in this study were a result of actin alone or secondary to changes of other cytoskeletal components and/or plasma membrane tension is not clear. Additional studies focusing on indentation/loading rates, indentation depth, differential creep deformation or stress relaxation responses to varying holding forces or strain, and traction forces generated by CLAN+ vs CLAN− cells will be required to further understand the implications of CLANs on cellular elasticity, viscoelasticity, and contractility. Importantly, this cell stiffening was a consistent observation whether it was in GTM3-LifeAct-GFP cells with spontaneous CLANs or pHTM cells with induced CLANs. Understanding the implication for such a stiffening and their occurrence over the nucleus would help further our understanding the role of CLANs in disease etiology and progression.

3. Biological characterization of CLAN+ cells

We showed that CLANs affected TM biology including resistance to latrunculin B and decreased phagocytosis in CLAN+ cells. Based on these findings, together with mechanical changes caused by CLANs, we believe that persistence of or increased presence of CLANs and CLAN+ cells in situ may contribute to elevated outflow resistance and result in OHT. Whether this resistance may be attributed to reduced deformability, reduced TM cells, and/or increased contractility/traction force generated on the extracellular microenvironment remains unclear and requires more studies. Also, this is the first report, to our best knowledge, that has shown a direct link between CLANs and impairment of phagocytosis. While this phenotypic observation is exciting, the mechanism needs further investigation. Since phagocytosis involves the sorting and redistribution of many proteins and remodeling of cell membrane which require actin cytoskeleton, CLANs could affect these processes due to their unique and less dynamic structures.

There are many other important functions of TM cells including ECM remodeling, production of signaling molecules etc. We believe that CLANs will affect these key features as well, and further investigations are needed. Since we are now able to identify individual live cells with CLANs, studying the effect of CLANs at the single cell level (e.g. localized degradation of matrix, contractility, etc) will be possible and will provide insightful information.

4. The percentage of CLAN positive cells required for IOP elevation.

Not all TM cells form CLANs and therefore the determination of this critical threshold is important. With the advancement of in vitro 3D culture systems, it is now possible to mix CLAN forming and non-forming TM cells at different ratios to answer this question. Prior to doing this, the tool that we’ve generated in this study will allow us to answer if cells are able to form CLANs in a 3D environment independent of 2D substratum mediated integrin activation as suggested by Peters et al.(Filla et al., 2011; Filla et al., 2009; Filla et al., 2006).

5. Resistance to rho kinase inhibitors.

We found that CLANs were resistant to latrunculin B. Our findings may help to explain why some glaucoma patients are resistant to ocular hypotensive drugs such as Rho kinase inhibitors which also relax actin cytoskeleton. Interestingly, not all CLANs showed the same level of resistance to latrunculin B. Rho kinase inhibitors are FDA approved for glaucoma patients. We will determine if CLANs respond similarly to these compounds.

6. Memory effect.

In the cells that we studied, the cells that formed CLANs seemed to be able to reform CLANs once latrunculin B was removed. It will be important to know if all CLAN forming cells have this memory effect and if it is mediated by substratum properties (stiffness, topography, or stretch). Also, we cultured the cells in their own conditioned medium after washout of treatment. It will be interesting to find out if unconditioned medium will interfere with this memory effect.

7. Are CLANs a friend or foe to the TM?

Our current data suggest that CLANs have an unfavorable impact on TM cells. CLANs may adversely affect TM functionality by blocking or slowing down intracellular intercompartment trafficking of organelles / proteins, or other biological processes (foe). However, CLANs could be a defensive mechanism against increased shear stress and/or stretch caused by high IOP. The mechanical or biological stress could reshape TM cells to preserve themselves by forming a protective shell (CLANs) around the nucleus (friend). Increasing evidence in mechanobiology implicates that changes in cell/nuclear shape and volume contribute to chromatin reorganization and gene expressions (Katiyar et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2015; Skinner and Johnson, 2017; Stephens et al., 2019; Versaevel et al., 2012). Thus, studies focusing on morphometric dynamics of cells with/without CLANs coupled with nuclear changes would be critical in studying their functional implications. We believe that if the stress is relieved and CLANs are removed, the TM cells could be restored to their original status. However, if CLANs are resolved while the stress still exists, it may be deleterious. Many studies need to be conducted to test these hypotheses, and the development of this spontaneous CLAN forming cell strain paves the path for such investigations.

In summary, we constructed transgenic, transformed TM cells that enables the live imaging of CLANs. We believe that these cells will be a useful tool to further investigate CLANs in TM cell research.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Stable transgenic trabecular meshwork cells with spontaneous CLAN formation

CLANs make TM cells stiffer

CLANs stabilize TM actin microfilaments

CLANs inhibit TM cell phagocytosis

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the National Institute of Health/National Eye Institute Award Numbers R01EY026962 (WM), R01EY031700 (WM), R01EY026048 (VKR), and P30EY007551 (NEI core grant to UHCO), Indiana University School of Medicine Showalter Scholarship (WM), the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute funded, in part by Award Number UL1TR002529 from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Sciences Award (WM), and a challenge grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (Department of Ophthalmology, Indiana University School of Medicine). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The pLenti-Lifeact-EGFP-BlastR vector was a kind gift from Dr. Ghassan Mouneimne. The GTM3 cell line was a kind gift from Dr. Abbot Clark at University of North Texas Health Science Center and Alcon Research Laboratory (Fort Worth, TX).

Abbreviations

- AFM

atomic force microscopy

- CLANs

cross-linked actin networks

- DEX

dexamethasone

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- IOP

intraocular pressure

- OHT

ocular hypertension

- pHTM

primary human trabecular meshwork

- TM

trabecular meshwork

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- 2000. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration.The AGIS Investigators. Am J Ophthalmol 130, 429–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baqué S, Guinovart JJ, Ferrer JC, 1997. Glycogenin, the primer of glycogen synthesis, binds to actin. FEBS Letters 417, 355–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez JY, Montecchi-Palmer M, Mao W, Clark AF, 2017. Cross-linked actin networks (CLANs) in glaucoma. Exp Eye Res 159, 16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez JYWH, Patel GC, Yan LJ, Clark AF, Mao W, 2016. Two-dimensional differential in-gel electrophoresis (2D-DIGE) reveals proteins associated with cross-linked actin networks in human trabecular meshwork cells. J Clin Exp Ophthalmol 7. [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe BJ, Sebastian KS, Adams MJ, 1994. The effect of indenter geometry on the elastic response to indentation. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 27, 1156–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Cavazzana-Calvo M, Payen E, Negre O, Wang G, Hehir K, Fusil F, Down J, Denaro M, Brady T, Westerman K, Cavallesco R, Gillet-Legrand B, Caccavelli L, Sgarra R, Maouche-Chrétien R, Bernaudin R, Girot R, Dorazio R, Mulder GJ, Polack A, Bank A, Soulier J, Larghero J, Kabbara N, Dalle B, Gourmel B, Socié G, Chrétien S, Cartier N, Aubourg P, Fischer A, Cornetta K, Galacteros F, Beuzard Y, Gluckman E, Bushman B, Hacein-Bey Abina S, 2010. Transfusion independence and HMGA2 activation after gene therapy of human β-thalassemia . . Nature 467, 318–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AF, Miggans ST, Wilson K, Browder S, McCartney MD, 1995a. Cytoskeletal changes in cultured human glaucoma trabecular meshwork cells. J Glaucoma 4, 183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AF, Wilson K, de Kater AW, Allingham RR, McCartney MD, 1995b. Dexamethasone-induced ocular hypertension in perfusion-cultured human eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 36, 478–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AF, Wilson K, McCartney MD, Miggans ST, Kunkle M, Howe W, 1994. Glucocorticoid-induced formation of cross-linked actin networks in cultured human trabecular meshwork cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 35, 281–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AF, Wordinger RJ, 2009. The role of steroids in outflow resistance. Exp Eye Res 88, 752–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Novell JM, Bellido D, Vilaró S, Guinovart JJ, 1997. Glucose induces the translocation of glycogen synthase to the cell cortex in rat hepatocytes. Biochemical Journal 321, 227–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filla MS, Schwinn MK, Nosie AK, Clark RW, Peters DM, 2011. Dexamethasone-associated cross-linked actin network formation in human trabecular meshwork cells involves beta3 integrin signaling. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52, 2952–2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filla MS, Schwinn MK, Sheibani N, Kaufman PL, Peters DM, 2009. Regulation of cross-linked actin network (CLAN) formation in human trabecular meshwork (HTM) cells by convergence of distinct beta1 and beta3 integrin pathways. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 50, 5723–5731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filla MS, Woods A, Kaufman PL, Peters DM, 2006. Beta1 and beta3 integrins cooperate to induce syndecan-4-containing cross-linked actin networks in human trabecular meshwork cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47, 1956–1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraietta JA, Nobles CL, Sammons MA, Lundh S, Carty SA, Reich TJ, Cogdill AP, Morrissette JJD, DeNizio JE, Reddy S, Hwang Y, Gohil M, Kulikovskaya I, Nazimuddin F, Gupta M, Chen F, Everett JK, Alexander KA, Lin-Shiao E, Gee MH, Liu X, Young RM, Ambrose D, Wang Y, Xu J, Jordan MS, Marcucci KT, Levine BL, Garcia KC, Zhao Y, Kalos M, Porter DL, Kohli RM, Lacey SF, Berger SL, Bushman FD, June CH, Melenhorst JJ, 2018. Disruption of TET2 promotes the therapeutic efficacy of CD19-targeted T cells. Nature 558, 307–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto T, Inoue T, Inoue-Mochita M, Tanihara H, 2016. Live cell imaging of actin dynamics in dexamethasone-treated porcine trabecular meshwork cells. Exp Eye Res 145, 393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoare M-J, Grierson I, Brotchie D, Pollock N, Cracknell K, Clark AF, 2009a. Cross-Linked Actin Networks (CLANs) in the Trabecular Meshwork of the Normal and Glaucomatous Human Eye In Situ. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 50, 1255–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoare MJ, Grierson I, Brotchie D, Pollock N, Cracknell K, Clark AF, 2009b. Cross-linked actin networks (CLANs) in the trabecular meshwork of the normal and glaucomatous human eye in situ. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 50, 1255–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Lu C, Tang M, Yang Z, Jia W, Ma Y, Jia P, Pei D, Wang H, 2018. Nanotoxicity of Silver Nanoparticles on HEK293T Cells: A Combined Study Using Biomechanical and Biological Techniques. ACS Omega 3, 6770–6778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katiyar A, Tocco VJ, Li Y, Aggarwal V, Tamashunas AC, Dickinson RB, Lele TP, 2019. Nuclear size changes caused by local motion of cell boundaries unfold the nuclear lamina and dilate chromatin and intranuclear bodies. Soft Matter 15, 9310–9317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller KE, Bhattacharya SK, Borras T, Brunner TM, Chansangpetch S, Clark AF, Dismuke WM, Du Y, Elliott MH, Ethier CR, Faralli JA, Freddo TF, Fuchshofer R, Giovingo M, Gong H, Gonzalez P, Huang A, Johnstone MA, Kaufman PL, Kelley MJ, Knepper PA, Kopczynski CC, Kuchtey JG, Kuchtey RW, Kuehn MH, Lieberman RL, Lin SC, Liton P, Liu Y, Lutjen-Drecoll E, Mao W, Masis-Solano M, McDonnell F, McDowell CM, Overby DR, Pattabiraman PP, Raghunathan VK, Rao PV, Rhee DJ, Chowdhury UR, Russell P, Samples JR, Schwartz D, Stubbs EB, Tamm ER, Tan JC, Toris CB, Torrejon KY, Vranka JA, Wirtz MK, Yorio T, Zhang J, Zode GS, Fautsch MP, Peters DM, Acott TS, Stamer WD, 2018. Consensus recommendations for trabecular meshwork cell isolation, characterization and culture. Exp Eye Res 171, 164–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller KE, Kopczynski C, 2020. Effects of Netarsudil on Actin-Driven Cellular Functions in Normal and Glaucomatous Trabecular Meshwork Cells: A Live Imaging Study. J Clin Med 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D-H, Li B, Si F, Phillip JM, Wirtz D, Sun SX, 2015. Volume regulation and shape bifurcation in the cell nucleus. Journal of cell science 128, 3375–3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao W, Liu Y, Wordinger RJ, Clark AF, 2013. A magnetic bead-based method for mouse trabecular meshwork cell isolation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54, 3600–3606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montecchi-Palmer M, Bermudez JY, Webber HC, Patel GC, Clark AF, Mao W, 2017a. TGFbeta2 Induces the Formation of Cross-Linked Actin Networks (CLANs) in Human Trabecular Meshwork Cells Through the Smad and Non-Smad Dependent Pathways. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 58, 1288–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montecchi-Palmer M, Bermudez JY, Webber HC, Patel GC, Clark AF, Mao W, 2017b. TGFβ2 Induces the Formation of Cross-Linked Actin Networks (CLANs) in Human Trabecular Meshwork Cells Through the Smad and Non-Smad Dependent Pathways. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 58, 1288–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan JT, Wood JA, Walker NJ, Raghunathan VK, Borjesson DL, Murphy CJ, Russell P, 2014. Human trabecular meshwork cells exhibit several characteristics of, but are distinct from, adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther 30, 254–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy KC, Morgan JT, Wood JA, Sadeli A, Murphy CJ, Russell P, 2014. The formation of cortical actin arrays in human trabecular meshwork cells in response to cytoskeletal disruption. Exp. Cell Res 328, 164–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly S, Pollock N, Currie L, Paraoan L, Clark AF, Grierson I, 2011. Inducers of cross-linked actin networks in trabecular meshwork cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52, 7316–7324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Rodriguez M, Parker SS, Adams DG, Westerling T, Puleo JI, Watson AW, Hill SM, Noon M, Gaudin R, Aaron J, Tong D, Roe DJ, Knudsen B, Mouneimne G, 2018. The actin cytoskeletal architecture of estrogen receptor positive breast cancer cells suppresses invasion. Nat Commun 9, 2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang IH, Shade DL, Clark AF, Steely HT, DeSantis L, 1994. Preliminary characterization of a transformed cell strain derived from human trabecular meshwork. Curr Eye Res 13, 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel GC, Phan TN, Maddineni P, Kasetti RB, Millar JC, Clark AF, Zode GS, 2017. Dexamethasone-Induced Ocular Hypertension in Mice: Effects of Myocilin and Route of Administration. Am J Pathol 187, 713–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson LB, Ambati VS, Brandman O, 2020. Cellular Control of Viscosity Counters Changes in Temperature and Energy Availability. Cell 183, 1572–1585.e1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedl J, Crevenna AH, Kessenbrock K, Yu JH, Neukirchen D, Bista M, Bradke F, Jenne D, Holak TA, Werb Z, Sixt M, Wedlich-Soldner R, 2008. Lifeact: a versatile marker to visualize F-actin. Nat Methods 5, 605–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabanay I, Tian B, Gabelt BT, Geiger B, Kaufman PL, 2006. Latrunculin B effects on trabecular meshwork and corneal endothelial morphology in monkeys. Exp Eye Res 82, 236–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmoller KM, Lieleg O, Bausch AR, 2009. Structural and Viscoelastic Properties of Actin/Filamin Networks: Cross-Linked versus Bundled Networks. Biophysical Journal 97, 83–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard AR, Millar JC, Pang IH, Jacobson N, Wang WH, Clark AF, 2010. Adenoviral gene transfer of active human transforming growth factor-{beta}2 elevates intraocular pressure and reduces outflow facility in rodent eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 51, 2067–2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BM, Johnson EEP, 2017. Nuclear morphologies: their diversity and functional relevance. Chromosoma 126, 195–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamer WD, Clark AF, 2017. The many faces of the trabecular meshwork cell. Exp Eye Res 158, 112–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens AD, Banigan EJ, Marko JF, 2019. Chromatin's physical properties shape the nucleus and its functions. Current opinion in cell biology 58, 76–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugali CK, Rayana NP, Dai J, Peng M, Harris SL, Webber HC, Liu S, Dixon SG, Parekh PH, Martin EA, Cantor LB, Fellman RL, Godfrey DG, Butler MR, Emanuel ME, Grover DS, Smith OU, Clark AF, Raghunathan VK, Mao W, 2021. The Canonical Wnt Signaling Pathway Inhibits the Glucocorticoid Receptor Signaling Pathway in the Trabecular Meshwork. Am J Pathol 191, 1020–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unterberger MJ, Schmoller KM, Bausch AR, Holzapfel GA, 2013a. A new approach to model cross-linked actin networks: multi-scale continuum formulation and computational analysis. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 22, 95–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unterberger MJ, Schmoller KM, Wurm C, Bausch AR, Holzapfel GA, 2013b. Viscoelasticity of cross-linked actin networks: Experimental tests, mechanical modeling and finite-element analysis. Acta Biomaterialia 9, 7343–7353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versaevel M, Grevesse T, Gabriele S, 2012. Spatial coordination between cell and nuclear shape within micropatterned endothelial cells. Nature Communications 3, 671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade NC, Grierson I, O'Reilly S, Hoare MJ, Cracknell KP, Paraoan LI, Brotchie D, Clark AF, 2009. Cross-linked actin networks (CLANs) in bovine trabecular meshwork cells. Exp Eye Res 89, 648–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K, McCartney MD, Miggans ST, Clark AF, 1993. Dexamethasone induced ultrastructural changes in cultured human trabecular meshwork cells. Curr Eye Res 12, 783–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wordinger RJ, Sharma T, Clark AF, 2014. The role of TGF-beta2 and bone morphogenetic proteins in the trabecular meshwork and glaucoma. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 30, 154–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Dunbar CE, 2011. Stem cell gene therapy: the risks of insertional mutagenesis and approaches to minimize genotoxicity. . Frontiers of Medicine 5, 356–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Ognibene CM, Clark AF, Yorio T, 2007. Dexamethasone inhibition of trabecular meshwork cell phagocytosis and its modulation by glucocorticoid receptor beta. Exp Eye Res 84, 275–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.