Abstract

Purpose

A phase I study was conducted to investigate the safety, tolerability, and immunological responses to vaccination with a combination of telomerase-derived peptides GV1001 (hTERT: 611–626) and p540 (hTERT: 540–548) using granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) or tuberculin as adjuvant in patients with cutaneous melanoma.

Experimental design

Ten patients with melanoma stages UICC IIb-IV were vaccinated 8 times intradermally with either 60 or 300 nmole of GV1001 and p540 peptide using GM-CSF as adjuvant. A second group of patients received only 300 nmole GV1001 in combination with tuberculin PPD23 injections. HLA typing was not used as an inclusion criterion. Peptide-specific immune responses were measured by delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) reactions, in vitro T cell proliferation assays, and cytotoxicity (51-Chromium release) assays for a selected number of clones subsequently generated.

Results

Vaccination was well tolerated in all patients. Peptide-specific immune response measured by DTH reactions and in vitro response could be induced in a dose-dependent fashion in 7 of 10 patients. Cloned T cells from the vaccinated patients showed proliferative responses against both vaccine peptides GV1001 and p540. Furthermore, T cell clones were able to specifically lyse p540-pulsed T2 target cells and various pulsed and unpulsed tumor cell lines.

Conclusion

These results demonstrate that immunity to hTERT can be generated safely and effectively in patients with advanced melanoma and therefore encourage further trials.

Keywords: hTERT, Telomerase, Melanoma, Cytotoxic T cells, Vaccination, Immunotherapy

Introduction

Cutaneous melanoma is associated with a substantial mortality rate and its incidence has increased significantly over the last decades [1]. Recurrence of melanoma even after apparent complete surgical removal is frequent and implies early existence of systemic micrometastases [2]. The concept of postsurgical treatment aims at eradication of such residual foci of disease. One strategy for such treatment of melanoma is to stimulate the immune system with immunogenic tumor antigens. Vaccination with mutated oncogenic proteins has repeatedly proven successful in inducing a specific immune response in patients with malignancies including melanoma [3, 4]. This has also been demonstrated in vaccination studies using melanocyte-specific antigens in combination with various adjuvants [5–7]. Although many studies have suggested a more favorable course of the disease in patients with positive immunological responses [8, 9] other trials were unable to demonstrate a clinical benefit despite positive immune responses to the vaccines [10]. Most tumor-associated antigens described so far are expressed only in one or few tumor types. The reverse transcriptase subunit of human telomerase (hTERT), however, is a tumor-associated antigen expressed in almost all tumors. Its expression correlates well with telomerase activity: by reexpressing hTERT, tumor cells escape cellular senescence to become immortal. hTERT, therefore, constitutes a uniquely attractive target candidate for cancer vaccines.

In several previous studies with patients suffering from advanced adenocarcinoma of the pancreas [11], non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [12] or breast cancer [13] immune responses against hTERT peptides were readily induced and well tolerated. In all these studies, a significant association between immune responses and survival time was observed. In contrast, a recent study using hTERT peptide in combination with cyclophosphamide to vaccinate patients with hepatocellular carcinoma failed to induce immune responses against the peptide and also failed to demonstrate antitumor efficacy [14].

GV1001 is a unique peptide corresponding to a sequence of hTERT derived from its active site. It contains the sequence hTERT (611–626) and is capable of binding to molecules encoded by multiple alleles of all 3 loci of HLA class II. GV1001 can be further processed into cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes. p540 (hTERT: 540–548) is a high-affinity CTL epitope identical to the previously identified HLA-A2-restricted I540 peptide [7].

The combination of intradermally applied peptide epitopes together with granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) has been reported to enhance efficient T cell responsiveness also against melanoma-associated peptides in melanoma patients [3]. This adjuvant effect of GM-CSF is related to the maturation and activation of dendritic cells, which after antigen uptake will activate effector cells [15]. Based on earlier successful trials with other cancer vaccines [3], the aim of combining the two hTERT peptides was to generate both CD4+ and CD8+ tumor-reactive T cells. The primary objectives of this trial were to determine the safety and tolerability of the hTERT peptides while applying increasing doses of GV1001 and p540. The secondary objective was to assess the immunological responses of such a dual-peptide vaccine in patients with advanced melanoma. In addition, the protocol was amended to assess whether tuberculin could replace GM-CSF as adjuvant for intradermal peptide vaccination. Here, we report the successful induction of antigen-specific immune responses after vaccination of melanoma patients with intradermal hTERT peptides in combination with GM-CSF. A vaccination regimen using tuberculin PPD23, in contrast, did not lead to measurable immune responses.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

During the time period August 2001–August 2002, the first ten patients were enrolled (patients #1–#10), and between October 2003 and April 2004 the second group of patients were enrolled (patients #11–#16), a total of 16 patients with histologically confirmed melanoma. The clinicopathological variables of the first and second group of patients are summarized in Table 1. The patients were in different disease stages, at least stage IB according to UICC/AJCC 2002 classification. All patients, also the 7 patients with distant metastases, were free of clinical signs of disease at study entry and no patient showed disease progression under vaccination. The Karnofsky performance status of all patients was 80 or higher. Only patients of 18 years or more, for whom at that time standard therapy of interferon or chemotherapy had previously been evaluated were included. HLA typing was not used as an inclusion criterion since the vaccine peptides are postulated to be promiscuous (see below and [12]). Patients with significant lung, heart or infectious diseases as well as patients testing positive for hepatitis virus or HIV were excluded. Further exclusion criteria were: elevated blood values for transaminases and creatinine, chemotherapy or radiation therapy within 4 weeks prior to vaccination, the concomitant treatment with medication possibly affecting immunocompetence (i.e., systemic corticosteroids) as well as pregnancy, breast-feeding or insufficient contraception for fertile patients. Recruitment of patients in the first group started 29.8.01 and ended 28.8.02. Patients in the second group, where tuberculin was used as adjuvant, were recruited between 31.10.2003 and 19.04.2004.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics, T cell response, and survival time: (A) Two peptides (p540 and GV1001) and GM-CSF group, (B) One peptide (GV1001) and PPD23 group

| Pat.# (sex/age) | Stage (AJCC) | Peptide dosage | Injection site | DTH | Proliferation assay [SI] | Cytotoxicity assay | Survival (months) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GV1001 + p540 | w6, GV1001 | w10, GV 1001 | w6, p540 | w 10, p540 | p540 | GV1001 | HLA-A02 | |||||

| (A) Two peptides and GM-CSF group | ||||||||||||

| 1 (M/62) | IV | LD | Thigh | Pos | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.2 | Neg | ND | Pos | 37 |

| 2 (M/66) | IV | LD | Thigh | Neg | 1.0 | ND | 0.85 | ND | Neg | ND | ND | 11 |

| 3 (M/56) | IIIB | LD | Thigh | Neg | 1.1 | 1.9 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 64 |

| 4 (M/53) | IV | HD | Thigh | Pos | 3.4 | 2.6 | 1.34 | 1.3 | 63%, w10 | Pos | Pos | 44 |

| 5 (F/51) | IIIB | HD | Arm | Neg | 1.2 | 1.8 | 0.93 | 1.2 | ND | ND | ND | 52 |

| 6 (F/40) | IV | HD | Arm | Neg | 2.1 | 2.2 | 0.81 | 0.9 | ND | Pos | ND | 44 |

| 7 (M/67) | IIB | HD | Arm | Neg | 3.0 | 9.2 | 1.34 | 5.0 | 39% | ND | Pos | >90 |

| 8 (M/45) | IV | HD | Thigh | Pos | 2.7 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 0.9 | ND | Neg | ND | 6 |

| 9 (M/74) | IIIA | HD | Thigh | Neg | 26.2 | 2.6 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 18% | Pos | Neg | 8 |

| 10 (M/58) | IIIB | HD | Thigh | Neg | 3.3 | 2.5 | 0.62 | 0.9 | ND | Neg | Pos | 40 |

| Pat.# (sex/age) | Stage (AJCC) | Strategy | Injection site | DTH | DTH | Proliferation assay | Survival (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPD23 | GV1001 | GV1001 | |||||

| B: One peptide and PPD23 group | |||||||

| 11 (F/34) | IB | PPD → hTERT | Thigh | Pos | Neg | Neg | >90 |

| 12 (F/60) | IIIA | PPD → hTERT | Thigh | Pos | Neg | Neg | >90 |

| PPD + hTERT | Thigh | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||

| 13 (F/32) | IV | PPD + hTERT | Thigh | Pos | Neg | Neg | 16 |

| 14 (M/58) | IV | PPD + hTERT | Thigh | Pos | Neg | ND | 11 |

| 15 (F/53) | IIIA | PPD + hTERT | Thigh | Pos | Neg | ND | >90 |

| 16 (M/43) | IIIB | PPD + hTERT | Thigh | Pos | Neg | ND | 27 |

pos erythema and infiltration > 5 mm, neg erythema and infiltration < 5 mm, PPD → hTERT Tuberculin PPD23 was injected 2 days prior to hTERT peptide, PPD + hTERT Tuberculin PPD23 was injected together with hTERT peptide, ND not done, LD low dose, HD high dose, w6 week 6, w10 week 10, SI stimulation index (cpm with antigen/cpm without antigen) was determined after 2 cycles of in vitro stimulation with APCs and antigen as described in “Materials and methods”. An SI of more than 2.0 was considered positive. Survival time is reported in months from beginning of the vaccination

Vaccine and control peptides

The telomerase peptide vaccines GV1001 (also called p611) and p540 were provided by GemVax AS, Porsgrunn, Norway. The vaccine GV1001 consists of a synthetic peptide corresponding to the 16 amino acid residue 611–626 fragments (EARPALLTSRLRFIPK) of the hTERT protein. The vaccine p540 consists of a synthetic peptide corresponding to the 9 amino acid residue 540–548 fragments (ILAKFLHWL) of the hTERT protein. p540 is a well-known HLA-A2 epitope [12, 16], but predictions (http://syfpeithi.de) and own data (unpublished) indicate that this peptide also may be presented by many other HLA class I molecules. Both peptides were produced by Avecia Biotechnology (Cheshire, England). The finished products, GV1001 and p540 were manufactured by Isopharma AS (Kjeller, Norway), supplied in vials as freeze-dried products, and released for clinical use by GemVax AS (Porsgrunn, Norway). Manufacturing was in compliance with GMP. Two peptides, one derived from telomerase, Pep 544 (hTERT 548–566), and one derived from mutant p21 RAS, Pep 508; (KRAS 52–70, Q61H), served as negative controls in the T cell proliferation assays were used to monitor T cell responses in blood samples from the vaccinated patients. The control peptides were supplied as lyophilized powder by The Corporate Research Center Norsk Hydro (Porsgrunn, Norway). Prior to patient administration the peptides were dissolved in sterile saline to achieve the dilution required.

Recombinant hTERT

Recombinant hTERT (563–735) was cloned in frame with the N-terminal 6x His tag in E. coli expression vector pET28b(+) (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany). The protein was produced in E. coli BL21 Codon Plus (DE3)-RIPL (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA), purified by using NiNTA chromatography under denaturing conditions (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and tested by Western blot analysis with anti-His antibodies (Qiagen) and Rabbit Anti-Mouse Ig HRP (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). The fraction of interest was dialyzed in Slide-A-Lyzer® Dialysis Casette 10,000 MWCO (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) against MQ-water and sterile-filtered before use.

Vaccination protocol

The treatment protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Canton of Berne, Switzerland, and studies were performed according to the principles of the Helsinki declaration. Written informed consent from all patients was obtained before inclusion into the study. Before vaccination, the following baseline studies were performed: (1) Physical examination including medical history and assessment of ECOG performance status. (2) Hematological testing for hemoglobin, hematocrit, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, white blood cell and platelet count and blood chemistry panel. (3) White blood cells were isolated and tested in vitro for general immunocompetence and pre-vaccination T cell reactivity against the vaccine peptides (methods described below).

Eligible patients (#1–#10) received 8 vaccinations, each consisting of a combination of the two hTERT peptides over a period of 10 weeks (Table 1A). The first three patients received 60 nmole (112 μg) GV1001 and 60 nmole (68.4 μg) p540. After reviewing the safety data for these three patients, the doses were adjusted such that the following seven patients received 300 nmole (560 μg) of GV1001 and 300 nmole (342 μg) of p540 per immunization. These dose levels were selected based on previous experience with the same vaccine in patients with pancreatic cancer (8). The vaccine was administered by intra-dermal (i.d.) injection on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 14, 21, 35, and 63. Between 5 and 15 min before the vaccination, i.d. injections of 30 μg recombinant human GM-CSF (Leucomax; Schering–Plough, Cork, Ireland) were given either in the proximal ventral thigh region or the proximal arm region (in patients with a history of melanoma on the lower extremities), followed by i.d. administration of hTERT peptide at the same site. This amount of GM-CSF has been chosen as it has been successfully used in former trials [4, 11, 12]. Patients in the second group (#11–#16) were immunized using PPD23 (Tuberkulin PPD RT 23, Pro Vaccine, Zug, Switzerland) as adjuvant. 0.1 ml PPD23 solution containing 2 tuberculin units (0.4 μg) was injected 2 days prior to the hTERT peptide (GV1001 only, high dose, i.e., 300 nmole (560 μg)) at the same vaccination site, or was administered together with the peptide (Table 1B). Two tuberculin units PPD23 were used as this is the recommended amount for the induction of a skin reaction. One patient (patient #12) was vaccinated with both regimens in succession. As a previous study using the same two peptides for vaccination [12] showed positive in vitro tests against p540 for only 8% of the patients, and as none of the first 10 patients in this study developed a positive DTH reaction against p540, the second set of patients was only vaccinated with the longer GV1001 peptide.

The vaccination site was marked, in order to place every vaccine precisely at the same site. Comprehensive immunological testing, assessment of adverse drug reactions, physical examination, and assessment of performance status were done at each vaccination visit. Blood screening took place in 6 of these visits. At the follow-up visit on day 77, a complete clinical screening identical to the initial workup was performed, as well as a blood screening.

Delayed-type hypersensitivity

Delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) skin tests were performed with both peptides at vaccinations 1, 4–8. Sixty nanomoles of the single peptides dissolved in saline were injected i.d. at separate sites (5–7 cm apart from each other) and contralaterally to the vaccination site. A positive skin reaction was defined as erythema and induration, average diameter ≥ 5 mm, 48 h after i.d. injection. The patients were instructed to measure the diameter of the DTH reaction and report it to the clinician, whenever a direct evaluation by the clinician was not possible. The clinician recorded the skin test as positive or negative in the clinical report form.

Cells

Prior to vaccination on each visit (except visits 2 and 3), 50 ml ACD blood was drawn to assess in vitro proliferative T cell responses against GV1001 and p540. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from peripheral blood by density-centrifugation over Ficoll–Hypaque (Lymphoprep; Nycomed, Oslo, Norway) and were washed and frozen immediately in RPMI-1640 (Gibco, Paisley, UK) with 20% FCS (PAA Laboratories GmbH, Paching, Austria) and 10% DMSO and stored at <−70°C in liquid N2. Due to high background proliferation with cells frozen in FCS, 10% human albumin was substituted for FCS during freezing of blood samples from 2002 on. All assays were done with thawed samples.

Proliferation assay

As in former studies ex vivo proliferation was not enough sensitive to demonstrate peptide-specific T cell responses [4, 11, 12], a secondary stimulation assay was used, essentially as described earlier [17]. Briefly, thawed PBMC were seeded at 2 × 106 per well in 24-well plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA) in 1 ml of X-VIVO10 (Bio–Whittacker Inc., Walkersville, MD, USA) containing 15% heat-inactivated human serum and antibiotics supplemented with GV1001 or control peptides at 25 mM concentration. After 3 days of culture, the medium was supplemented with 10 U per ml of recombinant human interleukin-2 (Amersham, Aylesbury, UK). Cultured cells were restimulated for one more cycle after 7–9 days of culture using irradiated (30 Gy) PBMC as antigen presenting cells and the same peptide concentration as above. The pre-stimulated cells were tested on days 14–18 for specific proliferating capacity against GV1001 and control peptides at 25 mM concentration, by using 5 × 104 T cells and autologous, irradiated (30 Gy) PBMCs (5 × 104 cells per well) as antigen presenting cells (APCs). After 2 days, wells were pulsed with 3.7 × 104 Bq of 3H-thymidine overnight and counted. Values are given as stimulation index (SI). SI was calculated as mean counts per minute (cpm) from triplicate wells with antigen divided by mean cpm without antigen. A SI above 2 was considered as positive.

As a measure of general immunocompetence, the T cell response to purified protein derivative (PPD) of tuberculin and staphylococcal enterotoxin C (SEC) was measured in blood samples taken at inclusion. All patients demonstrated responses within the normal range, and there was no correlation between the response to these antigens and the subsequent response to the vaccine peptides.

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity assays were performed essentially as described earlier [17], using peptide-pulsed, 51Cr-labeled tumor cells, T2 cells or EBV-transformed cells as targets. The cell lines T2 (HLA A2+, antigen processing defective), K562 (NK sensitive leukemia), LnCAP (prostate cancer), Panc-1 (pancreatic canrcinoma), LS174 (colon cancer) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, http://www.attc.org). The melanoma cell lines FM-3, FM-6, FM-60, and FM-48 were obtained from The European Searchable Tumor Line Database (ESTDAB, http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ipd/estdab/). Unless otherwise stated, the peptide concentration used for pulsing was 1 μgM. Maximum and spontaneous 51Cr release of target cells was measured after incubation with 5% Triton X-100 (Sigma) or medium, respectively. Specific cytotoxicity was calculated according to the formula: (experimental release − spontaneous release)/(maximum release − spontaneous release) × 100.

Cytokine production

Cytokine production by T cell clones was measured in supernatants taken from T cell assays 24 h after peptide stimulation, using a human 17-plex cytokine kit and the Bio–Plex instrument (BioRad Laboratories Inc., USA), as described by the manufacturer.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometric analysis was performed according to standard protocol. PE-labeled HLA-A*0201 presenting the hTERT peptide p540 or as a control the tax peptide, was provided by Proimmune (Oxford Science, Oxford, UK). Cellular staining was performed according to the manufacturer indications. PerCP-labeled anti-CD8 mAb (BD Biosciences) was used to stain CD8 T cells. Samples were analyzed on a FACScan (BD Biosciences) using CellQuest software.

T cell lines and clones

Cultures that showed a proliferative response against p540 were subsequently tested for cytotoxicity using chromium-labeled T2 cells pulsed with hTERT peptide (p540) as targets, and the PBMC from the patients were typed for HLA-A2 only. Cell lines were derived by repeated peptide stimulations and CTLs were cloned from the proliferative bulk cultures by limiting dilution using allogeneic PBMC as feeder cells and PHA as stimulator essentially as described [17]. CD4 positive clones were similarly cloned from proliferative bulk cultures responding to GV1001 using the same procedure.

Toxicity and safety

Adverse events were evaluated at each visit. The clinical investigator graded the events as probable, suspected, unlikely or not related to the treatment. Adverse events were considered related to the treatment if the relationship was reported as probable or suspected.

Results

Safety and tolerability

The vaccination with the two hTERT peptides was well tolerated in all 10 patients that received the vaccine in combination with GM-CSF as adjuvant, as well as in those 6 patients receiving only GV1001 in combination with tuberculin as adjuvant. In the GM-CSF group, occasionally, a slight swelling and erythema around the vaccination site occurred, lasting 3–5 days, thereafter resolving completely. An eczematous reaction at the vaccination site was observed in three patients, with a peak of extension and intensity approximately 48 h after injection, resolving completely within a few days. These local skin reactions were accompanied by only minor subjective discomfort and were rated as favorable local effects in terms of markers of immunological response. In the tuberculin group, an infiltration of 1–2 cm occurred in the all patients. No clinically important signs of adverse events as well as other signs of toxicity occurred. No clinical signs of auto-immune disease nor abnormal biochemical or hematological parameters related to the vaccines were observed.

Characterization of immune responses against GV1001 and p540

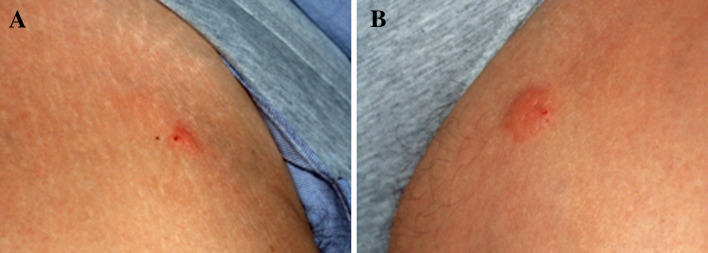

Patients with a positive DTH test or the presence of p540 or GV1001-specific T cells in peripheral blood after vaccination were considered as immune responders. An example of a positive DTH reaction is shown in Fig. 1. Table 1 summarizes immune response of all patients. In the first group of patients, vaccination was performed with the two hTERT peptides p540 and GV1001 in two different dosages (Table 1A). The first three patients were vaccinated with the hTERT peptides in low dose (60 nmole). One of these 3 patients (patient #1) showed a positive DTH reaction. In none of these patients, a peptide-specific immune response could be detected by in vitro T cell assays. Based on this observation, the dosage of both peptides was increased to 300 nmole. With this vaccination regimen, 2 of 7 patients showed a positive DTH reaction for GV1001 (patient # 4 and #9) and 6 of these 7 patients showed positive in vitro T cell immune responses. Taken together, 7 of these 10 patients showed a positive immunological response to the vaccine peptides, either as a positive DTH reaction or as positive in vitro T cell response. A strong positive response against p540 was detected by the cytotoxicity assay in patient #4 and #7 (see below), and some cytotoxicity was also observed in patient # 9.

Fig. 1.

Skin reaction in patient #8 48 h after vaccination: a mixture of both peptides GV1001 and p540 was injected intradermally on both tights, on the left side GM-CSF was injected 15 min prior to peptide-injection at the same site. Positive reactions could been induced at the DTH (a, right tight) and vaccination site (b, left tight)

In the second group of 6 patients (Table 1B), a new immunization strategy with tuberculin (PPD23) as adjuvant was applied. As the immune response to p540 was low in the first group and in a study with patients with non-small lung cancer [12], this patient group was only vaccinated with the longer hTERT peptide GV1001. Despite the fact that PPD23 was very efficient in inducing a skin inflammation (DTH) in all six patients, none of these patients showed positive in vitro T cell assays.

Detailed analysis of T cell responses to hTERT in two patients

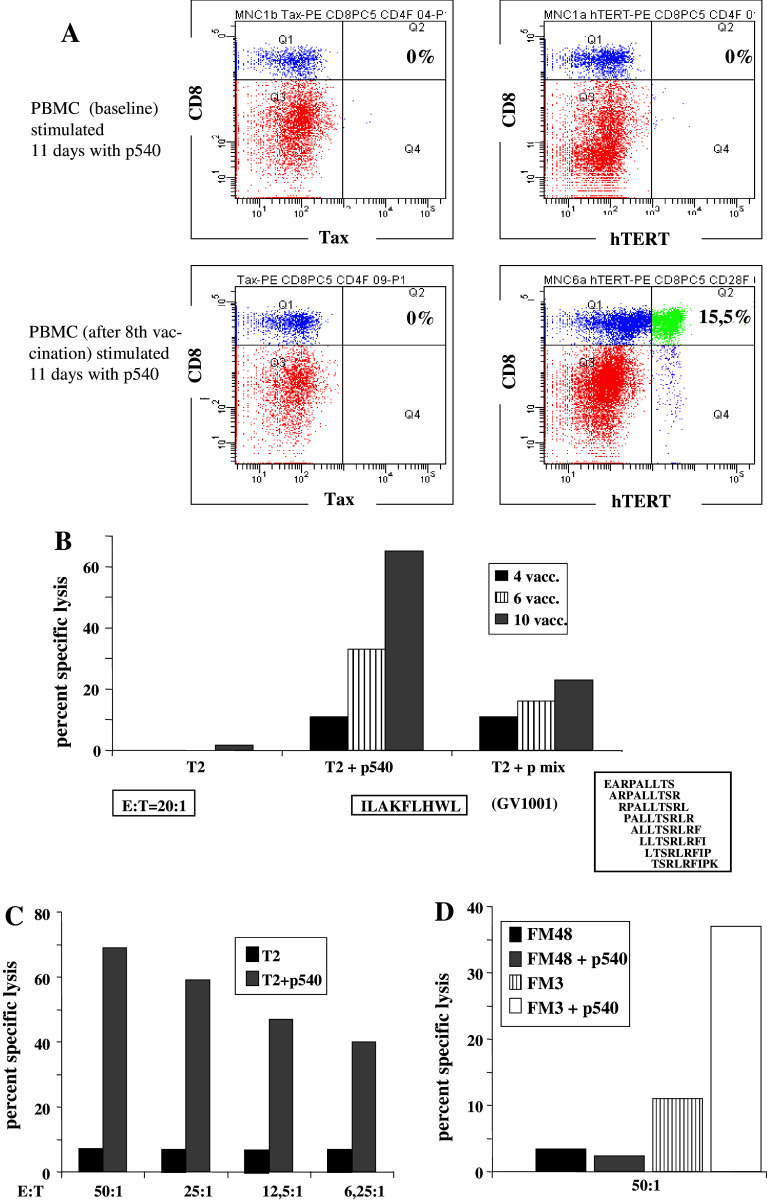

In two patients (patients #4 and #7), a more detailed analysis of T cell responses was performed. Both patients responded to GV1001 and p540 in proliferative assays. In order to study the p540 reactive cells, we produced HLA-A2 pentamers with p540. Frozen samples of cells harvested before vaccination and 6 weeks after vaccination, assayed ex vivo without prior stimulation, showed no evidence of expansion of hTERT-positive cells (data not shown). On the other hand, in vitro stimulation for 11 days with p540 revealed the presence of p540 A2 pentamer positive T cells in the blood sample harvested on week 6 after the vaccinations began (Fig. 2a). After 11 days of in vitro stimulation, 15.5% pentamer positive cells were seen in the post-vaccine sample versus 0% in the parallel culture of pre-vaccine cells, clearly demonstrating an enhanced precursor frequency following vaccination. Control experiments with HLA2/Tax pentamers showed no increase in positive cells.

Fig. 2.

Specific CTL responses against the vaccine peptides p540 and GV1001 in patient #4. a Pentamer staining of PBMCs before, i.e., at baseline, (upper panel) and after (lower panel) vaccination. The two right graphs represent staining with the HLA-A2/hTERT (p540) pentamers and the left graphs depict staining with HLA-A2/Tax pentamers (control). Cells were also stained for CD8. b Specific killing of T2 target cells pulsed either with p540 or a mixture of 8 different, overlapping nonapeptides covering the whole GV1001 amino acid sequence. Effector cells in this assay were harvested following the 4th, 6th, and 10th vaccinations and expanded by two cycles of in vitro stimulation by p540 and GV1001 peptides. Standard chromium release assay. T2 without peptide served as a negative control. c Dose–response curve for p540-specific CTL lysis by effector cells obtained from the blood sample harvested at week 6 and expanded as a cell line by additional rounds of peptide stimulation in vitro. d Cytotoxicity of the same cell line tested with p540-pulsed or unpulsed melanoma cell lines FM48 (HLA-A2 neg.) or FM3 (HLA-A2 pos.)

In order to investigate if these cells were also functionally active, we tested the capacity of bulk cultures generated from PBMC’s harvested at different time points after vaccination to kill p540-pulsed T2 cells in a conventional chromium release assay. The bulk cultures were generated by in vitro stimulation with the two vaccine peptides. Figure 2b clearly demonstrates that the cells were capable of specifically killing p540 pulsed targets. Little or no killing was seen with unpulsed T2 targets. Importantly, killing increased with repeated vaccinations indicating a boosting effect of vaccination. Interestingly, a parallel increase in intrinsic activity against T2 cells pulsed with a peptide mixture consisting of all 8 overlapping 9-mers derived from GV1001 was also observed, indicating that CTLs against one or more fragments of GV1001 were generated in parallel with generation of T helper activity. We next generated a cell line by repeated stimulation of PBMCs harvested on week 6 and tested this cell line against p540-pulsed T2 target cells and HLA A2 positive and A2 negative cell lines. The results are shown in Fig. 2c and d. The cell line efficiently killed peptide-pulsed T2 targets even at low effector/target (E/T) ratios. No killing of the HLA-A2 negative melanoma cell line FM48 was observed, neither in the absence nor presence of p540. The A2 positive melanoma cell line FM-3, pulsed with the peptide p540, was killed by the cell line. Interestingly, there was also low level killing of unpulsed FM-3 cells. These results indicated that p540 specific CTLs with the capacity to kill melanoma targets were generated during vaccination.

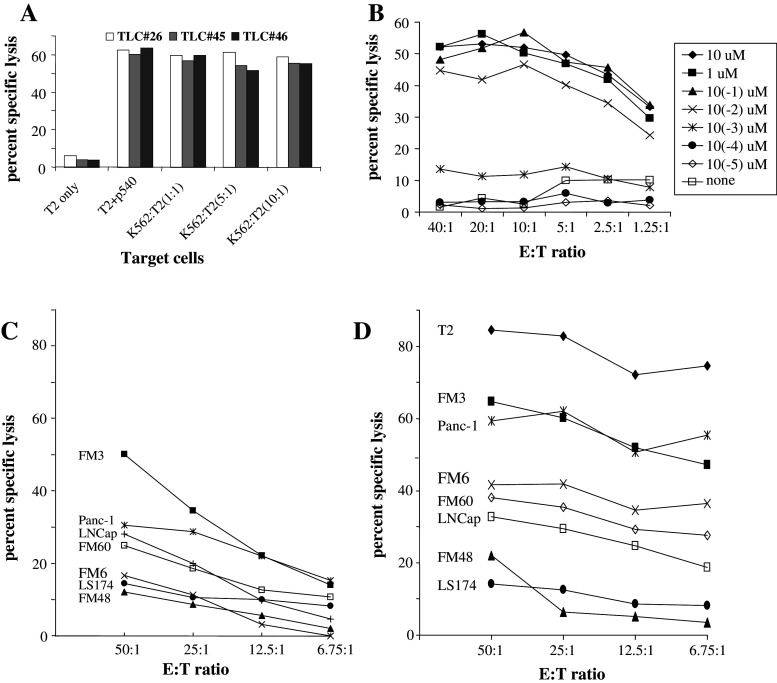

To provide further evidence for this, we generated specific T lymphocyte clones (TLCs) from the cell line by limiting dilution. Data from three of these clones are given in Fig. 3. Figure 3a shows that all TLCs efficiently killed p540-pulsed T2 targets and no killing was seen with unpulsed T2 cells. As certain T cells subsets have been described to exert natural killer (NK) cell activity [18], we incubated our TLCs with increasing numbers of K562 cells, indicating that killing was not due to NK cell activity. A representative dose–response experiment with clone #26 is shown in Fig. 3b. With doses between 10 nM and 10 μM peptide, efficient killing was seen even with very low E/T ratio’s (1.25:1). Below the 1 nM threshold, a sharp drop in cytolytic activity was observed. These results indicate that high-affinity TLCs had been generated by vaccination. We therefore wanted to investigate if the TLC #26 was able to lyse tumor cell lines without exogenous addition of peptide in a dose-dependent manner. These results are shown in Fig. 3c.

Fig. 3.

Specific killing by CTL clones from patient #4. a Specific lysis of p540-loaded T2 target cells by three CTL clones (TLC#26, 45, 46) at E/T ratio of 20:1 in the presence of increasing ratios of K562 cells (NK cell target). b Dose–response curve for a representative CTL clone (#26). T2 cells were loaded with the indicated concentrations of p540. c and d Lysis of various tumor cell lines by TLC #26 (c) without addition of exogenous peptide and d with addition of exogenous p540 peptide

TLC #26 killed the cell lines FM-3, Panc-1, LnCAP, and FM-60 in a dose-dependent fashion. Control cell lines including the HLA-A2 negative cells LS174 and FM-48, and the HLA-A2 positive cell line FM-6 showed background killing. Killing to some extent reflected the inherent telomerase enzymatic activity in the cell lines, as FM3 had very high telomerase activity in the TRAP assay (data not shown). When the same cell lines were pulsed with p540 and tested with the same E/T ratios of T cells (Fig. 3d), increased killing was seen within a broad range of E/T ratios. Furthermore, pulsed FM-6 cells were also killed, indicating that insufficient generation of endogenous peptide by processing hTERT in this cell line occurred. All cell lines were less susceptible to killing than T2 following pulsing.

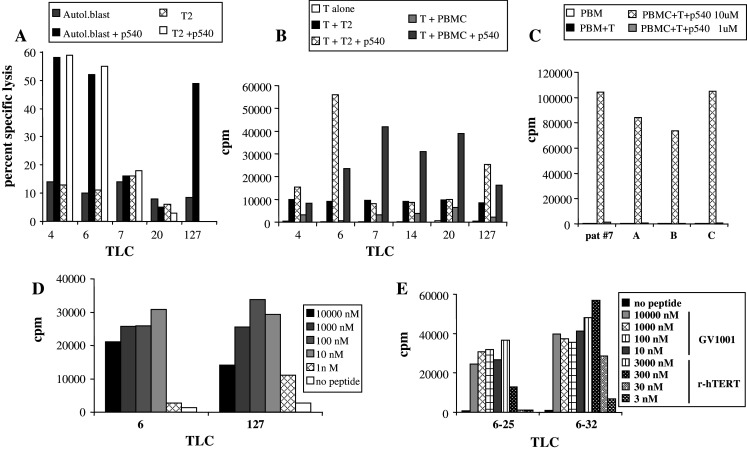

Patient #7 generated an immune response against both vaccine peptides. We generated both CD4 and CD8 T cell clones for further characterization of this patient’s T cell responses. Out of 40 T cell clones screened, 22 were vaccine peptide-specific. Of these, 20 were reactive with p540 and two with GV1001 in proliferative testing (data not shown). The p540 bias was due to removal of the majority of CD4 cells by depletion with anti-CD4 coated Dynabeads® prior to cloning. In the initial screening, PBMCs were used as antigen presenting cells (APCs) in the assay. To study the CTL activity of the p540 reactive clones, we selected some clones for peptide-pulsing studies. Three out of five clones were able to kill target cells in a cytolytic assay (Fig. 4a), but the experiment revealed some striking differences. TLCs #4, #6, and #127 efficiently killed peptide-pulsed autologous PHA blasts. In addition, clones #4 and #6 killed peptide-pulsed T2 cells. On the other hand, clones #7 and #20 which both proliferated to p540 in the initial screening were unable to kill both targets.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of CTL activity and proliferative responses of TLCs from patient #7. a Specific lysis of either unpulsed or p540-pulsed T2 cells and autologous PHA blasts. b Proliferative responses (cpm) of the indicated TLCs using T2 and PBMCs as APCs with or without peptide (p540). c Proliferative response of TLC #7 using PBMCs from different donors as APCs. The patient was HLA A2/A23 (B7/5703/C7) positive and the other donors shared A2 or A23 with the patient. d Proliferative response of TLC #6 (CD8+) and #127 (double negative) to different peptide concentrations. e Proliferative responses of 2 TLCs against recombinant hTERT and GV1001. The TLCs were incubated with APCs and the indicated concentrations of either recombinant hTERT or GV1001. cpm was measured in a standard 3-day proliferation assay used for TLCs

To try to explain this discrepancy, we went back and tested these clones and an additional clone (TLC #14 from patient #7) with peptide-pulsed T2 cells as well as autologous PBMCs as APCs in the proliferative assay. The corresponding data are shown in Fig. 4b. These results confirm that all cell lines proliferate specifically when recognizing p540-pulsed PBMCs. The two T cell clones that did not kill peptide-pulsed T2 cells failed to proliferate when confronted with T2 cells pulsed with p540. The same clones proliferated vigorously upon recognition of PBMC pulsed with p540. The same pattern was seen for TLC#14. Taken together, these experiments indicate that the three T cell clones that did not recognize p540 on T2 may recognize this peptide presented on class I molecules which are present on autologous APCs but not on T2 cells.

To address this possibility, we tested the proliferation of TLC #7 against p540-pulsed APCs from a limited panel of donors (Fig. 4c). The patient was HLA A2/A23 (B7/5703/C7) positive and the other donors shared A2 or A23 with the patient. TLC #7 responded vigorously to APCs from all donors pulsed with p540. The response was specific as no other response was observed in the absence of peptide. Moreover, the T cell clone did not present the peptide to itself, since proliferative response was absolutely dependent on PBMCs. The response against the two A2 containing pulsed PBMCs was more pronounced than the response against the A23 positive-pulsed PBMCs. Another feature which became obvious from this experiment was that high concentrations of the peptides was required, since the responses dropped abruptly to background levels when reduced from 10 to 1 μM. Taken together, these results indicate that some type of low affinity interaction between peptide and several different HLA molecules may take place, and that this is sufficient to generate a very vigorous proliferative response in this type of T cell clone. The phenotype of the T cell clones in Fig. 4b was investigated by flow cytometry. TLCs #4, #6, #7, #14, and #20 all had the conventional CTL phenotype (CD3+, CD8+, CD4−). The TLC #127 turned out to be double negative (CD3+, CD8−, CD4−). The peptide/dose response curve indicated that the affinity of this CTL clone was in the same range or even higher as that of the CD8+ clones, such as TLC #6 (Fig. 4d).

In a further step, we generated CD4+ T cell clones from patients #4 and #7. Some data are given in Fig. 4e, which depicts results with two T cell clones derived from patient #7 (#6–25 and #6–32). Both clones are CD3+, CD4+, CD8− and are HLA-DR restricted (data not shown). Both T cell clones proliferated vigorously and specifically against GV1001-pulsed APCs. Since hTERT may be processed to peptides in many different ways, and the binding motifs of different class II molecules are different, it was important to investigate if these T cell clones also were capable of recognizing hTERT fragments generated by feeding recombinant hTERT to APCs. The two HLA-DR restricted T cell clones both recognized autologous PBMCs that were pulsed with recombinant telomerase protein, strongly suggesting that natural processing of hTERT may give rise to peptide fragments, fitting into the HLA-DR molecules used for presentation to the two clones.

To characterize the T cell response further, we also investigated the cytokine production by the T cell clones. Upon stimulation with EBV-transformed autologous cells as APCs and peptide (GV1001) or CD3 and CD28, two TLC from patient #7 produced substantial amounts of IL-4, one of them also with high amounts of IL-10. All other investigated TLCs produced, however, a predominantly Th1 cytokine profile with high amounts of IFN-γ and TNF-α as well as very high amounts of GM-CSF (data not shown).

Discussion

In this study, we report the clinical testing of an anticancer vaccine based on two different telomerase-specific peptide epitopes in patients suffering from high risk melanoma. Our results confirm that hTERT peptides and GM-CSF as adjuvant is well tolerated as already described in patients with lung cancer [19], and pancreatic carcinoma [11].

A positive DTH reaction could be detected in 3 of 10 patients vaccinated with GM-CSF as adjuvant. Notably, all patients with positive DTH reaction had received their vaccination in the thigh and not in the arms, confirming earlier observations [3]. Patients suffering from pancreatic cancer vaccinated with the same regimen [11] showed a similar response rate, (36%). These results are lower than those reported in patients suffering from lung cancer given the same vaccine [19], where 59% of vaccinated patients had a positive DTH. Seven of the 10 vaccinated patients showed either a positive DTH or a positive in vitro assay. Interestingly, this ratio was higher (6 of 7) in the high dose regimen group than in the low dose group (1 of 3). It has been shown that the dosage of the peptide is crucial for the induction of a strong immune response. There seems to be an optimal dosage for GV1001 in the range of 0.5–1.0 mgs. There is evidence that higher doses result in a lower rate of positive reactions [11], indicating a bell-shaped curve. This is also observed at the clonal level (Fig. 4d) [19]. An improvement of the vaccination regimen is therefore not possible by increasing the dosage of the peptide. One strategy is to look for a better or stronger adjuvant. Incomplete Freund’s adjuvant either alone or in combination with TLR agonists have been used by different investigators [20]. In this study, we used PPD23, a protein compound of mycobacteria which induces a strong DTH reaction in BCG vaccinated patients when injected intradermally, creating a pro-inflammatory environment. Surprisingly, this adjuvant could not induce an anti-hTERT immune response, either by simultaneous injection or if injected 2 days before injection of the peptide. One may speculate that the immune response against the bacterial peptides is dominant, resulting in a suppression of the immune response against the hTERT peptide.

One intriguing result is that there is no correlation of the immune response assessed by the different assays. Although patient #1 had a positive DTH skin reaction, all in vitro assays were negative. On the other hand, patient #7 showed strong in vitro immune responses, but the DTH skin reaction was negative. This observed discrepancy between the skin tests and the in vitro tests has been observed earlier [11]. It might either reflect different sensitivities in the two assays or be a result of biologically different immune reactions being generated. Thus, a shift in cytokine production away from classical inflammatory cytokines might result in a lack of DTH reaction. The analysis of the cytokine production of our T cell clones revealed that at least some TLC produced high amounts of IL-4 or even IL-10. A difference in the balance of the different clones produced in different patients may possibly explain some of these discrepant results.

Cytotoxicity assays with p540 was positive in 3 of the 5 tested patients (Table 1). All positive tested patients were vaccinated with the higher dose of the two peptides. Interestingly, patient #9 was HLA-A02 negative providing further evidence that p540 is presented by other class I alleles that A02 as has been postulated earlier [12]. The CTL response increased with increasing number of injections of the vaccine, demonstrating a boosting effect of repeated vaccinations as has been previously shown by others [8]. This underlines the importance of the concept of multiple injections. Brunsvig and coworkers [19] could induce stable high levels of immunity over the time period of over 6 months with repeated booster injections. Remarkably, the induction of a CTL response against the HLA class I-restricted peptide p540 was paralleled by a CTL response against the cocktail of all eight possible nonapeptides of the longer GV1001 peptide. This indicates that the longer GV1001 peptide has been processed and presented on MHC class I molecules to CD8 T cells, providing indirect evidence for cross-presentation.

The efficacy of a T cell response seems to be dependent on the frequency of the T cells and the affinity of the T cell receptor [21]. The finding that the T cell responses are only detectable after 2 cycles of pre-stimulation may explain the poor clinical effect of the vaccination protocol. On the other hand, the correlation of the affinity with the effectiveness is less well documented but recent data [22] indicate that an optimal range has to be achieved to get an efficient T cell response. As shown in Fig. 3b, high-affinity T cells were detected in our in vitro experiments. It remains, however, difficult to make any conclusion about the affinity of the T cells in vivo as we only assessed few clones which might have been selected by the in vitro conditions.

Upon contact with peptide antigen, CTLs have been described to produce the Th1 cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α [23, 24]. In this study, the two investigated CTL clones from patient #7 produced high amounts of these two Th1 cytokines upon antigen-specific stimulation. In addition, both clones also produced IL-6, IL-8, and GM-CSF. Surprisingly, also the Th2-related cytokines IL-4 and IL-10 were produced. Especially IL-10 is a potent inhibitory cytokine and has been shown to be produced by regulatory T cells [25]. Such mixed cytokine profiles have been observed in T cell clones from many different patients who have been treated with cancer vaccines [8]. Since these T cell clones produce multiple cytokines with partly opposing activities, it is difficult to speculate what the overall outcome will be in vivo.

Although the number of patients included in this study is rather low, these data show that tumor-specific immune responses against hTERT peptides can easily be induced in most melanoma patients. The correlation of a strong immune response with long-term survival has been documented earlier [11, 26]. The here observed survival times (Table 1) are mainly dependent on the stage of the disease. Interestingly, the long time survivor patient #7 showed a strong in vitro immune response, but he also had compared to the other patients an early stage of the disease. Because of the small number of patients in different disease stages, it is not possible to draw conclusions about the clinical efficacy of the vaccination protocol. Controlled trials will be needed to answer this question. The fact that the immunological responses were only detectable after in vitro expansion of the T cells may indicate that the aim of further studies must focus on the search of more potent vaccination strategy. This may either be achieved by eliminating immunosuppressive mechanisms [27], enhancing the immune response by a more potent adjuvant or by continued booster vaccination as have been used in other trials [19].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Norsk Hydro and Berner Krebsliga (Bernese Cancer Society).

References

- 1.Miller AJ, Mihm MC., Jr Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:51–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curiel-Lewandrowski C, Demierre MF. Advances in specific immunotherapy of malignant melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:167–185. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.104513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gjertsen MK, Buanes T, Rosseland AR, Bakka A, Gladhaug I, Soreide O, Eriksen JA, Moller M, Baksaas I, Lothe RA, Saeterdal I, Gaudernack G. Intradermal ras peptide vaccination with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor as adjuvant: clinical and immunological responses in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:441–450. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunger RE, Brand CU, Streit M, Eriksen JA, Gjertsen MK, Saeterdal I, Braathen LR, Gaudernack G. Successful induction of immune responses against mutant ras in melanoma patients using intradermal injection of peptides and GM-CSF as adjuvant. Exp Dermatol. 2001;10:161–167. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2001.010003161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lienard D, Rimoldi D, Marchand M, Dietrich PY, van Baren N, Geldhof C, Batard P, Guillaume P, Ayyoub M, Pittet MJ, Zippelius A, Fleischhauer K, Lejeune F, Cerottini JC, Romero P, Speiser DE. Ex vivo detectable activation of Melan-A-specific T cells correlating with inflammatory skin reactions in melanoma patients vaccinated with peptides in IFA. Cancer Immun. 2004;4:4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson AC, Harlin H, Gajewski TF. Immunization with Melan-A peptide-pulsed peripheral blood mononuclear cells plus recombinant human interleukin-12 induces clinical activity and T cell responses in advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2342–2348. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slingluff CL, Jr, Petroni GR, Yamshchikov GV, Barnd DL, Eastham S, Galavotti H, Patterson JW, Deacon DH, Hibbitts S, Teates D, Neese PY, Grosh WW, Chianese-Bullock KA, Woodson EM, Wiernasz CJ, Merrill P, Gibson J, Ross M, Engelhard VH. Clinical and immunologic results of a randomized phase II trial of vaccination using four melanoma peptides either administered in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in adjuvant or pulsed on dendritic cells. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4016–4026. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kyte JA, Trachsel S, Risberg B, Thor Straten P, Lislerud K, Gaudernack G. Unconventional cytokine profiles and development of T cell memory in long-term survivors after cancer vaccination. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:1609–1626. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0670-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagorsen D, Thiel E. Clinical and immunologic responses to active specific cancer vaccines in human colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3064–3069. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eggermont AM. Therapeutic vaccines in solid tumours: can they be harmful? Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:2087–2090. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernhardt SL, Gjertsen MK, Trachsel S, Moller M, Eriksen JA, Meo M, Buanes T, Gaudernack G. Telomerase peptide vaccination of patients with non-resectable pancreatic cancer: a dose escalating phase I/II study. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1474–1482. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brunsvig PF, Aamdal S, Gjertsen MK, Kvalheim G, Markowski-Grimsrud CJ, Sve I, Dyrhaug M, Trachsel S, Moller M, Eriksen JA, Gaudernack G. Telomerase peptide vaccination: a phase I/II study in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:1553–1564. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0145-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Domchek SM, Recio A, Mick R, Clark CE, Carpenter EL, Fox KR, DeMichele A, Schuchter LM, Leibowitz MS, Wexler MH, Vance BA, Beatty GL, Veloso E, Feldman MD, Vonderheide RH. Telomerase-specific T-cell immunity in breast cancer: effect of vaccination on tumor immunosurveillance. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10546–10555. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greten TF, Forner A, Korangy F, N’Kontchou G, Barget N, Ayuso C, Ormandy LA, Manns MP, Beaugrand M, Bruix J. A phase II open label trial evaluating safety and efficacy of a telomerase peptide vaccination in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:209. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grabbe S, Beissert S, Schwarz T, Granstein RD. Dendritic cells as initiators of tumor immune responses: a possible strategy for tumor immunotherapy? Immunol Today. 1995;16:117–121. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vonderheide RH, Hahn WC, Schultze JL, Nadler LM. The telomerase catalytic subunit is a widely expressed tumor-associated antigen recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Immunity. 1999;10:673–679. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gjertsen MK, Saeterdal I, Saeboe-Larssen S, Gaudernack G. HLA-A3 restricted mutant ras specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes induced by vaccination with T-helper epitopes. J Mol Med. 2003;81:43–50. doi: 10.1007/s00109-002-0390-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ayello J, van de Ven C, Cairo E, Hochberg J, Baxi L, Satwani P, Cairo MS. Characterization of natural killer and natural killer-like T cells derived from ex vivo expanded and activated cord blood mononuclear cells: implications for adoptive cellular immunotherapy. Exp Hematol. 2009;37:1216–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brunsvig PF, Aamdal S, Gjertsen MK, Kvalheim G, Markowski-Grimsrud CJ, Sve I, Dyrhaug M, Trachsel S, Moller M, Eriksen JA, Gaudernack G. Telomerase peptide vaccination: a phase I/II study in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:1553–1564. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0145-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Speiser DE, Baumgaertner P, Barbey C, Rubio-Godoy V, Moulin A, Corthesy P, Devevre E, Dietrich PY, Rimoldi D, Lienard D, Cerottini JC, Romero P, Rufer N. A novel approach to characterize clonality and differentiation of human melanoma-specific T cell responses: spontaneous priming and efficient boosting by vaccination. J Immunol. 2006;177:1338–1348. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Speiser DE, Kyburz D, Stubi U, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Discrepancy between in vitro measurable and in vivo virus neutralizing cytotoxic T cell reactivities. Low T cell receptor specificity and avidity sufficient for in vitro proliferation or cytotoxicity to peptide-coated target cells but not for in vivo protection. J Immunol. 1992;149:972–980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmid DA, Irving MB, Posevitz V, Hebeisen M, Posevitz-Fejfar A, Sarria JC, Gomez-Eerland R, Thome M, Schumacher TN, Romero P, Speiser DE, Zoete V, Michielin O, Rufer N. Evidence for a TCR affinity threshold delimiting maximal CD8 T cell function. J Immunol. 2010;184:4936–4946. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Britten CM, Meyer RG, Frankenberg N, Huber C, Wolfel T. The use of clonal mRNA as an antigenic format for the detection of antigen-specific T lymphocytes in IFN-gamma ELISPOT assays. J Immunol Method. 2004;287:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herr W, Schneider J, Lohse AW, Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH, Wolfel T. Detection and quantification of blood-derived CD8+ T lymphocytes secreting tumor necrosis factor alpha in response to HLA-A2.1-binding melanoma and viral peptide antigens. J Immunol Method. 1996;191:131–142. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez M, Aguilera R, Perez C, Mendoza-Naranjo A, Pereda C, Ramirez M, Ferrada C, Aguillon JC, Salazar-Onfray F. The role of regulatory T lymphocytes in the induced immune response mediated by biological vaccines. Immunobiology. 2006;211:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markovic SN, Suman VJ, Ingle JN, Kaur JS, Pitot HC, Loprinzi CL, Rao RD, Creagan ET, Pittelkow MR, Allred JB, Nevala WK, Celis E. Peptide vaccination of patients with metastatic melanoma: improved clinical outcome in patients demonstrating effective immunization. Am J Clin Oncol. 2006;29:352–360. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000217877.78473.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quezada SA, Peggs KS, Curran MA, Allison JP. CTLA4 blockade and GM-CSF combination immunotherapy alters the intratumor balance of effector and regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1935–1945. doi: 10.1172/JCI27745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]